Kiritimati Island on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Kiritimati (also known as Christmas Island) is a

Kiritimati was initially inhabited by Polynesian people.

Kiritimati was initially inhabited by Polynesian people.  Permanent settlement started in 1882, mainly by workers in coconut plantations and fishermen. In 1902, the British Government granted a 99 year lease on the island to Levers Pacific Plantations. The company planted 72,863 coconut palms on the island and introduced silver-lipped pearl oysters into the lagoon. The settlement didn't endure: Extreme drought killed 75% of the coconut palms, and the island was abandoned from 1905–1912.

Many of the

Permanent settlement started in 1882, mainly by workers in coconut plantations and fishermen. In 1902, the British Government granted a 99 year lease on the island to Levers Pacific Plantations. The company planted 72,863 coconut palms on the island and introduced silver-lipped pearl oysters into the lagoon. The settlement didn't endure: Extreme drought killed 75% of the coconut palms, and the island was abandoned from 1905–1912.

Many of the

Grapple Y test.jpg, The British ''Grapple Y'' test on 28 April 1958

Kiritimati bomb anchor.jpg, The bombs for the British ''Grapple Z1'' and ''Z4'' tests were hoisted by balloon; this is the East Point balloon anchor.

Project 26 - Operation Dominic (Johnston Island; Christmas Island; Maui, Hawaii) Detonation.jpg, A US test in the ''

Air Pacific ran flights to Kiritimati until 2008, when they stopped over concerns about the condition of the runway. Services resumed in 2010. A monthly air freight service is flown using a chartered from

Air Pacific ran flights to Kiritimati until 2008, when they stopped over concerns about the condition of the runway. Services resumed in 2010. A monthly air freight service is flown using a chartered from

Kiritimati's roughly lagoon opens to the sea in the northwest; ''Burgle Channel'' (the entrance to the lagoon) is divided into the northern ''Cook Island Passage'' and the southern ''South Passage''. The southeastern part of the lagoon is partially dried out today; essentially, progressing SE from Burgle Channel, the main lagoon gradually turns into a network of subsidiary lagoons,

Kiritimati's roughly lagoon opens to the sea in the northwest; ''Burgle Channel'' (the entrance to the lagoon) is divided into the northern ''Cook Island Passage'' and the southern ''South Passage''. The southeastern part of the lagoon is partially dried out today; essentially, progressing SE from Burgle Channel, the main lagoon gradually turns into a network of subsidiary lagoons,

Beach naupaka (''

Beach naupaka (''

:''See also "Extinction" below.''

More than 35 bird

:''See also "Extinction" below.''

More than 35 bird

There are some "supertramp"

There are some "supertramp"

In December 1960, the British colonial authority gazetted Kiritimati as a

In December 1960, the British colonial authority gazetted Kiritimati as a

Given that the island was apparently settled to some extent in prehistoric times, it may have already lost bird species then. The geological data indicates that Kiritimati is very old and was never completely underwater in the Holocene at least; thus it might have once harboured highly distinct wetland birds.

The limited overall habitat diversity on Kiritimati nonetheless limits the range of such hypothetical

Given that the island was apparently settled to some extent in prehistoric times, it may have already lost bird species then. The geological data indicates that Kiritimati is very old and was never completely underwater in the Holocene at least; thus it might have once harboured highly distinct wetland birds.

The limited overall habitat diversity on Kiritimati nonetheless limits the range of such hypothetical

VSA Assignment Description Assignment title English Language Trainer (of Trainers/ Teachers) Country Kiribati

." Volunteer Service Abroad (Te Tūao Tāwāhi). Retrieved on 6 July 2018. p. 7. in addition to a Catholic senior high, St. Francis High School.

Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

atoll

An atoll () is a ring-shaped island, including a coral rim that encircles a lagoon partially or completely. There may be coral islands or cays on the rim. Atolls are located in warm tropical or subtropical oceans and seas where corals can gr ...

in the northern Line Islands

The Line Islands, Teraina Islands or Equatorial Islands (in Gilbertese, ''Aono Raina'') are a chain of 11 atolls (with partly or fully enclosed lagoons) and coral islands (with a surrounding reef) in the central Pacific Ocean, south of the Hawa ...

. It is part of the Republic of Kiribati

Kiribati (), officially the Republic of Kiribati ( gil, ibaberikiKiribati),Kiribati

''The Wor ...

. The name is derived from the English word "Christmas" written in ''The Wor ...

Gilbertese

Gilbertese or taetae ni Kiribati, also Kiribati (sometimes ''Kiribatese''), is an Austronesian language spoken mainly in Kiribati. It belongs to the Micronesian branch of the Oceanic languages.

The word ''Kiribati'', the current name of the i ...

according to its phonology

Phonology is the branch of linguistics that studies how languages or dialects systematically organize their sounds or, for sign languages, their constituent parts of signs. The term can also refer specifically to the sound or sign system of a ...

, in which the combination ''ti'' is pronounced ''s'', giving kiˈrɪsmæs.

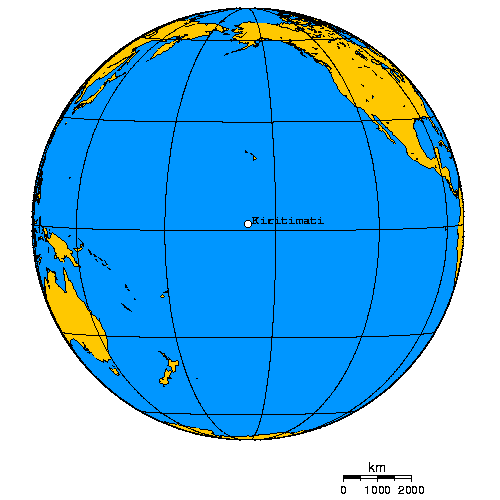

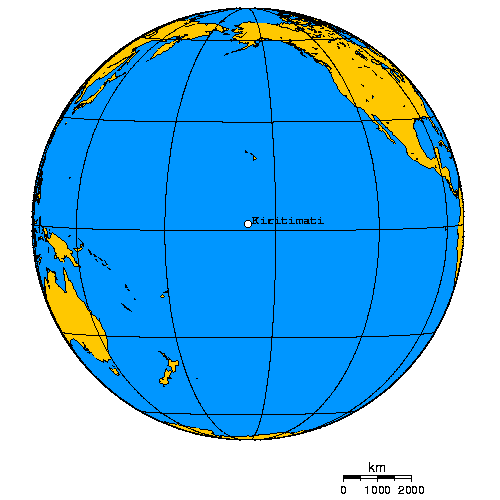

Kiritimati has the greatest land area of any atoll in the world, about ; its lagoon

A lagoon is a shallow body of water separated from a larger body of water by a narrow landform, such as reefs, barrier islands, barrier peninsulas, or isthmuses. Lagoons are commonly divided into ''coastal lagoons'' (or ''barrier lagoons'') a ...

is roughly the same size. The atoll is about in perimeter, while the lagoon shoreline extends for over . Kiritimati comprises over 70% of the total land area of Kiribati, a country encompassing 33 Pacific atolls and islands.

It lies north of the equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

, south of Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

, and from San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

. Kiritimati is in the world's farthest forward time zone, UTC+14

UTC+14:00 is an identifier for a time offset from UTC of +14:00. This is the earliest time zone on Earth, meaning that areas in this zone are the first to see a new day, and therefore the first to celebrate a New Year. It is also referred to as t ...

, and is therefore one of the first inhabited places on Earth to experience New Year's Day. (see also Caroline Atoll

Caroline Island (also known as Caroline Atoll or Millennium Island) is the easternmost of several uninhabited coral atolls comprising the southern Line Islands in the central Pacific Ocean nation of Kiribati.

The atoll was first sighted by Eu ...

, Kiribati). Although it lies east of the 180th meridian, the Republic of Kiribati realigned the International Date Line

The International Date Line (IDL) is an internationally accepted demarcation on the surface of Earth, running between the South and North Poles and serving as the boundary between one calendar day and the next. It passes through the Pacific O ...

in 1995, placing Kiritimati to the west of the dateline.

Nuclear test

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, Nuclear weapon yield, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detona ...

s were conducted on and around Kiritimati by the United Kingdom in the late 1950s, and by the United States in 1962. During these tests, the island was not evacuated, exposing the i-Kiribati residents and the British, New Zealand, and Fijian servicemen to nuclear radiation.

The entire island is a Wildlife Sanctuary

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or o ...

; access to five particularly sensitive areas is restricted.

History

Kiritimati was initially inhabited by Polynesian people.

Kiritimati was initially inhabited by Polynesian people. Radiometric dating

Radiometric dating, radioactive dating or radioisotope dating is a technique which is used to date materials such as rocks or carbon, in which trace radioactive impurities were selectively incorporated when they were formed. The method compares t ...

from sites on the island place the period of human use between 1250 and 1450 CE. Permanent human settlement on Kiritimati likely never occurred. Stratigraphic

Stratigraphy is a branch of geology concerned with the study of rock layers (strata) and layering (stratification). It is primarily used in the study of sedimentary and layered volcanic rocks.

Stratigraphy has three related subfields: lithostra ...

layers excavated in fire pits show alternating bands of charcoal indicating heavy use and local soil indicating a lack of use. As such, some researchers have suggested that Kiritimati was used intermittently (likely by people from Tabuaeran

Tabuaeran, also known as Fanning Island, is an atoll that is part of the Line Islands of the central Pacific Ocean and part of Kiribati. The land area is , and the population in 2015 was 2,315. The maximum elevation is about 3 m (10 f ...

to the north) as a place to gather resources such as birds and turtles in a similar fashion to the ethnographically

Ethnography (from Greek ''ethnos'' "folk, people, nation" and ''grapho'' "I write") is a branch of anthropology and the systematic study of individual cultures. Ethnography explores cultural phenomena from the point of view of the subject o ...

documented use of the five central atolls of the Caroline Islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

.

Archaeological sites on the island are concentrated along the east (windward) side of the island and known sites represent a series of habitation sites, marae

A ' (in New Zealand Māori, Cook Islands Māori, Tahitian), ' (in Tongan), ' (in Marquesan) or ' (in Samoan) is a communal or sacred place that serves religious and social purposes in Polynesian societies. In all these languages, the term a ...

, and supporting structures such as canoe storage sheds and navigational aids.

The atoll was then discovered by Europeans with the Spanish expedition of in 1537, that charted it as ''Acea''. This discovery was referred by a contemporary, the Portuguese António Galvão

António Galvão (c. 1490–1557), also known as Antonio Galvano, was a Portuguese soldier, chronicler and administrator in the Maluku islands, and a Renaissance historian who was the first person to present a comprehensive report of the leading v ...

, governor of Ternate

Ternate is a city in the Indonesian province of North Maluku and an island in the Maluku Islands. It was the ''de facto'' provincial capital of North Maluku before Sofifi on the nearby coast of Halmahera became the capital in 2010. It is off the we ...

, in his book ''Tratado dos Descubrimientos'' of 1563. During his third voyage, Captain James Cook

James Cook (7 November 1728 Old Style date: 27 October – 14 February 1779) was a British explorer, navigator, cartographer, and captain in the British Royal Navy, famous for his three voyages between 1768 and 1779 in the Pacific Ocean and ...

visited the island on Christmas Eve (24 December) 1777 and the island was put on a map in 1781 as ''île des Tortues'' (Turtles Island) by in Augsburg

Augsburg (; bar , Augschburg , links=https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Swabian_German , label=Swabian German, , ) is a city in Swabia, Bavaria, Germany, around west of Bavarian capital Munich. It is a university town and regional seat of the ' ...

. Whaling

Whaling is the process of hunting of whales for their usable products such as meat and blubber, which can be turned into a type of oil that became increasingly important in the Industrial Revolution.

It was practiced as an organized industry ...

vessels visited the island from at least 1822. and it was claimed by the United States under the Guano Islands Act

The Guano Islands Act (, enacted August 18, 1856, codified at §§ 1411-1419) is a United States federal law passed by the U.S. Congress that enables citizens of the United States to take possession, in the name of the United States, of unclai ...

of 1856, though little actual mining of guano

Guano (Spanish from qu, wanu) is the accumulated excrement of seabirds or bats. As a manure, guano is a highly effective fertilizer due to the high content of nitrogen, phosphate, and potassium, all key nutrients essential for plant growth. G ...

took place.

Permanent settlement started in 1882, mainly by workers in coconut plantations and fishermen. In 1902, the British Government granted a 99 year lease on the island to Levers Pacific Plantations. The company planted 72,863 coconut palms on the island and introduced silver-lipped pearl oysters into the lagoon. The settlement didn't endure: Extreme drought killed 75% of the coconut palms, and the island was abandoned from 1905–1912.

Many of the

Permanent settlement started in 1882, mainly by workers in coconut plantations and fishermen. In 1902, the British Government granted a 99 year lease on the island to Levers Pacific Plantations. The company planted 72,863 coconut palms on the island and introduced silver-lipped pearl oysters into the lagoon. The settlement didn't endure: Extreme drought killed 75% of the coconut palms, and the island was abandoned from 1905–1912.

Many of the toponym

Toponymy, toponymics, or toponomastics is the study of '' toponyms'' (proper names of places, also known as place names and geographic names), including their origins, meanings, usage and types. Toponym is the general term for a proper name of ...

s in the island date to Father , a French priest who leased the island from 1917–1939, and planted some 500,000 coconut

The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family ( Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, the seed, or the ...

trees there. He lived in his ''Paris'' house (now only small ruins) located at ''Benson Point'', across the Burgle Channel from ''Londres'' at ''Bridges Point'' (today London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

) where he established the port. He gave the name of ''Poland'' to a village where Stanisław (Stanislaus) Pełczyński, his Polish plantation manager then lived.

Joe English, of Medford, Massachusetts, Rougier's plantation manager from 1915–1919, named ''Joe's Hill'' (some 12 metres / 40 feet high) after himself. English and two teenagers were marooned on the island for a year and a half (1917–1919) as transport had stopped due to the Spanish flu

The 1918–1920 influenza pandemic, commonly known by the misnomer Spanish flu or as the Great Influenza epidemic, was an exceptionally deadly global influenza pandemic caused by the H1N1 influenza A virus. The earliest documented case was ...

breaking out in Tahiti

Tahiti (; Tahitian ; ; previously also known as Otaheite) is the largest island of the Windward group of the Society Islands in French Polynesia. It is located in the central part of the Pacific Ocean and the nearest major landmass is Austr ...

and around the world. English was later rescued by British admiral

Admiral is one of the highest ranks in some navies. In the Commonwealth nations and the United States, a "full" admiral is equivalent to a "full" general in the army or the air force, and is above vice admiral and below admiral of the fleet, ...

John Jellicoe

Admiral of the Fleet John Rushworth Jellicoe, 1st Earl Jellicoe, (5 December 1859 – 20 November 1935) was a Royal Navy officer. He fought in the Anglo-Egyptian War and the Boxer Rebellion and commanded the Grand Fleet at the Battle of Jutlan ...

. English, thinking that the rescue ship was German and the war was still in effect, pulled his revolver

A revolver (also called a wheel gun) is a repeating handgun that has at least one barrel and uses a revolving cylinder containing multiple chambers (each holding a single cartridge) for firing. Because most revolver models hold up to six roun ...

on the admiral Jellicoe, causing a short standoff until some explanation defused the situation.

Kiritimati was occupied by the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

with the U.S. in control of the island garrison. The atoll was important to hold, since Japanese occupation would allow interdiction of the Hawaii-to-Australia supply route. For the first few months there were next to no recreational facilities on the island, and the men amused themselves by shooting sharks in the lagoon. The island's first airstrip was constructed at this time to supply the Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

weather station and communications center. The airstrip also provided rest and refuelling facilities for planes travelling between Hawaii and the South Pacific. The 1947 census listed only 47 inhabitants on the island. The U.S. Guano Islands Act claim was formally ceded by the Treaty of Tarawa

On September 20, 1979, representatives of the newly independent Republic of Kiribati and of the United States met in Tarawa to sign a treaty of friendship between the two nations, known as the Treaty of Tarawa. More formally, the treaty is entit ...

between the U.S. and Kiribati. The treaty was signed in 1979 and ratified in 1983.

Spain's sovereignty rights

During the dispute over theCaroline islands

The Caroline Islands (or the Carolines) are a widely scattered archipelago of tiny islands in the western Pacific Ocean, to the north of New Guinea. Politically, they are divided between the Federated States of Micronesia (FSM) in the centra ...

between Germany and Spain in 1885 which was arbitrated by Pope Leo XIII

Pope Leo XIII ( it, Leone XIII; born Vincenzo Gioacchino Raffaele Luigi Pecci; 2 March 1810 – 20 July 1903) was the head of the Catholic Church from 20 February 1878 to his death in July 1903. Living until the age of 93, he was the second-old ...

, the sovereignty

Sovereignty is the defining authority within individual consciousness, social construct, or territory. Sovereignty entails hierarchy within the state, as well as external autonomy for states. In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the perso ...

of Spain over the Caroline and Palau

Palau,, officially the Republic of Palau and historically ''Belau'', ''Palaos'' or ''Pelew'', is an island country and microstate in the western Pacific. The nation has approximately 340 islands and connects the western chain of the Caro ...

islands as part of the Spanish East Indies

The Spanish East Indies ( es , Indias orientales españolas ; fil, Silangang Indiyas ng Espanya) were the overseas territories of the Spanish Empire in Asia-Pacific, Asia and Oceania from 1565 to 1898, governed for the Spanish Crown from Mexico C ...

was analysed by a commission of cardinals

Cardinal or The Cardinal may refer to:

Animals

* Cardinal (bird) or Cardinalidae, a family of North and South American birds

**''Cardinalis'', genus of cardinal in the family Cardinalidae

**''Cardinalis cardinalis'', or northern cardinal, the ...

and confirmed by an agreement signed on 17 December 1885. Its Article 2 specifies the limits of Spanish sovereignty in South Micronesia, being formed by the Equator and 11°N Latitude and by 133° and 164° Longitude. In 1899, Spain sold the Marianas, Carolines, and Palau to Germany after its defeat in 1898 in the Spanish–American War

, partof = the Philippine Revolution, the decolonization of the Americas, and the Cuban War of Independence

, image = Collage infobox for Spanish-American War.jpg

, image_size = 300px

, caption = (clock ...

. However Emilio Pastor Santos, a researcher of the Spanish National Research Council

The Spanish National Research Council ( es, Consejo Superior de Investigaciones Científicas, CSIC) is the largest public institution dedicated to research in Spain and the third largest in Europe. Its main objective is to develop and promote res ...

, claimed in 1948 that there was historical basis to argue that Kiritimati ("Acea" on the Spanish maps) and some other islands had never been considered part of the Carolines, supported by the charts and maps of the time. Despite having sought acknowledgement of the issue regarding interpretation of the treaty, no Spanish government has made any attempt to assert sovereignty over Kiritimati, and the case remains a historical curiosity.

Nuclear bomb tests

During theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

Kiritimati was used for nuclear weapons testing

Nuclear weapons tests are experiments carried out to determine nuclear weapons' effectiveness, Nuclear weapon yield, yield, and explosive capability. Testing nuclear weapons offers practical information about how the weapons function, how detona ...

by the United Kingdom and the USA. The United Kingdom conducted its first hydrogen bomb

A thermonuclear weapon, fusion weapon or hydrogen bomb (H bomb) is a second-generation nuclear weapon design. Its greater sophistication affords it vastly greater destructive power than first-generation nuclear bombs, a more compact size, a lowe ...

test series, Grapple 1-3, at Malden Island

Malden Island, sometimes called Independence Island in the 19th century, is a low, arid, uninhabited atoll in the central Pacific Ocean, about in area. It is one of the Line Islands belonging to the Republic of Kiribati. The lagoon is enti ...

from 15 May to 19 June 1957 and used Kiritimati as the operation's main base. On 8 November 1957, the first H-bomb was detonated over the southeastern tip of Kiritimati in the Grapple X test. Subsequent tests in 1958 ( Grapple Y and Z) also took place above or near Kiritimati.

The United Kingdom detonated some of nuclear payload near and directly above Kiritimati in 1957–1958, while the total yield of weapons tested by the United States in the vicinity of the island between 25 April and 11 July 1962 was . During the British Grapple X test, yield was stronger than expected, resulting in the blast demolishing buildings and infrastructure. Islanders were usually not evacuated during the nuclear weapons testing, and data on the environmental and public health impact of these tests remains contested.

The United States also conducted 22 successful nuclear detonations over the island as part of Operation Dominic

Operation Dominic was a series of 31 nuclear test explosions with a total yield conducted in 1962 by the United States in the Pacific. This test series was scheduled quickly, in order to respond in kind to the Soviet resumption of testing af ...

in 1962. Some toponyms (like ''Banana'' and ''Main Camp'') come from the nuclear testing period, during which at times over 4,000 servicemen were present. By 1969, military interest in Kiritimati had ended and the facilities were mostly dismantled. However, some communications, transport, and logistics facilities were converted for civilian use, which Kiritimati uses to serve as the administrative centre for the Line Islands.

Operation Dominic

Operation Dominic was a series of 31 nuclear test explosions with a total yield conducted in 1962 by the United States in the Pacific. This test series was scheduled quickly, in order to respond in kind to the Soviet resumption of testing af ...

'' series, 1962

Memorial tablet in Paisley.jpg, Memorial tablet in Paisley remembering the people involved in the tests

Present status

The island's population has strongly increased in recent years, from about 2,000 in 1989 to about 5,000 in the early 2000s. Kiritimati has three representatives in theManeaba ni Maungatabu

The House of Assembly (, ) is the Legislature of Kiribati. Since 2016, it has 45 members, 44 elected for a four-year term in 23 single-seat and multi-seat constituencies and 1 non-elected delegate from the Banaban community on Rabi Island in Fi ...

. Today there are five villages on the island, four populated and one abandoned:

::

The main villages of Kiritimati are Banana, Tabwakea, and London, which are located along the main road on the northern tip of the island, and Poland, which is across the main lagoon to the South. London is the main village and port facility. Banana is near Cassidy International Airport but may be relocated closer to London to prevent groundwater contamination. The abandoned village of Paris is no longer listed in census reports.

The ministry of the Line and Phoenix islands is located in London. There are also two new high schools on the road between Tabwakea and Banana: One Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and one Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

. The University of Hawaii

A university () is an institution of higher (or tertiary) education and research which awards academic degrees in several academic disciplines. Universities typically offer both undergraduate and postgraduate programs. In the United States, th ...

has a climatological

Climatology (from Greek , ''klima'', "place, zone"; and , '' -logia'') or climate science is the scientific study of Earth's climate, typically defined as weather conditions averaged over a period of at least 30 years. This modern field of stud ...

research facility on Kiritimati. A Catholic church dedicated under the auspices of Saint Stanislaus and a primary school is located in Poland. The Kiribati Institute of Technology (KIT), based on Tarawa, opened a campus on Kiritimati in June 2019.

Commerce

Most of the atoll's food supplies have to be imported. Potable water can be in short supply, especially around November inLa Niña

La Niña (; ) is an oceanic and atmospheric phenomenon that is the colder counterpart of as part of the broader El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) climate pattern. The name ''La Niña'' originates from Spanish for "the girl", by an ...

years. A large and modern jetty

A jetty is a structure that projects from land out into water. A jetty may serve as a breakwater, as a walkway, or both; or, in pairs, as a means of constricting a channel. The term derives from the French word ', "thrown", signifying somet ...

, handling some cargo, was built by the Japanese at London. Marine fish provide a large portion of the island's nutrition, although overfishing

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish (i.e. fishing) from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally (i.e. the overexploitation of the fishery's existing fish stock), resulting in th ...

has caused a drastic decrease in the populations of large, predatory fish over the last several years.

Exports of the atoll are mainly copra

Copra (from ) is the dried, white flesh of the coconut from which coconut oil is extracted. Traditionally, the coconuts are sun-dried, especially for export, before the oil, also known as copra oil, is pressed out. The oil extracted from copr ...

(dried coconut pulp); the state-owned coconut plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

covers about . In addition aquarium

An aquarium (plural: ''aquariums'' or ''aquaria'') is a vivarium of any size having at least one transparent side in which aquatic plants or animals are kept and displayed. Fishkeepers use aquaria to keep fish, invertebrates, amphibians, aq ...

fish and seaweed

Seaweed, or macroalgae, refers to thousands of species of macroscopic, multicellular, marine algae. The term includes some types of '' Rhodophyta'' (red), ''Phaeophyta'' (brown) and ''Chlorophyta'' (green) macroalgae. Seaweed species such as ...

are exported. A 1970s project to commercially breed ''Artemia salina

''Artemia salina'' is a species of brine shrimp – aquatic crustaceans that are more closely related to '' Triops'' and cladocerans than to true shrimp. It belongs to a lineage that does not appear to have changed much in .

''A. salina'' is na ...

'' brine shrimp in the salt ponds was abandoned in 1978. In recent years there have been attempts to explore the viability of live crayfish

Crayfish are freshwater crustaceans belonging to the clade Astacidea, which also contains lobsters. In some locations, they are also known as crawfish, craydids, crawdaddies, crawdads, freshwater lobsters, mountain lobsters, rock lobsters, mu ...

and chilled fish exports and salt production.

Transport

Cassidy International Airport is located just north ofBanana

A banana is an elongated, edible fruit – botanically a berry – produced by several kinds of large herbaceous flowering plants in the genus ''Musa''. In some countries, bananas used for cooking may be called "plantains", distinguis ...

and North East Point. It has a paved runway with a length of and was for some time the only airport in Kiribati to serve the Americas, via an Air Pacific (now Fiji Airways) flight to Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

, Hawaii. American Te Mauri Travel offers weekly charter flights from Honolulu.

Air Pacific ran flights to Kiritimati until 2008, when they stopped over concerns about the condition of the runway. Services resumed in 2010. A monthly air freight service is flown using a chartered from

Air Pacific ran flights to Kiritimati until 2008, when they stopped over concerns about the condition of the runway. Services resumed in 2010. A monthly air freight service is flown using a chartered from Honolulu

Honolulu (; ) is the capital and largest city of the U.S. state of Hawaii, which is in the Pacific Ocean. It is an unincorporated county seat of the consolidated City and County of Honolulu, situated along the southeast coast of the island ...

operated by Asia Pacific Airlines.

Aeon Field

The word aeon , also spelled eon (in American and Australian English), originally meant "life", "vital force" or "being", "generation" or "a period of time", though it tended to be translated as "age" in the sense of "ages", "forever", "timel ...

is an abandoned airport, constructed before the British nuclear tests. It is located on the southeastern peninsula.

Tourism

There is a small amount of tourism, mainly associated with anglers interested in lagoon fishing (forbonefish

The bonefish (''Albula vulpes'') is the type species of the bonefish family (Albulidae), the only family in order Albuliformes.

History

Bonefish were once believed to be a single species with a global distribution, however 9 different species ...

in particular) or offshore fishing. Week-long ecotourism

Ecotourism is a form of tourism involving responsible travel (using sustainable transport) to natural areas, conserving the environment, and improving the well-being of the local people. Its purpose may be to educate the traveler, to provide funds ...

packages during which some of the normally closed areas can be visited are also available.

In recent years, surfers have discovered that there are good waves during the Northern Hemisphere's winter season and there are interests developing to service these recreational tourists. There is some tourism-related infrastructure, such as a small hotel, rental facilities, and food services.

Prospective launch sites

In the early 1950s,Wernher von Braun

Wernher Magnus Maximilian Freiherr von Braun ( , ; 23 March 191216 June 1977) was a German and American aerospace engineer and space architect. He was a member of the Nazi Party and Allgemeine SS, as well as the leading figure in the develop ...

proposed using this island as a launch site for manned spacecraft, based on its proximity to the equator, and the generally empty ocean down-range (east).

There is a Japanese JAXA

The is the Japanese national air and space agency. Through the merger of three previously independent organizations, JAXA was formed on 1 October 2003. JAXA is responsible for research, technology development and launch of satellites into orb ...

satellite tracking station. The abandoned Aeon Field had at one time been proposed for reuse by the Japanese for their now-canceled HOPE-X

HOPE (H-II Orbiting Plane) was a Japanese experimental spaceplane project designed by a partnership between NASDA and NAL (both now part of JAXA), started in the 1980s. It was positioned for most of its lifetime as one of the main Japanese contri ...

space shuttle project.

Kiritimati is also located fairly close to the Sea Launch

Sea Launch was a multinational—Norway, Russia, Ukraine, United States—spacecraft launch company founded in 1995 that provided orbital launch services from 1999–2014. The company used a mobile maritime launch platform for equatorial lau ...

satellite launching spot at 0° N 154° W, about 370 kilometres (200 nmi) to the east in international waters.

Geography

Kiritimati's roughly lagoon opens to the sea in the northwest; ''Burgle Channel'' (the entrance to the lagoon) is divided into the northern ''Cook Island Passage'' and the southern ''South Passage''. The southeastern part of the lagoon is partially dried out today; essentially, progressing SE from Burgle Channel, the main lagoon gradually turns into a network of subsidiary lagoons,

Kiritimati's roughly lagoon opens to the sea in the northwest; ''Burgle Channel'' (the entrance to the lagoon) is divided into the northern ''Cook Island Passage'' and the southern ''South Passage''. The southeastern part of the lagoon is partially dried out today; essentially, progressing SE from Burgle Channel, the main lagoon gradually turns into a network of subsidiary lagoons, tidal flat

Mudflats or mud flats, also known as tidal flats or, in Ireland, slob or slobs, are coastal wetlands that form in intertidal areas where sediments have been deposited by tides or rivers. A global analysis published in 2019 suggested that tidal fl ...

s, partially hypersaline

A hypersaline lake is a landlocked body of water that contains significant concentrations of sodium chloride, brines, and other salts, with saline levels surpassing that of ocean water (3.5%, i.e. ).

Specific microbial species can thrive in hi ...

brine

Brine is a high-concentration solution of salt (NaCl) in water (H2O). In diverse contexts, ''brine'' may refer to the salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawater, on the lower end of that of solutions used for br ...

ponds and salt pans, which as a whole has about the same area again as the main lagoon. Thus, the land and lagoon areas can only be given approximately, as no firm boundary exists between the main island body and the salt flats. Vaskess Bay is a large bay which extends along the southwest coast of Kiritimati Island.

In addition to the main island, there are several smaller ones. ''Cook Island'' is part of the atoll proper but unconnected to the Kiritimati mainland. It is a sand/coral island of , divides Burgle Channel into the northern and the southern entrance, and has a large seabird colony. Islets (''motu''s) in the lagoon include ''Motu Tabu'' () with its ''Pisonia

''Pisonia'' is a genus of flowering plants in the four o'clock flower family, Nyctaginaceae. It was named for Dutch physician and naturalist Willem Piso (1611–1678). Certain species in this genus are known as catchbirdtrees, birdcatcher trees o ...

'' forest and the shrub-covered ''Motu Upua'' (also called Motu Upou or Motu Upoa, ) at the northern side, and ''Ngaontetaake'' () at the eastern side.

''Joe's Hill'' (originally ''La colline de Joe'') on the north coast of the south-eastern peninsula

A peninsula (; ) is a landform that extends from a mainland and is surrounded by water on most, but not all of its borders. A peninsula is also sometimes defined as a piece of land bordered by water on three of its sides. Peninsulas exist on all ...

, southeast of Artemia Corners, is the highest point on the atoll, at about ASL

American Sign Language (ASL) is a natural language that serves as the predominant sign language of Deaf communities in the United States of America and most of Anglophone Canada. ASL is a complete and organized visual language that is express ...

. On the northwestern peninsula for example, the land rises only to some 7 m (20 ft), which is still considerable for an atoll.

Climate

Despite its proximity to the Intertropical Convergence Zone (ITCZ), Kiritimati is located in an equatorial dry zone and rainfall is rather low except duringEl Niño

El Niño (; ; ) is the warm phase of the El Niño–Southern Oscillation (ENSO) and is associated with a band of warm ocean water that develops in the central and east-central equatorial Pacific (approximately between the International Date L ...

years; on average per year, in some years it can be as little as and much of the flats and ponds can dry up such as in late 1978. On the other hand, in some exceptionally wet years abundant downpours in March–April may result in a total annual precipitation of over . Kiritimati is thus affected by regular, severe droughts. They are exacerbated by its geological structure; climatically "dry" Pacific islands are more typically located in the "desert

A desert is a barren area of landscape where little precipitation occurs and, consequently, living conditions are hostile for plant and animal life. The lack of vegetation exposes the unprotected surface of the ground to denudation. About on ...

belt" at about 30°N or S latitude

In geography, latitude is a coordinate that specifies the north– south position of a point on the surface of the Earth or another celestial body. Latitude is given as an angle that ranges from –90° at the south pole to 90° at the north pol ...

. Kiritimati is a raised atoll, and although it does occasionally receive plenty of precipitation

In meteorology, precipitation is any product of the condensation of atmospheric water vapor that falls under gravitational pull from clouds. The main forms of precipitation include drizzle, rain, sleet, snow, ice pellets, graupel and hail. ...

, little is retained given the porous carbonate rock

Carbonate rocks are a class of sedimentary rocks composed primarily of carbonate minerals. The two major types are limestone, which is composed of calcite or aragonite (different crystal forms of CaCO3), and dolomite rock (also known as dolosto ...

, the thin soil

Soil, also commonly referred to as earth or dirt, is a mixture of organic matter, minerals, gases, liquids, and organisms that together support life. Some scientific definitions distinguish ''dirt'' from ''soil'' by restricting the former te ...

, and the absence of dense vegetation cover on much of the island, while evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when humidi ...

is constantly high. Consequently, Kiritimati is one of the rather few places close to the Equator

The equator is a circle of latitude, about in circumference, that divides Earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres. It is an imaginary line located at 0 degrees latitude, halfway between the North and South poles. The term can als ...

which have an effectively arid

A region is arid when it severely lacks available water, to the extent of hindering or preventing the growth and development of plant and animal life. Regions with arid climates tend to lack vegetation and are called xeric or desertic. Most ar ...

climate.

The temperature is constantly between 24 °C and 30 °C (75 °F and 86 °F) with more diurnal temperature variation

In meteorology, diurnal temperature variation is the variation between a high air temperature and a low temperature that occurs during the same day.

Temperature lag

Temperature lag is an important factor in diurnal temperature variation: peak d ...

than seasonal variation. Easterly trade winds

The trade winds or easterlies are the permanent east-to-west prevailing winds that flow in the Earth's equatorial region. The trade winds blow mainly from the northeast in the Northern Hemisphere and from the southeast in the Southern Hemisph ...

predominate.

Demography

At the first census done in theGilbert and Ellice Islands

The Gilbert and Ellice Islands (GEIC as a colony) in the Pacific Ocean were part of the British Empire from 1892 to 1976. They were a protectorate from 1892 to 12 January 1916, and then a colony until 1 January 1976. The history of the colony w ...

colony in 1931, there were only 38 inhabitants on the island, most of them workers of the Company. After WWII in 1947 there were 52 inhabitants. After the nuclear tests, in 1963, this had increased to 477, reducing to 367 by 1967 but increasing again to 674 in 1973, 1,265 in 1978, 1,737 in the 1985 census, 2,537 in 1990, 3,225 in 1995, 3,431 in 2000, 5,115 in 2005, 5,586 in 2010 and 6,456 in 2015. This was the fastest population growth in Kiribati.

Ecology

Theflora

Flora is all the plant life present in a particular region or time, generally the naturally occurring (indigenous) native plants. Sometimes bacteria and fungi are also referred to as flora, as in the terms '' gut flora'' or '' skin flora''.

E ...

and the fauna

Fauna is all of the animal life present in a particular region or time. The corresponding term for plants is ''flora'', and for fungi, it is '' funga''. Flora, fauna, funga and other forms of life are collectively referred to as '' biota''. Zoo ...

consist of taxa

In biology, a taxon (back-formation from ''taxonomy''; plural taxa) is a group of one or more populations of an organism or organisms seen by taxonomists to form a unit. Although neither is required, a taxon is usually known by a particular nam ...

adapted to drought. Terrestrial

Terrestrial refers to things related to land or the planet Earth.

Terrestrial may also refer to:

* Terrestrial animal, an animal that lives on land opposed to living in water, or sometimes an animal that lives on or near the ground, as opposed to ...

fauna is scant; there are no truly native land mammal

Mammals () are a group of vertebrate animals constituting the class Mammalia (), characterized by the presence of mammary glands which in females produce milk for feeding (nursing) their young, a neocortex (a region of the brain), fur or ...

s and only one native land bird – Kiribati's endemic

Endemism is the state of a species being found in a single defined geographic location, such as an island, state, nation, country or other defined zone; organisms that are indigenous to a place are not endemic to it if they are also found elsew ...

reed-warbler, the bokikokiko

The bokikokiko, Kiritimati reed warbler or Christmas Island warbler (''Acrocephalus aequinoctialis'') is a species of warbler in the family Acrocephalidae. It is found only on Kiritimati and Washington Island (Kiribati).

The population size of ...

(''Acrocephalus aequinoctialis''). The 1957 attempt to introduce the endangered

An endangered species is a species that is very likely to become extinct in the near future, either worldwide or in a particular political jurisdiction. Endangered species may be at risk due to factors such as habitat loss, poaching and inva ...

Rimitara lorikeet (''Vini kuhlii'') has largely failed; a few birds seem to linger on, but the lack of abundant coconut palm

The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family (Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, the seed, or the f ...

forest, on which this tiny parrot depends, makes Kiritimati a suboptimal habitat for this species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

.

Flora

The natural vegetation on Kiritimati consists mostly of lowshrubland

Shrubland, scrubland, scrub, brush, or bush is a plant community characterized by vegetation dominated by shrubs, often also including grasses, herbs, and geophytes. Shrubland may either occur naturally or be the result of human activity. It m ...

and grassland

A grassland is an area where the vegetation is dominated by grasses (Poaceae). However, sedge (Cyperaceae) and rush (Juncaceae) can also be found along with variable proportions of legumes, like clover, and other herbs. Grasslands occur natur ...

. What little woodland exists is mainly open coconut palm

The coconut tree (''Cocos nucifera'') is a member of the palm tree family (Arecaceae) and the only living species of the genus ''Cocos''. The term "coconut" (or the archaic "cocoanut") can refer to the whole coconut palm, the seed, or the f ...

(''Cocos nucifera'') plantation. There are three small woods of catchbird trees (''Pisonia grandis

''Pisonia grandis'', the grand devil's-claws, is a species of flowering tree in the ''Bougainvillea'' family, Nyctaginaceae.

Description

The tree has broad, thin leaves, smooth bark and bears clusters of green sweet-smelling flowers that matu ...

''), at Southeast Point, Northwest Point, and on Motu Tabu. The latter was planted there in recent times. About 50 introduced plant species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

are found on Kiritimati; as most are plentiful around settlements, former military sites and roads, it seems that these only became established in the 20th century.

Beach naupaka (''

Beach naupaka (''Scaevola taccada

''Scaevola taccada'', also known as beach cabbage, sea lettuce, or beach naupaka, is a flowering plant in the family Goodeniaceae found in coastal locations in the tropical areas of the Indo-Pacific. It is a common beach shrub throughout the Arab ...

'') is the most common shrub

A shrub (often also called a bush) is a small-to-medium-sized perennial woody plant. Unlike herbaceous plants, shrubs have persistent woody stems above the ground. Shrubs can be either deciduous or evergreen. They are distinguished from trees ...

on Kiritimati; beach naupaka scrub dominates the vegetation on much of the island, either as pure stands or interspersed with tree heliotrope (''Heliotropium foertherianum

''Heliotropium arboreum'' is a species of flowering plant in the borage family, Boraginaceae. It is native to tropical Asia including southern China, Madagascar, northern Australia, and most of the atolls and high islands of Micronesia and Polyn ...

'') and bay cedar ('' Suriana maritima''). The latter species is dominant on the drier parts of the lagoon flats where it grows up to tall. Tree heliotrope is most commonly found a short distance from the sea- or lagoon-shore. In some places near the seashore, a low vegetation dominated by Polynesian heliotrope (''Heliotropium anomalum

''Heliotropium anomalum'' is a species of flowering shrub in the borage family, Boraginaceae, that is native to the Hawaiian Islands, Guam, Christmas Island, Saipan, Tinian, Wake Island and New Caledonia. Common names include Polynesian heliotrop ...

''), yellow purslane (''Portulaca lutea

''Portulaca lutea'', the native yellow purslane, is a species of ''Portulaca'' that is indigenous to all of the main islands of Hawaii except for Kaua'i and is widespread throughout the Pacific Islands.

Ecology

''Portulaca lutea'' is very muc ...

'') and common purslane ('' P. oleracea'') is found. In the south and on the sandier parts, ''Sida fallax

''Sida fallax'', known as yellow ilima or golden mallow, is a species of herbaceous flowering plant in the ''Hibiscus'' family, Malvaceae, indigenous to the Hawaiian Archipelago and other Pacific Islands. Plants may be erect or prostrate and are ...

'', also growing up to 2 m tall, is abundant. On the southeastern peninsula, ''S. fallax'' grows more stunted, and Polynesian heliotrope, yellow and common purslane as well as the spiderling ''Boerhavia repens

''Boerhavia'' is a genus of over 100 species in the Nyctaginaceae family. The genus was named for Herman Boerhaave, a Dutch botanist, and the genus name is frequently misspelled "''Boerhaavia''". Common names include spiderlings and hogweeds.

T ...

'', the parasitic

Parasitism is a close relationship between species, where one organism, the parasite, lives on or inside another organism, the host, causing it some harm, and is adapted structurally to this way of life. The entomologist E. O. Wilson has c ...

vine

A vine (Latin ''vīnea'' "grapevine", "vineyard", from ''vīnum'' "wine") is any plant with a growth habit of trailing or scandent (that is, climbing) stems, lianas or runners. The word ''vine'' can also refer to such stems or runners themselv ...

''Cassytha filiformis

''Cassytha filiformis'' or love-vine is an orangish, wiry, parasitic vine in the laurel family (Lauraceae), found in warm tropical regions worldwide in the Americas, Africa, Asia, Australia, and the Pacific. It is an obligate parasite, meaning it ...

'', and Pacific Island thintail (''Lepturus repens

''Lepturus'' (common name thintail) is a genus of plants in the grass family, native to Asia, Africa, Australia, and various islands in the Indian and Pacific Oceans.

; Species

* '' Lepturus anadabolavensis'' A.Camus - Madagascar

* '' Lepturus a ...

'') supplement it. The last species dominates in the coastal grasslands. The wetter parts of the lagoon shore are often covered by abundant growth of shoreline purslane (''Sesuvium portulacastrum

''Sesuvium portulacastrum'' is a sprawling perennial herb that grows in coastal areas throughout much of the world. It is commonly known as shoreline purslane or (ambiguously) " sea purslane," in English, ''dampalit'' in Tagalog and 海马齿sl ...

'').

Perhaps the most destructive of the recently introduced plants is sweetscent (''Pluchea odorata

''Pluchea odorata'' is a species of flowering plant in the aster family, Asteraceae. Common names include sweetscent, saltmarsh fleabane and shrubby camphorweed.

Distribution

The plant is native to the United States, Mexico, Central America, th ...

''), a camphorweed, which is considered an invasive weed

An invasive species otherwise known as an alien is an introduced organism that becomes overpopulated and harms its new environment. Although most introduced species are neutral or beneficial with respect to other species, invasive species ad ...

as it overgrows and displaces herbs and grasses. The introduced creeper ''Tribulus cistoides

''Tribulus cistoides'', also called wanglo (in Aruba), the Jamaican feverplant or puncture vine, is a species of flowering plant in the family Zygophyllaceae, which is widely distributed in tropical and subtropical regions. Habitat

Tribulus Cist ...

'', despite having also spread conspicuously, is considered to be more beneficial than harmful to the ecosystem

An ecosystem (or ecological system) consists of all the organisms and the physical environment with which they interact. These biotic and abiotic components are linked together through nutrient cycles and energy flows. Energy enters the syste ...

, as it provides good nesting sites for some seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s.

Birds

species

In biology, a species is the basic unit of classification and a taxonomic rank of an organism, as well as a unit of biodiversity. A species is often defined as the largest group of organisms in which any two individuals of the appropriate s ...

have been recorded from Kiritimati. As noted above, only the bokikokiko

The bokikokiko, Kiritimati reed warbler or Christmas Island warbler (''Acrocephalus aequinoctialis'') is a species of warbler in the family Acrocephalidae. It is found only on Kiritimati and Washington Island (Kiribati).

The population size of ...

(''Acrocephalus aequinoctialis''), perhaps a few Rimitara lorikeets (''Vini kuhlii'') – if any remain at all – and the occasional eastern reef egret

The Pacific reef heron (''Egretta sacra''), also known as the eastern reef heron or eastern reef egret, is a species of heron found throughout southern Asia and Oceania. It occurs in two colour morphs with either slaty grey or pure white pluma ...

(''Egretta sacra'') make up the entire landbird fauna. About 1,000 adult bokikokikos are to be found at any date, but mainly in mixed grass/shrubland away from the settlements.

On the other hand, seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s are plentiful on Kiritimati, and make up the bulk of the breeding bird population. There are 18 species of seabirds breeding on the island, and Kiritimati is one of the most important breeding grounds anywhere in the world for several of these:

Phaethontiformes

The Phaethontiformes are an order of birds. They contain one extant family, the tropicbirds (Phaethontidae), and one extinct family Prophaethontidae from the early Cenozoic. Several fossil genera have been described.

The tropicbirds were tradit ...

* Eastern red-tailed tropicbird

The red-tailed tropicbird (''Phaethon rubricauda'') is a seabird native to tropical parts of the Indian and Pacific Oceans. One of three closely related species of tropicbird (Phaethontidae), it was described by Pieter Boddaert in 1783. Superfic ...

(''Phaethon rubricauda melanorhynchus'') – important breeding colony; 8,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline, fewer than 3,000 in 1984

Charadriiformes

Charadriiformes (, from ''Charadrius'', the type genus of family Charadriidae) is a diverse order of small to medium-large birds. It includes about 390 species and has members in all parts of the world. Most charadriiform birds live near water an ...

* Micronesian black noddy

The black noddy or white-capped noddy (''Anous minutus'') is a seabird from the family Laridae. It is a medium-sized species of tern with black plumage and a white cap. It closely resembles the lesser noddy (''Anous tenuirostris'') with which it w ...

(''Anous minutus marcusi'') – 20,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Little white tern (''Gygis microrhyncha'') – 8,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Central Pacific sooty tern

The sooty tern (''Onychoprion fuscatus'') is a seabird in the family Laridae. It is a bird of the tropical oceans, returning to land only to breed on islands throughout the equatorial zone.

Taxonomy

The sooty tern was described by Carl Linnaeu ...

(''Onychoprion fuscatus oahuensis'') – largest breeding colony in the world; around 7,000,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Spectacled tern

The spectacled tern (''Onychoprion lunatus''), also known as the grey-backed tern, is a seabird in the family Laridae.

Description

A close relative of the bridled and sooty terns (with which it is sometimes confused), the spectacled tern is les ...

(''Onychoprion lunatus'') – important breeding colony; 6,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Central blue-grey noddy (''Procelsterna cerulea cerulea'') – important breeding colony, possibly the largest worldwide of this subspecies; 4,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

Procellariiformes

Procellariiformes is an order of seabirds that comprises four families: the albatrosses, the petrels and shearwaters, and two families of storm petrels. Formerly called Tubinares and still called tubenoses in English, procellariiforms are of ...

* Polynesian storm petrel

The Polynesian storm petrel (''Nesofregetta fuliginosa'') is a species of seabird in the family Oceanitidae. It is the only species placed in the genus ''Nesofregetta''.

Markedly polymorphic, several subspecies were described, and light birds w ...

(''Nesofregetta fuliginosa'') – important breeding colony; 1,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Phoenix petrel (''Pterodroma alba'') – largest breeding colony in the world; 24,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Christmas shearwater

The Christmas shearwater or ''aoū'' (''Puffinus nativitatis'') is a medium-sized shearwater of the tropical Central Pacific. It is a poorly known species due to its remote nesting habits, and it has not been extensively studied at sea either. ...

(''Puffinus nativitatis'') – largest subpopulation

In statistics, a population is a Set (mathematics), set of similar items or events which is of interest for some question or experiment. A statistical population can be a group of existing objects (e.g. the set of all stars within the Milky Way g ...

worldwide on Motu Upua; 12,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Wedge-tailed shearwater

The wedge-tailed shearwater (''Ardenna pacifica'') is a medium-large shearwater in the seabird family Procellariidae. It is one of the shearwater species that is sometimes referred to as a muttonbird, like the sooty shearwater of New Zealand and ...

(''Puffinus pacificus'') – among the very largest breeding colonies in the world; about 1,000,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

Pelecaniformes

The Pelecaniformes are an order of medium-sized and large waterbirds found worldwide. As traditionally—but erroneously—defined, they encompass all birds that have feet with all four toes webbed. Hence, they were formerly also known by such ...

* Indopacific lesser frigatebird

The lesser frigatebird (''Fregata ariel'') is a seabird of the frigatebird family Fregatidae. At around 75 cm (30 in) in length, it is the smallest species of frigatebird. It occurs over tropical and subtropical waters across the Indian ...

(''Fregata ariel ariel'') – important breeding colony; 9,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Central Pacific great frigatebird

The great frigatebird (''Fregata minor'') is a large seabird in the frigatebird family. There are major nesting populations in the tropical Pacific (including the Galapagos Islands) and Indian Oceans, as well as a tiny population in the South At ...

(''Fregata minor palmerstoni'') – important breeding colony; 12,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline, 6,500 afterwards

* Austropacific masked booby

The masked booby (''Sula dactylatra''), also called the masked gannet or the blue-faced booby, is a large seabird of the booby and gannet family, Sulidae. First described by the French naturalist René-Primevère Lesson in 1831, the masked bo ...

(''Sula dactylatra personata'') – important breeding colony; 3,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

* Indopacific red-footed booby (''Sula sula rubripes'') – 12,000 birds before the 1982–1983 decline

Kiritimati's lagoon and the saltflats are a prime location for migratory bird

Bird migration is the regular seasonal movement, often north and south along a flyway, between Breeding in the wild, breeding and wintering grounds. Many species of bird migrate. Animal migration, Migration carries high costs in predation a ...

s to stop over or even stay all winter. The most commonly seen migrants are ruddy turnstone

The ruddy turnstone (''Arenaria interpres'') is a small cosmopolitan wading bird, one of two species of turnstone in the genus ''Arenaria''.

It is now classified in the sandpiper family Scolopacidae but was formerly sometimes placed in the plov ...

(''Arenaria interpres''), Pacific golden plover (''Pluvialis fulva''), bristle-thighed curlew

The bristle-thighed curlew (''Numenius tahitiensis'') is a medium-sized shorebird that breeds in Alaska and winters on tropical Pacific islands.

It is known in Mangareva as ''kivi'' or ''kivikivi'' and in Rakahanga as ''kihi''; it is said to be ...

(''Numenius tahitiensis''), and wandering tattler

The wandering tattler (''Tringa incana''; formerly ''Heteroscelus incanus'': Pereira & Baker, 2005; Banks ''et al.'', 2006), is a medium-sized wading bird. It is similar in appearance to the closely related gray-tailed tattler, ''T. brevipes''. ...

(''Tringa incana''); other seabird

Seabirds (also known as marine birds) are birds that are adapted to life within the marine environment. While seabirds vary greatly in lifestyle, behaviour and physiology, they often exhibit striking convergent evolution, as the same enviro ...

s, wader

245px, A flock of Dunlins and Red knots">Red_knot.html" ;"title="Dunlins and Red knot">Dunlins and Red knots

Waders or shorebirds are birds of the order Charadriiformes commonly found wikt:wade#Etymology 1, wading along shorelines and mudflat ...

s, and even dabbling duck

The Anatinae are a subfamily of the family Anatidae ( swans, geese and ducks). Its surviving members are the dabbling ducks, which feed mainly at the surface rather than by diving. The other members of the Anatinae are the extinct moa-nalo, a yo ...

s can be encountered every now and then. Around 7 October (±5 days), some 20 million sooty shearwaters pass through here en route from the North Pacific feeding grounds to breeding sites around New Zealand

New Zealand ( mi, Aotearoa ) is an island country in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It consists of two main landmasses—the North Island () and the South Island ()—and over 700 smaller islands. It is the sixth-largest island count ...

.

Other fauna

The only mammals native to the region are the commonPolynesian rat

The Polynesian rat, Pacific rat or little rat (''Rattus exulans''), known to the Māori as ''kiore'', is the third most widespread species of rat in the world behind the brown rat and black rat. The Polynesian rat originated in Southeast Asia, a ...

(''Rattus exulans'') and the goats. The rat seems to have been introduced by seafarers many centuries before Cook arrived in 1777 (he mentioned them already being present); goats have been extinct since 14 January 2004. Black rat

The black rat (''Rattus rattus''), also known as the roof rat, ship rat, or house rat, is a common long-tailed rodent of the stereotypical rat genus ''Rattus'', in the subfamily Murinae. It likely originated in the Indian subcontinent, but is n ...

s (''Rattus rattus'') were present at some time, perhaps introduced by 19th century sailors or during the nuclear tests. They were not able to gain a foothold between predation

Predation is a biological interaction where one organism, the predator, kills and eats another organism, its prey. It is one of a family of common feeding behaviours that includes parasitism and micropredation (which usually do not kill the ...

by cats and competitive exclusion

In ecology, the competitive exclusion principle, sometimes referred to as Gause's law, is a proposition that two species which compete for the same limited resource cannot coexist at constant population values. When one species has even the sligh ...

by Polynesian rats, and no black rat population is found on Kiritimati today.

Up to 2,000 feral cat

A feral cat or a stray cat is an unowned domestic cat (''Felis catus'') that lives outdoors and avoids human contact: it does not allow itself to be handled or touched, and usually remains hidden from humans. Feral cats may breed over dozens ...

s can in some years be found on the island; the population became established in the 19th century. Their depredations seriously harm the birdlife. Since the late 19th century, they have driven about 60% of the seabird species from the mainland completely, and during particular dry spells they will cross the mudflats and feast upon the birds on the ''motu''s. Spectacled tern

The spectacled tern (''Onychoprion lunatus''), also known as the grey-backed tern, is a seabird in the family Laridae.

Description

A close relative of the bridled and sooty terns (with which it is sometimes confused), the spectacled tern is les ...

chicks seem to be a favourite food of the local cat population. There are some measures being taken to ensure the cat population does not grow. That lowering the cat population by some amount would much benefit Christmas and its inhabitants is generally accepted, but the situation is too complex to simply go and eradicate them outright (which is theoretically possible; see Marion Island) – see below for details. A limited population of feral pigs

The feral pig is a domestic pig which has gone feral, meaning it lives in the wild. They are found mostly in the Americas and Australia. Razorback and wild hog are Americanisms applied to feral pigs or boar-pig hybrids.

Definition

A feral p ...

exists. They were once plentiful and wreaked havoc especially on the ''Onychoprion

''Onychoprion'', the "brown-backed terns", is a genus of seabirds in the family Laridae. The genus name is from Ancient Greek , "claw" or "nail", and , "saw".

Species

Although the genus was first described in 1832 by Johann Georg Wagler the four ...

'' and noddies. Pig hunting by locals has been encouraged, and was highly successful at limiting the pig population to a sustainable level, while providing a source of cheap protein for the islanders.

There are some "supertramp"

There are some "supertramp" lizard

Lizards are a widespread group of squamate reptiles, with over 7,000 species, ranging across all continents except Antarctica, as well as most oceanic island chains. The group is paraphyletic since it excludes the snakes and Amphisbaenia alt ...

s which have reached the island by their own means. Commonly seen are the mourning gecko (''Lepidodactylus lugubris'') and the skink

Skinks are lizards belonging to the family Scincidae, a family in the infraorder Scincomorpha. With more than 1,500 described species across 100 different taxonomic genera, the family Scincidae is one of the most diverse families of lizards. Ski ...

'' Cryptoblepharus boutonii''; the four-clawed gecko

''Gehyra mutilata'', also known commonly as the common four-clawed gecko, Pacific gecko, stump-toed gecko, sugar gecko in Indonesia, tender-skinned house gecko, and ''butiki'' in Filipino, is a species of lizard in the family Gekkonidae. The sp ...

(''Gehyra mutilata'') is seen less often.

There are some crustacean

Crustaceans (Crustacea, ) form a large, diverse arthropod taxon which includes such animals as decapods, seed shrimp, branchiopods, fish lice, krill, remipedes, isopods, barnacles, copepods, amphipods and mantis shrimp. The crustacean group ...

s of note to be found on Kiritimati and in the waters immediately adjacent. The amphibious coconut crab

The coconut crab (''Birgus latro'') is a species of terrestrial hermit crab, also known as the robber crab or palm thief. It is the largest terrestrial arthropod in the world, with a weight of up to . It can grow to up to in width from the tip ...

(''Birgus latro'') is not as common as on Teraina

Teraina (written also Teeraina, also known as Washington Island – these two names are constitutional) is a coral atoll in the central Pacific Ocean and part of the Northern Line Islands which belong to Kiribati. Obsolete names of Teraina a ...

. Ghost crab

Ghost crabs are semiterrestrial crabs of the subfamily Ocypodinae. They are common shore crabs in tropical and subtropical regions throughout the world, inhabiting deep burrows in the intertidal zone. They are generalist scavengers and predators ...

s (genus

Genus ( plural genera ) is a taxonomic rank used in the biological classification of extant taxon, living and fossil organisms as well as Virus classification#ICTV classification, viruses. In the hierarchy of biological classification, genus com ...

''Ocypode''), '' Cardisoma carnifex'' and ''Geograpsus grayi

''Geograpsus'' is a genus of crabs in the family Grapsidae

The Grapsidae are a family of crabs known variously as marsh crabs, shore crabs, or talon crabs. The family has not been confirmed to form a monophyletic group and some taxa may belo ...

'' land crab

A number of lineages of crabs have evolved to live predominantly on land. Examples of terrestrial crabs are found in the families Gecarcinidae and Gecarcinucidae, as well as in selected genera from other families, such as ''Sesarma'', althou ...

s, the strawberry land hermit crab

''Coenobita perlatus'' is a species of terrestrial animal, terrestrial hermit crab. It is known as the strawberry hermit crab because of its reddish-orange colours. It is a widespread scavenger across the Indo-Pacific, and wild-caught specimens ...

(''Coenobita perlatus'') are also notable. Introduced brine shrimp ''Artemia salina

''Artemia salina'' is a species of brine shrimp – aquatic crustaceans that are more closely related to '' Triops'' and cladocerans than to true shrimp. It belongs to a lineage that does not appear to have changed much in .

''A. salina'' is na ...

'' populate the island's saline ponds.

Ecology of the reef

Overfishing and pollution have impacted on the ocean surrounding the island. In the ocean surrounding uninhabited islands of the Northern Line Islands,Shark

Sharks are a group of elasmobranch fish characterized by a cartilaginous skeleton, five to seven gill slits on the sides of the head, and pectoral fins that are not fused to the head. Modern sharks are classified within the clade Selachimo ...

s comprised 74% of the top predator biomass (329 g/m2) at Kingman Reef

Kingman Reef is a largely submerged, uninhabited, triangle-shaped reef, geologically an atoll, east-west and north-south, in the North Pacific Ocean, roughly halfway between the Hawaiian Islands and American Samoa. It has an area of 3 hectar ...

and 57% at Palmyra Atoll

Palmyra Atoll (), also referred to as Palmyra Island, is one of the Line Islands, Northern Line Islands (southeast of Kingman Reef and north of Kiribati). It is located almost due south of the Hawaiian Islands, roughly one-third of the way bet ...

(97 g/m2), whereas low shark numbers have been observed at Tabuaeran

Tabuaeran, also known as Fanning Island, is an atoll that is part of the Line Islands of the central Pacific Ocean and part of Kiribati. The land area is , and the population in 2015 was 2,315. The maximum elevation is about 3 m (10 f ...

and Kiritimati.

Green turtle

The green sea turtle (''Chelonia mydas''), also known as the green turtle, black (sea) turtle or Pacific green turtle, is a species of large sea turtle of the Family (biology), family Cheloniidae. It is the only species

In biology, a spec ...

s (''Chelonia mydas'') regularly nest in small numbers on Kiritimati. The lagoon is famous among sea anglers worldwide for its bonefish

The bonefish (''Albula vulpes'') is the type species of the bonefish family (Albulidae), the only family in order Albuliformes.

History

Bonefish were once believed to be a single species with a global distribution, however 9 different species ...

(''Albula glossodonta''), and has been stocked with ''Oreochromis

''Oreochromis'' is a large genus of oreochromine cichlids, fishes endemic to Africa and the Middle East. A few species from this genus have been introduced far outside their native range and are important in aquaculture. Many others have very ...

'' tilapia

Tilapia ( ) is the common name for nearly a hundred species of cichlid fish from the coelotilapine, coptodonine, heterotilapine, oreochromine, pelmatolapiine, and tilapiine tribes (formerly all were "Tilapiini"), with the economically most ...

to decrease overfishing

Overfishing is the removal of a species of fish (i.e. fishing) from a body of water at a rate greater than that the species can replenish its population naturally (i.e. the overexploitation of the fishery's existing fish stock), resulting in th ...

of marine species. Though the tilapias thrive in brackish water

Brackish water, sometimes termed brack water, is water occurring in a natural environment that has more salinity than freshwater, but not as much as seawater. It may result from mixing seawater (salt water) and fresh water together, as in estua ...

of the flats, they will not last long should they escape into the surrounding ocean.

Giant Trevally

The giant trevally (''Caranx ignobilis''), also known as the lowly trevally, barrier trevally, ronin jack, giant kingfish or ''ulua'', is a species of large marine fish classified in the jack family, Carangidae. The giant trevally is distributed ...

(Caranx ignobilis) are found in large numbers both inside and outside of the lagoon and along the surrounding reefs. Very large specimens of Giant Trevally can be found around these surrounding reefs and they are sought after by many fishermen in addition to Bonefish.

Conservation and extinction

In December 1960, the British colonial authority gazetted Kiritimati as a

In December 1960, the British colonial authority gazetted Kiritimati as a bird sanctuary

An animal sanctuary is a facility where animals are brought to live and to be protected for the rest of their lives. Pattrice Jones, co-founder of VINE Sanctuary defines an animal sanctuary as "a safe-enough place or relationship within the cont ...

under the "Gilbert and Ellice Island Colony Wild Birds Protection Ordinance" of 1938. Access to Cook Island, Motu Tabu, and Motu Upua was restricted. Kiritimati was declared a Wildlife Sanctuary

A nature reserve (also known as a wildlife refuge, wildlife sanctuary, biosphere reserve or bioreserve, natural or nature preserve, or nature conservation area) is a protected area of importance for flora, fauna, or features of geological or o ...

in May 1975, in accordance with the Wildlife Conservation Ordinance of the then self-governing colony. Ngaontetaake and the sooty tern