James Wolfe (physicist) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

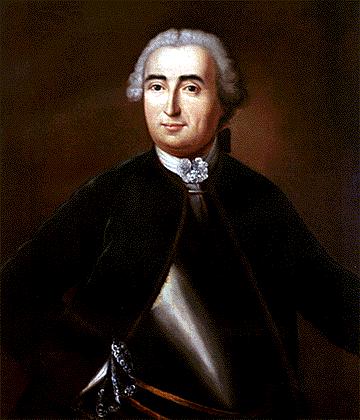

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a

James Wolfe was born at the local vicarage on 2 January 1727 (

James Wolfe was born at the local vicarage on 2 January 1727 (

British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

officer known for his training reforms and, as a major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

in Quebec.

The son of a distinguished general, Edward Wolfe

Lieutenant General Edward Wolfe (1685 – 26 March 1759) was a British army officer who saw action in the War of the Spanish Succession, 1715 Jacobite rebellion and the War of Jenkins' Ear. He is best known as the father of James Wolfe, famous fo ...

, he received his first commission at a young age and saw extensive service in Europe during the War of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's W ...

. His service in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

and in Scotland

Scotland (, ) is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. Covering the northern third of the island of Great Britain, mainland Scotland has a border with England to the southeast and is otherwise surrounded by the Atlantic Ocean to the ...

, where he took part in the suppression of the Jacobite Rebellion

, war =

, image = Prince James Francis Edward Stuart by Louis Gabriel Blanchet.jpg

, image_size = 150px

, caption = James Francis Edward Stuart, Jacobite claimant between 1701 and 1766

, active ...

, brought him to the attention of his superiors. The advancement of his career was halted by the Peace Treaty of 1748 and he spent much of the next eight years on garrison duty in the Scottish Highlands

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sco ...

. Already a brigade major at the age of 18, he was a lieutenant-colonel by 23.

The outbreak of the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

in 1756 offered Wolfe fresh opportunities for advancement. His part in the aborted raid on Rochefort

The Raid on Rochefort (or Descent on Rochefort) was a British amphibious attempt to capture the French Atlantic port of Rochefort in September 1757 during the Seven Years' War. The raid pioneered a new tactic of "descents" on the French coast ...

in 1757 led William Pitt to appoint him second-in-command of an expedition to capture the Fortress of Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg (french: Forteresse de Louisbourg) is a National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Its two sie ...

. Following the success of the siege of Louisbourg he was made commander of a force which sailed up the Saint Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connectin ...

to capture Quebec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the Communauté métrop ...

. After a long siege, Wolfe defeated a French force under the Marquis de Montcalm

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, Marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Veran (28 February 1712 – 14 September 1759) was a French soldier best known as the commander of the forces in North America during the Seven Years' War (whose North American th ...

, allowing British forces to capture the city. Wolfe was killed at the height of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

due to injuries from three musket balls. The next day, Montcalm died as well.

Wolfe's part in the taking of Quebec in 1759 earned him lasting fame, and he became an icon of Britain's victory in the Seven Years' War and subsequent territorial expansion. He was depicted in the painting ''The Death of General Wolfe

''The Death of General Wolfe'' is a 1770 painting by Anglo-American artist Benjamin West, commemorating the 1759 Battle of Quebec, where General James Wolfe died at the moment of victory. The painting, containing vivid suggestions of martyrdom, ...

'', which became famous around the world. Wolfe was posthumously dubbed "The Hero of Quebec", "The Conqueror of Quebec", and also "The Conqueror of Canada", since the capture of Quebec led directly to the capture of Montreal, ending French control of the colony

In modern parlance, a colony is a territory subject to a form of foreign rule. Though dominated by the foreign colonizers, colonies remain separate from the administration of the original country of the colonizers, the ''metropole, metropolit ...

.

Early life

James Wolfe was born at the local vicarage on 2 January 1727 (

James Wolfe was born at the local vicarage on 2 January 1727 (New Style

Old Style (O.S.) and New Style (N.S.) indicate dating systems before and after a calendar change, respectively. Usually, this is the change from the Julian calendar to the Gregorian calendar as enacted in various European countries between 158 ...

or 22 December 1726 Old Style) at Westerham

Westerham is a town and civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent, England. It is located 3.4 miles east of Oxted and 6 miles west of Sevenoaks, adjacent to the Kent border with both Greater London and Surrey.

It is recorded as early as t ...

, Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

, the older of two sons of Colonel (later Lieutenant General) Edward Wolfe

Lieutenant General Edward Wolfe (1685 – 26 March 1759) was a British army officer who saw action in the War of the Spanish Succession, 1715 Jacobite rebellion and the War of Jenkins' Ear. He is best known as the father of James Wolfe, famous fo ...

, a veteran soldier whose family was of Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

origin, and the former Henrietta Thompson. His uncle was Edward Thompson MP, a distinguished politician. Wolfe's childhood home in Westerham, known in his lifetime as Spiers, has been preserved in his memory by the National Trust

The National Trust, formally the National Trust for Places of Historic Interest or Natural Beauty, is a charity and membership organisation for heritage conservation in England, Wales and Northern Ireland. In Scotland, there is a separate and ...

under the name Quebec House

Quebec House is the birthplace of General James Wolfe on what is now known as Quebec Square in Westerham, Kent, England. The house is listed Grade I on the National Heritage List for England since September 1954.

The house dates from the mid 16t ...

. Wolfe's family were long settled in Ireland and he regularly corresponded with his uncle Major Walter Wolfe in Dublin. Stephen Woulfe, the distinguished Irish politician and judge of the next century, was from the Limerick branch of the same family; his father was James Wolfe's third cousin.

The Wolfes were close to the Warde family, who lived at Squerryes Court

Squerryes Court is a late 17th-century manor house that stands just outside the town of Westerham in Kent. The house, which has been held by the same family for over 280 years, is surrounded by extensive gardens and parkland and is a grade I lis ...

in Westerham. Wolfe's boyhood friend George Warde

General George Warde (24 November 1725 – 11 March 1803) was a British Army officer. The second son of Colonel John Warde of Squerryes Court in Westerham, and Miss Frances Bristow of Micheldever. He was a close childhood friend of James Wolfe, ...

achieved fame as Commander-in-Chief in Ireland.

Around 1738, the family moved to Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

, in north-west Kent. From his earliest years, Wolfe was destined for a military career, entering his father's 1st Marine regiment as a volunteer at the age of thirteen.

Illness prevented him from taking part in a large expedition against Spanish-held Cartagena in 1740, and his father sent him home a few months later. He missed what proved to be a disaster for the British forces at the Siege of Cartagena

The Battle of Cartagena de Indias ( es, Sitio de Cartagena de Indias, lit=Siege of Cartagena de Indias) took place during the 1739 to 1748 War of Jenkins' Ear between Spain and Britain. The result of long-standing commercial tensions, the war w ...

during the War of Jenkins' Ear

The War of Jenkins' Ear, or , was a conflict lasting from 1739 to 1748 between Britain and the Spanish Empire. The majority of the fighting took place in New Granada and the Caribbean Sea, with major operations largely ended by 1742. It is con ...

, in which most of the expedition died from disease.

War of the Austrian Succession (1740–1748)

European War

In 1740 theWar of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's W ...

broke out in Europe. Although initially Britain did not actively intervene, the presence of a sizable French army near the border of the Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands nl, Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; french: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; german: Österreichische Niederlande; la, Belgium Austriacum. was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The p ...

compelled the British to send an expedition to help defend the territory of their Austrian ally in 1742. James Wolfe was given his first commission as a second lieutenant in his father's regiment of Marines in 1741.

Early in the following year he transferred to the 12th Regiment of Foot

1 (one, unit, unity) is a number representing a single or the only entity. 1 is also a numerical digit and represents a single unit of counting or measurement. For example, a line segment of ''unit length'' is a line segment of length 1 ...

, a British Army

The British Army is the principal land warfare force of the United Kingdom, a part of the British Armed Forces along with the Royal Navy and the Royal Air Force. , the British Army comprises 79,380 regular full-time personnel, 4,090 Gurk ...

infantry

Infantry is a military specialization which engages in ground combat on foot. Infantry generally consists of light infantry, mountain infantry, motorized infantry & mechanized infantry, airborne infantry, air assault infantry, and marine i ...

regiment, and set sail for Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

some months later where the British took up position in Ghent

Ghent ( nl, Gent ; french: Gand ; traditional English: Gaunt) is a city and a municipality in the Flemish Region of Belgium. It is the capital and largest city of the East Flanders province, and the third largest in the country, exceeded in ...

. Here, Wolfe was promoted to Lieutenant

A lieutenant ( , ; abbreviated Lt., Lt, LT, Lieut and similar) is a commissioned officer rank in the armed forces of many nations.

The meaning of lieutenant differs in different militaries (see comparative military ranks), but it is often sub ...

and made adjutant

Adjutant is a military appointment given to an officer who assists the commanding officer with unit administration, mostly the management of human resources in an army unit. The term is used in French-speaking armed forces as a non-commission ...

of his battalion

A battalion is a military unit, typically consisting of 300 to 1,200 soldiers commanded by a lieutenant colonel, and subdivided into a number of companies (usually each commanded by a major or a captain). In some countries, battalions are ...

. His first year on the continent was a frustrating one as, despite rumours of a British attack on Dunkirk

Dunkirk (french: Dunkerque ; vls, label=French Flemish, Duunkerke; nl, Duinkerke(n) ; , ;) is a commune in the department of Nord in northern France.

In 1743, he was joined by his younger brother, Edward, who had received a commission in the same regiment. That year the Wolfe brothers took part in an offensive launched by the British. Instead of moving southwards as expected, the British and their allies instead thrust eastwards into Southern Germany where they faced a large French army. The army came under the personal command of

In July 1745, Charles Stuart landed in Scotland in an attempt to regain the British throne for his father, the exiled James Stuart. In the initial stages of the

In July 1745, Charles Stuart landed in Scotland in an attempt to regain the British throne for his father, the exiled James Stuart. In the initial stages of the

In 1756, with the outbreak of open hostilities with France, Wolfe was promoted to Colonel. He was stationed in

In 1756, with the outbreak of open hostilities with France, Wolfe was promoted to Colonel. He was stationed in

On 23 January 1758, James Wolfe was appointed as a

On 23 January 1758, James Wolfe was appointed as a

As Wolfe had comported himself admirably at Louisbourg,

As Wolfe had comported himself admirably at Louisbourg,

The British army laid

The British army laid  After an extensive yet inconclusive bombardment of the city, Wolfe initiated a failed attack north of Quebec at Beauport, where the French were securely entrenched. As the weeks wore on the chances of British success lessened, and Wolfe grew despondent. Amherst's large force advancing on Montreal had made very slow progress, ruling out the prospect of Wolfe receiving any help from him.

After an extensive yet inconclusive bombardment of the city, Wolfe initiated a failed attack north of Quebec at Beauport, where the French were securely entrenched. As the weeks wore on the chances of British success lessened, and Wolfe grew despondent. Amherst's large force advancing on Montreal had made very slow progress, ruling out the prospect of Wolfe receiving any help from him.

Wolfe then led 4,400 men in small boats on a very bold and risky amphibious landing at the base of the cliffs west of Quebec along the

Wolfe then led 4,400 men in small boats on a very bold and risky amphibious landing at the base of the cliffs west of Quebec along the  The Battle of the Plains of Abraham caused the deaths of the top military commander on each side: Montcalm died the next day from his wounds. Wolfe's victory at Quebec enabled the

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham caused the deaths of the top military commander on each side: Montcalm died the next day from his wounds. Wolfe's victory at Quebec enabled the

The inscription on the obelisk at Quebec City, erected to commemorate the battle on the Plains of Abraham once read: "Here Died Wolfe Victorious." In order to avoid offending French-Canadians it now simply reads: "Here Died Wolfe."

Wolfe's defeat of the French led to the British capture of the

The inscription on the obelisk at Quebec City, erected to commemorate the battle on the Plains of Abraham once read: "Here Died Wolfe Victorious." In order to avoid offending French-Canadians it now simply reads: "Here Died Wolfe."

Wolfe's defeat of the French led to the British capture of the

Second VolumeThird VolumeFourth VolumeFifth VolumeSixth Volume

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *

", in ''World History Database'' * Wolfe, James: Collection of letters at

A National Treasure in New Brunswick: James Barry's ''Death of General Wolfe''

, in ''New Brunswick Museum'' (Web site), 2003 * NBC

Plains of Abraham Web site

Government of Canada. (National Battlefields Commission) * NBC

1759: From the Warpath to the Plains of Abraham

Virtual Museum Canada, The National Battlefields Commission, 2005 * Archives of James Wolf

(James Wolfe collection, R4770)

are held at

George II George II or 2 may refer to:

People

* George II of Antioch (seventh century AD)

* George II of Armenia (late ninth century)

* George II of Abkhazia (916–960)

* Patriarch George II of Alexandria (1021–1051)

* George II of Georgia (1072–1089)

* ...

but in June he appeared to have made a catastrophic mistake which left the Allies trapped against the river Main

Main may refer to:

Geography

* Main River (disambiguation)

**Most commonly the Main (river) in Germany

* Main, Iran, a village in Fars Province

*"Spanish Main", the Caribbean coasts of mainland Spanish territories in the 16th and 17th centuries

...

and surrounded by enemy forces in "a mousetrap

A mousetrap is a specialized type of animal trap designed primarily to catch and, usually, kill mice. Mousetraps are usually set in an indoor location where there is a suspected infestation of rodents. Larger traps are designed to catch other s ...

".

Rather than contemplate surrender, George tried to rectify the situation by launching an attack on the French positions near the village of Dettingen. Wolfe's regiment was involved in heavy fighting, as the two sides exchanged volley after volley of musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

fire. His regiment had suffered the highest casualties of any of the British infantry battalions, and Wolfe had his horse shot from underneath him. Despite three French attacks the Allies managed to drive off the enemy, who fled through the village of Dettingen which was then occupied by the Allies. However, George failed to adequately pursue the retreating enemy, allowing them to escape. In spite of this the Allies had successfully thwarted the French move into Germany, safeguarding the independence of Hanover

Hanover (; german: Hannover ; nds, Hannober) is the capital and largest city of the German state of Lower Saxony. Its 535,932 (2021) inhabitants make it the 13th-largest city in Germany as well as the fourth-largest city in Northern Germany ...

.

Wolfe's regiment at Battle of Dettingen

The Battle of Dettingen (german: Schlacht bei Dettingen) took place on 27 June 1743 during the War of the Austrian Succession at Dettingen in the Electorate of Mainz, Holy Roman Empire (now Karlstein am Main in Bavaria). It was fought between a ...

came to the attention of the Duke of Cumberland

Duke of Cumberland is a peerage title that was conferred upon junior members of the British Royal Family, named after the historic county of Cumberland.

History

The Earldom of Cumberland, created in 1525, became extinct in 1643. The dukedo ...

who had been close to him during the battle when they came under enemy fire. A year later, he became a captain

Captain is a title, an appellative for the commanding officer of a military unit; the supreme leader of a navy ship, merchant ship, aeroplane, spacecraft, or other vessel; or the commander of a port, fire or police department, election precinct, e ...

of the 45th Regiment of Foot

The 45th (Nottinghamshire) (Sherwood Foresters) Regiment of Foot was a British Army line infantry regiment, raised in 1741. The regiment saw action during Father Le Loutre's War, the French and Indian War and the American Revolutionary War as w ...

. After the success of Dettingen, the 1744 campaign was another frustration as the Allies forces now led by George Wade

Field Marshal George Wade (1673 – 14 March 1748) was a British Army officer who served in the Nine Years' War, War of the Spanish Succession, Jacobite rising of 1715 and War of the Quadruple Alliance before leading the construction of barra ...

failed to complete their objective of capturing Lille

Lille ( , ; nl, Rijsel ; pcd, Lile; vls, Rysel) is a city in the northern part of France, in French Flanders. On the river Deûle, near France's border with Belgium, it is the capital of the Hauts-de-France Regions of France, region, the Pref ...

, fought no major battles, and returned to winter quarters at Ghent without anything to show for their efforts. Wolfe was left devastated when his brother Edward died, probably of consumption

Consumption may refer to:

*Resource consumption

*Tuberculosis, an infectious disease, historically

* Consumption (ecology), receipt of energy by consuming other organisms

* Consumption (economics), the purchasing of newly produced goods for curren ...

, that autumn.

Wolfe's regiment was left behind to garrison Ghent, which meant they missed the Allied defeat at the Battle of Fontenoy

The Battle of Fontenoy was a major engagement of the War of the Austrian Succession, fought on 11 May 1745 near Tournai in modern Belgium. A French army of 50,000 under Marshal Saxe defeated a Pragmatic Army of roughly the same size, led by th ...

in May 1745 during which Wolfe's former regiment suffered extremely heavy casualties. Wolfe's regiment was then summoned to reinforce the main Allied army, now under the command of the Duke of Cumberland

Duke of Cumberland is a peerage title that was conferred upon junior members of the British Royal Family, named after the historic county of Cumberland.

History

The Earldom of Cumberland, created in 1525, became extinct in 1643. The dukedo ...

. Shortly after they had departed Ghent, the town was suddenly attacked by the French who captured it and its garrison. Having narrowly avoided becoming a French prisoner, Wolfe was now made a brigade major

A brigade major was the chief of staff of a brigade in the British Army. They most commonly held the rank of major, although the appointment was also held by captains, and was head of the brigade's "G - Operations and Intelligence" section direct ...

.

Jacobite rising

In July 1745, Charles Stuart landed in Scotland in an attempt to regain the British throne for his father, the exiled James Stuart. In the initial stages of the

In July 1745, Charles Stuart landed in Scotland in an attempt to regain the British throne for his father, the exiled James Stuart. In the initial stages of the 1745 Rising

The Jacobite rising of 1745, also known as the Forty-five Rebellion or simply the '45 ( gd, Bliadhna Theàrlaich, , ), was an attempt by Charles Edward Stuart to regain the British throne for his father, James Francis Edward Stuart. It took pl ...

, the Jacobites captured Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

and defeated government forces at the Battle of Prestonpans

The Battle of Prestonpans, also known as the Battle of Gladsmuir, was fought on 21 September 1745, near Prestonpans, in East Lothian, the first significant engagement of the Jacobite rising of 1745.

Jacobite forces, led by the Stuart exile C ...

in September. This resulted in the recall of Cumberland

Cumberland ( ) is a historic county in the far North West England. It covers part of the Lake District as well as the north Pennines and Solway Firth coast. Cumberland had an administrative function from the 12th century until 1974. From 19 ...

, commander of the British army in Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to culture, ...

and 12,000 troops, including Wolfe's regiment.

On 8 November, the Jacobite army crossed into England, avoiding government forces at Newcastle Newcastle usually refers to:

*Newcastle upon Tyne, a city and metropolitan borough in Tyne and Wear, England

*Newcastle-under-Lyme, a town in Staffordshire, England

*Newcastle, New South Wales, a metropolitan area in Australia, named after Newcastle ...

by taking the western route via Carlisle

Carlisle ( , ; from xcb, Caer Luel) is a city that lies within the Northern England, Northern English county of Cumbria, south of the Anglo-Scottish border, Scottish border at the confluence of the rivers River Eden, Cumbria, Eden, River C ...

. They reached Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

before turning back on 6 December, largely due to lack of English support, and successfully returned to Scotland. Wolfe was aide-de-camp to Henry Hawley

Henry Hawley (12 January 1685 – 24 March 1759) was a British army officer who served in the wars of the first half of the 18th century. He fought in a number of significant battles, including the Capture of Vigo in 1719, Dettingen, Fo ...

, commander at Falkirk

Falkirk ( gd, An Eaglais Bhreac, sco, Fawkirk) is a large town in the Central Lowlands of Scotland, historically within the county of Stirlingshire. It lies in the Forth Valley, northwest of Edinburgh and northeast of Glasgow.

Falkirk had a ...

and fought at Culloden in April under Cumberland.

A famous anecdote claims Wolfe refused an order to shoot a wounded Highland officer after Culloden, the person giving the order variously named as Cumberland or Hawley. There is certainly evidence to confirm Jacobite wounded were killed and Hawley was one of those who gave orders to that effect. However, the claim that he refused such orders cannot be confirmed, while author and historian John Prebble refers to the killings as 'symptomatic of the army's general mood and behaviour.' This included Wolfe; as leader of punitive raids after the battle, he wrote to a colleague that 'as few Highlanders are made prisoner as possible.'

Return to the Continent

In January 1747 Wolfe returned to the Continent and theWar of the Austrian Succession

The War of the Austrian Succession () was a European conflict that took place between 1740 and 1748. Fought primarily in Central Europe, the Austrian Netherlands, Italy, the Atlantic and Mediterranean, related conflicts included King George's W ...

, serving under Sir John Mordaunt. The French had taken advantage of the absence of Cumberland's British troops and had made advances in the Austrian Netherlands

The Austrian Netherlands nl, Oostenrijkse Nederlanden; french: Pays-Bas Autrichiens; german: Österreichische Niederlande; la, Belgium Austriacum. was the territory of the Burgundian Circle of the Holy Roman Empire between 1714 and 1797. The p ...

including the capture of Brussels.

The major French objective in 1747 was to capture Maastricht

Maastricht ( , , ; li, Mestreech ; french: Maestricht ; es, Mastrique ) is a city and a municipality in the southeastern Netherlands. It is the capital and largest city of the province of Limburg. Maastricht is located on both sides of the ...

considered the gateway to the Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands (Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiography ...

. Wolfe was part of Cumberland's army, which marched to protect the city from the advancing French force under Marshal Saxe

Maurice, Count of Saxony (german: Hermann Moritz von Sachsen, french: Maurice de Saxe; 28 October 1696 – 20 November 1750) was a notable soldier, officer and a famed military commander of the 18th century. The illegitimate son of Augustus I ...

. On 2 July Wolfe participated in the Battle of Lauffeld

The Battle of Lauffeld, variously known as Lafelt, Laffeld, Lawfeld, Lawfeldt, Maastricht, or Val, took place on 2 July 1747, between Tongeren in modern Belgium, and the Dutch city of Maastricht. Part of the War of the Austrian Succession, a Fr ...

, he was very badly wounded and received an official commendation for services to Britain. Lauffeld was the largest battle in terms of numbers in which Wolfe fought, with the combined strength of both armies totalling over 140,000. Following their narrow victory at Lauffeld, the French captured Maastricht and seized the strategic fortress at Bergen-op-Zoom

Bergen op Zoom (; called ''Berrege'' in the local dialect) is a municipality and a city located in the south of the Netherlands.

Etymology

The city was built on a place where two types of soil meet: sandy soil and marine clay. The sandy soil p ...

. Both sides remained poised for further offensives, but an armistice

An armistice is a formal agreement of warring parties to stop fighting. It is not necessarily the end of a war, as it may constitute only a cessation of hostilities while an attempt is made to negotiate a lasting peace. It is derived from the La ...

halted the fighting.

In 1748, aged 21 and with service in seven campaigns, Wolfe returned to Britain following the Treaty of Aix-la-Chapelle which ended the war. Under the treaty, Britain and France had agreed to exchange all captured territory and the Austrian Netherlands were returned to Austrian control.

Peacetime service (1748–1756)

Once home, he was posted to Scotland and garrison duty, and a year later was made amajor

Major (commandant in certain jurisdictions) is a military rank of commissioned officer status, with corresponding ranks existing in many military forces throughout the world. When used unhyphenated and in conjunction with no other indicators ...

, in which rank he assumed command of the 20th Regiment, stationed at Stirling

Stirling (; sco, Stirlin; gd, Sruighlea ) is a city in central Scotland, northeast of Glasgow and north-west of Edinburgh. The market town, surrounded by rich farmland, grew up connecting the royal citadel, the medieval old town with its me ...

. In 1750, Wolfe was confirmed as Lieutenant Colonel

Lieutenant colonel ( , ) is a rank of commissioned officers in the armies, most marine forces and some air forces of the world, above a major and below a colonel. Several police forces in the United States use the rank of lieutenant colone ...

of the regiment.

Over the eight years that Wolfe was in Scotland, he wrote military pamphlets and became proficient in French as a result of several trips to Paris. Despite struggling with bouts of ill health suspected to be tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

, he made an effort to keep himself mentally fit by teaching himself Latin and mathematics. When able to, Wolfe trained his body, especially pushing himself to improve his swordsmanship.

In 1752, Wolfe was granted extended leave. Departing from Scotland, he first went to Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

and stayed with his uncle in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

. He visited Belfast

Belfast ( , ; from ga, Béal Feirste , meaning 'mouth of the sand-bank ford') is the capital and largest city of Northern Ireland, standing on the banks of the River Lagan on the east coast. It is the 12th-largest city in the United Kingdo ...

and toured the site of the Battle of the Boyne

The Battle of the Boyne ( ga, Cath na Bóinne ) was a battle in 1690 between the forces of the deposed King James II of England and Ireland, VII of Scotland, and those of King William III who, with his wife Queen Mary II (his cousin and ...

. After a brief stop at his parents' house in Greenwich, he received permission from the Duke of Cumberland to go abroad, and crossed the English Channel to France. In Paris, he was frequently entertained by the British Ambassador, Earl of Albemarle

Earl of Albemarle is a title created several times from Norman times onwards. The word ''Albemarle'' is derived from the Latinised form of the French county of ''Aumale'' in Normandy (Latin: ''Alba Marla'' meaning "White Marl", marl being a ty ...

, with whom he had served in Scotland in 1746. In addition to this, Albemarle arranged an audience for Wolfe with Louis XV

Louis XV (15 February 1710 – 10 May 1774), known as Louis the Beloved (french: le Bien-Aimé), was King of France from 1 September 1715 until his death in 1774. He succeeded his great-grandfather Louis XIV at the age of five. Until he reache ...

. He submitted an application to extend his leave so that he could witness a major military exercise conducted by the French army, but he was instead urgently ordered home. He rejoined his regiment in Glasgow

Glasgow ( ; sco, Glesca or ; gd, Glaschu ) is the most populous city in Scotland and the fourth-most populous city in the United Kingdom, as well as being the 27th largest city by population in Europe. In 2020, it had an estimated popul ...

. By 1754 Britain's declining relationship with France made a war imminent, and fighting broke out in North America between the two sides.

Desertion

Desertion is the abandonment of a military duty or post without permission (a pass, liberty or leave) and is done with the intention of not returning. This contrasts with unauthorized absence (UA) or absence without leave (AWOL ), which ar ...

, especially in the face of the enemy had always officially been regarded as a capital offence. Wolfe laid particular stress on the importance of the death penalty and in 1755, he ordered that any soldier who broke ranks ("offers to quit his rank or offers to flag") should be instantly put to death by an officer or a sergeant.

Seven Years' War (1756–63)

In 1756, with the outbreak of open hostilities with France, Wolfe was promoted to Colonel. He was stationed in

In 1756, with the outbreak of open hostilities with France, Wolfe was promoted to Colonel. He was stationed in Canterbury

Canterbury (, ) is a City status in the United Kingdom, cathedral city and UNESCO World Heritage Site, situated in the heart of the City of Canterbury local government district of Kent, England. It lies on the River Stour, Kent, River Stour.

...

, where his regiment had been posted to guard his home county of Kent

Kent is a county in South East England and one of the home counties. It borders Greater London to the north-west, Surrey to the west and East Sussex to the south-west, and Essex to the north across the estuary of the River Thames; it faces ...

against a French invasion threat. He was extremely dispirited by news of the loss of Minorca in June 1756, lamenting what he saw as the lack of professionalism amongst the British forces. Despite a widespread belief that French landing was imminent, Wolfe thought that it was unlikely his men would be called into action. In spite of this, he trained them diligently and issued fighting instructions to his troops.

As the threat of invasion decreased, the regiment was marched to Wiltshire

Wiltshire (; abbreviated Wilts) is a historic and ceremonial county in South West England with an area of . It is landlocked and borders the counties of Dorset to the southwest, Somerset to the west, Hampshire to the southeast, Gloucestershire ...

. Despite the initial setbacks of the war in Europe and North America, the British were now expected to take the offensive and Wolfe anticipated playing a major role in future operations. However, his health was beginning to decline, which led to suspicions that he was suffering, as his younger brother (Edward Wolfe 1728–1744) had, from consumption

Consumption may refer to:

*Resource consumption

*Tuberculosis, an infectious disease, historically

* Consumption (ecology), receipt of energy by consuming other organisms

* Consumption (economics), the purchasing of newly produced goods for curren ...

. Many of his letters to his parents began to assume a slightly fatalistic

Fatalism is a family of related philosophical doctrines that stress the subjugation of all events or actions to fate or destiny, and is commonly associated with the consequent attitude of resignation in the face of future events which are thou ...

note in which he talked of the likelihood of an early death.

Rochefort

In 1757, Wolfe participated in the Britishamphibious assault

Amphibious warfare is a type of offensive military operation that today uses naval ships to project ground and air power onto a hostile or potentially hostile shore at a designated landing beach. Through history the operations were conducted ...

on Rochefort

Rochefort () may refer to:

Places France

* Rochefort, Charente-Maritime, in the Charente-Maritime department

** Arsenal de Rochefort, a former naval base and dockyard

* Rochefort, Savoie in the Savoie department

* Rochefort-du-Gard, in the Ga ...

, a seaport on the French Atlantic coast. A major naval descent, it was designed to capture the town, and relieve pressure on Britain's German allies who were under French attack in Northern Europe. Wolfe was selected to take part in the expedition partly because of his friendship with its commander, Sir John Mordaunt. In addition to his regimental duties, Wolfe also served as Quartermaster General for the whole expedition. The force was assembled on the Isle of Wight

The Isle of Wight ( ) is a county in the English Channel, off the coast of Hampshire, from which it is separated by the Solent. It is the largest and second-most populous island of England. Referred to as 'The Island' by residents, the Isle of ...

and after weeks of delay finally sailed on 7 September.

The attempt failed as, after capturing an island offshore, the British made no attempt to land on the mainland and press on to Rochefort and instead withdrew home. While their sudden appearance off the French coast had spread panic throughout France, it had little practical effect. Mordaunt was court-martial

A court-martial or court martial (plural ''courts-martial'' or ''courts martial'', as "martial" is a postpositive adjective) is a military court or a trial conducted in such a court. A court-martial is empowered to determine the guilt of memb ...

ed for his failure to attack Rochefort, although acquitted. Nonetheless, Wolfe was one of the few military leaders who had distinguished himself in the raid – having gone ashore to scout the terrain, and having constantly urged Mordaunt into action. He had at one point told the General that he could capture Rochefort if he was given just 500 men but Mordaunt refused him permission. While Wolfe was irritated by the failure, believing that they should have used the advantage of surprise and attacked and taken the town immediately, he was able to draw valuable lessons about amphibious warfare that influenced his later operations at Louisbourg and Quebec.

As a result of his actions at Rochefort, Wolfe was brought to the notice of the Prime Minister, William Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

. Pitt had determined that the best gains in the war were to be made in North America where France was vulnerable, and planned to launch an assault on French Canada

French Canadians (referred to as Canadiens mainly before the twentieth century; french: Canadiens français, ; feminine form: , ), or Franco-Canadians (french: Franco-Canadiens), refers to either an ethnic group who trace their ancestry to Fre ...

. Pitt now decided to promote Wolfe over the heads of a number of senior officers.

Louisbourg

Brigadier General

Brigadier general or Brigade general is a military rank used in many countries. It is the lowest ranking general officer in some countries. The rank is usually above a colonel, and below a major general or divisional general. When appointed ...

, and sent with Major General Jeffrey Amherst in the fleet of Admiral Boscawen

Admiral of the Blue Edward Boscawen, PC (19 August 171110 January 1761) was a British admiral in the Royal Navy and Member of Parliament for the borough of Truro, Cornwall, England. He is known principally for his various naval commands during ...

to lay siege to Fortress of Louisbourg

The Fortress of Louisbourg (french: Forteresse de Louisbourg) is a National Historic Site and the location of a one-quarter partial reconstruction of an 18th-century French fortress at Louisbourg on Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia. Its two sie ...

in New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

(located in present-day Cape Breton Island

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

, Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

). Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour, ...

stood near the mouth of the St Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

, and its capture was considered essential to any attack on Canada from the east. An expedition the previous year had failed to seize the town, because of a French naval build-up. For 1758 Pitt sent a much larger Royal Navy force to accompany Amherst's troops. Wolfe distinguished himself in preparations for the assault, the initial landing and in the aggressive advance of siege batteries. The French capitulated in June of that year in the Siege of Louisbourg (1758)

The siege of Louisbourg was a pivotal operation of the Seven Years' War (known in the United States as the French and Indian War) in 1758 that ended the French colonial era in Atlantic Canada and led to the subsequent British campaign to capt ...

. He then participated in the Expulsion of the Acadians

The Expulsion of the Acadians, also known as the Great Upheaval, the Great Expulsion, the Great Deportation, and the Deportation of the Acadians (french: Le Grand Dérangement or ), was the forced removal, by the British, of the Acadian pe ...

in the Gulf of St. Lawrence Campaign (1758).

The British had initially planned to advance along the St Lawrence and attack Quebec that year, but the onset of winter forced them to postpone to the following year. Similarly a plan to capture New Orleans

New Orleans ( , ,New Orleans

Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

was rejected, and Wolfe returned home to England. Wolfe's part in the taking of the town brought him to the attention of the British public for the first time. The news of the victory at Louisbourg was tempered by the failure of a British force advancing towards Merriam-Webster. ; french: La Nouvelle-Orléans , es, Nuev ...

Montreal

Montreal ( ; officially Montréal, ) is the List of the largest municipalities in Canada by population, second-most populous city in Canada and List of towns in Quebec, most populous city in the Provinces and territories of Canada, Canadian ...

at the Battle of Carillon

The Battle of Carillon, also known as the 1758 Battle of Ticonderoga, Chartrand (2000), p. 57 was fought on July 8, 1758, during the French and Indian War (which was part of the global Seven Years' War). It was fought near Fort Carillon (now k ...

and the death of George Howe, a widely respected young general whom Wolfe described as "the best officer in the British Army". He died at almost the same time as the French general.

Québec (1759)

Appointment

William Pitt the Elder

William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham, (15 November 170811 May 1778) was a British statesman of the Whig group who served as Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1766 to 1768. Historians call him Chatham or William Pitt the Elder to distinguish ...

chose him to lead the British assault on Québec City

Quebec City ( or ; french: Ville de Québec), officially Québec (), is the capital city of the Canadian province of Quebec. As of July 2021, the city had a population of 549,459, and the metropolitan area had a population of 839,311. It is the ...

the following year. Although Wolfe was given the local rank of major general

Major general (abbreviated MG, maj. gen. and similar) is a military rank used in many countries. It is derived from the older rank of sergeant major general. The disappearance of the "sergeant" in the title explains the apparent confusion of a ...

while serving in Canada, in Europe he was still only a full colonel

Colonel (abbreviated as Col., Col or COL) is a senior military officer rank used in many countries. It is also used in some police forces and paramilitary organizations.

In the 17th, 18th and 19th centuries, a colonel was typically in charge of ...

. Amherst had been appointed as Commander-in-Chief in North America, and he would lead a separate and larger force that would attack Canada from the south. He insisted on the choice of his friend, the Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

officer Guy Carleton as Quartermaster General and threatened to resign the command should his friend not have been chosen. Once this was granted, he began making preparations for his departure. Pitt was determined to once again give operations in North America top priority, as he planned to weaken France's international position by sailing back to India.

Advance up the Saint Lawrence

Despite the large build-up of British forces in North America, the strategy of dividing the army for separate attacks on Canada meant that once Wolfe reached Quebec the French commanderLouis-Joseph de Montcalm

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, Marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Veran (28 February 1712 – 14 September 1759) was a French soldier best known as the commander of the forces in North America during the Seven Years' War (whose North American th ...

would have a local superiority of troops having raised large numbers of Canadian militia to defend their homeland. The French had initially expected the British to approach from the east, believing the St Lawrence River was impassable for such a large force and had prepared to defend Quebec from the south and west. An intercepted copy of British plans gave Montcalm several weeks to improve the fortifications protecting Quebec from an amphibious attack by Wolfe.

Montcalm's goal was to prevent the British from capturing Quebec, thereby maintaining a French foothold in Canada. The French government believed a peace treaty was likely to be agreed the following year and so they directed the emphasis of their own efforts towards victory in Germany and a Planned invasion of Britain hoping thereby to secure the exchange of captured territories. For this plan to be successful Montcalm had only to hold out until the start of winter. Wolfe had a narrow window to capture Quebec during 1759 before the St Lawrence began to freeze, trapping his force.

Wolfe's army was assembled at Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour, ...

. He expected to lead 12,000 men, but was greeted by only approximately 400 officers

An officer is a person who has a position of authority in a hierarchical organization. The term derives from Old French ''oficier'' "officer, official" (early 14c., Modern French ''officier''), from Medieval Latin ''officiarius'' "an officer," fro ...

, 7,000 regular troops, and 300 gunners. Wolfe's troops were supported by a fleet of 49 ships and 140 smaller craft led by Admiral Charles Saunders. Eager to begin the campaign, after several delays, he pushed ahead with only part of his force and left orders for further arrivals to be sent on up the St Lawrence after him.

Siege

The British army laid

The British army laid siege

A siege is a military blockade of a city, or fortress, with the intent of conquering by attrition warfare, attrition, or a well-prepared assault. This derives from la, sedere, lit=to sit. Siege warfare is a form of constant, low-intensity con ...

to the city for three months. During that time, Wolfe issued a written document, known as Wolfe's Manifesto, to the French-Canadian civilians, as part of his strategy of psychological intimidation. In March 1759, prior to arriving at Quebec, Wolfe had written to Amherst: "If, by accident in the river, by the enemy's resistance, by sickness, or slaughter in the army, or, from any other cause, we find that Quebec is not likely to fall into our hands (persevering however to the last moment), I propose to set the town on fire with shells, to destroy the harvest, houses and cattle, both above and below, to send off as many Canadians as possible to Europe and to leave famine and desolation behind me; ; but we must teach these scoundrels to make war in a more gentleman like manner." This manifesto has widely been regarded as counter-productive as it drove many neutrally-inclined inhabitants to actively resist the British, swelling the size of the militia defending to Quebec to as many as 10,000.

Battle and subsequent death

Wolfe then led 4,400 men in small boats on a very bold and risky amphibious landing at the base of the cliffs west of Quebec along the

Wolfe then led 4,400 men in small boats on a very bold and risky amphibious landing at the base of the cliffs west of Quebec along the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

. His army, with two small cannons, scaled the 200-metre cliff from the river below early in the morning of 13 September 1759. They surprised the French under the command of the Marquis de Montcalm

Louis-Joseph de Montcalm-Grozon, Marquis de Montcalm de Saint-Veran (28 February 1712 – 14 September 1759) was a French soldier best known as the commander of the forces in North America during the Seven Years' War (whose North American th ...

, who thought the cliff would be unclimbable, and had set his defences accordingly. Faced with the possibility that the British would haul more cannons up the cliffs and knock down the city's remaining walls, the French fought the British on the Plains of Abraham

The Plains of Abraham (french: Plaines d'Abraham) is a historic area within the Battlefields Park in Quebec City, Quebec, anada. It was established on 17 March 1908. The land is the site of the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, which took place ...

. They were defeated after fifteen minutes of battle, but when Wolfe began to move forward, he was shot thrice, once in the arm, once in the shoulder, and finally in the chest.

Historian Francis Parkman

Francis Parkman Jr. (September 16, 1823 – November 8, 1893) was an American historian, best known as author of '' The Oregon Trail: Sketches of Prairie and Rocky-Mountain Life'' and his monumental seven-volume '' France and England in North Am ...

describes the death of Wolfe:

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham caused the deaths of the top military commander on each side: Montcalm died the next day from his wounds. Wolfe's victory at Quebec enabled the

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham caused the deaths of the top military commander on each side: Montcalm died the next day from his wounds. Wolfe's victory at Quebec enabled the Montreal Campaign

The Montreal Campaign, also known as the Fall of Montreal, was a British three-pronged offensive against Montreal which took place from July 2 to 8 September 1760 during the French and Indian War as part of the global Seven Years' War. The campai ...

against the French the following year. With the fall of that city, French rule in North America, outside of Louisiana

Louisiana , group=pronunciation (French: ''La Louisiane'') is a state in the Deep South and South Central regions of the United States. It is the 20th-smallest by area and the 25th most populous of the 50 U.S. states. Louisiana is borde ...

and the tiny islands of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon

Saint Pierre and Miquelon (), officially the Territorial Collectivity of Saint-Pierre and Miquelon (french: link=no, Collectivité territoriale de Saint-Pierre et Miquelon ), is a self-governing territorial overseas collectivity of France in t ...

, came to an end.

Wolfe's body was returned to Britain on HMS ''Royal William'' and interred in the family vault in St Alfege Church, Greenwich

St Alfege Church is an Anglican church in the centre of Greenwich, part of the Royal Borough of Greenwich in London. It is of medieval origin and was rebuilt in 1712–1714 to the designs of Nicholas Hawksmoor.

Early history

The church is ded ...

alongside his father (who had died in March 1759). The funeral service took place on 20 November 1759, the same day that Admiral Hawke won the last of the three great victories of the "Wonderful Year

''Wonderful Year'' is a children's novel by Nancy Barnes (Helen Simmons Adams) with illustrations by Kate Seredy. ''Wonderful Year'' was published in 1946 by publisher Julian Messner. It describes a year in the life of the Martin family, includi ...

" and the "Year of Victories

In Great Britain, this year was known as the ''Annus Mirabilis'', because of British victories in the Seven Years' War.

Events

January–March

* January 6 – George Washington marries Martha Dandridge Custis.

* January 11 &ndas ...

" – Minden

Minden () is a middle-sized town in the very north-east of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, the greatest town between Bielefeld and Hanover. It is the capital of the district (''Kreis'') of Minden-Lübbecke, which is part of the region of Detm ...

, Quebec

Quebec ( ; )According to the Canadian government, ''Québec'' (with the acute accent) is the official name in Canadian French and ''Quebec'' (without the accent) is the province's official name in Canadian English is one of the thirtee ...

and Quiberon Bay

Quiberon Bay (french: Baie de Quiberon) is an area of sheltered water on the south coast of Brittany. The bay is in the Morbihan département.

Geography

The bay is roughly triangular in shape, open to the south with the Gulf of Morbihan to t ...

.

Character

Wolfe was renowned by his troops for being demanding on himself and on them. He was also known for carrying the same combat equipment as his infantrymen – amusket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

, cartridge box

The cartridge box was a box to carry cartridges. It was worn on the soldier

A soldier is a person who is a member of an army. A soldier can be a conscripted or volunteer enlisted person, a non-commissioned officer, or an officer.

Etymolo ...

and bayonet

A bayonet (from French ) is a knife, dagger, sword, or spike-shaped weapon designed to fit on the end of the muzzle of a rifle, musket or similar firearm, allowing it to be used as a spear-like weapon.Brayley, Martin, ''Bayonets: An Illustr ...

– which was unusual for officers of the period. Although he was prone to illness, Wolfe was an active and restless figure. Amherst reported that Wolfe seemed to be everywhere at once. There was a story that when someone in the British Court branded the young Brigadier mad, King George II retorted, "Mad, is he? Then I hope he will bite some of my other generals." A cultured man, before the Battle of the Plains of Abraham

The Battle of the Plains of Abraham, also known as the Battle of Quebec (french: Bataille des Plaines d'Abraham, Première bataille de Québec), was a pivotal battle in the Seven Years' War (referred to as the French and Indian War to describe ...

Wolfe is said by John Robison to have recited Gray's ''Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

''Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard'' is a poem by Thomas Gray, completed in 1750 and first published in 1751. The poem's origins are unknown, but it was partly inspired by Gray's thoughts following the death of the poet Richard West in 1742 ...

'', containing the line "The paths of glory lead but to the grave" to his officers, adding: "Gentlemen, I would rather have written that poem than take Quebec tomorrow".

After being stung by rejection, in a letter to his mother in 1751 he admitted he would probably never marry and stated that he believed people could easily live without marrying. An apocryphal story was published after Wolfe's death saying that he had carried a locket portrait of Katherine Lowther, his supposed betrothed, with him to North America, and that he gave the locket to First Lieutenant John Jervis the night before he died. The story holds that Wolfe had a premonition of his own death in battle, and that Jervis faithfully returned the locket to Lowther.

Legacy

New France

New France (french: Nouvelle-France) was the area colonized by France in North America, beginning with the exploration of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence by Jacques Cartier in 1534 and ending with the cession of New France to Great Britain and Spai ...

department of Canada

Canada is a country in North America. Its ten provinces and three territories extend from the Atlantic Ocean to the Pacific Ocean and northward into the Arctic Ocean, covering over , making it the world's second-largest country by tot ...

, and his "hero's death" made him a legend in his homeland. The Wolfe legend led to the famous painting ''The Death of General Wolfe

''The Death of General Wolfe'' is a 1770 painting by Anglo-American artist Benjamin West, commemorating the 1759 Battle of Quebec, where General James Wolfe died at the moment of victory. The painting, containing vivid suggestions of martyrdom, ...

'' by Benjamin West

Benjamin West, (October 10, 1738 – March 11, 1820) was a British-American artist who painted famous historical scenes such as '' The Death of Nelson'', ''The Death of General Wolfe'', the '' Treaty of Paris'', and '' Benjamin Franklin Drawin ...

, the Anglo-American folk ballad "Brave Wolfe" (sometimes known as "Bold Wolfe"), and the opening line of the patriotic Canadian anthem, "The Maple Leaf Forever

"The Maple Leaf Forever" is a Canadian song written by Alexander Muir (1830–1906) in 1867, the year of Canada's Canadian Confederation, Confederation. He wrote the work after serving with the Queen's Own Rifles of Toronto in the Battle of Ridg ...

".

In 1792, scant months after the partition of Quebec into the provinces of Upper Canada

The Province of Upper Canada (french: link=no, province du Haut-Canada) was a part of British Canada established in 1791 by the Kingdom of Great Britain, to govern the central third of the lands in British North America, formerly part of the ...

and Lower Canada

The Province of Lower Canada (french: province du Bas-Canada) was a British colony on the lower Saint Lawrence River and the shores of the Gulf of Saint Lawrence (1791–1841). It covered the southern portion of the current Province of Quebec an ...

, the Lieutenant-Governor

A lieutenant governor, lieutenant-governor, or vice governor is a high officer of state, whose precise role and rank vary by jurisdiction. Often a lieutenant governor is the deputy, or lieutenant, to or ranked under a governor — a "second-in-comm ...

of the former, John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the Drainage basin, watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. ...

, named the archipelago at the entrance to the St. Lawrence River

The St. Lawrence River (french: Fleuve Saint-Laurent, ) is a large river in the middle latitudes of North America. Its headwaters begin flowing from Lake Ontario in a (roughly) northeasterly direction, into the Gulf of St. Lawrence, connecting ...

for the victorious Generals: Wolfe Island, Amherst Island

Amherst Island is located in Lake Ontario, west of Kingston, Ontario, Canada. Amherst Island, being wholly in Lake Ontario, is upstream, above the St Lawrence River Thousand Islands. The Island is part of Loyalist Township in Lennox and Addingt ...

, Howe Island

Howe Island is an island located in Lake Ontario east of Kingston in Frontenac County, Ontario, Canada. It is part of the Thousand Islands chain. Together with Wolfe Island and Simcoe Island, Howe Island is part of the township of Fronten ...

, Carleton Island

Carleton Island is located in the St Lawrence River in upstate New York. It is part of the Town of Cape Vincent, in Jefferson County.

History

Originally held by the Iroquois, one of the first Europeans to take notice of the island was Pierre ...

and Gage Island, for Thomas Gage

General Thomas Gage (10 March 1718/192 April 1787) was a British Army general officer and colonial official best known for his many years of service in North America, including his role as British commander-in-chief in the early days of the ...

. The last is now known as Simcoe Island

Simcoe Island is a small island approximately long, and across at its widest point, in Lake Ontario, just off Wolfe Island, close to Kingston, Ontario, and Amherst Island.

The island is almost completely farmland and can be reached by ferry ...

.

In 1832, the first war monument in present-day Canada was erected on the site where Wolfe purportedly fell. The site is marked by a column surmounted by a helmet and sword. An inscription at its base reads, in French and English, "Here died Wolfe – 13 September 1759." It replaces a large stone which had been placed there by British troops to mark the spot.

Wolfe's Landing National Historic Site of Canada is located in Kennington Cove, on the east coast of Cape Breton Island, Nova Scotia

Cape Breton Island (french: link=no, île du Cap-Breton, formerly '; gd, Ceap Breatainn or '; mic, Unamaꞌki) is an island on the Atlantic coast of North America and part of the province of Nova Scotia, Canada.

The island accounts for 18. ...

. Contained entirely within the Fortress of Louisbourg National Historic Site of Canada

National Historic Sites of Canada (french: Lieux historiques nationaux du Canada) are places that have been designated by the federal Minister of the Environment

An environment minister (sometimes minister of the environment or secretary of t ...

, the site is bounded by a rocky beach to the south, and a rolling landscape of grasses and forest to the north, east and west. It was from this site that, during the Seven Years' War

The Seven Years' War (1756–1763) was a global conflict that involved most of the European Great Powers, and was fought primarily in Europe, the Americas, and Asia-Pacific. Other concurrent conflicts include the French and Indian War (1754� ...

, British forces launched their successful attack on the French forces at Louisbourg

Louisbourg is an unincorporated community and former town in Cape Breton Regional Municipality, Nova Scotia.

History

The French military founded the Fortress of Louisbourg in 1713 and its fortified seaport on the southwest part of the harbour, ...

. Wolfe's Landing was designated a national historic site of Canada in 1929 because: "here, on 8 June 1758, the men of Brigadier General James Wolfe's brigade made their successful landing, leading to the capitulation of Louisbourg".

There is a memorial to Wolfe in Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

by Joseph Wilton

Joseph Wilton (16 July 1722 – 25 November 1803) was an English sculptor. He was one of the founding members of the Royal Academy in 1768, and the academy's third keeper.

His works are particularly numerous memorialising the famous Britons ...

. The 3rd Duke of Richmond, who had served in Wolfe's regiment in 1753, commissioned a bust of Wolfe from Wilton. There is an oil painting "Placing the Canadian Colours on Wolfe's Monument in Westminster Abbey" by Emily Warren

Emily Warren Schwartz (born August 25, 1992) is an American singer and songwriter signed to the label Prescription Songs. She is best known for the songs she has written for several high-profile pop artists, including Backstreet Boys, The Chai ...

in Currie Hall

Currie Hall is a hall within the Currie Building, which is an annex to the Mackenzie Building at the Royal Military College of Canada in Kingston, Ontario. It was built in 1922, and is a Recognized Federal Heritage Building.

The hall was design ...

at the Royal Military College of Canada

'')

, established = 1876

, type = Military academy

, chancellor = Anita Anand ('' la, ex officio, label=none'' as Defence Minister)

, principal = Harry Kowal

, head_label ...

.

A statue of Wolfe overlooks the Royal Naval College in Greenwich

Greenwich ( , ,) is a town in south-east London, England, within the ceremonial county of Greater London. It is situated east-southeast of Charing Cross.

Greenwich is notable for its maritime history and for giving its name to the Greenwich ...

, a spot which has become increasingly popular for its panoramic views of London. A statue also graces the green in his native Westerham

Westerham is a town and civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent, England. It is located 3.4 miles east of Oxted and 6 miles west of Sevenoaks, adjacent to the Kent border with both Greater London and Surrey.

It is recorded as early as t ...

, Kent, alongside one of that village's other famous resident, Sir Winston Churchill

Sir Winston Leonard Spencer Churchill (30 November 187424 January 1965) was a British statesman, soldier, and writer who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom twice, from 1940 to 1945 Winston Churchill in the Second World War, dur ...

. At Stowe Gardens

Stowe or Stowe Gardens, formerly Stowe Landscape Gardens, are extensive, Grade I listed gardens and parkland in Buckinghamshire, England. Largely created in the eighteenth century the gardens at Stowe are arguably the most significant example ...

in Buckinghamshire there is an obelisk, known as Wolfe's obelisk, built by the family that owned Stowe as Wolfe spent his last night in England at the mansion. Wolfe is buried under the Church of St Alfege, Greenwich

St Alfege Church is an Anglican church in the centre of Greenwich, part of the Royal Borough of Greenwich in London. It is of medieval origin and was rebuilt in 1712–1714 to the designs of Nicholas Hawksmoor.

Early history

The church is ded ...

, where there are four memorials to him: a replica of his coffin plate in the floor; ''The Death of Wolfe'', a painting completed in 1762 by Edward Peary; a wall tablet; and a stained glass window. In addition the local primary school is named after him. The house in Greenwich where he lived, Macartney House, has an English Heritage blue plaque

A blue plaque is a permanent sign installed in a public place in the United Kingdom and elsewhere to commemorate a link between that location and a famous person, event, or former building on the site, serving as a historical marker. The term i ...

with his name on, and a nearby road is named General Wolfe Road after him.

In 1761, as a perpetual memorial to Wolfe, George Warde

General George Warde (24 November 1725 – 11 March 1803) was a British Army officer. The second son of Colonel John Warde of Squerryes Court in Westerham, and Miss Frances Bristow of Micheldever. He was a close childhood friend of James Wolfe, ...

, a friend of Wolfe's from boyhood, instituted the Wolfe Society

James Wolfe (2 January 1727 – 13 September 1759) was a British Army officer known for his training reforms and, as a Major-general (United Kingdom), major general, remembered chiefly for his victory in 1759 over the Kingdom of France, French ...

, which to this day meets annually in Westerham

Westerham is a town and civil parish in the Sevenoaks District of Kent, England. It is located 3.4 miles east of Oxted and 6 miles west of Sevenoaks, adjacent to the Kent border with both Greater London and Surrey.

It is recorded as early as t ...

for the Wolfe Dinner to his "Pious and Immortal Memory". Warde paid Benjamin West to paint "The Boyhood of Wolfe" which used to hang at Squerres Court but has recently been donated to the National Trust and is now hung at Quebec House his childhood home in Westerham. Warde also erected a cenotaph in Squerres Park to mark the place where Wolfe had received his first commission while visiting the Wardes.

In 1979, Crayola

Crayola LLC, formerly the Binney & Smith Company, is an American manufacturing company specializing in art supplies. It is known for its brand ''Crayola'' and best known for its crayons. The company is headquartered in Forks Township, Pennsylvan ...

crayons introduced a Wolfe Brown colour crayon. It was discontinued the following year.

There are several institutions, localities, thoroughfares, and landforms named in honour of him in Canada. Significant monuments to Wolfe in Canada exist on the Plains of Abraham where he fell, and near Parliament Hill

Parliament Hill (french: Colline du Parlement, colloquially known as The Hill, is an area of Crown land on the southern banks of the Ottawa River in downtown Ottawa, Ontario, Canada. Its Gothic revival suite of buildings, and their architectu ...

in Ottawa

Ottawa (, ; Canadian French: ) is the capital city of Canada. It is located at the confluence of the Ottawa River and the Rideau River in the southern portion of the province of Ontario. Ottawa borders Gatineau, Quebec, and forms the core ...

. Ontario Governor John Graves Simcoe

John Graves Simcoe (25 February 1752 – 26 October 1806) was a British Army general and the first lieutenant governor of Upper Canada from 1791 until 1796 in southern Ontario and the Drainage basin, watersheds of Georgian Bay and Lake Superior. ...

named Wolfe Island, an island in Lake Ontario

Lake Ontario is one of the five Great Lakes of North America. It is bounded on the north, west, and southwest by the Canadian province of Ontario, and on the south and east by the U.S. state of New York. The Canada–United States border sp ...

and the Saint Lawrence River off the coast of Kingston (near the Royal Military College of Canada

'')

, established = 1876

, type = Military academy

, chancellor = Anita Anand ('' la, ex officio, label=none'' as Defence Minister)

, principal = Harry Kowal

, head_label ...

) in Wolfe's honour in 1792. On 13 September 2009, the Wolfe Island Historical Society led celebrations on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of James Wolfe's victory at Quebec. A life-size statue in Wolfe's likeness is to be sculpted.

South Mount Royal Park, Calgary is home to a James Wolfe statue since 2009, but it was originally located in Exchange Court in New York City. It was sculpted in 1898 by John Massey Rhind

John Massey Rhind (9 July 1860 – 1 January 1936) was a Scottish-American sculptor. Among Rhind's better known works is the marble statue of Dr. Crawford W. Long located in the National Statuary Hall Collection in Washington D.C. (1926).

E ...

and moved into storage around 1945 to 1950, sold in 1967 and relocated to Centennial Planetarium

The Centennial Planetarium was a planetarium located at 701 11 Street SW in Calgary, Alberta. Designed by Calgary architectural firm McMillan Long and Associates and opened in 1967 for the Canadian Centennial, it is one of Calgary's best examples ...

in Calgary, stored 2000 to 2008 and finally installed again in 2009.

A senior girls house at the Duke of York's Royal Military School

The Duke of York's Royal Military School, more commonly called the Duke of York's, is a co-educational academy (for students aged 11 to 18) with military traditions in Guston, Kent. Since becoming an academy in 2010, the school is now sponsor ...

is named after Wolfe, where all houses are named after prominent figures of the military. There is a James Wolfe school for children aged 5–11 down the hill from his house in Greenwich, in Chesterfield Walk, which is just east of General Wolfe Road.

His letters home from the age of 13 until his death as well as his copy of Gray's ''Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard

''Elegy Written in a Country Churchyard'' is a poem by Thomas Gray, completed in 1750 and first published in 1751. The poem's origins are unknown, but it was partly inspired by Gray's thoughts following the death of the poet Richard West in 1742 ...