Japan And Weapons Of Mass Destruction on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Beginning in the mid-1930s, Japan conducted numerous attempts to acquire and develop weapons of mass destruction. The 1943

Japan became interested in obtaining biological weapons during the early 1930s. Following an international ban on germ warfare in 1925 by the

Japan became interested in obtaining biological weapons during the early 1930s. Following an international ban on germ warfare in 1925 by the

Bug Bomb

, ''

Six-legged soldiers

, '' The Scientist'', October 24, 2008, accessed December 23, 2008.Novick, Lloyd and Marr, John S. ''Public Health Issues Disaster Preparedness'',

Google Books

, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2001, p. 87, (). Recent additional firsthand accounts testify the Japanese infected civilians through the distribution of plague-infested foodstuffs, such as dumplings and vegetables. During the

George H. Quester, ''Asian Survey'' Vol. 10, No. 9 (Sep., 1970), pp. 765-778, University of California Press. DOI: 10.2307/2643028 While there are currently no known plans in Japan to produce nuclear weapons, it has been argued that Japan has the technology, raw materials, and the capital to produce nuclear weapons within one year if necessary, and some analysts consider it a ''de facto'' nuclear state for this reason. For this reason Japan is often said to be a "screwdriver's turn" away from possessing nuclear weapons. During the 2016 U.S. presidential election it was proposed by

(March 10, 1952) ''The Pittsburgh Press'', Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Page 15.

/ref> The technical information of Japan's BW program participants was transferred into U.S. intelligence agencies and BW programs in exchange for immunity for war crimes charges.

"World War II plan to poison Japanese crops revealed"

THE COURIER-MAIL. Australia. Retrieved October 10, 2015. Archive date April 14, 2012. However, logistical problems would have reduced that estimate. In addition to work done in the anti-crop theater during the Cold War, the screening program for chemical defoliants was greatly accelerated. By the end of fiscal year 1962, the Chemical Corps had let or were negotiating contracts for over one thousand chemical defoliants. "The Okinawa tests evidently were fruitful." The presence of so-called rainbow herbicides such as Agent Orange has been widely reported on Okinawa as well as at other locations in Japan. The U.S. government disputes these assertions and the issues surrounding the subject of military use anti-plant agents in Japan during the 1950s through the 1970s remains a controversy.

'Were we marines used as guinea pigs on Okinawa?'

" '' Japan Times'', 4 December 2012, p. 14 The shipments, according to declassified documents, included sarin, VX, and mustard gas. By 1969, according to later newspaper reports, there was an estimated 1.9 million kg (1,900 metric tons) of VX stored on Okinawa. The chemical weapons brought to Okinawa included nerve and blister agents contained in rockets, artillery shells, bombs, mines, and one-ton (900 kg) containers. The chemicals were stored at Chibana Ammunition Depot. The depot was a hill-top installation next to

/ref> An official U.S. film on the mission says that 'safety was the primary concern during the operation,' though Japanese resentment of U.S. military activities on Okinawa also complicated the situation. At the technical level, time pressures imposed to complete the mission, the heat, and water rationing problems also complicated the planning. The initial phase of Operation Red Hat involved the movement of chemical munitions from a depot storage site to Tengan Pier, eight miles away, and required 1,332 trailers in 148 convoys. The second phase of the operation moved the munitions to Johnston Atoll. The

The secret agreement was concluded without any Japanese text so that it could be plausibly denied in Japan. Since only the American officials recorded the oral agreement, not having the agreement recorded in Japanese allowed Japan's leaders to deny its existence without fear that someone would leak a document to prove them wrong. The arrangement also made it appear that the United States alone was responsible for the transit of nuclear munitions through Japan. However, the original agreement document turned up in 1969 during preparation for an updated agreement, when a memorandum was written by a group of U.S. officials from the National Security Council Staff; the Departments of State, Defense, Army, Commerce and Treasury; the Joint Chiefs of Staff; the Central Intelligence Agency; and the

The secret agreement was concluded without any Japanese text so that it could be plausibly denied in Japan. Since only the American officials recorded the oral agreement, not having the agreement recorded in Japanese allowed Japan's leaders to deny its existence without fear that someone would leak a document to prove them wrong. The arrangement also made it appear that the United States alone was responsible for the transit of nuclear munitions through Japan. However, the original agreement document turned up in 1969 during preparation for an updated agreement, when a memorandum was written by a group of U.S. officials from the National Security Council Staff; the Departments of State, Defense, Army, Commerce and Treasury; the Joint Chiefs of Staff; the Central Intelligence Agency; and the  On the one year anniversary of the B-52 crash and explosion at Kadena Prime Minister Sato and President Nixon met in Washington, DC where several agreements including a revised Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) and a formal policy related to the future deployment of nuclear weapons on Okinawa were reached.

A draft of the November 21st, 1969, ''Agreed Minute to Joint Communique of United States President Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato'' was found in 1994. "The existence of this document has never been officially recognized by the Japanese or U.S. governments." The English text of the draft agreement reads:

United States President:

Japanese Prime Minister:

On the one year anniversary of the B-52 crash and explosion at Kadena Prime Minister Sato and President Nixon met in Washington, DC where several agreements including a revised Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) and a formal policy related to the future deployment of nuclear weapons on Okinawa were reached.

A draft of the November 21st, 1969, ''Agreed Minute to Joint Communique of United States President Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato'' was found in 1994. "The existence of this document has never been officially recognized by the Japanese or U.S. governments." The English text of the draft agreement reads:

United States President:

Japanese Prime Minister:

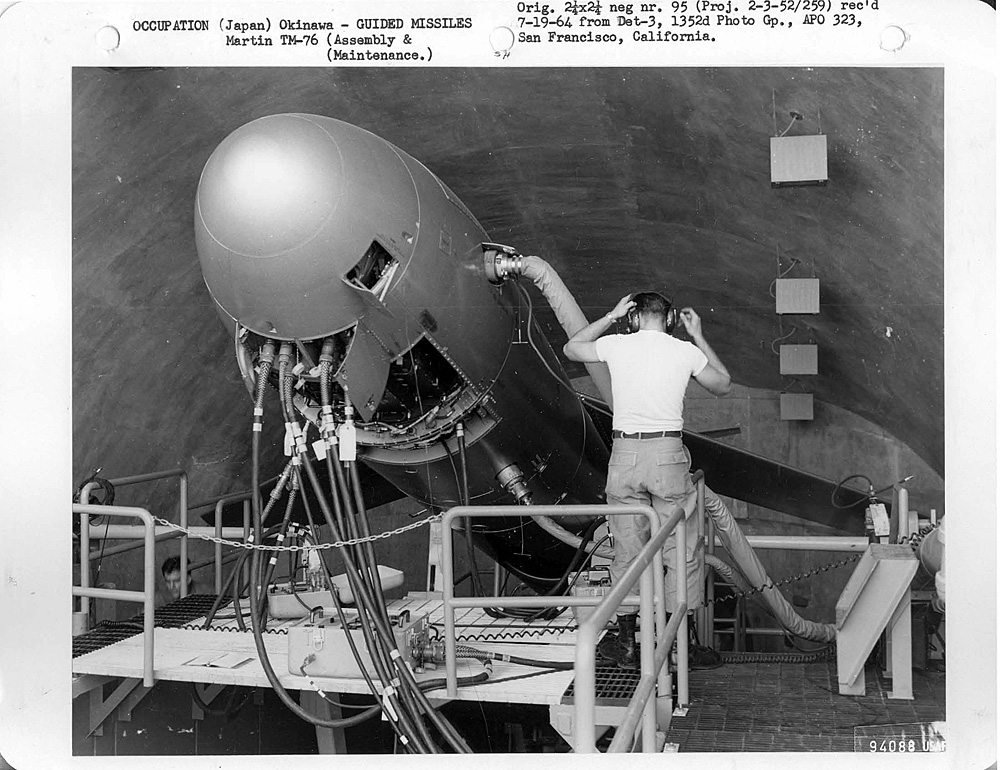

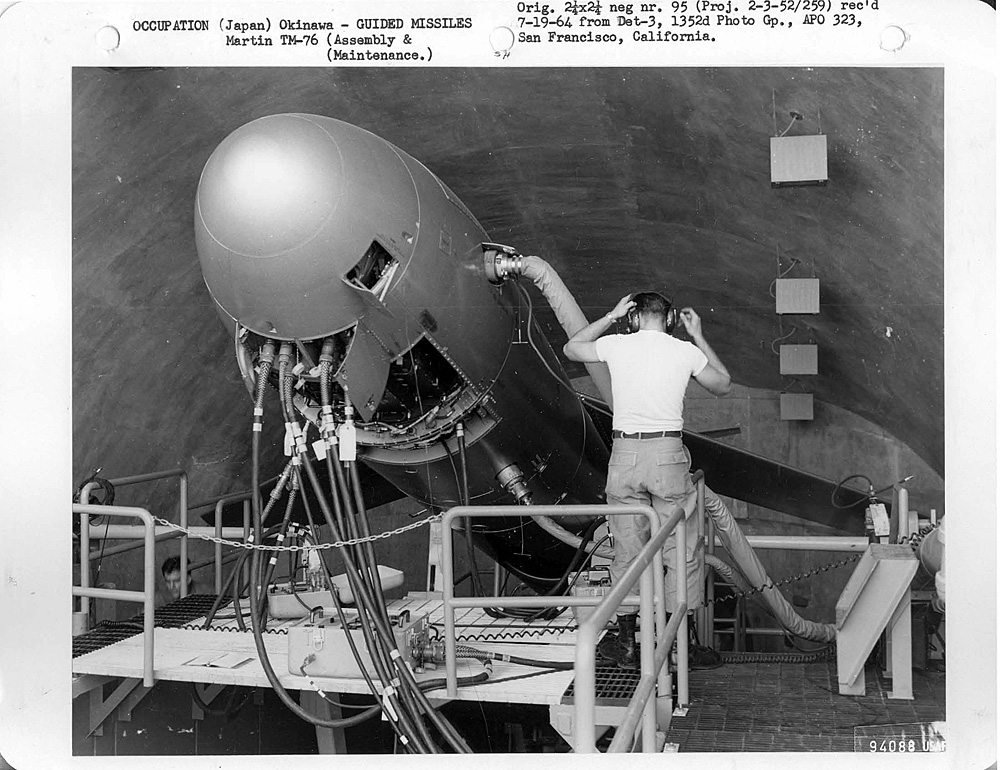

32 Mace Missiles were kept on constant nuclear alert in hardened hangars at four of the island's launch sites. The 280mm M65 Atomic Cannon nicknamed "Atomic Annie" and the projectiles it fired were also based here. Okinawa at one point hosted as many as 1,200 nuclear warheads. At the time, nuclear storage locations existed at Kadena AFB in Chibana and the hardened MGM-13 MACE missile launch sites; Naha AFB, Henoko amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_ amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab">Camp_Schwab.html"_;"title="amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab">amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab_and_the_MIM-14_Nike-Hercules.html" ;"title="Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab and the MIM-14 Nike-Hercules">Nike Hercules units on Okinawa.

32 Mace Missiles were kept on constant nuclear alert in hardened hangars at four of the island's launch sites. The 280mm M65 Atomic Cannon nicknamed "Atomic Annie" and the projectiles it fired were also based here. Okinawa at one point hosted as many as 1,200 nuclear warheads. At the time, nuclear storage locations existed at Kadena AFB in Chibana and the hardened MGM-13 MACE missile launch sites; Naha AFB, Henoko amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_ amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab">Camp_Schwab.html"_;"title="amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab">amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab_and_the_MIM-14_Nike-Hercules.html" ;"title="Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab and the MIM-14 Nike-Hercules">Nike Hercules units on Okinawa.

In June or July 1959, a MIM-14 Nike-Hercules anti-aircraft missile was accidentally fired from the Nike site 8 battery at Naha Air Base on Okinawa which according to some witnesses, was complete with a nuclear warhead. While the missile was undergoing continuity testing of the firing circuit, known as a squib test, stray voltage caused a short circuit in a faulty cable that was lying in a puddle and allowed the missile's rocket engines to ignite with the launcher still in a horizontal position. The Nike missile left the launcher and smashed through a fence and down into a beach area skipping the warhead out across the water "like a stone." The rocket's exhaust blast killed two Army technicians and injured one. A similar accidental launch of a Nike-H missile had occurred on April 14, 1955, at the W-25 site in

In June or July 1959, a MIM-14 Nike-Hercules anti-aircraft missile was accidentally fired from the Nike site 8 battery at Naha Air Base on Okinawa which according to some witnesses, was complete with a nuclear warhead. While the missile was undergoing continuity testing of the firing circuit, known as a squib test, stray voltage caused a short circuit in a faulty cable that was lying in a puddle and allowed the missile's rocket engines to ignite with the launcher still in a horizontal position. The Nike missile left the launcher and smashed through a fence and down into a beach area skipping the warhead out across the water "like a stone." The rocket's exhaust blast killed two Army technicians and injured one. A similar accidental launch of a Nike-H missile had occurred on April 14, 1955, at the W-25 site in

Finally, on November 19, 1968, a U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command (SAC) B-52 Stratofortress (registration number 55-01030) with a full bomb load, broke up and caught fire after the plane aborted takeoff at

Finally, on November 19, 1968, a U.S. Air Force Strategic Air Command (SAC) B-52 Stratofortress (registration number 55-01030) with a full bomb load, broke up and caught fire after the plane aborted takeoff at

The fire resulting from the aborted takeoff ignited the plane's fuel and detonated the plane's 30,000-pound (13,600 kg) bomb load, causing a blast so powerful that it created a crater under the burning aircraft some thirty feet deep and sixty feet across. The blast blew out the windows in the dispensary at Naha Air Base (now Naha Airport), away and damaged 139 houses. The plane was reduced "to a black spot on the runway". The blast was so large that Air Force spokesman had to announce that there had only been conventional bombs on board the plane. Nothing remained of the aircraft except the landing gear and engine assemblies, a few bombs, and some loose explosive that had not detonated. Very small fragments of aircraft metal from the enormous blast were "spread like confetti," leaving the crew to use a double entendre to refer to the cleanup work, calling it, "'52 Pickup." The planes Electronic Warfare Officer and the Crew Chief later died from burn injuries after being evacuated from Okinawa. Two Okinawan workers were also injured in the blasts.

Had the plane become airborne, only seconds later it would have crashed farther north of the runway and directly into the Chibana Ammunition Depot, which stored ammunition, bombs, high explosives, tens of thousands of artillery shells, and warheads for 19 different atomic and thermonuclear weapons systems in the hardened weapon storage areas. The depot held the Mark 28 nuclear bomb warheads used in the MGM-13 Mace cruise missile as well as warheads for nuclear tipped MGR-1 Honest John and MIM-14 Nike-Hercules (Nike-H) missiles. The depot also included 52 igloos in the Red Hat Storage Area containing Project Red Hat's

The fire resulting from the aborted takeoff ignited the plane's fuel and detonated the plane's 30,000-pound (13,600 kg) bomb load, causing a blast so powerful that it created a crater under the burning aircraft some thirty feet deep and sixty feet across. The blast blew out the windows in the dispensary at Naha Air Base (now Naha Airport), away and damaged 139 houses. The plane was reduced "to a black spot on the runway". The blast was so large that Air Force spokesman had to announce that there had only been conventional bombs on board the plane. Nothing remained of the aircraft except the landing gear and engine assemblies, a few bombs, and some loose explosive that had not detonated. Very small fragments of aircraft metal from the enormous blast were "spread like confetti," leaving the crew to use a double entendre to refer to the cleanup work, calling it, "'52 Pickup." The planes Electronic Warfare Officer and the Crew Chief later died from burn injuries after being evacuated from Okinawa. Two Okinawan workers were also injured in the blasts.

Had the plane become airborne, only seconds later it would have crashed farther north of the runway and directly into the Chibana Ammunition Depot, which stored ammunition, bombs, high explosives, tens of thousands of artillery shells, and warheads for 19 different atomic and thermonuclear weapons systems in the hardened weapon storage areas. The depot held the Mark 28 nuclear bomb warheads used in the MGM-13 Mace cruise missile as well as warheads for nuclear tipped MGR-1 Honest John and MIM-14 Nike-Hercules (Nike-H) missiles. The depot also included 52 igloos in the Red Hat Storage Area containing Project Red Hat's

"Rising Voices in S. Korea, Japan Advocate Nuclear Weapons."

Voanews.com. Retrieved on 11 May 2014. On 29 March 2016, then-U.S. President candidate Donald Trump suggested that Japan should develop its own nuclear weapons, claiming that it was becoming too expensive for the US to continue to protect Japan from countries such as China, North Korea, and Russia that already have their own nuclear weapons. On 27 February 2022, former prime minister Shinzo Abe proposed that Japan should consider a nuclear sharing arrangement with the US similar to NATO. This includes housing American nuclear weapons on Japanese soil for deterrence. This plan comes in the wake of the 2022 Russian invasion of Ukraine. Many Japanese politicians consider Vladimir Putin's threat to use nuclear weapons against a non-nuclear state to be a game changer. Abe wants to stimulate necessary debate:

Battle of Changde

The Battle of Changde (Battle of Changteh; ) was a major engagement in the Second Sino-Japanese War in and around the Chinese city of Changde (Changteh) in the province of Hunan. During the battle, the Imperial Japanese Army extensively used c ...

saw Japanese use of both bioweapons

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. Bi ...

and chemical weapons

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

, and the Japanese conducted a serious, though futile, nuclear weapon program.

Since World War II, the United States military based nuclear and chemical weapons and field tested biological anti-crop weapons in Japan.

Japan has since become a nuclear-capable state, said to be a "screwdriver's turn" away from nuclear weapons; having the capacity, the know-how, and the materials to make a nuclear bomb. Japan has consistently eschewed any desire to have nuclear weapons, and no mainstream Japanese party has ever advocated acquisition of nuclear weapons or any weapons of mass destruction. There are controversies on whether such weapons are forbidden by the Japanese constitution or not. Japan has signed many treaties prohibiting these kinds of weapons.

Japan is the only nation that has been attacked with atomic weapons. Prior to 1946 Japan carried out many attacks using weapons of mass destruction (chemical and biological), principally in China. In 1995, Japanese citizens released chemical weapons in Tokyo in a domestic terror attack.

Japanese possession of weapons of mass destruction

Bioweapons

Japan became interested in obtaining biological weapons during the early 1930s. Following an international ban on germ warfare in 1925 by the

Japan became interested in obtaining biological weapons during the early 1930s. Following an international ban on germ warfare in 1925 by the Geneva Protocol

The Protocol for the Prohibition of the Use in War of Asphyxiating, Poisonous or other Gases, and of Bacteriological Methods of Warfare, usually called the Geneva Protocol, is a treaty prohibiting the use of chemical and biological weapons in ...

Japan reasoned that disease epidemic

An epidemic (from Greek ἐπί ''epi'' "upon or above" and δῆμος ''demos'' "people") is the rapid spread of disease to a large number of patients among a given population within an area in a short period of time.

Epidemics of infectious ...

s must make effective weapons. Japan developed new methods of biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. ...

(BW) and used them on a large scale in China.

During the Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific The ...

and World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

, Unit 731

, short for Manshu Detachment 731 and also known as the Kamo Detachment and Ishii Unit, was a covert Biological warfare, biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that engaged in unethical h ...

and other Special Research Units of the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

conducted human experimentation on thousands, mostly Chinese, Korean, Russian, American, and other nationalities as well as some Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

criminals from the Japanese mainlands. In military campaigns, the Japanese army used biological weapons

A biological agent (also called bio-agent, biological threat agent, biological warfare agent, biological weapon, or bioweapon) is a bacterium, virus, protozoan, parasite, fungus, or toxin that can be used purposefully as a weapon in bioterrorism ...

on Chinese soldiers and civilians.

Japan's infamous biological warfare Unit 731 was led by Lt. General Shirō Ishii

Surgeon General was a Japanese microbiologist and army medical officer who served as the director of Unit 731, a biological warfare unit of the Imperial Japanese Army.

Ishii led the development and application of biological weapons at Unit 73 ...

.

Unit 731 used plague-infected flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, a ...

s and flies covered with cholera to infect the population in China.

The Japanese military dispersed insects by spraying them from low-flying airplanes and dropping ceramic bombs they had developed that were filled with mixtures containing insects and diseases that could affect humans, animals, and crops.Lockwood, Jeffrey A.Bug Bomb

, ''

The Boston Globe

''The Boston Globe'' is an American daily newspaper founded and based in Boston, Massachusetts. The newspaper has won a total of 27 Pulitzer Prizes, and has a total circulation of close to 300,000 print and digital subscribers. ''The Boston Glob ...

'', October 21, 2007, accessed December 23, 2008.

Localized and deadly epidemics resulted and an estimated 200,000 to 500,000 Chinese died of disease.Lockwood, Jeffrey A.Six-legged soldiers

, '' The Scientist'', October 24, 2008, accessed December 23, 2008.Novick, Lloyd and Marr, John S. ''Public Health Issues Disaster Preparedness'',

Google Books

, Jones & Bartlett Publishers, 2001, p. 87, (). Recent additional firsthand accounts testify the Japanese infected civilians through the distribution of plague-infested foodstuffs, such as dumplings and vegetables. During the

Changde chemical weapon attack

The Battle of Changde (Battle of Changteh; ) was a major engagement in the Second Sino-Japanese War in and around the Chinese city of Changde (Changteh) in the province of Hunan. During the battle, the Imperial Japanese Army extensively used c ...

s, the Japanese also employed biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. ...

by intentionally spreading infected fleas. In Zhejiang Province cholera, dysentery

Dysentery (UK pronunciation: , US: ), historically known as the bloody flux, is a type of gastroenteritis that results in bloody diarrhea. Other symptoms may include fever, abdominal pain, and a feeling of incomplete defecation. Complications ...

, and typhoid

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by ''Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several d ...

were employed. Harbin also suffered Japanese biological attacks. Other battles include the Kaimingye germ weapon attack in Ningbo.

Japan sent a submarine with unspecified biological weapons early in 1944 to defend the island of Saipan from American invasion; however the submarine was sunk.

Another attack against American troops with biological weapons was planned during the invasion of Iwo Jima. The planned involved towing gliders laden with pathogens

In biology, a pathogen ( el, πάθος, "suffering", "passion" and , "producer of") in the oldest and broadest sense, is any organism or agent that can produce disease. A pathogen may also be referred to as an infectious agent, or simply a ger ...

over the American lines. However, this plan never took shape. Had it succeeded, thousands of American soldiers and marines may have died, and the operation as a whole may very well have failed.

Japan's biowarfare experts had hoped to launch biological attacks on the U.S. in 1944 with balloon bombs filled with bubonic plague, anthrax, rinderpest, and smut fungus

The smuts are multicellular fungi characterized by their large numbers of teliospores. The smuts get their name from a Germanic word for dirt because of their dark, thick-walled, and dust-like teliospores. They are mostly Ustilaginomycetes (phylu ...

. A 1945-planned kamikaze

, officially , were a part of the Japanese Special Attack Units of military aviators who flew suicide attacks for the Empire of Japan against Allied naval vessels in the closing stages of the Pacific campaign of World War II, intending t ...

attack on San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United State ...

with I-400-class submarine aircraft carrier

A submarine aircraft carrier is a submarine equipped with aircraft for observation or attack missions. These submarines saw their most extensive use during World War II, although their operational significance remained rather small. The most fam ...

s that would deploy Aichi M6As floatplanes

A floatplane is a type of seaplane with one or more slender floats mounted under the fuselage to provide buoyancy. By contrast, a flying boat uses its fuselage for buoyancy. Either type of seaplane may also have landing gear suitable for land, ...

and drop flea

Flea, the common name for the order Siphonaptera, includes 2,500 species of small flightless insects that live as external parasites of mammals and birds. Fleas live by ingesting the blood of their hosts. Adult fleas grow to about long, a ...

s infected with bubonic plague was code-named Operation Cherry Blossoms at Night. The plans were rejected by Hideki Tojo who feared similar retaliation by the United States.

Japanese scientists from Unit 731 provided research information for the United States biological weapons program

The United States biological weapons program officially began in spring 1943 on orders from U.S. President Franklin Roosevelt. Research continued following World War II as the U.S. built up a large stockpile of biological agents and weapons. Over t ...

in order to escape war crimes charges. Bob Dohini, a former war crimes prosecution team lawyer, recently claimed that there was no mention of germ warfare in the investigation of war Japanese crimes. The fact was not well known until the 1980s. Japan's emperor was unable to be tried. Later revelations indicated his knowledge of the program.

Japan's employment of BW was largely viewed as ineffective, due to the absence of efficient production or delivery technology. The U.S. government provided a stipend

A stipend is a regular fixed sum of money paid for services or to defray expenses, such as for scholarship, internship, or apprenticeship. It is often distinct from an income or a salary because it does not necessarily represent payment for work p ...

to the Japanese BW military scientists and researches. Japanese biological warfare information provided to U.S. authorities after World War II remained a secret and was eventually returned to Japan.

Right-wing Japanese officials claim that no proof of Japan's wartime atrocities exists.

In August 2002, a Japanese court ended decades of official denials and acknowledged, for the first time, that Japan had used germ warfare in occupied China in the 1930s and 1940s. The court acknowledged the existence of Japan's biological warfare program but rejected the plaintiffs' demands for compensation, saying the issue was covered under postwar treaties. Following the court decision, Japanese officials announced that their government would send a delegation to China to excavate and remove hundreds of abandoned chemical weapons, including bombs, shells, and containers of mustard gas and other toxins left over from the Second World War.

Japan's biological warfare

Biological warfare, also known as germ warfare, is the use of biological toxins or infectious agents such as bacteria, viruses, insects, and fungi with the intent to kill, harm or incapacitate humans, animals or plants as an act of war. ...

experts and scientists from WWII, were alleged to have assisted the US in employment of BW in the Korean War.Sheldon H. Harris (3 May 2002). Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932-45, and the American Cover-up. Taylor & Francis.

Chemical weapons

TheJapanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

used mustard gas and the blister agent Lewisite against Chinese troops and guerillas in China, amongst others during the Changde chemical weapon attack

The Battle of Changde (Battle of Changteh; ) was a major engagement in the Second Sino-Japanese War in and around the Chinese city of Changde (Changteh) in the province of Hunan. During the battle, the Imperial Japanese Army extensively used c ...

.

Experiments involving chemical weapons were conducted on live prisoners ( Unit 516). As of 2005, sixty years after the end of the war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

, canisters that were abandoned by Japan in their hasty retreat are still being dug up in construction sites, causing injuries and allegedly even deaths.

Several chemical attacks on various people using VX gas and sarin and the Tokyo subway sarin attack on the Tokyo subway on March 20, 1995, were perpetrated by members of the cult movement Aum Shinrikyo

, formerly , is a Japanese doomsday cult founded by Shoko Asahara in 1987. It carried out the deadly Tokyo subway sarin attack in 1995 and was found to have been responsible for the Matsumoto sarin attack the previous year.

The group says ...

in acts of domestic terrorism

Domestic terrorism or homegrown terrorism is a form of terrorism in which victims "within a country are targeted by a perpetrator with the same citizenship" as the victims.Gary M. Jackson, ''Predicting Malicious Behavior: Tools and Techniques ...

. A large stockpile of other chemical agents and precursor chemicals were later found in raids on their facilities.

In 1995, JGSDF admitted possession of sarin samples for defense purposes.

Japan had signed the Chemical Weapons Convention in December 1993. Japan ratified The Chemical Weapons Convention in 1995 and was thus a state party upon it entering into force in 1997.

Nuclear weapons

AJapanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

program to develop nuclear weapon

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bom ...

s was conducted during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposing ...

. Like the German nuclear weapons program, it suffered from an array of problems, and was ultimately unable to progress beyond the laboratory stage before the atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki and the Japanese surrender in August 1945.

The postwar Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princ ...

forbids the establishment of offensive military forces, but not nuclear weapons explicitly. In 1967 it adopted the Three Non-Nuclear Principles, ruling out the production, possession, or introduction of nuclear weapons. Japan signed the Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons

The Treaty on the Non-Proliferation of Nuclear Weapons, commonly known as the Non-Proliferation Treaty or NPT, is an international treaty whose objective is to prevent the spread of nuclear weapons and weapons technology, to promote cooperation ...

in February 1970.Japan and the Nuclear Non-Proliferation TreatyGeorge H. Quester, ''Asian Survey'' Vol. 10, No. 9 (Sep., 1970), pp. 765-778, University of California Press. DOI: 10.2307/2643028 While there are currently no known plans in Japan to produce nuclear weapons, it has been argued that Japan has the technology, raw materials, and the capital to produce nuclear weapons within one year if necessary, and some analysts consider it a ''de facto'' nuclear state for this reason. For this reason Japan is often said to be a "screwdriver's turn" away from possessing nuclear weapons. During the 2016 U.S. presidential election it was proposed by

GOP

The Republican Party, also referred to as the GOP ("Grand Old Party"), is one of the Two-party system, two Major party, major contemporary political parties in the United States. The GOP was founded in 1854 by Abolitionism in the United Stat ...

candidates to allow both Japan and the Republic of Korea

South Korea, officially the Republic of Korea (ROK), is a country in East Asia, constituting the southern part of the Korean Peninsula and sharing a land border with North Korea. Its western border is formed by the Yellow Sea, while its ea ...

to develop nuclear weapons to counter a North Korean missile threat.

Delivery systems

Solid fuel rockets are the design of choice for military applications as they can remain in storage for long periods, and then reliably launch at short notice. Lawmakers made national security arguments for keeping Japan's solid-fuel rocket technology alive after ISAS was merged into the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency, which also has theH-IIA

H-IIA (H-2A) is an active expendable launch system operated by Mitsubishi Heavy Industries (MHI) for the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency. These liquid fuel rockets have been used to launch satellites into geostationary orbit; lunar o ...

liquid-fueled rocket, in 2003. The ISAS director of external affairs, Yasunori Matogawa, said, "It seems the hard-line national security proponents in parliament are increasing their influence, and they aren't getting much criticism…I think we’re moving into a very dangerous period. When you consider the current environment and the threat from North Korea, it’s scary."

Toshiyuki Shikata, a government adviser and former lieutenant general, indicated that part of the rationale for the fifth M-V Hayabusa

was a robotic spacecraft developed by the Japan Aerospace Exploration Agency (JAXA) to return a sample of material from a small near-Earth asteroid named 25143 Itokawa to Earth for further analysis.

''Hayabusa'', formerly known as MUSES-C fo ...

mission was that the reentry and landing of its return capsule demonstrated "that Japan's ballistic missile capability is credible."

At a technical level the M-V design could be weaponised quickly (as an Intercontinental ballistic missile) although this would be politically unlikely.

In response to the perceived threat from North Korean-launched ballistic missiles, Japanese government officials have proposed developing a first strike capability for Japan's military that includes ballistic and cruise missiles.

North Korean weapons of mass destruction and Japan

The threat ofNorth Korea

North Korea, officially the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (DPRK), is a country in East Asia. It constitutes the northern half of the Korean Peninsula and shares borders with China and Russia to the north, at the Yalu (Amnok) and T ...

-based ballistic missiles that are within range of Japan have guided Japanese and U.S. defense and deterrence strategies.

South Korean weapons of mass destruction and Japan

South Korean interest in developing an atomic bomb began in 1950. The interest was partially a result of the rapid surrender of Korea's then-enemy Japan following use of atomic bombs in World War II. Post-war aggression from the North and from thePeople's Republic of China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

solidified that interest. A South Korean nuclear facility began to reprocess fuel and enrich plutonium based on the observation that Japan was also producing it.

In late 1958, nuclear weapons were deployed by the U.S. from Kadena Air Base

(IATA: DNA, ICAO: RODN) is a highly strategic United States Air Force base in the towns of Kadena and Chatan and the city of Okinawa, in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. It is often referred to as the "Keystone of the Pacific" because of its highl ...

in Okinawa to Kunsan Air Base

Kunsan K-8 Air Base is a United States Air Force base located at Gunsan Airport, on the west coast of the South Korean peninsula bordered by the Yellow Sea. It is located in the town of Gunsan (also romanized as Kunsan), about south of Seoul.

...

in South Korea in order to oppose military actions by the People's Republic of China during the Second Taiwan Strait Crisis

The Second Taiwan Strait Crisis, also called the 1958 Taiwan Strait Crisis, was a conflict that took place between the People's Republic of China (PRC) and the Republic of China (ROC). In this conflict, the PRC shelled the islands of Kinm ...

.

U.S. weapons of mass destruction and Japan

Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

has long been viewed as a stepping-stone to force open the remainder of Japan and Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an are ...

. Commodore Perry's gunboat diplomacy

In international politics, the term gunboat diplomacy refers to the pursuit of foreign policy objectives with the aid of conspicuous displays of naval power, implying or constituting a direct threat of warfare should terms not be agreeable to t ...

expedition to open Japan to U.S. trade began in Okinawa in 1852.

By the early 1950s and the outbreak of the Korean War, Okinawa was seen as America's Gibraltar

)

, anthem = " God Save the King"

, song = " Gibraltar Anthem"

, image_map = Gibraltar location in Europe.svg

, map_alt = Location of Gibraltar in Europe

, map_caption = United Kingdom shown in pale green

, mapsize =

, image_map2 = Gib ...

of the Pacific.Gibraltar of the Pacific(March 10, 1952) ''The Pittsburgh Press'', Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Page 15.

U.S. bioweapons and Japan

In 1939, the U.S. State Department reported that a Japanese Army physician inNew York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the most densely populated major city in the Un ...

had attempted to obtain a Yellow fever

Yellow fever is a viral disease of typically short duration. In most cases, symptoms include fever, chills, loss of appetite, nausea, muscle pains – particularly in the back – and headaches. Symptoms typically improve within five days. ...

virus sample from the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research

The Rockefeller University is a private biomedical research and graduate-only university in New York City, New York. It focuses primarily on the biological and medical sciences and provides doctoral and postdoctoral education. It is classi ...

. The incident contributed to a sense of urgency in the United States to research a BW capability. By 1942 George W. Merck

George Wilhelm Herman Emanuel Merck (March 29, 1894 – November 9, 1957) was the president of Merck & Co. from 1925 to 1950 and a member of the Merck family.

Early life

George W. Merck was born in New York City, to George Friedrich and Fri ...

, president of Merck and Company, was made chairman of the War Research Service The War Research Service (WRS) was a civilian agency of the United States government established during World War II to pursue research relating to biological warfare. Established in May 1942 by Secretary of War Henry L. Stimson, the WRS was embed ...

which was established to oversee the U.S. development of BW-related technology at Camp Detrick.

After World War II ended, a U.S. War Departments report notes that "in addition to the results of human experimentation much data is available from the Japanese experiments on animals and food crops".U.S. War Department, War Crimes Office Report (undated), retrieved: January 17, 2014/ref> The technical information of Japan's BW program participants was transferred into U.S. intelligence agencies and BW programs in exchange for immunity for war crimes charges.

Korean War allegations

In 1951, the first of many allegations were made against the United States by the communist belligerent nations in the Korean war of employing biological warfare using various techniques in attacks launched from bases on Okinawa.U.S. anti-plant biological weapons research

In 1945 Japan's rice crop was terribly affected by rice blast disease. The outbreak as well as another in Germany's potato crop coincided with covert Allied research in these areas. The timing of these outbreaks generated persistent speculation of some connection between the events however the rumors were never proven and the outbreaks could have been naturally occurring. Sheldon H. Harris in ''Factories of Death: Japanese Biological Warfare, 1932–1945, and the American Cover Up'' wrote:U.S. anti-plant chemical agents research

During the Second World War limited test use of aerial spray delivery systems was employed only on several Japanese-controlled tropical islands to demarcate points for navigation and to kill dense island foliage. Despite the availability of the spray equipment, herbicide application with aerial chemical delivery systems were not systematically implemented in the Pacific theater during the war. At the close of World War Two, the U.S. planned to attack Japan's food supply with anti-crop chemical agents and by July 1945 had stockpiled an amount of chemicals "sufficient to destroy one-tenth of the rice crop of Japan."Walsh, Liam (December 7, 2011)"World War II plan to poison Japanese crops revealed"

THE COURIER-MAIL. Australia. Retrieved October 10, 2015. Archive date April 14, 2012. However, logistical problems would have reduced that estimate. In addition to work done in the anti-crop theater during the Cold War, the screening program for chemical defoliants was greatly accelerated. By the end of fiscal year 1962, the Chemical Corps had let or were negotiating contracts for over one thousand chemical defoliants. "The Okinawa tests evidently were fruitful." The presence of so-called rainbow herbicides such as Agent Orange has been widely reported on Okinawa as well as at other locations in Japan. The U.S. government disputes these assertions and the issues surrounding the subject of military use anti-plant agents in Japan during the 1950s through the 1970s remains a controversy.

Arthropod vector research

At Kadena Air Force Base, an Entomology Branch of the U.S. Army Preventive Medicine Activity, U.S. Army Medical Center was used to grow "medically important" arthropods, including many strains of mosquitoes in a study of disease vector efficiency. The program reportedly supported a research program studying taxonomic and ecological data surveys for theSmithsonian Institution

The Smithsonian Institution ( ), or simply the Smithsonian, is a group of museums and education and research centers, the largest such complex in the world, created by the U.S. government "for the increase and diffusion of knowledge". Founded ...

."

The Smithsonian Institution and The National Academy of Sciences and National Research Council National Research Council may refer to:

* National Research Council (Canada), sponsoring research and development

* National Research Council (Italy), scientific and technological research, Rome

* National Research Council (United States), part of ...

administered special research projects in the Pacific. The Far East Section of the Office of the Foreign Secretary administered two such projects which focused "on the flora of Okinawa" and "trapping of airborne insects and arthropods for the study of the natural dispersal of insects and arthropods over the ocean." The motivation for civilian research programs of this nature was questioned when it was learned that such international research was in fact funded by and provided to the U.S. Army as requirement related to the U.S. military's biological warfare research.

Weather modification research

Operation Pop Eye / Motorpool / Intermediary-Compatriot was a highly classified weather modification program in Southeast Asia during 1967-1972 that was developed from cloud seeding research conducted on Okinawa and other tropical locations. A report titled ''Rainmaking in SEASIA'' outlines use of silver iodide deployed by aircraft in a program that was developed inCalifornia

California is a state in the Western United States, located along the Pacific Coast. With nearly 39.2million residents across a total area of approximately , it is the most populous U.S. state and the 3rd largest by area. It is also the m ...

at Naval Air Weapons Station China Lake. The technique was refined and tested in Okinawa, Guam

Guam (; ch, Guåhan ) is an organized, unincorporated territory of the United States in the Micronesia subregion of the western Pacific Ocean. It is the westernmost point and territory of the United States (reckoned from the geographic cent ...

, Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2020, it is the second-largest U.S. state by ...

, and Florida

Florida is a state located in the Southeastern region of the United States. Florida is bordered to the west by the Gulf of Mexico, to the northwest by Alabama, to the north by Georgia, to the east by the Bahamas and Atlantic Ocean, and to ...

in a hurricane study program called Project Stormfury

Project Stormfury was an attempt to weaken tropical cyclones by flying aircraft into them and seeding with silver iodide. The project was run by the United States Government from 1962 to 1983. The hypothesis was that the silver iodide would cause ...

.

The chemical weather modification program was conducted from Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is b ...

over Cambodia

Cambodia (; also Kampuchea ; km, កម្ពុជា, UNGEGN: ), officially the Kingdom of Cambodia, is a country located in the southern portion of the Indochinese Peninsula in Southeast Asia, spanning an area of , bordered by Thailan ...

, Laos, and Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

. The program was allegedly sponsored by Secretary of State Henry Kissinger

Henry Alfred Kissinger (; ; born Heinz Alfred Kissinger, May 27, 1923) is a German-born American politician, diplomat, and geopolitical consultant who served as United States Secretary of State and National Security Advisor under the presid ...

and the Central Intelligence Agency

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

without the authorization of Secretary of Defense Melvin Laird. Laird had categorically denied to Congress that a program for modification of the weather existed. The program employed cloud seeding as a weapon which was used to induce rain and extend the East Asian Monsoon season in support of U.S. government strategic efforts related to the War in Southeast Asia. The use of a military weather control program was related to the destruction of enemy food crops. Whether the use of a weather modification program was directly related to any of the chemical and biological warfare programs is not documented. However, it is certain that some of the military herbicides in use in Vietnam required rainfall to be absorbed.

In theory, any CBW program employing fungus spores or a mosquito vector would have also benefited from prolonged periods of rain. Rice blast sporulation

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, ...

on diseased leaves occurs when relative humidity approaches 100%. Laboratory measurements indicate sporulation

In biology, a spore is a unit of sexual or asexual reproduction that may be adapted for dispersal and for survival, often for extended periods of time, in unfavourable conditions. Spores form part of the life cycles of many plants, algae, ...

increases with the length of time 100% relative humidity prevails.

The ''Aedes aegypti

''Aedes aegypti'', the yellow fever mosquito, is a mosquito that can spread dengue fever, chikungunya, Zika fever, Mayaro and yellow fever viruses, and other disease agents. The mosquito can be recognized by black and white markings on its le ...

'' mosquito lays eggs and requires standing water to reproduce. Approximately three days after it feeds on blood, the mosquito lays her eggs over a period of several days. The eggs are resistant to desiccation and can survive for periods of six or more months. When rain floods the eggs with water, the larvae hatch.

U.S. chemical weapons and Japan

U.S. chemical weapons in Japan were deployed to Okinawa in the early 1950s. The Red Hat mission deployed additional chemical agents in threemilitary operation

A military operation is the coordinated military actions of a state, or a non-state actor, in response to a developing situation. These actions are designed as a military plan to resolve the situation in the state or actor's favor. Operations ma ...

s code named YBA, YBB, and YBF. The operation deployed chemical agents to the 267th Chemical Platoon on Okinawa

is a prefecture of Japan. Okinawa Prefecture is the southernmost and westernmost prefecture of Japan, has a population of 1,457,162 (as of 2 February 2020) and a geographic area of 2,281 km2 (880 sq mi).

Naha is the capital and largest city ...

during the early 1960s under Project 112

Project 112 was a biological and chemical weapon experimentation project conducted by the United States Department of Defense from 1962 to 1973.

The project started under John F. Kennedy's administration, and was authorized by his Secretary ...

.Mitchell, Jon,'Were we marines used as guinea pigs on Okinawa?'

" '' Japan Times'', 4 December 2012, p. 14 The shipments, according to declassified documents, included sarin, VX, and mustard gas. By 1969, according to later newspaper reports, there was an estimated 1.9 million kg (1,900 metric tons) of VX stored on Okinawa. The chemical weapons brought to Okinawa included nerve and blister agents contained in rockets, artillery shells, bombs, mines, and one-ton (900 kg) containers. The chemicals were stored at Chibana Ammunition Depot. The depot was a hill-top installation next to

Kadena Air Base

(IATA: DNA, ICAO: RODN) is a highly strategic United States Air Force base in the towns of Kadena and Chatan and the city of Okinawa, in Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. It is often referred to as the "Keystone of the Pacific" because of its highl ...

.

In 1969, over 20 servicemen (23 U.S. soldier

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, or an officer.

Etymology

The word ''soldier'' derives from the Middle English word , from Old French ...

s and one U.S. civilian

Civilians under international humanitarian law are "persons who are not members of the armed forces" and they are not " combatants if they carry arms openly and respect the laws and customs of war". It is slightly different from a non-combatant ...

, according to other reports) were exposed to low levels of the nerve agent sarin while sandblasting and repainting storage containers. The resultant publicity appears to have contributed to the decision to move the weapons off Okinawa.

The U.S. then government directed relocation of chemical munitions. The chemical warfare agents were removed from Okinawa in 1971 during Operation Red Hat. Operation Red Hat involved the removal of chemical warfare munitions from Okinawa to Johnston Atoll in the Central Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the contin ...

.NARA. Operation Red Hat: Men and a mission (1971)/ref> An official U.S. film on the mission says that 'safety was the primary concern during the operation,' though Japanese resentment of U.S. military activities on Okinawa also complicated the situation. At the technical level, time pressures imposed to complete the mission, the heat, and water rationing problems also complicated the planning. The initial phase of Operation Red Hat involved the movement of chemical munitions from a depot storage site to Tengan Pier, eight miles away, and required 1,332 trailers in 148 convoys. The second phase of the operation moved the munitions to Johnston Atoll. The

Army

An army (from Old French ''armee'', itself derived from the Latin verb ''armāre'', meaning "to arm", and related to the Latin noun ''arma'', meaning "arms" or "weapons"), ground force or land force is a fighting force that fights primarily on ...

leased on Johnston. Phase I of the operation took place in January and moved 150 tons of distilled mustard agent. The arrived at Johnston Atoll with the first load of projectiles on January 13, 1971. Phase II completed cargo discharge to Johnston Atoll with five moves of the remaining 12,500 tons of munitions, in August and September 1971.

Units operating under United States Army Ryukyu Islands (USARYIS) were 2nd Logistical Command and the 267th Chemical Company, the 5th and 196th Ordnance Detachments (EOD), and the 175th Ordnance Detachment.

Originally, it was planned that the munitions be moved to Umatilla Chemical Depot but this never happened due to public opposition and political pressure. The Congress

A congress is a formal meeting of the representatives of different countries, constituent states, organizations, trade unions, political parties, or other groups. The term originated in Late Middle English to denote an encounter (meeting of ...

passed legislation on January 12, 1971 (PL 91-672) that prohibited the transfer of nerve agent

Nerve agents, sometimes also called nerve gases, are a class of organic chemicals that disrupt the mechanisms by which nerves transfer messages to organs. The disruption is caused by the blocking of acetylcholinesterase (AChE), an enzyme that ...

, mustard agent, agent orange and other chemical munitions to all 50 U.S. states.

In 1985 the U.S. Congress mandated that all chemical weapons stockpiled at Johnston Atoll, mostly mustard gas, Sarin, and VX gas, be destroyed. Prior to the beginning of destruction operations, Johnston Atoll held about 6.6 percent of the entire U.S. stockpile of chemical weapon

A chemical weapon (CW) is a specialized munition that uses chemicals formulated to inflict death or harm on humans. According to the Organisation for the Prohibition of Chemical Weapons (OPCW), this can be any chemical compound intended as a ...

s.

The Johnston Atoll Chemical Agent Disposal System (JACADS) was built to destroy all the chemical munitions stored on Johnston island. The first weapon disposal incineration operation took place on June 30, 1990. The last munitions were destroyed in 2000.

U.S. nuclear weapons and Japan

The intensity of the fighting and the high number of casualties during the Battle of Okinawa formed the basis of the casualty estimates projected for the invasion of Japan that led to the decision to launch the atomic bombing of Japan.Atomic bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

were deployed in order to avoid having “another

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

Okinawa from one end of Japan to the other.”

The atomic age on Japan's southern islands began during the final weeks of the war when the U.S. Army Air Force launched two atomic attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

from bases on Tinian

Tinian ( or ; old Japanese name: 天仁安島, ''Tenian-shima'') is one of the three principal islands of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands. Together with uninhabited neighboring Aguiguan, it forms Tinian Municipality, one of the ...

in the Marianas Islands

The Mariana Islands (; also the Marianas; in Chamorro: ''Manislan Mariånas'') are a crescent-shaped archipelago comprising the summits of fifteen longitudinally oriented, mostly dormant volcanic mountains in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, betw ...

. Bockscar, the B-29 that dropped the Fat Man

"Fat Man" (also known as Mark III) is the codename for the type of nuclear bomb the United States detonated over the Japanese city of Nagasaki on 9 August 1945. It was the second of the only two nuclear weapons ever used in warfare, the fir ...

nuclear weapon on Nagasaki

is the capital and the largest Cities of Japan, city of Nagasaki Prefecture on the island of Kyushu in Japan.

It became the sole Nanban trade, port used for trade with the Portuguese and Dutch during the 16th through 19th centuries. The Hi ...

, landed at Yontan Airfield on Okinawa on August 9, 1945. The U.S. military immediately began constructing a second B-29 base and a facility for atom bomb processing in Okinawa to be completed in September 1945 that would open more targets in mainland Japan.

U.S. nuclear weapon atmospheric testing

Japanese naval warships captured by the U.S. after Japan's surrender in World War II, including the ''Nagato'', were used as target ships and destroyed in 1946 innuclear testing at Bikini Atoll

Nuclear testing at Bikini Atoll consisted of the detonation of 23 nuclear weapons by the United States between 1946 and 1958 on Bikini Atoll in the Marshall Islands. Tests occurred at 7 test sites on the reef itself, on the sea, in the air, ...

during Operation Crossroads

Operation Crossroads was a pair of nuclear weapon tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll in mid-1946. They were the first nuclear weapon tests since Trinity in July 1945, and the first detonations of nuclear devices since the ...

. The atomic testing was conducted in the Marshall Islands

The Marshall Islands ( mh, Ṃajeḷ), officially the Republic of the Marshall Islands ( mh, Aolepān Aorōkin Ṃajeḷ),'' () is an independent island country and microstate near the Equator in the Pacific Ocean, slightly west of the Intern ...

group that U.S. forces captured in early 1944 from the Japanese.

The first hydrogen bomb detonation, known as Castle Bravo

Castle Bravo was the first in a series of high-yield thermonuclear weapon design tests conducted by the United States at Bikini Atoll, Marshall Islands, as part of '' Operation Castle''. Detonated on March 1, 1954, the device was the most powerful ...

, contaminated

Contamination is the presence of a constituent, impurity, or some other undesirable element that spoils, corrupts, infects, makes unfit, or makes inferior a material, physical body, natural environment, workplace, etc.

Types of contamination

...

Japanese fisherman on the '' Daigo Fukuryū Maru'' with nuclear fallout

Nuclear fallout is the residual radioactive material propelled into the upper atmosphere following a nuclear blast, so called because it "falls out" of the sky after the explosion and the shock wave has passed. It commonly refers to the radioac ...

on March 4, 1954. The incident further rallied a powerful anti-nuclear movement.

Nuclear weapons agreements

Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution, written by MacArthur immediately after the war, does not explicitly prohibit nuclear weapons. But when the U.S. military occupation of Japan ended in 1951, a new security treaty was signed that granted the United States rights to base its "land, sea, and air forces in and about Japan." In 1959, Prime Minister Nobusuke Kishi stated that Japan would neither develop nuclear weapons nor permit them on its territory". He instituted the Three Non-Nuclear Principles--"no production, no possession, and no introduction." A 1960 accord with Japan permits the United States to move weapons of mass destruction through Japanese territory and allows American warships and submarines to carry nuclear weapons into Japan's ports and American aircraft to bring them in during landings. The discussion took place during negotiations in 1959, and the agreement was made in 1960 by Aiichiro Fujiyama, then Japan's Foreign Minister. "There were many things left unsaid; it was a very sophisticated negotiation. The Japanese are masters at understood and unspoken communication in which one is asked to draw inferences from what may not be articulated." The secret agreement was concluded without any Japanese text so that it could be plausibly denied in Japan. Since only the American officials recorded the oral agreement, not having the agreement recorded in Japanese allowed Japan's leaders to deny its existence without fear that someone would leak a document to prove them wrong. The arrangement also made it appear that the United States alone was responsible for the transit of nuclear munitions through Japan. However, the original agreement document turned up in 1969 during preparation for an updated agreement, when a memorandum was written by a group of U.S. officials from the National Security Council Staff; the Departments of State, Defense, Army, Commerce and Treasury; the Joint Chiefs of Staff; the Central Intelligence Agency; and the

The secret agreement was concluded without any Japanese text so that it could be plausibly denied in Japan. Since only the American officials recorded the oral agreement, not having the agreement recorded in Japanese allowed Japan's leaders to deny its existence without fear that someone would leak a document to prove them wrong. The arrangement also made it appear that the United States alone was responsible for the transit of nuclear munitions through Japan. However, the original agreement document turned up in 1969 during preparation for an updated agreement, when a memorandum was written by a group of U.S. officials from the National Security Council Staff; the Departments of State, Defense, Army, Commerce and Treasury; the Joint Chiefs of Staff; the Central Intelligence Agency; and the United States Information Agency

The United States Information Agency (USIA), which operated from 1953 to 1999, was a United States agency devoted to " public diplomacy". In 1999, prior to the reorganization of intelligence agencies by President George W. Bush, President Bil ...

.

A 1963 Central Intelligence Agency National Intelligence Estimate stated that: '...US bases in Japan and related problems of weapons and forces will continue to involve issues of great sensitivity in Japan-US relations. The government is bound to be responsive to the popular pressures which the left can whip up on these issues. We do not believe that this situation will lead to demands by any conservative government for evacuation of the bases.'

During the early parts of the Cold War the Bonin Islands

The Bonin Islands, also known as the , are an archipelago of over 30 subtropical and tropical islands, some directly south of Tokyo, Japan and northwest of Guam. The name "Bonin Islands" comes from the Japanese word ''bunin'' (an archaic read ...

including Chichi Jima

, native_name_link =

, image_caption = Map of Chichijima, Anijima and Otoutojima

, image_size =

, pushpin_map = Japan complete

, pushpin_label = Chichijima

, pushpin_label_position =

, pushpin_map_alt =

, ...

, the Ryukyu Islands

The , also known as the or the , are a chain of Japanese islands that stretch southwest from Kyushu to Taiwan: the Ōsumi, Tokara, Amami, Okinawa, and Sakishima Islands (further divided into the Miyako and Yaeyama Islands), with Yona ...

including Okinawa, and the Volcano Islands including Iwo Jima were retained under American control. The islands were among "thirteen separate locations in Japan that had nuclear weapons or components, or were earmarked to receive nuclear weapons in times of crisis or war." According to a former U.S. Air Force officer stationed on Iwo Jima, the island would have served as a recovery facility for bombers after they had dropped their bombs in the Soviet Union or China. War planners reasoned that bombers could return Iwo Jima, "where they would be refueled, reloaded, and readied to deliver a second salvo as an assumption was that the major U.S. Bases in Japan and the Pacific theater would be destroyed in a nuclear war." It was believed by war planners that a small base might evade destruction and be a safe harbor for surviving submarines to reload. Supplies to re-equip submarines as well as Anti-submarine weapons

An anti-submarine weapon (ASW) is any one of a number of devices that are intended to act against a submarine and its crew, to destroy (sink) the vessel or reduce its capability as a weapon of war. In its simplest sense, an anti-submarine weapo ...

were stored within caves on Chichi Jima. The Johnson administration gradually realized that it would be forced to return Chichi Jima and Iwo Jima "to delay reversion of the more important Okinawa bases" however, President Johnson also wanted Japan's support for U.S. Military operations in Southeast Asia." The Bonin and Volcano islands were eventually returned to Japan in June 1968.

Prime Minister Eisaku Satō

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister from 1964 to 1972. He is the third-longest serving Prime Minister, and ranks second in longest uninterrupted service as Prime Minister.

Satō entered the National Diet in 1949 as a membe ...

and Foreign Minister Takeo Miki

was a Japanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Japan from 1974 until 1976.

Early life and family

Takeo Miki was born on 17 March 1907, in Gosho, Tokushima Prefecture (present-day Awa, Tokushima), the only child of farmer-merchant ...

had explained to the Japanese parliament that "the return of the Bonins had nothing to do with nuclear weapons yet the final agreement included a secret annex, and its exact wording remained classified." A December 30, 1968, cable from the U.S. embassy in Tokyo is titled "Bonin Agreement Nuclear Storage," but within the same file "the National Archives contains a 'withdrawal sheet' for an attached Tokyo cable dated April 10, 1968, titled 'Bonins Agreement--Secret Annex,'".

On the one year anniversary of the B-52 crash and explosion at Kadena Prime Minister Sato and President Nixon met in Washington, DC where several agreements including a revised Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) and a formal policy related to the future deployment of nuclear weapons on Okinawa were reached.

A draft of the November 21st, 1969, ''Agreed Minute to Joint Communique of United States President Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato'' was found in 1994. "The existence of this document has never been officially recognized by the Japanese or U.S. governments." The English text of the draft agreement reads:

United States President:

Japanese Prime Minister:

On the one year anniversary of the B-52 crash and explosion at Kadena Prime Minister Sato and President Nixon met in Washington, DC where several agreements including a revised Status of Forces Agreement (SOFA) and a formal policy related to the future deployment of nuclear weapons on Okinawa were reached.

A draft of the November 21st, 1969, ''Agreed Minute to Joint Communique of United States President Nixon and Japanese Prime Minister Sato'' was found in 1994. "The existence of this document has never been officially recognized by the Japanese or U.S. governments." The English text of the draft agreement reads:

United States President:

Japanese Prime Minister:

Alleged nuclear weapons incidents on Okinawa

Complete information surrounding U.S.nuclear accidents

A nuclear and radiation accident is defined by the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) as "an event that has led to significant consequences to people, the environment or the facility. Examples include lethal effects to individuals, lar ...

is not generally available via official channels. News of accidents on the island usually did not reach much farther than the islands local news, protest groups, eyewitnesses and rumor mills. However, the incidents that were publicized garnered international opposition to chemical and nuclear weapons and set the stage for the 1971 Okinawa Reversion Agreement to officially ending the U.S. military occupation on Okinawa.

32 Mace Missiles were kept on constant nuclear alert in hardened hangars at four of the island's launch sites. The 280mm M65 Atomic Cannon nicknamed "Atomic Annie" and the projectiles it fired were also based here. Okinawa at one point hosted as many as 1,200 nuclear warheads. At the time, nuclear storage locations existed at Kadena AFB in Chibana and the hardened MGM-13 MACE missile launch sites; Naha AFB, Henoko amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_ amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab">Camp_Schwab.html"_;"title="amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab">amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab_and_the_MIM-14_Nike-Hercules.html" ;"title="Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab and the MIM-14 Nike-Hercules">Nike Hercules units on Okinawa.

32 Mace Missiles were kept on constant nuclear alert in hardened hangars at four of the island's launch sites. The 280mm M65 Atomic Cannon nicknamed "Atomic Annie" and the projectiles it fired were also based here. Okinawa at one point hosted as many as 1,200 nuclear warheads. At the time, nuclear storage locations existed at Kadena AFB in Chibana and the hardened MGM-13 MACE missile launch sites; Naha AFB, Henoko amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_ amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab">Camp_Schwab.html"_;"title="amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab">amp_Henoko_(Ordnance_Ammunition_Depot)_at_Camp_Schwab_and_the_MIM-14_Nike-Hercules.html" ;"title="Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">Camp_Schwab.html" ;"title="amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab">amp Henoko (Ordnance Ammunition Depot) at Camp Schwab and the MIM-14 Nike-Hercules">Nike Hercules units on Okinawa.

In June or July 1959, a MIM-14 Nike-Hercules anti-aircraft missile was accidentally fired from the Nike site 8 battery at Naha Air Base on Okinawa which according to some witnesses, was complete with a nuclear warhead. While the missile was undergoing continuity testing of the firing circuit, known as a squib test, stray voltage caused a short circuit in a faulty cable that was lying in a puddle and allowed the missile's rocket engines to ignite with the launcher still in a horizontal position. The Nike missile left the launcher and smashed through a fence and down into a beach area skipping the warhead out across the water "like a stone." The rocket's exhaust blast killed two Army technicians and injured one. A similar accidental launch of a Nike-H missile had occurred on April 14, 1955, at the W-25 site in

In June or July 1959, a MIM-14 Nike-Hercules anti-aircraft missile was accidentally fired from the Nike site 8 battery at Naha Air Base on Okinawa which according to some witnesses, was complete with a nuclear warhead. While the missile was undergoing continuity testing of the firing circuit, known as a squib test, stray voltage caused a short circuit in a faulty cable that was lying in a puddle and allowed the missile's rocket engines to ignite with the launcher still in a horizontal position. The Nike missile left the launcher and smashed through a fence and down into a beach area skipping the warhead out across the water "like a stone." The rocket's exhaust blast killed two Army technicians and injured one. A similar accidental launch of a Nike-H missile had occurred on April 14, 1955, at the W-25 site in Davidsonville, Maryland

Davidsonville is an unincorporated community in central Anne Arundel County, Maryland, United States. It is a semi-rural community composed mostly of farms and suburban-like developments and is a good example of an "exurb." Davidsonville has rela ...

, which is near the National Security Agency

The National Security Agency (NSA) is a national-level intelligence agency of the United States Department of Defense, under the authority of the Director of National Intelligence (DNI). The NSA is responsible for global monitoring, collect ...

headquarters at Fort George G. Meade

Fort George G. Meade is a United States Army installation located in Maryland, that includes the Defense Information School, the Defense Media Activity, the United States military bands#Army Field Band, United States Army Field Band, and the head ...

.

On October 28, 1962, during the peak of Cuban Missile Crisis U.S. Strategic Forces were at Defense Condition Two or DEFCON 2. According to missile technicians who witnessed events, the four MACE B missile sites on Okinawa erroneously received coded launch orders to fire all of their 32 nuclear cruise missiles

A cruise missile is a guided missile used against terrestrial or naval targets that remains in the atmosphere and flies the major portion of its flight path at approximately constant speed. Cruise missiles are designed to deliver a large warhe ...

at the Soviets and their allies. Quick thinking by Capt. William Bassett who questioned whether the order was "the real thing, or the biggest screw up we will ever experience in our lifetime” delayed the orders to launch until the error was realized by the missile operations center. According to witness John Bordne, Capt. Bassett was the senior field officer commanding the missiles and was nearly forced to have a subordinate lieutenant who was intent on following the orders to launch his missiles shot by armed security guards. No U.S. Government record of this incident has ever been officially released. Former missileers have refuted Bordne's account.

Next, on December 5, 1965, off of the coast of Okinawa, an A-4 Skyhawk

The Douglas A-4 Skyhawk is a single-seat subsonic carrier-capable light attack aircraft developed for the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps in the early 1950s. The delta-winged, single turbojet engined Skyhawk was designed ...

attack aircraft rolled off of an elevator of the aircraft carrier USS Ticonderoga (CV-14) into 16,000 feet of water resulting in the loss of the pilot, the aircraft, and the B43 nuclear bomb