James Clerk Maxwell on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

James Clerk Maxwell (13 June 1831 – 5 November 1879) was a Scottish mathematician and scientist responsible for the classical theory of

James Clerk Maxwell was born on 13 June 1831 at 14 India Street,

James Clerk Maxwell was born on 13 June 1831 at 14 India Street,

Maxwell was sent to the prestigious

Maxwell was sent to the prestigious

Maxwell left the Academy in 1847 at age 16 and began attending classes at the

Maxwell left the Academy in 1847 at age 16 and began attending classes at the

In October 1850, already an accomplished mathematician, Maxwell left Scotland for the

In October 1850, already an accomplished mathematician, Maxwell left Scotland for the

The 25-year-old Maxwell was a good 15 years younger than any other professor at Marischal. He engaged himself with his new responsibilities as head of a department, devising the syllabus and preparing lectures. He committed himself to lecturing 15 hours a week, including a weekly '' pro bono'' lecture to the local working men's college. He lived in Aberdeen with his cousin William Dyce Cay, a Scottish civil engineer, during the six months of the academic year and spent the summers at Glenlair, which he had inherited from his father.

The 25-year-old Maxwell was a good 15 years younger than any other professor at Marischal. He engaged himself with his new responsibilities as head of a department, devising the syllabus and preparing lectures. He committed himself to lecturing 15 hours a week, including a weekly '' pro bono'' lecture to the local working men's college. He lived in Aberdeen with his cousin William Dyce Cay, a Scottish civil engineer, during the six months of the academic year and spent the summers at Glenlair, which he had inherited from his father.

He focused his attention on a problem that had eluded scientists for 200 years: the nature of

He focused his attention on a problem that had eluded scientists for 200 years: the nature of

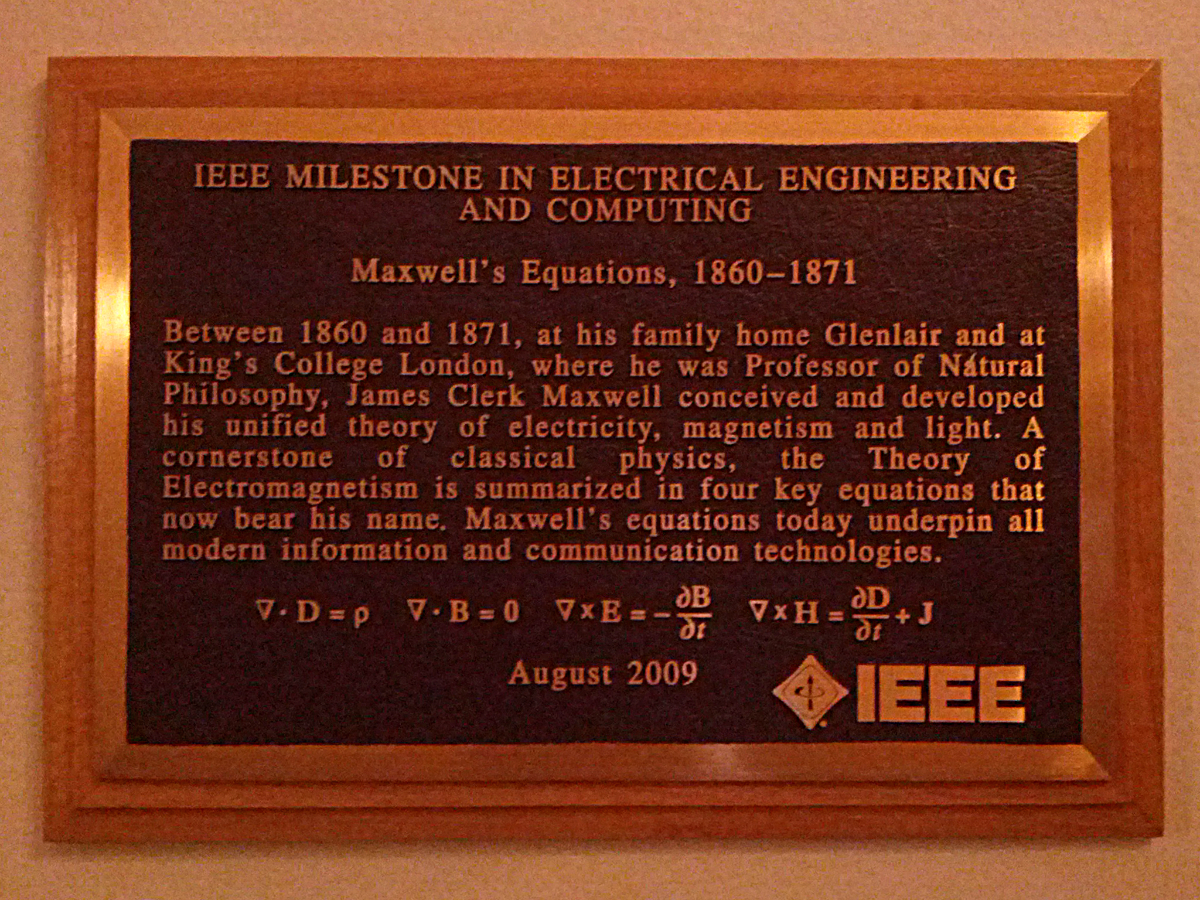

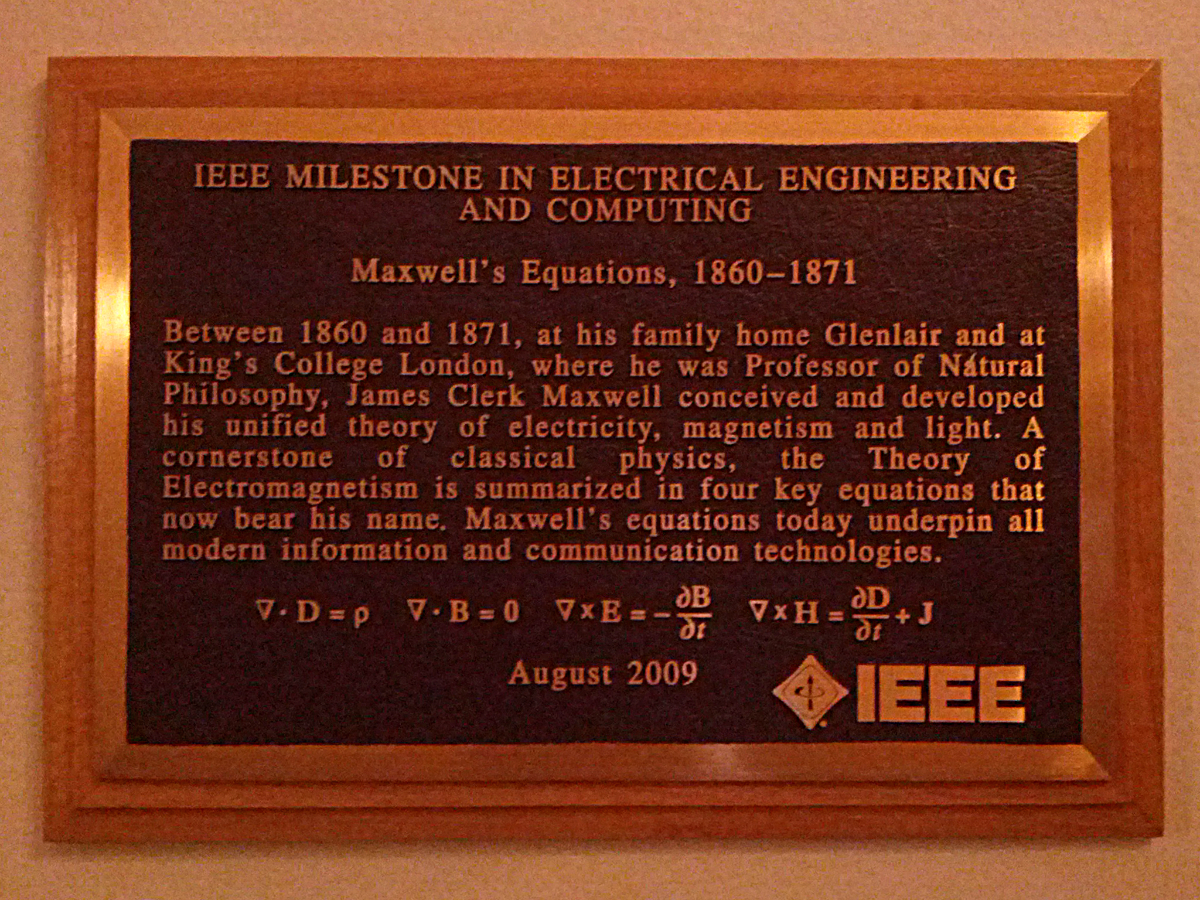

Maxwell's time at King's was probably the most productive of his career. He was awarded the Royal Society's

Maxwell's time at King's was probably the most productive of his career. He was awarded the Royal Society's  This time is especially noteworthy for the advances Maxwell made in the fields of electricity and magnetism. He examined the nature of both electric and magnetic fields in his two-part paper " On physical lines of force", which was published in 1861. In it he provided a conceptual model for

This time is especially noteworthy for the advances Maxwell made in the fields of electricity and magnetism. He examined the nature of both electric and magnetic fields in his two-part paper " On physical lines of force", which was published in 1861. In it he provided a conceptual model for

In 1865 Maxwell resigned the chair at King's College, London, and returned to Glenlair with Katherine. In his paper "On governors" (1868) he mathematically described the behaviour of

In 1865 Maxwell resigned the chair at King's College, London, and returned to Glenlair with Katherine. In his paper "On governors" (1868) he mathematically described the behaviour of

File:Cavendish-3.jpg, Title page of a 1879 copy of ''"The Electrical Researches of the Honourable Henry Cavendish F.R.S,''" edited by Maxwell

File:Maxwell-11.jpg, Title page to a 1882 copy of "''Matter and Motion''"

File:Maxwell-15.jpg, Title page to a 1872 copy of "''Theory of Heat''"

In April 1879 Maxwell began to have difficulty in swallowing, the first symptom of his fatal illness.

Maxwell died in Cambridge of abdominal cancer on 5 November 1879 at the age of 48. His mother had died at the same age of the same type of cancer. The minister who regularly visited him in his last weeks was astonished at his lucidity and the immense power and scope of his memory, but comments more particularly,

As death approached Maxwell told a Cambridge colleague,

Maxwell is buried at Parton Kirk, near

electromagnetic radiation

In physics, electromagnetic radiation (EMR) consists of waves of the electromagnetic (EM) field, which propagate through space and carry momentum and electromagnetic radiant energy. It includes radio waves, microwaves, infrared, (visible ...

, which was the first theory to describe electricity, magnetism

Magnetism is the class of physical attributes that are mediated by a magnetic field, which refers to the capacity to induce attractive and repulsive phenomena in other entities. Electric currents and the magnetic moments of elementary particles ...

and light as different manifestations of the same phenomenon. Maxwell's equations

Maxwell's equations, or Maxwell–Heaviside equations, are a set of coupled partial differential equations that, together with the Lorentz force law, form the foundation of classical electromagnetism, classical optics, and electric circuits.

Th ...

for electromagnetism have been called the " second great unification in physics" where the first one had been realised by Isaac Newton

Sir Isaac Newton (25 December 1642 – 20 March 1726/27) was an English mathematician, physicist, astronomer, alchemist, theologian, and author (described in his time as a " natural philosopher"), widely recognised as one of the g ...

.

With the publication of " A Dynamical Theory of the Electromagnetic Field" in 1865, Maxwell demonstrated that electric and magnetic field

A magnetic field is a vector field that describes the magnetic influence on moving electric charges, electric currents, and magnetic materials. A moving charge in a magnetic field experiences a force perpendicular to its own velocity and to ...

s travel through space as waves moving at the speed of light. He proposed that light is an undulation in the same medium that is the cause of electric and magnetic phenomena. (This article accompanied an 8 December 1864 presentation by Maxwell to the Royal Society. His statement that "light and magnetism are affections of the same substance" is at page 499.) The unification of light and electrical phenomena led to his prediction of the existence of radio wave

Radio waves are a type of electromagnetic radiation with the longest wavelengths in the electromagnetic spectrum, typically with frequencies of 300 gigahertz (GHz) and below. At 300 GHz, the corresponding wavelength is 1 mm (short ...

s. Maxwell is also regarded as a founder of the modern field of electrical engineering

Electrical engineering is an engineering discipline concerned with the study, design, and application of equipment, devices, and systems which use electricity, electronics, and electromagnetism. It emerged as an identifiable occupation in the l ...

.

Maxwell helped develop the Maxwell–Boltzmann distribution, a statistical means of describing aspects of the kinetic theory of gases

Kinetic (Ancient Greek: κίνησις “kinesis”, movement or to move) may refer to:

* Kinetic theory, describing a gas as particles in random motion

* Kinetic energy, the energy of an object that it possesses due to its motion

Art and enter ...

. He is also known for presenting the first durable colour photograph in 1861 and for his foundational work on analysing the rigidity of rod-and-joint frameworks (truss

A truss is an assembly of ''members'' such as beams, connected by ''nodes'', that creates a rigid structure.

In engineering, a truss is a structure that "consists of two-force members only, where the members are organized so that the assembla ...

es) like those in many bridges.

His discoveries helped usher in the era of modern physics, laying the foundation for such fields as special relativity

In physics, the special theory of relativity, or special relativity for short, is a scientific theory regarding the relationship between space and time. In Albert Einstein's original treatment, the theory is based on two postulates:

# The law ...

and quantum mechanics

Quantum mechanics is a fundamental theory in physics that provides a description of the physical properties of nature at the scale of atoms and subatomic particles. It is the foundation of all quantum physics including quantum chemistry, q ...

. Many physicists regard Maxwell as the 19th-century scientist having the greatest influence on 20th-century physics. His contributions to the science are considered by many to be of the same magnitude as those of Isaac Newton and Albert Einstein

Albert Einstein ( ; ; 14 March 1879 – 18 April 1955) was a German-born theoretical physicist, widely acknowledged to be one of the greatest and most influential physicists of all time. Einstein is best known for developing the theor ...

. In the millennium poll—a survey of the 100 most prominent physicists—Maxwell was voted the third greatest physicist of all time, behind only Newton and Einstein. On the centenary of Maxwell's birthday, Einstein described Maxwell's work as the "most profound and the most fruitful that physics has experienced since the time of Newton". Einstein, when he visited the University of Cambridge in 1922, was told by his host that he had done great things because he stood on Newton's shoulders; Einstein replied: "No I don't. I stand on the shoulders of Maxwell."

Life

Early life, 1831–1839

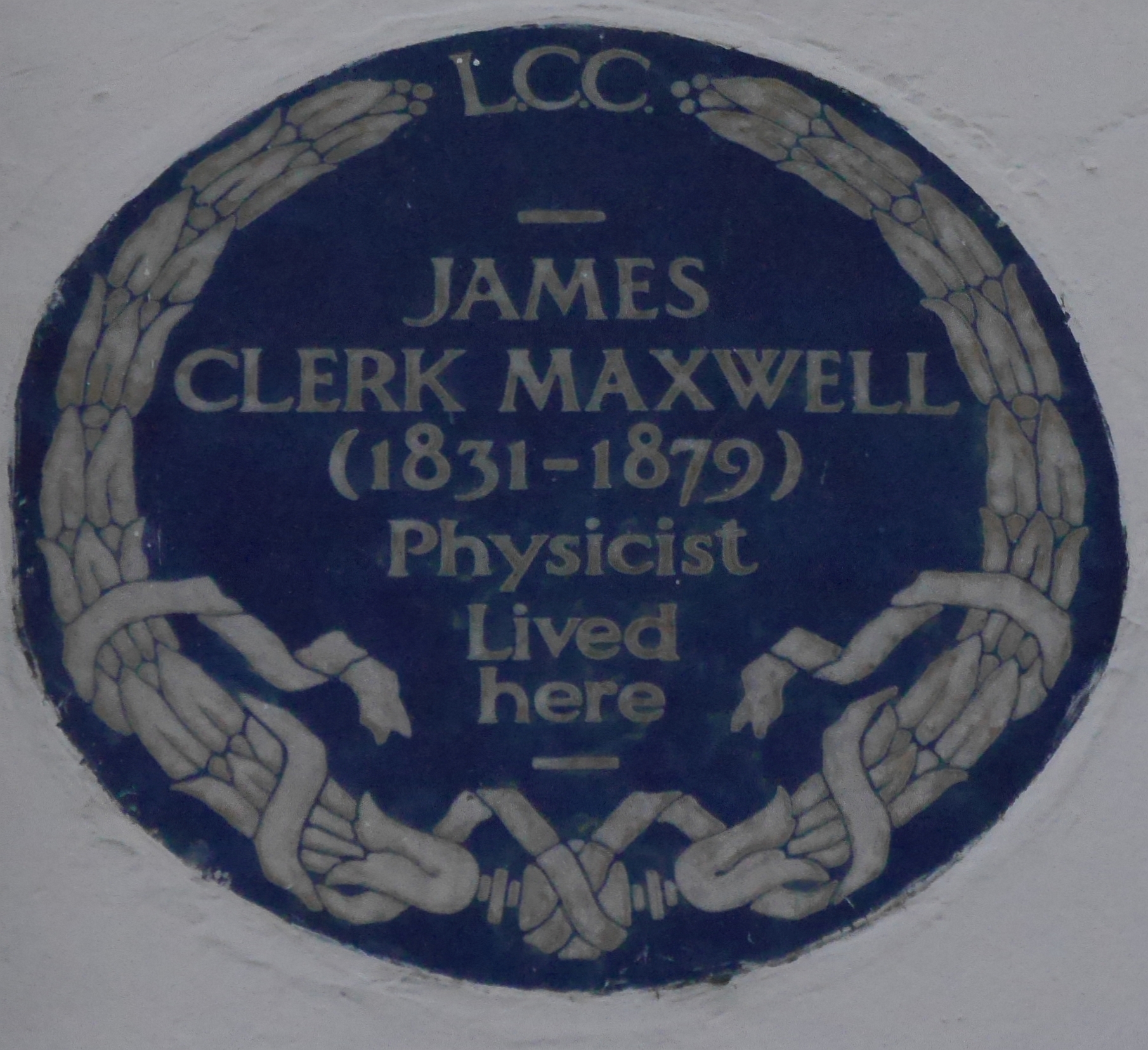

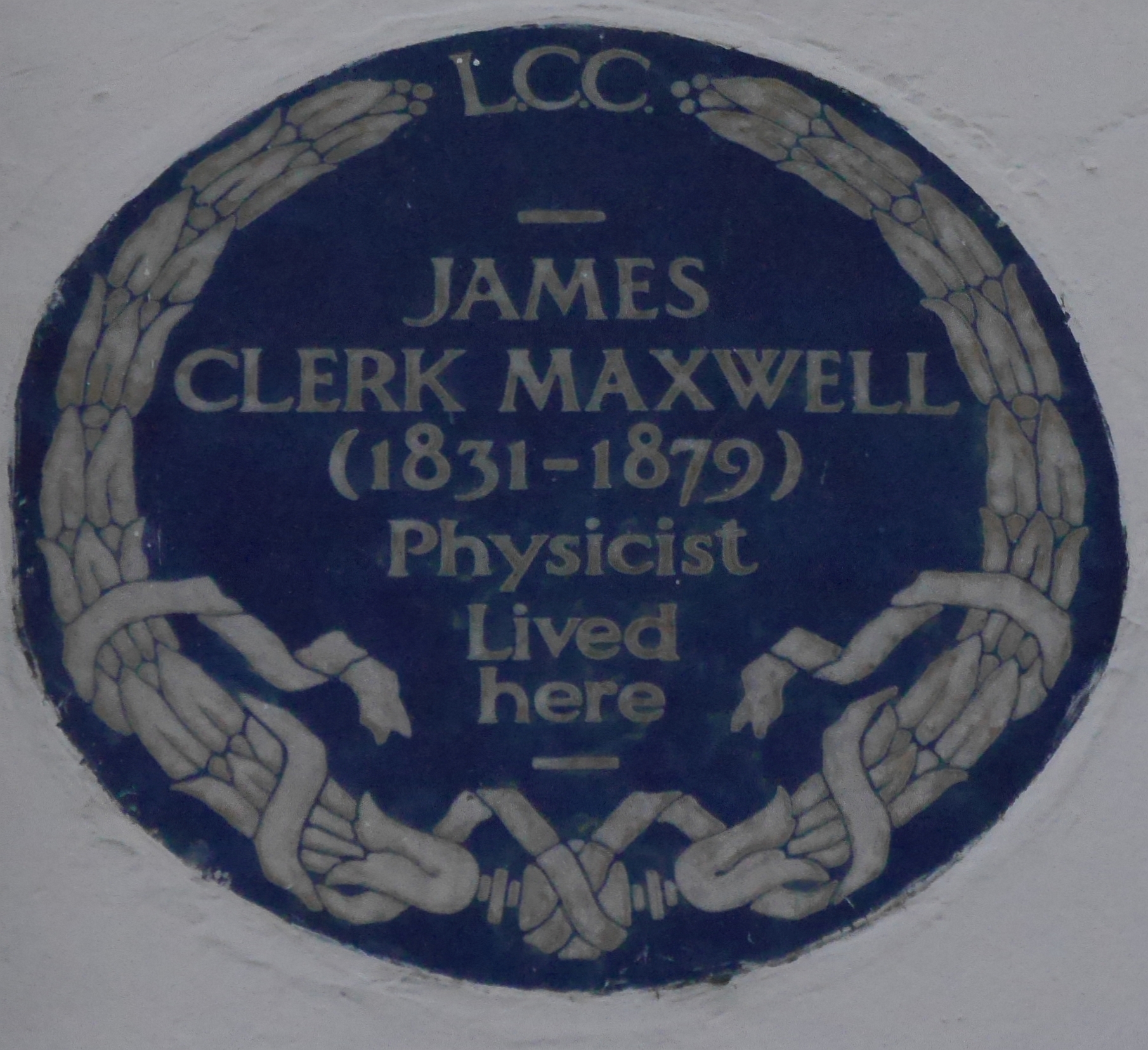

James Clerk Maxwell was born on 13 June 1831 at 14 India Street,

James Clerk Maxwell was born on 13 June 1831 at 14 India Street, Edinburgh

Edinburgh ( ; gd, Dùn Èideann ) is the capital city of Scotland and one of its 32 Council areas of Scotland, council areas. Historically part of the county of Midlothian (interchangeably Edinburghshire before 1921), it is located in Lothian ...

, to John Clerk Maxwell of Middlebie, an advocate, and Frances Cay, daughter of Robert Hodshon Cay

Robert Hodshon Cay FSSA LLD (7 July 1758 – 31 March 1810) was Judge Admiral of Scotland overseeing naval trials. He was husband of the artist Elizabeth Liddell, father of John Cay FRSE and maternal grandfather of James Clerk Maxwell.

Life

C ...

and sister of John Cay

John Lidell Cay FRSE PRSSA (31 August 1790 – 13 December 1865) was a Scottish advocate, pioneer photographer and antiquarian. He served as the Sheriff of Linlithgowshire 1822–65. He was the maternal uncle of James Clerk Maxwell.

He was ...

. (His birthplace now houses a museum operated by the James Clerk Maxwell Foundation.) His father was a man of comfortable means of the Clerk family of Penicuik

Penicuik ( ; sco, Penicuik; gd, Peighinn na Cuthaig) is a town and former burgh in Midlothian, Scotland, lying on the west bank of the River North Esk. It lies on the A701 midway between Edinburgh and Peebles, east of the Pentland Hills.

Nam ...

, holders of the baronetcy

A baronet ( or ; abbreviated Bart or Bt) or the female equivalent, a baronetess (, , or ; abbreviation Btss), is the holder of a baronetcy, a hereditary title awarded by the British Crown. The title of baronet is mentioned as early as the 14th ...

of Clerk of Penicuik. His father's brother was the 6th baronet. He had been born "John Clerk", adding "Maxwell" to his own after he inherited (as an infant in 1793) the Middlebie estate, a Maxwell property in Dumfriesshire. James was a first cousin of both the artist Jemima Blackburn

Jemima Wedderburn Blackburn (1 May 1823 – 9 August 1909) was a Scottish painter whose work illustrated rural life in 19th-century Scotland. One of the most popular illustrators in Victorian Britain, she illustrated 27 books. Her greatest or ...

(the daughter of his father's sister) and the civil engineer William Dyce Cay (the son of his mother's brother). Cay and Maxwell were close friends and Cay acted as his best man when Maxwell married.

Maxwell's parents met and married when they were well into their thirties; his mother was nearly 40 when he was born. They had had one earlier child, a daughter named Elizabeth, who died in infancy.

When Maxwell was young his family moved to Glenlair, in Kirkcudbrightshire, which his parents had built on the estate which comprised . All indications suggest that Maxwell had maintained an unquenchable curiosity from an early age. By the age of three, everything that moved, shone, or made a noise drew the question: "what's the go o' that?" In a passage added to a letter from his father to his sister-in-law Jane Cay in 1834, his mother described this innate sense of inquisitiveness:

Education, 1839–1847

Recognising the boy's potential, Maxwell's mother Frances took responsibility for his early education, which in theVictorian era

In the history of the United Kingdom and the British Empire, the Victorian era was the period of Queen Victoria's reign, from 20 June 1837 until her death on 22 January 1901. The era followed the Georgian period and preceded the Edward ...

was largely the job of the woman of the house. At eight he could recite long passages of John Milton

John Milton (9 December 1608 – 8 November 1674) was an English poet and intellectual. His 1667 epic poem ''Paradise Lost'', written in blank verse and including over ten chapters, was written in a time of immense religious flux and polit ...

and the whole of the 119th psalm (176 verses). Indeed, his knowledge of scripture

Religious texts, including scripture, are texts which various religions consider to be of central importance to their religious tradition. They differ from literature by being a compilation or discussion of beliefs, mythologies, ritual pract ...

was already detailed; he could give chapter and verse for almost any quotation from the psalms. His mother was taken ill with abdominal cancer and, after an unsuccessful operation, died in December 1839 when he was eight years old. His education was then overseen by his father and his father's sister-in-law Jane, both of whom played pivotal roles in his life. His formal schooling began unsuccessfully under the guidance of a 16-year-old hired tutor. Little is known about the young man hired to instruct Maxwell, except that he treated the younger boy harshly, chiding him for being slow and wayward. The tutor was dismissed in November 1841. James' father took him to Robert Davidson's demonstration of electric propulsion and magnetic force on 12 February 1842, an experience with profound implications for the boy.

Maxwell was sent to the prestigious

Maxwell was sent to the prestigious Edinburgh Academy

The Edinburgh Academy is an independent day school in Edinburgh, Scotland, which was opened in 1824. The original building, on Henderson Row in the city's New Town, is now part of the Senior School. The Junior School is located on Arboretum Roa ...

. He lodged during term times at the house of his aunt Isabella. During this time his passion for drawing was encouraged by his older cousin Jemima. The 10-year-old Maxwell, having been raised in isolation on his father's countryside estate, did not fit in well at school. The first year had been full, obliging him to join the second year with classmates a year his senior. His mannerisms and Galloway

Galloway ( ; sco, Gallowa; la, Gallovidia) is a region in southwestern Scotland comprising the counties of Scotland, historic counties of Wigtownshire and Kirkcudbrightshire. It is administered as part of the council areas of Scotland, counci ...

accent struck the other boys as rustic. Having arrived on his first day of school wearing a pair of homemade shoes and a tunic, he earned the unkind nickname of " Daftie". He never seemed to resent the epithet, bearing it without complaint for many years. Social isolation at the Academy ended when he met Lewis Campbell and Peter Guthrie Tait

Peter Guthrie Tait FRSE (28 April 1831 – 4 July 1901) was a Scottish mathematical physicist and early pioneer in thermodynamics. He is best known for the mathematical physics textbook ''Treatise on Natural Philosophy'', which he co-wrote wi ...

, two boys of a similar age who were to become notable scholars later in life. They remained lifelong friends.

Maxwell was fascinated by geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

at an early age, rediscovering the regular polyhedra

A regular polyhedron is a polyhedron whose symmetry group acts transitively on its flags. A regular polyhedron is highly symmetrical, being all of edge-transitive, vertex-transitive and face-transitive. In classical contexts, many different equiv ...

before he received any formal instruction. Despite his winning the school's scripture biography prize in his second year, his academic work remained unnoticed until, at the age of 13, he won the school's mathematical medal and first prize for both English and poetry.

Maxwell's interests ranged far beyond the school syllabus and he did not pay particular attention to examination performance. He wrote his first scientific paper

: ''For a broader class of literature, see Academic publishing.''

Scientific literature comprises scholarly publications that report original empirical and theoretical work in the natural and social sciences. Within an academic field, sci ...

at the age of 14. In it he described a mechanical means of drawing mathematical curves with a piece of twine, and the properties of ellipses, Cartesian ovals

In geometry, a Cartesian oval is a plane curve consisting of points that have the same linear combination of distances from two fixed points (foci). These curves are named after French mathematician René Descartes, who used them in optics.

Def ...

, and related curves with more than two foci. The work, of 1846, "On the description of oval curves and those having a plurality of foci" was presented to the Royal Society of Edinburgh

The Royal Society of Edinburgh is Scotland's national academy of science and letters. It is a registered charity that operates on a wholly independent and non-partisan basis and provides public benefit throughout Scotland. It was established i ...

by James Forbes, a professor of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

, because Maxwell was deemed too young to present the work himself. The work was not entirely original, since René Descartes

René Descartes ( or ; ; Latinized: Renatus Cartesius; 31 March 1596 – 11 February 1650) was a French philosopher, scientist, and mathematician, widely considered a seminal figure in the emergence of modern philosophy and science. Mathe ...

had also examined the properties of such multifocal ellipse

In geometry, the -ellipse is a generalization of the ellipse allowing more than two foci. -ellipses go by numerous other names, including multifocal ellipse, polyellipse, egglipse, -ellipse, and Tschirnhaus'sche Eikurve (after Ehrenfried Walth ...

s in the 17th century, but Maxwell had simplified their construction.

University of Edinburgh, 1847–1850

Maxwell left the Academy in 1847 at age 16 and began attending classes at the

Maxwell left the Academy in 1847 at age 16 and began attending classes at the University of Edinburgh

The University of Edinburgh ( sco, University o Edinburgh, gd, Oilthigh Dhùn Èideann; abbreviated as ''Edin.'' in post-nominals) is a public research university based in Edinburgh, Scotland. Granted a royal charter by King James VI in 15 ...

. He had the opportunity to attend the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

, but decided, after his first term, to complete the full course of his undergraduate studies at Edinburgh. The academic staff of the university included some highly regarded names; his first year tutors included Sir William Hamilton, who lectured him on logic

Logic is the study of correct reasoning. It includes both formal and informal logic. Formal logic is the science of deductively valid inferences or of logical truths. It is a formal science investigating how conclusions follow from premis ...

and metaphysics

Metaphysics is the branch of philosophy that studies the fundamental nature of reality, the first principles of being, identity and change, space and time, causality, necessity, and possibility. It includes questions about the nature of conscio ...

, Philip Kelland on mathematics, and James Forbes on natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

. He did not find his classes demanding, and was therefore able to immerse himself in private study during free time at the university and particularly when back home at Glenlair. There he would experiment with improvised chemical, electric, and magnetic apparatus; however, his chief concerns regarded the properties of polarised light. He constructed shaped blocks of gelatine

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

, subjected them to various stresses, and with a pair of polarising prisms given to him by William Nicol, viewed the coloured fringes that had developed within the jelly. Through this practice he discovered photoelasticity

Photoelasticity describes changes in the optical properties of a material under mechanical deformation. It is a property of all dielectric media and is often used to experimentally determine the stress distribution in a material, where it gives ...

, which is a means of determining the stress distribution within physical structures.

At age 18, Maxwell contributed two papers for the Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. One of these, "On the Equilibrium of Elastic Solids", laid the foundation for an important discovery later in his life, which was the temporary double refraction

Birefringence is the optical property of a material having a refractive index that depends on the polarization and propagation direction of light. These optically anisotropic materials are said to be birefringent (or birefractive). The birefringe ...

produced in viscous

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

Viscosity quantifies the inte ...

liquids by shear stress

Shear stress, often denoted by (Greek: tau), is the component of stress coplanar with a material cross section. It arises from the shear force, the component of force vector parallel to the material cross section. '' Normal stress'', on ...

. His other paper was "Rolling Curves" and, just as with the paper "Oval Curves" that he had written at the Edinburgh Academy, he was again considered too young to stand at the rostrum to present it himself. The paper was delivered to the Royal Society by his tutor Kelland instead.

University of Cambridge, 1850–1856

In October 1850, already an accomplished mathematician, Maxwell left Scotland for the

In October 1850, already an accomplished mathematician, Maxwell left Scotland for the University of Cambridge

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

. He initially attended Peterhouse, but before the end of his first term transferred to Trinity

The Christian doctrine of the Trinity (, from 'threefold') is the central dogma concerning the nature of God in most Christian churches, which defines one God existing in three coequal, coeternal, consubstantial divine persons: God the ...

, where he believed it would be easier to obtain a fellow

A fellow is a concept whose exact meaning depends on context.

In learned or professional societies, it refers to a privileged member who is specially elected in recognition of their work and achievements.

Within the context of higher education ...

ship. At Trinity he was elected to the elite secret society known as the Cambridge Apostles

The Cambridge Apostles (also known as '' Conversazione Society'') is an intellectual society at the University of Cambridge founded in 1820 by George Tomlinson, a Cambridge student who became the first Bishop of Gibraltar.W. C. Lubenow, ''The ...

. Maxwell's intellectual understanding of his Christian faith and of science grew rapidly during his Cambridge years. He joined the "Apostles", an exclusive debating society of the intellectual elite, where through his essays he sought to work out this understanding.

In the summer of his third year, Maxwell spent some time at the Suffolk

Suffolk () is a ceremonial county of England in East Anglia. It borders Norfolk to the north, Cambridgeshire to the west and Essex to the south; the North Sea lies to the east. The county town is Ipswich; other important towns include L ...

home of the Rev C.B. Tayler, the uncle of a classmate, G.W.H. Tayler. The love of God shown by the family impressed Maxwell, particularly after he was nursed back from ill health by the minister and his wife.

On his return to Cambridge, Maxwell writes to his recent host a chatty and affectionate letter including the following testimony,

In November 1851, Maxwell studied under William Hopkins, whose success in nurturing mathematical genius had earned him the nickname of "senior wrangler

The Senior Frog Wrangler is the top mathematics undergraduate at the University of Cambridge in England, a position which has been described as "the greatest intellectual achievement attainable in Britain."

Specifically, it is the person who ...

-maker".

In 1854, Maxwell graduated from Trinity with a degree in mathematics. He scored second highest in the final examination, coming behind Edward Routh and earning himself the title of Second Wrangler. He was later declared equal with Routh in the more exacting ordeal of the Smith's Prize

The Smith's Prize was the name of each of two prizes awarded annually to two research students in mathematics and theoretical physics at the University of Cambridge from 1769. Following the reorganization in 1998, they are now awarded under the ...

examination. Immediately after earning his degree, Maxwell read his paper "On the Transformation of Surfaces by Bending" to the Cambridge Philosophical Society

The Cambridge Philosophical Society (CPS) is a scientific society at the University of Cambridge. It was founded in 1819. The name derives from the medieval use of the word philosophy to denote any research undertaken outside the fields of l ...

. This is one of the few purely mathematical papers he had written, demonstrating his growing stature as a mathematician. Maxwell decided to remain at Trinity after graduating and applied for a fellowship, which was a process that he could expect to take a couple of years. Buoyed by his success as a research student, he would be free, apart from some tutoring and examining duties, to pursue scientific interests at his own leisure.

The nature and perception of colour was one such interest which he had begun at the University of Edinburgh while he was a student of Forbes. With the coloured spinning tops

A spinning top, or simply a top, is a toy with a squat body and a sharp point at the bottom, designed to be spun on its vertical axis, balancing on the tip due to the gyroscopic effect.

Once set in motion, a top will usually wobble for a few se ...

invented by Forbes, Maxwell was able to demonstrate that white light would result from a mixture of red, green, and blue light. His paper "Experiments on Colour" laid out the principles of colour combination and was presented to the Royal Society of Edinburgh in March 1855. Maxwell was this time able to deliver it himself.

Maxwell was made a fellow of Trinity on 10 October 1855, sooner than was the norm, and was asked to prepare lectures on hydrostatics and optics

Optics is the branch of physics that studies the behaviour and properties of light, including its interactions with matter and the construction of instruments that use or detect it. Optics usually describes the behaviour of visible, ultra ...

and to set examination papers. The following February he was urged by Forbes to apply for the newly vacant Chair

A chair is a type of seat, typically designed for one person and consisting of one or more legs, a flat or slightly angled seat and a back-rest. They may be made of wood, metal, or synthetic materials, and may be padded or upholstered in vari ...

of Natural Philosophy at Marischal College

Marischal College ( ) is a large granite building on Broad Street in the centre of Aberdeen in north-east Scotland, and since 2011 has acted as the headquarters of Aberdeen City Council. However, the building was constructed for and is on long- ...

, Aberdeen

Aberdeen (; sco, Aiberdeen ; gd, Obar Dheathain ; la, Aberdonia) is a city in North East Scotland, and is the third most populous city in the country. Aberdeen is one of Scotland's 32 local government council areas (as Aberdeen City), ...

. His father assisted him in the task of preparing the necessary references, but died on 2 April at Glenlair before either knew the result of Maxwell's candidacy. He accepted the professorship at Aberdeen, leaving Cambridge in November 1856.

Marischal College, Aberdeen, 1856–1860

The 25-year-old Maxwell was a good 15 years younger than any other professor at Marischal. He engaged himself with his new responsibilities as head of a department, devising the syllabus and preparing lectures. He committed himself to lecturing 15 hours a week, including a weekly '' pro bono'' lecture to the local working men's college. He lived in Aberdeen with his cousin William Dyce Cay, a Scottish civil engineer, during the six months of the academic year and spent the summers at Glenlair, which he had inherited from his father.

The 25-year-old Maxwell was a good 15 years younger than any other professor at Marischal. He engaged himself with his new responsibilities as head of a department, devising the syllabus and preparing lectures. He committed himself to lecturing 15 hours a week, including a weekly '' pro bono'' lecture to the local working men's college. He lived in Aberdeen with his cousin William Dyce Cay, a Scottish civil engineer, during the six months of the academic year and spent the summers at Glenlair, which he had inherited from his father.

He focused his attention on a problem that had eluded scientists for 200 years: the nature of

He focused his attention on a problem that had eluded scientists for 200 years: the nature of Saturn's rings

The rings of Saturn are the most extensive ring system of any planet in the Solar System. They consist of countless small particles, ranging in size from micrometers to meters, that orbit around Saturn. The ring particles are made almost entir ...

. It was unknown how they could remain stable without breaking up, drifting away or crashing into Saturn. The problem took on a particular resonance at that time because St John's College, Cambridge

St John's College is a constituent college of the University of Cambridge founded by the Tudor matriarch Lady Margaret Beaufort. In constitutional terms, the college is a charitable corporation established by a charter dated 9 April 1511. Th ...

, had chosen it as the topic for the 1857 Adams Prize. Maxwell devoted two years to studying the problem, proving that a regular solid ring could not be stable, while a fluid ring would be forced by wave action to break up into blobs. Since neither was observed, he concluded that the rings must be composed of numerous small particles he called "brick-bats", each independently orbiting Saturn. Maxwell was awarded the £130 Adams Prize in 1859 for his essay "On the stability of the motion of Saturn's rings"; he was the only entrant to have made enough headway to submit an entry. His work was so detailed and convincing that when George Biddell Airy

Sir George Biddell Airy (; 27 July 18012 January 1892) was an English mathematician and astronomer, and the seventh Astronomer Royal from 1835 to 1881. His many achievements include work on planetary orbits, measuring the mean density of the ...

read it he commented, "It is one of the most remarkable applications of mathematics to physics that I have ever seen." It was considered the final word on the issue until direct observations by the ''Voyager

Voyager may refer to:

Computing and communications

* LG Voyager, a mobile phone model manufactured by LG Electronics

* NCR Voyager, a computer platform produced by NCR Corporation

* Voyager (computer worm), a computer worm affecting Oracle ...

'' flybys of the 1980s confirmed Maxwell's prediction that the rings were composed of particles. It is now understood, however, that the rings' particles are not stable at all, being pulled by gravity onto Saturn. The rings are expected to vanish entirely over the next 300 million years.

In 1857 Maxwell befriended the Reverend Daniel Dewar, who was then the Principal of Marischal. Through him Maxwell met Dewar's daughter, Katherine Mary Dewar. They were engaged in February 1858 and married in Aberdeen on 2 June 1858. On the marriage record, Maxwell is listed as Professor of Natural Philosophy in Marischal College, Aberdeen. Katherine was seven years Maxwell's senior. Comparatively little is known of her, although it is known that she helped in his lab and worked on experiments in viscosity

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

Viscosity quantifies the inte ...

. Maxwell's biographer and friend, Lewis Campbell, adopted an uncharacteristic reticence on the subject of Katherine, though describing their married life as "one of unexampled devotion".

In 1860 Marischal College merged with the neighbouring King's College King's College or The King's College refers to two higher education institutions in the United Kingdom:

*King's College, Cambridge, a constituent of the University of Cambridge

*King's College London, a constituent of the University of London

It ca ...

to form the University of Aberdeen

, mottoeng = The fear of the Lord is the beginning of wisdom

, established =

, type = Public research universityAncient university

, endowment = £58.4 million (2021)

, budget ...

. There was no room for two professors of Natural Philosophy, so Maxwell, despite his scientific reputation, found himself laid off. He was unsuccessful in applying for Forbes's recently vacated chair at Edinburgh, the post instead going to Tait. Maxwell was granted the Chair of Natural Philosophy at King's College, London

King's College London (informally King's or KCL) is a public research university located in London, England. King's was established by royal charter in 1829 under the patronage of King George IV and the Duke of Wellington. In 1836, King' ...

, instead. After recovering from a near-fatal bout of smallpox

Smallpox was an infectious disease caused by variola virus (often called smallpox virus) which belongs to the genus Orthopoxvirus. The last naturally occurring case was diagnosed in October 1977, and the World Health Organization (WHO) ce ...

in 1860, he moved to London with his wife.

King's College, London, 1860–1865

Maxwell's time at King's was probably the most productive of his career. He was awarded the Royal Society's

Maxwell's time at King's was probably the most productive of his career. He was awarded the Royal Society's Rumford Medal

The Rumford Medal is an award bestowed by Britain's Royal Society every alternating year for "an outstandingly important recent discovery in the field of thermal or optical properties of matter made by a scientist working in Europe".

First awar ...

in 1860 for his work on colour and was later elected to the Society in 1861. This period of his life would see him display the world's first light-fast colour photograph, further develop his ideas on the viscosity

The viscosity of a fluid is a measure of its resistance to deformation at a given rate. For liquids, it corresponds to the informal concept of "thickness": for example, syrup has a higher viscosity than water.

Viscosity quantifies the inte ...

of gases, and propose a system of defining physical quantities—now known as dimensional analysis

In engineering and science, dimensional analysis is the analysis of the relationships between different physical quantities by identifying their base quantities (such as length, mass, time, and electric current) and units of measure (such as ...

. Maxwell would often attend lectures at the Royal Institution

The Royal Institution of Great Britain (often the Royal Institution, Ri or RI) is an organisation for scientific education and research, based in the City of Westminster. It was founded in 1799 by the leading British scientists of the age, inc ...

, where he came into regular contact with Michael Faraday

Michael Faraday (; 22 September 1791 – 25 August 1867) was an English scientist who contributed to the study of electromagnetism and electrochemistry. His main discoveries include the principles underlying electromagnetic inductio ...

. The relationship between the two men could not be described as being close, because Faraday was 40 years Maxwell's senior and showed signs of senility. They nevertheless maintained a strong respect for each other's talents.

This time is especially noteworthy for the advances Maxwell made in the fields of electricity and magnetism. He examined the nature of both electric and magnetic fields in his two-part paper " On physical lines of force", which was published in 1861. In it he provided a conceptual model for

This time is especially noteworthy for the advances Maxwell made in the fields of electricity and magnetism. He examined the nature of both electric and magnetic fields in his two-part paper " On physical lines of force", which was published in 1861. In it he provided a conceptual model for electromagnetic induction

Electromagnetic or magnetic induction is the production of an electromotive force (emf) across an electrical conductor in a changing magnetic field.

Michael Faraday is generally credited with the discovery of induction in 1831, and James Cle ...

, consisting of tiny spinning cells of magnetic flux. Two more parts were later added to and published in that same paper in early 1862. In the first additional part he discussed the nature of electrostatics

Electrostatics is a branch of physics that studies electric charges at rest (static electricity).

Since classical times, it has been known that some materials, such as amber, attract lightweight particles after rubbing. The Greek word for am ...

and displacement current

In electromagnetism, displacement current density is the quantity appearing in Maxwell's equations that is defined in terms of the rate of change of , the electric displacement field. Displacement current density has the same units as electr ...

. In the second additional part, he dealt with the rotation of the plane of the polarisation of light in a magnetic field, a phenomenon that had been discovered by Faraday and is now known as the Faraday effect

The Faraday effect or Faraday rotation, sometimes referred to as the magneto-optic Faraday effect (MOFE), is a physical magneto-optical phenomenon. The Faraday effect causes a polarization rotation which is proportional to the projection of the ...

.

Later years, 1865–1879

In 1865 Maxwell resigned the chair at King's College, London, and returned to Glenlair with Katherine. In his paper "On governors" (1868) he mathematically described the behaviour of

In 1865 Maxwell resigned the chair at King's College, London, and returned to Glenlair with Katherine. In his paper "On governors" (1868) he mathematically described the behaviour of governors

A governor is an administrative leader and head of a polity or political region, ranking under the head of state and in some cases, such as governors-general, as the head of state's official representative. Depending on the type of political r ...

—devices that control the speed of steam engines—thereby establishing the theoretical basis of control engineering. In his paper "On reciprocal figures, frames and diagrams of forces" (1870) he discussed the rigidity of various designs of lattice. He wrote the textbook ''Theory of Heat'' (1871) and the treatise ''Matter and Motion'' (1876). Maxwell was also the first to make explicit use of dimensional analysis

In engineering and science, dimensional analysis is the analysis of the relationships between different physical quantities by identifying their base quantities (such as length, mass, time, and electric current) and units of measure (such as ...

, in 1871.

In 1871 he returned to Cambridge to become the first Cavendish Professor of Physics The Cavendish Professorship is one of the senior faculty positions in physics at the University of Cambridge. It was founded on 9 February 1871 alongside the famous Cavendish Laboratory, which was completed three years later. William Cavendish, 7th ...

. Maxwell was put in charge of the development of the Cavendish Laboratory

The Cavendish Laboratory is the Department of Physics at the University of Cambridge, and is part of the School of Physical Sciences. The laboratory was opened in 1874 on the New Museums Site as a laboratory for experimental physics and is name ...

, supervising every step in the progress of the building and of the purchase of the collection of apparatus. One of Maxwell's last great contributions to science was the editing (with copious original notes) of the research of Henry Cavendish

Henry Cavendish ( ; 10 October 1731 – 24 February 1810) was an English natural philosopher and scientist who was an important experimental and theoretical chemist and physicist. He is noted for his discovery of hydrogen, which he termed "infl ...

, from which it appeared that Cavendish researched, amongst other things, such questions as the density

Density (volumetric mass density or specific mass) is the substance's mass per unit of volume. The symbol most often used for density is ''ρ'' (the lower case Greek letter rho), although the Latin letter ''D'' can also be used. Mathematicall ...

of the Earth and the composition of water. He was elected as a member to the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communi ...

in 1876.Castle Douglas

Castle Douglas ( gd, Caisteal Dhùghlais) is a town in Dumfries and Galloway, Scotland. It lies in the lieutenancy area of Kirkcudbrightshire, in the eastern part of Galloway, between the towns of Dalbeattie and Gatehouse of Fleet. It is in the ...

in Galloway close to where he grew up. The extended biography ''The Life of James Clerk Maxwell'', by his former schoolfellow and lifelong friend Professor Lewis Campbell, was published in 1882. His collected works were issued in two volumes by the Cambridge University Press

Cambridge University Press is the university press of the University of Cambridge. Granted letters patent by Henry VIII of England, King Henry VIII in 1534, it is the oldest university press in the world. It is also the King's Printer.

Cambr ...

in 1890.

The executors of Maxwell's estate were his physician George Edward Paget, G. G. Stokes, and Colin Mackenzie, who was Maxwell's cousin. Overburdened with work, Stokes passed Maxwell's papers to William Garnett, who had effective custody of the papers until about 1884.

There is a memorial inscription to him near the choir screen at Westminster Abbey

Westminster Abbey, formally titled the Collegiate Church of Saint Peter at Westminster, is an historic, mainly Gothic church in the City of Westminster, London, England, just to the west of the Palace of Westminster. It is one of the United ...

.

Personal life

As a great lover ofScottish poetry

Poetry of Scotland includes all forms of verse written in Brythonic, Latin, Scottish Gaelic, Scots, French, English and Esperanto and any language in which poetry has been written within the boundaries of modern Scotland, or by Scottish people.

...

, Maxwell memorised poems and wrote his own. The best known is ''Rigid Body Sings'', closely based on "Comin' Through the Rye

"Comin' Thro' the Rye" is a poem written in 1782 by Robert Burns (1759–1796). The words are put to the melody of the Scottish Minstrel "Common' Frae The Town". This is a variant of the tune to which " Auld Lang Syne" is usually sung—the melodi ...

" by Robert Burns

Robert Burns (25 January 175921 July 1796), also known familiarly as Rabbie Burns, was a Scottish poet and lyricist. He is widely regarded as the national poet of Scotland and is celebrated worldwide. He is the best known of the poets who ha ...

, which he apparently used to sing while accompanying himself on a guitar. It has the opening lines

A collection of his poems was published by his friend Lewis Campbell in 1882.

Descriptions of Maxwell remark upon his remarkable intellectual qualities being matched by social awkwardness.

Maxwell was an evangelical Presbyterian

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their na ...

and in his later years became an Elder

An elder is someone with a degree of seniority or authority.

Elder or elders may refer to:

Positions Administrative

* Elder (administrative title), a position of authority

Cultural

* North American Indigenous elder, a person who has and tr ...

of the Church of Scotland

The Church of Scotland ( sco, The Kirk o Scotland; gd, Eaglais na h-Alba) is the national church in Scotland.

The Church of Scotland was principally shaped by John Knox, in the Scottish Reformation, Reformation of 1560, when it split from t ...

. Maxwell's religious beliefs and related activities have been the focus of a number of papers. Attending both Church of Scotland (his father's denomination) and Episcopalian (his mother's denomination) services as a child, Maxwell underwent an evangelical

Evangelicalism (), also called evangelical Christianity or evangelical Protestantism, is a worldwide interdenominational movement within Protestant Christianity that affirms the centrality of being " born again", in which an individual exp ...