John Dalton (abductor) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

John Dalton (; 5 or 6 September 1766 – 27 July 1844) was an English

Dalton's early life was influenced by a prominent Quaker, Elihu Robinson, a competent meteorologist and instrument maker, from Eaglesfield,

Dalton's early life was influenced by a prominent Quaker, Elihu Robinson, a competent meteorologist and instrument maker, from Eaglesfield,

Dalton published his first table of relative atomic weights containing six elements (hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, sulfur and phosphorus), relative to the weight of an atom of hydrogen conventionally taken as 1. Since these were only relative weights, they do not have a unit of weight attached to them. Dalton provided no indication in this paper how he had arrived at these numbers, but in his laboratory notebook, dated 6 September 1803, is a list in which he set out the relative weights of the atoms of a number of elements, derived from analysis of water, ammonia,

Dalton published his first table of relative atomic weights containing six elements (hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, sulfur and phosphorus), relative to the weight of an atom of hydrogen conventionally taken as 1. Since these were only relative weights, they do not have a unit of weight attached to them. Dalton provided no indication in this paper how he had arrived at these numbers, but in his laboratory notebook, dated 6 September 1803, is a list in which he set out the relative weights of the atoms of a number of elements, derived from analysis of water, ammonia,

Dalton never married and had only a few close friends. As a Quaker, he lived a modest and unassuming personal life.

For the 26 years prior to his death, Dalton lived in a room in the home of the Rev W. Johns, a published botanist, and his wife, in George Street, Manchester. Dalton and Johns died in the same year (1844).

Dalton's daily round of laboratory work and tutoring in Manchester was broken only by annual excursions to the

Dalton never married and had only a few close friends. As a Quaker, he lived a modest and unassuming personal life.

For the 26 years prior to his death, Dalton lived in a room in the home of the Rev W. Johns, a published botanist, and his wife, in George Street, Manchester. Dalton and Johns died in the same year (1844).

Dalton's daily round of laboratory work and tutoring in Manchester was broken only by annual excursions to the

*Much of Dalton's written work, collected by the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, was damaged during bombing on 24 December 1940. It prompted

*Much of Dalton's written work, collected by the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, was damaged during bombing on 24 December 1940. It prompted

Foundations of the Molecular Theory

'. Edinburgh: William F. Clay, 1893. Retrieved 15 August 2022 – with essays by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Amedeo Avogadro *

John Dalton Papers

at John Rylands Library, Manchester. *Dalton, John (1808–1827).

A New System of Chemical Philosophy

' (all images freely available for download in a variety of formats from Science History Institute Digital Collections a

digital.sciencehistory.org

. *Dalton, John (1794).

Extraordinary Facts Relating to the Vision of Colours: With Observations

'

Science History Institute Digital Collections

File:Dalton-5.png, 1793 copy of Dalton's ''"Meteorological Observations and Essays"''

File:Dalton-4.jpg, First page of ''"Meteorological Observations and Essays"''

File:Molecular theory-3.jpg, First page of a 1893 copy of "Foundations of the Molecular Theory" including Dalton's "''Extracts from a New System of Chemical Philosophy''"

File:Molecular theory-4.jpg, Second page of "''Extracts from a New System of Chemical Philosophy''"

File:Molecular theory-5.jpg, Third page of "''Extracts from a New System of Chemical Philosophy''"

John Dalton Manuscripts

at John Rylands Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Dalton, John 1766 births 1844 deaths English meteorologists People from Cockermouth English Quakers History of Greater Manchester People associated with the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology Royal Medal winners British physicists 18th-century British physicists 19th-century British physicists 18th-century British chemists 19th-century British chemists Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society Dalton Medal Color vision

chemist

A chemist (from Greek ''chēm(ía)'' alchemy; replacing ''chymist'' from Medieval Latin ''alchemist'') is a scientist trained in the study of chemistry. Chemists study the composition of matter and its properties. Chemists carefully describe th ...

, physicist

A physicist is a scientist who specializes in the field of physics, which encompasses the interactions of matter and energy at all length and time scales in the physical universe.

Physicists generally are interested in the root or ultimate caus ...

and meteorologist. He introduced the atomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. Atomic theory traces its origins to an ancient philosophical tradition known as atomism. According to this idea, if one were to take a lump of matter a ...

into chemistry. He also researched colour blindness

Color blindness or color vision deficiency (CVD) is the decreased ability to see color or differences in color. It can impair tasks such as selecting ripe fruit, choosing clothing, and reading traffic lights. Color blindness may make some aca ...

, which he had; as a result, colour blindness is known as ''Daltonism'' in several languages.

Early life

John Dalton was born into aQuaker

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of Christian denomination, denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belie ...

family in Eaglesfield, near Cockermouth, in Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, England. His father was a weaver. He received his early education from his father and from Quaker John Fletcher, who ran a private school in the nearby village of Pardshaw Hall. Dalton's family was too poor to support him for long and he began to earn his living, from the age of ten, in the service of wealthy local Quaker Elihu Robinson Elihu may refer to:

People

*Elihu Burritt (1811–1879), American philanthropist, linguist, and social activist

* Elihú Chávez (1988), Mexican Environmental Engineer with Renewable Energies Master Degree (ITESM 2019). Safety professional and LG ...

.

Early career

When he was 15, Dalton joined his older brother Jonathan in running a Quaker school inKendal

Kendal, once Kirkby in Kendal or Kirkby Kendal, is a market town and civil parish in the South Lakeland district of Cumbria, England, south-east of Windermere and north of Lancaster. Historically in Westmorland, it lies within the dale of th ...

, Westmorland

Westmorland (, formerly also spelt ''Westmoreland'';R. Wilkinson The British Isles, Sheet The British IslesVision of Britain/ref> is a historic county in North West England spanning the southern Lake District and the northern Dales. It had an ...

, about from his home. Around the age of 23, Dalton may have considered studying law or medicine, but his relatives did not encourage him, perhaps because being a Dissenter

A dissenter (from the Latin ''dissentire'', "to disagree") is one who dissents (disagrees) in matters of opinion, belief, etc.

Usage in Christianity

Dissent from the Anglican church

In the social and religious history of England and Wales, and ...

, he was barred from attending English universities. He acquired much scientific knowledge from informal instruction by John Gough, a blind philosopher who was gifted in the sciences and arts. At 27, he was appointed teacher of mathematics and natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior throu ...

at the "Manchester Academy" in Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

, a dissenting academy

The dissenting academies were schools, colleges and seminaries (often institutions with aspects of all three) run by English Dissenters, that is, those who did not conform to the Church of England. They formed a significant part of England's edu ...

(the lineal predecessor, following a number of changes of location, of Harris Manchester College, Oxford

Harris Manchester College is one of the constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It was founded in Warrington in 1757 as a college for Unitarian students and moved to Oxford in 1893. It became a full college of th ...

). He remained for seven years, until the college's worsening financial situation led to his resignation. Dalton began a new career as a private tutor in the same two subjects.

Scientific work

Meteorology

Dalton's early life was influenced by a prominent Quaker, Elihu Robinson, a competent meteorologist and instrument maker, from Eaglesfield,

Dalton's early life was influenced by a prominent Quaker, Elihu Robinson, a competent meteorologist and instrument maker, from Eaglesfield, Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, who interested him in problems of mathematics and meteorology. During his years in Kendal, Dalton contributed solutions to problems and answered questions on various subjects in ''The Ladies' Diary

''The Ladies' Diary: or, Woman's Almanack'' appeared annually in London from 1704 to 1841 after which it was succeeded by ''The Lady's and Gentleman's Diary''. It featured material relating to calendars etc. including sunrise and sunset times an ...

'' and the '' Gentleman's Diary''. In 1787 at age 21 he began his meteorological diary in which, during the succeeding 57 years, he entered more than 200,000 observations. He rediscovered George Hadley's theory of atmospheric circulation (now known as the Hadley cell) around this time. In 1793 Dalton's first publication, ''Meteorological Observations and Essays'', contained the seeds of several of his later discoveries but despite the originality of his treatment, little attention was paid to them by other scholars. A second work by Dalton, ''Elements of English Grammar'' (or ''A new system of grammatical instruction: for the use of schools and academies''), was published in 1801.

Measuring mountains

After leaving theLake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or ''fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

, Dalton returned annually to spend his holidays studying meteorology, something which involved a lot of hill-walking. Until the advent of aeroplanes and weather balloon

A weather balloon, also known as sounding balloon, is a balloon (specifically a type of high-altitude balloon) that carries instruments aloft to send back information on atmospheric pressure, temperature, humidity and wind speed by means of a ...

s, the only way to make measurements of temperature and humidity at altitude was to climb a mountain. Dalton estimated the height using a barometer. The Ordnance Survey

, nativename_a =

, nativename_r =

, logo = Ordnance Survey 2015 Logo.svg

, logo_width = 240px

, logo_caption =

, seal =

, seal_width =

, seal_caption =

, picture =

, picture_width =

, picture_caption =

, formed =

, preceding1 =

, di ...

did not publish maps for the Lake District until the 1860s. Before then, Dalton was one of the few authorities on the heights of the region's mountains. He was often accompanied by Jonathan Otley, who also made a study of the heights of the local peaks, using Dalton's figures as a comparison to check his work. Otley published his information in his map of 1818. Otley became both an assistant and a friend to Dalton.

Colour blindness

In 1794, shortly after his arrival in Manchester, Dalton was elected a member of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, the "Lit & Phil", and a few weeks later he communicated his first paper on "Extraordinary facts relating to the vision of colours", in which he postulated that shortage in colour perception was caused by discoloration of the liquid medium of the eyeball. As both he and his brother were colour blind, he recognised that the condition must be hereditary. Although Dalton's theory was later disproven, his early research into colour vision deficiency was recognized after his lifetime. Examination of his preserved eyeball in 1995 demonstrated that Dalton haddeuteranopia

Color blindness or color vision deficiency (CVD) is the decreased ability to see color or differences in color. It can impair tasks such as selecting ripe fruit, choosing clothing, and reading traffic lights. Color blindness may make some aca ...

, a type of congenital red-green color blindness

A birth defect, also known as a congenital disorder, is an abnormal condition that is present at childbirth, birth regardless of its cause. Birth defects may result in disability, disabilities that may be physical disability, physical, intellect ...

in which the gene for medium wavelength sensitive (green) photopsin

Vertebrate visual opsins are a subclass of ciliary opsins and mediate vision in vertebrates. They include the opsins in human rod and cone cells. They are often abbreviated to ''opsin'', as they were the first opsins discovered and are still th ...

s is missing. Individuals with this form of colour blindness see every color as mapped to blue, yellow or gray, or, as Dalton wrote in his seminal paper,

Gas laws

In 1800, Dalton became secretary of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, and in the following year he presented an important series of lectures, entitled "Experimental Essays" on the constitution of mixed gases; thepressure

Pressure (symbol: ''p'' or ''P'') is the force applied perpendicular to the surface of an object per unit area over which that force is distributed. Gauge pressure (also spelled ''gage'' pressure)The preferred spelling varies by country and e ...

of steam and other vapours at different temperatures in a vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or "void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often dis ...

and in air; on evaporation

Evaporation is a type of vaporization that occurs on the surface of a liquid as it changes into the gas phase. High concentration of the evaporating substance in the surrounding gas significantly slows down evaporation, such as when humidi ...

; and on the thermal expansion

Thermal expansion is the tendency of matter to change its shape, area, volume, and density in response to a change in temperature, usually not including phase transitions.

Temperature is a monotonic function of the average molecular kinetic ...

of gases. The four essays, presented between 2 and 30 October 1801, were published in the ''Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester'' in 1802.

The second essay opens with the remark,

After describing experiments to ascertain the pressure of steam at various points between 0 and 100 °C (32 and 212 °F), Dalton concluded from observations of the vapour pressure of six different liquids, that the variation of vapour pressure for all liquids is equivalent, for the same variation of temperature, reckoning from vapour of any given pressure.

In the fourth essay he remarks,

He enunciated Gay-Lussac's law

Gay-Lussac's law usually refers to Joseph-Louis Gay-Lussac's law of combining volumes of gases, discovered in 1808 and published in 1809. It sometimes refers to the proportionality of the volume of a gas to its absolute temperature at constant pr ...

, published in 1802 by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (Gay-Lussac credited the discovery to unpublished work from the 1780s by Jacques Charles). In the two or three years following the lectures, Dalton published several papers on similar topics. "On the Absorption of Gases by Water and other Liquids" (read as a lecture on 21 October 1803, first published in 1805) contained his law of partial pressures now known as Dalton's law.

Atomic theory

Arguably the most important of all Dalton's investigations are concerned with theatomic theory

Atomic theory is the scientific theory that matter is composed of particles called atoms. Atomic theory traces its origins to an ancient philosophical tradition known as atomism. According to this idea, if one were to take a lump of matter a ...

in chemistry. While his name is inseparably associated with this theory, the origin of Dalton's atomic theory is not fully understood. The theory may have been suggested to him either by researches on ethylene

Ethylene (IUPAC name: ethene) is a hydrocarbon which has the formula or . It is a colourless, flammable gas with a faint "sweet and musky" odour when pure. It is the simplest alkene (a hydrocarbon with carbon-carbon double bonds).

Ethylene i ...

(''olefiant gas'') and methane

Methane ( , ) is a chemical compound with the chemical formula (one carbon atom bonded to four hydrogen atoms). It is a group-14 hydride, the simplest alkane, and the main constituent of natural gas. The relative abundance of methane on Eart ...

(''carburetted hydrogen'') or by analysis of nitrous oxide

Nitrous oxide (dinitrogen oxide or dinitrogen monoxide), commonly known as laughing gas, nitrous, or nos, is a chemical compound, an oxide of nitrogen with the formula . At room temperature, it is a colourless non-flammable gas, and has a ...

(''protoxide of azote'') and nitrogen dioxide (''deutoxide of azote''), both views resting on the authority of Thomas Thomson Thomas Thomson may refer to:

* Tom Thomson (1877–1917), Canadian painter

* Thomas Thomson (apothecary) (died 1572), Scottish apothecary

* Thomas Thomson (advocate) (1768–1852), Scottish lawyer

* Thomas Thomson (botanist) (1817–1878), Scottis ...

.

From 1814 to 1819, Irish chemist William Higgins claimed that Dalton had plagiarised his ideas, but Higgins' theory did not address relative atomic mass. Recent evidence suggests that Dalton's development of thought may have been influenced by the ideas of another Irish chemist Bryan Higgins

Bryan Higgins (1741 – 1818) was an Irish natural philosopher in chemistry.

He was born in Collooney, County Sligo, Ireland. His father (d. 1777) was also called Dr. Bryan Higgins. Higgins entered the University of Leiden in 1765, whence he qua ...

, who was William's uncle. Bryan believed that an atom was a heavy central particle surrounded by an atmosphere of caloric

Caloric is a brand of kitchen appliances, which dates back to 1903.

History

Caloric Corporation began as the Klein Stove Company in Philadelphia in 1890. The Caloric brand was introduced in 1903. It was reorganized in 1946 as the Caloric Stove C ...

, the supposed substance of heat at the time. The size of the atom was determined by the diameter of the caloric atmosphere. Based on the evidence, Dalton was aware of Bryan's theory and adopted very similar ideas and language, but he never acknowledged Bryan's anticipation of his caloric model. However, the essential novelty of Dalton's atomic theory is that he provided a method of calculating relative atomic weights for the chemical elements, which provides the means for the assignment of molecular formulas for all chemical substances. Neither Bryan nor William Higgins did this, and Dalton's priority for that crucial innovation is uncontested.

A study of Dalton's laboratory notebooks, discovered in the rooms of the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, concluded that so far from Dalton being led by his search for an explanation of the law of multiple proportions to the idea that chemical combination consists in the interaction of atoms of definite and characteristic weight, the idea of atoms arose in his mind as a purely physical concept, forced on him by study of the physical properties of the atmosphere

An atmosphere () is a layer of gas or layers of gases that envelop a planet, and is held in place by the gravity of the planetary body. A planet retains an atmosphere when the gravity is great and the temperature of the atmosphere is low. A s ...

and other gases. The first published indications of this idea are to be found at the end of his paper "On the Absorption of Gases by Water and other Liquids" already mentioned. There he says:

He then proposes relative weights for the atoms of a few elements, without going into further detail. However, a recent study of Dalton’s laboratory notebook entries concludes he developed the chemical atomic theory in 1803 to reconcile Henry Cavendish’s and Antoine Lavoisier’s analytical data on the composition of nitric acid, not to explain the solubility of gases in water.

The main points of Dalton's atomic theory, as it eventually developed, are:

# Elements are made of extremely small particles called atom

Every atom is composed of a nucleus and one or more electrons bound to the nucleus. The nucleus is made of one or more protons and a number of neutrons. Only the most common variety of hydrogen has no neutrons.

Every solid, liquid, gas, and ...

s.

# Atoms of a given element are identical in size, mass and other properties; atoms of different elements differ in size, mass and other properties.

# Atoms cannot be subdivided, created or destroyed.

# Atoms of different elements combine in simple whole-number ratios to form chemical compounds.

# In chemical reactions

A chemical reaction is a process that leads to the chemical transformation of one set of chemical substances to another. Classically, chemical reactions encompass changes that only involve the positions of electrons in the forming and breaking ...

, atoms are combined, separated or rearranged.

In his first extended published discussion of the atomic theory (1808), Dalton proposed an additional (and controversial) "rule of greatest simplicity". This rule could not be independently confirmed, but some such assumption was necessary in order to propose formulas for a few simple molecules, upon which the calculation of atomic weights depended. This rule dictated that if the atoms of two different elements were known to form only a single compound, like hydrogen and oxygen forming water or hydrogen and nitrogen forming ammonia, the molecules of that compound shall be assumed to consist of one atom of each element. For elements that combined in multiple ratios, such as the then-known two oxides of carbon or the three oxides of nitrogen, their combinations were assumed to be the simplest ones possible. For example, if two such combinations are known, one must consist of an atom of each element, and the other must consist of one atom of one element and two atoms of the other.

This was merely an assumption, derived from faith in the simplicity of nature. No evidence was then available to scientists to deduce how many atoms of each element combine to form molecules. But this or some other such rule was absolutely necessary to any incipient theory, since one needed an assumed molecular formula in order to calculate relative atomic weights. Dalton's "rule of greatest simplicity" caused him to assume that the formula for water was OH and ammonia

Ammonia is an inorganic compound of nitrogen and hydrogen with the formula . A stable binary hydride, and the simplest pnictogen hydride, ammonia is a colourless gas with a distinct pungent smell. Biologically, it is a common nitrogenous was ...

was NH, quite different from our modern understanding (H2O, NH3). On the other hand, his simplicity rule led him to propose the correct modern formulas for the two oxides of carbon (CO and CO2). Despite the uncertainty at the heart of Dalton's atomic theory, the principles of the theory survived.

Relative atomic weights

Dalton published his first table of relative atomic weights containing six elements (hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, sulfur and phosphorus), relative to the weight of an atom of hydrogen conventionally taken as 1. Since these were only relative weights, they do not have a unit of weight attached to them. Dalton provided no indication in this paper how he had arrived at these numbers, but in his laboratory notebook, dated 6 September 1803, is a list in which he set out the relative weights of the atoms of a number of elements, derived from analysis of water, ammonia,

Dalton published his first table of relative atomic weights containing six elements (hydrogen, oxygen, nitrogen, carbon, sulfur and phosphorus), relative to the weight of an atom of hydrogen conventionally taken as 1. Since these were only relative weights, they do not have a unit of weight attached to them. Dalton provided no indication in this paper how he had arrived at these numbers, but in his laboratory notebook, dated 6 September 1803, is a list in which he set out the relative weights of the atoms of a number of elements, derived from analysis of water, ammonia, carbon dioxide

Carbon dioxide (chemical formula ) is a chemical compound made up of molecules that each have one carbon atom covalently double bonded to two oxygen atoms. It is found in the gas state at room temperature. In the air, carbon dioxide is transpar ...

, etc. by chemists of the time.

The extension of this idea to substances in general necessarily led him to the law of multiple proportions, and the comparison with experiment brilliantly confirmed his deduction. In the paper "On the Proportion of the Several Gases in the Atmosphere", read by him in November 1802, the law of multiple proportions appears to be anticipated in the words:

But there is reason to suspect that this sentence may have been added some time after the reading of the paper, which was not published until 1805.

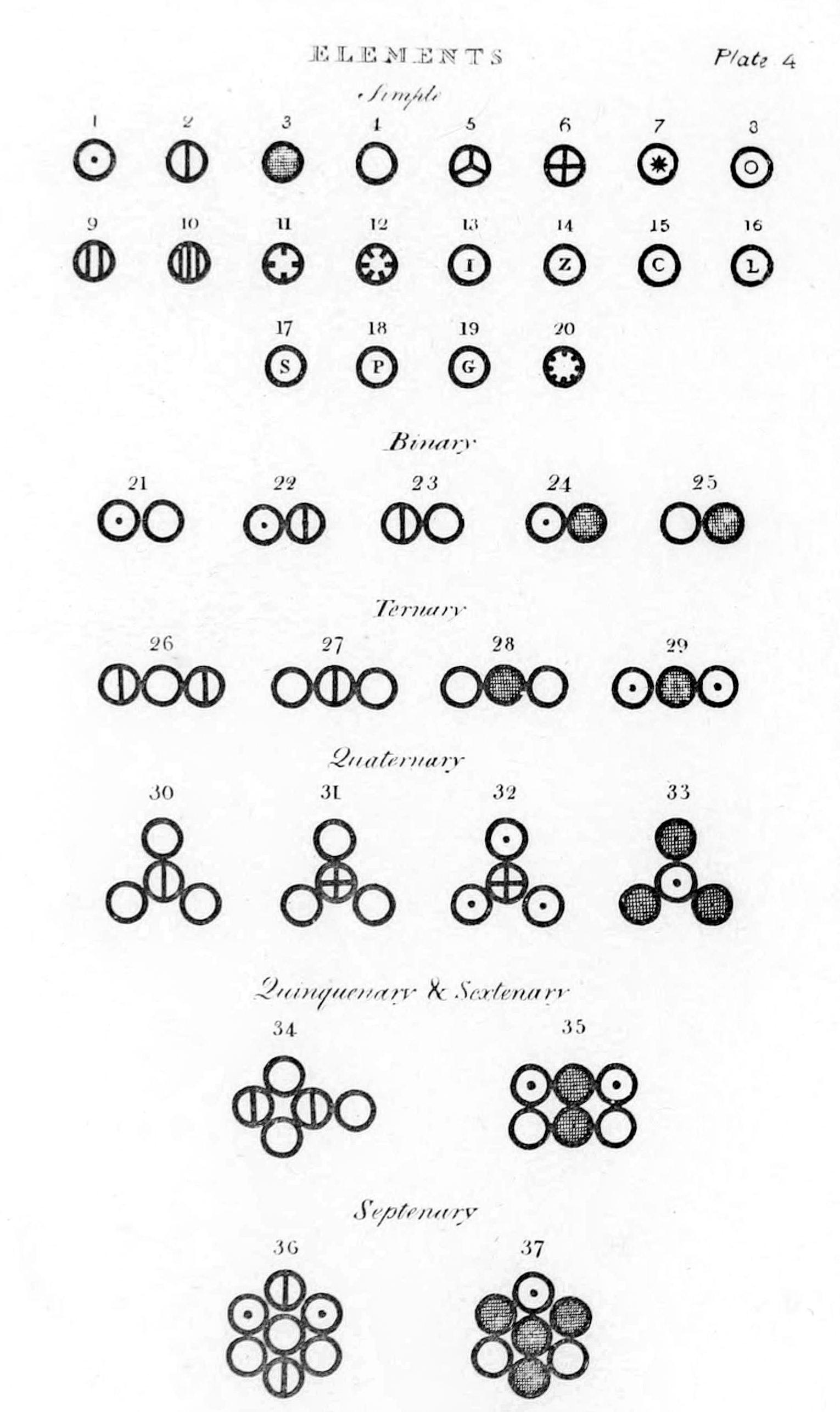

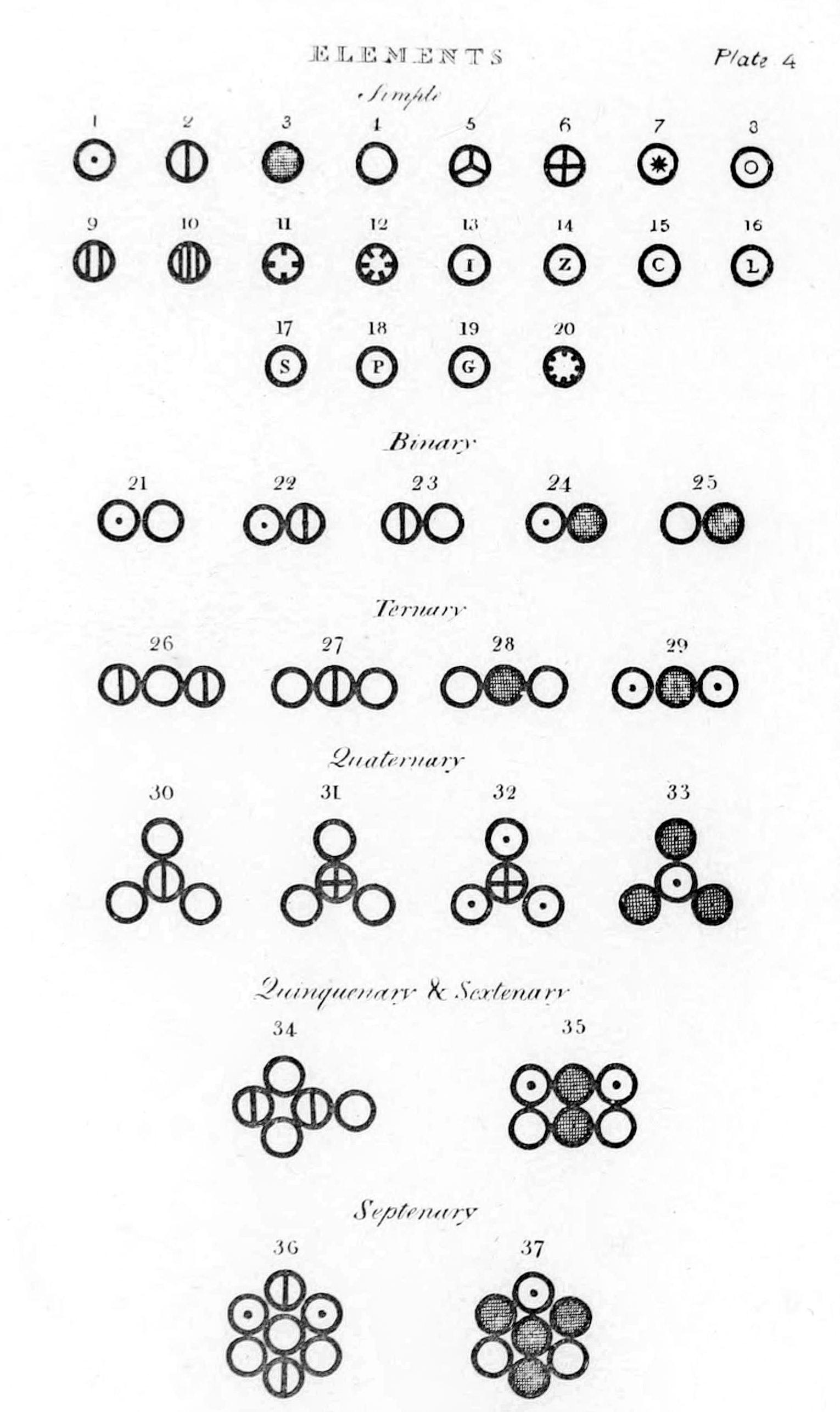

Compounds were listed as binary, ternary, quaternary, etc. (molecules composed of two, three, four, etc. atoms) in the ''New System of Chemical Philosophy'' depending on the number of atoms a compound had in its simplest, empirical form.

Dalton hypothesised the structure of compounds can be represented in whole number ratios. So, one atom of element X combining with one atom of element Y is a binary compound. Furthermore, one atom of element X combining with two atoms of element Y or vice versa, is a ternary compound. Many of the first compounds listed in the ''New System of Chemical Philosophy'' correspond to modern views, although many others do not.

Dalton used his own symbols to visually represent the atomic structure of compounds. They were depicted in the ''New System of Chemical Philosophy'', where he listed 21 elements and 17 simple molecules.

Other investigations

Dalton published papers on such diverse topics as rain and dew and the origin of springs (hydrosphere); on heat, the colour of the sky, steam and the reflection andrefraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomeno ...

of light; and on the grammatical subjects of the auxiliary verbs and participle

In linguistics, a participle () (from Latin ' a "sharing, partaking") is a nonfinite verb form that has some of the characteristics and functions of both verbs and adjectives. More narrowly, ''participle'' has been defined as "a word derived from ...

s of the English language.

Experimental approach

As an investigator, Dalton was often content with rough and inaccurate instruments, even though better ones were obtainable. SirHumphry Davy

Sir Humphry Davy, 1st Baronet, (17 December 177829 May 1829) was a British chemist and inventor who invented the Davy lamp and a very early form of arc lamp. He is also remembered for isolating, by using electricity, several elements for t ...

described him as "a very coarse experimenter", who "almost always found the results he required, trusting to his head rather than his hands." On the other hand, historians who have replicated some of his crucial experiments have confirmed Dalton's skill and precision.

In the preface to the second part of Volume I of his ''New System'', he says he had so often been misled by taking for granted the results of others that he determined to write "as little as possible but what I can attest by my own experience", but this independence he carried so far that it sometimes resembled lack of receptivity. Thus he distrusted, and probably never fully accepted, Gay-Lussac

Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac (, , ; 6 December 1778 – 9 May 1850) was a French chemist and physicist. He is known mostly for his discovery that water is made of two parts hydrogen and one part oxygen (with Alexander von Humboldt), for two laws ...

's conclusions as to the combining volumes of gases.

He held unconventional views on chlorine

Chlorine is a chemical element with the Symbol (chemistry), symbol Cl and atomic number 17. The second-lightest of the halogens, it appears between fluorine and bromine in the periodic table and its properties are mostly intermediate betwee ...

. Even after its elementary character had been settled by Davy, he persisted in using the atomic weights he himself had adopted, even when they had been superseded by the more accurate determinations of other chemists.

He always objected to the chemical notation devised by Jöns Jacob Berzelius

Baron Jöns Jacob Berzelius (; by himself and his contemporaries named only Jacob Berzelius, 20 August 1779 – 7 August 1848) was a Swedish chemist. Berzelius is considered, along with Robert Boyle, John Dalton, and Antoine Lavoisier, to be on ...

, although most thought that it was much simpler and more convenient than his own cumbersome system of circular symbols.

Other publications

For ''Rees's Cyclopædia

Rees's ''Cyclopædia'', in full ''The Cyclopædia; or, Universal Dictionary of Arts, Sciences, and Literature'' was an important 19th-century British encyclopaedia edited by Rev. Abraham Rees (1743–1825), a Presbyterian minister and scholar w ...

'' Dalton contributed articles on Chemistry and Meteorology, but the topics are not known.

He contributed 117 ''Memoirs of the Literary and Philosophical Society of Manchester'' from 1817 until his death in 1844 while president of that organisation. Of these the earlier are the most important. In one of them, read in 1814, he explains the principles of volumetric analysis

Titration (also known as titrimetry and volumetric analysis) is a common laboratory method of quantitative chemical analysis to determine the concentration of an identified analyte (a substance to be analyzed). A reagent, termed the ''titrant'' ...

, in which he was one of the earliest researchers. In 1840 a paper on phosphate

In chemistry, a phosphate is an anion, salt, functional group or ester derived from a phosphoric acid. It most commonly means orthophosphate, a derivative of orthophosphoric acid .

The phosphate or orthophosphate ion is derived from phospho ...

s and arsenates, often regarded as a weaker work, was refused by the Royal Society

The Royal Society, formally The Royal Society of London for Improving Natural Knowledge, is a learned society and the United Kingdom's national academy of sciences. The society fulfils a number of roles: promoting science and its benefits, re ...

, and he was so incensed that he published it himself. He took the same course soon afterwards with four other papers, two of which ("On the quantity of acid

In computer science, ACID ( atomicity, consistency, isolation, durability) is a set of properties of database transactions intended to guarantee data validity despite errors, power failures, and other mishaps. In the context of databases, a sequ ...

s, bases and salts in different varieties of salts" and "On a new and easy method of analysing sugar") contain his discovery, regarded by him as second in importance only to atomic theory, that certain anhydrate

An acidic oxide is an oxide that either produces an acidic solution upon addition to water, or acts as an acceptor of hydroxide ions effectively functioning as a Lewis acid. Acidic oxides will typically have a low pKa and may be inorganic compoun ...

s, when dissolved in water, cause no increase in its volume, his inference being that the salt enters into the pores of the water.

Public life

Even before he had propounded the atomic theory, Dalton had attained a considerable scientific reputation. In 1803, he was chosen to give a series of lectures on natural philosophy at theRoyal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

in London, and he delivered another series of lectures there in 1809–1810. Some witnesses reported that he was deficient in the qualities that make an attractive lecturer, being harsh and indistinct in voice, ineffective in the treatment of his subject, and singularly wanting in the language and power of illustration.

In 1810, Sir Humphry Davy asked him to offer himself as a candidate for the fellowship of the Royal Society, but Dalton declined, possibly for financial reasons. In 1822 he was proposed without his knowledge, and on election paid the usual fee. Six years previously he had been made a corresponding member of the French Académie des Sciences

The French Academy of Sciences (French: ''Académie des sciences'') is a learned society, founded in 1666 by Louis XIV at the suggestion of Jean-Baptiste Colbert, to encourage and protect the spirit of French scientific research. It was at the ...

, and in 1830 he was elected as one of its eight foreign associates in place of Davy. In 1833, Earl Grey's government conferred on him a pension of £150, raised in 1836 to £300 (equivalent to £ and £ in , respectively). Dalton was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

in 1834.

A young James Prescott Joule, who later studied and published (1843) on the nature of heat and its relationship to mechanical work, was a pupil of Dalton in his last years.

Personal life

Dalton never married and had only a few close friends. As a Quaker, he lived a modest and unassuming personal life.

For the 26 years prior to his death, Dalton lived in a room in the home of the Rev W. Johns, a published botanist, and his wife, in George Street, Manchester. Dalton and Johns died in the same year (1844).

Dalton's daily round of laboratory work and tutoring in Manchester was broken only by annual excursions to the

Dalton never married and had only a few close friends. As a Quaker, he lived a modest and unassuming personal life.

For the 26 years prior to his death, Dalton lived in a room in the home of the Rev W. Johns, a published botanist, and his wife, in George Street, Manchester. Dalton and Johns died in the same year (1844).

Dalton's daily round of laboratory work and tutoring in Manchester was broken only by annual excursions to the Lake District

The Lake District, also known as the Lakes or Lakeland, is a mountainous region in North West England. A popular holiday destination, it is famous for its lakes, forests, and mountains (or ''fells''), and its associations with William Wordswor ...

and occasional visits to London. In 1822 he paid a short visit to Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, where he met many distinguished resident men of science. He attended several of the earlier meetings of the British Association at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

, Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

, Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

and Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

.

Disability and death

Dalton suffered a minor stroke in 1837, and a second in 1838 left him with a speech impairment, although he remained able to perform experiments. In May 1844 he had another stroke; on 26 July, while his hand was trembling, he recorded his last meteorological observation. On 27 July, in Manchester, Dalton fell from his bed and was found dead by his attendant. Dalton was accorded a civic funeral with full honours. His body lay in state inManchester Town Hall

Manchester Town Hall is a Victorian, Neo-gothic municipal building in Manchester, England. It is the ceremonial headquarters of Manchester City Council and houses a number of local government departments. The building faces Albert Square to th ...

for four days and more than 40,000 people filed past his coffin. The funeral procession included representatives of the city's major civic, commercial, and scientific bodies. He was buried in Manchester in Ardwick Cemetery

Ardwick is a district of Manchester in North West England, one mile south east of the city centre. The population of the Ardwick Ward at the 2011 census was 19,250.

Historically in Lancashire, by the mid-nineteenth century Ardwick had grown from ...

; the cemetery is now a playing field, but pictures of the original grave may be found in published materials.

Legacy

*Much of Dalton's written work, collected by the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, was damaged during bombing on 24 December 1940. It prompted

*Much of Dalton's written work, collected by the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society, was damaged during bombing on 24 December 1940. It prompted Isaac Asimov

yi, יצחק אזימאװ

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Petrovichi, Russian SFSR

, spouse =

, relatives =

, children = 2

, death_date =

, death_place = Manhattan, New York City, U.S.

, nationality = Russian (1920–1922)Soviet (192 ...

to say, "John Dalton's records, carefully preserved for a century, were destroyed during the World War II bombing of Manchester. It is not only the living who are killed in war". The damaged papers are in the John Rylands Library.

*A bust of Dalton, by Chantrey, paid for by public subscription was placed in the entrance hall of the Royal Manchester Institution. Chantrey's large statue of Dalton, erected while Dalton was alive was placed in Manchester Town Hall

Manchester Town Hall is a Victorian, Neo-gothic municipal building in Manchester, England. It is the ceremonial headquarters of Manchester City Council and houses a number of local government departments. The building faces Albert Square to th ...

in 1877. He "is probably the only scientist who got a statue in his lifetime".

* The Manchester-based Swiss phrenologist

Phrenology () is a pseudoscience which involves the measurement of bumps on the skull to predict mental traits.Wihe, J. V. (2002). "Science and Pseudoscience: A Primer in Critical Thinking." In ''Encyclopedia of Pseudoscience'', pp. 195–203. C ...

and sculptor William Bally made a cast of the interior of Dalton's cranium and of a cyst therein, having arrived at the Manchester Royal Infirmary

Manchester Royal Infirmary (MRI) is a large NHS teaching hospital in Chorlton-on-Medlock, Manchester, England. Founded by Charles White in 1752 as part of the voluntary hospital movement of the 18th century, it is now a major regional and nati ...

too late to make a cast of the head and face. A cast of the head was made, by a Mr Politi, whose arrival at the scene preceded that of Bally.

*John Dalton Street connects Deansgate

Deansgate is a main road (part of the A56) through Manchester City Centre, England. It runs roughly north–south in a near straight route through the western part of the city centre and is the longest road in the city centre at over one mile ...

and Albert Square in the centre of Manchester.

*The John Dalton building at Manchester Metropolitan University is occupied by the Faculty of Science and Engineering. Outside it stands William Theed

William Theed, also known as William Theed the younger (1804 – 9 September 1891), was a British sculptor, the son of the sculptor and painter William Theed the elder (1764–1817). Although versatile and eclectic in his works, he specialised ...

's statue of Dalton, erected in Piccadilly

Piccadilly () is a road in the City of Westminster, London, to the south of Mayfair, between Hyde Park Corner in the west and Piccadilly Circus in the east. It is part of the A4 road that connects central London to Hammersmith, Earl's Court, ...

in 1855, and moved there in 1966.

*A blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

commemorates the site of his laboratory at 36 George Street in Manchester.

*The University of Manchester

, mottoeng = Knowledge, Wisdom, Humanity

, established = 2004 – University of Manchester Predecessor institutions: 1956 – UMIST (as university college; university 1994) 1904 – Victoria University of Manchester 1880 – Victoria Univer ...

established two Dalton Chemical Scholarships, two Dalton Mathematical Scholarships, and a Dalton Prize for Natural History. A hall of residence is named Dalton Hall.

*The Dalton Medal has been awarded only twelve times by the Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society.

*The Dalton crater on the Moon was named after Dalton.

*"Daltonism" is a lesser-known synonym of colour-blindness and, in some languages, variations on this have persisted in common usage: for example, 'daltonien' is the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

adjectival equivalent of 'colour-blind', and 'daltónico'/'daltonica' is the Spanish and the Italian.

*The inorganic section of the UK's Royal Society of Chemistry

The Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) is a learned society (professional association) in the United Kingdom with the goal of "advancing the chemistry, chemical sciences". It was formed in 1980 from the amalgamation of the Chemical Society, the Ro ...

is named the Dalton Division, and the society's academic journal for inorganic chemistry is called Dalton Transactions.

*In honour of Dalton's work, many chemists and biochemists use the unit of mass dalton (symbol Da), also known as the unified atomic mass unit, equal to 1/12 the mass of a neutral atom of carbon-12

Carbon-12 (12C) is the most abundant of the two stable isotopes of carbon (carbon-13 being the other), amounting to 98.93% of element carbon on Earth; its abundance is due to the triple-alpha process by which it is created in stars. Carbon-12 i ...

). The dalton is officially accepted for use with the SI.

*Quaker schools have named buildings after Dalton: for example, a schoolhouse in the primary sector of Ackworth School

Ackworth School is an independent day and boarding school located in the village of High Ackworth, near Pontefract, West Yorkshire, England. It is one of seven Quaker schools in England. The school (or more accurately its Head) is a member ...

, is called Dalton.

* Dalton Township in southern Ontario was named after him. In 2001 the name was lost when the township was absorbed into the City of Kawartha Lakes but in 2002 the Dalton name was affixed to a new park, Dalton Digby Wildlands Provincial Park

The Queen Elizabeth II Wildlands Provincial Park is a provincial park in south-central Ontario, Canada, between Gravenhurst and Minden. The park, named for Elizabeth II, who at the time was Queen of Canada, is 33,505 hectares in size, making it ...

.

Works

* * – Alembic Club reprint with some of Dalton's papers, along with some byWilliam Hyde Wollaston

William Hyde Wollaston (; 6 August 1766 – 22 December 1828) was an English chemist and physicist who is famous for discovering the chemical elements palladium and rhodium. He also developed a way to process platinum ore into malleable ingo ...

and Thomas Thomson Thomas Thomson may refer to:

* Tom Thomson (1877–1917), Canadian painter

* Thomas Thomson (apothecary) (died 1572), Scottish apothecary

* Thomas Thomson (advocate) (1768–1852), Scottish lawyer

* Thomas Thomson (botanist) (1817–1878), Scottis ...

* Dalton, John (1893.) Foundations of the Molecular Theory

'. Edinburgh: William F. Clay, 1893. Retrieved 15 August 2022 – with essays by Joseph Louis Gay-Lussac and Amedeo Avogadro *

John Dalton Papers

at John Rylands Library, Manchester. *Dalton, John (1808–1827).

A New System of Chemical Philosophy

' (all images freely available for download in a variety of formats from Science History Institute Digital Collections a

digital.sciencehistory.org

. *Dalton, John (1794).

Extraordinary Facts Relating to the Vision of Colours: With Observations

'

Science History Institute Digital Collections

See also

*Kaṇāda_(philosopher)

Kaṇāda (), also known as Ulūka, Kashyapa, Kaṇabhaksha, Kaṇabhuj was an ancient Indian natural scientist and philosopher who founded the Vaisheshika school of Indian philosophy that also represents the earliest Indian physics.

Estimat ...

* Democritus

Democritus (; el, Δημόκριτος, ''Dēmókritos'', meaning "chosen of the people"; – ) was an Ancient Greek pre-Socratic philosopher from Abdera, primarily remembered today for his formulation of an atomic theory of the universe. No ...

* Pneumatic chemistry

In the history of science, pneumatic chemistry is an area of scientific research of the seventeenth, eighteenth, and early nineteenth centuries. Important goals of this work were the understanding of the physical properties of gases and how they ...

Notes

References

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * * - Original edition published by Manchester University Press in 1966 *External links

* * * *John Dalton Manuscripts

at John Rylands Library {{DEFAULTSORT:Dalton, John 1766 births 1844 deaths English meteorologists People from Cockermouth English Quakers History of Greater Manchester People associated with the University of Manchester Institute of Science and Technology Royal Medal winners British physicists 18th-century British physicists 19th-century British physicists 18th-century British chemists 19th-century British chemists Fellows of the Royal Society Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences Manchester Literary and Philosophical Society Dalton Medal Color vision