Jane Austen (biography) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jane Austen ( ; 16 December 1775 – 18 July 1817) was an English novelist known primarily for her six novels, which implicitly interpret, critique, and comment upon the British

George Austen (1731–1805), served as the

George Austen (1731–1805), served as the

In 1768, the family finally took up residence in Steventon.

In 1768, the family finally took up residence in Steventon.

In 1783, Austen and her sister Cassandra were sent to

In 1783, Austen and her sister Cassandra were sent to

Among these works is a satirical novel in letters titled ''

Among these works is a satirical novel in letters titled ''

When Austen was twenty, Tom Lefroy, a neighbour, visited Steventon from December 1795 to January 1796. He had just finished a university degree and was moving to London for training as a

When Austen was twenty, Tom Lefroy, a neighbour, visited Steventon from December 1795 to January 1796. He had just finished a university degree and was moving to London for training as a

In December 1800, George Austen unexpectedly announced his decision to retire from the ministry, leave Steventon, and move the family to 4,

In December 1800, George Austen unexpectedly announced his decision to retire from the ministry, leave Steventon, and move the family to 4,  The years from 1801 to 1804 are something of a blank space for Austen scholars as Cassandra destroyed all of her letters from her sister in this period for unknown reasons.Halperin (1985), 729 In December 1802, Austen received her only known proposal of marriage. She and her sister visited Alethea and Catherine Bigg, old friends who lived near

The years from 1801 to 1804 are something of a blank space for Austen scholars as Cassandra destroyed all of her letters from her sister in this period for unknown reasons.Halperin (1985), 729 In December 1802, Austen received her only known proposal of marriage. She and her sister visited Alethea and Catherine Bigg, old friends who lived near  In 1804, while living in Bath, Austen started, but did not complete, her novel ''The Watsons''. The story centres on an invalid and impoverished clergyman and his four unmarried daughters. Sutherland describes the novel as "a study in the harsh economic realities of dependent women's lives". Honan suggests, and Tomalin agrees, that Austen chose to stop work on the novel after her father died on 21 January 1805 and her personal circumstances resembled those of her characters too closely for her comfort.

Her father's relatively sudden death left Jane, Cassandra, and their mother in a precarious financial situation. Edward, James, Henry, and Francis Austen (known as Frank) pledged to make annual contributions to support their mother and sisters. For the next four years, the family's living arrangements reflected their financial insecurity. They spent part of the time in rented quarters in Bath before leaving the city in June 1805 for a family visit to Steventon and

In 1804, while living in Bath, Austen started, but did not complete, her novel ''The Watsons''. The story centres on an invalid and impoverished clergyman and his four unmarried daughters. Sutherland describes the novel as "a study in the harsh economic realities of dependent women's lives". Honan suggests, and Tomalin agrees, that Austen chose to stop work on the novel after her father died on 21 January 1805 and her personal circumstances resembled those of her characters too closely for her comfort.

Her father's relatively sudden death left Jane, Cassandra, and their mother in a precarious financial situation. Edward, James, Henry, and Francis Austen (known as Frank) pledged to make annual contributions to support their mother and sisters. For the next four years, the family's living arrangements reflected their financial insecurity. They spent part of the time in rented quarters in Bath before leaving the city in June 1805 for a family visit to Steventon and

Around early 1809, Austen's brother Edward offered his mother and sisters a more settled life—the use of a large cottage in

Around early 1809, Austen's brother Edward offered his mother and sisters a more settled life—the use of a large cottage in

Reviews were favourable and the novel became fashionable among young aristocratic opinion-makers;Honan (1987), 289–290. the edition sold out by mid-1813. Austen's novels were published in larger editions than was normal for this period. The small size of the novel-reading public and the large costs associated with hand production (particularly the cost of handmade paper) meant that most novels were published in editions of 500 copies or fewer to reduce the risks to the publisher and the novelist. Even some of the most successful titles during this period were issued in editions of not more than 750 or 800 copies and later reprinted if demand continued. Austen's novels were published in larger editions, ranging from about 750 copies of ''Sense and Sensibility'' to about 2,000 copies of ''Emma''. It is not clear whether the decision to print more copies than usual of Austen's novels was driven by the publishers or the author. Since all but one of Austen's books were originally published "on commission", the risks of overproduction were largely hers (or Cassandra's after her death) and publishers may have been more willing to produce larger editions than was normal practice when their own funds were at risk. Editions of popular works of non-fiction were often much larger.

Austen made £140 () from ''Sense and Sensibility'', which provided her with some financial and psychological independence. After the success of ''Sense and Sensibility'', all of Austen's subsequent books were billed as written "By the author of ''Sense and Sensibility''" and Austen's name never appeared on her books during her lifetime. Egerton then published ''

Reviews were favourable and the novel became fashionable among young aristocratic opinion-makers;Honan (1987), 289–290. the edition sold out by mid-1813. Austen's novels were published in larger editions than was normal for this period. The small size of the novel-reading public and the large costs associated with hand production (particularly the cost of handmade paper) meant that most novels were published in editions of 500 copies or fewer to reduce the risks to the publisher and the novelist. Even some of the most successful titles during this period were issued in editions of not more than 750 or 800 copies and later reprinted if demand continued. Austen's novels were published in larger editions, ranging from about 750 copies of ''Sense and Sensibility'' to about 2,000 copies of ''Emma''. It is not clear whether the decision to print more copies than usual of Austen's novels was driven by the publishers or the author. Since all but one of Austen's books were originally published "on commission", the risks of overproduction were largely hers (or Cassandra's after her death) and publishers may have been more willing to produce larger editions than was normal practice when their own funds were at risk. Editions of popular works of non-fiction were often much larger.

Austen made £140 () from ''Sense and Sensibility'', which provided her with some financial and psychological independence. After the success of ''Sense and Sensibility'', all of Austen's subsequent books were billed as written "By the author of ''Sense and Sensibility''" and Austen's name never appeared on her books during her lifetime. Egerton then published ''

Austen was feeling unwell by early 1816, but ignored the warning signs. By the middle of that year, her decline was unmistakable, and she began a slow, irregular deterioration. The majority of biographers rely on

Austen was feeling unwell by early 1816, but ignored the warning signs. By the middle of that year, her decline was unmistakable, and she began a slow, irregular deterioration. The majority of biographers rely on

As Austen's works were published anonymously, they brought her little personal renown. They were fashionable among opinion-makers, but were rarely reviewed. Most of the reviews were short and on balance favourable, although superficial and cautious,Southam (1968), 1. most often focused on the moral lessons of the novels.

Sir

As Austen's works were published anonymously, they brought her little personal renown. They were fashionable among opinion-makers, but were rarely reviewed. Most of the reviews were short and on balance favourable, although superficial and cautious,Southam (1968), 1. most often focused on the moral lessons of the novels.

Sir

Because Austen's novels did not conform to Romantic and Victorian expectations that "powerful emotion eauthenticated by an egregious display of sound and colour in the writing", some 19th-century critics preferred the works of

Because Austen's novels did not conform to Romantic and Victorian expectations that "powerful emotion eauthenticated by an egregious display of sound and colour in the writing", some 19th-century critics preferred the works of

Austen's works have attracted legions of scholars. The first dissertation on Austen was published in 1883, by George Pellew, a student at Harvard University. Another early academic analysis came from a 1911 essay by Oxford Shakespearean scholar

Austen's works have attracted legions of scholars. The first dissertation on Austen was published in 1883, by George Pellew, a student at Harvard University. Another early academic analysis came from a 1911 essay by Oxford Shakespearean scholar

In 2013, Austen's works featured on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the

In 2013, Austen's works featured on a series of UK postage stamps issued by the

"World first' statue of Jane Austen unveiled"

CNN. 18 July 2017.

Jane Austen's Fiction Manuscripts Digital Edition

a

''A Memoir of Jane Austen''

by James Edward Austen-Leigh

Jane Austen

at the

Jane Austen's House Museum

in

The Jane Austen Centre

in

The Republic of Pemberley

The Jane Austen Society of North America

The Jane Austen Society of the United Kingdom

{{DEFAULTSORT:Austen, Jane 1775 births 1817 deaths 18th-century English novelists 18th-century English writers 18th-century English women writers 19th-century deaths from tuberculosis 19th-century English novelists 19th-century English writers 19th-century English women writers Anglican writers Austen family Burials at Winchester Cathedral Culture in Bath, Somerset English Anglicans English romantic fiction writers English women novelists History of Bath, Somerset People from Chawton People from Deane, Hampshire People from Steventon, Hampshire Tuberculosis deaths in England Women of the Regency era Women romantic fiction writers Writers of Gothic fiction

landed gentry

The landed gentry, or the ''gentry'', is a largely historical British social class of landowners who could live entirely from rental income, or at least had a country estate. While distinct from, and socially below, the British peerage, th ...

at the end of the 18th century. Austen's plots often explore the dependence of women on marriage for the pursuit of favourable social standing and economic security. Her works are an implicit critique of the novels of sensibility of the second half of the 18th century and are part of the transition to 19th-century literary realism

Literary realism is a literary genre, part of the broader realism in arts, that attempts to represent subject-matter truthfully, avoiding speculative fiction and supernatural elements. It originated with the realist art movement that began with ...

. Her deft use of social commentary, realism and biting irony have earned her acclaim among critics and scholars.

The anonymously published ''Sense and Sensibility

''Sense and Sensibility'' is a novel by Jane Austen, published in 1811. It was published anonymously; ''By A Lady'' appears on the title page where the author's name might have been. It tells the story of the Dashwood sisters, Elinor (age 19) a ...

'' (1811), ''Pride and Prejudice

''Pride and Prejudice'' is an 1813 novel of manners by Jane Austen. The novel follows the character development of Elizabeth Bennet, the dynamic protagonist of the book who learns about the repercussions of hasty judgments and comes to appreci ...

'' (1813), ''Mansfield Park

''Mansfield Park'' is the third published novel by Jane Austen, first published in 1814 by Thomas Egerton. A second edition was published in 1816 by John Murray, still within Austen's lifetime. The novel did not receive any public reviews unt ...

'' (1814), and ''Emma

Emma may refer to:

* Emma (given name)

Film

* Emma (1932 film), ''Emma'' (1932 film), a comedy-drama film by Clarence Brown

* Emma (1996 theatrical film), ''Emma'' (1996 theatrical film), a film starring Gwyneth Paltrow

* Emma (1996 TV film), '' ...

'' (1816), were a modest success but brought her little fame in her lifetime. She wrote two other novels—''Northanger Abbey

''Northanger Abbey'' () is a coming-of-age

Coming of age is a young person's transition from being a child to being an adult. The specific age at which this transition takes place varies between societies, as does the nature of the ...

'' and ''Persuasion

Persuasion or persuasion arts is an umbrella term for Social influence, influence. Persuasion can influence a person's Belief, beliefs, Attitude (psychology), attitudes, Intention, intentions, Motivation, motivations, or Behavior, behaviours.

...

'', both published posthumously in 1817—and began another, eventually titled ''Sanditon

''Sanditon'' (1817) is an unfinished novel by the English writer Jane Austen. In January 1817, Austen began work on a new novel she called ''The Brothers'', later titled ''Sanditon'', and completed eleven chapters before stopping work in mid-M ...

'', but died before its completion. She also left behind three volumes of juvenile writings in manuscript, the short epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of letters. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and sometimes considered ...

''Lady Susan

''Lady Susan'' is an epistolary novella by Jane Austen, possibly written in 1794 but not published until 1871.

This early complete work, which the author never submitted for publication, describes the schemes of the title character.

Synopsis

...

'', and the unfinished novel ''The Watsons

''The Watsons'' is an abandoned novel by Jane Austen, probably begun about 1803. There have been a number of arguments advanced as to why she did not complete it, and other authors have since attempted the task. A continuation by Austen's niece ...

''.

Since her death Austen's novels have rarely been out of print. A significant transition in her reputation occurred in 1833, when they were republished in Richard Bentley

Richard Bentley FRS (; 27 January 1662 – 14 July 1742) was an English classical scholar, critic, and theologian. Considered the "founder of historical philology", Bentley is widely credited with establishing the English school of Hellen ...

's Standard Novels series (illustrated by Ferdinand Pickering and sold as a set). They gradually gained wide acclaim and popular readership. In 1869, fifty-two years after her death, her nephew's publication of ''A Memoir of Jane Austen

''A Memoir of Jane Austen'' is a biography of the novelist Jane Austen (1775–1817) published in 1869 by her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh. A second edition was published in 1871 which included previously unpublished Jane Austen writings. ...

'' introduced a compelling version of her writing career and supposedly uneventful life to an eager audience.

Her work has inspired a large number of critical essays and has been included in many literary anthologies. Her novels have also inspired many films, including 1940's ''Pride and Prejudice

''Pride and Prejudice'' is an 1813 novel of manners by Jane Austen. The novel follows the character development of Elizabeth Bennet, the dynamic protagonist of the book who learns about the repercussions of hasty judgments and comes to appreci ...

'', 1995's ''Sense and Sensibility

''Sense and Sensibility'' is a novel by Jane Austen, published in 1811. It was published anonymously; ''By A Lady'' appears on the title page where the author's name might have been. It tells the story of the Dashwood sisters, Elinor (age 19) a ...

'' and 2016's ''Love & Friendship

''Love & Friendship'' is a 2016 period comedy film written and directed by Whit Stillman. Based on Jane Austen's epistolary novel ''Lady Susan'', written c. 1794, the film stars Kate Beckinsale, Chloë Sevigny, Xavier Samuel, and Emma Greenwel ...

''.

Biographical sources

The scant biographical information about Austen comes from her few surviving letters and sketches her family members wrote about her.Fergus (2005), 3–4 Only about 160 of the approximately 3,000 letters Austen wrote have survived and been published.Cassandra Austen

Cassandra Elizabeth Austen (9 January 1773 – 22 March 1845Cassandra Austen

". (n.d. ...

destroyed the bulk of the letters she received from her sister, burning or otherwise destroying them. She wanted to ensure that the "younger nieces did not read any of Jane's sometimes acid or forthright comments on neighbours or family members".Le Faye (2005), 33 In the interest of protecting reputations from Jane's penchant for honesty and forthrightness, Cassandra omitted details of illnesses, unhappiness and anything she considered unsavoury. Important details about the Austen family were elided by intention, such as any mention of Austen's brother George, whose undiagnosed developmental challenges led the family to send him away from home; the two brothers sent away to the navy at an early age; or wealthy Aunt Leigh-Perrot, arrested and tried on charges of larceny.

The first Austen biography was ". (n.d. ...

Henry Thomas Austen

Henry Thomas Austen (8 June 1771 – 12 March 1850) was a militia officer, clergyman, banker and the brother of the novelist Jane Austen.Grey, David J. "Henry Austen: Jane Austen's "Perpetual Sunshine"." ''Persuasions Occasional Papers'', No. 1, ...

's 1818 "Biographical Notice". It appeared in a posthumous edition of ''Northanger Abbey

''Northanger Abbey'' () is a coming-of-age

Coming of age is a young person's transition from being a child to being an adult. The specific age at which this transition takes place varies between societies, as does the nature of the ...

'' and included extracts from two letters, against the judgement of other family members. Details of Austen's life continued to be omitted or embellished in her nephew's ''A Memoir of Jane Austen

''A Memoir of Jane Austen'' is a biography of the novelist Jane Austen (1775–1817) published in 1869 by her nephew James Edward Austen-Leigh. A second edition was published in 1871 which included previously unpublished Jane Austen writings. ...

'', published in 1869, and in William and Richard Arthur Austen-Leigh's biography ''Jane Austen: Her Life and Letters'', published in 1913, all of which included additional letters. Austen's family and relatives built a legend of "good quiet Aunt Jane", portraying her as a woman in a happy domestic situation, whose family was the mainstay of her life. Modern biographers include details excised from the letters and family biographies, but the biographer Jan Fergus writes that the challenge is to keep the view balanced, not to present her languishing in periods of deep unhappiness as "an embittered, disappointed woman trapped in a thoroughly unpleasant family".

Life

Family

Jane Austen was born inSteventon, Hampshire

Steventon is a village and a civil parish with a population of about 250 in north Hampshire, England. Situated 7 miles south-west of the town of Basingstoke, between the villages of Overton, Hampshire, Overton, Oakley, Hampshire, Oakley and North ...

, on 16 December 1775 in a harsh winter. Her father wrote of her arrival in a letter that her mother "certainly expected to have been brought to bed a month ago". He added that the newborn infant was "a present plaything for Cassy and a future companion".Le Faye (2004), 27 The winter of 1776 was particularly harsh and it was not until 5 April that she was baptised at the local church with the single name Jane.

George Austen (1731–1805), served as the

George Austen (1731–1805), served as the rector

Rector (Latin for the member of a vessel's crew who steers) may refer to:

Style or title

*Rector (ecclesiastical), a cleric who functions as an administrative leader in some Christian denominations

*Rector (academia), a senior official in an edu ...

of the Anglican parishes of Steventon and Deane. The Reverend Austen came from an old and wealthy family of wool merchants. As each generation of eldest sons received inheritances, George's branch of the family fell into poverty. He and his two sisters were orphaned as children, and had to be taken in by relatives. In 1745, at the age of fifteen, George Austen's sister Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

was apprenticed to a milliner

Hat-making or millinery is the design, manufacture and sale of hats and other headwear. A person engaged in this trade is called a milliner or hatter.

Historically, milliners, typically women shopkeepers, produced or imported an inventory of g ...

in Covent Garden

Covent Garden is a district in London, on the eastern fringes of the West End, between St Martin's Lane and Drury Lane. It is associated with the former fruit-and-vegetable market in the central square, now a popular shopping and tourist si ...

. At the age of sixteen, George entered St John's College, Oxford

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Oxford. Founded as a men's college in 1555, it has been coeducational since 1979.Communication from Michael Riordan, college archivist Its founder, Sir Thomas White, intended to pro ...

, where he most likely met Cassandra Leigh (1739–1827). She came from the prominent Leigh family. Her father was rector at All Souls College, Oxford

All Souls College (official name: College of the Souls of All the Faithful Departed) is a constituent college of the University of Oxford in England. Unique to All Souls, all of its members automatically become fellows (i.e., full members of t ...

, where she grew up among the gentry. Her eldest brother James inherited a fortune and large estate from his great-aunt Perrot, with the only condition that he change his name to Leigh-Perrot.

George Austen and Cassandra Leigh were engaged, probably around 1763, when they exchanged miniatures. He received the living

Living or The Living may refer to:

Common meanings

*Life, a condition that distinguishes organisms from inorganic objects and dead organisms

** Living species, one that is not extinct

*Personal life, the course of an individual human's life

* Hu ...

of the Steventon parish from Thomas Knight, the wealthy husband of his second cousin. They married on 26 April 1764 at St Swithin's Church in Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, by license

A license (or licence) is an official permission or permit to do, use, or own something (as well as the document of that permission or permit).

A license is granted by a party (licensor) to another party (licensee) as an element of an agreeme ...

, in a simple ceremony, two months after Cassandra's father died. Their income was modest, with George's small ''per annum'' living; Cassandra brought to the marriage the expectation of a small inheritance at the time of her mother's death.

After the living at the nearby Deane rectory had been purchased for George by his wealthy uncle Francis Austen, the Austens took up temporary residence there, until Steventon rectory, a 16th-century house in disrepair, underwent necessary renovations. Cassandra gave birth to three children while living at Deane: James

James is a common English language surname and given name:

*James (name), the typically masculine first name James

* James (surname), various people with the last name James

James or James City may also refer to:

People

* King James (disambiguat ...

in 1765, George in 1766, and Edward

Edward is an English given name. It is derived from the Anglo-Saxon name ''Ēadweard'', composed of the elements '' ēad'' "wealth, fortune; prosperous" and '' weard'' "guardian, protector”.

History

The name Edward was very popular in Anglo-Sa ...

in 1767. Her custom was to keep an infant at home for several months and then place it with Elizabeth Littlewood, a woman living nearby to nurse

Nursing is a profession within the health care sector focused on the care of individuals, families, and communities so they may attain, maintain, or recover optimal health and quality of life. Nurses may be differentiated from other health c ...

and raise for twelve to eighteen months.

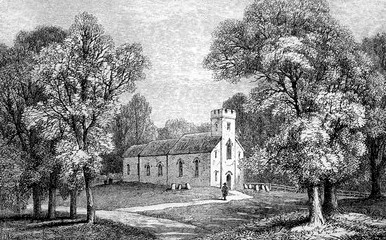

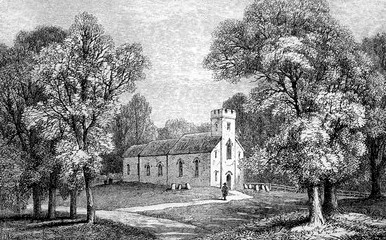

Steventon

In 1768, the family finally took up residence in Steventon.

In 1768, the family finally took up residence in Steventon. Henry

Henry may refer to:

People

*Henry (given name)

*Henry (surname)

* Henry Lau, Canadian singer and musician who performs under the mononym Henry

Royalty

* Portuguese royalty

** King-Cardinal Henry, King of Portugal

** Henry, Count of Portugal, ...

was the first child to be born there, in 1771. At about this time, Cassandra could no longer ignore the signs that little George was developmentally disabled. He was subject to seizures, may have been deaf and mute, and she chose to send him out to be fostered. In 1773, Cassandra

Cassandra or Kassandra (; Ancient Greek: Κασσάνδρα, , also , and sometimes referred to as Alexandra) in Greek mythology was a Trojan priestess dedicated to the god Apollo and fated by him to utter true prophecies but never to be believe ...

was born, followed by Francis

Francis may refer to:

People

*Pope Francis, the head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State and Bishop of Rome

*Francis (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters

*Francis (surname)

Places

* Rural M ...

in 1774, and Jane in 1775.

According to biographer Park Honan

Leonard Hobart Park Honan (17 September 1928 – 27 September 2014) was an American academic and author who spent most of his career in the UK. He wrote widely on the lives of authors and poets and published important biographies of such writers as ...

, the atmosphere of the Austen home was an "open, amused, easy intellectual" one, where the ideas of those with whom the Austens might disagree politically or socially were considered and discussed.

The family relied on the patronage of their kin and hosted visits from numerous family members.Todd (2015), 4 Mrs Austen spent the summer of 1770 in London with George's sister, Philadelphia, and her daughter Eliza

ELIZA is an early natural language processing computer program created from 1964 to 1966 at the MIT Artificial Intelligence Laboratory by Joseph Weizenbaum. Created to demonstrate the superficiality of communication between humans and machines, E ...

, accompanied by his other sister, Mrs Walter and her daughter Philly. Philadelphia and Eliza Hancock were, according to Le Faye, "the bright comets flashing into an otherwise placid solar system of clerical life in rural Hampshire

Hampshire (, ; abbreviated to Hants) is a ceremonial county, ceremonial and non-metropolitan county, non-metropolitan counties of England, county in western South East England on the coast of the English Channel. Home to two major English citi ...

, and the news of their foreign travels and fashionable London life, together with their sudden descents upon the Steventon household in between times, all helped to widen Jane's youthful horizon and influence her later life and works."

Cassandra Austen's cousin Thomas Leigh visited a number of times in the 1770s and 1780s, inviting young Cassie to visit them in Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

in 1781. The first mention of Jane occurs in family documents upon her return, "... and almost home they were when they met Jane & Charles, the two little ones of the family, who had to go as far as New Down to meet the chaise

A one-horse chaise

A three-wheeled "Handchaise", Germany, around 1900, designed to be pushed by a person

A chaise, sometimes called chay or shay, is a light two- or four-wheeled traveling or pleasure carriage for one or two people with a folding ...

, & have the pleasure of riding home in it." Le Faye writes that "Mr Austen's predictions for his younger daughter were fully justified. Never were sisters more to each other than Cassandra and Jane; while in a particularly affectionate family, there seems to have been a special link between Cassandra and Edward on the one hand, and between Henry and Jane on the other."

From 1773 until 1796, George Austen supplemented his income by farming and by teaching three or four boys at a time, who boarded at his home. The Reverend Austen had an annual income of £200 () from his two livings.Irvine (2005) p.2 This was a very modest income at the time; by comparison, a skilled worker like a blacksmith or a carpenter could make about £100 annually while the typical annual income of a gentry family was between £1,000 and £5,000. Mr. Austen also rented the 200-acre Cheesedown farm from his benefactor Thomas Knight which could make a profit of £300 () a year.

During this period of her life, Jane Austen attended church regularly, socialised with friends and neighbours, and read novels—often of her own composition—aloud to her family in the evenings. Socialising with the neighbours often meant dancing, either impromptu in someone's home after supper or at the balls held regularly at the assembly rooms

In Great Britain and Ireland, especially in the 18th and 19th centuries, assembly rooms were gathering places for members of the higher social classes open to members of both sexes. At that time most entertaining was done at home and there were ...

in the town hall. Her brother Henry later said that "Jane was fond of dancing, and excelled in it".

Education

In 1783, Austen and her sister Cassandra were sent to

In 1783, Austen and her sister Cassandra were sent to Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

to be educated by Mrs Ann Cawley who took them to Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

later that year. That autumn both girls were sent home after catching typhus

Typhus, also known as typhus fever, is a group of infectious diseases that include epidemic typhus, scrub typhus, and murine typhus. Common symptoms include fever, headache, and a rash. Typically these begin one to two weeks after exposure.

...

, from which Jane Austen nearly died. She was from then home-educated, until she attended boarding school with her sister from early in 1785 at the Reading Abbey Girls' School

Reading Abbey Girls' School, also known as Reading Ladies’ Boarding School, was an educational establishment in Reading, Berkshire open from at least 1755 until 1794. Many of its pupils went on to make a mark on English culture and society, part ...

, ruled by Mrs La Tournelle. The curriculum probably included French, spelling, needlework, dancing, music and drama. The sisters returned home before December 1786 because the school fees for the two girls were too high for the Austen family. After 1786, Austen "never again lived anywhere beyond the bounds of her immediate family environment".

Her education came from reading, guided by her father and brothers James and Henry. Irene Collins

Irene Collins ( Fozzard; 16 September 1925 – 12 July 2015) was a British historian and writer, known for her studies of Napoleon and Jane Austen.

Early life and family

Irene Fozzard was born as the second of identical twins of James Frederick ...

said that Austen "used some of the same school books as the boys". Austen apparently had unfettered access both to her father's library and that of a family friend, Warren Hastings

Warren Hastings (6 December 1732 – 22 August 1818) was a British colonial administrator, who served as the first Governor of the Presidency of Fort William (Bengal), the head of the Supreme Council of Bengal, and so the first Governor-Genera ...

. Together these collections amounted to a large and varied library. Her father was also tolerant of Austen's sometimes risqué experiments in writing, and provided both sisters with expensive paper and other materials for their writing and drawing.

Private theatricals were an essential part of Austen's education. From her early childhood, the family and friends staged a series of plays in the rectory

A clergy house is the residence, or former residence, of one or more priests or ministers of religion. Residences of this type can have a variety of names, such as manse, parsonage, rectory or vicarage.

Function

A clergy house is typically ow ...

barn, including Richard Sheridan Richard Sheridan may refer to:

* Richard Bingham Sheridan (1822–1897), Australian civil servant

*Richard Brinsley Sheridan (1751–1816), Irish playwright

*Richard Brinsley Sheridan (politician) (1806–1888), Irish politician See also

*Dick Sher ...

's ''The Rivals

''The Rivals'' is a comedy of manners by Richard Brinsley Sheridan in five acts which was first performed at Covent Garden Theatre on 17 January 1775. The story has been updated frequently, including a 1935 musical and a 1958 List of Maverick ...

'' (1775) and David Garrick

David Garrick (19 February 1717 – 20 January 1779) was an English actor, playwright, theatre manager and producer who influenced nearly all aspects of European theatrical practice throughout the 18th century, and was a pupil and friend of Sa ...

's '' Bon Ton''. Austen's eldest brother James wrote the prologues and epilogues and she probably joined in these activities, first as a spectator and later as a participant. Most of the plays were comedies, which suggests how Austen's satirical gifts were cultivated. At the age of 12, she tried her own hand at dramatic writing; she wrote three short plays during her teenage years.

''Juvenilia'' (1787–1793)

From at least the time she was aged eleven, Austen wrote poems and stories to amuse herself and her family. She exaggerated mundane details of daily life and parodied common plot devices in "stories [] full of anarchic fantasies of female power, licence, illicit behaviour, and general high spirits", according to Janet Todd. Containing work written between 1787 and 1793, the juvenilia (or childhood writings) that Austen compiled fair copies consisted of twenty-nine early works into three bound notebooks, now referred to as the ''Juvenilia''. She called the three notebooks "Volume the First", "Volume the Second" and "Volume the Third", and they preserve 90,000 words she wrote during those years. The ''Juvenilia'' are often, according to scholar Richard Jenkyns, "boisterous" and "anarchic"; he compares them to the work of 18th-century novelistLaurence Sterne

Laurence Sterne (24 November 1713 – 18 March 1768), was an Anglo-Irish novelist and Anglican cleric who wrote the novels ''The Life and Opinions of Tristram Shandy, Gentleman'' and ''A Sentimental Journey Through France and Italy'', published ...

.

Among these works is a satirical novel in letters titled ''

Among these works is a satirical novel in letters titled ''Love and Freindship

is a juvenile story by Jane Austen, dated 1790. While aged 11–18, Austen wrote her tales in three notebooks. These still exist, one in the Bodleian Library and the other two in the British Museum. They contain, among other works, ''Love a ...

'' , written when aged fourteen in 1790, in which she mocked popular novels of sensibility. The next year, she wrote '' The History of England'', a manuscript of thirty-four pages accompanied by thirteen watercolour miniatures by her sister, Cassandra. Austen's ''History'' parodied popular historical writing, particularly Oliver Goldsmith

Oliver Goldsmith (10 November 1728 – 4 April 1774) was an Anglo-Irish novelist, playwright, dramatist and poet, who is best known for his novel ''The Vicar of Wakefield'' (1766), his pastoral poem ''The Deserted Village'' (1770), and his pl ...

's ''History of England'' (1764). Honan speculates that not long after writing ''Love and Freindship'', Austen decided to "write for profit, to make stories her central effort", that is, to become a professional writer. When she was around eighteen years old, Austen began to write longer, more sophisticated works.Honan (1987), 93

In August 1792, aged seventeen, Austen started ''Catharine or the Bower'', which presaged her mature work, especially ''Northanger Abbey'', but was left unfinished until picked up in ''Lady Susan

''Lady Susan'' is an epistolary novella by Jane Austen, possibly written in 1794 but not published until 1871.

This early complete work, which the author never submitted for publication, describes the schemes of the title character.

Synopsis

...

'', which Todd describes as less prefiguring than ''Catharine''. A year later she began, but abandoned, a short play, later titled ''Sir Charles Grandison or the happy Man, a comedy in 6 acts'', which she returned to and completed around 1800. This was a short parody of various school textbook abridgements of Austen's favourite contemporary novel, ''The History of Sir Charles Grandison

''The History of Sir Charles Grandison'', commonly called ''Sir Charles Grandison'', is an epistolary novel by English writer Samuel Richardson first published in February 1753. The book was a response to Henry Fielding's ''The History of Tom ...

'' (1753), by Samuel Richardson

Samuel Richardson (baptised 19 August 1689 – 4 July 1761) was an English writer and printer known for three epistolary novels: ''Pamela; or, Virtue Rewarded'' (1740), '' Clarissa: Or the History of a Young Lady'' (1748) and ''The History of ...

.

When Austen became an aunt for the first time aged eighteen, she sent new-born niece Fanny Catherine Austen Knight "five short pieces of ... the Juvenilia now known collectively as 'Scraps' .., purporting to be her 'Opinions and Admonitions on the conduct of Young Women. For Jane-Anna-Elizabeth Austen (also born in 1793), her aunt wrote "two more 'Miscellanious Morsels', dedicating them to nnaon 2 June 1793, 'convinced that if you seriously attend to them, You will derive from them very important Instructions, with regard to your Conduct in Life. There is manuscript evidence that Austen continued to work on these pieces as late as 1811 (when she was 36), and that her niece and nephew, Anna and James Edward Austen, made further additions as late as 1814.

Between 1793 and 1795 (aged eighteen to twenty), Austen wrote ''Lady Susan

''Lady Susan'' is an epistolary novella by Jane Austen, possibly written in 1794 but not published until 1871.

This early complete work, which the author never submitted for publication, describes the schemes of the title character.

Synopsis

...

'', a short epistolary novel

An epistolary novel is a novel written as a series of letters. The term is often extended to cover novels that intersperse documents of other kinds with the letters, most commonly diary entries and newspaper clippings, and sometimes considered ...

, usually described as her most ambitious and sophisticated early work. It is unlike any of Austen's other works. Austen biographer Claire Tomalin

Claire Tomalin (née Delavenay; born 20 June 1933) is an English journalist and biographer, known for her biographies of Charles Dickens, Thomas Hardy, Samuel Pepys, Jane Austen and Mary Wollstonecraft.

Early life

Tomalin was born Claire Del ...

describes the novella's heroine as a sexual predator who uses her intelligence and charm to manipulate, betray and abuse her lovers, friends and family. Tomalin writes:

Told in letters, it is as neatly plotted as a play, and as cynical in tone as any of the most outrageous of the Restoration dramatists who may have provided some of her inspiration ... It stands alone in Austen's work as a study of an adult woman whose intelligence and force of character are greater than those of anyone she encounters.According to Janet Todd, the model for the title character may have been

Eliza de Feuillide

Eliza Capot, Comtesse de Feuillide (née Hancock; 22 December 1761 – 25 April 1813) was the cousin, and later sister-in-law, of novelist Jane Austen. She is believed to have been the inspiration for a number of Austen's works, such as ''L ...

, who inspired Austen with stories of her glamorous life and various adventures. Eliza's French husband was guillotined in 1794; she married Jane's brother Henry Austen in 1797.

Tom Lefroy

When Austen was twenty, Tom Lefroy, a neighbour, visited Steventon from December 1795 to January 1796. He had just finished a university degree and was moving to London for training as a

When Austen was twenty, Tom Lefroy, a neighbour, visited Steventon from December 1795 to January 1796. He had just finished a university degree and was moving to London for training as a barrister

A barrister is a type of lawyer in common law jurisdictions. Barristers mostly specialise in courtroom advocacy and litigation. Their tasks include taking cases in superior courts and tribunals, drafting legal pleadings, researching law and ...

. Lefroy and Austen would have been introduced at a ball or other neighbourhood social gathering, and it is clear from Austen's letters to Cassandra that they spent considerable time together: "I am almost afraid to tell you how my Irish friend and I behaved. Imagine to yourself everything most profligate and shocking in the way of dancing and sitting down together."

Austen wrote in her first surviving letter to her sister Cassandra that Lefroy was a "very gentlemanlike, good-looking, pleasant young man".Halperin (1985), 721 Five days later in another letter, Austen wrote that she expected an "offer" from her "friend" and that "I shall refuse him, however, unless he promises to give away his white coat", going on to write "I will confide myself in the future to Mr Tom Lefroy, for whom I don't give a sixpence" and refuse all others. The next day, Austen wrote: "The day will come on which I flirt my last with Tom Lefroy and when you receive this it will be all over. My tears flow as I write at this melancholy idea".

Halperin cautioned that Austen often satirised popular sentimental romantic fiction in her letters, and some of the statements about Lefroy may have been ironic. However, it is clear that Austen was genuinely attracted to Lefroy and subsequently none of her other suitors ever quite measured up to him. The Lefroy family intervened and sent him away at the end of January. Marriage was impractical as both Lefroy and Austen must have known. Neither had any money, and he was dependent on a great-uncle

An uncle is usually defined as a male relative who is a sibling of a parent or married to a sibling of a parent. Uncles who are related by birth are second-degree relatives. The female counterpart of an uncle is an aunt, and the reciprocal rela ...

in Ireland to finance his education and establish his legal career. If Tom Lefroy later visited Hampshire, he was carefully kept away from the Austens, and Jane Austen never saw him again. In November 1798, Lefroy was still on Austen's mind as she wrote to her sister she had tea with one of his relatives, wanted desperately to ask about him, but could not bring herself to raise the subject.Halperin (1985), 722

Early manuscripts (1796–1798)

After finishing ''Lady Susan'', Austen began her first full-length novel ''Elinor and Marianne''. Her sister remembered that it was read to the family "before 1796" and was told through a series of letters. Without surviving original manuscripts, there is no way to know how much of the original draft survived in the novel published anonymously in 1811 as ''Sense and Sensibility

''Sense and Sensibility'' is a novel by Jane Austen, published in 1811. It was published anonymously; ''By A Lady'' appears on the title page where the author's name might have been. It tells the story of the Dashwood sisters, Elinor (age 19) a ...

''.

Austen began a second novel, ''First Impressions'' (later published as ''Pride and Prejudice

''Pride and Prejudice'' is an 1813 novel of manners by Jane Austen. The novel follows the character development of Elizabeth Bennet, the dynamic protagonist of the book who learns about the repercussions of hasty judgments and comes to appreci ...

''), in 1796. She completed the initial draft in August 1797, aged 21; as with all of her novels, Austen read the work aloud to her family as she was working on it and it became an "established favourite". At this time, her father made the first attempt to publish one of her novels. In November 1797, George Austen wrote to Thomas Cadell

Colonel Thomas Cadell (5 September 1835 – 6 April 1919) was a Scottish recipient of the Victoria Cross, the highest and most prestigious award for gallantry in the face of the enemy that can be awarded to British and Commonwealth forces.

...

, an established publisher in London, to ask if he would consider publishing ''First Impressions''. Cadell returned Mr. Austen's letter, marking it "Declined by Return of Post". Austen may not have known of her father's efforts. Following the completion of ''First Impressions'', Austen returned to ''Elinor and Marianne'' and from November 1797 until mid-1798, revised it heavily; she eliminated the epistolary

Epistolary means "in the form of a letter or letters", and may refer to:

* Epistolary ( la, epistolarium), a Christian liturgical book containing set readings for church services from the New Testament Epistles

* Epistolary novel

* Epistolary poem ...

format in favour of third-person narration and produced something close to ''Sense and Sensibility''. In 1797, Austen met her cousin (and future sister-in-law), Eliza de Feuillide

Eliza Capot, Comtesse de Feuillide (née Hancock; 22 December 1761 – 25 April 1813) was the cousin, and later sister-in-law, of novelist Jane Austen. She is believed to have been the inspiration for a number of Austen's works, such as ''L ...

, a French aristocrat whose first husband the Comte de Feuillide had been guillotined, causing her to flee to Britain, where she married Henry Austen.King, Noel "Jane Austen in France" ''Nineteenth-Century Fiction'', Vol. 8, No. 1, June 1953 p. 2. The description of the execution of the Comte de Feuillide related by his widow left Austen with an intense horror of the French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are considere ...

that lasted for the rest of her life.

During the middle of 1798, after finishing revisions of ''Elinor and Marianne'', Austen began writing a third novel with the working title ''Susan''—later ''Northanger Abbey

''Northanger Abbey'' () is a coming-of-age

Coming of age is a young person's transition from being a child to being an adult. The specific age at which this transition takes place varies between societies, as does the nature of the ...

''—a satire on the popular Gothic novel

Gothic fiction, sometimes called Gothic horror in the 20th century, is a loose literary aesthetic of fear and haunting. The name is a reference to Gothic architecture of the European Middle Ages, which was characteristic of the settings of ea ...

. Austen completed her work about a year later. In early 1803, Henry Austen offered ''Susan'' to Benjamin Crosby, a London publisher, who paid £10 for the copyright. Crosby promised early publication and went so far as to advertise the book publicly as being "in the press", but did nothing more. The manuscript remained in Crosby's hands, unpublished, until Austen repurchased the copyright from him in 1816.

Bath and Southampton

In December 1800, George Austen unexpectedly announced his decision to retire from the ministry, leave Steventon, and move the family to 4,

In December 1800, George Austen unexpectedly announced his decision to retire from the ministry, leave Steventon, and move the family to 4, Sydney Place

Sydney Place in the Bathwick area of Bath, Somerset, England was built around 1800. Many of the properties are listed buildings.

Numbers 1 to 12 were planned by Thomas Baldwin around 1795. The 3-storey buildings have mansard roofs. Jane Aus ...

in Bath

Bath may refer to:

* Bathing, immersion in a fluid

** Bathtub, a large open container for water, in which a person may wash their body

** Public bathing, a public place where people bathe

* Thermae, ancient Roman public bathing facilities

Plac ...

, Somerset. While retirement and travel were good for the elder Austens, Jane Austen was shocked to be told she was moving away from the only home she had ever known. An indication of her state of mind is her lack of productivity as a writer during the time she lived in Bath. She was able to make some revisions to ''Susan'', and she began and then abandoned a new novel, ''The Watsons

''The Watsons'' is an abandoned novel by Jane Austen, probably begun about 1803. There have been a number of arguments advanced as to why she did not complete it, and other authors have since attempted the task. A continuation by Austen's niece ...

'', but there was nothing like the productivity of the years 1795–1799. Tomalin suggests this reflects a deep depression disabling her as a writer, but Honan disagrees, arguing Austen wrote or revised her manuscripts throughout her creative life, except for a few months after her father died. It is often claimed that Austen was unhappy in Bath, which caused her to lose interest in writing, but it is just as possible that Austen's social life in Bath prevented her from spending much time writing novels.Irvine, 2005 4. The critic Robert Irvine argued that if Austen spent more time writing novels when she was in the countryside, it might just have been because she had more spare time as opposed to being more happy in the countryside as is often argued. Furthermore, Austen frequently both moved and travelled over southern England during this period, which was hardly a conducive environment for writing a long novel. Austen sold the rights to publish ''Susan'' to a publisher Crosby & Company, who paid her £10 ().Irvine, 2005 3. The Crosby & Company advertised ''Susan'', but never published it.

The years from 1801 to 1804 are something of a blank space for Austen scholars as Cassandra destroyed all of her letters from her sister in this period for unknown reasons.Halperin (1985), 729 In December 1802, Austen received her only known proposal of marriage. She and her sister visited Alethea and Catherine Bigg, old friends who lived near

The years from 1801 to 1804 are something of a blank space for Austen scholars as Cassandra destroyed all of her letters from her sister in this period for unknown reasons.Halperin (1985), 729 In December 1802, Austen received her only known proposal of marriage. She and her sister visited Alethea and Catherine Bigg, old friends who lived near Basingstoke

Basingstoke ( ) is the largest town in the county of Hampshire. It is situated in south-central England and lies across a valley at the source of the River Loddon, at the far western edge of The North Downs. It is located north-east of Southa ...

. Their younger brother, Harris Bigg-Wither, had recently finished his education at Oxford and was also at home. Bigg-Wither proposed and Austen accepted. As described by Caroline Austen, Jane's niece, and Reginald Bigg-Wither, a descendant, Harris was not attractive—he was a large, plain-looking man who spoke little, stuttered when he did speak, was aggressive in conversation, and almost completely tactless. However, Austen had known him since both were young and the marriage offered many practical advantages to Austen and her family. He was the heir to extensive family estates located in the area where the sisters had grown up. With these resources, Austen could provide her parents a comfortable old age, give Cassandra a permanent home and, perhaps, assist her brothers in their careers. By the next morning, Austen realised she had made a mistake and withdrew her acceptance. No contemporary letters or diaries describe how Austen felt about this proposal. Irvine described Bigg-Wither as somebody who "...seems to have been a man very hard to like, let alone love".

In 1814, Austen wrote a letter to her niece Fanny Knight, who had asked for advice about a serious relationship, telling her that "having written so much on one side of the question, I shall now turn around & entreat you not to commit yourself farther, & not to think of accepting him unless you really do like him. Anything is to be preferred or endured rather than marrying without Affection". The English scholar Douglas Bush wrote that Austen had "had a very high ideal of the love that should unite a husband and wife ... All of her heroines ... know in proportion to their maturity, the meaning of ardent love".Halperin (1985), 732 A possible autobiographical element in ''Sense and Sensibility'' occurs when Elinor Dashwood

Elinor Dashwood is a fictional character and the protagonist of Jane Austen's 1811 novel ''Sense and Sensibility''.

In this novel, Austen analyses the conflict between the opposing temperaments of sense (logic, propriety, and thoughtfulness, as ...

contemplates "the worse and most irremediable of all evils, a connection for life" with an unsuitable man.

In 1804, while living in Bath, Austen started, but did not complete, her novel ''The Watsons''. The story centres on an invalid and impoverished clergyman and his four unmarried daughters. Sutherland describes the novel as "a study in the harsh economic realities of dependent women's lives". Honan suggests, and Tomalin agrees, that Austen chose to stop work on the novel after her father died on 21 January 1805 and her personal circumstances resembled those of her characters too closely for her comfort.

Her father's relatively sudden death left Jane, Cassandra, and their mother in a precarious financial situation. Edward, James, Henry, and Francis Austen (known as Frank) pledged to make annual contributions to support their mother and sisters. For the next four years, the family's living arrangements reflected their financial insecurity. They spent part of the time in rented quarters in Bath before leaving the city in June 1805 for a family visit to Steventon and

In 1804, while living in Bath, Austen started, but did not complete, her novel ''The Watsons''. The story centres on an invalid and impoverished clergyman and his four unmarried daughters. Sutherland describes the novel as "a study in the harsh economic realities of dependent women's lives". Honan suggests, and Tomalin agrees, that Austen chose to stop work on the novel after her father died on 21 January 1805 and her personal circumstances resembled those of her characters too closely for her comfort.

Her father's relatively sudden death left Jane, Cassandra, and their mother in a precarious financial situation. Edward, James, Henry, and Francis Austen (known as Frank) pledged to make annual contributions to support their mother and sisters. For the next four years, the family's living arrangements reflected their financial insecurity. They spent part of the time in rented quarters in Bath before leaving the city in June 1805 for a family visit to Steventon and Godmersham

Godmersham is a village and civil parish in the Ashford District of Kent, England. The village straddles the Great Stour river where it cuts through the North Downs and its land is approximately one third woodland, all in the far east and west o ...

. They moved for the autumn months to the newly fashionable seaside resort of Worthing

Worthing () is a seaside town in West Sussex, England, at the foot of the South Downs, west of Brighton, and east of Chichester. With a population of 111,400 and an area of , the borough is the second largest component of the Brighton and Hov ...

, on the Sussex coast

Sussex (), from the Old English (), is a historic county in South East England that was formerly an independent medieval Anglo-Saxon kingdom. It is bounded to the west by Hampshire, north by Surrey, northeast by Kent, south by the English ...

, where they resided at Stanford Cottage. It was here that Austen is thought to have written her fair copy of ''Lady Susan'' and added its "Conclusion". In 1806, the family moved to Southampton

Southampton () is a port city in the ceremonial county of Hampshire in southern England. It is located approximately south-west of London and west of Portsmouth. The city forms part of the South Hampshire built-up area, which also covers Po ...

, where they shared a house with Frank Austen and his new wife. A large part of this time they spent visiting various branches of the family.

On 5 April 1809, about three months before the family's move to Chawton

Chawton is a village and civil parish in the East Hampshire district of Hampshire, England. The village lies within the South Downs National Park and is famous as the home of Jane Austen for the last eight years of her life.

History

Chawton's re ...

, Austen wrote an angry letter to Richard Crosby, offering him a new manuscript of ''Susan'' if needed to secure the immediate publication of the novel, and requesting the return of the original so she could find another publisher. Crosby replied that he had not agreed to publish the book by any particular time, or at all, and that Austen could repurchase the manuscript for the £10 he had paid her and find another publisher. She did not have the resources to buy the copyright back at that time, but was able to purchase it in 1816.

Chawton

Around early 1809, Austen's brother Edward offered his mother and sisters a more settled life—the use of a large cottage in

Around early 1809, Austen's brother Edward offered his mother and sisters a more settled life—the use of a large cottage in Chawton

Chawton is a village and civil parish in the East Hampshire district of Hampshire, England. The village lies within the South Downs National Park and is famous as the home of Jane Austen for the last eight years of her life.

History

Chawton's re ...

village which was part of the estate around Edward's nearby property Chawton House

Chawton House is a Grade II* listed Elizabethan manor house in Hampshire. It is run as a historic property and also houses the research library of The Centre for the Study of Early Women's Writing, 1600–1830, using the building's connectio ...

. Jane, Cassandra and their mother moved into Chawton cottage on 7 July 1809. Life was quieter in Chawton than it had been since the family's move to Bath in 1800. The Austens did not socialise with gentry

Gentry (from Old French ''genterie'', from ''gentil'', "high-born, noble") are "well-born, genteel and well-bred people" of high social class, especially in the past.

Word similar to gentle imple and decentfamilies

''Gentry'', in its widest ...

and entertained only when family visited. Her niece Anna described the family's life in Chawton as "a very quiet life, according to our ideas, but they were great readers, and besides the housekeeping our aunts occupied themselves in working with the poor and in teaching some girl or boy to read or write."

Published author

Like many women authors at the time, Austen published her books anonymously.Irvine, 2005 15. At the time, the ideal roles for a woman were as wife and mother, and writing for women was regarded at best as a secondary form of activity; a woman who wished to be a full-time writer was felt to be degrading her femininity, so books by women were usually published anonymously in order to maintain the conceit that the female writer was only publishing as a sort of part-time job, and was not seeking to become a "literary lioness" (i.e. a celebrity). During her time at Chawton, Austen published four generally well-received novels. Through her brother Henry, the publisher Thomas Egerton agreed to publish ''Sense and Sensibility

''Sense and Sensibility'' is a novel by Jane Austen, published in 1811. It was published anonymously; ''By A Lady'' appears on the title page where the author's name might have been. It tells the story of the Dashwood sisters, Elinor (age 19) a ...

'', which, like all of Austen's novels except ''Pride and Prejudice'', was published "on commission", that is, at the author's financial risk. When publishing on commission, publishers would advance the costs of publication, repay themselves as books were sold and then charge a 10% commission for each book sold, paying the rest to the author. If a novel did not recover its costs through sales, the author was responsible for them. The alternative to selling via commission was by selling the copyright, where an author received a one-time payment from the publisher for the manuscript, which occurred with ''Pride and Prejudice''.Irvine, 2005 13. Austen's experience with ''Susan'' (the manuscript that became ''Northanger Abbey'') where she sold the copyright to the publisher Crosby & Sons for £10, who did not publish the book, forcing her to buy back the copyright in order to get her work published, left Austen leery of this method of publishing. The final alternative, of selling by subscription, where a group of people would agree to buy a book in advance, was not an option for Austen as only authors who were well known or had an influential aristocratic patron who would recommend an up-coming book to their friends, could sell by subscription. ''Sense and Sensibility'' appeared in October 1811, and was described as being written "By a Lady". As it was sold on commission, Egerton used expensive paper and set the price at 15 shillings ().

Reviews were favourable and the novel became fashionable among young aristocratic opinion-makers;Honan (1987), 289–290. the edition sold out by mid-1813. Austen's novels were published in larger editions than was normal for this period. The small size of the novel-reading public and the large costs associated with hand production (particularly the cost of handmade paper) meant that most novels were published in editions of 500 copies or fewer to reduce the risks to the publisher and the novelist. Even some of the most successful titles during this period were issued in editions of not more than 750 or 800 copies and later reprinted if demand continued. Austen's novels were published in larger editions, ranging from about 750 copies of ''Sense and Sensibility'' to about 2,000 copies of ''Emma''. It is not clear whether the decision to print more copies than usual of Austen's novels was driven by the publishers or the author. Since all but one of Austen's books were originally published "on commission", the risks of overproduction were largely hers (or Cassandra's after her death) and publishers may have been more willing to produce larger editions than was normal practice when their own funds were at risk. Editions of popular works of non-fiction were often much larger.

Austen made £140 () from ''Sense and Sensibility'', which provided her with some financial and psychological independence. After the success of ''Sense and Sensibility'', all of Austen's subsequent books were billed as written "By the author of ''Sense and Sensibility''" and Austen's name never appeared on her books during her lifetime. Egerton then published ''

Reviews were favourable and the novel became fashionable among young aristocratic opinion-makers;Honan (1987), 289–290. the edition sold out by mid-1813. Austen's novels were published in larger editions than was normal for this period. The small size of the novel-reading public and the large costs associated with hand production (particularly the cost of handmade paper) meant that most novels were published in editions of 500 copies or fewer to reduce the risks to the publisher and the novelist. Even some of the most successful titles during this period were issued in editions of not more than 750 or 800 copies and later reprinted if demand continued. Austen's novels were published in larger editions, ranging from about 750 copies of ''Sense and Sensibility'' to about 2,000 copies of ''Emma''. It is not clear whether the decision to print more copies than usual of Austen's novels was driven by the publishers or the author. Since all but one of Austen's books were originally published "on commission", the risks of overproduction were largely hers (or Cassandra's after her death) and publishers may have been more willing to produce larger editions than was normal practice when their own funds were at risk. Editions of popular works of non-fiction were often much larger.

Austen made £140 () from ''Sense and Sensibility'', which provided her with some financial and psychological independence. After the success of ''Sense and Sensibility'', all of Austen's subsequent books were billed as written "By the author of ''Sense and Sensibility''" and Austen's name never appeared on her books during her lifetime. Egerton then published ''Pride and Prejudice

''Pride and Prejudice'' is an 1813 novel of manners by Jane Austen. The novel follows the character development of Elizabeth Bennet, the dynamic protagonist of the book who learns about the repercussions of hasty judgments and comes to appreci ...

'', a revision of ''First Impressions'', in January 1813. Austen sold the copyright to ''Pride and Prejudice'' to Egerton for £110 (). To maximise profits, he used cheap paper and set the price at 18 shillings (). He advertised the book widely and it was an immediate success, garnering three favourable reviews and selling well. Had Austen sold ''Pride and Prejudice'' on commission, she would have made a profit of £475, or twice her father's annual income. By October 1813, Egerton was able to begin selling a second edition. ''Mansfield Park

''Mansfield Park'' is the third published novel by Jane Austen, first published in 1814 by Thomas Egerton. A second edition was published in 1816 by John Murray, still within Austen's lifetime. The novel did not receive any public reviews unt ...

'' was published by Egerton in May 1814. While ''Mansfield Park'' was ignored by reviewers, it was very popular with readers. All copies were sold within six months, and Austen's earnings on this novel were larger than for any of her other novels.

Without Austen's knowledge or approval, her novels were translated into French and published in cheaply produced, pirated editions in France. The literary critic Noel King commented in 1953 that, given the prevailing rage in France at the time for lush romantic fantasies, it was remarkable that her novels with the emphasis on everyday English life had any sort of a market in France. King cautioned that Austen's chief translator in France, Madame Isabelle de Montolieu

Isabelle de Montolieu (1751–1832) was a Swiss novelist and translator. She wrote in and translated to the French language. Montolieu penned a few original novels and over 100 volumes of translations. She wrote the first French translation of ...

, had only the most rudimentary knowledge of English, and her translations were more of "imitations" than translations proper, as Montolieu depended upon assistants to provide a summary, which she then translated into an embellished French that often radically altered Austen's plots and characters. The first of the Austen novels to be published that credited her as the author was in France, when ''Persuasion'' was published in 1821 as ''La Famille Elliot ou L'Ancienne Inclination''.

Austen learned that the Prince Regent

A prince regent or princess regent is a prince or princess who, due to their position in the line of succession, rules a monarchy as regent in the stead of a monarch regnant, e.g., as a result of the sovereign's incapacity (minority or illness ...

admired her novels and kept a set at each of his residences. In November 1815, the Prince Regent's librarian James Stanier Clarke

James Stanier Clarke (1766–1834) was an English cleric, naval author and man of letters. He became librarian in 1799 to George, Prince of Wales (later Prince Regent, then George IV).

Early life

The eldest son of Edward Clarke and Anne Grenfi ...

invited Austen to visit the Prince's London residence and hinted Austen should dedicate the forthcoming ''Emma

Emma may refer to:

* Emma (given name)

Film

* Emma (1932 film), ''Emma'' (1932 film), a comedy-drama film by Clarence Brown

* Emma (1996 theatrical film), ''Emma'' (1996 theatrical film), a film starring Gwyneth Paltrow

* Emma (1996 TV film), '' ...

'' to the Prince. Though Austen disapproved of the Prince Regent, she could scarcely refuse the request. Austen disapproved of the Prince Regent on the account of his womanising, gambling, drinking, spendthrift ways and generally disreputable behaviour.Halperin (1985), 734 She later wrote ''Plan of a Novel, according to Hints from Various Quarters

''Plan of a Novel, according to Hints from Various Quarters'' is a short satirical work by Jane Austen, probably written in May 1816. It was published in complete form for the first time by R. W. Chapman in 1926, extracts having appeared in 1871. ...

'', a satiric outline of the "perfect novel" based on the librarian's many suggestions for a future Austen novel. Austen was greatly annoyed by Clarke's often pompous literary advice, and the ''Plan of a Novel'' parodying Clarke was intended as her revenge for all of the unwanted letters she had received from the royal librarian.

In mid-1815 Austen moved her work from Egerton to John Murray, a better known London publisher, who published ''Emma'' in December 1815 and a second edition of ''Mansfield Park'' in February 1816. ''Emma'' sold well, but the new edition of ''Mansfield Park'' did poorly, and this failure offset most of the income from ''Emma''. These were the last of Austen's novels to be published during her lifetime.

While Murray prepared ''Emma'' for publication, Austen began ''The Elliots'', later published as ''Persuasion

Persuasion or persuasion arts is an umbrella term for Social influence, influence. Persuasion can influence a person's Belief, beliefs, Attitude (psychology), attitudes, Intention, intentions, Motivation, motivations, or Behavior, behaviours.

...

''. She completed her first draft in July 1816. In addition, shortly after the publication of ''Emma'', Henry Austen repurchased the copyright for ''Susan'' from Crosby. Austen was forced to postpone publishing either of these completed novels by family financial troubles. Henry Austen's bank failed in March 1816, depriving him of all of his assets, leaving him deeply in debt and costing Edward, James, and Frank Austen large sums. Henry and Frank could no longer afford the contributions they had made to support their mother and sisters.

Illness and death

Austen was feeling unwell by early 1816, but ignored the warning signs. By the middle of that year, her decline was unmistakable, and she began a slow, irregular deterioration. The majority of biographers rely on

Austen was feeling unwell by early 1816, but ignored the warning signs. By the middle of that year, her decline was unmistakable, and she began a slow, irregular deterioration. The majority of biographers rely on Zachary Cope

Sir Vincent Zachary Cope MD MS FRCS (14 February 1881 – 28 December 1974) was an English physician, surgeon, author, historian and poet perhaps best known for authoring the book ''Cope's Early Diagnosis of the Acute Abdomen'' from 1921 until ...

's 1964 retrospective diagnosis

A retrospective diagnosis (also retrodiagnosis or posthumous diagnosis) is the practice of identifying an illness after the death of the patient (sometimes in a historical figure) using modern knowledge, methods and disease classifications. Altern ...

and list her cause of death as Addison's disease

Addison's disease, also known as primary adrenal insufficiency, is a rare long-term endocrine disorder characterized by inadequate production of the steroid hormones cortisol and aldosterone by the two outer layers of the cells of the adrenal ...

, although her final illness has also been described as resulting from Hodgkin's lymphoma

Hodgkin lymphoma (HL) is a type of lymphoma, in which cancer originates from a specific type of white blood cell called lymphocytes, where multinucleated Reed–Sternberg cells (RS cells) are present in the patient's lymph nodes. The condition wa ...

. When her uncle died and left his entire fortune to his wife, effectively disinheriting his relatives, she suffered a relapse, writing: "I am ashamed to say that the shock of my Uncle's Will brought on a relapse ... but a weak Body must excuse weak Nerves."

Austen continued to work in spite of her illness. Dissatisfied with the ending of ''The Elliots'', she rewrote the final two chapters, which she finished on 6 August 1816. In January 1817, Austen began ''The Brothers'' (titled ''Sanditon

''Sanditon'' (1817) is an unfinished novel by the English writer Jane Austen. In January 1817, Austen began work on a new novel she called ''The Brothers'', later titled ''Sanditon'', and completed eleven chapters before stopping work in mid-M ...

'' when published in 1925), completing twelve chapters before stopping work in mid-March 1817, probably due to illness. Todd describes ''Sanditon''s heroine, Diana Parker, as an "energetic invalid". In the novel Austen mocked hypochondriacs

Hypochondriasis or hypochondria is a condition in which a person is excessively and unduly worried about having a serious illness. An old concept, the meaning of hypochondria has repeatedly changed. It has been claimed that this debilitating cond ...

, and although she describes the heroine as "bilious", five days after abandoning the novel she wrote of herself that she was turning "every wrong colour" and living "chiefly on the sofa".Todd (2015), 13 She put down her pen on 18 March 1817, making a note of it.

Austen made light of her condition, describing it as "bile" and rheumatism

Rheumatism or rheumatic disorders are conditions causing chronic, often intermittent pain affecting the joints or connective tissue. Rheumatism does not designate any specific disorder, but covers at least 200 different conditions, including art ...

. As her illness progressed, she experienced difficulty walking and lacked energy; by mid-April she was confined to bed. In May, Cassandra and Henry brought her to Winchester

Winchester is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city in Hampshire, England. The city lies at the heart of the wider City of Winchester, a local government Districts of England, district, at the western end of the South Downs Nation ...

for treatment, by which time she suffered agonising pain and welcomed death. Austen died in Winchester on 18 July 1817 at the age of 41. Henry, through his clerical connections, arranged for his sister to be buried in the north aisle of the nave

The nave () is the central part of a church, stretching from the (normally western) main entrance or rear wall, to the transepts, or in a church without transepts, to the chancel. When a church contains side aisles, as in a basilica-type ...

of Winchester Cathedral

The Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity,Historic England. "Cathedral Church of the Holy Trinity (1095509)". ''National Heritage List for England''. Retrieved 8 September 2014. Saint Peter, Saint Paul and Saint Swithun, commonly known as Winches ...

. The epitaph composed by her brother James praises Austen's personal qualities, expresses hope for her salvation and mentions the "extraordinary endowments of her mind", but does not explicitly mention her achievements as a writer.

Posthumous publication