The Jewish exodus from the Muslim world was the departure, flight,

expulsion

Expulsion or expelled may refer to:

General

* Deportation

* Ejection (sports)

* Eviction

* Exile

* Expeller pressing

* Expulsion (education)

* Expulsion from the United States Congress

* Extradition

* Forced migration

* Ostracism

* Persona non ...

,

evacuation and

migration

Migration, migratory, or migrate may refer to: Human migration

* Human migration, physical movement by humans from one region to another

** International migration, when peoples cross state boundaries and stay in the host state for some minimum le ...

of around 900,000 Jews from

Arab countries

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western As ...

and

Iran

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, mainly from 1948 to the early 1970s, though with one final

exodus from Iran in 1979–80 following the

Iranian Revolution

The Iranian Revolution ( fa, انقلاب ایران, Enqelâb-e Irân, ), also known as the Islamic Revolution ( fa, انقلاب اسلامی, Enqelâb-e Eslâmī), was a series of events that culminated in the overthrow of the Pahlavi dynas ...

. An estimated 650,000 of the departees settled in

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

.

A number of small-scale Jewish migrations began in many Middle Eastern countries early in the 20th century with the only substantial

aliyah (immigration to the area today known as

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

) coming from Yemen and Syria. Few Jews from Muslim countries immigrated during the period of

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

. Prior to the

creation of Israel in 1948, approximately 800,000 Jews were living in lands that now make up the

Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

. Of these, just under two-thirds lived in French- and Italian-controlled

North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, 15–20% in the

Kingdom of Iraq, approximately 10% in the

Kingdom of Egypt

The Kingdom of Egypt ( ar, المملكة المصرية, Al-Mamlaka Al-Miṣreyya, The Egyptian Kingdom) was the legal form of the Egyptian state during the latter period of the Muhammad Ali dynasty's reign, from the United Kingdom's recog ...

and approximately 7% in the

Kingdom of Yemen

The Mutawakkilite Kingdom of Yemen ( ar, المملكة المتوكلية اليمنية '), also known as the Kingdom of Yemen or simply as Yemen, or, retrospectively, as North Yemen, was a state that existed between 1918 and 1962 in the nor ...

. A further 200,000 lived in

Pahlavi Iran and the

Republic of Turkey.

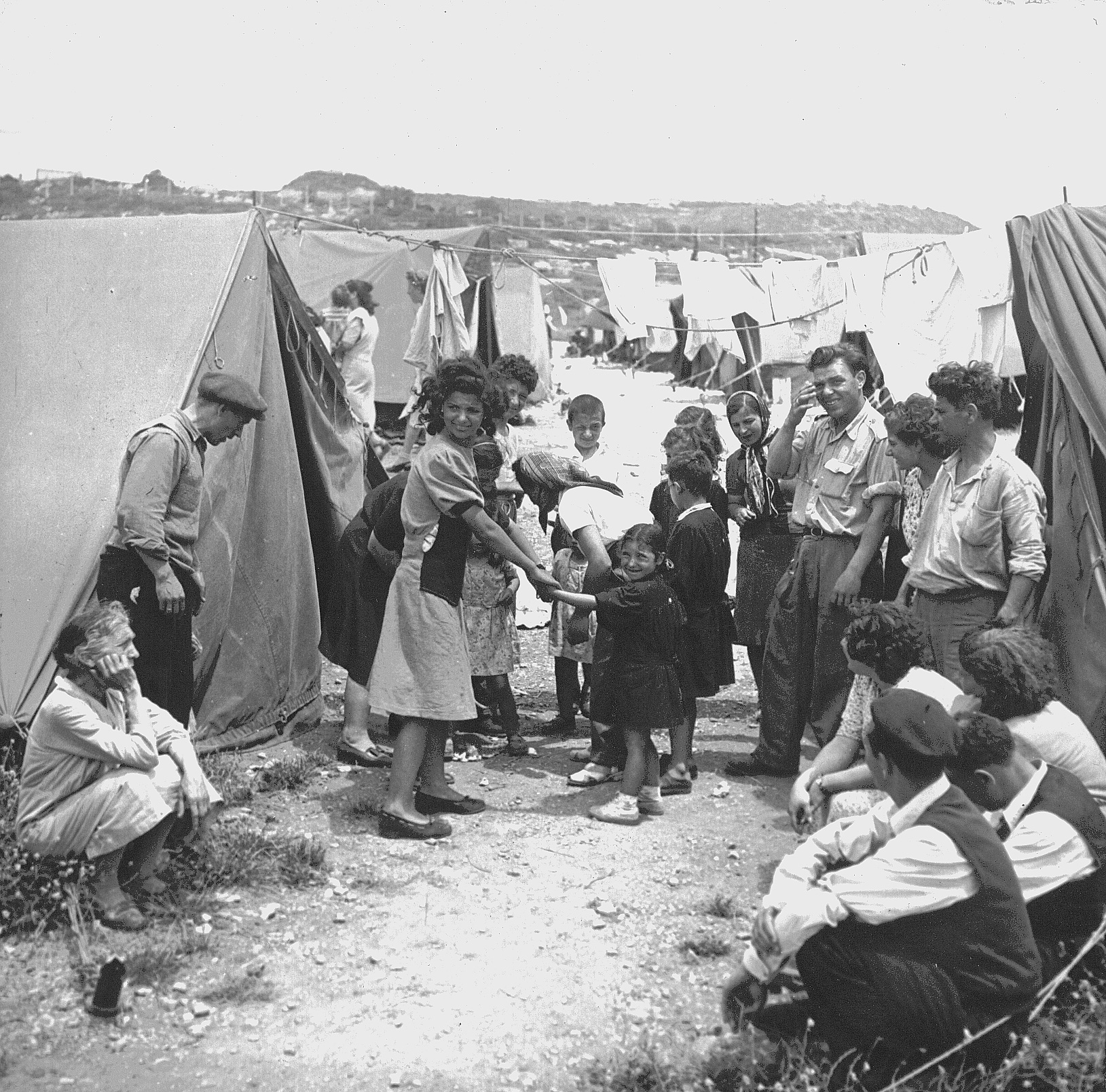

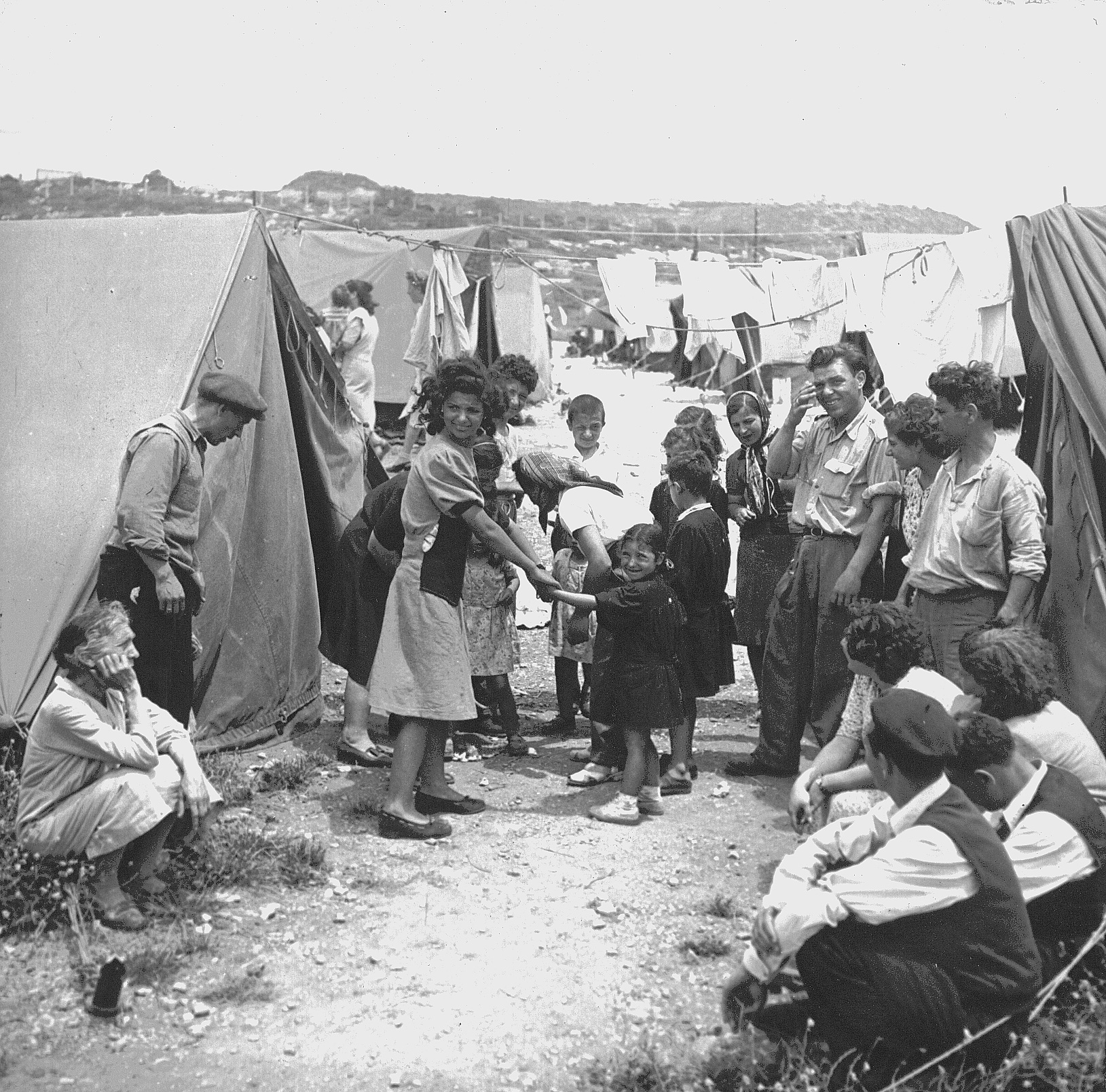

The first large-scale exoduses took place in the late 1940s and early 1950s, primarily from Iraq, Yemen and Libya. In these cases over 90% of the Jewish population left, despite the necessity of leaving their property behind. Two hundred and sixty thousand Jews from Arab countries immigrated to

Israel

Israel (; he, יִשְׂרָאֵל, ; ar, إِسْرَائِيل, ), officially the State of Israel ( he, מְדִינַת יִשְׂרָאֵל, label=none, translit=Medīnat Yīsrāʾēl; ), is a country in Western Asia. It is situated ...

between 1948 and 1951, accounting for 56% of the total immigration to the newly founded state.

[ The Israeli government's policy to accommodate 600,000 immigrants over four years, doubling the existing Jewish population,][

Later waves peaked at different times in different regions over the subsequent decades. The peak of the exodus from Egypt occurred in 1956 following the ]Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

. The emigrations from the other North African Arab countries peaked in the 1960s. Lebanon was the only Arab country to see a temporary increase in its Jewish population during this period, due to an influx of Jews from other Arab countries, although by the mid-1970s the Jewish community of Lebanon had also dwindled. Six hundred thousand Jews from Arab and Muslim countries had reached Israel by 1972.[Malka Hillel Shulewitz, ''The Forgotten Millions: The Modern Jewish Exodus from Arab Lands'', Continuum 2001, pp. 139 and 155.][Ada Aharon]

"The Forced Migration of Jews from Arab Countries

, Historical Society of Jews from Egypt website. Accessed 1 February 2009.Mizrahi Jews

Mizrahi Jews ( he, יהודי המִזְרָח), also known as ''Mizrahim'' () or ''Mizrachi'' () and alternatively referred to as Oriental Jews or ''Edot HaMizrach'' (, ), are a grouping of Jewish communities comprising those who remained ...

("Oriental," literally: "Eastern Jews") and Sephardic Jews ("Spanish Jews"), currently constitute more than half of the total population of Israel, partially as a result of their higher fertility rate

The total fertility rate (TFR) of a population is the average number of children that would be born to a woman over her lifetime if:

# she were to experience the exact current age-specific fertility rates (ASFRs) through her lifetime

# she were t ...

. In 2009, only 26,000 Jews remained in Arab countries and Iran, as well as 26,000 in Turkey

Turkey ( tr, Türkiye ), officially the Republic of Türkiye ( tr, Türkiye Cumhuriyeti, links=no ), is a list of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country located mainly on the Anatolia, Anatolian Peninsula in Western Asia, with ...

.pull factors

Human migration is the movement of people from one place to another with intentions of settling, permanently or temporarily, at a new location (geographic region). The movement often occurs over long distances and from one country to another (ex ...

, such as the desire to fulfill Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

yearnings or find a better economic status and a secure home in Europe or the Americas and, in Israel, a policy change in favour of mass immigration focused on Jews from Arab and Muslim countries, together with push factors, such as persecution

Persecution is the systematic mistreatment of an individual or group by another individual or group. The most common forms are religious persecution, racism, and political persecution, though there is naturally some overlap between these term ...

/ antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, political instability,[: "... economic straits as their traditional role was whittled away, famine, disease, growing political persecution and increased public hostility, the state of anarchy after the murder of Yahya, a desire to be reunited with family members, incitement and encouragement to leave from ionist agents whoplayed on their religious sensibilities, promises that their passage would be paid to Israel and that their material difficulties would be cared for by the Jewish state, a sense that the Land of Israel was a veritable Eldorado, a sense of history being fulfilled, a fear of missing the boat, a sense that living wretchedly as dhimmis in an Islamic state was no longer God-ordained, a sense that as a people they had been flayed by history long enough: all these played a role. ... Purely religious, messianic sentiment too, had its part but by and large this has been overemphasised."] poverty[ and expulsion. The history of the exodus has been politicized, given its proposed relevance to the historical narrative of the ]Arab–Israeli conflict

The Arab–Israeli conflict is an ongoing intercommunal phenomenon involving political tension, military conflicts, and other disputes between Arab countries and Israel, which escalated during the 20th century, but had mostly faded out by the ...

.

–

–

Background

At the time of the Muslim conquests

The early Muslim conquests or early Islamic conquests ( ar, الْفُتُوحَاتُ الإسْلَامِيَّة, ), also referred to as the Arab conquests, were initiated in the 7th century by Muhammad, the main Islamic prophet. He estab ...

of the 7th century, ancient Jewish communities had existed in many parts of the Middle East and North Africa since Antiquity. Jews under Islamic rule were given the status of dhimmi

' ( ar, ذمي ', , collectively ''/'' "the people of the covenant") or () is a historical term for non-Muslims living in an Islamic state with legal protection. The word literally means "protected person", referring to the state's obligatio ...

, along with certain other pre-Islamic religious groups. As such, these groups were accorded certain rights as "People of the Book

People of the Book or Ahl al-kitāb ( ar, أهل الكتاب) is an Islamic term referring to those religions which Muslims regard as having been guided by previous revelations, generally in the form of a scripture. In the Quran they are ident ...

".

During waves of persecution in Medieval Europe, many Jews found refuge in Muslim lands, though in other times and places, Jews fled persecution in Muslim lands and found refuge in Christian lands. Jews expelled from the Iberian Peninsula were invited to settle in various parts of the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, where they would often form a prosperous model minority

A model minority is a minority demographic (whether based on ethnicity, race or religion) whose members are perceived as achieving a higher degree of socioeconomic success than the population average, thus serving as a reference group to outgro ...

of merchants acting as intermediaries for their Muslim rulers.

North Africa region

French colonization

In the 19th century, Francization

Francization (in American English, Canadian English, and Oxford English) or Francisation (in other British English), Frenchification, or Gallicization is the expansion of French language use—either through willful adoption or coercion—by more ...

of Jews in the French colonial North Africa

North Africa, or Northern Africa is a region encompassing the northern portion of the African continent. There is no singularly accepted scope for the region, and it is sometimes defined as stretching from the Atlantic shores of Mauritania in ...

, due to the work of organizations such as the Alliance Israelite Universelle

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

and French policies such as the Algerian citizenship decree of 1870, resulted in a separation of the community from the local Muslims.

The French began the conquest of Algeria in 1830. The following century had a profound influence on the status of the Algerian Jews; following the 1870 "Décret Crémieux", they were elevated from the protected minority dhimmi status to French citizens of the colonial power. The decree began a wave of Pied-Noir

The ''Pieds-Noirs'' (; ; ''Pied-Noir''), are the people of French people, French and other White Africans of European ancestry, European descent who were born in Algeria during the French Algeria, period of French rule from 1830 to 1962; the v ...

-led anti-Jewish protests (such as the 1897 anti-Jewish riots in Oran

Oran ( ar, وَهران, Wahrān) is a major coastal city located in the north-west of Algeria. It is considered the second most important city of Algeria after the capital Algiers, due to its population and commercial, industrial, and cultural ...

), which the Muslim community did not participate in, to the disappointment of the European agitators. Though there were also cases of Muslim-led anti-Jewish riots, such as in Constantine

Constantine most often refers to:

* Constantine the Great, Roman emperor from 306 to 337, also known as Constantine I

*Constantine, Algeria, a city in Algeria

Constantine may also refer to:

People

* Constantine (name), a masculine given name ...

in 1934 when 34 Jews were killed.

Neighbouring Husainid Tunisia began to come under European influence in the late 1860s and became a French protectorate in 1881. Since the 1837 accession of Ahmed Bey

Ahmad ( ar, أحمد, ʾAḥmad) is an Arabic male given name common in most parts of the Muslim world. Other spellings of the name include Ahmed and Ahmet.

Etymology

The word derives from the root (ḥ-m-d), from the Arabic (), from the ve ...

, and continued by his successor Muhammed Bey, Tunisia's Jews were elevated within Tunisia society with improved freedom and security, which was confirmed and safeguarded during the French protectorate." Around a third of Tunisian Jews took French citizenship during the protectorate.

Morocco, which had remained independent during the 19th century, became a French protectorate in 1912. However, during less than half a century of colonization, the equilibrium between Jews and Muslims in Morocco was upset, and the Jewish community was again positioned between the colonisers and the Muslim majority. French penetration into Morocco between 1906 and 1912 created significant Morocco Muslim resentment, resulting in nationwide protests and military unrest. During the period a number of anti-European or anti-French protests extended to include anti-Jewish manifestations, such as in Casablanca

Casablanca, also known in Arabic as Dar al-Bayda ( ar, الدَّار الْبَيْضَاء, al-Dār al-Bayḍāʾ, ; ber, ⴹⴹⴰⵕⵍⴱⵉⴹⴰ, ḍḍaṛlbiḍa, : "White House") is the largest city in Morocco and the country's econom ...

, Oujda

Oujda ( ar, وجدة; ber, ⵡⵓⵊⴷⴰ, Wujda) is a major Moroccan city in its northeast near the border with Algeria. Oujda is the capital city of the Oriental region of northeastern Morocco and has a population of about 558,000 people. It ...

and Fes

Fez or Fes (; ar, فاس, fās; zgh, ⴼⵉⵣⴰⵣ, fizaz; french: Fès) is a city in northern inland Morocco and the capital of the Fès-Meknès administrative region. It is the second largest city in Morocco, with a population of 1.11 mi ...

in 1907-08 and later in the 1912 Fes riots

The Fes Riots, also known as the Fes Uprising or Mutiny (from , '), the Tritl (, among the Jewish community) and the Bloody Days of Fes (from ) were riots which started April 17, 1912 in Fes, the then-capital of Morocco, when French officers ann ...

.

The situation in colonial Libya was similar; as for the French in the other North African countries, the Italian influence in Libya was welcomed by the Jewish community, increasing their separation from the non-Jewish Libyans.

The Alliance Israelite Universelle, founded in France in 1860, set up schools in Algeria, Morocco and Tunisia as early as 1863.

World War II

During World War II, Morocco, Algeria, Tunisia and Libya came under Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

or Vichy French

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

occupation and their Jews were subject to various forms of persecution. In Libya, the Axis powers established labor camps

A labor camp (or labour camp, see spelling differences) or work camp is a detention facility where inmates are forced to engage in penal labor as a form of punishment. Labor camps have many common aspects with slavery and with prisons (espec ...

to which many Jews were forcibly deported.[History of the Jewish Community in Libya]

. Retrieved 1 July 2006 In other areas Nazi propaganda

The propaganda used by the German Nazi Party in the years leading up to and during Adolf Hitler's dictatorship of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 to 1945 was a crucial instrument for acquiring and maintaining power, and for the implementation o ...

targeted Arab populations to incite them against British or French rule. National Socialist propaganda contributed to the transfer of racial antisemitism

Racial antisemitism is prejudice against Jews based on a belief or assertion that Jews constitute a distinct race that has inherent traits or characteristics that appear in some way abhorrent or inherently inferior or otherwise different from ...

to the Arab world and is likely to have unsettled Jewish communities. An anti-Jewish riot took place in Casablanca in 1942 in the wake of Operation Torch, where a local mob attacked the Jewish mellah

A ''mellah'' ( or 'saline area'; and he, מלאח) is a Jewish quarter of a city in Morocco. Starting in the 15th century and especially since the beginning of the 19th century, Jewish communities in Morocco were constrained to live in ''mellah'' ...

. (''Mellah'' is the Moroccan name for a Jewish ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

.) However, according to the Hebrew University of Jerusalem

The Hebrew University of Jerusalem (HUJI; he, הַאוּנִיבֶרְסִיטָה הַעִבְרִית בִּירוּשָׁלַיִם) is a public research university based in Jerusalem, Israel. Co-founded by Albert Einstein and Dr. Chaim Weiz ...

's Dr. Haim Saadon, "Relatively good ties between Jews and Muslims in North Africa during World War II stand in stark contrast to the treatment of their co-religionists by gentiles in Europe."["Jewish-Muslim ties in Maghreb were good despite Nazis" by Gil Shefler]

24 January 2011, ''The Jerusalem Post

''The Jerusalem Post'' is a broadsheet newspaper based in Jerusalem, founded in 1932 during the British Mandate of Palestine by Gershon Agron as ''The Palestine Post''. In 1950, it changed its name to ''The Jerusalem Post''. In 2004, the paper w ...

''

From 1943 until the mid-1960s, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee

American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, also known as Joint or JDC, is a Jewish relief organization based in New York City. Since 1914 the organisation has supported Jewish people living in Israel and throughout the world. The organization i ...

was an important foreign organization driving change and modernization in the North African Jewish community.[

]

Morocco

As in Tunisia and Algeria,

As in Tunisia and Algeria, Moroccan Jews

Moroccan Jews ( ar, اليهود المغاربة, al-Yahūd al-Maghāriba he, יהודים מרוקאים, Yehudim Maroka'im) are Jews who live in or are from Morocco. Moroccan Jews constitute an ancient community dating to Roman times. Jews b ...

did not face large scale expulsion or outright asset confiscation or any similar government persecution during the period of exile, and Zionist agents were relatively allowed freedom of action to encourage emigration.[: "... the policies adopted by Nasser's Egypt or Syria such as internment in prison camps, sequestration, or even outright confiscation of assets, and large-scale expulsions (as was the case with Egyptian Jews in 1956-57), were never implemented by Muhammad V, Hasan II, Bourguiba, or the FLN. The freedom of action granted in Algeria, Morocco (since 1961), and Tunisia to Jewish emigration societies... was unparalleled elsewhere in the Arab world. These organizations enjoyed greater legality than government opponents who were Muslims ... albeit managed by foreigners and financed from abroad."]

In Morocco the Vichy regime during World War II passed discriminatory laws against Jews; for example, Jews were no longer able to get any form of credit, Jews who had homes or businesses in European neighborhoods were expelled, and quotas were imposed limiting the percentage of Jews allowed to practice professions such as law and medicine to no more than two percent. King Mohammed V expressed his personal distaste for these laws, assuring Moroccan Jewish leaders that he would never lay a hand "upon either their persons or property". While there is no concrete evidence of him actually taking any actions to defend Morocco's Jews, it has been argued that he may have worked on their behalf behind the scenes.

In June 1948, soon after Israel was established and in the midst of the first Arab–Israeli war, violent anti-Jewish riots broke out in Oujda and Djerada

Jerada (Berber: Jrada, ⵊⵔⴰⴷⴰ, Arabic: جْرادة) is a city in the Oriental region of northeastern Morocco. It is located close to the border with Algeria

)

, image_map = Algeria (centered orthographic projection).svg ...

, leading to deaths of 44 Jews. In 1948–49, after the massacres, 18,000 Moroccan Jews left the country for Israel. Later, however, Jewish migration from Morocco slowed to a few thousand a year. Through the early 1950s, Zionist

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after '' Zion'') is a nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is known in Je ...

organizations encouraged immigration, particularly in the poorer south of the country, seeing Moroccan Jews as valuable contributors to the Jewish State:

Incidents of anti-Jewish violence continued through the 1950s, although French officials later stated that Moroccan Jews "had suffered comparatively fewer troubles than the wider European population" during the struggle for independence. In August 1953, riots broke out in the city of Oujda and resulted in the death of 4 Jews including an 11-year-old girl.

Incidents of anti-Jewish violence continued through the 1950s, although French officials later stated that Moroccan Jews "had suffered comparatively fewer troubles than the wider European population" during the struggle for independence. In August 1953, riots broke out in the city of Oujda and resulted in the death of 4 Jews including an 11-year-old girl.[Jews Killed in Morocco Riots; Raid on Jewish Quarter Repulsed]

JTA, 24 August 1953. In the same month French security forces prevented a mob from breaking into the Jewish Mellah of Rabat

Rabat (, also , ; ar, الرِّبَاط, er-Ribât; ber, ⵕⵕⴱⴰⵟ, ṛṛbaṭ) is the capital city of Morocco and the country's seventh largest city with an urban population of approximately 580,000 (2014) and a metropolitan populati ...

.Sidi Kacem

Sidi Kacem ( Berber: ⵙⵉⴷⵉ ⵇⴰⵙⴰⵎ, ary, سيدي قاسم, sidi qasəm) is a city in Rabat-Salé-Kénitra, Morocco. It is the capital of Sidi Kacem Province.

History

During the French period the city was called Petitjean, in ...

) turned into an anti-Jewish riot and resulted in the death of 6 Jewish merchants from Marrakesh

Marrakesh or Marrakech ( or ; ar, مراكش, murrākuš, ; ber, ⵎⵕⵕⴰⴽⵛ, translit=mṛṛakc}) is the fourth largest city in the Kingdom of Morocco. It is one of the four Imperial cities of Morocco and is the capital of the Marrakes ...

. However, according to Francis Lacoste, French Resident-General in Morocco, "the ethnicity of the Petitjean victims was coincidental, terrorism rarely targeted Jews, and fears about their future were unwarranted." In 1955, a mob broke into the Jewish Mellah in Mazagan (known today as El Jadida

El Jadida (, ; originally known in Berber as Maziɣen or Mazighen; known in Portuguese as Mazagão) is a major port city on the Atlantic coast of Morocco, located 96 km south of the city of Casablanca, in the province of El Jadida and the ...

) and caused its 1700 Jewish residents to flee to the European quarters of the city. The houses of some 200 Jews were too badly damaged during the riots for them to return. In 1954, Mossad had established an undercover base in Morocco, sending agents and emissaries within a year to appraise the situation and organize continuous emigration.[ The operations were composed of five branches: self-defense, information and intelligence, illegal immigration, establishing contact, and public relations. Mossad chief ]Isser Harel

Isser Harel ( he, איסר הראל, 1912 – 18 February 2003) was spymaster of the intelligence and the security services of Israel and the Director of the Mossad (1952–1963). In his capacity as Mossad director he oversaw the capture and co ...

visited the country in 1959 and 1960, reorganized the operations, and created a clandestine militia named the "Misgeret" ("framework").

Emigration to Israel jumped from 8,171 persons in 1954 to 24,994 in 1955, increasing further in 1956. Between 1955 and independence in 1956, 60,000 Jews emigrated.[Xavier Cornut, Jerusalem Post, 2009]

The Moroccan connection: Exploring the decades of secret ties between Jerusalem and Rabat.

"In 1954, Mossad head Isser Harel decided to establish a clandestine base in Morocco. An undercover agent named Shlomo Havilio was sent to monitor the conditions of Jews in the country. His report was alarming: The Jews feared the departure of the French colonial forces and the growing hostility of pan-Arabism; Jewish communities could not be defended and their situation was likely to worsen once Morocco became independent. Havilio had only one solution: a massive emigration to Israel. Harel agreed. Less than a year after his report, the Mossad sent its first agents and emissaries to Morocco to appraise the situation and to organize a nonstop aliya. About 90,000 Jews had emigrated between 1948 and 1955, and 60,000 more would leave in the months preceding the country's independence. Then, on September 27, 1956, the Moroccan authorities stopped all emigration, declaring it illegal. From then until 1960 only a few thousand left clandestinely each year." On 7 April 1956, Morocco attained independence. Jews occupied several political positions, including three parliamentary seats and the cabinet position of Minister of Posts and Telegraphs. However, that minister, Leon Benzaquen

Leon Benzaquen (Tangier, 31 December 1928 – May 1977) was a Morocco, Moroccan doctor who became the personal doctor for King Mohammed V of Morocco, and the first Moroccan Jewish minister after Morocco received its independence in 1956, in its ...

, did not survive the first cabinet reshuffling, and no Jew was appointed again to a cabinet position. Although the relations with the Jewish community at the highest levels of government were cordial, these attitudes were not shared by the lower ranks of officialdom, which exhibited attitudes that ranged from traditional contempt to outright hostility. Morocco's increasing identification with the Arab world

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western A ...

, and pressure on Jewish educational institutions to arabize and conform culturally added to the fears of Moroccan Jews. Between 1956 and 1961, emigration to Israel was prohibited by law;[ clandestine emigration continued, and a further 18,000 Jews left Morocco.

On 10 January 1961 the '' Egoz'', a Mossad-leased ship carrying Jews attempting to emigrate undercover, sank off the northern coast of Morocco. According to ]Tad Szulc

Tadeusz Witold Szulc (July 25, 1926 – May 21, 2001) was an author and foreign correspondent for ''The New York Times'' from 1953 to 1972. Szulc is credited with breaking the story of the Bay of Pigs invasion.

Early life

Szulc was born in War ...

, the Misgeret commander in Morocco, Alex Gattmon, decided to precipitate a crisis on the back of the tragedy, consistent with Mossad Director Isser Harel

Isser Harel ( he, איסר הראל, 1912 – 18 February 2003) was spymaster of the intelligence and the security services of Israel and the Director of the Mossad (1952–1963). In his capacity as Mossad director he oversaw the capture and co ...

's scenario that "a wedge had to be forced between the royal government and the Moroccan Jewish community and that anti-Hassan nationalists had to be used as leverage as well if a compromise over emigration was ever to be attained". A pamphlet

A pamphlet is an unbound book (that is, without a hard cover or binding). Pamphlets may consist of a single sheet of paper that is printed on both sides and folded in half, in thirds, or in fourths, called a ''leaflet'' or it may consist of a ...

agitating for illegal emigration, supposedly by an underground Zionist organization, was printed by Mossad and distributed throughout Morocco, causing the government to "hit the roof". These events prompted King Mohammed V to allow Jewish emigration, and over the three following years, more than 70,000 Moroccan Jews left the country, primarily as a result of Operation Yachin

Operation Yakhin was an operation to secretly emigrate Moroccan Jews to Israel, conducted by Israel's Mossad between November 1961 and spring 1964. About 97,000 left for Israel by plane and ship from Casablanca and Tangier via France and Italy. ...

.

Operation Yachin

Operation Yakhin was an operation to secretly emigrate Moroccan Jews to Israel, conducted by Israel's Mossad between November 1961 and spring 1964. About 97,000 left for Israel by plane and ship from Casablanca and Tangier via France and Italy. ...

was fronted by the New York-based Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society

HIAS (founded as the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society) is a Jewish American nonprofit organization that provides humanitarian aid and assistance to refugees. It was originally established in 1881 to aid Jewish refugees. In 1975, the State Departm ...

(HIAS), who financed approximately $50 million of costs. HIAS provided an American cover for underground Israeli agents in Morocco, whose functions included organizing emigration, arming of Jewish Moroccan communities for self-defense and negotiations with the Moroccan government. By 1963, the Moroccan Interior Minister Colonel Oufkir and Mossad chief Meir Amit

Meir Amit ( he, מאיר עמית, 17 March 1921 – 17 July 2009) was an Israeli politician and cabinet minister. He served as the Chief Director and the head of global operations for Mossad from 1963 to 1968, before entering into politics an ...

agreed to swap Israeli training of Moroccan security services and some covert military assistance for intelligence on Arab affairs and continued Jewish emigration.

By 1967, only 50,000 Jews remained. The 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

led to increased Arab–Jewish tensions worldwide, including in Morocco, and significant Jewish emigration out of the country continued. By the early 1970s, the Jewish population of Morocco fell to 25,000; however, most of the emigrants went to France, Belgium, Spain, and Canada, rather than Israel.

According to Esther Benbassa

Esther Benbassa (born 27 March 1950) is a French-Turkish-Israeli historian and politician. She specializes in the history of Jews and other minorities. Since 2011, Benbassa has served as a French senator, representing Paris from 2017 onwards an ...

, the migration of Jews from the North African countries was prompted by uncertainty about the future. In 1948, 250,000André Azoulay

André Azoulay ( ar, أندري أزولاي, Berber: ⴰⵏⴷⵔⵉ ⴰⵣⵓⵍⴰⵢ, born 17 April 1941) is a Moroccan Jewish senior adviser to king Mohammed VI of Morocco. , and Jewish schools and synagogues receive government subsidies. Despite this, Jewish targets have sometimes been attacked (notably the 2003 bombing attacks on a Jewish community center in Casablanca), and there is sporadic anti-Semitic rhetoric from radical Islamist groups. Tens of thousands of Israeli Jews with Moroccan heritage visits Morocco every year, especially around Rosh Hashana or Passover,Hassan II Hassan, Hasan, Hassane, Haasana, Hassaan, Asan, Hassun, Hasun, Hassen, Hasson or Hasani may refer to:

People

* Hassan (given name), Arabic given name and a list of people with that given name

*Hassan (surname), Arabic, Jewish, Irish, and Scotti ...

's offer to return and settle in Morocco.

Algeria

As in Tunisia and Morocco,

As in Tunisia and Morocco, Algerian Jews

The History of the Jews in Algeria refers to the history of the Jewish community of Algeria, which dates to the 1st century CE. In the 15th century, many Spanish Jews fled to the Maghreb, including today's Algeria, following expulsion from Spai ...

did not face large scale expulsion or outright asset confiscation or any similar government persecution during the period of exile, and Zionist agents were relatively allowed freedom of action to encourage emigration.[

Jewish emigration from Algeria was part of a wider ending of French colonial control and the related social, economic and cultural changes.

The Israeli government had been successful in encouraging Morocco and Tunisian Jews to emigrate to Israel, but were less so in Algeria. Despite offers of visa and economic subsidies, only 580 Jews moved from Algeria to Israel in 1954–55.

Emigration peaked during the ]Algerian War

The Algerian War, also known as the Algerian Revolution or the Algerian War of Independence,( ar, الثورة الجزائرية '; '' ber, Tagrawla Tadzayrit''; french: Guerre d'Algérie or ') and sometimes in Algeria as the War of 1 November ...

of 1954–1962, during which thousands of Muslims, Christians and Jews left the country, particularly the Pied-Noir community. In 1956, Mossad agents worked underground to organize and arm the Jews of Constantine, who comprised approximately half the Jewish population of the country. In Oran, a Jewish counter-insurgency movement was thought to have been trained by former members of Irgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

.

As of the last census in Algeria, taken on 1 June 1960, there were 1,050,000 non-Muslim civilians in Algeria (10 percent of the total population including 130,000." Algerian Jews

The History of the Jews in Algeria refers to the history of the Jewish community of Algeria, which dates to the 1st century CE. In the 15th century, many Spanish Jews fled to the Maghreb, including today's Algeria, following expulsion from Spai ...

).Pieds-Noirs

The ''Pieds-Noirs'' (; ; ''Pied-Noir''), are the people of French and other European descent who were born in Algeria during the period of French rule from 1830 to 1962; the vast majority of whom departed for mainland France as soon as Alger ...

'' (including Jews) were evacuated to mainland France while about 200,000 chose to remain in Algeria. Of the latter, there were still about 100,000 in 1965 and about 50,000 by the end of the 1960s.["Pieds-noirs": ceux qui ont choisi de rester](_blank)

La Dépêche du Midi

''La Dépêche'', formally ''La Dépêche du Midi'', is a regional daily newspaper published in Toulouse in Southwestern France with seventeen editions for different areas of the Midi-Pyrénées region. The main local editions are for Toulouse, ...

, March 2012

As the Algerian Revolution began to intensify in the late 1950s and early 1960s, most of Algeria's 140,000 Jews began to leave. The community had lived mainly in Algiers

Algiers ( ; ar, الجزائر, al-Jazāʾir; ber, Dzayer, script=Latn; french: Alger, ) is the capital and largest city of Algeria. The city's population at the 2008 Census was 2,988,145Census 14 April 2008: Office National des Statistiques ...

and Blida

Blida ( ar, البليدة; Tamazight: Leblida) is a city in Algeria. It is the capital of Blida Province, and it is located about 45 km south-west of Algiers, the national capital. The name ''Blida'', i.e. ''bulaydah'', is a diminutive ...

, Constantine, and Oran.

Almost all Jews of Algeria left upon independence in 1962, particularly as "the Algerian Nationality Code of 1963 excluded non-Muslims from acquiring citizenship", allowing citizenship only to those Algerians who had Muslim fathers and paternal grandfathers. Algeria's 140,000 Jews, who had French citizenship since 1870 (briefly revoked by Vichy France in 1940) left mostly for France, although some went to Israel.

The Algiers synagogue was consequently abandoned after 1994.

Jewish migration from North Africa to France led to the rejuvenation of the French Jewish community, which is now the third largest in the world.

Tunisia

As in Morocco and Algeria,

As in Morocco and Algeria, Tunisian Jews

The history of the Jews in Tunisia extended nearly two thousand years and goes back to the Punic era. The Jewish community in Tunisia is no doubt older and grew up following successive waves of immigration and proselytism before its develo ...

did not face large scale expulsion or outright asset confiscation or any similar government persecution during the period of exile, and Zionist agents were relatively allowed freedom of action to encourage emigration.[

In 1948, approximately 105,000 Jews lived in Tunisia.]Djerba

Djerba (; ar, جربة, Jirba, ; it, Meninge, Girba), also transliterated as Jerba or Jarbah, is a Tunisian island and the largest island of North Africa at , in the Gulf of Gabès, off the coast of Tunisia. It had a population of 139,544 ...

, Tunis

''Tounsi'' french: Tunisois

, population_note =

, population_urban =

, population_metro = 2658816

, population_density_km2 =

, timezone1 = CET

, utc_offset1 ...

, and Zarzis

Zarzis also known as Jarjis ( ar, جرجيس, link=no ') is a coastal commune (municipality) in southeastern Tunisia, former bishopric and Latin Catholic titular see under its ancient name Gergis.

To the Phoenicians, Romans and Arabs the port was ...

. Following Tunisia's independence from France in 1956 emigration of the Jewish population to Israel and France accelerated.Al-Qaeda

Al-Qaeda (; , ) is an Islamic extremism, Islamic extremist organization composed of Salafist jihadists. Its members are mostly composed of Arab, Arabs, but also include other peoples. Al-Qaeda has mounted attacks on civilian and military ta ...

.

Libya

According to Maurice Roumani, a Libyan emigrant who was previously the executive director of WOJAC

World Organization of Jews from Arab Countries (WOJAC) was an international Advocacy group, advocacy organization, created in 1975, representing Jewish exodus from Arab and Muslim countries, Jewish refugees from Arab countries. The World Organizat ...

, the most important factors that influenced the Libyan Jewish community to emigrate were "the scars left from the last years of the Italian occupation and the entry of the British Military in 1943 accompanied by the Jewish Palestinian soldiers".

Zionist emissaries, so-called "shlichim", had begun arriving in Libya in the early 1940s, with the intention to "transform the community and transfer it to Palestine". In 1943, Mossad LeAliyah Bet

The Mossad LeAliyah Bet ( he, המוסד לעלייה ב', lit. ''Institution for Immigration B'') was a branch of the paramilitary organization Haganah in British Mandatory Palestine, and later the State of Israel, that operated to facilitate Je ...

began to send emissaries to prepare the infrastructure for the emigration of the Libyan Jewish community.

In 1942, German troops fighting the Allies in North Africa occupied the Jewish quarter of Benghazi

Benghazi () , ; it, Bengasi; tr, Bingazi; ber, Bernîk, script=Latn; also: ''Bengasi'', ''Benghasi'', ''Banghāzī'', ''Binghāzī'', ''Bengazi''; grc, Βερενίκη (''Berenice'') and ''Hesperides''., group=note (''lit. Son of he Ghazi ...

, plundering shops and deporting more than 2,000 Jews across the desert. Sent to work in labor camps, more than one-fifth of that group of Jews perished. At the time, most of the Jews were living in cities of Tripoli

Tripoli or Tripolis may refer to:

Cities and other geographic units Greece

*Tripoli, Greece, the capital of Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (region of Arcadia), a district in ancient Arcadia, Greece

* Tripolis (Larisaia), an ancient Greek city in ...

and Benghazi and there were smaller numbers in Bayda and Misrata

Misrata ( ; also spelled Misurata or Misratah; ar, مصراتة, Miṣrāta ) is a city in the Misrata District in northwestern Libya, situated to the east of Tripoli and west of Benghazi on the Mediterranean coast near Cape Misrata. With ...

.Battle of El Agheila

The Battle of El Agheila was a brief engagement of the Western Desert Campaign of the Second World War. It took place in December 1942 between Allied forces of the Eighth Army (General Bernard Montgomery) and the Axis forces of the German-Ita ...

in December 1942, German and Italian troops were driven out of Libya. The British garrison

A garrison (from the French ''garnison'', itself from the verb ''garnir'', "to equip") is any body of troops stationed in a particular location, originally to guard it. The term now often applies to certain facilities that constitute a mil ...

ed the Palestine Regiment

The Palestine Regiment was an infantry regiment of the British Army that was formed in 1942. During the Second World War, the regiment was deployed to Egypt and Cyrenaica, but most of their work consisted of guard duty. Some Palestine Regiment mem ...

in Cyrenaica

Cyrenaica ( ) or Kyrenaika ( ar, برقة, Barqah, grc-koi, Κυρηναϊκή ��παρχίαKurēnaïkḗ parkhíā}, after the city of Cyrene), is the eastern region of Libya. Cyrenaica includes all of the eastern part of Libya between ...

, which later became the core of the Jewish Brigade

The Jewish Infantry Brigade Group, more commonly known as the Jewish Brigade Group or Jewish Brigade, was a military formation of the British Army in the World War II, Second World War. It was formed in late 1944 and was recruited among Yishuv, Y ...

, which was later also stationed in Tripolitania

Tripolitania ( ar, طرابلس '; ber, Ṭrables, script=Latn; from Vulgar Latin: , from la, Regio Tripolitana, from grc-gre, Τριπολιτάνια), historically known as the Tripoli region, is a historic region and former province o ...

. The pro-Zionist soldiers encouraged the spread of Zionism throughout the local Jewish population

Following the liberation of North Africa by allied forces, antisemitic incitements were still widespread. The most severe racial violence between the start of World War II and the establishment of Israel erupted in Tripoli in November 1945. Over a period of several days more than 140 Jews (including 36 children) were killed, hundreds were injured, 4,000 were displaced and 2,400 were reduced to poverty. Five synagogues in Tripoli and four in provincial towns were destroyed, and over 1,000 Jewish residences and commercial buildings were plundered in Tripoli alone. Gil Shefler writes that "As awful as the pogrom in Libya was, it was still a relatively isolated occurrence compared to the mass murders of Jews by locals in Eastern Europe."Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

, which resulted in 10 Jewish victims.

In 1948, about 38,000 Jews lived in Libya.Jewish Agency for Israel

The Jewish Agency for Israel ( he, הסוכנות היהודית לארץ ישראל, translit=HaSochnut HaYehudit L'Eretz Yisra'el) formerly known as The Jewish Agency for Palestine, is the largest Jewish non-profit organization in the world. ...

office in Tripoli. According to Harvey E. Goldberg, "a number of Libyan Jews" believe that the Jewish Agency was behind the riots, given that the riots helped them achieve their goal. Between the establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 and Libyan independence in December 1951 over 30,000 Libyan Jews emigrated to Israel.

On 31 December 1958 a decree was issued by the President of the Executive Council of Tripolitania, which ordered the dissolution of the Jewish Community Council and the appointment of a Muslim commissioner nominated by the Government. A law issued in 1961 required Libyan citizenship for the possession and transfer of property in Libya, a requirement that was rejected to all but six Libyan Jews.

In 1967, during the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

, the Jewish population of over 4,000 was again subjected to riots in which 18 were killed and many more injured. The pro-Western Libyan government of King Idris

Muhammad Idris bin Muhammad al-Mahdi as-Senussi ( ar, إدريس, Idrīs; 13 March 1890 – 25 May 1983) was a Libyan political and religious leader who was King of Libya from 24 December 1951 until his overthrow on 1 September 1969. He ruled o ...

tried unsuccessfully to maintain law and order. On 17 June 1967, Lillo Arbib, leader of the Jewish community in Libya, sent a formal request to Libyan prime minister Hussein Maziq

Hussein Yousef Maziq ( ar, حسين يوسف مازق) a Libyan politician (26 June 1918 – 12 May 2006) was Prime Minister of Libya from 20 March 1965 to 2 July 1967. He was one of the most important men in the Kingdom era of Libya.

Family ...

requesting that the government "allow Jews so desiring to leave the country for a time, until tempers cool and the Libyan population understands the position of Libyan Jews, who have always been and will continue to be loyal to the State, in full harmony and peaceful coexistence with the Arab citizens at all times."Italian Navy

"Fatherland and Honour"

, patron =

, colors =

, colors_label =

, march = ( is the return of soldiers to their barrack, or sailors to their ship after a ...

, where they were assisted by the Jewish Agency for Israel. Of the Jews evacuated, 1,300 subsequently immigrated to Israel, 2,200 remained in Italy, and most of the rest went to the United States. A few scores remained in Libya. Some Libyan Jews who had been evacuated temporarily returned to Libya between 1967 and 1969 in an attempt to recover lost property. In September 1967 only 100 Jews remained in Libya,[ falling to less than 40 five years later in 1972 and just 16 by 1977.

On 21 July 1970 the Libyan government issued a law which confiscated assets of the Jews who had previously left Libya, issuing in their stead 15-year bonds. However, when the bonds matured in 1985 no compensation was paid. Libyan leader ]Muammar Gaddafi

Muammar Muhammad Abu Minyar al-Gaddafi, . Due to the lack of standardization of transcribing written and regionally pronounced Arabic, Gaddafi's name has been romanized in various ways. A 1986 column by ''The Straight Dope'' lists 32 spellin ...

later justified this on the grounds that "the alignment of the Jews with Israel, the Arab nations' enemy, has forfeited their right to compensation."

Although the main synagogue in Tripoli was renovated in 1999, it has not reopened for services. In 2002, Esmeralda Meghnagi, who was thought to be the last Jew in Libya, died. However, that same year, it was discovered that Rina Debach, an 80-year old Jewish woman who was thought to be dead by her family in Rome

, established_title = Founded

, established_date = 753 BC

, founder = King Romulus (legendary)

, image_map = Map of comune of Rome (metropolitan city of Capital Rome, region Lazio, Italy).svg

, map_caption ...

, was still alive and living in a nursing home in the country. With her subsequent departure for Rome, there were no more Jews left in Libya.

Israel is home to a significant population of Jews of Libyan descent, who maintain their unique traditions. Jews of Libyan descent also make up a significant part of the Italian Jewish community. About 30% of the registered Jewish population of Rome is of Libyan origin.

Middle East

Iraq

1930s and early 1940s

The British mandate over Iraq came to an end in June 1930, and in October 1932 the country became independent. The Iraqi government response to the demand of Assyrian

Assyrian may refer to:

* Assyrian people, the indigenous ethnic group of Mesopotamia.

* Assyria, a major Mesopotamian kingdom and empire.

** Early Assyrian Period

** Old Assyrian Period

** Middle Assyrian Empire

** Neo-Assyrian Empire

* Assyrian ...

autonomy (the Assyrians being the indigenous

Indigenous may refer to:

*Indigenous peoples

*Indigenous (ecology), presence in a region as the result of only natural processes, with no human intervention

*Indigenous (band), an American blues-rock band

*Indigenous (horse), a Hong Kong racehorse ...

Eastern Aramaic-speaking Semitic descendants of the ancient Assyrians and Mesopotamians

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the F ...

, and largely affiliated to the Assyrian Church of the East

The Assyrian Church of the East,, ar, كنيسة المشرق الآشورية sometimes called Church of the East, officially the Holy Apostolic Catholic Assyrian Church of the East,; ar, كنيسة المشرق الآشورية الرسول� ...

, Chaldean Catholic Church

, native_name_lang = syc

, image = Assyrian Church.png

, imagewidth = 200px

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Our Lady of Sorrows Baghdad, Iraq

, abbreviation =

, type ...

and Syriac Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = syc

, image = St_George_Syriac_orthodox_church_in_Damascus.jpg

, imagewidth = 250

, alt = Cathedral of Saint George

, caption = Cathedral of Saint George, Damascus ...

), turned into a bloody massacre of Assyrian villagers by the Iraqi army in August 1933. This event was the first sign to the Jewish community that minority rights were meaningless under Iraqi monarchy. King Faisal, known for his liberal policies, died in September 1933, and was succeeded by Ghazi, his nationalistic anti-British son. Ghazi began promoting Arab nationalist

Arab nationalism ( ar, القومية العربية, al-Qawmīya al-ʿArabīya) is a nationalist ideology that asserts the Arabs are a nation and promotes the unity of Arab people, celebrating the glories of Arab civilization, the language an ...

organizations, headed by Syrian and Palestinian exiles. With 1936–39 Arab revolt in Palestine, they were joined by rebels, such as the Grand Mufti of Jerusalem

The Grand Mufti of Jerusalem is the Sunni Muslim cleric in charge of Jerusalem's Islamic holy places, including the Al-Aqsa Mosque. The position was created by the British military government led by Ronald Storrs in 1918.See Islamic Leadershi ...

. The exiles preached pan-Arab ideology and fostered anti-Zionist propaganda.

Under Iraqi nationalists, Nazi propaganda began to infiltrate the country, as Nazi Germany was anxious to expand its influence in the Arab world. Dr. Fritz Grobba

Fritz Konrad Ferdinand Grobba (18 July 1886 – 2 September 1973) was a German diplomat during the interwar period and World War II.

Early life

He was born in Gartz on the Oder in the Province of Brandenburg, Germany. His parents were Rudolf Grob ...

, who resided in Iraq since 1932, began to vigorously and systematically disseminate hateful propaganda against Jews. Among other things, Arabic translation of ''Mein Kampf

(; ''My Struggle'' or ''My Battle'') is a 1925 autobiographical manifesto by Nazi Party leader Adolf Hitler. The work describes the process by which Hitler became antisemitic and outlines his political ideology and future plans for Germ ...

'' was published and Radio Berlin had begun broadcasting in Arabic language. Anti-Jewish policies had been implemented since 1934, and the confidence of Jews was further shaken by the growing crisis in Palestine in 1936. Between 1936 and 1939 ten Jews were murdered and on eight occasions bombs were thrown on Jewish locations.

In 1941, immediately following the British victory in the

In 1941, immediately following the British victory in the Anglo-Iraqi War

The Anglo-Iraqi War was a British-led Allied military campaign during the Second World War against the Kingdom of Iraq under Rashid Gaylani, who had seized power in the 1941 Iraqi coup d'état, with assistance from Germany and Italy. The ca ...

, riots known as the Farhud

''Farhud'' ( ar, الفرهود) was the pogrom or "violent dispossession" carried out against the Jewish population of Baghdad, Iraq, on June 1–2, 1941, immediately following the British victory in the Anglo-Iraqi War. The riots occurred in a ...

broke out in Baghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

in the power vacuum

In political science and political history, the term power vacuum, also known as a power void, is an analogy between a physical vacuum to the political condition "when someone in a place of power, has lost control of something and no one has repla ...

following the collapse of the pro-Axis

An axis (plural ''axes'') is an imaginary line around which an object rotates or is symmetrical. Axis may also refer to:

Mathematics

* Axis of rotation: see rotation around a fixed axis

* Axis (mathematics), a designator for a Cartesian-coordinat ...

government of Rashid Ali al-Gaylani

Rashid Ali al-Gaylaniin Arab standard pronunciation Rashid Aali al-Kaylani; also transliterated as Sayyid Rashid Aali al-Gillani, Sayyid Rashid Ali al-Gailani or sometimes Sayyad Rashid Ali el Keilany (" Sayyad" serves to address higher standing ...

while the city was in a state of instability. 180 Jews were killed and another 240 wounded; 586 Jewish-owned businesses were looted and 99 Jewish houses were destroyed.

In some accounts the Farhud marked the turning point for Iraq's Jews. Other historians, however, see the pivotal moment for the Iraqi Jewish community much later, between 1948 and 1951, since Jewish communities prospered along with the rest of the country throughout most of the 1940s,

In some accounts the Farhud marked the turning point for Iraq's Jews. Other historians, however, see the pivotal moment for the Iraqi Jewish community much later, between 1948 and 1951, since Jewish communities prospered along with the rest of the country throughout most of the 1940s,[, quote(1): " s a resultof the economic boom and the security granted by the government. ... Jews who left Iraq immediately after the riots, later returned." Quote(2): "Their dream of integration into Iraqi society had been dealt a severe blow by the farhud but as the years passed self-confidence was restored, since the state continued to protect the Jewish community and they continued to prosper." Quote(3): Quoting ]Enzo Sereni

Enzo Sereni (17 April 190518 November 1944) was an Italian Socialist Zionist, co-founder of kibbutz Givat Brenner, celebrated intellectual, advocate of Jewish-Arab co-existence and a Jewish Brigade officer who was parachuted into Nazi-occupied ...

: "The Jews have adapted to the new situation with the British occupation, which has again given them the possibility of free movement after months of detention and fear."[London Review of Books, Vol. 30 No. 21 • 6 November 2008, pages 23–25, Adam Shatz]

"Yet Sasson Somekh insists that the farhud was not 'the beginning of the end'. Indeed, he claims it was soon 'almost erased from the collective Jewish memory', washed away by 'the prosperity experienced by the entire city from 1941 to 1948'. Somekh, who was born in 1933, remembers the 1940s as a 'golden age' of 'security', 'recovery' and 'consolidation', in which the 'Jewish community had regained its full creative drive'. Jews built new homes, schools and hospitals, showing every sign of wanting to stay. They took part in politics as never before; at Bretton Woods, Iraq was represented by Ibrahim al-Kabir, the Jewish finance minister. Some joined the Zionist underground, but many more waved the red flag. Liberal nationalists and Communists rallied people behind a conception of national identity far more inclusive than the Golden Square's Pan-Arabism, allowing Jews to join ranks with other Iraqis – even in opposition to the British and Nuri al-Said, who did not take their ingratitude lightly." and many Jews who left Iraq following the Farhud returned to the country shortly thereafter and permanent emigration did not accelerate significantly until 1950–51.[

Either way, the Farhud is broadly understood to mark the start of a process of politicization of the Iraqi Jews in the 1940s, primarily among the younger population, especially as a result of the impact it had on hopes of long term integration into Iraqi society. In the direct aftermath of the Farhud, many joined the Iraqi Communist Party in order to protect the Jews of Baghdad, yet they did not want to leave the country and rather sought to fight for better conditions in Iraq itself. At the same time the Iraqi government that had taken over after the Farhud reassured the Iraqi Jewish community, and normal life soon returned to Baghdad, which saw a marked betterment of its economic situation during World War II.

] Shortly after the Farhud in 1941, Mossad LeAliyah Bet sent emissaries to Iraq to begin to organize emigration to Israel, initially by recruiting people to teach Hebrew and hold lectures on Zionism. In 1942,

Shortly after the Farhud in 1941, Mossad LeAliyah Bet sent emissaries to Iraq to begin to organize emigration to Israel, initially by recruiting people to teach Hebrew and hold lectures on Zionism. In 1942, Shaul Avigur

Shaul Avigur ( he, שאול אביגור; 11 September 1899 – 29 August 1978) was a founder of the Israeli Intelligence Community.

Biography

Avigur was born in Dvinsk (now Daugavpils in Latvia) under the name Saul Meyeroff (''later'' Meirov; ...

, head of Mossad LeAliyah Bet

The Mossad LeAliyah Bet ( he, המוסד לעלייה ב', lit. ''Institution for Immigration B'') was a branch of the paramilitary organization Haganah in British Mandatory Palestine, and later the State of Israel, that operated to facilitate Je ...

, entered Iraq undercover in order to survey the situation of the Iraqi Jews with respect to immigration to Israel. During the 1942–43, Avigur made four further trips to Baghdad to arrange the required Mossad machinery, including a radio transmitter for sending information to Tel Aviv, which remained in use for 8 years. In late 1942, one of the emissaries explained the size of their task of converting the Iraqi community to Zionism, writing that "we have to admit that there is not much point in rganizing and encouraging emigration ... We are today eating the fruit of many years of neglect, and what we didn't do can't be corrected now through propaganda and creating one-day-old enthusiasm." It was not until 1947 that legal and illegal departures from Iraq to Israel began. Around 8,000 Jews left Iraq between 1919 and 1948, with another 2,000 leaving between mid-1948 to mid-1950.[ Mike Marqusee, "Diasporic Dimensions" in If I am Not for Myself, Journey of an Anti-Zionist Jew, 2011]

1948 Arab–Israeli War

In 1948, there were approximately 150,000 Jews in Iraq. The community was concentrated in Baghdad and Basra

Basra ( ar, ٱلْبَصْرَة, al-Baṣrah) is an Iraqi city located on the Shatt al-Arab. It had an estimated population of 1.4 million in 2018. Basra is also Iraq's main port, although it does not have deep water access, which is hand ...

.

Before United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Re ...

vote, the Iraq's prime minister Nuri al-Said

Nuri Pasha al-Said CH (December 1888 – 15 July 1958) ( ar, نوري السعيد) was an Iraqi politician during the British mandate in Iraq and the Hashemite Kingdom of Iraq. He held various key cabinet positions and served eight terms as ...

told British diplomats that if the United Nations solution was not "satisfactory", "severe measures should ould?be taken against all Jews in Arab countries". In a speech at the General Assembly Hall at Flushing Meadow, New York, on Friday, 28 November 1947, Iraq's Foreign Minister, Fadel Jamall, included the following statement: "Partition imposed against the will of the majority of the people will jeopardize peace and harmony in the Middle East. Not only the uprising of the Arabs of Palestine is to be expected, but the masses in the Arab world cannot be restrained. The Arab–Jewish relationship in the Arab world will greatly deteriorate. There are more Jews in the Arab world outside of Palestine than there are in Palestine. In Iraq alone, we have about one hundred and fifty thousand Jews who share with Moslems and Christians all the advantages of political and economic rights. Harmony prevails among Moslems, Christians and Jews. But any injustice imposed upon the Arabs of Palestine will disturb the harmony among Jews and non-Jews in Iraq; it will breed inter-religious prejudice and hatred."Shafiq Ades

Shafiq Ades ( ar, شفيق عدس, he, שפיק עדס; born in 1900, died on 23 September 1948) was a wealthy Iraqi-Jewish businessman of Syrian origins. After a short show trial in 1948, he was executed by hanging on charges of selling weapons ...

(one of the most important anti-Zionist Jewish businessmen in the country) was arrested and publicly hanged for allegedly selling goods to Israel, shocking the community. The Jewish community general sentiment was that if a man as well connected and powerful as Shafiq Ades

Shafiq Ades ( ar, شفيق عدس, he, שפיק עדס; born in 1900, died on 23 September 1948) was a wealthy Iraqi-Jewish businessman of Syrian origins. After a short show trial in 1948, he was executed by hanging on charges of selling weapons ...

could he eliminated by the state, other Jews would not be protected any longer.[: "the general sentiment was chat if a man as well connected and powerful as Adas could he eliminated by the state, other Jews would not be protected any longer."]

Additionally, like most Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

states, Iraq forbade any legal emigration of its Jews after the 1948 war on the grounds that they might go to Israel and could strengthen that state. At the same time, increasing government oppression of the Jews fueled by anti-Israeli sentiment together with public expressions of antisemitism created an atmosphere of fear and uncertainty.

However, by 1949 Jews were escaping Iraq at about a rate of 1,000 a month. At the time, the British believed that the Zionist underground was agitating in Iraq in order to assist US fund-raising and to "offset the bad impression caused by the Jewish attitudes to Arab refugees".

The Iraqi government took in only 5,000 of the approximately 700,000 Palestinians who became refugees in 1948–49, "despite British and American efforts to persuade Iraq" to admit more. In January 1949, the pro-British Iraqi Prime Minister Nuri al-Said discussed the idea of deporting Iraqi Jews to Israel with British officials, who explained that such a proposal would benefit Israel and adversely affect Arab countries. According to Meir-Glitzenstein, such suggestions were "not intended to solve either the problem of the Palestinian Arab refugees or the problem of the Jewish minority in Iraq, but to torpedo plans to resettle Palestinian Arab refugees in Iraq". In July 1949 the British government proposed to Nuri al-Said a population exchange

Population transfer or resettlement is a type of mass migration, often imposed by state policy or international authority and most frequently on the basis of ethnicity or religion but also due to economic development. Banishment or exile is a ...

in which Iraq would agree to settle 100,000 Palestinian refugees

Palestinian refugees are citizens of Mandatory Palestine, and their descendants, who fled or were expelled from their country over the course of the 1947–49 Palestine war (1948 Palestinian exodus) and the Six-Day War (1967 Palestinian exodu ...

in Iraq; Nuri stated that if a fair arrangement could be agreed, "the Iraqi government would permit a voluntary move by Iraqi Jews to Palestine." The Iraqi-British proposal was reported in the press in October 1949. On 14 October 1949 Nuri al-Said raised the exchange of population concept with the economic mission survey.[

]

A reversal: Allowing a Jewish immigration to Israel

In March 1950, Iraq reversed their earlier ban on Jewish emigration to Israel and passed a law of one-year duration allowing Jews to emigrate on the condition of relinquishing their Iraqi citizenship. According to

In March 1950, Iraq reversed their earlier ban on Jewish emigration to Israel and passed a law of one-year duration allowing Jews to emigrate on the condition of relinquishing their Iraqi citizenship. According to Abbas Shiblak

Abbas Shiblak (born 6 January 1944) is a Palestinian academic, historian, Research Associate at the Refugee Studies Centre (RSC), University of Oxford (a post he has held since 1992), free-lance writer, former diplomat and an advocate of human ri ...

, many scholars state that this was a result of American, British and Israeli political pressure on Tawfiq al-Suwaidi

Tawfiq al-Suwaidi ( ar, توفيق السويدي; 11 May 1892 – 15 October 1968) was an Iraqi politician who served as the prime minister of Iraq on three occasions stretching from 1929 to 1950.

Early life and education

Al-Suwaidi was born in B ...

's government, with some studies suggesting there were secret negotiations. According to Ian Black,Operation Ezra and Nehemiah

From 1951 to 1952, Operation Ezra and Nehemiah airlifted between 120,000 and 130,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel via Iran and Cyprus. The massive emigration of Iraqi Jews was among the most climactic events of the Jewish exodus from the Muslim World.

...

" to bring as many of the Iraqi Jews as possible to Israel.

The Zionist movement at first tried to regulate the amount of registrants until issues relating to their legal status were clarified. Later, it allowed everyone to register. Two weeks after the law went into force, the Iraqi interior minister demanded a CID investigation over why Jews were not registering. A few hours after the movement allowed registration, four Jews were injured in a bomb attack at a café in Baghdad.

Immediately following the March 1950 Denaturalisation Act, the emigration movement faced significant challenges. Initially, local Zionist activists forbade the Iraqi Jews from registering for emigration with the Iraqi authorities, because the Israeli government was still discussing absorption planning. However, on 8 April, a bomb exploded in a Jewish cafe in Baghdad, and a meeting of the Zionist leadership later that day agreed to allow registration without waiting for the Israeli government; a proclamation encouraging registration was made throughout Iraq in the name of the State of Israel.[ However, at the same time immigrants were also entering Israel from Poland and Romania, countries in which Prime Minister ]David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the nam ...

assessed there was a risk that the communist authorities would soon "close their gates", and Israel therefore delayed the transportation of Iraqi Jews.[ As a result, by September 1950, while 70,000 Jews had registered to leave, many selling their property and losing their jobs, only 10,000 had left the country.][ According to Esther Meir-Glitzenstein, "The thousands of poor Jews who had left or been expelled from the peripheral cities, and who had gone to Baghdad to wait for their opportunity to emigrate, were in an especially bad state. They were housed in public buildings and were being supported by the Jewish community. The situation was intolerable." The delay became a significant problem for the Iraqi government of Nuri al-Said (who replaced Tawfiq al-Suwaidi in mid-September 1950), as the large number of Jews "in limbo" created problems politically, economically and for domestic security. "Particularly infuriating" to the Iraqi government was the fact that the source of the problem was the Israeli government.

As a result of these developments, al-Said was determined to drive the Jews out of his country as quickly as possible.][ On 21 August 1950 al-Said threatened to revoke the license of the company transporting the Jewish exodus if it did not fulfill its daily quota of 500 Jews, and in September 1950, he summoned a representative of the Jewish community and warned the Jewish community of Baghdad to make haste; otherwise, he would take the Jews to the borders himself.]bombing campaign

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechanic ...

began against the Jewish community of Baghdad. The Iraqi government convicted and hanged a number of suspected Zionist agents for perpetrating the bombings, but the issue of who was responsible remains a subject of scholarly dispute. All but a few thousand of the remaining Jews then registered for emigration. In all, about 120,000 Jews left Iraq.

According to Gat, it is highly likely that one of Nuri as-Said's motives in trying to expel large numbers of Jews was the desire to aggravate Israel's economic problems (he had declared as such to the Arab world), although Nuri was well aware that the absorption of these immigrants was the policy on which Israel based its future. The Iraqi Minister of Defence told the U.S ambassador that he had reliable evidence that the emigrating Jews were involved in activities injurious to the state and were in contact with communist agents.

Between April 1950 and June 1951, Jewish targets in Baghdad were struck five times. Iraqi authorities then arrested 3 Jews, claiming they were Zionist activists, and sentenced two — Shalom Salah Shalom and Yosef Ibrahim Basri—to death. The third man, Yehuda Tajar, was sentenced to 10 years in prison.Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

after the Farhud of 1941. There has been much debate as to whether the bombs were planted by the Mossad to encourage Iraqi Jews to emigrate to Israel or if they were planted by Muslim extremists to help drive out the Jews. This has been the subject of lawsuits and inquiries in Israel.

The emigration law was to expire in March 1951, one year after the law was enacted. On 10 March 1951, 64,000 Iraqi Jews were still waiting to emigrate, the government enacted a new law blocking the assets of Jews who had given up their citizenship, and extending the emigration period.

The bulk of the Jews leaving Iraq did so via Israeli airlifts named Operation Ezra and Nehemiah

From 1951 to 1952, Operation Ezra and Nehemiah airlifted between 120,000 and 130,000 Iraqi Jews to Israel via Iran and Cyprus. The massive emigration of Iraqi Jews was among the most climactic events of the Jewish exodus from the Muslim World.

...

with special permission from the Iraqi government.

After 1951

A small Jewish community remained in Iraq following Operation Ezra and Nehemiah. Restrictions were placed on them after the Ba'ath Party came to power in 1963, and following the Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

, persecution greatly increased. Jews had their property expropriated and bank accounts frozen, their ability to do business was restricted, they were dismissed from public positions, and were placed under house arrest for extended periods of time. In 1968, scores of Jews were imprisoned on charges of spying for Israel. In 1969, about 50 were executed following show trials, most infamously in a mass public hanging of 14 men including 9 Jews, and a hundred thousand Iraqis marched past the bodies in a carnival-like atmosphere. Jews began sneaking across the border to Iran, from where they proceeded to Israel or the UK. In the early 1970s, the Iraqi government permitted Jewish emigration and the majority of the remaining community left Iraq. By 2003, it was estimated that this once-thriving community had been reduced to 35 Jews in Baghdad and a handful more in Kurdish areas of the country.

Egypt

Background

Although there was a small indigenous community, most Jews in Egypt in the early twentieth century were recent immigrants to the country, who did not share the Arabic language and culture.[: "Not only were they not Muslim, and mainly not of Egyptian origin; most of them did not share the Arabic language and culture, either. Added to these factors was their political diversity."] Many were members of the highly diverse Mutamassirun

The ( ar, متمصرون, plural, or in singular, literally "Egyptianized"Dictionary of Modern Written Arabic, https://archive.org/stream/Arabic-englsihDictionary_part3#page/n203/mode/1up/search/mutamassir p. 1070]) refers to "Egyptianized ...

community, which included other groups such as Greeks, Armenians, Syrian Christians and Italians, in addition to the British and French colonial authorities. Until the late 1930s, the Jews, both indigenous and new immigrants, like other minorities tended to apply for foreign citizenship in order to benefit from a foreign protection. The Egyptian government made it very difficult for non-Muslim foreigners to become naturalized. The poorer Jews, most of them indigenous and Oriental Jews, were left stateless, although they were legally eligible for Egyptian nationality. The drive to Egyptianize public life and the economy harmed the minorities, but the Jews had more strikes against them than the others. In the agitation against the Jews of the late thirties and the forties, the Jew has been seen as an enemyMahmoud an-Nukrashi Pasha

Mahmoud Fahmy El Nokrashy Pasha (April 26, 1888 – December 28, 1948) ( ar, محمود فهمى النقراشى باشا, ) was an Egyptian political figure. He was the second prime minister of the Kingdom of Egypt.

Early life ...

told the British ambassador: "All Jews were potential Zionists nd... anyhow all Zionists were Communists." On 24 November 1947, the head of the Egyptian delegation to the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...