John Hershey on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Richard Hersey (June 17, 1914 – March 24, 1993) was an American writer and journalist. He is considered one of the earliest practitioners of the so-called

Soon afterward John Hersey began discussions with

Soon afterward John Hersey began discussions with

/ref> Soon after writing ''Hiroshima'', the former war correspondent began publishing mostly fiction. Hersey's war novel ''The Wall'' (1950) was presented as a rediscovered journal recording the genesis and destruction of the

New Journalism

New Journalism is a style of news writing and journalism, developed in the 1960s and 1970s, that uses literary techniques unconventional at the time. It is characterized by a subjective perspective, a literary style reminiscent of long-form non ...

, in which storytelling

Storytelling is the social and cultural activity of sharing stories, sometimes with improvisation, theatrics or embellishment. Every culture has its own stories or narratives, which are shared as a means of entertainment, education, cultural pre ...

techniques of fiction are adapted to non-fiction reportage. In 1999, Hersey's account of the aftermath of the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima, Japan

is a Prefectures of Japan, prefecture of Japan located in the Chūgoku region of Honshu. Hiroshima Prefecture has a population of 2,811,410 (1 June 2019) and has a geographic area of 8,479 km² (3,274 sq mi). Hiroshima Prefecture borders Okayama ...

, was adjudged the finest piece of American journalism of the 20th century by a 36-member panel associated with New York University

New York University (NYU) is a private research university in New York City. Chartered in 1831 by the New York State Legislature, NYU was founded by a group of New Yorkers led by then-Secretary of the Treasury Albert Gallatin.

In 1832, the ...

's journalism department.

Background

Hersey was born inTientsin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popul ...

, China, the son of Grace Baird and Roscoe Hersey, Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

for the YMCA

YMCA, sometimes regionally called the Y, is a worldwide youth organization based in Geneva, Switzerland, with more than 64 million beneficiaries in 120 countries. It was founded on 6 June 1844 by George Williams in London, originally ...

in Tientsin. Hersey learned to speak Chinese before he spoke English. Later he based his novel, '' The Call'' (1985), on the lives of his parents and several other missionaries of their generation.

John Hersey was a descendant of William Hersey (or Hercy, as the family name was then spelled) of Reading, Berkshire

Reading ( ) is a town and borough in Berkshire, Southeast England, southeast England. Located in the Thames Valley at the confluence of the rivers River Thames, Thames and River Kennet, Kennet, the Great Western Main Line railway and the M4 mot ...

, England. William Hersey was one of the first settlers of Hingham, Massachusetts

Hingham ( ) is a town in metropolitan Greater Boston on the South Shore of the U.S. state of Massachusetts in northern Plymouth County. At the 2020 census, the population was 24,284. Hingham is known for its colonial history and location on B ...

in 1635.

Hersey returned to the United States with his family when he was ten years old. He attended public school in Briarcliff Manor, New York

Briarcliff Manor () is a suburban village in Westchester County, New York, north of New York City. It is on of land on the east bank of the Hudson River, geographically shared by the towns of Mount Pleasant and Ossining. Briarcliff Manor inc ...

, including Briarcliff High School

Briarcliff High School (BHS) is a public secondary school in Briarcliff Manor, New York that serves students in grades 9– 12. It is the only high school in the Briarcliff Manor Union Free School District, sharing its campus with Briarcliff Midd ...

for two years. At Briarcliff, he became his troop's first Eagle Scout

Eagle Scout is the highest achievement or rank attainable in the Scouts BSA program of the Boy Scouts of America (BSA). Since its inception in 1911, only four percent of Scouts have earned this rank after a lengthy review process. The Eagle Sc ...

. Later he attended the Hotchkiss School

The Hotchkiss School is a coeducational University-preparatory school#North America, preparatory school in Lakeville, Connecticut, United States. Hotchkiss is a member of the Eight Schools Association and Ten Schools Admissions Organization. It i ...

. He studied at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, where he was a member of the Skull and Bones Society

Skull and Bones, also known as The Order, Order 322 or The Brotherhood of Death, is an undergraduate senior secret student society at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. The oldest senior class society at the university, Skull and Bone ...

along with classmates Brendan Gill

Brendan Gill (October 4, 1914 – December 27, 1997) was an American journalist. He wrote for ''The New Yorker'' for more than 60 years. Gill also contributed film criticism for ''Film Comment'', wrote about design and architecture for Architectu ...

and Richard A. Moore.

Hersey lettered in football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

at Yale, where he was coached by Ducky Pond

Raymond W. "Ducky" Pond (February 17, 1902 – August 25, 1982) was an American football and baseball player and football coach. He was the head football coach at Yale University from 1934 to 1940, and at Bates College in 1941 and from 1946 to 195 ...

, Greasy Neale

Alfred Earle "Greasy" Neale (November 5, 1891 – November 2, 1973) was an American football and baseball player and coach.

Early life and playing career

Neale was born in Parkersburg, West Virginia. Although writers eventually assumed that Nea ...

, and Gerald Ford

Gerald Rudolph Ford Jr. ( ; born Leslie Lynch King Jr.; July 14, 1913December 26, 2006) was an American politician who served as the 38th president of the United States from 1974 to 1977. He was the only president never to have been elected ...

. He was a teammate of Larry Kelley

Lawrence Morgan Kelley (May 30, 1915 – June 27, 2000) was an American football player. He played at the end position for the Yale Bulldogs football program from 1934 to 1936. He was the captain of the 1936 Yale Bulldogs football team that ...

and Clint Frank

Clinton E. Frank (September 13, 1915 – July 7, 1992) was an American football player and advertising executive. He played halfback for Yale University, where he won both the Heisman Trophy and Maxwell Award in 1937. In 1954, he founded t ...

, Yale's two Heisman Trophy

The Heisman Memorial Trophy (usually known colloquially as the Heisman Trophy or The Heisman) is awarded annually to the most outstanding player in college football. Winners epitomize great ability combined with diligence, perseverance, and hard ...

winners. He subsequently was selected as a Mellon Fellow for graduate study at the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

.

Career

After his time at Cambridge, Hersey got a summer job as private secretary and driver for authorSinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

during 1937. He chafed at those duties, and that autumn he began work for ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'', for which he was hired after writing an essay on the magazine's dismal quality. Two years later (1939) he was transferred to ''Times Chongqing

Chongqing ( or ; ; Sichuanese dialects, Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), Postal Romanization, alternately romanized as Chungking (), is a Direct-administered municipalities of China, municipality in Southwes ...

bureau. In 1940, William Saroyan

William Saroyan (; August 31, 1908 – May 18, 1981) was an Armenian-American novelist, playwright, and short story writer. He was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1940, and in 1943 won the Academy Award for Best Story for the film ''The ...

lists him among "contributing editors" at ''Time'' in the play, ''Love's Old Sweet Song''.

During World War II, ''Newsweekly

A news magazine is a typed, printed, and published magazine, radio or television program, usually published weekly, consisting of articles about current events. News magazines generally discuss stories, in greater depth than do newspapers or ne ...

'' correspondent Hersey covered the fighting in Europe and Asia. He wrote articles for ''Time'' and ''Life'' magazines. He accompanied Allied troops on their invasion

An invasion is a military offensive in which large numbers of combatants of one geopolitical entity aggressively enter territory owned by another such entity, generally with the objective of either: conquering; liberating or re-establishing con ...

of Sicily

(man) it, Siciliana (woman)

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 = Ethnicity

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographi ...

, survived four airplane crashes, and was commended by the Secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

for his role in helping evacuate wounded soldiers from Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the seco ...

. Before writing ''Hiroshima'', Hersey published his novel ''Of Men and War'', an account of war stories seen through the eyes of soldiers rather than a war correspondent. One of the stories in Hersey's novel was inspired by future President John F. Kennedy

John Fitzgerald Kennedy (May 29, 1917 – November 22, 1963), often referred to by his initials JFK and the nickname Jack, was an American politician who served as the 35th president of the United States from 1961 until assassination of Joh ...

, who also happened to be a former paramour of Hersey's wife Frances Ann. During the Solomon Islands campaign

The Solomon Islands campaign was a major campaign of the Pacific War of World War II. The campaign began with Japanese landings and occupation of several areas in the British Solomon Islands and Bougainville, in the Territory of New Guinea, du ...

, Kennedy commanded a PT-109 PT1 may refer to:

* 486958 Arrokoth (New Horizons PT1), a Kuiper belt object and selected target for a flyby of the New Horizons probe

* Pratt & Whitney PT1, a free-piston gas-turbine engine

* Consolidated PT-1 Trusty, a 1930s USAAS primary trainer ...

that was cut in half by a Japanese destroyer. He led the rescue of his crew, personally towing the injured to safety.

After the war, during the winter of 1945–46, Hersey was in Japan, reporting for ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'' on the reconstruction of the devastated country, when he found a document written by a Jesuit missionary

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

who had survived the atomic bomb dropped on Hiroshima. The journalist visited the missionary, who introduced him to other survivors.

Reporting from Hiroshima

Soon afterward John Hersey began discussions with

Soon afterward John Hersey began discussions with William Shawn

William Shawn (''né'' Chon; August 31, 1907 – December 8, 1992) was an American magazine editor who edited ''The New Yorker'' from 1952 until 1987.

Early life and education

Shawn was born William Chon on August 31, 1907, in Chicago, Illinoi ...

, an editor for ''The New Yorker'', about a lengthy piece on the previous summer's bombing. Hersey proposed a story that would convey the cataclysmic narrative through individuals who survived.

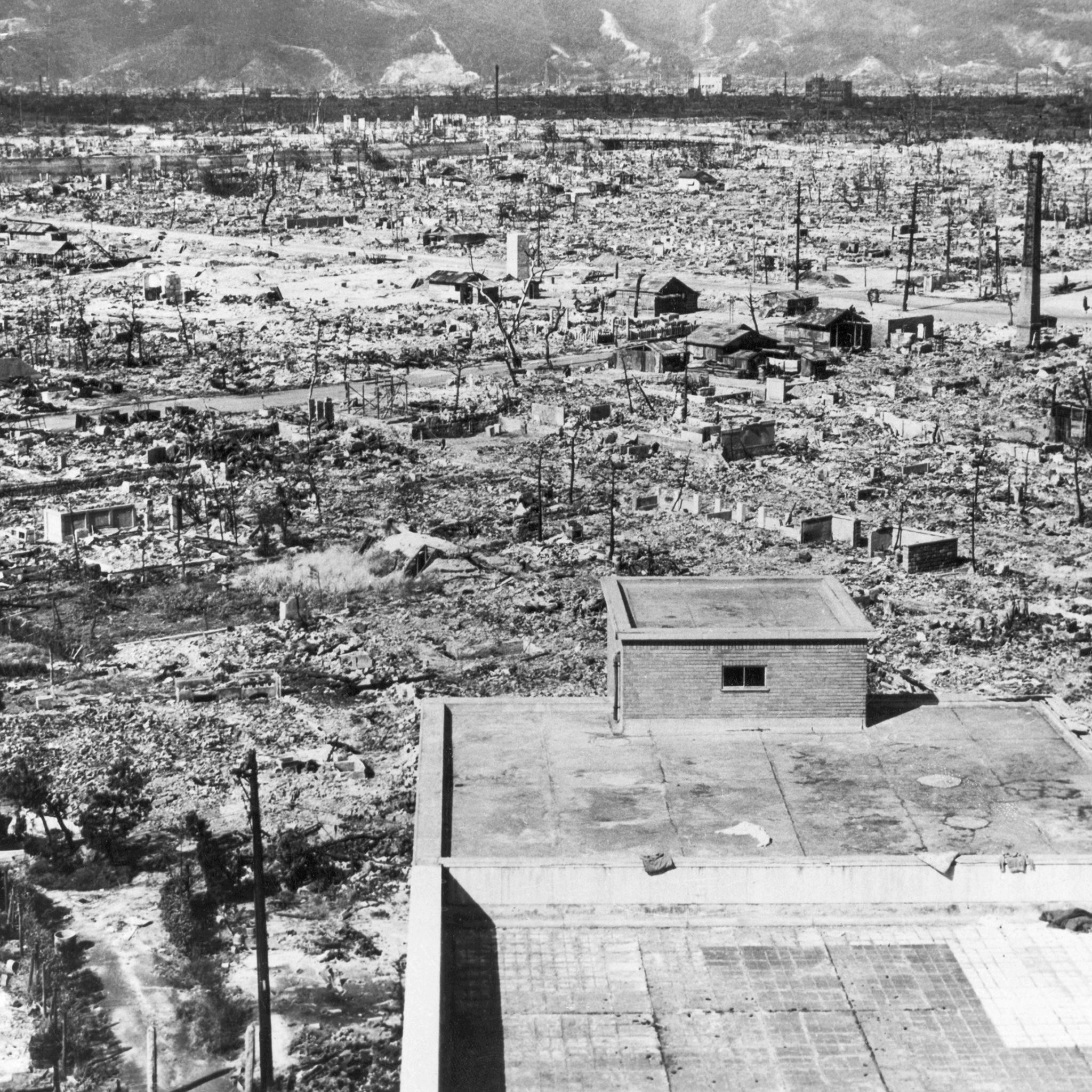

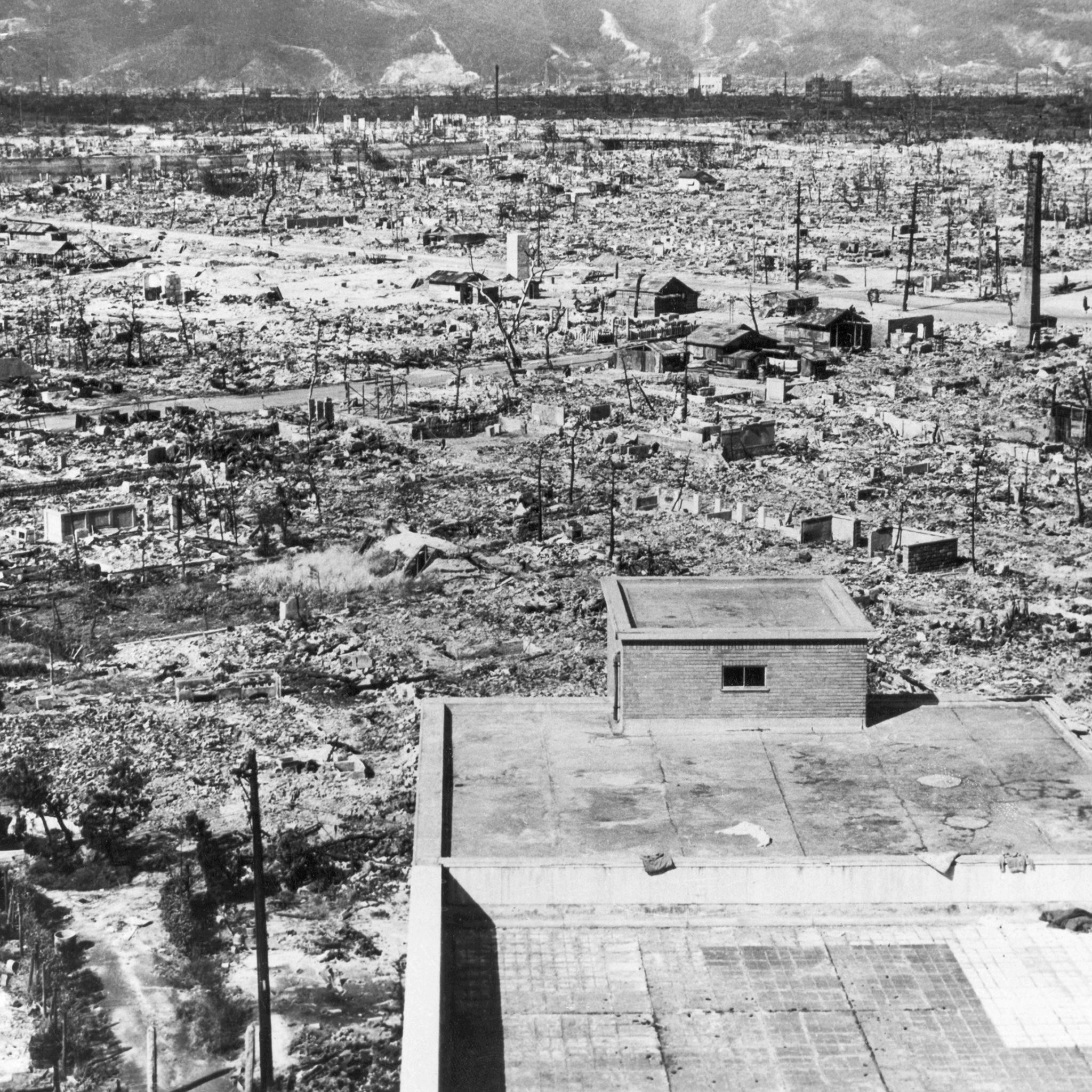

In May 1946, Hersey traveled to Japan, where he spent three weeks doing research and interviewing survivors. He returned to America during late June and began writing the stories of six Hiroshima survivors: a German Jesuit priest, a widowed seamstress, two doctors, a minister, and a young woman who worked in a factory.

The resulting piece was his most notable work, the 31,000-word article "Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

", which was published in the August 31, 1946, issue of ''The New Yorker''. The story dealt with the atomic bomb

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions (thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

dropped on that Japanese city on August 6, 1945, and its effects on the six survivors. The article occupied almost the entire issue of the magazine – something ''The New Yorker'' had never done before.

Later books and college master's job

Hersey often decried theNew Journalism

New Journalism is a style of news writing and journalism, developed in the 1960s and 1970s, that uses literary techniques unconventional at the time. It is characterized by a subjective perspective, a literary style reminiscent of long-form non ...

, although he had helped create it. He would probably have disagreed that his "Hiroshima" article should be described as New Journalism. Later, the ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

Hersey came to feel that some elements of the New Journalism of the 1970s were not rigorous enough about fact and reporting. After publication of ''Hiroshima'', Hersey noted that "the important 'flashes' and 'bulletins' are already forgotten by the time yesterday morning's paper is used to line the trash can. The things we remember are emotions and impressions and illusions and images and characters: the elements of fiction.""Awakening a Sleeping Giant the Call", R. Z. Sheppard, ''TIME'', May 6, 1985/ref> Soon after writing ''Hiroshima'', the former war correspondent began publishing mostly fiction. Hersey's war novel ''The Wall'' (1950) was presented as a rediscovered journal recording the genesis and destruction of the

Warsaw Ghetto

The Warsaw Ghetto (german: Warschauer Ghetto, officially , "Jewish Residential District in Warsaw"; pl, getto warszawskie) was the largest of the Nazi ghettos during World War II and the Holocaust. It was established in November 1940 by the G ...

, the largest of the Jewish ghetto

A ghetto, often called ''the'' ghetto, is a part of a city in which members of a minority group live, especially as a result of political, social, legal, environmental or economic pressure. Ghettos are often known for being more impoverished t ...

s established by Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

during the Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; a ...

. The book became a bestseller. It also won the National Jewish Book Award

The Jewish Book Council (Hebrew: ), founded in 1944, is an organization encouraging and contributing to Jewish literature.Sidney Hillman Foundation Journalism Award.

In 1950, during the

Original "Hiroshima" article

by John Hersey in ''

BBC article on the impact of Hersey's "Hiroshima", marking the 70th anniversary of its publication

*

John Hersey High School

*

* ttp://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2012/02/16/archives/famous-contributors-john-hersey.html John Hersey's "A Life for a Vote"in ''

"Hiroshima" by John Hersey

– academic research * * John Hersey Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Hersey, John 1914 births 1993 deaths 20th-century American novelists American anti–Vietnam War activists American essayists American expatriates in China American male journalists American magazine editors American male novelists American non-fiction writers Deaths from cancer in Florida Fellows of Clare College, Cambridge Hotchkiss School alumni Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners The New Yorker people American war correspondents of World War II Novelists from Connecticut Novelists from Florida Novelists from Massachusetts Time (magazine) people Yale University alumni Yale University faculty People from Briarcliff Manor, New York American male essayists Writers from Tianjin Children of American missionaries in China 20th-century essayists 20th-century American male writers

Red Scare

A Red Scare is the promotion of a widespread fear of a potential rise of communism, anarchism or other leftist ideologies by a society or state. The term is most often used to refer to two periods in the history of the United States which ar ...

, Hersey was investigated by the FBI

The Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) is the domestic Intelligence agency, intelligence and Security agency, security service of the United States and its principal Federal law enforcement in the United States, federal law enforcement age ...

for possible Communist sympathies related to his past speeches and financial contributions, for example to the American Civil Liberties Union

The American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) is a nonprofit organization founded in 1920 "to defend and preserve the individual rights and liberties guaranteed to every person in this country by the Constitution and laws of the United States". T ...

. The activities of his brother and other reporters were also investigated.

His article "Why Do Students Bog Down on First R? A Local Committee Sheds Light on a National Problem: Reading" (1954), about the dullness of grammar school readers in an issue of ''Life'' magazine, inspired Dr. Seuss's children's story ''The Cat in the Hat

''The Cat in the Hat'' is a 1957 children's book written and illustrated by the American author Theodor Geisel, using the pen name Dr. Seuss. The story centers on a tall anthropomorphic cat who wears a red and white-striped top hat and a red bow ...

''. He also criticized the school system in his novel ''The Child Buyer

''The Child Buyer'' is John Hersey's 1960 novel about a project to engineer super-intelligent persons for a project whose aim is never definitely stated. Told entirely in the form of minutes from a State Senate Standing Committee, it relates th ...

'' (1960), a speculative fiction

Speculative fiction is a term that has been used with a variety of (sometimes contradictory) meanings. The broadest interpretation is as a category of fiction encompassing genres with elements that do not exist in reality, recorded history, na ...

.

Hersey's first novel ''A Bell for Adano

''A Bell for Adano'' (1945) is a film directed by Henry King and starring John Hodiak and Gene Tierney. It was adapted from the 1944 novel of the same title by John Hersey, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1945. In his review of the ...

'', about the Allied occupation of a Sicilian town during World War II, won the Pulitzer Prize for the Novel

The Pulitzer Prize for Fiction is one of the seven American Pulitzer Prizes that are annually awarded for Letters, Drama, and Music. It recognizes distinguished fiction by an American author, preferably dealing with American life, published during ...

in 1945. It was adapted that year as a movie of the same name, ''A Bell for Adano

''A Bell for Adano'' (1945) is a film directed by Henry King and starring John Hodiak and Gene Tierney. It was adapted from the 1944 novel of the same title by John Hersey, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1945. In his review of the ...

'', directed by Henry King, and featuring John Hodiak

John Hodiak ( ; April 16, 1914 – October 19, 1955) was an American actor who worked in radio, stage and film.

Early life

Hodiak was born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, the son of Anna (Pogorzelec) and Walter Hodiak. He was of Ukrainian and ...

and Gene Tierney

Gene Eliza Tierney (November 19, 1920 – November 6, 1991) was an American film and stage actress. Acclaimed for her great beauty, she became established as a leading lady. Tierney was best known for her portrayal of the title character in the ...

. His 1956 short novel, ''A Single Pebble'', recounts the journey of a young American engineer traveling up the Yangtze

The Yangtze or Yangzi ( or ; ) is the longest river in Asia, the third-longest in the world, and the longest in the world to flow entirely within one country. It rises at Jari Hill in the Tanggula Mountains (Tibetan Plateau) and flows ...

on a river junk during the 1920s. He learns that his romantic concepts of China brings disaster. In the novel ''White Lotus'' (1965), Hersey explores the African-American experience prior to civil rights, as reflected in an alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, altern ...

in which white Americans are enslaved by the Chinese after losing "the Great War" to them.

Hersey wrote '' The Algiers Motel Incident'' (1968), a non-fiction work about a racially motivated shooting of three young African-American men by police during the 12th Street Riot

The 1967 Detroit Riot, also known as the 12th Street Riot or Detroit Rebellion, was the bloodiest of the urban riots in the United States during the "Long, hot summer of 1967". Composed mainly of confrontations between Black residents and the De ...

in Detroit, Michigan

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at ...

, in July 1967.

From 1965 to 1970, Hersey was master of Pierson College

Pierson College is a residential college at Yale University in New Haven, Connecticut. Opened in 1933, it is named for Abraham Pierson, a founder and the first rector of the Collegiate School, the college later known as Yale. With just under 500 ...

, one of twelve residential college

A residential college is a division of a university that places academic activity in a community setting of students and faculty, usually at a residence and with shared meals, the college having a degree of autonomy and a federated relationship wi ...

s at Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

. His outspoken activism and early opposition to the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

made him controversial with alumni but admired by many students. After the trial of the Black Panthers

The Black Panther Party (BPP), originally the Black Panther Party for Self-Defense, was a Marxism-Leninism, Marxist-Leninist and Black Power movement, black power political organization founded by college students Bobby Seale and Huey P. New ...

in New Haven

New Haven is a city in the U.S. state of Connecticut. It is located on New Haven Harbor on the northern shore of Long Island Sound in New Haven County, Connecticut and is part of the New York City metropolitan area. With a population of 134,02 ...

, Connecticut, Hersey wrote ''Letter to the Alumni'' (1970). He sympathetically addressed civil rights and anti-war activism – and attempted to explain them to sometimes aggravated alumni.

Hersey also pursued an unusual sideline: he operated the college's small letterpress printing

Letterpress printing is a technique of relief printing. Using a printing press, the process allows many copies to be produced by repeated direct impression of an inked, raised surface against sheets or a continuous roll of paper. A worker comp ...

operation, which he sometimes used to publish broadsides. During 1969 he printed an elaborate broadside of an Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_ NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style"> ...

quote for Elting E. Morison

Elting Elmore Morison (December 14, 1909, Milwaukee, Wisconsin – April 20, 1995, Peterborough, New Hampshire) was an American historian of technology, military biographer, author of nonfiction books, and essayist. He was an MIT professor and th ...

, a Yale history professor and fellow residential college master.

For 18 years Hersey tught two writing courses, in fiction and non-fiction, to Yale undergraduates. Hersey taught his last class in fiction writing at Yale during 1984. In his individual sessions with undergraduates to discuss their work, the Pulitzer Prize-winning author was sometimes known to write his comments in the margin. After discussing his suggestion with the student, he would take out his pencil and erase the comment. As Master of Pierson College, he hosted his old boss Henry Luce

Henry Robinson Luce (April 3, 1898 – February 28, 1967) was an American magazine magnate who founded ''Time'', ''Life'', ''Fortune'', and ''Sports Illustrated'' magazine. He has been called "the most influential private citizen in the America ...

– with whom Hersey had become reconciled after their dispute years prior – when Luce spoke to the college's undergraduates. ''Time'' founder Luce was a notoriously dull public speaker, and his address to the Pierson undergraduates was no exception. Afterward Luce privately revealed to Hersey for the first time that he and his wife Clare Boothe Luce

Clare Boothe Luce ( Ann Clare Boothe; March 10, 1903 – October 9, 1987) was an American writer, politician, U.S. ambassador, and public conservative figure. A versatile author, she is best known for her 1936 hit play '' The Women'', which h ...

had taken LSD

Lysergic acid diethylamide (LSD), also known colloquially as acid, is a potent psychedelic drug. Effects typically include intensified thoughts, emotions, and sensory perception. At sufficiently high dosages LSD manifests primarily mental, vi ...

while supervised by a physician. Hersey later said that he was relieved that Luce had saved that particular revelation for a more private audience.

In 1969 Hersey donated the services of his bulldog 'Oliver' as mascot for the Yale football team, but he was concerned about his dog's interest level as Handsome Dan XI (the Yale bulldog's traditional name). Hersey wondered aloud "whether Oliver would stay awake for two hours." That year, with the new mascot, the Yale team finished the season with a 7–2 record.

During 1985 John Hersey returned to Hiroshima, where he reported and wrote ''Hiroshima: The Aftermath'', a follow-up to his original account. ''The New Yorker'' published Hersey's update in its July 15, 1985 issue. The article was subsequently appended to a newly revised edition of the book. "What has kept the world safe from the bomb since 1945 has not been deterrence, in the sense of fear of specific weapons, so much as it's been memory," wrote Hersey. "The memory of what happened at Hiroshima."

Anne Fadiman

Anne Fadiman (born August 7, 1953) is an American essayist and reporter. Her interests include literary journalism, essays, memoir, and autobiography. She has received the National Book Critics Circle Award, the Los Angeles Times Book Prize for ...

described Hersey as a "compulsive plagiarist". For instance, she said he used complete paragraphs from the James Agee

James Rufus Agee ( ; November 27, 1909 – May 16, 1955) was an American novelist, journalist, poet, screenwriter and film critic. In the 1940s, writing for ''Time Magazine'', he was one of the most influential film critics in the United States. ...

biography by Laurence Bergreen

Laurence Bergreen (born February 4, 1950 in New York City) is an American historian and author.

Career

After graduating from Harvard University in 1972, Bergreen worked in journalism, academia and broadcasting before publishing his first biogr ...

in his own ''New Yorker'' essay about Agee. She said that half of his book, ''Men on Bataan,'' came from work filed for ''Time'' by Melville Jacoby

Melville may refer to:

Places

Antarctica

*Cape Melville (South Shetland Islands)

*Melville Peak, King George Island

*Melville Glacier, Graham Land

*Melville Highlands, Laurie Island

* Melville Point, Marie Byrd Land

Australia

*Cape Melville, Q ...

and his wife, Annalee Jacoby Fadiman.

Death

A longtime resident of Vineyard Haven, Martha's Vineyard, Massachusetts – chronicled in his 1987 work ''Blues'' – John Hersey died at his winter home inKey West, Florida

Key West ( es, Cayo Hueso) is an island in the Straits of Florida, within the U.S. state of Florida. Together with all or parts of the separate islands of Sigsbee Park, Dredgers Key, Fleming Key, Sunset Key, and the northern part of Stock Isla ...

, on March 24, 1993, at the compound he and his wife shared with his friend, writer Ralph Ellison

Ralph Waldo Ellison (March 1, 1913 – April 16, 1994) was an American writer, literary critic, and scholar best known for his novel ''Invisible Man'', which won the National Book Award in 1953. He also wrote ''Shadow and Act'' (1964), a collecti ...

. Ellison's novel ''Invisible Man

''Invisible Man'' is a novel by Ralph Ellison, published by Random House in 1952. It addresses many of the social and intellectual issues faced by African Americans in the early twentieth century, including black nationalism, the relationship b ...

'' was one of Hersey's favorite works, and he often urged students in his fiction-writing seminar to study Ellison's storytelling techniques and descriptive prose. Hersey's death was front-page news in the next day's ''New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid d ...

''. The writer was buried near his home on Martha's Vineyard. He was survived by his second wife, Barbara Jean Day

Barbara Jean Hersey (previously Addams, ; July 7, 1919 – August 6, 2007) was an American woman best known for having been married to two different famous people, first Charles Addams – the creator of The Addams Family – and then journalist ...

(the former wife of Hersey's colleague at ''The New Yorker'', artist Charles Addams

Charles Samuel Addams (January 7, 1912 – September 29, 1988) was an American cartoonist known for his darkly humorous and macabre characters, signing the cartoons as Chas Addams. Some of his recurring characters became known as the Addams Fa ...

), Hersey's five children, one of whom is the composer and musician Baird Hersey, and six grandchildren. Barbara Hersey died on Martha's Vineyard 14 years later on August 16, 2007.

Honors

On October 5, 2007, the United States Postal Service announced that it would honor five journalists of the 20th century with first-class rate postage stamps, to be issued on Tuesday, April 22, 2008:Martha Gellhorn

Martha Ellis Gellhorn (8 November 1908 – 15 February 1998) was an American novelist, travel writer, and journalist who is considered one of the great war correspondents of the 20th century.

Gellhorn reported on virtually every major worl ...

, John Hersey, George Polk

George Polk (October 17, 1913 – May 1948) was an American journalist for CBS who was murdered during the Greek Civil War, in 1948.

World War II

During World War II, Polk enlisted with a Naval Construction Battalion. After the invasion of Guadal ...

, Rubén Salazar

Ruben Salazar (March 3, 1928 – August 29, 1970) was a civil rights activist and a reporter for the ''Los Angeles Times,'' the first Mexican-American journalist from mainstream media to cover the Chicano community.

Salazar was killed during t ...

, and Eric Sevareid

Arnold Eric Sevareid (November 26, 1912 – July 9, 1992) was an American author and CBS news journalist from 1939 to 1977. He was one of a group of elite war correspondents who were hired by CBS newsman Edward R. Murrow and nicknamed " Murrow's&n ...

. Postmaster General

A Postmaster General, in Anglosphere countries, is the chief executive officer of the postal service of that country, a ministerial office responsible for overseeing all other postmasters. The practice of having a government official respons ...

Jack Potter

Jack Potter (born 13 April 1938 in Coburg, Victoria) is a former Australian cricketer who played 81 matches for Victoria. He also represented Australia although never in a Test.

Biography

Potter made his first-class debut in January 1957 ag ...

announced the stamp series at the Associated Press

The Associated Press (AP) is an American non-profit news agency headquartered in New York City. Founded in 1846, it operates as a cooperative, unincorporated association. It produces news reports that are distributed to its members, U.S. newspa ...

managing editors meeting in Washington, D.C.

During 1968, John Hersey High School

John Hersey High School (also referred to as Hersey or JHHS) is a four-year public high school located in Arlington Heights, Illinois, a northwest suburb of Chicago in the United States. It enrolls students from Arlington Heights as well as parts ...

in Arlington Heights, Illinois

Arlington Heights is a municipality in Cook County with a small portion in Lake County in the U.S. state of Illinois. A suburb of Chicago, it lies about northwest of the city's downtown. Per the 2020 Census, the population was 77,676. Per the ...

was named in his honor.

Soon before Hersey's death, then Acting President of Yale Howard Lamar

Howard Roberts Lamar (born November 18, 1923) is an American historian of the American West. In addition to being Sterling Professor of History Emeritus at Yale University since 1994, he served as Acting President of Yale University from 1992 to ...

decided the university should honor its long-serving alumnus. The result was the annual John Hersey Lecture, the first of which was delivered March 22, 1993, by historian and Yale graduate David McCullough

David Gaub McCullough (; July 7, 1933 – August 7, 2022) was an American popular historian. He was a two-time winner of the Pulitzer Prize and the National Book Award. In 2006, he was given the Presidential Medal of Freedom, the United States ...

, who noted Hersey's contributions to Yale but reserved his strongest praise for the former magazine writer's prose. Hersey had "portrayed our time," McCullough observed, "with a breadth and artistry matched by very few. He has given us the century in a great shelf of brilliant work, and we are all his beneficiaries."

The John Hersey Prize at Yale was endowed during 1985 by students of the author and former Pierson College master. The prize is awarded to "a senior or junior for a body of journalistic work reflecting the spirit and ideals of John Hersey: engagement with moral and social issues, responsible reportage and consciousness of craftsmanship." Winners of the John Hersey Prize include David M. Halbfinger (Yale Class of 1990) and Motoko Rich (Class of 1991), who both later had reporting careers for ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', and journalist Jacob Weisberg

Jacob Weisberg (born 1964) is an American political journalist, who served as editor-in-chief of The Slate Group, a division of Graham Holdings Company. In September 2018, he left Slate to co-found Pushkin Industries, an audio content company, w ...

(Class of 1985), who would become editor-in-chief of The Slate Group

The Slate Group, legally The Slate Group, LLC, is an American online publishing entity established in June 2008 by Graham Holdings Company. Among the publications overseen by The Slate Group are ''Slate'' and '' ForeignPolicy.com''.

The creation o ...

. Among Hersey's earlier students at Yale was Michiko Kakutani

Michiko Kakutani (born January 9, 1955) is an American writer and retired literary critic, best known for reviewing books for ''The New York Times'' from 1983 to 2017. In that role, she won the Pulitzer Prize for Criticism in 1998.

Early life ...

, formerly the chief book critic of ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', as well as film critic Gene Siskel

Eugene Kal Siskel (January 26, 1946 – February 20, 1999) was an American film critic and journalist for the ''Chicago Tribune''. Along with colleague Roger Ebert, he hosted a series of movie review programs on television from 1975 until his d ...

.

During his lifetime, Hersey served in many jobs associated with writing, journalism and education. He was the first non-academic named master of a Yale residential college. He was past president of the Authors League of America, and he was elected chancellor

Chancellor ( la, cancellarius) is a title of various official positions in the governments of many nations. The original chancellors were the of Roman courts of justice—ushers, who sat at the or lattice work screens of a basilica or law cou ...

by the membership of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

The American Academy of Arts and Letters is a 300-member honor society whose goal is to "foster, assist, and sustain excellence" in American literature, music, and art. Its fixed number membership is elected for lifetime appointments. Its headqu ...

. Hersey was an honorary fellow of Clare College

Clare College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge in Cambridge, England. The college was founded in 1326 as University Hall, making it the second-oldest surviving college of the University after Peterhouse. It was refounded ...

, Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

. He was awarded honorary degrees by Yale University

Yale University is a private research university in New Haven, Connecticut. Established in 1701 as the Collegiate School, it is the third-oldest institution of higher education in the United States and among the most prestigious in the wo ...

, the New School for Social Research

The New School for Social Research (NSSR) is a graduate-level educational institution that is one of the divisions of The New School in New York City, United States. The university was founded in 1919 as a home for progressive era thinkers. NSSR ...

, Syracuse University

Syracuse University (informally 'Cuse or SU) is a Private university, private research university in Syracuse, New York. Established in 1870 with roots in the Methodist Episcopal Church, the university has been nonsectarian since 1920. Locate ...

, Washington and Jefferson College

Washington & Jefferson College (W&J College or W&J) is a private liberal arts college in Washington, Pennsylvania. The college traces its origin to three log cabin colleges in Washington County established by three Presbyterian missionaries to ...

, Wesleyan University

Wesleyan University ( ) is a Private university, private liberal arts college, liberal arts university in Middletown, Connecticut. Founded in 1831 as a Men's colleges in the United States, men's college under the auspices of the Methodist Epis ...

, The College of William and Mary

''The'' () is a grammatical article in English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite article in English. ''The'' is the m ...

and others.

Works

Hersey's books include: * ''Men on Bataan'', 1942 * '' Into the Valley'', 1943 * ''A Bell for Adano

''A Bell for Adano'' (1945) is a film directed by Henry King and starring John Hodiak and Gene Tierney. It was adapted from the 1944 novel of the same title by John Hersey, which won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction in 1945. In his review of the ...

'', 1944

* ''Hiroshima

is the capital of Hiroshima Prefecture in Japan. , the city had an estimated population of 1,199,391. The gross domestic product (GDP) in Greater Hiroshima, Hiroshima Urban Employment Area, was US$61.3 billion as of 2010. Kazumi Matsui h ...

'', 1946

* ''The Wall'', 1950

* ''The Marmot Drive'', 1953

* ''A Single Pebble'', 1956

* ''The War Lover'', 1959

* ''The Child Buyer

''The Child Buyer'' is John Hersey's 1960 novel about a project to engineer super-intelligent persons for a project whose aim is never definitely stated. Told entirely in the form of minutes from a State Senate Standing Committee, it relates th ...

'', 1960

* ''Here to Stay'', 1963

* ''White Lotus'', 1965

* ''Too Far To Walk, 1966

* ''Under the Eye of the Storm, 1967

* '' The Algiers Motel Incident'', 1968

* ''Letter to the Alumni'', 1970

* '' The Conspiracy'', 1972

* ''My Petition for More Space'', 1974

* ''The President'', 1975Alfred A. Knopf, New York

* ''The Walnut Door'', 1977

* ''Aspects of the Presidency'', 1980

* '' The Call'', 1985

* ''Blues'', 1987

* ''Life Sketches'', 1989

* ''Fling and Other Stories'', 1990

* '' Antonietta'', 1991

* ''Key West Tales'', 1994

References

Further reading

*External links

Original "Hiroshima" article

by John Hersey in ''

The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

''

BBC article on the impact of Hersey's "Hiroshima", marking the 70th anniversary of its publication

*

John Hersey High School

*

* ttp://www.saturdayeveningpost.com/2012/02/16/archives/famous-contributors-john-hersey.html John Hersey's "A Life for a Vote"in ''

The Saturday Evening Post

''The Saturday Evening Post'' is an American magazine, currently published six times a year. It was issued weekly under this title from 1897 until 1963, then every two weeks until 1969. From the 1920s to the 1960s, it was one of the most widely c ...

''

"Hiroshima" by John Hersey

– academic research * * John Hersey Papers. Yale Collection of American Literature, Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library. {{DEFAULTSORT:Hersey, John 1914 births 1993 deaths 20th-century American novelists American anti–Vietnam War activists American essayists American expatriates in China American male journalists American magazine editors American male novelists American non-fiction writers Deaths from cancer in Florida Fellows of Clare College, Cambridge Hotchkiss School alumni Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters Pulitzer Prize for the Novel winners The New Yorker people American war correspondents of World War II Novelists from Connecticut Novelists from Florida Novelists from Massachusetts Time (magazine) people Yale University alumni Yale University faculty People from Briarcliff Manor, New York American male essayists Writers from Tianjin Children of American missionaries in China 20th-century essayists 20th-century American male writers