Kreuzzeitung on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' was a national daily newspaper published between 1848 and 1939 in the

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' was a national daily newspaper published between 1848 and 1939 in the

Monarchical-conservative circles sped up their push to found their own newspaper to represent the opposite side; this became the ''Kreuzzeitung''. Originally it was to be called (''The Iron Cross''), but some of the founders found the name too militaristic. They agreed on the more noncommittal with an image of the iron cross in the logo. The newspaper was nevertheless called the ''Kreuzzeitung'' by its authors, creators and readers from the first issue. The main founders, almost all of them belonging to the

Monarchical-conservative circles sped up their push to found their own newspaper to represent the opposite side; this became the ''Kreuzzeitung''. Originally it was to be called (''The Iron Cross''), but some of the founders found the name too militaristic. They agreed on the more noncommittal with an image of the iron cross in the logo. The newspaper was nevertheless called the ''Kreuzzeitung'' by its authors, creators and readers from the first issue. The main founders, almost all of them belonging to the

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' was controversial from the beginning, even among the various groups of conservatives. Particularly at the beginning of the post-1848 reactionary era, part of the upper nobility "categorically rejected such democratic means in the struggle to form opinions”. Very quickly, however, Wagener was able to win the trust of the founders. With the support of

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' was controversial from the beginning, even among the various groups of conservatives. Particularly at the beginning of the post-1848 reactionary era, part of the upper nobility "categorically rejected such democratic means in the struggle to form opinions”. Very quickly, however, Wagener was able to win the trust of the founders. With the support of  The ''Kreuzzeitung'' received most of its information from younger diplomats. The first foreign correspondents it was able to attract were George Hesekiel in Paris and, from 1851,

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' received most of its information from younger diplomats. The first foreign correspondents it was able to attract were George Hesekiel in Paris and, from 1851,

In the fall of 1872 Philipp von Nathusius-Ludom took over as editor-in-chief. He had no journalistic qualifications and strove passionately to make the paper populist - in today's parlance - and to stir up controversy. His efforts did not end well.

In June and July 1875 the journalist Franz Perrot, writing under a pseudonym, published a series of five articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' called "The Era of Bleichröder-Delbrück- Camphausen and the New German Economic Policy”. In them he indirectly attacked Bismarck in the person of his banker Gerson von Bleichröder. The articles, which were heavily edited by Nathusius-Ludom, described Bismarck's economic policy as the cause of the stock market crash of 1873, accused the bankers of self-serving speculation and alleged all but openly that Bismarck was involved in corruption.

The articles triggered a scandal. Perrot revealed that bankers, mediatized princes, and members of parliament were able to gain advantages on the stock exchange not just through the help of diplomatic channels. It came to light as well that a number of state officials participated in wild speculations and made use of their official or political influence by personally participating in and founding joint-stock companies. Bismarck had to respond to the accusations in court and before the Reichstag. For him the conflict with the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was "now out in the open, and the bridges are burnt". Bismarck called publicly for a boycott of the ''Kreuzzeitung''. The paper countered by publishing more than 100 names of declarants, nobles, members of parliament, and pastors who in letters to the newspaper expressed their approval of the publication of the research.

Nothing could be proven against the chancellor, but in fact he had hoped that his economic policy would lead to a split among the liberals. Moreover, his policies did indeed contribute to fluctuations in the stock market that had serious consequences. He bought up private railroads either himself or through intermediaries in order to establish a kind of state railroad system, thus putting considerable pressure on the railroad corporations and their steel suppliers. Perrot's accusations of corruption also later proved to be true. It emerged from documents that were uncovered that Bismarck had participated with his own funds in the founding of the Boden-Credit-Bank and had personally signed its foundation charter and articles of association, thus giving it a privileged position among German mortgage banks. The Iron Chancellor never forgave the ''Kreuzzeitung'' for the Era articles. Even in his late work (''Thoughts and Reminiscences''), he spoke of "poison-mixing" and the "vulgar ''Kreuzzeitung''".

It was never possible to find out who Perrot's source was. There was speculation as to whether

In the fall of 1872 Philipp von Nathusius-Ludom took over as editor-in-chief. He had no journalistic qualifications and strove passionately to make the paper populist - in today's parlance - and to stir up controversy. His efforts did not end well.

In June and July 1875 the journalist Franz Perrot, writing under a pseudonym, published a series of five articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' called "The Era of Bleichröder-Delbrück- Camphausen and the New German Economic Policy”. In them he indirectly attacked Bismarck in the person of his banker Gerson von Bleichröder. The articles, which were heavily edited by Nathusius-Ludom, described Bismarck's economic policy as the cause of the stock market crash of 1873, accused the bankers of self-serving speculation and alleged all but openly that Bismarck was involved in corruption.

The articles triggered a scandal. Perrot revealed that bankers, mediatized princes, and members of parliament were able to gain advantages on the stock exchange not just through the help of diplomatic channels. It came to light as well that a number of state officials participated in wild speculations and made use of their official or political influence by personally participating in and founding joint-stock companies. Bismarck had to respond to the accusations in court and before the Reichstag. For him the conflict with the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was "now out in the open, and the bridges are burnt". Bismarck called publicly for a boycott of the ''Kreuzzeitung''. The paper countered by publishing more than 100 names of declarants, nobles, members of parliament, and pastors who in letters to the newspaper expressed their approval of the publication of the research.

Nothing could be proven against the chancellor, but in fact he had hoped that his economic policy would lead to a split among the liberals. Moreover, his policies did indeed contribute to fluctuations in the stock market that had serious consequences. He bought up private railroads either himself or through intermediaries in order to establish a kind of state railroad system, thus putting considerable pressure on the railroad corporations and their steel suppliers. Perrot's accusations of corruption also later proved to be true. It emerged from documents that were uncovered that Bismarck had participated with his own funds in the founding of the Boden-Credit-Bank and had personally signed its foundation charter and articles of association, thus giving it a privileged position among German mortgage banks. The Iron Chancellor never forgave the ''Kreuzzeitung'' for the Era articles. Even in his late work (''Thoughts and Reminiscences''), he spoke of "poison-mixing" and the "vulgar ''Kreuzzeitung''".

It was never possible to find out who Perrot's source was. There was speculation as to whether

Jews were in fact an integral part of the German Empire. The ''Kreuzzeitung'' had had Jewish writers working for it since its founding. By 1880 it employed 46 permanent correspondents who were Jewish and had several Jewish freelancers. Jewish deputies with large Jewish constituencies were represented in the conservative parties. The warning from the emperor had its effect. In 1890 the ''Kreuzzeitung'' did not take part in the media controversy over the Vering-Salomon duel, in which the Jewish Salomon was killed by his fellow student Vering from the Albert Ludwig University, but treated the ensuing disputes objectively. The paper pursued an internally developed "taming concept", which it outlined in the summer of 1892 with the words, "The ''Kreuzzeitung'' is here to keep anti-Semitism within limits”.

The greatest damage to the respectability and credibility of the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was done by its editor-in-chief Hammerstein. He liked to portray himself as a "clean man" and always loudly promoted law and order but had relationships with women outside his marriage and lived in a grand style. On 4 July 1895 he was dismissed for dishonesty by the ''Kreuzzeitung'' committee. In his capacity as editor-in-chief he had approached a paper supplier named Flinsch and proposed a deal, asking for 200,000 marks (equivalent to about 1.3 million euros today) and in return committing himself to buy all the paper for the ''Kreuzzeitung'' from Flinsch for the next ten years. The deal went through. Hammerstein greatly inflated the invoices issued and pocketed the difference. In order to do this, he forged the signatures of the corporate board members Georg Graf von Kanitz and Hans Graf Finck von Finckenstein, as well as the seal and signature of a police superintendent. The affair was discovered. When it came to light that Hammerstein had exhausted a pension fund set up by the ''Kreuzzeitung'', he resigned his seats in the national and state parliaments in the summer of 1895 and fled with the 200,000 marks to Greece via Tyrol and Naples.

The scandal created enormous waves and was debated repeatedly in the Reichstag. The ''Kreuzzeitung's'' competition – and it was considerable – ran the story on the front pages and reported almost daily on the state of the investigation. In the search for the criminal editor-in-chief, the Reich office of justice finally sent a detective inspector named Wolff to southern Europe. He scoured several countries and found Baron von Hammerstein, alias "Dr. Heckert," in Athens on 27 December 1895. Wolff arranged for his deportation through the German embassy and had him arrested upon his arrival in Brindisi, Italy. In April 1896 Hammerstein was sentenced to three years imprisonment.

In the wake of these events, the lost about 2,000 readers. Circulation fell steadily. Even Wilhelm II, who did not want to abandon the paper, could do nothing, although he had it publicly announced that "The Emperor reads the ''Kreuzzeitung'' now as before; it is in fact the only political newspaper he reads".

Jews were in fact an integral part of the German Empire. The ''Kreuzzeitung'' had had Jewish writers working for it since its founding. By 1880 it employed 46 permanent correspondents who were Jewish and had several Jewish freelancers. Jewish deputies with large Jewish constituencies were represented in the conservative parties. The warning from the emperor had its effect. In 1890 the ''Kreuzzeitung'' did not take part in the media controversy over the Vering-Salomon duel, in which the Jewish Salomon was killed by his fellow student Vering from the Albert Ludwig University, but treated the ensuing disputes objectively. The paper pursued an internally developed "taming concept", which it outlined in the summer of 1892 with the words, "The ''Kreuzzeitung'' is here to keep anti-Semitism within limits”.

The greatest damage to the respectability and credibility of the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was done by its editor-in-chief Hammerstein. He liked to portray himself as a "clean man" and always loudly promoted law and order but had relationships with women outside his marriage and lived in a grand style. On 4 July 1895 he was dismissed for dishonesty by the ''Kreuzzeitung'' committee. In his capacity as editor-in-chief he had approached a paper supplier named Flinsch and proposed a deal, asking for 200,000 marks (equivalent to about 1.3 million euros today) and in return committing himself to buy all the paper for the ''Kreuzzeitung'' from Flinsch for the next ten years. The deal went through. Hammerstein greatly inflated the invoices issued and pocketed the difference. In order to do this, he forged the signatures of the corporate board members Georg Graf von Kanitz and Hans Graf Finck von Finckenstein, as well as the seal and signature of a police superintendent. The affair was discovered. When it came to light that Hammerstein had exhausted a pension fund set up by the ''Kreuzzeitung'', he resigned his seats in the national and state parliaments in the summer of 1895 and fled with the 200,000 marks to Greece via Tyrol and Naples.

The scandal created enormous waves and was debated repeatedly in the Reichstag. The ''Kreuzzeitung's'' competition – and it was considerable – ran the story on the front pages and reported almost daily on the state of the investigation. In the search for the criminal editor-in-chief, the Reich office of justice finally sent a detective inspector named Wolff to southern Europe. He scoured several countries and found Baron von Hammerstein, alias "Dr. Heckert," in Athens on 27 December 1895. Wolff arranged for his deportation through the German embassy and had him arrested upon his arrival in Brindisi, Italy. In April 1896 Hammerstein was sentenced to three years imprisonment.

In the wake of these events, the lost about 2,000 readers. Circulation fell steadily. Even Wilhelm II, who did not want to abandon the paper, could do nothing, although he had it publicly announced that "The Emperor reads the ''Kreuzzeitung'' now as before; it is in fact the only political newspaper he reads".

One of Foertsch's best foreign experts was Theodor Schiemann. Through his books and political articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' he attracted the attention of Wilhelm II. This developed into a friendly relationship through which Schiemann was able to exert political influence as an advisor, especially on eastern European issues. On the eve of World War I, Schiemann foresaw a two-front war and wrote in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' on 27 May 1914: "The German Empire must consider the fact that it will find England on the side of its future adversaries, and should not carelessly bring about such a conflict." The article had no effect: on 7 August 1914, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' published Kaiser Wilhelm's famous speech "To the German People!" in which he said that "now the sword must decide".

During the First World War not only did all political parties enter into the so-called

One of Foertsch's best foreign experts was Theodor Schiemann. Through his books and political articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' he attracted the attention of Wilhelm II. This developed into a friendly relationship through which Schiemann was able to exert political influence as an advisor, especially on eastern European issues. On the eve of World War I, Schiemann foresaw a two-front war and wrote in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' on 27 May 1914: "The German Empire must consider the fact that it will find England on the side of its future adversaries, and should not carelessly bring about such a conflict." The article had no effect: on 7 August 1914, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' published Kaiser Wilhelm's famous speech "To the German People!" in which he said that "now the sword must decide".

During the First World War not only did all political parties enter into the so-called

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' also supported the paramilitary

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' also supported the paramilitary

Front page from July 24, 1914, about the Austro-Hungarian ultimatum to Serbia

* ttps://zefys.staatsbibliothek-berlin.de/list/title/zdb/24350382/ Digitization of volumes 1857, 1858, 1859, 1867 and 1868. Staatsbibliothek zu Berlin; Die digitale Bibliothek {{italic title 1848 establishments in Germany 1939 disestablishments in Germany Defunct newspapers published in Germany German-language newspapers History of Prussia Newspapers published in Berlin Publications established in 1848 Publications disestablished in 1939

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' was a national daily newspaper published between 1848 and 1939 in the

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' was a national daily newspaper published between 1848 and 1939 in the Kingdom of Prussia

The Kingdom of Prussia (german: Königreich Preußen, ) was a German kingdom that constituted the state of Prussia between 1701 and 1918.Marriott, J. A. R., and Charles Grant Robertson. ''The Evolution of Prussia, the Making of an Empire''. Re ...

and then during the German Empire

The German Empire (),Herbert Tuttle wrote in September 1881 that the term "Reich" does not literally connote an empire as has been commonly assumed by English-speaking people. The term literally denotes an empire – particularly a hereditary ...

, the Weimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

and into the first part of the Third Reich

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

. The paper was a voice of the conservative upper class, although it was never associated with any political party and never had more than 10,000 subscribers. Its target readership was the nobility, military officers, high-ranking officials, industrialists and diplomats. Because its readers were among the elite, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was often quoted and at times very influential. It had connections to officials in the highest levels of government and business and was especially known for its foreign reporting. Most of its content consisted of carefully researched foreign and domestic news reported without commentary.

Its original name was officially the (''New Prussian Newspaper''), although because of the Iron Cross

The Iron Cross (german: link=no, Eisernes Kreuz, , abbreviated EK) was a military decoration in the Kingdom of Prussia, and later in the German Empire (1871–1918) and Nazi Germany (1933–1945). King Frederick William III of Prussia est ...

as its emblem in the title, it was simply called the ‘''Kreuzzeitung''’ (''Cross Newspaper'') in both general and official usage. In 1911 it was renamed the and then after 1929 the . Between 1932 and 1939 the official title was simply the ''Kreuzzeitung''. From its first issue to its last, the newspaper used the German motto from the Wars of Liberation "Forward with God for King and Fatherland" as its subtitle.Dagmar Bussiek: ''Mit Gott für König und Vaterland! Die Neue Preußische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892''. ith God for King and Fatherland! The New Prussian Newspaper (Cross Newspaper) 1848-1892 LIT Verlag, Münster 2002, p. 7 ff. It had editorial offices in various cities in Germany and abroad. Its headquarters was in Berlin.

The National Socialists

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in Na ...

took over the ''Kreuzzeitung'' on 29 August 1937, and the last issue was printed on on 31 January 1939.

Origin

In the Kingdom of Prussia, the (''General Prussian State Newspaper'') was published from 1819 as a newspaper for official announcements. It later developed into the (''German Imperial Gazette'') and today's (''Federal Gazette''). There was no other newspaper that represented the particular interests of the Prussian upper class. As a reaction to the March Revolution of 1848, theBundestag

The Bundestag (, "Federal Diet") is the German federal parliament. It is the only federal representative body that is directly elected by the German people. It is comparable to the United States House of Representatives or the House of Commons ...

repealed the Carlsbad Decrees

The Carlsbad Decrees (german: Karlsbader Beschlüsse) were a set of reactionary restrictions introduced in the states of the German Confederation by resolution of the Bundesversammlung on 20 September 1819 after a conference held in the spa town ...

on 2 April 1848. The middle class in particular, but also radical left-wing forces, took advantage of the newly won freedom of the press and founded numerous newspapers, among them the bourgeois-liberal and the ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung

The ''Neue Rheinische Zeitung: Organ der Demokratie'' ("New Rhenish Newspaper: Organ of Democracy") was a German daily newspaper, published by Karl Marx in Cologne between 1 June 1848 and 19 May 1849. It is recognised by historians as one of the ...

'' (''New Rhenish Newspaper'') with radical-communist content.

Monarchical-conservative circles sped up their push to found their own newspaper to represent the opposite side; this became the ''Kreuzzeitung''. Originally it was to be called (''The Iron Cross''), but some of the founders found the name too militaristic. They agreed on the more noncommittal with an image of the iron cross in the logo. The newspaper was nevertheless called the ''Kreuzzeitung'' by its authors, creators and readers from the first issue. The main founders, almost all of them belonging to the

Monarchical-conservative circles sped up their push to found their own newspaper to represent the opposite side; this became the ''Kreuzzeitung''. Originally it was to be called (''The Iron Cross''), but some of the founders found the name too militaristic. They agreed on the more noncommittal with an image of the iron cross in the logo. The newspaper was nevertheless called the ''Kreuzzeitung'' by its authors, creators and readers from the first issue. The main founders, almost all of them belonging to the camarilla

A camarilla is a group of courtiers or favourites who surround a king or ruler. Usually, they do not hold any office or have any official authority at the royal court but influence their ruler behind the scenes. Consequently, they also escape havi ...

around the Prussian king Frederick William IV

Frederick William IV (german: Friedrich Wilhelm IV.; 15 October 17952 January 1861), the eldest son and successor of Frederick William III of Prussia, reigned as King of Prussia from 7 June 1840 to his death on 2 January 1861. Also referred to ...

were:

* Ernst Ludwig von Gerlach

Ernst Ludwig von Gerlach (7 March 1795 – 18 February 1877) was a Prussian politician, editor and judge. He is considered one of the main founders and leading thinkers of the Conservative Party in Prussia and was for many years its leader in the P ...

* Leopold von Gerlach

* Hans Hugo von Kleist-Retzow

* Ernst Karl Wilhelm Adolf Freiherr Senfft von Pilsach

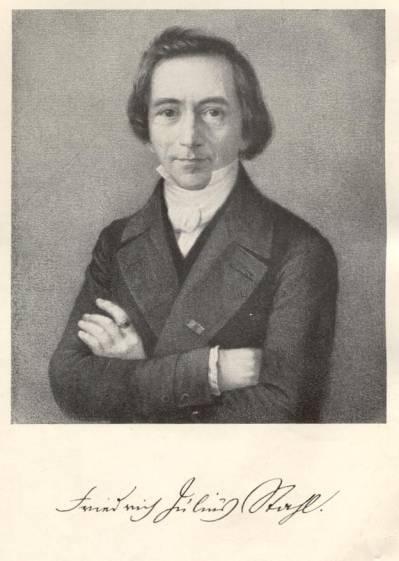

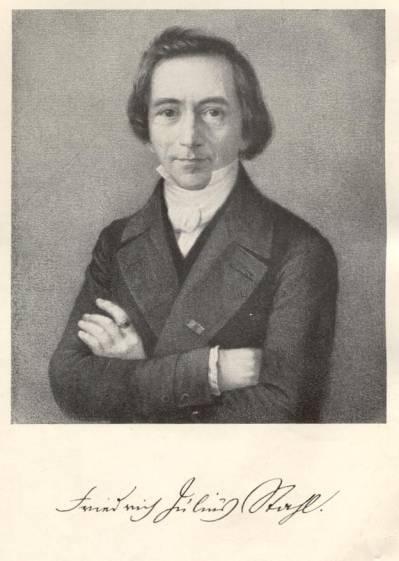

* Friedrich Julius Stahl

Friedrich Julius Stahl (16 January 1802 – 10 August 1861), German constitutional lawyer, political philosopher and politician.

Biography

Born at Würzburg, of Jewish parentage, as Julius Jolson, he was brought up strictly in the Jewish religio ...

* Hermann Wagener Friedrich Wilhelm Hermann Wagener (March 8, 1815 in Segeletz (now Wusterhausen) – April 22, 1889 in Friedenau (now part of Berlin)) was a Prussian jurist, chief editor of the Kreuzzeitung (The "New Prussian Newspaper") and was a politician and mi ...

* Moritz August von Bethmann-Hollweg

Moritz August von Bethmann-Hollweg (born 8 April 1795 in Frankfurt am Main, died 14 July 1877 on Rheineck castle near Niederbreisig on the Rhine) was a German jurist and Prussian politician.

Life

Bethmann-Hollweg was born in Frankfurt am Mai ...

* Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

* Carl von Voß-Buch

The launch of the newspaper and the founding of the publishing house were carried out with military precision. The intent was for the paper to be characterized by good networking with the highest state institutions. Berlin was chosen both for the headquarters of the New Prussian Newspaper, Inc. and as the location for its printing. The calculated starting capital of 20,000 thaler

A thaler (; also taler, from german: Taler) is one of the large silver coins minted in the states and territories of the Holy Roman Empire and the Habsburg monarchy during the Early Modern period. A ''thaler'' size silver coin has a diameter of ...

s was raised by selling shares of 100 thalers each. A total of 80 people subscribed, including Otto von Bismarck

Otto, Prince of Bismarck, Count of Bismarck-Schönhausen, Duke of Lauenburg (, ; 1 April 1815 – 30 July 1898), born Otto Eduard Leopold von Bismarck, was a conservative German statesman and diplomat. From his origins in the upper class of J ...

, who for many years personally wrote articles for the ''Kreuzzeitung''. The largest shareholder, with shares worth 2,000 thalers, was Carl von Voß-Buch, a lawyer and civil adjutant to William IV. The subscription price was set at 1.5 thalers per quarter; outside Berlin, subscriptions cost 2 thalers due to the postal surcharge. The paper was printed initially by the Brandis Company in Berlin, and three sample issues were sent out in mid-June 1848. Following this, a large number of subscriptions was immediately able to be sold to aristocrats, district councils and senior civil servants. Hermann Wagener Friedrich Wilhelm Hermann Wagener (March 8, 1815 in Segeletz (now Wusterhausen) – April 22, 1889 in Friedenau (now part of Berlin)) was a Prussian jurist, chief editor of the Kreuzzeitung (The "New Prussian Newspaper") and was a politician and mi ...

became editor-in-chief, and issue Number 1 of the appeared on 30 June 1848.

In connection to the new paper, the Prussian Conservative Party was called the “''Kreuzzeitung'' Party” or simply the "Cross Party”. In the same way, the use of the colloquial terms "black" or having "black views" to refer to members and voters of Christian conservative parties can be traced to the ''Kreuzzeitung'', because the paper was printed in jet black until its end.

Development to the founding of the German Empire

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' was controversial from the beginning, even among the various groups of conservatives. Particularly at the beginning of the post-1848 reactionary era, part of the upper nobility "categorically rejected such democratic means in the struggle to form opinions”. Very quickly, however, Wagener was able to win the trust of the founders. With the support of

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' was controversial from the beginning, even among the various groups of conservatives. Particularly at the beginning of the post-1848 reactionary era, part of the upper nobility "categorically rejected such democratic means in the struggle to form opinions”. Very quickly, however, Wagener was able to win the trust of the founders. With the support of Friedrich Julius Stahl

Friedrich Julius Stahl (16 January 1802 – 10 August 1861), German constitutional lawyer, political philosopher and politician.

Biography

Born at Würzburg, of Jewish parentage, as Julius Jolson, he was brought up strictly in the Jewish religio ...

, he quickly built up a dense network of authors and informants. The majority wrote their articles under a pseudonym as independent contributors. Only in Vienna, Dresden, Munich and other capitals of the individual German states were correspondents permanently employed. For many years Bismarck himself supplied reports from Paris. Reporters obtained news from all other countries through diplomats in Berlin.Bernhard Studt: ''Bismarck als Mitarbeiter der „Kreuzzeitung“ in den Jahren 1848 und 1849'' ismarck as Contributor to the Kreuzzeitung in the Years 1848 and 1849'.'' Dissertation. Kröger Druckerei, Blankenese 1903, p. 6.

The editorial staff enjoyed a relatively high degree of independence, although the paper's loyalty to the monarchy was never questioned. Until the end of 1849 the paper was not self-supporting. Frederick William IV is said to have personally supported the ''Kreuzzeitung'' financially at this time.Dagmar Bussiek: ''Mit Gott für König und Vaterland! Die Neue Preußische Zeitung (Kreuzzeitung) 1848–1892'' ith God for King and Fatherland! The New Prussian Newspaper (Cross Newspaper) 1848-1892 LIT Verlag, Münster 2002, p. 37. Nevertheless, the editors were soon in a position to buy back most of the shares from the paper's backers. The chairmanship of the joint stock company was henceforth assumed by the current editor-in-chief. The shareholders were represented only on a five-member committee which had the right to audit the accounts but could not influence the newspaper's content or personnel.

That this independence had distinct limits was clearly felt by the first editor-in-chief. After the newspaper continuously and openly criticized both the dictatorship of Napoleon III

Napoleon III (Charles Louis Napoléon Bonaparte; 20 April 18089 January 1873) was the first President of France (as Louis-Napoléon Bonaparte) from 1848 to 1852 and the last monarch of France as Emperor of the French from 1852 to 1870. A nephew ...

and him as a person, Bismarck called on the paper to exercise restraint. The editors ignored the advice. As a consequence, in April 1852 the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was banned in France, and several editions were confiscated in Berlin. The next strains followed when the editorial board openly spoke out against the repeal of the Basic Rights of the German People as drafted by the Frankfurt Parliament

The Frankfurt Parliament (german: Frankfurter Nationalversammlung, literally ''Frankfurt National Assembly'') was the first freely elected parliament for all German states, including the German-populated areas of Austria-Hungary, elected on 1 Ma ...

and thus against the Lesser Germany

{{more citations needed, date=April 2017

The term Lesser Germany (German: ''Kleindeutschland'') or Lesser German solution (German: Kleindeutsche Lösung) denoted essentially exclusion of Austria of the Habsburgs from the planned German unification ...

solution. A wide variety of power interests and spheres of influence clashed here.

The paper's position repeatedly met with opposition from Otto Theodor von Manteuffel

Otto Theodor von Manteuffel (3 February 1805 – 26 November 1882) was a conservative Prussian statesman, serving nearly a decade as prime minister.

Biography

Born into an aristocratic family in Lübben (Spreewald), Manteuffel attended the Lande ...

, then the minister president of Prussia

The office of Minister-President (german: Ministerpräsident), or Prime Minister, of Prussia existed from 1848, when it was formed by King Frederick William IV during the 1848–49 Revolution, until the abolition of Prussia in 1947 by the Allie ...

. Another bitter rival of the paper was the head of the Police Department in the Ministry of the Interior, Karl Ludwig Friedrich von Hinckeldey. Hinckeldey did not hesitate to take the editor-in-chief of the into custody for several days when he refused to give the names of all writers, including anonymous authors, to police authorities. Hinckeldey received a personal reprimand from the king for his high-handed action. Although Wagener had received royal backing, he was unnerved and resigned from his position at the ''Kreuzzeitung''. Tuiscon Beutner became the new editor-in-chief in 1854. Frederick William IV advised him "that the newspaper should continue to appear undeterred and should not change anything in its policy, only that it should be cautious toward France”.

Under Beutner's leadership too the paper was not immune to impoundments. Entire editions that had already been printed were repeatedly confiscated. The reason for this was the differing views within the Conservative Party, which ultimately led to several splits from 1857 onward. In addition, the relationship between the ''Kreuzzeitung'' and Bismarck worsened. Even though he regularly had articles written for the ''Kreuzzeitung'' through his press assistant Moritz Busch

Julius Hermann Moritz Busch (13 February 1821 – 16 November 1899) was a German publicist. He has been characterized as “ Bismarck's Boswell.”

Biography

Busch was born at Dresden. He entered the University of Leipzig in 1841 as a student of ...

until 1871, the '' Norddeutsche Allgemeine Zeitung'' was steadily evolving into "Bismarck's house postil

A postil or postill ( la, postilla; german: Postille) was originally a term for Bible commentaries. It is derived from the Latin ''post illa verba textus'' ("after these words from Scripture"), referring to biblical readings. The word first occurs ...

".

Although the ''Kreuzzeitung'' predominantly represented the views of the arch-conservatives, i.e. the representatives of the king and later the emperor, it also always covered the interests of the liberal-conservative, Christian-conservative and social-conservative forces. In doing so, the paper presented facts or actions primarily as reports or news items, that is, without an assessment by the author. But the very fact that it published different positions without commenting on them brought it regularly under criticism. The German Question

The "German question" was a debate in the 19th century, especially during the Revolutions of 1848, over the best way to achieve a unification of Germany, unification of all or most lands inhabited by Germans. From 1815 to 1866, about 37 independ ...

and the relations of the German states with the major European powers developed into perennial topics of dispute.

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' received most of its information from younger diplomats. The first foreign correspondents it was able to attract were George Hesekiel in Paris and, from 1851,

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' received most of its information from younger diplomats. The first foreign correspondents it was able to attract were George Hesekiel in Paris and, from 1851, Theodor Fontane

Theodor Fontane (; 30 December 1819 – 20 September 1898) was a German novelist and poet, regarded by many as the most important 19th-century German-language realist author. He published the first of his novels, for which he is best known toda ...

in London. Later the ''Kreuzzeitung'' had permanent staff in all European capitals. Until then, reports from foreign newspapers were sometimes passed off as the paper's own work. What today violates copyright law was a widespread practice at the time, and not only among German newspaper writers. Even the Times of London

''The Times'' is a British daily national newspaper based in London. It began in 1785 under the title ''The Daily Universal Register'', adopting its current name on 1 January 1788. ''The Times'' and its sister paper ''The Sunday Times'' (fou ...

translated complete articles from the ''Kreuzzeitung'', unhesitatingly citing their "own Berlin correspondent" as the source.

Fontane worked in London not just for the . He sometimes reported directly to the German ambassador Albrecht von Bernstorff

Albrecht Graf von Bernstorff (22 March 1809 – 26 March 1873) was a Prussian statesman.

Early life

Bernstorff was born at the estate Dreilützow (now in the municipality of Wittendörp), in the Duchy of Mecklenburg-Schwerin. He was a s ...

and released press reports in support of Prussian foreign policy to English and German newspapers. At the same time he traveled to Copenhagen and wrote regular articles for the ''Kreuzzeitung'' about the German-Danish War

The Second Schleswig War ( da, Krigen i 1864; german: Deutsch-Dänischer Krieg) also sometimes known as the Dano-Prussian War or Prusso-Danish War was the second military conflict over the Schleswig-Holstein Question of the nineteenth century. T ...

. In his biography Fontane maintained that he "found no Byzantinism

Byzantinism, or Byzantism, is the political system and culture of the Byzantine Empire, and its spiritual successors the Orthodox Christian Balkan countries of Greece and Bulgaria especially, and to a lesser extent Serbia and some other Orthodox ...

or cowardly hypocrisy whatsoever" at the ''Kreuzzeitung'' and that Friedrich Julius Stahl's motto applied in the editorial office: "Gentlemen, let us not forget that even the most conservative paper is still more paper than conservative." What was meant by this was that the presentation of various opinions, which should on principle be passed on without any judgment by the author, was part of a newspaper's sales success. In 1870 Fontane moved to the ''Vossische Zeitung

The (''Voss's Newspaper'') was a nationally-known Berlin newspaper that represented the interests of the liberal middle class. It was also generally regarded as Germany's national newspaper of record. In the Berlin press it held a special role d ...

'' as a theater critic.

The newspaper was printed by the Heinicke printing house in Berlin from 1852 to 1908. The publisher, Ferdinand Heinicke, also assumed responsibility for the content of the paper as the so-called ‘sitting editor’ who was the sole person liable in legal disputes and lawsuits. This protected the ''Kreuzzeitung's'' editors from such entanglements.Trends during the imperial period

In 1861 the circulation was 7,100 and increased to around 9,500 by 1874. Despite its relatively small circulation, it stood at the intersection of politics and journalism and was at the height of its power. Almost all newspapers in Germany and abroad regularly used introductory sentences such as "According to the ''Kreuzzeitung'' ...", "Well-informed ''Kreuzzeitung'' sources have learned ...", "As the ''Kreuzzeitung'' reports ...", etc. After 1868 Bismarck used the notorious Reptile Fund – money diverted for political purposes from elsewhere in the budget or to pay bribes – in order to influence the press and implement his policies. Evidence shows that the did not receive any funds from these "black coffers". The editors even dared to question such propaganda methods in two articles. As an economically self-supporting joint-stock company, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was in principle independent of the crown and the government. Likewise, it was never a party newspaper or the mouthpiece of a particular party. Until its last issue in 1939, the paper had no party affiliation. Rather, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' represented the link between all conservative forces. After the foundation of the German Empire in 1871, the reputation of the newspaper changed permanently. The reasons for this were the so-called "Era articles”, the "Hammerstein affair”, and above all the dissolution of the Prussian Conservative Party. This split into, among others, theFree Conservative Party

The Free Conservative Party (german: Freikonservative Partei, FKP) was a liberal-conservative political party in Prussia and the German Empire which emerged from the Prussian Conservative Party in the Prussian Landtag in 1866. In the federal ele ...

, German Progress Party

The German Progress Party (german: Deutsche Fortschrittspartei, DFP) was the first modern political party in Germany, founded by liberal members of the Prussian House of Representatives () in 1861 in opposition to Minister President Otto von Bism ...

, National Liberal Party, German Center Party

The Centre Party (german: Zentrum), officially the German Centre Party (german: link=no, Deutsche Zentrumspartei) and also known in English as the Catholic Centre Party, is a Catholic political party in Germany, influential in the German Empire ...

, Christian Social Party and German Conservative Party

The German Conservative Party (german: Deutschkonservative Partei, DkP) was a right-wing political party of the German Empire founded in 1876. It largely represented the wealthy landowning elite Prussian Junkers.

The party was a response to Ge ...

.

The Era articles

In the fall of 1872 Philipp von Nathusius-Ludom took over as editor-in-chief. He had no journalistic qualifications and strove passionately to make the paper populist - in today's parlance - and to stir up controversy. His efforts did not end well.

In June and July 1875 the journalist Franz Perrot, writing under a pseudonym, published a series of five articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' called "The Era of Bleichröder-Delbrück- Camphausen and the New German Economic Policy”. In them he indirectly attacked Bismarck in the person of his banker Gerson von Bleichröder. The articles, which were heavily edited by Nathusius-Ludom, described Bismarck's economic policy as the cause of the stock market crash of 1873, accused the bankers of self-serving speculation and alleged all but openly that Bismarck was involved in corruption.

The articles triggered a scandal. Perrot revealed that bankers, mediatized princes, and members of parliament were able to gain advantages on the stock exchange not just through the help of diplomatic channels. It came to light as well that a number of state officials participated in wild speculations and made use of their official or political influence by personally participating in and founding joint-stock companies. Bismarck had to respond to the accusations in court and before the Reichstag. For him the conflict with the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was "now out in the open, and the bridges are burnt". Bismarck called publicly for a boycott of the ''Kreuzzeitung''. The paper countered by publishing more than 100 names of declarants, nobles, members of parliament, and pastors who in letters to the newspaper expressed their approval of the publication of the research.

Nothing could be proven against the chancellor, but in fact he had hoped that his economic policy would lead to a split among the liberals. Moreover, his policies did indeed contribute to fluctuations in the stock market that had serious consequences. He bought up private railroads either himself or through intermediaries in order to establish a kind of state railroad system, thus putting considerable pressure on the railroad corporations and their steel suppliers. Perrot's accusations of corruption also later proved to be true. It emerged from documents that were uncovered that Bismarck had participated with his own funds in the founding of the Boden-Credit-Bank and had personally signed its foundation charter and articles of association, thus giving it a privileged position among German mortgage banks. The Iron Chancellor never forgave the ''Kreuzzeitung'' for the Era articles. Even in his late work (''Thoughts and Reminiscences''), he spoke of "poison-mixing" and the "vulgar ''Kreuzzeitung''".

It was never possible to find out who Perrot's source was. There was speculation as to whether

In the fall of 1872 Philipp von Nathusius-Ludom took over as editor-in-chief. He had no journalistic qualifications and strove passionately to make the paper populist - in today's parlance - and to stir up controversy. His efforts did not end well.

In June and July 1875 the journalist Franz Perrot, writing under a pseudonym, published a series of five articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' called "The Era of Bleichröder-Delbrück- Camphausen and the New German Economic Policy”. In them he indirectly attacked Bismarck in the person of his banker Gerson von Bleichröder. The articles, which were heavily edited by Nathusius-Ludom, described Bismarck's economic policy as the cause of the stock market crash of 1873, accused the bankers of self-serving speculation and alleged all but openly that Bismarck was involved in corruption.

The articles triggered a scandal. Perrot revealed that bankers, mediatized princes, and members of parliament were able to gain advantages on the stock exchange not just through the help of diplomatic channels. It came to light as well that a number of state officials participated in wild speculations and made use of their official or political influence by personally participating in and founding joint-stock companies. Bismarck had to respond to the accusations in court and before the Reichstag. For him the conflict with the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was "now out in the open, and the bridges are burnt". Bismarck called publicly for a boycott of the ''Kreuzzeitung''. The paper countered by publishing more than 100 names of declarants, nobles, members of parliament, and pastors who in letters to the newspaper expressed their approval of the publication of the research.

Nothing could be proven against the chancellor, but in fact he had hoped that his economic policy would lead to a split among the liberals. Moreover, his policies did indeed contribute to fluctuations in the stock market that had serious consequences. He bought up private railroads either himself or through intermediaries in order to establish a kind of state railroad system, thus putting considerable pressure on the railroad corporations and their steel suppliers. Perrot's accusations of corruption also later proved to be true. It emerged from documents that were uncovered that Bismarck had participated with his own funds in the founding of the Boden-Credit-Bank and had personally signed its foundation charter and articles of association, thus giving it a privileged position among German mortgage banks. The Iron Chancellor never forgave the ''Kreuzzeitung'' for the Era articles. Even in his late work (''Thoughts and Reminiscences''), he spoke of "poison-mixing" and the "vulgar ''Kreuzzeitung''".

It was never possible to find out who Perrot's source was. There was speculation as to whether Wilhelm I

William I or Wilhelm I (german: Wilhelm Friedrich Ludwig; 22 March 1797 – 9 March 1888) was King of Prussia from 2 January 1861 and German Emperor from 18 January 1871 until his death in 1888. A member of the House of Hohenzollern, he was the f ...

had wanted to give his Reich chancellor a personal warning. The emperor did not comment openly on the accusations of corruption, but he disliked the anti-Jewish polemic that was present in the five articles. Their goal was not primarily to defame the Jews but explicitly to "exasperate Bismarck". The proxy attacks on the Jewish bankers, however, went too far for Wilhelm I, who favored integration of the Jews. He had signed a pan-German law in 1871 granting equal rights to the Jews, and in particular in 1872 had elevated Gerson Bleichröder to the hereditary nobility, the first Jew to be accorded the honor. The consequence was that Franz Perrot and Philipp von Nathusius-Ludom had to leave the ''Kreuzzeitung''.

The Hammerstein affair

Benno von Niebelschütz became the editor-in-chief in 1876. With him, according to the emperor, the newspaper "not only lost all journalistic bite, but in part even its readability". He was succeeded in 1884 by Wilhelm Joachim Baron von Hammerstein. Under his leadership, the paper treated the so-calledJewish question

The Jewish question, also referred to as the Jewish problem, was a wide-ranging debate in 19th- and 20th-century European society that pertained to the appropriate status and treatment of Jews. The debate, which was similar to other "national ...

as a standalone topic. From today's perspective the ''Kreuzzeitung'' at times came close to being anti-Semitic. The term ‘anti-Semitic’ did not exist in Germany before 1879, and the controversy was fueled by various supporters and opponents from every conceivable point of view. Even among Jewish associations, conflicting directions emerged, some advocating a turn towards modern society and strong assimilation, and others seeking to preserve the traditions of the faith. With Theodor Herzl

Theodor Herzl; hu, Herzl Tivadar; Hebrew name given at his brit milah: Binyamin Ze'ev (2 May 1860 – 3 July 1904) was an Austro-Hungarian Jewish lawyer, journalist, playwright, political activist, and writer who was the father of modern p ...

, who publicly and effectively sought the establishment of a Jewish state, the debate took on foreign policy dimensions. In the last two decades of the 19th century, the issue was so prominent that no newspaper could avoid it.

Hammerstein worked closely with the court chaplain Adolf Stoecker

Adolf Stoecker (December 11, 1835 – February 2, 1909) was a German court chaplain to Kaiser Wilhelm I, a politician, leading antisemite, and a Lutheran theologian who founded the Christian Social Party to lure members away from the S ...

, with whom he maintained a personal friendship. Stoecker demanded, including in articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'', an unconditional assimilation of the Jews through baptism and a limitation of the 1871 constitutional act giving them equal status. He also accused several individuals of abusing Jewish emancipation to secure positions of economic and political power. Hammerstein and Stoecker completely ignored the warnings of the crown prince, who a short time later became Emperor Frederick III. He repeatedly described hostility toward Jews as the "disgrace of the century". The imperial house was determined to put an end to Stoecker's activities. In the spring of 1889, the Crown Council officially informed him that he was to cease his agitations. Since Stoecker continued to make trouble, he was forced to resign a year later by Wilhelm II

Wilhelm II (Friedrich Wilhelm Viktor Albert; 27 January 18594 June 1941) was the last German Emperor (german: Kaiser) and King of Prussia, reigning from 15 June 1888 until his abdication on 9 November 1918. Despite strengthening the German Empir ...

, who became emperor after the death of his father.

Jews were in fact an integral part of the German Empire. The ''Kreuzzeitung'' had had Jewish writers working for it since its founding. By 1880 it employed 46 permanent correspondents who were Jewish and had several Jewish freelancers. Jewish deputies with large Jewish constituencies were represented in the conservative parties. The warning from the emperor had its effect. In 1890 the ''Kreuzzeitung'' did not take part in the media controversy over the Vering-Salomon duel, in which the Jewish Salomon was killed by his fellow student Vering from the Albert Ludwig University, but treated the ensuing disputes objectively. The paper pursued an internally developed "taming concept", which it outlined in the summer of 1892 with the words, "The ''Kreuzzeitung'' is here to keep anti-Semitism within limits”.

The greatest damage to the respectability and credibility of the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was done by its editor-in-chief Hammerstein. He liked to portray himself as a "clean man" and always loudly promoted law and order but had relationships with women outside his marriage and lived in a grand style. On 4 July 1895 he was dismissed for dishonesty by the ''Kreuzzeitung'' committee. In his capacity as editor-in-chief he had approached a paper supplier named Flinsch and proposed a deal, asking for 200,000 marks (equivalent to about 1.3 million euros today) and in return committing himself to buy all the paper for the ''Kreuzzeitung'' from Flinsch for the next ten years. The deal went through. Hammerstein greatly inflated the invoices issued and pocketed the difference. In order to do this, he forged the signatures of the corporate board members Georg Graf von Kanitz and Hans Graf Finck von Finckenstein, as well as the seal and signature of a police superintendent. The affair was discovered. When it came to light that Hammerstein had exhausted a pension fund set up by the ''Kreuzzeitung'', he resigned his seats in the national and state parliaments in the summer of 1895 and fled with the 200,000 marks to Greece via Tyrol and Naples.

The scandal created enormous waves and was debated repeatedly in the Reichstag. The ''Kreuzzeitung's'' competition – and it was considerable – ran the story on the front pages and reported almost daily on the state of the investigation. In the search for the criminal editor-in-chief, the Reich office of justice finally sent a detective inspector named Wolff to southern Europe. He scoured several countries and found Baron von Hammerstein, alias "Dr. Heckert," in Athens on 27 December 1895. Wolff arranged for his deportation through the German embassy and had him arrested upon his arrival in Brindisi, Italy. In April 1896 Hammerstein was sentenced to three years imprisonment.

In the wake of these events, the lost about 2,000 readers. Circulation fell steadily. Even Wilhelm II, who did not want to abandon the paper, could do nothing, although he had it publicly announced that "The Emperor reads the ''Kreuzzeitung'' now as before; it is in fact the only political newspaper he reads".

Jews were in fact an integral part of the German Empire. The ''Kreuzzeitung'' had had Jewish writers working for it since its founding. By 1880 it employed 46 permanent correspondents who were Jewish and had several Jewish freelancers. Jewish deputies with large Jewish constituencies were represented in the conservative parties. The warning from the emperor had its effect. In 1890 the ''Kreuzzeitung'' did not take part in the media controversy over the Vering-Salomon duel, in which the Jewish Salomon was killed by his fellow student Vering from the Albert Ludwig University, but treated the ensuing disputes objectively. The paper pursued an internally developed "taming concept", which it outlined in the summer of 1892 with the words, "The ''Kreuzzeitung'' is here to keep anti-Semitism within limits”.

The greatest damage to the respectability and credibility of the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was done by its editor-in-chief Hammerstein. He liked to portray himself as a "clean man" and always loudly promoted law and order but had relationships with women outside his marriage and lived in a grand style. On 4 July 1895 he was dismissed for dishonesty by the ''Kreuzzeitung'' committee. In his capacity as editor-in-chief he had approached a paper supplier named Flinsch and proposed a deal, asking for 200,000 marks (equivalent to about 1.3 million euros today) and in return committing himself to buy all the paper for the ''Kreuzzeitung'' from Flinsch for the next ten years. The deal went through. Hammerstein greatly inflated the invoices issued and pocketed the difference. In order to do this, he forged the signatures of the corporate board members Georg Graf von Kanitz and Hans Graf Finck von Finckenstein, as well as the seal and signature of a police superintendent. The affair was discovered. When it came to light that Hammerstein had exhausted a pension fund set up by the ''Kreuzzeitung'', he resigned his seats in the national and state parliaments in the summer of 1895 and fled with the 200,000 marks to Greece via Tyrol and Naples.

The scandal created enormous waves and was debated repeatedly in the Reichstag. The ''Kreuzzeitung's'' competition – and it was considerable – ran the story on the front pages and reported almost daily on the state of the investigation. In the search for the criminal editor-in-chief, the Reich office of justice finally sent a detective inspector named Wolff to southern Europe. He scoured several countries and found Baron von Hammerstein, alias "Dr. Heckert," in Athens on 27 December 1895. Wolff arranged for his deportation through the German embassy and had him arrested upon his arrival in Brindisi, Italy. In April 1896 Hammerstein was sentenced to three years imprisonment.

In the wake of these events, the lost about 2,000 readers. Circulation fell steadily. Even Wilhelm II, who did not want to abandon the paper, could do nothing, although he had it publicly announced that "The Emperor reads the ''Kreuzzeitung'' now as before; it is in fact the only political newspaper he reads".

Neutrality during World War I

The decline was not halted until Georg Foertsch took over as editor-in-chief in 1913. He kept the circulation constant at 7,200 copies until 1932.Kurt Koszyk, Karl Hugo Pruys: ''Wörterbuch zur Publizistik'' ictionary of Journalism'.'' Walter de Gruyter, 1970, p. 205. The retired major had previously worked as a press attaché to the imperial navy. He maintained neutrality and concentrated on the ''Kreuzzeitung's'' core competence, foreign reporting. Foertsch encouraged young journalists but hired only professionals. They had the best connections to diplomats, politicians and industrialists both at home and abroad, with the result that the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was able to publish numerous reports exclusively and/or be the first to cover them. In domestic politics, Foertsch maintained personal contacts with the imperial treasury, from which he regularly received comprehensive information about the current financial and economic state of affairs, as well as the plans of the German Reich. The new editor-in-chief reorganized finances and subsumed the buildings and editorial offices that the newspaper had acquired in recent decades in Germany and abroad under a wholly owned subsidiary, ''Kreuzzeitung'' Real Estate Inc. He also raised the subscriber price to 9 marks (today about 55 euros) per quarter. The readership apparently had no problem with this. Aristocratic landowners, politicians and high-ranking civil servants in particular subscribed to the paper for an additional 1.25 marks (today around 8 euros) per week, with twice-daily postal delivery. In the German protectorates as well as in Austria-Hungary and Luxembourg, the delivery charges by mail were also 1.25 marks per week. A single issue cost 10 pfennigs. One of Foertsch's best foreign experts was Theodor Schiemann. Through his books and political articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' he attracted the attention of Wilhelm II. This developed into a friendly relationship through which Schiemann was able to exert political influence as an advisor, especially on eastern European issues. On the eve of World War I, Schiemann foresaw a two-front war and wrote in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' on 27 May 1914: "The German Empire must consider the fact that it will find England on the side of its future adversaries, and should not carelessly bring about such a conflict." The article had no effect: on 7 August 1914, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' published Kaiser Wilhelm's famous speech "To the German People!" in which he said that "now the sword must decide".

During the First World War not only did all political parties enter into the so-called

One of Foertsch's best foreign experts was Theodor Schiemann. Through his books and political articles in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' he attracted the attention of Wilhelm II. This developed into a friendly relationship through which Schiemann was able to exert political influence as an advisor, especially on eastern European issues. On the eve of World War I, Schiemann foresaw a two-front war and wrote in the ''Kreuzzeitung'' on 27 May 1914: "The German Empire must consider the fact that it will find England on the side of its future adversaries, and should not carelessly bring about such a conflict." The article had no effect: on 7 August 1914, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' published Kaiser Wilhelm's famous speech "To the German People!" in which he said that "now the sword must decide".

During the First World War not only did all political parties enter into the so-called Burgfrieden

The or 'c.fBurgfriedeat Duden online. was a German medieval term that referred to imposition of a state of truce within the jurisdiction of a castle, and sometimes its estate, under which feuds, i.e. conflicts between private individuals, were ...

– the tabling of domestic political and economic disputes – but in principle all German newspapers did as well. This went so far that several conservative parties effectively ceased their activities. During this period the ''Kreuzzeitung'' provided very well-researched commentaries which are still one of the most important sources for historians on military as well as day-to-day political events of World War I.

On 9 November 1918, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' ran the headline "The Emperor Abdicates!":"We lack the words to express what moves us in this hour. Under the force of events, the thirty-year reign of our Emperor, who always wanted the best for his people, has come to an end. The heart of every monarchist is convulsed at this event."Deep grief, apathy, escapism and hopelessness, as well as fears of what was to come that reached the point of panic reactions, characterized the prevailing mood of the old elites after the collapse of the empire. For the monarchist ''Kreuzzeitung'', a world had irrevocably collapsed.

Situation in the Weimar Republic

Writers have interpreted the attitude of the editors and thus the basic political direction of the ''Kreuzzeitung'' differently, especially during theWeimar Republic

The Weimar Republic (german: link=no, Weimarer Republik ), officially named the German Reich, was the government of Germany from 1918 to 1933, during which it was a constitutional federal republic for the first time in history; hence it is al ...

. Depending on the author's ideological view, the spectrum ranges from "stock Protestant", "feudal", "German national", "ultraconservative", "agrarian", "East Elbia

East Elbia (german: Ostelbien) was an informal denotation for those parts of the German Reich until World War II that lay east of the river Elbe.

The region comprised the Prussian provinces of Brandenburg, the eastern parts of Saxony (Jerichower ...

n” and "Junker

Junker ( da, Junker, german: Junker, nl, Jonkheer, en, Yunker, no, Junker, sv, Junker ka, იუნკერი (Iunkeri)) is a noble honorific, derived from Middle High German ''Juncherre'', meaning "young nobleman"Duden; Meaning of Junke ...

conservative" to "anti-modern”. More recent research uses "monarchist-conservative" as the general term and regards other descriptions as one-sided at best and some of them even as false. On 12 November 1918, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' ran the headline: "Germany is facing an upheaval such as history has not yet seen" and, following Aristotle's constitutional theory, described democracy as a "degenerate" form of government, saying that "only a tyranny is worse". The goal of the paper remained the old one: defense of the monarchy. That meant that the ''Kreuzzeitung's'' stance was anti-Weimar Republic, but also anti-dictatorship.Wolfgang Benz, Michael Dreyer: ''Handbuch des Antisemitismus'' andbook of Antisemitism'.'' Walter de Gruyter, 2013, p. 419.

Politically, most of the ''Kreuzzeitung's'' staff did not feel at home anywhere after the November Revolution. Few of its editors turned their backs on the paper; almost all were monarchists. They received some of the highest wages in the industry, and above all they were paid on time. The ''Kreuzzeitung'' had no party affiliation, so correspondents had a relatively wide latitude. As before, most of the newspaper consisted of scrupulously researched foreign news reported without commentary. Travel expenses were reimbursed, as were "cover invoices" for expenses such as undeclared payments or bribes. Through the ''Kreuzzeitung,'' employees gained access to the highest circles in Germany and abroad. Because of its connections to politics and business, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' continued to be regarded among journalists as a training ground. The weekly ''Weltbühne'', for which the opposition ''Kreuzzeitung'' embodied the old German ruling class through and through, acknowledged the "old royalist ''Kreuzzeitung’s'' useful foreign policy information" and gladly employed journalists such as Lothar Persius who had learned their trade at the . And even ''Vorwärts

''Vorwärts'' (, "Forward") is a newspaper published by the Social Democratic Party of Germany (SPD). Founded in 1876, it was the central organ of the SPD for many decades. Following the party's Halle Congress (1891), it was published daily as ...

'', the party paper of the Social Democrats

Social democracy is a political, social, and economic philosophy within socialism that supports political and economic democracy. As a policy regime, it is described by academics as advocating economic and social interventions to promote so ...

, apparently had no qualms about a hiring a person like Hans Leuss, who had to leave the ''Kreuzzeitung'' because of his anti-Jewish agitation.

Jewish editors continued to work at the ''Kreuzzeitung''. The paper consciously set itself apart from the "ruckus anti-Semitism" of the Hugenberg press. While the paper cannot be described as in principle pro-Jewish, neither was it anti-Semitic. The personalities of the editors shaped the paper's political leanings. Some authors almost as a matter of course used colloquial expressions of the time such as "traitor’s reward” (), "Judas kiss" or "Judas politics". But non-Jewish politicians were also defamed as "Judas", since he was considered to be symbolic for a traitor.

The repositioning of some conservative parties left the editors stunned. The Centre Party, for example, had transformed itself from a Catholic-conservative party into a Christian-democratic people's party and until the end of the Weimar Republic was in a position to form coalitions with all political groupings. From that point on, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' primarily disparaged not communists or socialists, but politicians of the Centre Party. Their denomination played no fundamental role in this. The paper referred to the Catholic Centre politician Matthias Erzberger

Matthias Erzberger (20 September 1875 – 26 August 1921) was a German writer and politician (Centre Party), the minister of Finance from 1919 to 1920.

Prominent in the Catholic Centre Party, he spoke out against World War I from 1917 and as a ...

as a "corrupter of the country" and a "fulfillment politician" – one who was in favor of fulfilling the treaty obligations that ended World War I – just as it did the Catholic Centre deputies Heinrich Brauns

Heinrich Brauns (3 January 1868 – 19 October 1939) was a German politician and Roman Catholic theologian, who for the German Center Party was a long-serving Minister of Labour of the Weimar Republic from 1920 to 1928. Serving in a total of 13 ...

and Joseph Wirth

Karl Joseph Wirth (6 September 1879 – 3 January 1956) was a German politician of the Catholic Centre Party who served for one year and six months as the chancellor of Germany from 1921 to 1922, as the finance minister from 1920 to 1921, as a ...

, all of whom just a year earlier had explicitly identified with the Burgfrieden policy of Reich Chancellor Theobald von Bethmann Hollweg

Theobald Theodor Friedrich Alfred von Bethmann Hollweg (29 November 1856 – 1 January 1921) was a German politician who was the chancellor of the German Empire from 1909 to 1917. He oversaw the German entry into World War I. According to biog ...

.

On 17 November 1919 Georg Foertsch "massively attacked republican Reich ministers" in a ''Kreuzzeitung'' article. In it he proclaimed that the forces opposing "this corrupted revolutionary government are gaining ground daily” and concluded with the battle cry, "We or the others. That is our motto!" The new Reich government then filed a criminal complaint. Foertsch received a fine of 300 marks for defamation. In mitigation, the court took into account "that the ''Kreuzzeitung'' represented a point of view fundamentally opposed to the Reich government and that the author had worked himself into an irritated mood against the Reich government through his thoughts and writing".

Political direction

The paper in particular bolstered the conservativeBavarian People's Party

The Bavarian People's Party (german: Bayerische Volkspartei; BVP) was the Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria ...

(BVP), which split from the Centre Party after what are now known as Erzberger's reforms, which gave the German federal government supreme authority to tax and spend and sought a significant redistribution of the tax burden in favor of low to moderate income households. The BVP won more elections in Bavaria than any other party in all state elections until 1932. The BVP opposed republican centralism and initially called openly for secession from the German Reich. Journalistic support was provided by Erwein von Aretin, editor-in-chief of the ''Münchner Neuesten Nachrichten'' (''Munich’s Latest News'') who also sat on the corporate board of the ''Kreuzzeitung''. He belonged to the senior leadership of the monarchists in Bavaria and openly advocated separation of the Free State of Bavaria

Bavaria ( ; ), officially the Free State of Bavaria (german: Freistaat Bayern, link=no ), is a state in the south-east of Germany. With an area of , Bavaria is the largest German state by land area, comprising roughly a fifth of the total lan ...

from the Reich along with proclamation of a monarchy.

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' in the same way supported the monarchist wing of the German National People's Party

The German National People's Party (german: Deutschnationale Volkspartei, DNVP) was a national-conservative party in Germany during the Weimar Republic. Before the rise of the Nazi Party, it was the major conservative and nationalist party in Wei ...

(DNVP), which was led by Kuno von Westarp

Count Kuno Friedrich Viktor von Westarp (12 August 1864 – 30 July 1945) was a conservative politician in Germany.

Life and career

Westarp was born in Ludom (present-day Ludomy, Poland) in the Prussian Province of Posen, the son of a senior f ...

. For a time it was seen as the party best suited for implementing the ''Kreuzzeitung's'' own beliefs. Those included rejecting the Republic as constituted, the Treaty of Versailles

The Treaty of Versailles (french: Traité de Versailles; german: Versailler Vertrag, ) was the most important of the peace treaties of World War I. It ended the state of war between Germany and the Allied Powers. It was signed on 28 June ...

, and the reparation demands of the victorious powers.Karsten Schilling: ''Das zerstörte Erbe: Berliner Zeitungen der Weimarerer Republik im Portrait'' he Destroyed Legacy: Berlin Newspapers of the Weimar Republic in Portrait'.'' Dissertation. Norderstedt 2011, p. 411. A fundamentally Christian attitude admittedly always played a decisive role. Alfred Hugenberg's policy of rapprochement with the Nazi Party

The Nazi Party, officially the National Socialist German Workers' Party (german: Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei or NSDAP), was a far-right politics, far-right political party in Germany active between 1920 and 1945 that crea ...

met with criticism from the editor-in-chief as well as the corporate board of the ''Kreuzzeitung''. Specifically, they rejected in principle the exaggerated portrayal of Germanness by the German Nationalists as well as by National Socialism

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right politics, far-right Totalitarianism, totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hit ...

itself. The ''Kreuzzeitung'' openly rebuked the "Ur-Germanic fantasies" and the "neo-Communist terrorist actions of the National Socialist Party". It not only accused the Nazi Party of "betraying the idea of the nation"; it repeatedly described the way "millions of Germans are falling for the brown pied-pipery". Finally, in a major article on 5 December 1929, the editor-in-chief emphasized that the ''Kreuzzeitung'' was not the “megaphone of the DNVP" and "not in any way a German nationalist party organ".

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' also supported the paramilitary

The ''Kreuzzeitung'' also supported the paramilitary Stahlhelm

The ''Stahlhelm'' () is a German military steel combat helmet intended to provide protection against shrapnel and fragments of grenades. The term ''Stahlhelm'' refers both to a generic steel helmet and more specifically to the distinctive Ger ...

, but only conditionally in the person of Theodor Duesterberg

Theodor Duesterberg (; 19 October 1875 – 4 November 1950) was a leader of ''Der Stahlhelm'' in Germany prior to the Nazi seizure of power.

Background

Born the son of an army surgeon in Darmstadt, Duesterberg entered the Prussian Army in 18 ...

, whom the National Socialists had discredited because of his "not purely Aryan origin". During Duesterberg's candidacy in the 1932 German presidential election

Presidential elections were held in Germany on 13 March 1932, with a runoff on 10 April. Independent incumbent Paul von Hindenburg won a second seven-year term against Adolf Hitler of the National Socialist German Workers Party (NSDAP). Communis ...

, a steel helmet () was depicted above the Iron Cross in the newspaper's header, but this was only a means to an electoral end. Editor-in-chief Foertsch repeatedly exposed the Nazi Party's campaign methods, contended that "Hitler was not free of socialist thinking and was therefore a danger to Germany" and ran headlines such as "May the day come when the black-white-red flag flies again on government buildings" – referring to the flag of the German Empire used from 1871 to 1918.

The Stahlhelm had over 500,000 members and the DNVP almost one million. Both groups had their own party newspapers. Their members were never part of the target group of the ''Kreuzzeitung'', whose circulation remained constant at 7,200 until 1932. At no time did the paper come under the ownership of the Stahlhelm or the DNVP. Franz Seldte, the national leader of the Stahlhelm, owned Frundsberg Publishers in Berlin, through which he distributed several publications for the Stahlhelm. Alfred Hugenberg

Alfred Ernst Christian Alexander Hugenberg (19 June 1865 – 12 March 1951) was an influential German businessman and politician. An important figure in nationalist politics in Germany for the first few decades of the twentieth century, Hugenbe ...

owned more than 1,600 German newspapers, so that he too did not at any time need the ''Kreuzzeitung'' as a megaphone or party newspaper, although he would gladly have taken it over for reasons of prestige. The ''Kreuzzeitung's'' target group always remained the conservative upper class. This included the members of the German Gentlemen's Club. All of the ''Kreuzzeitung's'' corporate board belonged to it, as did Georg Foertsch as editor-in-chief. Many of the Gentlemen's Club's approximately 5,000 members were readers of the ''Kreuzzeitung''. They also provided the paper with information and gave it financial aid during the period of hyperinflation.

Reich President Paul von Hindenburg

Paul Ludwig Hans Anton von Beneckendorff und von Hindenburg (; abbreviated ; 2 October 1847 – 2 August 1934) was a German field marshal and statesman who led the Imperial German Army during World War I and later became President of Germany fro ...

, who was seen as the guarantor of the monarchy and the sole figure with the stature to restore it, received unlimited support from the ''Kreuzzeitung''. Hindenburg also occasionally leaked internal information to the paper and wrote short articles for it himself, which he had published via Kuno von Westarp. He had a legendary interview with the liberal ''Berliner Tageblatt

The ''Berliner Tageblatt'' or ''BT'' was a German language newspaper published in Berlin from 1872 to 1939. Along with the '' Frankfurter Zeitung'', it became one of the most important liberal German newspapers of its time.

History

The ''Berlin ...

'' which came about at the request of Hindenburg's press department. Hindenburg reluctantly agreed to the interview, took up, according to his own statements, "for the first time in his life one of those deadly world papers" and said in a defiant tone to his press chief: "But I will continue to read only the ''Kreuzzeitung''." Accordingly, the interview with Theodor Wolff

Theodor Wolff (2 August 1868 – 23 September 1943) was a German writer who was influential as a journalist, critic and newspaper editor. He was born and died in Berlin. Between 1906 and 1933 he was the chief editor of the politically liberal new ...

proceeded haltingly. Right at the beginning, when asked if he was familiar with the ''Berliner Tageblatt'', Hindenburg replied, "I have been used to reading the ''Kreuzzeitung'' with breakfast all my life". The rest of the conversation did not proceed any better, as Hindenburg did not risk talking to Wolff, the most influential representative of the Mosse Mosse may refer to:

Ethnic Groups

* Mossé of Burkina Faso Medicine

* Bartholomew Mosse (1712-1759), Irish surgeon and founder of the Rotunda Hospital

* Markus Mosse (1808-1865), German physician

Literature

* Hans Lachmann-Mosse (1885-1944), Germ ...

press, about either hunting or the military.

For the ''Kreuzzeitung,'' Hindenburg remained to the last the bearer of hope. He showed little inclination to confer the chancellorship on Hitler until shortly before 30 January 1933. As late as 12 August 1932, he rejected to good public effect Hitler's demand that "the leadership of the Reich government and all state power be conferred in full on me". The ''Kreuzzeitung'' praised Hindenburg's attitude toward Hitler as "understandable and well-founded". Granting Hitler's demands, the paper said, would have meant degrading the Reich president to a "puppet to be staged at ceremonial events dressed in a state robe". With this assessment, the ''Kreuzzeitung'' foreshadowed precisely the scenario that was to come about after Hitler seized power.

Economic collapse