John Grey Gorton on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Sir John Grey Gorton (9 September 1911 – 19 May 2002) was an Australian politician who served as the nineteenth

John Grey Gorton was the second child of Alice Sinn and John Rose Gorton; his older sister Ruth was born in 1909. He had no birth certificate, but official forms recorded his date of birth as 9 September 1911 and his place of birth as

John Grey Gorton was the second child of Alice Sinn and John Rose Gorton; his older sister Ruth was born in 1909. He had no birth certificate, but official forms recorded his date of birth as 9 September 1911 and his place of birth as

Gorton spent his early years living with his maternal grandparents in

Gorton spent his early years living with his maternal grandparents in

On 31 May 1940, following the outbreak of World War II, Gorton enlisted in the

On 31 May 1940, following the outbreak of World War II, Gorton enlisted in the  Two schoolfriends, who had also been evacuated from Singapore to Batavia, heard that Gorton was in hospital, arranged for them to be put on a ship for

Two schoolfriends, who had also been evacuated from Singapore to Batavia, heard that Gorton was in hospital, arranged for them to be put on a ship for

Gorton's term in the Senate began on 22 February 1950. He was re-elected to additional terms at the

Gorton's term in the Senate began on 22 February 1950. He was re-elected to additional terms at the

Gorton was elevated to the ministry after the 1958 election, as Minister for the Navy. This was a junior position subordinate to the Minister for Defence,

Gorton was elevated to the ministry after the 1958 election, as Minister for the Navy. This was a junior position subordinate to the Minister for Defence,

After the 1963 election, Gorton relinquished the navy portfolio and was placed in charge of the government's activities in education and scientific research. He was also made Minister for Works and

After the 1963 election, Gorton relinquished the navy portfolio and was placed in charge of the government's activities in education and scientific research. He was also made Minister for Works and  Gorton presided over a "major intrusion" of the federal government into the education sector. His tenure saw significant increases in the number of university scholarships available, the number of new university entrants, and overall funding of education. One of the first major issues Gorton confronted was that of state aid to non-government schools. He believed that private schools should have equal access to federal government funding, and in 1964 announced that the government would fund science laboratories for private schools. This stance, supported by the Catholic education sector but opposed by secularists and most Protestant schools, eventually achieved widespread acceptance. In September 1965, Gorton created the Commonwealth Advisory Committee on Advanced Education, tasked with advising the government on non-university

Gorton presided over a "major intrusion" of the federal government into the education sector. His tenure saw significant increases in the number of university scholarships available, the number of new university entrants, and overall funding of education. One of the first major issues Gorton confronted was that of state aid to non-government schools. He believed that private schools should have equal access to federal government funding, and in 1964 announced that the government would fund science laboratories for private schools. This stance, supported by the Catholic education sector but opposed by secularists and most Protestant schools, eventually achieved widespread acceptance. In September 1965, Gorton created the Commonwealth Advisory Committee on Advanced Education, tasked with advising the government on non-university

In the subsequent leadership struggle, Gorton was championed by Army Minister

In the subsequent leadership struggle, Gorton was championed by Army Minister

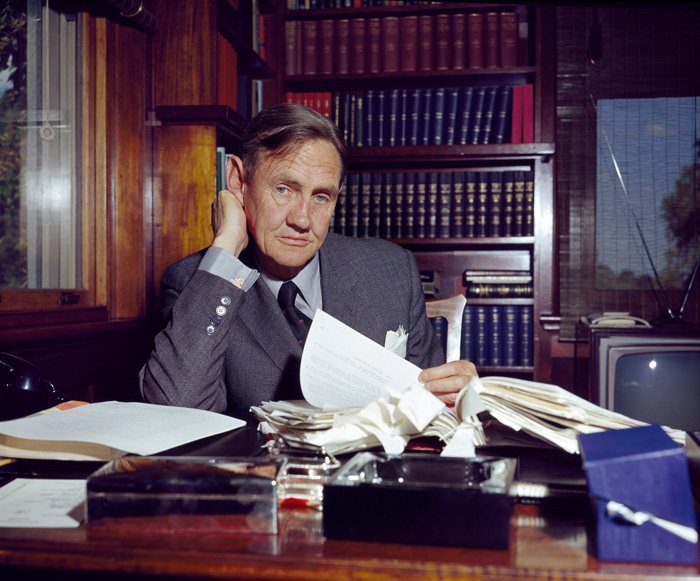

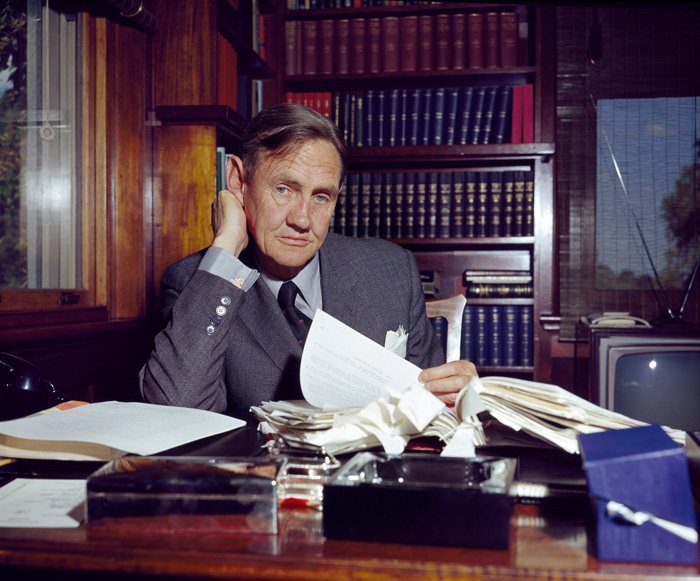

Gorton was initially a very popular Prime Minister. He carved out a style quite distinct from those of his predecessors – the aloof Menzies and the affable, sporty Holt. Gorton liked to portray himself as a man of the people who enjoyed a beer and a gamble, with a bit of a "larrikin" streak about him – hence one of his nicknames, "Gort the sport". Unfortunately for him, this reputation later came back to haunt him.

He also began to follow new policies, pursuing independent defence and foreign policies and distancing Australia from its traditional ties to Britain. But he continued to support Australia's involvement in the

Gorton was initially a very popular Prime Minister. He carved out a style quite distinct from those of his predecessors – the aloof Menzies and the affable, sporty Holt. Gorton liked to portray himself as a man of the people who enjoyed a beer and a gamble, with a bit of a "larrikin" streak about him – hence one of his nicknames, "Gort the sport". Unfortunately for him, this reputation later came back to haunt him.

He also began to follow new policies, pursuing independent defence and foreign policies and distancing Australia from its traditional ties to Britain. But he continued to support Australia's involvement in the

After the 1969 election, Gorton was unsuccessfully challenged for the Liberal leadership by McMahon and National Development Minister David Fairbairn; although on this occasion McEwen decided to lift his veto on McMahon. In the subsequent ministerial reshuffle, Gorton reinstated

After the 1969 election, Gorton was unsuccessfully challenged for the Liberal leadership by McMahon and National Development Minister David Fairbairn; although on this occasion McEwen decided to lift his veto on McMahon. In the subsequent ministerial reshuffle, Gorton reinstated

Events and issues that made the news in 1971

".

Hansard, 18 October 1973.

Gorton retired to

Gorton retired to

During a holiday in Spain while an undergraduate, Gorton met Bettina Brown of

During a holiday in Spain while an undergraduate, Gorton met Bettina Brown of

Gorton was appointed a

Gorton was appointed a

Prime Minister of Australia

The prime minister of Australia is the head of government of the Commonwealth of Australia. The prime minister heads the executive branch of the Australian Government, federal government of Australia and is also accountable to Parliament of A ...

, in office from 1968 to 1971. He led the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

during that time, having previously been a long-serving government minister.

Gorton was born out of wedlock and had a turbulent childhood. He studied at Brasenose College, Oxford

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the mi ...

, after finishing his secondary education at Geelong Grammar School

, motto_translation = 1 Corinthians 1:30: "For us, Christ was made wisdom"(1 Corinthians 1:30: Christ, who has been made for us in wisdom)

, city = Corio, Victoria

, country = Australia

, coordinates =

, ty ...

, and then returned to Australia to take over his father's property in northern Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

. Gorton enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

in 1940, and served as a fighter pilot in Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

and New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

during the Second World War. He suffered severe facial injuries in a crash landing on Bintan Island

Bintan Island or ''Negeri Segantang Lada'' is an island in the Riau archipelago of Indonesia. It is part of the Riau Islands province, the capital of which, Tanjung Pinang, lies in the island's south and is the island's main community.

Bintan's l ...

in 1942, and whilst being evacuated, his ship was torpedoed and sunk by a Japanese submarine. He returned to farming after being discharged in 1944, and was elected to the Kerang Shire Council in 1946; he later served a term as shire president. After a previous unsuccessful candidacy at state level, Gorton was elected to the Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

at the 1949 federal election. He took a keen interest in foreign policy, and gained a reputation as a strident anti-Communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

. Gorton was promoted to the ministry in 1958, and over the following decade held a variety of different portfolios in the governments of Robert Menzies

The name Robert is an ancient Germanic given name, from Proto-Germanic "fame" and "bright" (''Hrōþiberhtaz''). Compare Old Dutch ''Robrecht'' and Old High German ''Hrodebert'' (a compound of ''Hrōþ, Hruod'' ( non, Hróðr) "fame, glory ...

and Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until his presumed death in 1967. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party.

Holt was born in S ...

. He was responsible at various times for the Navy, public works, education, and science. He was elevated to the Cabinet in 1966, and the following year, he was promoted to Leader of the Government in the Senate.

Gorton defeated

Defeated may refer to:

*Defeated (Breaking Benjamin song), "Defeated" (Breaking Benjamin song)

*Defeated (Anastacia song), "Defeated" (Anastacia song)

*"Defeated", a song by Snoop Dogg from the album ''Bible of Love''

*Defeated, Tennessee, an unin ...

three other candidates for the Liberal leadership after Harold Holt's disappearance on 17 December 1967. He became the first and only senator to assume the office of Prime Minister, but soon transferred to the House of Representatives

House of Representatives is the name of legislative bodies in many countries and sub-national entitles. In many countries, the House of Representatives is the lower house of a bicameral legislature, with the corresponding upper house often c ...

in line with constitutional convention. The Gorton Government continued Australian involvement in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, but began withdrawing troops amid growing public discontent. It retained office at the 1969 federal election, albeit with a severely reduced majority. After alienating much of his government, he resigned as Liberal leader in 1971 after a confidence motion

A motion of no confidence, also variously called a vote of no confidence, no-confidence motion, motion of confidence, or vote of confidence, is a statement or vote about whether a person in a position of responsibility like in government or mana ...

in his leadership was tied, and was replaced by William McMahon

Sir William McMahon (23 February 190831 March 1988) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1971 to 1972 as leader of the Liberal Party. He was a government minister for over 21 years, t ...

. After losing the premiership, Gorton was elected deputy leader under McMahon and appointed Minister for Defence

{{unsourced, date=February 2021

A ministry of defence or defense (see spelling differences), also known as a department of defence or defense, is an often-used name for the part of a government responsible for matters of defence, found in states ...

. He was sacked for disloyalty after a few months. After the Coalition's defeat at the 1972 federal election, Gorton unsuccessfully stood as McMahon's replacement. He briefly served as an opposition frontbencher

In many parliaments and other similar assemblies, seating is typically arranged in banks or rows, with each political party or caucus grouped together. The spokespeople for each group will often sit at the front of their group, and are then kno ...

under Billy Snedden

Sir Billy Mackie Snedden, (31 December 1926 – 27 June 1987) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Liberal Party from 1972 to 1975. He was also a cabinet minister from 1964 to 1972, and Speaker of the House of Represe ...

, but stood down in 1974 and spent the rest of his career as a backbencher

In Westminster and other parliamentary systems, a backbencher is a member of parliament (MP) or a legislator who occupies no governmental office and is not a frontbench spokesperson in the Opposition, being instead simply a member of the " ...

. Gorton resigned from the Liberal Party when Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

was elected leader and he denounced the dismissal

Dismissal or dismissed may refer to:

Dismissal

*In litigation, a dismissal is the result of a successful ''motion to dismiss''. See motion

*Termination of employment, the end of employee's duration with an employer

**Dismissal (employment), ter ...

of the Whitlam Government; at the 1975 election he mounted an unsuccessful campaign for the Senate as an independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

in the ACT and advocated for a Labor win. He later spent several years as a political commentator, retiring from public life in 1981.

Gorton's domestic policies, which emphasised centralisation

Centralisation or centralization (see spelling differences) is the process by which the activities of an organisation, particularly those regarding planning and decision-making, framing strategy and policies become concentrated within a particu ...

and economic nationalism

Economic nationalism, also called economic patriotism and economic populism, is an ideology that favors state interventionism over other market mechanisms, with policies such as domestic control of the economy, labor, and capital formation, incl ...

, were often controversial in his own party, and his individualistic style alienated many of his Cabinet members. His political views widely varied and were incongruous, although he is generally regarded as having shifted further to the left over time after starting his parliamentary career on his party's hard right. Conservatively he opposed Indigenous land rights

Indigenous land rights are the rights of Indigenous peoples to land and natural resources therein, either individually or collectively, mostly in colonised countries. Land and resource-related rights are of fundamental importance to Indigenou ...

, was opposed to an Australian Republic, and at times fervently supported Australia developing nuclear weapons, but progressively, he staunchly supported drug decriminalisation, LGBT equality

Rights affecting lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) people vary greatly by country or jurisdiction—encompassing everything from the legal recognition of same-sex marriage to the death penalty for homosexuality.

Notably, , 33 ...

and reproductive rights

Reproductive rights are legal rights and freedoms relating to reproduction and reproductive health that vary amongst countries around the world. The World Health Organization defines reproductive rights as follows:

Reproductive rights rest on t ...

, having introduced the legislation nominally decriminalising homosexuality in Australia. Evaluations of his prime ministership have been mixed; although he is generally ranked higher than either Holt or McMahon, Gorton is usually considered to have been a transitional prime minister who ultimately fell short of his potential for greatness.

Early life

Birth and family background

John Grey Gorton was the second child of Alice Sinn and John Rose Gorton; his older sister Ruth was born in 1909. He had no birth certificate, but official forms recorded his date of birth as 9 September 1911 and his place of birth as

John Grey Gorton was the second child of Alice Sinn and John Rose Gorton; his older sister Ruth was born in 1909. He had no birth certificate, but official forms recorded his date of birth as 9 September 1911 and his place of birth as Wellington

Wellington ( mi, Te Whanganui-a-Tara or ) is the capital city of New Zealand. It is located at the south-western tip of the North Island, between Cook Strait and the Remutaka Range. Wellington is the second-largest city in New Zealand by me ...

, New Zealand. His birth was registered in the state of Victoria

Victoria most commonly refers to:

* Victoria (Australia), a state of the Commonwealth of Australia

* Victoria, British Columbia, provincial capital of British Columbia, Canada

* Victoria (mythology), Roman goddess of Victory

* Victoria, Seychelle ...

as occurring on that date, but in the inner Melbourne

Melbourne ( ; Boonwurrung/Woiwurrung: ''Narrm'' or ''Naarm'') is the capital and most populous city of the Australian state of Victoria, and the second-most populous city in both Australia and Oceania. Its name generally refers to a met ...

suburb of Prahran

Prahran (), also pronounced colloquially as Pran, is an inner suburb in Melbourne, Victoria (Australia), Victoria, Australia, 5 km south-east of Melbourne's Melbourne central business district, Central Business District, located within the City ...

. However, that document contained a number of inaccuracies – his name was given as "John Alga Gordon", his parents were recorded as husband and wife, his father's name was incorrect, and his sister was recorded as deceased. At some point before 1932, Gorton's father told him that he had actually been born in Wellington. There are no records of his birth in New Zealand, but his parents are known to have travelled there on several occasions.Hancock (2002), p. 2. John Gorton apparently believed he was born in Wellington, listing the city as his place of birth on his RAAF enlistment papers, and claiming so to a biographer in 1968. If he were so, it would make him the only Australian Prime Minister born in New Zealand (and the second to have been originally a New Zealander, after Chris Watson

John Christian Watson (born Johan Cristian Tanck; 9 April 186718 November 1941) was an Australian politician who served as the third prime minister of Australia, in office from 27 April to 18 August 1904. He served as the inaugural federal lead ...

).

If John Gorton was indeed born in New Zealand, this would have made him a New Zealand citizen from 1 January 1949 under changes to New Zealand nationality law

New Zealand nationality law details the conditions by which a person holds New Zealand nationality. The primary law governing nationality requirements is the Citizenship Act 1977, which came into force on 1 January 1978. Regulations apply to t ...

. Holding dual-citizenship would have rendered Gorton ineligible to sit in Australia's federal parliament under Section 44 of the Australian Constitution

Section 44 of the Australian Constitution lists the grounds for disqualification on who may become a candidate for election to the Parliament of Australia. It has generally arisen for consideration by the High Court sitting in its capacity as th ...

. Gorton's eligibility to have sat in parliament throughout his career is therefore unclear.

Gorton's father was born to a middle-class family in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, UK. As a young man he moved to Johannesburg

Johannesburg ( , , ; Zulu and xh, eGoli ), colloquially known as Jozi, Joburg, or "The City of Gold", is the largest city in South Africa, classified as a megacity, and is one of the 100 largest urban areas in the world. According to Demo ...

, South Africa, where he went into business as a merchant – during the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

, he developed a reputation as a war profiteer

A war profiteer is any person or organization that derives profit from warfare or by selling weapons and other goods to parties at war. The term typically carries strong negative connotations. General profiteering, making a profit criticized a ...

. He reputedly escaped the Siege of Ladysmith

The siege of Ladysmith was a protracted engagement in the Second Boer War, taking place between 2 November 1899 and 28 February 1900 at Ladysmith, Natal.

Background

As war with the Boer republics appeared likely in June 1899, the War Office ...

by sneaking through Boer lines, and then made his way to Australia.Hancock (2002), p. 3. He was involved in various business schemes in multiple states, and was to said to have "lived on the brink of a fortune which never quite materialised".Hancock (2002), p. 4. One of his business partners was the inventor George Julius

Sir George Alfred Julius (29 April 187328 June 1946) was an English-born Australian inventor and entrepreneur. He was the founder of Julius Poole & Gibson Pty Ltd and Automatic Totalisators Ltd, and invented the world's first automatic totalisa ...

. At some point, Gorton's father separated from his first wife, Kathleen O'Brien, and began living with Alice Sinn – born in Melbourne to a German father and an Irish mother. However, Kathleen refused to grant him a divorce. Some official documents record Gorton's parents as having married in New Zealand at some point, but there are no records of this occurring; any such marriage would have been bigamous. Gorton never denied his illegitimacy as an adult, but it did not become generally known until a biography was published during his premiership.

Childhood

Gorton spent his early years living with his maternal grandparents in

Gorton spent his early years living with his maternal grandparents in Port Melbourne

Port Melbourne is an inner-city suburb in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, south-west of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the Cities of Melbourne and Port Phillip local government areas. Port Melbourne recorded a populatio ...

, as his parents were frequently away on business trips. When he was about four years old, his parents took him to live with them in Sydney, where they had an apartment at Edgecliff. Gorton began his education at Edgecliff Preparatory School. When he was eight years old, his mother contracted tuberculosis and was sent to a sanatorium

A sanatorium (from Latin '' sānāre'' 'to heal, make healthy'), also sanitarium or sanitorium, are antiquated names for specialised hospitals, for the treatment of specific diseases, related ailments and convalescence. Sanatoriums are often ...

to avoid passing on the disease. She died in September 1920, aged 32. Gorton's grieving father sent his son to live with his estranged wife Kathleen. There, he met his sister Ruth for the first time; he had previously been told that she was dead. Although she was his full sibling, she had been raised by Kathleen since birth, and rarely saw her biological parents. Gorton initially lived with Kathleen and Ruth at their home in Cronulla

Cronulla is a suburb of Sydney, in the state of New South Wales, Australia. Boasting numerous surf beaches and swimming spots, the suburb attracts both tourists and Greater Sydney residents. Cronulla is located 26 kilometres south of the Sydney ...

. They later moved into a larger house in Killara

Killara is a suburb on the Upper North Shore of Sydney in the state of New South Wales, Australia north-west of the Sydney Central Business District in the local government area of Ku-ring-gai Council. East Killara is a separate suburb and ...

, in the north of Sydney.Hancock (2002), p. 8.

While living in Killara, Gorton began attending Headfort College, a short-lived private school run by a former Anglican minister. In 1924, he began boarding at Sydney Church of England Grammar School

, motto_translation =

, established =

, type = Independent single-sex and co-educational early learning, primary and secondary day and boarding school

, grades = Early learning ...

(Shore), initially on a weekly basis but later on a full-time one. He did not excel academically, failing the Intermediate Certificate on his first attempt, but was a well-liked boy and good at sports. Gorton began spending his holidays with his father, who had purchased a property in Mystic Park, Victoria

Mystic Park is a rural locality in the Australian state of Victoria. It straddles the Murray Valley Highway between Kerang and Swan Hill, and falls within the Shire of Gannawarra local government area. Mystic Park had a population of 181 people ...

, and planted a citrus orchard. He left Shore at the end of 1926, and the following year began boarding at Geelong Grammar School

, motto_translation = 1 Corinthians 1:30: "For us, Christ was made wisdom"(1 Corinthians 1:30: Christ, who has been made for us in wisdom)

, city = Corio, Victoria

, country = Australia

, coordinates =

, ty ...

, which he would attend for four years from 1927 to 1930. He represented the school in athletics, football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

, and rowing, and in his final year was a school prefect and house captain.

University

After leaving Geelong Grammar, Gorton spent a year working on his father's property in Mystic Park. His father then took out a second mortgage to allow him to travel to England and attendOxford University

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

. Gorton arrived in England in early 1932, and after a period at a "cramming school" passed the exam to enter Brasenose College

Brasenose College (BNC) is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It began as Brasenose Hall in the 13th century, before being founded as a college in 1509. The library and chapel were added in the m ...

. He also took flying lessons around the same time, and was awarded a pilot's licence in June 1932. Gorton began his degree in October 1932 and finished in June 1935 with an " upper second" in history, politics and economics. He was initially something of an outsider, with relatively little money and no social connections. However, his prowess in rowing – he won the O.U.B.C. Fours in his first year, and was Captain of the Brasenose College Boat Club

Brasenose College Boat Club (BNCBC) is the rowing club of Brasenose College, Oxford, in Oxford, England. It is one of the oldest boat clubs in the world, having beaten Jesus College Boat Club in the first modern rowing race, held at Oxford in ...

– saw him elected to Vincent's Club

Vincent's Club is a sports club predominantly but not exclusively for Oxford blues at Oxford University.

The club was founded in 1863 by oarsman Walter Bradford Woodgate (1841–1920) of Brasenose College, Oxford, and he was the first presid ...

and Leander Club

Leander Club, founded in 1818, is one of the oldest rowing clubs in the world, and the oldest non-academic club. It is based in Remenham in Berkshire, England and adjoins Henley-on-Thames. Only three other surviving clubs were founded prior to ...

. In 1934, while on holiday in Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

, he met his future wife Bettina Brown, the younger sister of one of his College friends. They married in early 1935.

Return to Australia

After his graduation, Gorton and his wife returned to Australia via theUnited States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, spending some time with her family in Maine

Maine () is a state in the New England and Northeastern regions of the United States. It borders New Hampshire to the west, the Gulf of Maine to the southeast, and the Canadian provinces of New Brunswick and Quebec to the northeast and north ...

. He had expected to take up a position at The Herald and Weekly Times

The Herald and Weekly Times Pty Ltd (HWT) is a newspaper publishing company based in Melbourne, Australia. It is owned and operated by News Pty Ltd, which as News Ltd, purchased the HWT in 1987.

Newspapers

The HWT's newspaper interests date ba ...

, Keith Murdoch

Sir Keith Arthur Murdoch (12 August 1885 – 4 October 1952) was an Australian journalist, businessman and the father of Rupert Murdoch, the current Executive chairman for News Corporation and the chairman of Fox Corporation.

Early life

Murdoc ...

's newspaper group. However, he arrived in Melbourne to find his father in failing health; he died in August 1936. Gorton had taken over the management of his father's orchard as soon as he entered hospital. He inherited an overdraft of £5,000, which took several years to pay off. However, the property – located on the western side of Kangaroo Lake – was in good condition, requiring only minor improvements. He employed up to ten seasonal workers during picking season. Mystic Park remained his primary residence until he was appointed to the ministry, at which point he and his family moved to Canberra.

Military service

1940–1942

On 31 May 1940, following the outbreak of World War II, Gorton enlisted in the

On 31 May 1940, following the outbreak of World War II, Gorton enlisted in the Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

Reserve. At the age of 29, Gorton was considered too old for pilot training, but he re-applied in September after this rule was relaxed. Gorton was accepted and commissioned into the RAAF on 8 November 1940. He trained as a fighter pilot at Somers, Victoria

Somers is a small town on the Mornington Peninsula in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia, south-east of Melbourne's Central Business District, located within the Shire of Mornington Peninsula local government area. Somers recorded a population of ...

and Wagga Wagga

Wagga Wagga (; informally called Wagga) is a major regional city in the Riverina region of New South Wales, Australia. Straddling the Murrumbidgee River, with an urban population of more than 56,000 as of June 2018, Wagga Wagga is the state's la ...

, New South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

, before being sent to the UK. Gorton completed his training at RAF Heston

Heston Aerodrome was an airfield located to the west of London, England, operational between 1929 and 1947. It was situated on the border of the Heston and Cranford areas of Hounslow, Middlesex. In September 1938, the British Prime Minister, Ne ...

and RAF Honiley

Royal Air Force Honiley or RAF Honiley is a former Royal Air Force station located in Wroxall, Warwickshire, southwest of Coventry, England.

The station closed in March 1958, and after being used as a motor vehicle test track, it has been sub ...

,Trengrove: 71 with No. 61 Operational Training Unit RAF

The numero sign or numero symbol, №, (also represented as Nº, No, No. or no.), is a typographic abbreviation of the word ''number''(''s'') indicating ordinal numeration, especially in names and titles. For example, using the numero sign, t ...

, flying Supermarine Spitfire

The Supermarine Spitfire is a British single-seat fighter aircraft used by the Royal Air Force and other Allied countries before, during, and after World War II. Many variants of the Spitfire were built, from the Mk 1 to the Rolls-Royce Grif ...

s.Hancock: 33 He was disappointed when his first operational posting was No. 135 Squadron RAF

No. 135 Squadron RAF was a Royal Air Force Squadron formed to be a bomber unit in the First World War and reformed as a fighter unit in Second World War.

Formation and First World War

No. 135 Squadron Royal Flying Corps was formed on 1 March 1918 ...

, a Hawker Hurricane

The Hawker Hurricane is a British single-seat fighter aircraft of the 1930s–40s which was designed and predominantly built by Hawker Aircraft Ltd. for service with the Royal Air Force (RAF). It was overshadowed in the public consciousness by ...

unit, as he considered the type greatly inferior to Spitfires.

During late 1941, Gorton and other members of his squadron became part of the cadre

Cadre may refer to:

*Cadre (military), a group of officers or NCOs around whom a unit is formed, or a training staff

*Cadre (politics), a politically controlled appointment to an institution in order to circumvent the state and bring control to th ...

of a Hurricane wing

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expres ...

being formed for service in the Middle East. They were sent by sea, with 50 Hurricanes in crates, travelling around Africa to reduce the risk of attack. In December, when the ship was at Durban

Durban ( ) ( zu, eThekwini, from meaning 'the port' also called zu, eZibubulungwini for the mountain range that terminates in the area), nicknamed ''Durbs'',Ishani ChettyCity nicknames in SA and across the worldArticle on ''news24.com'' from ...

, South Africa, it was diverted to Singapore, after Japan entered the war. As it approached its destination in mid-January, Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

forces were advancing down the Malayan Peninsula. The ship was attacked on at least one occasion by Japanese aircraft, but arrived and unloaded safely after tropical storms made enemy air raids impossible. As the Hurricanes were assembled, the pilots were formed into a composite operational squadron, No. 232 Squadron RAF

No. 232 Squadron of the Royal Air Force was active in both World War I and World War II in a variety of roles, having seen action as an anti-submarine patrol, fighter and transport squadron.

History In World War I

The squadron was formed on 20 A ...

.

In late January 1942, the squadron became operational and joined the remnants of several others that had been in Malaya, operating out of RAF Seletar

Seletar Airport is a civilian international airport serving the north-east region of Singapore. It is located approximately northwest from Changi Airport, the country's main airport, and about north from the main commercial city-centre.

...

and RAF Kallang

Kallang is a planning area and residential town located in the Central Region of Singapore.

Development of the town is centered around the Kallang River, the longest river in Singapore. Kallang Planning Area is bounded by Toa Payoh in the no ...

. During one of his first sortie

A sortie (from the French word meaning ''exit'' or from Latin root ''surgere'' meaning to "rise up") is a deployment or dispatch of one military unit, be it an aircraft, ship, or troops, from a strongpoint. The term originated in siege warfare. ...

s, Gorton was involved in a brief dogfight over the South China Sea

The South China Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean. It is bounded in the north by the shores of South China (hence the name), in the west by the Indochinese Peninsula, in the east by the islands of Taiwan and northwestern Phil ...

, after which he suffered engine failure and was forced to land on Bintan

Bintan Regency (formerly Riau Islands Regency; id, Kabupaten Kepulauan Riau) is an administrative area in the Riau Islands Province of Indonesia. Bintan Regency includes all of Bintan Island (except for the city of Tanjung Pinang which is sepa ...

island, 40 km (25 mi) south east of Singapore. As he landed, one of the Hurricane's wheels hit an embankment and flipped over. Gorton was not properly strapped in and his face hit the gun sight and windscreen, mutilating his nose and breaking both cheekbones.Trengrove: 76 He also suffered severe lacerations to both arms. He made his way out of the wreck and was rescued by members of the Royal Dutch East Indies Army

The Royal Netherlands East Indies Army ( nl, Koninklijk Nederlands Indisch Leger; KNIL, ) was the military force maintained by the Kingdom of the Netherlands in its colony of the Dutch East Indies, in areas that are now part of Indonesia. The ...

, who provided some medical treatment. Gorton later claimed that his face was so badly cut and bruised, that a member of the RAF sent to collect him assumed he was near death, collected his personal effects and returned to Singapore without him. By chance, one week later, Sgt Matt O'Mara of No. 453 Squadron RAAF

No. 453 Squadron is an air traffic control unit of the Royal Australian Air Force. It was established at Bankstown, New South Wales, in 1941 as a fighter squadron, in accordance with Article XV of the Empire Air Training Scheme for overseas se ...

also crash landed on Bintan, and arranged for them to be collected.Trengrove: 77

They arrived back in Singapore, on 11 February, three days after the island had been invaded. As the Allied air force units on Singapore had been destroyed or evacuated by this stage, Gorton was put on the ''Derrymore'', an ammunition ship bound for Batavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

(Jakarta). On 13 February, as it neared its destination, the ship was torpedoed by Japanese submarine I-55 Kaidai class submarine

The was a type of first-class submarine operated by the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN) before and during World War II. The type name was shortened to Navy Large Type Submarine.

All ''Kaidai''-class submarines originally had a two-digit boat nam ...

and the ''Derrymore'' was abandoned. Gorton then spent almost a day on a crowded liferaft, in shark-infested waters, with little drinking water, until the raft was spotted by HMAS ''Ballarat'', which picked up the passengers and took them to Batavia.

Fremantle

Fremantle () () is a port city in Western Australia, located at the mouth of the Swan River in the metropolitan area of Perth, the state capital. Fremantle Harbour serves as the port of Perth. The Western Australian vernacular diminutive for ...

, which left on 23 February and treated Gorton's wounds. When the ship arrived in Fremantle, on 3 March, one of Gorton's arm wounds had become septic and needed extensive treatment. However, he was more concerned about the effect that the sight of his mutilated face would have on his wife. It is reported that Betty Gorton, who had been running the farm in his absence, was relieved to see Gorton alive.

1942–1944

After arriving in Australia he was posted to Darwin on 12 August 1942 withNo. 77 Squadron RAAF

No. 77 Squadron is a Royal Australian Air Force (RAAF) squadron headquartered at RAAF Base Williamtown, New South Wales. It is controlled by No. 81 Wing, and equipped with Lockheed Martin F-35 Lightning II multi-role fighters. The squad ...

(Kittyhawks). During this time he was involved in his second air accident. While flying P-40E A29-60 on 7 September 1942, he was forced to land due to an incorrectly set fuel cock. Both Gorton and his aircraft were recovered several days later after spending time in the bush. On 21 February 1943 the squadron was relocated to Milne Bay

Milne Bay is a large bay in Milne Bay Province, south-eastern Papua New Guinea. More than long and over wide, Milne Bay is a sheltered deep-water harbor accessible via Ward Hunt Strait. It is surrounded by the heavily wooded Stirling Range to t ...

, New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

.

Gorton's final air incident came on 18 March 1943. His A29-192 Kittyhawk's engine failed on takeoff, causing the aircraft to flip at the end of the strip. Gorton was unhurt. In March 1944, Gorton was sent back to Australia with the rank of Flight Lieutenant. His final posting was as a Flying Instructor with No. 2 Operational Training Unit at Mildura

Mildura is a regional city in north-west Victoria, Australia. Located on the Victorian side of the Murray River, Mildura had a population of 34,565 in 2021. When nearby Wentworth, Irymple, Nichols Point and Merbein are included, the area had ...

, Victoria. He was then discharged from the RAAF on 5 December 1944.

During late 1944 Gorton went to Heidelberg Hospital for surgery which could not fully repair his facial injuries; he was left permanently disfigured.

Early political involvement

After resuming his life in Mystic Park, Gorton was elected unopposed to the Kerang Shire Council in September 1946. He remained on the council until 1952, overlapping with his first term in the Senate, and from 1949 to 1950 served as shire president.Hancock (2002), p. 46. Although he had little previous experience, Gorton began to develop a reputation as a powerful public speaker. His first major speech, in April 1946, was an address to a welcome-home gathering for returned soldiers at the Mystic Park Hall. In what John Brogden has described as "Australia's best unknown political speech", he exhorted his audience to honour those who had died in the war by building "a world in which meanness and poverty, tyranny and hate, have no existence". Gorton's next major speech was made in September 1947, at a rally against the Chifley Government's attempt to nationalise private banks. He told the crowd inKerang

Kerang is a rural town on the Loddon River in northern Victoria in Australia. It is the commercial centre to an irrigation district based on livestock, horticulture, lucerne and grain. It is located north-west of Melbourne on the Murray V ...

that they should oppose the establishment of banks run by politicians, and objected in particular to the government's decision not to take the issue to a referendum. According to his biographer Ian Hancock, "the bank nationalisation issue marked his advance beyond purely local politics and stamped him firmly and publicly as an anti-socialist".

Gorton had been a supporter of the Country Party before the war, along with most of his neighbours. Over time, he became frustrated with the party's frequent squabbles with the Liberal Party

The Liberal Party is any of many political parties around the world. The meaning of ''liberal'' varies around the world, ranging from liberal conservatism on the right to social liberalism on the left.

__TOC__ Active liberal parties

This is a li ...

and its willingness to cooperate with the Labor Party. After the Victorian Country Party withdrew from its coalition with the Liberals in December 1948, Gorton became involved in efforts to form a new anti-socialist movement that would absorb both parties. At some point he was introduced to Magnus Cormack

Sir Magnus Cameron Cormack KBE (12 February 1906 – 26 November 1994) was an Australian politician. He was a member of the Liberal Party and served multiple terms as a Senator for Victoria (1951–1953, 1962–1978), including as President of ...

, the state president of the Liberals, who became something of a mentor.Hancock (2002), pp. 53–54. In March 1949, Gorton was elected to the state executive of the new organisation, which named itself the Liberal and Country Party

The Liberal Party of Australia (Victorian Division), branded as Liberal Victoria, and commonly known as the Victorian Liberals, is the state division of the Liberal Party of Australia in Victoria (Australia), Victoria. It was formed in 1949 as ...

(LCP).Hancock (2002), p. 55. On a number of occasions he addressed Country Party gatherings, urging its members to join the new party and stressing that it would not neglect rural interests, as many feared. However, the LCP did not achieve its goal of uniting the anti-Labor forces, as most Country Party members viewed it as simply a takeover attempt; the new party affiliated with the federal Liberal Party of Australia

The Liberal Party of Australia is a centre-right political party in Australia, one of the two major parties in Australian politics, along with the centre-left Australian Labor Party. It was founded in 1944 as the successor to the United Au ...

.

In June 1949, Gorton stood for the Victorian Legislative Council

The Victorian Legislative Council (VLC) is the upper house of the bicameral Parliament of Victoria, Australia, the lower house being the Legislative Assembly. Both houses sit at Parliament House in Spring Street, Melbourne. The Legislative Co ...

as the LCP candidate in Northern Province. It was a safe Country Party seat, and at the preceding three elections no other parties had bothered to field a candidate. Making right-wing unity the focal point of his campaign, Gorton polled 48.8 percent of the vote to finish less than 400 votes behind the sitting member, George Tuckett. The result impressed the LCP's leadership, and the following month he was preselected in third place on its joint Senate

A senate is a deliberative assembly, often the upper house or chamber of a bicameral legislature. The name comes from the ancient Roman Senate (Latin: ''Senatus''), so-called as an assembly of the senior (Latin: ''senex'' meaning "the el ...

ticket with the Country Party. He was relatively unknown within the party, and his rural background was a major factor in his selection. The Coalition won a large majority at the 1949 federal election, including four out of Victoria's seven senators. The LCP candidates joined the parliamentary Liberal Party.

Senate (1950–1968)

Backbencher

1951

Events

January

* January 4 – Korean War: Third Battle of Seoul – Chinese and North Korean forces capture Seoul for the second time (having lost the Second Battle of Seoul in September 1950).

* January 9 – The Government of the United ...

, 1953

Events

January

* January 6 – The Asian Socialist Conference opens in Rangoon, Burma.

* January 12 – Estonian émigrés found a Estonian government-in-exile, government-in-exile in Oslo.

* January 14

** Marshal Josip Broz Tito i ...

, 1958

Events

January

* January 1 – The European Economic Community (EEC) comes into being.

* January 3 – The West Indies Federation is formed.

* January 4

** Edmund Hillary's Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition completes the third ...

, and 1964 elections, and from 1953 occupied first place on the Coalition's ticket in Victoria. Gorton's early speeches on domestic policy foreshadowed the stances and policy initiatives he would later adopt as prime minister, such as economic nationalism, support for a strong central government, and support for nuclear energy. One of his first notable actions in the Senate came in November 1951, when he successfully moved a motion opposing "any substantial measure of ownership or control over any Australian broadcasting station" being granted to non-Australians. In his early speeches on foreign policy, Gorton drew analogies between the actions of the Soviet Union and Communist China and those of Nazi Germany. He developed a reputation as a "hardline anti-communist

Anti-communism is Political movement, political and Ideology, ideological opposition to communism. Organized anti-communism developed after the 1917 October Revolution in the Russian Empire, and it reached global dimensions during the Cold War, w ...

", speaking in favour of the Communist Party Dissolution Bill and campaigning for the "Yes" vote during the 1951 referendum to ban the Communist Party

A communist party is a political party that seeks to realize the socio-economic goals of communism. The term ''communist party'' was popularized by the title of ''The Manifesto of the Communist Party'' (1848) by Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels. A ...

. At a campaign rally in September 1951, he had to be restrained by police after attempting to drag a heckler from his seat and shouting at him to "come outside, you yellow rat".

From 1952 to 1958, Gorton served on the Joint Parliamentary Committee on Foreign Affairs, including as chairman for a period. He developed a keen interest in Asia, which was rooted in his anti-communism, and joined parliamentary delegations to Malaya, South Vietnam, Thailand

Thailand ( ), historically known as Siam () and officially the Kingdom of Thailand, is a country in Southeast Asia, located at the centre of the Indochinese Peninsula, spanning , with a population of almost 70 million. The country is bo ...

, and the Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

. He strongly supported Australia joining the Southeast Asia Treaty Organisation

The Southeast Asia Treaty Organization (SEATO) was an international organization for collective security, collective defense in Southeast Asia created by the Southeast Asia Collective Defense Treaty, or Manila Pact, signed in September 1954 i ...

(SEATO), a collective defence initiative designed to prevent the spread of communism in the region. He also supported Taiwanese independence

The Taiwan independence movement is a political movement which advocates the formal declaration of an independent and sovereign Taiwanese state, as opposed to Chinese unification or the status quo in Cross-Strait relations.

Currently, Tai ...

and opposed Australian recognition of the People's Republic of China (PRC). On a number of occasions, Gorton spoke of the need for Australia to develop a foreign policy independent of Britain and the United States. In May 1957, he told the Senate that Australia should acquire its own nuclear deterrent, including intercontinental missiles.

Government minister

Navy

Gorton was elevated to the ministry after the 1958 election, as Minister for the Navy. This was a junior position subordinate to the Minister for Defence,

Gorton was elevated to the ministry after the 1958 election, as Minister for the Navy. This was a junior position subordinate to the Minister for Defence, Athol Townley

Athol Gordon Townley (3 October 190524 December 1963) was an Australian politician who served in the House of Representatives from 1949 until his death in 1963. A member of the Liberal Party, he served as a minister in the Menzies Government fr ...

. Although his promotion was unexpected, he would serve as Minister for the Navy for more than five years, the longest-serving navy minister in Australia's history. Gorton regularly attended meetings of the Naval Board, unlike previous ministers, and championed its recommendations at cabinet meetings. He was able to secure most elements of the board's desired modernisation program, despite Townley showing more interest in the air force. During Gorton's tenure, the navy acquired four Australian-built frigates and six British-built minesweepers, as well as placing orders for three ''Charles F. Adams''-class destroyers and four ''Oberon''-class submarines. He postponed the phasing out of the Fleet Air Arm

The Fleet Air Arm (FAA) is one of the five fighting arms of the Royal Navy and is responsible for the delivery of naval air power both from land and at sea. The Fleet Air Arm operates the F-35 Lightning II for maritime strike, the AW159 Wil ...

, due to occur in 1963, and secured the purchase of 27 Westland Wessex

The Westland Wessex is a British-built turbine-powered development of the Sikorsky H-34 (in US service known as Choctaw). It was developed and produced under licence by Westland Aircraft (later Westland Helicopters). One of the main changes ...

helicopters.

Gorton was a supporter and admirer of Robert Menzies, who was sympathetic to his ambitions for higher office and assigned him additional responsibilities. In 1959, he was tasked with securing the passage of the Matrimonial Causes Bill, which introduced uniform divorce laws; he described it as "a systematic attempt to make a new approach to the problem of divorce". The bill was opposed by religious conservatives (mostly Catholics) on both sides of politics, but it eventually passed the Senate with only a single amendment. Gorton was appointed assistant minister to the Minister for External Affairs In many countries, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is the government department responsible for the state's diplomacy, bilateral, and multilateral relations affairs as well as for providing support for a country's citizens who are abroad. The entit ...

in February 1960, working under Menzies and later under Garfield Barwick

Sir Garfield Edward John Barwick, (22 June 190313 July 1997) was an Australian judge who was the seventh and longest serving Chief Justice of Australia, in office from 1964 to 1981. He had earlier been a Liberal Party politician, serving as a ...

and Paul Hasluck

Sir Paul Meernaa Caedwalla Hasluck, (1 April 1905 – 9 January 1993) was an Australian statesman who served as the 17th Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1969 to 1974. Prior to that, he was a Liberal Party politician, holding min ...

. In February 1962, he was also made minister-in-charge of the CSIRO

The Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation (CSIRO) is an Australian Government

The Australian Government, also known as the Commonwealth Government, is the national government of Australia, a federal parliamentar ...

. During question time

A question time in a parliament occurs when members of the parliament ask questions of government ministers (including the prime minister), which they are obliged to answer. It usually occurs daily while parliament is sitting, though it can be ca ...

in the Senate, he represented ministers from the House of Representatives, allowing him to gain experience in portfolios beyond his own.

Education and science

After the 1963 election, Gorton relinquished the navy portfolio and was placed in charge of the government's activities in education and scientific research. He was also made Minister for Works and

After the 1963 election, Gorton relinquished the navy portfolio and was placed in charge of the government's activities in education and scientific research. He was also made Minister for Works and Minister for the Interior

Minister may refer to:

* Minister (Christianity), a Christian cleric

** Minister (Catholic Church)

* Minister (government), a member of government who heads a ministry (government department)

** Minister without portfolio, a member of governme ...

, relatively low-profile positions dealing mostly with administrative matters; the latter post was taken over by Doug Anthony

John Douglas Anthony, (31 December 192920 December 2020) was an Australian politician. He served as leader of the National Party of Australia from 1971 to 1984 and was the second and longest-serving Deputy Prime Minister, holding the position ...

after a few months. Menzies had a personal interest in education, having previously handled the portfolio himself, and told Gorton that it should be his primary focus. He was given oversight of the Australian Universities Commission, the Australian National University

The Australian National University (ANU) is a public research university located in Canberra, the capital of Australia. Its main campus in Acton encompasses seven teaching and research colleges, in addition to several national academies and ...

, the Commonwealth Archives Office, the Commonwealth Literary Fund

The Commonwealth Literary Fund (CLF) was an Australian Government initiative founded in 1908 to assist needy Australian writers and their families. It was Federal Australia's first systematic support for the arts. Its scope was later broadened to e ...

, and the National Library of Australia

The National Library of Australia (NLA), formerly the Commonwealth National Library and Commonwealth Parliament Library, is the largest reference library in Australia, responsible under the terms of the ''National Library Act 1960'' for "mainta ...

. In January 1966, Menzies retired and Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until his presumed death in 1967. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party.

Holt was born in S ...

became prime minister. Gorton was elevated to cabinet

Cabinet or The Cabinet may refer to:

Furniture

* Cabinetry, a box-shaped piece of furniture with doors and/or drawers

* Display cabinet, a piece of furniture with one or more transparent glass sheets or transparent polycarbonate sheets

* Filing ...

, and at the end of the year was given the title Minister for Education and Science. He was placed in charge of the new Department of Education and Science

An education ministry is a national or subnational government agency politically responsible for education. Various other names are commonly used to identify such agencies, such as Ministry of Education, Department of Education, and Ministry of Pub ...

, the first time those portfolios had been given a separate department at federal level.

Gorton presided over a "major intrusion" of the federal government into the education sector. His tenure saw significant increases in the number of university scholarships available, the number of new university entrants, and overall funding of education. One of the first major issues Gorton confronted was that of state aid to non-government schools. He believed that private schools should have equal access to federal government funding, and in 1964 announced that the government would fund science laboratories for private schools. This stance, supported by the Catholic education sector but opposed by secularists and most Protestant schools, eventually achieved widespread acceptance. In September 1965, Gorton created the Commonwealth Advisory Committee on Advanced Education, tasked with advising the government on non-university

Gorton presided over a "major intrusion" of the federal government into the education sector. His tenure saw significant increases in the number of university scholarships available, the number of new university entrants, and overall funding of education. One of the first major issues Gorton confronted was that of state aid to non-government schools. He believed that private schools should have equal access to federal government funding, and in 1964 announced that the government would fund science laboratories for private schools. This stance, supported by the Catholic education sector but opposed by secularists and most Protestant schools, eventually achieved widespread acceptance. In September 1965, Gorton created the Commonwealth Advisory Committee on Advanced Education, tasked with advising the government on non-university technical and further education

Technical and further education or simply TAFE (), is the common name in English-speaking countries in Oceania for vocational education, as a subset of tertiary education. TAFE institutions provide a wide range of predominantly vocational cours ...

(TAFE). He announced that the federal government would fund technical colleges on a pro-rata basis with the states, and personally oversaw the establishment of the Canberra College of Advanced Education, the forerunner of the University of Canberra

The University of Canberra (UC) is a public research university with its main campus located in Bruce, Canberra, Australian Capital Territory. The campus is within walking distance of Westfield Belconnen, and from Canberra's Civic Centre. UC ...

. As science minister, he lent his support to the Anglo-Australian Telescope

The Anglo-Australian Telescope (AAT) is a 3.9-metre equatorially mounted telescope operated by the Australian Astronomical Observatory and situated at the Siding Spring Observatory, Australia, at an altitude of a little over 1,100 m. In 20 ...

project, securing cabinet approval for its construction in April 1967.

Role in the VIP aircraft affair

Gorton's reputation was significantly enhanced by his role in the VIP aircraft affair, a political controversy relating to the use ofRoyal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

(RAAF) VIP aircraft by the Holt Government and its predecessor the Menzies Government

Menzies is a Scottish surname, with Gaelic forms being Méinnearach and Méinn, and other variant forms being Menigees, Mennes, Mengzes, Menzeys, Mengies, and Minges.

Derivation and history

The name and its Gaelic form are probably derived f ...

that came to a head in October 1967. Holt had provided vague and inaccurate answers to parliamentary questions

A question time in a parliament occurs when members of the parliament ask questions of government ministers (including the prime minister), which they are obliged to answer. It usually occurs daily while parliament is sitting, though it can be ca ...

about the VIP fleet, notably denying the existence of passenger manifests which might confirm instances of misuse. Air Minister Peter Howson

Peter Howson OBE (born 27 March 1958) is a Scottish painter. He was a British official war artist in 1993 during the Bosnian War.

Early life

Peter Howson was born in London of Scottish parents and moved with his family to Prestwick, A ...

became aware of the inaccuracies and sought to protect Holt, but their statements were soon subjected to further scrutiny, leading to accusations that they had conspired to mislead parliament. Gorton, who had just replaced Denham Henty

Sir Norman Henry Denham Henty, KBE (13 October 1903 – 9 May 1978) was an Australian politician. He was a member of the Liberal Party and served as a Senator for Tasmania from 1950 to 1968. He held ministerial office as Minister for Custo ...

as Leader of the Government in the Senate on 16 October, helped resolve the situation by tabling

In computing, memoization or memoisation is an optimization technique used primarily to speed up computer programs by storing the results of expensive function calls and returning the cached result when the same inputs occur again. Memoization ...

the "missing" passenger manifests in their entirety on 25 October. He did so on the grounds that the government could not maintain such a cover-up.

Gorton's act has been credited for helping thrust him into general public view; boosting his standing among his parliamentary colleagues; and for the first time Gorton began to be viewed as a serious future leadership contender, which proved to be critical to his election as Holt's successor three months later. However, although Gorton defended Howson in Parliament, the affair also sewed the seeds of long-term enmity between him and Howson, the latter turning into a staunch, vocal opponent of Gorton during his years as Prime Minister and beyond.

Prime Minister

First term

Holt's disappearance

Harold Holt

Harold Edward Holt (5 August 190817 December 1967) was an Australian politician who served as the 17th prime minister of Australia from 1966 until his presumed death in 1967. He held office as leader of the Liberal Party.

Holt was born in S ...

disappeared while swimming on 17 December 1967 and was declared presumed drowned two days later. His presumed successor was Liberal deputy leader William McMahon

Sir William McMahon (23 February 190831 March 1988) was an Australian politician who served as the 20th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1971 to 1972 as leader of the Liberal Party. He was a government minister for over 21 years, t ...

. However, on 18 December, the Country Party leader and Deputy Prime Minister John McEwen

Sir John McEwen, (29 March 1900 – 20 November 1980) was an Australian politician who served as the 18th prime minister of Australia, holding office from 1967 to 1968 in a caretaker capacity after the disappearance of Harold Holt. He was the ...

announced that if McMahon were named the new Liberal leader, he and his party would not serve under him. His reasons were never stated publicly, but in a private meeting with McMahon, he said "I will not serve under you because I do not trust you". McEwen's shock declaration triggered a leadership crisis within the Liberal Party; even more significantly, it raised the threat of a possible breaking of the Coalition, which would spell electoral disaster for the Liberals. Up to that time, the Liberals had never won enough seats in any House of Representatives election to be able to govern without Country Party support. Indeed, since the Coalition's formation in 1923, the major non-Labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

party had only been able to govern alone once, during Joseph Lyons

Joseph Aloysius Lyons (15 September 1879 – 7 April 1939) was an Australian politician who served as the List of prime ministers of Australia by time in office, 10th Prime Minister of Australia, in office from 1932 until his death in 1939. He ...

' first ministry. Even then, Lyons' United Australia Party

The United Australia Party (UAP) was an Australian political party that was founded in 1931 and dissolved in 1945. The party won four federal elections in that time, usually governing in coalition with the Country Party. It provided two prim ...

had come up four seats short of a majority in its own right, and was only able to garner a bare majority of two when the five members of the Emergency Committee of South Australia

The Emergency Committee of South Australia was the major anti-Labor grouping in South Australia at the 1931 federal election.

History

The Emergency Committee arose as a consequence of the financial turmoil brought about by the Great Depression in ...

joined the UAP party room.

The Governor-General Lord Casey

Richard Gavin Gardiner Casey, Baron Casey, (29 August 1890 – 17 June 1976) was an Australian statesman who served as the 16th Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1965 to 1969. He was also a distinguished army officer, long-serving ...

swore McEwen in as Prime Minister, on an interim basis pending the Liberal Party electing its new leader. McEwen agreed to accept an interim appointment provided there was no formal statement of time limit. This appointment was in keeping with previous occasions when a conservative Coalition government had been deprived of its leader. Casey also concurred in the view put to him by McEwen that to commission a Liberal temporarily as Prime Minister would give that person an unfair advantage in the forthcoming party room ballot for the permanent leader.

In the subsequent leadership struggle, Gorton was championed by Army Minister

In the subsequent leadership struggle, Gorton was championed by Army Minister Malcolm Fraser

John Malcolm Fraser (; 21 May 1930 – 20 March 2015) was an Australian politician who served as the 22nd prime minister of Australia from 1975 to 1983, holding office as the leader of the Liberal Party of Australia.

Fraser was raised on hi ...

, Government Whip in the Senate Malcolm Scott and Liberal Party Whip Dudley Erwin

George Dudley Erwin (20 August 191729 October 1984) was an Australian politician who served in the House of Representatives from 1955 to 1975, representing the Liberal Party. He was Chief Government Whip from 1967 to 1969, and played a role in t ...

, and with their support he was able to defeat rivals Paul Hasluck

Sir Paul Meernaa Caedwalla Hasluck, (1 April 1905 – 9 January 1993) was an Australian statesman who served as the 17th Governor-General of Australia, in office from 1969 to 1974. Prior to that, he was a Liberal Party politician, holding min ...

, Les Bury

Leslie Harry Ernest Bury CMG (25 February 1913 – 7 September 1986) was an Australian politician and economist. He was a member of the Liberal Party and served in the House of Representatives between 1956 and 1974, representing the Division of ...

and Billy Snedden

Sir Billy Mackie Snedden, (31 December 1926 – 27 June 1987) was an Australian politician who served as the leader of the Liberal Party from 1972 to 1975. He was also a cabinet minister from 1964 to 1972, and Speaker of the House of Represe ...

to become Liberal leader even though he was a member of the Senate. He was elected party leader on 9 January 1968, and appointed Prime Minister on 10 January, replacing McEwen. He was the only Senator in Australia's history to be Prime Minister and the only Prime Minister to have ever served in the Senate. He remained a Senator until, in accordance with the Westminster

Westminster is an area of Central London, part of the wider City of Westminster.

The area, which extends from the River Thames to Oxford Street, has many visitor attractions and historic landmarks, including the Palace of Westminster, Bu ...

tradition that the Prime Minister is a member of the lower house of parliament, he resigned on 1 February 1968 to contest the by-election for Holt's old House of Representatives seat of Higgins in south Melbourne. The by-election in this comfortably safe Liberal seat was held on 24 February; there were three other candidates, but Gorton achieved a massive 68% of the formal vote. He visited all the polling places during the day, but was unable to vote for himself as he was still enrolled in Mallee, in rural western Victoria. Between 2 and 23 February (both dates inclusive) he was a member of neither house of parliament.

Although he was still a Senator when he was sworn in as Prime Minister, Gorton never sat in the Senate as Prime Minister because neither House of Parliament was in session between his swearing in as Prime Minister and his resignation from the Senate.

Activities in office

Gorton was initially a very popular Prime Minister. He carved out a style quite distinct from those of his predecessors – the aloof Menzies and the affable, sporty Holt. Gorton liked to portray himself as a man of the people who enjoyed a beer and a gamble, with a bit of a "larrikin" streak about him – hence one of his nicknames, "Gort the sport". Unfortunately for him, this reputation later came back to haunt him.

He also began to follow new policies, pursuing independent defence and foreign policies and distancing Australia from its traditional ties to Britain. But he continued to support Australia's involvement in the

Gorton was initially a very popular Prime Minister. He carved out a style quite distinct from those of his predecessors – the aloof Menzies and the affable, sporty Holt. Gorton liked to portray himself as a man of the people who enjoyed a beer and a gamble, with a bit of a "larrikin" streak about him – hence one of his nicknames, "Gort the sport". Unfortunately for him, this reputation later came back to haunt him.

He also began to follow new policies, pursuing independent defence and foreign policies and distancing Australia from its traditional ties to Britain. But he continued to support Australia's involvement in the Vietnam War

The Vietnam War (also known by #Names, other names) was a conflict in Vietnam, Laos, and Cambodia from 1 November 1955 to the fall of Saigon on 30 April 1975. It was the second of the Indochina Wars and was officially fought between North Vie ...

, a position he had reluctantly inherited from Holt, which became increasingly unpopular after 1968. On domestic issues, he favoured centralist policies at the expense of the states, which alienated powerful Liberal state leaders like Sir Henry Bolte

Sir Henry Edward Bolte GCMG (20 May 1908 – 4 January 1990) was an Australian politician who served as the 38th Premier of Victoria. To date he is the longest-serving Victorian premier, having been in office for over 17 consecutive years.

E ...

of Victoria and Bob Askin

Sir Robert William Askin, GCMG (4 April 1907 – 9 September 1981), was an Australian politician and the 32nd Premier of New South Wales from 1965 to 1975, the first representing the Liberal Party. He was born in 1907 as Robin William Askin, but ...

of New South Wales. He also fostered an independent Australian film industry

The cinema of Australia had its beginnings with the 1906 production of '' The Story of the Kelly Gang'', arguably the world's first feature film. Since then, Australian crews have produced many films, a number of which have received internat ...

and increased government funding for the arts.

Gorton proved to be a surprisingly poor media performer and public speaker, and was portrayed by the media as a foolish and incompetent administrator. He was unlucky to come up against a new and formidable Labor Opposition Leader in Gough Whitlam

Edward Gough Whitlam (11 July 191621 October 2014) was the 21st prime minister of Australia, serving from 1972 to 1975. The longest-serving federal leader of the Australian Labor Party (ALP) from 1967 to 1977, he was notable for being the he ...

. Also, he was subjected to media speculation about his drinking habits and his involvements with women. He generated great resentment within his party, and his opponents became increasingly critical of his reliance on an inner circle of advisers – most notably his private secretary Ainsley Gotto

Ainsley Gotto (14 February 1946 – 25 February 2018) was an Australian public servant and entrepreneur, who was the private secretary to John Gorton, the Prime Minister of Australia in the late 1960s.

Early life

Gotto was born in the Brisbane ...

.

The Coalition suffered a 7% swing against it at the 1969 election, and Labor outpolled it on the two-party-preferred vote