John Wilkes Booth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Wilkes Booth (May 10, 1838 – April 26, 1865) was an American stage actor who assassinated United States President

As a boy, Booth was athletic and popular, and he became skilled at horsemanship and fencing. He attended the Bel Air Academy and was an indifferent student whom the headmaster described as "not deficient in intelligence, but disinclined to take advantage of the educational opportunities offered him. Each day he rode back and forth from farm to school, taking more interest in what happened along the way than in reaching his classes on time". In 1850–1851, he attended the

As a boy, Booth was athletic and popular, and he became skilled at horsemanship and fencing. He attended the Bel Air Academy and was an indifferent student whom the headmaster described as "not deficient in intelligence, but disinclined to take advantage of the educational opportunities offered him. Each day he rode back and forth from farm to school, taking more interest in what happened along the way than in reaching his classes on time". In 1850–1851, he attended the

Booth made his stage debut at age 17 on August 14, 1855, in the supporting role of the Earl of Richmond in '' Richard III'' at Baltimore's Charles Street Theatre.Smith, pp. 61–62. The audience jeered at him when he missed some of his lines. He also began acting at Baltimore's

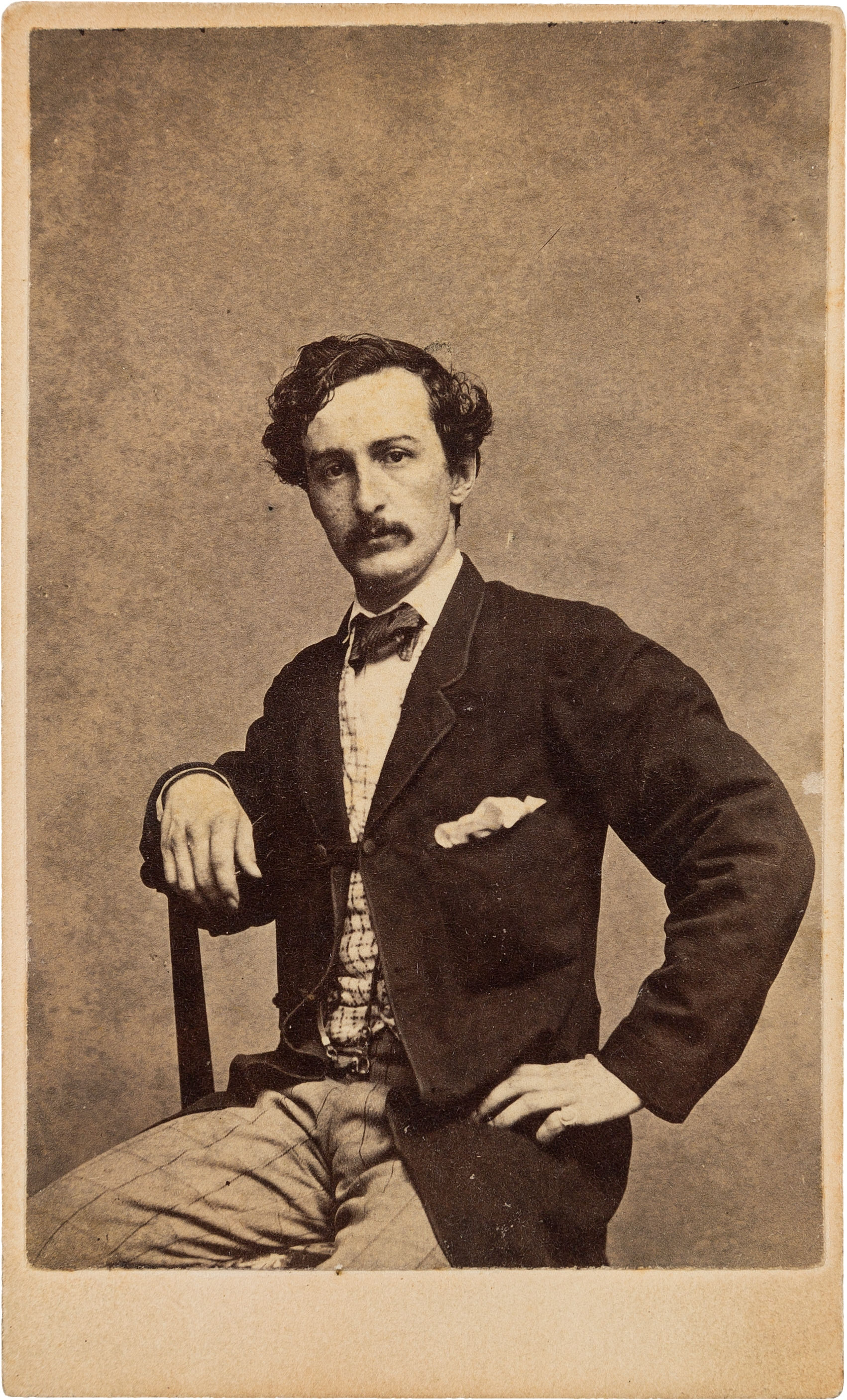

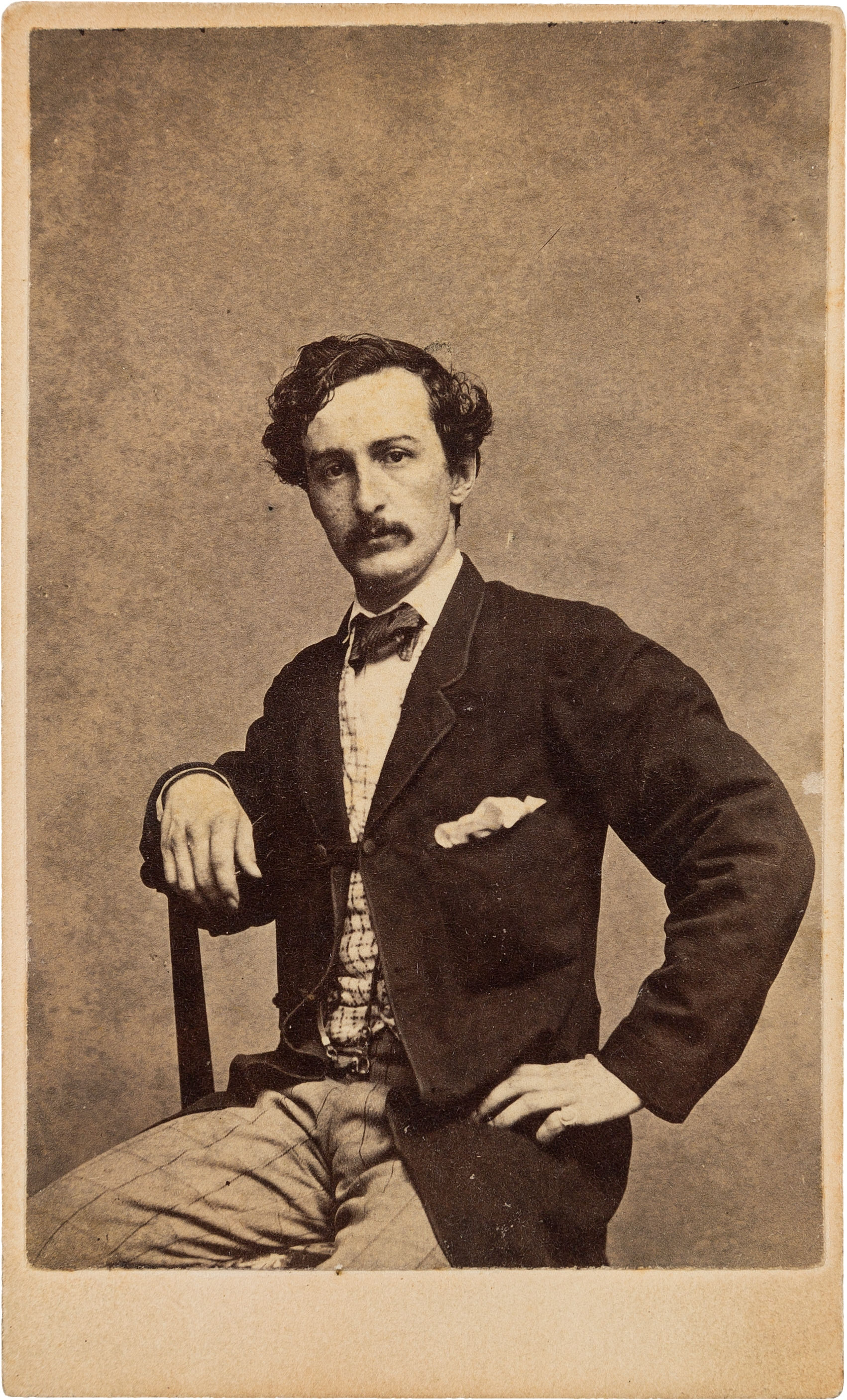

Booth made his stage debut at age 17 on August 14, 1855, in the supporting role of the Earl of Richmond in '' Richard III'' at Baltimore's Charles Street Theatre.Smith, pp. 61–62. The audience jeered at him when he missed some of his lines. He also began acting at Baltimore's  Some critics called Booth "the handsomest man in America" and a "natural genius", and noted his having an "astonishing memory"; others were mixed in their estimation of his acting. He stood tall, had jet-black hair, and was lean and athletic. Noted Civil War reporter George Alfred Townsend described him as a "muscular, perfect man" with "curling hair, like a Corinthian capital". Booth's stage performances were often characterized by his contemporaries as acrobatic and intensely physical, with him leaping upon the stage and gesturing with passion. He was an excellent swordsman, although a fellow actor once recalled that Booth occasionally cut himself with his own sword.

Historian Benjamin Platt Thomas wrote that Booth "won celebrity with theater-goers by his romantic personal attraction", and that he was "too impatient for hard study" and his "brilliant talents had failed of full development." Author Gene Smith wrote that Booth's acting may not have been as precise as his brother Edwin's, but his strikingly handsome appearance enthralled women. As the 1850s drew to a close, Booth was becoming wealthy as an actor, earning $20,000 a year (equivalent to about $ more recently).

Some critics called Booth "the handsomest man in America" and a "natural genius", and noted his having an "astonishing memory"; others were mixed in their estimation of his acting. He stood tall, had jet-black hair, and was lean and athletic. Noted Civil War reporter George Alfred Townsend described him as a "muscular, perfect man" with "curling hair, like a Corinthian capital". Booth's stage performances were often characterized by his contemporaries as acrobatic and intensely physical, with him leaping upon the stage and gesturing with passion. He was an excellent swordsman, although a fellow actor once recalled that Booth occasionally cut himself with his own sword.

Historian Benjamin Platt Thomas wrote that Booth "won celebrity with theater-goers by his romantic personal attraction", and that he was "too impatient for hard study" and his "brilliant talents had failed of full development." Author Gene Smith wrote that Booth's acting may not have been as precise as his brother Edwin's, but his strikingly handsome appearance enthralled women. As the 1850s drew to a close, Booth was becoming wealthy as an actor, earning $20,000 a year (equivalent to about $ more recently).

When the Civil War began on April 12, 1861, Booth was starring in

When the Civil War began on April 12, 1861, Booth was starring in 's review the next day called Booth "the most promising young actor on the American stage".

Starting in January 1863, he returned to the Boston Museum for a series of plays, including the role of villain Duke Pescara in ''The Apostate'', that won him acclaim from audiences and critics. Back in Washington in April, he played the title roles in ''Hamlet'' and ''Richard III,'' one of his favorites. He was billed as "The Pride of the American People, A Star of the First Magnitude," and the critics were equally enthusiastic. The ''National Republican'' drama critic said that Booth "took the hearts of the audience by storm" and termed his performance "a complete triumph". At the beginning of July 1863, Booth finished the acting season at  On November 25, 1864, Booth performed for the only time with his brothers

On November 25, 1864, Booth performed for the only time with his brothers

Booth was pro-Confederate, but his family was divided, like many Marylanders. He was outspoken in his love of the South, and equally outspoken in his hatred of Lincoln. As the Civil War went on, Booth increasingly quarreled with his brother Edwin, who declined to make stage appearances in the South and refused to listen to John Wilkes' fiercely partisan denunciations of the North and Lincoln. In early 1863, Booth was arrested in

Booth was pro-Confederate, but his family was divided, like many Marylanders. He was outspoken in his love of the South, and equally outspoken in his hatred of Lincoln. As the Civil War went on, Booth increasingly quarreled with his brother Edwin, who declined to make stage appearances in the South and refused to listen to John Wilkes' fiercely partisan denunciations of the North and Lincoln. In early 1863, Booth was arrested in

In October, Booth made an unexplained trip to

In October, Booth made an unexplained trip to

Historian Michael W. Kauffman wrote that, by targeting Lincoln and his two immediate successors to the presidency, Booth seems to have intended to decapitate the Union government and throw it into a state of panic and confusion. In 1865, however, the second presidential successor would have been the

Historian Michael W. Kauffman wrote that, by targeting Lincoln and his two immediate successors to the presidency, Booth seems to have intended to decapitate the Union government and throw it into a state of panic and confusion. In 1865, however, the second presidential successor would have been the

Federal troops combed the rural area's woods and swamps for Booth in the days following the assassination, as the nation experienced an outpouring of grief. On April 18, mourners waited seven abreast in a mile-long line outside the White House for the public viewing of the slain president, reposing in his open walnut casket in the black-draped East Room. A cross of lilies was at the head and roses covered the coffin's lower half. Thousands of mourners arriving on special trains jammed Washington for the next day's funeral, sleeping on hotel floors and even resorting to blankets spread outdoors on the

Federal troops combed the rural area's woods and swamps for Booth in the days following the assassination, as the nation experienced an outpouring of grief. On April 18, mourners waited seven abreast in a mile-long line outside the White House for the public viewing of the slain president, reposing in his open walnut casket in the black-draped East Room. A cross of lilies was at the head and roses covered the coffin's lower half. Thousands of mourners arriving on special trains jammed Washington for the next day's funeral, sleeping on hotel floors and even resorting to blankets spread outdoors on the  In the cities where the train stopped, 1.5 million people viewed Lincoln in his coffin. Aboard the train was Chauncey Depew, a New York politician and later president of the New York Central Railroad, who said, "As we sped over the rails at night, the scene was the most pathetic ever witnessed. At every crossroads the glare of innumerable torches illuminated the whole population, kneeling on the ground." Dorothy Kunhardt called the funeral train's journey "the mightiest outpouring of national grief the world had yet seen."

Mourners were viewing Lincoln's remains when the funeral train steamed into Harrisburg at 8:20 pm, while Booth and Herold were provided with a boat and compass by Jones to cross the Potomac at night on April 21. Instead of reaching Virginia, they mistakenly navigated upriver to a bend in the broad Potomac River, coming ashore again in Maryland on April 22. The 23-year-old Herold knew the area well, having frequently hunted there, and recognized a nearby farm as belonging to a Confederate sympathizer. The farmer led them to his son-in-law, Col. John J. Hughes, who provided the fugitives with food and a hideout until nightfall, for a second attempt to row across the river to Virginia.Smith, pp. 197–198. Booth wrote in his diary:

The pair finally reached the Virginia shore near Machodoc Creek before dawn on April 23. There, they made contact with Thomas Harbin, whom Booth had previously brought into his erstwhile kidnapping plot. Harbin took Booth and Herold to another Confederate agent in the area named William Bryant who supplied them with horses.

While Lincoln's funeral train was in New York City on April 24, Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty was dispatched from Washington at 2 p.m. with a detachment of 26 Union soldiers from the 16th New York Cavalry Regiment to capture Booth in Virginia,Smith, pp. 203–204. accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Everton Conger, an intelligence officer assigned by Lafayette Baker. The detachment steamed down the Potomac River on the boat ''John S. Ide'', landing at Belle Plain, Virginia, at 10 pm. The pursuers crossed the Rappahannock River and tracked Booth and Herold to Richard H. Garrett's farm, about south of Port Royal, Virginia. Booth and Herold had been led to the farm on April 24 by William S. Jett, a former private in the 9th Virginia Cavalry, whom they had met before crossing the Rappahannock. The Garretts were unaware of Lincoln's assassination; Booth was introduced to them as "James W. Boyd", a Confederate soldier, they were told, who had been wounded in the Siege of Petersburg, battle of Petersburg and was returning home.

Garrett's 11-year-old son Richard was an eyewitness to the event. In later years, he became a Baptist minister and widely lectured on the events of Booth's demise at his family's farm. In 1921, Garrett's lecture was published in the ''Confederate Veteran'' as the "True Story of the Capture of John Wilkes Booth." According to his account, Booth and Herold arrived at the Garretts' farm, located on the road to, and close to, Bowling Green, Virginia, Bowling Green. around 3 p.m. on Monday afternoon. Confederate mail delivery had ceased with the collapse of the Confederacy, he explained, so the Garretts were unaware of Lincoln's assassination. After having dinner with the Garretts that evening, Booth learned of the surrender of Johnston's army, the last Confederate armed force of any size. Its capitulation meant that the Civil War was unquestionably over and Booth's attempt to save the Confederacy by Lincoln's assassination had failed. The Garretts also finally learned of Lincoln's death and the substantial reward for Booth's capture. Booth, said Garrett, displayed no reaction other than to ask if the family would turn in the fugitive should they have the opportunity. Still not aware of their guest's true identity, one of the older Garrett sons offered that they might, if only because they needed the money. The next day, Booth told the Garretts that he intended to reach Mexico, drawing a route on a map of theirs. Biographer Theodore Roscoe said of Garrett's account, "Almost nothing written or testified in respect to the doings of the fugitives at Garrett's farm can be taken at face value. Nobody knows exactly what Booth said to the Garretts, or they to him."

In the cities where the train stopped, 1.5 million people viewed Lincoln in his coffin. Aboard the train was Chauncey Depew, a New York politician and later president of the New York Central Railroad, who said, "As we sped over the rails at night, the scene was the most pathetic ever witnessed. At every crossroads the glare of innumerable torches illuminated the whole population, kneeling on the ground." Dorothy Kunhardt called the funeral train's journey "the mightiest outpouring of national grief the world had yet seen."

Mourners were viewing Lincoln's remains when the funeral train steamed into Harrisburg at 8:20 pm, while Booth and Herold were provided with a boat and compass by Jones to cross the Potomac at night on April 21. Instead of reaching Virginia, they mistakenly navigated upriver to a bend in the broad Potomac River, coming ashore again in Maryland on April 22. The 23-year-old Herold knew the area well, having frequently hunted there, and recognized a nearby farm as belonging to a Confederate sympathizer. The farmer led them to his son-in-law, Col. John J. Hughes, who provided the fugitives with food and a hideout until nightfall, for a second attempt to row across the river to Virginia.Smith, pp. 197–198. Booth wrote in his diary:

The pair finally reached the Virginia shore near Machodoc Creek before dawn on April 23. There, they made contact with Thomas Harbin, whom Booth had previously brought into his erstwhile kidnapping plot. Harbin took Booth and Herold to another Confederate agent in the area named William Bryant who supplied them with horses.

While Lincoln's funeral train was in New York City on April 24, Lieutenant Edward P. Doherty was dispatched from Washington at 2 p.m. with a detachment of 26 Union soldiers from the 16th New York Cavalry Regiment to capture Booth in Virginia,Smith, pp. 203–204. accompanied by Lieutenant Colonel Everton Conger, an intelligence officer assigned by Lafayette Baker. The detachment steamed down the Potomac River on the boat ''John S. Ide'', landing at Belle Plain, Virginia, at 10 pm. The pursuers crossed the Rappahannock River and tracked Booth and Herold to Richard H. Garrett's farm, about south of Port Royal, Virginia. Booth and Herold had been led to the farm on April 24 by William S. Jett, a former private in the 9th Virginia Cavalry, whom they had met before crossing the Rappahannock. The Garretts were unaware of Lincoln's assassination; Booth was introduced to them as "James W. Boyd", a Confederate soldier, they were told, who had been wounded in the Siege of Petersburg, battle of Petersburg and was returning home.

Garrett's 11-year-old son Richard was an eyewitness to the event. In later years, he became a Baptist minister and widely lectured on the events of Booth's demise at his family's farm. In 1921, Garrett's lecture was published in the ''Confederate Veteran'' as the "True Story of the Capture of John Wilkes Booth." According to his account, Booth and Herold arrived at the Garretts' farm, located on the road to, and close to, Bowling Green, Virginia, Bowling Green. around 3 p.m. on Monday afternoon. Confederate mail delivery had ceased with the collapse of the Confederacy, he explained, so the Garretts were unaware of Lincoln's assassination. After having dinner with the Garretts that evening, Booth learned of the surrender of Johnston's army, the last Confederate armed force of any size. Its capitulation meant that the Civil War was unquestionably over and Booth's attempt to save the Confederacy by Lincoln's assassination had failed. The Garretts also finally learned of Lincoln's death and the substantial reward for Booth's capture. Booth, said Garrett, displayed no reaction other than to ask if the family would turn in the fugitive should they have the opportunity. Still not aware of their guest's true identity, one of the older Garrett sons offered that they might, if only because they needed the money. The next day, Booth told the Garretts that he intended to reach Mexico, drawing a route on a map of theirs. Biographer Theodore Roscoe said of Garrett's account, "Almost nothing written or testified in respect to the doings of the fugitives at Garrett's farm can be taken at face value. Nobody knows exactly what Booth said to the Garretts, or they to him."

Conger tracked down Jett and interrogated him, learning of Booth's location at the Garrett farm. Before dawn on April 26, the soldiers caught up with the fugitives, who were hiding in Garrett's tobacco barn. David Herold surrendered, but Booth refused Conger's demand to surrender, saying, "I prefer to come out and fight." The soldiers then set the barn on fire.Smith, pp. 210–213. As Booth moved about inside the blazing barn, Sergeant

Conger tracked down Jett and interrogated him, learning of Booth's location at the Garrett farm. Before dawn on April 26, the soldiers caught up with the fugitives, who were hiding in Garrett's tobacco barn. David Herold surrendered, but Booth refused Conger's demand to surrender, saying, "I prefer to come out and fight." The soldiers then set the barn on fire.Smith, pp. 210–213. As Booth moved about inside the blazing barn, Sergeant

Booth's body was shrouded in a blanket and tied to the side of an old farm wagon for the trip back to Belle Plain. There, his corpse was taken aboard the ironclad USS Montauk (1862), USS ''Montauk'' and brought to the Washington Navy Yard for identification and an autopsy. The body was identified there as Booth's by more than ten people who knew him. Among the identifying features used to make sure that the man that was killed was Booth was a tattoo on his left hand with his initials J.W.B., and a distinct scar on the back of his neck.

The third, fourth, and fifth vertebrae were removed during the autopsy to allow access to the bullet. These bones are still on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C. The body was then buried in a storage room at the Arsenal Penitentiary in 1865, and later moved to a warehouse at the Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington Arsenal on October 1, 1867.Smith, pp. 239–241. In 1869, the remains were once again identified before being released to the Booth family, where they were buried in the family plot at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, after a burial ceremony conducted by Fleming James, minister of Christ Episcopal Church, in the presence of more than 40 people. Russell Conwell visited homes in the vanquished former Confederate states during this time, and he found that hatred of Lincoln still smoldered. "Photographs of Wilkes Booth, with the last words of great martyrs printed upon its borders...adorn their drawing rooms".

Eight others implicated in Lincoln's assassination were tried by a military tribunal in Washington, D.C., and found guilty on June 30, 1865.

Booth's body was shrouded in a blanket and tied to the side of an old farm wagon for the trip back to Belle Plain. There, his corpse was taken aboard the ironclad USS Montauk (1862), USS ''Montauk'' and brought to the Washington Navy Yard for identification and an autopsy. The body was identified there as Booth's by more than ten people who knew him. Among the identifying features used to make sure that the man that was killed was Booth was a tattoo on his left hand with his initials J.W.B., and a distinct scar on the back of his neck.

The third, fourth, and fifth vertebrae were removed during the autopsy to allow access to the bullet. These bones are still on display at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Washington, D.C. The body was then buried in a storage room at the Arsenal Penitentiary in 1865, and later moved to a warehouse at the Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington Arsenal on October 1, 1867.Smith, pp. 239–241. In 1869, the remains were once again identified before being released to the Booth family, where they were buried in the family plot at Green Mount Cemetery in Baltimore, after a burial ceremony conducted by Fleming James, minister of Christ Episcopal Church, in the presence of more than 40 people. Russell Conwell visited homes in the vanquished former Confederate states during this time, and he found that hatred of Lincoln still smoldered. "Photographs of Wilkes Booth, with the last words of great martyrs printed upon its borders...adorn their drawing rooms".

Eight others implicated in Lincoln's assassination were tried by a military tribunal in Washington, D.C., and found guilty on June 30, 1865.

In response, the Maryland Historical Society published an account in 1913 by Baltimore mayor William M. Pegram, who had viewed Booth's remains upon the casket's arrival at the Weaver funeral home in Baltimore on February 18, 1869, for burial at Green Mount Cemetery. Pegram had known Booth well as a young man; he submitted a sworn statement that the body which he had seen in 1869 was Booth's. Others positively identified this body as Booth at the funeral home, including Booth's mother, brother, and sister, along with his dentist and other Baltimore acquaintances. In 1911, ''The New York Times'' had published an account by their reporter detailing the burial of Booth's body at the cemetery and those who were witnesses. The rumor periodically revived, as in the 1920s when a corpse was exhibited on a national tour by a carnival promoter and advertised as the "Man Who Shot Lincoln". According to a 1938 article in the ''Saturday Evening Post'', the exhibitor said that he obtained St. Helen's corpse from Bates' widow.

''The Lincoln Conspiracy (book), The Lincoln Conspiracy'' (1977) contended that there was a government plot to conceal Booth's escape, reviving interest in the story and prompting the display of St. Helen's mummified body in Chicago that year. The book sold more than one million copies and was made into a feature film called The Lincoln Conspiracy (film), ''The Lincoln Conspiracy'' which was theatrically released later that year. The 1998 book ''The Curse of Cain: The Untold Story of John Wilkes Booth'' contended that Booth had escaped, sought refuge in Japan, and eventually returned to the United States.

In 1994, two historians together with several descendants sought a court order for the exhumation of Booth's body at Green Mount Cemetery which was, according to their lawyer, "intended to prove or disprove longstanding theories on Booth's escape" by conducting a photo-superimposition analysis. The application was blocked by Baltimore Circuit Court Judge Joseph H. H. Kaplan, who cited, among other things, "the unreliability of petitioners' less-than-convincing escape/cover-up theory" as a major factor in his decision. The Maryland Court of Special Appeals upheld the ruling.Kauffman, ''American Brutus'', pp. 393–394.

In December 2010, descendants of Edwin Booth reported that they obtained permission to exhume the Shakespearean actor's body to obtain DNA samples to compare with a sample of his brother John's DNA to refute the rumor that John had escaped after the assassination. Bree Harvey, a spokesman from the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Edwin Booth is buried, denied reports that the family had contacted them and requested to exhume Edwin's body. The family hoped to obtain samples of John Wilkes's DNA from remains such as vertebrae stored at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Maryland. On March 30, 2013, museum spokesperson Carol Johnson announced that the family's request to extract DNA from the vertebrae had been rejected.

In response, the Maryland Historical Society published an account in 1913 by Baltimore mayor William M. Pegram, who had viewed Booth's remains upon the casket's arrival at the Weaver funeral home in Baltimore on February 18, 1869, for burial at Green Mount Cemetery. Pegram had known Booth well as a young man; he submitted a sworn statement that the body which he had seen in 1869 was Booth's. Others positively identified this body as Booth at the funeral home, including Booth's mother, brother, and sister, along with his dentist and other Baltimore acquaintances. In 1911, ''The New York Times'' had published an account by their reporter detailing the burial of Booth's body at the cemetery and those who were witnesses. The rumor periodically revived, as in the 1920s when a corpse was exhibited on a national tour by a carnival promoter and advertised as the "Man Who Shot Lincoln". According to a 1938 article in the ''Saturday Evening Post'', the exhibitor said that he obtained St. Helen's corpse from Bates' widow.

''The Lincoln Conspiracy (book), The Lincoln Conspiracy'' (1977) contended that there was a government plot to conceal Booth's escape, reviving interest in the story and prompting the display of St. Helen's mummified body in Chicago that year. The book sold more than one million copies and was made into a feature film called The Lincoln Conspiracy (film), ''The Lincoln Conspiracy'' which was theatrically released later that year. The 1998 book ''The Curse of Cain: The Untold Story of John Wilkes Booth'' contended that Booth had escaped, sought refuge in Japan, and eventually returned to the United States.

In 1994, two historians together with several descendants sought a court order for the exhumation of Booth's body at Green Mount Cemetery which was, according to their lawyer, "intended to prove or disprove longstanding theories on Booth's escape" by conducting a photo-superimposition analysis. The application was blocked by Baltimore Circuit Court Judge Joseph H. H. Kaplan, who cited, among other things, "the unreliability of petitioners' less-than-convincing escape/cover-up theory" as a major factor in his decision. The Maryland Court of Special Appeals upheld the ruling.Kauffman, ''American Brutus'', pp. 393–394.

In December 2010, descendants of Edwin Booth reported that they obtained permission to exhume the Shakespearean actor's body to obtain DNA samples to compare with a sample of his brother John's DNA to refute the rumor that John had escaped after the assassination. Bree Harvey, a spokesman from the Mount Auburn Cemetery in Cambridge, Massachusetts, where Edwin Booth is buried, denied reports that the family had contacted them and requested to exhume Edwin's body. The family hoped to obtain samples of John Wilkes's DNA from remains such as vertebrae stored at the National Museum of Health and Medicine in Maryland. On March 30, 2013, museum spokesperson Carol Johnson announced that the family's request to extract DNA from the vertebrae had been rejected.

Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

at Ford's Theatre

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in August 1863. The theater is infamous for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater bo ...

in Washington, D.C., on April 14, 1865. A member of the prominent 19th-century Booth theatrical family from Maryland

Maryland ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States. It shares borders with Virginia, West Virginia, and the District of Columbia to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and Delaware and the Atlantic Ocean to ...

, he was a noted actor who was also a Confederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

sympathizer; denouncing President Lincoln, he lamented the recent abolition of slavery in the United States

From the late 18th to the mid-19th century, various states of the United States of America allowed the enslavement of human beings, mostly of African Americans, Africans who had been transported from Africa during the Atlantic slave trade. The ...

.

Originally, Booth and his small group of conspirators had plotted to kidnap Lincoln to aid the Confederate cause. They later decided to murder him, as well as Vice President Andrew Johnson

Andrew Johnson (December 29, 1808July 31, 1875) was the 17th president of the United States, serving from 1865 to 1869. He assumed the presidency as he was vice president at the time of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. Johnson was a Dem ...

and Secretary of State William H. Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

. Although its Army of Northern Virginia

The Army of Northern Virginia was the primary military force of the Confederate States of America in the Eastern Theater of the American Civil War. It was also the primary command structure of the Department of Northern Virginia. It was most oft ...

, commanded by General Robert E. Lee

Robert Edward Lee (January 19, 1807 – October 12, 1870) was a Confederate general during the American Civil War, towards the end of which he was appointed the overall commander of the Confederate States Army. He led the Army of North ...

, had surrendered to the Union Army

During the American Civil War, the Union Army, also known as the Federal Army and the Northern Army, referring to the United States Army, was the land force that fought to preserve the Union (American Civil War), Union of the collective U.S. st ...

four days earlier, Booth believed that the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

remained unresolved because the Confederate Army of General Joseph E. Johnston

Joseph Eggleston Johnston (February 3, 1807 – March 21, 1891) was an American career army officer, serving with distinction in the United States Army during the Mexican–American War (1846–1848) and the Seminole Wars. After Virginia secede ...

continued fighting.

Booth shot President Lincoln once in the back of the head. Lincoln's death the next morning completed Booth's piece of the plot. Seward, severely wounded, recovered, whereas Vice President Johnson was never attacked. Booth fled on horseback to Southern Maryland

Southern Maryland is a geographical, cultural and historic region in Maryland composed of the state's southernmost counties on the Western Shore of the Chesapeake Bay. According to the state of Maryland, the region includes all of Calvert, Cha ...

; twelve days later, at a farm in rural Northern Virginia

Northern Virginia, locally referred to as NOVA or NoVA, comprises several counties and independent cities in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. It is a widespread region radiating westward and southward from Washington, D.C. Wit ...

, he was tracked down sheltered in a barn. Booth's companion David Herold

David Edgar Herold (June 16, 1842 – July 7, 1865) was an American pharmacist's assistant and accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. After the shooting, Herold accompanied Booth to the home of ...

surrendered, but Booth maintained a standoff. After the authorities set the barn ablaze, Union soldier Boston Corbett

Thomas H. "Boston" Corbett (January 29, 1832 – presumed dead September 1, 1894) was an American Union Army soldier who shot and killed U.S. president Abraham Lincoln's assassin, John Wilkes Booth. Corbett was initially arrested for disob ...

fatally shot him in the neck. Paralyzed, he died a few hours later. Of the eight conspirators later convicted, four were soon hanged.

Background and early life

Booth's parents were noted BritishShakespearean

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

actor Junius Brutus Booth

Junius Brutus Booth (1 May 1796 – 30 November 1852) was an English stage actor. He was the father of actor John Wilkes Booth, the assassin of U.S. President Abraham Lincoln. His other children included Edwin Booth, the foremost tragedian of ...

and his mistress, Mary Ann Holmes, who moved to the United States from England in June 1821. They purchased a farm near Bel Air, Maryland

The town of Bel Air is the county seat of Harford County, Maryland. According to the 2020 United States census, the population of the town was 10,661.

History

Bel Air's identity has gone through several incarnations since 1780. Aquilla Scott, w ...

, where John Wilkes Booth was born in a four-room log house on May 10, 1838, the ninth of ten children. He was named after English radical politician John Wilkes

John Wilkes (17 October 1725 – 26 December 1797) was an English radical journalist and politician, as well as a magistrate, essayist and soldier. He was first elected a Member of Parliament in 1757. In the Middlesex election dispute, he f ...

, a distant relative. Junius' wife Adelaide Delannoy Booth was granted a divorce in 1851 on grounds of adultery, and Holmes legally wed Junius on May 10, 1851, John Wilkes' 13th birthday. Nora Titone suggests in her book ''My Thoughts Be Bloody'' (2010) that the shame and ambition of Junius Brutus Booth's actor sons Edwin

The name Edwin means "rich friend". It comes from the Old English elements "ead" (rich, blessed) and "ƿine" (friend). The original Anglo-Saxon form is Eadƿine, which is also found for Anglo-Saxon figures.

People

* Edwin of Northumbria (die ...

and John Wilkes eventually spurred them to strive for achievement and acclaim as rivals—Edwin as a Unionist and John Wilkes as the assassin of Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation thro ...

.

Booth's father built Tudor Hall on the Harford County property as the family's summer home in 1851, while also maintaining a winter residence on Exeter Street in Baltimore. The Booth family was listed as living in Baltimore in the 1850 census.

As a boy, Booth was athletic and popular, and he became skilled at horsemanship and fencing. He attended the Bel Air Academy and was an indifferent student whom the headmaster described as "not deficient in intelligence, but disinclined to take advantage of the educational opportunities offered him. Each day he rode back and forth from farm to school, taking more interest in what happened along the way than in reaching his classes on time". In 1850–1851, he attended the

As a boy, Booth was athletic and popular, and he became skilled at horsemanship and fencing. He attended the Bel Air Academy and was an indifferent student whom the headmaster described as "not deficient in intelligence, but disinclined to take advantage of the educational opportunities offered him. Each day he rode back and forth from farm to school, taking more interest in what happened along the way than in reaching his classes on time". In 1850–1851, he attended the Quaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

-run Milton Boarding School for Boys located in Sparks, Maryland

Sparks is an unincorporated community that is located in Baltimore County, Maryland, United States. It is situated approximately north of Baltimore and is considered to be a suburb of the City of Baltimore. The Gunpowder River runs through Spark ...

, and later St. Timothy's Hall, an Episcopal military academy in Catonsville, Maryland. At the Milton school, students recited classical works by such authors as Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

, Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

, and Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

. Students at St. Timothy's wore military uniforms and were subject to a regimen of daily formation drills and strict discipline. Booth left school at 14 after his father's death.

While attending the Milton Boarding School, Booth met a Romani

Romani may refer to:

Ethnicities

* Romani people, an ethnic group of Northern Indian origin, living dispersed in Europe, the Americas and Asia

** Romani genocide, under Nazi rule

* Romani language, any of several Indo-Aryan languages of the Roma ...

fortune-teller

Fortune telling is the practice of predicting information about a person's life. Melton, J. Gordon. (2008). ''The Encyclopedia of Religious Phenomena''. Visible Ink Press. pp. 115-116. The scope of fortune telling is in principle identical wi ...

who read his palm and pronounced a grim destiny, telling him that he would have a grand but short life, doomed to die young and "meeting a bad end".Clarke, pp. 43–45. His sister recalled that he wrote down the palm-reader's prediction, showed it to his family and others, and often discussed its portents in moments of melancholy.Goodrich, p. 211.

By age 16, Booth was interested in the theater and in politics, and he became a delegate from Bel Air to a rally by the Know Nothing Party for Henry Winter Davis, the anti-immigrant party's candidate for Congress in the 1854 elections. Booth aspired to follow in the footsteps of his father and his actor brothers Edwin

The name Edwin means "rich friend". It comes from the Old English elements "ead" (rich, blessed) and "ƿine" (friend). The original Anglo-Saxon form is Eadƿine, which is also found for Anglo-Saxon figures.

People

* Edwin of Northumbria (die ...

and Junius Brutus Jr. He began practicing elocution daily in the woods around Tudor Hall and studying Shakespeare.

Theatrical career

1850s

Booth made his stage debut at age 17 on August 14, 1855, in the supporting role of the Earl of Richmond in '' Richard III'' at Baltimore's Charles Street Theatre.Smith, pp. 61–62. The audience jeered at him when he missed some of his lines. He also began acting at Baltimore's

Booth made his stage debut at age 17 on August 14, 1855, in the supporting role of the Earl of Richmond in '' Richard III'' at Baltimore's Charles Street Theatre.Smith, pp. 61–62. The audience jeered at him when he missed some of his lines. He also began acting at Baltimore's Holliday Street Theater

The Holliday Street Theater also known as the New Theatre, New Holliday, Old Holliday, The Baltimore Theatre, and Old Drury, was a historical theatrical venue in Federal Period Baltimore, Maryland. It is known for showing the first performance of ...

, owned by John T. Ford

John Thompson Ford (April 16, 1829 – March 14, 1894) was an American Theatre director, theater manager and politician during the nineteenth century. He is most notable for operating Ford's Theatre at the time of the Abraham Lincoln assassinatio ...

, where the Booths had performed frequently. In 1857 he joined the stock company of the Arch Street Theatre

The Arch Street Theatre in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, during the 19th century, was one of the three main Philadelphia theaters for plays; the other two were the Walnut Street Theatre and the Chestnut Street Theatre. The Arch Street Theatre opene ...

in Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, where he played for a full season. At his request, he was billed as "J.B. Wilkes", a pseudonym meant to avoid comparison with other members of his famous thespian family. Jim Bishop

James Alonzo Bishop (November 21, 1907 – July 26, 1987) was an American journalist and author who wrote the bestselling book ''The Day Lincoln was Shot''.

Early life

Born in Jersey City, New Jersey, he dropped out of school after eighth gra ...

wrote that Booth "developed into an outrageous scene stealer

A breakout character is a character in serial fiction, especially a member of an ensemble cast, who becomes much more prominent, popular, discussed, or imitated than expected by the creators. A breakout character may equal or overtake the oth ...

, but he played his parts with such heightened enthusiasm that the audiences idolized him." In February 1858, he played in ''Lucrezia Borgia

Lucrezia Borgia (; ca-valencia, Lucrècia Borja, links=no ; 18 April 1480 – 24 June 1519) was a Spanish-Italian noblewoman of the House of Borgia who was the daughter of Pope Alexander VI and Vannozza dei Cattanei. She reigned as the Govern ...

'' at the Arch Street Theatre. On opening night, he experienced stage fright and stumbled over one of his lines. Instead of introducing himself by saying, "Madame, I am Petruchio Pandolfo", he stammered, "Madame, I am Pondolfio Pet—Pedolfio Pat—Pantuchio Ped—dammit! Who am I?", causing the audience to roar with laughter.

Later that year, Booth played the part of Mohegan Indian Chief Uncas

Uncas () was a ''sachem'' of the Mohegans who made the Mohegans the leading regional Indian tribe in lower Connecticut, through his alliance with the New England colonists against other Indian tribes.

Early life and family

Uncas was born n ...

in a play staged in Petersburg, Virginia

Petersburg is an independent city in the Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 census, the population was 33,458. The Bureau of Economic Analysis combines Petersburg (along with the city of Colonial Heights) with Din ...

, and then became a stock company actor at the Richmond Theatre in Virginia, where he became increasingly popular with audiences for his energetic performances.Kimmel, pp. 151–153. On October 5, 1858, he played the part of Horatio

Horatio is an English male given name, an Italianized form of the ancient Roman Latin '' nomen'' (name) '' Horatius'', from the Roman '' gens'' (clan) '' Horatia''. The modern Italian form is ''Orazio'', the modern Spanish form ''Horacio''. It app ...

in ''Hamlet

''The Tragedy of Hamlet, Prince of Denmark'', often shortened to ''Hamlet'' (), is a tragedy written by William Shakespeare sometime between 1599 and 1601. It is Shakespeare's longest play, with 29,551 words. Set in Denmark, the play depicts ...

'', alongside his older brother Edwin in the title role

The title character in a narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piece. The title of ...

. Afterward, Edwin led him to the theater's footlights and said to the audience, "I think he's done well, don't you?" In response, the audience applauded loudly and cried, "Yes! Yes!" In all, Booth performed in 83 plays in 1858. Booth said that, of all Shakespearean characters, his favorite role was Brutus

Marcus Junius Brutus (; ; 85 BC – 23 October 42 BC), often referred to simply as Brutus, was a Roman politician, orator, and the most famous of the assassins of Julius Caesar. After being adopted by a relative, he used the name Quintus Serv ...

, the slayer of a tyrant.Goodrich, pp. 35–36.

Some critics called Booth "the handsomest man in America" and a "natural genius", and noted his having an "astonishing memory"; others were mixed in their estimation of his acting. He stood tall, had jet-black hair, and was lean and athletic. Noted Civil War reporter George Alfred Townsend described him as a "muscular, perfect man" with "curling hair, like a Corinthian capital". Booth's stage performances were often characterized by his contemporaries as acrobatic and intensely physical, with him leaping upon the stage and gesturing with passion. He was an excellent swordsman, although a fellow actor once recalled that Booth occasionally cut himself with his own sword.

Historian Benjamin Platt Thomas wrote that Booth "won celebrity with theater-goers by his romantic personal attraction", and that he was "too impatient for hard study" and his "brilliant talents had failed of full development." Author Gene Smith wrote that Booth's acting may not have been as precise as his brother Edwin's, but his strikingly handsome appearance enthralled women. As the 1850s drew to a close, Booth was becoming wealthy as an actor, earning $20,000 a year (equivalent to about $ more recently).

Some critics called Booth "the handsomest man in America" and a "natural genius", and noted his having an "astonishing memory"; others were mixed in their estimation of his acting. He stood tall, had jet-black hair, and was lean and athletic. Noted Civil War reporter George Alfred Townsend described him as a "muscular, perfect man" with "curling hair, like a Corinthian capital". Booth's stage performances were often characterized by his contemporaries as acrobatic and intensely physical, with him leaping upon the stage and gesturing with passion. He was an excellent swordsman, although a fellow actor once recalled that Booth occasionally cut himself with his own sword.

Historian Benjamin Platt Thomas wrote that Booth "won celebrity with theater-goers by his romantic personal attraction", and that he was "too impatient for hard study" and his "brilliant talents had failed of full development." Author Gene Smith wrote that Booth's acting may not have been as precise as his brother Edwin's, but his strikingly handsome appearance enthralled women. As the 1850s drew to a close, Booth was becoming wealthy as an actor, earning $20,000 a year (equivalent to about $ more recently).

1860s

Booth embarked on his first national tour as aleading actor

A leading actor, leading actress, or simply lead (), plays the role of the protagonist of a film, television show or play. The word ''lead'' may also refer to the largest role in the piece, and ''leading actor'' may refer to a person who typica ...

after finishing the 1859–1860 theatre season in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. He engaged Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

attorney Matthew Canning to serve as his agent. By mid-1860, he was playing in such cities as New York; Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

; Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

; Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

; St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

; Columbus, Georgia

Columbus is a consolidated city-county located on the west-central border of the U.S. state of Georgia. Columbus lies on the Chattahoochee River directly across from Phenix City, Alabama. It is the county seat of Muscogee County, with which it ...

; Montgomery, Alabama

Montgomery is the capital city of the U.S. state of Alabama and the county seat of Montgomery County. Named for the Irish soldier Richard Montgomery, it stands beside the Alabama River, on the coastal Plain of the Gulf of Mexico. In the 202 ...

; and New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

. Poet and journalist Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Walt Whitman

Walter Whitman (; May 31, 1819 – March 26, 1892) was an American poet, essayist and journalist. A humanist, he was a part of the transition between transcendentalism and realism, incorporating both views in his works. Whitman is among ...

said of Booth's acting, "He would have flashes, passages, I thought of real genius."Smith, p. 80. The ''Philadelphia Press'' drama critic said, "Without having is brother

In linguistics, a copula (plural: copulas or copulae; abbreviated ) is a word or phrase that links the subject of a sentence to a subject complement, such as the word ''is'' in the sentence "The sky is blue" or the phrase ''was not being'' i ...

Edwin's culture and grace, Mr. Booth has far more action, more life, and, we are inclined to think, more natural genius." In October 1860, while performing in Columbus, Georgia

Columbus is a consolidated city-county located on the west-central border of the U.S. state of Georgia. Columbus lies on the Chattahoochee River directly across from Phenix City, Alabama. It is the county seat of Muscogee County, with which it ...

, Booth was shot accidentally in his hotel, leaving a wound some thought would end his life.

When the Civil War began on April 12, 1861, Booth was starring in

When the Civil War began on April 12, 1861, Booth was starring in Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York City ...

. He was outspoken in his admiration for the South's secession, publicly calling it "heroic." This so enraged local citizens that they demanded that he be banned from the stage for making "treason

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

able statements". Albany's drama critics were kinder, giving him rave reviews. One called him a genius, praising his acting for "never fail ngto delight with his masterly impressions." As the Civil War raged across the divided land in 1862, Booth appeared mostly in Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

and border states. In January, he played the title role

The title character in a narrative work is one who is named or referred to in the title of the work. In a performed work such as a play or film, the performer who plays the title character is said to have the title role of the piece. The title of ...

in '' Richard III'' in St. Louis and then made his Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

debut. In March, he made his first acting appearance in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. In May 1862, he made his Boston debut, playing nightly at the Boston Museum in ''Richard III'' (May 12, 15 and 23), ''Romeo and Juliet'' (May 13), ''The Robbers'' (May 14 and 21), ''Hamlet'' (May 16), ''The Apostate'' (May 19), ''The Stranger'' (May 20), and ''The Lady of Lyons'' (May 22). Following his performance of ''Richard III'' on May 12, the Boston ''Transcript''Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

's Academy of Music, as the Battle of Gettysburg

The Battle of Gettysburg () was fought July 1–3, 1863, in and around the town of Gettysburg, Pennsylvania, by Union and Confederate forces during the American Civil War. In the battle, Union Major General George Meade's Army of the Po ...

raged in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

. Between September and November 1863, Booth played a hectic schedule in the northeastern United States

The Northeastern United States, also referred to as the Northeast, the East Coast, or the American Northeast, is a geographic region of the United States. It is located on the Atlantic coast of North America, with Canada to its north, the Southe ...

, appearing in Boston, Providence, Rhode Island

Providence is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Rhode Island. One of the oldest cities in New England, it was founded in 1636 by Roger Williams, a Reformed Baptist theologian and religious exile from the Massachusetts Bay ...

, and Hartford, Connecticut

Hartford is the capital city of the U.S. state of Connecticut. It was the seat of Hartford County until Connecticut disbanded county government in 1960. It is the core city in the Greater Hartford metropolitan area. Census estimates since the ...

. Every day he received fan mail from infatuated women.

Family friend John T. Ford opened 1,500-seat Ford's Theatre

Ford's Theatre is a theater located in Washington, D.C., which opened in August 1863. The theater is infamous for being the site of the assassination of Abraham Lincoln. On the night of April 14, 1865, John Wilkes Booth entered the theater bo ...

on November 9 in Washington, D.C. Booth was one of the first leading men to appear there, playing in Charles Selby's ''The Marble Heart''. In this play, Booth portrayed a Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

sculptor in costume, making marble statues come to life. Lincoln watched the play from his box. At one point during the performance, Booth was said to have shaken his finger in Lincoln's direction as he delivered a line of dialogue. Lincoln's sister-in-law was sitting with him in the same presidential box where he was later slain; she turned to him and said, "Mr. Lincoln, he looks as if he meant that for you." The President replied, "He does look pretty sharp at me, doesn't he?" On another occasion, Lincoln's son Tad saw Booth perform. He said that the actor thrilled him, prompting Booth to give Tad a rose. Booth ignored an invitation to visit Lincoln between acts.

On November 25, 1864, Booth performed for the only time with his brothers

On November 25, 1864, Booth performed for the only time with his brothers Edwin

The name Edwin means "rich friend". It comes from the Old English elements "ead" (rich, blessed) and "ƿine" (friend). The original Anglo-Saxon form is Eadƿine, which is also found for Anglo-Saxon figures.

People

* Edwin of Northumbria (die ...

and Junius in a single engagement production of ''Julius Caesar

Gaius Julius Caesar (; ; 12 July 100 BC – 15 March 44 BC), was a Roman general and statesman. A member of the First Triumvirate, Caesar led the Roman armies in the Gallic Wars before defeating his political rival Pompey in a civil war, and ...

'' at the Winter Garden Theatre

The Winter Garden Theatre is a Broadway theatre at 1634 Broadway in the Midtown Manhattan neighborhood of New York City. It opened in 1911 under designs by architect William Albert Swasey. The Winter Garden's current design dates to 1922, when ...

in New York.Smith, p. 105. He played Mark Antony

Marcus Antonius (14 January 1 August 30 BC), commonly known in English as Mark Antony, was a Roman politician and general who played a critical role in the transformation of the Roman Republic from a constitutional republic into the autoc ...

and his brother Edwin had the larger role of Brutus in a performance acclaimed as "the greatest theatrical event in New York history."Kunhardt, Jr., ''A New Birth of Freedom,'' pp. 342–343 The proceeds went towards a statue of William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

for Central Park

Central Park is an urban park in New York City located between the Upper West Side, Upper West and Upper East Sides of Manhattan. It is the List of New York City parks, fifth-largest park in the city, covering . It is the most visited urban par ...

, which still stands today (2019). In January 1865, he acted in Shakespeare's ''Romeo and Juliet

''Romeo and Juliet'' is a Shakespearean tragedy, tragedy written by William Shakespeare early in his career about the romance between two Italian youths from feuding families. It was among Shakespeare's most popular plays during his lifetim ...

'' in Washington, again garnering rave reviews. The ''National Intelligencer

The ''National Intelligencer and Washington Advertiser'' was a newspaper published in Washington, D.C., from October 30, 1800 until 1870. It was the first newspaper published in the District, which was founded in 1790. It was originally a Tri- ...

'' called Booth's Romeo

Romeo Montague () is the male protagonist of William Shakespeare's tragedy ''Romeo and Juliet''. The son of Lord Montague and his wife, Lady Montague, he secretly loves and marries Juliet, a member of the rival House of Capulet, through a priest ...

"the most satisfactory of all renderings of that fine character," especially praising the death scene. Booth made the final appearance of his acting career at Ford's on March 18, 1865, when he again played Duke Pescara in ''The Apostate.''Clarke, p. 87.

Business ventures

Booth invested some of his growing wealth in various enterprises during the early 1860s, including land speculation in Boston's Back Bay section. He also started a business partnership with John A. Ellsler, manager of the Cleveland Academy of Music, and with Thomas Mears to develop oil wells in northwestern Pennsylvania, where an oil boom had started in August 1859, followingEdwin Drake

Edwin Laurentine Drake (March 29, 1819 – November 9, 1880), also known as Colonel Drake, was an American businessman and the first American to successfully drill for oil.

Early life

Edwin Drake was born in Greenville, New York on March 2 ...

's discovery of oil there, initially calling their venture Dramatic Oil but later renaming it Fuller Farm Oil. The partners invested in a site along the Allegheny River

The Allegheny River ( ) is a long headwater stream of the Ohio River in western Pennsylvania and New York (state), New York. The Allegheny River runs from its headwaters just below the middle of Pennsylvania's northern border northwesterly into ...

at Franklin, Pennsylvania

Franklin is a city and the county seat of Venango County, Pennsylvania. The population was 6,097 in the 2020 census. Franklin is part of the Oil City, PA Micropolitan Statistical Area.

Franklin is known for its three-day autumn festival in Oc ...

in late 1863 for drilling. By early 1864, they had a producing deep oil well named Wilhelmina for Mears' wife, yielding 25 barrels (4 kL) of crude oil daily, then considered a good yield. The Fuller Farm Oil company was selling shares with a prospectus featuring the well-known actor's celebrity status as "Mr. J. Wilkes Booth, a successful and intelligent operator in oil lands". The partners were impatient to increase the well's output and attempted the use of explosives, which wrecked the well and ended production.

Booth was already growing more obsessed with the South's worsening situation in the Civil War and angered at Lincoln's re-election. He withdrew from the oil business on November 27, 1864, with a substantial loss of his $6,000 investment ($81,400 in 2010 dollars).

Civil War years

Booth was strongly opposed to theabolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

who sought to end slavery in the United States. He attended the hanging

Hanging is the suspension of a person by a noose or ligature around the neck.Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed. Hanging as method of execution is unknown, as method of suicide from 1325. The ''Oxford English Dictionary'' states that hanging i ...

of abolitionist leader John Brown on December 2, 1859, who was executed for treason, murder, and inciting a slave insurrection, charges resulting from his raid

Raid, RAID or Raids may refer to:

Attack

* Raid (military), a sudden attack behind the enemy's lines without the intention of holding ground

* Corporate raid, a type of hostile takeover in business

* Panty raid, a prankish raid by male college ...

on the Federal armory

Armory or armoury may mean:

* An arsenal, a military or civilian location for the storage of arms and ammunition

Places

*National Guard Armory, in the United States and Canada, a training place for National Guard or other part-time or regular mili ...

at Harpers Ferry, Virginia

Harpers Ferry is a historic town in Jefferson County, West Virginia, Jefferson County, West Virginia. It is located in the lower Shenandoah Valley. The population was 285 at the 2020 United States census, 2020 census. Situated at the confluence o ...

(since 1863, West Virginia

West Virginia is a state in the Appalachian, Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States.The Census Bureau and the Association of American Geographers classify West Virginia as part of the Southern United States while the B ...

). Booth had been rehearsing at the Richmond Theatre when he read in a newspaper about Brown's upcoming execution. So as to gain access that the public would not have, he donned a borrowed uniform of the Richmond Grays, a volunteer militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

of 1,500 men traveling to Charles Town for Brown's hanging, to guard against a possible attempt to rescue Brown from the gallows by force. When Brown was hanged without incident, Booth stood near the scaffold and afterwards expressed great satisfaction with Brown's fate, although he admired the condemned man's bravery in facing death stoically.

Lincoln was elected president on November 6, 1860, and the following month Booth drafted a long speech, apparently never delivered, that decried Northern abolitionism and made clear his strong support of the South and the institution of slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

. On April 12, 1861, the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

began, and eventually 11 Southern states seceded

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics lea ...

from the Union. In Booth's native Maryland, some of the slaveholding portion of the population favored joining the Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

. Although the Maryland legislature voted decisively (53–13) against secession on April 28, 1861,Mitchell, p.87 it also voted not to allow federal troops to pass south through the state by rail, and it requested that Lincoln remove the growing numbers of federal troops in Maryland. The legislature seems to have wanted to remain in the Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

while also wanting to avoid involvement in a war against Southern neighbors. Adhering to Maryland's demand that its infrastructure not be used to wage war on seceding neighbors would have left the federal capital of Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

, exposed, and would have made the prosecution of war against the South impossible, which was no doubt the legislature's intention. Lincoln suspended the writ of ''habeas corpus

''Habeas corpus'' (; from Medieval Latin, ) is a recourse in law through which a person can report an unlawful detention or imprisonment to a court and request that the court order the custodian of the person, usually a prison official, t ...

'' and imposed martial law

Martial law is the imposition of direct military control of normal civil functions or suspension of civil law by a government, especially in response to an emergency where civil forces are overwhelmed, or in an occupied territory.

Use

Marti ...

in Baltimore and other portions of the state, ordering the imprisonment of many Maryland political leaders at Fort McHenry

Fort McHenry is a historical American coastal pentagonal bastion fort on Locust Point, now a neighborhood of Baltimore, Maryland. It is best known for its role in the War of 1812, when it successfully defended Baltimore Harbor from an attack b ...

and the stationing of Federal troops in Baltimore. Many Marylanders, including Booth, agreed with the ruling of Marylander and U.S. Supreme Court Chief Justice Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

, in ''Ex parte Merryman

''Ex parte Merryman'', 17 F. Cas. 144 (C.C.D. Md. 1861) (No. 9487), is a well-known and controversial U.S. federal court case that arose out of the American Civil War. It was a test of the authority of the President to suspend "t ...

'', that Lincoln's suspension of ''habeas corpus'' in Maryland was unconstitutional

Constitutionality is said to be the condition of acting in accordance with an applicable constitution; "Webster On Line" the status of a law, a procedure, or an act's accordance with the laws or set forth in the applicable constitution. When l ...

.

As a popular actor in the 1860s, Booth continued to travel extensively to perform in the North and South, and as far west as New Orleans. According to his sister Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

, Booth confided to her that he also used his position to smuggle the anti-malarial drug quinine

Quinine is a medication used to treat malaria and babesiosis. This includes the treatment of malaria due to '' Plasmodium falciparum'' that is resistant to chloroquine when artesunate is not available. While sometimes used for nocturnal le ...

, which was crucial to the lives of residents of the Gulf coast, to the South during his travels there, since it was in short supply due to the Northern blockade.Clarke, pp. 81–84.

Booth was pro-Confederate, but his family was divided, like many Marylanders. He was outspoken in his love of the South, and equally outspoken in his hatred of Lincoln. As the Civil War went on, Booth increasingly quarreled with his brother Edwin, who declined to make stage appearances in the South and refused to listen to John Wilkes' fiercely partisan denunciations of the North and Lincoln. In early 1863, Booth was arrested in

Booth was pro-Confederate, but his family was divided, like many Marylanders. He was outspoken in his love of the South, and equally outspoken in his hatred of Lincoln. As the Civil War went on, Booth increasingly quarreled with his brother Edwin, who declined to make stage appearances in the South and refused to listen to John Wilkes' fiercely partisan denunciations of the North and Lincoln. In early 1863, Booth was arrested in St. Louis

St. Louis () is the second-largest city in Missouri, United States. It sits near the confluence of the Mississippi and the Missouri Rivers. In 2020, the city proper had a population of 301,578, while the bi-state metropolitan area, which e ...

while on a theatre tour, when he was heard saying that he "wished the President and the whole damned government would go to hell." He was charged with making "treasonous" remarks against the government, but was released when he took an oath of allegiance to the Union and paid a substantial fine.

Booth is alleged to have been a member of the Knights of the Golden Circle

The Knights of the Golden Circle (KGC) was a secret society founded in 1854 by American George W. L. Bickley, the objective of which was to create a new country, known as the Golden Circle ( es, Círculo Dorado), where slavery would be legal. T ...

, a secret society whose initial objective was to acquire territories as slave states.

In February 1865, Booth became infatuated with Lucy Lambert Hale

Lucy Lambert Hale (January 1, 1841 – October 15, 1915) was the daughter of U.S. Senator John Parker Hale of New Hampshire, and was a noted Washington, D.C., society ''belle''. She attracted many admirers including Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Ro ...

, the daughter of U.S. Senator John P. Hale of New Hampshire

New Hampshire is a U.S. state, state in the New England region of the northeastern United States. It is bordered by Massachusetts to the south, Vermont to the west, Maine and the Gulf of Maine to the east, and the Canadian province of Quebec t ...

, and they became secretly engaged when Booth received his mother's blessing for their marriage plans. "You have so often been dead in love," his mother counseled Booth in a letter, "be well assured she is really and truly devoted to you." Booth composed a handwritten Valentine card for his fiancée on February 13, expressing his "adoration". She was unaware of Booth's deep antipathy towards Lincoln.

Plot to kidnap Lincoln

As the 1864 presidential election drew near, the Confederacy's prospects for victory were ebbing, and the tide of war increasingly favored the North. The likelihood of Lincoln's re-election filled Booth with rage towards the President, whom Booth blamed for the war and all of the South's troubles. Booth had promised his mother at the outbreak of war that he would not enlist as a soldier, but he increasingly chafed at not fighting for the South, writing in a letter to her, "I have begun to deem myself a coward and to despise my own existence." He began to formulate plans to kidnap Lincoln from his summer residence at theOld Soldiers Home

An old soldiers' home is a military veterans' retirement home, nursing home, or hospital, or sometimes an institution for the care of the widows and orphans of a nation's soldiers, sailors, and marines, etc.

United Kingdom

In the United King ...

, from the White House, and to smuggle him across the Potomac River

The Potomac River () drains the Mid-Atlantic United States, flowing from the Potomac Highlands into Chesapeake Bay. It is long,U.S. Geological Survey. National Hydrography Dataset high-resolution flowline dataThe National Map. Retrieved Augus ...

and into Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. Once in Confederate hands, Lincoln would be exchanged for Confederate Army prisoners of war held in Northern prisons and, Booth reasoned, bring the war to an end by emboldening opposition to the war in the North or forcing Union recognition of the Confederate government.

Throughout the Civil War, the Confederacy maintained a network of underground operators in southern Maryland, particularly Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English language, English and French language, French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic, Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*k ...

and St. Mary's Counties, smuggling recruits across the Potomac River into Virginia and relaying messages for Confederate agents as far north as Canada. Booth recruited his friends Samuel Arnold and Michael O'Laughlen

Michael O'Laughlen, Jr. (pronounced ''Oh-Lock-Lun''; June 3, 1840 – September 23, 1867) was an American Confederate soldier and conspirator in John Wilkes Booth's plot to kidnap U.S. President Abraham Lincoln, and later in the latter's assassi ...

as accomplices.Bishop, p. 72. They met often at the house of Confederate sympathizer Maggie Branson at 16 North Eutaw Street in Baltimore. He also met with several well-known Confederate sympathizers at The Parker House in Boston.

In October, Booth made an unexplained trip to

In October, Booth made an unexplained trip to Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

, which was a center of clandestine Confederate activity. He spent ten days in the city, staying for a time at St. Lawrence Hall, a rendezvous for the Confederate Secret Service

The Confederate Secret Service refers to any of a number of official and semi-official secret service organizations and operations conducted by the Confederate States of America during the American Civil War. Some of the organizations were under ...

, and meeting several Confederate agents there. No conclusive proof has linked Booth's kidnapping or assassination plots to a conspiracy involving the leadership of the Confederate government, but historian David Herbert Donald

David Herbert Donald (October 1, 1920 – May 17, 2009) was an American historian, best known for his 1995 biography of Abraham Lincoln. He twice won the Pulitzer Prize for Biography for earlier works; he published more than 30 books on United S ...

states that "at least at the lower levels of the Southern secret service, the abduction of the Union President was under consideration." Historian Thomas Goodrich concludes that Booth entered the Confederate Secret Service as a spy and courier.

Lincoln won a landslide re-election in early November 1864, on a platform that advocated abolishing slavery altogether, by Constitutional amendment. Booth, meanwhile, devoted increased energy and money to his kidnapping plot.Kauffman, ''American Brutus'', pp. 143–144. He assembled a loose-knit band of Confederate sympathizers, including David Herold

David Edgar Herold (June 16, 1842 – July 7, 1865) was an American pharmacist's assistant and accomplice of John Wilkes Booth in the assassination of Abraham Lincoln on April 14, 1865. After the shooting, Herold accompanied Booth to the home of ...

, George Atzerodt