John Norris (soldier) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir John Norris or ''Norreys'' (''ca.'' 1547 – 3 September 1597), of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an

Sir John Norris or ''Norreys'' (''ca.'' 1547 – 3 September 1597), of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an

In 1577 Norreys led a force of English volunteers to the

In 1577 Norreys led a force of English volunteers to the

On Wednesday 17 April 1589 (although another source gives the date of departure as 18 April), Norreys set out with Drake at the head of a 23,000 strong expeditionary force (which included 19,000 troops and is now termed the

On Wednesday 17 April 1589 (although another source gives the date of departure as 18 April), Norreys set out with Drake at the head of a 23,000 strong expeditionary force (which included 19,000 troops and is now termed the

Sir John Norris or ''Norreys'' (''ca.'' 1547 – 3 September 1597), of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an

Sir John Norris or ''Norreys'' (''ca.'' 1547 – 3 September 1597), of Rycote, Oxfordshire, and of Yattendon and Notley in Berkshire, was an English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

soldier, the son of Henry Norris, 1st Baron Norreys

{{Infobox noble, Baron

, name = Henry Norris

, title = Baron Norreys

, image = Henry Norris 1st Baron Norris of Rycote.jpg

, image_size = 240px

, caption = Henry Norris, aged 60, 1585

, ...

, a lifelong friend of Queen Elizabeth.

The most acclaimed English soldier of his day, Norreys participated in every Elizabethan theatre of war: in the Wars of Religion

A religious war or a war of religion, sometimes also known as a holy war ( la, sanctum bellum), is a war which is primarily caused or justified by differences in religion. In the modern period, there are frequent debates over the extent to wh ...

in France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

during the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Refo ...

of Dutch liberation from Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, in the Anglo-Spanish War, and above all in the Tudor conquest of Ireland

The Tudor conquest (or reconquest) of Ireland took place under the Tudor dynasty, which held the Kingdom of England during the 16th century. Following a failed rebellion against the crown by Silken Thomas, the Earl of Kildare, in the 1530s, ...

.

Early life

The eldest son of Henry Norreys by his marriage to Marjorie Williams, Norreys was born atYattendon Castle

Yattendon Castle was a fortified manor house located in the civil parish of Yattendon, in the hundred of Faircross, in the English county of Berkshire.

History

The site upon which Yattendon castle stood was originally occupied by a moat ...

. His paternal grandfather had been executed after being found guilty of adultery with Queen Anne Boleyn

Anne Boleyn (; 1501 or 1507 – 19 May 1536) was Queen of England from 1533 to 1536, as the second wife of King Henry VIII. The circumstances of her marriage and of her execution by beheading for treason and other charges made her a key f ...

, the mother of Queen Elizabeth. His maternal grandfather was John Williams, Lord Williams of Thame.

Norreys' great uncle had been a guardian of the young Elizabeth, who was well acquainted with the family. She had stayed at Yattendon Castle on her way to imprisonment at Woodstock

Woodstock Music and Art Fair, commonly referred to as Woodstock, was a music festival held during August 15–18, 1969, on Max Yasgur's dairy farm in Bethel, New York, United States, southwest of the town of Woodstock. Billed as "an Aq ...

. The future Queen was a great friend of Norreys' mother, whom she nicknamed "Black Crow" on account of her jet black hair. Norreys inherited his mother's hair colour so that he was known as "Black Jack" by his troops.

Norreys grew up with five brothers, several of whom were to serve alongside him during Elizabeth's wars. He may briefly have attended Magdalen College, Oxford

Magdalen College (, ) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. It was founded in 1458 by William of Waynflete. Today, it is the fourth wealthiest college, with a financial endowment of £332.1 million as of 2019 and one of the s ...

.

In 1566, Norreys' father was posted as English ambassador to France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, and in 1567, when he was about nineteen, Norreys and his elder brother William

William is a male given name of Germanic origin.Hanks, Hardcastle and Hodges, ''Oxford Dictionary of First Names'', Oxford University Press, 2nd edition, , p. 276. It became very popular in the English language after the Norman conquest of Engl ...

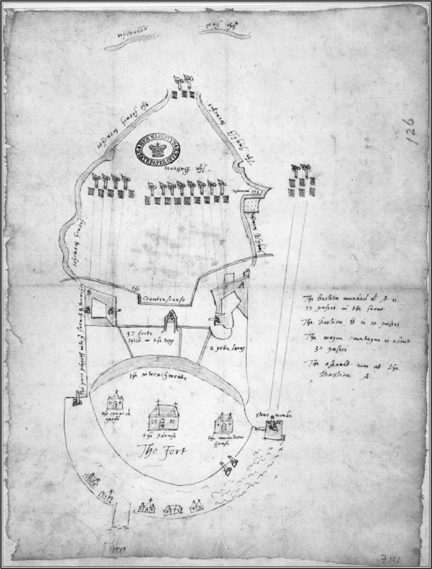

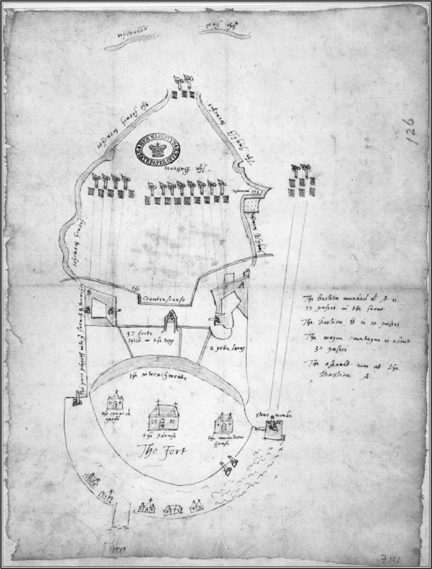

were present at the Battle of Saint Denis. They drew a map of the battle which formed part of their father's report to the Queen.

Early military career

When his father was recalled from France in January 1571, Norreys stayed behind and developed a friendship with the new ambassador,Francis Walsingham

Sir Francis Walsingham ( – 6 April 1590) was principal secretary to Queen Elizabeth I of England from 20 December 1573 until his death and is popularly remembered as her "spymaster".

Born to a well-connected family of gentry, Wals ...

. In 1571, Norreys served as a volunteer under Admiral Coligny

Gaspard de Coligny (16 February 1519 – 24 August 1572), Seigneur de Châtillon, was a French nobleman, Admiral of France, and Huguenot leader during the French Wars of Religion. He served under kings Francis I and Henry II during the Ita ...

, fighting on the Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

side during the French Wars of Religion

The French Wars of Religion is the term which is used in reference to a period of civil war between French Catholic Church, Catholics and Protestantism, Protestants, commonly called Huguenots, which lasted from 1562 to 1598. According to estim ...

.

Two years later, Norreys served as a captain under Sir Walter Devereux, recently created first Earl of Essex

Earl of Essex is a title in the Peerage of England which was first created in the 12th century by King Stephen of England. The title has been recreated eight times from its original inception, beginning with a new first Earl upon each new cre ...

, who was attempting to establish a plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. The ...

in the Irish province of Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

. He supported his elder brother William, who was in command of a troop of a hundred horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million y ...

which had been recruited by their father, then serving as Lord Lieutenant of Berkshire. While here Norreys took part in the massacre of Sir Brian O'Neill's followers. Essex invited O'Neill and his household to a banquet in Belfast in October 1574. O'Neill reciprocated and held a feast which lasted for three days, but on the third day, Norreys and his men slaughtered over 200 of O'Neill's unarmed followers. Essex took Sir Brian, his wife and others to Dublin where they were later executed.

When Essex entered Antrim to attack Sorley Boy MacDonnell

Sorley Boy MacDonnell (Scottish Gaelic: ''Somhairle Buidhe Mac Domhnaill''), also spelt as MacDonald (c. 1505 – 1590), Scoto-Irish chief, was the son of Alexander Carragh MacDonnell, 5th of Dunnyveg, of Dunyvaig Castle, lord of Islay and ...

, it was to Rathlin Island

Rathlin Island ( ga, Reachlainn, ; Local Irish dialect: ''Reachraidh'', ; Scots: ''Racherie'') is an island and civil parish off the coast of County Antrim (of which it is part) in Northern Ireland. It is Northern Ireland's northernmost point. ...

that Sorley Boy and the other Scots sent their wives and children, their aged and sick, for safety. Lord Essex, knowing that the refugees were still on the island, sent orders to Norreys, who was in command at Carrickfergus

Carrickfergus ( , meaning " Fergus' rock") is a large town in County Antrim, Northern Ireland. It sits on the north shore of Belfast Lough, from Belfast. The town had a population of 27,998 at the 2011 Census. It is County Antrim's oldest t ...

, to take a company of soldiers with him, cross over to Rathlin, and kill what he could find. Norreys had brought cannon with him, so that the weak defences were speedily destroyed, and after a fierce assault, in which several of the garrison were killed. The Scots were obliged to yield at discretion and all were killed, except the chief and his family, who were reserved for ransom. The death toll was two hundred. Then it was discovered that several hundred more, chiefly women and children, were hidden in the caves about the shore: they too were attacked and all massacred

A massacre is the killing of a large number of people or animals, especially those who are not involved in any fighting or have no way of defending themselves. A massacre is generally considered to be morally unacceptable, especially when per ...

. A fort was erected on the island, but was evacuated by Norreys, and he was recalled with his troops to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

within 3 months, when it was clear that the colonisation would fail.

In 1577 Norreys led a force of English volunteers to the

In 1577 Norreys led a force of English volunteers to the Low Countries

The term Low Countries, also known as the Low Lands ( nl, de Lage Landen, french: les Pays-Bas, lb, déi Niddereg Lännereien) and historically called the Netherlands ( nl, de Nederlanden), Flanders, or Belgica, is a coastal lowland region in N ...

, where he fought for the States General The word States-General, or Estates-General, may refer to:

Currently in use

* Estates-General on the Situation and Future of the French Language in Quebec, the name of a commission set up by the government of Quebec on June 29, 2000

* States Gener ...

, then in revolt against the rule of the Spanish King Philip II Philip II may refer to:

* Philip II of Macedon (382–336 BC)

* Philip II (emperor) (238–249), Roman emperor

* Philip II, Prince of Taranto (1329–1374)

* Philip II, Duke of Burgundy (1342–1404)

* Philip II, Duke of Savoy (1438-1497)

* Philip ...

at the beginning of the Eighty Years' War

The Eighty Years' War or Dutch Revolt ( nl, Nederlandse Opstand) ( c.1566/1568–1648) was an armed conflict in the Habsburg Netherlands between disparate groups of rebels and the Spanish government. The causes of the war included the Refo ...

. At the battle of Rijmenam (2 August 1578), his force helped defeat the Spanish under the command of John of Austria (''Don Juan de Austria''), the king's brother; Norreys had three horses shot from under him. Throughout 1579, he co-operated with the French army under François de la Noue

François de la Noue (1531 – August 4, 1591), called Bras-de-Fer (Iron Arm), was one of the Huguenot captains of the 16th century. He was born near Nantes in 1531, of an ancient Breton family.

He served in Italy under Marshal Brissac, and in t ...

, and was put in charge of all English troops, about 150-foot and 450 mounted. He took part in the battle of Borgerhout, where the Spanish army under Alexander Farnese Alessandro Farnese may refer to:

* Pope Paul III (1468–1549), Roman Catholic Bishop of Rome

*Alessandro Farnese (cardinal) (1520–1589), Paul's grandson, Roman Catholic bishop and cardinal-nephew

* Alexander Farnese, Duke of Parma (1545–1592), ...

was victorious. Later, he went on to match the Spanish in operations around Meppel and on 9 April 1580, his troops conquered Mechelen

Mechelen (; french: Malines ; traditional English name: MechlinMechelen has been known in English as ''Mechlin'', from where the adjective ''Mechlinian'' is derived. This name may still be used, especially in a traditional or historical contex ...

and brutally sacked the city in what has become known as the '' English Fury''.

On account of these successes, essentially as a mercenary, he boosted the morale in the Protestant armies and became famous in England. The morale of his own troops depended on prompt and regular payment by the States General for their campaign, and Norreys gained a reputation for forceful leadership. In February 1581, he defeated the Count of Rennenburg by relieving Steenwijk under siege and in July inflicted a further defeat at Kollum near Groningen

Groningen (; gos, Grunn or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen province in the Netherlands. The ''capital of the north'', Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of the northern part of t ...

. In September 1581, however, he was dealt a serious defeat by a Spanish army under Colonel Francisco Verdugo

Francisco Verdugo, Spanish military commander in the Dutch Revolt, (born in 1537 in Talavera de la Reina, province of Toledo, died in Luxembourg, 1595), became ''Maestre de Campo General,'' in the Spanish Netherlands. He was also the last Spanish ...

at the Battle of Noordhorn, near Groningen

Groningen (; gos, Grunn or ) is the capital city and main municipality of Groningen province in the Netherlands. The ''capital of the north'', Groningen is the largest place as well as the economic and cultural centre of the northern part of t ...

. The following month Norris later checked Verdugo by repelling him at Niezijl. Later in the year he along with the Count of Hohenlohe helped to relieve the city of Lochem

Lochem () is a city and municipality in the province of Gelderland in the Eastern Netherlands. In 2005, it merged with the municipality of Gorssel, retaining the name of Lochem. As of 2019, it had a population of 33,590.

Population centres

The ...

which had been under siege by Verdugo. After more campaigns in Flanders in support of François, Duke of Anjou

''Monsieur'' Francis, Duke of Anjou and Alençon (french: Hercule François; 18 March 1555 – 10 June 1584) was the youngest son of King Henry II of France and Catherine de' Medici.

Early years

He was scarred by smallpox at age eight, an ...

, Norreys was sent back to the Netherlands as an unofficial ambassador of Elizabeth I. In 1584 he returned to England to encourage an English declaration of war on Spain in order to free the States General from Habsburg domination.

Return to Ireland

In March 1584, Norreys departed the Low Countries and was sent toIreland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

in the following July, when he was appointed president of the province of Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

(at this time, his brother Edward was stationed there). Norris urged the plantation of the province with English settlers (an aim achieved in the following years), but the situation proved so unbearably miserable that many of his soldiers deserted him for the Low Countries.

In September 1584 Norreys accompanied the Lord Deputy of Ireland, Sir John Perrot

Sir John Perrot (7 November 1528 – 3 November 1592) served as lord deputy to Queen Elizabeth I of England during the Tudor conquest of Ireland. It was formerly speculated that he was an illegitimate son of Henry VIII, though the idea is reje ...

, and the earl of Ormonde into Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

. The purpose was to dislodge the Scots in the Route and the Glynns, and Norreys helped seize fifty thousand cattle from the woods of Glenconkyne in order to deprive the enemy of its means of sustenance. The campaign was not quite successful, as the Scots simply regrouped in Kintyre

Kintyre ( gd, Cinn Tìre, ) is a peninsula in western Scotland, in the southwest of Argyll and Bute. The peninsula stretches about , from the Mull of Kintyre in the south to East and West Loch Tarbert in the north. The region immediately north ...

before crossing back to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

once the lord deputy had withdrawn south. Norreys returned to Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

, but was summoned to Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

in 1585 for the opening of parliament. He sat as the member for Cork County

County Cork ( ga, Contae Chorcaí) is the largest and the southernmost county of Ireland, named after the city of Cork, the state's second-largest city. It is in the province of Munster and the Southern Region. Its largest market towns ar ...

and was forcibly eloquent on measures to confirm the queen's authority over the country. He also complained that he was prevented from launching a fresh campaign in Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

.

Anglo-Spanish War

Upon news of the siege ofAntwerp

Antwerp (; nl, Antwerpen ; french: Anvers ; es, Amberes) is the largest city in Belgium by area at and the capital of Antwerp Province in the Flemish Region. With a population of 520,504,

, Norreys urged support for the Dutch Protestants and, transferring the presidency of Munster to his brother, Thomas, he rushed to London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

in May 1585 to prepare for a campaign in the Low Countries. In August he commanded an English army of 4400 men which Elizabeth had sent to support the States General against the Spaniards, in accordance with the Treaty of Nonsuch

The Treaty of Nonsuch was signed on 10 August 1585 by Elizabeth I of England and the Dutch rebels fighting against Spanish rule. It was the first international treaty signed by what would become the Dutch Republic. It was signed at Nonsuch Pala ...

. He gallantly stormed a fort near Arnhem

Arnhem ( or ; german: Arnheim; South Guelderish: ''Èrnem'') is a city and municipality situated in the eastern part of the Netherlands about 55 km south east of Utrecht. It is the capital of the province of Gelderland, located on both banks of ...

; the queen, however, was unhappy at this aggression. Still, his army of untried English foot did repulse the Duke of Parma

The Duke of Parma and Piacenza () was the ruler of the Duchy of Parma and Piacenza, a historical state of Northern Italy, which existed between 1545 and 1802, and again from 1814 to 1859.

The Duke of Parma was also Duke of Piacenza, except ...

in a day-long fight at Aarschot and remained a threat, until supplies of clothing, food and money ran out. His men suffered an alarming mortality rate without support from home, but the aura of invincibility attaching to the Spanish troops had been dispelled, and Elizabeth finally made a full commitment of her forces to the States General.

In December 1585, the Earl of Leicester

Earl of Leicester is a title that has been created seven times. The first title was granted during the 12th century in the Peerage of England. The current title is in the Peerage of the United Kingdom and was created in 1837.

Early creatio ...

arrived with a new army and accepted the position of Governor-General

Governor-general (plural ''governors-general''), or governor general (plural ''governors general''), is the title of an office-holder. In the context of governors-general and former British colonies, governors-general are appointed as viceroy t ...

of the Low Countries, as England went into open alliance. During an attack on Parma, Norreys received a pike wound in the breast, then managed to break through to relieve Grave, the last barrier to the Spanish advance into the north; Leicester knighted him for this victory during a great feast at Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city and a List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, pro ...

on St George's Day

Saint George's Day is the feast day of Saint George, celebrated by Christian churches, countries, and cities of which he is the patron saint, including Bulgaria, England, Georgia, Portugal, Romania, Cáceres, Alcoy, Aragon and Catalonia.

Sa ...

, along with his brothers Edward and Henry. But the Spanish were soon admitted to Grave by treachery, and Norreys advised against Leicester's order to have the traitor beheaded, apparently because he was in love with the traitor's aunt.

The two commanders quarrelled for the rest of the campaign, which turned out a failure. Leicester complained that Norreys was like the Earl of Sussex

Earl of Sussex is a title that has been created several times in the Peerages of England, Great Britain, and the United Kingdom. The early Earls of Arundel (up to 1243) were often also called Earls of Sussex.

The fifth creation came in the Peera ...

in his animosity. His main grievance, though, was the corruption of Norreys' uncle, the campaign's treasurer. Leicester's urgings to recall both Norreys and his uncle, were resisted by the Queen. Norreys continued his good service and was ordered by Leicester to protect Utrecht

Utrecht ( , , ) is the List of cities in the Netherlands by province, fourth-largest city and a List of municipalities of the Netherlands, municipality of the Netherlands, capital and most populous city of the Provinces of the Netherlands, pro ...

in August 1586. The operation did not go smoothly because Leicester had omitted to put Sir William Stanley under Norreys' command. Norreys joined with Stanley in September in the Battle of Zutphen

The Battle of Zutphen was fought on 22 September 1586, near the village of Warnsveld and the town of Zutphen, the Netherlands, during the Eighty Years' War. It was fought between the forces of the United Provinces of the Netherlands, aid ...

, in which Sir Philip Sidney

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek language, Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philip ...

- commanding officer over Norreys' brother, Edward, who was lieutenant in the governorship of Flushing

Flushing may refer to:

Places

* Flushing, Cornwall, a village in the United Kingdom

* Flushing, Queens, New York City

** Flushing Bay, a bay off the north shore of Queens

** Flushing Chinatown (法拉盛華埠), a community in Queens

** Flushin ...

- was fatally wounded. At an officers' supper, Edward took offence at some remarks by Sir William Pelham, marshal of the army, which he thought reflected on the character of his older brother, and an argument with the Dutch host flared up, with Leicester having to mediate between the younger Norreys and his host to prevent a duel.

By the autumn of 1586 Leicester seems to have relented and was full of praise for Norreys, while at the same time the States General held golden opinions of him. But he was recalled in October, and the queen received him with disdain, apparently owing to his enmity for Leicester; within a year he had returned to the Low Countries, where the new commander, Willoughby, recognised that Norreys would be better for the job, with the comment, "''If I were sufficient, Norreys were superfluous''". Willoughby resented having Norris around and observed that he was, "''more happy than a caesar''".

At the beginning of 1588, Norreys returned to England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, where he was presented with the degree of Master of Arts at the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

.

Later in the year, when the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

was expected, he was, under Leicester, marshal of the camp at West Tilbury

West Tilbury is a village and former civil parish on the top of and on the sides of a tall river terrace overlooking the River Thames. Part of the modern town of Tilbury (including part of Tilbury Fort) is within the traditional parish of We ...

when Elizabeth delivered the Speech to the Troops at Tilbury

The Speech to the Troops at Tilbury was delivered on 9 August Old Style (19 August New Style) 1588 by Queen Elizabeth I of England to the land forces earlier assembled at Tilbury in Essex in preparation for repelling the expected invasion by ...

. He inspected the fortification of Dover, and in October returned to the Low Countries as ambassador to the States-General. He oversaw a troop withdrawal in preparation for an expedition to Portugal designed to drive home the English advantage following the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

, when the enemy's fleet was at its weakest.

On Wednesday 17 April 1589 (although another source gives the date of departure as 18 April), Norreys set out with Drake at the head of a 23,000 strong expeditionary force (which included 19,000 troops and is now termed the

On Wednesday 17 April 1589 (although another source gives the date of departure as 18 April), Norreys set out with Drake at the head of a 23,000 strong expeditionary force (which included 19,000 troops and is now termed the English Armada

The English Armada ( es, Invencible Inglesa, lit=English Invincible), also known as the Counter Armada or the Drake–Norris Expedition, was an attack fleet sent against Spain by Queen Elizabeth I of England that sailed on 28 April 1589 during ...

) on a mission to destroy the shipping on the coasts of Spain and to place the pretender to the crown of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

, the Prior of Crato, on the throne. Corunna was surprised, and the lower part of the town burned as Norreys' troops beat off a force of 8,000. Edward was badly wounded in an assault on O Burgo, and his life was only saved by the gallantry of his elder brother. Norreys then attacked Lisbon, but the enemy refused to engage with him, leaving him no option but to put back to sea. Running low on supplies and with his task force reduced by disease and death, Norreys abandoned the secondary objective of attacking the Azores, and the expeditionary force set out to return to England. By the start of July 1589 (Wingfield gives a date of 5 July) the taskforce had all arrived home, some landing back at Plymouth, some at Portsmouth and others London, having achieved little. This "English Armada

The English Armada ( es, Invencible Inglesa, lit=English Invincible), also known as the Counter Armada or the Drake–Norris Expedition, was an attack fleet sent against Spain by Queen Elizabeth I of England that sailed on 28 April 1589 during ...

", was thus an unsuccessful attempt to press home the defeat of the Spanish Armada

The Spanish Armada (a.k.a. the Enterprise of England, es, Grande y Felicísima Armada, links=no, lit=Great and Most Fortunate Navy) was a Spanish fleet that sailed from Lisbon in late May 1588, commanded by the Duke of Medina Sidonia, an aris ...

and bring the war to the ports of Spain's northern coast and to Lisbon

Lisbon (; pt, Lisboa ) is the capital and largest city of Portugal, with an estimated population of 544,851 within its administrative limits in an area of 100.05 km2. Grande Lisboa, Lisbon's urban area extends beyond the city's administr ...

.

From 1591 to 1594 Norreys aided Henry IV of France

Henry IV (french: Henri IV; 13 December 1553 – 14 May 1610), also known by the epithets Good King Henry or Henry the Great, was King of Navarre (as Henry III) from 1572 and King of France from 1589 to 1610. He was the first monarc ...

in his struggle with the Catholic League, fighting for the Protestant cause in Brittany

Brittany (; french: link=no, Bretagne ; br, Breizh, or ; Gallo language, Gallo: ''Bertaèyn'' ) is a peninsula, Historical region, historical country and cultural area in the west of modern France, covering the western part of what was known ...

at the head of 3000 troops. He took Guingamp

Guingamp (; ) is a commune in the Côtes-d'Armor department in Brittany in northwestern France. With a population of 6,895 as of 2017, Guingamp is one of the smallest towns in Europe to have a top-tier professional football team: En Avant Gui ...

and defeated the French Catholic League and their Spanish allies at Château-Laudran. Some of his troops transferred to the Earl of Essex's force in Normandy, and Norreys' campaign proved so indecisive that he left for England in February 1592 and did not return to Brittany until September 1594. He seized the town of Morlaix

Morlaix (; br, Montroulez) is a commune in the Finistère department of Brittany in northwestern France. It is a sub-prefecture of the department.

Leisure and tourism

The old quarter of the town has winding streets of cobbled stones and overha ...

after he had outmanoeuvred the Duke of Mercour and Juan del Águila

Juan Del Águila y Arellano (Ávila, 1545 – A Coruña, August 1602) was a Spanish general. He commanded the Spanish expeditionary Tercio troops in Sicily then in Brittany (1584–1598, also sending a detachment to raid England), before s ...

. Afterwards, he was part of the force that besieged and brutally assaulted and captured Fort Crozon outside Brest

Brest may refer to:

Places

*Brest, Belarus

**Brest Region

**Brest Airport

**Brest Fortress

* Brest, Kyustendil Province, Bulgaria

* Břest, Czech Republic

*Brest, France

** Arrondissement of Brest

**Brest Bretagne Airport

** Château de Brest

*Br ...

, defended by 400 Spanish troops, as well as foiling the relief army under Águila. This was his most notable military success, despite heavy casualties and suffering wounds himself. His youngest brother, Maximilian, was slain while serving under him in this year. Having fallen foul of his French colleagues, Norreys returned from Brest at the end of 1594.

Return to Ulster

Norreys was selected as the military commander under the new lord deputy of Ireland, Sir William Russell, in April 1595. The waspish Russell had been governor of Flushing, but the two men were on bad terms. SirRobert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex

Robert Devereux, 2nd Earl of Essex, KG, PC (; 10 November 1565 – 25 February 1601) was an English nobleman and a favourite of Queen Elizabeth I. Politically ambitious, and a committed general, he was placed under house arrest following ...

had wanted his men placed as Russell's subordinates, but Norreys rejected this and was issued with a special patent that made him independent of the lord deputy's authority in Ulster. It was expected that the terror of the reputation he had gained in combatting the Spanish would be sufficient to cause the rebellion to collapse.

Norreys arrived at Waterford

"Waterford remains the untaken city"

, mapsize = 220px

, pushpin_map = Ireland#Europe

, pushpin_map_caption = Location within Ireland##Location within Europe

, pushpin_relief = 1

, coordinates ...

in May 1595, but was struck with malaria

Malaria is a mosquito-borne infectious disease that affects humans and other animals. Malaria causes symptoms that typically include fever, tiredness, vomiting, and headaches. In severe cases, it can cause jaundice, seizures, coma, or death. S ...

on disembarking. In June, he set out from Dublin with 2,900 men and artillery, with Russell trailing him through Dundalk. After flourishing his letters patent at Drogheda

Drogheda ( , ; , meaning "bridge at the ford") is an industrial and port town in County Louth on the east coast of Ireland, north of Dublin. It is located on the Dublin–Belfast corridor on the east coast of Ireland, mostly in County Louth ...

upon the proclamation of Hugh O'Neill, 3rd Earl of Tyrone

Hugh O'Neill ( Irish: ''Aodh Mór Ó Néill''; literally ''Hugh The Great O'Neill''; – 20 July 1616), was an Irish Gaelic lord, Earl of Tyrone (known as the Great Earl) and was later created ''The Ó Néill Mór'', Chief of the Name. O'Nei ...

, as a traitor, Norreys made his headquarters at Newry

Newry (; ) is a city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Clanrye river in counties Armagh and Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry was founded in 1144 alongside a Cistercian monastery, althoug ...

and fortified Armagh

Armagh ( ; ga, Ard Mhacha, , "Macha's height") is the county town of County Armagh and a city in Northern Ireland, as well as a civil parish. It is the ecclesiastical capital of Ireland – the seat of the Archbishops of Armagh, the Pri ...

cathedral. On learning that artillery was stored at Newry

Newry (; ) is a city in Northern Ireland, divided by the Clanrye river in counties Armagh and Down, from Belfast and from Dublin. It had a population of 26,967 in 2011.

Newry was founded in 1144 alongside a Cistercian monastery, althoug ...

, Tyrone dismantled his stronghold of Dungannon castle and entered the field. Norreys camped his troops along the River Blackwater, while Tyrone roamed the far bank; a ford was secured but no crossing was attempted because there was no harvest to destroy and a tour within enemy territory would have been futile.

So long as Russell was with the army, Norreys refused to assume full responsibility, which prompted the lord deputy to return to Dublin in July 1595, leaving his commander a free hand in the conquest of Ulster. But already, Norreys had misgivings: he thought the task impossible without reinforcements and accused Russell of thwarting him and of concealing from the London government the imperfections of the army. He informed the queen's secretary, Sir William Cecil, that the rebels were far superior in strength, arms and munitions to those previously encountered, and that the English needed commensurate reinforcement.

So quickly did the situation deteriorate, that Norreys declined to risk marching his troops 10 miles through the Moyry Pass

The Moyry Pass is a geographical feature in Ireland. It is a mountain pass running along Slieve Gullion between Newry and Dundalk. It is also known as the Gap of the North.Spring p.105

The pass was of historical military importance as it controll ...

, from Newry to Dundalk, choosing instead to move them by sea; but in a blow to his reputation, Russell confounded him later that summer by brazenly marching up to the Blackwater with little difficulty. More troops were shipped into Ireland, and the companies were ordered to take on 20 Irishmen apiece, which was admitted to be risky. But Norreys still complained that his units were made up of poor old ploughmen and rogues.

Tyrone presented Norreys with his written submission, but this was rejected on the advice of the Dublin council, owing to Tyrone's demand for recognition of his local supremacy. Norris could not draw his enemy out and decided to winter at Armagh, which he revictualled in September 1595. But a second trip was necessary because of a lack of draught horses, and on the return march, while fortifying a pass between Newry and Armagh, Norreys was wounded in the arm and side (and his brother too) at the Battle of Mullabrack near modern-day Markethill, where the enemy cavalry was noted to be more enterprising than had been expected. (Norreys had once commented that Irish cavalry was fit only to catch cows.) The rebels had also attacked in the Moyry pass upon the army's first arrival but had been repelled.

With approval from London, Norreys backed off Tyrone, for fear of Spanish and papal intervention, and a truce was arranged, to expire on 1 January 1596; this was extended to May. In the following year, a new arrangement was entered by Norreys at Dundalk, which Russell criticised since it allowed Tyrone to win time for outside intervention. To Russell's way of thinking, Norreys was too well affected to Tyrone, and his tendency to show mercy to the conquered was wholly unsuited to the circumstances. In May, Tyrone informed Norreys of his meeting with a Spaniard from a ship that had put into Killybegs, and assured him that he had refused such aid as had been offered by Philip II of Spain

Philip II) in Spain, while in Portugal and his Italian kingdoms he ruled as Philip I ( pt, Filipe I). (21 May 152713 September 1598), also known as Philip the Prudent ( es, Felipe el Prudente), was King of Spain from 1556, King of Portugal from ...

.

Owing to troubles in the province of Connaught, Norreys travelled there with Sir Geoffrey Fenton

Sir Geoffrey Fenton (c. 1539 – 19 October 1608) was an English writer, Privy Councillor, and Principal Secretary of State in Ireland.

Early literary years

Geoffrey (spelt Jeffrey by Lodge) was born in 1539, the son of Henry Fenton of Sturton ...

in June 1596 to parley with the local lords. He censured the presidential government of Sir Richard Bingham for having stirred up the lords into rebellion - although the influence of Tyrone's ally, Hugh Roe O'Donnell

Hugh Roe O'Donnell ( Irish: ''Aodh Ruadh Ó Domhnaill''), also known as Red Hugh O'Donnell (30 October 1572 – 10 September 1602), was a sixteenth-century leader of the Gaelic nobility of Ireland. He became Chief of the Name of Clan O'Donne ...

, in this respect was also recognised, especially since Sligo castle had lately fallen to the rebels. Bingham was suspended and detained in Dublin (he was later detained in the Fleet in London). However, during a campaign of six months, Norreys failed to restore peace to Connaught, and despite a nominal submission by the lords, hostilities broke out again as soon as he had returned north to Newry in December 1596.

At this point, Norreys was heartily sick of his situation. He sought to be recalled, citing poor health and the effect upon him of various controversies. As always, Russell weighed in with criticism and claimed that Norreys was feigning poor health in Athlone and seeking to have the lord deputy caught up in his failure. An analysis of this situation in October 1596, which was backed by the Earl of Essex, had it that Norreys' style was "''to invite to dance and be merry upon false hopes of a hollow peace''". This approach was in such contrast to Russell's instincts that there was a risk of collapse in the Irish government.

In the end, it was decided in late 1596 to remove both men from Ulster, sending Russell back to England and Norreys to Munster. Being unclear as to how Dublin wanted to deal with him, Norreys remained at Newry negotiating with Tyrone, while Russell was replaced as lord deputy by Thomas Burgh, 7th Baron Strabolgi

Thomas Burgh, 3rd Baron Burgh KGCharles Mosley, editor, ''Burke's Peerage, Baronetage & Knightage'', 107th edition, 3 volumes (Wilmington, Delaware, U.S.A.: Burke's Peerage (Genealogical Books) Ltd, 2003), volume 1, page 587. (; ; pronounced: ' ...

. Burgh too had been on bad terms with Norreys during his tour of duty in the Low Countries, and was an Essex man to boot, a point which had grated with Cecil, who maintained his confidence in the experience command of Norreys. Although he did meet the new lord deputy at Dublin "''with much counterfeit kindness''", Norreys felt the new appointment as a disgrace upon himself.

Death

Norreys returned toMunster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

to serve as president, but his health was fragile and he soon sought leave to give up his responsibilities. He complained that he had "''lost more blood in her Majesty's service than any he knew''". At his brother's house in Mallow, he developed gangrene, owing to poor treatment of old wounds, and was also suffering from a settled melancholia

Melancholia or melancholy (from el, µέλαινα χολή ',Burton, Bk. I, p. 147 meaning black bile) is a concept found throughout ancient, medieval and premodern medicine in Europe that describes a condition characterized by markedly d ...

over the disregard by the crown of his 26 years service. On 3 September 1597 he went up to his chamber, where he died in the arms of his brother Thomas.Nolan, Sir John Norreys, p. 239

It was generally supposed that his death was caused by a broken heart. Another version, recounted by Philip O'Sullivan Beare, states that a servant boy, on seeing Norreys go into the chamber in the company of a shadowy figure, had listened at the door and heard the soldier enter a pact with the Devil. At midnight the pact was enforced, and on breaking in the door the next morning the frightened servants found that Norreys' head and upper chest were facing backwards.

Norreys' body was embalmed, and the queen sent a letter of condolence to his parents, who had by now lost several of their sons in the Irish service. He was interred in Yattendon

Yattendon is a small village and civil parish northeast of Newbury in the county of Berkshire. The M4 motorway passes through the fields of the village which lie south and below the elevations of its cluster. The village is privately owned ...

Church, Berkshire

Berkshire ( ; in the 17th century sometimes spelt phonetically as Barkeshire; abbreviated Berks.) is a historic county in South East England. One of the home counties, Berkshire was recognised by Queen Elizabeth II as the Royal County of Berk ...

- a monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, hist ...

there has his helmet hanging above - and his effigy

An effigy is an often life-size sculptural representation of a specific person, or a prototypical figure. The term is mostly used for the makeshift dummies used for symbolic punishment in political protests and for the figures burned in certai ...

(portrait by Zucchero, engraved by J. Thane.) was placed on the Norreys monument

A monument is a type of structure that was explicitly created to commemorate a person or event, or which has become relevant to a social group as a part of their remembrance of historic times or cultural heritage, due to its artistic, hist ...

in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Legacy

In 1600, during the course of the Nine Years' War, Sir Charles Blount, Lord Mountjoy, the commander who eventually defeated Tyrone, built a double-ditch fort between Newry and Armagh, which he named Mountnorris in honour of Norreys. It was built on a round earthwork believed to have been constructed by the Danes on a site that Norreys had once considered in the course of his northern campaign. Mountjoy referred to Norreys as his tutor in war, and took note of his former understanding that Ireland was not to be brought to obedience except by force and large permanent garrisons. But Norreys' conduct at the start of the Nine Years' War suggests a mellowing during his maturity. Ironically, the aggressiveEssex

Essex () is a county in the East of England. One of the home counties, it borders Suffolk and Cambridgeshire to the north, the North Sea to the east, Hertfordshire to the west, Kent across the estuary of the River Thames to the south, and G ...

- an equally ill-fated hero of the people - also came to temporise with Tyrone, and it was Norreys' original notion that eventually succeeded under the generalship of Mountjoy.

The most significant legacy of Norreys' long military career lay in his support of the rebellion in the Netherlands against the Habsburg forces, and later in helping the French in holding Brittany against the Catholic League and Habsburg Spain.

Family

Norreys never married, and he had no children. Norreys is pronounced "Norr-iss".See also

*English Armada

The English Armada ( es, Invencible Inglesa, lit=English Invincible), also known as the Counter Armada or the Drake–Norris Expedition, was an attack fleet sent against Spain by Queen Elizabeth I of England that sailed on 28 April 1589 during ...

(Drake-Norris Expedition)

References

Bibliography

* John S Nolan, ''Sir John Norreys and the Elizabethan Military World'' (University of Exeter, 1997) * Richard Bagwell, ''Ireland under the Tudors'' 3 vols. (London, 1885–1890) * John O'Donovan (ed.) ''Annals of Ireland by the Four Masters'' (1851). * ''Calendar of State Papers: Carew MSS.'' 6 vols (London, 1867–1873). * ''Calendar of State Papers: Ireland'' (London) * Nicholas Canny ''The Elizabethan Conquest of Ireland'' (Dublin, 1976); ''Kingdom and Colony'' (2002). * Steven G. Ellis ''Tudor Ireland'' (London, 1985) . * Hiram Morgan ''Tyrone's War'' (1995). * Standish O'Grady (ed.) "''Pacata Hibernia''" 2 vols. (London, 1896). * Cyril Falls ''Elizabeth's Irish Wars'' (1950; reprint London, 1996) . * *External links

* * {{DEFAULTSORT:Norreys, John 1540s births 1597 deaths People from Yattendon People from Oxfordshire People of Elizabethan Ireland English knights 16th-century English soldiersJohn

John is a common English name and surname:

* John (given name)

* John (surname)

John may also refer to:

New Testament

Works

* Gospel of John, a title often shortened to John

* First Epistle of John, often shortened to 1 John

* Secon ...

Irish MPs 1585–1586

Members of the Parliament of Ireland (pre-1801) for County Cork constituencies

Knights Bachelor

Eldest sons of British hereditary barons

Heirs apparent who never acceded

Military personnel from Berkshire