James Martineau on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Martineau (; 21 April 1805 – 11 January 1900) was a British

Martineau's ministerial career was suddenly cut short in 1832 by difficulties growing out of the " regium donum", which had on the death of the senior minister fallen to him. He conceived it as "a religious monopoly" to which "the nation at large contributes," while "Presbyterians alone receive," and which placed him in "a relation to the state" so "seriously objectionable" as to be "impossible to hold." The invidious distinction it drew between

Martineau's ministerial career was suddenly cut short in 1832 by difficulties growing out of the " regium donum", which had on the death of the senior minister fallen to him. He conceived it as "a religious monopoly" to which "the nation at large contributes," while "Presbyterians alone receive," and which placed him in "a relation to the state" so "seriously objectionable" as to be "impossible to hold." The invidious distinction it drew between

In 1839 Martineau came to the defence of Unitarian doctrine, under attack by Liverpool clergymen including Fielding Ould and

In 1839 Martineau came to the defence of Unitarian doctrine, under attack by Liverpool clergymen including Fielding Ould and

''Endeavours after the Christian Life''

(1843);

''Miscellanies''

1852;

''The Rationale of Religious Enquiry: or, The question stated of reason, the Bible, and the church; in six lectures''

(1853);

''Studies of Christianity : a series of papers''

(1858);

''A Study of Spinoza''

(1882) * ''Types of Ethical Theory'' (1885)

''Religious Thought in England in the 19th Century''

(1896) pages 246–250; * A. W. Jackson

''James Martineau, a Biography and a Study''

(Boston, 1900); * J. Drummond and C. B. Upton, ''Life and Letters'' (2 volumes, 1901); *

''Recollections of James Martineau''

(1903); * J. E. Carpenter

''James Martineau, Theologian and Teacher''

(1905); * C. B. Upton

''Dr. Martineau's philosophy, a survey''

(1905); * * Frank Schulman, ''James Martineau: This Conscience-Intoxicated Unitarian'' (2002). Attribution *

religious philosopher

Religious philosophy is philosophical thinking that is influenced and directed as a consequence to teachings from a particular religion. It can be done objectively, but may also be done as a persuasion tool by believers in that faith. Religious ...

influential in the history of Unitarianism

Unitarianism, as a Christian denominational family of churches, was first defined in Poland-Lithuania and Transylvania in the late 16th century. It was then further developed in England and America until the early 19th century, although theolog ...

.

For 45 years he was Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy and Political Economy in Manchester New College (now Harris Manchester College, of the University of Oxford), the principal training college for British Unitarianism

The General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches (GAUFCC or colloquially British Unitarians) is the umbrella organisation for Unitarian, Free Christians, and other liberal religious congregations in the United Kingdom and Irelan ...

.

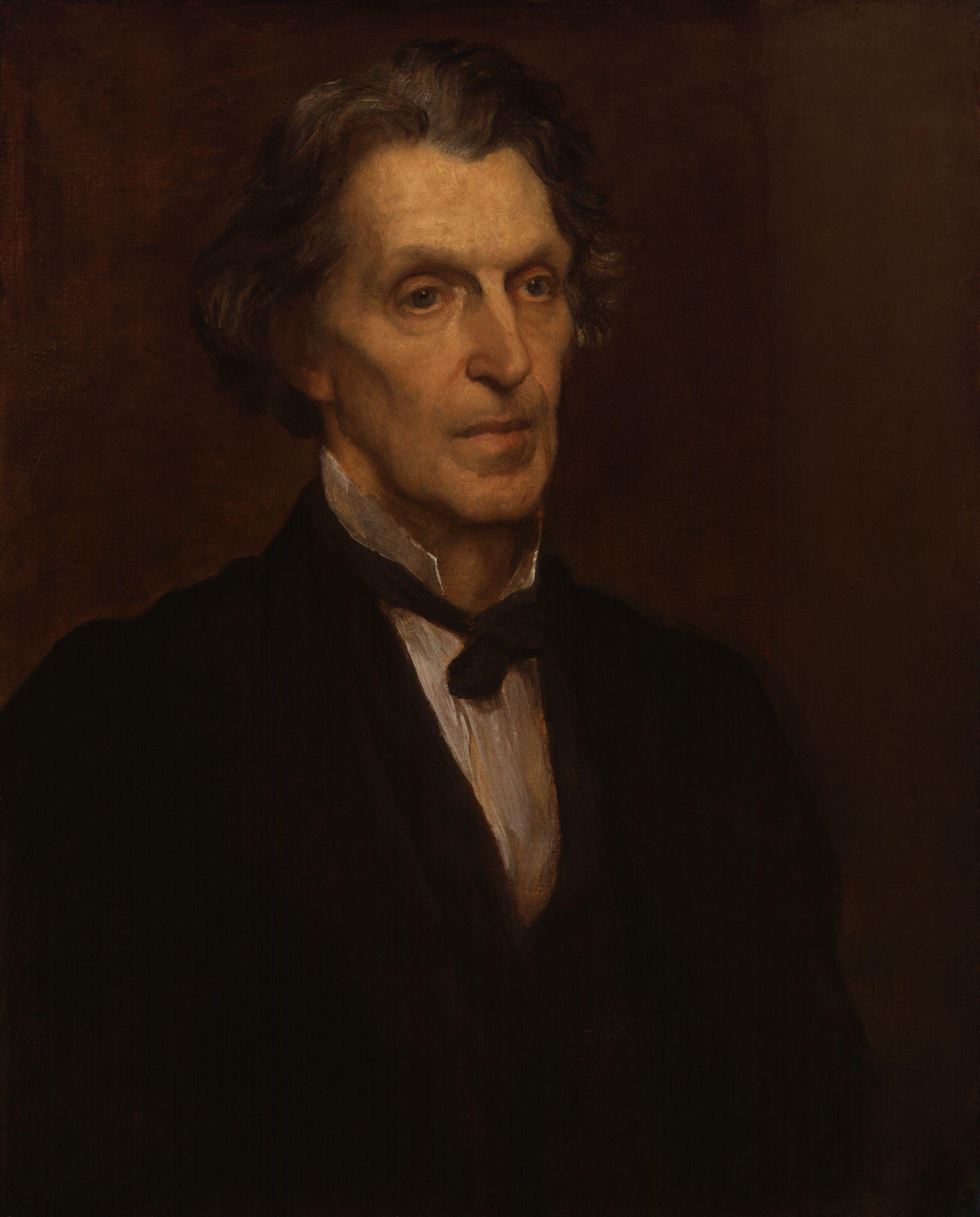

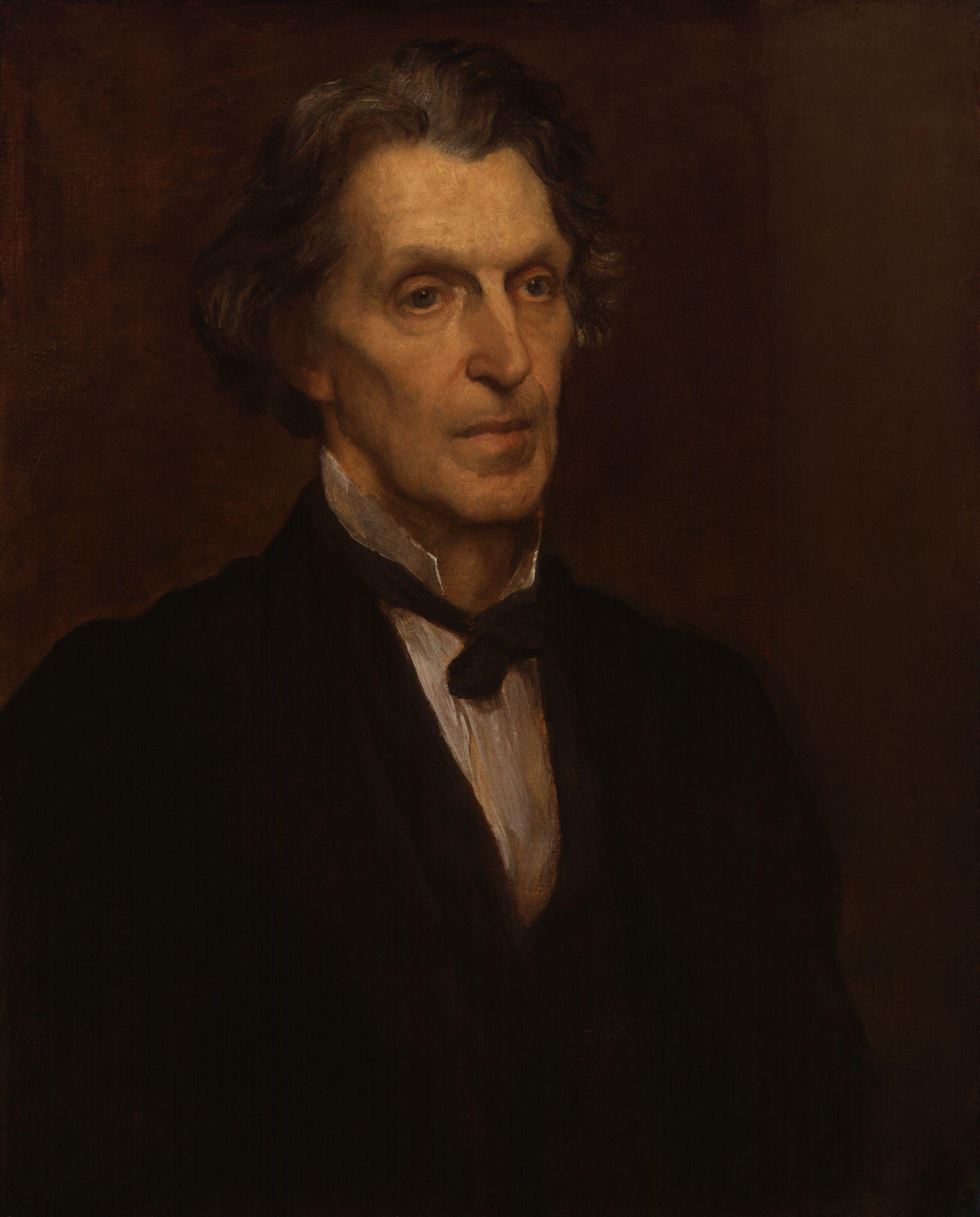

Many portraits of Martineau, including one painted by George Frederick Watts

George Frederic Watts (23 February 1817, in London – 1 July 1904) was a British painter and sculptor associated with the Symbolist movement. He said "I paint ideas, not things." Watts became famous in his lifetime for his allegorical wor ...

, are held at London's National Portrait Gallery. In 2014, the gallery revealed that its patron, Catherine, Princess of Wales

Catherine, Princess of Wales, (born Catherine Elizabeth Middleton; 9 January 1982) is a member of the British royal family. She is married to William, Prince of Wales, heir apparent to the British throne, making Catherine the likely next ...

, was related to Martineau. The Princess's great-great-grandfather, Francis Martineau Lupton, was Martineau's grandnephew. The gallery also holds written correspondence between Martineau and Poet Laureate

A poet laureate (plural: poets laureate) is a poet officially appointed by a government or conferring institution, typically expected to compose poems for special events and occasions. Albertino Mussato of Padua and Francesco Petrarca (Petrarch) ...

, Alfred, Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Gold Medal at Cambridge for one of his ...

- who records that he "regarded Martineau as the mastermind of all the remarkable company with whom he engaged". Martineau and Lord Tennyson

Alfred Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (6 August 1809 – 6 October 1892) was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate of the United Kingdom, Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria's reign. In 1829, Tennyson was awarded the Chancellor's Go ...

were familiar with Queen Victoria's son, Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany

Prince Leopold, Duke of Albany, (Leopold George Duncan Albert; 7 April 185328 March 1884) was the eighth child and youngest son of Queen Victoria and Prince Albert. Leopold was later created Duke of Albany, Earl of Clarence, and Baron Arklow. ...

; they noted that Leopold, who had often "conversed with the eminent Dr. Martineau, was considered to be a young man of a very thoughtful mind, high aims, and quite remarkable acquirements". William Ewart Gladstone

William Ewart Gladstone ( ; 29 December 1809 – 19 May 1898) was a British statesman and Liberal politician. In a career lasting over 60 years, he served for 12 years as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom, spread over four non-conse ...

said to Frances Power Cobbe

Frances Power Cobbe (4 December 1822 – 5 April 1904) was an Anglo-Irish writer, philosopher, religious thinker, social reformer, anti-vivisection activist and leading women's suffrage campaigner. She founded a number of animal advocacy group ...

"Dr Martineau is beyond question the greatest of living thinkers".

One of Martineau's children was the Pre-Raphaelite

The Pre-Raphaelite Brotherhood (later known as the Pre-Raphaelites) was a group of English painters, poets, and art critics, founded in 1848 by William Holman Hunt, John Everett Millais, Dante Gabriel Rossetti, William Michael Rossetti, James ...

watercolourist Edith Martineau.

Early life

The seventh of eight children, James Martineau was born inNorwich

Norwich () is a cathedral city and district of Norfolk, England, of which it is the county town. Norwich is by the River Wensum, about north-east of London, north of Ipswich and east of Peterborough. As the seat of the See of Norwich, with ...

, England, where his father Thomas (1764–1826) was a cloth manufacturer and merchant. His mother, Elizabeth Rankin, was the eldest daughter of a sugar refiner and grocer. The Martineau family

The Martineau family is an intellectual, business and political family, political dynasty associated first with Norwich and later also London and Birmingham, England. The family were prominent Unitarianism, Unitarians; a room in London's Essex ...

were descended from Gaston Martineau, a Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

surgeon and refugee, who married Marie Pierre in 1693, and settled in Norwich. His son and grandson, respectively the great-grandfather and grandfather of James Martineau, were surgeons in the same city. Many of the family were active in Unitarian causes, so much so that a room in Essex Hall

Essex Street Chapel, also known as Essex Church, is a Unitarian place of worship in London. It was the first church in England set up with this doctrine, and was established when Dissenters still faced legal threat. As the birthplace of British ...

, the headquarters of British Unitarianism

The General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches (GAUFCC or colloquially British Unitarians) is the umbrella organisation for Unitarian, Free Christians, and other liberal religious congregations in the United Kingdom and Irelan ...

, was eventually named after them. Branches of the Martineau family in Norwich, Birmingham and London were socially and politically prominent Unitarians; other elite Unitarian families in Birmingham were the Kenricks, Nettlefolds and the Chamberlains, with much intermarriage between these families taking place. Essex Hall held a statue of Martineau. His niece, Frances Lupton

Frances Elizabeth Lupton (née Greenhow; 20 July 1821 – 9 March 1892) was an Englishwoman of the Victorian era who worked to open up educational opportunities for women. She married into the politically active Lupton family of Leeds, where sh ...

, who was close to his sister Harriet, had worked to open up educational opportunities for women.

Education and early years

James was educated atNorwich Grammar School

Norwich School (formally King Edward VI Grammar School, Norwich) is a selective English independent day school in the close of Norwich Cathedral, Norwich. Among the oldest schools in the United Kingdom, it has a traceable history to 1096 as a ...

where he was a school-fellow with George Borrow

George Henry Borrow (5 July 1803 – 26 July 1881) was an English writer of novels and of travel based on personal experiences in Europe. His travels gave him a close affinity with the Romani people of Europe, who figure strongly in his work. Hi ...

under Edward Valpy

Edward Valpy (1764–1832) was an English cleric, classical scholar and schoolteacher.

Life

Valpy, the fourth son of Richard Valpy of St. John's, Jersey, by his wife Catherine, daughter of John Chevalier, was born at Reading. He was educated at Tr ...

, as good a scholar as his better-known brother Richard

Richard is a male given name. It originates, via Old French, from Frankish language, Old Frankish and is a Compound (linguistics), compound of the words descending from Proto-Germanic language, Proto-Germanic ''*rīk-'' 'ruler, leader, king' an ...

, but proved too sensitive for school. He was sent to Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

to the private academy of Dr. Lant Carpenter

Lant Carpenter, Dr. (2 September 1780 – 5 or 6 April 1840) was an English educator and Christian Unitarianism, Unitarian Minister (Christianity), minister.

Early life

Lant Carpenter was born in Kidderminster, the third son of George Carpenter ...

, under whom he studied for two years. On leaving he was apprenticed to a civil engineer

A civil engineer is a person who practices civil engineering – the application of planning, designing, constructing, maintaining, and operating infrastructure while protecting the public and environmental health, as well as improving existing ...

at Derby

Derby ( ) is a city and unitary authority area in Derbyshire, England. It lies on the banks of the River Derwent in the south of Derbyshire, which is in the East Midlands Region. It was traditionally the county town of Derbyshire. Derby gai ...

, where he acquired "a store of exclusively scientific conceptions," but also began to look to religion for mental stimulation.

Martineau's conversion

Conversion or convert may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media

* "Conversion" (''Doctor Who'' audio), an episode of the audio drama ''Cyberman''

* "Conversion" (''Stargate Atlantis''), an episode of the television series

* "The Conversion" ...

followed, and in 1822 he entered the dissenting academy

The dissenting academies were schools, colleges and seminaries (often institutions with aspects of all three) run by English Dissenters, that is, those who did not conform to the Church of England. They formed a significant part of England's edu ...

Manchester College, then at York

York is a cathedral city with Roman origins, sited at the confluence of the rivers Ouse and Foss in North Yorkshire, England. It is the historic county town of Yorkshire. The city has many historic buildings and other structures, such as a ...

- his uncle Peter Finch Martineau

Peter Finch Martineau (12 June 1755 – 2 December 1847) was an English businessman and a philanthropist, with particular interest in improving the lives of disadvantaged people through education.

Life and family

A Unitarian, he was born into t ...

was one of its Vice-Presidents. Here he "woke up to the interest of moral and metaphysical speculations." Of his teachers, one, the Rev. Charles Wellbeloved

Charles Wellbeloved (6 April 1769 – 29 August 1858) was an English Unitarian divine and archaeologist.

Biography

Charles Wellbeloved, only child of John Wellbeloved (1742–1787), by his wife Elizabeth Plaw, was born in Denmark Street, St ...

, was, Martineau said, "a master of the true Lardner type, candid and catholic, simple and thorough, humanly fond indeed of the counsels of peace, but piously serving every bidding of sacred truth." The other, the Rev. John Kenrick, he described as a man so learned as to be placed by Dean Stanley

Arthur Penrhyn Stanley, (13 December 1815 – 18 July 1881), known as Dean Stanley, was an English Anglican priest and ecclesiastical historian. He was Dean of Westminster from 1864 to 1881. His position was that of a Broad Churchman and he w ...

"in the same line with Blomfield and Thirlwall Thirlwall is a surname. Notable people with the surname include:

*Anthony Thirlwall (born 1941), Professor of Applied Economics at the University of Kent

**Thirlwall's Law, a law of economics

*Connop Thirlwall (1797–1875), English clergyman and ...

," and as "so far above the level of either vanity or dogmatism, that cynicism itself could not think of them in his presence." On leaving the college in 1827 Martineau returned to Bristol

Bristol () is a city, ceremonial county and unitary authority in England. Situated on the River Avon, it is bordered by the ceremonial counties of Gloucestershire to the north and Somerset to the south. Bristol is the most populous city in ...

to teach in the school of Lant Carpenter; but in the following year, he was ordained for a Unitarian church in Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

, whose senior minister was a relative of his.

Martineau's ministerial career was suddenly cut short in 1832 by difficulties growing out of the " regium donum", which had on the death of the senior minister fallen to him. He conceived it as "a religious monopoly" to which "the nation at large contributes," while "Presbyterians alone receive," and which placed him in "a relation to the state" so "seriously objectionable" as to be "impossible to hold." The invidious distinction it drew between

Martineau's ministerial career was suddenly cut short in 1832 by difficulties growing out of the " regium donum", which had on the death of the senior minister fallen to him. He conceived it as "a religious monopoly" to which "the nation at large contributes," while "Presbyterians alone receive," and which placed him in "a relation to the state" so "seriously objectionable" as to be "impossible to hold." The invidious distinction it drew between Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

s on the one hand, and Catholics, members of the Religious Society of Friends

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abili ...

(Quakers), other nonconformists, unbelievers, and Jews on the other, who were compelled to support a ministry they conscientiously disapproved, offended his conscience. His conscience did, however, allow him to attend both the Coronation of Queen Victoria

The coronation of Queen Victoria of the United Kingdom took place on Thursday, 28 June 1838, just over a year after she succeeded to the throne of the United Kingdom at the age of 18. The ceremony was held in Westminster Abbey after a public p ...

in 1838 and her Golden Jubilee half a century later. A year prior to the coronation, at St James's Palace

St James's Palace is the most senior royal palace in London, the capital of the United Kingdom. The palace gives its name to the Court of St James's, which is the monarch's royal court, and is located in the City of Westminster in London. Altho ...

, Martineau had " kissed the hand" of the queen at the deputation of British Presbyterian ministers.

Work and writings

From Dublin, he was called toLiverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

. He lodged in a house owned by Joseph Williamson. It was during his 25 years in Liverpool that he published his first work, ''Rationale of Religious Enquiry'', which caught the attention of many religious and philosophical figures.

In 1840 Martineau was appointed Professor of Mental and Moral Philosophy and Political Economy in Manchester New College, the seminary in which he had been educated, and which had now moved from York back to Manchester

Manchester () is a city in Greater Manchester, England. It had a population of 552,000 in 2021. It is bordered by the Cheshire Plain to the south, the Pennines to the north and east, and the neighbouring city of Salford to the west. The t ...

. This position, and the principalship (1869–1885), he held for 45 years. In 1853 the college moved to London, and four years later he followed it there. In 1858 he combined this work with preaching at the pulpit of Little Portland Street Chapel in London, which for the first two years he shared with John James Tayler (who was also his colleague in the college), and then for twelve years as its only minister.

In 1866, the Chair of the Philosophy of Mind and Logic at University College, London

, mottoeng = Let all come who by merit deserve the most reward

, established =

, type = Public research university

, endowment = £143 million (2020)

, budget = � ...

, fell vacant when the liberal nonconformist Dr John Hoppus retired. Martineau became a candidate, and despite strong support from some quarters, potent opposition was organised by the anti-clerical George Grote

George Grote (; 17 November 1794 – 18 June 1871) was an English political radical and classical historian. He is now best known for his major work, the voluminous ''History of Greece''.

Early life

George Grote was born at Clay Hill near B ...

, whose refusal to endorse Martineau resulted in the appointment of George Croom Robertson

George Croom Robertson (10 March 1842 – 20 September 1892) was a Scottish philosopher. He sat on the Committee of the National Society for Women's Suffrage and his wife, Caroline Anna Croom Robertson was a college administrator.

Biography

...

, then an untried man. Martineau, however, sidestepped Grote's opposition, much as Hoppus had learnt to do during his Professorship, and developed a cordial friendship with Robertson.

Martineau was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

The American Academy of Arts and Sciences (abbreviation: AAA&S) is one of the oldest learned societies in the United States. It was founded in 1780 during the American Revolution by John Adams, John Hancock, James Bowdoin, Andrew Oliver, and ...

in 1872. He was awarded LL.D. of Harvard in 1872, S.T.D. of Leiden

Leiden (; in English and archaic Dutch also Leyden) is a city and municipality in the province of South Holland, Netherlands. The municipality of Leiden has a population of 119,713, but the city forms one densely connected agglomeration wit ...

in 1874, D.D. of Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

in 1884, D.C.L. of Oxford

Oxford () is a city in England. It is the county town and only city of Oxfordshire. In 2020, its population was estimated at 151,584. It is north-west of London, south-east of Birmingham and north-east of Bristol. The city is home to the ...

in 1888 and D. Litt. of Dublin

Dublin (; , or ) is the capital and largest city of Republic of Ireland, Ireland. On a bay at the mouth of the River Liffey, it is in the Provinces of Ireland, province of Leinster, bordered on the south by the Dublin Mountains, a part of th ...

in 1891.

Life and thought

Martineau described some of the changes he underwent; how he had "carried into logical and ethical problems the maxims and postulates of physical knowledge," and had moved within narrow lines "interpreting human phenomena by the analogy of external nature"; and how in a period of "second education" atHumboldt University

Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (german: Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin, abbreviated HU Berlin) is a German public research university in the central borough of Mitte in Berlin. It was established by Frederick William III on the initiative of ...

in Berlin, with Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg

Friedrich Adolf Trendelenburg (30 November 1802 – 24 January 1872) was a German philosopher and philologist.

Life

He was born at Eutin, near Lübeck. He was placed in a gymnasium in Eutin, which was under the direction of , a philologist infl ...

, he experienced "a new intellectual birth". It made him, however, no more of a theist

Theism is broadly defined as the belief in the existence of a supreme being or deities. In common parlance, or when contrasted with ''deism'', the term often describes the classical conception of God that is found in monotheism (also referred to ...

than he had been before, and he developed Transcendentalist views, which became a significant current within Unitarianism.

Early years

In his early life he was a preacher. Although he did not believe in the Incarnation, he held deity to be manifest in humanity; man underwent anapotheosis

Apotheosis (, ), also called divinization or deification (), is the glorification of a subject to divine levels and, commonly, the treatment of a human being, any other living thing, or an abstract idea in the likeness of a deity. The term has ...

, and all life was touched with the dignity and the grace which it owed to its source. His preaching led to works that built up his reputation:''Endeavours after the Christian Life'', 1st series, 1843; 2nd series, 1847; ''Hours of Thought'', 1st series, 1876; 2nd series, 1879; the various hymn-books he issued at Dublin in 1831, at Liverpool in 1840, in London in 1873; and the ''Home Prayers'' in 1891.

In 1839 Martineau came to the defence of Unitarian doctrine, under attack by Liverpool clergymen including Fielding Ould and

In 1839 Martineau came to the defence of Unitarian doctrine, under attack by Liverpool clergymen including Fielding Ould and Hugh Boyd M‘Neile

Hugh Boyd M‘Neile (18 July 1795 – 28 January 1879) was a well-connected and controversial Irish-born Calvinist Anglican of Scottish descent.

Fiercely anti- Tractarian and anti-Roman Catholic (and, even more so, anti-Anglo-Catholic) and an ...

. In the controversy, Martineau published five discourses, in which he discussed "the Bible as the great autobiography of human nature from its infancy to its perfection," "the Deity of Christ," "Vicarious Redemption," "Evil," and "Christianity without Priest and without Ritual."

In Martineau's earliest book, ''The Rationale of Religious Enquiry'', published in 1836, he placed the authority of reason above that of Scripture; and he assessed the New Testament as "uninspired, but truthful; sincere, able, vigorous, but fallible." The book marked him down, among older British Unitarians, as a dangerous radical, and his ideas were the catalyst for a pamphlet war in America between George Ripley George Ripley may refer to:

*George Ripley (alchemist) (died 1490), English author and alchemist

*George Ripley (transcendentalist)

George Ripley (October 3, 1802 – July 4, 1880) was an American social reformer, Unitarian minister, and journa ...

(who favored Martineau's questioning of the historical accuracy of scripture) and the more conservative Andrews Norton

Andrews Norton (December 31, 1786 – September 18, 1853) was an American preacher and theologian. Along with William Ellery Channing, he was the leader of mainstream Unitarianism of the early and middle 19th century, and was known as the "Unitari ...

. Despite his belief that the Bible was fallible, Martineau continued to hold the view that "in no intelligible sense can any one who denies the supernatural origin of the religion of Christ be termed a Christian," which term, he explained, was used not as "a name of praise," but simply as " a designation of belief." He censured the German rationalists "for having preferred, by convulsive efforts of interpretation, to compress the memoirs of Christ and His apostles into the dimensions of ordinary life, rather than admit the operation of miracle on the one hand, or proclaim their abandonment of Christianity on the other".

Transcendentalism

Martineau came to know German philosophy and criticism, especially the criticism ofFerdinand Christian Baur

Ferdinand Christian Baur (21 June 1792 – 2 December 1860) was a German Protestant theologian and founder and leader of the (new) Tübingen School of theology (named for the University of Tübingen where Baur studied and taught). Following Hegel ...

and the Tübingen

Tübingen (, , Swabian: ''Dibenga'') is a traditional university city in central Baden-Württemberg, Germany. It is situated south of the state capital, Stuttgart, and developed on both sides of the Neckar and Ammer rivers. about one in thr ...

school, which affected his construction of Christian history. French influences were Ernest Renan

Joseph Ernest Renan (; 27 February 18232 October 1892) was a French Orientalist and Semitic scholar, expert of Semitic languages and civilizations, historian of religion, philologist, philosopher, biblical scholar, and critic. He wrote influe ...

and the Strassburg theologians. The rise of evolution compelled him to reformulate his theism. He addressed the public, as editor and contributor, in the ''Monthly Repository

The ''Monthly Repository'' was a British monthly Unitarian periodical which ran between 1806 and 1838. In terms of editorial policy on theology, the ''Repository'' was largely concerned with rational dissent. Considered as a political journal, it ...

'', the '' Christian Reformer'', the ''Prospective Review

Prospective refers to an event that is likely or expected to happen in the future. For example, a ''prospective student'' is someone who is considering attending a school. A prospective cohort study is a type of study, e.g., in sociology or medici ...

'', the ''Westminster Review

The ''Westminster Review'' was a quarterly British publication. Established in 1823 as the official organ of the Philosophical Radicals, it was published from 1824 to 1914. James Mill was one of the driving forces behind the liberal journal until ...

'' and the ''National Review

''National Review'' is an American conservative editorial magazine, focusing on news and commentary pieces on political, social, and cultural affairs. The magazine was founded by the author William F. Buckley Jr. in 1955. Its editor-in-chief i ...

''. Later he was a frequent contributor to the literary monthlies. More systematic expositions came in ''Types of Ethical Theory'' and ''The Study of Religion'', and, partly, in ''The Seat of Authority in Religion'' (1885, 1888 and 1890). What did Jesus signify? This was the problem which Martineau attempted to deal with in ''The Seat of Authority in Religion''.

Martineau's theory of religious society, or church, was that of an idealist. He propounded a scheme, which was not taken up, that would have removed the church from the hands of a clerical order, and allowed the coordination of sects or churches under the state. Eclectic by nature, he gathered ideas from any source that appealed. Stopford Brooke Stopford Brooke may refer to;

* Stopford Brooke (chaplain) (1832–1916), Irish writer, critic, clergyman, and royal chaplain

* Stopford Brooke (politician) (1859–1938), British Member of Parliament, 1906–1910

{{hndis, Brooke, Stopford ...

once asked A. P. Stanley, Dean of Westminster

The Dean of Westminster is the head of the chapter at Westminster Abbey. Due to the Abbey's status as a Royal Peculiar, the dean answers directly to the British monarch (not to the Bishop of London as ordinary, nor to the Archbishop of Canterbu ...

, "if the Church of England would broaden sufficiently to allow James Martineau to be made Archbishop of Canterbury

The archbishop of Canterbury is the senior bishop and a principal leader of the Church of England, the ceremonial head of the worldwide Anglican Communion and the diocesan bishop of the Diocese of Canterbury. The current archbishop is Justi ...

".

Later years

Although he had opposed the removal (1889) of Manchester New College to Oxford, Martineau took part in the opening of the new buildings, conducting the communion service (19 October 1893) in the chapel of what is todayHarris Manchester College

Harris Manchester College is one of the Colleges of the University of Oxford, constituent colleges of the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom. It was founded in Warrington in 1757 as a college for Unitarianism, Unitarian students and move ...

, University of Oxford.

A wide circle of friends mourned his death on 11 January 1900; Oscar Wilde

Oscar Fingal O'Flahertie Wills Wilde (16 October 185430 November 1900) was an Irish poet and playwright. After writing in different forms throughout the 1880s, he became one of the most popular playwrights in London in the early 1890s. He is ...

references him in his prose.

He was buried in a family grave on the eastern side of Highgate Cemetery

Highgate Cemetery is a place of burial in north London, England. There are approximately 170,000 people buried in around 53,000 graves across the West and East Cemeteries. Highgate Cemetery is notable both for some of the people buried there as ...

.

One of his daughters was the watercolourist

Watercolor (American English) or watercolour (British English; see spelling differences), also ''aquarelle'' (; from Italian diminutive of Latin ''aqua'' "water"), is a painting method”Watercolor may be as old as art itself, going back to t ...

Edith Martineau who was interred in the family grave in 1909.

Bibliography

''Endeavours after the Christian Life''

(1843);

''Miscellanies''

1852;

''The Rationale of Religious Enquiry: or, The question stated of reason, the Bible, and the church; in six lectures''

(1853);

''Studies of Christianity : a series of papers''

(1858);

''A Study of Spinoza''

(1882) * ''Types of Ethical Theory'' (1885)

See also

* Free Christians (Britain) *General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches

The General Assembly of Unitarian and Free Christian Churches (GAUFCC or colloquially British Unitarians) is the umbrella organisation for Unitarian, Free Christians, and other liberal religious congregations in the United Kingdom and Irelan ...

*Unitarianism

Unitarianism (from Latin ''unitas'' "unity, oneness", from ''unus'' "one") is a nontrinitarian branch of Christian theology. Most other branches of Christianity and the major Churches accept the doctrine of the Trinity which states that there i ...

References

Sources

* J. Hunt''Religious Thought in England in the 19th Century''

(1896) pages 246–250; * A. W. Jackson

''James Martineau, a Biography and a Study''

(Boston, 1900); * J. Drummond and C. B. Upton, ''Life and Letters'' (2 volumes, 1901); *

Henry Sidgwick

Henry Sidgwick (; 31 May 1838 – 28 August 1900) was an English utilitarian philosopher and economist. He was the Knightbridge Professor of Moral Philosophy at the University of Cambridge from 1883 until his death, and is best known in philos ...

, ''Lectures on the Ethics of Green, Spencer and Martineau'' (1902);

* A. H. Craufurd''Recollections of James Martineau''

(1903); * J. E. Carpenter

''James Martineau, Theologian and Teacher''

(1905); * C. B. Upton

''Dr. Martineau's philosophy, a survey''

(1905); * * Frank Schulman, ''James Martineau: This Conscience-Intoxicated Unitarian'' (2002). Attribution *

External links

* * * {{DEFAULTSORT:Martineau, James 1805 births 1900 deaths Burials at Highgate Cemetery Alumni of Harris Manchester College, Oxford English philosophers English Unitarians English people of French descent Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences People educated at Norwich School Irish non-subscribing Presbyterian ministers Martineau family