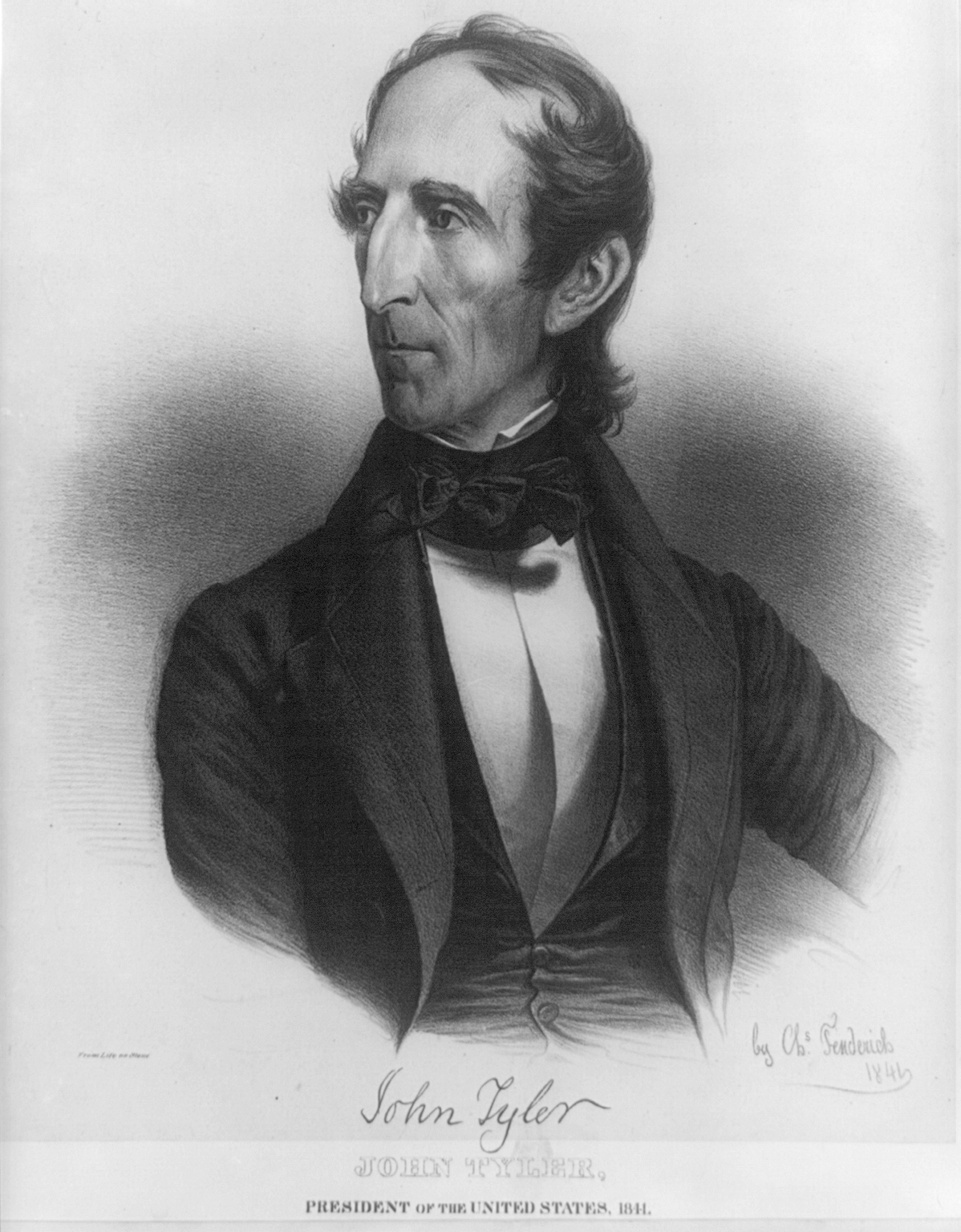

John Tyler (March 29, 1790 – January 18, 1862) was the tenth

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, serving from 1841 to 1845, after briefly holding office as the tenth

vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on t ...

in 1841. He was elected vice president on the

1840

Events

January–March

* January 3 – One of the predecessor papers of the ''Herald Sun'' of Melbourne, Australia, ''The Port Phillip Herald'', is founded.

* January 10 – Uniform Penny Post is introduced in the United Kingdom.

* Janua ...

Whig ticket with President

William Henry Harrison

William Henry Harrison (February 9, 1773April 4, 1841) was an American military officer and politician who served as the ninth president of the United States. Harrison died just 31 days after his inauguration in 1841, and had the shortest pres ...

, succeeding to the presidency following Harrison's death 31 days after assuming office. Tyler was a stalwart supporter and advocate of

states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

, including regarding

slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, and he adopted nationalistic policies as president only when they did not infringe on the states' powers. His unexpected rise to the presidency posed a threat to the presidential ambitions of

Henry Clay

Henry Clay Sr. (April 12, 1777June 29, 1852) was an American attorney and statesman who represented Kentucky in both the U.S. Senate and House of Representatives. He was the seventh House speaker as well as the ninth secretary of state, al ...

and other Whig politicians and left Tyler estranged from both of the nation's major political parties at the time.

Tyler was born into a prominent slaveholding Virginia family. He became a national figure at a time of political upheaval. In the 1820s, the

nation's only political party was the

Democratic-Republican Party

The Democratic-Republican Party, known at the time as the Republican Party and also referred to as the Jeffersonian Republican Party among other names, was an American political party founded by Thomas Jefferson and James Madison in the early ...

, and it split into factions. Initially a

Democrat

Democrat, Democrats, or Democratic may refer to:

Politics

*A proponent of democracy, or democratic government; a form of government involving rule by the people.

*A member of a Democratic Party:

**Democratic Party (United States) (D)

**Democratic ...

, Tyler opposed President

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

during the

Nullification Crisis as he saw Jackson's actions as infringing on states' rights and criticized Jackson's expansion of executive power during the

Bank War

The Bank War was a political struggle that developed over the issue of rechartering the Second Bank of the United States (B.U.S.) during the Presidency of Andrew Jackson, presidency of Andrew Jackson (1829–1837). The affair resulted in the shu ...

. This led Tyler to ally with the

Whig Party. He served as a Virginia state legislator and governor, U.S.

representative

Representative may refer to:

Politics

* Representative democracy, type of democracy in which elected officials represent a group of people

* House of Representatives, legislative body in various countries or sub-national entities

* Legislator, som ...

, and U.S.

senator

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

. Tyler was a regional Whig vice-presidential nominee in the

1836 presidential election; they lost. He was the sole nominee on the

1840

Events

January–March

* January 3 – One of the predecessor papers of the ''Herald Sun'' of Melbourne, Australia, ''The Port Phillip Herald'', is founded.

* January 10 – Uniform Penny Post is introduced in the United Kingdom.

* Janua ...

Whig presidential ticket as William Henry Harrison's running mate. Under the campaign slogan "

Tippecanoe and Tyler Too

"Tippecanoe and Tyler Too", originally published as "Tip and Ty", was a popular and influential campaign song of the Whig Party's colorful Log Cabin Campaign in the 1840 United States presidential election. Its lyrics sang the praises of Whig ...

", the

Harrison-Tyler ticket defeated incumbent president

Martin Van Buren

Martin Van Buren ( ; nl, Maarten van Buren; ; December 5, 1782 – July 24, 1862) was an American lawyer and statesman who served as the eighth president of the United States from 1837 to 1841. A primary founder of the Democratic Party (Uni ...

.

President Harrison died just one month after taking office, and Tyler became the first vice president to

succeed to the presidency. Amid uncertainty as to whether a vice president succeeded a deceased president, or merely took on his duties, Tyler immediately took the

presidential oath of office, setting a lasting precedent. He signed into law some of the Whig-controlled Congress's bills, but he was a

strict constructionist

In the United States, strict constructionism is a particular legal philosophy of judicial interpretation that limits or restricts such interpretation only to the exact wording of the law (namely the Constitution).

Strict sense of the term

...

and vetoed the party's most important bills to create a national bank and raise tariff rates. He believed that the president, rather than Congress, should set policy, and he sought to bypass the Whig establishment led by Senator Henry Clay. Most of Tyler's cabinet resigned shortly into his term and the Whigs expelled him from the party, dubbing him "His Accidency". Tyler was the first president to have his veto of legislation overridden by Congress. He faced a stalemate on domestic policy, although he had several foreign-policy achievements, including the

Webster–Ashburton Treaty

The Webster–Ashburton Treaty, signed August 9, 1842, was a treaty that resolved several border issues between the United States and the British North American colonies (the region that became Canada). Signed under John Tyler's presidency, it ...

with

Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

and the

Treaty of Wanghia

The Treaty of Wanghia (also known as the Treaty of Wangxia; Treaty of peace, amity, and commerce, between the United States of America and the Chinese Empire; ) was the first of the unequal treaties imposed by the United States on China. As per ...

with

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. Tyler firmly believed in

manifest destiny

Manifest destiny was a cultural belief in the 19th century in the United States, 19th-century United States that American settlers were destined to expand across North America.

There were three basic tenets to the concept:

* The special vir ...

and saw

the annexation of Texas as economically advantageous to the United States, signing a bill to offer Texas statehood just before leaving office and returning to his plantation.

When the

American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states th ...

began in 1861, Tyler at first supported the

Peace Conference

A peace conference is a diplomatic meeting where representatives of certain states, armies, or other warring parties converge to end hostilities and sign a peace treaty.

Significant international peace conferences in the past include the follo ...

. When it failed he sided with the

Confederacy. He presided over the opening of the

Virginia Secession Convention and served as a member of the

Provisional Congress of the Confederate States

The Provisional Congress of the Confederate States, also known as the Provisional Congress of the Confederate States of America, was a congress of Deputy (legislator), deputies and Delegate (American politics), delegates called together from th ...

. Tyler subsequently won election to the

Confederate House of Representatives but died before it assembled. Some scholars have praised Tyler's political resolve, but historians have generally

given his presidency a low ranking. Tyler did make progress in combining the American and British navies to stop oceanic African slave trafficking under the Webster-Ashburton Treaty. That treaty also peacefully settled the border between Maine and Canada. Today, Tyler is seldom remembered in comparison to other presidents and maintains only a limited presence in American cultural memory.

Early life and education

John Tyler was born on March 29, 1790, to a slave-owning Virginia family. Like his future

running mate

A running mate is a person running together with another person on a joint Ticket (election), ticket during an election. The term is most often used in reference to the person in the subordinate position (such as the vice presidential candidate ...

, William Henry Harrison, Tyler hailed from

Charles City County, Virginia

Charles City County is a county located in the U.S. commonwealth of Virginia. The county is situated southeast of Richmond and west of Jamestown. It is bounded on the south by the James River and on the east by the Chickahominy River.

The ...

, and was descended from the

First Families of Virginia

First Families of Virginia (FFV) were those families in Colonial Virginia who were socially prominent and wealthy, but not necessarily the earliest settlers. They descended from English colonists who primarily settled at Jamestown, Williamsburg ...

. The

Tyler family traced its lineage to English immigrants and 17th century colonial

Williamsburg. His father,

John Tyler Sr., commonly known as Judge Tyler, was a friend and college roommate of

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

and served in the

Virginia House of Delegates

The Virginia House of Delegates is one of the two parts of the Virginia General Assembly, the other being the Senate of Virginia. It has 100 members elected for terms of two years; unlike most states, these elections take place during odd-numbe ...

alongside

Benjamin Harrison V

Benjamin Harrison V (April 5, 1726April 24, 1791) was an American planter, merchant, and politician who served as a legislator in colonial Virginia, following his namesakes’ tradition of public service. He was a signer of the Continental Ass ...

, William's father. The elder Tyler served four years as Speaker of the Virginia House of Delegates before becoming a

state court judge and later

governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes th ...

and a judge on the

U.S. District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia

The United States District Court for the Eastern District of Virginia (in case citations, E.D. Va.) is one of two United States district courts serving the Commonwealth of Virginia. It has jurisdiction over the Northern Virginia, Hampton ...

at

Richmond

Richmond most often refers to:

* Richmond, Virginia, the capital of Virginia, United States

* Richmond, London, a part of London

* Richmond, North Yorkshire, a town in England

* Richmond, British Columbia, a city in Canada

* Richmond, California, ...

. His wife, Mary Marot (Armistead), was the daughter of prominent

New Kent County plantation owner and one-term delegate, Robert Booth Armistead. She died of a

stroke

A stroke is a medical condition in which poor blood flow to the brain causes cell death. There are two main types of stroke: ischemic, due to lack of blood flow, and hemorrhagic, due to bleeding. Both cause parts of the brain to stop functionin ...

in 1797 when her son John was seven years old.

With two brothers and five sisters, Tyler was reared on

Greenway Plantation

Greenway Plantation is a wood-frame, -story plantation house in Charles City County, Virginia. Historic Route 5 and the Virginia Capital Trail bikeway, both of which connect Williamsburg and Richmond pass to slightly south of this private home ...

, a estate with a six-room manor house his father had built.

[Formally, only the house was named Greenway.] Enslaved labor tended various crops, including wheat, corn and tobacco. Judge Tyler paid high wages for tutors who challenged his children academically. Tyler was of frail health, thin and prone to

diarrhea

Diarrhea, also spelled diarrhoea, is the condition of having at least three loose, liquid, or watery bowel movements each day. It often lasts for a few days and can result in dehydration due to fluid loss. Signs of dehydration often begin wi ...

throughout life. At age 12, he continued a Tyler family tradition and entered the preparatory branch of the

College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William III a ...

. Tyler graduated from the school's collegiate branch in 1807, at age 17.

Adam Smith

Adam Smith (baptized 1723 – 17 July 1790) was a Scottish economist and philosopher who was a pioneer in the thinking of political economy and key figure during the Scottish Enlightenment. Seen by some as "The Father of Economics"——— ...

's ''

The Wealth of Nations

''An Inquiry into the Nature and Causes of the Wealth of Nations'', generally referred to by its shortened title ''The Wealth of Nations'', is the ''magnum opus'' of the Scottish economist and moral philosopher Adam Smith. First published in 1 ...

'' helped form his economic views, and he acquired a lifelong love of

William Shakespeare

William Shakespeare ( 26 April 1564 – 23 April 1616) was an English playwright, poet and actor. He is widely regarded as the greatest writer in the English language and the world's pre-eminent dramatist. He is often called England's nation ...

. Bishop

James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

, the college's president, served as a second father and mentor to Tyler.

After graduation, Tyler

read the law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under the ...

with his father, then a state judge, and later with

Edmund Randolph

Edmund Jennings Randolph (August 10, 1753 September 12, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States, attorney, and the 7th Governor of Virginia. As a delegate from Virginia, he attended the Constitutional Convention and helped to create ...

, former

United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

.

Planter and lawyer

Tyler was

admitted to the Virginia bar at the age of 19 (too young to be eligible, but the admitting judge neglected to ask his age). By this time, his father was

governor of Virginia

The governor of the Commonwealth of Virginia serves as the head of government of Virginia for a four-year term. The incumbent, Glenn Youngkin, was sworn in on January 15, 2022.

Oath of office

On inauguration day, the Governor-elect takes th ...

, and the young Tyler started a legal practice in Richmond, the state capital.

Chitwood Chitwood is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Bill Chitwood (1890–1961), American fiddler

* Christina Chitwood (born 1990), American ice dancer

*Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racing driver and businessman

* May Belle Hu ...

, pp. 20–21; Crapol, pp. 35–36. According to the 1810 federal census, one “John Tyler” (presumably his father) owned eight slaves in Richmond, and possibly five slaves in adjoining Henrico County, and possibly 26 slaves in Charles City County.

In 1813, the year of his father's death, the younger Tyler purchased

Woodburn plantation, where he lived until 1821.

As of 1820, Tyler owned 24 enslaved persons at Woodburn, after having inherited 13 enslaved persons from his father, although only eight were listed as engaged in agriculture in that census.

Political rise

Start in Virginia politics

In 1811, at age 21, Tyler was elected to represent Charles City County in the House of Delegates. He served five successive one-year terms (the first alongside Cornelius Egmon and later with Benjamin Harrison). As a state legislator, Tyler sat on the Courts and Justice Committee. His defining positions were on display by the end of his first term in 1811—strong, staunch support of

states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

and opposition to a national bank. He joined fellow legislator

Benjamin W. Leigh

Benjamin Watkins Leigh (June 18, 1781February 2, 1849) was an American lawyer and politician from Richmond, Virginia. He served in the Virginia House of Delegates and represented Virginia in the United States Senate.

Early and family life

Benja ...

in supporting the censure of U.S. senators

William Branch Giles

William Branch Giles (August 12, 1762December 4, 1830; the ''g'' is pronounced like a ''j'') was an American statesman, long-term Senator from Virginia, and the 24th Governor of Virginia. He served in the House of Representatives from 1790 to 1 ...

and

Richard Brent of Virginia who had, against the Virginia legislature's instructions, voted for the recharter of the

First Bank of the United States

First or 1st is the ordinal form of the number one (#1).

First or 1st may also refer to:

*World record, specifically the first instance of a particular achievement

Arts and media Music

* 1$T, American rapper, singer-songwriter, DJ, and rec ...

.

War of 1812

Like most Americans of his day, Tyler was

anti-British

Anti-British sentiment is prejudice, persecution, discrimination, fear or hatred against the Government of the United Kingdom, British Government, British people, or the Culture of the United Kingdom, culture of the United Kingdom.

Argen ...

, and at the onset of the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

he urged support for military action in a speech to the House of Delegates. After the British capture of

Hampton, Virginia

Hampton () is an independent city (United States), independent city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Virginia in the United States. As of the 2020 United States Census, 2020 census, the population was 137,148. It is the List ...

, in the summer of 1813, Tyler eagerly organized a militia company, the Charles City Rifles, to defend Richmond, which he commanded with the rank of

captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

. No attack came, and he dissolved the company two months later. For his military service, Tyler received a land grant near what later became

Sioux City, Iowa

Sioux City () is a city in Woodbury and Plymouth counties in the northwestern part of the U.S. state of Iowa. The population was 85,797 in the 2020 census, making it the fourth-largest city in Iowa. The bulk of the city is in Woodbury County, ...

.

Tyler's father died in 1813, and Tyler inherited 13 slaves along with his father's plantation. In 1816, he resigned his legislative seat to serve on the Governor's

Council of State

A Council of State is a governmental body in a country, or a subdivision of a country, with a function that varies by jurisdiction. It may be the formal name for the cabinet or it may refer to a non-executive advisory body associated with a head o ...

, a group of eight advisers elected by the General Assembly.

Chitwood Chitwood is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Bill Chitwood (1890–1961), American fiddler

* Christina Chitwood (born 1990), American ice dancer

*Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racing driver and businessman

* May Belle Hu ...

, pp. 26–30.

U.S. House of Representatives

The death of U.S. Representative

John Clopton

John Clopton (February 7, 1756 – September 11, 1816) was a United States representative from Virginia.

Early life and education

John Clopton was born in St. Peter's Parish, near Tunstall, New Kent County in the Colony of Virginia on Febru ...

in September 1816 created a vacancy in

Virginia's 23rd congressional district. Tyler sought the seat, as did his friend and political ally

Andrew Stevenson

Andrew Stevenson (January 21, 1784 – January 25, 1857) was an American politician, lawyer and diplomat. He represented Richmond, Virginia in the Virginia House of Delegates and eventually became its speaker before being elected to the United S ...

. Since the two men were politically alike, the race was for the most part a popularity contest. Tyler's political connections and campaigning skills narrowly won him the election. He was sworn into the

Fourteenth Congress

The 14th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in the Old Brick Capitol in Washingto ...

on December 17, 1816, to serve as a Democratic-Republican,

[Contemporaries generally called this the ''Republican Party'', but modern political writers use ''Democratic-Republican'' to distinguish it from the modern-day Republican Party.] the major political party in the

Era of Good Feelings

The Era of Good Feelings marked a period in the political history of the United States that reflected a sense of national purpose and a desire for unity among Americans in the aftermath of the War of 1812. The era saw the collapse of the Fed ...

.

Chitwood Chitwood is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Bill Chitwood (1890–1961), American fiddler

* Christina Chitwood (born 1990), American ice dancer

*Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racing driver and businessman

* May Belle Hu ...

, pp. 31–34.

While the Democratic-Republicans had supported states' rights, in the wake of the War of 1812 many members urged a stronger central government. A majority in Congress wanted to see the federal government help to fund

internal improvements

Internal improvements is the term used historically in the United States for public works from the end of the American Revolution through much of the 19th century, mainly for the creation of a transportation infrastructure: roads, turnpikes, canal ...

such as ports and roadways. Tyler held fast to his

strict constructionist

In the United States, strict constructionism is a particular legal philosophy of judicial interpretation that limits or restricts such interpretation only to the exact wording of the law (namely the Constitution).

Strict sense of the term

...

beliefs, rejecting such proposals on both constitutional and personal grounds. He believed each state should construct necessary projects within its borders using locally generated funds. Virginia was not "in so poor a condition as to require a ''charitable'' donation from Congress", he contended.

He was chosen to participate in an audit of the

Second Bank of the United States

The Second Bank of the United States was the second federally authorized Hamiltonian national bank in the United States. Located in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, the bank was chartered from February 1816 to January 1836.. The Bank's formal name, ac ...

in 1818 as part of a five-man committee, and was appalled by the corruption which he perceived within the bank. He argued for the revocation of the bank charter, although Congress rejected any such proposal. His first clash with General

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

followed

Jackson's 1818 invasion of Florida during the

First Seminole War

The Seminole Wars (also known as the Florida Wars) were three related military conflicts in Florida between the United States and the Seminole, citizens of a Native American nation which formed in the region during the early 1700s. Hostilities ...

. While praising Jackson's character, Tyler condemned him as overzealous for

the execution of two British subjects. Tyler was elected for a full term without opposition in early 1819.

The major issue of the

Sixteenth Congress

The 16th United States Congress was a meeting of the legislative branch of the United States federal government, consisting of the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives. It met in Washington, D.C. from March 4, 1819, ...

(1819–21) was whether

Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

should be admitted to the Union, and whether slavery would be permitted in the new state.

Acknowledging the ills of slavery, he hoped that by letting it expand, there would be fewer slaves in the east as slave and master journeyed west, making it feasible to consider abolishing the institution in Virginia. Thus, slavery would be abolished through the action of individual states as the practice became rare, as had been done in some Northern states.

Tyler believed that Congress did not have the power to regulate slavery and that admitting states based on whether they were slave or free was a recipe for sectional conflict; therefore, the

Missouri Compromise

The Missouri Compromise was a federal legislation of the United States that balanced desires of northern states to prevent expansion of slavery in the country with those of southern states to expand it. It admitted Missouri as a Slave states an ...

was enacted without Tyler's support. It admitted Missouri as a

slave state

In the United States before 1865, a slave state was a state in which slavery and the internal or domestic slave trade were legal, while a free state was one in which they were not. Between 1812 and 1850, it was considered by the slave states ...

and Maine as a free one, and it also forbade slavery in states formed from the northern part of

the territories. Throughout his time in Congress, he voted against bills which would restrict slavery in the territories.

Chitwood Chitwood is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Bill Chitwood (1890–1961), American fiddler

* Christina Chitwood (born 1990), American ice dancer

*Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racing driver and businessman

* May Belle Hu ...

, pp. 47–50; Crapol, pp. 37–38.

Tyler declined to seek renomination in late 1820, citing ill health. He privately acknowledged his dissatisfaction with the position, as his opposing votes were largely symbolic and did little to change the political culture in Washington; he also observed that funding his children's education would be difficult on a congressman's low salary. He left office on March 3, 1821, endorsing his former opponent Stevenson for the seat, and returned to private law practice full-time.

Return to state politics

Restless and bored after two years at home practicing law, Tyler sought election to the House of Delegates in 1823. Neither member from Charles City County was seeking reelection, and Tyler was elected easily that April, finishing first among the three candidates seeking the two seats. As the legislature convened in December, Tyler found the chamber debating the impending

presidential election of 1824. The

congressional nominating caucus The congressional nominating caucus is the name for informal meetings in which American congressmen would agree on whom to nominate for the Presidency and Vice Presidency from their political party.

History

The system was introduced after George W ...

, an early system for choosing presidential candidates, was still used despite its growing unpopularity. Tyler tried to convince the lower house to endorse the caucus system and choose

William H. Crawford

William Harris Crawford (February 24, 1772 – September 15, 1834) was an American politician and judge during the early 19th century. He served as US Secretary of War and US Secretary of the Treasury before he ran for US president in the 1824 ...

as the Democratic-Republican candidate. Crawford captured the legislature's support, but Tyler's proposal was defeated. His most enduring effort in this second legislative tenure was saving the College of William and Mary, which risked closure from waning enrollment. Rather than move it from rural Williamsburg to the more populated capital at Richmond, as some suggested, Tyler proposed administrative and financial reforms. These were passed into law and were successful; by 1840 the school achieved its highest enrollment.

Tyler's political fortunes were growing; he was considered as a possible candidate in the legislative deliberation for the 1824 U.S. Senate election. He was nominated in December 1825 for governor of Virginia, a position which was then appointed by the legislature. Tyler was elected 131–81 over

John Floyd. The office of governor was powerless under the original

Virginia Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Virginia is the document that defines and limits the powers of the state government and the basic rights of the citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Like all other state constitutions, it is supreme ...

(1776–1830), lacking even veto authority. Tyler enjoyed a prominent oratorical platform but could do little to influence the legislature. His most visible act as governor was delivering the funeral address for former president Jefferson, a Virginian and a former governor, who had died on July 4, 1826.

[At the end of the speech, Tyler briefly lauded President ]John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

of Massachusetts, who had died the same day. Tyler was deeply devoted to Jefferson, and his eloquent eulogy was well received.

Tyler's governorship was otherwise uneventful. He promoted states' rights and adamantly opposed any concentration of federal power. In order to thwart federal infrastructure proposals, he suggested Virginia actively expand its own road system. A proposal was made to expand the state's poorly funded public school system, but no significant action was taken. Tyler was unanimously reelected to a second one-year term in December 1826.

In 1829, Tyler was elected as a delegate to the

Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830

The Virginia Constitutional Convention of 1829–1830 was a constitutional convention for the state of Virginia, held in Richmond from October 5, 1829 to January 15, 1830.

Background and composition

Almost immediately, the Constitution of 17 ...

from the district encompassing the cities of Richmond and Williamsburg and Charles City County, James City County, Henrico County, New Kent County, Warwick County, and York County. There, he served alongside Chief Justice

John Marshall

John Marshall (September 24, 1755July 6, 1835) was an American politician and lawyer who served as the fourth Chief Justice of the United States from 1801 until his death in 1835. He remains the longest-serving chief justice and fourth-longes ...

(a Richmond resident), Philip N. Nicholas and John B. Clopton. The leadership assigned him to the Committee on the Legislature. Tyler's service in various capacities at a state level included as president of the Virginia

Colonization Society, and much later as rector and chancellor of the

College of William and Mary

The College of William & Mary (officially The College of William and Mary in Virginia, abbreviated as William & Mary, W&M) is a public research university in Williamsburg, Virginia. Founded in 1693 by letters patent issued by King William III a ...

.

U.S. Senate

In January 1827, the General Assembly considered whether to elect U.S. Senator

John Randolph for a full six-year term. Randolph was a contentious figure; although he shared the staunch states' rights views held by most of the Virginia legislature, he had a reputation for fiery rhetoric and erratic behavior on the Senate floor, which put his allies in an awkward position. Furthermore, he had made enemies by fiercely opposing President

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

and Kentucky Senator Henry Clay. The nationalists of the Democratic-Republican Party, who supported Adams and Clay, were a sizable minority in the Virginia legislature. They hoped to unseat Randolph by capturing the vote of states' rights supporters who were uncomfortable with the senator's reputation. They approached Tyler, and promised their endorsement if he sought the seat. Tyler repeatedly declined the offer, endorsing Randolph as the best candidate, but the political pressure continued to mount. Eventually he agreed to accept the seat if chosen. On the day of the vote, one assemblyman argued there was no political difference between the two candidates—Tyler was merely more agreeable than Randolph. The incumbent's supporters, though, contended that Tyler's election would be a tacit endorsement of the Adams administration. The legislature selected Tyler in a vote of 115–110, and he resigned his governorship on March 4, 1827, as his Senate term began.

Democratic maverick

By the time of Tyler's senatorial election, the

1828 campaign for president was in progress. Adams, the incumbent president, was challenged by Andrew Jackson. The Democratic-Republicans had splintered into Adams's

National Republicans

The National Republican Party, also known as the Anti-Jacksonian Party or simply Republicans, was a political party in the United States that evolved from a conservative-leaning faction of the Democratic-Republican Party that supported John Q ...

and Jackson's

Democrats. Tyler disliked both candidates for their willingness to increase the power of the federal government, but was increasingly drawn to Jackson, hoping that he would not seek to spend as much federal money on internal improvements as Adams. Of Jackson, he wrote, "Turning to him I may at least indulge in hope; looking on Adams I must despair."

When the

Twentieth Congress began in December 1827,

[Tyler's name does not appear in the Senate voting records until late January of the following year, likely due to illness.] Tyler served alongside his Virginia colleague and friend

Littleton Waller Tazewell

Littleton Waller Tazewell (December 17, 1774May 6, 1860) was a Virginia lawyer, plantation owner and politician who served as U.S. Representative, U.S. Senator and the 26th Governor of Virginia, as well as a member of the Virginia House of Dele ...

, who shared his strict constructionist views and uneasy support of Jackson. Throughout his tenure, Tyler vigorously opposed national infrastructure bills, feeling these were matters for individual states to decide. He and his Southern colleagues unsuccessfully opposed the protectionist

Tariff of 1828

The Tariff of 1828 was a very high protective tariff that became law in the United States in May 1828. It was a bill designed to not pass Congress because it was seen by free trade supporters as hurting both industry and farming, but surprising ...

, known to its detractors as the "Tariff of Abominations". Tyler suggested that the tariff's only positive outcome would be a national political backlash, restoring a respect for states' rights. He remained a strong supporter of states' rights, saying, "they may strike the Federal Government out of existence by a word; demolish the Constitution and scatter its fragments to the winds".

[ Kleber, p. 698.]

Tyler was soon at odds with President Jackson, frustrated by Jackson's newly emerging

spoils system

In politics and government, a spoils system (also known as a patronage system) is a practice in which a political party, after winning an election, gives government jobs to its supporters, friends (cronyism), and relatives (nepotism) as a reward ...

, describing it as an "electioneering weapon". He voted against many of Jackson's nominations when they appeared to be unconstitutional or motivated by patronage. Opposing the nominations of a president of his own party was considered "an act of insurgency" against his party. Tyler was particularly offended by Jackson's use of the

recess appointment

In the United States, a recess appointment is an appointment by the president of a federal official when the U.S. Senate is in recess. Under the U.S. Constitution's Appointments Clause, the President is empowered to nominate, and with the advi ...

power to name three treaty commissioners to meet with emissaries from the

Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, and introduced a bill chastising Jackson for this.

In some matters Tyler was on good terms with Jackson. He defended Jackson for

vetoing the Maysville Road funding project, which Jackson considered unconstitutional. He voted to confirm several of Jackson's appointments, including Jackson's future running mate Martin Van Buren as

United States Minister to Britain

The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the ambassador of the United States to the Court of St James's) is the official representative of the president of the United States and the American government to the monarc ...

. The leading issue in the

1832 presidential election was the recharter of the Second Bank of the United States, which both Tyler and Jackson opposed. Congress voted to recharter the bank in July 1832, and Jackson vetoed the bill for both constitutional and practical reasons. Tyler voted to sustain the veto and endorsed Jackson in his successful bid for reelection.

Break with the Democratic Party

Tyler's uneasy relationship with his party came to a head during the

22nd Congress, as the Nullification Crisis of 1832–33 began. South Carolina, threatening

secession

Secession is the withdrawal of a group from a larger entity, especially a political entity, but also from any organization, union or military alliance. Some of the most famous and significant secessions have been: the former Soviet republics le ...

, passed the

Ordinance of Nullification

The Ordinance of Nullification declared the Tariffs of 1828 and 1832 null and void within the borders of the U.S. state of South Carolina, beginning on February 1, 1833. It began the Nullification Crisis. Passed by a state convention on Novembe ...

in November 1832, declaring the "Tariff of Abominations" null and void within its borders. This raised the constitutional question of whether states could nullify federal laws. Jackson, who denied such a right, prepared to sign a

Force Bill

The Force Bill, formally titled "''An Act further to provide for the collection of duties on imports''", (1833), refers to legislation enacted by the 22nd U.S. Congress on March 2, 1833, during the nullification crisis.

Passed by Congress at ...

allowing the federal government to use military action to enforce the tariff. Tyler, who sympathized with South Carolina's reasons for nullification, rejected Jackson's use of military force against a state and gave a speech in February 1833 outlining his views. He supported Clay's

Compromise Tariff

The Tariff of 1833 (also known as the Compromise Tariff of 1833, ch. 55, ), enacted on March 2, 1833, was proposed by Henry Clay and John C. Calhoun as a resolution to the Nullification Crisis. Enacted under Andrew Jackson's presidency, it was ...

, enacted that year, to gradually reduce the tariff over ten years, alleviating tensions between the states and the federal government.

In voting against the Force Bill, Tyler knew he would permanently alienate the pro-Jackson faction of the Virginia legislature, even those who had tolerated his irregularity up to this point. This jeopardized

his reelection in February 1833, in which he faced the pro-administration Democrat

James McDowell

James McDowell (October 13, 1795 – August 24, 1851) was the 29th Governor of Virginia from 1843 to 1846 and was a U.S. Congressman from 1846 to 1851.

Biography

McDowell was born at "Cherry Grove," near Rockbridge County, Virginia, on ...

, but with Clay's endorsement, Tyler was reelected by a margin of 12 votes.

Jackson further offended Tyler by moving to dissolve the Bank by executive fiat. In September 1833, Jackson issued an executive order directing Treasury Secretary

Roger B. Taney

Roger Brooke Taney (; March 17, 1777 – October 12, 1864) was the fifth chief justice of the United States, holding that office from 1836 until his death in 1864. Although an opponent of slavery, believing it to be an evil practice, Taney belie ...

to transfer federal funds from the Bank to state-chartered banks without delay. Tyler saw this as "a flagrant assumption of power", a breach of contract, and a threat to the economy. After months of agonizing, he decided to join with Jackson's opponents. Sitting on the

Senate Finance Committee

The United States Senate Committee on Finance (or, less formally, Senate Finance Committee) is a standing committee of the United States Senate. The Committee concerns itself with matters relating to taxation and other revenue measures generall ...

, he voted for two censure resolutions against the president in March 1834.

Chitwood Chitwood is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Bill Chitwood (1890–1961), American fiddler

* Christina Chitwood (born 1990), American ice dancer

*Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racing driver and businessman

* May Belle Hu ...

, pp. 125–28. By this time, Tyler had become affiliated with Clay's newly formed

Whig Party, which held control of the Senate. On March 3, 1835, with only hours remaining in the

congressional session, the Whigs voted Tyler

President ''pro tempore'' of the Senate as a symbolic gesture of approval. He is the only U.S. president to have held this office.

Shortly thereafter, the Democrats took control of the Virginia House of Delegates. Tyler was offered a judgeship in exchange for resigning his seat, but he declined. He understood what was to come: the legislature would soon force him to cast a vote that went against his constitutional beliefs. Senator

Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri had introduced a bill expunging Jackson's censure. By resolution of the Democratic-controlled legislature, Tyler could be instructed to vote for the bill. If he disregarded the instructions, he would be violating his own principles: "the first act of my political life was a censure on Messrs. Giles and Brent for opposition to instructions", he noted. Over the next few months he sought the counsel of his friends, who gave him conflicting advice. By mid-February he felt that his Senate career was likely at an end. He issued a letter of resignation to Vice President Van Buren on February 29, 1836, saying in part:

Chitwood Chitwood is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Bill Chitwood (1890–1961), American fiddler

* Christina Chitwood (born 1990), American ice dancer

*Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racing driver and businessman

* May Belle Hu ...

, p. 134.

1836 presidential election

While Tyler wished to attend to his private life and family, he was soon occupied with the

1836 presidential election. He had been suggested as a vice presidential candidate since early 1835, and the same day the Virginia Democrats issued the expunging instruction, the Virginia Whigs nominated him as their candidate. The new Whig Party was not organized enough to hold a national convention and name a single ticket against Van Buren, Jackson's chosen successor. Instead, Whigs in various regions put forth their own preferred tickets, reflecting the party's tenuous coalition: the Massachusetts Whigs nominated

Daniel Webster

Daniel Webster (January 18, 1782 – October 24, 1852) was an American lawyer and statesman who represented New Hampshire and Massachusetts in the U.S. Congress and served as the U.S. Secretary of State under Presidents William Henry Harrison, ...

and

Francis Granger

Francis Granger (December 1, 1792 – August 31, 1868) was an American politician who represented Ontario County, New York, in the United States House of Representatives for three non-consecutive terms. He was a leading figure in the state and ...

, the

Anti-Masons of the Northern and border states backed William Henry Harrison and Granger, and the states' rights advocates of the middle and lower South nominated

Hugh Lawson White

Hugh Lawson White (October 30, 1773April 10, 1840) was a prominent American politician during the first third of the 19th century. After filling in several posts particularly in Tennessee's judiciary and state legislature since 1801, thereunder ...

and John Tyler.

In Maryland, the Whig ticket was Harrison and Tyler and in South Carolina it was

Willie P. Mangum

Willie Person Mangum (; May 10, 1792September 7, 1861) was an American politician and planter who served as U.S. Senator from the state of North Carolina between 1831 and 1836 and between 1840 and 1853. He was one of the founders and leading memb ...

and Tyler. The Whigs wanted to deny Van Buren a majority in the Electoral College, throwing the election into the House of Representatives, where deals could be made. Tyler hoped electors would be unable to elect a vice president, and that he would be one of the top two vote-getters, from whom the Senate, under the

Twelfth Amendment, must choose.

Seager Seager is a surname, and may refer to:

* Alexandra Seager (1870–1950), businesswoman and philanthropist in South Australia

* Allan Seager (1906–1968), American novelist and short-story writer

* Charles Allen Seager (1872–1948), Anglican Bisho ...

, pp. 119–21.

Following the custom of the times—that candidates not appear to seek the office—Tyler stayed home throughout the campaign, and made no speeches.

He received only 47 electoral votes, from Georgia, South Carolina and Tennessee, in the November 1836 election, trailing both Granger and the Democratic candidate,

Richard Mentor Johnson

Richard Mentor Johnson (October 17, 1780 – November 19, 1850) was an American lawyer, military officer and politician who served as the ninth vice president of the United States, serving from 1837 to 1841 under President Martin Van Buren ...

of Kentucky. Harrison was the leading Whig candidate for president, but he lost to Van Buren.

Chitwood Chitwood is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Bill Chitwood (1890–1961), American fiddler

* Christina Chitwood (born 1990), American ice dancer

*Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racing driver and businessman

* May Belle Hu ...

, pp. 147–51. The presidential election was settled by the Electoral College, but for the only time in American history, the vice-presidential election was decided by the Senate, which selected Johnson over Granger on the first ballot.

National political figure

Tyler had been drawn into Virginia politics as a U.S. senator. From October 1829 to January 1830, he served as a member of the

state constitutional convention, a role he had been reluctant to accept. The original

Virginia Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Virginia is the document that defines and limits the powers of the state government and the basic rights of the citizens of the Commonwealth of Virginia. Like all other state constitutions, it is supreme ...

gave outsize influence to the state's more conservative eastern counties, as it allocated an equal number of legislators to each county regardless of population and granted suffrage only to property owners. The convention gave the more populous and liberal counties of western Virginia an opportunity to expand their influence. A slaveowner from eastern Virginia, Tyler supported the existing system, but largely remained on the sidelines during the debate, not wishing to alienate any of the state's political factions. He was focused on his Senate career, which required a broad base of support, and gave speeches during the convention promoting compromise and unity.

After the 1836 election, Tyler thought his political career was over, and planned to return to private law practice. In the fall of 1837 a friend sold him a sizable property in Williamsburg. Unable to remain away from politics, Tyler successfully sought election to the House of Delegates and took his seat in 1838. He was a national political figure by this point, and his third delegate service touched on such national issues as the sale of public lands.

Tyler's successor in the Senate was

William Cabell Rives

William Cabell Rives (May 4, 1793April 25, 1868) was an American lawyer, planter, politician and diplomat from Virginia. Initially a Jackson Democrat as well as member of the First Families of Virginia, Rives served in the Virginia House of Delega ...

, a conservative Democrat. In February 1839, the General Assembly considered who should fill that seat, which was to expire the following month. Rives had drifted away from his party, signalling a possible alliance with the Whigs. As Tyler had already fully rejected the Democrats, he expected the Whigs would support him. Still, many Whigs found Rives a more politically expedient choice, as they hoped to ally with the conservative wing of the Democratic Party in the 1840 presidential election. This strategy was supported by Whig leader Henry Clay, who nevertheless admired Tyler at that time. With the vote split among three candidates, including Rives and Tyler, the Senate seat remained vacant for almost two years, until January 1841.

1840 presidential election

Adding Tyler to the ticket

When the

1839 Whig National Convention convened in

Harrisburg, Pennsylvania

Harrisburg is the capital city of the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Dauphin County. With a population of 50,135 as of the 2021 census, Harrisburg is the 9th largest city and 15th largest municipality in Pe ...

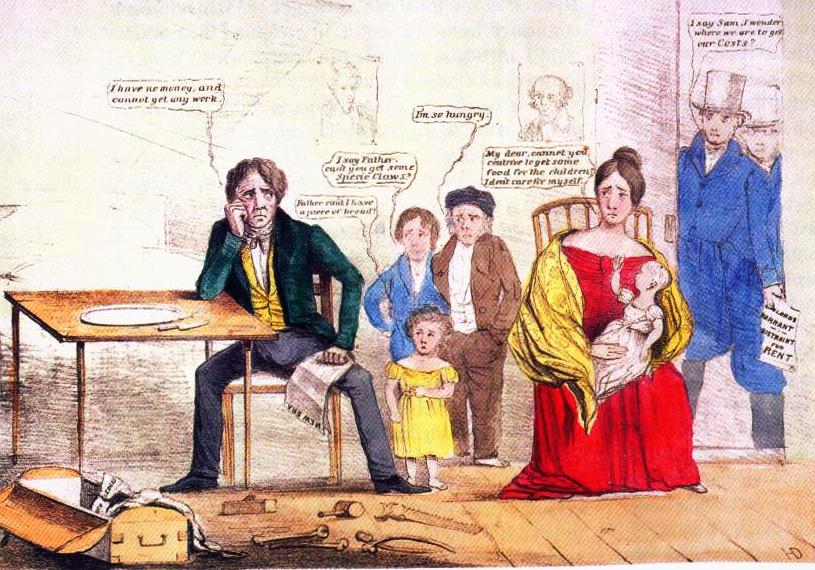

, to choose the party's ticket, the nation was in the third year of a serious recession following the

Panic of 1837

The Panic of 1837 was a financial crisis in the United States that touched off a major depression, which lasted until the mid-1840s. Profits, prices, and wages went down, westward expansion was stalled, unemployment went up, and pessimism abound ...

. Van Buren's ineffective efforts to deal with the situation cost him public support. With the Democratic Party torn into factions, the head of the Whig ticket would likely be the next president. Harrison, Clay, and General

Winfield Scott

Winfield Scott (June 13, 1786May 29, 1866) was an American military commander and political candidate. He served as a general in the United States Army from 1814 to 1861, taking part in the War of 1812, the Mexican–American War, the early s ...

all sought the nomination. Tyler attended the convention and was with the Virginia delegation, although he had no official status. Because of bitterness over the unresolved Senate election, the Virginia delegation refused to make Tyler its

favorite son

Favorite son (or favorite daughter) is a political term.

* At the quadrennial American national political party conventions, a state delegation sometimes nominates a candidate from the state, or less often from the state's region, who is not a ...

candidate for vice president. Tyler himself did nothing to aid his chances. If his favored candidate for the presidential nomination, Clay, was successful, he would likely not be chosen for the second place on the ticket, which would probably go to a Northerner to assure geographic balance.

The convention deadlocked among the three main candidates, with Virginia's votes going to Clay. Many Northern Whigs opposed Clay, and some, including Pennsylvania's

Thaddeus Stevens

Thaddeus Stevens (April 4, 1792August 11, 1868) was a member of the United States House of Representatives from Pennsylvania, one of the leaders of the Radical Republican faction of the Republican Party during the 1860s. A fierce opponent of sla ...

, showed the Virginians a letter by Scott in which he apparently displayed abolitionist sentiments. The influential Virginia delegation then announced that Harrison was its second choice, causing most Scott supporters to abandon him in favor of Harrison, who gained the presidential nomination.

Seager Seager is a surname, and may refer to:

* Alexandra Seager (1870–1950), businesswoman and philanthropist in South Australia

* Allan Seager (1906–1968), American novelist and short-story writer

* Charles Allen Seager (1872–1948), Anglican Bisho ...

, pp. 132–33.

The vice presidential nomination was considered

immaterial

Immaterial may refer to:

* The opposite of matter, material, materialism, or materialistic

* Maya (illusion), a concept in all Indian religions, that all matter is a grand illusion

* Incorporeality

* Immaterialism, including subjective idealism ...

; no president had failed to complete his elected term. Not much attention was given to the choice, and the specifics of how Tyler came to gain it are unclear. Chitwood pointed out that Tyler was a logical candidate: as a Southern slaveowner, he balanced the ticket and also assuaged the fears of Southerners who felt Harrison might have abolitionist leanings. Tyler had been a vice-presidential candidate in 1836, and having him on the ticket might win Virginia, the most populous state in the South. One of the convention managers, New York publisher

Thurlow Weed

Edward Thurlow Weed (November 15, 1797 – November 22, 1882) was a printer, New York newspaper publisher, and Whig and Republican politician. He was the principal political advisor to prominent New York politician William H. Seward and was ins ...

, alleged that "Tyler was finally taken because we could get nobody else to accept"—though he did not say this until after the subsequent break between President Tyler and the Whig Party. Other Tyler foes claimed that he had wept himself into the White House, after crying at Clay's defeat; this was unlikely, as the Kentuckian had backed Tyler's opponent Rives in the Senate election. Tyler's name was submitted in the balloting, and though Virginia abstained, he received the necessary majority. As president, Tyler was accused of having gained the nomination by concealing his views, and responded that he had not been asked about them. His biographer Robert Seager II held that Tyler was selected because of a dearth of alternative candidates. Seager concluded, "He was put on the ticket to draw the South to Harrison. No more, no less."

General election

There was no Whig

platform

Platform may refer to:

Technology

* Computing platform, a framework on which applications may be run

* Platform game, a genre of video games

* Car platform, a set of components shared by several vehicle models

* Weapons platform, a system or ...

—the party leaders decided that trying to put one together would tear the party apart. So the Whigs ran on their opposition to Van Buren, blaming him and his Democrats for the recession. In campaign materials, Tyler was praised for integrity in resigning over the state legislature's instructions. The Whigs initially hoped to muzzle Harrison and Tyler, lest they make policy statements that alienated segments of the party. But after Tyler's Democratic rival, Vice President Johnson, made a successful speaking tour, Tyler was called upon to travel from Williamsburg to

Columbus, Ohio

Columbus () is the state capital and the most populous city in the U.S. state of Ohio. With a 2020 census population of 905,748, it is the 14th-most populous city in the U.S., the second-most populous city in the Midwest, after Chicago, and t ...

, and there address a local convention, in a speech intended to assure Northerners that he shared Harrison's views. In his journey of nearly two months, Tyler made speeches at rallies. He could not avoid questions, and after being heckled into an admission that he supported the Compromise Tariff (many Whigs did not), resorted to quoting from Harrison's vague speeches. In his two-hour speech at Columbus, Tyler entirely avoided the issue of the Bank of the United States, one of the major questions of the day.

To win the election, Whig leaders decided they had to mobilize people across the country, including women, who could not then vote. This was the first time that an American political party included women in campaign activities on a widespread scale, and women in Tyler's Virginia were active on his behalf. The party hoped to avoid issues and win through public enthusiasm, with torchlight processions and alcohol-fueled political rallies.

Seager Seager is a surname, and may refer to:

* Alexandra Seager (1870–1950), businesswoman and philanthropist in South Australia

* Allan Seager (1906–1968), American novelist and short-story writer

* Charles Allen Seager (1872–1948), Anglican Bisho ...

, p. 135. The interest in the campaign was unprecedented, with many public events. When the Democratic press depicted Harrison as an old soldier, who would turn aside from his campaign if given a barrel of

hard cider

Cider ( ) is an alcoholic beverage made from the fermented juice of apples. Cider is widely available in the United Kingdom (particularly in the West Country) and the Republic of Ireland. The UK has the world's highest per capita consumption, ...

to drink in his

log cabin

A log cabin is a small log house, especially a less finished or less architecturally sophisticated structure. Log cabins have an ancient history in Europe, and in America are often associated with first generation home building by settlers.

Eur ...

, the Whigs eagerly seized on the image, and the

log cabin campaign

The 1840 United States presidential election was the 14th quadrennial presidential election, held from Friday, October 30 to Wednesday, December 2, 1840. Economic recovery from the Panic of 1837 was incomplete, and Whig nominee William Henry Har ...

was born. The fact that Harrison lived on a palatial estate along the Ohio River and that Tyler was well-to-do was ignored, while log cabin images appeared everywhere, from banners to whiskey bottles. Cider was the favored beverage of many farmers and tradesmen, and Whigs claimed that Harrison preferred that drink of the common man.

The presidential candidate's military service was emphasized, thus the well known campaign jingle, "

Tippecanoe and Tyler Too

"Tippecanoe and Tyler Too", originally published as "Tip and Ty", was a popular and influential campaign song of the Whig Party's colorful Log Cabin Campaign in the 1840 United States presidential election. Its lyrics sang the praises of Whig ...

", referring to Harrison's victory at the

Battle of Tippecanoe

The Battle of Tippecanoe ( ) was fought on November 7, 1811, in Battle Ground, Indiana, between American forces led by then Governor William Henry Harrison of the Indiana Territory and Native American forces associated with Shawnee leader Tecums ...

.

Glee club

A glee club in the United States is a musical group or choir group, historically of male voices but also of female or mixed voices, which traditionally specializes in the singing of short songs by trios or quartets. In the late 19th century it w ...

s sprouted all over the country, singing patriotic and inspirational songs: one Democratic editor stated that he found the songfests in support of the Whig Party to be unforgettable. Among the lyrics sung were "We shall vote for Tyler therefore/Without a why or wherefore".

[ Crapol, pp. 17–19.] Louis Hatch, in his history of the vice presidency, noted, "the Whigs roared, sang, and hard-cidered the 'hero of Tippecanoe' into the White House".

[ Hatch, p. 193.]

Clay, though embittered by another of his many defeats for the presidency, was appeased by Tyler's withdrawal from the still-unresolved Senate race, which would permit the election of Rives, and campaigned in Virginia for the Harrison/Tyler ticket.

Tyler predicted the Whigs would easily take Virginia; he was embarrassed when he was proved wrong, but was consoled by an overall victory—Harrison and Tyler won by an electoral vote of 234–60 and with 53% of the popular vote. Van Buren took only seven states out of 26. The Whigs gained control of both houses of Congress.

Vice presidency (1841)

As

vice president-elect, Tyler remained quietly at his home in Williamsburg. He privately expressed hopes that Harrison would prove decisive and not allow intrigue in the Cabinet, especially in the first days of the administration.

[ Peterson, p. 34.] Tyler did not participate in selecting the Cabinet, and did not recommend anyone for federal office in the new Whig administration. Beset by office seekers and the demands of Senator Clay, Harrison twice sent Tyler letters asking his advice as to whether a Van Buren appointee should be dismissed. In both cases, Tyler recommended against, and Harrison wrote, "Mr. Tyler says they ought not to be removed, and I will not remove them." The two men met briefly in Richmond in February, and reviewed a parade together,

though they did not discuss politics.

Tyler was sworn in on March 4, 1841, in the

Senate chamber, and delivered a three-minute speech about

states' rights

In American political discourse, states' rights are political powers held for the state governments rather than the federal government according to the United States Constitution, reflecting especially the enumerated powers of Congress and the ...

before swearing in the new senators and then attending

Harrison's inauguration. Following the new president's two-hour speech before a large crowd in freezing weather, Tyler returned to the Senate to receive the president's Cabinet nominations, presiding over the confirmations the following day—a total of two hours as president of the Senate. Expecting few responsibilities, he then left Washington, quietly returning to his home in

Williamsburg. Seager later wrote, "Had William Henry Harrison lived, John Tyler would undoubtedly have been as obscure as any vice-president in American history."

Seager Seager is a surname, and may refer to:

* Alexandra Seager (1870–1950), businesswoman and philanthropist in South Australia

* Allan Seager (1906–1968), American novelist and short-story writer

* Charles Allen Seager (1872–1948), Anglican Bisho ...

, p. 144.

Meanwhile, Harrison struggled to keep up with the demands of Clay and others who sought offices and influence in his administration. Harrison's age and fading health were no secret during the campaign, and the question of presidential succession was on every politician's mind. The first few weeks of the presidency took a toll on Harrison's health, and after being caught in a rainstorm in late March he came down with

pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

and

pleurisy

Pleurisy, also known as pleuritis, is inflammation of the membranes that surround the lungs and line the chest cavity (pleurae). This can result in a sharp chest pain while breathing. Occasionally the pain may be a constant dull ache. Other sy ...

. Secretary of State Daniel Webster sent word to Tyler of Harrison's illness on April 1; two days later, Richmond attorney James Lyons wrote with the news that the president had taken a turn for the worse, remarking, "I shall not be surprised to hear by tomorrow's mail that Gen'l Harrison is no more."

[ Crapol, p. 8.] Tyler decided not to travel to Washington, not wanting to appear unseemly in anticipating Harrison's death. At dawn on April 5, Webster's son

Fletcher

Fletcher may refer to:

People

* Fletcher (occupation), a person who fletches arrows, the origin of the surname

* Fletcher (singer) (born 1994), American actress and singer-songwriter

* Fletcher (surname)

* Fletcher (given name)

Places

United ...

, chief clerk of the State Department, arrived at Tyler's Williamsburg home to officially inform him of Harrison's death the morning before.

[ Hopkins, John Tyler and the Presidential Succession] Tyler left Williamsburg and arrived in Washington at dawn the next day.

Presidency (1841–1845)

Harrison's death in office was an unprecedented event that caused considerable uncertainty about presidential succession.

Article II, Section 1, Clause 6

Article Two of the United States Constitution establishes the executive branch of the federal government, which carries out and enforces federal laws. Article Two vests the power of the executive branch in the office of the president of the Un ...

of the United States Constitution, which governed intra-term presidential succession at the time (now superseded by the

Twenty-fifth Amendment), states:

Interpreting this Constitutional prescription led to the question of whether the actual office of president devolved upon Tyler, or merely its powers and duties.

The Cabinet met within an hour of Harrison's death and, according to a later account, determined that Tyler would be "vice-president

acting president

An acting president is a person who temporarily fills the role of a country's president when the incumbent president is unavailable (such as by illness or a vacation) or when the post is vacant (such as for death, injury, resignation, dismissal ...

". But Tyler firmly and decisively asserted that the Constitution gave him full and unqualified powers of office and had himself sworn in immediately as president, setting a critical precedent for an orderly transfer of power following a president's death.

Judge

William Cranch

William Cranch (July 17, 1769 – September 1, 1855) was a United States federal judge, United States circuit judge and chief judge of the United States Circuit Court of the District of Columbia. A staunch Federalist Party, Federalist and nephe ...

administered the

presidential oath in Tyler's hotel room. Tyler considered the oath redundant to his oath as vice president, but wished to quell any doubt over his accession.

Chitwood Chitwood is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Bill Chitwood (1890–1961), American fiddler

* Christina Chitwood (born 1990), American ice dancer

*Joie Chitwood (1912–1988), American racing driver and businessman

* May Belle Hu ...

, pp. 202–03. When he took office, Tyler, at 51, became the

youngest president to that point. His record was in turn surpassed by his immediate successor

James Polk

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

, who was inaugurated at the age of 49.

"Fearing that he would alienate Harrison's supporters, Tyler decided to keep Harrison's entire cabinet even though several members were openly hostile to him and resented his assumption of the office."

At his first cabinet meeting, Webster informed him of Harrison's practice of making policy by a majority vote. (This was a dubious assertion, since Harrison had held few cabinet meetings and had baldly asserted his authority over the cabinet in at least one.) The Cabinet fully expected the new president to continue this practice. Tyler was astounded and immediately corrected them:

Tyler delivered an informal inaugural address before the

Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of a ...

on April 9, in which he reasserted his belief in fundamental tenets of

Jeffersonian democracy

Jeffersonian democracy, named after its advocate Thomas Jefferson, was one of two dominant political outlooks and movements in the United States from the 1790s to the 1820s. The Jeffersonians were deeply committed to American republicanism, which ...

and limited federal power. Tyler's claim to be president was not immediately accepted by

opposition

Opposition may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Opposition'' (Altars EP), 2011 EP by Christian metalcore band Altars

* The Opposition (band), a London post-punk band

* '' The Opposition with Jordan Klepper'', a late-night television series on Com ...

members of Congress such as

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States S ...

, who felt that Tyler should be a

caretaker

Caretaker may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* ''The Caretaker'' (film), a 1963 adaptation of the play ''The Caretaker''

* '' The Caretakers'', a 1963 American film set in a mental hospital

* Caretaker, a character in the 1974 film '' ...

under the title of "acting president", or remain vice president in name. Among those who questioned Tyler's authority was Clay, who had planned to be "the real power behind a fumbling throne" while Harrison was alive, and intended the same for Tyler.

Clay saw Tyler as the "vice-president" and his presidency as a mere "

regency

A regent (from Latin : ruling, governing) is a person appointed to govern a state '' pro tempore'' (Latin: 'for the time being') because the monarch is a minor, absent, incapacitated or unable to discharge the powers and duties of the monarchy ...

".

Seager Seager is a surname, and may refer to:

* Alexandra Seager (1870–1950), businesswoman and philanthropist in South Australia

* Allan Seager (1906–1968), American novelist and short-story writer

* Charles Allen Seager (1872–1948), Anglican Bisho ...

, pp. 142, 151.

Ratification of the decision by Congress came through the customary notification that it makes to the president, that it is in session and available to receive messages. In both houses, unsuccessful amendments were offered to strike the word "president" in favor of language including the term "vice president" to refer to Tyler. Mississippi Senator

Robert J. Walker, in opposition, said that the idea that Tyler was still vice president and could preside over the Senate was absurd.

[ Dinnerstein, pp. 451–53.] On May 31, 1841, the House passed a joint resolution confirming Tyler as "President of the United States" for the remainder of his term.

On June 1, 1841, the Senate voted in favor of the resolution. Most importantly, Senators Clay and

John C. Calhoun voted with the majority to reject Walker's amendment.

Tyler's opponents never fully accepted him as president. He was called by many mocking nicknames, including "His Accidency". But Tyler never wavered from his conviction that he was the rightful president; when his political opponents sent correspondence to the White House addressed to the "vice president" or "acting president", Tyler had it returned unopened.

Tyler was considered a strong leader for his decisive action on his accession to the presidency. But he generally held a limited view of presidential power, that legislation should be initiated by Congress, and the presidential veto should be only used when a law was unconstitutional or against the national interest.

Economic policy and party conflicts

Like Harrison, Tyler had been expected to adhere to Whig Party Congressional public policies and to defer to Whig party leader Clay. The Whigs especially demanded that Tyler curb the veto power, in response to Jackson's perceived authoritarian presidency. Clay had envisioned Congress to be modeled after a

parliamentary

A parliamentary system, or parliamentarian democracy, is a system of democracy, democratic government, governance of a sovereign state, state (or subordinate entity) where the Executive (government), executive derives its democratic legitimacy ...

-type system where he was the leader. Initially Tyler concurred with the new Whig Congress, signing into law the

preemption bill granting "squatters' sovereignty" to settlers on public land, a Distribution Act (discussed below), a new bankruptcy law, and the repeal of the

Independent Treasury

The Independent Treasury was the system for managing the money supply of the United States federal government through the U.S. Treasury and its sub-treasuries, independently of the national banking and financial systems. It was created on August 6 ...