King Canute on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Cnut (; ang, Cnut cyning; non, Knﺣﭦtr inn rﺣki ; or , no, Knut den mektige, sv, Knut den Store. died 12 November 1035), also known as Cnut the Great and Canute, was

Among the allies of Denmark was

Among the allies of Denmark was

Cnut returned southward, and the Danish army evidently divided, some dealing with Edmund, who had broken out of London before Cnut's encirclement of the city was complete, and had gone to gather an army in

Cnut returned southward, and the Danish army evidently divided, some dealing with Edmund, who had broken out of London before Cnut's encirclement of the city was complete, and had gone to gather an army in

Cnut ruled

Cnut ruled

At the

At the

Cnut was generally remembered as a wise and successful king of England, although this view may in part be attributable to his good treatment of the Church, keeper of the historic record. Accordingly, we hear of him, even today, as a religious man despite the fact that he was in an arguably sinful relationship, with two wives, and the harsh treatment he dealt his fellow Christian opponents.

Under his reign, Cnut brought together the English and Danish kingdoms, and the Scandinavic and Saxon peoples saw a period of dominance across

Cnut was generally remembered as a wise and successful king of England, although this view may in part be attributable to his good treatment of the Church, keeper of the historic record. Accordingly, we hear of him, even today, as a religious man despite the fact that he was in an arguably sinful relationship, with two wives, and the harsh treatment he dealt his fellow Christian opponents.

Under his reign, Cnut brought together the English and Danish kingdoms, and the Scandinavic and Saxon peoples saw a period of dominance across

His enemies in Scandinavia subdued, and apparently at his leisure, Cnut was able to accept an invitation to witness the accession in

His enemies in Scandinavia subdued, and apparently at his leisure, Cnut was able to accept an invitation to witness the accession in

In his 1027 letter, Cnut refers to himself as king of "the Norwegians, and of some of the Swedes" ﻗ his victory over Swedes suggests Helgeﺣ۴ to be the river in Uppland and not Helge River, the one in eastern Scania ﻗ while the king of Sweden appears to have been made a renegade. Cnut also stated his intention of proceeding to Denmark to secure peace between the kingdoms of

In his 1027 letter, Cnut refers to himself as king of "the Norwegians, and of some of the Swedes" ﻗ his victory over Swedes suggests Helgeﺣ۴ to be the river in Uppland and not Helge River, the one in eastern Scania ﻗ while the king of Sweden appears to have been made a renegade. Cnut also stated his intention of proceeding to Denmark to secure peace between the kingdoms of

Cnut's actions as a conqueror and his ruthless treatment of the overthrown dynasty had made him uneasy with the Church. He was already a Christian before he was kingﻗbeing named ''Lambert'' at his baptismAdam of Bremen, ''Gesta Daenorum'', scholium 37, p. 112.ﻗalthough the Christianization of Scandinavia was not at all complete. His marriage to

Cnut's actions as a conqueror and his ruthless treatment of the overthrown dynasty had made him uneasy with the Church. He was already a Christian before he was kingﻗbeing named ''Lambert'' at his baptismAdam of Bremen, ''Gesta Daenorum'', scholium 37, p. 112.ﻗalthough the Christianization of Scandinavia was not at all complete. His marriage to

Cnut died at Shaftesbury in

Cnut died at Shaftesbury in

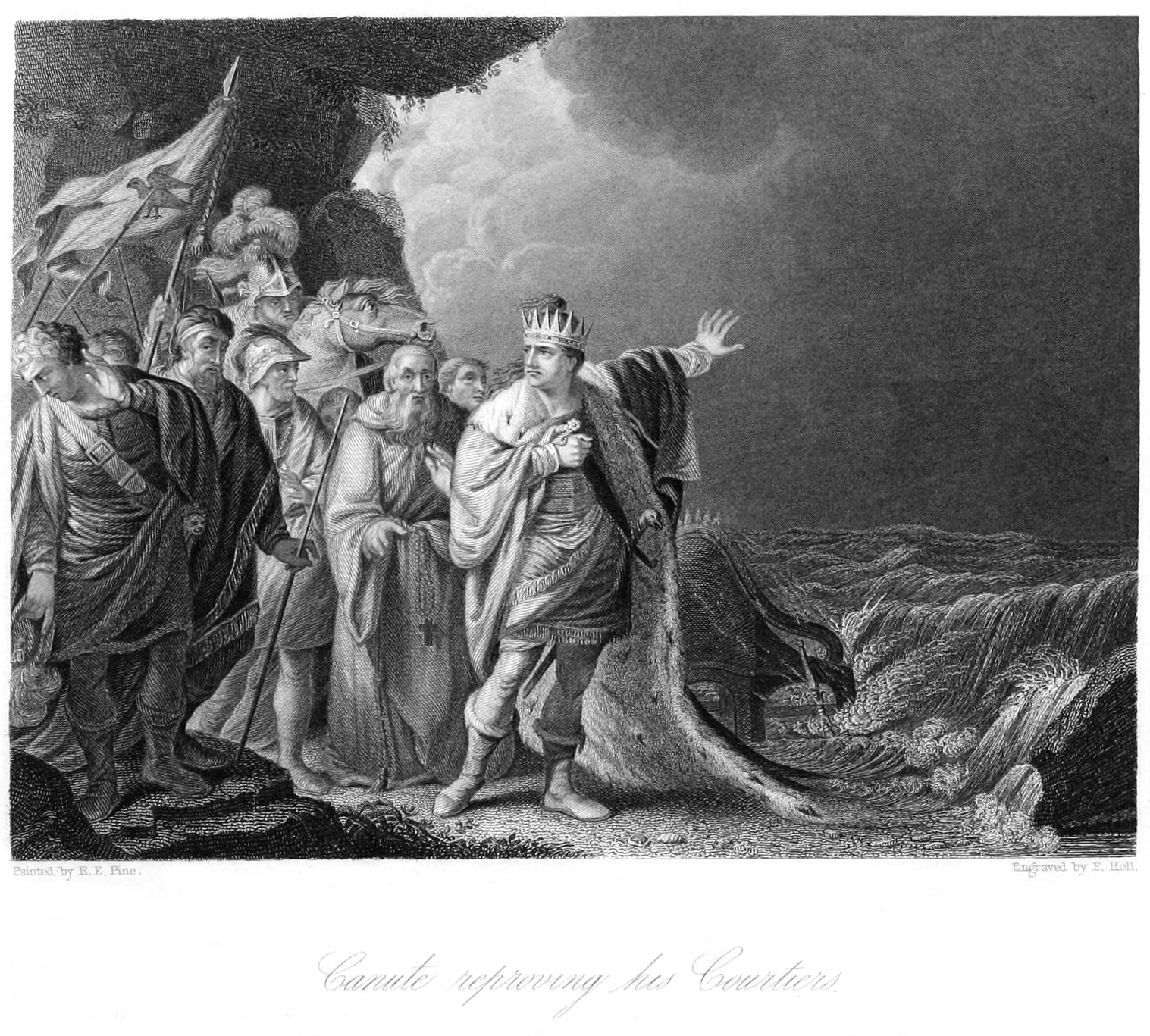

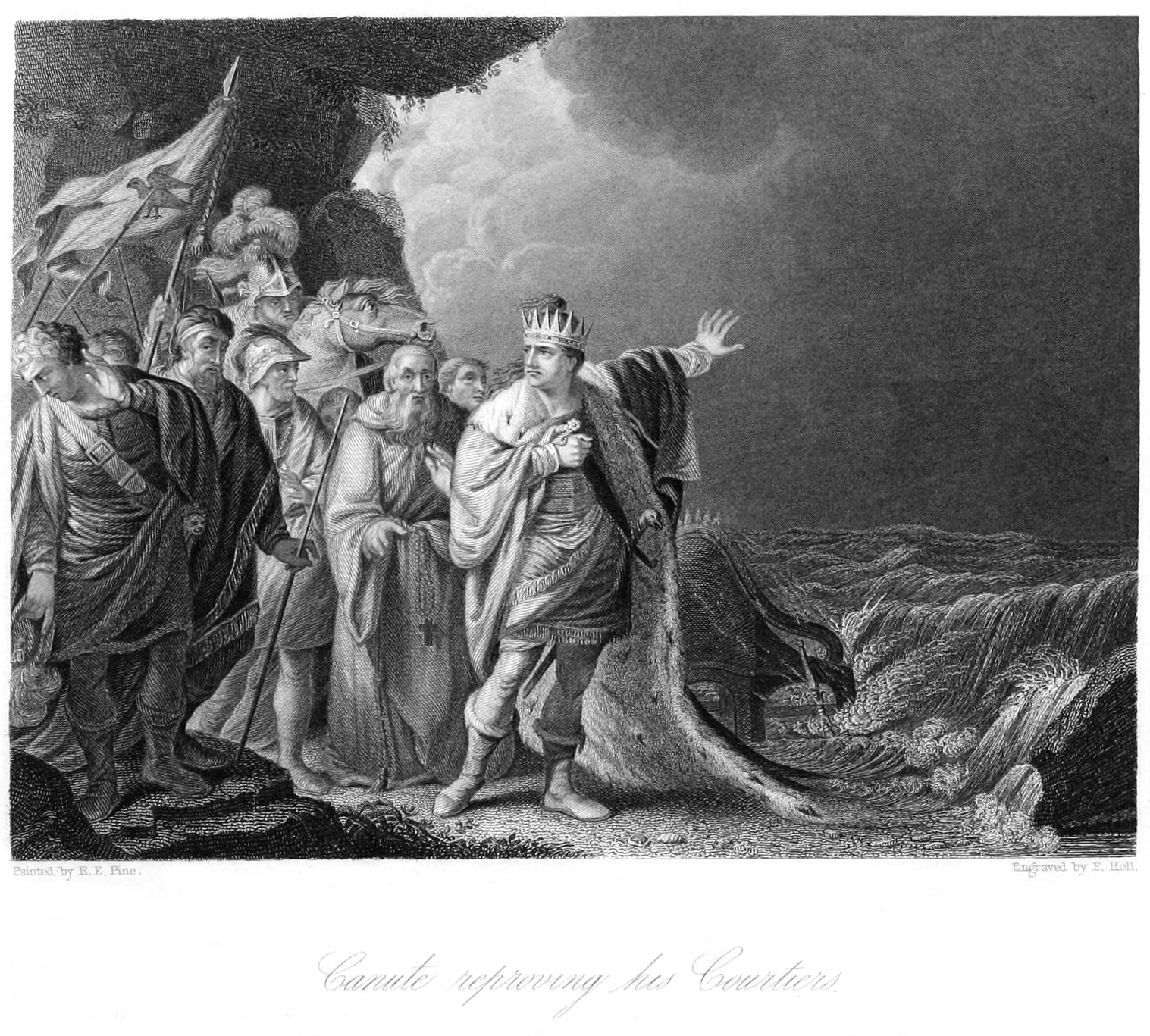

This story of Cnut resisting the incoming tide was first recorded by Henry of Huntingdon in his ''Historia Anglorum'' in the early twelfth century:

This has become by far the best known story about Cnut, although in modern readings he is usually a wise man who knows from the start that he cannot control the waves.

This story of Cnut resisting the incoming tide was first recorded by Henry of Huntingdon in his ''Historia Anglorum'' in the early twelfth century:

This has become by far the best known story about Cnut, although in modern readings he is usually a wise man who knows from the start that he cannot control the waves.

Canute (Knud) The Great ﻗ From Viking warrior to English king

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cnut the Great Cnut the Great, 990s births 1035 deaths 11th-century English monarchs 10th-century Danish people 11th-century kings of Denmark 11th-century Norwegian monarchs Anglo-Norse monarchs Burials at Winchester Cathedral Danish people of Polish descent English people of Polish descent Christian monarchs House of Knﺣﺛtlinga House of Wessex Monarchs of England before 1066 Danish princes

King of England

The monarchy of the United Kingdom, commonly referred to as the British monarchy, is the constitutional form of government by which a hereditary sovereign reigns as the head of state of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies (the Baili ...

from 1016, King of Denmark

The monarchy of Denmark is a constitutional political system, institution and a historic office of the Kingdom of Denmark. The Kingdom includes Denmark proper and the autonomous administrative division, autonomous territories of the Faroe ...

from 1018, and King of Norway

The Norwegian monarch is the head of state of Norway, which is a constitutional and hereditary monarchy with a parliamentary system. The Norwegian monarchy can trace its line back to the reign of Harald Fairhair and the previous petty kingd ...

from 1028 until his death in 1035. The three kingdoms united under Cnut's rule are referred to together as the North Sea Empire

The North Sea Empire, also known as the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire, was the personal union of the kingdoms of England, Denmark and Norway for most of the period between 1013 and 1042 towards the end of the Viking Age. This ephemeral Norse-ruled e ...

.

As a Danish prince, Cnut won the throne of England in 1016 in the wake of centuries of Viking activity in northwestern Europe. His later accession to the Danish throne in 1018 brought the crowns of England and Denmark together. Cnut sought to keep this power-base by uniting Danes and English under cultural bonds of wealth and custom. After a decade of conflict with opponents in Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sﺣ۰mi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

, Cnut claimed the crown of Norway in Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Trﺣ۴ante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trﺣﺕndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, an ...

in 1028. The Swedish city Sigtuna

Sigtuna () is a locality situated in Sigtuna Municipality, Stockholm County, Sweden with 8,444 inhabitants in 2010. It is the namesake of the municipality even though the seat is in Mﺣ۳rsta.

Sigtuna is for historical reasons often still ref ...

was held by Cnut (he had coins struck there that called him king, but there is no narrative record of his occupation). In 1031, Malcolm II of Scotland also submitted to him, though Anglo-Norse influence over Scotland was weak and ultimately did not last by the time of Cnut's death.Trow, ''Cnut'', pp. 197ﻗ98.ASC, Ms. D, s.a. 1031.

Dominion of England lent the Danes

Danes ( da, danskere, ) are a North Germanic ethnic group and nationality native to Denmark and a modern nation identified with the country of Denmark. This connection may be ancestral, legal, historical, or cultural.

Danes generally regard ...

an important link to the maritime zone between the islands of Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, ﺣire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, where Cnut, like his father before him, had a strong interest and wielded much influence among the NorseﻗGaels. Cnut's possession of England's diocese

In church governance, a diocese or bishopric is the ecclesiastical district under the jurisdiction of a bishop.

History

In the later organization of the Roman Empire, the increasingly subdivided provinces were administratively associat ...

s and the continental Diocese of Denmarkﻗwith a claim laid upon it by the Holy Roman Empire

The Holy Roman Empire was a political entity in Western, Central, and Southern Europe that developed during the Early Middle Ages and continued until its dissolution in 1806 during the Napoleonic Wars.

From the accession of Otto I in 962 ...

's Archdiocese of Hamburg-Bremenﻗwas a source of great prestige and leverage within the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and among the magnates of Christendom

Christendom historically refers to the Christian states, Christian-majority countries and the countries in which Christianity dominates, prevails,SeMerriam-Webster.com : dictionary, "Christendom"/ref> or is culturally or historically intertwin ...

(gaining notable concessions such as one on the price of the pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropoli ...

of his bishops, though they still had to travel to obtain the pallium, as well as on the tolls his people had to pay on the way to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

). After his 1026 victory against Norway and Sweden, and on his way back from Rome where he attended the coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor

The Coronation of the Holy Roman Emperor was a ceremony in which the ruler of Western Europe's then-largest political entity received the Imperial Regalia from the hands of the Pope, symbolizing both the pope's right to crown Christian sovereigns ...

, Cnut deemed himself "King of all England and Denmark and the Norwegians and of some of the Swedes" in a letter written for the benefit of his subjects. The Anglo-Saxon kings used the title "king of the English". Cnut was ﻗ"king of all England". Medieval historian Norman Cantor

Norman Frank Cantor (November 19, 1929 ﻗ September 18, 2004) was a Canadian-American historian who specialized in the medieval period. Known for his accessible writing and engaging narrative style, Cantor's books were among the most widely rea ...

called him "the most effective king in Anglo-Saxon history".

Birth and kingship

Cnut was a son of the Danish princeSweyn Forkbeard

Sweyn Forkbeard ( non, Sveinn Haraldsson tjﺣﭦguskegg ; da, Svend Tveskﺣ۵g; 17 April 963 ﻗ 3 February 1014) was King of Denmark from 986 to 1014, also at times King of the English and King of Norway. He was the father of King Harald II of ...

, who was the son and heir to King Harald Bluetooth

Harald "Bluetooth" Gormsson ( non, Haraldr Blﺣ۰tﮄ،nn Gormsson; da, Harald Blﺣ۴tand Gormsen, died c. 985/86) was a king of Denmark and Norway.

He was the son of King Gorm the Old and of Thyra Dannebod. Harald ruled as king of Denmark from c. 9 ...

and thus came from a line of Scandinavian rulers central to the unification of Denmark. Neither the place nor the date of his birth are known. Harthacnut I

Harthacnut or Cnut I ( da, Hardeknud) was a semi-legendary King of Denmark. The old Norse story ''Ragnarssona ﺣﺝﺣ۰ttr'' makes Harthacnut son of the semi-mythic viking chieftain Sigurd Snake-in-the-Eye, himself one of the sons of the legendary ...

was the semi-legendary founder of the Danish royal house at the beginning of the 10th century, and his son, Gorm the Old

Gorm the Old ( da, Gorm den Gamle; non, Gormr gamli; la, Gormus Senex), also called Gorm the Languid ( da, Gorm Lﺣﺕge, Gorm den Dvaske), was ruler of Denmark, reigning from to his death or a few years later.Lund, N. (2020), p. 147

, became the first in the official line (the 'Old' in his name indicates this). Harald Bluetooth, Gorm's son and Cnut's grandfather, was the Danish king at the time of the Christianization of Denmark; he became one of the first Scandinavian kings to accept Christianity.

The '' Chronicon'' of Thietmar of Merseburg

Thietmar (also Dietmar or Dithmar; 25 July 9751 December 1018), Prince-Bishop of Merseburg from 1009 until his death, was an important chronicler recording the reigns of German kings and Holy Roman Emperors of the Ottonian (Saxon) dynasty. ...

and the ''Encomium Emmae

''Encomium Emmae Reginae'' or ''Gesta Cnutonis Regis'' is an 11th-century Latin encomium in honour of the English queen Emma of Normandy. It was written in 1041 or 1042, probably by a monk of Saint-Omer, Normandy.

Manuscripts

Until 2008, it w ...

'' report Cnut's mother as having been ﺧwiﺥtosﺧawa

ﺧwiﺥtosﺧawa was a Polish princess, the daughter of Mieszko I of Poland and sister of Bolesﺧaw I of Poland. According to German chroniclers, this princess, whose name is not given, was married first to Eric the Victorious of Sweden and the ...

, a daughter of Mieszko I of Poland

Mieszko I (; ﻗ 25 May 992) was the first ruler of Poland and the founder of the first independent Polish state, the Duchy of Poland. His reign stretched from 960 to his death and he was a member of the Piast dynasty, a son of Siemomysﺧ and a ...

.

Norse

Norse is a demonym for Norsemen, a medieval North Germanic ethnolinguistic group ancestral to modern Scandinavians, defined as speakers of Old Norse from about the 9th to the 13th centuries.

Norse may also refer to:

Culture and religion

* Nor ...

sources of the High Middle Ages

The High Middle Ages, or High Medieval Period, was the period of European history that lasted from AD 1000 to 1300. The High Middle Ages were preceded by the Early Middle Ages and were followed by the Late Middle Ages, which ended around AD ...

, most prominently ''Heimskringla

''Heimskringla'' () is the best known of the Old Norse kings' sagas. It was written in Old Norse in Iceland by the poet and historian Snorre Sturlason (1178/79ﻗ1241) 1230. The name ''Heimskringla'' was first used in the 17th century, derive ...

'' by Snorri Sturluson

Snorri Sturluson ( ; ; 1179 ﻗ 22 September 1241) was an Icelandic historian, poet, and politician. He was elected twice as lawspeaker of the Icelandic parliament, the Althing. He is commonly thought to have authored or compiled portions of th ...

, also give a Polish princess as Cnut's mother, whom they call Gunhild, a daughter of '' Burislav'', the king of '' Vindland''.

Since in the Norse saga

is a series of science fantasy role-playing video games by Square Enix. The series originated on the Game Boy in 1989 as the creation of Akitoshi Kawazu at Square. It has since continued across multiple platforms, from the Super NES to the Pl ...

s the ''king of Vindland'' is always ''Burislav'', this is reconcilable with the assumption that her father was Mieszko (not his son Bolesﺧaw). Adam of Bremen in ''Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum

''Gesta Hammaburgensis ecclesiae pontificum'' (Medieval Latin for ''"Deeds of the Bishops of Hamburg"'') is a historical treatise written between 1073 and 1076 by Adam of Bremen, who made additions (''scholia'') to the text until his death (poss ...

'' is unique in equating Cnut's mother (for whom he also produces no name) with the former queen of Sweden, wife of Eric the Victorious

Eric the Victorious (Old Norse: ''Eirﺣkr inn sigrsﺣ۵li'', Modern Swedish: ''Erik Segersﺣ۳ll''; c. 945 ﻗ c. 995) was a Swedish monarch as of around 970. Although there were earlier Swedish kings, he is the first Swedish king in a consecutive reg ...

and by this marriage mother of Olof Skﺣﭘtkonung

Olof Skﺣﭘtkonung, (Old Norse: ''ﺣlﺣ۰fr skautkonungr'') sometimes stylized as ''Olaf the Swede'' (c. 980–1022), was King of Sweden, son of Eric the Victorious and, according to Icelandic sources, Sigrid the Haughty. He succeeded his father in ...

.

To complicate the matter, ''Heimskringla'' and other sagas also have Sweyn marrying Eric's widow, but she is distinctly another person in these texts, named ''Sigrid the Haughty

Sigrid the Haughty (Old Norse:''Sigrﺣﺣﺍr (hin) stﺣﺏrrﺣ۰ﺣﺍa''), also known as ''Sigrid Storrﺣ۴da'' (Swedish), is a Scandinavian queen appearing in Norse sagas. Sigrid is named in several late and sometimes contradictory Icelandic sagas composed g ...

'', whom Sweyn only marries after ''Gunhild'', the Slavic princess who bore Cnut, has died.

Different theories regarding the number and ancestry of Sweyn's wives (or wife) have been advanced (see Sigrid the Haughty

Sigrid the Haughty (Old Norse:''Sigrﺣﺣﺍr (hin) stﺣﺏrrﺣ۰ﺣﺍa''), also known as ''Sigrid Storrﺣ۴da'' (Swedish), is a Scandinavian queen appearing in Norse sagas. Sigrid is named in several late and sometimes contradictory Icelandic sagas composed g ...

and Gunhild). But since Adam is the only source to equate the identity of Cnut's and Olof Skﺣﭘtkonung's mother, this is often seen as an error on Adam's part, and it is often assumed that Sweyn had two wives, the first being Cnut's mother, and the second being the former Queen of Sweden. Cnut's brother Harald was the younger of the two brothers according to ''Encomium Emmae''.

Some hint of Cnut's childhood can be found in the ''Flateyjarbﺣﺏk

''Flateyjarbﺣﺏk'' (; "Book of Flatey") is an important medieval Icelandic manuscript. It is also known as GkS 1005 fol. and by the Latin name ''Codex Flateyensis''. It was commissioned by Jﺣﺏn Hﺣ۰konarson and produced by the priests and scribes ...

'', a 13th-century Iceland

Iceland ( is, ﺣsland; ) is a Nordic island country in the North Atlantic Ocean and in the Arctic Ocean. Iceland is the most sparsely populated country in Europe. Iceland's capital and largest city is Reykjavﺣk, which (along with its ...

ic source that says he was taught his soldiery by the chieftain Thorkell the Tall, brother to Sigurd

Sigurd ( non, Sigurﺣﺍr ) or Siegfried (Middle High German: ''Sﺣ؟vrit'') is a legendary hero of Germanic heroic legend, who killed a dragon and was later murdered. It is possible he was inspired by one or more figures from the Frankish Merovi ...

, Jarl of Jomsborg, and the legendary Jomsvikings

The Jomsvikings were purportedly a legendary order of Viking mercenaries or conquerors of the 10th and 11th centuries. Though reputed to be staunchly dedicated to the worship of the Old Norse gods, they would allegedly fight for any lord who ...

, at their stronghold on the island of Wollin, off the coast of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pﺣﺎmﺣﺎrskﺣﺑ''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to t ...

. His date of birth, like his mother's name, is unknown. Contemporary works such as the '' Chronicon'' and the ''Encomium Emmae

''Encomium Emmae Reginae'' or ''Gesta Cnutonis Regis'' is an 11th-century Latin encomium in honour of the English queen Emma of Normandy. It was written in 1041 or 1042, probably by a monk of Saint-Omer, Normandy.

Manuscripts

Until 2008, it w ...

'', do not mention this. Even so, in a '' Knﺣﭦtsdrﺣ۰pa'' by the skald

A skald, or skﺣ۰ld (Old Norse: , later ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry, the other being Eddic poetry, which is anonymous. Skaldic poems were traditionall ...

ﺣttarr svarti, there is a statement that Cnut was "of no great age" when he first went to war. It also mentions a battle identifiable with Sweyn Forkbeard's invasion of England and attack on the city of Norwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the Episcopal see, See of ...

, in 1003ﻗ04, after the St. Brice's Day massacre of Danes by the English, in 1002. If Cnut indeed accompanied this expedition, his birthdate may be near 990, or even 980. If not, and if the skald's poetic verse references another assault, such as Sweyn's conquest of England in 1013ﻗ14, it may even suggest a birth date nearer 1000. There is a passage of the Encomiast (as the author of the ''Encomium Emmae'' is known) with a reference to the force Cnut led in his English conquest of 1015ﻗ16. Here ( see below) it says all the Vikings were of "mature age" under Cnut "the king".

A description of Cnut appears in the 13th-century Icelandic ''Knﺣﺛtlinga saga

''Knﺣﺛtlinga saga'' (''The Saga of Cnut's Descendants'') is an Icelandic kings' saga written in the 1250s, which deals with the kings who ruled Denmark since the early 10th century.ﺣrmann Jakobsson, "Royal biography", p. 397-8

There are good rea ...

'':

Hardly anything is known for sure of Cnut's life until the year he was part of a Scandinavian force under his father, King Sweyn, in his invasion of England in summer 1013. Cnut was likely part of his father's 1003 and 1004 campaigns in England, although the evidence is not firm. The 1013 invasion was the climax to a succession of Viking

Vikings ; non, vﺣkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and s ...

raids spread over a number of decades. Following their landing in the Humber

The Humber is a large tidal estuary on the east coast of Northern England. It is formed at Trent Falls, Faxfleet, by the confluence of the tidal rivers Ouse and Trent. From there to the North Sea, it forms part of the boundary betw ...

,Ellis, ''Celt & Saxon'', p. 182. the kingdom fell to the Vikings quickly, and near the end of the year King ﺣthelred fled to Normandy

Normandy (; french: link=no, Normandie ; nrf, Normaundie, Nouormandie ; from Old French , plural of ''Normant'', originally from the word for "northman" in several Scandinavian languages) is a geographical and cultural region in Northwestern ...

, leaving Sweyn Forkbeard in possession of England. In the winter, Sweyn was in the process of consolidating his kingship, with Cnut left in charge of the fleet and the base of the army at Gainsborough in Lincolnshire

Lincolnshire (abbreviated Lincs.) is a county in the East Midlands of England, with a long coastline on the North Sea to the east. It borders Norfolk to the south-east, Cambridgeshire to the south, Rutland to the south-west, Leicestershir ...

.

On the death of Sweyn Forkbeard after a few months as king, on Candlemas

Candlemas (also spelled Candlemass), also known as the Feast of the Presentation of Jesus Christ, the Feast of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, or the Feast of the Holy Encounter, is a Christian holiday commemorating the presenta ...

(Sunday 3 February 1014),

Harald succeeded him as King of Denmark, while the Vikings and the people of the Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercia ...

immediately elected Cnut as king in England.Sawyer, ''History of the Vikings'', p. 171 However, the English nobility took a different view, and the Witenagemot

The Witan () was the king's council in Anglo-Saxon England from before the seventh century until the 11th century. It was composed of the leading magnates, both ecclesiastic and secular, and meetings of the council were sometimes called the Wi ...

recalled ﺣthelred from Normandy. The restored king swiftly led an army against Cnut, who fled with his army to Denmark, along the way mutilating the hostages they had taken and abandoning them on the beach at Sandwich

A sandwich is a food typically consisting of vegetables, sliced cheese or meat, placed on or between slices of bread, or more generally any dish wherein bread serves as a container or wrapper for another food type. The sandwich began as a po ...

in Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

. Cnut went to Harald and supposedly made the suggestion they might have a joint kingship, although this found no favour with his brother. Harald is thought to have offered Cnut command of his forces for another invasion of England, on the condition he did not continue to press his claim. In any case, Cnut succeeded in assembling a large fleet with which to launch another invasion.

Conquest of England

Bolesﺧaw I the Brave

Bolesﺧaw I the Brave ; cs, Boleslav Chrabrﺣﺛ; la, Boleslaus I rex Poloniae (17 June 1025), less often known as Bolesﺧaw the Great, was Duke of Poland from 992 to 1025, and the first King of Poland in 1025. He was also Duke of Bohemia bet ...

, the duke of Poland (later crowned king) and a relative to the Danish royal house. He lent some Polish troops, likely to have been a pledge made to Cnut and Harald Hardrada

Harald Sigurdsson (; ﻗ 25 September 1066), also known as Harald III of Norway and given the epithet ''Hardrada'' (; modern no, Hardrﺣ۴de, roughly translated as "stern counsel" or "hard ruler") in the sagas, was King of Norway from 1046 to ...

when, in the winter, they "went amongst the Wends

Wends ( ang, Winedas ; non, Vindar; german: Wenden , ; da, vendere; sv, vender; pl, Wendowie, cz, Wendovﺣ۸) is a historical name for Slavs living near Germanic settlement areas. It refers not to a homogeneous people, but to various peopl ...

" to fetch their mother back to the Danish court. She had been sent away by their father after the death of the Swedish king Eric the Victorious

Eric the Victorious (Old Norse: ''Eirﺣkr inn sigrsﺣ۵li'', Modern Swedish: ''Erik Segersﺣ۳ll''; c. 945 ﻗ c. 995) was a Swedish monarch as of around 970. Although there were earlier Swedish kings, he is the first Swedish king in a consecutive reg ...

in 995, and his marriage to Sigrid the Haughty

Sigrid the Haughty (Old Norse:''Sigrﺣﺣﺍr (hin) stﺣﺏrrﺣ۰ﺣﺍa''), also known as ''Sigrid Storrﺣ۴da'' (Swedish), is a Scandinavian queen appearing in Norse sagas. Sigrid is named in several late and sometimes contradictory Icelandic sagas composed g ...

, the Swedish queen mother

A queen mother is a former queen, often a queen dowager, who is the mother of the reigning monarch. The term has been used in English since the early 1560s. It arises in hereditary monarchies in Europe and is also used to describe a number of ...

. This wedlock formed a strong alliance between the successor to the throne of Sweden, Olof Skﺣﭘtkonung

Olof Skﺣﭘtkonung, (Old Norse: ''ﺣlﺣ۰fr skautkonungr'') sometimes stylized as ''Olaf the Swede'' (c. 980–1022), was King of Sweden, son of Eric the Victorious and, according to Icelandic sources, Sigrid the Haughty. He succeeded his father in ...

, and the rulers of Denmark, his in-laws. Swedes were certainly among the allies in the English conquest. Another in-law to the Danish royal house, Eirﺣkr Hﺣ۰konarson

Erik Hakonsson, also known as Eric of Hlathir or Eric of Norway, (, 960s ﻗ 1020s) was Earl of Lade, Governor of Norway and Earl of Northumbria. He was the son of Earl Hﺣ۰kon Sigurﺣﺍarson and brother of the legendary Aud Haakonsdottir of Lade. H ...

, was the earl of Lade

The Earls of Lade ( no, ladejarler) were a dynasty of Norse '' jarls'' from Lade ( Old Norse: ''Hlaﺣﺍir''), who ruled what is now Trﺣﺕndelag and Hﺣ۴logaland from the 9th century to the 11th century.

The seat of the Earls of Lade was at La ...

and the co-ruler of Norway with his brother Sweyn HaakonssonﻗNorway having been under Danish sovereignty since the Battle of Svolder

The Battle of Svolder (''Svold'' or ''Swold'') was a large naval battle during the Viking age, fought in September 999 or 1000 in the western Baltic Sea between King Olaf of Norway and an alliance of the Kings of Denmark and Sweden and Olaf's e ...

, in 999. Eirﺣkr's participation in the invasion left his son Hakon to rule Norway, with Sweyn.

In the summer of 1015, Cnut's fleet set sail for England with a Danish army of perhaps 10,000 in 200 longships. Cnut was at the head of an array of Vikings

Vikings ; non, vﺣkingr is the modern name given to seafaring people originally from Scandinavia (present-day Denmark, Norway and Sweden),

who from the late 8th to the late 11th centuries raided, pirated, traded and se ...

from all over Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sﺣ۰mi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

. The invading army was composed primarily of mercenaries. The invasion force was to engage in often close and grisly warfare with the English for the next fourteen months. Practically all of the battles were fought against the eldest son of ﺣthelred, Edmund Ironside

Edmund Ironside (30 November 1016; , ; sometimes also known as Edmund II) was King of the English from 23 April to 30 November 1016. He was the son of King ﺣthelred the Unready and his first wife, ﺣlfgifu of York. Edmund's reign was marred by ...

.

Landing in Wessex

According to the ''Peterborough Chronicle

The ''Peterborough Chronicle'' (also called the Laud manuscript and the E manuscript) is a version of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicles'' originally maintained by the monks of Peterborough Abbey in Cambridgeshire. It contains unique information ab ...

'' manuscript, one of the major witnesses of the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle

The ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'' is a collection of annals in Old English, chronicling the history of the Anglo-Saxons. The original manuscript of the ''Chronicle'' was created late in the 9th century, probably in Wessex, during the reign of A ...

'', early in September 1015 " nutcame into Sandwich, and straightway sailed around Kent to Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, until he came to the mouth of the Frome

Frome ( ) is a town and civil parish in eastern Somerset, England. The town is built on uneven high ground at the eastern end of the Mendip Hills, and centres on the River Frome. The town, about south of Bath, is the largest in the Mendip ...

, and harried in Dorset

Dorset ( ; archaically: Dorsetshire , ) is a county in South West England on the English Channel coast. The ceremonial county comprises the unitary authority areas of Bournemouth, Christchurch and Poole and Dorset. Covering an area of ...

and Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershir ...

and Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

", beginning a campaign of an intensity not seen since the days of Alfred the Great. A passage from Queen Emma's ''Encomium'' provides a picture of Cnut's fleet:

Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, long ruled by the dynasty of Alfred and ﺣthelred, submitted to Cnut late in 1015, as it had to his father two years earlier. At this point Eadric Streona, the Ealdorman of Mercia, deserted ﺣthelred together with 40 ships and their crews and joined forces with Cnut.G. Jones, ''Vikings'', p. 370 Another defector was Thorkell the Tall, a Jomsviking chief who had fought against the Viking invasion of Sweyn Forkbeard

Sweyn Forkbeard ( non, Sveinn Haraldsson tjﺣﭦguskegg ; da, Svend Tveskﺣ۵g; 17 April 963 ﻗ 3 February 1014) was King of Denmark from 986 to 1014, also at times King of the English and King of Norway. He was the father of King Harald II of ...

, with a pledge of allegiance to the English in 1012ﻗsome explanation for this shift of allegiance may be found in a stanza of the '' Jﺣﺏmsvﺣkinga saga'' that mentions two attacks against Jomsborg's mercenaries while they were in England, with a man known as Henninge, a brother of Thorkell, among their casualties.Trow, ''Cnut'', p. 57. If the ''Flateyjarbﺣﺏk

''Flateyjarbﺣﺏk'' (; "Book of Flatey") is an important medieval Icelandic manuscript. It is also known as GkS 1005 fol. and by the Latin name ''Codex Flateyensis''. It was commissioned by Jﺣﺏn Hﺣ۰konarson and produced by the priests and scribes ...

'' is correct that this man was Cnut's childhood mentor, it explains his acceptance of his allegianceﻗwith Jomvikings

The Jomsvikings were purportedly a legendary order of Viking mercenaries or conquerors of the 10th and 11th centuries. Though reputed to be staunchly dedicated to the worship of the Old Norse gods, they would allegedly fight for any lord who ...

ultimately in the service of Jomsborg. The 40 ships Eadric came with, often thought to be of the Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercia ...

, were probably Thorkell's.

Advance into the North

Early in 1016, the Vikings crossed theThames

The River Thames ( ), known alternatively in parts as the River Isis, is a river that flows through southern England including London. At , it is the longest river entirely in England and the second-longest in the United Kingdom, after the ...

and harried Warwickshire

Warwickshire (; abbreviated Warks) is a county in the West Midlands region of England. The county town is Warwick, and the largest town is Nuneaton. The county is famous for being the birthplace of William Shakespeare at Stratford-upon-Avon an ...

, while Edmund Ironside's attempts at opposition seem to have come to nothingﻗthe chronicler says the English army disbanded because the king and the citizenry of London were not present. The mid-winter assault by Cnut devastated its way northwards across eastern Mercia

la, Merciorum regnum

, conventional_long_name=Kingdom of Mercia

, common_name=Mercia

, status=Kingdom

, status_text=Independent kingdom (527ﻗ879)Client state of Wessex ()

, life_span=527ﻗ918

, era= Heptarchy

, event_start=

, date_start=

, ...

. Another summons of the army brought the Englishmen together, and they were met this time by the king, although "it came to nothing as so often before", and ﺣthelred returned to London with fears of betrayal. Edmund then went north to join Uhtred the Earl of Northumbria

Earl of Northumbria or Ealdorman of Northumbria was a title in the late Anglo-Saxon, Anglo-Scandinavian and early Anglo-Norman period in England. The ealdordom was a successor of the Norse Kingdom of York. In the seventh century, the Anglo-Saxo ...

and together they harried Staffordshire, Shropshire

Shropshire (; alternatively Salop; abbreviated in print only as Shrops; demonym Salopian ) is a landlocked historic county in the West Midlands region of England. It is bordered by Wales to the west and the English counties of Cheshire to ...

and Cheshire

Cheshire ( ) is a ceremonial and historic county in North West England, bordered by Wales to the west, Merseyside and Greater Manchester to the north, Derbyshire to the east, and Staffordshire and Shropshire to the south. Cheshire's coun ...

in western Mercia, possibly targeting the estates of Eadric Streona. Cnut's occupation of Northumbria

la, Regnum Northanhymbrorum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of Northumbria

, common_name = Northumbria

, status = State

, status_text = Unified Anglian kingdom (before 876)North: Anglian kingdom (af ...

meant Uhtred returned home to submit himself to Cnut, who seems to have sent a Northumbrian rival, Thurbrand the Hold, to massacre Uhtred and his retinue. Eirﺣkr Hﺣ۰konarson

Erik Hakonsson, also known as Eric of Hlathir or Eric of Norway, (, 960s ﻗ 1020s) was Earl of Lade, Governor of Norway and Earl of Northumbria. He was the son of Earl Hﺣ۰kon Sigurﺣﺍarson and brother of the legendary Aud Haakonsdottir of Lade. H ...

, most likely with another force of Scandinavians, came to support Cnut at this point, and the veteran Norwegian jarl was put in charge of Northumbria.

Prince Edmund remained in London, still unsubdued behind its walls, and was elected king after the death of ﺣthelred on 23 April 1016.

Siege of London

Cnut returned southward, and the Danish army evidently divided, some dealing with Edmund, who had broken out of London before Cnut's encirclement of the city was complete, and had gone to gather an army in

Cnut returned southward, and the Danish army evidently divided, some dealing with Edmund, who had broken out of London before Cnut's encirclement of the city was complete, and had gone to gather an army in Wessex

la, Regnum Occidentalium Saxonum

, conventional_long_name = Kingdom of the West Saxons

, common_name = Wessex

, image_map = Southern British Isles 9th century.svg

, map_caption = S ...

, the traditional heartland of the English monarchy. Part of the Danish army besieged London, constructing dikes on the northern and southern flanks and a channel dug across the banks of the Thames to the south of the city, enabling their longships to cut off communications up-river.

There was a battle fought at Penselwood in Somerset

( en, All The People of Somerset)

, locator_map =

, coordinates =

, region = South West England

, established_date = Ancient

, established_by =

, preceded_by =

, origin =

, lord_lieutenant_office =Lord Lieutenant of Somerset

, lor ...

ﻗ with a hill in Selwood Forest as the likely location ﻗ and a subsequent battle at Sherston, in Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershir ...

, which was fought over two days but left neither side victorious.

Edmund was able to temporarily relieve London, driving the enemy away and defeating them after crossing the Thames at Brentford

Brentford is a suburban town in West London, England and part of the London Borough of Hounslow. It lies at the confluence of the River Brent and the Thames, west of Charing Cross.

Its economy has diverse company headquarters buildings w ...

. Suffering heavy losses, he withdrew to Wessex to gather fresh troops, and the Danes again brought London under siege, but after another unsuccessful assault they withdrew into Kent under attack by the English, with a battle fought at Otford. At this point Eadric Streona went over to King Edmund, and Cnut set sail northwards across the Thames estuary to Essex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

, and went from the landing of the ships up the River Orwell

The River Orwell flows through the county of Suffolk in England from Ipswich to Felixstowe. Above Ipswich, the river is known as the River Gipping, but its name changes to the Orwell at Stoke Bridge, where the river becomes tidal. It broadens i ...

to ravage Mercia.

London captured by treaty

On 18 October 1016, the Danes were engaged by Edmund's army as they retired towards their ships, leading to the Battle of Assandun, fought at either Ashingdon, in south-east, or Ashdon, in north-westEssex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

. In the ensuing struggle, Eadric Streona, whose return to the English side had perhaps only been a ruse, withdrew his forces from the fray, bringing about a decisive English defeat. Edmund fled westwards, and Cnut pursued him into Gloucestershire

Gloucestershire ( abbreviated Glos) is a county in South West England. The county comprises part of the Cotswold Hills, part of the flat fertile valley of the River Severn and the entire Forest of Dean.

The county town is the city of Gl ...

, with another battle probably fought near the Forest of Dean

The Forest of Dean is a geographical, historical and cultural region in the western part of the county of Gloucestershire, England. It forms a roughly triangular plateau bounded by the River Wye to the west and northwest, Herefordshire to t ...

, for Edmund had an alliance with some of the Welsh.

On an island near Deerhurst, Cnut and Edmund, who had been wounded, met to negotiate terms of peace. It was agreed that all of England north of the Thames was to be the domain of the Danish prince, while all to the south was kept by the English king, along with London. Accession to the reign of the entire realm was set to pass to Cnut upon Edmund's death. Edmund died on 30 November, within weeks of the arrangement. Some sources claim Edmund was murdered, although the circumstances of his death are unknown. The West Saxons now accepted Cnut as king of all of England, and he was crowned by Lyfing, Archbishop of Canterbury, in London in 1017.

King of England

Cnut ruled

Cnut ruled England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

for nearly two decades. The protection he lent against Viking raidersﻗmany of them under his commandﻗrestored the prosperity that had been increasingly impaired since the resumption of Viking attacks in the 980s

The 980s decade ran from January 1, 980, to December 31, 989.

Significant people

* At-Ta'i

* Pope John XV

Pope John XV ( la, Ioannes XV; died on 1 April 996) was the bishop of Rome and ruler of the Papal States from August 985 until his dea ...

. In turn the English helped him to establish control over the majority of Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sﺣ۰mi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

, too. Under his rule, England did not experience serious external attacks.

Consolidation and Danegeld

As Danish King of England, Cnut was quick to eliminate any prospective challenge from the survivors of the mighty Wessex dynasty. The first year of his reign was marked by the executions of a number of English noblemen whom he considered suspect. ﺣthelred's son Eadwig ﺣtheling fled from England but was killed on Cnut's orders.''Anglo-Saxon Chronicles'', p. 154 Edmund Ironside's sons likewise fled abroad. ﺣthelred's sons byEmma of Normandy

Emma of Normandy (referred to as ﺣlfgifu in royal documents; c. 984 ﻗ 6 March 1052) was a Norman-born noblewoman who became the English, Danish, and Norwegian queen through her marriages to the Anglo-Saxon king ﺣthelred the Unready and th ...

went under the protection of their relatives in the Duchy of Normandy

The Duchy of Normandy grew out of the 911 Treaty of Saint-Clair-sur-Epte between King Charles III of West Francia and the Viking leader Rollo. The duchy was named for its inhabitants, the Normans.

From 1066 until 1204, as a result of the Nor ...

.

In July 1017, Cnut wed Queen Emma, the widow of ﺣthelred and daughter of Richard I, Duke of Normandy. In 1018, having collected a Danegeld

Danegeld (; "Danish tax", literally "Dane yield" or tribute) was a tax raised to pay tribute or protection money to the Viking raiders to save a land from being ravaged. It was called the ''geld'' or ''gafol'' in eleventh-century sources. I ...

amounting to the colossal sum of ﺡ۲72,000 levied nationwide, with an additional ﺡ۲10,500 extracted from London, Cnut paid off his army and sent most of them home. He retained 40 ships and their crews as a standing force in England. An annual tax called heregeld (army payment) was collected through the same system ﺣthelred had instituted in 1012 to reward Scandinavians in his service.

Cnut built on the existing English trend for multiple shires to be grouped together under a single ealdorman

Ealdorman (, ) was a term in Anglo-Saxon England which originally applied to a man of high status, including some of royal birth, whose authority was independent of the king. It evolved in meaning and in the eighth century was sometimes applied ...

, thusly dividing the country into four large administrative units whose geographical extent was based on the largest and most durable of the separate kingdoms that had preceded the unification of England. The officials responsible for these provinces were designated earl

Earl () is a rank of the nobility in the United Kingdom. The title originates in the Old English word ''eorl'', meaning "a man of noble birth or rank". The word is cognate with the Scandinavian form '' jarl'', and meant " chieftain", partic ...

s, a title of Scandinavian origin already in localised use in England, which now everywhere replaced that of ealdorman. Wessex was initially kept under Cnut's personal control, while Northumbria went to Erik of Hlathir, East Anglia

East Anglia is an area in the East of England, often defined as including the counties of Norfolk, Suffolk and Cambridgeshire. The name derives from the Anglo-Saxon kingdom of the East Angles, a people whose name originated in Anglia, in ...

to Thorkell the Tall, and Mercia remained in the hands of Eadric Streona.

This initial distribution of power was short-lived. The chronically treacherous Eadric was executed within a year of Cnut's accession. Mercia passed to one of the leading families of the region, probably first to Leofwine, ealdorman of the Hwicce

Hwicce () was a tribal kingdom in Anglo-Saxon England. According to the ''Anglo-Saxon Chronicle'', the kingdom was established in 577, after the Battle of Deorham. After 628, the kingdom became a client or sub-kingdom of Mercia as a result of t ...

under ﺣthelred, but certainly soon to his son Leofric. In 1021, Thorkel also fell from favour and was outlawed.

Following his death in the 1020s, Erik of Hlathir was succeeded as Earl of Northumbria by Siward, whose grandmother, Estrid (married to ﺣlfr Thorgilsson), was Cnut's sister. Bernicia

Bernicia ( ang, Bernice, Bryneich, Beornice; la, Bernicia) was an Anglo-Saxon kingdom established by Anglian settlers of the 6th century in what is now southeastern Scotland and North East England.

The Anglian territory of Bernicia was appr ...

, the northern part of Northumbria, was theoretically part of Erik and Siward's earldom, but throughout Cnut's reign it effectively remained under the control of the English dynasty based at Bamburgh, which had dominated the area at least since the early 10th century. They served as junior Earls of Bernicia under the titular authority of the Earl of Northumbria. By the 1030s Cnut's direct administration of Wessex had come to an end, with the establishment of an earldom under Godwin, an Englishman from a powerful Sussex family. In general, after initial reliance on his Scandinavian followers in the first years of his reign, Cnut allowed those Anglo-Saxon families of the existing English nobility who had earned his trust to assume rulership of his Earldoms.

Affairs to the East

At the

At the Battle of Nesjar

Battle of Nesjar (''Slaget ved Nesjar'') was a sea battle off the coast of Norway in 1016. It was a primary event in the reign of King Olav Haraldsson (later Saint Olav). Icelandic skald and court poet Sigvatr ﺣﺣﺏrﺣﺍarson composed the poem ' ...

, in 1016, Olaf Haraldsson won the kingdom of Norway from the Danes. It was at some time after Erik left for England, and on the death of Svein while retreating to Sweden, maybe intent on returning to Norway with reinforcements, that Erik's son Hakon went to join his father and support Cnut in England, too.

Cnut's brother Harald may have been at Cnut's coronation, in 1016, returning to Denmark as its king, with part of the fleet, at some point thereafter. It is only certain, though, that there was an entry of his name, alongside Cnut's, in confraternity with Christ Church, Canterbury

Canterbury Cathedral in Canterbury, Kent, is one of the oldest and most famous Christianity, Christian structures in England. It forms part of a World Heritage Site. It is the cathedral of the Archbishop of Canterbury, currently Justin Welby, le ...

, in 1018. This is not conclusive, though, for the entry may have been made in Harald's absence, perhaps by the hand of Cnut himself, which means that, while it is usually thought that Harald died in 1018, it is unsure whether he was still alive at this point. Entry of his brother's name in the Canterbury codex

The codex (plural codices ) was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term ''codex'' is often used for ancient manuscript books, with ...

may have been Cnut's attempt to make his vengeance for Harald's murder good with the Church. This may have been just a gesture for a soul to be under the protection of God. There is evidence Cnut was in battle with "pirates" in 1018, with his destruction of the crews of thirty ships, although it is unknown if this was off the English or Danish shores. He himself mentions troubles in his 1019 letter (to England, from Denmark), written as the King of England and Denmark. These events can be seen, with plausibility, to be in connection with the death of Harald. Cnut says he dealt with dissenters to ensure Denmark was free to assist England:

Statesmanship

Cnut was generally remembered as a wise and successful king of England, although this view may in part be attributable to his good treatment of the Church, keeper of the historic record. Accordingly, we hear of him, even today, as a religious man despite the fact that he was in an arguably sinful relationship, with two wives, and the harsh treatment he dealt his fellow Christian opponents.

Under his reign, Cnut brought together the English and Danish kingdoms, and the Scandinavic and Saxon peoples saw a period of dominance across

Cnut was generally remembered as a wise and successful king of England, although this view may in part be attributable to his good treatment of the Church, keeper of the historic record. Accordingly, we hear of him, even today, as a religious man despite the fact that he was in an arguably sinful relationship, with two wives, and the harsh treatment he dealt his fellow Christian opponents.

Under his reign, Cnut brought together the English and Danish kingdoms, and the Scandinavic and Saxon peoples saw a period of dominance across Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sﺣ۰mi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

, as well as within the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles (O ...

. His campaigns abroad meant the tables of Viking supremacy were stacked in favour of the English, turning the prows of the longships towards Scandinavia. He reinstated the Laws of King Edgar to allow for the constitution of a Danelaw

The Danelaw (, also known as the Danelagh; ang, Dena lagu; da, Danelagen) was the part of England in which the laws of the Danes held sway and dominated those of the Anglo-Saxons. The Danelaw contrasts with the West Saxon law and the Mercia ...

, and for the activity of Scandinavians at large.

Cnut reinstituted the extant laws with a series of proclamations to assuage common grievances brought to his attention, including: ''On Inheritance

Inheritance is the practice of receiving private property, titles, debts, entitlements, privileges, rights, and obligations upon the death of an individual. The rules of inheritance differ among societies and have changed over time. Offici ...

in case of Intestacy

Intestacy is the condition of the estate of a person who dies without having in force a valid will or other binding declaration. Alternatively this may also apply where a will or declaration has been made, but only applies to part of the estat ...

'', and ''On Heriot

Heriot, from Old English ''heregeat'' ("war-gear"), was originally a death-duty in late Anglo-Saxon England, which required that at death, a nobleman provided to his king a given set of military equipment, often including horses, swords, shield ...

s and Reliefs''. He also strengthened the currency, initiating a series of coins of equal weight to those being used in Denmark and other parts of Scandinavia. He issued the Law codes of Cnut known now as I Cnut and II Cnut, though these seem primarily to have been produced by Wulfstan of York.

In his royal court, there were both Englishmen and Scandinavians.

King of Denmark

Harald II died in 1018, and Cnut went to Denmark to affirm his succession to the Danish crown, stating his intention to avert attacks against England in a letter in 1019 ( see above). It seems there were Danes in opposition to him, and an attack he carried out on theWends

Wends ( ang, Winedas ; non, Vindar; german: Wenden , ; da, vendere; sv, vender; pl, Wendowie, cz, Wendovﺣ۸) is a historical name for Slavs living near Germanic settlement areas. It refers not to a homogeneous people, but to various peopl ...

of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pﺣﺎmﺣﺎrskﺣﺑ''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to t ...

may have had something to do with this. In this expedition, at least one of Cnut's Englishmen, Godwin, apparently won the king's trust after a night-time raid he personally led against a Wendish encampment.

His hold on the Danish throne presumably stable, Cnut was back in England in 1020. He appointed Ulf Jarl, the husband of his sister Estrid Svendsdatter, as regent of Denmark, further entrusting him with his young son by Queen Emma, Harthacnut

Harthacnut ( da, Hardeknud; "Tough-knot"; ﻗ 8 June 1042), traditionally Hardicanute, sometimes referred to as Canute III, was King of Denmark from 1035 to 1042 and King of the English from 1040 to 1042.

Harthacnut was the son of King ...

, whom he had designated the heir of his kingdom. The banishment of Thorkell the Tall in 1021 may be seen in relation to the attack on the Wends. With the death of Olof Skﺣﭘtkonung

Olof Skﺣﭘtkonung, (Old Norse: ''ﺣlﺣ۰fr skautkonungr'') sometimes stylized as ''Olaf the Swede'' (c. 980–1022), was King of Sweden, son of Eric the Victorious and, according to Icelandic sources, Sigrid the Haughty. He succeeded his father in ...

in 1022, and the succession to the Swedish throne of his son Anund Jacob

Anund Jacob or James, Swedish: ''Anund Jakob'' was King of Sweden from 1022 until around 1050. He is believed to have been born on July 25, in either 1008 or 1010 as ''Jakob'', the son of King Olof Skﺣﭘtkonung and Queen Estrid. Being the second ...

bringing Sweden into alliance with Norway, there was cause for a demonstration of Danish strength in the Baltic. Jomsborg, the legendary stronghold of the Jomsvikings (thought to be on an island off the coast of Pomerania

Pomerania ( pl, Pomorze; german: Pommern; Kashubian: ''Pﺣﺎmﺣﺎrskﺣﺑ''; sv, Pommern) is a historical region on the southern shore of the Baltic Sea in Central Europe, split between Poland and Germany. The western part of Pomerania belongs to t ...

), was probably the target of Cnut's expedition. Successful, after this clear display of Cnut's intentions to dominate Scandinavian affairs, it seems that Thorkell reconciled with Cnut in 1023.

When, in spite of this, the Norwegian king Olaf Haraldsson and Anund Jakob took advantage of Cnut's commitment to England and began to launch attacks against Denmark, Ulf gave the Danish freemen cause to accept Harthacnut, still a child, as king. This was a ruse on Ulf's part since his role as caretaker of Harthacnut gave him the reign of the kingdom. Upon news of these events, Cnut set sail for Denmark to restore himself and to deal with Ulf, who then got back in line. In a battle known as the Battle of the Helgeﺣ۴, Cnut and his men fought the Norwegians and Swedes at the mouth of the river Helgeﺣ۴, probably in 1026, and the apparent victory left Cnut as the dominant leader in Scandinavia. Ulf the usurper's realignment and participation in the battle did not, in the end, earn him Cnut's forgiveness. Some sources state that the brothers-in-law were playing chess

Chess is a board game for two players, called White and Black, each controlling an army of chess pieces in their color, with the objective to checkmate the opponent's king. It is sometimes called international chess or Western chess to dist ...

at a banquet in Roskilde

Roskilde ( , ) is a city west of Copenhagen on the Danish island of Zealand. With a population of 51,916 (), the city is a business and educational centre for the region and the 10th largest city in Denmark. It is governed by the administrative ...

when an argument arose between them, and the next day, Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating the birth of Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people around the world. A feast central to the Christian liturgical year ...

1026, one of Cnut's housecarls killed the jarl with his blessing, in Trinity Church, the predecessor to Roskilde Cathedral

, image = Roskilde Cathedral aerial.jpg

, caption = View from the north-west

, coordinates =

, location = Roskilde

, country = Denmark

, denomination = Church of Denmark

, previous denomination = Catholic Church

, website =

, founded da ...

.

Journey to Rome

His enemies in Scandinavia subdued, and apparently at his leisure, Cnut was able to accept an invitation to witness the accession in

His enemies in Scandinavia subdued, and apparently at his leisure, Cnut was able to accept an invitation to witness the accession in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

of the Holy Roman Emperor Conrad II. He left his affairs in the north and went from Denmark to the coronation at Easter 1027, which would have been of considerable prestige for rulers of Europe in the Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire ...

. On the return journey he wrote his letter of 1027, like his letter of 1019, informing his subjects in England of his intentions from abroad and proclaiming himself "king of all England and Denmark and the Norwegians and of some of the Swedes".

Consistent with his role as a Christian king, Cnut says he went to Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus ( legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

to repent for his sins, to pray for redemption and the security of his subjects, and to negotiate with the Pope for a reduction in the costs of the pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropoli ...

for English archbishops, and for a resolution to the competition between the archdioceses of Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour.

The Archbishop of Canterbury is the primate of ...

and Prince-Archbishopric of Bremen, Hamburg-Bremen for superiority over the Danish dioceses. He also sought to improve the conditions for pilgrims, as well as merchants, on the road to Rome. In his own words:

"Robert" in Cnut's text is probably a clerical error for Rudolph III of Burgundy, Rudolph, the last ruler of an independent Kingdom of Burgundy. Hence, the solemn word of the Pope, the Emperor and Rudolph was given with the witness of four archbishops, twenty bishops, and "innumerable multitudes of dukes and nobles",Trow, ''Cnut'', p. 193. suggesting it was before the ceremonies were completed. Cnut without doubt threw himself into his role with zest. His image as a just Christian king, statesman and diplomat and crusader against unjustness, seems rooted in reality, as well as one he sought to project.

A good illustration of his status within Europe is the fact that Cnut and the List of kings of Burgundy, King of Burgundy went alongside the emperor in the imperial procession and stood shoulder-to-shoulder with him on the same pedestal.Trow, ''Cnut'', p. 189. Cnut and the emperor, in accord with various sources, took to one another's company like brothers, for they were of a similar age. Conrad gave Cnut lands in the March (territory), Mark of Duchy of Schleswig, Schleswigﻗthe land-bridge between the Scandinavian kingdoms and the continentﻗas a token of their treaty of friendship. Centuries of conflict in this area between the Danes and the Germans led to construction of the Danevirke, from Schleswig, on the Schlei, an inlet of the Baltic Sea, to the North Sea.

Cnut's visit to Rome was a triumph. In the verse of ''Knﺣﭦtsdrﺣ۰pa'', Sigvatr ﺣﺣﺏrﺣﺍarson praises Cnut, his king, as being "dear to the Emperor, close to Peter".Trow, ''Cnut'', p. 191. In the days of Christendom, a king seen to be in favour with God could expect to be ruler over a happy kingdom. He was surely in a stronger position, not only with the Church and the people, but also in the alliance with his southern rivals he was able to conclude his conflicts with his rivals in the north. His letter not only tells his countrymen of his achievements in Rome, but also of his ambitions within the Scandinavian world at his arrival home:

Cnut was to return to Denmark from Rome, arrange for its security, and afterwards sail to England.

King of Norway and part of Sweden

Scandinavia

Scandinavia; Sﺣ۰mi languages: /. ( ) is a subregion in Northern Europe, with strong historical, cultural, and linguistic ties between its constituent peoples. In English usage, ''Scandinavia'' most commonly refers to Denmark, Norway, and Swe ...

, which fits the account of John of Worcester that in 1027 Cnut heard some Norwegians were discontented and sent them sums of gold and silver to gain their support for his claim to the throne.

In 1028, Cnut set off from England to Norway, and the city of Trondheim

Trondheim ( , , ; sma, Trﺣ۴ante), historically Kaupangen, Nidaros and Trondhjem (), is a city and municipality in Trﺣﺕndelag county, Norway. As of 2020, it had a population of 205,332, was the third most populous municipality in Norway, an ...

, with a fleet of fifty ships. King Olaf Haraldsson was unable to put up a serious fight, both as his nobles had been bribed by Cnut and (according to Adam of Bremen) because he tended to apprehend their wives for sorcery. Cnut was crowned king, now of England, Denmark and Norway as well as part of Sweden. He entrusted the Earldom of Lade, Trondheim, Lade to the former line of earls, in Haakon Ericsson, Hﺣ۴kon Eiriksson, with Eirﺣkr Hﺣ۰konarson probably dead by this time. Hakon was possibly the Earl of Northumbria after Erik as well.

Hakon, a member of a family with a long tradition of hostility towards the independent Norwegian kings, and a relative of Cnut's, was already in lordship over the Isles with the earldom of Worcester, England, Worcester, possibly from 1016 to 1017. The sea-lanes through the Irish Sea and the Hebrides led to Orkney and Norway, and were central to Cnut's ambitions for dominance of Scandinavia and the British Isles

The British Isles are a group of islands in the North Atlantic Ocean off the north-western coast of continental Europe, consisting of the islands of Great Britain, Ireland, the Isle of Man, the Inner and Outer Hebrides, the Northern Isles (O ...

. Hakon was meant to be Cnut's lieutenant in this strategic chain, and the final component was his installation as the king's deputy in Norway, after the expulsion of Olaf Haraldsson in 1028. Unfortunately, he was drowned in a shipwreck in the Pentland Firth (between the Orkney Islands and the mainland coast) either late 1029 or early 1030.

Upon the death of Hakon, Olaf Haraldsson returned to Norway, with Swedes in his army. He died at the hands of his own people, at the Battle of Stiklestad in 1030. Cnut's subsequent attempt to rule Norway without the key support of the Earls of Lade, Trondejarls, through ﺣlfgifu of Northampton, and his eldest son by her, Svein Knutsson, Sweyn Knutsson, was not a success. The period is known as ''Aelfgifu's Time'' in Norway, with heavy taxation, a rebellion, and the restoration of the former Norwegian dynasty under Saint Olaf's illegitimate son Magnus the Good.

Influence in the western sea-ways

In 1014, while Cnut was preparing his re-invasion of England, the Battle of Clontarf pitted an array of armies laid out on the fields before the walls of Dublin. Mﺣ۰el Mﺣﺏrda mac Murchada, king of Leinster, and Sigtrygg Silkbeard, ruler of the Norse-Gaelic kingdom of Dublin, had sent out emissaries to all the Viking kingdoms to request assistance in their rebellion against Brian Boru, Brian Bﺣﺏruma, the High King of Ireland. Sigurd the Stout, the Earl of Orkney, was offered command of all the Norse forces, while the High King had sought assistance from the Albannaich, who were led by Domnall mac Eimﺣn, Domnall mac Eimﺣn meic Cainnig, the Earl of Mar, Mormaer of Mar. The Leinster-Norse alliance was defeated, and both commanders, Sigurd and Mﺣ۰el Mﺣﺏrda, were killed. Brian, his son, his grandson, and the Mormaer Domhnall were slain as well. Sigtrygg's alliance was broken, although he was left alive, and the high-kingship of Ireland went back to the Uﺣ Nﺣ۸ill, again under Mﺣ۰el Sechnaill mac Domnaill. There was a brief period of freedom in the Irish Sea zone for the Vikings of Dublin, with a political vacuum felt throughout the entire Western Maritime Zone of the North Atlantic Archipelago. Prominent among those who stood to fill the void was Cnut, "whose leadership of the Scandinavian world gave him a unique influence over the western colonies and whose control of their commercial arteries gave an economic edge to political domination". Coinage struck by the king in Dublin, Silkbeard, bearing Cnut's quatrefoil typeﻗin issue c. 1017ﻗ25ﻗsporadically replacing the legend with one bearing his own name and styling him as ruler either 'of Dublin' or 'among the Irish' provides evidence of Cnut's influence. Further evidence is the entry of one ''Sihtric dux'' in three of Cnut's charters. In one of his verses, Cnut's court poet Sigvatr ﺣﺣﺏrﺣﺍarson recounts that famous princes brought their heads to Cnut and bought peace. This verse mentions Olaf Haraldsson in the past tense, his death at the Battle of Stiklestad having occurred in 1030. It was therefore at some point after this and the consolidation of Norway that Cnut went to Scotland with an army, and the navy in the Irish Sea, in 1031, to receive, without bloodshed, the submission of three Scottish kings: Malcolm II of Scotland#Cnut, Maelcolm, the future King Macbeth, King of Scotland, Maelbeth and Iehmarc. One of these kings, Iehmarc, may be one Echmarcach mac Ragnaill, an Uﺣ ﺣmair chieftain and the ruler of a sea-kingdom of the Irish Sea, with Galloway among his domains. Nevertheless, it appears that Malcolm adhered to little of Cnut's power, and that influence over Scotland died out by the time of Cnut's death. Further, a ''Lausavﺣsa'' attributable to theskald

A skald, or skﺣ۰ld (Old Norse: , later ; , meaning "poet"), is one of the often named poets who composed skaldic poetry, one of the two kinds of Old Norse poetry, the other being Eddic poetry, which is anonymous. Skaldic poems were traditionall ...

ﺣttarr svarti greets the ruler of the Danes, Irish, English and Island-dwellersﻗuse of ''Irish'' here being likely to mean the NorseﻗGaels, Gall Ghaedil kingdoms rather than the Gaels, Gaelic kingdoms. It "brings to mind Sweyn Forkbeard's putative activities in the Irish Sea and Adam of Bremen's story of his stay with a ''rex Scothorum'' (? king of the Irish) [&] can also be linked to... Iehmarc, who submitted in 1031 [&] could be relevant to Cnut's relations with the Irish".

Relations with the Church

Cnut's actions as a conqueror and his ruthless treatment of the overthrown dynasty had made him uneasy with the Church. He was already a Christian before he was kingﻗbeing named ''Lambert'' at his baptismAdam of Bremen, ''Gesta Daenorum'', scholium 37, p. 112.ﻗalthough the Christianization of Scandinavia was not at all complete. His marriage to

Cnut's actions as a conqueror and his ruthless treatment of the overthrown dynasty had made him uneasy with the Church. He was already a Christian before he was kingﻗbeing named ''Lambert'' at his baptismAdam of Bremen, ''Gesta Daenorum'', scholium 37, p. 112.ﻗalthough the Christianization of Scandinavia was not at all complete. His marriage to Emma of Normandy

Emma of Normandy (referred to as ﺣlfgifu in royal documents; c. 984 ﻗ 6 March 1052) was a Norman-born noblewoman who became the English, Danish, and Norwegian queen through her marriages to the Anglo-Saxon king ﺣthelred the Unready and th ...

, even though he was already married to ﺣlfgifu of Northampton, who was kept in the south with an estate in Exeter, was another conflict with Church teaching. In an effort to reconcile himself with his churchmen, Cnut repaired all the English churches and monasteries that were victims of Viking plunder and refilled their coffers. He also built new churches and was an earnest patron of monastic communities. His homeland of Denmark was a Christian nation on the rise, and the desire to enhance the religion was still fresh. As an example, the first stone church recorded to have been built in Scandinavia was in Roskilde

Roskilde ( , ) is a city west of Copenhagen on the Danish island of Zealand. With a population of 51,916 (), the city is a business and educational centre for the region and the 10th largest city in Denmark. It is governed by the administrative ...

, c. 1027, and its patron was Cnut's sister Estrid.

It is difficult to ascertain whether Cnut's attitude towards the Church derived from deep religious devotion or was merely a means to reinforce his regime's hold on the people. There is evidence of respect for the pagan religion in his praise poetry, which he was happy enough for his ''skalds'' to embellish in Norse mythology, while other Viking leaders were insistent on the rigid observation of the Christian line, like Olaf II of Norway, St Olaf. Yet he also displays the desire for a respectable Christian nationhood within Europe. In 1018, some sources suggest he was at Canterbury on the return of its Archbishop Lyfing (Archbishop of Canterbury), Lyfing from Rome, to receive letters of exhortation from the Pope. If this chronology is correct, he probably went from Canterbury to the Witan at Oxford, with Archbishop Wulfstan (died 1023), Wulfstan of York in attendance, to record the event.

His ecumenical gifts were widespread and often exuberant. Commonly held land was given, along with exemption from taxes as well as relics. Canterbury Cathedral, Christ Church was probably given rights at the important port of Sandwich as well as tax exemption, with confirmation in the placement of their charters on the altar, while it got the relics of ﺣlfheah of Canterbury, St ﺣlfheah, at the displeasure of the people of London. Another see in the king's favour was Winchester, second only to the Canterbury see in terms of wealth. New Minster, Winchester, New Minster's ''Confraternity book, liber vitae'' records Cnut as a benefactor of the monastery, and the Winchester Cross, with 500 marks of silver and 30 marks of gold, as well as relics of various saints was given to it. Old Minster, Winchester, Old Minster was the recipient of a shrine for the relics of Birinus, St Birinus and the probable confirmation of its privileges. The monastery at Evesham, with its Abbot ﺣlfweard purportedly a relative of the king through ﺣlfgifu the Lady (probably ﺣlfgifu of Northampton, rather than Queen Emma, also known as ﺣlfgifu), got the relics of Wigstan, St Wigstan. Such generosity towards his subjects, which his skalds called "destroying treasure", was popular with the English. Yet it is important to remember that not all Englishmen were in his favour, and the burden of taxation was widely felt. His attitude towards London's see was clearly not benign. The monasteries at Ely, Cambridgeshire, Ely and Glastonbury were apparently not on good terms either.

Other gifts were also given to his neighbours. Among these was one to Chartres, of which its bishop wrote: "When we saw the gift that you sent us, we were amazed at your knowledge as well as your faith ... since you, whom we had heard to be a pagan prince, we now know to be not only a Christian, but also a most generous donor to God's churches and servants". He is known to have sent a psalter and sacramentary made in Peterborough (famous for its Illuminated manuscript, illustrations) to Cologne, and a book written in gold, among other gifts, to William V, Duke of Aquitaine, William the Great of Aquitaine. This golden book was apparently to support Aquitanian claims of Saint Martial, St Martial, patron saint of Aquitaine, as an Apostles, apostle. Of some consequence, its recipient was an avid artisan, Scholarly method, scholar and devout Christian, and the Abbey of Saint Martial, Limoges, Abbey of Saint-Martial was a great library and scriptorium, second only to the one at Cluny. It is likely that Cnut's gifts were well beyond anything we can now know.

Cnut's journey to Rome in 1027 is another sign of his dedication to the Christian religion. It may be that he went to attend the coronation of Conrad II in order to improve relations between the two powers, yet he had previously made a vow to seek the favour of St Peter, the keeper of the keys to the heavenly kingdom. While in Rome, Cnut made an agreement with the Pope to reduce the fees paid by the English archbishops to receive their pallium

The pallium (derived from the Roman ''pallium'' or ''palla'', a woolen cloak; : ''pallia'') is an ecclesiastical vestment in the Catholic Church, originally peculiar to the pope, but for many centuries bestowed by the Holy See upon metropoli ...

. He also arranged that travellers from his realm not be straitened by unjust tolls and that they should be safeguarded on their way to and from Rome. Some evidence exists for a second journey in 1030.

Death and succession

Cnut died on 12 November 1035. In Denmark he was succeeded byHarthacnut

Harthacnut ( da, Hardeknud; "Tough-knot"; ﻗ 8 June 1042), traditionally Hardicanute, sometimes referred to as Canute III, was King of Denmark from 1035 to 1042 and King of the English from 1040 to 1042.

Harthacnut was the son of King ...