The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical

nation-state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may inc ...

and

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

that existed from the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II

1947 constitution and subsequent formation of modern

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

.

It encompassed the

Japanese archipelago

The Japanese archipelago (Japanese: 日本列島, ''Nihon rettō'') is a archipelago, group of 6,852 islands that form the country of Japan, as well as the Russian island of Sakhalin. It extends over from the Sea of Okhotsk in the northeast to t ...

and several

colonies

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the '' metropolitan state'' ...

,

protectorate

A protectorate, in the context of international relations, is a State (polity), state that is under protection by another state for defence against aggression and other violations of law. It is a dependent territory that enjoys autonomy over m ...

s,

mandates, and other

territories

A territory is an area of land, sea, or space, particularly belonging or connected to a country, person, or animal.

In international politics, a territory is usually either the total area from which a state may extract power resources or an ...

.

Under the slogans of and following the

Boshin War

The , sometimes known as the Japanese Revolution or Japanese Civil War, was a civil war in Japan fought from 1868 to 1869 between forces of the ruling Tokugawa shogunate and a clique seeking to seize political power in the name of the Imperi ...

and restoration of power to the Emperor from the

Shogun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

, Japan underwent a period of

industrialization

Industrialisation ( alternatively spelled industrialization) is the period of social and economic change that transforms a human group from an agrarian society into an industrial society. This involves an extensive re-organisation of an econo ...

and

militarization

Militarization, or militarisation, is the process by which a society organizes itself for military conflict and violence. It is related to militarism, which is an ideology that reflects the level of militarization of a state. The process of milit ...

, the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

, which is often regarded as the fastest

modernisation

Modernization theory is used to explain the process of modernization within societies. The "classical" theories of modernization of the 1950s and 1960s drew on sociological analyses of Karl Marx, Emile Durkheim and a partial reading of Max Weber, ...

of any country to date. All of these aspects contributed to Japan's emergence as a

great power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

and the establishment of

a colonial empire following the

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

, the

Boxer Rebellion

The Boxer Rebellion, also known as the Boxer Uprising, the Boxer Insurrection, or the Yihetuan Movement, was an anti-foreign, anti-colonial, and anti-Christian uprising in China between 1899 and 1901, towards the end of the Qing dynasty, by ...

, the

Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

, and

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

. Economic and political turmoil in the 1920s, including the

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

, led to the rise of

militarism

Militarism is the belief or the desire of a government or a people that a state should maintain a strong military capability and to use it aggressively to expand national interests and/or values. It may also imply the glorification of the mili ...

,

nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

and

totalitarianism

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and reg ...

as embodied in the

Showa Statism ideology, eventually culminating in Japan's membership in the

Axis alliance and the conquest of a large part of the

Asia-Pacific

Asia-Pacific (APAC) is the part of the world near the western Pacific Ocean. The Asia-Pacific region varies in area depending on context, but it generally includes East Asia, Russian Far East, South Asia, Southeast Asia, Australia and Pacific Isla ...

in

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

.

Japan's armed forces initially achieved large-scale military successes during the

Second Sino-Japanese War

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

(1937–1945) and the

Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

. However, starting from 1942, particularly after the

Battles of Midway and

Guadalcanal

Guadalcanal (; indigenous name: ''Isatabu'') is the principal island in Guadalcanal Province of Solomon Islands, located in the south-western Pacific, northeast of Australia. It is the largest island in the Solomon Islands by area, and the seco ...

, Japan was forced to adopt a defensive stance, and the American

island hopping campaign

Leapfrogging, also known as island hopping, was a military strategy employed by the Allies in the Pacific War against the Empire of Japan during World War II.

The key idea is to bypass heavily fortified enemy islands instead of trying to captu ...

led to the eventual loss of many of Japan's

Oceanian

Oceania (, , ) is a geographical region that includes Australasia, Melanesia, Micronesia, and Polynesia. Spanning the Eastern and Western hemispheres, Oceania is estimated to have a land area of and a population of around 44.5 million as of ...

island possessions throughout the following three years. Eventually, the Americans captured

Iwo Jima

Iwo Jima (, also ), known in Japan as , is one of the Japanese Volcano Islands and lies south of the Bonin Islands. Together with other islands, they form the Ogasawara Archipelago. The highest point of Iwo Jima is Mount Suribachi at high.

...

and

Okinawa Island

is the largest of the Okinawa Islands and the Ryukyu (''Nansei'') Islands of Japan in the Kyushu region. It is the smallest and least populated of the five main islands of Japan. The island is approximately long, an average wide, and has an ...

, leaving the Japanese mainland unprotected and without a significant naval defense force. The U.S. forces had

planned an invasion, but Japan

surrendered following the

atomic bombings of Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

and the nearly simultaneous

Soviet declaration of war on August 9, 1945, and subsequent

invasion of Manchuria and other territories. The Pacific War officially came to a close on September 2, 1945. A

period of occupation by the Allies followed. In 1947, with American involvement, a

new constitution was enacted, officially bringing the Empire of Japan to an end, and Japan's

Imperial Army was replaced with the

Japan Self-Defense Forces

The Japan Self-Defense Forces ( ja, 自衛隊, Jieitai; abbreviated JSDF), also informally known as the Japanese Armed Forces, are the unified ''de facto''Since Article 9 of the Japanese Constitution outlaws the formation of armed forces, the ...

. Occupation and reconstruction continued until 1952, eventually forming the

current

Currents, Current or The Current may refer to:

Science and technology

* Current (fluid), the flow of a liquid or a gas

** Air current, a flow of air

** Ocean current, a current in the ocean

*** Rip current, a kind of water current

** Current (stre ...

constitutional monarchy known as

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the north ...

.

The Empire of Japan had three emperors, although it came to an end partway through Shōwa's reign. The emperors were given

posthumous names

A posthumous name is an honorary name given mostly to the notable dead in East Asian culture. It is predominantly practiced in East Asian countries such as China, Korea, Vietnam, Japan, and Thailand. Reflecting on the person's accomplishments o ...

, and the emperors are as follows:

Meiji,

Taisho, and

Shōwa.

Terminology

The historical state is frequently referred to as the "Empire of Japan", the "Japanese Empire", or "Imperial Japan" in English. In Japanese it is referred to as ,

which translates to "Empire of Great Japan" ( "Great", "Japanese", "Empire"). ''Teikoku'' is itself composed of the nouns "referring to an emperor" and "nation, state", literally "Imperial State" or "Imperial Realm" (compare the

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

**Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ger ...

''

Kaiserreich

Kaiserreich may refer to:

*Empire, state ruled by an emperor

*Holy Roman Empire (800/962–1806)

*Austrian Empire (1804–1867)

* Austro-Hungarian Empire (1867–1918)

* German Empire (1871–1918)

*'' Kaiserreich: Legacy of the Weltkrieg'', a mod ...

'').

This meaning is significant in terms of geography, encompassing Japan, and its surrounding areas. The nomenclature ''Empire of Japan'' had existed since the anti-Tokugawa domains,

Satsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

and

Chōshū, which founded their new government during the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

, with the intention of forming a modern state to resist Western domination. Later the Empire emerged as a major colonial power in the world.

Due to its name in ''

kanji

are the logographic Chinese characters taken from the Chinese family of scripts, Chinese script and used in the writing of Japanese language, Japanese. They were made a major part of the Japanese writing system during the time of Old Japanese ...

'' characters and its flag, it was also given the

exonyms

An endonym (from Greek: , 'inner' + , 'name'; also known as autonym) is a common, ''native'' name for a geographical place, group of people, individual person, language or dialect, meaning that it is used inside that particular place, group, o ...

"Empire of the Sun" and “Empire of the Rising Sun.”

History

Background

After two centuries, the seclusion policy, or ''

sakoku

was the Isolationism, isolationist Foreign policy of Japan, foreign policy of the Japanese Tokugawa shogunate under which, for a period of 265 years during the Edo period (from 1603 to 1868), relations and trade between Japan and other countri ...

'', under the ''

shōgun

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

s'' of the

Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characteriz ...

came to an end when the country was forced open to trade by the

Convention of Kanagawa

The Convention of Kanagawa, also known as the Kanagawa Treaty (, ''Kanagawa Jōyaku'') or the Japan–US Treaty of Peace and Amity (, ''Nichibei Washin Jōyaku''), was a treaty signed between the United States and the Tokugawa Shogunate on March ...

which came when

Matthew C. Perry

Matthew Calbraith Perry (April 10, 1794 – March 4, 1858) was a commodore of the United States Navy who commanded ships in several wars, including the War of 1812 and the Mexican–American War (1846–1848). He played a leading role in the o ...

arrived in Japan in 1854. Thus, the period known as

Bakumatsu

was the final years of the Edo period when the Tokugawa shogunate ended. Between 1853 and 1867, Japan ended its isolationist foreign policy known as and changed from a feudal Tokugawa shogunate to the modern empire of the Meiji government ...

began.

The following years saw increased foreign trade and interaction; commercial treaties between the

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

and Western countries were signed. In large part due to the humiliating terms of these

unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

, the shogunate soon faced internal hostility, which materialized into a radical,

xenophobic

Xenophobia () is the fear or dislike of anything which is perceived as being foreign or strange. It is an expression of perceived conflict between an in-group and out-group and may manifest in suspicion by the one of the other's activities, a ...

movement, the ''

sonnō jōi

was a ''yojijukugo'' (four-character compound) phrase used as the rallying cry and slogan of a political movement in Japan in the 1850s and 1860s during the Bakumatsu period. Based on Neo-Confucianism and Japanese nativism, the movement sought ...

'' (literally "Revere the Emperor, expel the barbarians").

In March 1863, the Emperor issued the "

order to expel barbarians

The was an edict issued by the Japanese Emperor Kōmei in 1863 against the Westernization of Japan following the opening of the country by Commodore Perry in 1854.

The order

The edict was based on widespread anti-foreign and legitimist sentim ...

." Although the shogunate had no intention of enforcing the order, it nevertheless inspired attacks against the shogunate itself and against foreigners in Japan. The

Namamugi Incident

The , also known as the Kanagawa incident and Richardson affair, was a political crisis that occurred in the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan during the ''Bakumatsu'' on 14 September 1862. Charles Lennox Richardson, a British merchant, was killed by t ...

during 1862 led to the murder of an Englishman,

Charles Lennox Richardson

Charles Lennox Richardson (16 April 1834 – 14 September 1862) was a British merchant based in Shanghai who was killed in Japan during the Namamugi Incident. His middle name is spelled ''Lenox'' in census and family documents.

Merchant

Richardso ...

, by a party of

samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

from

Satsuma Satsuma may refer to:

* Satsuma (fruit), a citrus fruit

* ''Satsuma'' (gastropod), a genus of land snails

Places Japan

* Satsuma, Kagoshima, a Japanese town

* Satsuma District, Kagoshima, a district in Kagoshima Prefecture

* Satsuma Domain, a sou ...

. The British demanded reparations but were denied. While attempting to exact payment, the

Royal Navy

The Royal Navy (RN) is the United Kingdom's naval warfare force. Although warships were used by English and Scottish kings from the early medieval period, the first major maritime engagements were fought in the Hundred Years' War against F ...

was fired on from coastal batteries near the town of

Kagoshima

, abbreviated to , is the capital city of Kagoshima Prefecture, Japan. Located at the southwestern tip of the island of Kyushu, Kagoshima is the largest city in the prefecture by some margin. It has been nicknamed the "Naples of the Eastern wor ...

. They responded by

bombarding the port of Kagoshima in 1863. The Tokugawa government agreed to pay an indemnity for Richardson's death. Shelling of foreign shipping in

Shimonoseki

is a city located in Yamaguchi Prefecture, Japan. With a population of 265,684, it is the largest city in Yamaguchi Prefecture and the fifth-largest city in the Chūgoku region. It is located at the southwestern tip of Honshu facing the Tsushim ...

and attacks against foreign property led to the

bombardment of Shimonoseki

The refers to a series of military engagements in 1863 and 1864, fought to control the Shimonoseki Straits of Japan by joint naval forces from Great Britain, France, the Netherlands and the United States, against the Japanese feudal domain of ...

by a multinational force in 1864. The

Chōshū clan also launched the failed coup known as the

Kinmon incident

The , also known as the , was a rebellion against the Tokugawa shogunate in Japan that took place on August 20 unar calendar: 19th day, 7th month 1864, near the Imperial Palace in Kyoto.

History

Starting with the Convention of Kanagawa in 1 ...

. The

Satsuma-Chōshū alliance was established in 1866 to combine their efforts to overthrow the Tokugawa ''bakufu''. In early 1867,

Emperor Kōmei

was the 121st Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Imperial Household Agency (''Kunaichō'')孝明天皇 (121)/ref> Kōmei's reign spanned the years from 1846 through 1867, corresponding to the final years of the ...

died of smallpox and was replaced by his son,

Crown Prince Mutsuhito (Meiji).

On November 9, 1867,

Tokugawa Yoshinobu

Prince was the 15th and last ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa shogunate of Japan. He was part of a movement which aimed to reform the aging shogunate, but was ultimately unsuccessful. He resigned of his position as shogun in late 1867, while aiming ...

resigned from his post and authorities to the

Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

, agreeing to "be the instrument for carrying out" imperial orders, leading to the end of the Tokugawa shogunate. However, while Yoshinobu's resignation had created a nominal void at the highest level of government, his apparatus of state continued to exist. Moreover, the shogunal government, the Tokugawa family in particular, remained a prominent force in the evolving political order and retained many executive powers, a prospect hard-liners from Satsuma and Chōshū found intolerable.

On January 3, 1868, Satsuma-Chōshū forces seized the

imperial palace in

Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the ci ...

, and the following day had the fifteen-year-old

Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

declare his own restoration to full power. Although the majority of the imperial consultative assembly was happy with the formal declaration of direct rule by the court and tended to support a continued collaboration with the Tokugawa,

Saigō Takamori

was a Japanese samurai and nobleman. He was one of the most influential samurai in Japanese history and one of the three great nobles who led the Meiji Restoration. Living during the late Edo and early Meiji periods, he later led the Satsum ...

, leader of the Satsuma clan, threatened the assembly into abolishing the title ''shōgun'' and ordered the confiscation of Yoshinobu's lands.

On January 17, 1868, Yoshinobu declared "that he would not be bound by the proclamation of the Restoration and called on the court to rescind it". On January 24, Yoshinobu decided to prepare an attack on Kyoto, occupied by Satsuma and Chōshū forces. This decision was prompted by his learning of a series of

arson

Arson is the crime of willfully and deliberately setting fire to or charring property. Although the act of arson typically involves buildings, the term can also refer to the intentional burning of other things, such as motor vehicles, wat ...

attacks in Edo, starting with the burning of the outworks of

Edo Castle

is a flatland castle that was built in 1457 by Ōta Dōkan in Edo, Toshima District, Musashi Province. In modern times it is part of the Tokyo Imperial Palace in Chiyoda, Tokyo and is therefore also known as .

Tokugawa Ieyasu established the ...

, the main Tokugawa residence.

Boshin War

The was fought between January 1868 and May 1869. The alliance of samurai from southern and western domains and court officials had now secured the cooperation of the young Emperor Meiji, who ordered the dissolution of the two-hundred-year-old Tokugawa shogunate. Tokugawa Yoshinobu launched a military campaign to seize the emperor's court in Kyoto. However, the tide rapidly turned in favor of the smaller but relatively modernized imperial faction and resulted in defections of many ''daimyōs'' to the Imperial side. The

Battle of Toba–Fushimi

The occurred between pro-Imperial and Tokugawa shogunate forces during the Boshin War in Japan. The battle started on 27 January 1868 (or fourth year of Keiō, first month, 3rd day, according to the lunar calendar), when the forces of the shog ...

was a decisive victory in which a combined army from Chōshū, Tosa, and Satsuma domains defeated the Tokugawa army. A series of battles were then fought in pursuit of supporters of the Shogunate; Edo surrendered to the Imperial forces and afterward, Yoshinobu personally surrendered. Yoshinobu was stripped of all his power by Emperor Meiji and most of Japan accepted the emperor's rule.

Pro-Tokugawa remnants, however, then retreated to northern Honshū (

Ōuetsu Reppan Dōmei

The was a Japanese military-political coalition established and disestablished over the course of several months in early to mid-1868 during the Boshin War. Its flag was either a white interwoven five-pointed star on a black field, or a black i ...

) and later to Ezo (present-day

Hokkaidō

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

), where they established the breakaway

Republic of Ezo

The was a short-lived separatist state established in 1869 on the island of Ezo, now Hokkaido, by a part of the former military of the Tokugawa shogunate at the end of the ''Bakumatsu'' period in Japan. It was the first government to attempt t ...

. An expeditionary force was dispatched by the new government and the Ezo Republic forces were overwhelmed. The

siege of Hakodate came to an end in May 1869 and the remaining forces surrendered.

Meiji era (1868–1912)

The

Charter Oath

The was promulgated on 6 April 1868 in Kyoto Imperial Palace. The Oath outlined the main aims and the course of action to be followed during Emperor Meiji's reign, setting the legal stage for Japan's modernization. This also set up a process of u ...

was made public at the enthronement of Emperor Meiji of Japan on April 7, 1868. The Oath outlined the main aims and the course of action to be followed during Emperor Meiji's reign, setting the legal stage for Japan's modernization. The

Meiji leaders also aimed to boost morale and win financial support for the

new government.

Japan dispatched the

Iwakura Mission

The Iwakura Mission or Iwakura Embassy (, ''Iwakura Shisetsudan'') was a Japanese diplomatic voyage to the United States and Europe conducted between 1871 and 1873 by leading statesmen and scholars of the Meiji period. It was not the only such m ...

in 1871. The mission traveled the world in order to renegotiate the

unequal treaties

Unequal treaty is the name given by the Chinese to a series of treaties signed during the 19th and early 20th centuries, between China (mostly referring to the Qing dynasty) and various Western powers (specifically the British Empire, France, the ...

with the United States and European countries that Japan had been forced into during the Tokugawa shogunate, and to gather information on western social and economic systems, in order to effect the modernization of Japan. Renegotiation of the unequal treaties was universally unsuccessful, but close observation of the American and European systems inspired members on their return to bring about modernization initiatives in Japan. Japan made a

territorial delimitation treaty with

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

in 1875, gaining all the

Kuril islands

The Kuril Islands or Kurile Islands (; rus, Кури́льские острова́, r=Kuril'skiye ostrova, p=kʊˈrʲilʲskʲɪjə ɐstrɐˈva; Japanese: or ) are a volcanic archipelago currently administered as part of Sakhalin Oblast in the ...

in exchange for

Sakhalin island

Sakhalin ( rus, Сахали́н, r=Sakhalín, p=səxɐˈlʲin; ja, 樺太 ''Karafuto''; zh, c=, p=Kùyèdǎo, s=库页岛, t=庫頁島; Manchu: ᠰᠠᡥᠠᠯᡳᠶᠠᠨ, ''Sahaliyan''; Orok: Бугата на̄, ''Bugata nā''; Nivkh: ...

.

The Japanese government sent observers to Western countries to observe and learn their practices, and also paid "

foreign advisors" in a variety of fields to come to Japan to educate the populace. For instance, the judicial system and

constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

were modeled after

Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

, described by

Saburō Ienaga as "an attempt to control popular thought with a blend of

Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

and

German conservatism

Conservatism in Germany has encompassed a wide range of theories and ideologies in the last three hundred years, but most historical conservative theories supported the monarchical/hierarchical political structure.

Historical conservative strai ...

." The government also outlawed customs linked to Japan's feudal past, such as publicly displaying and wearing

katana

A is a Japanese sword characterized by a curved, single-edged blade with a circular or squared guard and long grip to accommodate two hands. Developed later than the ''tachi'', it was used by samurai in feudal Japan and worn with the edge fa ...

and the

top knot, both of which were characteristic of the

samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They h ...

class, which was abolished together with the caste system. This would later bring the Meiji government into

conflict with the samurai.

Several writers, under the constant threat of assassination from their political foes, were influential in winning Japanese support for

westernization

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the ''Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, economi ...

. One such writer was

Fukuzawa Yukichi

was a Japanese educator, philosopher, writer, entrepreneur and samurai who founded Keio University, the newspaper '' Jiji-Shinpō'', and the Institute for Study of Infectious Diseases.

Fukuzawa was an early advocate for reform in Japan. His ...

, whose works included "Conditions in the West," "

Leaving Asia", and "An Outline of a Theory of Civilization," which detailed Western society and his own philosophies. In the

Meiji Restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

period, military and economic power was emphasized. Military strength became the means for national development and stability. Imperial Japan became the only non-Western

world power

A great power is a sovereign state that is recognized as having the ability and expertise to exert its influence on a global scale. Great powers characteristically possess military and economic strength, as well as diplomatic and soft power inf ...

and a major force in

East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

in about 25 years as a result of industrialization and economic development.

As writer

Albrecht Fürst von Urach comments in his booklet "The Secret of Japan's Strength," published in 1942, during the

Axis powers

The Axis powers, ; it, Potenze dell'Asse ; ja, 枢軸国 ''Sūjikukoku'', group=nb originally called the Rome–Berlin Axis, was a military coalition that initiated World War II and fought against the Allies. Its principal members were ...

period:

The rise of Japan to a world power during the past 80 years is the greatest miracle in world history. The mighty empires of antiquity, the major political institutions of the Middle Ages and the early modern era, the Spanish Empire, the British Empire, all needed centuries to achieve their full strength. Japan's rise has been meteoric. After only 80 years, it is one of the few great powers that determine the fate of the world.

Transposition in social order and cultural destruction

In the 1860s, Japan began to experience great social turmoil and rapid modernization. The feudal caste system in Japan formally ended in 1869 with the

Meiji restoration

The , referred to at the time as the , and also known as the Meiji Renovation, Revolution, Regeneration, Reform, or Renewal, was a political event that restored practical imperial rule to Japan in 1868 under Emperor Meiji. Although there were ...

. In 1871, the newly formed

Meiji government issued a decree called ''Senmin Haishirei'' (

賤民廃止令 ''Edict Abolishing Ignoble Classes'') giving

burakumin

is a name for a low-status social group in Japan. It is a term for ethnic Japanese people with occupations considered as being associated with , such as executioners, undertakers, slaughterhouse workers, butchers, or tanners.

During Japan's ...

equal legal status. It is currently better known as the ''Kaihōrei'' (

解放令 ''Emancipation Edict''). However, the elimination of their economic monopolies over certain occupations actually led to a decline in their general living standards, while social discrimination simply continued. For example, the ban on the consumption of meat from livestock was lifted in 1871, and many former ''burakumin'' moved on to work in

abattoirs

A slaughterhouse, also called abattoir (), is a facility where animals are slaughtered to provide food. Slaughterhouses supply meat, which then becomes the responsibility of a packaging facility.

Slaughterhouses that produce meat that is no ...

and as

butcher

A butcher is a person who may Animal slaughter, slaughter animals, dress their flesh, sell their meat, or participate within any combination of these three tasks. They may prepare standard cuts of meat and poultry for sale in retail or wholesal ...

s. However, slow-changing social attitudes, especially in the countryside, meant that abattoirs and workers were met with hostility from local residents. Continued ostracism as well as the decline in living standards led to former ''burakumin'' communities turning into slum areas.

In the

Blood tax riots

The were a series of violent uprisings around Japan in the spring of 1873 in opposition to the institution of mandatory military conscription for all male citizens (described as a "blood tax") in the wake of the Meiji Restoration. Secondary caus ...

, the Japanese Meiji government brutally put down revolts by Japanese samurai angry that the traditional

untouchable status of burakumin was legally revoked.

The social tension continued to grow during the

Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

, affecting religious practices and institutions. Conversion from traditional faith was no longer legally forbidden, officials lifted the 250-year ban on Christianity, and missionaries of established Christian churches reentered Japan. The traditional

syncreticism between Shinto and

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and gra ...

ended. Losing the protection of the Japanese government which Buddhism had enjoyed for centuries, Buddhist monks faced radical difficulties in sustaining their institutions, but their activities also became less restrained by governmental policies and restrictions. As social conflicts emerged in this last decade of the

Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was characteriz ...

, some new religious movements appeared, which were directly influenced by

shamanism

Shamanism is a religious practice that involves a practitioner (shaman) interacting with what they believe to be a Spirit world (Spiritualism), spirit world through Altered state of consciousness, altered states of consciousness, such as tranc ...

and

Shinto

Shinto () is a religion from Japan. Classified as an East Asian religion by scholars of religion, its practitioners often regard it as Japan's indigenous religion and as a nature religion. Scholars sometimes call its practitioners ''Shintois ...

.

Emperor Ogimachi issued edicts to ban Catholicism in 1565 and 1568, but to little effect. Beginning in 1587 with imperial regent Toyotomi Hideyoshi's ban on Jesuit missionaries, Christianity was repressed as a threat to national unity. Under Hideyoshi and the succeeding

Tokugawa shogunate

The Tokugawa shogunate (, Japanese 徳川幕府 ''Tokugawa bakufu''), also known as the , was the military government of Japan during the Edo period from 1603 to 1868. Nussbaum, Louis-Frédéric. (2005)"''Tokugawa-jidai''"in ''Japan Encyclopedia ...

, Catholic Christianity was repressed and adherents were persecuted. After the Tokugawa shogunate banned Christianity in 1620, it ceased to exist publicly. Many Catholics went underground, becoming , while others lost their lives. After Japan was opened to foreign powers in 1853, many Christian clergymen were sent from Catholic, Protestant, and Orthodox churches, though proselytism was still banned. Only after the Meiji Restoration, was Christianity re-established in Japan. Freedom of religion was introduced in 1871, giving all Christian communities the right to legal existence and preaching.

Eastern Orthodoxy

Eastern Orthodoxy, also known as Eastern Orthodox Christianity, is one of the three main Branches of Christianity, branches of Chalcedonian Christianity, alongside Catholic Church, Catholicism and Protestantism.

Like the Pentarchy of the first m ...

was brought to Japan in the 19th century by St. Nicholas (baptized as Ivan Dmitrievich Kasatkin),

[''Equal-to-the-Apostles St. Nicholas of Japan, Russian Orthodox Cathedral of Saint John the Baptist web-site, Washington D.C.''] who was sent in 1861 by the

Russian Orthodox Church

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

to

Hakodate

is a city and port located in Oshima Subprefecture, Hokkaido, Japan. It is the capital city of Oshima Subprefecture. As of July 31, 2011, the city has an estimated population of 279,851 with 143,221 households, and a population density of 412.8 ...

,

Hokkaidō

is Japan's second largest island and comprises the largest and northernmost prefecture, making up its own region. The Tsugaru Strait separates Hokkaidō from Honshu; the two islands are connected by the undersea railway Seikan Tunnel.

The la ...

as priest to a chapel of the Russian Consulate. St. Nicholas of Japan made his own translation of the

New Testament

The New Testament grc, Ἡ Καινὴ Διαθήκη, transl. ; la, Novum Testamentum. (NT) is the second division of the Christian biblical canon. It discusses the teachings and person of Jesus, as well as events in first-century Christ ...

and some other religious books (

Lenten Triodion

The Triodion ( el, Τριῴδιον, ; cu, Постнаѧ Трїωдь, ; ro, Triodul, sq, Triod/Triodi), also called the Lenten Triodion (, ), is a liturgical book used by the Eastern Orthodox Church. The book contains the propers for th ...

,

Pentecostarion

The Pentecostarion ( el, Πεντηκοστάριον, ; cu, Цвѣтнаѧ Трїωдь, , literally "Flowery Triodon"; ro, Penticostar) is the liturgical book used by the Eastern Orthodox and Byzantine Catholic churches during the Paschal ...

,

Feast Services,

Book of Psalms

The Book of Psalms ( or ; he, תְּהִלִּים, , lit. "praises"), also known as the Psalms, or the Psalter, is the first book of the ("Writings"), the third section of the Tanakh, and a book of the Old Testament. The title is derived f ...

,

Irmologion

Irmologion ( grc-gre, τὸ εἱρμολόγιον ) is a liturgical book of the Eastern Orthodox Church and those Eastern Catholic Churches which follow the Byzantine Rite. It contains ''irmoi'' () organised in sequences of odes (, sg. ) an ...

) into

Japanese

Japanese may refer to:

* Something from or related to Japan, an island country in East Asia

* Japanese language, spoken mainly in Japan

* Japanese people, the ethnic group that identifies with Japan through ancestry or culture

** Japanese diaspor ...

. Nicholas has since been canonized as a saint by the

Patriarchate of Moscow

, native_name_lang = ru

, image = Moscow July 2011-7a.jpg

, imagewidth =

, alt =

, caption = Cathedral of Christ the Saviour in Moscow, Russia

, abbreviation = ROC

, type ...

in 1970, and is now recognized as St. Nicholas,

Equal-to-the-Apostles

Equal-to-apostles or equal-to-the-apostles (; la, aequalis apostolis; ar, معادل الرسل, ''muʿādil ar-rusul''; ka, მოციქულთასწორი, tr; ro, întocmai cu Apostolii; russian: равноапостольный, ...

to Japan. His commemoration day is February 16.

Andronic Nikolsky

Archbishop Andronik (also spelled Andronic; russian: Архиепископ Андроник, secular name Vladimir Alexandrovich Nikolsky, russian: Владимир Александрович Никольский; August 1, 1870 – July 7, 191 ...

, appointed the first Bishop of

Kyoto

Kyoto (; Japanese: , ''Kyōto'' ), officially , is the capital city of Kyoto Prefecture in Japan. Located in the Kansai region on the island of Honshu, Kyoto forms a part of the Keihanshin metropolitan area along with Osaka and Kobe. , the ci ...

and later martyred as the archbishop of

Perm

Perm or PERM may refer to:

Places

*Perm, Russia, a city in Russia

** Permsky District, the district

**Perm Krai, a federal subject of Russia since 2005

**Perm Oblast, a former federal subject of Russia 1938–2005

**Perm Governorate, an administra ...

during the

Russian Revolution

The Russian Revolution was a period of Political revolution (Trotskyism), political and social revolution that took place in the former Russian Empire which began during the First World War. This period saw Russia abolish its monarchy and ad ...

, was also canonized by the Russian Orthodox Church as a Saint and Martyr in the year 2000.

Divie Bethune McCartee

Divie Bethune McCartee (Simplified Chinese: 麦嘉缔) (1820–1900) was an American Protestant Christian medical missionary, educator and U.S. diplomat in China and Japan, first appointed by the American Presbyterian Mission in 1843.

In 1845, ...

was the first ordained

Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

minister

mission

Mission (from Latin ''missio'' "the act of sending out") may refer to:

Organised activities Religion

*Christian mission, an organized effort to spread Christianity

*Mission (LDS Church), an administrative area of The Church of Jesus Christ of ...

ary to visit Japan, in 1861–1862. His gospel

tract

Tract may refer to:

Geography and real estate

* Housing tract, an area of land that is subdivided into smaller individual lots

* Land lot or tract, a section of land

* Census tract, a geographic region defined for the purpose of taking a census

...

translated into Japanese was among the first Protestant literature in Japan. In 1865, McCartee moved back to

Ningbo

Ningbo (; Ningbonese: ''gnin² poq⁷'' , Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), formerly romanized as Ningpo, is a major sub-provincial city in northeast Zhejiang province, People's Republic of China. It comprises 6 urban districts, 2 sate ...

, China, but others have followed in his footsteps. There was a burst of growth of Christianity in the late 19th century when Japan re-opened its doors to the West. Protestant church growth slowed dramatically in the early 20th century under the influence of the military government during the

Shōwa period

Shōwa may refer to:

* Hirohito (1901–1989), the 124th Emperor of Japan, known posthumously as Emperor Shōwa

* Showa Corporation, a Japanese suspension and shock manufacturer, affiliated with the Honda keiretsu

Japanese eras

* Jōwa (Heian ...

.

Under the Meiji Restoration, the practices of the samurai classes, deemed feudal and unsuitable for modern times following the end of in 1853, resulted in a number of edicts intended to 'modernise' the appearance of upper class Japanese men. With the Dampatsurei Edict of 1871 issued by

Emperor Meiji

, also called or , was the 122nd emperor of Japan according to the traditional order of succession. Reigning from 13 February 1867 to his death, he was the first monarch of the Empire of Japan and presided over the Meiji era. He was the figur ...

during the early

Meiji Era

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization b ...

, men of the samurai classes were forced to cut their hair short, effectively abandoning the

chonmage

The is a type of traditional Japanese topknot haircut worn by men. It is most commonly associated with the Edo period (1603–1867) and samurai, and in recent times with sumo wrestlers. It was originally a method of using hair to hold a sam ...

() hairstyle.

During the early 20th century, the government was suspicious towards a number of unauthorized religious movements and periodically made attempts to suppress them. Government suppression was especially severe from the 1930s until the early 1940s, when the growth of

Japanese nationalism

is a form of nationalism that asserts the belief that the Japanese are a monolithic nation with a single immutable culture, and promotes the cultural unity of the Japanese. Over the last two centuries, it has encompassed a broad range of ideas a ...

and

State Shinto

was Imperial Japan's ideological use of the Japanese folk religion and traditions of Shinto. The state exercised control of shrine finances and training regimes for priests to strongly encourage Shinto practices that emphasized the Emperor as ...

were closely linked. Under the Meiji regime ''

lèse majesté'' prohibited insults against the Emperor and his Imperial House, and also against some major Shinto shrines which were believed to be tied strongly to the Emperor. The government strengthened its control over religious institutions that were considered to undermine State Shinto or nationalism.

The majority of

Japanese castle

are fortresses constructed primarily of wood and stone. They evolved from the wooden stockades of earlier centuries, and came into their best-known form in the 16th century. Castles in Japan were built to guard important or strategic sites, such ...

s were

smashed and destroyed in the late 19th century in the Meiji restoration by the Japanese people and government in order to modernize and westernize Japan and break from their past feudal era of the Daimyo and Shoguns. It was only due to the

1964 Summer Olympics

The , officially the and commonly known as Tokyo 1964 ( ja, 東京1964), were an international multi-sport event held from 10 to 24 October 1964 in Tokyo, Japan. Tokyo had been awarded the organization of the 1940 Summer Olympics, but this ho ...

in Japan that cheap concrete replicas of those castles were built for tourists. The vast majority of castles in Japan today are new replicas made out of concrete. In 1959 a concrete keep was built for Nagoya castle.

During the Meiji restoration's

Shinbutsu bunri

The Japanese term indicates the separation of Shinto from Buddhism, introduced after the Meiji Restoration which separated Shinto ''kami'' from buddhas, and also Buddhist temples from Shinto shrines, which were originally amalgamated. It is a ...

, tens of thousands of Japanese Buddhist religious idols and temples were smashed and destroyed. Many statues still lie in ruins. Replica temples were rebuilt with concrete. Japan then closed and shut done tens of thousands of traditional old Shinto shrines in the

Shrine Consolidation Policy

The Shrine Consolidation Policy (''Jinja seirei'', also ''Jinja gōshi'', ''Jinja gappei'') was an effort by the Government of Meiji Japan to abolish numerous smaller Shinto shrines and consolidate their functions with larger regional shrines. In ...

and the Meiji government built the new modern

15 shrines of the Kenmu restoration as a political move to link the Meiji restoration to the Kenmu restoration for their new

State Shinto

was Imperial Japan's ideological use of the Japanese folk religion and traditions of Shinto. The state exercised control of shrine finances and training regimes for priests to strongly encourage Shinto practices that emphasized the Emperor as ...

cult.

Japanese had to look at old paintings in order to find out what the

Horyuji temple used to look like when they rebuilt it. The rebuilding was originally planned for the Shōwa era.

The Japanese used mostly concrete in 1934 to rebuild the

Togetsukyo Bridge

is a district on the western outskirts of Kyoto, Japan. It also refers to the mountain across the Ōi River, which forms a backdrop to the district. Arashiyama is a nationally designated Historic Site and Place of Scenic Beauty.

Notable t ...

, unlike the original destroyed wooden version of the bridge from 836.

Political reform

The idea of a written constitution had been a subject of heated debate within and outside of the government since the beginnings of the

Meiji government

The was the government that was formed by politicians of the Satsuma Domain and Chōshū Domain in the 1860s. The Meiji government was the early government of the Empire of Japan.

Politicians of the Meiji government were known as the Meiji o ...

. The conservative

Meiji oligarchy

The Meiji oligarchy was the new ruling class of Meiji period Japan. In Japanese, the Meiji oligarchy is called the .

The members of this class were adherents of ''kokugaku'' and believed they were the creators of a new order as grand as that est ...

viewed anything resembling

democracy

Democracy (From grc, δημοκρατία, dēmokratía, ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which the people have the authority to deliberate and decide legislation (" direct democracy"), or to choose gov ...

or

republicanism

Republicanism is a political ideology centered on citizenship in a state organized as a republic. Historically, it emphasises the idea of self-rule and ranges from the rule of a representative minority or oligarchy to popular sovereignty. It ...

with suspicion and trepidation, and favored a gradualist approach. The

Freedom and People's Rights Movement

The (abbreviated as ) or Popular Rights Movement was a Japanese political and social movement for democracy in the 1880s. It pursued the formation of an elected legislature, revision of the Unequal Treaties with the United States and European c ...

demanded the immediate establishment of an elected

national assembly

In politics, a national assembly is either a unicameral legislature, the lower house of a bicameral legislature, or both houses of a bicameral legislature together. In the English language it generally means "an assembly composed of the repre ...

, and the promulgation of a constitution.

The constitution recognized the need for change and modernization after the removal of the

shogunate

, officially , was the title of the military dictators of Japan during most of the period spanning from 1185 to 1868. Nominally appointed by the Emperor, shoguns were usually the de facto rulers of the country, though during part of the Kamakur ...

:

We, the Successor to the prosperous Throne of Our Predecessors, do humbly and solemnly swear to the Imperial Founder of Our House and to Our other Imperial Ancestors that, in pursuance of a great policy co-extensive with the Heavens and with the Earth, We shall maintain and secure from decline the ancient form of government. ... In consideration of the progressive tendency of the course of human affairs and in parallel with the advance of civilization, We deem it expedient, in order to give clearness and distinctness to the instructions bequeathed by the Imperial Founder of Our House and by Our other Imperial Ancestors, to establish fundamental laws. ...

Imperial Japan was founded, ''

de jure

In law and government, ''de jure'' ( ; , "by law") describes practices that are legally recognized, regardless of whether the practice exists in reality. In contrast, ("in fact") describes situations that exist in reality, even if not legally ...

'', after the 1889 signing of

Constitution of the Empire of Japan

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan (Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in for ...

. The constitution formalized much of the Empire's political structure and gave many responsibilities and powers to the Emperor.

*Article 1. The Empire of Japan shall be reigned over and governed by a line of Emperors unbroken for ages eternal.

*Article 2. The Imperial Throne shall be succeeded to by Imperial male descendants, according to the provisions of the Imperial House Law.

*Article 3. The Emperor is sacred and inviolable.

*Article 4. The Emperor is the head of the Empire, combining in Himself the rights of sovereignty, and exercises them, according to the provisions of the present Constitution.

*Article 5. The Emperor exercises the legislative power with the consent of the Imperial Diet.

*Article 6. The Emperor gives sanction to laws, and orders them to be promulgated and executed.

*Article 7. The Emperor convokes the Imperial Diet, opens, closes and prorogues it, and dissolves the House of Representatives.

*Article 11. The Emperor has the supreme command of the Army and Navy.

*Article 13. The Emperor declares war, makes peace, and concludes treaties.

In 1890, the

Imperial Diet was established in response to the

Meiji Constitution

The Constitution of the Empire of Japan (Kyūjitai: ; Shinjitai: , ), known informally as the Meiji Constitution (, ''Meiji Kenpō''), was the constitution of the Empire of Japan which was proclaimed on February 11, 1889, and remained in for ...

. The Diet consisted of the

House of Representatives of Japan

The is the lower house of the National Diet of Japan. The House of Councillors (Japan), House of Councillors is the upper house.

The composition of the House is established by and of the Constitution of Japan. The House of Representatives ha ...

and the

House of Peers. Both houses opened seats for colonial people as well as Japanese. The Imperial Diet continued until 1947.

[

]

Economic development

The process of modernization was closely monitored and heavily subsidized by the Meiji government in close connection with a powerful clique of companies known as ''

The process of modernization was closely monitored and heavily subsidized by the Meiji government in close connection with a powerful clique of companies known as ''zaibatsu

is a Japanese language, Japanese term referring to industrial and financial vertical integration, vertically integrated business conglomerate (company), conglomerates in the Empire of Japan, whose influence and size allowed control over signi ...

'' (e.g.: Mitsui

is one of the largest '' keiretsu'' in Japan and one of the largest corporate groups in the world.

The major companies of the group include Mitsui & Co. ( general trading company), Sumitomo Mitsui Banking Corporation, Nippon Paper Industri ...

and Mitsubishi

The is a group of autonomous Japanese multinational companies in a variety of industries.

Founded by Yatarō Iwasaki in 1870, the Mitsubishi Group historically descended from the Mitsubishi zaibatsu, a unified company which existed from 1870 ...

). Borrowing and adapting technology from the West, Japan gradually took control of much of Asia's market for manufactured goods, beginning with textiles

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

. The economic structure became very mercantilistic, importing raw materials and exporting finished products — a reflection of Japan's relative scarcity of raw materials.

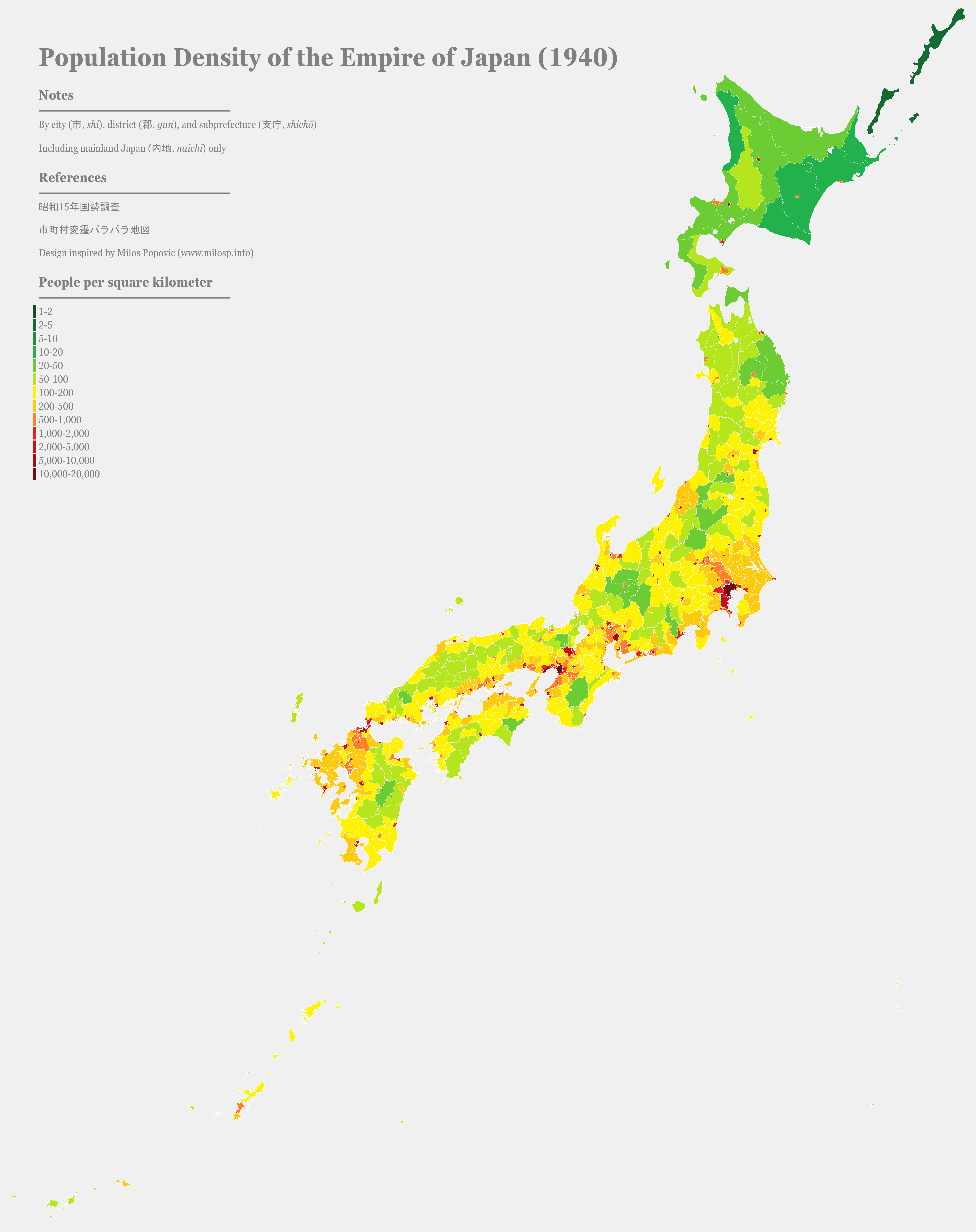

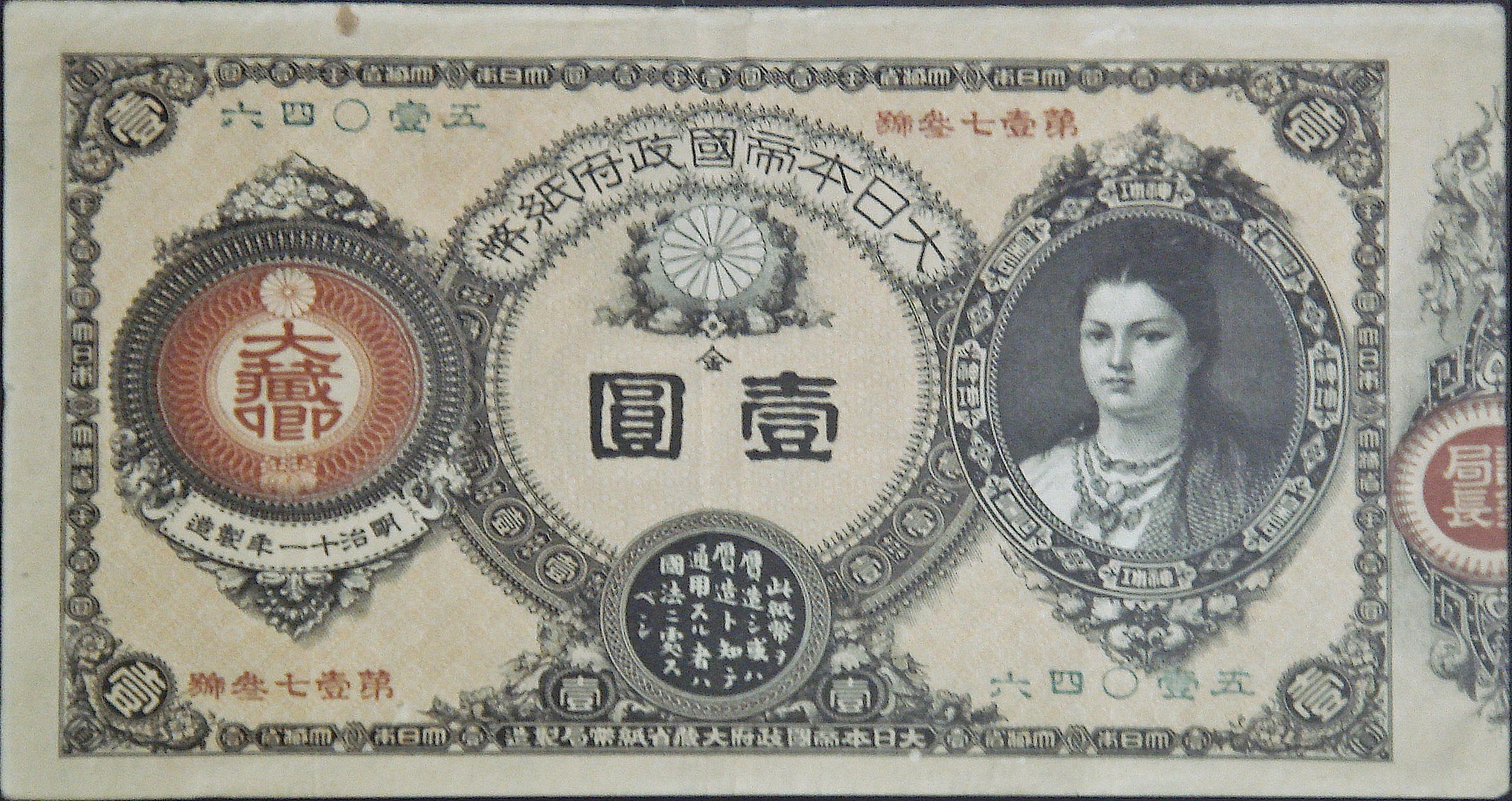

Economic reforms included a unified modern currency based on the yen

The is the official currency of Japan. It is the third-most traded currency in the foreign exchange market, after the United States dollar (US$) and the euro. It is also widely used as a third reserve currency after the US dollar and the e ...

, banking, commercial and tax laws, stock exchanges, and a communications network. The government was initially involved in economic modernization, providing a number of "model factories" to facilitate the transition to the modern period. The transition took time. By the 1890s, however, the Meiji had successfully established a modern institutional framework that would transform Japan into an advanced capitalist economy. By this time, the government had largely relinquished direct control of the modernization process, primarily for budgetary reasons. Many of the former ''daimyō

were powerful Japanese magnates, feudal lords who, from the 10th century to the early Meiji era, Meiji period in the middle 19th century, ruled most of Japan from their vast, hereditary land holdings. They were subordinate to the shogun and n ...

s'', whose pensions had been paid in a lump sum, benefited greatly through investments they made in emerging industries.

Japan emerged from the Tokugawa-Meiji transition as an industrialized nation. From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. Rapid growth and structural change characterized Japan's two periods of economic development after 1868. Initially, the economy grew only moderately and relied heavily on traditional Japanese agriculture to finance modern industrial infrastructure. By the time the

Japan emerged from the Tokugawa-Meiji transition as an industrialized nation. From the onset, the Meiji rulers embraced the concept of a market economy and adopted British and North American forms of free enterprise capitalism. Rapid growth and structural change characterized Japan's two periods of economic development after 1868. Initially, the economy grew only moderately and relied heavily on traditional Japanese agriculture to finance modern industrial infrastructure. By the time the Russo-Japanese War

The Russo-Japanese War ( ja, 日露戦争, Nichiro sensō, Japanese-Russian War; russian: Ру́сско-япóнская войнá, Rússko-yapónskaya voyná) was fought between the Empire of Japan and the Russian Empire during 1904 and 1 ...

began in 1904, 65% of employment and 38% of the gross domestic product

Gross domestic product (GDP) is a money, monetary Measurement in economics, measure of the market value of all the final goods and services produced and sold (not resold) in a specific time period by countries. Due to its complex and subjec ...

(GDP) were still based on agriculture, but modern industry had begun to expand substantially. By the late 1920s, manufacturing and mining amounted to 34% of GDP, compared with 20% for all of agriculture. Transportation and communications developed to sustain heavy industrial development.

From 1894, Japan built an extensive empire that included Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

, Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic o ...

, Manchuria

Manchuria is an exonym (derived from the endo demonym " Manchu") for a historical and geographic region in Northeast Asia encompassing the entirety of present-day Northeast China (Inner Manchuria) and parts of the Russian Far East (Outer Manc ...

, and parts of northern China

Northern China () and Southern China () are two approximate regions within China. The exact boundary between these two regions is not precisely defined and only serve to depict where there appears to be regional differences between the climate ...

. The Japanese regarded this sphere of influence

In the field of international relations, a sphere of influence (SOI) is a spatial region or concept division over which a state or organization has a level of cultural, economic, military or political exclusivity.

While there may be a formal al ...

as a political and economic necessity, which prevented foreign states from strangling Japan by blocking its access to raw materials and crucial sea-lanes. Japan's large military force was regarded as essential to the empire's defense and prosperity by obtaining natural resources that the Japanese islands lacked.

First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War

The First Sino-Japanese War (25 July 1894 – 17 April 1895) was a conflict between China and Japan primarily over influence in Korea. After more than six months of unbroken successes by Japanese land and naval forces and the loss of the po ...

, fought in 1894 and 1895, revolved around the issue of control and influence over Korea under the rule of the Joseon Dynasty

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and re ...

. Korea had traditionally been a tributary state

A tributary state is a term for a pre-modern state in a particular type of subordinate relationship to a more powerful state which involved the sending of a regular token of submission, or tribute, to the superior power (the suzerain). This tok ...

of China's Qing Empire

The Qing dynasty ( ), officially the Great Qing,, was a Manchu-led imperial dynasty of China and the last orthodox dynasty in Chinese history. It emerged from the Later Jin dynasty founded by the Jianzhou Jurchens, a Tungusic-speak ...

, which exerted large influence over the conservative Korean officials who gathered around the royal family of the Joseon

Joseon (; ; Middle Korean: 됴ᇢ〯션〮 Dyǒw syéon or 됴ᇢ〯션〯 Dyǒw syěon), officially the Great Joseon (; ), was the last dynastic kingdom of Korea, lasting just over 500 years. It was founded by Yi Seong-gye in July 1392 and re ...

kingdom. On February 27, 1876, after several confrontations between Korean isolationists and the Japanese, Japan imposed the Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876

The Japan–Korea Treaty of 1876 (also known as the Japan-Korea Treaty of Amity in Japan and the Treaty of Ganghwa Island in Korea) was made between representatives of the Empire of Japan and the Korean Kingdom of Joseon in 1876.Chung, Young-l ...

, forcing Korea open to Japanese trade. The act blocks any other power from dominating Korea, resolving to end the centuries-old Chinese suzerainty

Suzerainty () is the rights and obligations of a person, state or other polity who controls the foreign policy and relations of a tributary state, while allowing the tributary state to have internal autonomy. While the subordinate party is cal ...

.

On June 4, 1894, Korea requested aid from the Qing Empire in suppressing the Donghak Rebellion

The Donghak Peasant Revolution (), also known as the Donghak Peasant Movement (), Donghak Rebellion, Peasant Revolt of 1894, Gabo Peasant Revolution, and a variety of other names, was an armed rebellion in Korea led by peasants and followers o ...

. The Qing government sent 2,800 troops to Korea. The Japanese countered by sending an 8,000-troop expeditionary force (the Oshima Composite Brigade) to Korea. The first 400 troops arrived on June 9 en route to Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 ...

, and 3,000 landed at Incheon

Incheon (; ; or Inch'ŏn; literally "kind river"), formerly Jemulpo or Chemulp'o (제물포) until the period after 1910, officially the Incheon Metropolitan City (인천광역시, 仁川廣域市), is a city located in northwestern South Kore ...

on June 12.Royal Palace

This is a list of royal palaces, sorted by continent.

Africa

* Abdin Palace, Cairo

* Al-Gawhara Palace, Cairo

* Koubbeh Palace, Cairo

* Tahra Palace, Cairo

* Menelik Palace

* Jubilee Palace

* Guenete Leul Palace

* Imperial Palace- Massa ...

in Seoul

Seoul (; ; ), officially known as the Seoul Special City, is the capital and largest metropolis of South Korea.Before 1972, Seoul was the ''de jure'' capital of the Democratic People's Republic of Korea (North Korea) as stated iArticle 103 ...

and, by June 25, installed a puppet government in Seoul. The new pro-Japanese Korean government granted Japan the right to expel Qing forces while Japan dispatched more troops to Korea.

China objected and war ensued. Japanese ground troops routed the Chinese forces on the

China objected and war ensued. Japanese ground troops routed the Chinese forces on the Liaodong Peninsula

The Liaodong Peninsula (also Liaotung Peninsula, ) is a peninsula in southern Liaoning province in Northeast China, and makes up the southwestern coastal half of the Liaodong region. It is located between the mouths of the Daliao River (the ...

, and nearly destroyed the Chinese navy in the Battle of the Yalu River. The Treaty of Shimonoseki

The , also known as the Treaty of Maguan () in China and in the period before and during World War II in Japan, was a treaty signed at the , Shimonoseki, Japan on April 17, 1895, between the Empire of Japan and Qing China, ending the Firs ...

was signed between Japan and China, which ceded the Liaodong Peninsula and the island of Taiwan

Taiwan, officially the Republic of China (ROC), is a country in East Asia, at the junction of the East and South China Seas in the northwestern Pacific Ocean, with the People's Republic of China (PRC) to the northwest, Japan to the nort ...

to Japan. After the peace treaty, Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

, and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

forced Japan to withdraw from Liaodong Peninsula. Soon afterward, Russia occupied the Liaodong Peninsula, built the Port Arthur fortress, and based the Russian Pacific Fleet

, image = Great emblem of the Pacific Fleet.svg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Russian Pacific Fleet Great emblem

, dates = 1731–present

, country ...

in the port. Germany occupied Jiaozhou Bay

The Jiaozhou Bay (; german: Kiautschou Bucht, ) is a bay located in the prefecture-level city of Qingdao (Tsingtau), China.

The bay has historically been romanized as Kiaochow, Kiauchau or Kiao-Chau in English and Kiautschou in German.

Geogra ...

, built Tsingtao fortress and based the German East Asia Squadron

The German East Asia Squadron (german: Kreuzergeschwader / Ostasiengeschwader) was an Imperial German Navy cruiser squadron which operated mainly in the Pacific Ocean between the mid-1890s until 1914, when it was destroyed at the Battle of the Fa ...

in this port.

Boxer Rebellion

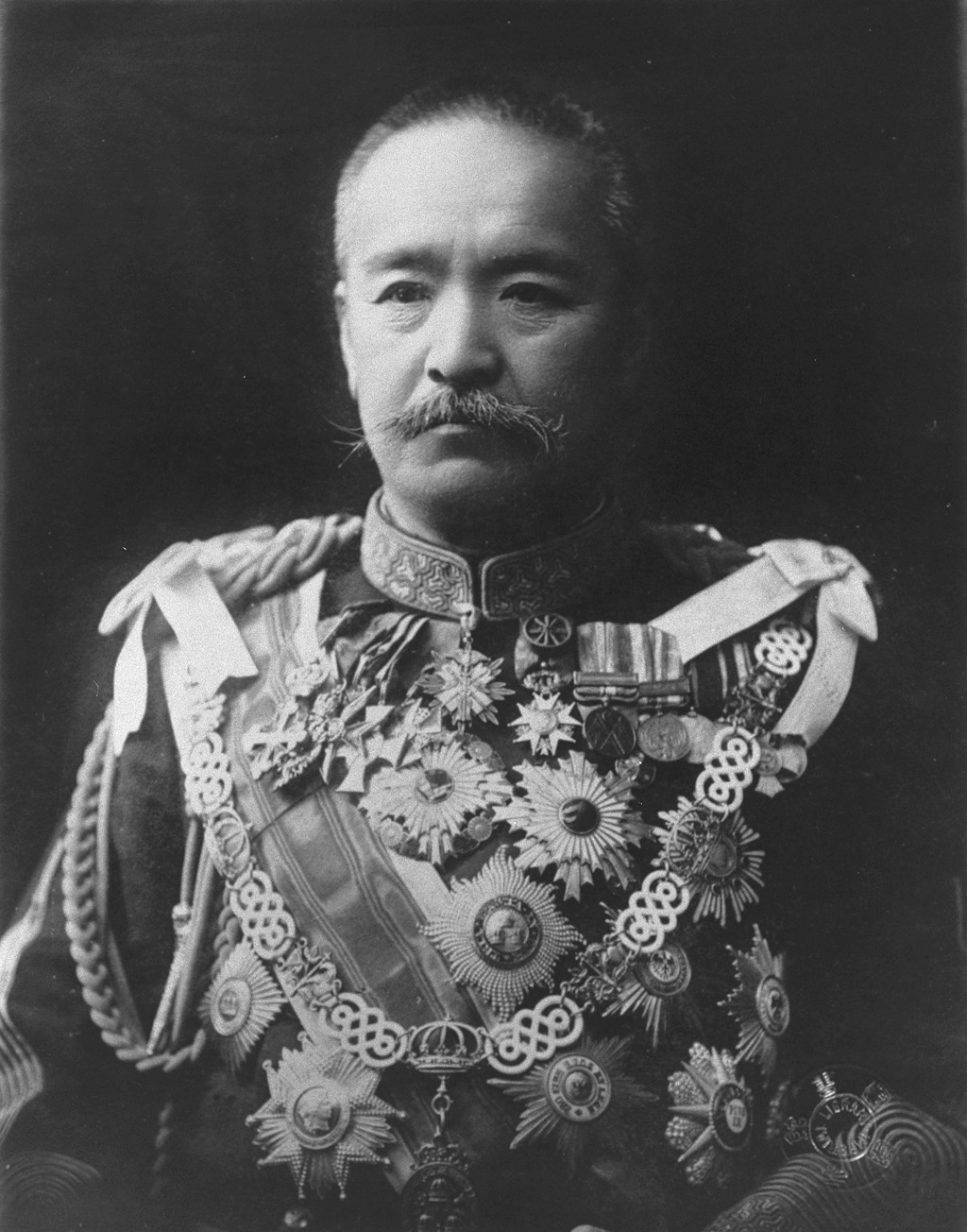

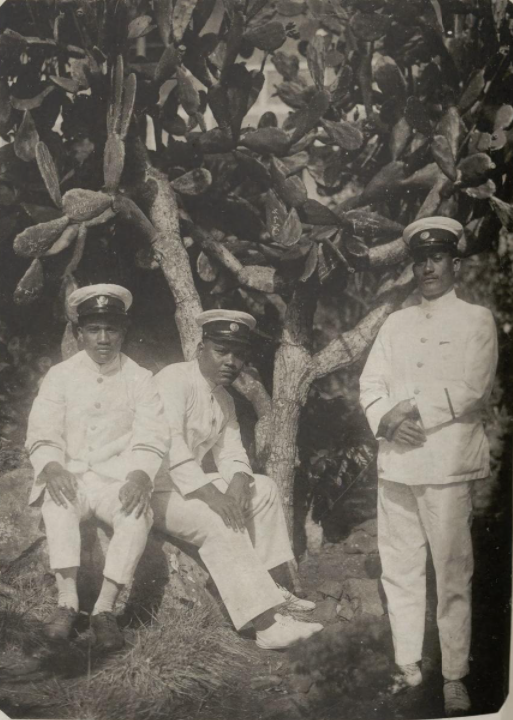

In 1900, Japan joined an international military coalition set up in response to the Boxer Rebellion in the Qing Empire of China. Japan provided the largest contingent of troops: 20,840, as well as 18 warships. Of the total, 20,300 were Imperial Japanese Army troops of the 5th Infantry Division under Lt. General Yamaguchi Motoomi; the remainder were 540 naval ''rikusentai'' (marines) from the Imperial Japanese Navy

The Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN; Kyūjitai: Shinjitai: ' 'Navy of the Greater Japanese Empire', or ''Nippon Kaigun'', 'Japanese Navy') was the navy of the Empire of Japan from 1868 to 1945, when it was dissolved following Japan's surrender ...

.

At the beginning of the Boxer Rebellion the Japanese only had 215 troops in northern China stationed at Tientsin; nearly all of them were naval ''rikusentai'' from the and the , under the command of Captain Shimamura Hayao

Marshal-Admiral Baron was a Japanese admiral during the First Sino-Japanese and Russo-Japanese Wars as well as one of the first prominent staff officers and naval strategists of the early Imperial Japanese Navy.

Biography

Born in Kōchi cit ...

. The Japanese were able to contribute 52 men to the Seymour Expedition

The Seymour Expedition was an attempt by a multi-national military force to march to Beijing and relieve the Siege of the Legations and foreign nationals from attacks by government troops and Boxers in 1900. The Chinese army and Boxer fighter ...

. On June 12, 1900, the advance of the Seymour Expedition was halted some from the capital, by mixed Boxer and Chinese regular army forces. The vastly outnumbered allies withdrew to the vicinity of Tianjin

Tianjin (; ; Mandarin: ), alternately romanized as Tientsin (), is a municipality and a coastal metropolis in Northern China on the shore of the Bohai Sea. It is one of the nine national central cities in Mainland China, with a total popul ...

, having suffered more than 300 casualties. The army general staff in Tokyo had become aware of the worsening conditions in China and had drafted ambitious contingency plans, but in the wake of the Triple Intervention

The Tripartite Intervention or was a diplomatic intervention by Russia, Germany, and France on 23 April 1895 over the harsh terms of the Treaty of Shimonoseki imposed by Japan on the Qing dynasty of China that ended the First Sino-Japanese War. ...

five years before, the government refused to deploy large numbers of troops unless requested by the western powers. However three days later, a provisional force of 1,300 troops commanded by Major General Fukushima Yasumasa

Baron was a general in the Imperial Japanese Army.

Life as a Samurai

Fukushima was born to a ''samurai'' family; his father was a retainer to the ''daimyō'' of Matsumoto, in Shinano Province (modern Nagano Prefecture). He also became a retain ...

was to be deployed to northern China. Fukushima was chosen because he spoke fluent English which enabled him to communicate with the British commander. The force landed near Tianjin on July 5.

On June 17, 1900, naval ''Rikusentai'' from the ''Kasagi'' and ''Atago'' had joined British, Russian, and German sailors to seize the Dagu forts near Tianjin. In light of the precarious situation, the British were compelled to ask Japan for additional reinforcements, as the Japanese had the only readily available forces in the region. Britain at the time was heavily engaged in the

On June 17, 1900, naval ''Rikusentai'' from the ''Kasagi'' and ''Atago'' had joined British, Russian, and German sailors to seize the Dagu forts near Tianjin. In light of the precarious situation, the British were compelled to ask Japan for additional reinforcements, as the Japanese had the only readily available forces in the region. Britain at the time was heavily engaged in the Boer War

The Second Boer War ( af, Tweede Vryheidsoorlog, , 11 October 189931 May 1902), also known as the Boer War, the Anglo–Boer War, or the South African War, was a conflict fought between the British Empire and the two Boer Republics (the Sou ...

, so a large part of the British army was tied down in South Africa. Further, deploying large numbers of troops from its garrisons in India would take too much time and weaken internal security there. Overriding personal doubts, Foreign Minister Aoki Shūzō

Viscount was a diplomat and Foreign Minister in Meiji period Japan.

Biography

Viscount Aoki was born to a ''samurai'' family as son of the Chōshū domain's physician in what is now part of Sanyō Onoda in Yamaguchi Prefecture). He studied we ...