James Baldwin (politician) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

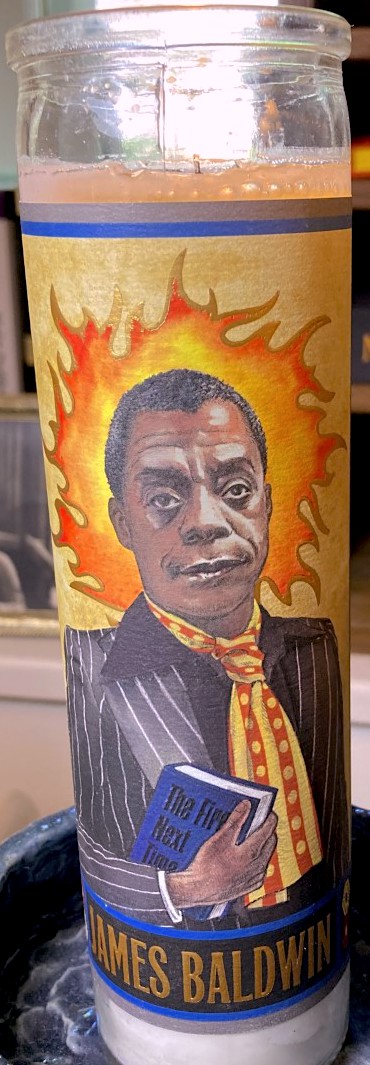

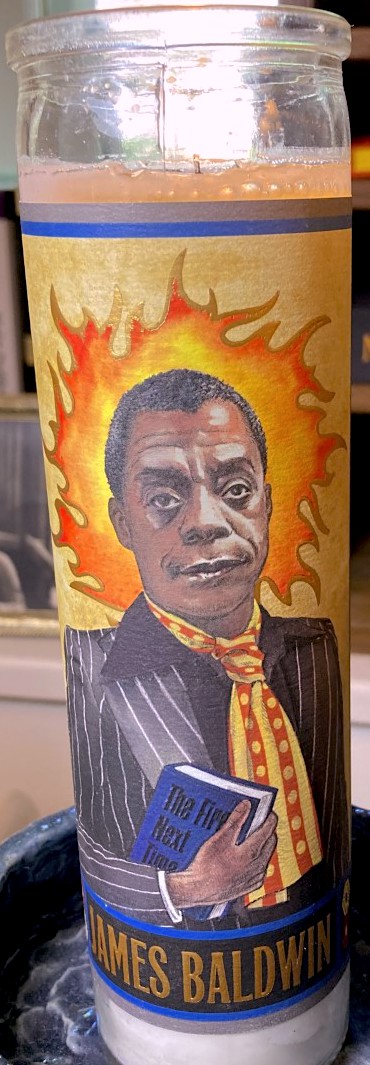

James Arthur Baldwin (August 2, 1924 – December 1, 1987) was an American writer. He garnered acclaim across various media, including

As the oldest child, James worked part-time from an early age to help support his family. He was molded not only by the difficult relationships in his own household but by the results of poverty and discrimination he saw all around him. As he grew up, friends he sat next to in church would turn away to drugs, crime, or prostitution. In what Tubbs found not only a commentary on his own life but on the Black experience in America, Baldwin once wrote, "I never had a childhood ... I did not have any human identity ... I was born dead."

As the oldest child, James worked part-time from an early age to help support his family. He was molded not only by the difficult relationships in his own household but by the results of poverty and discrimination he saw all around him. As he grew up, friends he sat next to in church would turn away to drugs, crime, or prostitution. In what Tubbs found not only a commentary on his own life but on the Black experience in America, Baldwin once wrote, "I never had a childhood ... I did not have any human identity ... I was born dead."

James Baldwin early manuscripts and papers, 1941–1945

(2.7 linear feet) are housed at

James Baldwin Papers

Manuscripts, Archives and Rare Books Division, Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, the

Queer Pollen: White Seduction, Black Male Homosexuality, and the Cinematic

'. University of Illinois Press, 2011. Chapter 2.

Letters to David Moses

at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library

James Baldwin Playboy Interview

archival materials held b

Princeton University Library Special Collections

"A Conversation With James Baldwin"

1963-06-24,

Transcript of interview with Dr. Kenneth Clark

* * * * Altman, Elias

"Watered Whiskey: James Baldwin's Uncollected Writings"

''The Nation'', April 13, 2011. * * Gwin, Minrose.

Southernspaces.org

March 11, 2008. ''Southern Spaces''.

James Baldwin talks about race, political struggle and the human condition

at the Wheeler Hall, Berkeley, CA, in 1974

selected manuscripts, correspondence, and photographic portraits from th

Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library

at Yale University *

''James Baldwin: The Price of the Ticket''

distributed by California Newsreel

Baldwin's ''American Masters'' page

"Writings of James Baldwin"

from

"James Baldwin"

''The Literary Encyclopedia'', October 25, 2002.

Audio files of speeches and interviews

at UC Berkeley

See Baldwin's 1963 film

''

Video: Baldwin debate with William F. Buckley

(via UC Berkeley Media Resources Center) * * ''Guardian'' Book

"Author Page"

with profile and links to further articles

The James Baldwin Collective

in Paris, France * FBI files on James Baldwin

FBI Docs

contains information about James Baldwin's destroyed FBI files and FBI files about him held by the National Archives

A Look Inside James Baldwin's 1,884 Page FBI File

James Baldwin

at Biography.com

Portrait of James Baldwin, 1964

''Los Angeles Times'' Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library,

Portrait of James Baldwin, 1985

''Los Angeles Times'' Photographic Archive (Collection 1429). UCLA Library Special Collections, Charles E. Young Research Library,

essay

An essay is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a letter, a paper, an article, a pamphlet, and a short story. Essays have been sub-classified as formal a ...

s, novel

A novel is a relatively long work of narrative fiction, typically written in prose and published as a book. The present English word for a long work of prose fiction derives from the for "new", "news", or "short story of something new", itsel ...

s, plays

Play most commonly refers to:

* Play (activity), an activity done for enjoyment

* Play (theatre), a work of drama

Play may refer also to:

Computers and technology

* Google Play, a digital content service

* Play Framework, a Java framework

* P ...

, and poems

Poetry (derived from the Greek ''poiesis'', "making"), also called verse, is a form of literature that uses aesthetic and often rhythmic qualities of language − such as phonaesthetics, sound symbolism, and metre − to evoke meanings in a ...

. His first novel, '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'', was published in 1953; decades later, ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' magazine included the novel on its list of the 100 best English-language novels released from 1923 to 2005. His first essay collection, ''Notes of a Native Son

''Notes of a Native Son'' is a collection of ten essays by James Baldwin, published in 1955, mostly tackling issues of race in America and Europe. The volume, as his first non-fiction book, compiles essays of Baldwin that had previously appear ...

'', was published in 1955.

Baldwin's work fictionalizes fundamental personal questions and dilemmas amid complex social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

and psychological pressures. Themes of masculinity

Masculinity (also called manhood or manliness) is a set of attributes, behaviors, and roles associated with men and boys. Masculinity can be theoretically understood as socially constructed, and there is also evidence that some behaviors con ...

, sexuality

Human sexuality is the way people experience and express themselves sexually. This involves biological, psychological, physical, erotic, emotional, social, or spiritual feelings and behaviors. Because it is a broad term, which has varied ...

, race

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

, and class

Class or The Class may refer to:

Common uses not otherwise categorized

* Class (biology), a taxonomic rank

* Class (knowledge representation), a collection of individuals or objects

* Class (philosophy), an analytical concept used differentl ...

intertwine to create intricate narrative

A narrative, story, or tale is any account of a series of related events or experiences, whether nonfictional (memoir, biography, news report, documentary, travel literature, travelogue, etc.) or fictional (fairy tale, fable, legend, thriller (ge ...

s that run parallel with some of the major political movement

A political movement is a collective attempt by a group of people to change government policy or social values. Political movements are usually in opposition to an element of the status quo, and are often associated with a certain ideology. Some t ...

s toward social change in mid-twentieth century America, such as the civil rights movement

The civil rights movement was a nonviolent social and political movement and campaign from 1954 to 1968 in the United States to abolish legalized institutional Racial segregation in the United States, racial segregation, Racial discrimination ...

and the gay liberation movement

The gay liberation movement was a social and political movement of the late 1960s through the mid-1980s that urged lesbians and gay men to engage in radical direct action, and to counter societal shame with gay pride.Hoffman, 2007, pp.xi-xiii. ...

. Baldwin's protagonists are often but not exclusively African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

, and gay

''Gay'' is a term that primarily refers to a homosexual person or the trait of being homosexual. The term originally meant 'carefree', 'cheerful', or 'bright and showy'.

While scant usage referring to male homosexuality dates to the late 1 ...

and bisexual

Bisexuality is a romantic or sexual attraction or behavior toward both males and females, or to more than one gender. It may also be defined to include romantic or sexual attraction to people regardless of their sex or gender identity, whi ...

men frequently feature prominently in his literature. These characters often face internal and external obstacles in their search for social

Social organisms, including human(s), live collectively in interacting populations. This interaction is considered social whether they are aware of it or not, and whether the exchange is voluntary or not.

Etymology

The word "social" derives from ...

and self-acceptance

Self-acceptance is acceptance of self.

Definition

Self-acceptance can be defined as:

* the awareness of one's strengths and weaknesses,

* the realistic (yet subjective) appraisal of one's talents, capabilities, and general worth, and,

* feelings ...

. Such dynamics are prominent in Baldwin's second novel, ''Giovanni's Room

''Giovanni's Room'' is a 1956 novel by James Baldwin. Stryker, Susan. ''Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback'' (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001), p. 104. The book focuses on the events in the life of an Americ ...

'', which was written in 1956, well before the gay liberation movement.

His reputation has endured since his death and his work has been adapted for the screen to great acclaim. An unfinished manuscript, ''Remember This House

''Remember This House'' is an unfinished manuscript by James Baldwin, a memoir of his personal recollections of civil rights leaders Medgar Evers, Malcolm X and Martin Luther King Jr.

Following Baldwin's 1987 death, publishing company McGraw-Hill ...

'', was expanded and adapted for cinema as the documentary film ''I Am Not Your Negro

''I Am Not Your Negro'' is a 2016 documentary film and social critique film essay directed by Raoul Peck, based on James Baldwin's unfinished manuscript '' Remember This House''. Narrated by actor Samuel L. Jackson, the film explores the hist ...

'' (2016), which was nominated for Best Documentary Feature at the 89th Academy Awards. One of his novels, ''If Beale Street Could Talk

''If Beale Street Could Talk'' is a 1974 novel by American writer James Baldwin. His fifth novel (and 13th book overall), it is a love story set in Harlem in the early 1970s. The title is a reference to the 1916 W.C. Handy blues song "Beale S ...

'', was adapted into the Academy Award

The Academy Awards, better known as the Oscars, are awards for artistic and technical merit for the American and international film industry. The awards are regarded by many as the most prestigious, significant awards in the entertainment ind ...

-winning film of the same name in 2018, directed and produced by Barry Jenkins

Barry Jenkins (born November 19, 1979) is an American filmmaker. After making his filmmaking debut with the short film ''My Josephine'' (2003), he directed his first feature film ''Medicine for Melancholy'' (2008) for which he received an Indep ...

.

In addition to writing, Baldwin was also a well-known, and controversial, public figure and orator

An orator, or oratist, is a public speaker, especially one who is eloquent or skilled.

Etymology

Recorded in English c. 1374, with a meaning of "one who pleads or argues for a cause", from Anglo-French ''oratour'', Old French ''orateur'' (14th ...

, especially during the civil rights movement in the United States.

Early life

Birth and family

Baldwin was born as James Arthur Jones to Emma Berdis Jones on August 2, 1924, atHarlem Hospital

Harlem Hospital Center, branded as NYC Health + Hospitals/Harlem, is a 272-bed, public teaching hospital affiliated with Columbia University. It is located at 506 Lenox Avenue in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City and was founded in 1887.

The hosp ...

in New York City. Baldwin was born out of wedlock. Jones never revealed to Baldwin who his biological father was. According to Anna Malaika Tubbs in her account of the mothers of prominent civil rights figures, some rumors stated that James Baldwin's father suffered from drug addiction or that he died, but that in any case, Jones undertook to care for her son as a single mother. A native of Deal Island, Maryland

Deal Island is a census-designated place (CDP) in Somerset County, Maryland, United States. The population was 375 at the 2020 census. It is included in the Salisbury, Maryland-Delaware Metropolitan Statistical Area. The small town was listed on ...

, where she was born in 1903, Emma Jones was one of the many who fled racial segregation

Racial segregation is the systematic separation of people into race (human classification), racial or other Ethnicity, ethnic groups in daily life. Racial segregation can amount to the international crime of apartheid and a crimes against hum ...

in the South during the Great Migration. She arrived in Harlem

Harlem is a neighborhood in Upper Manhattan, New York City. It is bounded roughly by the Hudson River on the west; the Harlem River and 155th Street (Manhattan), 155th Street on the north; Fifth Avenue on the east; and 110th Street (Manhattan), ...

at 19 years old.

In 1927, Jones married David Baldwin, a laborer and Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

preacher. David Baldwin was born in Bunkie, Louisiana

Bunkie is a city in Avoyelles Parish, Louisiana, United States. The population was 4,171 at the 2010 census.

History

Bunkie was founded as a station terminus on the Texas and Pacific Railroad line. It was named for the daughter (whose nickname w ...

, and preached in New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

, but left the South for Harlem in 1919. How David and Emma met is uncertain, but in James Baldwin's semi-autobiographical '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'', the characters based on the two are introduced by the man's sister, who is a friend of the woman. Emma Baldwin would bear eight children with her husband—George, Barbara, Wilmer, David Jr. (named for James's father and deceased half-brother), Gloria, Ruth, Elizabeth, and Paula—and raise them with her eldest James, who took his stepfather's last name. James rarely wrote or spoke of his mother. When he did, he made clear that he admired and loved her, often through reference to her loving smile. Baldwin moved several times in his early life but always to different addresses in Harlem. Harlem was still a mixed-race area of the city in the incipient days of the Great Migration, tenements and penury featured equally throughout the urban landscape.

David Baldwin was many years Emma's senior; he may have been born before Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Emancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranchis ...

in 1863, although James did not know exactly how old his stepfather was. David's mother, Barbara, was born enslaved and lived with the Baldwins in New York before her death when James was seven. David also had a light-skinned half-brother that his mother's erstwhile enslaver had fathered on her, and a sister named Barbara, whom James and others in the family called "Taunty". David's father and James's paternal grandfather had also been born enslaved. David had been married earlier, begetting a daughter, who was as old as Emma when the two were wed, and at least two sons―David, who would die in jail, and Sam, who was eight years James's senior, lived with the Baldwins in New York for a time, and once saved James from drowning.

James referred to his stepfather simply as his "father" throughout his life, but David Sr. and James shared an extremely difficult relationship, nearly rising to physical fights on several occasions. "They fought because ames

Ames may refer to:

Places United States

* Ames, Arkansas, a place in Arkansas

* Ames, Colorado

* Ames, Illinois

* Ames, Indiana

* Ames, Iowa, the most populous city bearing this name

* Ames, Kansas

* Ames, Nebraska

* Ames, New York

* Ames, Ok ...

read books, because he liked movies, because he had white friends", all of which, David Baldwin thought, threatened James's "salvation", Baldwin biographer David Adams Leeming

David Adams Leeming (born February 26, 1937) is an American Philology, philologist who is Professor Emeritus of English and Comparative Literature at the University of Connecticut, and a specialist in comparative literature of mythology.

Biography ...

wrote. David Baldwin also hated white people

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

and "his devotion to God was mixed with a hope that God would take revenge on them for him", wrote another Baldwin biographer James Campbell James Campbell may refer to:

Academics

* James Archibald Campbell (1862–1934), founder of Campbell University in North Carolina

* James Marshall Campbell (1895–1977), dean of the college of arts and sciences at the Catholic University of Americ ...

. During the 1920s and 1930s, David worked at a soft-drinks bottling factory, though he was eventually laid off from this job, and, as his anger entered his sermons, he became less in demand as a preacher. David Baldwin sometimes took out his anger on his family, and the children became fearful of him, tensions to some degree balanced by the love lavished on them by their mother. David Baldwin grew paranoid near the end of his life. He was committed to a mental asylum in 1943 and died of tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

on July 29 of that year, the same day Emma gave birth to their last child, Paula. James Baldwin, at his mother's urging, had visited his dying stepfather the day before, and came to something of a posthumous reconciliation with him in his essay, "Notes of a Native Son

''Notes of a Native Son'' is a collection of ten essays by James Baldwin, published in 1955, mostly tackling issues of race in America and Europe. The volume, as his first non-fiction book, compiles essays of Baldwin that had previously appear ...

", in which he wrote, "in his outrageously demanding and protective way, he loved his children, who were black like him and menaced like him". David Baldwin's funeral was held on James's 19th birthday, around the same time that the Harlem riot broke out.

As the oldest child, James worked part-time from an early age to help support his family. He was molded not only by the difficult relationships in his own household but by the results of poverty and discrimination he saw all around him. As he grew up, friends he sat next to in church would turn away to drugs, crime, or prostitution. In what Tubbs found not only a commentary on his own life but on the Black experience in America, Baldwin once wrote, "I never had a childhood ... I did not have any human identity ... I was born dead."

As the oldest child, James worked part-time from an early age to help support his family. He was molded not only by the difficult relationships in his own household but by the results of poverty and discrimination he saw all around him. As he grew up, friends he sat next to in church would turn away to drugs, crime, or prostitution. In what Tubbs found not only a commentary on his own life but on the Black experience in America, Baldwin once wrote, "I never had a childhood ... I did not have any human identity ... I was born dead."

Education and preaching

Baldwin wrote comparatively little about events at school. At five years old, Baldwin began school at Public School 24 on 128th Street in Harlem. The principal of the school was Gertrude E. Ayer, the first Black principal in the city, who recognized Baldwin's precocity and encouraged him in his research and writing pursuits,; as did some of his teachers, who recognized he had a brilliant mind. Ayer stated that James Baldwin got his writing talent from his mother, whose notes to school were greatly admired by the teachers, and that her son also learned to write like an angel, albeit an avenging one. By fifth grade, not yet a teenager, Baldwin had read some ofFyodor Dostoyevsky

Fyodor Mikhailovich Dostoevsky (, ; rus, Фёдор Михайлович Достоевский, Fyódor Mikháylovich Dostoyévskiy, p=ˈfʲɵdər mʲɪˈxajləvʲɪdʑ dəstɐˈjefskʲɪj, a=ru-Dostoevsky.ogg, links=yes; 11 November 18219 ...

's works, Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the harsh ...

's ''Uncle Tom's Cabin

''Uncle Tom's Cabin; or, Life Among the Lowly'' is an anti-slavery novel by American author Harriet Beecher Stowe. Published in two volumes in 1852, the novel had a profound effect on attitudes toward African Americans and slavery in the U. ...

'', and Charles Dickens

Charles John Huffam Dickens (; 7 February 1812 – 9 June 1870) was an English writer and social critic. He created some of the world's best-known fictional characters and is regarded by many as the greatest novelist of the Victorian e ...

' ''A Tale of Two Cities

''A Tale of Two Cities'' is a historical novel published in 1859 by Charles Dickens, set in London and Paris before and during the French Revolution. The novel tells the story of the French Doctor Manette, his 18-year-long imprisonment in the ...

'', beginning a lifelong interest in Dickens' work. Baldwin wrote a song that earned New York Mayor

The mayor of New York City, officially Mayor of the City of New York, is head of the executive branch of the government of New York City and the chief executive of New York City. The mayor's office administers all city services, public property ...

Fiorello La Guardia

Fiorello Henry LaGuardia (; born Fiorello Enrico LaGuardia, ; December 11, 1882September 20, 1947) was an American attorney and politician who represented New York in the House of Representatives and served as the 99th Mayor of New York City fro ...

's praise in a letter that La Guardia sent to Baldwin. Baldwin also won a prize for a short story that was published in a church newspaper. Baldwin's teachers recommended that he go to a public library on 135th Street in Harlem, a place that would become a sanctuary for Baldwin and where he would make a deathbed request for his papers and effects to be deposited.

It was at P.S. 24 that Baldwin met Orilla "Bill" Miller, a young white schoolteacher from the Midwest whom Baldwin named as partially the reason that he "never really managed to hate white people". Among other outings, Miller took Baldwin to see an all-Black rendition of Orson Welles

George Orson Welles (May 6, 1915 – October 10, 1985) was an American actor, director, producer, and screenwriter, known for his innovative work in film, radio and theatre. He is considered to be among the greatest and most influential f ...

's take on ''Macbeth

''Macbeth'' (, full title ''The Tragedie of Macbeth'') is a tragedy by William Shakespeare. It is thought to have been first performed in 1606. It dramatises the damaging physical and psychological effects of political ambition on those w ...

'' in Lafayette Theatre, from which flowed a lifelong desire to succeed as a playwright

A playwright or dramatist is a person who writes plays.

Etymology

The word "play" is from Middle English pleye, from Old English plæġ, pleġa, plæġa ("play, exercise; sport, game; drama, applause"). The word "wright" is an archaic English ...

. David was reluctant to let his stepson go to the theatre—he saw stage works as sinful and was suspicious of Miller—but his wife insisted, reminding him of the importance of Baldwin's education. Miller later directed the first play that Baldwin ever wrote.

After P.S. 24, Baldwin entered Harlem's Frederick Douglass Junior High School. At Douglass Junior High, Baldwin met two important influences. The first was Herman W. "Bill" Porter, a Black Harvard

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

graduate. Porter was the faculty advisor to the school's newspaper, the ''Douglass Pilot'', where Baldwin would later be the editor. Porter took Baldwin to the library on 42nd Street to research a piece that would turn into Baldwin's first published essay titled "Harlem—Then and Now", which appeared in the autumn 1937 issue of ''Douglass Pilot''. The second of these influences from his time at Douglass was the renowned poet of the Harlem Renaissance

The Harlem Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of African American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater, politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City, spanning the 1920s and 1930s. At the t ...

, Countee Cullen

Countee Cullen (born Countee LeRoy Porter; May 30, 1903 – January 9, 1946) was an American poet, novelist, children's writer, and playwright, particularly well known during the Harlem Renaissance.

Early life

Childhood

Countee LeRoy Porter ...

. Cullen taught French and was a literary advisor in the English department. Baldwin later remarked that he "adored" Cullen's poetry, and said he found the spark of his dream to live in France in Cullen's early impression on him. Baldwin graduated from Frederick Douglass Junior High in 1938.

In 1938, Baldwin applied to and was accepted at De Witt Clinton High School

, motto_translation = Without Work Nothing Is Accomplished

, image = DeWitt Clinton High School front entrance IMG 7441 HLG.jpg

, seal_image = File:Clinton News.JPG

, seal_size = 124px

, ...

in the Bronx

The Bronx () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Bronx County, in the state of New York. It is south of Westchester County; north and east of the New York City borough of Manhattan, across the Harlem River; and north of the New Y ...

, a predominantly white

White is the lightest color and is achromatic (having no hue). It is the color of objects such as snow, chalk, and milk, and is the opposite of black. White objects fully reflect and scatter all the visible wavelengths of light. White on ...

, predominantly Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

school, matriculating there that fall. At De Witt Clinton, Baldwin worked on the school's magazine, the ''Magpie'' with Richard Avedon

Richard Avedon (May 15, 1923 – October 1, 2004) was an American fashion and portrait photographer. He worked for ''Harper's Bazaar'', ''Vogue'' and ''Elle'' specializing in capturing movement in still pictures of fashion, theater and danc ...

, who went on to become a noted photographer, and Emile Capouya

Emile Capouya was an American essayist, critic, and writer. His book 'In the sparrow Hills' won the Sue Kaufman Prize of the American Academy and Institute of Arts and Letters. Mr. Capouya was born in Manhattan in 1925 and grew up in the Bronx.

...

and Sol Stein

Sol Stein (October 13, 1926 – September 19, 2019) was the author of 13 books and was Publisher and Editor-in-Chief of Stein and Day Publishers for 27 years.

Early life

Born in Chicago on October 13, 1926, Stein was the son of Louis Stein and Z ...

, who would both become renowned publishers. Baldwin did interviews and editing at the magazine and published a number of poems and other writings. Baldwin finished at De Witt Clinton in 1941. His yearbook listed his ambition as "novelist-playwright". Baldwin's motto in his yearbook was: "Fame is the spur and—ouch!"

During his high school years, uncomfortable with the fact that, unlike many of his peers, he was becoming more sexually interested in males than in females, Baldwin sought refuge in religion. He first joined the now-demolished Mount Calvary of the Pentecostal Faith Church on Lenox Avenue

Lenox Avenue – also named Malcolm X Boulevard; both names are officially recognized – is the primary north–south route through Harlem in the upper portion of the New York City borough of Manhattan. This two-way street runs from F ...

in 1937, but followed the preacher there, Bishop Rose Artemis Horn, who was affectionately called Mother Horn, when she left to preach at Fireside Pentecostal Assembly. At 14, "Brother Baldwin", as Baldwin was called, first took to Fireside's altar. It was at Fireside Pentecostal, during his mostly extemporaneous sermons, that Baldwin "learned that he had authority as a speaker and could do things with a crowd", says biographer Campbell. Baldwin delivered his final sermon at Fireside Pentecostal in 1941. Baldwin later wrote in the essay "Down at the Cross" that the church "was a mask for self-hatred and despair ... salvation stopped at the church door". He related that he had a rare conversation with David Baldwin "in which they had really spoken to one another", with his stepfather asking, "You'd rather write than preach, wouldn't you?"

Later years in New York

Baldwin left school in 1941 to earn money to help support his family. He secured a job helping to build aUnited States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

depot in New Jersey. In the middle of 1942 Emile Capouya helped Baldwin get a job laying tracks for the military in Belle Mead, New Jersey

Belle Mead is an unincorporated community and census-designated place (CDP) located within Montgomery Township, in Somerset County, New Jersey, United States.Rocky Hill and commuted to Belle Mead. In Belle Mead, Baldwin came to know the face of a prejudice that deeply frustrated and angered him and that he named the partial cause of his later emigration out of America. Baldwin's fellow white workmen, who mostly came from the South, derided him for what they saw as his "uppity" ways and his lack of "respect". Baldwin's sharp, ironic wit particularly upset the white Southerners he met in Belle Mead.

In an incident that Baldwin described in "

Beauford Delaney's arrival in France in 1953 marked "the most important personal event in Baldwin's life" that year, according to biographer David Leeming. Around the same time, Baldwin's circle of friends shifted away from primarily white bohemians toward a coterie of Black American expatriates: Baldwin grew close to dancer Bernard Hassell; spent significant amounts of time at

Beauford Delaney's arrival in France in 1953 marked "the most important personal event in Baldwin's life" that year, according to biographer David Leeming. Around the same time, Baldwin's circle of friends shifted away from primarily white bohemians toward a coterie of Black American expatriates: Baldwin grew close to dancer Bernard Hassell; spent significant amounts of time at

Baldwin lived in France for most of his later life. He also spent some time in

Baldwin lived in France for most of his later life. He also spent some time in

On December 1, 1987, Baldwin died from

On December 1, 1987, Baldwin died from

''The New York Times'', May 19, 1990. Following his death, publishing company

"'I Am Not Your Negro': Film Review , TIFF 2016"

''

Les Amis de la Maison Baldwin

a French organization whose initial goal was to purchase the house by launching a capital campaign funded by the U.S. philanthropic sector, grew out of this effort. This campaign was unsuccessful without the support of the Baldwin Estate. Attempts to engage the French government in conservation of the property were dismissed by the mayor of Saint-Paul-de-Vence, Joseph Le Chapelain whose statement to the local press claiming "nobody's ever heard of James Baldwin" mirrored those of Henri Chambon, the owner of the corporation that razed his home. Construction was completed in 2019 on the apartment complex that now stands where Chez Baldwin once stood.

In 2005, the

In 2005, the

is a one-hour television special program featuring a debate between Baldwin and leading American conservative William F. Buckley, Jr., at the Cambridge Union, Cambridge University, England.

* 1971. Meeting the Man: James Baldwin in Paris. Documentary. Directed by Terence Dixon.

* 1974. James Baldwin talks about race, political struggle, and the human condition at the Wheeler Hall, Berkeley, CA.

* 1975. "Assignment America; 119; Conversation with a Native Son", from Notes of a Native Son

''Notes of a Native Son'' is a collection of ten essays by James Baldwin, published in 1955, mostly tackling issues of race in America and Europe. The volume, as his first non-fiction book, compiles essays of Baldwin that had previously appear ...

", Baldwin went to a restaurant in Princeton

Princeton University is a private research university in Princeton, New Jersey. Founded in 1746 in Elizabeth as the College of New Jersey, Princeton is the fourth-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and one of the nine ...

called the Balt where, after a long wait, Baldwin was told that "colored boys" weren't served there. Then, on his last night in New Jersey, in another incident also memorialized in "Notes of a Native Son", Baldwin and a friend went to a diner after a movie only to be told that Black people were not served there. Infuriated, he went to another restaurant, expecting to be denied service once again. When that denial of service came, humiliation and rage heaved up to the surface and Baldwin hurled the nearest object at hand—a water mug—at the waiter, missing her and shattering the mirror behind her. Baldwin and his friend narrowly escaped.

During these years, Baldwin was torn between his desire to write and his need to provide for his family. He took a succession of menial jobs, and feared becoming like his stepfather, who had been unable to properly provide for his family. Fired from the track-laying job, he returned to Harlem in June 1943 to live with his family after taking a meat-packing job. Baldwin would lose the meat-packing job too after falling asleep at the plant. He became listless and unstable, drifting from this odd job to that. Baldwin drank heavily, and endured the first of his nervous breakdown

A mental disorder, also referred to as a mental illness or psychiatric disorder, is a behavioral or mental pattern that causes significant distress or impairment of personal functioning. Such features may be persistent, relapsing and remitti ...

s.

Beauford Delaney

Beauford Delaney (December 30, 1901 – March 26, 1979) was an American modernist painter. He is remembered for his work with the Harlem Renaissance in the 1930s and 1940s, as well as his later works in abstract expressionism following his move ...

helped Baldwin cast off his melancholy. In the year before he left De Witt Clinton and at Capuoya's urging, Baldwin had met Delaney, a modernist painter, in Greenwich Village

Greenwich Village ( , , ) is a neighborhood on the west side of Lower Manhattan in New York City, bounded by 14th Street to the north, Broadway to the east, Houston Street to the south, and the Hudson River to the west. Greenwich Village ...

. Delaney would become Baldwin's long-time friend and mentor, and helped demonstrate to Baldwin that a Black man could make his living in art. Moreover, when World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

bore down on the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

the winter after Baldwin left De Witt Clinton, the Harlem that Baldwin knew was atrophying—no longer the bastion of a Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, the community grew more economically isolated and Baldwin considered his prospects there bleak. This led Baldwin to move to Greenwich Village, where Beauford Delaney lived and a place by which he had been fascinated since at least fifteen.

Baldwin lived in several locations in Greenwich Village, first with Delaney, then with a scattering of other friends in the area. He took a job at the Calypso Restaurant, an unsegregated eatery famous for the parade of prominent Black people who dined there. At Calypso, Baldwin worked under Trinidadian restauranteur Connie Williams

Constance Hess Williams (born June 27, 1944) is an American politician who served as a Democratic member of the Pennsylvania State Senate for the 17th District, from 2001 to 2009. She previously represented the 149th district in the Pennsy ...

, whom Delaney had introduced him to. While working at Calypso, Baldwin continued to explore his sexuality, came out to Capouya and another friend, and frequent Calypso guest, Stan Weir

Stanley Brian Weir (born March 17, 1952) is a Canadian former ice hockey centre. He played on five different teams for the National Hockey League, and one season in the World Hockey Association, over an 11-year career that lasted from 1972 to ...

. He also had numerous one-night stand

A one-night stand or one-night sex is a single sexual encounter in which there is an expectation that there shall be no further relations between the sexual participants. It draws its name from the common practice of a one-night stand, a single ...

s with various men, and several relationships with women. Baldwin's major love during these years in the Village was an ostensibly straight Black man named Eugene Worth. Worth introduced Baldwin to the Young People's Socialist League and Baldwin became a Trotskyist

Trotskyism is the political ideology and branch of Marxism developed by Ukrainian-Russian revolutionary Leon Trotsky and some other members of the Left Opposition and Fourth International. Trotsky self-identified as an orthodox Marxist, a rev ...

for a brief period. Baldwin never expressed his desire for Worth, and Worth died by suicide

Suicide is the act of intentionally causing one's own death. Mental disorders (including depression, bipolar disorder, schizophrenia, personality disorders, anxiety disorders), physical disorders (such as chronic fatigue syndrome), and s ...

after jumping from the George Washington Bridge

The George Washington Bridge is a double-decked suspension bridge spanning the Hudson River, connecting Fort Lee, New Jersey, with Manhattan in New York City. The bridge is named after George Washington, the first president of the United St ...

in 1946. In 1944 Baldwin met Marlon Brando

Marlon Brando Jr. (April 3, 1924 – July 1, 2004) was an American actor. Considered one of the most influential actors of the 20th century, he received numerous accolades throughout his career, which spanned six decades, including two Academ ...

, whom he was also attracted to, at a theater class in The New School

The New School is a private research university in New York City. It was founded in 1919 as The New School for Social Research with an original mission dedicated to academic freedom and intellectual inquiry and a home for progressive thinkers. ...

. The two became fast friends, maintaining a closeness that endured through the Civil Rights Movement and long after. Later, in 1945, Baldwin started a literary magazine called ''The Generation'' with Claire Burch

Claire Burch (1925 in Brooklyn, New York – May 21, 2009) was an American author, filmmaker and poet.

History

After attending grade school in Brooklyn, Burch completed a commercial art course at Washington Irving High School in Manhattan and ...

, who was married to Brad Burch, Baldwin's classmate from De Witt Clinton. Baldwin's relationship with the Burches soured in the 1950s but was resurrected near the end of his life.

Near the end of 1944 Baldwin met Richard Wright, who had published ''Native Son

''Native Son'' (1940) is a novel written by the American author Richard Wright. It tells the story of 20-year-old Bigger Thomas, a black youth living in utter poverty in a poor area on Chicago's South Side in the 1930s.

While not apologizing ...

'' several years earlier. Baldwin's main designs for that initial meeting were trained on convincing Wright of the quality of an early manuscript for what would become '' Go Tell It On The Mountain'', then called "Crying Holy". Wright liked the manuscript and encouraged his editors to consider Baldwin's work, but an initial $500 advance from Harper & Brothers

Harper is an American publishing house, the flagship imprint of global publisher HarperCollins based in New York City.

History

J. & J. Harper (1817–1833)

James Harper and his brother John, printers by training, started their book publishin ...

dissipated with no book to show for the trouble. Harper eventually declined to publish the book at all. Nonetheless, Baldwin sent letters to Wright regularly in the subsequent years and would reunite with Wright in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

in 1948, though their relationship turned for the worse soon after the Paris reunion.

In these years in the Village, Baldwin made a number of connections in the liberal New York literary establishment, primarily through Worth: Sol Levitas

Sol Levitas (1894-1960) was an American magazine editor, an "old-line Socialist" and "Russian refugee journalist" who served as managing editor of ''The New Leader'' (1940-1950) and "shaped the journal's character."

Background

Sol Levitas wa ...

at ''The New Leader

''The New Leader'' (1924–2010) was an American political and cultural magazine.

History

''The New Leader'' began in 1924 under a group of figures associated with the Socialist Party of America, such as Eugene V. Debs and Norman Thomas. It was p ...

'', Randall Jarrell

Randall Jarrell (May 6, 1914 – October 14, 1965) was an American poet, literary critic, children's author, essayist, and novelist. He was the 11th Consultant in Poetry to the Library of Congress—a position that now bears the title Poet ...

at ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'', Elliot Cohen and Robert Warshow Robert Warshow (1917–1955) was an American author associated with the New York Intellectuals. He is best known for his criticism of film and popular culture for ''Commentary'' and ''The Partisan Review''. Born in New York City and raised in its B ...

at ''Commentary

Commentary or commentaries may refer to:

Publications

* ''Commentary'' (magazine), a U.S. public affairs journal, founded in 1945 and formerly published by the American Jewish Committee

* Caesar's Commentaries (disambiguation), a number of works ...

'', and Philip Rahv

Philip, also Phillip, is a male given name, derived from the Greek (''Philippos'', lit. "horse-loving" or "fond of horses"), from a compound of (''philos'', "dear", "loved", "loving") and (''hippos'', "horse"). Prominent Philips who popularize ...

at ''Partisan Review

''Partisan Review'' (''PR'') was a small-circulation quarterly "little magazine" dealing with literature, politics, and cultural commentary published in New York City. The magazine was launched in 1934 by the Communist Party USA–affiliated John ...

''. Baldwin wrote many reviews for ''The New Leader'', but was published for the first time in ''The Nation'' in a 1947 review of Maxim Gorki

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and sociali ...

's ''Best Short Stories''. Only one of Baldwin's reviews from this era made it into his later essay collection '' The Price of the Ticket'': a sharply ironic assay of Ross Lockridge

Ross Franklin Lockridge Jr. (April 25, 1914 – March 6, 1948) was an American writer known for his novel '' Raintree County'' (1948). The novel became a bestseller and has been praised by readers and critics alike. Some have considered it a " ...

's ''Raintree Countree'' that Baldwin wrote for ''The New Leader''. Baldwin's first essay, "The Harlem Ghetto", was published a year later in ''Commentary'' and explored anti-Semitism among Black Americans. His conclusion in "Harlem Ghetto" was that Harlem was a parody of white America, with white American anti-Semitism included. Jewish people were also the main group of white people that Black Harlem dwellers met, so Jews became a kind of synecdoche

Synecdoche ( ) is a type of metonymy: it is a figure of speech in which a term for a part of something is used to refer to the whole (''pars pro toto''), or vice versa (''totum pro parte''). The term comes from Greek .

Examples in common Engl ...

for all that the Black people in Harlem thought of white people. Baldwin published his second essay in ''The New Leader'', riding a mild wave of excitement over "Harlem Ghetto": in "Journey to Atlanta", Baldwin uses the diary recollections of his younger brother David, who had gone to Atlanta as part of a singing group, to unleash a lashing of irony and scorn on the South, white radicals, and ideology itself. This essay, too, was well received.

Baldwin tried to write another novel, ''Ignorant Armies'', plotted in the vein of ''Native Son'' with a focus on a scandalous murder, but no final product materialized and his strivings toward a novel remained unsated. Baldwin spent two months out of summer 1948 at Shanks Village, a writer's colony in Woodstock, New York

Woodstock is a town in Ulster County, New York, United States, in the northern part of the county, northwest of Kingston, NY. It lies within the borders of the Catskill Park. The population was 5,884 at the 2010 census, down from 6,241 in 2000 ...

. He then published his first work of fiction, a short story called "Previous Condition", in the October 1948 issue of ''Commentary'', about a 20-something Black man who is evicted from his apartment, the apartment a metaphor for white society.

Career

Life in Paris (1948–1957)

Disillusioned by Americanprejudice

Prejudice can be an affective feeling towards a person based on their perceived group membership. The word is often used to refer to a preconceived (usually unfavourable) evaluation or classification of another person based on that person's per ...

against Black people, as well as wanting to see himself and his writing outside of an African-American context, he left the United States at the age of 24 to settle in Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

. Baldwin wanted not to be read as "merely a Negro

In the English language, ''negro'' is a term historically used to denote persons considered to be of Black African heritage. The word ''negro'' means the color black in both Spanish and in Portuguese, where English took it from. The term can be ...

; or, even, merely a Negro writer." He also hoped to come to terms with his sexual ambivalence and escape the hopelessness

Depression is a mental state of low mood and aversion to activity, which affects more than 280 million people of all ages (about 3.5% of the global population). Classified medically as a mental and behavioral disorder, the experience of ...

that many young African-American men like himself succumbed to in New York.

In 1948, with $1,500 ($ today) in funding from a Rosenwald Fellowship, Baldwin attempted a photography and essay book titled ''Unto the Dying Lamb'' with a photographer friend named Theodore Pelatowski, whom Baldwin met through Richard Avedon. The book was intended as both a catalog of churches and an exploration of religiosity in Harlem, but it was never finished. The Rosenwald money did, however, grant Baldwin the prospect of consummating a desire he held for several years running: moving to France. This he did: after saying his goodbyes to his mother and younger siblings, with forty dollars to his name, Baldwin flew from New York to Paris on November 11, 1948, having given most of the scholarship funds to his mother. Baldwin would give various explanations for leaving America—sex, Calvinism

Calvinism (also called the Reformed Tradition, Reformed Protestantism, Reformed Christianity, or simply Reformed) is a major branch of Protestantism that follows the theological tradition and forms of Christian practice set down by John Cal ...

, an intense sense of hostility he feared would turn inward—but most of all, his race: the feature of his existence that had theretofore exposed him to a lengthy catalog of humiliations. He hoped for a more peaceable existence in Paris.

In Paris, Baldwin was soon involved in the cultural radicalism of the Left Bank

In geography, a bank is the land alongside a body of water. Different structures are referred to as ''banks'' in different fields of geography, as follows.

In limnology (the study of inland waters), a stream bank or river bank is the terrai ...

. He started to publish his work in literary anthologies

In book publishing

Publishing is the activity of making information, literature, music, software and other content available to the public for sale or for free. Traditionally, the term refers to the creation and distribution of printed work ...

, notably ''Zero'' which was edited by his friend Themistocles Hoetis and which had already published essays by Richard Wright.

Baldwin spent nine years living in Paris, mostly in Saint-Germain-des-Prés

Saint-Germain-des-Prés () is one of the four administrative quarters of the 6th arrondissement of Paris, France, located around the church of the former Abbey of Saint-Germain-des-Prés. Its official borders are the River Seine on the north ...

, with various excursions to Switzerland

). Swiss law does not designate a ''capital'' as such, but the federal parliament and government are installed in Bern, while other federal institutions, such as the federal courts, are in other cities (Bellinzona, Lausanne, Luzern, Neuchâtel ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, and back to the United States. Baldwin's time in Paris was itinerant: he stayed with various friends around the city and in various hotels. Most notable of these lodgings was Hôtel Verneuil, a hotel in Saint-Germain that had collected a motley crew of struggling expatriates, mostly writers. This Verneuil circle spawned numerous friendships that Baldwin relied upon in rough periods. Baldwin was also continuously poor during his time in Paris, with only momentary respites from that condition. In his early years in Saint-Germain, Baldwin acquainted himself with Otto Friedrich

Otto Alva Friedrich (born 1929 Boston, Massachusetts; died April 26, 1995 Manhasset, New York), was an American author, and historian. The son of the political theorist, and Harvard professor Carl Joachim Friedrich, Otto Friedrich graduated fro ...

, Mason Hoffenberg

Mason Kass Hoffenberg (December 1922 – 1 June 1986) was an American writer best known for having written the satiric novel ''Candy'' in collaboration with Terry Southern.

Biography

Hoffenberg was born in New York City into a wealthy Jewish ...

, Asa Benveniste, Themistocles Hoetis, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was one of the key figures in the philosophy of existentialism (and phenomenology), a French playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and litera ...

, Simone de Beauvoir

Simone Lucie Ernestine Marie Bertrand de Beauvoir (, ; ; 9 January 1908 – 14 April 1986) was a French existentialist philosopher, writer, social theorist, and feminist activist. Though she did not consider herself a philosopher, and even th ...

, Max Ernst

Max Ernst (2 April 1891 – 1 April 1976) was a German (naturalised American in 1948 and French in 1958) painter, sculptor, printmaker, graphic artist, and poet. A prolific artist, Ernst was a primary pioneer of the Dada movement and Surrealism ...

, Truman Capote

Truman Garcia Capote ( ; born Truman Streckfus Persons; September 30, 1924 – August 25, 1984) was an American novelist, screenwriter, playwright and actor. Several of his short stories, novels, and plays have been praised as literary classics, ...

, and Stephen Spender

Sir Stephen Harold Spender (28 February 1909 – 16 July 1995) was an English poet, novelist and essayist whose work concentrated on themes of social injustice and the class struggle. He was appointed Poet Laureate Consultant in Poetry by the ...

, among many others. Baldwin also met Lucien Happersberger, a Swiss boy, seventeen years old at the time of their first meeting, who came to France in search of excitement. Happersberger became Baldwin's lover, especially in Baldwin's first two years in France, and Baldwin's near-obsession for some time after. Baldwin and Happersberger would remain friends for the next thirty-nine years. Though his time in Paris was not easy, Baldwin did escape the aspects of American life that most terrified him—especially the "daily indignities of racism", per biographer James Campbell. According to Baldwin's friend and biographer David Leeming: "Baldwin seemed at ease in his Paris life; Jimmy Baldwin the aesthete

Aestheticism (also the Aesthetic movement) was an art movement in the late 19th century which privileged the aesthetic value of literature, music and the arts over their socio-political functions. According to Aestheticism, art should be prod ...

and lover reveled in the Saint-Germain ambiance."

In his early years in Paris prior to '' Go Tell It On The Mountains publication, Baldwin wrote several notable works. "The Negro in Paris", published first in ''The Reporter'', explored Baldwin's perception of an incompatibility between Black Americans and Black Africans in Paris, as Black Americans had faced a "depthless alienation from oneself and one's people" that was mostly unknown to Parisian Africans. He also wrote "The Preservation of Innocence", which traced the violence against homosexuals in American life to the protracted adolescence of America as a society. In the magazine ''Commentary'', he published "Too Little, Too Late", an essay on Black American literature, and "The Death of the Prophet", a short story that grew out of Baldwin's earlier writings for ''Go Tell It on The Mountain''. In the latter work, Baldwin employs a character named Johnnie to trace his bouts of depression to his inability to resolve the questions of filial intimacy emanating from Baldwin's relationship with his stepfather. In December 1949, Baldwin was arrested and jailed for receiving stolen goods after an American friend brought him bedsheets that the friend had taken from another Paris hotel. When the charges were dismissed several days later, to the laughter of the courtroom, Baldwin wrote of the experience in his essay "Equal in Paris", also published in ''Commentary'' in 1950. In the essay, he expressed his surprise and bewilderment at how he was no longer a "despised black man" but simply an American, no different than the white American friend who stole the sheet and with whom he had been arrested.

In these years in Paris, Baldwin also published two of his three scathing critiques of Richard Wright—"Everybody's Protest Novel" in 1949 and "Many Thousands Gone" in 1951. Baldwin's critique of Wright is an extension of his disapprobation toward protest literature. Per biographer David Leeming, Baldwin despised protest literature because it is "concerned with theories and with the categorization of human beings, and however brilliant the theories or accurate the categorizations, they fail because they deny life." Protest writing cages humanity, but, according to Baldwin, "only within this web of ambiguity, paradox, this hunger, danger, darkness, can we find at once ourselves and the power that will free us from ourselves." Baldwin took Wright's ''Native Son'' and Stowe's ''Uncle Tom's Cabin'', both erstwhile favorites of Baldwin's, as paradigmatic examples of the protest novel's problem. The treatment of Wright's Bigger Thomas by socially earnest white people near the end of ''Native Son'' was, for Baldwin, emblematic of white Americans' presumption that for Black people "to become truly human and acceptable, hey

Hey or Hey! may refer to:

Music

* Hey (band), a Polish rock band

Albums

* ''Hey'' (Andreas Bourani album) or the title song (see below), 2014

* ''Hey!'' (Julio Iglesias album) or the title song, 1980

* ''Hey!'' (Jullie album) or the title s ...

must first become like us. This assumption once accepted, the Negro in America can only acquiesce in the obliteration of his own personality." In these two essays, Baldwin came to articulate what would become a theme in his work: that white racism toward Black Americans was refracted through self-hatred and self-denial—"One may say that the Negro in America does not really exist except in the darkness of hite Hite or HITE may refer to:

*HiteJinro, a South Korean brewery

**Hite Brewery

*Hite (surname)

*Hite, California, former name of Hite Cove, California

*Hite, Utah, a ghost town

* HITE, an industrial estate in Pakistan

See also

*''Hite v. Fairfax

...

minds. ..Our dehumanization of the Negro then is indivisible from our dehumanization of ourselves." Baldwin's relationship with Wright was tense but cordial after the essays, although Baldwin eventually ceased to regard Wright as a mentor. Meanwhile, "Everybody's Protest Novel" had earned Baldwin the label "the most promising young Negro writer since Richard Wright."

Beginning in the winter of 1951, Baldwin and Happersberger took several trips to Loèches-les-Bains in Switzerland, where Happersberger's family owned a small chateau. By the time of the first trip, Happersberger had then entered a heterosexual relationship but grew worried for his friend Baldwin and offered to take Baldwin to the Swiss village. Baldwin's time in the village gave form to his essay "Stranger in the Village

"Stranger in the Village" is an essay by African-American novelist James Baldwin about his experiences in Leukerbad, Switzerland, after he nearly suffered a breakdown. The essay was originally published in ''Harper's Magazine'', October 1953, an ...

", published in ''Harper's Magazine

''Harper's Magazine'' is a monthly magazine of literature, politics, culture, finance, and the arts. Launched in New York City in June 1850, it is the oldest continuously published monthly magazine in the U.S. (''Scientific American'' is older, b ...

'' in October 1953. In that essay, Baldwin described some unintentional mistreatment and offputting experiences at the hands of Swiss villagers who possessed a racial innocence few Americans could attest to. Baldwin explored how the bitter history shared between Black and white Americans had formed an indissoluble web of relations that changed both races: "No road whatever will lead Americans back to the simplicity of this European village where white men still have the luxury of looking on me as a stranger."

Beauford Delaney's arrival in France in 1953 marked "the most important personal event in Baldwin's life" that year, according to biographer David Leeming. Around the same time, Baldwin's circle of friends shifted away from primarily white bohemians toward a coterie of Black American expatriates: Baldwin grew close to dancer Bernard Hassell; spent significant amounts of time at

Beauford Delaney's arrival in France in 1953 marked "the most important personal event in Baldwin's life" that year, according to biographer David Leeming. Around the same time, Baldwin's circle of friends shifted away from primarily white bohemians toward a coterie of Black American expatriates: Baldwin grew close to dancer Bernard Hassell; spent significant amounts of time at Gordon Heath

Gordon Heath (September 20, 1918 – August 27, 1991) was an American actor and musician who narrated the animated feature film ''Animal Farm'' (1954) and appeared in the title role of ''The Emperor Jones'' (1953) and ''Othello'' (1955), both l ...

's club in Paris; regularly listened to Bobby Short

Robert Waltrip Short (September 15, 1924 – March 21, 2005) was an American cabaret singer and pianist, who interpreted songs by popular composers from the first half of the 20th century such as Rodgers and Hart, Cole Porter, Jerome Kern, Harold ...

and Inez Cavanaugh

Inez is a feminine given name. It is the English spelling of the Spanish language, Spanish and Portuguese language, Portuguese name Inés/Inês/Inez, the forms of the given name "Agnes (name), Agnes". The name is pronounced as , , or .

Agnes is ...

's performances at their respective haunts around the city; met Maya Angelou

Maya Angelou ( ; born Marguerite Annie Johnson; April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014) was an American memoirist, popular poet, and civil rights activist. She published seven autobiographies, three books of essays, several books of poetry, and ...

for the first time in these years as she partook in various European renditions of ''Porgy and Bess

''Porgy and Bess'' () is an English-language opera by American composer George Gershwin, with a libretto written by author DuBose Heyward and lyricist Ira Gershwin. It was adapted from Dorothy Heyward and DuBose Heyward's play '' Porgy'', itse ...

''; and occasionally met with writers Richard Gibson

Richard Gibson (born 1 January 1954) is an English actor, best known for his role as the archetypal Gestapo Officer Herr Otto Flick in the BBC hit sitcom series, '' 'Allo 'Allo!''.

Career

Gibson was born in Kampala, Uganda, before the countr ...

and Chester Himes

Chester Bomar Himes (July 29, 1909 – November 12, 1984) was an American writer. His works, some of which have been filmed, include '' If He Hollers Let Him Go'', published in 1945, and the Harlem Detective series of novels for which he is be ...

, composer Howard Swanson, and even Richard Wright. In 1954 Baldwin took a fellowship at the MacDowell writer's colony in New Hampshire to help the process of writing of a new novel and won a Guggenheim Fellowship

Guggenheim Fellowships are grants that have been awarded annually since by the John Simon Guggenheim Memorial Foundation to those "who have demonstrated exceptional capacity for productive scholarship or exceptional creative ability in the ar ...

. Also in 1954, Baldwin published the three-act play ''The Amen Corner

''The Amen Corner'' is a three-act play by James Baldwin. It was Baldwin's first work for the stage following the success of his novel '' Go Tell It on the Mountain''. The drama was first published in 1954, and inspired a short-lived 1983 Broadwa ...

'' which features the preacher Sister Margaret—a fictionalized Mother Horn from Baldwin's time at Fireside Pentecostal—struggling with a difficult inheritance and alienation from herself and her loved ones on account of her religious fervor. Baldwin spent several weeks in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

and particularly around Howard University

Howard University (Howard) is a private, federally chartered historically black research university in Washington, D.C. It is classified among "R2: Doctoral Universities – High research activity" and accredited by the Middle States Commissi ...

while he collaborated with Owen Dodson

Owen Vincent Dodson (November 28, 1914 – June 21, 1983) was an American poet, novelist, and playwright. He was one of the leading African-American poets of his time, associated with the generation of black poets following the Harlem Renaissance ...

for the premiere of ''The Amen Corner'', returning to Paris in October 1955.

Baldwin committed himself to a return to the United States in 1957, so he set about in early 1956 to enjoy what would be his last year in France. He became friends with Norman

Norman or Normans may refer to:

Ethnic and cultural identity

* The Normans, a people partly descended from Norse Vikings who settled in the territory of Normandy in France in the 10th and 11th centuries

** People or things connected with the Norm ...

and Adele Mailer, was recognized by the National Institute of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, music, and art. Its fixed number membership is elected for lifetime appointments. Its headqu ...

with a grant, and was set to publish ''Giovanni's Room

''Giovanni's Room'' is a 1956 novel by James Baldwin. Stryker, Susan. ''Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback'' (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001), p. 104. The book focuses on the events in the life of an Americ ...

''. Nevertheless, Baldwin sank deeper into an emotional wreckage. In the summer of 1956—after a seemingly failed affair with a Black musician named Arnold, Baldwin's first serious relationship since Happersberger—Baldwin overdosed on sleeping pills in a suicide attempt. He regretted the attempt almost instantly and called a friend who had him regurgitate the pills before the doctor arrived. Baldwin went on to attend the Congress of Black Writers and Artists

The Congress of Black Writers and Artists ( French: ''Congrès des écrivains et artistes noirs''; originally called the Congress of Negro Writers and Artists) was a meeting of leading black intellectuals for the purpose of addressing the issues of ...

in September 1956, a conference he found disappointing in its perverse reliance on European themes while nonetheless purporting to extol African originality.

Literary career

Baldwin's first published work, a review of the writerMaxim Gorky

Alexei Maximovich Peshkov (russian: link=no, Алексе́й Макси́мович Пешко́в; – 18 June 1936), popularly known as Maxim Gorky (russian: Макси́м Го́рький, link=no), was a Russian writer and social ...

, appeared in ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'' in 1947. He continued to publish in that magazine at various times in his career and was serving on its editorial board at his death in 1987.

1950s

In 1953, Baldwin's first novel, '' Go Tell It on the Mountain'', a semi-autobiographical ''bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a ''Bildungsroman'' (, plural ''Bildungsromane'', ) is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood ( coming of age), in which character change is impo ...

'' was published. He began writing it when he was only seventeen and first published it in Paris. His first collection of essays, ''Notes of a Native Son

''Notes of a Native Son'' is a collection of ten essays by James Baldwin, published in 1955, mostly tackling issues of race in America and Europe. The volume, as his first non-fiction book, compiles essays of Baldwin that had previously appear ...

'' appeared two years later. He continued to experiment with literary forms throughout his career, publishing poetry and plays as well as the fiction and essays for which he was known.

Baldwin's second novel, ''Giovanni's Room

''Giovanni's Room'' is a 1956 novel by James Baldwin. Stryker, Susan. ''Queer Pulp: Perverted Passions from the Golden Age of the Paperback'' (San Francisco: Chronicle Books, 2001), p. 104. The book focuses on the events in the life of an Americ ...

'', caused great controversy when it was first published in 1956 due to its explicit homoerotic content. Baldwin again resisted labels with the publication of this work. Despite the reading public's expectations that he would publish works dealing with African American experiences, ''Giovanni's Room'' is predominantly about white characters.

''Go Tell It on the Mountain'' (1953)

Baldwin sent the manuscript for ''Go Tell It on the Mountain'' from Paris to New York publishing houseAlfred A. Knopf

Alfred A. Knopf, Inc. () is an American publishing house that was founded by Alfred A. Knopf Sr. and Blanche Knopf in 1915. Blanche and Alfred traveled abroad regularly and were known for publishing European, Asian, and Latin American writers in ...

on February 26, 1952, and Knopf expressed interest in the novel several months later. To settle the terms of his association with Knopf, Baldwin sailed back to the United States on the ''SS'' Île de France in April, where Themistocles Hoetis and Dizzy Gillespie

John Birks "Dizzy" Gillespie (; October 21, 1917 – January 6, 1993) was an American jazz trumpeter, bandleader, composer, educator and singer. He was a trumpet virtuoso and improviser, building on the virtuosic style of Roy Eldridge but addi ...

were coincidentally also voyaging—his conversations with both on the ship were extensive. After his arrival in New York, Baldwin spent much of the next three months with his family, whom he had not seen in almost three years. Baldwin grew particularly close to his younger brother, David Jr., and served as best man at David's wedding on June 27. Meanwhile, Baldwin agreed to rewrite parts of ''Go Tell It on the Mountain'' in exchange for a $250 advance ($ today) and a further $750 ($ today) paid when the final manuscript was completed. When Knopf accepted the revision in July, they sent the remainder of the advance, and Baldwin was soon to have his first published novel. In the interim, Baldwin published excerpts of the novel in two publications: one excerpt was published as "Exodus" in ''American Mercury

''The American Mercury'' was an American magazine published from 1924Staff (Dec. 31, 1923)"Bichloride of Mercury."''Time''. to 1981. It was founded as the brainchild of H. L. Mencken and drama critic George Jean Nathan. The magazine featured wri ...

'' and the other as "Roy's Wound" in ''New World Writing

''New World Writing'' was a paperback magazine, a literary anthology series published by New American Library's Mentor imprint from 1951 until 1960, then J. B. Lippincott & Co.'s Keystone from volume/issue 16 (1960) to the last volume, 22, in 19 ...

''. Baldwin set sail back to Europe on August 28 and ''Go Tell It on the Mountain'' was published in May 1953.

''Go Tell It on the Mountain'' was the product of Baldwin's years of work and exploration since his first attempt at a novel in 1938. In rejecting the ideological manacles of protest literature and the presupposition he thought inherent to such works that "in Negro life there exists no tradition, no field of manners, no possibility of ritual or intercourse", Baldwin sought in ''Go Tell It on the Mountain'' to emphasize that the core of the problem was "not that the Negro has no tradition but that there has as yet arrived no sensibility sufficiently profound and tough to make this tradition articulate." Baldwin biographer David Leeming draws parallels between Baldwin's undertaking in ''Go Tell It on the Mountain'' and James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

's endeavor in ''A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man

''A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man'' is the first novel of Irish writer James Joyce. A ''Künstlerroman'' written in a modernist style, it traces the religious and intellectual awakening of young Stephen Dedalus, Joyce's fictional alter ...

'': to "encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race." Baldwin himself drew parallels between Joyce's flight from his native Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and his own run from Harlem, and Baldwin read Joyce's tome in Paris in 1950, but in Baldwin's ''Go Tell It on the Mountain'', it would be the Black American "uncreated conscience" at the heart of the project.

The novel is a bildungsroman

In literary criticism, a ''Bildungsroman'' (, plural ''Bildungsromane'', ) is a literary genre that focuses on the psychological and moral growth of the protagonist from childhood to adulthood ( coming of age), in which character change is impo ...

that peers into the inward struggles of protagonist John Grimes, the illegitimate son of Elizabeth Grimes, to claim his own soul as it lays on the "threshing floor

Threshing (thrashing) was originally "to tramp or stamp heavily with the feet" and was later applied to the act of separating out grain by the feet of people or oxen and still later with the use of a flail. A threshing floor is of two main type ...

"—a clear allusion to another John, the Baptist born of another Elizabeth

Elizabeth or Elisabeth may refer to:

People

* Elizabeth (given name), a female given name (including people with that name)

* Elizabeth (biblical figure), mother of John the Baptist

Ships

* HMS ''Elizabeth'', several ships

* ''Elisabeth'' (sch ...

. John's struggle is a metaphor for Baldwin's own struggle between escaping the history and heritage that made him, awful though it may be, and plunging deeper into that heritage, to the bottom of his people's sorrows, before he can shuffle off his psychic chains, "climb the mountain", and free himself. John's family members and most of the characters in the novel are blown north in the winds of the Great Migration in search of the American Dream and all are stifled. Florence, Elizabeth, and Gabriel are denied love's reach because racism assured that they could not muster the kind of self-respect that love requires. Racism drives Elizabeth's lover, Richard, to suicide—Richard will not be the last Baldwin character to die thus for that same reason. Florence's lover Frank is destroyed by searing self-hatred of his own Blackness. Gabriel's abuse of the women in his life is downstream from his society's emasculation of him, with mealy-mouthed religiosity only a hypocritical cover.