Kenneth Robert Livingstone (born 17 June 1945) is an English politician who served as the Leader of the

Greater London Council (GLC) from 1981 until the council was

abolished in 1986, and as

Mayor of London

The mayor of London is the chief executive of the Greater London Authority. The role was created in 2000 after the Greater London devolution referendum in 1998, and was the first directly elected mayor in the United Kingdom.

The current m ...

from the

creation of the office in 2000 until

2008

File:2008 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Lehman Brothers went bankrupt following the Subprime mortgage crisis; Cyclone Nargis killed more than 138,000 in Myanmar; A scene from the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing; ...

. He also served as the Member of Parliament (MP) for

Brent East from

1987

File:1987 Events Collage.png, From top left, clockwise: The MS Herald of Free Enterprise capsizes after leaving the Port of Zeebrugge in Belgium, killing 193; Northwest Airlines Flight 255 crashes after takeoff from Detroit Metropolitan Airport, ...

to

2001. A former member of the

Labour Party, he was on the party's

hard left

In the United Kingdom, the hard left are the left-wing political movements and ideas outside the mainstream centre-left.*

*

Term

The term was first used in the context of debates within both the Labour Party and the broader left in the 1980 ...

, ideologically identifying as a

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

.

Born in

Lambeth,

South London, to a working-class family, Livingstone joined Labour in 1968 and was elected to represent

Norwood at the GLC in

1973

Events January

* January 1 - The United Kingdom, the Republic of Ireland and Denmark 1973 enlargement of the European Communities, enter the European Economic Community, which later becomes the European Union.

* January 15 – Vietnam War: ...

,

Hackney North and Stoke Newington

Hackney North and Stoke Newington is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom since 1987 by Diane Abbott of the Labour Party, who served as Shadow Home Secretary from 6 October 2016 to 5 April 2020. Abbott was o ...

in

1977

Events January

* January 8 – Three bombs explode in Moscow within 37 minutes, killing seven. The bombings are attributed to an Armenian separatist group.

* January 10 – Mount Nyiragongo erupts in eastern Zaire (now the Democrat ...

, and

Paddington

Paddington is an area within the City of Westminster, in Central London. First a medieval parish then a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Three important landmarks of the district are Padd ...

in

1981

Events January

* January 1

** Greece enters the European Economic Community, predecessor of the European Union.

** Palau becomes a self-governing territory.

* January 10 – Salvadoran Civil War: The FMLN launches its first major offensiv ...

. That year, Labour representatives on the GLC elected him as the council's leader. Attempting to

reduce London Underground fares, his plans were challenged in court and declared unlawful; more successful were his schemes to benefit women and several minority groups, despite stiff opposition. The mainstream press gave him the moniker "Red Ken" in reference to his socialist beliefs and criticised him for supporting

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

,

LGBT rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender ( LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, ...

, and a

United Ireland

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

. Livingstone was a vocal opponent of the

Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

government of Prime Minister

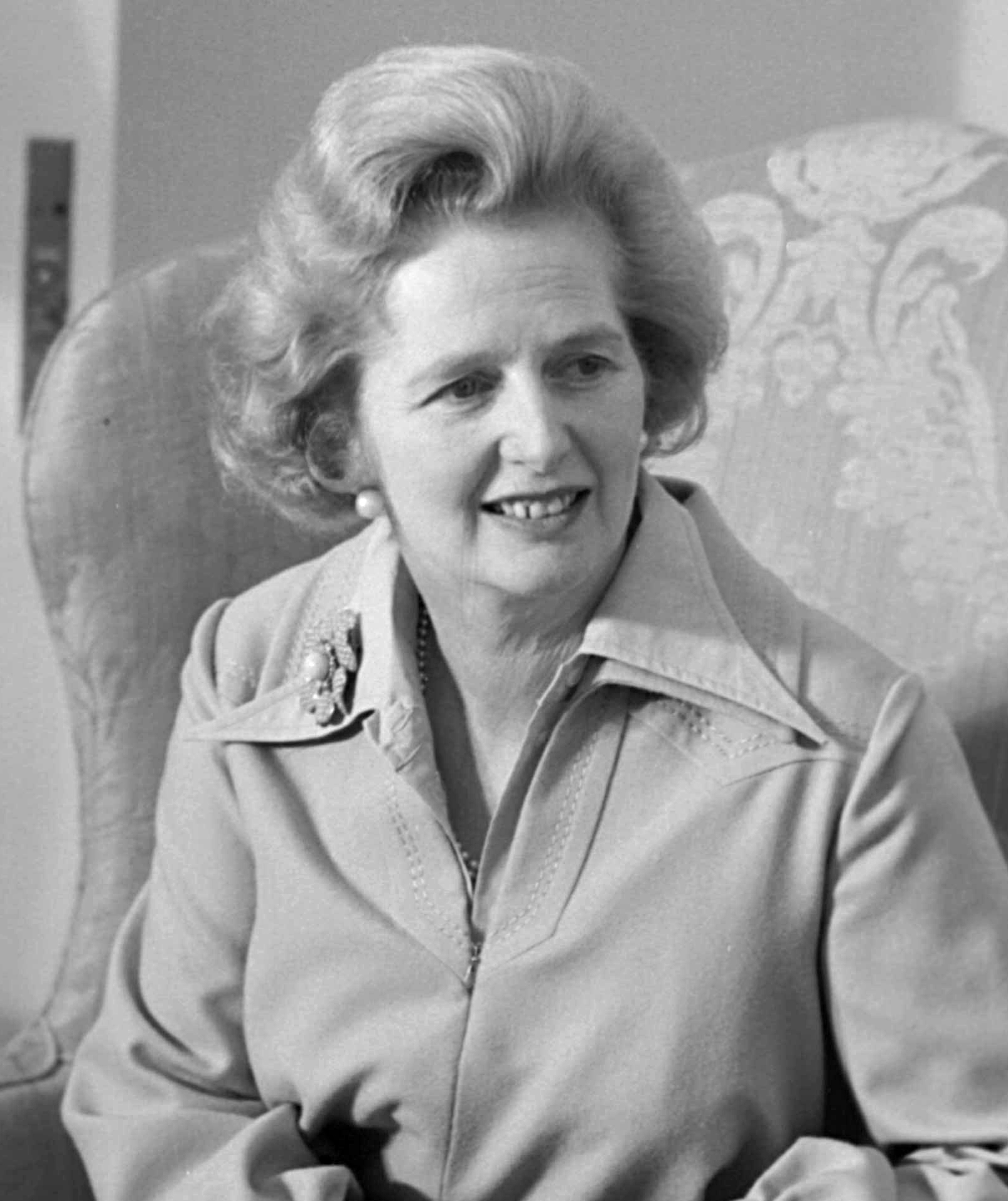

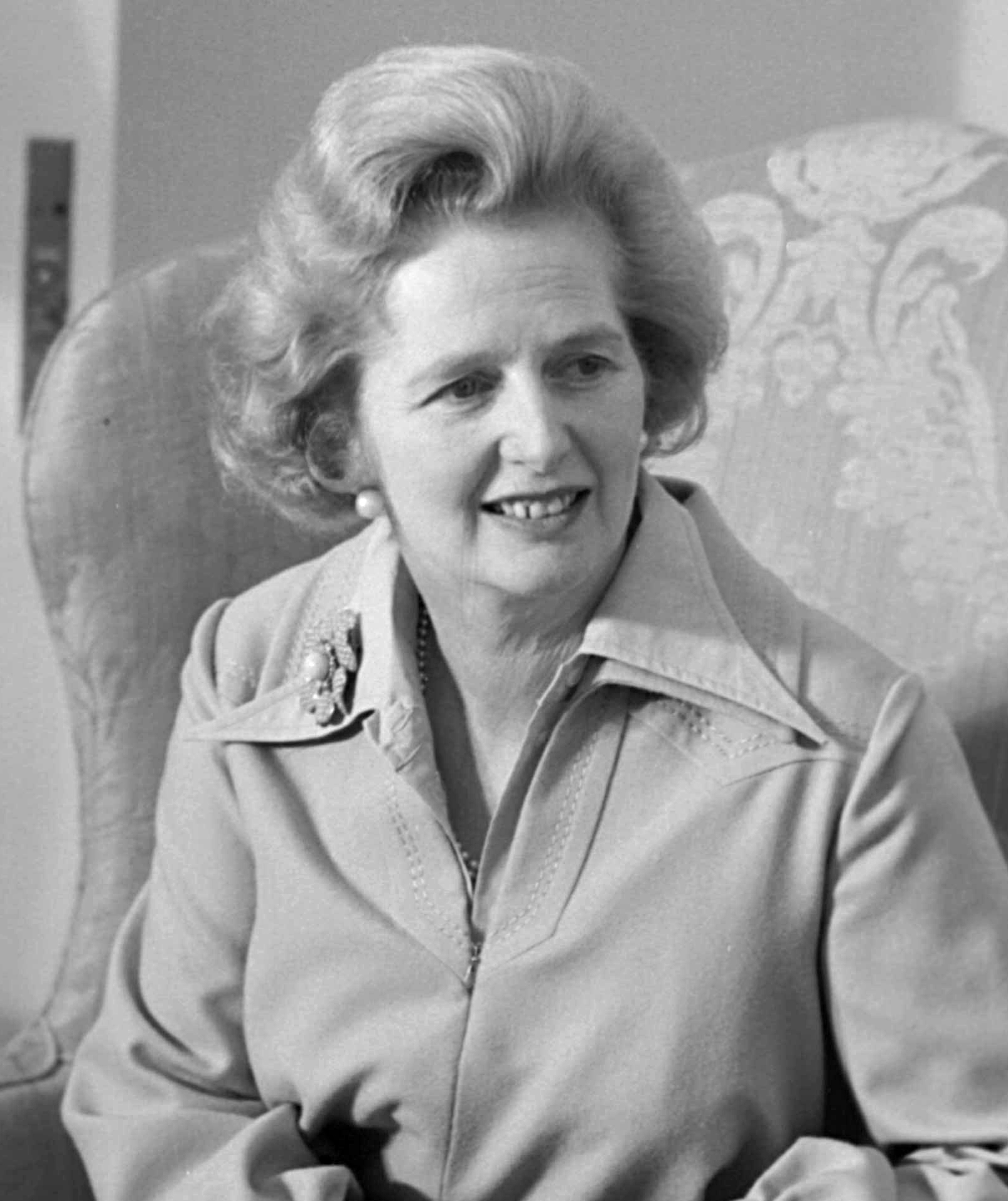

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

, which in 1986 abolished the GLC. Elected as MP for Brent East in 1987, he became closely associated with

anti-racist

Anti-racism encompasses a range of ideas and political actions which are meant to counter racial prejudice, systemic racism, and the oppression of specific racial groups. Anti-racism is usually structured around conscious efforts and deliberate ...

campaigns. He attempted to stand for the position of

Labour Party leader following

Neil Kinnock

Neil Gordon Kinnock, Baron Kinnock (born 28 March 1942) is a British former politician. As a member of the Labour Party, he served as a Member of Parliament from 1970 until 1995, first for Bedwellty and then for Islwyn. He was the Leader of ...

's resignation in

1992, but failed to get enough nominations. Livingstone became a vocal critic of

Tony Blair

Sir Anthony Charles Lynton Blair (born 6 May 1953) is a British former politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1997 to 2007 and Leader of the Labour Party from 1994 to 2007. He previously served as Leader of th ...

's

New Labour

New Labour was a period in the history of the British Labour Party from the mid to late 1990s until 2010 under the leadership of Tony Blair and Gordon Brown. The name dates from a conference slogan first used by the party in 1994, later seen ...

project that pushed the party closer to the

political centre

Centrism is a political outlook or position involving acceptance or support of a balance of social equality and a degree of social hierarchy while opposing political changes that would result in a significant shift of society strongly to the ...

and won the

1997 general election.

After failing to become Labour's candidate in the

2000 London mayoral election

The 2000 London mayoral election was held on 4 May 2000 to elect the Mayor of London. It was the first election to the office established that year, after a referendum in London.

Electoral system

The election used a supplementary vote system ...

, Livingstone successfully contested the election as an

independent candidate. In his first term as Mayor of London, he introduced the

congestion charge,

Oyster card

The Oyster card is a payment method for public transport in London (and certain areas around it) in England, United Kingdom. A standard Oyster card is a blue credit-card-sized stored-value contactless smart card. It is promoted by Transport ...

, and

articulated buses, and unsuccessfully opposed the privatisation of

London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The ...

. Despite his opposition to Blair's government on issues like the

Iraq War

{{Infobox military conflict

, conflict = Iraq War {{Nobold, {{lang, ar, حرب العراق (Arabic) {{Nobold, {{lang, ku, شەڕی عێراق ( Kurdish)

, partof = the Iraq conflict and the War on terror

, image ...

, Livingstone was invited to stand for re-election as Labour's candidate.

Re-elected in 2004, he expanded his transport policies, introduced new environmental regulations, and enacted civil rights reforms. Overseeing London's winning bid to host the

2012 Summer Olympics and ushering in a major redevelopment of the city's

East End, his leadership after the

7 July 2005 London bombings

The 7 July 2005 London bombings, often referred to as 7/7, were a series of four coordinated suicide attacks carried out by Islamic terrorists in London that targeted commuters travelling on the city's public transport system during the mo ...

was widely praised. After losing both the

2008

File:2008 Events Collage.png, From left, clockwise: Lehman Brothers went bankrupt following the Subprime mortgage crisis; Cyclone Nargis killed more than 138,000 in Myanmar; A scene from the opening ceremony of the 2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing; ...

and

2012

File:2012 Events Collage V3.png, From left, clockwise: The passenger cruise ship Costa Concordia lies capsized after the Costa Concordia disaster; Damage to Casino Pier in Seaside Heights, New Jersey as a result of Hurricane Sandy; People gat ...

London mayoral elections to the Conservative candidate

Boris Johnson

Alexander Boris de Pfeffel Johnson (; born 19 June 1964) is a British politician, writer and journalist who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom and Leader of the Conservative Party from 2019 to 2022. He previously served as F ...

, Livingstone became a key ally of Labour leader

Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the political left of the Labour Party, Corbyn describes himself as a socialist ...

in 2015. A longstanding critic of

Israeli policy regarding Palestinians, his comments about the relationship between

Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and

Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

resulted in his 2016 suspension from Labour, after which he resigned from the party in 2018.

Characterised by

Charles Moore as "the only truly successful left-wing British politician of modern times", Livingstone was a controversial and polarising figure. Supporters praised his efforts to improve rights for women, LGBT people, and ethnic minorities in London, but critics emphasised allegations of

cronyism

Cronyism is the spoils system practice of Impartiality, partiality in awarding jobs and other advantages to friends or trusted colleagues, especially in politics and between politicians and supportive organizations. For example, cronyism occurs ...

and

antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, and criticised him for his connections to

Islamists

Islamism (also often called political Islam or Islamic fundamentalism) is a political ideology which posits that modern states and regions should be reconstituted in constitutional, economic and judicial terms, in accordance with what is c ...

,

Marxists, and

Irish republicans.

Early life

Childhood and young adulthood: 1945–1967

Livingstone was born in his grandmother's house at 21 Shrubbery Road

Streatham,

South London, on 17 June 1945. His family was working class; his mother, Ethel Ada (née Kennard, 1915–1997), had been born in

Southwark before training as an

acrobatic dancer and working on the

music hall circuit prior to the

Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

. Ken's Scottish father, Robert "Bob" Moffat Livingstone (1915–1971), had been born in

Dunoon

Dunoon (; gd, Dùn Omhain) is the main town on the Cowal peninsula in the south of Argyll and Bute, Scotland. It is located on the western shore of the upper Firth of Clyde, to the south of the Holy Loch and to the north of Innellan. As wel ...

before joining the

Merchant Navy in 1932 and becoming a ship's master.

Having first met in April 1940 at a music hall in

Workington

Workington is a coastal town and civil parish at the mouth of the River Derwent on the west coast in the Allerdale borough of Cumbria, England. The town was historically in Cumberland. At the 2011 census it had a population of 25,207.

Locat ...

, they married within three months. After the war the couple moved in with Ethel's aggressive mother, Zona Ann (Williams), whom Livingstone considered "tyrannical". Livingstone's sister Lin was born 2 years later. Robert and Ethel went through various jobs in the post-war years, with the former working on fishing trawlers and

English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

ferries, while the latter worked in a bakers, at

Freemans

Freemans is a British online and catalogue clothing retailer headquartered in Bradford, England. Freemans offers a range of products, predominantly clothing, footwear and homewares.

History

The company was founded as Freemans & Co in 1905 by ...

catalogue dispatch and as a cinema usherette. Livingstone's parents were "working class

Tories

A Tory () is a person who holds a political philosophy known as Toryism, based on a British version of traditionalism and conservatism, which upholds the supremacy of social order as it has evolved in the English culture throughout history. The ...

", and unlike many Conservative voters at the time did not hold to

socially conservative

Social conservatism is a political philosophy and variety of conservatism which places emphasis on traditional power structures over social pluralism. Social conservatives organize in favor of duty, traditional values and social institution ...

views on race and sexuality, opposing racism and homophobia. The family was nominally

Anglican, although Livingstone abandoned

Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

when he was 11, becoming an

atheist.

[ Livingstone 2005.]

Moving to a

Tulse Hill

Tulse Hill is a district in the London Borough of Lambeth in South London that sits on Brockwell Park. It is approximately five miles from Charing Cross and is bordered by Brixton, Dulwich, Herne Hill, Streatham and West Norwood.

History

The a ...

council housing estate, Livingstone attended St. Leonard's Primary School, and after failing his

11-plus

The eleven-plus (11+) is a standardized examination administered to some students in England and Northern Ireland in their last year of primary education, which governs admission to grammar schools and other secondary schools which use academi ...

exam, in 1956 began secondary education at

Tulse Hill Comprehensive School. In 1957, his family purchased their own property at 66 Wolfington Road,

West Norwood

West Norwood is a largely residential area of south London within the London Borough of Lambeth, located 5.4 miles (8.7 km) south south-east of Charing Cross. The centre of West Norwood sits in a bowl surrounded by hillsides on its east, ...

.

[ Carvel 1984. pp. 31–32.] Rather shy at school, he was bullied, and got into trouble for truancy. One year, his form master was

Philip Hobsbaum

Philip Dennis Hobsbaum (29 June 1932 – 28 June 2005) was a British teacher, poet and critic.

Life

Hobsbaum was born into a Polish Jewish family in London, and brought up in Bradford, Yorkshire, where he attended Belle Vue Boys' Grammar Sc ...

, who encouraged his pupils to debate current events, first interesting Livingstone in politics. He related that he became "an argumentative cocky little brat" at home, bringing up topics at the dinner table to enrage his father. His interest in politics was furthered by the 1958 Papal election of

Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death in June 19 ...

– a man who had "a strong impact" on Livingstone – and the

1960 United States presidential election. At Tulse Hill Comprehensive he gained an interest in

amphibians and

reptiles, keeping several as pets; his mother worried that rather than focusing on school work all he cared about was "his pet lizard and friends". At school he attained four

O-levels

The O-Level (Ordinary Level) is a subject-based qualification conferred as part of the General Certificate of Education. It was introduced in place of the School Certificate in 1951 as part of an educational reform alongside the more in-depth ...

in English Literature, English Language, Geography and Art, subjects he later described as "the easy ones". He started work rather than stay on for the non-compulsory

sixth form

In the education systems of England, Northern Ireland, Wales, Jamaica, Trinidad and Tobago and some other Commonwealth countries, sixth form represents the final two years of secondary education, ages 16 to 18. Pupils typically prepare for A-l ...

, which required six O-levels.

From 1962 to 1970, he worked as a technician at the

Chester Beatty cancer research

Cancer research is research into cancer to identify causes and develop strategies for prevention, diagnosis, treatment, and cure.

Cancer research ranges from epidemiology, molecular bioscience to the performance of clinical trials to evaluate and ...

laboratory in

Fulham, looking after animals used in

experimentation

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs when a ...

. Most of the technicians were socialists, and Livingstone helped found a branch of the

Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs

The Association of Scientific, Technical and Managerial Staffs (ASTMS) was a British trade union which existed between 1969 and 1988.

History

The ASTMS was created in 1969 when ASSET (the Association of Supervisory Staffs, Executives and Techni ...

to fight redundancies imposed by company bosses. Livingstone's leftist views solidified upon the election of Labour Prime Minister

Harold Wilson in 1964. With a friend from Chester Beatty, Livingstone toured

West Africa

West Africa or Western Africa is the westernmost region of Africa. The United Nations defines Western Africa as the 16 countries of Benin, Burkina Faso, Cape Verde, The Gambia, Ghana, Guinea, Guinea-Bissau, Ivory Coast, Liberia, Mali, M ...

in 1966, visiting Algeria, Niger, Nigeria, Lagos, Ghana and Togo. Interested in the region's wildlife, Livingstone rescued an infant ostrich from being eaten, donating it to the Lagos children's zoo. Returning home, he took part in several protest marches as a part of the

anti-Vietnam War movement

Opposition to United States involvement in the Vietnam War (before) or anti-Vietnam War movement (present) began with demonstrations in 1965 against the escalating role of the United States in the Vietnam War and grew into a broad social mov ...

, becoming increasingly interested in politics and briefly subscribing to the publication of a

libertarian socialist

Libertarian socialism, also known by various other names, is a left-wing,Diemer, Ulli (1997)"What Is Libertarian Socialism?" The Anarchist Library. Retrieved 4 August 2019. anti-authoritarian, anti-statist and libertarianLong, Roderick T. (20 ...

group,

Solidarity.

Political activism: 1968–1970

Livingstone joined the

Labour Party in March 1968, when he was 23 years old, later describing it as "one of the few recorded instances of a rat climbing aboard a sinking ship". At the time, many leftists were leaving due to the Labour government's support for the U.S. in the

Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vietnam a ...

, cuts to the

National Health Service

The National Health Service (NHS) is the umbrella term for the publicly funded healthcare systems of the United Kingdom (UK). Since 1948, they have been funded out of general taxation. There are three systems which are referred to using the " ...

budget, and restrictions on

trade unions

A trade union (labor union in American English), often simply referred to as a union, is an organization of workers intent on "maintaining or improving the conditions of their employment", ch. I such as attaining better wages and benefits ( ...

; some joined

far-left parties like the

International Socialists or the

Socialist Labour League

The Workers Revolutionary Party is a Trotskyist group in Britain once led by Gerry Healy. In the mid-1980s, it split into several smaller groups, one of which retains possession of the name.

The Club

The WRP grew out of the faction Gerry Healy ...

, or single-issue groups like the

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nuc ...

and the

Child Poverty Action Group

Child Poverty Action Group (CPAG) is a UK charity that works to alleviate poverty and social exclusion. History

The Group first met on 5 March 1965, at a meeting organised by Harriett C. Wilson. It followed the publication of Brian Abel-Smith ...

. The party was suffering mass electoral defeat at the local elections. In London, Labour lost 15 boroughs, including Livingstone's

London Borough of Lambeth, which came under Conservative control. Contrastingly, Livingstone believed that grassroots campaigning – such as

the 1968 student protests – were ineffective, joining Labour because he considered it the best chance for implementing progressive political change in the UK.

Joining his local Labour branch in

Norwood, he involved himself in their operations, within a month becoming chair and secretary of the Norwood

Young Socialists, gaining a place on the constituency's General Management and Executive Committees, and sitting on the Local Government Committee who prepared Labour's manifesto for the next borough election. Hoping for better qualifications, he attended night school, gaining O-levels in Human Anatomy, Physiology and Hygiene, and an A-level in Zoology. Leaving his job at Chester Beatty, in September 1970 he began a 3-year course at the Philippa Fawcett Teacher Training College (PFTTC) in

Streatham; his attendance was poor, and he considered it "a complete waste" of time. Beginning a romantic relationship with Christine Chapman, president of the PFTTC student's union, the couple married in 1973.

Realising the Conservative governance of Lambeth Borough council was hard to unseat, Livingstone aided Eddie Lopez in reaching out to members of the local populace disenfranchised from the traditional Labour leadership. Associating with the leftist Schools' Action Union (SAU) founded in the wake of the 1968 student protests, he encouraged members of the

Brixton branch of the

Black Panthers to join Labour. His involvement in the SAU led to his dismissal from the PFTCC student's union, who disagreed with politicising secondary school pupils.

Lambeth Housing Committee: 1971–1973

In 1971, Livingstone and his comrades developed a new strategy for obtaining political power in Lambeth borough. Focusing on campaigning for the marginal seats in the south of the borough, the safe Labour seats in the north were left to established party members. Public dissatisfaction with the Conservative government of Prime Minister

Edward Heath

Sir Edward Richard George Heath (9 July 191617 July 2005), often known as Ted Heath, was a British politician who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1970 to 1974 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1965 to 1975. Heath a ...

led to Labour's best local government results since the 1940s; Labour leftists gained every marginal seat in Lambeth, and the borough returned to Labour control. In October 1971, Livingstone's father died of a

heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which ma ...

; his mother soon moved to

Lincoln

Lincoln most commonly refers to:

* Abraham Lincoln (1809–1865), the sixteenth president of the United States

* Lincoln, England, cathedral city and county town of Lincolnshire, England

* Lincoln, Nebraska, the capital of Nebraska, U.S.

* Lincol ...

. That year, Labour members voted Livingstone Vice-Chairman of the Housing Committee on the

Lambeth London Borough Council

Lambeth London Borough Council is the local authority for the London Borough of Lambeth in Greater London, England. It is a London borough council, and one of the 32 in the United Kingdom capital of London. The council meets at Lambeth Town Ha ...

, his first job in local government. Reforming the housing system, Livingstone and Committee Chairman Ewan Carr cancelled the proposed rent increase for

council housing, temporarily halting the construction of Europe's largest tower blocks, and founded a Family Squatting Group to ensure that homeless families would be immediately rehoused through

squatting in empty houses. He increased the number of

compulsory purchase orders for private-rented properties, converting them to council housing. They faced opposition to their reforms, which were cancelled by central government.

Livingstone and the leftists became embroiled in factional in-fighting within Labour, vying with centrist members for powerful positions. Although never adopting

Marxism

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialectical ...

, Livingstone became involved with a number of

Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a ...

groups active within Labour; viewing them as potential allies, he became friends with

Chris Knight, Graham Bash and Keith Veness, members of the Socialist Charter, a Trotskyist cell affiliated with the

Revolutionary Communist League that had

infiltrated the Labour party. In his struggle against Labour centrists, Livingstone was influenced by Trotskyist

Ted Knight

Ted Knight (born Tadeusz Wladyslaw Konopka; December 7, 1923August 26, 1986) was an American actor well known for playing the comedic roles of Ted Baxter in ''The Mary Tyler Moore Show'', Henry Rush in ''Too Close for Comfort'', and Judge Elihu ...

, who convinced him to oppose the use of British troops in

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland ( ga, Tuaisceart Éireann ; sco, label= Ulster-Scots, Norlin Airlann) is a part of the United Kingdom, situated in the north-east of the island of Ireland, that is variously described as a country, province or region. Nort ...

, believing they would simply be used to quash nationalist protests against British rule. Livingstone stood as the leftist candidate for the Chair of the Lambeth Housing Committee in April 1973, but was defeated by

David Stimpson, who undid many of Livingstone and Carr's reforms.

Early years on the Greater London Council: 1973–1977

In June 1972, after a campaign orchestrated by Eddie Lopez, Livingstone was selected as the Labour candidate for Norwood in the

Greater London Council (GLC). In the

1973 GLC elections, he won the seat with 11,622 votes, a clear lead over his Conservative rival. Led by

Reg Goodwin, the GLC was dominated by Labour, who had 57 seats, compared to 33 held by the Conservatives and 2 by the

Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

. Of the Labour GLC members, around 16, including Livingstone, were staunch leftists. Representing Norwood in the GLC, Livingstone continued as a Lambeth councillor and Vice Chairman of the Lambeth Housing Committee, criticising Lambeth council's dealings with the borough's homeless. Learning that the council had pursued a discriminatory policy of allocating the best housing to white working-class families, Livingstone went public with the evidence, which was published in the ''

South London Press

The ''South London Press, London Weekly News and Mercury (formerly South London Press)'' is a weekly newspaper currently based in Catford, South London. The newspaper covers the latest news, sports and features within the south, central and west ...

''. In August 1973, he publicly threatened to resign from the Lambeth Housing Committee if the council failed "to honour longstanding promises" to rehouse 76 homeless families then staying in dilapidated and overcrowded

halfway accommodation. Frustrated at the council's failure to achieve this, he resigned from the Housing Committee in December 1973.

Considered a radical by the GLC's Labour leadership, Livingstone was allocated the unimportant position of Vice Chairman of the Film Viewing Board, monitoring the release of

soft pornography. Like most Board members, Livingstone opposed censorship, a view he changed with the increasing availability of

extreme pornography

Section 63 of the Criminal Justice and Immigration Act 2008 is a law in the United Kingdom criminalising possession of what it refers to as "extreme pornographic images". The law came into force on 26 January 2009. The legislation was brought in ...

. With growing support from Labour leftists, in March 1974 he was elected to the executive of the Greater London Labour Party (GLLP), responsible for drawing up the manifesto for the GLC Labour group and the lists of candidates for council and parliamentary seats. Turning his attention once more to housing, he became Vice Chairman of the GLC's Housing Management Committee, but was sacked in April 1975 for his opposition to the Goodwin administration's decision to cut £50 million from the GLC's house-building budget. With the

1977 GLC elections approaching, Livingstone recognised the difficulty of retaining his Norwood seat, instead being selected for

Hackney North and Stoke Newington

Hackney North and Stoke Newington is a constituency represented in the House of Commons of the United Kingdom since 1987 by Diane Abbott of the Labour Party, who served as Shadow Home Secretary from 6 October 2016 to 5 April 2020. Abbott was o ...

, a Labour

safe seat, following the retirement of

David Pitt. Accused of being a "

carpetbagger", it ensured he was one of the few leftist Labour councillors to remain on the GLC, which fell into Conservative hands under

Horace Cutler

Sir Horace Walter Cutler (28 July 1912 – 2 March 1997) was a British Conservative politician who served as leader of the Greater London Council from 1977 to 1981. He was noted for his showmanship and flair for publicity and was, in several way ...

.

Hampstead: 1977–1980

Turning towards the

Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

, Livingstone and Christine moved to

West Hampstead

West Hampstead is an area in the London Borough of Camden in north-west London. Mainly defined by the railway stations of the same name, it is situated between Childs Hill to the north, Frognal and Hampstead to the north-east, Swiss Cottage ...

,

north London

North London is the northern part of London, England, north of the River Thames. It extends from Clerkenwell and Finsbury, on the edge of the City of London financial district, to Greater London's boundary with Hertfordshire.

The term ''nor ...

; in June 1977 he was selected by local party members as the Labour parliamentary candidate for the

Hampstead constituency, beating

Vince Cable

Sir John Vincent Cable (born 9 May 1943) is a British politician who was Leader of the Liberal Democrats from 2017 to 2019. He was Member of Parliament (MP) for Twickenham from 1997 to 2015 and from 2017 to 2019. He also served in the Cabinet as ...

. He gained notoriety in the ''

Hampstead and Highgate Express

The Ham & High, officially the Hampstead & Highgate Express is a weekly paid newspaper published in the London Borough of Camden by Archant.

The newspaper is priced at £1 and is published every Thursday.

History

Founded in 1860, from 1862 it ...

'' for publicly reaffirming his support for the controversial issue of

LGBT rights

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender ( LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, ...

, declaring he supported the reduction of the

age of consent for male same-sex activity from 21 to 16, in line with the different-sex age of consent. Becoming active in the politics of the

London Borough of Camden

The London Borough of Camden () is a London borough in Inner London. Camden Town Hall, on Euston Road, lies north of Charing Cross. The borough was established on 1 April 1965 from the area of the former boroughs of Hampstead, Holborn, and ...

, Livingstone was elected Chair of Camden's Housing Committee; putting forward radical reforms, he democratised council housing meetings by welcoming local people, froze rents for a year, reformed the rate collection system, changed rent arrears procedures and implemented further compulsory purchase orders to increase council housing. Criticised by some senior colleagues as incompetent and excessively ambitious, some accused him of encouraging leftists to move into the borough's council housing to increase his local support base.

In 1979, internal crisis rocked Labour as activist group, the Campaign for Labour Democracy, struggled with the

Parliamentary Labour Party

In UK politics, the Parliamentary Labour Party (PLP) is the parliamentary group of the Labour Party in Parliament, i.e. Labour MPs as a collective body. Commentators on the British Constitution sometimes draw a distinction between the Labour ...

for a greater say in party management. Livingstone joined the activists, on 15 July 1978 helping unify small left wing groups as the Socialist Campaign for a Labour Victory (SCLV). Producing a sporadically published paper, ''Socialist Organiser'', as a mouthpiece for Livingstone's views, it criticised Labour Prime Minister

James Callaghan as "anti-working class". In January 1979, Britain was hit by a series of public sector worker strikes that came to be known as the "

Winter of Discontent

The Winter of Discontent was the period between November 1978 and February 1979 in the United Kingdom characterised by widespread strikes by private, and later public, sector trade unions demanding pay rises greater than the limits Prime Minis ...

." In Camden Borough, council employees unionised under the

National Union of Public Employees

The National Union of Public Employees (NUPE) was a British trade union which existed between 1908 and 1993. It represented public sector workers in local government, the Health Service, universities, and water authorities.

History

The union w ...

(NUPE) went on strike, demanding a 35-hour limit to their working week and a weekly wage increase to £60. Livingstone backed the strikers, urging Camden Council to grant their demands, eventually getting his way. District auditor Ian Pickwell, a government-appointed accountant who monitored council finances, claimed that this move was reckless and illegal, taking Camden Council to court. If found guilty, Livingstone would have been held personally responsible for the measure, forced to pay the massive

surcharge, and been disqualified for public office for five years; ultimately the judge threw out the case.

In May 1979, a

general election was held in the United Kingdom. Standing as Labour candidate for Hampstead, Livingstone was defeated by the incumbent Conservative,

Geoffrey Finsberg

Geoffrey Finsberg, Baron Finsberg, (13 June 1926 – 8 October 1996) was a British Conservative politician. He was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Hampstead from 1970 to 1983, and for its successor constituency, Hampstead & Highgate, from 19 ...

. Weakened by the Winter of Discontent, Callaghan's government lost to the Conservatives, whose leader,

Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013) was Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party from 1975 to 1990. She was the first female British prime ...

, became Prime Minister. A staunch right winger and

free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any ot ...

advocate, she became a bitter opponent of the labour movement and Livingstone. Following the electoral defeat, Livingstone told ''Socialist Organiser'' that the blame lay solely with the "Labour government's policies" and the anti-democratic attitude of Callaghan and the Parliamentary Labour Party, calling for greater party democracy and a turn towards a socialist platform. This was a popular message among many Labour activists amassed under the SCLV. The primary figurehead for this leftist trend was

Tony Benn

Anthony Neil Wedgwood Benn (3 April 1925 – 14 March 2014), known between 1960 and 1963 as Viscount Stansgate, was a British politician, writer and diarist who served as a Cabinet minister in the 1960s and 1970s. A member of the Labour Party, ...

, who narrowly missed being elected deputy leader of Labour in September 1981, under new party leader

Michael Foot

Michael Mackintosh Foot (23 July 19133 March 2010) was a British Labour Party politician who served as Labour Leader from 1980 to 1983. Foot began his career as a journalist on ''Tribune'' and the ''Evening Standard''. He co-wrote the 1940 p ...

. The head of the "Bennite left", Benn became "an inspiration and a prophet" to Livingstone; the two became the best known left-wingers in Labour.

Greater London Council leadership

Becoming leader of the GLC: 1979–1981

Inspired by the Bennites, Livingstone planned a GLC take-over; on 18 October 1979, he called a meeting of Labour leftists entitled "Taking over the GLC", beginning publication of monthly newsletter the ''London Labour Briefing''. Focused on increasing leftist power in the London Labour Party, he urged socialists to stand as candidates in the upcoming GLC election. When the time came to choose who would lead London Labour in that election, Livingstone put his name down, but was challenged by the moderate

Andrew McIntosh; in the April 1980 vote, McIntosh beat Livingstone by 14 votes to 13. In September 1980, Livingstone separated from his wife Christine, though they remained amicable. Moving into a small flat at 195 Randolph Avenue,

Maida Vale

Maida Vale ( ) is an affluent residential district consisting of the northern part of Paddington in West London, west of St John's Wood and south of Kilburn. It is also the name of its main road, on the continuous Edgware Road. Maida Vale is ...

with his pet reptiles and amphibians, he divorced in October 1982 and began a relationship with

Kate Allen, chair of Camden Council Women's Committee.

Livingstone turned his attention to achieving a GLC Labour victory, exchanging his safe seat in Hackney North for the marginal Inner London seat at

Paddington

Paddington is an area within the City of Westminster, in Central London. First a medieval parish then a metropolitan borough, it was integrated with Westminster and Greater London in 1965. Three important landmarks of the district are Padd ...

; in May 1981 he won the seat by 2,397 votes. Cutler and the Conservatives learned of Livingstone's plans, proclaiming that a GLC Labour victory would lead to a Marxist takeover of London and then Britain; the Conservative press picked up the story, with the ''

Daily Express'' using the headline of "Why We Must Stop These Red Wreckers". The media coverage was ineffective, and the GLC election of May 1981 led to Labour gaining power, with McIntosh installed as Head of the GLC; within 24 hours he was deposed by members of his own party, and replaced by Livingstone.

On 7 May, Livingstone called a caucus of his supporters; announcing his intent to challenge McIntosh's leadership, he invited those assembled to stand for other GLC posts. The meeting ended at 4:45pm having agreed on a full slate of candidates. At 5 o'clock, McIntosh held a GLC Labour meeting; the attendees called an immediate leadership election, in which Livingstone defeated him by 30 votes to 20. The entire left caucus slate was then elected. The next day, a leftist coup deposed

Sir Ashley Bramall on the

Inner London Education Authority

The Inner London Education Authority (ILEA) was an ad hoc local education authority for the City of London and the 12 Inner London boroughs from 1965 until its abolition in 1990. The authority was reconstituted as a directly elected body corp ...

(ILEA), replacing him with

Bryn Davies; the left group now controlled both the GLC and the ILEA.

McIntosh proclaimed the GLC coup illegitimate, asserting that Labour was in danger from a leftist take-over. The mainstream press criticised the coup; the ''

Daily Mail'' called Livingstone a "left wing extremist", and ''

The Sun'' nicknamed him "Red Ken", stating his victory meant "full-steam-ahead red-blooded Socialism for London." The ''

Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and published digitally that focuses on business and economic current affairs. Based in London, England, the paper is owned by a Japanese holding company, Ni ...

'' issued a "warning" that leftists could use such tactics to take control of the government, when "the erosion of our democracy will surely begin." Thatcher joined the rallying call, proclaiming that leftists like Livingstone had "no time for

parliamentary democracy

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democratic governance of a state (or subordinate entity) where the executive derives its democratic legitimacy from its ability to command the support ("confidence") of the ...

", but were plotting "To impose upon this nation a tyranny which the peoples of

Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russia, whic ...

yearn to cast aside."

Leader of the GLC: 1981–1983

Entering County Hall as GLC leader on 8 May 1981, Livingstone initiated changes, converting the building's

Freemasonic

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

temple into a meeting room and removing many of the privileges enjoyed by GLC members and senior officers. He initiated an open-door policy allowing citizens to hold meetings in the committee rooms free of charge, with County Hall gaining the nickname of "the People's Palace". Livingstone took great pleasure watching the disgust expressed by some Conservative GLC members when non-members began using the building's restaurant. In the ''London Labour Briefing'', Livingstone announced "London's ours! After the most vicious GLC election of all time, the Labour Party has won a working majority on a radical socialist programme." He stated that their job was to "sustain a holding operation until such time as the Tory

onservativegovernment can be brought down and replaced by a left-wing Labour government." There was a perception among Livingstone's allies that they constituted the genuine opposition to Thatcher's government, with Foot's Labour leadership dismissed as ineffectual; they hoped Benn would soon replace him.

There was a widespread public perception that Livingstone's GLC leadership was illegitimate, while the mainstream British media remained resolutely hostile. Livingstone received the levels of national press attention normally reserved for senior

Members of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

. A press interview was arranged with

Max Hastings

Sir Max Hugh Macdonald Hastings (; born 28 December 1945) is a British journalist and military historian, who has worked as a foreign correspondent for the BBC, editor-in-chief of ''The Daily Telegraph'', and editor of the ''Evening Standard'' ...

for the ''

Evening Standard

The ''Evening Standard'', formerly ''The Standard'' (1827–1904), also known as the ''London Evening Standard'', is a local free daily newspaper in London, England, published Monday to Friday in tabloid format.

In October 2009, after be ...

'', in which Livingstone was portrayed as affable but ruthless. ''The Suns editor

Kelvin MacKenzie

Kelvin Calder MacKenzie (born 22 October 1946) is an English media executive and a former newspaper editor. He became editor of '' The Sun'' in 1981, by which time the publication was established as Britain's largest circulation newspaper. Aft ...

took a particular interest in Livingstone, establishing a reporting team to 'dig up the dirt' on him; they were unable to uncover any scandalous information, focusing on his interest in amphibians, a hobby mocked by other media sources. The satirical journal ''

Private Eye'' referred to him as "Ken Leninspart", a combination of

Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov. ( 1870 – 21 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin,. was a Russian revolutionary, politician, and political theorist. He served as the first and founding head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 to 1 ...

and the German left-wing group, the

Spartacus League, proceeding to erroneously claim that Livingstone received funding from the

Libyan ''Jamahiriya''. After Livingstone sued them for

libel, in November 1983 the journal apologised, paying him £15,000 in damages in an out-of-court settlement.

During 1982, Livingstone made new appointments to the GLC governance, with

John McDonnell

John Martin McDonnell (born 8 September 1951) is a British politician who served as Shadow Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2015 to 2020. A member of the Labour Party, he has been Member of Parliament (MP) for Hayes and Harlington since 1997. ...

appointed key chair of finance and

Valerie Wise chair of the new Women's Committee, while

Sir Ashley Bramall became GLC chairman and Tony McBrearty was appointed chair of housing. Others stayed in their former positions, including Dave Wetzel as transport chair and Mike Ward as chair of industry; thus was created what biographer John Carvel described as "the second Livingstone administration", leading to a "more calm and supportive environment". Turning his attention once more to Parliament, Livingstone sought to be selected as the Labour candidate for the constituency of

Brent East, a place which he felt an "affinity" for and where several of his friends lived. At the time, the Brent East Labour Party was characterised by competing factions, with Livingstone attempting to gain the support of both the hard and soft left. Securing a significant level of support from local party members, he nonetheless failed to apply for the candidacy in time, and so the incumbent centrist

Reg Freeson

Reginald Yarnitz Freeson (24 February 1926 – 9 October 2006) was a British Labour politician. He was a Member of Parliament for 23 years, from 1964 to 1987, for Willesden East and later Brent East, with 14 years on the front bench. He be ...

was once more selected as Labour candidate for Brent East. A subsequent vote at the council meeting revealed that 52 local Labour members would have voted for Livingstone, with only 2 for Freeson and 3 abstentions. Nevertheless, in the

1983 United Kingdom general election, Freeson went on to win the Brent East constituency for Labour. In 1983, Livingstone began co-presenting a late night television chat show with

Janet Street-Porter for

London Weekend Television

London Weekend Television (LWT) (now part of the non-franchised ITV London region) was the ITV network franchise holder for Greater London and the Home Counties at weekends, broadcasting from Fridays at 5.15 pm (7:00 pm from 1968 un ...

.

Fares Fair and transport policy

The Greater London Labour Manifesto for the 1981 elections, although written under McIntosh's leadership, had been determined by a special conference of the London Labour Party in October 1980 in which Livingstone's speech had been decisive on transport policy. The manifesto focused on job creation schemes and cutting London Transport fares, and it was to these issues that Livingstone's administration turned. One primary manifesto focus had been a pledge known as

Fares Fair, which focused on reducing

London Underground

The London Underground (also known simply as the Underground or by its nickname the Tube) is a rapid transit system serving Greater London and some parts of the adjacent counties of Buckinghamshire, Essex and Hertfordshire in England.

The ...

fares and freezing them at that lower rate. Based on a fare freeze implemented by the

South Yorkshire Metropolitan County Council in 1975, it was widely considered to be a moderate and mainstream policy by Labour, which it was hoped would get more Londoners using public transport, thereby reducing congestion. In October 1981, the GLC implemented their policy, cutting London Transport fares by 32%; to fund the move, the GLC planned to increase the London

rates.

The legality of the Fares Fair policy was challenged by Dennis Barkway, Conservative leader of the

London Borough of Bromley

The London Borough of Bromley () is the southeasternmost of the London boroughs that make up Greater London, bordering the ceremonial county of Kent, which most of Bromley was part of before 1965. The borough's population is an estimated 332,3 ...

council, who complained that his constituents were having to pay for cheaper fares on the London Underground when it did not operate in their borough. Although the Divisional Court initially found in favour of the GLC, Bromley Borough took the issue to the

Court of Appeal, where three judges –

Lord Denning

Alfred Thompson "Tom" Denning, Baron Denning (23 January 1899 – 5 March 1999) was an English lawyer and judge. He was called to the bar of England and Wales in 1923 and became a King's Counsel in 1938. Denning became a judge in 1944 wh ...

,

Lord Justice Oliver and Lord Justice Watkins – reversed the previous decision, finding in favour of Bromley Borough on 10 November. They proclaimed that the Fares Fair policy was illegal because the GLC was expressly forbidden from choosing to run London Transport at a deficit, even if this was in the perceived interest of Londoners. The GLC appealed this decision, taking the case to the

House of Lords

The House of Lords, also known as the House of Peers, is the upper house of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Membership is by appointment, heredity or official function. Like the House of Commons, it meets in the Palace of Westminste ...

; on 17 December five

Law Lords

Lords of Appeal in Ordinary, commonly known as Law Lords, were judges appointed under the Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876 to the British House of Lords, as a committee of the House, effectively to exercise the judicial functions of the House of ...

unanimously ruled in favour of Bromley Borough Council, putting a permanent end to the Fares Fair policy. GLC transport chairman Dave Wetzel labelled the judges "Vandals in Ermine" while Livingstone maintained his belief that the judicial decision was politically motivated.

Initially presenting a motion to the GLC Labour groups that they refuse to comply with the judicial decision and continue with the policy regardless, but was out-voted by 32–22; many commentators claimed that Livingstone had only been bluffing in order to save face among the Labour Left. Instead, Livingstone got on board with a campaign known as "Keep Fares Fair" in order to bring about a change in the law that would make the Fares Fair policy legal; an alternate movement, "Can't Pay, Won't Pay", accused Livingstone of being a sell-out and insisted that the GLC proceed with its policies regardless of their legality. One aspect of the London Transport reforms was however maintained; the new system of

flat fares within ticket zones, and the inter-modal

Travelcard

The Travelcard is an inter-modal travel ticket for unlimited use on the London Underground, London Overground, Elizabeth line, Docklands Light Railway, London Trams, London Buses and National Rail services in the Greater London area. Tr ...

ticket continues as the basis of the ticketing system. The GLC then put together new measures in the hope of reducing London Transport fares by the more modest amount of 25%, taking them back to roughly the price that they were when Livingstone's administration took office; it was ruled legal in January 1983, and subsequently implemented.

GLEB and nuclear disarmament

Livingstone's administration founded the Greater London Enterprise Board (GLEB) to create employment by investing in the industrial regeneration of London, with the funds provided by the council, its workers' pension fund and the financial markets. Livingstone later claimed that GLC bureaucrats obstructed much of what GLEB tried to achieve. Other policies implemented by the Labour Left also foundered. Attempts to prevent the sale-off of GLC council housing largely failed, in part due to the strong opposition from the Conservative government. ILEA attempted to carry through with its promise to cut the price of

school meals

A school meal or school lunch (also known as hot lunch, a school dinner, or school breakfast) is a meal provided to students and sometimes teachers at a school, typically in the middle or beginning of the school day. Countries around the world ...

in the capital from 35p to 25p, but was forced to abandon its plans following legal advice that the councillors could be made to pay the surcharge and disqualified from public office.

The Livingstone administration took a strong stance on the issue of

nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

, proclaiming London a "

nuclear-free zone

A nuclear-free zone is an area in which nuclear weapons (see nuclear-weapon-free zone) and nuclear power plants are banned. The specific ramifications of these depend on the locale in question.

Nuclear-free zones usually neither address nor pro ...

". On 20 May 1981, the GLC halted its annual spending of £1 million on nuclear war defence plans, with Livingstone's deputy, Illtyd Harrington, proclaiming that "we are challenging... the absurd cosmetic approach to Armageddon." They published the names of the 3000 politicians and administrators who had been earmarked for survival in underground bunkers in the event of a nuclear strike on London. Thatcher's government remained highly critical of these moves, putting out a propaganda campaign explaining their argument for the necessity of Britain's

nuclear deterrent

Nuclear strategy involves the development of doctrines and strategies for the production and use of nuclear weapons.

As a sub-branch of military strategy, nuclear strategy attempts to match nuclear weapons as means to political ends. In addit ...

to counter the

Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

.

Egalitarian policies

Livingstone's administration advocated measures to improve the lives of minorities within London, who together made up a sizeable percentage of the city's population; what

Reg Race

Denys Alan Reginald Race (born 23 June 1947) is a British Labour Party politician.

Parliamentary career

He unsuccessfully contested the Conservative-held constituency of Ruislip-Northwood at the February 1974 general election and again at the ...

called "the Rainbow Coalition". The GLC allocated a small percentage of its expenditure on funding minority community groups, including the London Gay Teenage Group,

English Collective of Prostitutes

The English Collective of Prostitutes (ECP) is a campaigning group which supports the decriminalisation of prostitution, sex workers' right to recognition and safety, and the provision of financial alternatives to prostitution so that no one ...

, Women Against Rape, Lesbian Line, A Woman's Place, and Rights of Women. Believing these groups could initiate social change, the GLC increased its annual funding of voluntary organisations from £6 million in 1980 to £50 million in 1984. They provided loans to such groups, coming under a barrage of press criticism for awarding a loan to the Sheba Feminist Publishers, whose works were widely labelled

pornographic

Pornography (often shortened to porn or porno) is the portrayal of sexual subject matter for the exclusive purpose of sexual arousal. Primarily intended for adults, . In July 1981, Livingstone founded the Ethnic Minorities Committee, the Police Committee, and the Gay and Lesbian Working Party, and in June 1982, a Women's Committee was also established. Believing the

Metropolitan Police to be a racist organisation, he appointed

Paul Boateng

Paul Yaw Boateng, Baron Boateng (born 14 June 1951) is a British Labour Party politician, who was the Member of Parliament (MP) for Brent South from 1987 to 2005, becoming the UK's first Black Cabinet Minister in May 2002, when he was appoi ...

to head the Police Committee and monitor the force's activities. Considering the police a highly political organisation, he publicly remarked that "When you canvas police flats at election time, you find that they are either Conservatives who think of Thatcher as a bit of a pinko or they are

National Front."

The Conservatives and mainstream press were largely critical of these measures, considering them symptomatic of what they termed the "

loony left

The loony left is a pejorative term used to describe those considered to be politically hard left. First recorded as used in 1977, the term was widely used in the United Kingdom in the campaign for the 1987 general election and subsequently both ...

". Claiming that these only served "fringe" interests, their criticisms often exhibited

racist,

homophobic

Homophobia encompasses a range of negative attitudes and feelings toward homosexuality or people who are identified or perceived as being lesbian, gay or bisexual. It has been defined as contempt, prejudice, aversion, hatred or antipathy, m ...

and

sexist sentiment. A number of journalists fabricated stories designed to discredit Livingstone and the "loony left", for instance claiming that the GLC made its workers drink only Nicaraguan

coffee

Coffee is a drink prepared from roasted coffee beans. Darkly colored, bitter, and slightly acidic, coffee has a stimulating effect on humans, primarily due to its caffeine content. It is the most popular hot drink in the world.

Seeds of ...

in solidarity with

the country's socialist government, and that

Haringey Council leader

Bernie Grant

Bernard Alexander Montgomery Grant (17 February 1944 – 8 April 2000) was a British Labour Party politician who was the Member of Parliament for Tottenham, London, from 1987 to his death in 2000.

Biography

Bernie Grant was born in Georgetown ...

had banned the use of the term "black bin liner" and the rhyme "

Baa Baa Black Sheep", because they were perceived as racially insensitive. Writing in 2008, BBC reporter Andrew Hosken noted that although most of Livingstone's GLC administration's policies were ultimately a failure, its role in helping change social attitudes towards women and minorities in London remained its "enduring legacy".

Republicanism, Ireland and the ''Labour Herald''

Invited to the

Wedding of Charles, Prince of Wales, and Lady Diana Spencer

The wedding of the Prince of Wales (future King Charles III) and Lady Diana Spencer took place on Wednesday, 29 July 1981, at St Paul's Cathedral in London, United Kingdom. The groom was the heir apparent to the British throne, and the bride was ...

at

St Paul's Cathedral in July 1981, Livingstone – a

republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

critical of the

monarchy

A monarchy is a government#Forms, form of government in which a person, the monarch, is head of state for life or until abdication. The legitimacy (political)#monarchy, political legitimacy and authority of the monarch may vary from restric ...

– wished the couple well but turned down the offer. He also permitted

Irish republican protesters to hold a vigil on the steps of County Hall throughout the wedding celebrations, both actions that brought strong press criticism. His administration supported the People's March for Jobs, a demonstration of 500 anti-unemployment protesters who marched to London from Northern England, allowing them to sleep in County Hall and catering for them. Costing £19,000, critics argued that Livingstone was illegally using public money for his own political causes. The GLC orchestrated a propaganda campaign against Thatcher's government, in January 1982 erecting a sign on the top of County Hall – clearly visible from the

Houses of Parliament

The Palace of Westminster serves as the meeting place for both the House of Commons and the House of Lords, the two houses of the Parliament of the United Kingdom. Informally known as the Houses of Parliament, the Palace lies on the north ban ...

– stating the number of unemployed in London.

In September 1981, a weekly newspaper, the ''Labour Herald'', was announced with Livingstone,

Ted Knight

Ted Knight (born Tadeusz Wladyslaw Konopka; December 7, 1923August 26, 1986) was an American actor well known for playing the comedic roles of Ted Baxter in ''The Mary Tyler Moore Show'', Henry Rush in ''Too Close for Comfort'', and Judge Elihu ...

and Matthew Warburton as co-editors. It was published by a press owned by the Trotskyist

Workers Revolutionary Party (WRP), who had financed it with funding from Libya and other countries in the middle east. Evidence is lacking to indicate Livingstone knew about the funding at the time. Livingstone's commercial relationship with WRP leader

Gerry Healy

Thomas Gerard Healy (3 December 1913 – 14 December 1989) was a political activist, a co-founder of the International Committee of the Fourth International and the leader of the Socialist Labour League and later the Workers Revolutionary Par ...

was controversial among British socialists, many of whom disapproved of Healy's reputation for violence. In the newspaper in 1982, perceiving a neglect by Labour of the Israel-Palestine conflict, Livingstone wrote of "a distortion running right the way through British politics" because "a majority of Jews in this country supported the Labour Party and elected a number of Jewish Labour MPs". The ''Labour Herald'' folded in 1985, after Healy was accused of being a sex offender and he was expelled from the WRP.

A supporter of

Irish reunification

United Ireland, also referred to as Irish reunification, is the proposition that all of Ireland should be a single sovereign state. At present, the island is divided politically; the sovereign Republic of Ireland has jurisdiction over the maj ...

, Livingstone had connections with the left-wing Irish republican party

Sinn Féin

Sinn Féin ( , ; en, " eOurselves") is an Irish republican and democratic socialist political party active throughout both the Republic of Ireland and Northern Ireland.

The original Sinn Féin organisation was founded in 1905 by Arthur G ...

and in July, met with the mother of an imprisoned

Provisional Irish Republican Army

The Irish Republican Army (IRA; ), also known as the Provisional Irish Republican Army, and informally as the Provos, was an Irish republican paramilitary organisation that sought to end British rule in Northern Ireland, facilitate Irish reu ...

(IRA) militant

Thomas McElwee

Thomas McElwee (30 November 1957 – 8 August 1981) was an Irish republican who participated in the 1981 hunger strike and a volunteer in the Provisional Irish Republican Army (IRA). From Bellaghy, County Londonderry, Northern Ireland, he di ...

, then taking part in the

1981 Irish hunger strike

The 1981 Irish hunger strike was the culmination of a five-year protest during the Troubles by Irish republican prisoners in Northern Ireland. The protest began as the blanket protest in 1976, when the British government withdrew Special C ...

. That day, Livingstone publicly proclaimed his support for those prisoners on hunger strike, claiming that the British government's fight against the IRA was not "some sort of campaign against

terrorism

Terrorism, in its broadest sense, is the use of criminal violence to provoke a state of terror or fear, mostly with the intention to achieve political or religious aims. The term is used in this regard primarily to refer to intentional violen ...

" but was "the last colonial war." He was criticised for this meeting and his statements in the mainstream press, while Prime Minister Thatcher claimed that his comments constituted "the most disgraceful statement I have ever heard." Soon after, he also met with the children of Yvonne Dunlop, an Irish Protestant who had been killed in McElwee's bomb attack.

On 10 October, the IRA bombed London's

Chelsea Barracks

Chelsea Barracks was a British Army barracks located in the City of Westminster, London, between the districts of Belgravia, Chelsea and Pimlico on Chelsea Bridge Road.

The barracks closed in the late 2000s, and the site is currently being redeve ...

, killing 2 and injuring 40. Denouncing the attack, Livingstone informed members of the

Cambridge University

The University of Cambridge is a Public university, public collegiate university, collegiate research university in Cambridge, England. Founded in 1209 and granted a royal charter by Henry III of England, Henry III in 1231, Cambridge is the world' ...

Tory Reform Group

The Tory Reform Group (TRG) is a pressure group associated with the British Conservative Party that works to promote "modern, progressive Conservatism... economic efficiency and social justice" and "a Conservatism that supports equality, divers ...

that it was a misunderstanding to view the IRA as "criminals or lunatics" because of their political motives and that "violence will recur again and again as long as we are in Ireland." Mainstream press criticised him for these comments, with ''The Sun'' labeling him "the most odious man in Britain". In response, Livingstone proclaimed that the press coverage had been "ill-founded, utterly out of context and distorted", reiterating his opposition both to IRA attacks and British rule in Northern Ireland. Anti-Livingstone pressure mounted and on 15 October he was attacked in the street by members of unionist militia, The Friends of Ulster. In a second incident, Livingstone was attacked by

far right skinheads shouting "commie bastard" at the Three Horseshoes Pub in Hampstead. Known as "Green Ken" among

Ulster Unionists

The Ulster Unionist Party (UUP) is a unionist political party in Northern Ireland. The party was founded in 1905, emerging from the Irish Unionist Alliance in Ulster. Under Edward Carson, it led unionist opposition to the Irish Home Rule movem ...

, Unionist paramilitary

Michael Stone of the

Ulster Defence Association

The Ulster Defence Association (UDA) is an Ulster loyalist paramilitary group in Northern Ireland. It was formed in September 1971 as an umbrella group for various loyalist groups and undertook an armed campaign of almost 24 years as one of t ...

plotted to kill Livingstone, only abandoning the plan when he became convinced that the security services were monitoring him.

[Matthew Tempest,]

Loyalists planned to kill Livingstone

, ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'', 10 June 2003[My plot to murder Livingstone, by former hitman]

" thisislondon.co.uk, 1 November 2006

Livingstone agreed to meet

Gerry Adams

Gerard Adams ( ga, Gearóid Mac Ádhaimh; born 6 October 1948) is an Irish republican politician who was the president of Sinn Féin between 13 November 1983 and 10 February 2018, and served as a Teachta Dála (TD) for Louth from 2011 to 2020. ...

, Sinn Féin President and IRA-supporter, after Adams was invited to London by Labour members of the Troops Out campaign in December 1982. The same day as the invitation was made, the

Irish National Liberation Army (INLA)

bombed The Droppin Well bar in

Ballykelly, County Londonderry

Ballykelly () is a village and townland in County Londonderry, Northern Ireland. It lies west of Limavady on the main Derry to Limavady A2 road and is east of Derry. It is designated as a Large Village and in 2011 the population of Ballykell ...

, killing 11 soldiers and 6 civilians; in the aftermath, Livingstone was pressured to cancel the meeting. Expressing his horror at the bombing, Livingstone insisted that the meeting proceed, for Adams had no connection with the INLA, but Conservative Home Secretary

Willie Whitelaw

William Stephen Ian Whitelaw, 1st Viscount Whitelaw, (28 June 1918 – 1 July 1999) was a British Conservative Party politician who served in a wide number of Cabinet positions, most notably as Home Secretary from 1979 to 1983 and as ''de fac ...

banned Adams' entry to Britain with the

1976 Prevention of Terrorism (Temporary Provisions) Act. In February 1983, Livingstone visited Adams in his constituency of

West Belfast, receiving a hero's welcome from local republicans. In July 1983, Adams finally came to London by invitation of Livingstone and MP

Jeremy Corbyn

Jeremy Bernard Corbyn (; born 26 May 1949) is a British politician who served as Leader of the Opposition and Leader of the Labour Party from 2015 to 2020. On the political left of the Labour Party, Corbyn describes himself as a socialist ...

, allowing him to present his views to a mainstream British audience through televised interviews. In August, Livingstone was interviewed on Irish state radio, proclaiming that Britain's 800-year occupation of Ireland was more destructive than the

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

; he was publicly criticised by Labour members and the press. He also controversially expressed solidarity with the

Marxist–Leninist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialect ...

government of

Fidel Castro in Cuba against the U.S. economic embargo, in return receiving an annual Christmas gift of Cuban rum from the Cuban embassy.

Courting further controversy, in the

Falklands War of 1982, during which the United Kingdom battled Argentina for control of the

Falkland Islands

The Falkland Islands (; es, Islas Malvinas, link=no ) is an archipelago in the South Atlantic Ocean on the Patagonian Shelf. The principal islands are about east of South America's southern Patagonian coast and about from Cape Dubouze ...

, Livingstone stated his belief that the islands rightfully belonged to the Argentinian people, but not the military junta then ruling the country. Upon British victory, he sarcastically remarked that "Britain had finally been able to beat the hell out of a country smaller, weaker and even worse governed than we were." Challenging the Conservative government's militarism, the GLC proclaimed 1983 to be "Peace Year", solidifying ties with the

Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament

The Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament (CND) is an organisation that advocates unilateral nuclear disarmament by the United Kingdom, international nuclear disarmament and tighter international arms regulation through agreements such as the Nuc ...

(CND) in order to advocate international

nuclear disarmament

Nuclear may refer to:

Physics

Relating to the nucleus of the atom:

*Nuclear engineering

*Nuclear physics

*Nuclear power

*Nuclear reactor

*Nuclear weapon

*Nuclear medicine

*Radiation therapy

*Nuclear warfare

Mathematics

* Nuclear space

* Nuclea ...

, a measure opposed by the Thatcher government. In keeping with this pacifistic outlook, they banned the

Territorial Army from marching past County Hall that year. The GLC then proclaimed 1984 to be "Anti-Racism Year". In July 1985, the GLC twinned London with the Nicaraguan city of

Managua

)

, settlement_type = Capital city

, motto =

, image_map =

, mapsize =

, map_caption =

, pushpin_map = Nicar ...

, then under the control of the socialist

Sandinista National Liberation Front

The Sandinista National Liberation Front ( es, Frente Sandinista de Liberación Nacional, FSLN) is a socialist political party in Nicaragua. Its members are called Sandinistas () in both English and Spanish. The party is named after Augusto Cé ...