John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and

Founding Father

The following list of national founding figures is a record, by country, of people who were credited with establishing a state. National founders are typically those who played an influential role in setting up the systems of governance, (i.e. ...

who served as the second

president of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the Federal government of the United States#Executive branch, executive branch of the Federal gove ...

from 1797 to 1801. Before

his presidency, he was a leader of the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

that achieved independence from

Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It ...

, and during the war served as a diplomat in Europe. He was twice elected

vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

, serving from 1789 to 1797 in a prestigious role with little power. Adams was a dedicated diarist and regularly corresponded with many important contemporaries, including his wife and adviser

Abigail Adams

Abigail Adams ( ''née'' Smith; November 22, [ O.S. November 11] 1744 – October 28, 1818) was the wife and closest advisor of John Adams, as well as the mother of John Quincy Adams. She was a founder of the United States, a ...

as well as his friend and rival

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

.

A lawyer and political activist prior to the Revolution, Adams was devoted to the

right to counsel and

presumption of innocence

The presumption of innocence is a legal principle that every person accused of any crime is considered innocent until proven guilty. Under the presumption of innocence, the legal burden of proof is thus on the prosecution, which must presen ...

. He defied anti-British sentiment and successfully defended British soldiers against murder charges arising from the

Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre (known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street) was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing t ...

. Adams was a

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

delegate to the

Continental Congress

The Continental Congress was a series of legislative bodies, with some executive function, for thirteen of Britain's colonies in North America, and the newly declared United States just before, during, and after the American Revolutionary War. ...

and became a leader of the revolution. He assisted Jefferson in drafting the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

in 1776. As a diplomat in Europe, he helped negotiate a

peace treaty with Great Britain and secured vital governmental loans. Adams was the primary author of the

Massachusetts Constitution

The Constitution of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts is the fundamental governing document of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, one of the 50 individual state governments that make up the United States of America. As a member of the Massachuset ...

in 1780, which influenced the United States

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these pr ...

, as did his essay ''

Thoughts on Government

''Thoughts on Government'', or in full ''Thoughts on Government, Applicable to the Present State of the American Colonies'', was written by John Adams during the spring of 1776 in response to a resolution of the North Carolina Provincial Congress ...

''.

Adams was elected to two terms as vice president under President George Washington and was elected as the United States' second president in

1796

Events

January–March

* January 16 – The first Dutch (and general) elections are held for the National Assembly of the Batavian Republic. (The next Dutch general elections are held in 1888.)

* February 1 – The capital ...

. He was the only president elected under the banner of the

Federalist Party

The Federalist Party was a conservative political party which was the first political party in the United States. As such, under Alexander Hamilton, it dominated the national government from 1789 to 1801.

Defeated by the Jeffersonian Repu ...

. During his single term, Adams encountered fierce criticism from the

Jeffersonian Republicans and from some in his own Federalist Party, led by his rival

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charle ...

. Adams signed the controversial

Alien and Sedition Acts, and built up the

Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

and

Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and related functions. It in ...

in the undeclared naval war (called the "

Quasi-War

The Quasi-War (french: Quasi-guerre) was an undeclared naval war fought from 1798 to 1800 between the United States and the French First Republic, primarily in the Caribbean and off the East Coast of the United States. The ability of Congress ...

") with

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. During his term, he became the first president to reside in the executive mansion now known as the

White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in ...

.

In his bid for

reelection

The incumbent is the current holder of an office or position, usually in relation to an election. In an election for president, the incumbent is the person holding or acting in the office of president before the election, whether seeking re-el ...

, opposition from Federalists and accusations of despotism from Jeffersonians led to Adams losing to his vice president and former friend Jefferson, and he retired to Massachusetts. He eventually resumed his friendship with Jefferson by initiating a correspondence that lasted fourteen years. He and his wife generated the

Adams political family

The Adams family was a prominent political family in the United States from the late 18th through the early 20th centuries. Based in eastern Massachusetts, they formed part of the Boston Brahmin community. The family traces to Henry Adams of Ba ...

, a line of politicians, diplomats, and historians. It includes their son

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

, the sixth president. John Adams died on July 4, 1826 – the fiftieth anniversary of the adoption of the Declaration of Independence – hours after Jefferson's death. Adams and his son are the only

presidents of the first twelve who never owned slaves. Surveys of historians and scholars have

favorably ranked his administration.

Early life and education

John Adams was born on October 30, 1735 (October 19, 1735,

Old Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

,

Julian calendar

The Julian calendar, proposed by Roman consul Julius Caesar in 46 BC, was a reform of the Roman calendar. It took effect on , by edict. It was designed with the aid of Greek mathematicians and astronomers such as Sosigenes of Alexandri ...

), to

John Adams Sr.

John Adams Sr. (February 8, 1691 – May 25, 1761), also known as Deacon John, was a British-North American colonial farmer and minister. He was the father of the second U.S. president, John Adams Jr., and grandfather of the sixth president ...

and

Susanna Boylston

Susanna Boylston Adams Hall (March 5, 1708 – April 17, 1797) was a prominent early-American socialite, mother of the second U.S. president, John Adams and the paternal grandmother of the sixth president, John Quincy Adams.

Early life

Sus ...

. He had two younger brothers: Peter (1738–1823) and

Elihu (1741–1775). Adams was

born on the family farm in

Braintree,

Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut Massachusett_writing_systems.html" ;"title="nowiki/> məhswatʃəwiːsət.html" ;"title="Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət">Massachusett writing systems">məhswatʃəwiːsət'' En ...

. His mother was from a leading medical family of present-day

Brookline, Massachusetts

Brookline is a town in Norfolk County, Massachusetts, in the United States, and part of the Boston metropolitan area. Brookline borders six of Boston's neighborhoods: Brighton, Allston, Fenway–Kenmore, Mission Hill, Jamaica Plain, and ...

. His father was a

deacon

A deacon is a member of the diaconate, an office in Christian churches that is generally associated with service of some kind, but which varies among theological and denominational traditions. Major Christian churches, such as the Catholic Chur ...

in the

Congregational Church

Congregational churches (also Congregationalist churches or Congregationalism) are Protestant churches in the Calvinist tradition practising congregationalist church governance, in which each congregation independently and autonomously runs its ...

, a farmer, a

cordwainer

A cordwainer () is a shoemaker who makes new shoes from new leather. The cordwainer's trade can be contrasted with the cobbler's trade, according to a tradition in Britain that restricted cobblers to repairing shoes. This usage distinction is ...

, and a lieutenant in the

militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

. Adams often praised his father and recalled their close relationship. Adams's great-great-grandfather

Henry Adams

Henry Brooks Adams (February 16, 1838 – March 27, 1918) was an American historian and a member of the Adams political family, descended from two U.S. Presidents.

As a young Harvard graduate, he served as secretary to his father, Charles Fran ...

immigrated to Massachusetts from

Braintree, Essex

Braintree is a town and former civil parish in Essex, England. The principal settlement of Braintree District, it is located northeast of Chelmsford and west of Colchester. According to the 2011 Census, the town had a population of 41,634, ...

, England, around 1638.

Adams' formal education began at age six at a

dame school

Dame schools were small, privately run schools for young children that emerged in the British Isles and its colonies during the early modern period. These schools were taught by a “school dame,” a local woman who would educate children f ...

for boys and girls, conducted at a teacher's home, and was centered upon ''

The New England Primer

''The New England Primer'' was the first reading primer designed for the American colonies. It became the most successful educational textbook published in 17th-century colonial United States and it became the foundation of most schooling befor ...

''. He then attended Braintree Latin School under Joseph Cleverly, where studies included Latin, rhetoric, logic, and arithmetic. Adams's early education included incidents of truancy, a dislike for his master, and a desire to become a farmer. All discussion on the matter ended with his father's command that he remain in school: "You shall comply with my desires." Deacon Adams hired a new schoolmaster named Joseph Marsh, and his son responded positively. Adams later noted that "As a child I enjoyed perhaps the greatest of blessings that can be bestowed upon men – that of a mother who was anxious and capable to form the characters of her children."

College education and adulthood

At age sixteen, Adams entered

Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher ...

in 1751, studying under

Joseph Mayhew Joseph Mayhew (1709/10 – 1782), eldest son of Deacon Simon and Ruth Mayhew, graduated from Harvard in 1730. His career included being a tutor of John Adams at Harvard, a Preacher, and Chief Justice of Dukes County, Massachusetts.

Joseph Mayhew wa ...

. As an adult, Adams was a keen scholar, studying the works of ancient writers such as

Thucydides

Thucydides (; grc, , }; BC) was an Athenian historian and general. His '' History of the Peloponnesian War'' recounts the fifth-century BC war between Sparta and Athens until the year 411 BC. Thucydides has been dubbed the father of " scienti ...

,

Plato

Plato ( ; grc-gre, Πλάτων ; 428/427 or 424/423 – 348/347 BC) was a Greek philosopher born in Athens during the Classical period in Ancient Greece. He founded the Platonist school of thought and the Academy, the first institution ...

,

Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the esta ...

, and

Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his two major works—the ...

in their original languages. Though his father expected him to be a minister, after his 1755 graduation with an

A.B. degree, he taught school temporarily in

Worcester

Worcester may refer to:

Places United Kingdom

* Worcester, England, a city and the county town of Worcestershire in England

** Worcester (UK Parliament constituency), an area represented by a Member of Parliament

* Worcester Park, London, Engla ...

, while pondering his permanent vocation. In the next four years, he began to seek prestige, craving "Honour or Reputation" and "more from

isfellows", and was determined to be "a great Man". He decided to become a lawyer to further those ends, writing his father that he found among lawyers "noble and gallant achievements" but, among the clergy, the "pretended sanctity of some absolute dunces". He had reservations about his self-described "trumpery" and failure to share the "happiness of

isfellow men".

When the

French and Indian War

The French and Indian War (1754–1763) was a theater of the Seven Years' War, which pitted the North American colonies of the British Empire against those of the French, each side being supported by various Native American tribes. At the st ...

began in 1754, Adams, aged nineteen, felt guilty he was the first in his family not to be a militia officer. He did not go to war, but said "I longed more ardently to be a Soldier than I ever did to be a Lawyer".

Law practice and marriage

In 1756, Adams began

reading law

Reading law was the method used in common law countries, particularly the United States, for people to prepare for and enter the legal profession before the advent of law schools. It consisted of an extended internship or apprenticeship under th ...

under James Putnam, a leading lawyer in Worcester. In 1758, he earned an

A.M. from Harvard, and in 1759 was admitted to the bar. He developed an early habit of writing about events and impressions of men in his diary; this included

James Otis Jr.'s 1761 legal argument challenging the legality of British

writs of assistance

In common law, a writ (Anglo-Saxon ''gewrit'', Latin ''breve'') is a formal written order issued by a body with administrative or judicial jurisdiction; in modern usage, this body is generally a court. Warrants, prerogative writs, subpoena ...

, allowing the British to search a home without notice or reason. Otis's argument inspired Adams to the cause of the

American colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

.

A group of Boston businessmen had been appalled at the writs of assistance that the crown had started issuing to clamp down on colonial smuggling. Writs of assistance were not only search warrants without any limits, they also required local sheriffs, and even local citizens, to assist in breaking into colonists' houses or lend whatever assistance customs officials desired.

[Sabine, Lorenzo. ''The American Loyalists'', pp. 328–29, Charles C. Little and James Brown, Boston, Massachusetts, 1847.][Miller, John C. ''Origins of the American Revolution,'' pp 46–47, Little, Brown & Company, Boston, Massachusetts, 1943.] The outraged businessmen engaged lawyer James Otis Jr. to challenge writs of assistance in court. Otis gave the speech of his life, making references to the

Magna Carta

(Medieval Latin for "Great Charter of Freedoms"), commonly called (also ''Magna Charta''; "Great Charter"), is a royal charter of rights agreed to by King John of England at Runnymede, near Windsor, on 15 June 1215. First drafted by t ...

, classical allusions,

natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

, and the colonists' "rights as Englishmen".

[Nash, Gary B. ''The Unknown American Revolution,'' pp 21-23, Viking, New York, New York, 2005. .]

The court ruled against the merchants. However, the case lit the fire that became the American Revolution. Otis's arguments were published in the colonies, and stirred widespread support for colonial rights. As a young lawyer, John Adams was observing the case in the packed courtroom, and was moved by Otis's performance and legal arguments. Adams later said that "Then and there the child Independence was born."

In 1763, Adams explored various aspects of political theory in seven essays written for Boston newspapers. He offered them anonymously, under the

pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

"Humphrey Ploughjogger", and in them ridiculed the selfish thirst for power he perceived among the Massachusetts colonial elite. Adams was initially less well known than his older cousin

Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams ( – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, an ...

, but his influence emerged from his work as a constitutional lawyer, his analysis of history, and his dedication to

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. ...

. Adams often found his own irascible nature a constraint in his political career.

In the late 1750s, Adams fell in love with Hannah Quincy; while they were alone, he was poised to propose but was interrupted by friends, and the moment was lost. In 1759, he met 15-year-old

Abigail Smith, his third cousin, through his friend Richard Cranch, who was courting Abigail's older sister. Adams initially was not impressed with Abigail and her two sisters, writing that they were not "fond, nor frank, nor candid". In time, he grew close to Abigail and they were married on October 25, 1764, despite the opposition of Abigail's haughty mother. They shared a love of books and kindred personalities that proved honest in their praise and criticism of each other. After his father's death in 1761, Adams had inherited a farm and

a house where they lived until 1783.

John and Abigail had six children:

Abigail

Abigail () was an Israelite woman in the Hebrew Bible married to Nabal; she married the future King David after Nabal's death ( 1 Samuel ). Abigail was David's second wife, after Saul and Ahinoam's daughter, Michal, whom Saul later ma ...

"Nabby" in 1765, future president

John Quincy Adams

John Quincy Adams (; July 11, 1767 – February 23, 1848) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, and diarist who served as the sixth president of the United States, from 1825 to 1829. He previously served as the eighth United States ...

in 1767, Susanna in 1768,

Charles

Charles is a masculine given name predominantly found in English and French speaking countries. It is from the French form ''Charles'' of the Proto-Germanic name (in runic alphabet) or ''*karilaz'' (in Latin alphabet), whose meaning was " ...

in 1770,

Thomas

Thomas may refer to:

People

* List of people with given name Thomas

* Thomas (name)

* Thomas (surname)

* Saint Thomas (disambiguation)

* Thomas Aquinas (1225–1274) Italian Dominican friar, philosopher, and Doctor of the Church

* Thomas the A ...

in 1772, and Elizabeth in 1777. Susanna died when she was one year old, while Elizabeth was stillborn. All three of his sons became lawyers. Charles and Thomas were unsuccessful, became alcoholics, and died before old age, while John Quincy excelled and launched a career in politics. Adams's writings are devoid of his feelings about the sons' fates.

Career before the Revolution

Opponent of Stamp Act

Adams rose to prominence leading widespread opposition to the

Stamp Act of 1765

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765 (5 Geo. III c. 12), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British colonies in America and required that many printed materials ...

. The Act was imposed by the

British Parliament

The Parliament of the United Kingdom is the supreme legislative body of the United Kingdom, the Crown Dependencies and the British Overseas Territories. It meets at the Palace of Westminster, London. It alone possesses legislative suprem ...

without consulting the American legislatures. It required payment of a direct tax by the colonies for stamped documents,

and was designed to pay for the costs of Britain's war with France. Power of enforcement was given to British

vice admiralty court

Vice Admiralty Courts were juryless courts located in British colonies that were granted jurisdiction over local legal matters related to maritime activities, such as disputes between merchants and seamen.

American Colonies

American maritime ac ...

s, rather than

common law

In law, common law (also known as judicial precedent, judge-made law, or case law) is the body of law created by judges and similar quasi-judicial tribunals by virtue of being stated in written opinions."The common law is not a brooding omniprese ...

courts.

These Admiralty courts acted without juries and were greatly disliked.

The Act was despised for both its monetary cost and implementation without colonial consent, and encountered violent resistance, preventing its enforcement. Adams authored the "

Braintree Instructions" in 1765, in the form of a letter sent to the representatives of Braintree in the Massachusetts legislature. In it, he explained that the Act should be opposed since it denied two fundamental rights guaranteed to all Englishmen (and which all free men deserved): rights to be taxed only by consent and to be tried by a jury of one's peers. The instructions were a succinct and forthright defense of colonial rights and liberties, and served as a model for other towns' instructions.

Adams also reprised his pen name "Humphrey Ploughjogger" in opposition to the Stamp Act in August of that year. Included were four articles to the ''

Boston Gazette

The ''Boston Gazette'' (1719–1798) was a newspaper published in Boston, in the British North American colonies. It was a weekly newspaper established by William Brooker, who was just appointed Postmaster of Boston, with its first issue release ...

''. The articles were republished in ''The London Chronicle'' in 1768 as ''True Sentiments of America'', also known as ''A Dissertation on the Canon and Feudal Law''. He also spoke in December before the governor and council, pronouncing the Stamp Act invalid in the absence of Massachusetts representation at Parliament. He noted that many protests were sparked by a popular sermon of Boston minister

Jonathan Mayhew

Jonathan Mayhew (October 8, 1720 – July 9, 1766) was a noted American Congregational minister at Old West Church, Boston, Massachusetts.

Early life

Mayhew was born at Martha's Vineyard, being fifth in descent from Thomas Mayhew (1592–16 ...

, invoking

Romans 13 to justify insurrection. While Adams took a strong stand against the Act in writing, he rebuffed attempts by Samuel Adams, a leader in the popular protest movements, to involve him in mob actions and public demonstrations. In 1766, a town meeting of Braintree elected Adams as a selectman.

With the repeal of the Stamp Act in early 1766, tensions with Britain temporarily eased. Putting politics aside, Adams moved his family to Boston in April 1768 to focus on his law practice. The family rented a clapboard house on

Brattle Street that was known locally as the "White House". He, Abigail, and the children lived there for a year, then moved to Cold Lane; still, later, they moved again to a larger house in Brattle Square in the center of the city. In 1768, Adams successfully defended the merchant

John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor o ...

, who was accused of violating British acts of trade in the

Liberty Affair

The Liberty Affair was an incident that culminated to a riot in 1768, leading to the Boston Massacre on March 5, 1770. It involved the illegal British seizure of the ''Liberty,'' a ship owned by smuggler and merchant John Hancock. This incident, wh ...

. With the death of

Jeremiah Gridley

Jeremiah Gridley or Jeremy Gridley (1702–1767) was a lawyer, editor, colonial legislator, and attorney general in Boston, Massachusetts, in the 18th century. He served as "Grand Master of the Masons in North America" around the 1760s, and wa ...

and the mental collapse of Otis, Adams became Boston's most prominent lawyer.

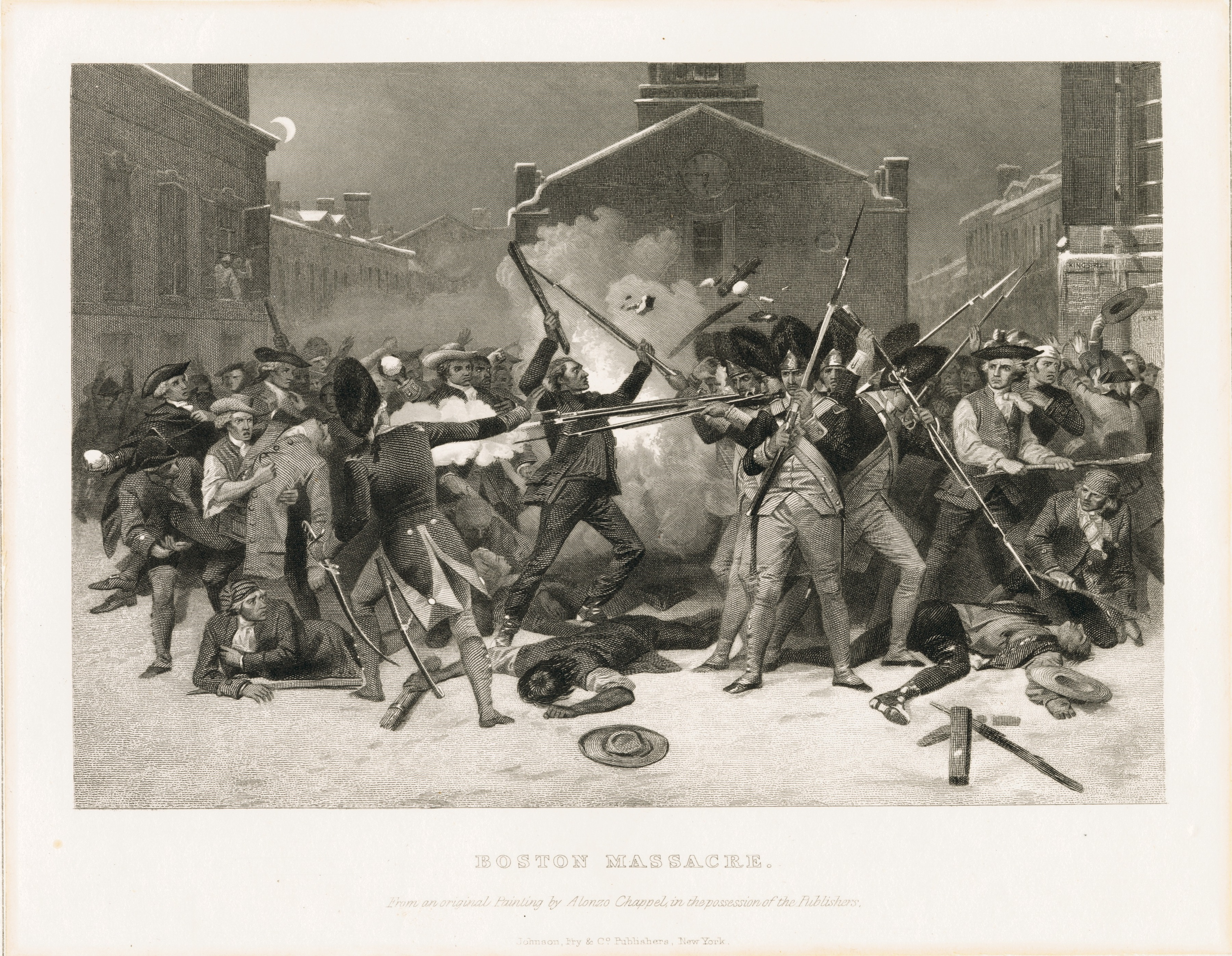

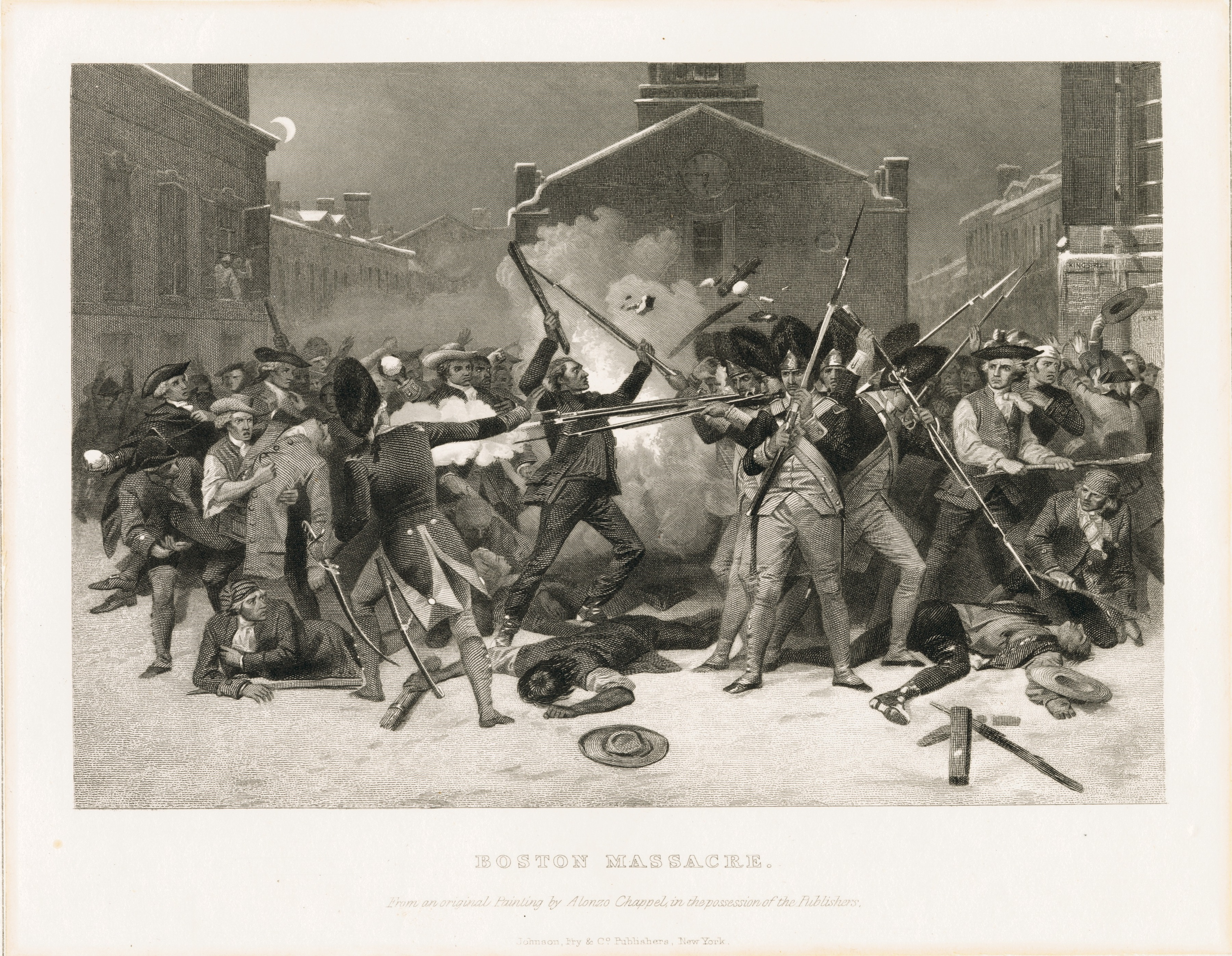

Counsel for the British: Boston Massacre

Britain's passage of the

Townshend Acts in 1767 revived tensions, and an increase in mob violence led the British to dispatch more troops to the colonies. On March 5, 1770, when a lone British sentry was accosted by a mob of men and boys, eight of his fellow

soldiers

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word , from Old French ...

reinforced him, and the crowd around them grew to several hundred. The soldiers were struck with snowballs, ice, and stones, and in the chaos the soldiers opened fire, killing five civilians, bringing about the infamous

Boston Massacre

The Boston Massacre (known in Great Britain as the Incident on King Street) was a confrontation in Boston on March 5, 1770, in which a group of nine British soldiers shot five people out of a crowd of three or four hundred who were harassing t ...

. The accused soldiers were arrested on charges of murder. When no other attorneys would come to their defense, Adams was impelled to do so despite the risk to his reputation – he believed no person should be denied the right to counsel and a fair trial. The trials were delayed so that passions could cool.

The week-long trial of the commander, Captain

Thomas Preston, began on October 24 and ended in his acquittal, because it was impossible to prove that he had ordered his soldiers to fire. The remaining soldiers were tried in December when Adams made his legendary argument regarding jury decisions: "Facts are stubborn things; and whatever may be our wishes, our inclinations, or the dictates of our passion, they cannot alter the state of facts and evidence." He added, "It is more important that innocence be protected than it is that guilt be punished, for guilt and crimes are so frequent in this world that they cannot all be punished. But if innocence itself is brought to the bar and condemned, perhaps to die, then the citizen will say, 'whether I do good or whether I do evil is immaterial, for innocence itself is no protection,' and if such an idea as that were to take hold in the mind of the citizen that would be the end of security whatsoever." Adams won an acquittal for six of the soldiers. Two, who had fired directly into the crowd, were convicted of manslaughter. Adams was paid a small sum by his clients.

According to biographer

John E. Ferling

John E. Ferling (born 1940) is a professor emeritus of history at the University of West Georgia. As a leading historian in the American Revolution and founding era, he has appeared in television documentaries on PBS, the History Channel, C-SPA ...

, during

jury selection

Jury selection is the selection of the people who will serve on a jury during a jury trial. The group of potential jurors (the "jury pool", also known as the ''venire'') is first selected from among the community using a reasonably random method. ...

Adams "expertly exercised his right to challenge individual jurors and contrived what amounted to a packed jury. Not only were several jurors closely tied through business arrangements to the British army, but five ultimately became Loyalist exiles." While Adams's defence was helped by a weak prosecution, he also "performed brilliantly." Ferling surmises that Adams was encouraged to take the case in exchange for political office; one of Boston's seats opened three months later in the

Massachusetts legislature, and Adams was the town's first choice to fill the vacancy.

The prosperity of his law practice increased from this exposure, as did the demands on his time. In 1771, Adams moved his family to Braintree but kept his office in Boston. He noted on the day of the family's move, "Now my family is away, I feel no Inclination at all, no Temptation, to be any where but at my Office. I am in it by 6 in the Morning – I am in it at 9 at night. ... In the Evening, I can be alone at my Office, and no where else." After some time in the capital, he became disenchanted with the rural and "vulgar" Braintree as a home for his family – in August 1772, he moved them back to Boston. He purchased a large brick house on

Queen Street, not far from his office. In 1774, Adams and Abigail returned the family to the farm due to the increasingly unstable situation in Boston, and Braintree remained their permanent Massachusetts home.

Becoming a revolutionary

Adams, who had been among the more conservative of the Founders, persistently held that while British actions against the colonies had been wrong and misguided, open insurrection was unwarranted and peaceful petition with the ultimate view of remaining part of Great Britain was a better alternative. His ideas began to change around 1772, as the British Crown assumed payment of the salaries of Governor

Thomas Hutchinson and his judges instead of the Massachusetts legislature. Adams wrote in the ''Gazette'' that these measures would destroy judicial independence and place the colonial government in closer subjugation to the Crown. After discontent among members of the legislature, Hutchinson delivered a speech warning that Parliament's powers over the colonies were absolute and that any resistance was illegal. Subsequently, John Adams, Samuel, and

Joseph Hawley drafted a resolution adopted by the

House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

threatening independence as an alternative to tyranny. The resolution argued that the colonists had never been under the sovereignty of Parliament. Their original charter, as well as their allegiance, was exclusive to the King.

The

Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell t ...

, a historic demonstration against the British

East India Company

The East India Company (EIC) was an English, and later British, joint-stock company founded in 1600 and dissolved in 1874. It was formed to trade in the Indian Ocean region, initially with the East Indies (the Indian subcontinent and Sou ...

's tea monopoly over American merchants, took place on December 16, 1773. The British schooner ''Dartmouth'', loaded with tea to be traded subject to the new

Tea Act

The Tea Act 1773 (13 Geo 3 c 44) was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain. The principal objective was to reduce the massive amount of tea held by the financially troubled British East India Company in its London warehouses and to help th ...

, had previously dropped anchor in Boston harbor. By 9:00 PM, the work of the protesters was done – they had demolished 342 chests of tea worth about ten thousand pounds. The ''Dartmouth'' owners briefly retained Adams as legal counsel regarding their liability for the destroyed shipment. Adams applauded the destruction of the tea, calling it the "grandest Event" in the history of the colonial protest movement, and writing in his diary that the dutied tea's destruction was an "absolutely and indispensably" necessary action.

Continental Congress

Member of Continental Congress

In 1774, at the instigation of John's cousin

Samuel Adams

Samuel Adams ( – October 2, 1803) was an American statesman, political philosopher, and a Founding Father of the United States. He was a politician in colonial Massachusetts, a leader of the movement that became the American Revolution, an ...

, the

First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Nav ...

was convened in response to the

Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measur ...

, a series of deeply unpopular measures intended to punish Massachusetts, centralize authority in Britain, and prevent rebellion in other colonies. Four delegates were chosen by the Massachusetts legislature, including John Adams, who agreed to attend, despite an emotional plea from his friend, Attorney General

Jonathan Sewall, not to.

Shortly after he arrived in Philadelphia, Adams was placed on the 23-member Grand Committee tasked with drafting a letter of grievances to

King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

. The members of the committee soon split into conservative and radical factions. Although the Massachusetts delegation was largely passive, Adams criticized conservatives such as

Joseph Galloway

Joseph Galloway (1731August 29, 1803) was an American attorney and a leading political figure in the events immediately preceding the founding of the United States in the late 1700s. As a staunch opponent of American independence, he would bec ...

,

James Duane

James Duane (February 6, 1733 – February 1, 1797) was an American Founding Father, attorney, jurist, and American Revolutionary leader from New York. He served as a delegate to the First Continental Congress, Second Continental Congress and ...

, and

Peter Oliver who advocated a conciliatory policy towards the British or felt that the colonies had a duty to remain loyal to Britain, although his views at the time did align with those of conservative

John Dickinson

John Dickinson (November 13 Julian_calendar">/nowiki>Julian_calendar_November_2.html" ;"title="Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar">/nowiki>Julian calendar November 2">Julian_calendar.html" ;"title="/nowiki>Julian calendar" ...

. Adams sought the repeal of objectionable policies, but at this early stage he continued to see benefits in maintaining the ties with Britain. He renewed his push for the right to a jury trial. He complained of what he considered the pretentiousness of the other delegates, writing to Abigail, "I believe if it was moved and seconded that We should come to a Resolution that Three and two make five We should be entertained with Logick and Rhetorick, Law, History, Politicks and Mathematicks, concerning the Subject for two whole Days, and then We should pass the Resolution unanimously in the Affirmative." Adams ultimately helped engineer a compromise between the conservatives and the radicals. The Congress disbanded in October after sending the final petition to the King and showing its displeasure with the Intolerable Acts by endorsing the

Suffolk Resolves.

Adams's absence from home was hard on Abigail, who was left alone to care for the family. She still encouraged her husband in his task, writing: "You cannot be, I know, nor do I wish to see you an inactive Spectator, but if the Sword be drawn I bid adieu to all domestick felicity, and look forward to that Country where there is neither wars nor rumors of War in a firm belief that thro the mercy of its King we shall both rejoice there together."

News of the opening hostilities with the British at the

Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord, ...

made Adams hope that independence would soon become a reality. Three days after the battle, he rode into a militia camp and, while reflecting positively on the high spirits of the men, was distressed by their poor condition and lack of discipline. A month later, Adams returned to Philadelphia for the

Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

as the leader of the Massachusetts delegation. He moved cautiously at first, noting that the Congress was divided between

Loyalists

Loyalism, in the United Kingdom, its overseas territories and its former colonies, refers to the allegiance to the British crown or the United Kingdom. In North America, the most common usage of the term refers to loyalty to the British Cro ...

, those favoring independence, and those hesitant to take any position. He became convinced that Congress was moving in the proper direction – away from Great Britain. Publicly, Adams supported "reconciliation if practicable," but privately agreed with

Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

's confidential observation that independence was inevitable.

In June 1775, with a view of promoting union among the colonies against Great Britain, he nominated

George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

of Virginia as commander-in-chief of the

army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

then assembled around Boston.

He praised Washington's "skill and experience" as well as his "excellent universal character." Adams opposed various attempts, including the

Olive Branch Petition

The Olive Branch Petition was adopted by the Second Continental Congress on July 5, 1775, and signed on July 8 in a final attempt to avoid war between Great Britain and the Thirteen Colonies in America. The Congress had already authorized the i ...

, aimed at trying to find peace between the colonies and Great Britain. Invoking the already-long list of British actions against the colonies, he wrote, "In my opinion Powder and Artillery are the most efficacious, Sure, and infallibly conciliatory Measures We can adopt." After his failure to prevent the petition from being enacted, he wrote a private letter derisively referring to Dickinson as a "piddling genius." The letter was intercepted and published in Loyalist newspapers. The well-respected Dickinson refused to greet Adams and he was for a time largely ostracized. Ferling writes, "By the fall of 1775 no one in Congress labored more ardently than Adams to hasten the day when America would be separate from Great Britain." In October 1775, Adams was appointed the chief judge of the Massachusetts Superior Court, but he never served, and resigned in February 1777.

In response to queries from other delegates, Adams wrote the 1776 pamphlet ''

Thoughts on Government

''Thoughts on Government'', or in full ''Thoughts on Government, Applicable to the Present State of the American Colonies'', was written by John Adams during the spring of 1776 in response to a resolution of the North Carolina Provincial Congress ...

'', which laid out an influential framework for republican constitutions.

Independence

Throughout the first half of 1776, Adams grew increasingly impatient with what he perceived to be the slow pace of declaring independence. He kept busy on the floor of the Congress, helping push through a plan to outfit armed ships to launch raids on enemy vessels. Later in the year, he drafted the first set of regulations to govern the provisional navy. Adams drafted the preamble to the

Lee Resolution

The Lee Resolution (also known as "The Resolution for Independence") was the formal assertion passed by the Second Continental Congress on July 2, 1776 which resolved that the Thirteen Colonies in America (at the time referred to as United Colo ...

of colleague

Richard Henry Lee

Richard Henry Lee (January 20, 1732June 19, 1794) was an American statesman and Founding Father from Virginia, best known for the June 1776 Lee Resolution, the motion in the Second Continental Congress calling for the colonies' independence f ...

. He developed a rapport with delegate

Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

of Virginia, who had been slower to support independence but by early 1776 agreed that it was necessary. On June 7, 1776, Adams

seconded the Lee Resolution, which stated that the colonies were "free and independent states."

Prior to independence being declared, Adams organized and selected a

Committee of Five

''

The Committee of Five of the Second Continental Congress was a group of five members who drafted and presented to the full Congress in Pennsylvania State House what would become the United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776. Thi ...

charged with drafting a

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of th ...

. He chose himself, Jefferson, Benjamin Franklin,

Robert R. Livingston

Robert Robert Livingston (November 27, 1746 (Old Style November 16) – February 26, 1813) was an American lawyer, politician, and diplomat from New York, as well as a Founding Father of the United States. He was known as "The Chancellor", afte ...

and

Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an American statesman, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign four of the great state papers of the United States related to the founding: the Con ...

. Jefferson thought Adams should write the document, but Adams persuaded the committee to choose Jefferson. Many years later, Adams recorded his exchange with Jefferson: Jefferson asked, "Why will you not? You ought to do it." To which Adams responded, "I will not – reasons enough." Jefferson replied, "What can be your reasons?" and Adams responded, "Reason first, you are a Virginian, and a Virginian ought to appear at the head of this business. Reason second, I am obnoxious, suspected, and unpopular. You are very much otherwise. Reason third, you can write ten times better than I can." "Well," said Jefferson, "if you are decided, I will do as well as I can." The Committee left no minutes, and the drafting process itself remains uncertain. Accounts written many years later by Jefferson and Adams, although frequently cited, are often contradictory. Although the first draft was written primarily by Jefferson, Adams assumed a major role in its completion. On July 1, the resolution was debated in Congress. It was expected to pass, but opponents such as Dickinson made a strong effort to oppose it anyhow. Jefferson, a poor debater, remained silent while Adams argued for its adoption. Many years later, Jefferson hailed Adams as "the pillar of

he Declaration'ssupport on the floor of Congress,

tsablest advocate and defender against the multifarious assaults it encountered." After editing the document further, Congress approved it on July 2. Twelve colonies voted in the affirmative, while New York abstained. Dickinson was absent. On July 3, Adams wrote to Abigail that "yesterday was decided the greatest question which was ever debated in America, and a greater perhaps never was nor will be decided among men." He predicted that "

e second day of July, 1776, will be the most memorable epoch in the history of America," and would be commemorated annually with great festivities.

During the congress, Adams sat on ninety committees, chairing twenty-five, an unmatched workload among the congressmen. As

Benjamin Rush

Benjamin Rush (April 19, 1813) was a Founding Father of the United States who signed the United States Declaration of Independence, and a civic leader in Philadelphia, where he was a physician, politician, social reformer, humanitarian, educa ...

reported, he was acknowledged "to be the first man in the House." In June 1776, Adams became head of the

Board of War and Ordnance

The Board of War, also known as the Board of War and Ordinance, was created by the Second Continental Congress as a special standing committee to oversee the American Continental Army's administration and to make recommendations regarding the ar ...

, charged with keeping an accurate record of the officers in the army and their ranks, the disposition of troops throughout the colonies, and ammunition. He was referred to as a "one man war department," working up to eighteen-hour days and mastering the details of raising, equipping and fielding an army under civilian control. As chairman of the Board, Adams functioned as a ''de facto'' Secretary of War. He kept extensive correspondences with a wide range of

Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

officers concerning supplies, munitions, and tactics. Adams emphasized to them the role of discipline in keeping an army orderly. He also authored the "Plan of Treaties," laying out the Congress's requirements for a treaty with France. He was worn out by the rigor of his duties and longed to return home. His finances were unsteady, and the money that he received as a delegate failed even to cover his own necessary expenses. However, the crisis caused by the defeat of the American soldiers kept him at his post.

After defeating the Continental Army at the

Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn, New Yor ...

on August 27, 1776, British Admiral

Richard Howe

Admiral of the Fleet Richard Howe, 1st Earl Howe, (8 March 1726 – 5 August 1799) was a British naval officer. After serving throughout the War of the Austrian Succession, he gained a reputation for his role in amphibious operations a ...

determined that a strategic advantage was at hand, and requested that Congress send representatives to negotiate peace. A delegation consisting of Adams, Franklin, and

Edward Rutledge

Edward Rutledge (November 23, 1749 – January 23, 1800) was an American Founding Father and politician who signed the Continental Association and was the youngest signatory of the Declaration of Independence. He later served as the 39th gov ...

met with Howe at the

Staten Island Peace Conference

The Staten Island Peace Conference was a brief informal diplomatic conference held between representatives of the British Crown and its rebellious North American colonies in the hope of bringing a rapid end to the nascent American Revolution. ...

on September 11. Howe's authority was premised on the states' submission, so the parties found no common ground. When Lord Howe stated he could view the American delegates only as British subjects, Adams replied, "Your lordship may consider me in what light you please, ... except that of a British subject." Adams learned many years later that his name was on a list of people specifically excluded from Howe's pardon-granting authority. Adams was unimpressed with Howe and predicted American success. He was able to return home to Braintree in October before leaving in January 1777 to resume his duties in Congress.

Diplomatic service

Commissioner to France

Adams advocated in Congress that independence was necessary to establish trade, and conversely, trade was essential for the attainment of independence; he specifically urged negotiation of a commercial treaty with

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. He was then appointed, along with Franklin, Dickinson,

Benjamin Harrison

Benjamin Harrison (August 20, 1833March 13, 1901) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 23rd president of the United States from 1889 to 1893. He was a member of the Harrison family of Virginia–a grandson of the ninth pr ...

of Virginia and Robert Morris of Pennsylvania, "to prepare a plan of treaties to be proposed to foreign powers." While Jefferson was laboring over the Declaration of Independence, Adams worked on the

Model Treaty. The Model Treaty authorized a commercial agreement with France but contained no provisions for formal recognition or military assistance. There were provisions for what constituted French territory. The treaty adhered to the provision that "

free ships make free goods," allowing neutral nations to trade reciprocally while exempting an agreed-upon list of contraband. By late 1777, America's finances were in tatters, and that September a British army had

defeated

Defeated may refer to:

* "Defeated" (Breaking Benjamin song)

* "Defeated" (Anastacia song)

*"Defeated", a song by Snoop Dogg from the album ''Bible of Love''

*Defeated, Tennessee, an unincorporated community

*''The Defeated

''The Defeated'', al ...

General Washington and captured Philadelphia. More Americans came to determine that mere commercial ties between the U.S. and France would not be enough, and that military assistance would be needed to end the war. The defeat of the British at

Saratoga was expected to help induce France to agree to an alliance.

In November 1777, Adams learned that he was to be named commissioner to France, replacing

Silas Deane

Silas Deane (September 23, 1789) was an American merchant, politician, and diplomat, and a supporter of American independence. Deane served as a delegate to the Continental Congress, where he signed the Continental Association, and then became the ...

and joining Franklin and

Arthur Lee in Paris to negotiate an alliance with the hesitant French.

James Lovell invoked Adams's "inflexible integrity" and the need to have a youthful man who could counterbalance Franklin's advanced age. On November 27, Adams accepted, wasting no time. He wrote to Lovell that he "should have wanted no motives or arguments" for his acceptance if he "could be sure that the public would be benefited by it." Abigail was left in Massachusetts to manage their home, but it was agreed that 10-year-old John Quincy would go with Adams, for the experience was "of inestimable value" to his maturation. On February 17, 1778, Adams set sail aboard the frigate ''

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

'', commanded by Captain

Samuel Tucker. The trip was stormy and treacherous. Lightning injured 19 sailors and killed one. The ship was pursued by several British vessels, with Adams taking up arms to help capture one. A cannon malfunction killed one of the crew and injured five others. On April 1, the ''Boston'' arrived in France, where Adams learned that France had agreed to an

alliance

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

with the United States on February 6. Adams was annoyed by the other two commissioners: Lee, whom he thought paranoid and cynical, and the popular and influential Franklin, whom he found lethargic and overly deferential and accommodating to the French. He assumed a less visible role but helped manage the delegation's finances and record-keeping. Frustrated by the perceived lack of commitment on the part of the French, Adams wrote a letter to French foreign minister

Vergennes in December, arguing for French naval support in North America. Franklin toned down the letter, but Vergennes still ignored it. In September 1778, Congress increased Franklin's powers by naming him

minister plenipotentiary

An envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary, usually known as a minister, was a diplomatic head of mission who was ranked below ambassador. A diplomatic mission headed by an envoy was known as a legation rather than an embassy. Under the ...

to France while Lee was sent to Spain. Adams received no instructions. Frustrated by the apparent slight, he departed France with his son John Quincy on March 8, 1779. On August 2, they arrived in Braintree.

In late 1779, Adams was appointed as the sole minister charged with negotiations to establish a commercial treaty with Britain and end the war. Following the conclusion of the Massachusetts constitutional convention, he departed for France in November aboard the French frigate ''Sensible'' – accompanied by his sons John Quincy and 9-year-old Charles. A leak in the ship forced it to land in

Ferrol, Spain

Ferrol () is a city in the Province of A Coruña in Galicia, on the Atlantic coast in north-western Spain, in the vicinity of Strabo's Cape Nerium (modern day Cape Prior). According to the 2021 census, the city has a population of 64,785, ma ...

, and Adams and his party spent six weeks travelling overland until they reached Paris. Constant disagreement between Lee and Franklin eventually resulted in Adams assuming the role of tie-breaker in almost all votes on commission business. He increased his usefulness by mastering the French language. Lee was eventually recalled. Adams closely supervised his sons' education while writing to Abigail about once every ten days.

In contrast to Franklin, Adams viewed the Franco-American alliance pessimistically. The French, he believed, were involved for their own self-interest, and he grew frustrated by what he saw as their sluggishness in providing substantial aid to the Revolution. The French, Adams wrote, meant to keep their hands "above our chin to prevent us from drowning, but not to lift our heads out of water." In March 1780, Congress, trying to curb inflation, voted to devalue the dollar. Vergennes summoned Adams for a meeting. In a letter sent in June, he insisted that any fluctuation of the dollar value without an exception for French merchants was unacceptable and requested that Adams write to Congress asking it to "retrace its steps." Adams bluntly defended the decision, not only claiming that the French merchants were doing better than Vergennes implied but voicing other grievances he had with the French. The alliance had been made over two years before. During that period, an army under the

comte de Rochambeau

Marshal Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, 1 July 1725 – 10 May 1807, was a French nobleman and general whose army played the decisive role in helping the United States defeat the British army at Yorktown in 1781 during the ...

had been sent to assist Washington, but it had yet to do anything of significance and America was expecting French warships. These were needed, Adams wrote, to contain the British armies in the port cities and contend with the powerful British Navy. However, the French Navy had been sent not to the United States but to the West Indies to protect French interests there. France, Adams believed, needed to commit itself more fully to the alliance. Vergennes responded that he would deal only with Franklin, who sent a letter back to Congress critical of Adams. Adams then left France of his own accord.

Ambassador to the Dutch Republic

In mid-1780, Adams traveled to the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

. One of the few other existing republics at the time, Adams thought it might be sympathetic to the American cause. Securing a Dutch loan could increase American independence from France and pressure Britain into peace. At first, Adams had no official status, but in July he was formally given permission to negotiate for a loan and took up residence in

Amsterdam

Amsterdam ( , , , lit. ''The Dam on the River Amstel'') is the capital and most populous city of the Netherlands, with The Hague being the seat of government. It has a population of 907,976 within the city proper, 1,558,755 in the urban ar ...

in August. Adams was originally optimistic and greatly enjoyed the city, but soon became disappointed. The Dutch, fearing British retaliation, refused to meet Adams. Before he had arrived, the British found out about secret aid the Dutch had sent to the Americans, the British authorized reprisals against their ships, which only increased their apprehension. Word had also reached Europe of American battlefield defeats. After five months of not meeting with a single Dutch official, Adams in early 1781 pronounced Amsterdam "the capital of the reign of

Mammon." He was finally invited to present his credentials as ambassador to the Dutch government at

The Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital o ...

on April 19, 1781, but they did not promise any assistance. In the meantime, Adams thwarted an attempt by neutral European powers to mediate the war without consulting the United States. In July, Adams consented to the departure of both of his sons; John Quincy went with Adams's secretary

Francis Dana to

Saint Petersburg

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

as a

French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

interpreter, in an effort to seek recognition from

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and Northern Asia. It is the largest country in the world, with its internationally recognised territory covering , and encompassing one-ei ...

, and a homesick Charles returned home with Adams's friend

Benjamin Waterhouse

Benjamin Waterhouse (March 4, 1754, Newport, Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations – October 2, 1846, Cambridge, Massachusetts) was a physician, co-founder and professor of Harvard Medical School. He is most well known for being ...

. In August, shortly after being removed from his position of sole head of peace treaty negotiations, Adams fell seriously ill in "a major nervous breakdown." That November, he learned that American and French troops had decisively defeated the British at

Yorktown. The victory was in large part due to the assistance of the French Navy, which vindicated Adams's stand for increased naval assistance.

News of the American triumph at Yorktown convulsed Europe. In January 1782, after recovering, Adams arrived at The Hague to demand that the

States General of the Netherlands

The States General of the Netherlands ( nl, Staten-Generaal ) is the supreme bicameral legislature of the Netherlands consisting of the Senate () and the House of Representatives (). Both chambers meet at the Binnenhof in The Hague.

The State ...

answer his petitions. His efforts stalled, and he took his cause to the people, successfully capitalizing on popular pro-American sentiment to push the States General towards recognizing the U.S. Several provinces began recognizing American independence. On April 19, the States General in The Hague formally recognized American independence and acknowledged Adams as ambassador. On June 11, with the aid of the Dutch

''Patriotten'' leader

Joan van der Capellen tot den Pol, Adams negotiated a loan of five million guilders. In October, he negotiated with the Dutch a treaty of amity and commerce. The house that Adams bought during this stay in the

Netherlands

)

, anthem = ( en, "William of Nassau")

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, subdivision_type = Sovereign state

, subdivision_name = Kingdom of the Netherlands

, established_title = Before independence

, established_date = Spanish Netherl ...

became the first American embassy on foreign soil.

Treaty of Paris

After negotiating the loan with the Dutch, Adams was re-appointed as the American commissioner to negotiate the war-ending treaty, the

Treaty of Paris. Vergennes and France's minister to the United States,

Anne-César de La Luzerne

Anne-César de La Luzerne (15 July 1741 – 14 September 1791) was an 18th-century French soldier and diplomat who had an influential role to the Continental Congress and new government of the United States of America after it gained independence ...

, disapproved of Adams, so Franklin, Thomas Jefferson,

John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the f ...

, and

Henry Laurens were appointed to collaborate with Adams, although Jefferson did not initially go to Europe and Laurens was posted to the Dutch Republic following his imprisonment in the Tower of London.

In the final negotiations, securing fishing rights off

Newfoundland

Newfoundland and Labrador (; french: Terre-Neuve-et-Labrador; frequently abbreviated as NL) is the easternmost province of Canada, in the country's Atlantic region. The province comprises the island of Newfoundland and the continental region ...

and

Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

proved both very important and very difficult. In response to very strict restrictions proposed by the British, Adams insisted that not only should American fishermen be allowed to travel as close to shore as desired, but that they should be allowed to cure their fish on the shores of Newfoundland. This, and other statements, prompted Vergennes to secretly inform the British that France did not feel compelled to "sustain

hesepretentious ambitions." Overruling Franklin and distrustful of Vergennes, Jay and Adams decided not to consult with France, instead dealing directly with the British. During these negotiations, Adams mentioned to the British that his proposed fishing terms were more generous than those offered by France in 1778 and that accepting would foster goodwill between Britain and the United States while putting pressure on France. Britain agreed, and the two sides worked out other provisions afterward. Vergennes was angered when he learned from Franklin of the American duplicity, but did not demand renegotiation. He was surprised at how much the Americans could extract. The independent negotiations allowed the French to plead innocence to their Spanish allies, whose demands for

Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = "Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gibr ...

might have caused significant problems. On September 3, 1783, the treaty was signed and American independence was recognized.

Ambassador to Great Britain

Adams was appointed the first

American ambassador to Great Britain in 1785. After arriving in London from Paris, Adams had his first audience with

King George III

George III (George William Frederick; 4 June 173829 January 1820) was King of Great Britain and of Ireland from 25 October 1760 until the union of the two kingdoms on 1 January 1801, after which he was King of the United Kingdom of Great B ...

on June 1, which he meticulously recorded in a letter to Foreign Minister Jay the next day. The pair's exchange was respectful; Adams promised to do all that he could to restore friendship and cordiality "between People who, tho by an Ocean and under different Governments have the Same Language, a Similar Religion and kindred Blood," and the King agreed to "receive with Pleasure, the Assurances of the friendly Dispositions of the United States." The King added that although "he had been the last to consent" to American independence, he wanted Adams to know that he had always done what he thought was right. Towards its end, he startled Adams by commenting that "There is an Opinion, among Some People, that you are not the most attached of all Your Countrymen, to the manners of France." Adams replied, "That Opinion sir, is not mistaken, I must avow to your Majesty, I have no Attachments but to my own Country." To this King George responded, "An honest Man will never have any other."

Adams was joined by Abigail while in London. Suffering the hostility of the King's courtiers, they escaped when they could by seeking out

Richard Price

Richard Price (23 February 1723 – 19 April 1791) was a British moral philosopher, Nonconformist minister and mathematician. He was also a political reformer, pamphleteer, active in radical, republican, and liberal causes such as the French ...

, minister of

Newington Green Unitarian Church and instigator of the

debate over the Revolution within Britain. Adams corresponded with his sons John Quincy and Charles, both of whom were at Harvard, cautioning the former against the "smell of the midnight lamp" while admonishing the latter to devote sufficient time to study. Jefferson visited Adams in 1786 while serving as Minister to France; the two toured the countryside and saw many British historical sites. While in London, Adams met his old friend

Jonathan Sewall, but the two discovered that they had grown too far apart to renew their friendship. Adams considered Sewall one of the war's casualties, and Sewall critiqued him as an ambassador:

While in London Adams wrote his three-volume ''

''. It was a response to those he had met in Europe who criticized the government systems of the American states.

Adams's tenure in Britain was complicated by both countries failing to follow their treaty obligations. The American states had been delinquent in paying debts owed to British merchants, and in response, the British refused to vacate forts in the northwest as promised. Adams's attempts to resolve this dispute failed, and he was often frustrated by a lack of news of progress from home. The news he received of tumult at home, such as

Shays' Rebellion

Shays Rebellion was an armed uprising in Western Massachusetts and Worcester in response to a debt crisis among the citizenry and in opposition to the state government's increased efforts to collect taxes both on individuals and their trades. T ...

, heightened his anxiety. He then asked Jay to be relieved; in 1788, he took his leave of George III, who engaged Adams in polite and formal conversation, promising to uphold his end of the treaty once America did the same. Adams then went to The Hague to take formal leave of his ambassadorship there and to secure refinancing from the Dutch, allowing the United States to meet obligations on earlier loans.

Vice presidency (1789–1797)

Election

On June 17, 1788, Adams arrived back in Massachusetts to a triumphant welcome. He returned to farming life in the months after. The nation's first

presidential election

A presidential election is the election of any head of state whose official title is President.

Elections by country

Albania

The president of Albania is elected by the Assembly of Albania who are elected by the Albanian public.

Chile

The p ...

was soon to take place. Because George Washington was widely expected to win the presidency, many felt that the vice presidency should go to a northerner. Although he made no public comments on the matter, Adams was the primary contender. Each state's

presidential electors gathered on February 4, 1789, to cast their

two votes for the president. The person with the most votes would be president and the second would become vice president. Adams received 34

electoral college votes in the election, second place behind Washington, who was a unanimous choice with 69 votes. As a result, Washington became the nation's

first president, and Adams became its first

vice president

A vice president, also director in British English, is an officer in government or business who is below the president (chief executive officer) in rank. It can also refer to executive vice presidents, signifying that the vice president is on ...

. Adams finished well ahead of all others except Washington, but was still offended by Washington receiving more than twice as many votes. In an effort to ensure that Adams did not accidentally become president and that Washington would have an overwhelming victory,

Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charle ...

convinced at least 7 of the 69 electors not to cast their vote for Adams. After finding out about the manipulation but not Hamilton's role in it, Adams wrote to Benjamin Rush that his election was "a curse rather than a blessing,"

Although his term started on March 4, 1789, Adams did not begin serving as Vice President of the United States until April 21, because he did not arrive in New York in time.

Tenure

The sole constitutionally prescribed responsibility of the vice president is to preside over the

Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

, where he can cast a tie-breaking vote.