Koala At Lone Pine Koala Sanctuary on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The koala or, inaccurately, koala bear (''Phascolarctos cinereus''), is an

The modern koala is the only

The modern koala is the only

The koala has one of the smallest brains in proportion to body weight of any mammal, being 60% smaller than that of a typical

The koala has one of the smallest brains in proportion to body weight of any mammal, being 60% smaller than that of a typical  The koala has several adaptations for its eucalypt diet, which is of low nutritive value, high toxicity, and high in

The koala has several adaptations for its eucalypt diet, which is of low nutritive value, high toxicity, and high in

arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the Animal locomotion, locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally, but others are exclusively arboreal. Th ...

herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

marsupial

Marsupials are any members of the mammalian infraclass Marsupialia. All extant marsupials are endemic to Australasia, Wallacea and the Americas. A distinctive characteristic common to most of these species is that the young are carried in a po ...

native to Australia. It is the only extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

representative of the family Phascolarctidae

The Phascolarctidae (''Žå╬¼Žā╬║Žē╬╗╬┐Žé (phaskolos)'' - pouch or bag, ''ß╝äŽü╬║Žä╬┐Žé (arktos)'' - bear, from the Greek ''phascolos'' + ''arctos'' meaning pouched bear) is a family of marsupials of the order Diprotodontia, consisting of only one ...

and its closest living relatives are the wombat

Wombats are short-legged, muscular quadrupedal marsupials that are native to Australia. They are about in length with small, stubby tails and weigh between . All three of the extant species are members of the family Vombatidae. They are adap ...

s. The koala is found in coastal areas of the mainland's eastern and southern regions, inhabiting Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

, and South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

. It is easily recognisable by its stout, tailless body and large head with round, fluffy ears and large, spoon-shaped nose. The koala has a body length of and weighs . Fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

colour ranges from silver grey to chocolate brown. Koalas from the northern populations are typically smaller and lighter in colour than their counterparts further south. These populations possibly are separate subspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

, but this is disputed.

Koalas typically inhabit open ''Eucalyptus

''Eucalyptus'' () is a genus of over seven hundred species of flowering trees, shrubs or mallees in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae. Along with several other genera in the tribe Eucalypteae, including '' Corymbia'', they are commonly known as euca ...

'' woodland, as the leaves of these trees make up most of their diet. Because this eucalypt diet has limited nutritional and caloric content, koalas are largely sedentary

Sedentary lifestyle is a lifestyle type, in which one is physically inactive and does little or no physical movement and or exercise. A person living a sedentary lifestyle is often sitting or lying down while engaged in an activity like soci ...

and sleep up to twenty hours a day. They are asocial animals, and bonding exists only between mothers and dependent offspring. Adult males communicate

Communication (from la, communicare, meaning "to share" or "to be in relation with") is usually defined as the transmission of information. The term may also refer to the message communicated through such transmissions or the field of inquir ...

with loud bellows that intimidate rivals and attract mates. Males mark their presence with secretions from scent gland

Scent gland are exocrine glands found in most mammals. They produce semi-viscous secretions which contain pheromones and other semiochemical compounds. These odor-messengers indicate information such as status, territorial marking, mood, and sexu ...

s located on their chests. Being marsupials, koalas give birth to underdeveloped young that crawl into their mothers' pouches, where they stay for the first six to seven months of their lives. These young koalas, known as joeys

The Australia national under-17 soccer team represents Australia in men's international under-17 soccer. The team is controlled by the governing body for Football in Australia, Football Federation Australia (FFA), which is currently a membe ...

, are fully weaned

Weaning is the process of gradually introducing an infant human or another mammal to what will be its adult diet while withdrawing the supply of its mother's milk.

The process takes place only in mammals, as only mammals produce milk. The infan ...

around a year old. Koalas have few natural predators and parasites, but are threatened by various pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, ŽĆ╬¼╬Ė╬┐Žé, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

s, such as Chlamydiaceae

The Chlamydiaceae are a family of gram-negative bacteria that belongs to the phylum Chlamydiota, order Chlamydiales. Chlamydiaceae species express the family-specific lipopolysaccharide epitope ╬▒Kdo-(2ŌåÆ8)-╬▒Kdo-(2ŌåÆ4)-╬▒Kdo (previously call ...

bacteria and the koala retrovirus

''Koala retrovirus'' (KoRV) is a retrovirus that is present in many populations of koalas. It has been implicated as the agent of koala immune deficiency syndrome (KIDS), an AIDS-like immunodeficiency that leaves infected koalas more susceptible ...

.

Because of its distinctive appearance, the koala along with the kangaroo

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

s are recognised worldwide as symbols of Australia. They were hunted by Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

and depicted in myths

Myth is a folklore genre consisting of Narrative, narratives that play a fundamental role in a society, such as foundational tales or Origin myth, origin myths. Since "myth" is widely used to imply that a story is not Objectivity (philosophy), ...

and cave art

In archaeology, Cave paintings are a type of parietal art (which category also includes petroglyphs, or engravings), found on the wall or ceilings of caves. The term usually implies prehistoric origin, and the oldest known are more than 40,000 ye ...

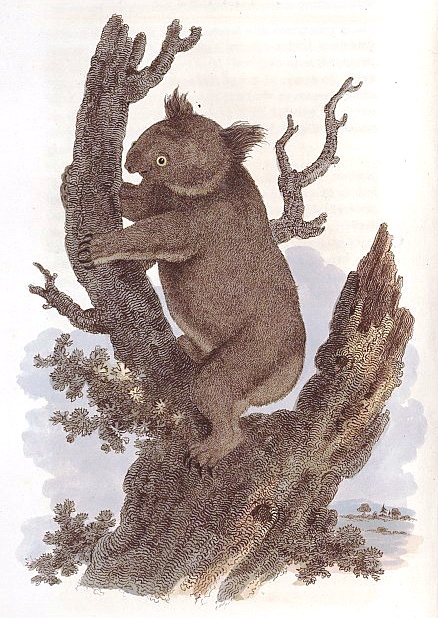

for millennia. The first recorded encounter between a European and a koala was in 1798, and an image of the animal was published in 1810 by naturalist George Perry. Botanist Robert Brown wrote the first detailed scientific description

Description is the pattern of narrative development that aims to make vivid a place, object, character, or group. Description is one of four rhetorical modes (also known as ''modes of discourse''), along with exposition, argumentation, and narr ...

of the koala in 1814, although his work remained unpublished for 180 years. Popular artist John Gould

John Gould (; 14 September 1804 ŌĆō 3 February 1881) was an English ornithologist. He published a number of monographs on birds, illustrated by plates produced by his wife, Elizabeth Gould, and several other artists, including Edward Lear, ...

illustrated and described the koala, introducing the species to the general British public. Further details about the animal's biology were revealed in the 19th century by several English scientists. Koalas are listed as a vulnerable species

A vulnerable species is a species which has been Conservation status, categorized by the International Union for Conservation of Nature as being threatened species, threatened with extinction unless the circumstances that are threatened species, ...

by the International Union for Conservation of Nature

The International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN; officially International Union for Conservation of Nature and Natural Resources) is an international organization working in the field of nature conservation and sustainable use of natu ...

. Among the many threats to their existence are habitat destruction

Habitat destruction (also termed habitat loss and habitat reduction) is the process by which a natural habitat becomes incapable of supporting its native species. The organisms that previously inhabited the site are displaced or dead, thereby ...

caused by agriculture, urbanisation, droughts, and associated bushfires

A wildfire, forest fire, bushfire, wildland fire or rural fire is an unplanned, uncontrolled and unpredictable fire in an area of combustible vegetation. Depending on the type of vegetation present, a wildfire may be more specifically identif ...

, some related to climate change. In February of 2022, the koala was officially listed as endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inva ...

in the Australian Capital Territory

The Australian Capital Territory (commonly abbreviated as ACT), known as the Federal Capital Territory (FCT) until 1938, is a landlocked federal territory of Australia containing the national capital Canberra and some surrounding townships. ...

, New South Wales, and Queensland.

Etymology

The word koala comes from theDharug

The Dharug or Darug people, formerly known as the Broken Bay tribe, are an Aboriginal Australian people, who share strong ties of kinship and, in pre-colonial times, lived as skilled hunters in family groups or clans, scattered throughout much ...

''gula'', meaning ''no water''. Although the vowel 'u' was originally written in the English orthography

English orthography is the writing system used to represent spoken English, allowing readers to connect the graphemes to sound and to meaning. It includes English's norms of spelling, hyphenation, capitalisation, word breaks, emphasis, and p ...

as "oo" (in spellings such as ''coola'' or ''koolah'' ŌĆö two syllables), later became "oa" and is now pronounced in three syllables, possibly in error.

Adopted by white settlers, "koala" became one of several hundred Aboriginal loan words in Australian English, where it was also commonly referred to as "native bear", later "koala bear", for its supposed resemblance to a bear. It is also one of several Aboriginal words that made it into International English

International English is the concept of using the English language as a global means of communication similar to an international auxiliary language, and often refers to the movement towards an international standard for the language. Relat ...

, alongside e.g. "didgeridoo

The didgeridoo (; also spelt didjeridu, among other variants) is a wind instrument, played with vibrating lips to produce a continuous drone while using a special breathing technique called circular breathing. The didgeridoo was developed by ...

" and "kangaroo

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

." The generic

Generic or generics may refer to:

In business

* Generic term, a common name used for a range or class of similar things not protected by trademark

* Generic brand, a brand for a product that does not have an associated brand or trademark, other ...

name, ''Phascolarctos

''Phascolarctos'' is a genus of marsupials with one living species, the koala ''Phascolarctos cinereus'', an iconic animal of Australia. Several extinct species of the genus are known from fossil material, these were also large tree dwellers that ...

'', is derived from the Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

words ''phaskolos'' "pouch" and ''arktos'' "bear". The specific name Specific name may refer to:

* in Database management systems, a system-assigned name that is unique within a particular database

In taxonomy, either of these two meanings, each with its own set of rules:

* Specific name (botany), the two-part (bino ...

, ''cinereus'', is Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power of the ...

for "ash coloured".

Taxonomy and evolution

The koala was given its generic name ''Phascolarctos'' in 1816 by French zoologistHenri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville

Henri Marie Ducrotay de Blainville (; 12 September 1777 ŌĆō 1 May 1850) was a French zoologist and anatomist.

Life

Blainville was born at Arques, near Dieppe. As a young man he went to Paris to study art, but ultimately devoted himself to natur ...

, who would not give it a specific name until further review. In 1819, German zoologist Georg August Goldfuss

Georg August Goldfuss (Goldfu├¤, 18 April 1782 ŌĆō 2 October 1848) was a German palaeontologist, zoologist and botanist.

Goldfuss was born at Thurnau near Bayreuth. He was educated at Erlangen, where he graduated PhD in 1804 and became profe ...

gave it the binomial

Binomial may refer to:

In mathematics

*Binomial (polynomial), a polynomial with two terms

* Binomial coefficient, numbers appearing in the expansions of powers of binomials

*Binomial QMF, a perfect-reconstruction orthogonal wavelet decomposition

...

''Lipurus cinereus''. Because ''Phascolarctos'' was published first, according to the International Code of Zoological Nomenclature

The International Code of Zoological Nomenclature (ICZN) is a widely accepted convention in zoology that rules the formal scientific naming of organisms treated as animals. It is also informally known as the ICZN Code, for its publisher, the ...

, it has priority as the official name of the genus. French naturalist Anselme Gaëtan Desmarest

Anselme Ga├½tan Desmarest (6 March 1784 ŌĆō 4 June 1838) was a French Zoology, zoologist and author. He was the son of Nicolas Desmarest and father of Eug├©ne Anselme S├®bastien L├®on Desmarest. Desmarest was a disciple of Georges Cuvier and Alex ...

proposed the name ''Phascolarctos fuscus'' in 1820, suggesting that the brown-coloured versions were a different species than the grey ones. Other names suggested by European authors included ''Marodactylus cinereus'' by Goldfuss in 1820, ''P. flindersii'' by Ren├® Primev├©re Lesson

Ren├® (''born again'' or ''reborn'' in French) is a common first name in French-speaking, Spanish-speaking, and German-speaking countries. It derives from the Latin name Renatus.

Ren├® is the masculine form of the name (Ren├®e being the feminine ...

in 1827, and ''P. koala'' by John Edward Gray

John Edward Gray, FRS (12 February 1800 ŌĆō 7 March 1875) was a British zoologist. He was the elder brother of zoologist George Robert Gray and son of the pharmacologist and botanist Samuel Frederick Gray (1766ŌĆō1828). The same is used for ...

in 1827.

The koala is classified with wombat

Wombats are short-legged, muscular quadrupedal marsupials that are native to Australia. They are about in length with small, stubby tails and weigh between . All three of the extant species are members of the family Vombatidae. They are adap ...

s (family Vombatidae) and several extinct families (including marsupial tapirs, marsupial lions and giant wombats) in the suborder Vombatiformes

The Vombatiformes are one of the three suborders of the large marsupial order Diprotodontia. Seven of the nine known families within this suborder are extinct; only the families Phascolarctidae, with the koala, and Vombatidae, with three extant ...

within the order Diprotodontia

Diprotodontia (, from Greek language, Greek "two forward teeth") is the largest extant order (biology), order of marsupials, with about 155 species, including the kangaroos, Wallaby, wallabies, Phalangeriformes, possums, koala, wombats, and many ...

. The Vombatiformes are a sister group

In phylogenetics, a sister group or sister taxon, also called an adelphotaxon, comprises the closest relative(s) of another given unit in an evolutionary tree.

Definition

The expression is most easily illustrated by a cladogram:

Taxon A and t ...

to a clade

A clade (), also known as a monophyletic group or natural group, is a group of organisms that are monophyletic ŌĆō that is, composed of a common ancestor and all its lineal descendants ŌĆō on a phylogenetic tree. Rather than the English term, ...

that includes macropods

Macropod may refer to:

* Macropodidae, a marsupial family which includes kangaroos, wallabies, tree-kangaroos, pademelons, and several others

* Macropodiformes

The Macropodiformes , also known as macropods, are one of the three suborders of the ...

(kangaroo

Kangaroos are four marsupials from the family Macropodidae (macropods, meaning "large foot"). In common use the term is used to describe the largest species from this family, the red kangaroo, as well as the antilopine kangaroo, eastern gre ...

s and wallabies

A wallaby () is a small or middle-sized macropod native to Australia and New Guinea, with introduced populations in New Zealand, Hawaii, the United Kingdom and other countries. They belong to the same taxonomic family as kangaroos and so ...

) and possums

Possum may refer to:

Animals

* Phalangeriformes, or possums, any of a number of arboreal marsupial species native to Australia, New Guinea, and Sulawesi

** Common brushtail possum (''Trichosurus vulpecula''), a common possum in Australian urban a ...

. The ancestors of vombatiforms were likely arboreal

Arboreal locomotion is the Animal locomotion, locomotion of animals in trees. In habitats in which trees are present, animals have evolved to move in them. Some animals may scale trees only occasionally, but others are exclusively arboreal. Th ...

, and the koala's lineage

Lineage may refer to:

Science

* Lineage (anthropology), a group that can demonstrate its common descent from an apical ancestor or a direct line of descent from an ancestor

* Lineage (evolution), a temporal sequence of individuals, populati ...

was possibly the first to branch off around 40 million years ago during the Eocene

The Eocene ( ) Epoch is a geological epoch (geology), epoch that lasted from about 56 to 33.9 million years ago (mya). It is the second epoch of the Paleogene Period (geology), Period in the modern Cenozoic Era (geology), Era. The name ''Eocene' ...

.

extant

Extant is the opposite of the word extinct. It may refer to:

* Extant hereditary titles

* Extant literature, surviving literature, such as ''Beowulf'', the oldest extant manuscript written in English

* Extant taxon, a taxon which is not extinct, ...

member of Phascolarctidae

The Phascolarctidae (''Žå╬¼Žā╬║Žē╬╗╬┐Žé (phaskolos)'' - pouch or bag, ''ß╝äŽü╬║Žä╬┐Žé (arktos)'' - bear, from the Greek ''phascolos'' + ''arctos'' meaning pouched bear) is a family of marsupials of the order Diprotodontia, consisting of only one ...

, a family that once included several genera and species. During the Oligocene

The Oligocene ( ) is a geologic epoch of the Paleogene Period and extends from about 33.9 million to 23 million years before the present ( to ). As with other older geologic periods, the rock beds that define the epoch are well identified but the ...

and Miocene

The Miocene ( ) is the first geological epoch of the Neogene Period and extends from about (Ma). The Miocene was named by Scottish geologist Charles Lyell; the name comes from the Greek words (', "less") and (', "new") and means "less recen ...

, koalas lived in rainforest

Rainforests are characterized by a closed and continuous tree canopy, moisture-dependent vegetation, the presence of epiphytes and lianas and the absence of wildfire. Rainforest can be classified as tropical rainforest or temperate rainfores ...

s and had less specialised diets. Some species, such as the Riversleigh rainforest koala

The Riversleigh rainforest koala (''Nimiokoala greystanesi'') is an extinct marsupial, closely related to the extant koala, that inhabited northwestern Queensland in the early-middle Miocene (23ŌĆō16 million years ago). Along with species o ...

(''Nimiokoala greystanesi'') and some species of ''Perikoala

''Perikoala'' is an extinct genus of marsupials, related to the modern koala. The genus diverged from a common ancestor of the other koala genera ''Nimiokoala'', ''Litokoala'', and ''Phascolarctos'', which contains the living koala.

Two species ...

'', were around the same size as the modern koala, while others, such as species of ''Litokoala

''Litokoala'' is an extinct genus of marsupials, and along with '' Nimiokoala'', is closely related to the modern koala. The three genera may have diverged at an earlier date, although the drying of the continent and the expansion of ''Eucalyptu ...

'', were one-half to two-thirds its size. Like the modern species, prehistoric koalas had well developed ear structures which suggests that long-distance vocalising and sedentism developed early. During the Miocene, the Australian continent began drying out, leading to the decline of rainforests and the spread of open ''Eucalyptus

''Eucalyptus'' () is a genus of over seven hundred species of flowering trees, shrubs or mallees in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae. Along with several other genera in the tribe Eucalypteae, including '' Corymbia'', they are commonly known as euca ...

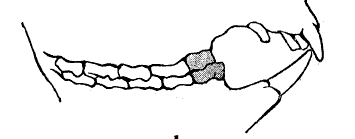

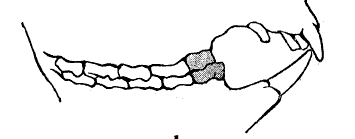

'' woodlands. The genus ''Phascolarctos'' split from ''Litokoala'' in the late Miocene and had several adaptations that allowed it to live on a specialised eucalyptus diet: a shifting of the palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly sepa ...

towards the front of the skull; larger molars

The molars or molar teeth are large, flat teeth at the back of the mouth. They are more developed in mammals. They are used primarily to grind food during chewing. The name ''molar'' derives from Latin, ''molaris dens'', meaning "millstone to ...

and premolar

The premolars, also called premolar teeth, or bicuspids, are transitional teeth located between the canine and molar teeth. In humans, there are two premolars per quadrant in the permanent set of teeth, making eight premolars total in the mouth ...

s; smaller pterygoid fossa

The pterygoid fossa is an anatomical term for the fossa formed by the divergence of the lateral pterygoid plate and the medial pterygoid plate of the sphenoid bone.

Structure

The lateral and medial pterygoid plates (of the pterygoid process of ...

; and a larger gap between the molar and the incisor

Incisors (from Latin ''incidere'', "to cut") are the front teeth present in most mammals. They are located in the premaxilla above and on the mandible below. Humans have a total of eight (two on each side, top and bottom). Opossums have 18, whe ...

teeth.

''P. cinereus'' may have emerged as a dwarf form of the giant koala

The giant koala (''Phascolarctos stirtoni'') is an extinct arboreal marsupial which existed in Australia during the Pleistocene epoch. ''Phascolarctos stirtoni'' was about one third larger than the contemporary koala, ''P. cinereus'', and has had ...

(''P. stirtoni''). The reduction in the size of large mammals has been seen as a common phenomenon worldwide during the late Pleistocene

The Late Pleistocene is an unofficial Age (geology), age in the international geologic timescale in chronostratigraphy, also known as Upper Pleistocene from a Stratigraphy, stratigraphic perspective. It is intended to be the fourth division of ...

, and several Australian mammals, such as the agile wallaby

The agile wallaby (''Notamacropus agilis''), also known as the sandy wallaby, is a species of wallaby found in northern Australia and southern New Guinea. It is the most common wallaby in north Australia. The agile wallaby is a sandy colour, beco ...

, are traditionally believed to have resulted from this dwarfing. A 2008 study questions this hypothesis, noting that ''P. cinereus'' and ''P. stirtoni'' were sympatric

In biology, two related species or populations are considered sympatric when they exist in the same geographic area and thus frequently encounter one another. An initially interbreeding population that splits into two or more distinct species sh ...

during the middle to late Pleistocene, and possibly as early as the Pliocene. The fossil record of the modern koala extends back at least to the middle Pleistocene.

Genetics and variations

Threesubspecies

In biological classification, subspecies is a rank below species, used for populations that live in different areas and vary in size, shape, or other physical characteristics (morphology), but that can successfully interbreed. Not all species ...

are recognised: the Queensland koala (''Phascolarctos cinereus adustus'', Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225ŌĆō1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the Ap ...

1923), the New South Wales koala (''Phascolarctos cinereus cinereus'', Goldfuss 1817), and the Victorian koala (''Phascolarctos cinereus victor'', Troughton Troughton is a surname, and may refer to

* Alice Troughton, British film and television director, not related to Patrick Troughton

* Bob Troughton (1904ŌĆō1988), Australian rules footballer

* Charles Troughton (1916ŌĆō1991), British businessman

* ...

1935). These forms are distinguished by pelage

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily #Guard hair, guard hair on top and thick #Down hair, underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as ...

colour and thickness, body size, and skull shape. The Queensland koala is the smallest of the three, with shorter, silver fur and a shorter skull. The Victorian koala is the largest, with shaggier, brown fur and a wider skull. The boundaries of these variations are based on state borders, and their status as subspecies is disputed. A 1999 genetic study suggests that the variations represent differentiated populations with limited gene flow

In population genetics, gene flow (also known as gene migration or geneflow and allele flow) is the transfer of genetic material from one population to another. If the rate of gene flow is high enough, then two populations will have equivalent a ...

between them and that the three subspecies comprise a single evolutionarily significant unit An evolutionarily significant unit (ESU) is a population of organisms that is considered distinct for purposes of conservation. Delineating ESUs is important when considering conservation action.

This term can apply to any species, subspecies, geo ...

. Other studies have found that koala populations have high levels of inbreeding

Inbreeding is the production of offspring from the mating or breeding of individuals or organisms that are closely related genetically. By analogy, the term is used in human reproduction, but more commonly refers to the genetic disorders and o ...

and low genetic variation

Genetic variation is the difference in DNA among individuals or the differences between populations. The multiple sources of genetic variation include mutation and genetic recombination. Mutations are the ultimate sources of genetic variation, ...

. Such low genetic diversity

Genetic diversity is the total number of genetic characteristics in the genetic makeup of a species, it ranges widely from the number of species to differences within species and can be attributed to the span of survival for a species. It is dis ...

may have been a characteristic of koala populations since the late Pleistocene. Rivers and roads have been shown to limit gene flow and contribute to the genetic differentiation of southeast Queensland populations. In April 2013, scientists from the Australian Museum

The Australian Museum is a heritage-listed museum at 1 William Street, Sydney central business district, New South Wales, Australia. It is the oldest museum in Australia,Design 5, 2016, p.1 and the fifth oldest natural history museum in the ...

and Queensland University of Technology

Queensland University of Technology (QUT) is a public research university located in the urban coastal city of Brisbane, Queensland, Australia. QUT is located on two campuses in the Brisbane area viz. Gardens Point and Kelvin Grove. The univ ...

announced they had fully sequenced the koala genome

In the fields of molecular biology and genetics, a genome is all the genetic information of an organism. It consists of nucleotide sequences of DNA (or RNA in RNA viruses). The nuclear genome includes protein-coding genes and non-coding ge ...

.

Characteristics and adaptations

The koala is a stocky animal with a large head andvestigial

Vestigiality is the retention, during the process of evolution, of genetically determined structures or attributes that have lost some or all of the ancestral function in a given species. Assessment of the vestigiality must generally rely on co ...

or non-existent tail. It has a body length of and a weight of , making it among the largest arboreal marsupials. Koalas from Victoria are twice as heavy as those from Queensland. The species is sexually dimorphic

Sexual dimorphism is the condition where the sexes of the same animal and/or plant species exhibit different morphological characteristics, particularly characteristics not directly involved in reproduction. The condition occurs in most ani ...

, with males 50% larger than females. Males are further distinguished from females by their more curved noses and the presence of chest glands, which are visible as hairless patches. As in most marsupials, the male koala has a bifurcated penis, and the female has two lateral vagina

In mammals, the vagina is the elastic, muscular part of the female genital tract. In humans, it extends from the vestibule to the cervix. The outer vaginal opening is normally partly covered by a thin layer of mucosal tissue called the hymen ...

s and two separate uteri

The uterus (from Latin ''uterus'', plural ''uteri'') or womb () is the organ in the reproductive system of most female mammals, including humans that accommodates the embryonic and fetal development of one or more embryos until birth. The uteru ...

. The male's penile sheath

Almost all mammal penises have foreskins or prepuce, although in non-human cases the foreskin is usually a sheath (sometimes called the ''preputial sheath'', ''praeputium'' or ''penile sheath'') into which the whole penis is retracted. In koalas, ...

contains naturally occurring bacteria that play an important role in fertilisation

Fertilisation or fertilization (see spelling differences), also known as generative fertilisation, syngamy and impregnation, is the fusion of gametes to give rise to a new individual organism or offspring and initiate its development. Proce ...

. The female's pouch opening is tightened by a sphincter

A sphincter is a circular muscle that normally maintains constriction of a natural body passage or orifice and which relaxes as required by normal physiological functioning. Sphincters are found in many animals. There are over 60 types in the hum ...

that keeps the young from falling out.

The pelage of the koala is thicker and longer on the back, and shorter on the belly. The ears have thick fur on both the inside and outside. The back fur colour varies from light grey to chocolate brown. The belly fur is whitish; on the rump it is dappled whitish, and darker at the back. The koala has the most effective insulating back fur of any marsupial and is highly resilient to wind and rain, while the belly fur can reflect solar radiation. The koala's curved, sharp claws are well adapted for climbing trees. The large forepaws have two opposable digits (the first and second, which are opposable to the other three) that allow them to grasp small branches. On the hind paws, the second and third digits are fused, a typical condition for members of the Diprotodontia, and the attached claws (which are still separate) are used for grooming. As in humans and other primates

Primates are a diverse order of mammals. They are divided into the strepsirrhines, which include the lemurs, galagos, and lorisids, and the haplorhines, which include the tarsiers and the simians (monkeys and apes, the latter including huma ...

, koalas have friction ridges on their paws. The animal has a sturdy skeleton and a short, muscular upper body with proportionately long upper limbs that contribute to its climbing and grasping abilities. Additional climbing strength is achieved with thigh muscles that attach to the shinbone

The tibia (; ), also known as the shinbone or shankbone, is the larger, stronger, and anterior (frontal) of the two bones in the leg below the knee in vertebrates (the other being the fibula, behind and to the outside of the tibia); it connects ...

lower than other animals. The koala has a cartilaginous

Cartilage is a resilient and smooth type of connective tissue. In tetrapods, it covers and protects the ends of long bones at the joints as articular cartilage, and is a structural component of many body parts including the rib cage, the neck and ...

pad at the end of the spine that may make it more comfortable when it perches in the fork of a tree.

The koala has one of the smallest brains in proportion to body weight of any mammal, being 60% smaller than that of a typical

The koala has one of the smallest brains in proportion to body weight of any mammal, being 60% smaller than that of a typical diprotodont

Diprotodontia (, from Greek "two forward teeth") is the largest extant order of marsupials, with about 155 species, including the kangaroos, wallabies, possums, koala, wombats, and many others. Extinct diprotodonts include the hippopotamus-sized ...

, weighing only on average. The brain's surface is fairly smooth, typical for a " primitive" animal. It occupies only 61% of the cranial cavity

The cranial cavity, also known as intracranial space, is the space within the skull that accommodates the brain. The skull minus the mandible is called the ''cranium''. The cavity is formed by eight cranial bones known as the neurocranium that in ...

and is pressed against the inside surface by cerebrospinal fluid

Cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) is a clear, colorless body fluid found within the tissue that surrounds the brain and spinal cord of all vertebrates.

CSF is produced by specialised ependymal cells in the choroid plexus of the ventricles of the bra ...

. The function of this relatively large amount of fluid is not known, although one possibility is that it acts as a shock absorber, cushioning the brain if the animal falls from a tree. The koala's small brain size may be an adaptation to the energy restrictions imposed by its diet, which is insufficient to sustain a larger brain. Because of its small brain, the koala has a limited ability to perform complex, unfamiliar behaviours. For example, when presented with plucked leaves on a flat surface, the animal cannot adapt to the change in its normal feeding routine and will not eat the leaves. The koala's olfactory

The sense of smell, or olfaction, is the special sense through which smells (or odors) are perceived. The sense of smell has many functions, including detecting desirable foods, hazards, and pheromones, and plays a role in taste.

In humans, it ...

senses are normal, and it is known to sniff the oils of individual branchlets to assess their edibility. Its nose is fairly large and covered in leathery skin. Its round ears provide it with good hearing, and it has a well-developed middle ear

The middle ear is the portion of the ear medial to the eardrum, and distal to the oval window of the cochlea (of the inner ear).

The mammalian middle ear contains three ossicles, which transfer the vibrations of the eardrum into waves in the ...

. A koala's vision is not well developed, and its relatively small eyes are unusual among marsupials in that the pupils have vertical slits. Koalas make use of a novel vocal organ to produce low-pitched sounds (see social spacing, below). Unlike typical mammalian vocal cords

In humans, vocal cords, also known as vocal folds or voice reeds, are folds of throat tissues that are key in creating sounds through vocalization. The size of vocal cords affects the pitch of voice. Open when breathing and vibrating for speech ...

, which are folds in the larynx, these organs are placed in the velum (soft palate

The soft palate (also known as the velum, palatal velum, or muscular palate) is, in mammals, the soft tissue constituting the back of the roof of the mouth. The soft palate is part of the palate of the mouth; the other part is the hard palate. ...

) and are called velar vocal cords.

The koala has several adaptations for its eucalypt diet, which is of low nutritive value, high toxicity, and high in

The koala has several adaptations for its eucalypt diet, which is of low nutritive value, high toxicity, and high in dietary fibre

Dietary fiber (in British English fibre) or roughage is the portion of plant-derived food that cannot be completely broken down by human digestive enzymes. Dietary fibers are diverse in chemical composition, and can be grouped generally by the ...

. The animal's dentition

Dentition pertains to the development of teeth and their arrangement in the mouth. In particular, it is the characteristic arrangement, kind, and number of teeth in a given species at a given age. That is, the number, type, and morpho-physiolo ...

consists of the incisors and cheek teeth

Cheek teeth or post-canines comprise the molar and premolar teeth in mammals. Cheek teeth are multicuspidate (having many folds or tubercles). Mammals have multicuspidate molars (three in placentals, four in marsupials, in each jaw quadrant) and ...

(a single premolar and four molars on each jaw), which are separated by a large gap (a characteristic feature of herbivorous mammals). The incisors are used for grasping leaves, which are then passed to the premolars to be snipped at the petiole before being passed to the highly cusped molars, where they are shredded into small pieces. Koalas may also store food in their cheek pouch

Cheek pouches are pockets on both sides of the head of some mammals between the jaw and the cheek. They can be found on mammals including the platypus, some rodents, and most monkeys, as well as the marsupial koala. The cheek pouches of chipmunks ...

es before it is ready to be chewed. The partially worn molars of middle-aged koalas are optimal for breaking the leaves into small particles, resulting in more efficient stomach digestion and nutrient absorption in the small intestine, which digests the eucalyptus leaves to provide most of the animal's energy. A koala sometimes regurgitates the food into the mouth to be chewed a second time.

Unlike kangaroos and eucalyptus-eating possums, koalas are hindgut fermenters

Hindgut fermentation is a digestive process seen in monogastric herbivores, animals with a simple, single-chambered stomach. Cellulose is digested with the aid of symbiotic bacteria. This is made possible by the extraordinary length of their

Koalas are

Koalas are

Adult males communicate with loud bellowsŌĆölow pitched sounds that consist of snore-like inhalations and

Adult males communicate with loud bellowsŌĆölow pitched sounds that consist of snore-like inhalations and

Koalas are seasonal breeders, and births take place from the middle of spring through the summer to early autumn, from October to May. Females in

Koalas are seasonal breeders, and births take place from the middle of spring through the summer to early autumn, from October to May. Females in  As the young koala approaches six months, the mother begins to prepare it for its eucalyptus diet by predigesting the leaves, producing a faecal pap that the joey eats from her

As the young koala approaches six months, the mother begins to prepare it for its eucalyptus diet by predigesting the leaves, producing a faecal pap that the joey eats from her

The first written reference to the koala was recorded by John Price, servant of John Hunter, the

The first written reference to the koala was recorded by John Price, servant of John Hunter, the  Naturalist and popular artist

Naturalist and popular artist

The

The

The koala was originally classified as

The koala was originally classified as

images and movies of the koala ''Phascolarctos cinereus''

Animal Diversity Web ŌĆō ''Phascolarctos cinereus''

*iNaturalist crowdsource

koala sighting photos

(mapped, graphed)

Koala Science Community

ŌĆō an

"Koalas deserve full protection"

Cracking the Koala Code

ŌĆō a

The Aussie Koala Ark Conservation Project

{{Taxonbar, from=Q36101 Articles containing video clips Clawed herbivores Extant Middle Pleistocene first appearances Herbivorous mammals Mammals described in 1817 Mammals of New South Wales Mammals of Queensland Mammals of South Australia Mammals of Victoria (Australia) Marsupials of Australia Vombatiforms

caecum

The cecum or caecum is a pouch within the peritoneum that is considered to be the beginning of the large intestine. It is typically located on the right side of the body (the same side of the body as the appendix, to which it is joined). The w ...

ŌĆö long and in diameterŌĆöthe largest proportionally of any animal. Koalas can select which food particles to retain for longer fermentation and which to pass through. Large particles typically pass through more quickly, as they would take more time to digest. While the hindgut is proportionally larger in the koala than in other herbivores, only 10% of the animal's energy is obtained from fermentation. Since the koala gains a low amount of energy from its diet, its metabolic rate

Metabolism (, from el, ╬╝╬ĄŽä╬▒╬▓╬┐╬╗╬« ''metabol─ō'', "change") is the set of life-sustaining chemical reactions in organisms. The three main functions of metabolism are: the conversion of the energy in food to energy available to run cell ...

is half that of a typical mammal, although this can vary between seasons and sexes. They can digest the toxins present in eucalyptus leaves due to their production of cytochrome P450

Cytochromes P450 (CYPs) are a Protein superfamily, superfamily of enzymes containing heme as a cofactor (biochemistry), cofactor that functions as monooxygenases. In mammals, these proteins oxidize steroids, fatty acids, and xenobiotics, and are ...

, which breaks down these poisons in the liver

The liver is a major Organ (anatomy), organ only found in vertebrates which performs many essential biological functions such as detoxification of the organism, and the Protein biosynthesis, synthesis of proteins and biochemicals necessary for ...

. The koala conserves water by passing relatively dry faecal pellets high in undigested fibre, and by storing water in the caecum.

Distribution and habitat

The koala's geographic range covers roughly , and 30ecoregion

An ecoregion (ecological region) or ecozone (ecological zone) is an ecologically and geographically defined area that is smaller than a bioregion, which in turn is smaller than a biogeographic realm. Ecoregions cover relatively large areas of l ...

s. It extends throughout eastern and southeastern Australia, encompassing northeastern, central and southeastern Queensland, eastern New South Wales, Victoria, and southeastern South Australia

South Australia (commonly abbreviated as SA) is a state in the southern central part of Australia. It covers some of the most arid parts of the country. With a total land area of , it is the fourth-largest of Australia's states and territories ...

. The koala was reintroduced

Species reintroduction is the deliberate release of a species into the wild, from captivity or other areas where the organism is capable of survival. The goal of species reintroduction is to establish a healthy, genetically diverse, self-sustainin ...

near Adelaide

Adelaide ( ) is the capital city of South Australia, the state's largest city and the fifth-most populous city in Australia. "Adelaide" may refer to either Greater Adelaide (including the Adelaide Hills) or the Adelaide city centre. The dem ...

and on several islands, including Kangaroo Island

Kangaroo Island, also known as Karta Pintingga (literally 'Island of the Dead' in the language of the Kaurna people), is Australia's third-largest island, after Tasmania and Melville Island. It lies in the state of South Australia, southwest ...

and French Island French Island can refer to:

*French Island (Victoria), in Australia

*French Island, Wisconsin, in the United States

* French Island No. 1 and French Island No. 2 in the Ohio River in Kentucky

*French Island, an island in Ellis Pond, Oxford County, ...

. The population on Magnetic Island

Magnetic Island ( Wulguru: Yunbenun) is an island offshore from the city of Townsville, Queensland, Australia. This mountainous island in Cleveland Bay has effectively become a suburb of Townsville, with 2,335 permanent residents. The island ...

represents the northern limit of its range. Fossil evidence shows that the koala's range stretched as far west as southwestern Western Australia

Western Australia (commonly abbreviated as WA) is a state of Australia occupying the western percent of the land area of Australia excluding external territories. It is bounded by the Indian Ocean to the north and west, the Southern Ocean to th ...

during the late Pleistocene. Koalas were introduced to Western Australia at Yanchep. They were likely driven to extinction in these areas by environmental changes and hunting by Indigenous Australians

Indigenous Australians or Australian First Nations are people with familial heritage from, and membership in, the ethnic groups that lived in Australia before British colonisation. They consist of two distinct groups: the Aboriginal peoples ...

. In South Australia, koalas were only known to exist in recent times in the lower South East, with a remnant population in the Bangham Forest between Bordertown and Naracoorte, until introduced to the Mount Lofty Ranges

The Mount Lofty Ranges are a range of mountains in the Australian state of South Australia which for a small part of its length borders the east of Adelaide. The part of the range in the vicinity of Adelaide is called the Adelaide Hills and ...

in the 20th-century. Doubts have been cast on Eyre's identification as koala pelt a girdle being worn by an Aboriginal man, the only evidence of their existence elsewhere in the State.

Koalas can be found in habitats ranging from relatively open forests to woodland

A woodland () is, in the broad sense, land covered with trees, or in a narrow sense, synonymous with wood (or in the U.S., the ''plurale tantum'' woods), a low-density forest forming open habitats with plenty of sunlight and limited shade (see ...

s, and in climates ranging from tropical to cool temperate

In geography, the temperate climates of Earth occur in the middle latitudes (23.5┬░ to 66.5┬░ N/S of Equator), which span between the tropics and the polar regions of Earth. These zones generally have wider temperature ranges throughout t ...

. In semi-arid climate

A semi-arid climate, semi-desert climate, or steppe climate is a dry climate sub-type. It is located on regions that receive precipitation below potential evapotranspiration, but not as low as a desert climate. There are different kinds of semi-ar ...

s, they prefer riparian habitat

A riparian zone or riparian area is the interface between land and a river or stream. Riparian is also the proper nomenclature for one of the terrestrial biomes of the Earth. Plant habitats and communities along the river margins and banks ar ...

s, where nearby streams and creeks provide refuge during times of drought and extreme heat.

Ecology and behaviour

Foraging and activities

Koalas are

Koalas are herbivorous

A herbivore is an animal anatomically and physiologically adapted to eating plant material, for example foliage or marine algae, for the main component of its diet. As a result of their plant diet, herbivorous animals typically have mouthpart ...

, and while most of their diet consists of eucalypt

Eucalypt is a descriptive name for woody plants with capsule fruiting bodies belonging to seven closely related genera (of the tribe Eucalypteae) found across Australasia:

''Eucalyptus'', '' Corymbia'', '' Angophora'', ''Stockwellia'', ''Allosyn ...

leaves, they can be found in trees of other genera, such as ''Acacia

''Acacia'', commonly known as the wattles or acacias, is a large genus of shrubs and trees in the subfamily Mimosoideae of the pea family Fabaceae. Initially, it comprised a group of plant species native to Africa and Australasia. The genus na ...

'', ''Allocasuarina

''Allocasuarina'' is a genus of trees in the flowering plant family Casuarinaceae. They are endemic to Australia, occurring primarily in the south. Like the closely related genus ''Casuarina'', they are commonly called sheoaks or she-oaks.

Wi ...

'', ''Callitris

''Callitris'' is a genus of coniferous trees in the Cupressaceae (cypress family). There are 16 recognized species in the genus, of which 13 are native to Australia and the other three (''C. neocaledonica, C. sulcata'' and ''C. p ...

'', ''Leptospermum

''Leptospermum'' is a genus of shrubs and small trees in the myrtle family Myrtaceae commonly known as tea trees, although this name is sometimes also used for some species of ''Melaleuca''. Most species are endemic to Australia, with the greate ...

'', and ''Melaleuca

''Melaleuca'' () is a genus of nearly 300 species of plants in the myrtle family, Myrtaceae, commonly known as paperbarks, honey-myrtles or tea-trees (although the last name is also applied to species of '' Leptospermum''). They range in size ...

''. Though the foliage of over 600 species of ''Eucalyptus'' is available, the koala shows a strong preference for around 30. They tend to choose species that have a high protein

Proteins are large biomolecules and macromolecules that comprise one or more long chains of amino acid residues. Proteins perform a vast array of functions within organisms, including catalysing metabolic reactions, DNA replication, respo ...

content and low proportions of fibre and lignin

Lignin is a class of complex organic polymers that form key structural materials in the support tissues of most plants. Lignins are particularly important in the formation of cell walls, especially in wood and bark, because they lend rigidity ...

. The most favoured species are ''Eucalyptus microcorys

''Eucalyptus microcorys'', commonly known as tallowwood, is a species of medium to tall tree that is endemic to eastern Australia. It has rough, fibrous or string bark on the trunk and branches, lance-shaped to egg-shaped adult leaves, flower bud ...

'', '' E. tereticornis'', and '' E. camaldulensis'', which, on average, make up more than 20% of their diet. They will also consume other species in the genus such as '' E. ovata'', '' E. punctata'', and '' E. viminalis''. Despite its reputation as a fussy eater, the koala is more generalist

A generalist is a person with a wide array of knowledge on a variety of subjects, useful or not. It may also refer to:

Occupations

* a physician who provides general health care, as opposed to a medical specialist; see also:

** General pract ...

than some other marsupial species, such as the greater glider

The greater gliders are three species of large gliding marsupials in the genus ''Petauroides'', all of which are found in eastern Australia. Until 2020 they were considered to be one species, '' Petauroides volans''. In 2020 morphological and gen ...

. Since eucalypt leaves have a high water content, the koala does not need to drink often; its daily water turnover rate ranges from 71 to 91 ml/kg of body weight. Although females can meet their water requirements by eating leaves, larger males require additional water found on the ground or in tree hollows. When feeding, a koala holds onto a branch with hind paws and one forepaw while the other forepaw grasps foliage. Small koalas can move close to the end of a branch, but larger ones stay near the thicker bases. Koalas consume up to of leaves a day, spread over four to six feeding sessions. Despite their adaptations to a low-energy lifestyle, they have meagre fat reserves and need to feed often.

Because they get so little energy from their diet, koalas must limit their energy use

Energy consumption is the amount of energy used.

Biology

In the body, energy consumption is part of energy homeostasis. It derived from food energy. Energy consumption in the body is a product of the basal metabolic rate and the physical activity ...

and sleep or rest 20 hours a day. They are predominantly active at night and spend most of their waking hours feeding. They typically eat and sleep in the same tree, possibly for as long as a day. On very hot days, a koala may climb down to the coolest part of the tree which is cooler than the surrounding air. The koala hugs the tree to lose heat without panting. On warm days, a koala may rest with its back against a branch or lie on its stomach or back with its limbs dangling. During cold, wet periods, it curls itself into a tight ball to conserve energy. On windy days, a koala finds a lower, thicker branch on which to rest. While it spends most of the time in the tree, the animal descends to the ground to move to another tree. The koala usually grooms itself with its hind paws, but sometimes uses its forepaws or mouth.

Social spacing

Koalas are asocial animals and spend just 15 minutes a day on social behaviours. In Victoria,home range

A home range is the area in which an animal lives and moves on a periodic basis. It is related to the concept of an animal's territory which is the area that is actively defended. The concept of a home range was introduced by W. H. Burt in 1943. He ...

s are small and have extensive overlap, while in central Queensland they are larger and overlap less. Koala society appears to consist of "residents" and "transients", the former being mostly adult females and the latter males. Resident males appear to be territorial

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected┬Āto a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or a ...

and dominate

The Dominate, also known as the late Roman Empire, is the name sometimes given to the "despotic" later phase of imperial government in the ancient Roman Empire. It followed the earlier period known as the "Principate". Until the empire was reunit ...

others with their larger body size. Alpha males

In biology, a dominance hierarchy (formerly and colloquially called a pecking order) is a type of social hierarchy that arises when members of animal social groups interact, creating a ranking system. A dominant higher-ranking individual is so ...

tend to establish their territories close to breeding females, while younger males are subordinate until they mature and reach full size. Adult males occasionally venture outside their home ranges; when they do so, dominant ones retain their status. When a male enters a new tree, he marks it by rubbing his chest gland against the trunk or a branch; males have occasionally been observed to dribble urine on the trunk. This scent-marking behaviour probably serves as communication, and individuals are known to sniff the base of a tree before climbing. Scent marking is common during aggressive encounters. Chest gland secretions are complex chemical mixturesŌĆöabout 40 compounds were identified in one analysisŌĆöthat vary in composition and concentration with the season and the age of the individual.

Adult males communicate with loud bellowsŌĆölow pitched sounds that consist of snore-like inhalations and

Adult males communicate with loud bellowsŌĆölow pitched sounds that consist of snore-like inhalations and resonant

Resonance describes the phenomenon of increased amplitude that occurs when the frequency of an applied periodic force (or a Fourier component of it) is equal or close to a natural frequency of the system on which it acts. When an oscillatin ...

exhalations that sound like growls. These sounds are thought to be generated by unique vocal organs found in koalas. Because of their low frequency

Frequency is the number of occurrences of a repeating event per unit of time. It is also occasionally referred to as ''temporal frequency'' for clarity, and is distinct from ''angular frequency''. Frequency is measured in hertz (Hz) which is eq ...

, these bellows can travel far through air and vegetation. Koalas may bellow at any time of the year, particularly during the breeding season

Seasonal breeders are animal species that successfully mate only during certain times of the year. These times of year allow for the optimization of survival of young due to factors such as ambient temperature, food and water availability, and cha ...

, when it serves to attract females and possibly intimidate other males. They also bellow to advertise their presence to their neighbours when they enter a new tree. These sounds signal the male's actual body size, as well as exaggerate it; females pay more attention to bellows that originate from larger males. Female koalas bellow, though more softly, in addition to making snarls, wails, and screams. These calls are produced when in distress and when making defensive threats. Young koalas squeak when in distress. As they get older, the squeak develops into a "squawk" produced both when in distress and to show aggression. When another individual climbs over it, a koala makes a low grunt with its mouth closed. Koalas make numerous facial expressions. When snarling, wailing, or squawking, the animal curls the upper lip and points its ears forward. During screams, the lips retract and the ears are drawn back. Females bring their lips forward and raise their ears when agitated.

Agonistic behaviour

Agonistic behaviour is any social behaviour related to fighting. The term has broader meaning than aggressive behaviour because it includes threats, displays, retreats, placation, and conciliation. The term "agonistic behaviour" was first implemen ...

typically consists of squabbles between individuals climbing over or passing each other. This occasionally involves biting. Males that are strangers may wrestle, chase, and bite each other. In extreme situations, a male may try to displace a smaller rival from a tree. This involves the larger aggressor climbing up and attempting to corner the victim, which tries either to rush past him and climb down or to move to the end of a branch. The aggressor attacks by grasping the target by the shoulders and repeatedly biting him. Once the weaker individual is driven away, the victor bellows and marks the tree. Pregnant and lactating

Lactation describes the secretion of milk from the mammary glands and the period of time that a mother lactates to feed her young. The process naturally occurs with all sexually mature female mammals, although it may predate mammals. The proces ...

females are particularly aggressive and attack individuals that come too close. In general, however, koalas tend to avoid energy-wasting aggressive behaviour.

Reproduction and development

Koalas are seasonal breeders, and births take place from the middle of spring through the summer to early autumn, from October to May. Females in

Koalas are seasonal breeders, and births take place from the middle of spring through the summer to early autumn, from October to May. Females in oestrus

The estrous cycle (, originally ) is the set of recurring physiological changes that are induced by reproductive hormones in most mammalian therian females. Estrous cycles start after sexual maturity in females and are interrupted by anestrous ...

tend to hold their heads further back than usual and commonly display tremor

A tremor is an involuntary, somewhat rhythmic, muscle contraction and relaxation involving oscillations or twitching movements of one or more body parts. It is the most common of all involuntary movements and can affect the hands, arms, eyes, fa ...

s and spasm

A spasm is a sudden involuntary contraction of a muscle, a group of muscles, or a hollow organ such as the bladder.

A spasmodic muscle contraction may be caused by many medical conditions, including dystonia. Most commonly, it is a muscle c ...

s. However, males do not appear to recognise these signs and have been observed to mount non-oestrous females. Because of his much larger size, a male can usually force himself on a female, mounting her from behind, and in extreme cases, the male may pull the female out of the tree. A female may scream and vigorously fight off her suitors but will submit to one that is dominant or is more familiar. The bellows and screams that accompany matings can attract other males to the scene, obliging the incumbent to delay mating and fight off the intruders. These fights may allow the female to assess which is dominant. Older males usually have accumulated scratches, scars, and cuts on the exposed parts of their noses and their eyelids.

The koala's gestation

Gestation is the period of development during the carrying of an embryo, and later fetus, inside viviparous animals (the embryo develops within the parent). It is typical for mammals, but also occurs for some non-mammals. Mammals during pregna ...

period lasts 33ŌĆō35 days, and a female gives birth to a single joey

Joey may refer to:

People

*Joey (name)

Animals

* Joey (marsupial), an infant marsupial

* Joey, a Blue-fronted Amazon parrot who was one of the Blue Peter pets

Film and television

* ''Joey'' (1977 film), an American film directed by Horace ...

(although twins occur on occasion). As with all marsupials, the young are born while at the embryo

An embryo is an initial stage of development of a multicellular organism. In organisms that reproduce sexually, embryonic development is the part of the life cycle that begins just after fertilization of the female egg cell by the male spe ...

nic stage, weighing only . However, they have relatively well-developed lips, forelimbs, and shoulders, as well as functioning respiratory

The respiratory system (also respiratory apparatus, ventilatory system) is a biological system consisting of specific organs and structures used for gas exchange in animals and plants. The anatomy and physiology that make this happen varies grea ...

, digestive, and urinary system

The urinary system, also known as the urinary tract or renal system, consists of the kidneys, ureters, urinary bladder, bladder, and the urethra. The purpose of the urinary system is to eliminate waste from the body, regulate blood volume and bl ...

s. The joey crawls into its mother's pouch to continue the rest of its development. Unlike most other marsupials, the koala does not clean her pouch.

A female koala has two teats; the joey attaches itself to one of them and suckles for the rest of its pouch life. The koala has one of the lowest milk energy production rates, relative to body size, of any mammal. The female makes up for this by lactating

Lactation describes the secretion of milk from the mammary glands and the period of time that a mother lactates to feed her young. The process naturally occurs with all sexually mature female mammals, although it may predate mammals. The proces ...

for as long as 12 months. At seven weeks of age, the joey's head grows longer and becomes proportionally large, pigmentation

A pigment is a colored material that is completely or nearly insoluble in water. In contrast, dyes are typically soluble, at least at some stage in their use. Generally dyes are often organic compounds whereas pigments are often inorganic compo ...

begins to develop, and its sex can be determined (the scrotum

The scrotum or scrotal sac is an anatomical male reproductive structure located at the base of the penis that consists of a suspended dual-chambered sac of skin and smooth muscle. It is present in most terrestrial male mammals. The scrotum cont ...

appears in males and the pouch begins to develop in females). At 13 weeks, the joey weighs around and its head has doubled in size. The eyes begin to open and fine fur grows on the forehead, nape

The nape is the back of the neck. In technical anatomical/medical terminology, the nape is also called the nucha (from the Medieval Latin rendering of the Arabic , "spinal marrow"). The corresponding adjective is ''nuchal'', as in the term ''nu ...

, shoulders, and arms. At 26 weeks, the fully furred animal resembles an adult and begins to poke its head out of the pouch.

As the young koala approaches six months, the mother begins to prepare it for its eucalyptus diet by predigesting the leaves, producing a faecal pap that the joey eats from her

As the young koala approaches six months, the mother begins to prepare it for its eucalyptus diet by predigesting the leaves, producing a faecal pap that the joey eats from her cloaca

In animal anatomy, a cloaca ( ), plural cloacae ( or ), is the posterior orifice that serves as the only opening for the digestive, reproductive, and urinary tracts (if present) of many vertebrate animals. All amphibians, reptiles and birds, a ...

. The pap is quite different in composition from regular faeces, resembling instead the contents of the caecum, which has a high concentration of bacteria. Eaten for about a month, the pap provides a supplementary source of protein at a transition time from a milk to a leaf diet. The joey fully emerges from the pouch for the first time at six or seven months of age, when it weighs . It explores its new surroundings cautiously, clinging to its mother for support. By nine months, it weighs over and develops its adult fur colour. Having permanently left the pouch, it rides on its mother's back for transportation, learning to climb by grasping branches. Gradually, it spends more time away from its mother, who becomes pregnant again after 12 months when the young is now around . Her bond with her previous offspring is permanently severed and she no longer allows it to suckle, but it will continue to live near her for the next 6ŌĆō12 months.

Females become sexually mature

Sexual maturity is the capability of an organism to reproduce. In humans it might be considered synonymous with adulthood, but here puberty is the name for the process of biological sexual maturation, while adulthood is based on cultural definitio ...

at about three years of age and can then become pregnant; in comparison, males reach sexual maturity when they are about four years old, although they can produce sperm as early as two years. While the chest glands can be functional as early as 18 months of age, males do not begin scent-marking behaviours until they reach sexual maturity. Because the offspring have a long dependent period, female koalas usually breed in alternate years. Favourable environmental factors, such as a plentiful supply of high-quality food trees, allow them to reproduce every year.

Health and mortality

Koalas may live from 13 to 18 years in the wild. While female koalas usually live this long, males may die sooner because of their more hazardous lives. Koalas usually survive falls from trees and immediately climb back up, but injuries and deaths from falls do occur, particularly in inexperienced young and fighting males. Around six years of age, the koala's chewing teeth begin to wear down and their chewing efficiency decreases. Eventually, the cusps disappear completely and the animal will die of starvation. Koalas have few predators;dingo

The dingo (''Canis familiaris'', ''Canis familiaris dingo'', ''Canis dingo'', or ''Canis lupus dingo'') is an ancient (Basal (phylogenetics), basal) lineage of dog found in Australia (continent), Australia. Its taxonomic classification is de ...

s and large pythons

The Pythonidae, commonly known as pythons, are a family of nonvenomous snakes found in Africa, Asia, and Australia. Among its members are some of the largest snakes in the world. Ten genera and 42 species are currently recognized.

Distribution ...

may prey on them; birds of prey

Birds of prey or predatory birds, also known as raptors, are hypercarnivorous bird species that actively hunt and feed on other vertebrates (mainly mammals, reptiles and other smaller birds). In addition to speed and strength, these predators ...

(such as powerful owl

The powerful owl (''Ninox strenua''), a species of owl native to south-eastern and eastern Australia, is the largest owl on the continent. It is found in coastal areas and in the Great Dividing Range, rarely more than inland. The IUCNRed List ...

s and wedge-tailed eagle

The wedge-tailed eagle (''Aquila audax'') is the largest bird of prey in the continent of Australia. It is also found in southern New Guinea to the north and is distributed as far south as the state of Tasmania. Adults of this species have lon ...

s) are threats to young. Koalas are generally not subject to external parasite

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has ...

s, other than tick

Ticks (order Ixodida) are parasitic arachnids that are part of the mite superorder Parasitiformes. Adult ticks are approximately 3 to 5 mm in length depending on age, sex, species, and "fullness". Ticks are external parasites, living by ...

s in coastal areas. Koalas may also suffer mange

Mange is a type of skin disease caused by parasitic mites. Because various species of mites also infect plants, birds and reptiles, the term "mange", or colloquially "the mange", suggesting poor condition of the skin and fur due to the infection ...

from the mite

Mites are small arachnids (eight-legged arthropods). Mites span two large orders of arachnids, the Acariformes and the Parasitiformes, which were historically grouped together in the subclass Acari, but genetic analysis does not show clear evid ...

''Sarcoptes scabiei

''Sarcoptes scabiei'' or the itch mite is a parasitic mite that burrows into skin and causes scabies. The mite is found in all parts of the world. Humans are not the only mammals that can become infected. Other mammals, such as wild and domesti ...

'', and skin ulcers

An ulcer is a sore on the skin or a mucous membrane, accompanied by the disintegration of tissue. Ulcers can result in complete loss of the epidermis and often portions of the dermis and even subcutaneous fat. Ulcers are most common on the skin of ...

from the bacterium ''Mycobacterium ulcerans

''Mycobacterium ulcerans'' is a species of bacteria found in various aquatic environments. The bacteria can infect humans and some other animals, causing persistent open wounds called Buruli ulcer. ''M. ulcerans'' is closely related to ''Mycoba ...

'', but neither is common. Internal parasites are few and largely harmless. These include the tapeworm

Eucestoda, commonly referred to as tapeworms, is the larger of the two subclasses of flatworms in the class Cestoda (the other subclass is Cestodaria). Larvae have six posterior hooks on the scolex (head), in contrast to the ten-hooked Cestodar ...

'' Bertiella obesa'', commonly found in the intestine, and the nematode

The nematodes ( or grc-gre, ╬Ø╬Ę╬╝╬▒ŽäŽÄ╬┤╬Ę; la, Nematoda) or roundworms constitute the phylum Nematoda (also called Nemathelminthes), with plant-Parasitism, parasitic nematodes also known as eelworms. They are a diverse animal phylum inhab ...

s ''Marsupostrongylus longilarvatus

''Marsupostrongylus longilarvatus'' is a metastrongyl (lung-worm) found in various marsupials. It was described as new to science by D.M. Spratt in 1979 from a swamp wallaby in New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales ...

'' and '' Durikainema phascolarcti'', which are infrequently found in the lungs. In a three-year study of almost 600 koalas admitted to the Australia Zoo Wildlife Hospital in Queensland, 73.8% of the animals were infected with at least one species of the parasitic protozoa

Protozoa (singular: protozoan or protozoon; alternative plural: protozoans) are a group of single-celled eukaryotes, either free-living or parasitic, that feed on organic matter such as other microorganisms or organic tissues and debris. Histo ...

l genus ''Trypanosoma

''Trypanosoma'' is a genus of kinetoplastids (class Trypanosomatidae), a monophyletic group of unicellular parasitic flagellate protozoa. Trypanosoma is part of the phylum Sarcomastigophora. The name is derived from the Greek ''trypano-'' (bore ...

'', the most common of which was '' T. irwini''.

Koalas can be subject to pathogen

In biology, a pathogen ( el, ŽĆ╬¼╬Ė╬┐Žé, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a germ ...

s such as Chlamydiaceae

The Chlamydiaceae are a family of gram-negative bacteria that belongs to the phylum Chlamydiota, order Chlamydiales. Chlamydiaceae species express the family-specific lipopolysaccharide epitope ╬▒Kdo-(2ŌåÆ8)-╬▒Kdo-(2ŌåÆ4)-╬▒Kdo (previously call ...

bacteria, which can cause keratoconjunctivitis

Keratoconjunctivitis is inflammation ("-itis") of the cornea and conjunctiva.

When only the cornea is inflamed, it is called ''keratitis''; when only the conjunctiva is inflamed, it is called ''conjunctivitis''.

Causes

There are several potentia ...

, urinary tract infection