Karol Kuryluk on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Karol Kuryluk (27 October 1910 – 9 December 1967) was a Polish

Karol Kuryluk (27 October 1910 – 9 December 1967) was a Polish

Karol Kuryluk

– his activity to save Jews' lives during the

Image:ZbarazOgolnyWidokOdStronyZaluza.jpg, A postcard showing a general view of the town of Zbaraż, ca 1925.

Image:ZbarazRynekZbarazMainSquarePostcard.jpg, A postcard showing the main square in Zbaraż, ca. 1925.

Image:AutowzbarazuKarolKurylukOk1930.jpg, Karol Kuryluk, second from the right, with his younger siblings and friends who came to visit him in Zbaraz, 1930.

Image:Odrodzenie1945.jpg, The editorial office of "Odrodzenie", in the middle Maria Dąbrowska, with Karol Kuryluk on her left, and Tadeusz Breza, Cracow, 1946.

Image:KarolKurylukWarsaw1947.jpg, Karol Kuryluk clearing the rubble in postwar Warsaw, 1948.

Image:KarolKurylukWithKruschev.jpg, Polish ambassador to Austria Karol Kuryluk being introduced to

Goldi,'' Warsaw, 2004

www.culture.pl/en/culture/artykuly/os_kuryluk_ewa

www.marekhlasko.republika.pl/03_artykuly/Kuryluk.pdf

Museum of the History of Polish Jews’ web page about Karol Kuryluk

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kuryluk, Karol 1910 births 1967 deaths Ambassadors of Poland to Austria Polish politicians Polish Righteous Among the Nations Polish male writers People from Zbarazh People from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria 20th-century Polish journalists

Karol Kuryluk (27 October 1910 – 9 December 1967) was a Polish

Karol Kuryluk (27 October 1910 – 9 December 1967) was a Polish journalist

A journalist is an individual that collects/gathers information in form of text, audio, or pictures, processes them into a news-worthy form, and disseminates it to the public. The act or process mainly done by the journalist is called journalism ...

, editor

Editing is the process of selecting and preparing written, photographic, visual, audible, or cinematic material used by a person or an entity to convey a message or information. The editing process can involve correction, condensation, orga ...

, activist

Activism (or Advocacy) consists of efforts to promote, impede, direct or intervene in social, political, economic or environmental reform with the desire to make changes in society toward a perceived greater good. Forms of activism range fro ...

, politician

A politician is a person active in party politics, or a person holding or seeking an elected office in government. Politicians propose, support, reject and create laws that govern the land and by an extension of its people. Broadly speaking, a ...

and diplomat

A diplomat (from grc, δίπλωμα; romanized ''diploma'') is a person appointed by a state or an intergovernmental institution such as the United Nations or the European Union to conduct diplomacy with one or more other states or internati ...

. In 2002, he was honored by Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

for saving Jews in the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

.

Biography

Kuryluk was born on 27 October 1910 inZbaraż

Zbarazh ( uk, Збараж, pl, Zbaraż, yi, זבאריזש, Zbarizh) is a city in Ternopil Raion of Ternopil Oblast (province) of western Ukraine. It is located in the historic region of Galicia. Zbarazh hosts the administration of Zbarazh ur ...

(Zbarazh), a small town in Galicia, the eastern province of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

(after World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

part of Poland

Poland, officially the Republic of Poland, is a country in Central Europe. It is divided into 16 administrative provinces called voivodeships, covering an area of . Poland has a population of over 38 million and is the fifth-most populous ...

, today in Ukraine

Ukraine ( uk, Україна, Ukraïna, ) is a country in Eastern Europe. It is the second-largest European country after Russia, which it borders to the east and northeast. Ukraine covers approximately . Prior to the ongoing Russian inv ...

), and died in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

. He was the eldest son of Franciszek Kuryluk, a mason, and Łucja, née Pańczyszak. He had four brothers (two of them died in early childhood) and five sisters.

In 1930, after finishing high school

A secondary school describes an institution that provides secondary education and also usually includes the building where this takes place. Some secondary schools provide both '' lower secondary education'' (ages 11 to 14) and ''upper seconda ...

in his native town, Kuryluk received a small scholarship to study Polish language

Polish (Polish: ''język polski'', , ''polszczyzna'' or simply ''polski'', ) is a West Slavic language of the Lechitic group written in the Latin script. It is spoken primarily in Poland and serves as the native language of the Poles. In a ...

at the University of Lviv

The University of Lviv ( uk, Львівський університет, Lvivskyi universytet; pl, Uniwersytet Lwowski; german: Universität Lemberg, briefly known as the ''Theresianum'' in the early 19th century), presently the Ivan Franko Na ...

in the former capital of the Austro-Hungarian province of Galicia and a multicultural metropolis (Poles, Jews, Ukrainians, Armenians, Belarusians, Germans and Tatars). He was multilingual (Polish, Ukrainian, Russian and German), and during his studies he supported himself and helped his family back home by giving private lessons.

In 1931, Kuryluk met the writer and philanthropist Halina Górska and became involved in her social care

Social work is an academic discipline and practice-based profession concerned with meeting the basic needs of individuals, families, groups, communities, and society as a whole to enhance their individual and collective well-being. Social work ...

project Akcja Błękitnych (Action of the Blue Knights), distributing food and clothing to slum children and helping to run shelters for homeless boys. At the University he protested against the "bench ghetto", set up by the nationalists to separate Poles and Jews in the lecture hall

A lecture hall (or lecture theatre) is a large room used for instruction, typically at a college or university. Unlike a traditional classroom with a capacity normally between one and fifty, the capacity of lecture halls is usually measured i ...

s, and he sided with Jewish and Ukrainian students who were harassed and beaten up by the Endecja

National Democracy ( pl, Narodowa Demokracja, also known from its abbreviation ND as ''Endecja''; ) was a Polish political movement active from the second half of the 19th century under the foreign partitions of the country until the end of ...

gangs.

He married Miriam Kohany, a poet, writer and translator who during the war changed her name to Maria Grabowska and published under the name of Maria Kuryluk. They had two children, Ewa Kuryluk, an artist and writer, and Piotr Kuryluk, a translator.

In September 1967, Kuryluk suffered a heart attack

A myocardial infarction (MI), commonly known as a heart attack, occurs when blood flow decreases or stops to the coronary artery of the heart, causing damage to the heart muscle. The most common symptom is chest pain or discomfort which may tr ...

. He flew to a book fair in Budapest against his doctor's advice and died there on 9 December 1967.

Kuryluk is buried together with his wife and son at the Powązki Military Cemetery

Powązki Military Cemetery (; pl, Cmentarz Wojskowy na Powązkach) is an old military cemetery located in the Żoliborz district, western part of Warsaw, Poland. The cemetery is often confused with the older Powązki Cemetery, known colloquiall ...

in a tomb designed by Ewa Kuryluk.

Literary career

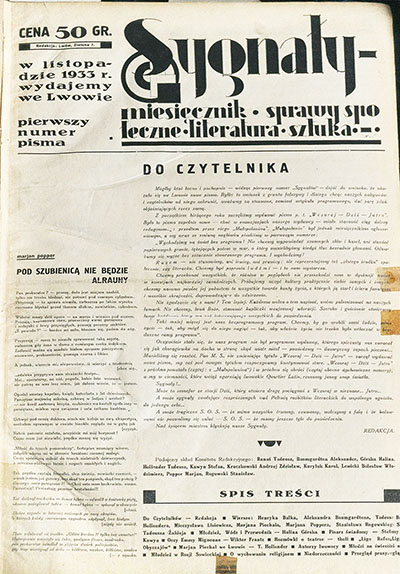

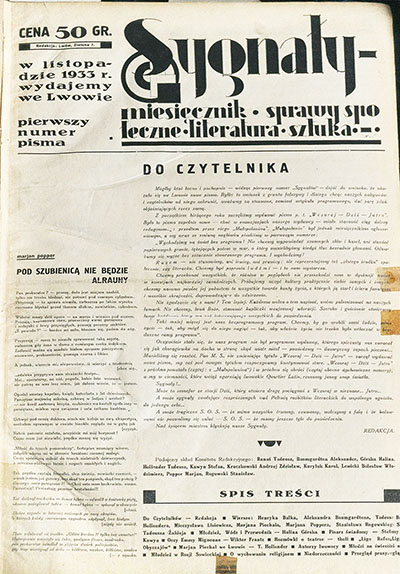

In 1933 Kuryluk founded the cultural periodical '' Sygnały'' (''Signals'' Magazine) with the poetTadeusz Hollender

Tadeusz Hollender (30 May 1910 – 31 May 1943) was a Polish poet, translator and humorist. During World War II, he wrote satirical articles and poems in underground press, for that he was arrested by the German Gestapo and executed in May in the ...

and became its editor-in-chief. He called upon the young literary talent in the city (Erwin Axer

Erwin Axer (1 January 1917 – 5 August 2012) was a Polish theatre director, writer and university professor. A long-time head of Teatr Współczesny (Contemporary Theatre) in Warsaw, he also staged numerous plays abroad, notably in German-speakin ...

, Stanisław Jerzy Lec

Stanisław Jerzy Lec (; 6 March 1909 – 7 May 1966), born Baron Stanisław Jerzy de Tusch-Letz, was a Poles, Polish aphorism, aphorist and poetry, poet. Often mentioned among the greatest writers of Military occupations by the Soviet Union, post- ...

, Czesław Miłosz, Mirosław Żuławski

Mirosław Żuławski (16 January 1913 – 17 February 1995) was a Polish writer, prosaist, diplomat and screenwriter. He was father of film director, Andrzej Żuławski.

Biography

Mirosław Żuławski was born in Nisko. He graduated in law and d ...

), won over established writers from all over the country ( Maria Dąbrowska, Bruno Schulz

Bruno Schulz (12 July 1892 – 19 November 1942) was a Polish writer, fine artist, literary critic and art teacher. He is regarded as one of the great Polish-language prose stylists of the 20th century. In 1938, he was awarded the Polish Academy ...

, Leopold Staff

Leopold Henryk Staff (November 14, 1878 – May 31, 1957) was a Polish poet; an artist of European modernism twice granted the Degree of Doctor honoris causa by universities in Warsaw and in Kraków. He was also nominated for the Nobel Prize i ...

, Andrzej Strug

Andrzej Strug, real name Tadeusz (or Stefan) Gałecki (sources vary; 28 November 1871/1873 in Lublin – 9 December 1937 in Warsaw) was a Polish socialist politician, publicist and activist for Poland's independence. He was also a freemas ...

, Julian Tuwim

Julian Tuwim (13 September 1894 – 27 December 1953), known also under the pseudonym "Oldlen" as a lyricist, was a Polish poet, born in Łódź, then part of the Russian Partition. He was educated in Łódź and in Warsaw where he studied la ...

), and published translations of writings by foreign authors ( Appolinaire, Henri Barbusse

Henri Barbusse (; 17 May 1873 – 30 August 1935) was a French novelist and a member of the French Communist Party. He was a lifelong friend of Albert Einstein.

Life

The son of a French father and an English mother, Barbusse was born in Asnièr ...

, André Malraux

Georges André Malraux ( , ; 3 November 1901 – 23 November 1976) was a French novelist, art theorist, and minister of cultural affairs. Malraux's novel ''La Condition Humaine'' (Man's Fate) (1933) won the Prix Goncourt. He was appointed by P ...

, Carl von Ossietzky

Carl von Ossietzky (; 3 October 1889 – 4 May 1938) was a German journalist and pacifist. He was the recipient of the 1935 Nobel Peace Prize for his work in exposing the clandestine German re-armament.

As editor-in-chief of the magazine ''Die ...

, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British mathematician, philosopher, logician, and public intellectual. He had a considerable influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, linguistics, ...

, Upton Sinclair

Upton Beall Sinclair Jr. (September 20, 1878 – November 25, 1968) was an American writer, muckraker, political activist and the 1934 Democratic Party nominee for governor of California who wrote nearly 100 books and other works in seve ...

, Paul Valéry

Ambroise Paul Toussaint Jules Valéry (; 30 October 1871 – 20 July 1945) was a French poet, essayist, and philosopher. In addition to his poetry and fiction (drama and dialogues), his interests included aphorisms on art, history, letters, mus ...

). Special issues were dedicated to Jewish, Ukrainian and Belorussian culture, and to the city of Lwów.

''Signals'' promoted the work of contemporary Polish artists (Henryk Gotlib

Henryk Gotlib (10 January 1890 – 30 December 1966) was a Polish painter, draughtsman, printmaker, and writer, who settled in England during World War II and made a significant contribution to modern British art. He was profoundly influenced ...

, Bruno Schulz

Bruno Schulz (12 July 1892 – 19 November 1942) was a Polish writer, fine artist, literary critic and art teacher. He is regarded as one of the great Polish-language prose stylists of the 20th century. In 1938, he was awarded the Polish Academy ...

, Zygmunt Waliszewski

Zygmunt Waliszewski (1897–1936) was a Polish painter, a member of the Kapist movement.

Biography

Waliszewski was born in Saint Petersburg to the Polish family of an engineer. In 1907 his parents moved to Tbilisi where Waliszewski spent h ...

) and avant-garde photographers (Otto Hahn, Mieczysław Szczuka), and popularized modern European art (van Gogh

Vincent Willem van Gogh (; 30 March 185329 July 1890) was a Dutch Post-Impressionist painter who posthumously became one of the most famous and influential figures in Western art history. In a decade, he created about 2,100 artworks, inclu ...

, Gauguin

Eugène Henri Paul Gauguin (, ; ; 7 June 1848 – 8 May 1903) was a French Post-Impressionist artist. Unappreciated until after his death, Gauguin is now recognized for his experimental use of colour and Synthetism, Synthetist style that were d ...

, Archipenko Arkhypenko ( uk, Архипенко), also transliterated as Arkhipenko, Archipenko, is a Ukrainian-language family name of patronymic derivation from the Slavic first name Arkhyp/Arkhip (). The Belarusian-language version is Arkhipienka.

The sur ...

, Max Ernst

Max Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German (naturalised American in 1948 and French in 1958) painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and Surrealism ...

). A group of gifted graphic artists and caricaturists (K. Baraniecki, F. Kleinmann, Eryk Lipiński

Eryk Lipiński (; 12 July 1908, Kraków - 27 September 1991) was a Polish artist. Satirist, caricaturist, essayist, he has designed posters, written plays and sketches for cabarets, as well as written books on related subjects.

Biography

Eryk ...

, Franciszek Parecki) collaborated with the magazine, which was famous for its biting humor and merciless derision of Hitler, Mussolini, Franco and the Polish anti-Semites, but also of Stalin. By mid-thirties ''Signals'' had become a leading periodical of the leftist Polish intelligentsia.

In 1938, an armed gang of ONR (National Radical Camp

The National Radical Camp ( pl, Obóz Narodowo-Radykalny, ONR) refers to at least three groups that are fascist, far-right, and ultranationalist Polish organisations with doctrines stemming from pre-World War II nationalist ideology.

The cur ...

) raided the editorial office and Kuryluk just barely escaped being killed. Yet he managed to continue publishing ''Signals'', in spite of financial hardship, ongoing censorship

Censorship is the suppression of speech, public communication, or other information. This may be done on the basis that such material is considered objectionable, harmful, sensitive, or "inconvenient". Censorship can be conducted by governments ...

and vicious political attacks, until the outbreak of World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The last issue came out in August 1939. In September 1939, after the Soviet annexation of Lwów

Lviv ( uk, Львів) is the largest city in western Ukraine, and the seventh-largest in Ukraine, with a population of . It serves as the administrative centre of Lviv Oblast and Lviv Raion, and is one of the main cultural centres of Ukraine ...

, Kuryluk deposited his "Signals" archive at the Ossolineum Library (now Stefanyk Library) where it has survived until now. Kuryluk was offered a job at '' Czerwony Sztandar'' (''Red Flag''), a Soviet-sponsored newspaper, but soon lost it because of the poem "Today Stalin called me" by Tadeusz Hollender

Tadeusz Hollender (30 May 1910 – 31 May 1943) was a Polish poet, translator and humorist. During World War II, he wrote satirical articles and poems in underground press, for that he was arrested by the German Gestapo and executed in May in the ...

published in ''Signals''.

In 1965, he became the director of the PWN Science Publisher, publishing the Big PWN Encyclopedia. When the volume with the entry on Nazi Camps was released, a storm broke out. The entry contained the factual information about the Nazi Camps being divided into concentration camp

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

s and extermination camp

Nazi Germany used six extermination camps (german: Vernichtungslager), also called death camps (), or killing centers (), in Central Europe during World War II to systematically murder over 2.7 million peoplemostly Jewsin the Holocaust. The v ...

(for Jews). This division, however, was used as a pretext to attack the Encyclopedia editors. The Party's nationalist faction insinuated that they were all Jews, accused them of "historical treachery that would rob the Polish people of their justified war suffering," and organized street demonstrations to protest "the Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

plot."

Political career

From July 1941 to July 1944, during the Nazi occupation of Lwów, Kuryluk was part of the resistance on both sides of the political divide. As member of PPR (Polish Workers Party

The Polish Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Partia Robotnicza, PPR) was a communist party in Poland from 1942 to 1948. It was founded as a reconstitution of the Communist Party of Poland (KPP) and merged with the Polish Socialist Party (PPS) in 1948 ...

), he was responsible for its clandestine radio station

Radio broadcasting is transmission of audio (sound), sometimes with related metadata, by radio waves to radio receivers belonging to a public audience. In terrestrial radio broadcasting the radio waves are broadcast by a land-based radio ...

and publishing activities. But he was also involved in the news service and publications of the AK (Home Army of the London government in exile).

In August 1944 Kuryluk moved from Lwów to Lublin and began to publish "Odrodzenie" ("The Renaissance"). The magazine was intended as a revival of "Signals" and the first issue commemorated writers and artists killed by the Nazis, publishing a long list of victims, including Bruno Schulz whom the underground tried to save. In 1945 he moved with his magazine to Cracow, and in 1947 to Warsaw. Among the contributors to "Odrodzenie" counted the future Nobel Prize laureates Czesław Miłosz

Czesław Miłosz (, also , ; 30 June 1911 – 14 August 2004) was a Polish-American poet, prose writer, translator, and diplomat. Regarded as one of the great poets of the 20th century, he won the 1980 Nobel Prize in Literature. In its citation ...

and Wisława Szymborska

Maria Wisława Anna SzymborskaVioletta Szostagazeta.pl, 9 February 2012. ostęp 2012-02-11 (; 2 July 1923 – 1 February 2012) was a Polish poet, essayist, translator, and recipient of the 1996 Nobel Prize in Literature. Born in Prowent (n ...

, the novelist Tadeusz Konwicki

Tadeusz Konwicki (22 June 1926 – 7 January 2015) was a Polish writer and film director, as well as a member of the Polish Language Council.

Life

Konwicki was born in 1926 as the only son of Jadwiga Kieżun and Michał Konwicki in Nowa Wilejka, ...

and the poet Tadeusz Różewicz

Tadeusz Różewicz (9 October 1921 – 24 April 2014) was a Polish poet, playwright, writer, and translator. Różewicz was in the first generation of Polish writers born after Poland regained its independence in 1918, following the century of f ...

.

After the Kielce pogrom

The Kielce pogrom was an outbreak of violence toward the Jewish community centre's gathering of refugees in the city of Kielce, Poland on 4 July 1946 by Polish soldiers, police officers, and civiliansanti-Semitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

's rise in postwar Poland was addressed by "Odrodzenie". However, with the Soviets firm grip on power and Stalinism

Stalinism is the means of governing and Marxist-Leninist policies implemented in the Soviet Union from 1927 to 1953 by Joseph Stalin. It included the creation of a one-party totalitarian police state, rapid industrialization, the theory ...

on the move, Kuryluk was quickly losing what had remained of his relative independence. In February 1948 he resigned from "Odrodzenie" and worked first in the literary section of the Polish Radio and later in publishing.

Minister of Culture

From April 1956 to April 1958, Kuryluk was Minister of Culture in the government ofJózef Cyrankiewicz

Józef Adam Zygmunt Cyrankiewicz (; 23 April 1911 – 20 January 1989) was a Polish Socialist (PPS) and after 1948 Communist politician. He served as premier of the Polish People's Republic between 1947 and 1952, and again for 16 years between ...

and used his term to liberalize culture, and to open it to the West. The French Institute opened in Warsaw (the first lecturer was Michel Foucault

Paul-Michel Foucault (, ; ; 15 October 192625 June 1984) was a French philosopher, historian of ideas, writer, political activist, and literary critic. Foucault's theories primarily address the relationship between power and knowledge, and how ...

), theater and movie stars (Laurence Olivier

Laurence Kerr Olivier, Baron Olivier (; 22 May 1907 – 11 July 1989) was an English actor and director who, along with his contemporaries Ralph Richardson and John Gielgud, was one of a trio of male actors who dominated the Theatre of the U ...

, Vivien Leigh

Vivien Leigh ( ; 5 November 1913 – 8 July 1967; born Vivian Mary Hartley), styled as Lady Olivier after 1947, was a British actress. She won the Academy Award for Best Actress twice, for her definitive performances as Scarlett O'Hara in ''Gon ...

, Gérard Philipe

Gérard Philipe (born Gérard Albert Philip, 4 December 1922 – 25 November 1959) was a prominent French actor who appeared in 32 films between 1944 and 1959. Active in both theatre and cinema, he was, until his early death, one of the main ...

, Yves Montand

Ivo Livi (), better known as Yves Montand (; 13 October 1921 – 9 November 1991), was an Italian-French actor and singer.

Early life

Montand was born Ivo Livi in Monsummano Terme, Italy, to Giovanni Livi, a broom manufacturer, Ivo held strong ...

) came to visit and to perform; western books and films, avant-garde music and art became available, the first exhibit by Henry Moore

Henry Spencer Moore (30 July 1898 – 31 August 1986) was an English artist. He is best known for his semi- abstract monumental bronze sculptures which are located around the world as public works of art. As well as sculpture, Moore produced ...

was arranged. New galleries and publications sprung up all over the country and a group of young Wrocław journalists founded, but soon had to stop publishing, "Signals II".

In the spring of 1957 Kuryluk was part of a government delegation headed by the Prime Minister Cyrankiewicz. The delegation was to tour Asia in order to lobby for the enlarged version of the Rapacki Plan

The Rapacki Plan (pronounced Rapatz-ki) was a proposal presented in a speech by Polish Foreign Minister Adam Rapacki to the United Nations General Assembly on 2 October 1957 as a limited plan for nuclear disarmament and demilitarization in Centra ...

that would suit the Soviets by creating a huge block of non-aligned countries, extending from East Berlin through Poland, Mongolia, India, China, Vietnam, Burma, and Cambodia. The delegation was received by Nehru, Mao Tse-Tung, Hồ Chí Minh and Prince Sihanouk, signed everywhere with meaningless declarations of friendship, and was a complete flop.

Towards the end of 1957 the Party (PZPR

The Polish United Workers' Party ( pl, Polska Zjednoczona Partia Robotnicza; ), commonly abbreviated to PZPR, was the communist party which ruled the Polish People's Republic as a one-party state from 1948 to 1989. The PZPR had led two other lega ...

) began to stop the process of liberalization. The First Secretary Gomułka was against the generous scholarship program of the Ministry of Culture, sending thousands of Polish intellectuals and artists to the West. When the writer Marek Hłasko

Marek Hłasko (14 January 1934 – 14 June 1969) was a Polish author and screenwriter.

Life

Hłasko's biography is highly mythologized, and many of the legends about his life he spread himself. Marek was born in Warsaw, as the only son of ...

chose freedom in Paris, this was taken as a pretext to fire Kuryluk as minister of culture, and to get him out of the country as well.

In December 1958, Kuryluk was appointed ambassador of the People's Republic of Poland to Austria

Austria, , bar, Östareich officially the Republic of Austria, is a country in the southern part of Central Europe, lying in the Eastern Alps. It is a federation of nine states, one of which is the capital, Vienna, the most populous ...

. He arrived with his family on 1 January 1959 in Vienna and served until the summer of 1964.

Honors and awards

Apacifist

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

by nature, he stayed away from military action and was particularly active in saving Jews. He hid Peppa Frauenglas and her two sons in his own sublet room. In 2002 he was honored by Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

as Righteous Among the Nations

Righteous Among the Nations ( he, חֲסִידֵי אֻמּוֹת הָעוֹלָם, ; "righteous (plural) of the world's nations") is an honorific used by the State of Israel to describe non-Jews who risked their lives during the Holocaust to sav ...

of the World.Karol Kuryluk

– his activity to save Jews' lives during the

Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

, at Yad Vashem

Yad Vashem ( he, יָד וַשֵׁם; literally, "a memorial and a name") is Israel's official memorial to the victims of the Holocaust. It is dedicated to preserving the memory of the Jews who were murdered; honoring Jews who fought against th ...

website

References

Picture gallery

Nikita Khrushchev

Nikita Sergeyevich Khrushchev (– 11 September 1971) was the First Secretary of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union from 1953 to 1964 and chairman of the country's Council of Ministers from 1958 to 1964. During his rule, Khrushchev s ...

during his meeting with John F. Kennedy in Vienna, 1961.

External links

* Encyklopedia Gazety Wyborczej, 2005 * Ewa Pankiewicz, ''Karol Kuryluk. Biografia polityczna 1910–1967,'' doctoral dissertation, Warsaw University. * ''Prasa Polska w latach 1939–1945,'' Warsaw, 1980. * ''Książka dla Karola'' (a collections of memoirs and essays on Karol Kuryluk, and his letters), ed. K. Koźniewski, Warsaw, 1984. * Tadeusz Breza, "Wspomnienie o Karolu", in ''Nelly,'' Warsaw, 1970 * Halina Górska, ''Chłopcy z ulic miasta,'' with an introduction by Karol Kuryluk, Warsaw, 1956. * ''Letters and Drawings of Bruno Schulz,'' edited by J. Ficowski, New York, 1988. * Czesław Miłosz, ''Zaraz po wojnie, korespondencja z pisarzami 1945–1950,'' Cracow, 1998 * Ewa Kuryluk, ''Ludzie z powietrza—Air People,'' Cracow, 2002 * Ewa Kuryluk, ''Cockroaches and Crocodiles,'' The Moment Magazine, July/August 2008 * ''Frascati,'' Cracow, 2009 * Ewa Kuryluk, ''Kangór z kamerą—Kangaroo with the Camera,'' Cracow and Warsaw, 2009 * Source materials about Karol Kuryluk in Polish, published in Zeszytyhistoryczne, in Acrobat PDF format: https://web.archive.org/web/20120306052421/http://www.marekhlasko.republika.pl/03_artykuly/Kuryluk.pdf * Ewa Kuryluk,Goldi,'' Warsaw, 2004

www.culture.pl/en/culture/artykuly/os_kuryluk_ewa

www.marekhlasko.republika.pl/03_artykuly/Kuryluk.pdf

Museum of the History of Polish Jews’ web page about Karol Kuryluk

{{DEFAULTSORT:Kuryluk, Karol 1910 births 1967 deaths Ambassadors of Poland to Austria Polish politicians Polish Righteous Among the Nations Polish male writers People from Zbarazh People from the Kingdom of Galicia and Lodomeria 20th-century Polish journalists