John H. Sides on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Admiral John Harold Sides (April 22, 1904 – April 3, 1978) was a

In 1951, Sides became head of the technical section in the office of the director of guided missiles in the Department of Defense,

In 1951, Sides became head of the technical section in the office of the director of guided missiles in the Department of Defense,

/ref> The

He died of a heart seizure on the Coronado golf course near

State Library of Victoria: Photo of Admiral John Sides (American Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Essendon Airport, Victoria)State Library of Victoria: Photo of Admiral John Sides (American Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sides, John H. United States Navy admirals United States Navy personnel of World War II United States Naval Academy alumni People from Roslyn, Washington 1904 births 1978 deaths Burials at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the Order of Naval Merit (Brazil) University of Michigan alumni

four-star admiral Military star ranking is military terminology, used to describe general and flag officers. Within NATO's armed forces, the stars are equal to OF-6–10.

Star ranking

One–star

A one–star rank is usually the lowest ranking general or flag ...

in the United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

who served as commander in chief of the United States Pacific Fleet

The United States Pacific Fleet (USPACFLT) is a theater-level component command of the United States Navy, located in the Pacific Ocean. It provides naval forces to the Indo-Pacific Command. Fleet headquarters is at Joint Base Pearl Harbor� ...

from 1960 to 1963 and was known as the father of the Navy's guided-missile

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket i ...

program.

Early career

Born inRoslyn, Washington

Roslyn is a city in Kittitas County, Washington, United States. The population was 893 at the 2010 census. Roslyn is located in the Cascade Mountains, about 80 miles east of Seattle. The town was founded in 1886 as a coal mining company town. D ...

to George Kelley Sides and Estella May Bell, he attended primary and secondary schools in Roslyn, then studied for one year at the University of Washington

The University of Washington (UW, simply Washington, or informally U-Dub) is a public research university in Seattle, Washington.

Founded in 1861, Washington is one of the oldest universities on the West Coast; it was established in Seattle a ...

before being appointed to the United States Naval Academy

The United States Naval Academy (US Naval Academy, USNA, or Navy) is a federal service academy in Annapolis, Maryland. It was established on 10 October 1845 during the tenure of George Bancroft as Secretary of the Navy. The Naval Academy ...

, from which he graduated ninth in a class of 448 in 1925.

Commissioned ensign, he served four years aboard the battleship ''Tennessee'' before being dispatched to the Asiatic Station

The Asiatic Squadron was a squadron of United States Navy warships stationed in East Asia during the latter half of the 19th century. It was created in 1868 when the East India Squadron was disbanded. Vessels of the squadron were primarily invo ...

with the destroyer ''John D. Edwards'' to participate in the Yangtze River Patrol

The Yangtze Patrol, also known as the Yangtze River Patrol Force, Yangtze River Patrol, YangPat and ComYangPat, was a prolonged naval operation from 1854–1949 to protect American interests in the Yangtze River's treaty ports. The Yangtze P ...

. He returned to the United States in June 1931 to study naval ordnance at the Naval Postgraduate School

The Naval Postgraduate School (NPS) is a public graduate school operated by the United States Navy and located in Monterey, California.

It offers master’s and doctoral degrees in more than 70 fields of study to the U.S. Armed Forces, DOD ci ...

in Annapolis, Maryland

Annapolis ( ) is the capital city of the U.S. state of Maryland and the county seat of, and only incorporated city in, Anne Arundel County. Situated on the Chesapeake Bay at the mouth of the Severn River, south of Baltimore and about east o ...

, beginning a long career in that field. He completed the ordnance course at the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

at Ann Arbor, Michigan

Ann Arbor is a city in the U.S. state of Michigan and the county seat of Washtenaw County, Michigan, Washtenaw County. The 2020 United States census, 2020 census recorded its population to be 123,851. It is the principal city of the Ann Arbor ...

in 1934, and in May began two years as assistant fire control officer aboard the light cruiser ''Cincinnati''. He served as flag lieutenant on the staff of a battleship division commander from 1936 to 1937, then spent two years in the ammunition section of the Bureau of Ordnance The Bureau of Ordnance (BuOrd) was a United States Navy organization, which was responsible for the procurement, storage, and deployment of all naval weapons, between the years 1862 and 1959.

History

Congress established the Bureau in the Departmen ...

.

In July 1939, he assumed command of the destroyer ''Tracy'', which was assigned to Mine Division 1 and operated out of Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

with the Battle Force

The United States Battle Fleet or Battle Force was part of the organization of the United States Navy from 1922 to 1941.

The General Order of 6 December 1922 organized the United States Fleet, with the Battle Fleet as the Pacific presence. This f ...

. He commanded ''Tracy'' until November 1940, then reported aboard the light cruiser ''Savannah'' as gunnery officer.

World War II

Following the United States entry intoWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, he returned to the Bureau of Ordnance in March 1942 to serve as chief of the ammunition and explosives section, where his work in research and development was instrumental in creating fuses and explosives and devising new formulae.

At the Bureau of Ordnance, Sides nurtured a number of early rocket projects, often against high-level institutional opposition. One notable success was the High Velocity Aircraft Rocket

The High Velocity Aircraft Rocket, or HVAR, also known by the nickname Holy Moses, was an American unguided rocket developed during World War II to attack targets on the ground from aircraft. It saw extensive use during both World War II and the ...

(HVAR), a 5-inch air-to-ground rocket that was used in Europe against trucks and tanks and was being produced at the rate of 40,000 per day by the end of the war. "He was a real pioneer of the Navy rocket programs," recalled Thomas F. Dixon, HVAR project officer under Sides' supervision and later chief designer of the engines for the Atlas

An atlas is a collection of maps; it is typically a bundle of maps of Earth or of a region of Earth.

Atlases have traditionally been bound into book form, but today many atlases are in multimedia formats. In addition to presenting geographic ...

, Thor

Thor (; from non, Þórr ) is a prominent god in Germanic paganism. In Norse mythology, he is a hammer-wielding æsir, god associated with lightning, thunder, storms, sacred trees and groves in Germanic paganism and mythology, sacred groves ...

, Jupiter

Jupiter is the fifth planet from the Sun and the List of Solar System objects by size, largest in the Solar System. It is a gas giant with a mass more than two and a half times that of all the other planets in the Solar System combined, but ...

, Redstone, and Saturn

Saturn is the sixth planet from the Sun and the second-largest in the Solar System, after Jupiter. It is a gas giant with an average radius of about nine and a half times that of Earth. It has only one-eighth the average density of Earth; h ...

rockets. "All the way through it was a fight with the admirals. Caltech

The California Institute of Technology (branded as Caltech or CIT)The university itself only spells its short form as "Caltech"; the institution considers other spellings such a"Cal Tech" and "CalTech" incorrect. The institute is also occasional ...

's professor of physics, Dr. Charles Lauritsen

Charles Christian Lauritsen (April 4, 1892 – April 13, 1968) was a Danish/American physicist.

Early life and career

Lauritsen was born in Holstebro, Denmark and studied architecture at the Odense Tekniske Skole, graduating in 1911. In 191 ...

, had developed a barrage rocket - ideal for landings to clean up the banks. When we brought this to the Chief of the Bureau of Ordnance, however, his general reaction was, 'Don't put rockets on my battleships, cruisers, or destroyers.'"

Sides returned to sea in October 1944 in command of Mine Division 8 for combat duty in the Pacific theater

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

, where the Navy credited him with "contributing materially to the success of the Okinawa invasion." In April 1945, he became commander of Destroyer Squadron 47, and remained in that command until the end of the war.

After the war, he was assigned as assistant chief of staff for operations and training on the staff of the commander of battleships and cruisers in the Atlantic Fleet. In September 1947 he reported for instruction at the National War College

The National War College (NWC) of the United States is a school in the National Defense University. It is housed in Roosevelt Hall on Fort Lesley J. McNair, Washington, D.C., the third-oldest Army post still active.

History

The National War Colle ...

in Washington, D.C.

Father of the guided-missile Navy

In June 1948, he began two years as deputy to the assistant chief of naval operations for guided missiles, Rear AdmiralDaniel V. Gallery

Daniel Vincent Gallery (July 10, 1901 – January 16, 1977) was a rear admiral in the United States Navy. He saw extensive action during World War II, fighting U-boats during the Battle of the Atlantic, where his most notable achievement was the ...

. Over the next decade, he would build a reputation for missile expertise and eventually become known as the father of the Navy's guided-missile program.

Revolt of the Admirals

As deputy assistant chief of naval operations for guided missiles, Sides risked his career by participating in theRevolt of the Admirals

The "Revolt of the Admirals" was a policy and funding dispute within the United States government during the Cold War in 1949, involving a number of retired and active-duty United States Navy admirals. These included serving officers Admiral Lo ...

, an episode of civil-military conflict in which high-ranking Navy officials publicly clashed with their Air Force counterparts and civilian superiors over the future of the United States military. Testifying as a guided-missile expert before the House Armed Services Committee

The U.S. House Committee on Armed Services, commonly known as the House Armed Services Committee or HASC, is a standing committee of the United States House of Representatives. It is responsible for funding and oversight of the Department of Defe ...

on October 11, 1949, Sides warned that the Air Force's B-36

The Convair B-36 "Peacemaker" is a strategic bomber that was built by Convair and operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) from 1949 to 1959. The B-36 is the largest mass-produced piston-engined aircraft ever built. It had the longest win ...

strategic bomber would not be able to penetrate Russian defenses to deliver its nuclear payload as claimed, since the United States already possessed supersonic guided missiles that would "seek out and destroy the really fast jet bombers now on the drawing boards"

and the Russians had likely inherited a similar capability from the German Wasserfall

The ''Wasserfall Ferngelenkte FlaRakete'' (Waterfall Remote-Controlled A-A Rocket) was a German guided supersonic surface-to-air missile project of World War II. Development was not completed before the end of the war and it was not used operati ...

missile development program and personnel they had captured at the end of World War II.

When Sides became eligible for early promotion to rear admiral a month later, the selection board was perceived to be stacked against captains who had participated in the Revolt because it included none of the top admirals involved in the controversy. Passed over as expected, in 1950 he took command of the heavy cruiser ''Albany'' for a twelve-month tour in the Atlantic Fleet. Sides had hoped to captain the first guided-missile cruiser, which the Navy had expected to put in operation by that year, but its development schedule had slipped due to problems with the sound barrier

The sound barrier or sonic barrier is the large increase in aerodynamic drag and other undesirable effects experienced by an aircraft or other object when it approaches the speed of sound. When aircraft first approached the speed of sound, th ...

. The first guided-missile cruiser would not become operational until 1955.

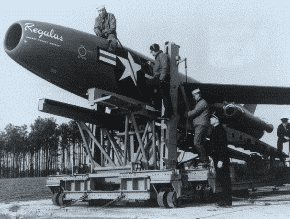

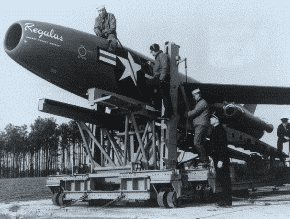

Regulus cruise missile

In 1951, Sides became head of the technical section in the office of the director of guided missiles in the Department of Defense,

In 1951, Sides became head of the technical section in the office of the director of guided missiles in the Department of Defense, K.T. Keller

Kaufman Thuma Keller, commonly known as K. T. Keller (27 November 188521 January 1966), was an American corporate executive who served as the president of Chrysler Corporation from 1935 to 1950 and as its chairman of the board from 1950 to 1956. ...

, the former president and chairman of the board of the Chrysler Corporation

Stellantis North America (officially FCA US and formerly Chrysler ()) is one of the " Big Three" automobile manufacturers in the United States, headquartered in Auburn Hills, Michigan. It is the American subsidiary of the multinational automoti ...

who had been appointed "missile czar" in October 1950 with a mandate to unify the independent service missile programs. Keller ordered the services to shift from experimentation to production on five missile projects: the Army's Nike

Nike often refers to:

* Nike (mythology), a Greek goddess who personifies victory

* Nike, Inc., a major American producer of athletic shoes, apparel, and sports equipment

Nike may also refer to:

People

* Nike (name), a surname and feminine given ...

; the Air Force's Matador

A bullfighter (or matador) is a performer in the activity of bullfighting. ''Torero'' () or ''toureiro'' (), both from Latin ''taurarius'', are the Spanish and Portuguese words for bullfighter and describe all the performers in the activit ...

; and the Navy's Terrier

Terrier (from Latin ''terra'', 'earth') is a type of dog originally bred to hunt vermin. A terrier is a dog of any one of many breeds or landraces of the terrier type, which are typically small, wiry, game, and fearless. Terrier breeds vary ...

, Sparrow, and Regulus

Regulus is the brightest object in the constellation Leo and one of the brightest stars in the night sky. It has the Bayer designation designated α Leonis, which is Latinized to Alpha Leonis, and abbreviated Alpha Leo or α Leo. Re ...

. As Keller's Navy deputy, Sides was responsible for producing all three Navy missiles, and was credited with being, "as much as any man, the father of the Regulus cruise missile." "He was the real 'thinking' admiral in the guided missile field, and an outstanding man," recalled Regulus project manager Robert F. Freitag.

Fleet ballistic missile

Sides was promoted to rear admiral in 1952 as director of the guided-missile division in the office of the chief of naval operations. In that role, he directed the Navy's entire guided-missile program for almost four years, and played an influential and initially adversarial role in the development of the Polaris fleet ballistic missile (FBM). As top missile advisor to the chief of naval operations, AdmiralRobert B. Carney

Robert Bostwick Carney (March 26, 1895 – June 25, 1990) was an admiral in the United States Navy who served as commander-in-chief of the NATO forces in Southern Europe (1951–1953) and then as Chief of Naval Operations (1953–1954) du ...

, Sides convinced Carney to veto several early FBM proposals, including a 1952 bid by Freitag and other Navy officers for a weaponized version of the Viking rocket

Viking was series of twelve sounding rockets designed and built by the Glenn L. Martin Company under the direction of the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory (NRL). Designed to supersede the German V-2, the Viking was the most advanced large, liqui ...

, whose launch from the rolling deck of a ship had already been demonstrated. Since the FBM would have to be funded internally by siphoning funds from existing Navy programs, Carney and Sides both judged that the research costs associated with the FBM were too open-ended to justify sacrificing present combat capability for an unproven future capability.

In 1954, Freitag and his colleagues at the Bureau of Aeronautics

The Bureau of Aeronautics (BuAer) was the U.S. Navy's material-support organization for naval aviation from 1921 to 1959. The bureau had "cognizance" (''i.e.'', responsibility) for the design, procurement, and support of naval aircraft and relate ...

(BuAer) again tried to engage the Navy in FBM development by funneling their research to a secret study committee chaired by Massachusetts Institute of Technology

The Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) is a private land-grant research university in Cambridge, Massachusetts. Established in 1861, MIT has played a key role in the development of modern technology and science, and is one of the ...

president James R. Killian

James Rhyne Killian Jr. (July 24, 1904 – January 29, 1988) was the 10th president of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, from 1948 until 1959.

Early life

Killian was born on July 24, 1904, in Blacksburg, South Carolina. His father ...

. The Killian Committee had a charter to unify the ballistic missile programs scattered among the services, and enthusiastically recommended that the Navy develop a fleet-based intermediate-range ballistic missile

An intermediate-range ballistic missile (IRBM) is a ballistic missile with a range of 3,000–5,500 km (1,864–3,418 miles), between a medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) and an intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM). Classifying ba ...

(IRBM). This external endorsement by a distinguished independent evaluator persuaded the chief of BuAir, Rear Admiral James S. Russell

James Sargent Russell (March 22, 1903 – April 14, 1996) was an admiral in the United States Navy.

Biography

Russell was born in Tacoma, Washington, the son of noted architect Ambrose J. Russell and Loella Janet (Sargent) Russell. He attended D ...

, to fully commit the bureau to FBM development.

However, there was no guarantee that any amount of manpower or money could create the components required for a viable FBM system, which still lacked accurate systems for guidance, fire control, and navigation; adequate metals and materials for fabrication; a compact nuclear warhead with sufficient yield; and a solid rocket propellant

Rocket propellant is the reaction mass of a rocket. This reaction mass is ejected at the highest achievable velocity from a rocket engine to produce thrust. The energy required can either come from the propellants themselves, as with a chemical ...

to replace liquid fuel

Liquid fuels are combustible or energy-generating molecules that can be harnessed to create mechanical energy, usually producing kinetic energy; they also must take the shape of their container. It is the fumes of liquid fuels that are flammable ...

s that were too dangerous to be used at sea. "There wasn't even a concept as to a launching system," recalled Admiral Arleigh A. Burke

Arleigh Albert Burke (October 19, 1901 – January 1, 1996) was an admiral of the United States Navy who distinguished himself during World War II and the Korean War, and who served as Chief of Naval Operations during the Eisenhower and Kennedy ...

, Carney's successor as chief of naval operations.

On Sides' advice, Carney again concluded that a full-fledged FBM program remained premature, and in July directed BuAer to discontinue all efforts to expand FBM development. However, Russell exercised his statutory prerogative as bureau chief

A news bureau is an office for gathering or distributing news. Similar terms are used for specialized bureaus, often to indicate a geographic location or scope of coverage: a ‘Tokyo bureau’ refers to a given news operation's office in Tokyo; ' ...

to appeal directly to James H. Smith, assistant secretary of the Navy for air, who kept the project alive until Carney was succeeded by Burke on August 17, 1955. Within 24 hours of being sworn in, Burke summoned Sides, Freitag, and other Navy missile experts to his office for a briefing on the FBM research studies. By the end of the meeting, Burke had reversed Carney's veto and committed the Navy to an all-out FBM development program, directing Sides and Freitag to work out the operational details.

Sides handled the Navy's side of negotiations over how exactly to implement the Killian Committee's recommendations, which called for the Navy to develop a ship-launched FBM similar to the Army's Jupiter IRBM

The PGM-19 Jupiter was the first nuclear armed, medium-range ballistic missile (MRBM) of the United States Air Force (USAF). It was a liquid-propellant rocket using RP-1 fuel and LOX oxidizer, with a single Rocketdyne LR79-NA (model S-3D) roc ...

. On September 13, 1955, President Dwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

accepted the Killian Committee recommendations and directed the Navy to design a sea-based support system for Jupiter. Sides and the Navy protested that liquid-fuel rockets like Jupiter were too dangerous for shipboard use and pushed instead for submarine-launched solid-fuel rockets for tactical use against enemy submarine bases. However, on November 17, 1955, Secretary of Defense

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

Charles E. Wilson ordered the Navy to join the Army on Jupiter development, and specified that all such missile development would not be externally funded but would have to be carved out of the existing Navy budget.

In response, Burke created the Special Projects Office, a new organization with a mandate to develop a submarine-launched solid-fuel fleet ballistic missile. The Special Projects Office reported directly to Burke and the secretary of the Navy

The secretary of the Navy (or SECNAV) is a statutory officer () and the head (chief executive officer) of the Department of the Navy, a military department (component organization) within the United States Department of Defense.

By law, the se ...

, an unprecedented bypass of the Navy bureaus that signalled the Navy's commitment to the FBM concept. To direct the Special Projects Office, at Sides' persistent suggestion, Burke selected Sides' former deputy, Rear Admiral William F. Raborn, Jr.

William Francis Raborn, Jr., (June 8, 1905 – March 6, 1990) was the United States Director of Central Intelligence from April 28, 1965 until June 30, 1966. He was also a career United States Navy officer who led the project to develop the ...

, whose phenomenal success in that role would earn him renown as the father of Polaris.

Guided-missile cruiser

Sides returned to sea in January 1956 as the first seagoing flag officer to command a guided-missile cruiser group, Cruiser Division 6, which included the guided-missile cruisers ''Boston'' and ''Canberra''. At the long-delayed commissioning of the Navy's first guided-missile cruiser, ''Boston'', in November 1955, Sides declared that the new ship marked a fundamental change in sea warfare because it was now possible to defend the fleet against bombers without losing several fighter planes in the process. "It is my personal opinion that within five years, the Navy will have dozens of guided missile ships. They should include not only vessels carrying antiaircraft missiles but also larger ships with surface to surface missile capability." In March 1956, the Navy displayed its first combat-ready antiaircraft missile, Terrier, aboard ''Boston''. Sides said at the time that he foresaw within five years "a family of surface-to-air guided missile ships...dozens of ships of the cruiser, frigate, destroyer and battleship classes." Sides commanded the cruiser division for only four months before being recalled to Washington in April 1956 to become deputy to the special assistant to the Secretary of Defense for guided missiles, Eger V. Murphree.Weapons Systems Evaluation Group

Sides was promoted to vice admiral in 1957 to serve as director of the Pentagon's Weapons Systems Evaluation Group (WSEG) from 1957 to 1960. As the chief weapons expert for theJoint Chiefs of Staff

The Joint Chiefs of Staff (JCS) is the body of the most senior uniformed leaders within the United States Department of Defense, that advises the president of the United States, the secretary of defense, the Homeland Security Council and the ...

, he assured the public that despite apparent setbacks in the space race with the Soviet Union, the American missile program was developing well.

On August 21, the Soviet Union successfully tested the first ICBM, a feat reported by TASS

The Russian News Agency TASS (russian: Информацио́нное аге́нтство Росси́и ТАСС, translit=Informatsionnoye agentstvo Rossii, or Information agency of Russia), abbreviated TASS (russian: ТАСС, label=none) ...

on August 27. In October, following the unexpected Russian launch of the first satellite, Sputnik 1

Sputnik 1 (; see § Etymology) was the first artificial Earth satellite. It was launched into an elliptical low Earth orbit by the Soviet Union on 4 October 1957 as part of the Soviet space program. It sent a radio signal back to Earth for t ...

, Sides spoke before the American Rocket Society

The American Rocket Society (ARS) began its existence on , under the name of the American Interplanetary Society. It was founded by science fiction writers G. Edward Pendray, David Lasser, Laurence Manning, Nathan Schachner, and others. Pendray ...

and Institute of Aeronautical Sciences

The American Institute of Aeronautics and Astronautics (AIAA) is a professional society for the field of aerospace engineering. The AIAA is the U.S. representative on the International Astronautical Federation and the International Council of t ...

and disputed the Russian report of a successful ICBM test, claiming the reported August flight might actually have been an "errant sputnik" that failed to make its orbit. He was "certain that the enormous effort which went into the development and launching of Sputnik was at the expense" of the Soviet ICBM program, and asserted that "winning the race for development of long-range weapons systems is more important than getting up the first satellite." His speech was regarded as a vigorous defense of the Eisenhower administration's decision to separate the satellite program from ballistic missile development.

After the dramatic failure of the first United States attempt to launch a satellite on December 6, 1957, Sides spoke at a conference of the American Management Association

The American Management Association (AMA) is an American non-profit educational membership organization for the promotion of management, based in New York City. Besides its headquarters there, it has local head offices throughout the world.

It o ...

on January 15, 1958, where he reiterated that the nation's development of long-range missiles was "progressing very well" and complained that a false impression had been created by missiles that failed in early tests. "It just so happened that about the time of the sputnik launchings, our intermediate and intercontinental ballistics missile flight-test programs were getting into high gear; and not being blessed with a Siberian proving ground, where we might do our testing in private, every malfunctioning test vehicle was given a play in all the media of public information. The impression was unwittingly created that we were really on our uppers, when, as a matter of fact, each one of these so-called unsuccessful missiles yielded a great deal of the very information it was fired to obtain. In ten years of missile experience I cannot recall a missile system in which similar casualties were not encountered in the early test flights. But in each case we have determined the causes, corrected the deficiencies and gone on to develop a successful weapon system."

Commander in Chief, U.S. Pacific Fleet

On June 1, 1960, PresidentDwight D. Eisenhower

Dwight David "Ike" Eisenhower (born David Dwight Eisenhower; ; October 14, 1890 – March 28, 1969) was an American military officer and statesman who served as the 34th president of the United States from 1953 to 1961. During World War II, ...

nominated Sides for promotion to admiral as commander in chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet (CINCPACFLT). Because of Sides' background, his appointment was interpreted as heralding a new emphasis on missile warfare. Sides relieved Admiral Herbert G. Hopwood on August 30. His command was responsible for guarding the Far East and the United States West Coast, and included the First Fleet

The First Fleet was a fleet of 11 ships that brought the first European and African settlers to Australia. It was made up of two Royal Navy vessels, three store ships and six convict transports. On 13 May 1787 the fleet under the command ...

, the Seventh Fleet

The Seventh Fleet is a numbered fleet of the United States Navy. It is headquartered at U.S. Fleet Activities Yokosuka, in Yokosuka, Kanagawa Prefecture, Japan. It is part of the United States Pacific Fleet. At present, it is the largest of th ...

, 400 ships, 3,000 aircraft, and half a million men.

Sides was CINCPACFLT during the early stages of American involvement in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

. In November 1961, en route to Bangkok

Bangkok, officially known in Thai language, Thai as Krung Thep Maha Nakhon and colloquially as Krung Thep, is the capital and most populous city of Thailand. The city occupies in the Chao Phraya River delta in central Thailand and has an estima ...

to repay a visit to Pearl Harbor by the commander in chief of Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

's Navy, Sides stopped overnight in Saigon

, population_density_km2 = 4,292

, population_density_metro_km2 = 697.2

, population_demonym = Saigonese

, blank_name = GRP (Nominal)

, blank_info = 2019

, blank1_name = – Total

, blank1_ ...

with his wife. Asked about rumors of Seventh Fleet units operating in Vietnamese waters, Sides replied, "The center of gravity of the Seventh Fleet is always near a troubled area," but declared there was "no intention" of using the Seventh Fleet "in the immediate future" in any role having to do with the Vietnamese crisis. "But I am not saying it could not happen."

As one of the few active four-star admirals, Sides was occasionally considered for other four-star jobs. In 1961, ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'' handicapped his odds of succeeding Burke as chief of naval operations at 15-1. He was a candidate to replace Admiral Robert L. Dennison as the NATO Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic

The Supreme Allied Commander Atlantic (SACLANT) was one of two supreme commanders of the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation (NATO), the other being the Supreme Allied Commander Europe (SACEUR). The SACLANT led Allied Command Atlantic was based at ...

in 1963, but was passed over in favor of Admiral Harold Page Smith

Admiral Harold Page Smith (February 17, 1904 – January 4, 1993) was a United States Navy four-star admiral who served as Commander in Chief, United States Naval Forces Europe/Commander in Chief, United States Naval Forces, Eastern Atlantic and M ...

.

He was relieved by Admiral U.S. Grant Sharp, Jr.

Ulysses Simpson Grant Sharp Jr. (April 2, 1906 – December 12, 2001) was a United States Navy four star admiral who served as Commander in Chief, United States Pacific Fleet (CINCPACFLT) from 1963 to 1964; and Commander-in-Chief, United States Pa ...

on September 30, 1963, and retired from the Navy on October 1.Pacific Fleet Online - U.S. Pacific Fleet CommandersPersonal life

In retirement, he became a consultant to theLockheed Aircraft Company

The Lockheed Corporation was an American aerospace manufacturer. Lockheed was founded in 1926 and later merged with Martin Marietta to form Lockheed Martin in 1995. Its founder, Allan Lockheed, had earlier founded the similarly named but ot ...

in California. President Lyndon B. Johnson

Lyndon Baines Johnson (; August 27, 1908January 22, 1973), often referred to by his initials LBJ, was an American politician who served as the 36th president of the United States from 1963 to 1969. He had previously served as the 37th vice ...

appointed him to the President's Foreign Intelligence Advisory Board

The President's Intelligence Advisory Board (PIAB) is an advisory body to the Executive Office of the President of the United States. According to its self-description, it "provides advice to the President concerning the quality and adequacy of ...

on August 10, 1965.

He married the former Virginia Eloise Roach of Inez, Kentucky

Inez ( ) is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Martin County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 546 at the 2020 census.

Geography

Inez is located at (37.866431, -82.539058). According to the United States Census Burea ...

on June 12, 1929, and they had one daughter.

His decorations include the Navy Distinguished Service Medal

The Navy Distinguished Service Medal is a military decoration of the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps which was first created in 1919 and is presented to sailors and Marines to recognize distinguished and exceptionally meritoriou ...

, Yangtze Service Medal

The Yangtze Service Medal is a decoration of the United States military which was created in 1930 for presentation to members of the United States Navy and United States Marine Corps (and to a lesser extent, members of the United States Army). Th ...

; the Legion of Merit

The Legion of Merit (LOM) is a military award of the United States Armed Forces that is given for exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services and achievements. The decoration is issued to members of the eight ...

with gold star and Combat V, awarded for his service as chief of the ammunition and explosives section of the Bureau of Ordnance during World War II; two Navy Unit commendations; the American Defense Service Medal

The American Defense Service Medal was a military award of the United States Armed Forces, established by , by President Franklin D. Roosevelt, on June 28, 1941.

The medal was intended to recognize those military service members who had served ...

; the American Campaign Medal

The American Campaign Medal is a military award of the United States Armed Forces which was first created on November 6, 1942, by issued by President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The medal was intended to recognize those military members who had perfo ...

; the Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal; the World War II Victory Medal

The World War II Victory Medal is a service medal of the United States military which was established by an Act of Congress on 6 July 1945 (Public Law 135, 79th Congress) and promulgated by Section V, War Department Bulletin 12, 1945.

The Wor ...

; and the National Defense Service Medal

The National Defense Service Medal (NDSM) is a service award of the United States Armed Forces established by President Dwight D. Eisenhower in 1953. It is awarded to every member of the US Armed Forces who has served during any one of four sp ...

. He received the rank of ''comendador'' in the Order of Naval Merit from Brazil

Brazil ( pt, Brasil; ), officially the Federative Republic of Brazil (Portuguese: ), is the largest country in both South America and Latin America. At and with over 217 million people, Brazil is the world's fifth-largest country by area ...

. He was a member of the chemical society Phi Lambda Upsilon

Phi Lambda Upsilon National Honorary Chemical Society () was founded in 1899 at the Noyes Laboratory of the University of Illinois. Phi Lambda Upsilon was the first honor society dedicated to scholarship in a single discipline, chemistry.

Object ...

, the research society Sigma Xi

Sigma Xi, The Scientific Research Honor Society () is a highly prestigious, non-profit honor society for scientists and engineers. Sigma Xi was founded at Cornell University by a junior faculty member and a small group of graduate students in 1886 ...

, and the graduate engineering society Iota Alpha. He was a Fellow of the American Rocket Society

The American Rocket Society (ARS) began its existence on , under the name of the American Interplanetary Society. It was founded by science fiction writers G. Edward Pendray, David Lasser, Laurence Manning, Nathan Schachner, and others. Pendray ...

.

He received a master of science degree from the University of Michigan

, mottoeng = "Arts, Knowledge, Truth"

, former_names = Catholepistemiad, or University of Michigania (1817–1821)

, budget = $10.3 billion (2021)

, endowment = $17 billion (2021)As o ...

at Ann Arbor in 1934.

He is the namesake of the guided-missile frigate ''Sides'', whose coat of arms contains a scaled horse's head that represents a knight on a chessboard, evoking Sides' personal reputation as a man of knightly character and integrity and as a naval officer experienced in the strategies of sea warfare.GlobalSecurity.org - FFG 14 Sides/ref> The

National Defense Industrial Association

The National Defense Industrial Association (NDIA) is a trade association for the United States government and defense industrial base. It is an 501(c)3 educational organization. Its headquarters are in Arlington, Virginia. NDIA was established ...

confers the annual Admiral John H. Sides Award on select members of its Strike, Land Attack and Air Defense Division "in recognition of meritorious service and noteworthy contribution to effective government-industry advancement in the fields of strike, land attack, and air defense warfare."NDIA - Strike, Land Attack and Air Defense (SLAAD) DivisionHe died of a heart seizure on the Coronado golf course near

San Diego, California

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the eighth most populous city in the United States ...

at the age of 73, and was buried in Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery

Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery is a federal military cemetery in the city of San Diego, California. It is located on the grounds of the former Army coastal artillery station Fort Rosecrans and is administered by the United States Department o ...

.

Decorations

References

External links

State Library of Victoria: Photo of Admiral John Sides (American Commander in Chief of the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Essendon Airport, Victoria)

{{DEFAULTSORT:Sides, John H. United States Navy admirals United States Navy personnel of World War II United States Naval Academy alumni People from Roslyn, Washington 1904 births 1978 deaths Burials at Fort Rosecrans National Cemetery Recipients of the Navy Distinguished Service Medal Recipients of the Legion of Merit Recipients of the Order of Naval Merit (Brazil) University of Michigan alumni