Kelvin Temperature on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Thermodynamic temperature is a quantity defined in thermodynamics as distinct from kinetic theory or

CODATA Value: Boltzmann constant

'. ''The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty''. National Institute of Standards and Technology. The compound unit of measure for the Boltzmann constant is often also written as J·K−1, with a multiplication dot (·) and a kelvin symbol that is followed by a superscripted ''negative 1'' exponent. This is another mathematical syntax denoting the same measure: '' joules'' (the SI unit for energy, including kinetic energy) ''per kelvin''. The microscopic property that imbues material substances with a temperature can be readily understood by examining the ideal gas law, which relates, per the Boltzmann constant, how heat energy causes precisely defined changes in the pressure and temperature of certain gases. This is because monatomic gases like helium and argon behave kinetically like freely moving perfectly elastic and spherical billiard balls that move only in a specific subset of the possible motions that can occur in matter: that comprising the ''three translational''

defines zero-point

energy as the "vibrational energy that molecules retain even at the absolute zero of temperature". ZPE is the result of all-pervasive energy fields in the vacuum between the fundamental particles of nature; it is responsible for the Casimir effect and other phenomena. See

Zero Point Energy and Zero Point Field

'. See also

'' by the University of Alberta's Department of Physics to learn more about ZPE's effect on Bose–Einstein condensates of helium. Although absolute zero () is not a state of zero molecular motion, it ''is'' the point of zero temperature and, in accordance with the Boltzmann constant, is also the point of zero particle kinetic energy and zero kinetic velocity. To understand how atoms can have zero kinetic velocity and simultaneously be vibrating due to ZPE, consider the following thought experiment: two helium atoms in zero gravity are carefully positioned and observed to have an average separation of 620 pm between them (a gap of ten atomic diameters). It is an "average" separation because ZPE causes them to jostle about their fixed positions. Then one atom is given a kinetic kick of precisely 83 yoctokelvins (1 yK = ). This is done in a way that directs this atom's velocity vector at the other atom. With 83 yK of kinetic energy between them, the 620 pm gap through their common barycenter would close at a rate of 719 pm/s and they would collide after 0.862 second. This is the same speed as shown in the '' Fig. 1 ''animation above. Before being given the kinetic kick, both atoms had zero kinetic energy and zero kinetic velocity because they could persist indefinitely in that state and relative orientation even though both were being jostled by ZPE. At , no kinetic energy is available for transfer to other systems. Note too that absolute zero serves as the baseline atop which thermodynamics and its

''Derivation of the classical electromagnetic zero-point radiation spectrum via a classical thermodynamic operation involving van der Waals forces''

Daniel C. Cole, Physical Review A, 42 (1990) 1847. Though the atoms in, for instance, a container of liquid helium that was ''precisely'' at absolute zero would still jostle slightly due to zero-point energy, a theoretically perfect heat engine with such helium as one of its working fluids could never transfer any net kinetic energy ( heat energy) to the other working fluid and no thermodynamic work could occur. Temperature is generally expressed in absolute terms when scientifically examining temperature's interrelationships with certain other physical properties of matter such as its volume or pressure (see Gay-Lussac's law), or the wavelength of its emitted

It is neither difficult to imagine atomic motions due to kinetic temperature, nor distinguish between such motions and those due to zero-point energy. Consider the following hypothetical thought experiment, as illustrated in ''Fig. 2.5'' at left, with an atom that is exceedingly close to absolute zero. Imagine peering through a common optical microscope set to 400 power, which is about the maximum practical magnification for optical microscopes. Such microscopes generally provide fields of view a bit over 0.4 mm in diameter. At the center of the field of view is a single levitated argon atom (argon comprises about 0.93% of air) that is illuminated and glowing against a dark backdrop. If this argon atom was at a beyond-record-setting ''one-trillionth'' of a kelvin above absolute zero, and was moving perpendicular to the field of view towards the right, it would require 13.9 seconds to move from the center of the image to the 200-micron tick mark; this travel distance is about the same as the width of the period at the end of this sentence on modern computer monitors. As the argon atom slowly moved, the positional jitter due to zero-point energy would be much less than the 200-nanometer (0.0002 mm) resolution of an optical microscope. Importantly, the atom's translational velocity of 14.43 microns per second constitutes all its retained kinetic energy due to not being precisely at absolute zero. Were the atom ''precisely'' at absolute zero, imperceptible jostling due to zero-point energy would cause it to very slightly wander, but the atom would perpetually be located, on average, at the same spot within the field of view. This is analogous to a boat that has had its motor turned off and is now bobbing slightly in relatively calm and windless ocean waters; even though the boat randomly drifts to and fro, it stays in the same spot in the long term and makes no headway through the water. Accordingly, an atom that was precisely at absolute zero would not be "motionless", and yet, a statistically significant collection of such atoms would have zero net kinetic energy available to transfer to any other collection of atoms. This is because regardless of the kinetic temperature of the second collection of atoms, they too experience the effects of zero-point energy. Such are the consequences of

It is neither difficult to imagine atomic motions due to kinetic temperature, nor distinguish between such motions and those due to zero-point energy. Consider the following hypothetical thought experiment, as illustrated in ''Fig. 2.5'' at left, with an atom that is exceedingly close to absolute zero. Imagine peering through a common optical microscope set to 400 power, which is about the maximum practical magnification for optical microscopes. Such microscopes generally provide fields of view a bit over 0.4 mm in diameter. At the center of the field of view is a single levitated argon atom (argon comprises about 0.93% of air) that is illuminated and glowing against a dark backdrop. If this argon atom was at a beyond-record-setting ''one-trillionth'' of a kelvin above absolute zero, and was moving perpendicular to the field of view towards the right, it would require 13.9 seconds to move from the center of the image to the 200-micron tick mark; this travel distance is about the same as the width of the period at the end of this sentence on modern computer monitors. As the argon atom slowly moved, the positional jitter due to zero-point energy would be much less than the 200-nanometer (0.0002 mm) resolution of an optical microscope. Importantly, the atom's translational velocity of 14.43 microns per second constitutes all its retained kinetic energy due to not being precisely at absolute zero. Were the atom ''precisely'' at absolute zero, imperceptible jostling due to zero-point energy would cause it to very slightly wander, but the atom would perpetually be located, on average, at the same spot within the field of view. This is analogous to a boat that has had its motor turned off and is now bobbing slightly in relatively calm and windless ocean waters; even though the boat randomly drifts to and fro, it stays in the same spot in the long term and makes no headway through the water. Accordingly, an atom that was precisely at absolute zero would not be "motionless", and yet, a statistically significant collection of such atoms would have zero net kinetic energy available to transfer to any other collection of atoms. This is because regardless of the kinetic temperature of the second collection of atoms, they too experience the effects of zero-point energy. Such are the consequences of

At one specific thermodynamic point, the melting point (which is 0 °C across a wide pressure range in the case of water), all the atoms or molecules are, on average, at the maximum energy threshold their chemical bonds can withstand without breaking away from the lattice. Chemical bonds are all-or-nothing forces: they either hold fast, or break; there is no in-between state. Consequently, when a substance is at its melting point, every joule of added thermal energy only breaks the bonds of a specific quantity of its atoms or molecules, converting them into a liquid of precisely the same temperature; no kinetic energy is added to translational motion (which is what gives substances their temperature). The effect is rather like

At one specific thermodynamic point, the melting point (which is 0 °C across a wide pressure range in the case of water), all the atoms or molecules are, on average, at the maximum energy threshold their chemical bonds can withstand without breaking away from the lattice. Chemical bonds are all-or-nothing forces: they either hold fast, or break; there is no in-between state. Consequently, when a substance is at its melting point, every joule of added thermal energy only breaks the bonds of a specific quantity of its atoms or molecules, converting them into a liquid of precisely the same temperature; no kinetic energy is added to translational motion (which is what gives substances their temperature). The effect is rather like

1702–1703: Guillaume Amontons (1663–1705) published two papers that may be used to credit him as being the first researcher to deduce the existence of a fundamental (thermodynamic) temperature scale featuring an absolute zero. He made the discovery while endeavoring to improve upon the air thermometers in use at the time. His J-tube thermometers comprised a mercury column that was supported by a fixed mass of air entrapped within the sensing portion of the thermometer. In thermodynamic terms, his thermometers relied upon the volume / temperature relationship of gas under constant pressure. His measurements of the boiling point of water and the melting point of ice showed that regardless of the mass of air trapped inside his thermometers or the weight of mercury the air was supporting, the reduction in air volume at the ice point was always the same ratio. This observation led him to posit that a sufficient reduction in temperature would reduce the air volume to zero. In fact, his calculations projected that absolute zero was equivalent to −240 °C—only 33.15 degrees short of the true value of −273.15 °C. Amonton's discovery of a one-to-one relationship between absolute temperature and absolute pressure was rediscovered a century later and popularized within the scientific community by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac. Today, this principle of thermodynamics is commonly known as '' Gay-Lussac's law'' but is also known as ''Amonton's law''.

1742: Anders Celsius (1701–1744) created a "backwards" version of the modern Celsius temperature scale. In Celsius's original scale, zero represented the boiling point of water and 100 represented the melting point of ice. In his paper ''Observations of two persistent degrees on a thermometer'', he recounted his experiments showing that ice's melting point was effectively unaffected by pressure. He also determined with remarkable precision how water's boiling point varied as a function of atmospheric pressure. He proposed that zero on his temperature scale (water's boiling point) would be calibrated at the mean barometric pressure at mean sea level.

1744: Coincident with the death of Anders Celsius, the famous botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) effectively reversed Celsius's scale upon receipt of his first thermometer featuring a scale where zero represented the melting point of ice and 100 represented water's boiling point. The custom-made ''linnaeus-thermometer'', for use in his greenhouses, was made by Daniel Ekström, Sweden's leading maker of scientific instruments at the time. For the next 204 years, the scientific and thermometry communities worldwide referred to this scale as the ''

1702–1703: Guillaume Amontons (1663–1705) published two papers that may be used to credit him as being the first researcher to deduce the existence of a fundamental (thermodynamic) temperature scale featuring an absolute zero. He made the discovery while endeavoring to improve upon the air thermometers in use at the time. His J-tube thermometers comprised a mercury column that was supported by a fixed mass of air entrapped within the sensing portion of the thermometer. In thermodynamic terms, his thermometers relied upon the volume / temperature relationship of gas under constant pressure. His measurements of the boiling point of water and the melting point of ice showed that regardless of the mass of air trapped inside his thermometers or the weight of mercury the air was supporting, the reduction in air volume at the ice point was always the same ratio. This observation led him to posit that a sufficient reduction in temperature would reduce the air volume to zero. In fact, his calculations projected that absolute zero was equivalent to −240 °C—only 33.15 degrees short of the true value of −273.15 °C. Amonton's discovery of a one-to-one relationship between absolute temperature and absolute pressure was rediscovered a century later and popularized within the scientific community by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac. Today, this principle of thermodynamics is commonly known as '' Gay-Lussac's law'' but is also known as ''Amonton's law''.

1742: Anders Celsius (1701–1744) created a "backwards" version of the modern Celsius temperature scale. In Celsius's original scale, zero represented the boiling point of water and 100 represented the melting point of ice. In his paper ''Observations of two persistent degrees on a thermometer'', he recounted his experiments showing that ice's melting point was effectively unaffected by pressure. He also determined with remarkable precision how water's boiling point varied as a function of atmospheric pressure. He proposed that zero on his temperature scale (water's boiling point) would be calibrated at the mean barometric pressure at mean sea level.

1744: Coincident with the death of Anders Celsius, the famous botanist Carl Linnaeus (1707–1778) effectively reversed Celsius's scale upon receipt of his first thermometer featuring a scale where zero represented the melting point of ice and 100 represented water's boiling point. The custom-made ''linnaeus-thermometer'', for use in his greenhouses, was made by Daniel Ekström, Sweden's leading maker of scientific instruments at the time. For the next 204 years, the scientific and thermometry communities worldwide referred to this scale as the ''bipm.org

/ref> '' degree Celsius'' (symbol: °C) in 1948.According to ''The Oxford English Dictionary'' (OED), the term "Celsius's thermometer" had been used at least as early as 1797. Further, the term "The Celsius or Centigrade thermometer" was again used in reference to a particular type of thermometer at least as early as 1850. The OED also cites this 1928 reporting of a temperature: "My altitude was about 5,800 metres, the temperature was 28° Celsius". However, dictionaries seek to find the earliest use of a word or term and are not a useful resource as regards the terminology used throughout the history of science. According to several writings of Dr. Terry Quinn CBE FRS, Director of the BIPM (1988–2004), including ''Temperature Scales from the early days of thermometry to the 21st century''

150 kB PDF, here

as well as ''Temperature'' (2nd Edition / 1990 / Academic Press / 0125696817), the term ''Celsius'' in connection with the centigrade scale was not used whatsoever by the scientific or thermometry communities until after the CIPM and CGPM adopted the term in 1948. The BIPM wasn't even aware that ''degree Celsius'' was in sporadic, non-scientific use before that time. It's also noteworthy that the twelve-volume, 1933 edition of OED did not even have a listing for the word ''Celsius'' (but did have listings for both ''centigrade'' and ''centesimal'' in the context of temperature measurement). The 1948 adoption of ''Celsius'' accomplished three objectives: # All common temperature scales would have their units named after someone closely associated with them; namely, Kelvin, Celsius, Fahrenheit, Réaumur and Rankine. # Notwithstanding the important contribution of Linnaeus who gave the Celsius scale its modern form, Celsius's name was the obvious choice because it began with the letter C. Thus, the symbol °C that for centuries had been used in association with the name ''centigrade'' could continue to be used and would simultaneously inherit an intuitive association with the new name. # The new name eliminated the ambiguity of the term ''centigrade'', freeing it to refer exclusively to the French-language name for the unit of angular measurement. 1777: In his book ''Pyrometrie'' (Berlin

1777: In his book ''Pyrometrie'' (Berlin

1779) completed four months before his death, Johann Heinrich Lambert (1728–1777), sometimes incorrectly referred to as Joseph Lambert, proposed an absolute temperature scale based on the pressure/temperature relationship of a fixed volume of gas. This is distinct from the volume/temperature relationship of gas under constant pressure that Guillaume Amontons discovered 75 years earlier. Lambert stated that absolute zero was the point where a simple straight-line extrapolation reached zero gas pressure and was equal to −270 °C. Circa 1787: Notwithstanding the work of Guillaume Amontons 85 years earlier,

Circa 1787: Notwithstanding the work of Guillaume Amontons 85 years earlier,  1802: Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778–1850) published work (acknowledging the unpublished lab notes of Jacques Charles fifteen years earlier) describing how the volume of gas under constant pressure changes linearly with its absolute (thermodynamic) temperature. This behavior is called Charles's Law and is one of the gas laws. His are the first known formulas to use the number ''273'' for the expansion coefficient of gas relative to the melting point of ice (indicating that absolute zero was equivalent to −273 °C).

1848: William Thomson, (1824–1907) also known as Lord Kelvin, wrote in his paper,

1802: Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (1778–1850) published work (acknowledging the unpublished lab notes of Jacques Charles fifteen years earlier) describing how the volume of gas under constant pressure changes linearly with its absolute (thermodynamic) temperature. This behavior is called Charles's Law and is one of the gas laws. His are the first known formulas to use the number ''273'' for the expansion coefficient of gas relative to the melting point of ice (indicating that absolute zero was equivalent to −273 °C).

1848: William Thomson, (1824–1907) also known as Lord Kelvin, wrote in his paper,

On an Absolute Thermometric Scale

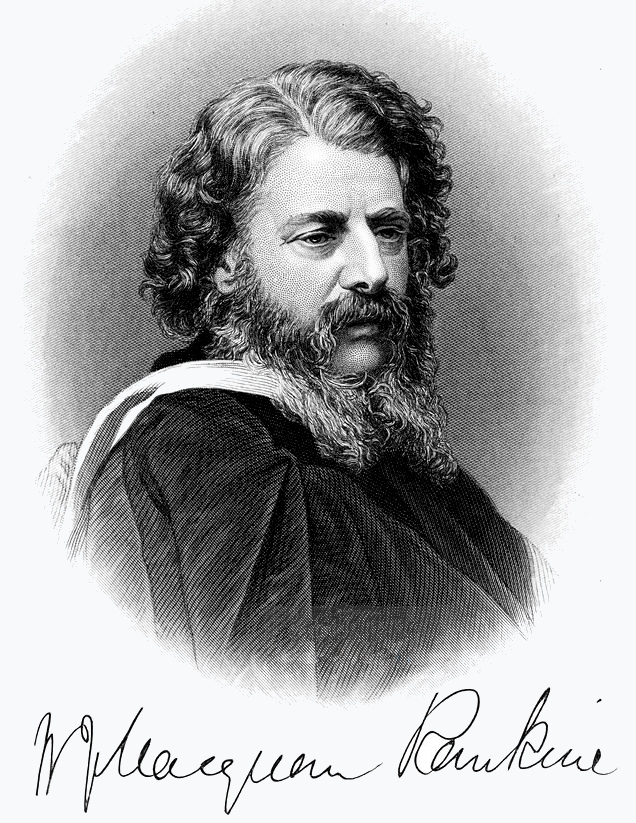

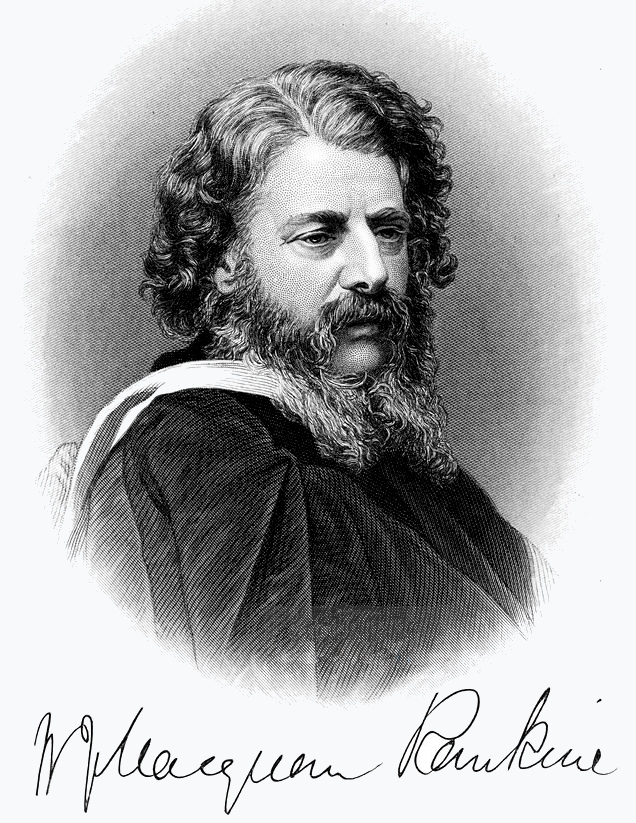

', of the need for a scale whereby ''infinite cold'' (absolute zero) was the scale's zero point, and which used the degree Celsius for its unit increment. Like Gay-Lussac, Thomson calculated that absolute zero was equivalent to −273 °C on the air thermometers of the time. This absolute scale is known today as the kelvin thermodynamic temperature scale. It's noteworthy that Thomson's value of ''−273'' was actually derived from 0.00366, which was the accepted expansion coefficient of gas per degree Celsius relative to the ice point. The inverse of −0.00366 expressed to five significant digits is −273.22 °C which is remarkably close to the true value of −273.15 °C. 1859: Macquorn Rankine (1820–1872) proposed a thermodynamic temperature scale similar to William Thomson's but which used the degree Fahrenheit for its unit increment. This absolute scale is known today as the

1859: Macquorn Rankine (1820–1872) proposed a thermodynamic temperature scale similar to William Thomson's but which used the degree Fahrenheit for its unit increment. This absolute scale is known today as the

Resolution 3

of the 9th CGPM (Conférence Générale des Poids et Mesures, also known as the

formally adopted

the name ''Celsius'' for the ''degree Celsius'' and the ''Celsius temperature scale''. 1954:''

Resolution 3

of the 10th CGPM gave the kelvin scale its modern definition by choosing the triple point of water as its upper defining point (with no change to absolute zero being the null point) and assigning it a temperature of precisely 273.16 kelvins (what was actually written 273.16 ''degrees Kelvin'' at the time). This, in combination with Resolution 3 of the 9th CGPM, had the effect of defining absolute zero as being precisely zero kelvins and −273.15 °C. 1967/1968:''

Resolution 3

of the 13th CGPM renamed the unit increment of thermodynamic temperature ''kelvin'', symbol K, replacing ''degree absolute'', symbol °K. Further, feeling it useful to more explicitly define the magnitude of the unit increment, the 13th CGPM also decided i

Resolution 4

that "The kelvin, unit of thermodynamic temperature, is the fraction 1/273.16 of the thermodynamic temperature of the triple point of water". 2005: The CIPM (Comité International des Poids et Mesures, also known as the International Committee for Weights and Measures

affirmed

that for the purposes of delineating the temperature of the triple point of water, the definition of the kelvin thermodynamic temperature scale would refer to water having an isotopic composition defined as being precisely equal to the nominal specification of Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water. 2019: In November 2018, the 26th General Conference on Weights and Measures (CGPM) changed the definition of the Kelvin by fixing the Boltzmann constant to when expressed in the unit J/K. This change (and other changes in the definition of SI units) was made effective on the 144th anniversary of the Metre Convention, 20 May 2019.

Zero Point Energy and Zero Point Field.

' A Web site with in-depth explanations of a variety of quantum effects. By Bernard Haisch, o

{{DEFAULTSORT:Thermodynamic Temperature Temperature SI base quantities State functions

statistical mechanics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. It does not assume or postulate any natural laws, but explains the macroscopic be ...

.

Historically, thermodynamic temperature was defined by Kelvin in terms of a macroscopic relation between thermodynamic work and heat transfer as defined in thermodynamics, but the kelvin was redefined by international agreement in 2019 in terms of phenomena that are now understood as manifestations of the kinetic energy of free motion of microscopic particles such as atoms, molecules, and electrons. From the thermodynamic viewpoint, for historical reasons, because of how it is defined and measured, this microscopic kinetic definition is regarded as an "empirical" temperature. It was adopted because in practice it can generally be measured more precisely than can Kelvin's thermodynamic temperature.

A thermodynamic temperature reading of zero is of particular importance for the third law of thermodynamics. By convention, it is reported on the '' Kelvin scale'' of temperature in which the unit of measurement is the ''kelvin'' (unit symbol: K). For comparison, a temperature of 295 K is equal to 21.85 °C and 71.33 °F.

Overview

Thermodynamic temperature, as distinct from SI temperature, is defined in terms of a macroscopic Carnot cycle. Thermodynamic temperature is of importance in thermodynamics because it is defined in purely thermodynamic terms. SI temperature is conceptually far different from thermodynamic temperature. Thermodynamic temperature was rigorously defined historically long before there was a fair knowledge of microscopic particles such as atoms, molecules, and electrons. TheInternational System of Units

The International System of Units, known by the international abbreviation SI in all languages and sometimes pleonastically as the SI system, is the modern form of the metric system and the world's most widely used system of measurement. E ...

(SI) specifies the international absolute scale for measuring temperature, and the unit of measure '' kelvin'' (unit symbol: K) for specific values along the scale. The kelvin is also used for denoting temperature ''intervals'' (a span or difference between two temperatures) as per the following example usage: "A 60/40 tin/lead solder is non-eutectic and is plastic through a range of 5 kelvins as it solidifies." A temperature interval of one degree Celsius is the same magnitude as one kelvin.

The magnitude of the kelvin was redefined in 2019 in relation to the ''very physical property'' underlying thermodynamic temperature: the kinetic energy of atomic free particle motion. The redefinition fixed the Boltzmann constant at precisely (J/K).CODATA Value: Boltzmann constant

'. ''The NIST Reference on Constants, Units, and Uncertainty''. National Institute of Standards and Technology. The compound unit of measure for the Boltzmann constant is often also written as J·K−1, with a multiplication dot (·) and a kelvin symbol that is followed by a superscripted ''negative 1'' exponent. This is another mathematical syntax denoting the same measure: '' joules'' (the SI unit for energy, including kinetic energy) ''per kelvin''. The microscopic property that imbues material substances with a temperature can be readily understood by examining the ideal gas law, which relates, per the Boltzmann constant, how heat energy causes precisely defined changes in the pressure and temperature of certain gases. This is because monatomic gases like helium and argon behave kinetically like freely moving perfectly elastic and spherical billiard balls that move only in a specific subset of the possible motions that can occur in matter: that comprising the ''three translational''

degrees of freedom

Degrees of freedom (often abbreviated df or DOF) refers to the number of independent variables or parameters of a thermodynamic system. In various scientific fields, the word "freedom" is used to describe the limits to which physical movement or ...

. The translational degrees of freedom are the familiar billiard ball-like movements along the X, Y, and Z axes of 3D space (see ''Fig. 1'', below). This is why the noble gases all have the same specific heat capacity per atom and why that value is lowest of all the gases.

Molecules (two or more chemically bound atoms), however, have ''internal structure'' and therefore have additional ''internal'' degrees of freedom (see ''Fig. 3'', below), which makes molecules absorb more heat energy for any given amount of temperature rise than do the monatomic gases. Heat energy is born in all available degrees of freedom; this is in accordance with the equipartition theorem, so all available internal degrees of freedom have the same temperature as their three external degrees of freedom. However, the property that gives all gases their pressure, which is the net force per unit area on a container arising from gas particles recoiling off it, is a function of the kinetic energy borne in the freely moving atoms’ and molecules’ three translational degrees of freedom.

Fixing the Boltzmann constant at a specific value, along with other rule making, had the effect of precisely establishing the magnitude of the unit interval of SI temperature, the kelvin, in terms of the average kinetic behavior of the noble gases. Moreover, the ''starting point'' of the thermodynamic temperature scale, absolute zero, was reaffirmed as the point at which ''zero average kinetic energy'' remains in a sample; the only remaining particle motion being that comprising random vibrations due to zero-point energy.

Absolute zero of temperature

Temperature scales are numerical. The numerical zero of a temperature scale is not bound to the absolute zero of temperature. Nevertheless, some temperature scales have their numerical zero coincident with the absolute zero of temperature. Examples are the International SI temperature scale, the Rankine temperature scale, and the thermodynamic temperature scale. Other temperature scales have their numerical zero far from the absolute zero of temperature. Examples are the Fahrenheit scale and the Celsius scale. At the zero point of thermodynamic temperature,absolute zero

Absolute zero is the lowest limit of the thermodynamic temperature scale, a state at which the enthalpy and entropy of a cooled ideal gas reach their minimum value, taken as zero kelvin. The fundamental particles of nature have minimum vibration ...

, the particle constituents of matter have minimal motion and can become no colder. Absolute zero, which is a temperature of zero kelvins (0 K), is precisely equal to −273.15 °C and −459.67 °F. Matter at absolute zero has no remaining transferable average kinetic energy and the only remaining particle motion is due to an ever-pervasive quantum mechanical phenomenon called ZPE ( Zero-Point Energy). While scientists are achieving temperatures ever closer to absolute zero

Absolute zero is the lowest limit of the thermodynamic temperature scale, a state at which the enthalpy and entropy of a cooled ideal gas reach their minimum value, taken as zero kelvin. The fundamental particles of nature have minimum vibration ...

, they can not fully achieve a state of ''zero'' temperature. However, even if scientists could remove ''all'' kinetic thermal energy from matter, quantum mechanical '' zero-point energy'' (ZPE) causes particle motion that can never be eliminated. Encyclopædia Britannica Onlindefines zero-point

energy as the "vibrational energy that molecules retain even at the absolute zero of temperature". ZPE is the result of all-pervasive energy fields in the vacuum between the fundamental particles of nature; it is responsible for the Casimir effect and other phenomena. See

Zero Point Energy and Zero Point Field

'. See also

'' by the University of Alberta's Department of Physics to learn more about ZPE's effect on Bose–Einstein condensates of helium. Although absolute zero () is not a state of zero molecular motion, it ''is'' the point of zero temperature and, in accordance with the Boltzmann constant, is also the point of zero particle kinetic energy and zero kinetic velocity. To understand how atoms can have zero kinetic velocity and simultaneously be vibrating due to ZPE, consider the following thought experiment: two helium atoms in zero gravity are carefully positioned and observed to have an average separation of 620 pm between them (a gap of ten atomic diameters). It is an "average" separation because ZPE causes them to jostle about their fixed positions. Then one atom is given a kinetic kick of precisely 83 yoctokelvins (1 yK = ). This is done in a way that directs this atom's velocity vector at the other atom. With 83 yK of kinetic energy between them, the 620 pm gap through their common barycenter would close at a rate of 719 pm/s and they would collide after 0.862 second. This is the same speed as shown in the '' Fig. 1 ''animation above. Before being given the kinetic kick, both atoms had zero kinetic energy and zero kinetic velocity because they could persist indefinitely in that state and relative orientation even though both were being jostled by ZPE. At , no kinetic energy is available for transfer to other systems. Note too that absolute zero serves as the baseline atop which thermodynamics and its

equations

In mathematics, an equation is a formula that expresses the equality of two expressions, by connecting them with the equals sign . The word ''equation'' and its cognates in other languages may have subtly different meanings; for example, in F ...

are founded because they deal with the exchange of thermal energy between "''systems''" (a plurality of particles and fields modeled as an average). Accordingly, one may examine ZPE-induced particle motion ''within'' a system that is at absolute zero but there can never be a net outflow of thermal energy from such a system. Also, the peak emittance wavelength of black-body radiation shifts to infinity at absolute zero; indeed, a peak no longer exists and black-body photons can no longer escape. Because of ZPE, however, ''virtual'' photons are still emitted at . Such photons are called "virtual" because they can't be intercepted and observed. Furthermore, this ''zero-point radiation'' has a unique ''zero-point spectrum''. However, even though a system emits zero-point radiation, no net heat flow ''Q'' out of such a system can occur because if the surrounding environment is at a temperature greater than , heat will flow inward, and if the surrounding environment is at ', there will be an equal flux of ZP radiation both inward and outward. A similar ''Q ''equilibrium exists at with the ZPE-induced spontaneous emission

Spontaneous emission is the process in which a quantum mechanical system (such as a molecule, an atom or a subatomic particle) transits from an excited energy state to a lower energy state (e.g., its ground state) and emits a quantized amount of ...

of photons (which is more properly called a ''stimulated'' emission in this context). The graph at upper right illustrates the relationship of absolute zero to zero-point energy. The graph also helps in the understanding of how zero-point energy got its name: it is the vibrational energy matter retains at the ''zero-kelvin point''''Derivation of the classical electromagnetic zero-point radiation spectrum via a classical thermodynamic operation involving van der Waals forces''

Daniel C. Cole, Physical Review A, 42 (1990) 1847. Though the atoms in, for instance, a container of liquid helium that was ''precisely'' at absolute zero would still jostle slightly due to zero-point energy, a theoretically perfect heat engine with such helium as one of its working fluids could never transfer any net kinetic energy ( heat energy) to the other working fluid and no thermodynamic work could occur. Temperature is generally expressed in absolute terms when scientifically examining temperature's interrelationships with certain other physical properties of matter such as its volume or pressure (see Gay-Lussac's law), or the wavelength of its emitted

black-body radiation

Black-body radiation is the thermal electromagnetic radiation within, or surrounding, a body in thermodynamic equilibrium with its environment, emitted by a black body (an idealized opaque, non-reflective body). It has a specific, continuous spect ...

. Absolute temperature is also useful when calculating chemical reaction rates (see Arrhenius equation). Furthermore, absolute temperature is typically used in cryogenics and related phenomena like superconductivity

Superconductivity is a set of physical properties observed in certain materials where electrical resistance vanishes and magnetic flux fields are expelled from the material. Any material exhibiting these properties is a superconductor. Unlike ...

, as per the following example usage:

"Conveniently, tantalum's transition temperature (''T'') of 4.4924 kelvin is slightly above the 4.2221 K boiling point of helium."

Boltzmann constant

The Boltzmann constant and its related formulas describe the realm of particle kinetics and velocity vectors whereas ZPE ( zero-point energy) is an energy field that jostles particles in ways described by the mathematics of quantum mechanics. In atomic and molecular collisions in gases, ZPE introduces a degree of '' chaos'', i.e., unpredictability, to rebound kinetics; it is as likely that there will be ''less'' ZPE-induced particle motion after a given collision as ''more''. This random nature of ZPE is why it has no net effect upon either the pressure or volume of any ''bulk quantity'' (a statistically significant quantity of particles) of gases. However, in temperature condensed matter; e.g., solids and liquids, ZPE causes inter-atomic jostling where atoms would otherwise be perfectly stationary. Inasmuch as the real-world effects that ZPE has on substances can vary as one alters a thermodynamic system (for example, due to ZPE, helium won't freeze unless under a pressure of at least 2.5 MPa (25 bar)), ZPE is very much a form of thermal energy and may properly be included when tallying a substance's internal energy.Rankine scale

Though there have been many other temperature scales throughout history, there have been only two scales for measuring thermodynamic temperature where absolute zero is their null point (0): The Kelvin scale and the Rankine scale. Throughout the scientific world where modern measurements are nearly always made using the International System of Units, thermodynamic temperature is measured using the Kelvin scale. The Rankine scale is part of English engineering units in the United States and finds use in certain engineering fields, particularly in legacy reference works. The Rankine scale uses the ''degree Rankine'' (symbol: °R) as its unit, which is the same magnitude as the degree Fahrenheit (symbol: °F). A unit increment of one degree Rankine is precisely 1.8 times smaller in magnitude than one kelvin; thus, to convert a specific temperature on the Kelvin scale to the Rankine scale, , and to convert from a temperature on the Rankine scale to the Kelvin scale, . Consequently, absolute zero is "0" for both scales, but the melting point of water ice (0 °C and 273.15 K) is 491.67 °R. To convert temperature ''intervals'' (a span or difference between two temperatures), one uses the same formulas from the preceding paragraph; for instance, a range of 5 kelvins is precisely equal to a range of 9 degrees Rankine.Modern redefinition of the kelvin

For 65 years, between 1954 and the2019 redefinition of the SI base units

In 2019, four of the seven SI base units specified in the International System of Quantities were redefined in terms of natural physical constants, rather than human artifacts such as the standard kilogram.

Effective 20 May 2019, the 144t ...

, a temperature interval of one kelvin was defined as the difference between the triple point of water and absolute zero. The 1954 resolution by the International Bureau of Weights and Measures (known by the French-language acronym BIPM), plus later resolutions and publications, defined the triple point of water as precisely 273.16 K and acknowledged that it was "common practice" to accept that due to previous conventions (namely, that 0 °C had long been defined as the melting point of water and that the triple point of water had long been experimentally determined to be indistinguishably close to 0.01 °C), the difference between the Celsius scale and Kelvin scale is accepted as 273.15 kelvins; which is to say, 0 °C equals 273.15 kelvins. The net effect of this as well as later resolutions was twofold: 1) they defined absolute zero as precisely 0 K, and 2) they defined that the triple point of special isotopically controlled water called Vienna Standard Mean Ocean Water was precisely 273.16 K and 0.01 °C. One effect of the aforementioned resolutions was that the melting point of water, while ''very'' close to 273.15 K and 0 °C, was not a defining value and was subject to refinement with more precise measurements.

The 1954 BIPM standard did a good job of establishing—within the uncertainties due to isotopic variations between water samples—temperatures around the freezing and triple points of water, but required that ''intermediate values'' between the triple point and absolute zero, as well as extrapolated values from room temperature and beyond, to be experimentally determined via apparatus and procedures in individual labs. This shortcoming was addressed by the International Temperature Scale of 1990

The International Temperature Scale of 1990 (ITS-90) is an equipment calibration standard specified by the International Committee of Weights and Measures (CIPM) for making measurements on the Kelvin and Celsius temperature scales. It is an appro ...

, or ITS90, which defined 13 additional points, from 13.8033 K, to 1,357.77 K. While definitional, ITS90 had—and still has—some challenges, partly because eight of its extrapolated values depend upon the melting or freezing points of metal samples, which must remain exceedingly pure lest their melting or freezing points be affected—usually depressed.

The 2019 redefinition of the SI base units was primarily for the purpose of decoupling much of the SI system's definitional underpinnings from the kilogram

The kilogram (also kilogramme) is the unit of mass in the International System of Units (SI), having the unit symbol kg. It is a widely used measure in science, engineering and commerce worldwide, and is often simply called a kilo colloquially ...

, which was the last physical artifact defining an SI base unit

The SI base units are the standard units of measurement defined by the International System of Units (SI) for the seven base quantities of what is now known as the International System of Quantities: they are notably a basic set from which all ...

(a platinum/iridium cylinder stored under three nested bell jars in a safe located in France) and which had highly questionable stability. The solution required that four physical constants, including the Boltzmann constant, be definitionally fixed.

Assigning the Boltzmann constant a precisely defined value had no practical effect on modern thermometry except for the most exquisitely precise measurements. Before the redefinition, the triple point of water was exactly 273.16 K and 0.01 °C and the Boltzmann constant was experimentally determined to be , where the "(51)" denotes the uncertainty in the two least significant digits (the 03) and equals a relative standard uncertainty of 0.37 ppm. Afterwards, by defining the Boltzmann constant as exactly , the 0.37 ppm uncertainty was transferred to the triple point of water, which became an experimentally determined value of (). That the triple point of water ended up being exceedingly close to 273.16 K after the SI redefinition was no accident; the final value of the Boltzmann constant was determined, in part, through clever experiments with argon and helium that used the triple point of water for their key reference temperature.

Notwithstanding the 2019 redefinition, water triple-point cells continue to serve in modern thermometry as exceedingly precise calibration references at 273.16 K and 0.01 °C. Moreover, the triple point of water remains one of the 14 calibration points comprising ITS90, which spans from the triple point of hydrogen (13.8033 K) to the freezing point of copper (1,357.77 K), which is a nearly hundredfold range of thermodynamic temperature.

Relationship of temperature, motions, conduction, and thermal energy

Nature of kinetic energy, translational motion, and temperature

The thermodynamic temperature of any ''bulk quantity'' of a substance (a statistically significant quantity of particles) is directly proportional to the mean average kinetic energy of a specific kind of particle motion known as ''translational motion''. These simple movements in the three X, Y, and Z–axis dimensions of space means the particles move in the three spatial ''degrees of freedom

Degrees of freedom (often abbreviated df or DOF) refers to the number of independent variables or parameters of a thermodynamic system. In various scientific fields, the word "freedom" is used to describe the limits to which physical movement or ...

''. This particular form of kinetic energy is sometimes referred to as ''kinetic temperature''. Translational motion is but one form of heat energy and is what gives gases not only their temperature, but also their pressure and the vast majority of their volume. This relationship between the temperature, pressure, and volume of gases is established by the ideal gas law's formula and is embodied in the gas laws.

Though the kinetic energy borne exclusively in the three translational degrees of freedom comprise the thermodynamic temperature of a substance, molecules, as can be seen in ''Fig. 3'', can have other degrees of freedom, all of which fall under three categories: bond length, bond angle, and rotational. All three additional categories are not necessarily available to all molecules, and even for molecules that ''can'' experience all three, some can be "frozen out" below a certain temperature. Nonetheless, all those degrees of freedom that are available to the molecules under a particular set of conditions contribute to the specific heat capacity of a substance; which is to say, they increase the amount of heat (kinetic energy) required to raise a given amount of the substance by one kelvin or one degree Celsius.

The relationship of kinetic energy, mass, and velocity is given by the formula ''Ek'' = ''mv''. Accordingly, particles with one unit of mass moving at one unit of velocity have precisely the same kinetic energy, and precisely the same temperature, as those with four times the mass but half the velocity.

The extent to which the kinetic energy of translational motion in a statistically significant collection of atoms or molecules in a gas contributes to the pressure and volume of that gas is a proportional function of thermodynamic temperature as established by the Boltzmann constant (symbol: ''k''B). The Boltzmann constant also relates the thermodynamic temperature of a gas to the mean kinetic energy of an ''individual'' particles’ translational motion as follows:

where:

* is the mean kinetic energy for an individual particle

* ''k''B =

* ''T'' is the thermodynamic temperature of the bulk quantity of the substance

While the Boltzmann constant is useful for finding the mean kinetic energy in a sample of particles, it is important to note that even when a substance is isolated and in thermodynamic equilibrium (all parts are at a uniform temperature and no heat is going into or out of it), the translational motions of individual atoms and molecules occurs across a wide range of speeds (see animation in '' Fig. 1 ''above). At any one instant, the proportion of particles moving at a given speed within this range is determined by probability as described by the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution. The graph shown here in ''Fig. 2'' shows the speed distribution of 5500 K helium atoms. They have a ''most probable'' speed of 4.780 km/s (0.2092 s/km). However, a certain proportion of atoms at any given instant are moving faster while others are moving relatively slowly; some are momentarily at a virtual standstill (off the ''x''–axis to the right). This graph uses ''inverse speed'' for its ''x''–axis so the shape of the curve can easily be compared to the curves in '' Fig. 5'' below. In both graphs, zero on the ''x''–axis represents infinite temperature. Additionally, the ''x'' and ''y''–axis on both graphs are scaled proportionally.

High speeds of translational motion

Although very specialized laboratory equipment is required to directly detect translational motions, the resultant collisions by atoms or molecules with small particles suspended in afluid

In physics, a fluid is a liquid, gas, or other material that continuously deforms (''flows'') under an applied shear stress, or external force. They have zero shear modulus, or, in simpler terms, are substances which cannot resist any shear ...

produces Brownian motion that can be seen with an ordinary microscope. The translational motions of elementary particles are ''very'' fast and temperatures close to absolute zero

Absolute zero is the lowest limit of the thermodynamic temperature scale, a state at which the enthalpy and entropy of a cooled ideal gas reach their minimum value, taken as zero kelvin. The fundamental particles of nature have minimum vibration ...

are required to directly observe them. For instance, when scientists at the NIST

The National Institute of Standards and Technology (NIST) is an agency of the United States Department of Commerce whose mission is to promote American innovation and industrial competitiveness. NIST's activities are organized into physical sci ...

achieved a record-setting cold temperature of 700 nK (billionths of a kelvin) in 1994, they used optical lattice laser equipment to adiabatically

Adiabatic (from ''Gr.'' ἀ ''negative'' + διάβασις ''passage; transference'') refers to any process that occurs without heat transfer. This concept is used in many areas of physics and engineering. Notable examples are listed below.

A ...

cool cesium atoms. They then turned off the entrapment lasers and directly measured atom velocities of 7 mm per second to in order to calculate their temperature. Formulas for calculating the velocity and speed of translational motion are given in the following footnote.The rate of translational motion of atoms and molecules is calculated based on thermodynamic temperature as follows:

where

* is the vector-isolated mean velocity of translational particle motion in m/s

*''k''B ( Boltzmann constant) =

*''T'' is the thermodynamic temperature in kelvins

*''m'' is the molecular mass of substance in kg/particle

In the above formula, molecular mass, ''m'', in kg/particle is the quotient of a substance's molar mass (also known as ''atomic weight'', '' atomic mass'', ''relative atomic mass'', and '' unified atomic mass units'') in g/ mol or daltons divided by (which is the Avogadro constant times one thousand). For diatomic

Diatomic molecules () are molecules composed of only two atoms, of the same or different chemical elements. If a diatomic molecule consists of two atoms of the same element, such as hydrogen () or oxygen (), then it is said to be homonuclear. Ot ...

molecules such as H2, N2, and O2, multiply atomic weight by two before plugging it into the above formula.

The mean ''speed'' (not vector-isolated velocity) of an atom or molecule along any arbitrary path is calculated as follows:

where is the mean speed of translational particle motion in m/s.

Note that the mean energy of the translational motions of a substance's constituent particles correlates to their mean ''speed'', not velocity. Thus, substituting for ''v'' in the classic formula for kinetic energy, produces precisely the same value as does (as shown in the section titled '' The nature of kinetic energy, translational motion, and temperature)''. Note too that the Boltzmann constant and its related formulas establish that absolute zero is the point of both zero kinetic energy of particle motion and zero kinetic velocity (see also '' Note 1'' above).

It is neither difficult to imagine atomic motions due to kinetic temperature, nor distinguish between such motions and those due to zero-point energy. Consider the following hypothetical thought experiment, as illustrated in ''Fig. 2.5'' at left, with an atom that is exceedingly close to absolute zero. Imagine peering through a common optical microscope set to 400 power, which is about the maximum practical magnification for optical microscopes. Such microscopes generally provide fields of view a bit over 0.4 mm in diameter. At the center of the field of view is a single levitated argon atom (argon comprises about 0.93% of air) that is illuminated and glowing against a dark backdrop. If this argon atom was at a beyond-record-setting ''one-trillionth'' of a kelvin above absolute zero, and was moving perpendicular to the field of view towards the right, it would require 13.9 seconds to move from the center of the image to the 200-micron tick mark; this travel distance is about the same as the width of the period at the end of this sentence on modern computer monitors. As the argon atom slowly moved, the positional jitter due to zero-point energy would be much less than the 200-nanometer (0.0002 mm) resolution of an optical microscope. Importantly, the atom's translational velocity of 14.43 microns per second constitutes all its retained kinetic energy due to not being precisely at absolute zero. Were the atom ''precisely'' at absolute zero, imperceptible jostling due to zero-point energy would cause it to very slightly wander, but the atom would perpetually be located, on average, at the same spot within the field of view. This is analogous to a boat that has had its motor turned off and is now bobbing slightly in relatively calm and windless ocean waters; even though the boat randomly drifts to and fro, it stays in the same spot in the long term and makes no headway through the water. Accordingly, an atom that was precisely at absolute zero would not be "motionless", and yet, a statistically significant collection of such atoms would have zero net kinetic energy available to transfer to any other collection of atoms. This is because regardless of the kinetic temperature of the second collection of atoms, they too experience the effects of zero-point energy. Such are the consequences of

It is neither difficult to imagine atomic motions due to kinetic temperature, nor distinguish between such motions and those due to zero-point energy. Consider the following hypothetical thought experiment, as illustrated in ''Fig. 2.5'' at left, with an atom that is exceedingly close to absolute zero. Imagine peering through a common optical microscope set to 400 power, which is about the maximum practical magnification for optical microscopes. Such microscopes generally provide fields of view a bit over 0.4 mm in diameter. At the center of the field of view is a single levitated argon atom (argon comprises about 0.93% of air) that is illuminated and glowing against a dark backdrop. If this argon atom was at a beyond-record-setting ''one-trillionth'' of a kelvin above absolute zero, and was moving perpendicular to the field of view towards the right, it would require 13.9 seconds to move from the center of the image to the 200-micron tick mark; this travel distance is about the same as the width of the period at the end of this sentence on modern computer monitors. As the argon atom slowly moved, the positional jitter due to zero-point energy would be much less than the 200-nanometer (0.0002 mm) resolution of an optical microscope. Importantly, the atom's translational velocity of 14.43 microns per second constitutes all its retained kinetic energy due to not being precisely at absolute zero. Were the atom ''precisely'' at absolute zero, imperceptible jostling due to zero-point energy would cause it to very slightly wander, but the atom would perpetually be located, on average, at the same spot within the field of view. This is analogous to a boat that has had its motor turned off and is now bobbing slightly in relatively calm and windless ocean waters; even though the boat randomly drifts to and fro, it stays in the same spot in the long term and makes no headway through the water. Accordingly, an atom that was precisely at absolute zero would not be "motionless", and yet, a statistically significant collection of such atoms would have zero net kinetic energy available to transfer to any other collection of atoms. This is because regardless of the kinetic temperature of the second collection of atoms, they too experience the effects of zero-point energy. Such are the consequences of statistical mechanics

In physics, statistical mechanics is a mathematical framework that applies statistical methods and probability theory to large assemblies of microscopic entities. It does not assume or postulate any natural laws, but explains the macroscopic be ...

and the nature of thermodynamics.

Internal motions of molecules and internal energy

As mentioned above, there are other ways molecules can jiggle besides the three translational degrees of freedom that imbue substances with their kinetic temperature. As can be seen in the animation at right, molecules are complex objects; they are a population of atoms and thermal agitation can strain their internal chemical bonds in three different ways: via rotation, bond length, and bond angle movements; these are all types of ''internal degrees of freedom''. This makes molecules distinct from '' monatomic'' substances (consisting of individual atoms) like the noble gases helium and argon, which have only the three translational degrees of freedom (the X, Y, and Z axis). Kinetic energy is stored in molecules' internal degrees of freedom, which gives them an ''internal temperature''. Even though these motions are called "internal", the external portions of molecules still move—rather like the jiggling of a stationary water balloon. This permits the two-way exchange of kinetic energy between internal motions and translational motions with each molecular collision. Accordingly, as internal energy is removed from molecules, both their kinetic temperature (the kinetic energy of translational motion) and their internal temperature simultaneously diminish in equal proportions. This phenomenon is described by the equipartition theorem, which states that for any bulk quantity of a substance in equilibrium, the kinetic energy of particle motion is evenly distributed among all the active degrees of freedom available to the particles. Since the internal temperature of molecules are usually equal to their kinetic temperature, the distinction is usually of interest only in the detailed study of non- local thermodynamic equilibrium (LTE) phenomena such as combustion, thesublimation

Sublimation or sublimate may refer to:

* ''Sublimation'' (album), by Canvas Solaris, 2004

* Sublimation (phase transition), directly from the solid to the gas phase

* Sublimation (psychology), a mature type of defense mechanism

* Sublimate of mer ...

of solids, and the diffusion of hot gases in a partial vacuum.

The kinetic energy stored internally in molecules causes substances to contain more heat energy at any given temperature and to absorb additional internal energy for a given temperature increase. This is because any kinetic energy that is, at a given instant, bound in internal motions, is not contributing to the molecules' translational motions at that same instant . This extra kinetic energy simply increases the amount of internal energy that substance absorbs for a given temperature rise. This property is known as a substance's specific heat capacity.

Different molecules absorb different amounts of internal energy for each incremental increase in temperature; that is, they have different specific heat capacities. High specific heat capacity arises, in part, because certain substances’ molecules possess more internal degrees of freedom than others do. For instance, room-temperature nitrogen, which is a diatomic

Diatomic molecules () are molecules composed of only two atoms, of the same or different chemical elements. If a diatomic molecule consists of two atoms of the same element, such as hydrogen () or oxygen (), then it is said to be homonuclear. Ot ...

molecule, has ''five'' active degrees of freedom: the three comprising translational motion plus two rotational degrees of freedom internally. Not surprisingly, in accordance with the equipartition theorem, nitrogen has five-thirds the specific heat capacity per mole (a specific number of molecules) as do the monatomic gases. Another example is gasoline (see table showing its specific heat capacity). Gasoline can absorb a large amount of heat energy per mole with only a modest temperature change because each molecule comprises an average of 21 atoms and therefore has many internal degrees of freedom. Even larger, more complex molecules can have dozens of internal degrees of freedom.

Diffusion of thermal energy: entropy, phonons, and mobile conduction electrons

''Heat conduction

Conduction is the process by which heat is transferred from the hotter end to the colder end of an object. The ability of the object to conduct heat is known as its ''thermal conductivity'', and is denoted .

Heat spontaneously flows along a te ...

'' is the diffusion of thermal energy from hot parts of a system to cold parts. A system can be either a single bulk entity or a plurality of discrete bulk entities. The term ''bulk'' in this context means a statistically significant quantity of particles (which can be a microscopic amount). Whenever thermal energy diffuses within an isolated system, temperature differences within the system decrease (and entropy increases).

One particular heat conduction mechanism occurs when translational motion, the particle motion underlying temperature, transfers momentum

In Newtonian mechanics, momentum (more specifically linear momentum or translational momentum) is the product of the mass and velocity of an object. It is a vector quantity, possessing a magnitude and a direction. If is an object's mass an ...

from particle to particle in collisions. In gases, these translational motions are of the nature shown above in '' Fig. 1''. As can be seen in that animation, not only does momentum (heat) diffuse throughout the volume of the gas through serial collisions, but entire molecules or atoms can move forward into new territory, bringing their kinetic energy with them. Consequently, temperature differences equalize throughout gases very quickly—especially for light atoms or molecules; convection speeds this process even more.

Translational motion in ''solids'', however, takes the form of ''phonon

In physics, a phonon is a collective excitation in a periodic, Elasticity (physics), elastic arrangement of atoms or molecules in condensed matter physics, condensed matter, specifically in solids and some liquids. A type of quasiparticle, a phon ...

s'' (see ''Fig. 4'' at right). Phonons are constrained, quantized wave packets that travel at the speed of sound of a given substance. The manner in which phonons interact within a solid determines a variety of its properties, including its thermal conductivity. In electrically insulating solids, phonon-based heat conduction is ''usually'' inefficient and such solids are considered ''thermal insulators'' (such as glass, plastic, rubber, ceramic, and rock). This is because in solids, atoms and molecules are locked into place relative to their neighbors and are not free to roam.

Metals however, are not restricted to only phonon-based heat conduction. Thermal energy conducts through metals extraordinarily quickly because instead of direct molecule-to-molecule collisions, the vast majority of thermal energy is mediated via very light, mobile ''conduction electrons''. This is why there is a near-perfect correlation between metals' thermal conductivity and their electrical conductivity

Electrical resistivity (also called specific electrical resistance or volume resistivity) is a fundamental property of a material that measures how strongly it resists electric current. A low resistivity indicates a material that readily allow ...

. Conduction electrons imbue metals with their extraordinary conductivity because they are '' delocalized'' (i.e., not tied to a specific atom) and behave rather like a sort of quantum gas due to the effects of '' zero-point energy'' (for more on ZPE, see '' Note 1'' below). Furthermore, electrons are relatively light with a rest mass only that of a proton

A proton is a stable subatomic particle, symbol , H+, or 1H+ with a positive electric charge of +1 ''e'' elementary charge. Its mass is slightly less than that of a neutron and 1,836 times the mass of an electron (the proton–electron mass ...

. This is about the same ratio as a .22 Short

.22 Short is a variety of .22 caliber (5.6 mm) rimfire ammunition. Developed in 1857 for the first Smith & Wesson revolver, the .22 rimfire was the first American metallic cartridge. The original loading was a bullet and of black powd ...

bullet (29 grains or 1.88 g) compared to the rifle that shoots it. As Isaac Newton wrote with his third law of motion

Third or 3rd may refer to:

Numbers

* 3rd, the ordinal form of the cardinal number 3

* , a fraction of one third

* 1⁄60 of a ''second'', or 1⁄3600 of a ''minute''

Places

* 3rd Street (disambiguation)

* Third Avenue (disambiguation)

* High ...

,

However, a bullet accelerates faster than a rifle given an equal force. Since kinetic energy increases as the square of velocity, nearly all the kinetic energy goes into the bullet, not the rifle, even though both experience the same force from the expanding propellant gases. In the same manner, because they are much less massive, thermal energy is readily borne by mobile conduction electrons. Additionally, because they're delocalized and ''very'' fast, kinetic thermal energy conducts extremely quickly through metals with abundant conduction electrons.

Diffusion of thermal energy: black-body radiation

Thermal radiation is a byproduct of the collisions arising from various vibrational motions of atoms. These collisions cause the electrons of the atoms to emit thermal photons (known asblack-body radiation

Black-body radiation is the thermal electromagnetic radiation within, or surrounding, a body in thermodynamic equilibrium with its environment, emitted by a black body (an idealized opaque, non-reflective body). It has a specific, continuous spect ...

). Photons are emitted anytime an electric charge is accelerated (as happens when electron clouds of two atoms collide). Even ''individual molecules'' with internal temperatures greater than absolute zero also emit black-body radiation from their atoms. In any bulk quantity of a substance at equilibrium, black-body photons are emitted across a range of wavelengths in a spectrum that has a bell curve-like shape called a Planck curve (see graph in ''Fig. 5'' at right). The top of a Planck curve ( the peak emittance wavelength) is located in a particular part of the electromagnetic spectrum depending on the temperature of the black-body. Substances at extreme cryogenic

In physics, cryogenics is the production and behaviour of materials at very low temperatures.

The 13th IIR International Congress of Refrigeration (held in Washington DC in 1971) endorsed a universal definition of “cryogenics” and “cr ...

temperatures emit at long radio wavelengths whereas extremely hot temperatures produce short gamma rays (see '' Table of common temperatures'').

Black-body radiation diffuses thermal energy throughout a substance as the photons are absorbed by neighboring atoms, transferring momentum in the process. Black-body photons also easily escape from a substance and can be absorbed by the ambient environment; kinetic energy is lost in the process.

As established by the Stefan–Boltzmann law, the intensity of black-body radiation increases as the fourth power of absolute temperature. Thus, a black-body at 824 K (just short of glowing dull red) emits ''60 times'' the radiant power as it does at 296 K (room temperature). This is why one can so easily feel the radiant heat from hot objects at a distance. At higher temperatures, such as those found in an incandescent lamp

An incandescent light bulb, incandescent lamp or incandescent light globe is an electric light with a wire filament heated until it glows. The filament is enclosed in a glass bulb with a vacuum or inert gas to protect the filament from oxid ...

, black-body radiation can be the principal mechanism by which thermal energy escapes a system.

Table of thermodynamic temperatures

The table below shows various points on the thermodynamic scale, in order of increasing temperature.Heat of phase changes

The kinetic energy of particle motion is just one contributor to the total thermal energy in a substance; another is '' phase transitions'', which are thepotential energy

In physics, potential energy is the energy held by an object because of its position relative to other objects, stresses within itself, its electric charge, or other factors.

Common types of potential energy include the gravitational potentia ...

of molecular bonds that can form in a substance as it cools (such as during condensing and freezing). The thermal energy required for a phase transition is called '' latent heat''. This phenomenon may more easily be grasped by considering it in the reverse direction: latent heat is the energy required to ''break'' chemical bonds (such as during evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when humidi ...

and melting). Almost everyone is familiar with the effects of phase transitions; for instance, steam

Steam is a substance containing water in the gas phase, and sometimes also an aerosol of liquid water droplets, or air. This may occur due to evaporation or due to boiling, where heat is applied until water reaches the enthalpy of vaporization ...

at 100 °C can cause severe burns much faster than the 100 °C air from a hair dryer. This occurs because a large amount of latent heat is liberated as steam condenses into liquid water on the skin.

Even though thermal energy is liberated or absorbed during phase transitions, pure chemical elements, compounds, and eutectic alloys ''exhibit no temperature change whatsoever'' while they undergo them (see ''Fig. 7'', below right). Consider one particular type of phase transition: melting. When a solid is melting, crystal lattice

In geometry and crystallography, a Bravais lattice, named after , is an infinite array of discrete points generated by a set of discrete translation operations described in three dimensional space by

: \mathbf = n_1 \mathbf_1 + n_2 \mathbf_2 + n ...

chemical bonds are being broken apart; the substance is transitioning from what is known as a ''more ordered state'' to a ''less ordered state''. In ''Fig. 7'', the melting of ice is shown within the lower left box heading from blue to green.

At one specific thermodynamic point, the melting point (which is 0 °C across a wide pressure range in the case of water), all the atoms or molecules are, on average, at the maximum energy threshold their chemical bonds can withstand without breaking away from the lattice. Chemical bonds are all-or-nothing forces: they either hold fast, or break; there is no in-between state. Consequently, when a substance is at its melting point, every joule of added thermal energy only breaks the bonds of a specific quantity of its atoms or molecules, converting them into a liquid of precisely the same temperature; no kinetic energy is added to translational motion (which is what gives substances their temperature). The effect is rather like

At one specific thermodynamic point, the melting point (which is 0 °C across a wide pressure range in the case of water), all the atoms or molecules are, on average, at the maximum energy threshold their chemical bonds can withstand without breaking away from the lattice. Chemical bonds are all-or-nothing forces: they either hold fast, or break; there is no in-between state. Consequently, when a substance is at its melting point, every joule of added thermal energy only breaks the bonds of a specific quantity of its atoms or molecules, converting them into a liquid of precisely the same temperature; no kinetic energy is added to translational motion (which is what gives substances their temperature). The effect is rather like popcorn

Popcorn (also called popped corn, popcorns or pop-corn) is a variety of corn kernel which expands and puffs up when heated; the same names also refer to the foodstuff produced by the expansion.

A popcorn kernel's strong hull contains the se ...

: at a certain temperature, additional thermal energy can't make the kernels any hotter until the transition (popping) is complete. If the process is reversed (as in the freezing of a liquid), thermal energy must be removed from a substance.

As stated above, the thermal energy required for a phase transition is called ''latent heat''. In the specific cases of melting and freezing, it's called '' enthalpy of fusion'' or ''heat of fusion''. If the molecular bonds in a crystal lattice are strong, the heat of fusion can be relatively great, typically in the range of 6 to 30 kJ per mole for water and most of the metallic elements. If the substance is one of the monatomic gases, (which have little tendency to form molecular bonds) the heat of fusion is more modest, ranging from 0.021 to 2.3 kJ per mole. Relatively speaking, phase transitions can be truly energetic events. To completely melt ice at 0 °C into water at 0 °C, one must add roughly 80 times the thermal energy as is required to increase the temperature of the same mass of liquid water by one degree Celsius. The metals' ratios are even greater, typically in the range of 400 to 1200 times. And the phase transition of boiling

Boiling is the rapid vaporization of a liquid, which occurs when a liquid is heated to its boiling point, the temperature at which the vapour pressure of the liquid is equal to the pressure exerted on the liquid by the surrounding atmosphere. Th ...

is much more energetic than freezing. For instance, the energy required to completely boil or vaporize water (what is known as '' enthalpy of vaporization'') is roughly ''540 times'' that required for a one-degree increase.

Water's sizable enthalpy of vaporization is why one's skin can be burned so quickly as steam condenses on it (heading from red to green in ''Fig. 7'' above); water vapors (gas phase) are liquefied on the skin with releasing a large amount of energy (enthalpy) to the environment including the skin, resulting in skin damage. In the opposite direction, this is why one's skin feels cool as liquid water on it evaporates (a process that occurs at a sub-ambient wet-bulb temperature

The wet-bulb temperature (WBT) is the temperature read by a thermometer covered in water-soaked (water at ambient temperature) cloth (a wet-bulb thermometer) over which air is passed. At 100% relative humidity, the wet-bulb temperature is equal ...

that is dependent on relative humidity); the water evaporation on the skin takes a large amount of energy from the environment including the skin, reducing the skin temperature. Water's highly energetic enthalpy of vaporization is also an important factor underlying why ''solar pool covers'' (floating, insulated blankets that cover swimming pool

A swimming pool, swimming bath, wading pool, paddling pool, or simply pool, is a structure designed to hold water to enable Human swimming, swimming or other leisure activities. Pools can be built into the ground (in-ground pools) or built ...

s when the pools are not in use) are so effective at reducing heating costs: they prevent evaporation. (In other words, taking energy from water when it is evaporated is limited.) For instance, the evaporation of just 20 mm of water from a 1.29-meter-deep pool chills its water 8.4 degrees Celsius (15.1 °F).

Internal energy

The total energy of all translational and internal particle motions, including that of conduction electrons, plus the potential energy of phase changes, plus zero-point energy of a substance comprise the ''internal energy

The internal energy of a thermodynamic system is the total energy contained within it. It is the energy necessary to create or prepare the system in its given internal state, and includes the contributions of potential energy and internal kinet ...

'' of it.

Internal energy at absolute zero