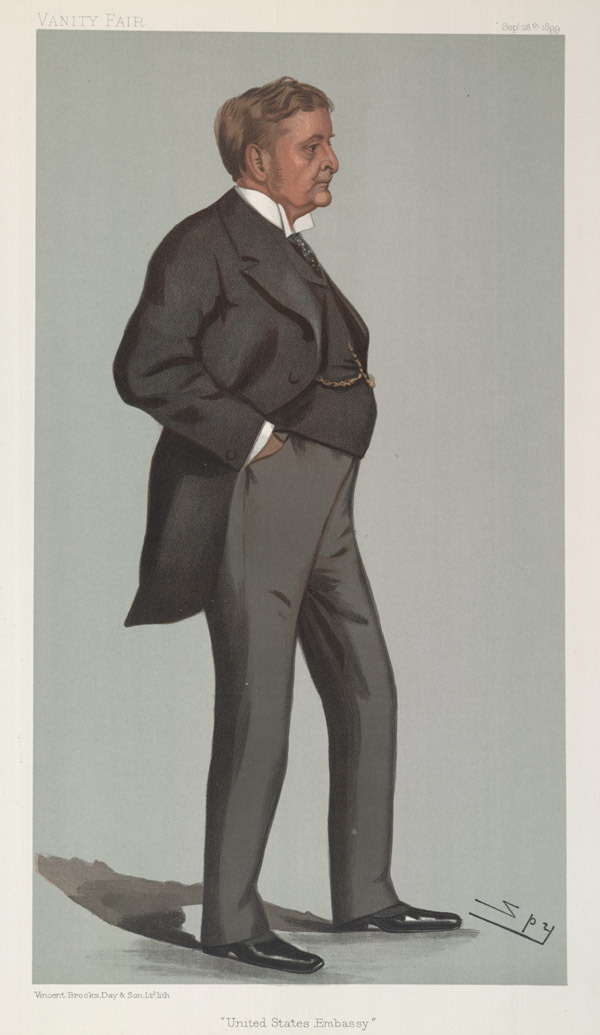

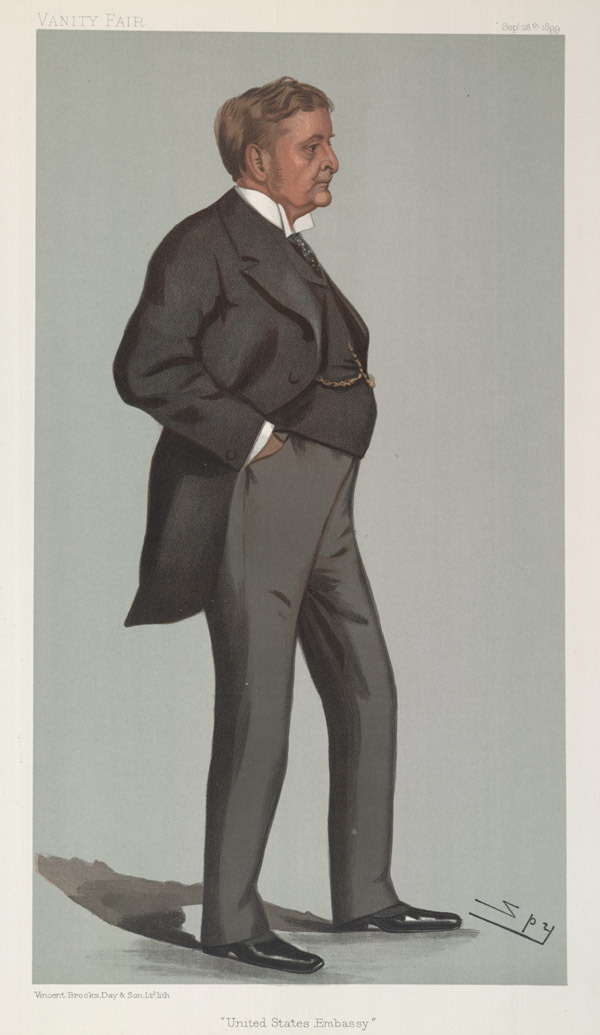

Joseph Hodges Choate on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Joseph Hodges Choate (January 24, 1832 – May 14, 1917) was an American lawyer and diplomat. Choate was associated with many of the most famous

After graduation from law school, Choate was admitted first to the Massachusetts in 1855, followed by admission to the New York bar in 1856, after which he entered the law office of Scudder & Carter in

After graduation from law school, Choate was admitted first to the Massachusetts in 1855, followed by admission to the New York bar in 1856, after which he entered the law office of Scudder & Carter in

On October 16, 1861, he married

On October 16, 1861, he married

litigation

-

A lawsuit is a proceeding by a party or parties against another in the civil court of law. The archaic term "suit in law" is found in only a small number of laws still in effect today. The term "lawsuit" is used in reference to a civil actio ...

s in American legal history, including the Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

cases, the Chinese exclusion cases, the Isaac H. Maynard election returns case, the Income Tax Suit

''Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Company'', 157 U.S. 429 (1895), ''affirmed on rehearing'', 158 U.S. 601 (1895), was a landmark case of the Supreme Court of the United States. In a 5-to-4 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the income tax ...

, and the Samuel J. Tilden, Jane Stanford

Jane Elizabeth Lathrop Stanford (August 25, 1828 – February 28, 1905) was an American philanthropist, co-founder of Stanford University in 1885 (opened 1891) along with her husband, Leland Stanford, as a memorial to their only child, Leland ...

, and Alexander Turney Stewart will cases. In the public sphere, he was influential in the founding of the Metropolitan Museum of Art

The Metropolitan Museum of Art of New York City, colloquially "the Met", is the largest art museum in the Americas. Its permanent collection contains over two million works, divided among 17 curatorial departments. The main building at 1000 ...

.

Early life

Choate was born inSalem, Massachusetts

Salem ( ) is a historic coastal city in Essex County, Massachusetts, located on the North Shore of Greater Boston. Continuous settlement by Europeans began in 1626 with English colonists. Salem would become one of the most significant seaports tr ...

on January 24, 1832. He was the son of Margaret Manning (''née'' Hodges) Choate and physician George Choate. Among his siblings were William Gardner Choate

William Gardner Choate (August 30, 1830 – November 14, 1920) was a United States district judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

Education and career

Choate was born in Salem, Massachusetts, the son o ...

, a United States district judge

The United States district courts are the trial courts of the United States federal judiciary, U.S. federal judiciary. There is one district court for each United States federal judicial district, federal judicial district, which each cover o ...

of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York

The United States District Court for the Southern District of New York (in case citations, S.D.N.Y.) is a United States district court, federal trial court whose geographic jurisdiction encompasses eight counties of New York (state), New York ...

, Dr. George Cheyne Shattuck Choate

George Cheyne Shattuck Choate (March 30, 1827 – June 4, 1896) was an American physician and the founder of Choate House, a psychiatric sanatorium.

Biography

He was born in Salem, Massachusetts, on March 30, 1827, to Margaret Man ...

, and a sister, Caroline Choate.

His father's first cousin (his first cousin once removed) was Rufus Choate

Rufus Choate (October 1, 1799July 13, 1859) was an American lawyer, orator, and Senator who represented Massachusetts as a member of the Whig Party. He is regarded as one of the greatest American lawyers of the 19th century, arguing over a th ...

, a U.S. Representative

The United States House of Representatives, often referred to as the House of Representatives, the U.S. House, or simply the House, is the lower chamber of the United States Congress, with the Senate being the upper chamber. Together they c ...

and U.S. Senator

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and powe ...

from Massachusetts. His paternal grandparents were George Choate and Susanna Choate, and his maternal grandparents were Gamaliel Hodges and Sarah (née Williams) Hodges.

Choate graduated from Harvard College

Harvard College is the undergraduate college of Harvard University, an Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636, Harvard College is the original school of Harvard University, the oldest institution of higher lea ...

in 1852 and Harvard Law School

Harvard Law School (Harvard Law or HLS) is the law school of Harvard University, a private research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1817, it is the oldest continuously operating law school in the United States.

Each class ...

in 1854.

Career

After graduation from law school, Choate was admitted first to the Massachusetts in 1855, followed by admission to the New York bar in 1856, after which he entered the law office of Scudder & Carter in

After graduation from law school, Choate was admitted first to the Massachusetts in 1855, followed by admission to the New York bar in 1856, after which he entered the law office of Scudder & Carter in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

His success in his profession was immediate, and in 1860 he became junior partner in the firm of Evarts, Southmayd & Choate, the senior partner in which was William M. Evarts

William Maxwell Evarts (February 6, 1818February 28, 1901) was an American lawyer and statesman from New York who served as U.S. Secretary of State, U.S. Attorney General and U.S. Senator from New York. He was renowned for his skills as a li ...

. This firm and its successor, that of Evarts, Choate & Beaman, remained for many years among the leading law firms of New York and of the country, the activities of both being national rather than local.

During these busy years, Choate was associated with many of the most famous legal cases in American legal history, including the Tilden, Alexander Turney Stewart, and Jane Stanford

Jane Elizabeth Lathrop Stanford (August 25, 1828 – February 28, 1905) was an American philanthropist, co-founder of Stanford University in 1885 (opened 1891) along with her husband, Leland Stanford, as a memorial to their only child, Leland ...

will cases, the Kansas

Kansas () is a state in the Midwestern United States. Its capital is Topeka, and its largest city is Wichita. Kansas is a landlocked state bordered by Nebraska to the north; Missouri to the east; Oklahoma to the south; and Colorado to the ...

prohibition

Prohibition is the act or practice of forbidding something by law; more particularly the term refers to the banning of the manufacture, storage (whether in barrels or in bottles), transportation, sale, possession, and consumption of alcoholic ...

cases, the Chinese exclusion cases (in which he argued against the law's validity), the Isaac H. Maynard election returns case, and the Income Tax Suit

''Pollock v. Farmers' Loan & Trust Company'', 157 U.S. 429 (1895), ''affirmed on rehearing'', 158 U.S. 601 (1895), was a landmark case of the Supreme Court of the United States. In a 5-to-4 decision, the Supreme Court struck down the income tax ...

. In 1871, he became a member of the Committee of Seventy

The Committee of Seventy is an independent, non-partisan advocate for better government in Philadelphia that works to achieve clean and effective government, better elections, and informed and engaged citizens. Founded in 1904, it is a nonprofit ...

in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

, which was instrumental in breaking up the Tweed Ring

William Magear Tweed (April 3, 1823 – April 12, 1878), often erroneously referred to as William "Marcy" Tweed (see below), and widely known as "Boss" Tweed, was an American politician most notable for being the political boss of Tammany ...

, and later assisted in the prosecution of the indicted officials. He served as president of the American Bar Association

The American Bar Association (ABA) is a voluntary bar association of lawyers and law students, which is not specific to any jurisdiction in the United States. Founded in 1878, the ABA's most important stated activities are the setting of acad ...

, the New York State Bar Association

The New York State Bar Association (NYSBA) is a voluntary bar association for the state of New York. The mission of the association is to cultivate the science of jurisprudence; promote reform in the law; facilitate the administration of justice ...

, and the New York City Bar Association

The New York City Bar Association (City Bar), founded in 1870, is a voluntary association of lawyers and law students. Since 1896, the organization, formally known as the Association of the Bar of the City of New York, has been headquartered in a ...

. In the retrial of the General Fitz-John Porter case, he obtained a reversal of the decision of the original court-martial.

His greatest reputation was won perhaps in cross-examination. In politics, he allied himself with the Republican Party on its organization, being a frequent speaker in presidential campaigns, beginning with that of 1856. He never held political office, although he was a candidate for the Republican U.S. senatorial nomination for New York against Senator Thomas C. Platt in 1897. During this time he was a "true believer" in the cause of Cuban independence, being heavily informed and swayed by Cuban exiles in New York City, including Tomás Estrada Palma

Tomás Estrada Palma (c. July 6, 1832 – November 4, 1908) was a Cuban politician, the president of the Cuban Republican in Arms during the Ten Years' War, and the first President of Cuba, between May 20, 1902, and September 28, 1906.

His collate ...

. In 1894, he was president of the New York state constitutional convention.

U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom

He was appointed, byPresident McKinley

William McKinley (January 29, 1843September 14, 1901) was the 25th president of the United States, serving from 1897 until Assassination of William McKinley, his assassination in 1901. As a politician he led a realignment that made his Hist ...

, U.S. Ambassador to the United Kingdom

The United States ambassador to the United Kingdom (known formally as the ambassador of the United States to the Court of St James's) is the official representative of the president of the United States and the American government to the monarc ...

to succeed John Hay

John Milton Hay (October 8, 1838July 1, 1905) was an American statesman and official whose career in government stretched over almost half a century. Beginning as a private secretary and assistant to Abraham Lincoln, Hay's highest office was Un ...

in 1899, and remained in this position after Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

's ascendancy to the presidency until the spring of 1905. In England, he won great personal popularity, and accomplished much in fostering the good relations of the two great English-speaking powers. He represented the president at the funeral of Queen Victoria. He was one of the representatives of the United States at the Second Hague Peace Conference

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaty, treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions w ...

in 1907.

Later life

Upon the outbreak of theWorld War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, he ardently supported the cause of the Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

. He severely criticized President Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the History of the Democratic Party (United States), Demo ...

's hesitation to recommend America's immediate cooperation, but shortly before his death retracted his criticism. He was chairman of the mayor

In many countries, a mayor is the highest-ranking official in a municipal government such as that of a city or a town. Worldwide, there is a wide variance in local laws and customs regarding the powers and responsibilities of a mayor as well a ...

's committee in New York for entertaining the British and French commissions in 1917. His death was hastened by the physical strain of his constant activities in this connection.

Personal life

On October 16, 1861, he married

On October 16, 1861, he married Caroline Dutcher Sterling Choate

Caroline Dutcher Sterling Choate (June 16, 1837 – November 12, 1929, generally styled Mrs. Joseph H. Choate) was an artist, educational reformer, suffragist, philanthropist and socialite. She was the wife of lawyer and U.S. Ambassador to the Un ...

(1837–1929), who had been born in Salisbury, Connecticut

Salisbury () is a town situated in Litchfield County, Connecticut, United States. The town is the northwesternmost in the state of Connecticut; the Massachusetts-New York-Connecticut tri-state marker is located at the northwest corner of the town ...

. She was the daughter of Caroline Mary (née Dutcher) Sterling and Frederick Augustine Sterling and a distant relative of Frederick A. Sterling. Caroline was an artist and an advocate for women's education, helping to establish both Brearley School

The Brearley School is an all-girls private school in New York City, located on the Upper East Side neighborhood in the borough of Manhattan. The school is divided into lower (kindergarten – grade 4), middle (grades 5–8) and upper (grades 9 ...

and Barnard College

Barnard College of Columbia University is a private women's liberal arts college in the borough of Manhattan in New York City. It was founded in 1889 by a group of women led by young student activist Annie Nathan Meyer, who petitioned Columbia ...

.

Joseph and Caroline were the parents of five children, two of whom predeceased their parents:

* Ruluff Sterling Choate (September 24, 1864 – April 5, 1884)

* George Choate (born January 28, 1867 – 1937)

* Josephine Choate (January 9, 1869 – July 20, 1896)

* Mabel Choate

Mabel Choate (December 26, 1870 – December 11, 1958) was an American gardener, collector and philanthropist.

Biography

Born on December 26, 1870, in New York City, Mabel Choate was the fourth of five children of Joseph Choate and Caroline ...

(December 26, 1870 – 1958), who did not marry and became a gardener and philanthropist.

* Joseph Hodges Choate Jr. (February 2, 1876 – 1968), who married Cora Lyman Oliver, daughter of General Robert Shaw Oliver, in 1903.

The family owned a large country house, known as Naumkeag

Naumkeag is the former country estate of noted New York City lawyer Joseph Hodges Choate and Caroline Dutcher Sterling Choate, located at 5 Prospect Hill Road, Stockbridge, Massachusetts. The estate's centerpiece is a 44-room, Shingle Style ...

, which was designed by Stanford White

Stanford White (November 9, 1853 – June 25, 1906) was an American architect. He was also a partner in the architectural firm McKim, Mead & White, one of the most significant Beaux-Arts firms. He designed many houses for the rich, in additio ...

and is today open to the public as a nonprofit museum in Stockbridge, Massachusetts

Stockbridge is a town in Berkshire County in Western Massachusetts, United States. It is part of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 2,018 at the 2020 census. A year-round resort area, Stockbridge is h ...

.

Choate died on May 14, 1917 at his residence, 8 East 63rd Street in Manhattan.

His funeral was held on May 17 at St. Bartholomew's Church in New York, where it was attended by the British Ambassador, Sir Cecil Spring-Rice

Sir Cecil Arthur Spring Rice, (27 February 1859 – 14 February 1918) was a British diplomat who served as British Ambassador to the United States from 1912 to 1918, as which he was responsible for the organisation of British efforts to end ...

, the French Minister of Education, M. Hovelacque, and the Assistant Secretary of State, William Phillips William Phillips may refer to:

Entertainment

* William Phillips (editor) (1907–2002), American editor and co-founder of ''Partisan Review''

* William T. Phillips (1863–1937), American author

* William Phillips (director), Canadian film-make ...

, among many others. He was buried in the Stockbridge Cemetery in Stockbridge, Massachusetts

Stockbridge is a town in Berkshire County in Western Massachusetts, United States. It is part of the Pittsfield, Massachusetts, Metropolitan Statistical Area. The population was 2,018 at the 2020 census. A year-round resort area, Stockbridge is h ...

. Memorial services were held on May 22 in London, England, and on May 31 at Trinity Church on Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for t ...

.

Descendants

Through his granddaughter, Helen Choate Platt (1906–1974), he is the great-grandfather of diplomatNicholas Platt

Nicholas Platt (born March 10, 1936) is an American diplomat who served as U.S. Ambassador Extraordinary and Plenipotentiary to Pakistan, Philippines, Zambia, and as a high level diplomat in Canada, China, Hong Kong, and Japan. He is the former p ...

(b. 1936), the former U.S. Ambassador to Zambia

The history of ambassadors of the United States to Zambia began in 1964.

Until 1964 Zambia had been a colony of the British Empire, first as Northern Rhodesia and then as a part of the Federation of Rhodesia and Nyasaland. On December 31, 1963, ...

, the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

, and Pakistan

Pakistan ( ur, ), officially the Islamic Republic of Pakistan ( ur, , label=none), is a country in South Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, fifth-most populous country, with a population of almost 24 ...

; and the great-great-grandfather of actor Oliver Platt

Oliver Platt (born January 12, 1960) is a Canadian-born American actor. He is known for his starring roles in many films such as ''Flatliners'' (1990), ''Beethoven'' (1992), ''Indecent Proposal'', ''The Three Musketeers'' (both 1993), ''Executiv ...

(b. 1960).

Honors and legacy

He was awarded anhonorary doctorate

An honorary degree is an academic degree for which a university (or other degree-awarding institution) has waived all of the usual requirements. It is also known by the Latin phrases ''honoris causa'' ("for the sake of the honour") or ''ad hon ...

(LL.D.

Legum Doctor (Latin: “teacher of the laws”) (LL.D.) or, in English, Doctor of Laws, is a doctorate-level academic degree in law or an honorary degree, depending on the jurisdiction. The double “L” in the abbreviation refers to the early ...

) by the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

in March 1900; another LL.D. from Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

in October 1901, during celebrations for the bicentenary of the university; an honorary doctorate ( D.C.L.) by the University of Oxford

, mottoeng = The Lord is my light

, established =

, endowment = £6.1 billion (including colleges) (2019)

, budget = £2.145 billion (2019–20)

, chancellor ...

in June 1902; and an honorary degree by the University of St Andrews

(Aien aristeuein)

, motto_lang = grc

, mottoeng = Ever to ExcelorEver to be the Best

, established =

, type = Public research university

Ancient university

, endowment ...

in October 1902.

In 1919, two years after his death, members of the Harvard Club of New York City established the Joseph Hodges Choate Memorial Fellowship at Harvard University

Harvard University is a private Ivy League research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Founded in 1636 as Harvard College and named for its first benefactor, the Puritan clergyman John Harvard, it is the oldest institution of higher le ...

to commemorate his life and legacy. It is awarded each year to a student from the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

on the recommendation of the Cambridge Vice-Chancellor

A chancellor is a leader of a college or university, usually either the executive or ceremonial head of the university or of a university campus within a university system.

In most Commonwealth of Nations, Commonwealth and former Commonwealth n ...

for study in any Department of Harvard University. The Fellow resides in the Choate Suite in John Winthrop House and their name is recorded on a board in the House Dining Hall.

Published works

* * * * * *References

External links

* * * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Choate, Joseph Hodges 1832 births 1917 deaths Harvard Law School alumni People from Stockbridge, Massachusetts Ambassadors of the United States to the United Kingdom Choate family People from Salem, Massachusetts Presidents of the New York City Bar Association New York (state) Republicans Carnegie Endowment for International Peace Harvard College alumni Burials at Woodlawn Cemetery (Bronx, New York) 19th-century American diplomats 20th-century American diplomats