Japanese Secret Service on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The , also known as Kempeitai, was the

The Kenpeitai was established in 1881 by a decree called the , figuratively "articles concerning gendarmes". Its model was the

The Kenpeitai was established in 1881 by a decree called the , figuratively "articles concerning gendarmes". Its model was the

The Kenpeitai was responsible for the following:

* Travel permits

* Labor recruitment

*

The Kenpeitai was responsible for the following:

* Travel permits

* Labor recruitment

*

Japanese World War II-era nationalist groups

{{Authority control Imperial Japanese Army Political repression in Japan Defunct Japanese intelligence agencies Defunct law enforcement agencies of Japan

military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. In wartime operations, the military police may support the main fighting force with force protection, convoy security, screening, rear recon ...

arm of the Imperial Japanese Army

The was the official ground-based armed force of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945. It was controlled by the Imperial Japanese Army General Staff Office and the Ministry of the Army, both of which were nominally subordinate to the Emperor o ...

from 1881 to 1945 that also served as a secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

force. In addition, in Japanese-occupied territories, the Kenpeitai arrested or killed those suspected of being anti-Japanese. While institutionally part of the army, the Kenpeitai also discharged military police functions for the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

under the direction of the Admiralty Minister (although the IJN had its own much smaller Tokkeitai), those of the executive police under the direction of the Home Minister

The Minister of Home Affairs (or simply, the Home Minister, short-form HM) is the head of the Ministry of Home Affairs of the Government of India. One of the senior-most officers in the Union Cabinet, the chief responsibility of the Home Minist ...

and those of the judicial police

The judicial police, judiciary police, or justice police are (depending on both country and legal system) either a branch, separate police agency or type of duty performed by law enforcement structures in a country. The term judiciary police is mo ...

under the direction of the Justice Minister

A justice ministry, ministry of justice, or department of justice is a ministry or other government agency in charge of the administration of justice. The ministry or department is often headed by a minister of justice (minister for justice in a v ...

. A member of the Kenpeitai corps was called a ''kenpei'' (憲兵).

History

The Kenpeitai was established in 1881 by a decree called the , figuratively "articles concerning gendarmes". Its model was the

The Kenpeitai was established in 1881 by a decree called the , figuratively "articles concerning gendarmes". Its model was the National Gendarmerie

The National Gendarmerie (french: Gendarmerie nationale, ) is one of two national law enforcement forces of France, along with the National Police. The Gendarmerie is a branch of the French Armed Forces placed under the jurisdiction of the Minis ...

of France. Details of the Kenpeitai's military, executive, and judicial police functions were defined by the ''Kenpei Rei'' of 1898, which was amended twenty-six times before Japan's defeat in August 1945.

The force initially consisted of 349 men. At the beginning, enforcement of new conscription

Conscription (also called the draft in the United States) is the state-mandated enlistment of people in a national service, mainly a military service. Conscription dates back to antiquity and it continues in some countries to the present day un ...

legislation was an important part of their duty, largely due to resistance from peasant

A peasant is a pre-industrial agricultural laborer or a farmer with limited land-ownership, especially one living in the Middle Ages under feudalism and paying rent, tax, fees, or services to a landlord. In Europe, three classes of peasants ...

families. In 1907, the Kenpeitai was ordered to Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, where its main duty was legally defined as "preserving the peace", although it also functioned as a military police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. In wartime operations, the military police may support the main fighting force with force protection, convoy security, screening, rear recon ...

for the Japanese Army stationed there. Its status remained basically unchanged after Japan's annexation of Korea in 1910.

The Kenpeitai maintained public order within Japan under the direction of the Interior Minister, and in the occupied territories under the direction of the Minister of War

A defence minister or minister of defence is a cabinet official position in charge of a ministry of defense, which regulates the armed forces in sovereign states. The role of a defence minister varies considerably from country to country; in som ...

. Japan also had a civilian secret police force, ''Tokkō'', which was the Japanese acronym of ''Tokubetsu Kōtō Keisatsu

The , often abbreviated , was a Japanese policing organization, established within the Home Ministry in 1911, for the purpose of carrying out high policing, domestic criminal investigations, and control of political groups and ideologies deemed ...

'' ("Special Higher Police", also known by various nicknames such as the Peace Police and as the Thought Police) that was part of the Interior Ministry. However, the Kenpeitai had a ''Tokkō'' branch of its own, and through it discharged the functions of a secret police

Secret police (or political police) are intelligence, security or police agencies that engage in covert operations against a government's political, religious, or social opponents and dissidents. Secret police organizations are characteristic of a ...

.

When the Kenpeitai arrested a civilian under the direction of the Justice Minister, the arrested person was nominally subject to civilian judicial proceedings.

The Kenpeitai's brutality was particularly notorious in Korea and the other occupied territories. The Kenpeitai were also abhorred on the Japanese mainland, especially during World War II when Prime Minister

A prime minister, premier or chief of cabinet is the head of the cabinet and the leader of the ministers in the executive branch of government, often in a parliamentary or semi-presidential system. Under those systems, a prime minister is not ...

Hideki Tojo

Hideki Tojo (, ', December 30, 1884 – December 23, 1948) was a Japanese politician, general of the Imperial Japanese Army (IJA), and convicted war criminal who served as prime minister of Japan and president of the Imperial Rule Assistan ...

, formerly the Kenpeitai Commander of the Japanese Army

The Japan Ground Self-Defense Force ( ja, 陸上自衛隊, Rikujō Jieitai), , also referred to as the Japanese Army, is the land warfare branch of the Japan Self-Defense Forces. Created on July 1, 1954, it is the largest of the three service b ...

in Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

from 1935 to 1937, used the Kenpeitai extensively to ensure everyone's loyalty and commitment to the war effort.

According to the US Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

'' Handbook on Japanese Military Forces'', there were over 36,000 regular Kenpeitai members and numerous ethnic "auxiliaries

Auxiliaries are support personnel that assist the military or police but are organised differently from regular forces. Auxiliary may be military volunteers undertaking support functions or performing certain duties such as garrison troops, u ...

" at the end of the war. As foreign territories fell under Japanese military occupation during the 1930s and the early 1940s, the Kenpeitai recruited large numbers of locals in those territories. Taiwanese and Koreans were extensively used as auxiliaries to police the newly occupied territories in Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical United Nations geoscheme for Asia#South-eastern Asia, south-eastern region of Asia, consistin ...

, although the Kenpeitai also carried out recruitment activity among peoples native to French Indochina

French Indochina (previously spelled as French Indo-China),; vi, Đông Dương thuộc Pháp, , lit. 'East Ocean under French Control; km, ឥណ្ឌូចិនបារាំង, ; th, อินโดจีนฝรั่งเศส, ...

(especially from Vietnamese members of the Cao Dai

Caodaism ( vi, Đạo Cao Đài, Chữ Hán: ) is a monotheistic syncretic new religious movement officially established in the city of Tây Ninh in southern Vietnam in 1926. The full name of the religion is (The Great Faith or theThird Univ ...

religious sect), Malaya

Malaya refers to a number of historical and current political entities related to what is currently Peninsular Malaysia in Southeast Asia:

Political entities

* British Malaya (1826–1957), a loose collection of the British colony of the Straits ...

, and other territories. The Kenpeitai may have trained Trình Minh Thế

Trình Minh Thế (1920 – 3 May 1955) was a Vietnamese nationalist and Cao Dai military leader during the end of the First Indochina War and the beginning of the Vietnam War.

Early life

Thế was born in Tây Ninh Province and raised in the ...

, a Vietnam

Vietnam or Viet Nam ( vi, Việt Nam, ), officially the Socialist Republic of Vietnam,., group="n" is a country in Southeast Asia, at the eastern edge of mainland Southeast Asia, with an area of and population of 96 million, making i ...

ese nationalist and anti-Viet Minh

The Việt Minh (; abbreviated from , chữ Nôm and Hán tự: ; french: Ligue pour l'indépendance du Viêt Nam, ) was a national independence coalition formed at Pác Bó by Hồ Chí Minh on 19 May 1941. Also known as the Việt Minh Fro ...

military

A military, also known collectively as armed forces, is a heavily armed, highly organized force primarily intended for warfare. It is typically authorized and maintained by a sovereign state, with its members identifiable by their distinct ...

leader.

The Kenpeitai was disarmed and disbanded after the Japanese surrender

The surrender of the Empire of Japan in World War II was announced by Emperor Hirohito on 15 August and formally signed on 2 September 1945, bringing the war's hostilities to a close. By the end of July 1945, the Imperial Japanese Navy ...

in August 1945.

Today, the post-war Self-Defense Forces' internal police is called ''Keimutai'' (警務隊). Each individual member is called ''Keimukan''. Modelled on the military Police

Military police (MP) are law enforcement agencies connected with, or part of, the military of a state. In wartime operations, the military police may support the main fighting force with force protection, convoy security, screening, rear recon ...

in the United States and other Western armed forces, the SDF internal police has no jurisdiction over civilians.

Intra-Axis co-operation

In the 1920s and the 1930s the Kenpeitai forged various connections with certain pre-war Europeanintelligence services

An intelligence agency is a government agency responsible for the collection, analysis, and exploitation of information in support of law enforcement, national security

National security, or national defence, is the security and defence of ...

. Later, following the signing of the Tripartite Pact

The Tripartite Pact, also known as the Berlin Pact, was an agreement between Germany, Italy, and Japan signed in Berlin on 27 September 1940 by, respectively, Joachim von Ribbentrop, Galeazzo Ciano and Saburō Kurusu. It was a defensive military ...

in 1940, Japan formed formal links with military intelligence units now under German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

and Italian

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

fascists

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy and th ...

: the German Abwehr

The ''Abwehr'' (German for ''resistance'' or ''defence'', but the word usually means ''counterintelligence'' in a military context; ) was the German military-intelligence service for the ''Reichswehr'' and the ''Wehrmacht'' from 1920 to 1944. A ...

and Italian Servizio Informazioni Militare

The Italian Military Information Service ( it, Servizio Informazioni Militare, or SIM) was the military intelligence organization for the Royal Army (''Regio Esercito'') of the Kingdom of Italy (''Regno d'Italia'') from 1925 until 1946, and of the ...

. The Army and Navy of Japan contacted their counterparts in Wehrmacht

The ''Wehrmacht'' (, ) were the unified armed forces of Nazi Germany from 1935 to 1945. It consisted of the ''Heer'' (army), the ''Kriegsmarine'' (navy) and the ''Luftwaffe'' (air force). The designation "''Wehrmacht''" replaced the previous ...

intelligence, in the Schutzstaffel

The ''Schutzstaffel'' (SS; also stylized as ''ᛋᛋ'' with Armanen runes; ; "Protection Squadron") was a major paramilitary organization under Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party in Nazi Germany, and later throughout German-occupied Europe d ...

(SS) and in Kriegsmarine

The (, ) was the navy of Germany from 1935 to 1945. It superseded the Imperial German Navy of the German Empire (1871–1918) and the inter-war (1919–1935) of the Weimar Republic. The was one of three official branches, along with the a ...

units about information on Europe and ''vice versa''. The Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

fully understood the benefits of such exchanges. For example, the Japanese sent the Germans data about Soviet

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a List of former transcontinental countries#Since 1700, transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, ...

forces in the Far East

The ''Far East'' was a European term to refer to the geographical regions that includes East and Southeast Asia as well as the Russian Far East to a lesser extent. South Asia is sometimes also included for economic and cultural reasons.

The ter ...

and Operation Barbarossa

Operation Barbarossa (german: link=no, Unternehmen Barbarossa; ) was the invasion of the Soviet Union by Nazi Germany and many of its Axis allies, starting on Sunday, 22 June 1941, during the Second World War. The operation, code-named after ...

from their embassy in Berlin. Admiral Canaris

Wilhelm Franz Canaris (1 January 1887 – 9 April 1945) was a German admiral and the chief of the ''Abwehr'' (the German military-intelligence service) from 1935 to 1944. Canaris was initially a supporter of Adolf Hitler, and the Nazi re ...

offered Japan information and assistance on the neutrality of Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

in Timor

Timor is an island at the southern end of Maritime Southeast Asia, in the north of the Timor Sea. The island is East Timor–Indonesia border, divided between the sovereign states of East Timor on the eastern part and Indonesia on the western p ...

.

One important point of contact was the Penang submarine-base in Japanese-occupied Malaya

The then British colony of Malaya was gradually occupied by the Japanese between 8 December 1941 and the Allied surrender at Singapore on 16 February 1942. The Japanese remained in occupation until their surrender to the Allies in 1945. The ...

, which served Axis submarine forces of the Italian Italian Regia Marina, German Kriegsmarine and Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

. At regular intervals, technological and information exchanges occurred at the base. While still available to them, Axis forces used bases in Italian East Africa

Italian East Africa ( it, Africa Orientale Italiana, AOI) was an Italian colony in the Horn of Africa. It was formed in 1936 through the merger of Italian Somalia, Italian Eritrea, and the newly occupied Ethiopian Empire, conquered in the Seco ...

, in the Vichy France

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its ter ...

colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

of Madagascar

Madagascar (; mg, Madagasikara, ), officially the Republic of Madagascar ( mg, Repoblikan'i Madagasikara, links=no, ; french: République de Madagascar), is an island country in the Indian Ocean, approximately off the coast of East Africa ...

and in officially neutral places like Portuguese India

The State of India ( pt, Estado da Índia), also referred as the Portuguese State of India (''Estado Português da Índia'', EPI) or simply Portuguese India (), was a state of the Portuguese Empire founded six years after the discovery of a se ...

.

Human rights abuses

The Kenpeitai ran extensive criminal andcollaborationist

Wartime collaboration is cooperation with the enemy against one's country of citizenship in wartime, and in the words of historian Gerhard Hirschfeld, "is as old as war and the occupation of foreign territory".

The term ''collaborator'' dates to t ...

networks, extorting vast amounts of money from businesses and civilians wherever they operated. They also ran the Japanese prisoner of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of wa ...

system, which treated captives with extreme brutality. Many of the abuses were documented in Japanese war crimes

The Empire of Japan committed war crimes in many Asian-Pacific countries during the period of Japanese militarism, Japanese imperialism, primarily during the Second Sino-Japanese War, Second Sino-Japanese and Pacific Wars. These incidents have b ...

trials, such as those committed by the Kempeitai East District Branch

The Kempeitai East District Branch was the headquarters of the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police, during the Japanese occupation of Singapore from 1942 to 1945. It was located at the old YMCA building, at the present site of Singapore's ...

in Singapore

Singapore (), officially the Republic of Singapore, is a sovereign island country and city-state in maritime Southeast Asia. It lies about one degree of latitude () north of the equator, off the southern tip of the Malay Peninsula, borde ...

, including the Sook Ching

Sook Ching was a mass killing that occurred from 18 February to 4 March 1942 in Singapore after it fell to the Japanese. It was a systematic purge and massacre of 'anti-Japanese' elements in Singapore, with the Singaporean Chinese particularl ...

.

The Kenpeitai also carried out revenge attacks against prisoners and civilians. For example, after Colonel Doolittle's raid on Tokyo in 1942, it carried out reprisals against thousands of Chinese civilians and captured airmen, and in 1943 committed the Double Tenth massacre in response to an Allied raid on Singapore Harbour. The Kenpeitai also supplied 600 men, women and children per year to the infamous Unit 731

, short for Manshu Detachment 731 and also known as the Kamo Detachment and Ishii Unit, was a covert biological and chemical warfare research and development unit of the Imperial Japanese Army that engaged in lethal human experimentatio ...

, which conducted human experimentation.

Organization

The Kenpeitai was divided into three branches: the Keimu Han (police and security), Naikin Han (Administration), and Tokumu Han (Special Duties). The Kenpeitai's General Affairs Branch was in charge of the force's policy, personnel management, internal discipline, as well as communication with the Ministries of the Admiralty, Interior, and Justice. The Operations Branch was in charge of the distribution of military police units within the army, general public security, and intelligence. The Kenpeitai maintained a headquarters in each relevant Area Army, commanded by a Shosho (Major General

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

), with a Taisa (Colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

) as Executive Officer

An executive officer is a person who is principally responsible for leading all or part of an organization, although the exact nature of the role varies depending on the organization. In many militaries and police forces, an executive officer, o ...

. The headquarters comprised two or three field offices, each staffed with approximately 375 personnel and commanded by a Chusa (Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

), with a Shosa (Major

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

) as Executive Officer. The field offices in turn were divided into 65-man sections called 'buntai', each commanded by a Tai-i (Captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

), with a Chu-i (First Lieutenant

First lieutenant is a commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces; in some forces, it is an appointment.

The rank of lieutenant has different meanings in different military formations, but in most forces it is sub-divided into a s ...

) as Executive Officer. The buntai were further divided into 20-man detachments called ''bunkentai'', commanded by a Sho-i (Second Lieutenant

Second lieutenant is a junior commissioned officer military rank in many armed forces, comparable to NATO OF-1 rank.

Australia

The rank of second lieutenant existed in the military forces of the Australian colonies and Australian Army until ...

), with a Junshikan (Warrant Officer

Warrant officer (WO) is a rank or category of ranks in the armed forces of many countries. Depending on the country, service, or historical context, warrant officers are sometimes classified as the most junior of the commissioned ranks, the mos ...

) as Executive Officer. Keeping with the main organizational structure of the Kenpeitai, each of these detachments contained a police and security squad, an administration squad, and a special duties squad.

Kenpeitai Auxiliary units consisting of regional ethnic forces were organized in occupied areas. These troops supplemented the Kenpeitai and were considered part of the organization, but were limited to the rank of Socho (Sergeant Major

Sergeant major is a senior non-commissioned rank or appointment in many militaries around the world.

History

In 16th century Spain, the ("sergeant major") was a general officer. He commanded an army's infantry, and ranked about third in the ...

).

By 1937, the Kenpeitai had 315 officer

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

s and 6,000 enlisted personnel

An enlisted rank (also known as an enlisted grade or enlisted rate) is, in some armed services, any rank below that of a commissioned officer. The term can be inclusive of non-commissioned officers or warrant officers, except in United States m ...

as part of its official forces. The Allies estimated there were at least 7,500 Kenpeitai members by the end of World War II.

Active units

The Kenpeitai operated commands on the Japanese mainland and throughout all occupied and captured overseas territories during thePacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

. The external units operating outside Japan were:

* First Field Kenpeitai – commanded by Major-General Kōichi Ōno from August 1941 to 23 January 1942 and probably based in China with the Japanese Kwantung Army

''Kantō-gun''

, image = Kwantung Army Headquarters.JPG

, image_size = 300px

, caption = Kwantung Army headquarters in Hsinking, Manchukuo

, dates = April ...

* Second Field Kenpeitai – attached to the 25th Army and based in Singapore from 1942, the unit was under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Oishi Masayuki Oishi may refer to:

* Ōishi (surname), a Japanese surname

* Oishi (Philippine brand), a snack company from the Philippines

* Oishi Group, a Thai food-and-drink company

* Ōishi Station

is a railway station on the Hanshin Electric Railway Main ...

. In January 1944, Malaya came under the responsibility of Third Field Kempeitai Major-General Masanori Kojima

Masanori is a masculine Japanese given name.

Kanji and meaning

The name Masanori is generally written with two kanji, the first read and the second read , for example:

*Starting with ("correct"):

**: second kanji means "rule" or "regulation". ...

.

* Third Field Kenpeitai – drawn from a Manchurian Kenpei Training Regiment in July 1941, attached to the 16th Army and based in Java

Java (; id, Jawa, ; jv, ꦗꦮ; su, ) is one of the Greater Sunda Islands in Indonesia. It is bordered by the Indian Ocean to the south and the Java Sea to the north. With a population of 151.6 million people, Java is the world's List ...

and Sumatra

Sumatra is one of the Sunda Islands of western Indonesia. It is the largest island that is fully within Indonesian territory, as well as the sixth-largest island in the world at 473,481 km2 (182,812 mi.2), not including adjacent i ...

from 1942. The unit headquarters were in Batavia

Batavia may refer to:

Historical places

* Batavia (region), a land inhabited by the Batavian people during the Roman Empire, today part of the Netherlands

* Batavia, Dutch East Indies, present-day Jakarta, the former capital of the Dutch East In ...

under the command of Lieutenant-Colonel Kuzumi Kenzaburo. By war's end, the unit had 772 members.

* Fourth Field Kenpeitai

* Fifth Field Kenpeitai

* Sixth Field Kenpeitai – attached to the 8th Area Army

The was a field army of the Imperial Japanese Army during World War II.

History

The Japanese 8th Area Army was formed on November 16, 1942 under the Southern Expeditionary Army Group for the specific task of opposing landings by Allied forces i ...

based at Rabaul

Rabaul () is a township in the East New Britain province of Papua New Guinea, on the island of New Britain. It lies about 600 kilometres to the east of the island of New Guinea. Rabaul was the provincial capital and most important settlement in ...

, Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

* Seventh Field Kenpeitai

* Eighth Field Kenpeitai – attached to the 2nd Army on Halmahera

Halmahera, formerly known as Jilolo, Gilolo, or Jailolo, is the largest island in the Maluku Islands. It is part of the North Maluku province of Indonesia, and Sofifi, the capital of the province, is located on the west coast of the island.

Hal ...

, Indonesia

Indonesia, officially the Republic of Indonesia, is a country in Southeast Asia and Oceania between the Indian and Pacific oceans. It consists of over 17,000 islands, including Sumatra, Java, Sulawesi, and parts of Borneo and New Guine ...

* Ninth Field Kenpeitai

* Tenth Field Kenpeitai

* Eleventh Field Kenpeitai – commanded by Colonel Shōshichi Kamisago from November 1941 to August 1942, when he became head of the 1st Army First Army may refer to:

China

* New 1st Army, Republic of China

* First Field Army, a Communist Party of China unit in the Chinese Civil War

* 1st Group Army, People's Republic of China

Germany

* 1st Army (German Empire), a World War I field Army ...

Kenpeitai Southern Section

Wartime missions

Counterintelligence

Counterintelligence is an activity aimed at protecting an agency's intelligence program from an opposition's intelligence service. It includes gathering information and conducting activities to prevent espionage, sabotage, assassinations or ot ...

and counterpropaganda Counterpropaganda is a form of communication consisting of methods taken and messages relayed to oppose propaganda which seeks to influence action or perspectives among a targeted audience. It is closely connected to propaganda as the two often empl ...

(run by the '' Tokko''-Kenpeitai as 'anti-ideological work')

* Supply requisitioning and rationing

Rationing is the controlled distribution of scarce resources, goods, services, or an artificial restriction of demand. Rationing controls the size of the ration, which is one's allowed portion of the resources being distributed on a particular ...

* Psychological operations

Psychological warfare (PSYWAR), or the basic aspects of modern psychological operations (PsyOp), have been known by many other names or terms, including Military Information Support Operations (MISO), Psy Ops, political warfare, "Hearts and Mi ...

and propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

* Rear area security

In addition, by 1944, despite the obvious tide of war, the Kenpeitai were arresting people for antiwar sentiment and defeatism

Defeatism is the acceptance of defeat without struggle, often with negative connotations. It can be linked to pessimism in psychology, and may sometimes be used synonymously with fatalism or determinism.

History

The term ''defeatism'' is commonly ...

.

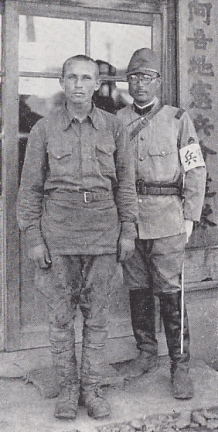

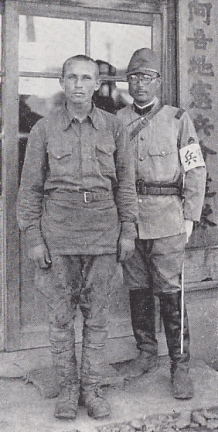

Uniform

Kenpeitai personnel wore either the standard M1938 field uniform or the cavalry uniform with high black leather boots. Civilian clothes were also authorized with rank badges or the Japanese Imperialchrysanthemum

Chrysanthemums (), sometimes called mums or chrysanths, are flowering plants of the genus ''Chrysanthemum'' in the family Asteraceae. They are native to East Asia and northeastern Europe. Most species originate from East Asia and the center ...

worn under the jacket lapel

Lapels ( ) are the folded flaps of cloth on the front of a jacket or coat below the collar and are most commonly found on formal clothing and suit jackets. Usually they are formed by folding over the front edges of the jacket or coat and sewing t ...

. Uniformed personnel also wore a black chevron

Chevron (often relating to V-shaped patterns) may refer to:

Science and technology

* Chevron (aerospace), sawtooth patterns on some jet engines

* Chevron (anatomy), a bone

* ''Eulithis testata'', a moth

* Chevron (geology), a fold in rock lay ...

on their uniforms and a white armband on the left arm with the characters ''ken'' (憲, "law") and ''hei'' (兵, "soldier"), together read as ''kenpei'' or ''kempei,'' which translates to "military police".

Until 1942, a full dress uniform comprising a red kepi

The kepi ( ) is a cap with a flat circular top and a peak, or visor. In English, the term is a loanword of french: képi, itself a re-spelled version of the gsw, Käppi, a diminutive form of , meaning "cap". In Europe, this headgear is most ...

, gold and red waist sash, dark blue tunic

A tunic is a garment for the body, usually simple in style, reaching from the shoulders to a length somewhere between the hips and the knees. The name derives from the Latin ''tunica'', the basic garment worn by both men and women in Ancient Rome ...

and trousers with black facings

A facing colour is a common tailoring technique for European military uniforms where the visible inside lining of a standard military jacket, coat or tunic is of a different colour to that of the garment itself.René Chartrand, William Younghusba ...

was authorized for Kenpeitai officers on ceremonial occasions. Rank insignia comprised gold Austrian knot

An Austrian knot (or Hungarian knot), alternatively warrior's knot or , is an elaborate design of twisted cord or lace worn as part of a dress uniform, usually on the lower sleeve. It is usually a distinction worn by officers; the major exceptio ...

s and epaulette

Epaulette (; also spelled epaulet) is a type of ornamental shoulder piece or decoration used as insignia of military rank, rank by armed forces and other organizations. Flexible metal epaulettes (usually made from brass) are referred to as ''sh ...

s.

Kenpeitai officers were armed with a cavalry sabre and pistol

A pistol is a handgun, more specifically one with the chamber integral to its gun barrel, though in common usage the two terms are often used interchangeably. The English word was introduced in , when early handguns were produced in Europe, an ...

, while enlisted men had a pistol and bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustr ...

. Junior NCOs

A non-commissioned officer (NCO) is a military officer who has not pursued a commission. Non-commissioned officers usually earn their position of authority by promotion through the enlisted ranks. (Non-officers, which includes most or all enli ...

carried a ''shinai

A is a Japanese sword typically made of bamboo used for practice and competition in ''kendo''. ''Shinai'' are also used in other martial arts, but may be styled differently from ''kendo shinai'', and represented with different characters. T ...

'' (竹刀, "bamboo kendo

is a modern Japanese martial art, descended from kenjutsu (one of the old Japanese martial arts, swordsmanship), that uses bamboo swords (shinai) as well as protective armor (bōgu). Today, it is widely practiced within Japan and has spread ...

sword"), especially when dealing with prisoners.

Other intelligence sections

* The Kenpeitai had responsibilities similar toGerman

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

SS and SD, Soviet NKVD

The People's Commissariat for Internal Affairs (russian: Наро́дный комиссариа́т вну́тренних дел, Naródnyy komissariát vnútrennikh del, ), abbreviated NKVD ( ), was the interior ministry of the Soviet Union.

...

, and Politruk units, carrying out both internal and external surveillance, and using the ''kikosaku'' doctrine of lethal extrajudicial punishment, often as a brutal interrogation

Interrogation (also called questioning) is interviewing as commonly employed by law enforcement officers, military personnel, intelligence agencies, organized crime syndicates, and terrorist organizations with the goal of eliciting useful informa ...

method, against perceived exterior enemies, defectors

In politics, a defector is a person who gives up allegiance to one state in exchange for allegiance to another, changing sides in a way which is considered illegitimate by the first state. More broadly, defection involves abandoning a person, ca ...

and traitors

Treason is the crime of attacking a state authority to which one owes allegiance. This typically includes acts such as participating in a war against one's native country, attempting to overthrow its government, spying on its military, its diplo ...

.

* A similar Japanese wartime special unit was the Overseas Security and Colonial Police Service, tasked with maintaining security in occupied Southeast Asian territories, in addition to carrying out various administrative responsibilities.

See also

*Internal security

Internal security is the act of keeping peace within the borders of a sovereign state or other Self-governance, self-governing territories, generally by upholding the national law and defending against internal security threats. Responsibility fo ...

* History of espionage

Spying, as well as other intelligence assessment, has existed since ancient times. In the 1980s scholars characterized foreign intelligence as "the missing dimension" of historical scholarship." Since then a largely popular and scholarly literatur ...

* List of Japanese spies, 1930–45

This is a list of Japanese spies including leaders and commanders of the Japanese Secret Intelligence Services (''Kempeitai'') in the period 1930 to 1945.

*The Emperor of Japan (Tenno) was constitutionally the supreme commander of the Japanese ...

* Police services of the Empire of Japan

The of the Empire of Japan comprised numerous police services, in many cases with overlapping jurisdictions.

History and background

During the Tokugawa bakufu (1603–1867), police functions in Japan operated through appointed town magistrates ...

(Keishichō, until 1945)

* Unit 100

was an Imperial Japanese Army facility called the Kwantung Army Warhorse Disease Prevention Shop that focused on the development of biological weapons during World War II. It was operated by the Kempeitai, the Japanese military police. Its hea ...

* Fukushima Yasumasa

Baron was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army.

Life as a Samurai

Fukushima was born to a ''samurai'' family; his father was a retainer to the ''daimyō'' of Matsumoto, in Shinano Province (modern Nagano Prefecture). He also became a retain ...

(Kenpeitai founder)

* ''Tenko'' (TV series)

* ''The Man in the High Castle'' (TV series)

References

External links

Japanese World War II-era nationalist groups

{{Authority control Imperial Japanese Army Political repression in Japan Defunct Japanese intelligence agencies Defunct law enforcement agencies of Japan

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

Intelligence services of World War II

Secret police