Joseph Cherniavsky on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

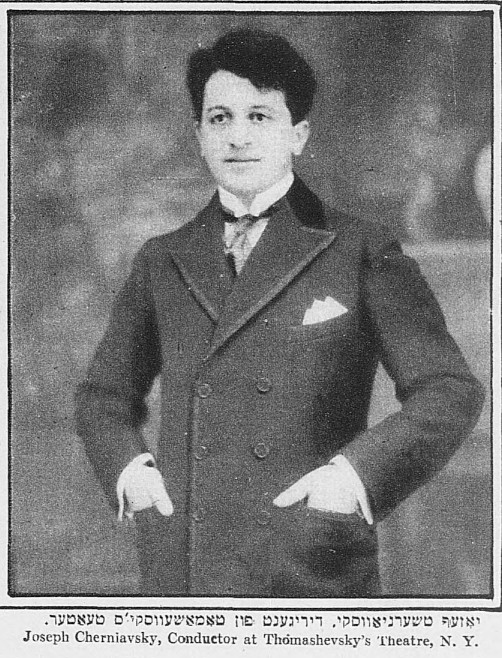

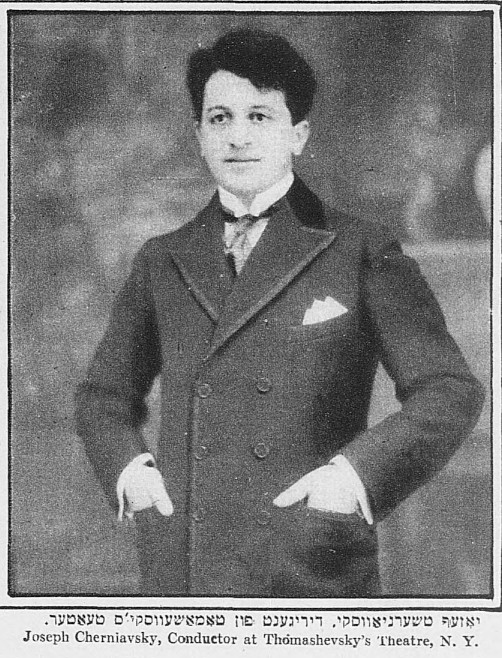

Joseph Cherniavsky ( yi, יוסף טשערניאַװסקי) (c. 1890-1959) was a Jewish American

Joseph Cherniavsky ( yi, יוסף טשערניאַװסקי) (c. 1890-1959) was a Jewish American

Joseph Cherniavsky ( yi, יוסף טשערניאַװסקי) (c. 1890-1959) was a Jewish American

Joseph Cherniavsky ( yi, יוסף טשערניאַװסקי) (c. 1890-1959) was a Jewish American cellist

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a bowed (sometimes plucked and occasionally hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually tuned in perfect fifths: from low to high, C2, G2, D3 ...

, theatre and film composer, orchestra director, and recording artist. He wrote for the Yiddish theatre, made some of the earliest novelty recordings mixing American popular music, Jazz

Jazz is a music genre that originated in the African-American communities of New Orleans, Louisiana in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with its roots in blues and ragtime. Since the 1920s Jazz Age, it has been recognized as a major ...

and klezmer

Klezmer ( yi, קלעזמער or ) is an instrumental musical tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe. The essential elements of the tradition include dance tunes, ritual melodies, and virtuosic improvisations played for l ...

in the mid-1920s, was also musical director at Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

in 1928-1929, and had a long career in radio and musical theatre.

Biography

Early life

Josef Leo Cherniavsky was born inLubny

Lubny ( uk, Лубни́, ), is a city in Poltava Oblast (province) of central Ukraine. Serving as the administrative center of Lubny Raion (district), the city itself is administratively incorporated as a city of oblast significance and does n ...

, Poltava Governorate

The Poltava Governorate (russian: Полтавская губерния, Poltavskaya guberniya; ua, Полтавська Губернія, translit=Poltavska huberniia) or Poltavshchyna was a Governorate (Russia), gubernia (also called a provin ...

, Russian Empire

The Russian Empire was an empire and the final period of the Russian monarchy from 1721 to 1917, ruling across large parts of Eurasia. It succeeded the Tsardom of Russia following the Treaty of Nystad, which ended the Great Northern War. ...

around 1890. The exact date of his birth is unclear; a citizenship application by his wife in 1928 said March 29, 1889; he himself said on US military documents that it was March 29, 1890, while the Lexicon of Yiddish Theatre says it was March 31, 1894. His father was a klezmer

Klezmer ( yi, קלעזמער or ) is an instrumental musical tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe. The essential elements of the tradition include dance tunes, ritual melodies, and virtuosic improvisations played for l ...

musician, as was his grandfather. Although the Lexicon of Yiddish Theatre claims that his grandfather was the prototype for Sholem Aleichem

)

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Pereiaslav, Russian Empire

, death_date =

, death_place = New York City, U.S.

, occupation = Writer

, nationality =

, period =

, genre = Novels, sh ...

's fictional klezmer Stempenyu

Stempenyu ( yi, סטעמפּעניו, 1822–79) was the popular name of Iosif Druker (), a klezmer violin virtuoso, bandleader and composer from Berdychiv, Russian Empire. He was one of a handful of celebrity nineteenth century Jewish folk violin ...

(in real life, a violinist named Yosele Druker), it seems that his grandfather was actually Peysekh Fidelman, father of the violinists Alexander Fiedemann. In his youth, Joseph studied in a Cheder

A ''cheder'' ( he, חדר, lit. "room"; Yiddish pronunciation ''kheyder'') is a traditional primary school teaching the basics of Judaism and the Hebrew language.

History

''Cheders'' were widely found in Europe before the end of the 18th ...

and also played drums in his father's ensemble at weddings. He soon began to learn the cello

The cello ( ; plural ''celli'' or ''cellos'') or violoncello ( ; ) is a Bow (music), bowed (sometimes pizzicato, plucked and occasionally col legno, hit) string instrument of the violin family. Its four strings are usually intonation (music), t ...

from his father, and then moved to Odessa

Odesa (also spelled Odessa) is the third most populous city and municipality in Ukraine and a major seaport and transport hub located in the south-west of the country, on the northwestern shore of the Black Sea. The city is also the administrativ ...

where he continued to learn the instrument from his uncle Alexander Fiedemann. He then obtained a government scholarship and traveled to study at the Saint Petersburg Conservatory

The N. A. Rimsky-Korsakov Saint Petersburg State Conservatory (russian: Санкт-Петербургская государственная консерватория имени Н. А. Римского-Корсакова) (formerly known as th ...

under such figures as Nicolai Rimsky-Korsakov

Nikolai Andreyevich Rimsky-Korsakov . At the time, his name was spelled Николай Андреевичъ Римскій-Корсаковъ. la, Nicolaus Andreae filius Rimskij-Korsakov. The composer romanized his name as ''Nicolas Rimsk ...

and Alexander Glazunov

Alexander Konstantinovich Glazunov; ger, Glasunow (, 10 August 1865 – 21 March 1936) was a Russian composer, music teacher, and conductor of the late Russian Romantic period. He was director of the Saint Petersburg Conservatory between 1905 ...

. He graduated in 1911 with a gold medal as a Cellist and Conductor and then went to Leipzig

Leipzig ( , ; Upper Saxon: ) is the most populous city in the German state of Saxony. Leipzig's population of 605,407 inhabitants (1.1 million in the larger urban zone) as of 2021 places the city as Germany's eighth most populous, as wel ...

where he finished his studies under Julius Klengel

Julius Klengel (24 September 1859 – 27 October 1933) was a German cellist who is most famous for his études and solo pieces written for the instrument. He was the brother of Paul Klengel. A member of the Gewandhaus Orchestra of Leipzig at fif ...

.

Musical career in Russia

While still a music student, Cherniavsky had been a member of a Jewish chamber music ensemble founded by clarinetistSimeon Bellison

Simeon Bellison (September 4, 1881 – May 4, 1953), born in Moscow, was a clarinetist and composer. He became a naturalised American after settling in the US in 1921. Bellison established an early clarinet choir (including women) in the United St ...

called the Moscow Quintet, which was heavily influenced by the Society for Jewish Folk Music

The Jewish art music movement began at the end of the 19th century in Russia, with a group of Russian Jewish classical composers dedicated to preserving Jewish folk music and creating a new, characteristically Jewish genre of classical music. The ...

. Cherniavsky had collected Jewish melodies in villages during that era and contributed them to the development of the ensemble's repertoire. Upon finishing his studies in 1914 he returned to Saint Petersburg and rejoined the ensemble, played in some Russian orchestras, and began to compose. In 1918, with the support of the aforementioned Society, Bellison founded a new chamber ensemble called the Zimro Ensemble, also known as the Palestine Chamber Music Ensemble: ZIMRO. The ensemble added a piano and its lead violinist was Jacob Mestechkin, a student of Leopold Auer

Leopold von Auer ( hu, Auer Lipót; June 7, 1845July 15, 1930) was a Hungarian violinist, academic, conductor, composer, and instructor. Many of his students went on to become prominent concert performers and teachers.

Early life and career

Au ...

. The ensemble's goal was to embark on tours of Eastern Russia, Asia, and the United States, with their final goal being Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

. Their repertoire consisted not only of standard Western chamber repertoire, but also compositions by Russian Jewish composers such as Alexander Krein

Alexander Abramovich Krein (; 20 October 1883 in Nizhny Novgorod – 25 April 1951 in Staraya Ruza, Moscow Oblast) was a Soviet composer.

Background

The Krein family was steeped in the klezmer tradition; his father Abram (who moved to Russia fr ...

, Solomon Rosowsky

Solomon (Salomo) Rosowsky (1878, Riga –1962) was a cantor (hazzan) and composer, and son of the Rigan cantor, Baruch Leib Rosowsky.

Early life

Rosowsky began to study music only after he graduated from the University of Kyiv, with a degree in ...

, Joseph Achron

Joseph Yulyevich Achron, also seen as Akhron (Russian: Иосиф Юльевич Ахрон, Hebrew: יוסף אחרון) (May 1, 1886April 29, 1943) was a Russian-born Jewish composer and violinist, who settled in the United States. His preoccu ...

, and Mikhail Gnessin Mikhail Fabianovich Gnessin (russian: Михаил Фабианович Гнесин; sometimes transcribed ''Gnesin''; 2 February .S. 21 January18835 May 1957)Sitsky, Larry. (1994) ''Music of the Repressed Russian Avant-Garde, 1900–1929,'' pp.24 ...

.

The Zimro Ensemble left Petrograd

Saint Petersburg ( rus, links=no, Санкт-Петербург, a=Ru-Sankt Peterburg Leningrad Petrograd Piter.ogg, r=Sankt-Peterburg, p=ˈsankt pʲɪtʲɪrˈburk), formerly known as Petrograd (1914–1924) and later Leningrad (1924–1991), i ...

in March 1918, passing through the Ural Mountains

The Ural Mountains ( ; rus, Ура́льские го́ры, r=Uralskiye gory, p=ʊˈralʲskʲɪjə ˈɡorɨ; ba, Урал тауҙары) or simply the Urals, are a mountain range that runs approximately from north to south through western ...

into the East. They toured Eastern Russia, China, and the Dutch East Indies, finally ending up in the United States in August 1919. The ensemble stayed at least two years in the United States, performing at the congress of the American Zionist Federation in September 1919 and later at Carnegie Hall

Carnegie Hall ( ) is a concert venue in Midtown Manhattan in New York City. It is at 881 Seventh Avenue (Manhattan), Seventh Avenue, occupying the east side of Seventh Avenue between West 56th Street (Manhattan), 56th and 57th Street (Manhatta ...

and various other venues. Sergei Prokofiev

Sergei Sergeyevich Prokofiev; alternative transliterations of his name include ''Sergey'' or ''Serge'', and ''Prokofief'', ''Prokofieff'', or ''Prokofyev''., group=n (27 April .S. 15 April1891 – 5 March 1953) was a Russian composer, p ...

composed his Overture on Hebrew Themes

Sergei Prokofiev wrote the Overture on Hebrew Themes, Op. 34, in 1919 while he was in the United States. It is scored for the rare combination of clarinet, string quartet and piano. Fifteen years later the composer prepared a version for chambe ...

for the Zimro Ensemble, who debuted it in February 1920 in New York, with Prokofiev as guest pianist. However, rather than continue with their stated goal of fundraising for a artistic centre in Mandate Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 i ...

, gradually the group broke apart, and at least three of its members (Cherniavsky, Mestechkin and Bellison) settled in the US and started music careers there.

Klezmer, theater and vaudeville in the United States

In 1919, while the Zimro ensemble was still playing concerts, Cherniavsky wrote the music for a play called ''Moishe der Klezmer'' which was performed byMaurice Schwartz

Maurice Schwartz, born Avram Moishe Schwartz (June 18, 1890 – May 10, 1960), His encounter with Schwartz led him to enter the world of the Yiddish Theatre more prominently as a composer and arranger. They collaborated on the first American adaption of  After The Dybbuk closed, Cherniavsky rewrote some of the material into a new

After The Dybbuk closed, Cherniavsky rewrote some of the material into a new

During the

During the

Joseph Cherniavsky recordings

in the

Joseph Cherniavsky listed recordings

in the

Joseph and Lara Cherniavsky personal archive

in the

The Dybbuk

''The Dybbuk'', or ''Between Two Worlds'' (russian: Меж двух миров �ибук}, trans. ''Mezh dvukh mirov ibuk'; yi, צווישן צוויי וועלטן - דער דִבּוּק, ''Tsvishn Tsvey Veltn – der Dibuk'') is a play by ...

which played to great success in 1921–22.

After The Dybbuk closed, Cherniavsky rewrote some of the material into a new

After The Dybbuk closed, Cherniavsky rewrote some of the material into a new vaudeville

Vaudeville (; ) is a theatrical genre of variety entertainment born in France at the end of the 19th century. A vaudeville was originally a comedy without psychological or moral intentions, based on a comical situation: a dramatic composition ...

act which he variously called Joseph Cherniavsky's Yiddish-American Jazz Band, the Hasidic-American Jazz Band, etc. The orchestra members would dress as Cossacks

The Cossacks , es, cosaco , et, Kasakad, cazacii , fi, Kasakat, cazacii , french: cosaques , hu, kozákok, cazacii , it, cosacchi , orv, коза́ки, pl, Kozacy , pt, cossacos , ro, cazaci , russian: казаки́ or ...

or Hasidim

Ḥasīd ( he, חסיד, "pious", "saintly", "godly man"; plural "Hasidim") is a Jewish honorific, frequently used as a term of exceptional respect in the Talmudic and early medieval periods. It denotes a person who is scrupulous in his observ ...

. Cherniavsky's wife Lara, a pianist, was also involved in leading rehearsals and possibly coming up with some of the arrangements. Famous klezmers who played in this orchestra included Naftule Brandwein

Naftule Brandwein, or Naftuli Brandwine, ( yi, נפתלי בראַנדװײַן, 1884–1963) was an Austrian-born Jewish American Klezmer musician, clarinetist, bandleader and recording artist active from the 1910s to the 1940s. Along with ...

, Dave Tarras

Dave Tarras (c. 1895 – February 13, 1989) was a Ukrainian-born American klezmer clarinetist and bandleader, a celebrated klezmer musician, instrumental in Klezmer revival.

Biography Early life

Tarras was born David Tarasiuk in Teplyk, Ukrai ...

and Shloimke Beckerman

Shloimke Beckerman (c. 1884–1974) also known as Samuel Beckerman, was a klezmer clarinetist and bandleader in New York City in the early twentieth century; he was a contemporary of Dave Tarras and Naftule Brandwein. He was the father of Sid Bec ...

. The act toured the United States for three years. In 1924 his recordings for Pathé Records

Pathé Records was an international record company and label and producer of phonographs, based in France, and active from the 1890s through the 1930s.

Early years

The Pathé record business was founded by brothers Charles and Émile Pathé, ...

as the Cherniavsky Jewish Jazz Band were marketed as the first "Jewish Jazz Band" in the country. Dave Tarras later said that the music had not really been Jazz, but just "nice theatre music". Klezmer researcher Jeffrey Wollock describes the act's music as "neither jazz nor true klezmer, his arrangements were modernistic, theatrical treatments of Jewish content." By 1925 the orchestra disbanded.

Cherniavsky had also continued to compose for the Yiddish Theatre after The Dybbuk. He went to work for Boris Thomashefsky

Boris Thomashefsky (russian: Борис Пинхасович Томашевский, sometimes written Thomashevsky, Thomaschevsky, etc.; yi, באָריס טאָמאשעבסקי) (1868–1939), born Boruch-Aharon Thomashefsky, was a Ukrainian-b ...

and at various venues including the National Theatre, Irving Place Theatre, and Thomashefsky's Broadway Theatre. One 1922 Thomashefsky production he wrote the music for was called Dance, Song and Wine. In 1926 he was made composer and conductor at the newly opening Public Theatre at Second Avenue and 4th Street. However, his composing for Yiddish music appears to have ended during this period; his last copyrighted piece of this kind appears to be ''Der kaddish tsu mayn shtam'' (1925), and the Lexicon of Yiddish Theatre notes that he retired from the theatre after his stay at the Public Theatre in 1926-7.

Cherniavsky was also present in the early years of Yiddish language

Yiddish (, or , ''yidish'' or ''idish'', , ; , ''Yidish-Taytsh'', ) is a West Germanic language historically spoken by Ashkenazi Jews. It originated during the 9th century in Central Europe, providing the nascent Ashkenazi community with a ver ...

radio in the United States. He was musical director of what may have been the first regularly scheduled Yiddish music hour at WFBH in 1926. That program, called the Libby Hotel Program, ran from May to August of that year and may have featured Dave Tarras

Dave Tarras (c. 1895 – February 13, 1989) was a Ukrainian-born American klezmer clarinetist and bandleader, a celebrated klezmer musician, instrumental in Klezmer revival.

Biography Early life

Tarras was born David Tarasiuk in Teplyk, Ukrai ...

on the clarinet. In late 1927 he once again tried to launch a vaudeville tour, this time under the name Cherniavsky and his Orientals, specializing in "Chassidic and Caucasian music".

Mainstream American music career

After leaving the Yiddish theatre around 1927, Cherniavsky gravitated towards mainstream English music, whether in radio, film or theatre. In February 1928 he launched a new radio series with Josef Cherniavsky's Colonials Orchestra at the Colony Theatre in New York; they had made their stage debut at the opening ofThe Chinese Parrot

''The Chinese Parrot'' (1926) is the second novel in the Charlie Chan series of mystery novels by Earl Derr Biggers. It is the first in which Chan travels from Hawaii to mainland California, and involves a crime whose exposure is hastened by t ...

. Later in 1928 Carl Laemmle

Carl Laemmle (; born Karl Lämmle; January 17, 1867 – September 24, 1939) was a film producer and the co-founder and, until 1934, owner of Universal Pictures. He produced or worked on over 400 films.

Regarded as one of the most important o ...

appointed him musical director at Universal Studios

Universal Pictures (legally Universal City Studios LLC, also known as Universal Studios, or simply Universal; common metonym: Uni, and formerly named Universal Film Manufacturing Company and Universal-International Pictures Inc.) is an Ameri ...

and Cherniavsky relocated to Hollywood

Hollywood usually refers to:

* Hollywood, Los Angeles, a neighborhood in California

* Hollywood, a metonym for the cinema of the United States

Hollywood may also refer to:

Places United States

* Hollywood District (disambiguation)

* Hollywood, ...

. One of the few films he scored during this time was Show Boat

''Show Boat'' is a musical with music by Jerome Kern and book and lyrics by Oscar Hammerstein II. It is based on Edna Ferber's best-selling 1926 novel of the same name. The musical follows the lives of the performers, stagehands and dock worke ...

. However, he was not there long; he left in July 1929 before his contract was finished.

Cherniavsky spent the 1930s working contracts in various cities in radio, television and theatre. In 1930 he briefly worked in Toronto

Toronto ( ; or ) is the capital city of the Canadian province of Ontario. With a recorded population of 2,794,356 in 2021, it is the most populous city in Canada and the fourth most populous city in North America. The city is the ancho ...

at the Uptown Theatre. He spent a few years running an orchestra called the Sympho-Syncopators. Then he was musical director of the Chicago Theatre

The Chicago Theatre, originally known as the Balaban and Katz Chicago Theatre, is a landmark theater located on North State Street in the Loop area of Chicago, Illinois. Built in 1921, the Chicago Theatre was the flagship for the Balaban an ...

around 1933-35. In 1936 he launched a television series called The Musical Cameraman on NBC

The National Broadcasting Company (NBC) is an Television in the United States, American English-language Commercial broadcasting, commercial television network, broadcast television and radio network. The flagship property of the NBC Enterta ...

. Around 1938, Cherniavsky and his family relocated to Cincinnati

Cincinnati ( ) is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Hamilton County. Settled in 1788, the city is located at the northern side of the confluence of the Licking and Ohio rivers, the latter of which marks the state line wit ...

. Joseph took up a musical director post at WLW Cincinnati.

During the

During the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he continued to work in radio, leaving WLW Cincinnati for WOV New York in 1941 and then WEII CBS Radio

CBS Radio was a radio broadcasting company and radio network operator owned by CBS Corporation and founded in 1928, with consolidated radio station groups owned by CBS and Westinghouse Broadcasting/Group W since the 1920s, and Infinity Broadc ...

in Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

in 1942. In the early 1940s, he also ran another orchestra called the Boy Meets Girl Orchestra.

In 1949 Cherniavsky spent time in Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

, South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring countri ...

where he was musical director for a production of Oklahoma!

''Oklahoma!'' is the first musical theater, musical written by the duo of Rodgers and Hammerstein. The musical is based on Lynn Riggs' 1931 play, ''Green Grow the Lilacs (play), Green Grow the Lilacs''. Set in farm country outside the town of ...

as well as some Ballet

Ballet () is a type of performance dance that originated during the Italian Renaissance in the fifteenth century and later developed into a concert dance form in France and Russia. It has since become a widespread and highly technical form of ...

productions.

After 1949, he continued in music as the conductor of the Saginaw Civic Symphony from 1951 to 1959.

Personal life

Joseph's wife was a pianist named Lara (née Lieberman) was born in Nikolaev, where they were married in June 1917. Their son William was born in June 1918 in Russia and their daughter Salomea ( Sally Fox) was born in California in December 1929. Sally would go on to become a professional photographer and editor of books of art about women's everyday lives in history, while William became a television scriptwriter in Hollywood. Cherniavsky died on 3 November 1959 in New York City.Legacy

During theKlezmer revival

Klezmer ( yi, קלעזמער or ) is an instrumental musical tradition of the Ashkenazi Jews of Central and Eastern Europe. The essential elements of the tradition include dance tunes, ritual melodies, and virtuosic improvisations played for l ...

, which began in the late 1970s, there was renewed interest in the klezmer and Jewish compositions of Cherniavsky's early career. The Klezmorim

The Klezmorim, founded in Berkeley, California, in 1975, was the world's first klezmer revival band, widely credited with spearheading the global renaissance of klezmer (Eastern European Yiddish instrumental music) in the 1970s and 1980s.Thompson ...

covered one of his songs on their self-titled 1984 album. A band led by Pete Sokolow in the 1980s called the Original Klezmer Jazz Band incorporated Cherniavsky's material into their repertoire. In 1993, one of his 1920s recordings appeared on the compilation ''Klezmer Pioneers (European And American Recordings 1905-1952)'' by Rounder Records, and in the same year on the compilation ''Mazel Tov: more music of the Jewish people'' by Intersound, Inc. In 1999 another track of his was reissued on ''Oytsres Treasures: klezmer music, 1908-1996'' by Wergo records.

References

External links

Joseph Cherniavsky recordings

in the

Florida Atlantic University

Florida Atlantic University (Florida Atlantic or FAU) is a Public university, public research university with its main campus in Boca Raton, Florida, and satellite campuses in Dania Beach, Florida, Dania Beach, Davie, Florida, Davie, Fort Lauderd ...

Judaica sound archive

Joseph Cherniavsky listed recordings

in the

Discography of American Historical Recordings

The Discography of American Historical Recordings (DAHR) is a database of master recordings made by American record companies during the 78rpm era. The DAHR provides some of these original recordings, free of charge, via audio streaming, along with ...

*

Joseph and Lara Cherniavsky personal archive

in the

YIVO

YIVO (Yiddish: , ) is an organization that preserves, studies, and teaches the cultural history of Jewish life throughout Eastern Europe, Germany, and Russia as well as orthography, lexicography, and other studies related to Yiddish. (The word '' ...

collection

{{DEFAULTSORT:Cherniavsky, Joseph

1890 births

1959 deaths

20th-century American composers

American classical cellists

Jewish American classical musicians

Jewish American film score composers

Jewish Ukrainian musicians

Klezmer musicians

People from Lubny

Soviet emigrants to the United States

Year of birth uncertain

20th-century cellists