Merkabah mystical concepts and methods. According to this descriptive categorization, both versions of Kabbalistic theory, the medieval-Zoharic and the early-modern

Lurianic Kabbalah

Lurianic Kabbalah is a school of kabbalah named after Isaac Luria (1534–1572), the Jewish rabbi who developed it. Lurianic Kabbalah gave a seminal new account of Kabbalistic thought that its followers synthesised with, and read into, the earlie ...

together comprise the ''Theosophical'' tradition in Kabbalah, while the ''

Meditative-

Ecstatic Kabbalah

Abraham ben Samuel Abulafia ( he, אברהם בן שמואל אבולעפיה) was the founder of the school of "Prophetic Kabbalah". He was born in Zaragoza, Spain in 1240 and is assumed to have died sometime after 1291, following a stay on the ...

'' incorporates a parallel inter-related Medieval tradition. A third tradition, related but more shunned, involves the magical aims of ''

Practical Kabbalah''.

Moshe Idel

Moshe Idel ( he, משה אידל; born January 19, 1947) is a Romanian-Israeli historian and philosopher of Jewish mysticism. He is Emeritus Max Cooper Professor in Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, and a Senior Researcher at the ...

, for example, writes that these 3 basic models can be discerned operating and competing throughout the whole history of Jewish mysticism, beyond the particular Kabbalistic background of the Middle Ages. They can be readily distinguished by their basic intent with respect to God:

* The ''Theosophical'' or ''Theosophical-

Theurgic

Theurgy (; ) describes the practice of rituals, sometimes seen as magical in nature, performed with the intention of invoking the action or evoking the presence of one or more deities, especially with the goal of achieving henosis (uniting wi ...

'' tradition of ''Theoretical Kabbalah'' (the main focus of the Zohar and Luria) seeks to understand and describe the divine realm using the imaginative and mythic symbols of human psychological experience. As an intuitive conceptual alternative to rationalist

Jewish philosophy

Jewish philosophy () includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern ''Haskalah'' (Jewish Enlightenment) and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcile ...

, particularly

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

' Aristotelianism, this speculation became the central stream of Kabbalah, and the usual reference of the term "kabbalah". Its

theosophy

Theosophy is a religion established in the United States during the late 19th century. It was founded primarily by the Russian Helena Blavatsky and draws its teachings predominantly from Blavatsky's writings. Categorized by scholars of religion a ...

also implies the innate, centrally important theurgic influence of human conduct on redeeming or damaging the spiritual realms, as man is a divine microcosm, and the spiritual realms the divine macrocosm. The purpose of traditional theosophical kabbalah was to give the whole of normative

Jewish religious practice this mystical metaphysical meaning

* The ''

Meditative'' tradition of ''

Ecstatic Kabbalah

Abraham ben Samuel Abulafia ( he, אברהם בן שמואל אבולעפיה) was the founder of the school of "Prophetic Kabbalah". He was born in Zaragoza, Spain in 1240 and is assumed to have died sometime after 1291, following a stay on the ...

'' (exemplified by

Abraham Abulafia and

Isaac of Acre

Isaac ben Samuel of Acre ( fl. 13th–14th century) (Hebrew: יצחק בן שמואל דמן עכו, ''Yitzhak ben Shmuel d'min Akko'') was a Jewish kabbalist who fled to Spain.

According to Chaim Joseph David Azulai, Isaac ben Samuel was a p ...

) strives to achieve a mystical union with God, or nullification of the meditator in God's

Active intellect The active intellect (Latin: ''intellectus agens''; also translated as agent intellect, active intelligence, active reason, or productive intellect) is a concept in classical and medieval philosophy. The term refers to the formal (''morphe'') aspec ...

. Abraham Abulafia's "Prophetic Kabbalah" was the supreme example of this, though marginal in Kabbalistic development, and his alternative to the program of theosophical Kabbalah. Abulafian meditation built upon the philosophy of Maimonides, whose following remained the

rationalist threat to theosophical kabbalists

* The Magico-Talismanic tradition of ''

Practical Kabbalah'' (in often unpublished manuscripts) endeavours to alter both the Divine realms and the World using

practical methods. While theosophical interpretations of worship see its redemptive role as harmonising heavenly forces, Practical Kabbalah properly involved

white-magical acts, and was censored by kabbalists for only those completely pure of intent, as it relates to lower realms where purity and impurity are mixed. Consequently, it formed a separate minor tradition shunned from Kabbalah. Practical Kabbalah was prohibited by the Arizal until the

Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (; , ), refers to the two now-destroyed religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusa ...

is rebuilt and the required state of ritual purity is attainable.

[

]

According to Kabbalistic belief, early kabbalistic knowledge was transmitted orally by the Patriarchs,

prophets, and sages, eventually to be "interwoven" into Jewish religious writings and culture. According to this view, early kabbalah was, in around the 10th century BCE, an open knowledge practiced by over a million people in ancient Israel. Foreign conquests drove the Jewish spiritual leadership of the time (the

Sanhedrin

The Sanhedrin (Hebrew and Aramaic: סַנְהֶדְרִין; Greek: , ''synedrion'', 'sitting together,' hence 'assembly' or 'council') was an assembly of either 23 or 71 elders (known as "rabbis" after the destruction of the Second Temple), ap ...

) to hide the knowledge and make it secret, fearing that it might be misused if it fell into the wrong hands.

It is hard to clarify with any degree of certainty the exact concepts within kabbalah. There are several different schools of thought with very different outlooks; however, all are accepted as correct. Modern

halakhic

''Halakha'' (; he, הֲלָכָה, ), also transliterated as ''halacha'', ''halakhah'', and ''halocho'' ( ), is the collective body of Jewish religious laws which is derived from the written and Oral Torah. Halakha is based on biblical commandm ...

authorities have tried to narrow the scope and diversity within kabbalah, by restricting study to certain texts, notably Zohar and the teachings of Isaac Luria as passed down through

Hayyim ben Joseph Vital

Hayyim ben Joseph Vital ( he, רָבִּי חַיִּים בֶּן יוֹסֵף וִיטָאל; Safed, October 23, 1542 (Julian calendar) and October 11, 1542 (Gregorian Calendar) – Damascus, 23 April 1620) was a rabbi in Safed and the foremo ...

. However, even this qualification does little to limit the scope of understanding and expression, as included in those works are commentaries on Abulafian writings, ''Sefer Yetzirah'', Albotonian writings, and the ''Berit Menuhah'', which is known to the kabbalistic elect and which, as described more recently by

Gershom Scholem, combined ecstatic with theosophical mysticism. It is therefore important to bear in mind when discussing things such as the ''

sephirot'' and their interactions that one is dealing with highly abstract concepts that at best can only be understood intuitively.

Jewish and non-Jewish Kabbalah

From the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

onwards Jewish Kabbalah texts entered non-Jewish culture, where they were studied and translated by

Christian Hebraists

A Christian Hebraist is a scholar of Hebrew who comes from a Christian family background/belief, or is a Jewish adherent of Christianity. The main area of study is that commonly known as the Old Testament to Christians (and Tanakh to Jews), but C ...

and

Hermetic occultists. The syncretic traditions of

Christian Cabala and

Hermetic Qabalah developed independently of Judaic Kabbalah, reading the Jewish texts as universalist ancient wisdom preserved from the

Gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

traditions of antiquity. Both adapted the Jewish concepts freely from their Jewish understanding, to merge with multiple other theologies, religious traditions and magical associations. With the decline of Christian Cabala in the

Age of Reason

The Age of reason, or the Enlightenment, was an intellectual and philosophical movement that dominated the world of ideas in Europe during the 17th to 19th centuries.

Age of reason or Age of Reason may also refer to:

* Age of reason (canon law), ...

, Hermetic Qabalah continued as a central underground tradition in

Western esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

. Through these non-Jewish associations with magic,

alchemy

Alchemy (from Arabic: ''al-kīmiyā''; from Ancient Greek: χυμεία, ''khumeía'') is an ancient branch of natural philosophy, a philosophical and protoscientific tradition that was historically practiced in China, India, the Muslim world, ...

and divination, Kabbalah acquired some popular

occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

connotations forbidden within Judaism, where Jewish theurgic Practical Kabbalah was a minor, permitted tradition restricted for a few elite. Today, many publications on Kabbalah belong to the non-Jewish

New Age

New Age is a range of spiritual or religious practices and beliefs which rapidly grew in Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise definition difficult. Although many scholars conside ...

and occult traditions of Cabala, rather than giving an accurate picture of Judaic Kabbalah. Instead, academic and traditional Jewish publications now translate and study Judaic Kabbalah for wide readership.

History of Jewish mysticism

Origins

According to the traditional Kabbalistic understanding, Kabbalah dates from Eden.

Sefer Raziel HaMalakh

''Sefer Raziel HaMalakh'', (Hebrew:, "the book of Raziel the angel''"''), is a grimoire of Practical Kabbalah from the Middle Ages written primarily in Hebrew and Aramaic. ''Liber Razielis Archangeli'', its 13th-century Latin translation produce ...

It came down from a remote past as a revelation to elect

tzadikim

Tzadik ( he, צַדִּיק , "righteous ne, also ''zadik'', ''ṣaddîq'' or ''sadiq''; pl. ''tzadikim'' ''ṣadiqim'') is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The ...

(righteous people), and, for the most part, was preserved only by a privileged few. Talmudic Judaism records its view of the proper protocol for teaching secrets in the ''

Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law (''halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cente ...

'', Tractate ''

Hagigah

Hagigah or Chagigah (Hebrew: חגיגה, lit. "Festival Offering") is one of the tractates comprising Moed, one of the six orders of the Mishnah, a collection of Jewish traditions included in the Talmud. It deals with the Three Pilgrimage Festiv ...

'', 11b-13a, "One should not teach . . . the

work of Creation in pairs, nor the

work of the Chariot to an individual, unless he is wise and can understand the implications himself etc."

Contemporary scholarship suggests that various schools of Jewish esotericism arose at different periods of Jewish history, each reflecting not only prior forms of

mysticism

Mysticism is popularly known as becoming one with God or the Absolute, but may refer to any kind of ecstasy or altered state of consciousness which is given a religious or spiritual meaning. It may also refer to the attainment of insight in u ...

, but also the intellectual and cultural milieu of that historical period. Answers to questions of transmission, lineage, influence, and innovation vary greatly and cannot be easily summarised.

Terms

Originally, Kabbalistic knowledge was believed to be an integral part of the

Oral Torah

According to Rabbinic Judaism, the Oral Torah or Oral Law ( he, , Tōrā šebbəʿal-pe}) are those purported laws, statutes, and legal interpretations that were not recorded in the Five Books of Moses, the Written Torah ( he, , Tōrā šebbīḵ� ...

, given by God to

Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

on

Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai ( he , הר סיני ''Har Sinai''; Aramaic: ܛܘܪܐ ܕܣܝܢܝ ''Ṭūrāʾ Dsyny''), traditionally known as Jabal Musa ( ar, جَبَل مُوسَىٰ, translation: Mount Moses), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is ...

around the 13th century BCE according to its followers; although some believe that Kabbalah began with

Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

.

For a few centuries the esoteric knowledge was referred to by its aspect practice—meditation

Hitbonenut

Jewish meditation includes practices of settling the mind, introspection, visualization, emotional insight, contemplation of divine names, or concentration on philosophical, ethical or mystical ideas. Meditation may accompany unstructured, perso ...

( he, הִתְבּוֹנְנוּת), Rebbe

Nachman of Breslov's

Hitbodedut ( he, הִתְבּוֹדְדוּת), translated as "being alone" or "isolating oneself", or by a different term describing the actual, desired goal of the practice—prophecy ("''NeVu'a''" he, נְבוּאָה). Kabbalistic scholar

Aryeh Kaplan traces the origins of medieval

Kabbalistic meditative methods to their inheritance from orally transmitted remnants of the

Biblical Prophetic tradition, and reconstructs their terminology and speculated techniques.

From the 5th century BCE, when the works of the Tanakh were edited and canonised and the secret knowledge encrypted within the various writings and scrolls ("Megilot"), esoteric knowledge became referred to as ''

Ma'aseh Merkavah'' ( he, מַעֲשֶׂה מֶרְכָּבָה) and ''

Ma'aseh B'reshit'' ( he, מַעֲשֶׂה בְּרֵאשִׁית), respectively "the act of the Chariot" and "the act of Creation".

Merkabah mysticism alluded to the encrypted knowledge, and

meditation methods within the book of the prophet

Ezekiel

Ezekiel (; he, יְחֶזְקֵאל ''Yəḥezqēʾl'' ; in the Septuagint written in grc-koi, Ἰεζεκιήλ ) is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible.

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Ezekiel is acknow ...

describing his vision of the "Divine Chariot". B'reshit mysticism referred to the first chapter of

Genesis

Genesis may refer to:

Bible

* Book of Genesis, the first book of the biblical scriptures of both Judaism and Christianity, describing the creation of the Earth and of mankind

* Genesis creation narrative, the first several chapters of the Book of ...

( he, בְּרֵאשִׁית) in the Torah that is believed to contain secrets of the creation of the universe and forces of nature. These terms received their later historical documentation and description in the second chapter of the Talmudic tractate ''Hagigah'' from the early centuries CE.

Confidence in new

Prophetic revelation closed after the Biblical return from Babylon in

Second Temple Judaism

Second Temple Judaism refers to the Jewish religion as it developed during the Second Temple period, which began with the construction of the Second Temple around 516 BCE and ended with the Roman siege of Jerusalem in 70 CE.

The Second Temple pe ...

, shifting to canonisation and exegesis of Scripture after

Ezra the Scribe

Ezra (; he, עֶזְרָא, '; fl. 480–440 BCE), also called Ezra the Scribe (, ') and Ezra the Priest in the Book of Ezra, was a Jewish scribe (''sofer'') and priest (''kohen''). In Greco-Latin Ezra is called Esdras ( grc-gre, Ἔσδρας ...

. Lesser level prophecy of

Ruach Hakodesh

In Judaism, the Holy Spirit ( he, רוח הקודש, ''ruach ha-kodesh'') refers to the divine force, quality, and influence of God over the universe or over God's creatures, in given contexts.Maimonides, Moses. Part II, Ch. 45: "The various cla ...

remained, with angelic revelations, esoteric heavenly secrets, and

eschatological deliverance from Greek and Roman oppression of

Apocalyptic literature

Apocalyptic literature is a genre of prophetical writing that developed in post- Exilic Jewish culture and was popular among millennialist early Christians. '' Apocalypse'' ( grc, , }) is a Greek word meaning "revelation", "an unveiling or unf ...

among early Jewish proto-mystical circles, such as the

Book of Daniel

The Book of Daniel is a 2nd-century BC biblical apocalypse with a 6th century BC setting. Ostensibly "an account of the activities and visions of Daniel, a noble Jew exiled at Babylon", it combines a prophecy of history with an eschatology (a ...

and the

Dead Sea Scrolls

The Dead Sea Scrolls (also the Qumran Caves Scrolls) are ancient Jewish and Hebrew religious manuscripts discovered between 1946 and 1956 at the Qumran Caves in what was then Mandatory Palestine, near Ein Feshkha in the West Bank, on the nor ...

community of

Qumran. Early

Jewish mystical

Academic study of Jewish mysticism, especially since Gershom Scholem's ''Major Trends in Jewish Mysticism'' (1941), distinguishes between different forms of mysticism across different eras of Jewish history. Of these, Kabbalah, which emerged in 1 ...

literature inherited the developing concerns and remnants of Prophetic and Apocalyptic Judaisms.

Mystic elements of the Torah

When read by later generations of Kabbalists, the Torah's description of the creation in the Book of Genesis reveals mysteries about God himself, the true nature of Adam and Eve, the

Garden of Eden

In Abrahamic religions, the Garden of Eden ( he, גַּן־עֵדֶן, ) or Garden of God (, and גַן־אֱלֹהִים ''gan-Elohim''), also called the Terrestrial Paradise, is the Bible, biblical paradise described in Book of Genesis, Genes ...

( he, גַּן עֵדֶן), the

Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil

In Judaism and Christianity, the tree of the knowledge of good and evil ( he, עֵץ הַדַּעַת טוֹב וָרָע, ʿêṣ had-daʿaṯ ṭōḇ wā-rāʿ, label=Tiberian Hebrew, ) is one of two specific trees in the story of the Garden ...

( he, עֵץ הַדַּעַת שֶׁל טוֹב וְרַע), and the

Tree of Life

The tree of life is a fundamental archetype in many of the world's mythological, religious, and philosophical traditions. It is closely related to the concept of the sacred tree.Giovino, Mariana (2007). ''The Assyrian Sacred Tree: A History ...

( he, עֵץ חַיִּים), as well as the interaction of these supernatural entities with the

Serpent

Serpent or The Serpent may refer to:

* Snake, a carnivorous reptile of the suborder Serpentes

Mythology and religion

* Sea serpent, a monstrous ocean creature

* Serpent (symbolism), the snake in religious rites and mythological contexts

* Serp ...

( he, נָחָשׁ), which leads to disaster when they eat the

forbidden fruit ( he, פְּרִי עֵץ הַדַּעַת), as recorded in

Genesis 3

Genesis, stylized as GENESIS, is a series of annual ''Super Smash Bros.'' tournaments occurring in the San Francisco Bay Area of the US state of California. The first Genesis tournament took place in 2009 in Antioch at the Contra Costa County Fa ...

.

[Artson, Bradley Shavit](_blank)

''From the Periphery to the Centre: Kabbalah and the Conservative Movement'', United Synagogue Review, Spring 2005, Vol. 57 No. 2

The Bible provides ample additional material for mythic and mystical speculation. The prophet

Ezekiel

Ezekiel (; he, יְחֶזְקֵאל ''Yəḥezqēʾl'' ; in the Septuagint written in grc-koi, Ἰεζεκιήλ ) is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible.

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Ezekiel is acknow ...

's visions in particular attracted

much mystical speculation, as did

Isaiah

Isaiah ( or ; he, , ''Yəšaʿyāhū'', "God is Salvation"), also known as Isaias, was the 8th-century BC Israelite prophet after whom the Book of Isaiah is named.

Within the text of the Book of Isaiah, Isaiah himself is referred to as "the ...

's Temple vision. Other mystical events include

Jacob

Jacob (; ; ar, يَعْقُوب, Yaʿqūb; gr, Ἰακώβ, Iakṓb), later given the name Israel, is regarded as a patriarch of the Israelites and is an important figure in Abrahamic religions, such as Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. J ...

's vision of the

ladder to heaven, and

Moses

Moses hbo, מֹשֶׁה, Mōše; also known as Moshe or Moshe Rabbeinu (Mishnaic Hebrew: מֹשֶׁה רַבֵּינוּ, ); syr, ܡܘܫܐ, Mūše; ar, موسى, Mūsā; grc, Mωϋσῆς, Mōÿsēs () is considered the most important pro ...

' encounters with the

Burning bush and God on

Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai ( he , הר סיני ''Har Sinai''; Aramaic: ܛܘܪܐ ܕܣܝܢܝ ''Ṭūrāʾ Dsyny''), traditionally known as Jabal Musa ( ar, جَبَل مُوسَىٰ, translation: Mount Moses), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is ...

.

The

72 letter name of God which is used in Jewish mysticism for meditation purposes is derived from the Hebrew verbal utterance Moses spoke in the presence of an angel, while the

Sea of Reeds parted, allowing the Hebrews to escape their approaching attackers. The miracle of the Exodus, which led to Moses receiving the

Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ� ...

and the Jewish Orthodox view of the acceptance of the Torah at Mount Sinai, preceded the creation of the first Jewish nation approximately three hundred years before

King Saul.

Talmudic era

In early

Rabbinic Judaism

Rabbinic Judaism ( he, יהדות רבנית, Yahadut Rabanit), also called Rabbinism, Rabbinicism, or Judaism espoused by the Rabbanites, has been the mainstream form of Judaism since the 6th century CE, after the codification of the Babylonian ...

(the early centuries of the 1st millennium CE), the terms ''

Ma'aseh Bereshit'' ("Works of Creation") and ''

Ma'aseh Merkabah'' ("Works of the Divine Throne/Chariot") clearly indicate the

Midrash

''Midrash'' (;["midrash"]

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

ic nature of these speculations; they are really based upon Genesis 1 and

Ezekiel

Ezekiel (; he, יְחֶזְקֵאל ''Yəḥezqēʾl'' ; in the Septuagint written in grc-koi, Ἰεζεκιήλ ) is the central protagonist of the Book of Ezekiel in the Hebrew Bible.

In Judaism, Christianity, and Islam, Ezekiel is acknow ...

1:4–28, while the names ''Sitrei Torah'' (Hidden aspects of the Torah) (Talmud ''Hag.'' 13a) and ''Razei Torah'' (Torah secrets) (''Ab.'' vi. 1) indicate their character as secret lore.

Talmudic doctrine forbade the public teaching of esoteric doctrines and warned of their dangers. In the

Mishnah

The Mishnah or the Mishna (; he, מִשְׁנָה, "study by repetition", from the verb ''shanah'' , or "to study and review", also "secondary") is the first major written collection of the Jewish oral traditions which is known as the Oral Torah ...

(Hagigah 2:1), rabbis were warned to teach the mystical creation doctrines only to one student at a time. To highlight the danger, in one Jewish

aggadic ("legendary") anecdote, four prominent rabbis of the Mishnaic period (1st century CE) are said to have

visited the Orchard (that is, Paradise, ''pardes'', Hebrew: lit., ''orchard''):

In notable readings of this legend, only Rabbi Akiba was fit to handle the study of mystical doctrines. The ''

Tosafot

The Tosafot, Tosafos or Tosfot ( he, תוספות) are medieval commentaries on the Talmud. They take the form of critical and explanatory glosses, printed, in almost all Talmud editions, on the outer margin and opposite Rashi's notes.

The auth ...

'', medieval commentaries on the Talmud, say that the four sages "did not go up literally, but it appeared to them as if they went up". On the other hand,

Louis Ginzberg

Louis Ginzberg ( he, לוי גינצבורג, ''Levy Gintzburg''; russian: Леви Гинцберг, ''Levy Ginzberg''; November 28, 1873 – November 11, 1953) was a Russian-born American rabbi and Talmudic scholar of Lithuanian-Jewish desce ...

, writes in the ''

Jewish Encyclopedia

''The Jewish Encyclopedia: A Descriptive Record of the History, Religion, Literature, and Customs of the Jewish People from the Earliest Times to the Present Day'' is an English-language encyclopedia containing over 15,000 articles on th ...

'' (1901–1906) that the journey to paradise "is to be taken literally and not allegorically".

In contrast to the Kabbalists, Maimonides interprets ''pardes'' as philosophy and not mysticism.

Pre-Kabbalistic schools

Early mystical literature

The mystical methods and doctrines of

Hekhalot

The Hekhalot literature (sometimes transliterated Heichalot) from the Hebrew word for "Palaces", relating to visions of ascents into heavenly palaces. The genre overlaps with ''Merkabah'' or "Chariot" literature, concerning Ezekiel's chariot, so t ...

(Heavenly "Chambers") and

Merkabah (Divine "Chariot") texts, named by modern scholars from these repeated motifs, lasted from the 1st century BCE through to the 10th century CE, before giving way to the documented manuscript emergence of Kabbalah. Initiates were said to "descend the chariot", possibly a reference to internal introspection on the Heavenly journey through the spiritual realms. The ultimate aim was to arrive before the transcendent awe, rather than nearness, of the Divine. The mystical protagonists of the texts are famous

Talmudic Sages of Rabbinic Judaism, either

pseudepigraphic

Pseudepigrapha (also anglicized as "pseudepigraph" or "pseudepigraphs") are falsely attributed works, texts whose claimed author is not the true author, or a work whose real author attributed it to a figure of the past.Bauckham, Richard; "Pseu ...

or documenting remnants of a developed tradition. From the 8th to 11th centuries, the Hekhalot texts, and the proto-Kabbalistic early

cosmogonic

Cosmogony is any model concerning the origin of the cosmos or the universe.

Overview

Scientific theories

In astronomy, cosmogony refers to the study of the origin of particular astrophysical objects or systems, and is most commonly used i ...

''

Sefer Yetzirah

''Sefer Yetzirah'' ( ''Sēp̄er Yəṣīrā'', ''Book of Formation'', or ''Book of Creation'') is the title of a book on Jewish mysticism, although some early commentators treated it as a treatise on mathematical and linguistic theory as opposed ...

'' ("Book of Creation") made their way into European Jewish circles. A controversial esoteric work from associated literature describing a cosmic Anthropos, ''

Shi'ur Qomah

Shi’ur Qomah ( he, שיעור קומה, lit. Dimensions of the Body) is a midrashic text that is part of the Hekhalot literature. It purports to record, in anthropomorphic terms, the secret names and precise measurements of God's corporeal limbs ...

'', was interpreted allegorically by subsequent Kabbalists in their meditation on the

Sephirot Divine Persona.

Hasidei Ashkenaz

Another, separate influential mystical, theosophical, and pious movement, shortly before the arrival there of Kabbalistic theory, was the "

Hasidei Ashkenaz" (חסידי אשכנז) or Medieval German Pietists from 1150 to 1250. This ethical-ascetic movement with elite theoretical and

Practical Kabbalah speculations arose mostly among a single scholarly family, the

Kalonymus family

Kalonymos or Kalonymus ( he, קָלוֹנִימוּס ''Qālōnīmūs'') is a prominent Jewish family who lived in Italy, mostly in Lucca and in Rome, which, after the settlement at Mainz and Speyer of several of its members, took during many gener ...

of the French and German Rhineland. Its

Jewish ethics

Jewish ethics is the ethics of the Jewish religion or the Jewish people. A type of normative ethics, Jewish ethics may involve issues in Jewish law as well as non-legal issues, and may involve the convergence of Judaism and the Western philosoph ...

of saintly self-sacrifice influenced

Ashkenazi

Ashkenazi Jews ( ; he, יְהוּדֵי אַשְׁכְּנַז, translit=Yehudei Ashkenaz, ; yi, אַשכּנזישע ייִדן, Ashkenazishe Yidn), also known as Ashkenazic Jews or ''Ashkenazim'',, Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation: , singu ...

Jewry,

Musar literature

Musar literature is didactic Jewish ethical literature which describes virtues and vices and the path towards character improvement. This literature gives the name to the Musar movement, in 19th century Lithuania, but this article considers such l ...

and later emphases of piety in Judaism.

Medieval emergence of the Kabbalah

Modern scholars have identified several mystical brotherhoods that functioned in Europe starting in the 12th century. Some, such as the "Iyyun Circle" and the "Unique Cherub Circle", were truly esoteric, remaining largely anonymous. The first documented historical emergence of Theosophical Kabbalistic doctrine occurred among Jewish

Sages of Provence and Languedoc in southern France in the latter 1100s, with the appearance or consolidation of the mysterious work the ''

Bahir'' (Book of "Brightness"), a

midrash

''Midrash'' (;["midrash"]

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''. he, מִדְרָשׁ; ...

describing God's

sephirot attributes as a dynamic interacting

hypostatic drama in the Divine realm, and the school of

Isaac the Blind

Isaac the Blind ( he, רַבִּי יִצְחַק סַגִּי נְהוֹר ''Rabbī Yīṣḥaq Saggī Nəhōr'', literally "Rabbi Isaac, blind person"; c. 1160–1235 in Provence, France), was a French rabbi and a famous writer on Kabbalah (Jewi ...

(1160–1235) among critics of the rationalist influence of

Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

. From there Kabbalah spread to

Catalonia

Catalonia (; ca, Catalunya ; Aranese Occitan: ''Catalonha'' ; es, Cataluña ) is an autonomous community of Spain, designated as a ''nationality'' by its Statute of Autonomy.

Most of the territory (except the Val d'Aran) lies on the north ...

in north-east Spain around the central Rabbinic figure of

Nahmanides (the ''Ramban'') (1194–1270) in the early 1200s, with a

Neoplatonic orientation focused on the upper sephirot. Subsequently, Kabbalistic doctrine reached its fullest classic expression among

Castilian Kabbalists from the latter 1200s, with the ''

Zohar

The ''Zohar'' ( he, , ''Zōhar'', lit. "Splendor" or "Radiance") is a foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah (the five ...

'' (Book of "Splendor") literature, concerned with cosmic healing of

gnostic

Gnosticism (from grc, γνωστικός, gnōstikós, , 'having knowledge') is a collection of religious ideas and systems which coalesced in the late 1st century AD among Jewish and early Christian sects. These various groups emphasized pe ...

dualities between the lower, revealed male and female attributes of God.

Rishonim ("Elder Sages") of exoteric Judaism who were deeply involved in Kabbalistic activity, gave the Kabbalah wide scholarly acceptance, including Nahmanides and

Bahya ben Asher

Bahya ben Asher ibn Halawa (, 1255–1340) was a rabbi and scholar of Judaism, best known as a commentator on the Hebrew Bible.

He is one of two scholars now referred to as Rabbeinu Behaye, the other being philosopher Bahya ibn Paquda.

Biogra ...

(''Rabbeinu Behaye'') (died 1340), whose classic

commentaries on the Torah reference Kabbalistic esotericism.

Many Orthodox Jews reject the idea that Kabbalah underwent significant historical development or change such as has been proposed above. After the composition known as the Zohar was presented to the public in the 13th century, the term "Kabbalah" began to refer more specifically to teachings derived from, or related to, the ''

Zohar

The ''Zohar'' ( he, , ''Zōhar'', lit. "Splendor" or "Radiance") is a foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah (the five ...

''. At an even later time, the term began to generally be applied to Zoharic teachings as elaborated upon by

Isaac Luria

Isaac ben Solomon Luria Ashkenazi (1534Fine 2003, p24/ref> – July 25, 1572) ( he, יִצְחָק בן שלמה לוּרְיָא אשכנזי ''Yitzhak Ben Sh'lomo Lurya Ashkenazi''), commonly known in Jewish religious circles as "Ha'ARI" (mean ...

(the Arizal). Historians generally date the start of Kabbalah as a major influence in Jewish thought and practice with the publication of the Zohar and climaxing with the spread of the Lurianic teachings. The majority of

Haredi Jews accept the Zohar as the representative of the ''Ma'aseh Merkavah'' and ''Ma'aseh B'reshit'' that are referred to in Talmudic texts.

Ecstatic Kabbalah

Contemporary with the Zoharic efflorescence of Spanish Theosophical-Theurgic Kabbalah, Spanish exilarch

Abraham Abulafia developed his own alternative, Maimonidean system of Ecstatic-Prophetic Kabbalah

meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally cal ...

, each consolidating aspects of a claimed inherited

mystical tradition from Biblical times. This was the classic time when various different interpretations of an esoteric meaning to Torah were articulated among Jewish thinkers. Abulafia interpreted Theosophical Kabbalah's

Sephirot Divine attributes, not as supernal

hypostases

Hypostasis, hypostatic, or hypostatization (hypostatisation; from the Ancient Greek , "under state") may refer to:

* Hypostasis (philosophy and religion), the essence or underlying reality

** Hypostasis (linguistics), personification of entities

...

which he opposed, but in psychological terms. Instead of influencing harmony in the divine real by

theurgy, his meditative scheme aimed for mystical union with God, drawing down prophetic influx on the individual. He saw this meditation using

Divine Names as a superior form of Kabbalistic ancient tradition. His version of Kabbalah, followed in the medieval eastern Mediterranean, remained a marginal stream to mainstream Theosophical Kabbalah development. Abulafian elements were later incorporated into the 16th century theosophical Kabbalistic systemisations of

Moses Cordovero and

Hayim Vital

Hayyim ben Joseph Vital ( he, רָבִּי חַיִּים בֶּן יוֹסֵף וִיטָאל; Safed, October 23, 1542 (Julian calendar) and October 11, 1542 (Gregorian Calendar) – Damascus, 23 April 1620) was a rabbi in Safed and the foremo ...

. Through them, later

Hasidic Judaism

Hasidism, sometimes spelled Chassidism, and also known as Hasidic Judaism (Ashkenazi Hebrew: חסידות ''Ḥăsīdus'', ; originally, "piety"), is a Judaism, Jewish religious group that arose as a spiritual revival movement in the territory ...

incorporated elements of

unio mystica and psychological focus from Abulafia.

Early modern era

Lurianic Kabbalah

Following the upheavals and dislocations in the Jewish world as a result of

anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

during the Middle Ages, and the national trauma of the

expulsion from Spain Expulsion from Spain may refer to:

*Expulsion of Jews from Spain (1492 in Aragon and Castile, 1497–98 in Navarre)

*Expulsion of the Moriscos (1609–1614)

See also

*Forced conversions of Muslims in Spain

The forced conversions of Muslims in ...

in 1492, closing the

Spanish Jewish flowering, Jews began to search for signs of when the long-awaited

Jewish Messiah

The Messiah in Judaism () is a savior and liberator figure in Jewish eschatology, who is believed to be the future redeemer of the Jewish people. The concept of messianism originated in Judaism, and in the Hebrew Bible a messiah is a king or Hig ...

would come to comfort them in their painful exiles. In the 16th century, the community of

Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardi Hebrew, Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), i ...

in the Galilee became the centre of Jewish mystical, exegetical, legal and liturgical developments. The Safed mystics responded to the Spanish expulsion by turning Kabbalistic doctrine and practice towards a messianic focus.

Moses Cordovero (The ''RAMAK'' 1522–1570) and his school popularized the teachings of the Zohar which had until then been only a restricted work. Cordovero's comprehensive works achieved the first (quasi-rationalistic) of Theosophical Kabbalah's two systemisations, harmonising preceding interpretations of the Zohar on its own apparent terms. The author of the ''

Shulkhan Arukh

The ''Shulchan Aruch'' ( he, שֻׁלְחָן עָרוּך , literally: "Set Table"), sometimes dubbed in English as the Code of Jewish Law, is the most widely consulted of the various legal codes in Judaism. It was authored in Safed (today in Is ...

'' (the normative Jewish "Code of Law"),

Yosef Karo (1488–1575), was also a scholar of Kabbalah who kept a personal mystical diary.

Moshe Alshich wrote a mystical commentary on the Torah, and

Shlomo Alkabetz wrote Kabbalistic commentaries and poems.

The messianism of the Safed mystics culminated in Kabbalah receiving its biggest transformation in the Jewish world with the explication of its new interpretation from Isaac Luria (The ''ARI'' 1534–1572), by his disciples

Hayim Vital

Hayyim ben Joseph Vital ( he, רָבִּי חַיִּים בֶּן יוֹסֵף וִיטָאל; Safed, October 23, 1542 (Julian calendar) and October 11, 1542 (Gregorian Calendar) – Damascus, 23 April 1620) was a rabbi in Safed and the foremo ...

and

Israel Sarug

Israel Sarug Ashkenazi (also "Saruk" or "Srugo") (16th century; 1590–1610) was a pupil of Isaac Luria, and devoted himself at the death of his master to the propagation of the latter's Kabbalistic system, for which he gained many adherents in v ...

. Both transcribed Luria's teachings (in variant forms) gaining them widespread popularity, Sarug taking Lurianic Kabbalah to Europe, Vital authoring the latterly canonical version. Luria's teachings came to rival the influence of the Zohar and Luria stands, alongside Moses de Leon, as the most influential mystic in Jewish history. Lurianic Kabbalah gave Theosophical Kabbalah its second, complete (supra-rational) of two systemisations, reading the Zohar in light of its most esoteric sections (the ''Idrot''), replacing the broken Sephirot attributes of God with rectified

Partzufim (Divine Personas), embracing reincarnation,

repair, and the urgency of cosmic

Jewish messianism dependent on each person's soul tasks.

Influence on non-Jewish society

From the European

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

on, Judaic Kabbalah became a significant influence in non-Jewish culture, fully divorced from the separately evolving Judaic tradition. Kabbalah received the interest of

Christian Hebraist scholars and

occult

The occult, in the broadest sense, is a category of esoteric supernatural beliefs and practices which generally fall outside the scope of religion and science, encompassing phenomena involving otherworldly agency, such as magic and mysticism a ...

ists, who freely syncretised and adapted it to diverse non-Jewish spiritual traditions and belief systems of

Western esotericism

Western esotericism, also known as esotericism, esoterism, and sometimes the Western mystery tradition, is a term scholars use to categorise a wide range of loosely related ideas and movements that developed within Western society. These ideas a ...

.

Christian Cabalists from the 15th-18th centuries adapted what they saw as ancient Biblical wisdom to Christian theology, while

Hermeticism lead to Kabbalah's incorporation into Western

magic

Magic or Magick most commonly refers to:

* Magic (supernatural), beliefs and actions employed to influence supernatural beings and forces

* Ceremonial magic, encompasses a wide variety of rituals of magic

* Magical thinking, the belief that unrela ...

through

Hermetic Qabalah. Presentations of Kabbalah in occult and

New Age

New Age is a range of spiritual or religious practices and beliefs which rapidly grew in Western society during the early 1970s. Its highly eclectic and unsystematic structure makes a precise definition difficult. Although many scholars conside ...

books on Kabbalah bear little resemblance to Judaic Kabbalah.

Ban on studying Kabbalah

The Rabbinic ban on studying Kabbalah in Jewish society was lifted by the efforts of the 16th-century kabbalist

Avraham Azulai

Abraham ben Mordecai Azulai (c. 1570–1643) ( he, אברהם בן מרדכי אזולאי) was a Kabbalistic author and commentator born in Fez, Morocco. In 1599 he moved to Ottoman Palestine and settled in Hebron.

Biography

In Hebron, Azulai wr ...

(1570–1643).

The question, however, is whether the ban ever existed in the first place. Concerning the above quote by Avraham Azulai, it has found many versions in English, another is this

The lines concerning the year 1490 are also missing from the Hebrew edition of ''Hesed L'Avraham'', the source work that both of these quote from. Furthermore, by Azulai's view the ban was lifted thirty years before his birth, a time that would have corresponded with Haim Vital's publication of the teaching of Isaac Luria. Moshe Isserles understood there to be only a minor restriction, in his words, "One's belly must be full of meat and wine, discerning between the prohibited and the permitted." He is supported by the Bier Hetiv, the Pithei Teshuva as well as the

Vilna Gaon

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( he , ר' אליהו בן שלמה זלמן ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman'') known as the Vilna Gaon (Yiddish: דער װילנער גאון ''Der Vilner Gaon'', pl, Gaon z Wilna, lt, Vilniaus Gaonas) or Elijah of ...

. The Vilna Gaon says, "There was never any ban or enactment restricting the study of the wisdom of Kabbalah. Any who says there is has never studied Kabbalah, has never seen PaRDeS, and speaks as an ignoramus."

Sefardi and Mizrahi

The Kabbalah of the

Sefardi

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

(Iberian Peninsula) and

Mizrahi

''Mizrachi'' or ''Mizrahi'' ( he, מזרחי) has two meanings.

In the literal Hebrew meaning ''Eastern'', it may refer to:

*Mizrahi Jews, Jews from the Middle East

* Mizrahi (surname), a Sephardic surname, given to Jews who got to the Iberian P ...

(Middle East, North Africa, and the Caucasus) Torah scholars has a long history. Kabbalah in various forms was widely studied, commented upon, and expanded by North African, Turkish, Yemenite, and Asian scholars from the 16th century onward. It flourished among Sefardic Jews in Tzfat (

Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardi Hebrew, Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), i ...

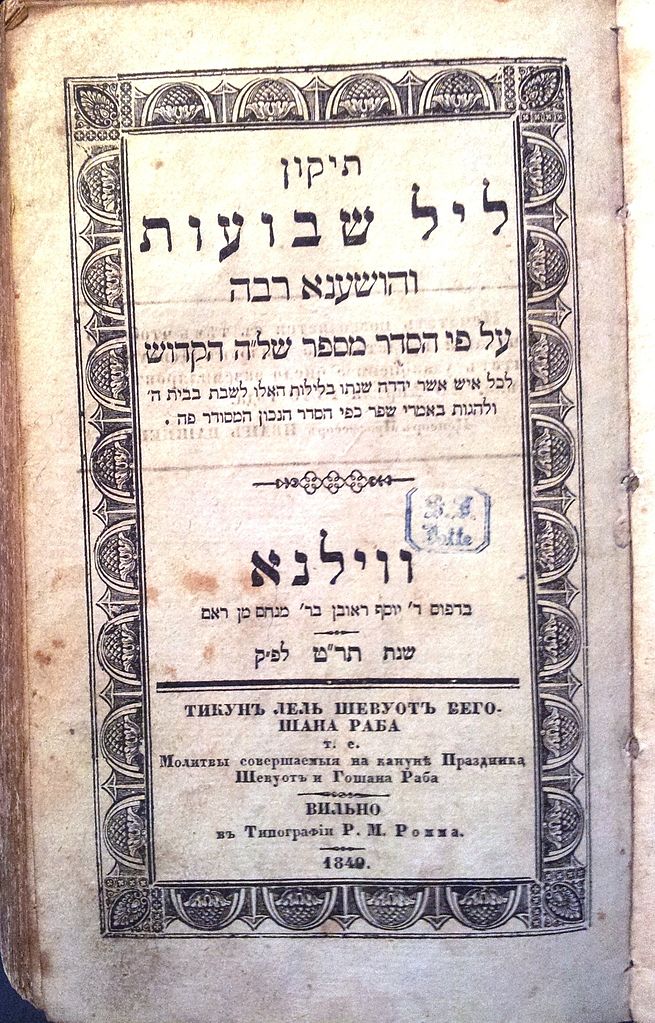

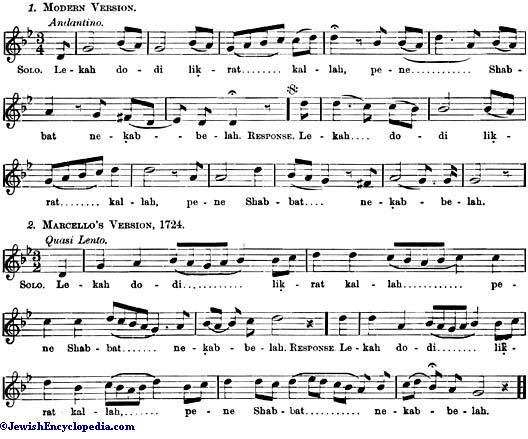

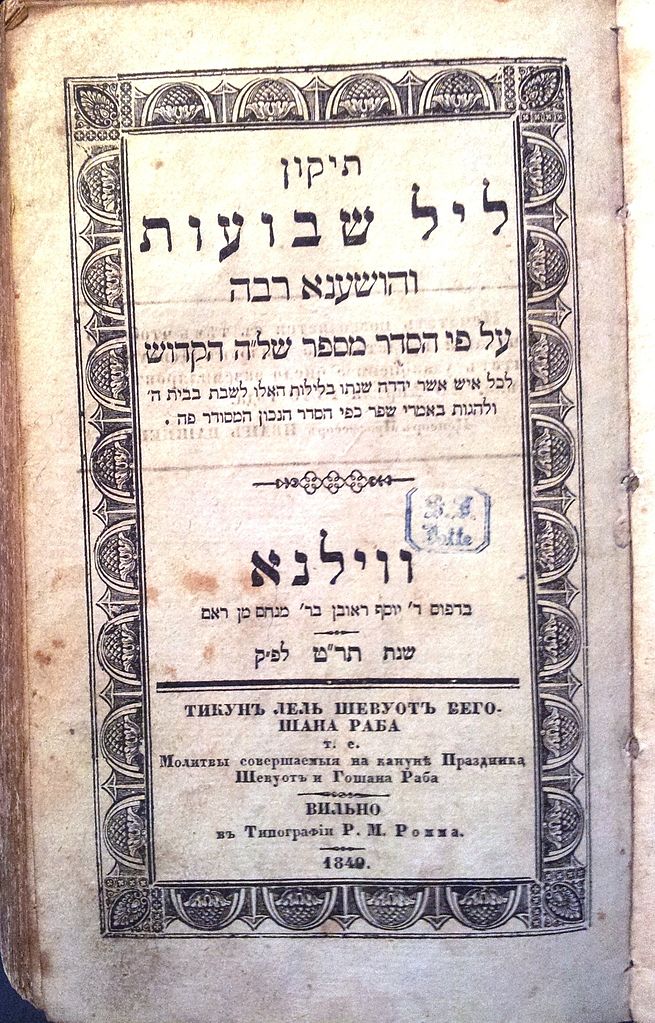

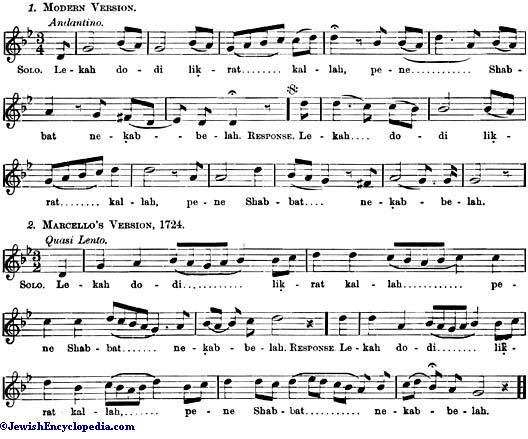

), even before the arrival of Isaac Luria. Yosef Karo, author of the ''Shulchan Arukh'' was part of the Tzfat school of Kabbalah. Shlomo Alkabetz, author of the hymn ''

Lekhah Dodi

Lekha Dodi ( he, לכה דודי) is a Hebrew-language Jewish liturgical song recited Friday at dusk, usually at sundown, in synagogue to welcome the Sabbath prior to the evening services. It is part of Kabbalat Shabbat.

The refrain of ''Lekha ...

'', taught there.

His disciple

Moses ben Jacob Cordovero (or Cordoeiro) authored ''

Pardes Rimonim'', an organised, exhaustive compilation of kabbalistic teachings on a variety of subjects up to that point. Cordovero headed the academy of Tzfat until his death, when

Isaac Luria

Isaac ben Solomon Luria Ashkenazi (1534Fine 2003, p24/ref> – July 25, 1572) ( he, יִצְחָק בן שלמה לוּרְיָא אשכנזי ''Yitzhak Ben Sh'lomo Lurya Ashkenazi''), commonly known in Jewish religious circles as "Ha'ARI" (mean ...

rose to prominence. Rabbi Moshe's disciple

Eliyahu De Vidas

Eliyahu de Vidas (1518–1587, Hebron) was a 16th-century rabbi in Ottoman Palestine. He was primarily a disciple of Rabbis Moses ben Jacob Cordovero (known as the ''Ramak'') and also Isaac Luria.Fine 2003, pp81 "Cordovero was the teacher of what ...

authored the classic work, ''Reishit Chochma'', combining kabbalistic and ''mussar'' (moral) teachings.

Chaim Vital also studied under Cordovero, but with the arrival of Luria became his main disciple. Vital claimed to be the only one authorised to transmit the Ari's teachings, though other disciples also published books presenting Luria's teachings.

The Oriental Kabbalist tradition continues until today among Sephardi and Mizrachi Hakham sages and study circles. Among leading figures were the Yemenite

Shalom Sharabi

Sar Shalom Sharabi ( he, שר שלום מזרחי דידיע שרעבי), also known as the Rashash, the Shemesh or Ribbi Shalom Mizraḥi deyedi`a Sharabi (1720–1777), was a Yemenite Rabbi, Halachist, Chazzan and Kabbalist. In later life, ...

(1720–1777) of the

Beit El Synagogue

Beit El Kabbalist yeshiva (Beit El means "House of God") (also: ''Midrash Hasidim'' 'School of the Devout' or ''Yeshivat haMekubalim, Yeshiva of the Kabbalists') is a center of kabbalistic study in Jerusalem. Today it consists of two buildings, on ...

, the Jerusalemite

Hida (1724–1806), the Baghdad leader

Ben Ish Chai

Yosef Hayim (1 September 1835 – 30 August 1909) ( Iraqi Hebrew: Yoseph Ḥayyim; he, יוסף חיים מבגדאד) was a leading Baghdadi ''hakham'' (Sephardi rabbi), authority on ''halakha'' (Jewish law), and Master Kabbalist. He is best ...

(1832–1909), and the

Abuhatzeira

Abuhatzeira (Hebrew pronunciation) or Abu Hasira (Arabic) is the surname of a family of rabbis. Notable members of the family include, chronologically:

*Yaakov Abuhatzeira (1806–1880), Moroccan rabbi, son of the patriarch of the family, R. Shmue ...

dynasty.

''Maharal''

One of the most innovative theologians in early-modern Judaism was

Judah Loew ben Bezalel (1525–1609) known as the "Maharal of Prague". Many of his written works survive and are studied for their unusual combination of the mystical and philosophical approaches in Judaism. While conversant in Kabbalistic learning, he expresses Jewish mystical thought in his own individual approach without reference to Kabbalistic terms. The Maharal is most well known in popular culture for the legend of the

golem

A golem ( ; he, , gōlem) is an animated, anthropomorphic being in Jewish folklore, which is entirely created from inanimate matter (usually clay or mud). The most famous golem narrative involves Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the late 16th-century ...

of Prague, associated with him in folklore. However, his thought influenced Hasidism, for example being studied in the introspective Przysucha school. During the 20th century,

Isaac Hutner

Yitzchak (Isaac) Hutner ( he, יצחק הוטנר; 1906–1980) was an American Orthodox rabbi and rosh yeshiva (dean).

Originally from Warsaw, Hutner first studied the Torah in Slabodka. He then traveled to Mandatory Palestine where he became a ...

(1906–1980) continued to spread the Maharal's works indirectly through his own teachings and publications within the non-Hasidic yeshiva world.

Sabbatian antinomian movements

The spiritual and mystical yearnings of many Jews remained frustrated after the death of Isaac Luria and his disciples and colleagues. No hope was in sight for many following the devastation and mass killings of the

pogrom

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russia ...

s that followed in the wake of the

Chmielnicki Uprising

The Khmelnytsky Uprising,; in Ukraine known as Khmelʹnychchyna or uk, повстання Богдана Хмельницького; lt, Chmelnickio sukilimas; Belarusian: Паўстанне Багдана Хмяльніцкага; russian: � ...

(1648–1654), the largest single massacre of Jews until the Holocaust, and it was at this time that a controversial scholar by the name of

Sabbatai Zevi (1626–1676) captured the hearts and minds of the Jewish masses of that time with the promise of a newly minted messianic

Millennialism

Millennialism (from millennium, Latin for "a thousand years") or chiliasm (from the Greek equivalent) is a belief advanced by some religious denominations that a Golden Age or Paradise will occur on Earth prior to the final judgment and future ...

in the form of his own personage.

His charisma, mystical teachings that included repeated pronunciations of the holy

Tetragrammaton

The Tetragrammaton (; ), or Tetragram, is the four-letter Hebrew language, Hebrew theonym (transliterated as YHWH), the name of God in the Hebrew Bible. The four letters, written and read from right to left (in Hebrew), are ''yodh'', ''he (l ...

in public, tied to an unstable personality, and with the help of his greatest enthusiast,

Nathan of Gaza, convinced the Jewish masses that the Jewish Messiah had finally come. It seemed that the esoteric teachings of Kabbalah had found their "champion" and had triumphed, but this era of Jewish history unravelled when Zevi became an

apostate

Apostasy (; grc-gre, ἀποστασία , 'a defection or revolt') is the formal disaffiliation from, abandonment of, or renunciation of a religion by a person. It can also be defined within the broader context of embracing an opinion that ...

to Judaism by converting to Islam after he was arrested by the Ottoman Sultan and threatened with execution for attempting a plan to conquer the world and rebuild the

Temple in Jerusalem

The Temple in Jerusalem, or alternatively the Holy Temple (; , ), refers to the two now-destroyed religious structures that served as the central places of worship for Israelites and Jews on the modern-day Temple Mount in the Old City of Jerusa ...

. Unwilling to give up their messianic expectations, a minority of Zevi's Jewish followers converted to Islam along with him.

Many of his followers, known as

Sabbatians, continued to worship him in secret, explaining his conversion not as an effort to save his life but to recover the sparks of the holy in each religion, and most leading rabbis were always on guard to root them out. The

Dönmeh movement in modern Turkey is a surviving remnant of the Sabbatian schism. Theologies developed by leaders of Sabbatian movements dealt with

antinomian redemption of the realm of impurity through sin, based on Lurianic theory. Moderate views reserved this dangerous task for the divine messiah Sabbatai Zevi alone, while his followers remained observant Jews. Radical forms spoke of the messianic transcendence of Torah, and required Sabbatean followers to emulate him, either in private or publicly.

Due to the chaos caused in the Jewish world, the rabbinic prohibition against studying Kabbalah established itself firmly within the Jewish religion. One of the conditions allowing a man to study and engage himself in the Kabbalah was to be at least forty years old. This age requirement came about during this period and is not Talmudic in origin but rabbinic. Many Jews are familiar with this ruling, but are not aware of its origins. Moreover, the prohibition is not halakhic in nature. According to Moses Cordovero, halakhically, one must be of age twenty to engage in the Kabbalah. Many famous kabbalists, including the ARI, Rabbi Nachman of Breslov,

Yehuda Ashlag, were younger than twenty when they began.

The Sabbatian movement was followed by that of the

Frankists

Frankism was a heretical Sabbatean Jewish religious movement of the 18th and 19th centuries, centered on the leadership of the Jewish Messiah claimant Jacob Frank, who lived from 1726 to 1791. Frank rejected religious norms and said that his fol ...

, disciples of

Jacob Frank

Jacob Joseph Frank ( he, יעקב פרנק; pl, Jakub Józef Frank; born Jakub Lejbowicz; 1726 – December 10, 1791) was a Polish Jews, Polish-Jewish religious leader who claimed to be the reincarnation of the self-proclaimed messiah Sabbata ...

(1726–1791), who eventually became an apostate to Judaism by apparently converting to

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

. Frank took the Sabbatean impulse to its nihilistic end, declaring himself part of a messianic trinity along with his daughter, and that breaking all of Torah was its fulfilment. This era of disappointment did not stem the Jewish masses' yearnings for "mystical" leadership.

Modern era

Traditional Kabbalah

Moshe Chaim Luzzatto

Moshe Chaim Luzzatto ( he, משה חיים לוצאטו, also ''Moses Chaim'', ''Moses Hayyim'', also ''Luzzato'') (1707 – 16 May 1746 (26 ''Iyar'' 5506)), also known by the Hebrew acronym RaMCHaL (or RaMHaL, ), was a prominent Italia ...

(1707–1746), based in Italy, was a precocious Talmudic scholar who deduced a need for the public teaching and study of Kabbalah. He established a yeshiva for Kabbalah study and actively recruited students. He wrote copious manuscripts in an appealing clear Hebrew style, all of which gained the attention of both admirers and rabbinical critics, who feared another "

Sabbatai Zevi" (false messiah) in the making. His rabbinical opponents forced him to close his school, hand over and destroy many of his most precious unpublished kabbalistic writings, and go into exile in the Netherlands. He eventually moved to the

Land of Israel

The Land of Israel () is the traditional Jewish name for an area of the Southern Levant. Related biblical, religious and historical English terms include the Land of Canaan, the Promised Land, the Holy Land, and Palestine (see also Isra ...

. Some of his most important works, such as ''

Derekh Hashem

''Derech HaShem'' (The "Way of the Name") is a philosophical text written in the early 1740s by Rabbi Moshe Chaim Luzzatto. It is considered one of the quintessential handbooks of Jewish thought.

The text covers a vast gamut of philosophical to ...

'', survive and serve as a gateway to the world of Jewish mysticism.

Elijah of Vilna

Elijah ben Solomon Zalman, ( he , ר' אליהו בן שלמה זלמן ''Rabbi Eliyahu ben Shlomo Zalman'') known as the Vilna Gaon (Yiddish: דער װילנער גאון ''Der Vilner Gaon'', pl, Gaon z Wilna, lt, Vilniaus Gaonas) or Elijah of ...

(Vilna Gaon) (1720–1797), based in Lithuania, had his teachings encoded and publicised by his disciples, such as

Chaim Volozhin's posthumously published the mystical-ethical work ''

Nefesh HaChaim

Chaim of Volozhin (also known as Chaim ben Yitzchok of Volozhin or Chaim Ickovits; January 21, 1749 – June 14, 1821)Jewish Encyclopedia Bibliography: Samuel Joseph Fuenn, Fuenn, Keneset Yisrael, pp. 347–349; idem, Kiryah Ne'emanah, pp ...

''. He staunchly opposed the new Hasidic movement and warned against their public displays of religious fervour inspired by the mystical teachings of their rabbis. Although the Vilna Gaon did not look with favor on the Hasidic movement, he did not prohibit the study and engagement in the Kabbalah. This is evident from his writings in the ''Even Shlema''. "He that is able to understand secrets of the Torah and does not try to understand them will be judged harshly, may God have mercy". (The Vilna Gaon, ''Even Shlema'', 8:24). "The Redemption will only come about through learning Torah, and the essence of the Redemption depends upon learning Kabbalah" (The Vilna Gaon, ''Even Shlema'', 11:3).

In the Oriental tradition of Kabbalah, Shalom Sharabi (1720–1777) from Yemen was a major esoteric clarifier of the works of the Ari. The Beit El Synagogue, "yeshivah of the kabbalists", which he came to head, was one of the few communities to bring Lurianic meditation into communal prayer.

In the 20th century, Yehuda Ashlag (1885—1954) in Mandate Palestine became a leading esoteric kabbalist in the traditional mode, who translated the Zohar into Hebrew with a new approach in Lurianic Kabbalah.

Hasidic Judaism

Yisrael ben Eliezer Baal Shem Tov

Yisrael ben Eliezer Baal Shem Tov (1698–1760), founder of Hasidism in the area of the Ukraine, spread teachings based on Lurianic Kabbalah, but adapted to a different aim of immediate psychological perception of Divine Omnipresence amidst the mundane. The emotional, ecstatic fervour of early Hasidism developed from previous

Nistarim circles of mystical activity, but instead sought communal revival of the common folk by reframing Judaism around the central principle of

devekut (mystical cleaving to God) for all. This new approach turned formerly esoteric elite kabbalistic theory into a popular social mysticism movement for the first time, with its own doctrines, classic texts, teachings and customs. From the Baal Shem Tov sprang the wide ongoing schools of Hasidic Judaism, each with different approaches and thought. Hasidism instituted a new concept of

Tzadik

Tzadik ( he, צַדִּיק , "righteous ne, also ''zadik'', ''ṣaddîq'' or ''sadiq''; pl. ''tzadikim'' ''ṣadiqim'') is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The ...

leadership in Jewish mysticism, where the elite scholars of mystical texts now took on a social role as embodiments and intercessors of Divinity for the masses. With the 19th-century consolidation of the movement,

leadership

Leadership, both as a research area and as a practical skill, encompasses the ability of an individual, group or organization to "lead", influence or guide other individuals, teams, or entire organizations. The word "leadership" often gets view ...

became dynastic.

Among later Hasidic schools

Rebbe Nachman of Breslov

Nachman of Breslov ( he, רַבִּי נַחְמָן מִבְּרֶסְלֶב ''Rabbī'' ''Naḥmān mīBreslev''), also known as Reb Nachman of Bratslav, Reb Nachman Breslover ( yi, רבי נחמן ברעסלאווער ''Rebe Nakhmen Breslover'' ...

(1772–1810), the great-grandson of the Baal Shem Tov, revitalised and further expanded the latter's teachings, amassing a following of thousands in Ukraine, Belarus, Lithuania and Poland. In a unique amalgam of Hasidic and ''

Mitnaged'' approaches, Rebbe Nachman emphasised study of both Kabbalah and serious Torah scholarship to his disciples. His teachings also differed from the way other Hasidic groups were developing, as he rejected the idea of hereditary

Hasidic dynasties and taught that each Hasid must "search for the ''

tzaddik

Tzadik ( he, צַדִּיק , "righteous ne, also ''zadik'', ''ṣaddîq'' or ''sadiq''; pl. ''tzadikim'' ''ṣadiqim'') is a title in Judaism given to people considered righteous, such as biblical figures and later spiritual masters. The ...

'' ('saintly/righteous person')" for himself and within himself.

The

Habad-Lubavitch intellectual school of Hasidism broke away from General-Hasidism's emotional faith orientation, by making the mind central as the route to the internal heart. Its texts combine what they view as rational investigation with explanation of Kabbalah through articulating unity in a common Divine essence. In recent times, the

messianic element latent in Hasidism has come to the fore in Habad.

Haskalah opposition to mysticism

The Jewish Haskalah () enlightenment movement from the late 1700s renewed an ideology of rationalism in Judaism, giving birth to

critical Judaic scholarship. It presented Judaism in apologetic terms, stripped of mysticism and myth, in line with

Jewish emancipation

Jewish emancipation was the process in various nations in Europe of eliminating Jewish disabilities, e.g. Jewish quotas, to which European Jews were then subject, and the recognition of Jews as entitled to equality and citizenship rights. It incl ...

. Many foundational historians of Judaism such as

Heinrich Graetz, criticised Kabbalah as a foreign import that compromised historical Judaism. In the 20th century

Gershom Scholem overturned Jewish historiography, presenting the centrality of Jewish mysticism and Kabbalah to historical Judaism, and their subterranean life as the true creative renewing spirit of Jewish thought and culture. His influence contributed to the flourishing of

Jewish mysticism academia today, its impact on wider intellectual currents, and the contribution of mystical spirituality in modernist

Jewish denominations

Jewish religious movements, sometimes called "religious denomination, denominations", include different groups within Judaism which have developed among Jews from ancient times. Today, the most prominent divisions are between traditionalist Ortho ...

today. Traditionalist Kabbalah and Hasidism, meanwhile, continued outside the academic interest in it.

20th-century influence

Jewish mysticism has influenced the thought of some major Jewish theologians, philosophers, writers and thinkers in the 20th century, outside of Kabbalistic or Hasidic traditions. The first Chief Rabbi of Mandate Palestine,

Abraham Isaac Kook

Abraham Isaac Kook (; 7 September 1865 – 1 September 1935), known as Rav Kook, and also known by the acronym HaRaAYaH (), was an Orthodox rabbi, and the first Ashkenazi Chief Rabbi of British Mandatory Palestine. He is considered to be one ...

was a mystical thinker who drew heavily on Kabbalistic notions through his own poetic terminology. His writings are concerned with fusing the false divisions between sacred and secular, rational and mystical, legal and imaginative. Students of

Joseph B. Soloveitchik

Joseph Ber Soloveitchik ( he, יוסף דב הלוי סולובייצ׳יק ''Yosef Dov ha-Levi Soloveychik''; February 27, 1903 – April 9, 1993) was a major American Orthodox rabbi, Talmudist, and modern Jewish philosopher. He was a scion o ...

, figurehead of American

Modern Orthodox Judaism

Modern Orthodox Judaism (also Modern Orthodox or Modern Orthodoxy) is a movement within Orthodox Judaism that attempts to synthesize Jewish values and the observance of Jewish law with the secular, modern world.

Modern Orthodoxy draws on sever ...

have read the influence of Kabbalistic symbols in his philosophical works.

Neo-Hasidism

Neo-Hasidism, Neochassidut, or Neo-Chassidus, is an approach to Judaism in which people learn beliefs and practices of Hasidic Judaism, and incorporate it into their own lives or prayer communities, yet without formally joining a Hasidic group. O ...

, rather than Kabbalah, shaped

Martin Buber's philosophy of dialogue and

Abraham Joshua Heschel's

Conservative Judaism

Conservative Judaism, known as Masorti Judaism outside North America, is a Jewish religious movement which regards the authority of ''halakha'' (Jewish law) and traditions as coming primarily from its people and community through the generatio ...

. Lurianic symbols of Tzimtzum and Shevirah have informed

Holocaust theologians.

Gershom Scholem's central academic influence on reshaping Jewish historiography in favour of myth and imagination, made historical arcane Kabbalah of relevance to wide intellectual discourse in the 20th century.

Moshe Idel

Moshe Idel ( he, משה אידל; born January 19, 1947) is a Romanian-Israeli historian and philosopher of Jewish mysticism. He is Emeritus Max Cooper Professor in Jewish Thought at the Hebrew University, Jerusalem, and a Senior Researcher at the ...

traces the influences of Kabbalistic and Hasidic concepts on diverse thinkers such as

Walter Benjamin

Walter Bendix Schönflies Benjamin (; ; 15 July 1892 – 26 September 1940) was a German Jewish philosopher, cultural critic and essayist.

An eclectic thinker, combining elements of German idealism, Romanticism, Western Marxism, and Jewish mys ...

,

Jacques Derrida

Jacques Derrida (; ; born Jackie Élie Derrida; See also . 15 July 1930 – 9 October 2004) was an Algerian-born French philosopher. He developed the philosophy of deconstruction, which he utilized in numerous texts, and which was developed t ...

,

Franz Kafka

Franz Kafka (3 July 1883 – 3 June 1924) was a German-speaking Bohemian novelist and short-story writer, widely regarded as one of the major figures of 20th-century literature. His work fuses elements of realism and the fantastic. It ...

,

Franz Rosenzweig

Franz Rosenzweig (, ; 25 December 1886 – 10 December 1929) was a German theologian, philosopher, and translator.

Early life and education

Franz Rosenzweig was born in Kassel, Germany, to an affluent, minimally observant Jewish family. His fa ...

,

Arnaldo Momigliano

Arnaldo Dante Momigliano (5 September 1908 – 1 September 1987) was an Italian historian of classical antiquity, known for his work in historiography, and characterised by Donald Kagan as "the world's leading student of the writing of history i ...

,

Paul Celan

Paul Celan (; ; 23 November 1920 – c. 20 April 1970) was a Romanian-born German-language poet and translator. He was born as Paul Antschel to a Jewish family in Cernăuți (German: Czernowitz), in the then Kingdom of Romania (now Chernivtsi, U ...

and

George Steiner

Francis George Steiner, FBA (April 23, 1929 – February 3, 2020) was a Franco-American literary critic, essayist, philosopher, novelist, and educator. He wrote extensively about the relationship between language, literature and society, and the ...

.

Harold Bloom has seen Kabbalistic hermeneutics as the paradigm for western literary criticism. Sanford Drob discusses the direct and indirect influence of Kabbalah on the

depth psychologies of

Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies explained as originatin ...

and

Carl Jung

Carl Gustav Jung ( ; ; 26 July 1875 – 6 June 1961) was a Swiss psychiatrist and psychoanalyst who founded analytical psychology. Jung's work has been influential in the fields of psychiatry, anthropology, archaeology, literature, philo ...

, as well as modern and postmodern philosophers, in his project to develop new intellectual relevance and open dialogue for kabbalah. The interaction of Kabbalah with modern physics, as with other mystical traditions, has generated its own literature. Traditional Kabbalist

Yitzchak Ginsburgh brings esoteric dimensions of advanced kabbalistic

symmetry

Symmetry (from grc, συμμετρία "agreement in dimensions, due proportion, arrangement") in everyday language refers to a sense of harmonious and beautiful proportion and balance. In mathematics, "symmetry" has a more precise definit ...

into relationship with mathematics and the sciences, including renaming the

elementary particles of Quantum theory with Kabbalistic Hebrew names, and developing kabbalistic approaches to debates in

Evolutionary theory.

Concepts

Concealed and revealed God

The nature of the divine prompted kabbalists to envision two aspects to God: (a) God in essence, absolutely

transcendent, unknowable, limitless

divine simplicity

In theology, the doctrine of divine simplicity says that God is simple (without parts). The general idea can be stated in this way: The being of God is identical to the "attributes" of God. Characteristics such as omnipresence, goodness, trut ...

beyond revelation, and (b) God in manifestation, the revealed persona of God through which he creates and sustains and relates to humankind. Kabbalists speak of the first as ''

Ein/Ayn Sof'' (אין סוף "the infinite/endless", literally "there is no end"). Of the impersonal ''Ein Sof'' nothing can be grasped. However, the second aspect of divine emanations, are accessible to human perception, dynamically interacting throughout spiritual and physical existence, reveal the divine

immanently, and are bound up in the life of man. Kabbalists believe that these two aspects are not contradictory but complement one another, emanations

mystically revealing the concealed mystery from within the

Godhead

Godhead (from Middle English ''godhede'', "godhood", and unrelated to the modern word "head"), may refer to:

* Deity

* Divinity

* Conceptions of God

* In Abrahamic religions

** Godhead in Judaism, the unknowable aspect of God, which lies beyo ...

.

As a term describing the Infinite Godhead beyond Creation, Kabbalists viewed the ''Ein Sof'' itself as too sublime to be referred to directly in the Torah. It is not a

Holy Name in Judaism, as no name could contain a revelation of the Ein Sof. Even terming it "No End" is an inadequate representation of its true nature, the description only bearing its designation in relation to Creation. However, the Torah does narrate God speaking in the first person, most memorably the first word of the

Ten Commandments

The Ten Commandments (Biblical Hebrew עשרת הדברים \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדְּבָרִים, ''aséret ha-dvarím'', lit. The Decalogue, The Ten Words, cf. Mishnaic Hebrew עשרת הדיברות \ עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְ� ...

, a reference without any description or name to the simple

Divine essence (termed also ''Atzmus Ein Sof'' – Essence of the Infinite) beyond even the duality of Infinitude/Finitude. In contrast, the term Ein Sof describes the Godhead as Infinite lifeforce first cause, continuously keeping all Creation in existence. The

Zohar

The ''Zohar'' ( he, , ''Zōhar'', lit. "Splendor" or "Radiance") is a foundational work in the literature of Jewish mystical thought known as Kabbalah. It is a group of books including commentary on the mystical aspects of the Torah (the five ...

reads the

first words of Genesis, ''BeReishit Bara Elohim – In the beginning God created'', as "''With'' (the level of) ''Reishit (Beginning)'' (the Ein Sof) ''created

Elohim

''Elohim'' (: ), the plural of (), is a Hebrew word meaning "gods". Although the word is plural, in the Hebrew Bible it usually takes a singular verb and refers to a single deity, particularly (but not always) the God of Israel. At other times ...

'' (God's manifestation in creation)":

The structure of emanations has been described in various ways:

Sephirot (divine attributes) and

Partzufim (divine "faces"),

Ohr (spiritual light and flow),

Names of God and the supernal

Torah

The Torah (; hbo, ''Tōrā'', "Instruction", "Teaching" or "Law") is the compilation of the first five books of the Hebrew Bible, namely the books of Genesis, Exodus, Leviticus, Numbers and Deuteronomy. In that sense, Torah means the s ...

,

Olamot (Spiritual Worlds), a

Divine Tree and

Archetypal Man,

Angelic Chariot and Palaces, male and female, enclothed layers of reality, inwardly holy vitality and external Kelipot shells,

613 channels ("limbs" of the King) and the divine Souls of

Man. These symbols are used to describe various levels and aspects of Divine manifestation, from the ''

Pnimi'' (inner) dimensions to the ''

Hitzoni'' (outer). It is solely in relation to the emanations, certainly not the

Ein Sof

Ein Sof, or Eyn Sof (, he, '; meaning "infinite", ), in Kabbalah, is understood as God prior to any self-manifestation in the production of any spiritual realm, probably derived from Solomon ibn Gabirol's ( 1021 – 1070) term, "the Endless O ...

Ground of all Being, that Kabbalah uses

anthropomorphic symbolism to relate psychologically to divinity. Kabbalists debated the validity of anthropomorphic symbolism, between its disclosure as mystical allusion, versus its instrumental use as allegorical metaphor; in the language of the Zohar, symbolism "touches yet does not touch" its point.

Sephirot

The ''Sephirot'' (also spelled "sefirot"; singular ''sefirah'') are the ten emanations and attributes of God with which he continually sustains the existence of the universe. The Zohar and other Kabbalistic texts elaborate on the emergence of the sephirot from a state of concealed potential in the ''Ein Sof'' until their manifestation in the mundane world. In particular, Moses ben Jacob Cordovero (known as "the Ramak"), describes how God emanated the myriad details of finite reality out of the absolute unity of Divine light via the ten sephirot, or vessels.

Comparison of the Ramak's counting with Luria's, describes dual rational and unconscious aspects of Kabbalah. Two metaphors are used to describe the ''sephirot'', their

theocentric

Theocentricism is the belief that God is the central aspect to existence, as opposed to anthropocentrism and existentialism. In this view, meaning and value of actions done to people or the environment are attributed to God. The tenets of theocent ...

manifestation as the Trees of Life and Knowledge, and their

anthropocentric correspondence in man, exemplified as

Adam Kadmon. This dual-directional perspective embodies the cyclical, inclusive nature of the divine flow, where alternative divine and human perspectives have validity. The central metaphor of man allows human understanding of the sephirot, as they correspond to the psychological faculties of the soul, and incorporate masculine and feminine aspects after Genesis 1:27 ("God created man in His own image, in the image of God He created him, male and female He created them"). Corresponding to the last ''sefirah'' in Creation is the indwelling shekhinah (Feminine Divine Presence). Downward flow of divine Light in Creation forms the supernal

Four Worlds;

Atziluth,

Beri'ah,

Yetzirah

Yetzirah (also known as ''Olam Yetsirah'', עוֹלָם יְצִירָה in Hebrew) is the third of four worlds in the Kabbalistic Tree of Life, following Atziluth and Beri'ah and preceding Assiah. It is known as the "World of Formation".

"Yet ...

and

Assiah

Assiah (also 'Asiya'MEIJERS, L. D., and J. TENNEKES. “SPIRIT AND MATTER IN THE COSMOLOGY OF CHASSIDIC JUDAISM.” Symbolic Anthropology in the Netherlands, edited by P.E. DE JOSSELIN DE JONG and ERIK SCHWIMMER, vol. 95, Brill, 1982, pp. 200–21 ...