Jewish deicide on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jewish deicide is the notion that the

"Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations"

November 16, 1998World Council of Churche

i

July, 1999

According to the gospel accounts, Jewish authorities in

According to the gospel accounts, Jewish authorities in

''Jews and Gentiles in the Early Jesus Movement: An Unintended Journey''

Palgrave Macmillan, 2013 pp. 180–182. This text blames the Jews for allowing King Herod and

Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""T ...

as a people were collectively responsible for the killing of Jesus. A Biblical justification for the charge of Jewish deicide is derived from Matthew 27:24–25. Some rabbinical authorities, such as Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

and, more recently, Zvi Yehuda Kook

Zvi Yehuda Kook ( he, צבי יהודה קוק, 23 April 1891 – 9 March 1982) was a prominent ultranationalist Orthodox rabbi. He was the son of Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Hacohen Kook, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandatory Pales ...

have asserted that Jesus was indeed stoned and hanged after being sentenced to death in a rabbinical court.

The notion arose in early Christianity

Early Christianity (up to the First Council of Nicaea in 325) spread from the Levant, across the Roman Empire, and beyond. Originally, this progression was closely connected to already established Jewish centers in the Holy Land and the Je ...

, the charge was made by Justin Martyr

Justin Martyr ( el, Ἰουστῖνος ὁ μάρτυς, Ioustinos ho martys; c. AD 100 – c. AD 165), also known as Justin the Philosopher, was an early Christian apologist and philosopher.

Most of his works are lost, but two apologies and ...

and Melito of Sardis

Melito of Sardis ( el, Μελίτων Σάρδεων ''Melítōn Sárdeōn''; died ) was the bishop of Sardis near Smyrna in western Anatolia, and a great authority in early Christianity. Melito held a foremost place in terms of bishops in Asia ...

as early as the 2nd century. The accusation that the Jews were Christ-killers fed Christian antisemitism and spurred on acts of violence against Jews such as pogroms

A pogrom () is a violent riot incited with the aim of massacring or expelling an ethnic or religious group, particularly Jews. The term entered the English language from Russian to describe 19th- and 20th-century attacks on Jews in the Russian E ...

, massacres of Jews during the Crusades, expulsions of the Jews from England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe ...

, France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic, Pacific and Indian Oceans. Its metropolitan ar ...

, Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = '' Plus ultra'' ( Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic, In recognized minority languages of Portugal:

:* mwl, República Pertuesa is a country located on the Iberian Peninsula, in Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Macaronesian ...

and other places, and torture during the Spanish

Spanish might refer to:

* Items from or related to Spain:

** Spaniards are a nation and ethnic group indigenous to Spain

**Spanish language, spoken in Spain and many Latin American countries

**Spanish cuisine

Other places

* Spanish, Ontario, Ca ...

and Portuguese Inquisition

The Portuguese Inquisition ( Portuguese: ''Inquisição Portuguesa''), officially known as the General Council of the Holy Office of the Inquisition in Portugal, was formally established in Portugal in 1536 at the request of its king, John III. ...

s.

In the catechism which was produced by the Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation, it has been described ...

in the mid-16th century, the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

taught the belief that the collectivity of sinful humanity was responsible for the death of Jesus, not only the Jews. In the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

(1962–1965), the Catholic Church under Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his death in Augus ...

issued the declaration ''Nostra aetate

(from Latin: "In our time") is the incipit of the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions of the Second Vatican Council. Passed by a vote of 2,221 to 88 of the assembled bishops, this declaration was promulgated o ...

'' that repudiated the idea of a collective, multigenerational Jewish guilt for the crucifixion of Jesus. It declared that the accusation could not be made "against all the Jews, without distinction, then alive, nor against the Jews of today".

Most other churches do not have any binding position on the matter, but some Christian denominations have issued declarations against the accusation.Evangelical Lutheran Church in Americ"Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations"

November 16, 1998World Council of Churche

i

July, 1999

Sources

Matthew 27:24–25

A justification for the charge of Jewish deicide has been sought in Matthew 27:24–25: The verse which reads: "And all the people answered, 'His blood be on us and on our children! is also referred to as theblood curse

The term "blood curse" refers to a New Testament passage from the Gospel of Matthew, which describes events taking place in Pilate's court before the crucifixion of Jesus and specifically the apparent willingness of the Jewish crowd to accep ...

. In an essay regarding antisemitism, biblical scholar Amy-Jill Levine

{{Infobox academic

, name = Amy-Jill Levine

, image =

, alt =

, caption =

, birth_name =

, birth_date = {{birth year and age, 1956

, birth_place =

, death_date =

, death_place =

, nationality = American

, other_names = A. J. ...

argues that this passage has caused more suffering throughout Jewish history

Jewish history is the history of the Jews, and their nation, religion, and culture, as it developed and interacted with other peoples, religions, and cultures. Although Judaism as a religion first appears in Greek records during the Hellenisti ...

than any other passage in the New Testament.

Many also point to the Gospel of John

The Gospel of John ( grc, Εὐαγγέλιον κατὰ Ἰωάννην, translit=Euangélion katà Iōánnēn) is the fourth of the four canonical gospels. It contains a highly schematic account of the ministry of Jesus, with seven "sig ...

as evidence of Christian charges of deicide. As Samuel Sandmel writes, "John is widely regarded as either the most anti-Semitic or at least the most overtly anti-Semitic of the gospels." Support for this claim comes in several places throughout John, such as in John 5:16–18:

Some scholars describe this passage as irrefutably referencing and implicating the Jews in deicide, although many, such as scholar Robert Kysar, also argue that part of the severity of this charge comes more from those who read and understand the text than the text itself. John uses the term , ''Ioudaioi

''Ioudaios'' ( grc, Ἰουδαῖος; pl. ''Ioudaioi''). is an Ancient Greek ethnonym used in classical and biblical literature which commonly translates to "Jew" or "Judean".

The choice of translation is the subject of frequent scholarly de ...

'', meaning "the Jews" or "the Judeans", as the subject of these sentences. However, the notion that the Jew is meant to represent all Jews is often disputed, with many English translations rendering the phrase more specifically as "Jewish leaders". While the New Testament is often more subtle or leveled in accusations of deicide, many scholars hold that these works cannot be held in isolation, and must be considered in the context of their interpretation by later Christian communities.

Historicity of Matthew 27:24–25

According to the gospel accounts, Jewish authorities in

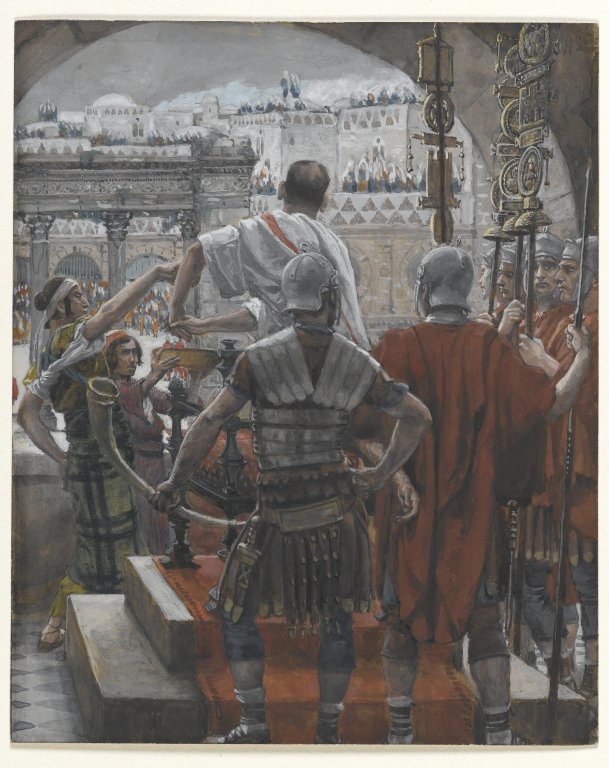

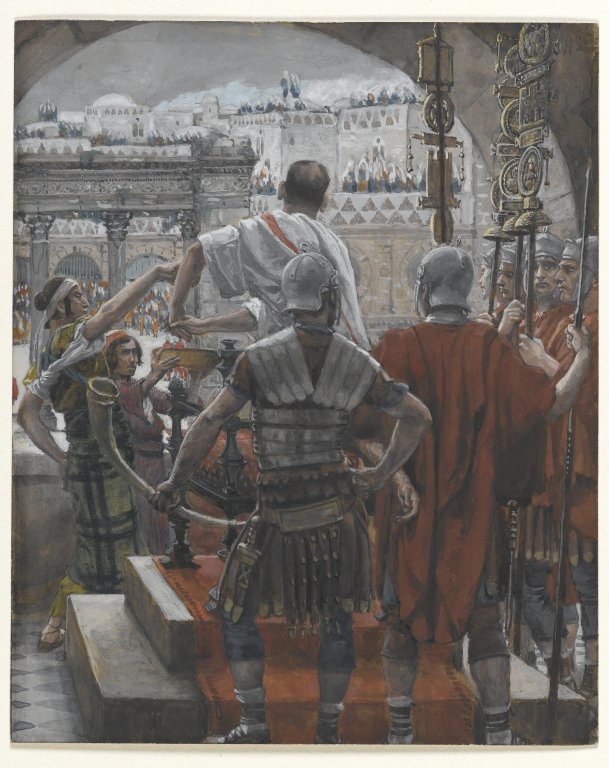

According to the gospel accounts, Jewish authorities in Roman Judea

Judaea ( la, Iudaea ; grc, Ἰουδαία, translit=Ioudaíā ) was a Roman province which incorporated the regions of Judea, Samaria, and Idumea from 6 CE, extending over parts of the former regions of the Hasmonean and Herodian kingdoms o ...

charged Jesus with blasphemy

Blasphemy is a speech crime and religious crime usually defined as an utterance that shows contempt, disrespects or insults a deity, an object considered sacred or something considered inviolable. Some religions regard blasphemy as a religio ...

and sought his execution, but lacked the authority to have Jesus put to death ( John 18:31), so they brought Jesus to Pontius Pilate

Pontius Pilate (; grc-gre, Πόντιος Πιλᾶτος, ) was the fifth governor of the Roman province of Judaea, serving under Emperor Tiberius from 26/27 to 36/37 AD. He is best known for being the official who presided over the trial of ...

, the Roman governor of the province, who authorized Jesus' execution (John 19

John 19 is the nineteenth chapter of the Gospel of John in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The book containing this chapter is anonymous, but early Christian tradition uniformly affirmed that John composed this Gospel.Holman Illustrate ...

:16).''The Historical Jesus Through Catholic and Jewish Eyes'' by Bryan F. Le Beau, Leonard J. Greenspoon and Dennis Hamm (Nov 1, 2000) pages 105-106 The Jesus Seminar

The Jesus Seminar was a group of about 50 critical biblical scholars and 100 laymen founded in 1985 by Robert Funk that originated under the auspices of the Westar Institute.''Making Sense of the New Testament'' by Craig Blomberg (Mar 1, 2004) ...

's ''Scholars Version'' translation note for John 18:31 adds: "''it's illegal for us'': The accuracy of this claim is doubtful." It is noted, for example, that Jewish authorities were responsible for the stoning

Stoning, or lapidation, is a method of capital punishment where a group throws stones at a person until the subject dies from blunt trauma. It has been attested as a form of punishment for grave misdeeds since ancient times.

The Torah and T ...

of Saint Stephen

Stephen ( grc-gre, Στέφανος ''Stéphanos'', meaning "wreath, crown" and by extension "reward, honor, renown, fame", often given as a title rather than as a name; c. 5 – c. 34 AD) is traditionally venerated as the protomartyr or first ...

in Acts 7

Acts 7 is the seventh chapter of the Acts of the Apostles in the New Testament of the Christian Bible. It records the address of Stephen before the Sanhedrin and his execution outside Jerusalem, and introduces Saul (who later became Paul the Ap ...

:54 and of James the Just

James the Just, or a variation of James, brother of the Lord ( la, Iacobus from he, יעקב, and grc-gre, Ἰάκωβος, , can also be Anglicized as " Jacob"), was "a brother of Jesus", according to the New Testament. He was an early l ...

in Antiquities of the Jews

''Antiquities of the Jews'' ( la, Antiquitates Iudaicae; el, Ἰουδαϊκὴ ἀρχαιολογία, ''Ioudaikē archaiologia'') is a 20-volume historiographical work, written in Greek, by historian Flavius Josephus in the 13th year of the ...

without the consent of the governor. Josephus

Flavius Josephus (; grc-gre, Ἰώσηπος, ; 37 – 100) was a first-century Romano-Jewish historian and military leader, best known for '' The Jewish War'', who was born in Jerusalem—then part of Roman Judea—to a father of priestly d ...

however, notes that the execution of James happened while the newly appointed governor Lucceius Albinus "was but upon the road" to assume his office. Also Acts relates that the stoning happened in a lynching-like manner, in the course of Stephen's public criticism of Jews who refused to believe in Jesus.

It has also been suggested that the Gospel accounts may have downplayed the role of the Romans in Jesus' death during a time when Christianity was struggling to gain acceptance among the then pagan or polytheist Roman world. Matthew 27

Matthew 27 is the 27th chapter in the Gospel of Matthew, part of the New Testament in the Christian Bible. This chapter contains Matthew's record of the day of the trial, crucifixion and burial of Jesus. Scottish theologian William Roberts ...

:24–25, quoted above, has no counterpart in the other Gospels and some scholars see it as probably related to the destruction of Jerusalem

The siege of Jerusalem of 70 CE was the decisive event of the First Jewish–Roman War (66–73 CE), in which the Roman army led by future emperor Titus besieged Jerusalem, the center of Jewish rebel resistance in the Roman province of Ju ...

in the year 70 A.D. Ulrich Luz

Ulrich Luz (23 February 1938 – 13 October 2019) was a Swiss theologian and professor emeritus at the University of Bern.

Early life

He was born on 23 February 1938 in Männedorf. He studied Protestant theology in Zurich, Göttingen and Basel u ...

describes it as "redactional fiction" invented by the author of the Gospel of Matthew

The Gospel of Matthew), or simply Matthew. It is most commonly abbreviated as "Matt." is the first book of the New Testament of the Bible and one of the three synoptic Gospels. It tells how Israel's Messiah, Jesus, comes to his people and ...

. Some writers, viewing it as part of Matthew's anti-Jewish polemic, see in it the seeds of later Christian antisemitism.

In his 2011 book, Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereign ...

, besides repudiating placing blame on the Jewish people, interprets the passage found in the Gospel of Matthew which has the crowd saying "Let his blood be upon us and upon our children" as not referring to the whole Jewish people.

Historicity of Barabbas

Some biblical scholars, including Benjamin Urrutia andHyam Maccoby

Hyam Maccoby ( he, חיים מכובי, 1924–2004) was a Jewish- British scholar and dramatist specialising in the study of the Jewish and Christian religious traditions. He was known for his theories of the historical Jesus and the origins of ...

, go a step further by not only doubting the historicity of the blood curse

The term "blood curse" refers to a New Testament passage from the Gospel of Matthew, which describes events taking place in Pilate's court before the crucifixion of Jesus and specifically the apparent willingness of the Jewish crowd to accep ...

statement in Matthew but also the existence of Barabbas

Barabbas (; ) was, according to the New Testament, a prisoner who was chosen over Jesus by the crowd in Jerusalem to be pardoned and released by Roman governor Pontius Pilate at the Passover feast.

Biblical account

According to all four canoni ...

. This theory is based on the fact that Barabbas's full name was given in early writings as Jesus Barabbas, meaning literally Jesus, son of the father. The theory is that this name originally referred to Jesus himself, and that when the crowd asked Pilate to release "Jesus, son of the father" they were referring to Jesus himself, as suggested also by Peter Cresswell. The theory suggests that further details around Barabbas are historical fiction based on a misunderstanding. The theory is disputed by other scholars.

Paul's First Letter to the Thessalonians

TheFirst Epistle to the Thessalonians

The First Epistle to the Thessalonians is a Pauline epistle of the New Testament of the Christian Bible. The epistle is attributed to Paul the Apostle, and is addressed to the church in Thessalonica, in modern-day Greece. It is likely among ...

also contains accusations of Jewish deicide:

According to Jeremy Cohen:

2nd century

The identification of the death of Jesus as the killing of God is first stated in "God is murdered" as early as 167 AD, in a tract bearing the title '' Peri Pascha'' that may have been designed to bolster a minor Christian sect's presence inSardis

Sardis () or Sardes (; Lydian: 𐤳𐤱𐤠𐤭𐤣 ''Sfard''; el, Σάρδεις ''Sardeis''; peo, Sparda; hbo, ספרד ''Sfarad'') was an ancient city at the location of modern ''Sart'' (Sartmahmut before 19 October 2005), near Salihli, ...

, where Jews had a thriving community with excellent relations with Greeks, and which is attributed to a Quartodeciman

Quartodecimanism (from the Vulgate Latin ''quarta decima'' in Leviticus 23:5, meaning fourteenth) is the practice of celebrating Easter on the 14th of Nisan being on whatever day of the week, practicing Easter around the same time as the Passove ...

, Melito of Sardis

Melito of Sardis ( el, Μελίτων Σάρδεων ''Melítōn Sárdeōn''; died ) was the bishop of Sardis near Smyrna in western Anatolia, and a great authority in early Christianity. Melito held a foremost place in terms of bishops in Asia ...

, a statement is made that appears to have transformed the charge that Jews had killed their own Messiah into the charge that the Jews had killed God himself.

If so, the author would be the first writer in the Lukan-Pauline tradition to raise unambiguously the accusation of deicide against Jews.Abel Mordechai Bibliowicz''Jews and Gentiles in the Early Jesus Movement: An Unintended Journey''

Palgrave Macmillan, 2013 pp. 180–182. This text blames the Jews for allowing King Herod and

Caiaphas

Joseph ben Caiaphas (; c. 14 BC – c. 46 AD), known simply as Caiaphas (; grc-x-koine, Καϊάφας, Kaïáphas ) in the New Testament, was the Jewish high priest who, according to the gospels, organized a plot to kill Jesus. He famousl ...

to execute Jesus, despite their calling as God's people (i.e., both were Jewish). It says "you did not know, O Israel, that this one was the firstborn of God". The author does not attribute particular blame to Pontius Pilate, but only mentions that Pilate washed his hands of guilt.

4th century

John Chrysostom

John Chrysostom (; gr, Ἰωάννης ὁ Χρυσόστομος; 14 September 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople. He is known for his preaching and public speaking, his denunciation of a ...

(c. 347 – 407) was an important Early Church Father who served as archbishop of Constantinople

The ecumenical patriarch ( el, Οἰκουμενικός Πατριάρχης, translit=Oikoumenikós Patriárchēs) is the archbishop of Constantinople (Istanbul), New Rome and ''primus inter pares'' (first among equals) among the heads of the ...

and is known for his fanatical antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

, collected in his homilies, such as ''Adversus Judaeos

''Adversus Judaeos'' ( grc, Κατὰ Ἰουδαίων ''Kata Ioudaiōn'', "against the Jews") are a series of fourth century homilies by Saint John Chrysostom directed to members of the church of Antioch of his time, who continued to observe Je ...

''. The charge of Jewish deicide was the cornerstone of his theology, and he was the first to use the term ''deicide'' and the first Christian preacher to apply the word ''deicide'' to Jews collectively. He held that for this putative 'deicide', there was no expiation, pardon or indulgence possible. The first occurrence of the Latin word ''deicida'' occurs in a Latin sermon by Peter Chrysologus (c. 380 – c. 450). In the Latin version he wrote: ''Iudaeos nvidia

Nvidia CorporationOfficially written as NVIDIA and stylized in its logo as VIDIA with the lowercase "n" the same height as the uppercase "VIDIA"; formerly stylized as VIDIA with a large italicized lowercase "n" on products from the mid 1990s to ...

... fecit esse deicidas'', i.e., " nvymade the Jews deicides".

Recent discussions

The accuracy of theGospel

Gospel originally meant the Christian message (" the gospel"), but in the 2nd century it came to be used also for the books in which the message was set out. In this sense a gospel can be defined as a loose-knit, episodic narrative of the words a ...

accounts' portrayal of Jewish complicity in Jesus' death has been vigorously debated in recent decades, with views which range from a denial of Jewish responsibility to a belief in extensive Jewish culpability. According to the Jesuit scholar Daniel Harrington, the consensus of Jewish and Christian scholars is that there is some Jewish responsibility, regarding not the Jewish people, but regarding only the probable involvement of the high priests in Jerusalem at the time and their allies. Many scholars read the story of the passion as an attempt to take the blame off Pilate and place it on the Jews, one which might have been at the time politically motivated. It is thought possible that Pilate ordered the crucifixion to avoid a riot, for example. Some scholars hold that the synoptic account is compatible with traditions in the Babylonian Talmud

The Talmud (; he, , Talmūḏ) is the central text of Rabbinic Judaism and the primary source of Jewish religious law ('' halakha'') and Jewish theology. Until the advent of modernity, in nearly all Jewish communities, the Talmud was the cen ...

. The writings of Moses Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

(a medieval Sephardic Jewish

Sephardic (or Sephardi) Jews (, ; lad, Djudíos Sefardíes), also ''Sepharadim'' , Modern Hebrew: ''Sfaradim'', Tiberian: Səp̄āraddîm, also , ''Ye'hude Sepharad'', lit. "The Jews of Spain", es, Judíos sefardíes (or ), pt, Judeus sefa ...

philosopher) mentioned the hanging of a certain Jesus (identified in the sources as Yashu'a) on the eve of Passover. Maimonides considered Jesus as a Jewish renegade in revolt against Judaism; religion commanded the death of Jesus and his students; and Christianity was a religion attached to his name in a later period. In a passage widely censored in pre-modern editions for fear of the way it might feed into very real antisemitic attitudes, Maimonides wrote of "Jesus of Nazareth, who imagined that he was the Messiah, and was put to death by the court" (that is, "by a ''beth din

A beit din ( he, בית דין, Bet Din, house of judgment, , Ashkenazic: ''beis din'', plural: batei din) is a rabbinical court of Judaism. In ancient times, it was the building block of the legal system in the Biblical Land of Israel. Today, i ...

''") Maimonides position was defended in modern times by rabbi Zvi Yehuda Kook

Zvi Yehuda Kook ( he, צבי יהודה קוק, 23 April 1891 – 9 March 1982) was a prominent ultranationalist Orthodox rabbi. He was the son of Rabbi Avraham Yitzhak Hacohen Kook, the first Ashkenazi chief rabbi of British Mandatory Pales ...

, who asserted Jewish responsibility and dismissed those who denied it as sycophants.

Liturgy

Eastern Christianity

TheHoly Friday

Good Friday is a Christian holiday commemorating the crucifixion of Jesus and his death at Calvary. It is observed during Holy Week as part of the Paschal Triduum. It is also known as Holy Friday, Great Friday, Great and Holy Friday (also Holy ...

liturgy of the Eastern Orthodox Church

The Eastern Orthodox Church, also called the Orthodox Church, is the second-largest Christian church, with approximately 220 million baptized members. It operates as a communion of autocephalous churches, each governed by its bishops vi ...

, as well as the Byzantine Rite Catholic churches, uses the expression "impious and transgressing people", but the strongest expressions are in the Holy Thursday

Maundy Thursday or Holy Thursday (also known as Great and Holy Thursday, Holy and Great Thursday, Covenant Thursday, Sheer Thursday, and Thursday of Mysteries, among other names) is the day during Holy Week that commemorates the Washing of the ...

liturgy, which includes the same chant, after the eleventh Gospel reading, but also speaks of "the murderers of God, the lawless nation of the Jews", and, referring to "the assembly of the Jews", prays: "But give them, Lord, their reward, because they devised vain things against Thee."

Western Christianity

A liturgy with a similar pattern but with no specific mention of the Jews is found in the Improperia of theRoman Rite

The Roman Rite ( la, Ritus Romanus) is the primary liturgical rite of the Latin Church, the largest of the '' sui iuris'' particular churches that comprise the Catholic Church. It developed in the Latin language in the city of Rome and, while d ...

of the Catholic Church. A collect for the Jews is also said, traditionally calling for the conversion of the "faithless" and "blind" Jews, although this wording was removed after the Vatican II council. It had sometimes been thought, perhaps incorrectly, that "faithless" (in Latin, ''perfidis''), meant "perfidious", i.e. treacherous.

In the Anglican Church

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of t ...

, the 1662 ''Book of Common Prayer

The ''Book of Common Prayer'' (BCP) is the name given to a number of related prayer books used in the Anglican Communion and by other Christianity, Christian churches historically related to Anglicanism. The original book, published in 1549 ...

'' contains a similar collect for "Jews, Turks, Infidels, and Hereticks" for use on Good Friday, though it does not allude to any responsibility for the death of Jesus. Versions of the Improperia also appear in later versions, such as the 1989 Anglican ''Prayer Book'' of the Anglican Church of Southern Africa

The Anglican Church of Southern Africa, known until 2006 as the Church of the Province of Southern Africa, is the province (Anglican), province of the Anglican Communion in the southern part of Africa. The church has twenty-five dioceses, of whi ...

, commonly called ''The Solemn Adoration of Christ Crucified'' or ''The Reproaches''. Although not part of Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words '' Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρ ...

dogma

Dogma is a belief or set of beliefs that is accepted by the members of a group without being questioned or doubted. It may be in the form of an official system of principles or doctrines of a religion, such as Roman Catholicism, Judaism, Islam ...

, many Christians, including members of the clergy

Clergy are formal leaders within established religions. Their roles and functions vary in different religious traditions, but usually involve presiding over specific rituals and teaching their religion's doctrines and practices. Some of the t ...

, preached that the Jewish people were collectively guilty for Jesus' death.

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, informally known as the LDS Church or Mormon Church, is a nontrinitarian Christian church that considers itself to be the restoration of the original church founded by Jesus Christ. The ...

(LDS) accepts additional scriptures about Jewish deicide. The Book of Mormon

The Book of Mormon is a religious text of the Latter Day Saint movement, which, according to Latter Day Saint theology, contains writings of ancient prophets who lived on the American continent from 600 BC to AD 421 and during an interlude ...

teaches that Jesus came to the Jews because they were the only nation which was wicked enough to crucify him. It also teaches that the Jewish people were punished with death and destruction because of their wickedness. It teaches that God gave the gentiles the power to scatter the Jews and it connects their future gathering to their belief that Jesus is the Christ. According to the Doctrine & Covenants, after Jesus reveals himself to the Jews, they will weep because of their iniquities. It warns that if the Jewish people do not repent, the world will be destroyed.

Brigham Young

Brigham Young (; June 1, 1801August 29, 1877) was an American religious leader and politician. He was the second President of the Church (LDS Church), president of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church), from 1847 until his ...

, an early LDS prophet, taught the belief that the Jewish people were in a middle-tier of cursed lineages, below Lamanites

The Lamanites () are one of the four ancient peoples (along with the Jaredites, the Mulekites, and the Nephites) described as having settled in the ancient Americas in the Book of Mormon, a sacred text of the Latter Day Saint movement. The Laman ...

( Native Americans) but above Cain

Cain ''Káïn''; ar, قابيل/قايين, Qābīl/Qāyīn is a Biblical figure in the Book of Genesis within Abrahamic religions. He is the elder brother of Abel, and the firstborn son of Adam and Eve, the first couple within the Bible. He w ...

's descendants (Black people

Black is a racialized classification of people, usually a political and skin color-based category for specific populations with a mid to dark brown complexion. Not all people considered "black" have dark skin; in certain countries, often ...

), because they had crucified Jesus and the gathering in Jerusalem would be part of their penance for it. As part of the curse, they would not receive the gospel and if anyone converted to the church it would be proof that they were not actually Jewish. As more Jews began to assimilate into Northern America and Western Europe, church leaders began to soften their stance, saying instead that Lord was gradually withdrawing the curse and the Jews were beginning to believe in Christ, but that it wouldn't fully happen until Jesus returned. The Holocaust and the threats of Nazism were seen as fulfillment of prophecy that the Jews would be punished. Likewise, the establishment of Israel and the influx of Jewish people were seen as fulfillment of prophecy that they Jewish people would be gathered and the curse lifted.

In 1978, the LDS Church began to give the priesthood to all males regardless of race and it also began to de-emphasize the importance of race, instead, it adopted a more universal emphasis. This has led to a spectrum of views on how LDS members interpret scripture and previous teachings. According to research by Armand Mauss, most LDS members believe that God is perpetually punishing Jews for their part in the crucifixion of Jesus Christ and they will not be forgiven until they are converted. These views were correlated with Christian hostility towards the Jews. However, these hostile views were often counter-balanced with views that they share a common ancestry with the Jews.

Some Latter-Day Saints may argue against the idea that their scriptures promote Jewish Deicide, citing the Second Article of Faith as evidence against the idea of all Jews being punished for Jesus' crucifixion. The Second Article of Faith (contained in The Pearl of Great Price) states that "We believe that men will be punished for their own sins, and not for Adam’s transgression".

Repudiation

In the aftermath ofWorld War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

and The Holocaust

The Holocaust, also known as the Shoah, was the genocide of European Jews during World War II. Between 1941 and 1945, Nazi Germany and its collaborators systematically murdered some six million Jews across German-occupied Europe; ...

, Jules Isaac Jules Isaac (18 November 1877 in Rennes – 6 September 1963 in Aix-en-Provence) was "a well known and highly respected Jewish historian in France with an impressive career in the world of education" by the time World War II began.

Internationally, ...

, a French-Jewish historian and a Holocaust survivor

Holocaust survivors are people who survived the Holocaust, defined as the persecution and attempted annihilation of the Jews by Nazi Germany and its allies before and during World War II in Europe and North Africa. There is no universally accep ...

, played a seminal role in documenting the antisemitic traditions which existed in the Catholic Church's thinking, instruction and liturgy. The move to draw up a formal document of repudiation gained momentum after Isaac obtained a private audience with Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Roman Catholic Church, Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City, Vatican City State from 28 Oc ...

in 1960. In the Second Vatican Council

The Second Ecumenical Council of the Vatican, commonly known as the , or , was the 21st Catholic ecumenical councils, ecumenical council of the Roman Catholic Church. The council met in St. Peter's Basilica in Rome for four periods (or sessions) ...

(1962–1965), the Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

under Pope Paul VI

Pope Paul VI ( la, Paulus VI; it, Paolo VI; born Giovanni Battista Enrico Antonio Maria Montini, ; 26 September 18976 August 1978) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 21 June 1963 to his death in Augus ...

issued the declaration ''Nostra aetate

(from Latin: "In our time") is the incipit of the Declaration on the Relation of the Church with Non-Christian Religions of the Second Vatican Council. Passed by a vote of 2,221 to 88 of the assembled bishops, this declaration was promulgated o ...

'' ("In Our Time"), which among other things repudiated belief in the collective Jewish guilt for the crucifixion of Jesus

The crucifixion and death of Jesus occurred in 1st-century Judea, most likely in AD 30 or AD 33. It is described in the four canonical gospels, referred to in the New Testament epistles, attested to by other ancient sources, and conside ...

. ''Nostra aetate'' stated that, even though some Jewish authorities and those who followed them called for Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

' death, the blame for what happened cannot be laid at the door of all Jews living at that time, nor can the Jews in our time be held guilty. It made no explicit mention of Matthew 27:24–25, but only of .

On November 16, 1998, the Church Council of the Evangelical Lutheran Church in America

The Evangelical Lutheran Church in America (ELCA) is a mainline Protestant Lutheran church headquartered in Chicago, Illinois. The ELCA was officially formed on January 1, 1988, by the merging of three Lutheran church bodies. , it has approxi ...

adopted a resolution which was prepared by its Consultative Panel on Lutheran-Jewish Relations. The resolution urged that any Lutheran church which was presenting a Passion play should adhere to its ''Guidelines for Lutheran-Jewish Relations'', stating that "the New Testament ... must not be used as a justification for hostility towards present-day Jews", and it also stated that "blame for the death of Jesus should not be attributed to Judaism

Judaism ( he, ''Yahăḏūṯ'') is an Abrahamic, monotheistic, and ethnic religion comprising the collective religious, cultural, and legal tradition and civilization of the Jewish people. It has its roots as an organized religion in the ...

or the Jewish people."

Pope Benedict XVI

Pope Benedict XVI ( la, Benedictus XVI; it, Benedetto XVI; german: link=no, Benedikt XVI.; born Joseph Aloisius Ratzinger, , on 16 April 1927) is a retired prelate of the Catholic church who served as the head of the Church and the sovereig ...

also repudiated the Jewish deicide charge in his 2011 book ''Jesus of Nazareth

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

'', in which he interpreted the translation of "''ochlos''" in Matthew to mean the "crowd", rather than the Jewish people

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

.

See also

*Anti-Judaism

Anti-Judaism is the "total or partial opposition to Judaism as a religion—and the total or partial opposition to Jews as adherents of it—by persons who accept a competing system of beliefs and practices and consider certain genuine Judai ...

* Antisemitism and the New Testament

* Antisemitism in Christianity

* Catholic Church and Judaism

* Antisemitic trope

* Christianity and Judaism

Christianity began as a movement within Second Temple Judaism, but the two religions gradually Split of early Christianity and Judaism, diverged over the first few centuries of the Christian Era. Differences of opinion vary between denominations ...

* Christian–Jewish reconciliation

Christian−Jewish reconciliation refers to the efforts that are being made to improve understanding and acceptance between Christians and Jews. There has been significant progress in reconciliation in recent years, in particular by the Catholic C ...

* Criticism of Christianity

Criticism of Christianity has a long history which stretches back to the initial formation of the religion during the Roman Empire. Critics have challenged Christian beliefs and teachings as well as Christian actions, from the Crusades to mod ...

* Criticism of Judaism

Criticism of Judaism refers to criticism of Jewish religious doctrines, texts, laws, and practices. Early criticism originated in inter-faith polemics between Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on th ...

* Faithful Word Baptist Church

* Jewish views on religious pluralism

* Judaism and Mormonism

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS Church) has several unique teachings about Judaism and the House of Israel. The largest denomination in the Latter Day Saint movement, the LDS Church, teaches the belief that the Jewish people ...

* Judaism's view of Jesus

There is no specific doctrinal view of Jesus in traditional Judaism. Monotheism, a belief in the absolute unity and singularity of God, is central to Judaism, which regards the worship of a person as a form of idolatry. Therefore, considering J ...

* '' Moses and Monotheism'' by Sigmund Freud

Sigmund Freud ( , ; born Sigismund Schlomo Freud; 6 May 1856 – 23 September 1939) was an Austrian neurologist and the founder of psychoanalysis, a clinical method for evaluating and treating psychopathology, pathologies explained as originatin ...

* Protestantism and Judaism Relations between Protestantism and Judaism have existed since the time of the Reformation, although there has been more emphasis on dialogue since the 20th century, with Protestant and Jewish scholars in the United States being at the forefront of ...

* Relations between Eastern Orthodoxy and Judaism

The Eastern Orthodox Church and Rabbinic Judaism are thought to have had better relations historically than Judaism and either Catholic or Protestant Christianity.

Patriarchal statement

An Orthodox Christian attitude to the Jewish people is ...

* Religious antisemitism

Religious antisemitism is aversion to or discrimination against Jews as a whole, based on religious doctrines of supersession that expect or demand the disappearance of Judaism and the conversion of Jews, and which figure their political enem ...

* Religious perspectives on Jesus

* Romany crucifixion legend

* Stereotypes of Jews

* Westboro Baptist Church

The Westboro Baptist Church (WBC) is a small American, unaffiliated Primitive Baptist church in Topeka, Kansas, founded in 1955 by pastor Fred Phelps. Labeled a hate group, WBC is known for engaging in homophobic and anti-American pickets, ...

References

External links

* {{Antisemitism footer, state=expanded Antisemitic canards Caiaphas Christian anti-Judaism Christianity and antisemitism Death of deities Antisemitic slurs Pontius Pilate Barabbas