James Clark McReynolds on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

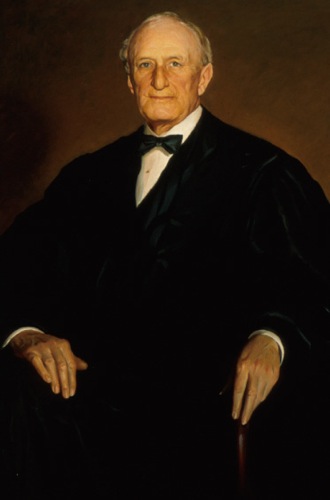

James Clark McReynolds (February 3, 1862 – August 24, 1946) was an American

alternative link to the full paper, and the extensive quoted content under Further reading

See also the four-part WNET-Thirteen.org video series to which these materials are attached, Born in

Born in

Born in

While in private practice, McReynolds was retained by the government in matters relating to enforcement of

While in private practice, McReynolds was retained by the government in matters relating to enforcement of

In his 27 years on the bench, McReynolds wrote 506 decisions, an average of just under 19 opinions for each term of the Court during his tenure. In addition, he authored 157 dissents, 93 of which were against the New Deal.

McReynolds's fierce opposition to

In his 27 years on the bench, McReynolds wrote 506 decisions, an average of just under 19 opinions for each term of the Court during his tenure. In addition, he authored 157 dissents, 93 of which were against the New Deal.

McReynolds's fierce opposition to  McReynolds wrote two early decisions using the Fourteenth Amendment to protect

McReynolds wrote two early decisions using the Fourteenth Amendment to protect

Taft wrote that although he considered McReynolds an "able man", he found him to be "selfish to the last degree ... fuller of prejudice than any man I have ever known ... one who delights in making others uncomfortable. He has no sense of duty ... really seems to have less of a loyal spirit to the Court than anybody." In 1929 McReynolds asked Taft to announce opinions assigned to him (McReynolds), explaining that "an imperious voice has called me out of town. I don't think my sudden illness will prove fatal, but strange things some time ichappen around Thanksgiving." Duck hunting season had opened and McReynolds was off to Maryland for some shooting. In 1925, he left so suddenly on a similar errand that he had no opportunity to notify the Chief Justice of his departure. Taft was infuriated as two important decisions he wanted to deliver were delayed because McReynolds had not handed in a dissent before leaving.

McReynolds went on tirades about "un-Americans" and "political subversives." Known as a blatant

Taft wrote that although he considered McReynolds an "able man", he found him to be "selfish to the last degree ... fuller of prejudice than any man I have ever known ... one who delights in making others uncomfortable. He has no sense of duty ... really seems to have less of a loyal spirit to the Court than anybody." In 1929 McReynolds asked Taft to announce opinions assigned to him (McReynolds), explaining that "an imperious voice has called me out of town. I don't think my sudden illness will prove fatal, but strange things some time ichappen around Thanksgiving." Duck hunting season had opened and McReynolds was off to Maryland for some shooting. In 1925, he left so suddenly on a similar errand that he had no opportunity to notify the Chief Justice of his departure. Taft was infuriated as two important decisions he wanted to deliver were delayed because McReynolds had not handed in a dissent before leaving.

McReynolds went on tirades about "un-Americans" and "political subversives." Known as a blatant

alternative link to the full paper

Bibliography on James Clark McReynolds at 6th Circuit

United States Court of Appeals.

Biography, James Clark McReynolds at Federal Judicial Center

* Supreme Court Historical Society

James C. McReynolds.

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:McReynolds, James Clark 1862 births 1946 deaths 20th-century American judges 20th-century American politicians American Disciples of Christ American legal scholars American members of the Churches of Christ American people of Scotch-Irish descent Kentucky Democrats People from Elkton, Kentucky Tennessee Democrats Tennessee lawyers United States Assistant Attorneys General United States Attorneys General United States federal judges appointed by Woodrow Wilson Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States Vanderbilt University Law School faculty University of Virginia School of Law alumni Woodrow Wilson administration cabinet members Cravath, Swaine & Moore people Old Right (United States) Antisemitism in the United States

lawyer

A lawyer is a person who practices law. The role of a lawyer varies greatly across different legal jurisdictions. A lawyer can be classified as an advocate, attorney, barrister, canon lawyer, civil law notary, counsel, counselor, solic ...

and judge

A judge is a person who presides over court proceedings, either alone or as a part of a panel of judges. A judge hears all the witnesses and any other evidence presented by the barristers or solicitors of the case, assesses the credibility an ...

from Tennessee who served as United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

under President Woodrow Wilson

Thomas Woodrow Wilson (December 28, 1856February 3, 1924) was an American politician and academic who served as the 28th president of the United States from 1913 to 1921. A member of the Democratic Party, Wilson served as the president of ...

and as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 18 ...

. He served on the Court from 1914 to his retirement in 1941. McReynolds is best known today for his sustained opposition to the domestic programs of President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

and his personality, which was widely viewed negatively and included documented elements of overt antisemitism

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and racism

Racism is the belief that groups of humans possess different behavioral traits corresponding to inherited attributes and can be divided based on the superiority of one race over another. It may also mean prejudice, discrimination, or antagonism ...

. See also thialternative link to the full paper, and the extensive quoted content under Further reading

See also the four-part WNET-Thirteen.org video series to which these materials are attached, Born in

Elkton, Kentucky

Elkton is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Todd County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,062 at the 2010 census.

History

The city was founded by Major John Gray and established by the state assembly in 1820. It is ...

, McReynolds practiced law in Tennessee after graduating from the University of Virginia School of Law

The University of Virginia School of Law (Virginia Law or UVA Law) is the law school of the University of Virginia, a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson as part of his "academical v ...

. He served as the U.S. Assistant Attorney General

Many of the divisions and offices of the United States Department of Justice are headed by an assistant attorney general.

The president of the United States appoints individuals to the position of assistant attorney general with the advice and ...

during President Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

's administration and became well known for his skill in antitrust

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

cases. After Wilson took office in 1913, he appointed McReynolds as his administration's first attorney general. Wilson nominated McReynolds to the Supreme Court in 1914 to fill the vacancy caused Associate Justice Horace Harmon Lurton

Horace Harmon Lurton (February 26, 1844 – July 12, 1914) was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and previously was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and of t ...

's death.

In his 26 years on the bench, McReynolds wrote 506 majority opinions for the Court and 157 dissents, 93 of which were against the New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

. He was part of the "Four Horsemen

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are figures in the Christian scriptures, first appearing in the Book of Revelation, a piece of apocalypse literature written by John of Patmos.

Revelation 6 tells of a book or scroll in God's right hand tha ...

" bloc of conservative justices who frequently voted to strike down New Deal programs. He assumed senior status

Senior status is a form of semi-retirement for United States federal judges. To qualify, a judge in the Federal judiciary of the United States, federal court system must be at least 65 years old, and the sum of the judge's age and years of servi ...

in 1941 and was succeeded by James F. Byrnes

James Francis Byrnes ( ; May 2, 1882 – April 9, 1972) was an American judge and politician from South Carolina. A member of the Democratic Party, he served in U.S. Congress and on the U.S. Supreme Court, as well as in the executive branch, ...

. During his Supreme Court tenure, McReynolds wrote the majority opinion in cases such as ''Meyer v. Nebraska

''Meyer v. Nebraska'', 262 U.S. 390 (1923), was a U.S. Supreme Court case that held that a 1919 Nebraska law restricting foreign-language education violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. ...

'', ''United States v. Miller

''United States v. Miller'', 307 U.S. 174 (1939), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that involved a Second Amendment to the United States Constitution challenge to the National Firearms Act of 1934 (NFA). The cas ...

'', '' Adams v. Tanner'', and ''Pierce v. Society of Sisters

''Pierce v. Society of Sisters'', 268 U.S. 510 (1925), was an early 20th-century United States Supreme Court decision striking down an Oregon statute that required all children to attend public school. The decision significantly expanded coverage ...

''. Due to his bigotry and temperament, McReynolds is sometimes included on lists of the worst Supreme Court justices.

Early life

Born in

Born in Elkton, Kentucky

Elkton is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Todd County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,062 at the 2010 census.

History

The city was founded by Major John Gray and established by the state assembly in 1820. It is ...

, the county seat of Todd County, McReynolds was the son of John Oliver and Ellen (née Reeves) McReynolds, both members of the Disciples of Christ

The Christian Church (Disciples of Christ) is a mainline Protestant Christian denomination in the United States and Canada. The denomination started with the Restoration Movement during the Second Great Awakening, first existing during the 19th ...

church. John Oliver McReynolds was active in business ventures and served as a surgeon in the Confederate army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

during the Civil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

. The house where James Clark McReynolds was born still stands; it was listed on the National Register of Historic Places

The National Register of Historic Places (NRHP) is the United States federal government's official list of districts, sites, buildings, structures and objects deemed worthy of preservation for their historical significance or "great artistic v ...

in 1976. He graduated from the prestigious Green River Academy and later matriculated at Vanderbilt University

Vanderbilt University (informally Vandy or VU) is a private research university in Nashville, Tennessee. Founded in 1873, it was named in honor of shipping and rail magnate Cornelius Vanderbilt, who provided the school its initial $1-million ...

, graduating with status one year later as a valedictorian

Valedictorian is an academic title for the highest-performing student of a graduating class of an academic institution.

The valedictorian is commonly determined by a numerical formula, generally an academic institution's grade point average (GPA ...

in 1882. At the University of Virginia School of Law

The University of Virginia School of Law (Virginia Law or UVA Law) is the law school of the University of Virginia, a public research university in Charlottesville, Virginia. It was founded in 1819 by Thomas Jefferson as part of his "academical v ...

, where he studied under John B. Minor, "a man of stern morality and firm conservative convictions", McReynolds completed his studies in 14 months. He again graduated at the head of his class, receiving his law degree in 1884.

McReynolds was secretary to Senator Howell Edmunds Jackson

Howell Edmunds Jackson (April 8, 1832 – August 8, 1895) was an American attorney, politician, and jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1893 until his death in 1895. His brief tenure on the ...

, who later became an associate justice, in 1893. He practiced law in Nashville and served for three years as an adjunct professor

An adjunct professor is a type of academic appointment in higher education who does not work at the establishment full-time. The terms of this appointment and

the job security of the tenure vary in different parts of the world, however the genera ...

of commercial law

Commercial law, also known as mercantile law or trade law, is the body of law that applies to the rights, relations, and conduct of persons and business engaged in commerce, merchandising, trade, and sales. It is often considered to be a branc ...

, insurance

Insurance is a means of protection from financial loss in which, in exchange for a fee, a party agrees to compensate another party in the event of a certain loss, damage, or injury. It is a form of risk management, primarily used to hedge ...

, and corporations

A corporation is an organization—usually a group of people or a company—authorized by the state to act as a single entity (a legal entity recognized by private and public law "born out of statute"; a legal person in legal context) and r ...

at Vanderbilt University Law School

Vanderbilt University Law School (also known as Vanderbilt Law School or VLS) is a graduate school of Vanderbilt University. Established in 1874, it is one of the oldest law schools in the southern United States. Vanderbilt Law School has consiste ...

.

McReynolds became active in politics, running unsuccessfully for Congress in 1896 as a "Goldbug" Democrat.See free silver

Free silver was a major economic policy issue in the United States in the late 19th-century. Its advocates were in favor of an expansionary monetary policy featuring the unlimited coinage of silver into money on-demand, as opposed to strict adhe ...

. As head of the Tennessee delegation to the 1896 Democratic Convention, he wrote the party's "sound money" plank. Under Theodore Roosevelt

Theodore Roosevelt Jr. ( ; October 27, 1858 – January 6, 1919), often referred to as Teddy or by his initials, T. R., was an American politician, statesman, soldier, conservationist, naturalist, historian, and writer who served as the 26t ...

, McReynolds served as Assistant Attorney General

Many of the divisions and offices of the United States Department of Justice are headed by an assistant attorney general.

The president of the United States appoints individuals to the position of assistant attorney general with the advice and ...

from 1903 to 1907, when he resigned to take up private practice with the law firm of Guthrie, Cravath, and Henderson (later renamed Cravath, Swaine & Moore

Cravath, Swaine & Moore LLP (known as Cravath) is an American white-shoe law firm with its headquarters in New York City, and an additional office in London. The firm is known for its complex and high profile litigation and mergers & acquisitions ...

) in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

.

Attorney General

While in private practice, McReynolds was retained by the government in matters relating to enforcement of

While in private practice, McReynolds was retained by the government in matters relating to enforcement of antitrust

Competition law is the field of law that promotes or seeks to maintain market competition by regulating anti-competitive conduct by companies. Competition law is implemented through public and private enforcement. It is also known as antitrust l ...

laws, particularly in proceedings against the "Tobacco trust" (see ''United States v. American Tobacco Co.

''United States v. American Tobacco Company'', , was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court, which held that the combination in this case is one in restraint of trade and an attempt to monopolize the busin ...

'', 221 U.S. 106 (1911)) and the combination of the anthracite coal

Anthracite, also known as hard coal, and black coal, is a hard, compact variety of coal that has a submetallic luster. It has the highest carbon content, the fewest impurities, and the highest energy density of all types of coal and is the high ...

railroads. The case that brought him to President Wilson's attention was the government's case against the American Tobacco Company

The American Tobacco Company was a tobacco company founded in 1890 by J. B. Duke through a merger between a number of U.S. tobacco manufacturers including Allen and Ginter and Goodwin & Company. The company was one of the original 12 members of ...

, in which McReynolds presented the government's case while the company was represented by Clarence Darrow

Clarence Seward Darrow (; April 18, 1857 – March 13, 1938) was an American lawyer who became famous in the early 20th century for his involvement in the Leopold and Loeb murder trial and the Scopes "Monkey" Trial. He was a leading member of t ...

and 17 other attorneys.

On March 15, 1913, after the successful conclusion of that case, on Attorney General Wickersham's recommendation, Wilson appointed McReynolds as the 48th United States Attorney General

The United States attorney general (AG) is the head of the United States Department of Justice, and is the chief law enforcement officer of the federal government of the United States. The attorney general serves as the principal advisor to the p ...

; he served until August 29, 1914. During his time in private practice, McReynolds earned a reputation as an ardent "trust buster", and he continued working against trusts during his time as attorney general. Despite his negative views of corporate monopolies, McReynolds was very supportive of laissez-faire economic policies. Wilson found him difficult to work with.

Supreme Court

On August 19, 1914, Wilsonnominated

A candidate, or nominee, is the prospective recipient of an award or honor, or a person seeking or being considered for some kind of position; for example:

* to be elected to an office — in this case a candidate selection procedure occurs.

* ...

McReynolds as an associate justice of the United States Supreme Court

An associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States is any member of the Supreme Court of the United States other than the chief justice of the United States. The number of associate justices is eight, as set by the Judiciary Act of 1 ...

, to succeed Horace H. Lurton

Horace Harmon Lurton (February 26, 1844 – July 12, 1914) was an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States and previously was a United States circuit judge of the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit and of t ...

. The United States Senate

The United States Senate is the upper chamber of the United States Congress, with the House of Representatives being the lower chamber. Together they compose the national bicameral legislature of the United States.

The composition and pow ...

confirmed him on August 29, by a 44–6 vote, and he was sworn into office on October 12.

When the Supreme Court Building opened in 1935 during the Great Depression, McReynolds, like most of the other justices, refused to move his office into the new building. He continued to work out of the office he maintained in his apartment. He said that, with the country in economic turmoil, the government should not have spent so much money on a single building.

Important opinions

Franklin Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

's New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

legislation designed to provide relief to citizens and put people to work during the Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

resulted in his being classified as one of the "Four Horsemen

The Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse are figures in the Christian scriptures, first appearing in the Book of Revelation, a piece of apocalypse literature written by John of Patmos.

Revelation 6 tells of a book or scroll in God's right hand tha ...

", along with George Sutherland

George Alexander Sutherland (March 25, 1862July 18, 1942) was an English-born American jurist and politician. He served as an associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court between 1922 and 1938. As a member of the Republican Party, he also repre ...

, Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1911 to 1937. He was a staunch conservative and was regarded as a part of the Four ...

and Pierce Butler Pierce or Piers Butler may refer to:

*Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467 – 26 August 1539), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

*Piers Butler, 3rd Viscount Galmoye (1652–1740), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

* P ...

. McReynolds voted to strike down the Tennessee Valley Authority

The Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA) is a federally owned electric utility corporation in the United States. TVA's service area covers all of Tennessee, portions of Alabama, Mississippi, and Kentucky, and small areas of Georgia, North Carolina ...

in '' Ashwander v. TVA'', the National Industrial Recovery Act

The National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933 (NIRA) was a US labor law and consumer law passed by the 73rd US Congress to authorize the president to regulate industry for fair wages and prices that would stimulate economic recovery. It also e ...

in ''Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States

''A.L.A. Schechter Poultry Corp. v. United States'', 295 U.S. 495 (1935), was a decision by the Supreme Court of the United States that invalidated regulations of the poultry industry according to the nondelegation doctrine and as an invalid use ...

'', the Agricultural Adjustment Act of 1933 in ''United States v. Butler

''United States v. Butler'', 297 U.S. 1 (1936), is a U.S. Supreme Court case that held that the U.S. Congress has not only the power to lay taxes to the level necessary to carry out its other powers enumerated in Article I of the U.S. Constituti ...

'', the Bituminous Coal Conservation Act of 1935 in '' Carter v. Carter Coal Co.'', and the Social Security Act

The Social Security Act of 1935 is a law enacted by the 74th United States Congress and signed into law by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The law created the Social Security program as well as insurance against unemployment. The law was pa ...

, 42 U.S.C. § 301 ''et seq.'', in ''Steward Machine Co. v. Davis

''Steward Machine Company v. Davis'', 301 U.S. 548 (1937), was a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the unemployment compensation provisions of the Social Security Act of 1935, which established the Federal Unemployment Tax Act, federal ta ...

'', 301 U.S. 548 (1937). He continued to vote against New Deal measures after most of the Court shifted in 1937 to upholding New Deal legislation. Howard Ball

Howard is an English-language given name originating from Old French Huard (or Houard) from a Germanic source similar to Old High German ''*Hugihard'' "heart-brave", or ''*Hoh-ward'', literally "high defender; chief guardian". It is also probabl ...

called McReynolds "the most strident Court critic of Roosevelt's New Deal programs".

As a confirmed opponent of federal authority aimed toward social ends or economic regulation, McReynolds had the "single-minded passion of a zealot". He was a "firm believer in laissez-faire economic theory", which he said was constitutionally enshrined. After the "Lochner era

The ''Lochner'' era is a period in American legal history from 1897 to 1937 in which the Supreme Court of the United States is said to have made it a common practice "to strike down economic regulations adopted by a State based on the Court's o ...

" ended in 1937the Court's " switch in time that saved nine"McReynolds became a dissenter. Unchanging through his 1941 retirement, his dissents continued to decry the federal government's exercises of power. In ''Steward Machine Co. v. Davis

''Steward Machine Company v. Davis'', 301 U.S. 548 (1937), was a case in which the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the unemployment compensation provisions of the Social Security Act of 1935, which established the Federal Unemployment Tax Act, federal ta ...

'', 301 U.S. 548 (1937), he dissented from a decision upholding the Social Security Act

The Social Security Act of 1935 is a law enacted by the 74th United States Congress and signed into law by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt. The law created the Social Security program as well as insurance against unemployment. The law was pa ...

. He wrote: "I can not find any authority in the Constitution for making the Federal Government the great almoner

An almoner (} ' (alms), via the popular Latin '.

History

Christians have historically been encouraged to donate one-tenth of their income as a tithe to their church and additional offerings as needed for the poor. The first deacons, mentioned ...

of public charity throughout the United States".

McReynolds wrote two early decisions using the Fourteenth Amendment to protect

McReynolds wrote two early decisions using the Fourteenth Amendment to protect civil liberties

Civil liberties are guarantees and freedoms that governments commit not to abridge, either by constitution, legislation, or judicial interpretation, without due process. Though the scope of the term differs between countries, civil liberties may ...

: ''Meyer v. Nebraska

''Meyer v. Nebraska'', 262 U.S. 390 (1923), was a U.S. Supreme Court case that held that a 1919 Nebraska law restricting foreign-language education violated the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution. ...

'', , and ''Pierce v. Society of Sisters

''Pierce v. Society of Sisters'', 268 U.S. 510 (1925), was an early 20th-century United States Supreme Court decision striking down an Oregon statute that required all children to attend public school. The decision significantly expanded coverage ...

'', . ''Meyer'' involved a state law that prohibited the teaching of modern foreign languages in public schools. Meyer, who taught German in a Lutheran school, was convicted under this law. In overturning the conviction on substantive due process

Due process of law is application by state of all legal rules and principles pertaining to the case so all legal rights that are owed to the person are respected. Due process balances the power of law of the land and protects the individual pers ...

grounds, McReynolds wrote that the liberty guaranteed by the Due Process Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment included an individual's right "to contract, to engage in any of the common occupations of life, to acquire useful knowledge, to marry, to establish a home and bring up children, to worship God according to the dictates of his conscience, and generally to enjoy privileges, essential to the orderly pursuit of happiness by free men". These two decisions survived the post-Lochner era.

''Pierce'' involved a challenge to a law forbidding parents to send their children to any but public schools. McReynolds wrote the opinion for a unanimous Court, holding that the Act violated the liberty of parents to direct the education of their children: "the fundamental liberty upon which all governments in this Union repose excludes any general power of the State to standardize its children by forcing them to accept instruction from public teachers only". These decisions were revived long after McReynolds left the bench, to buttress the Court's announcement of a constitutional right to privacy

The right to privacy is an element of various legal traditions that intends to restrain governmental and private actions that threaten the privacy of individuals. Over 150 national constitutions mention the right to privacy. On 10 December 1948 ...

in ''Griswold v. Connecticut

''Griswold v. Connecticut'', 381 U.S. 479 (1965), was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States protects the liberty of married couples to buy and use contraceptives withou ...

'', , and later the constitutional right to abortion

Abortion-rights movements, also referred to as Pro-choice (term), pro-choice movements, advocate for the right to have Abortion law, legal access to induced abortion services including elective abortion. They seek to represent and support wome ...

in ''Roe v. Wade

''Roe v. Wade'', 410 U.S. 113 (1973),. was a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court in which the Court ruled that the Constitution of the United States conferred the right to have an abortion. The decision struck down many federal and s ...

'', .

McReynolds wrote the decision in ''United States v. Miller

''United States v. Miller'', 307 U.S. 174 (1939), was a landmark decision of the Supreme Court of the United States that involved a Second Amendment to the United States Constitution challenge to the National Firearms Act of 1934 (NFA). The cas ...

'', , the only Supreme Court case directly involving the Second Amendment

The second (symbol: s) is the unit of time in the International System of Units (SI), historically defined as of a day – this factor derived from the division of the day first into 24 hours, then to 60 minutes and finally to 60 seconds eac ...

until ''District of Columbia v. Heller

''District of Columbia v. Heller'', 554 U.S. 570 (2008), is a landmark decision of the U.S. Supreme Court ruling that the Second Amendment to the U.S. Constitution protects an individual's right to keep and bear arms, unconnected with service i ...

'' in 2008. In the field of tax law, he wrote for the Court in '' Burnet v. Logan'', 283 U.S. 404 (1931), a significant decision setting out the Court's doctrine regarding "open transactions."

McReynolds also wrote the dissent in the ''Gold Clause Cases

The ''Gold Clause Cases'' were a series of actions brought before the Supreme Court of the United States, in which the court narrowly upheld restrictions on the ownership of gold implemented by the administration of U.S. President Franklin D. Roo ...

'', which required the surrender of all gold coins

A gold coin is a coin that is made mostly or entirely of gold. Most gold coins minted since 1800 are 90–92% gold (22 karat), while most of today's gold bullion coins are pure gold, such as the Britannia, Canadian Maple Leaf, and American Bu ...

, gold bullion

A gold bar, also called gold bullion or gold ingot, is a quantity of refined metallic gold of any shape that is made by a bar producer meeting standard conditions of manufacture, labeling, and record keeping. Larger gold bars that are produced ...

, and gold certificate

Gold certificates were issued by the United States Treasury as a form of representative money from 1865 to 1933. While the United States observed a gold standard, the certificates offered a more convenient way to pay in gold than the use of coi ...

s to the government by May 1, 1933, under Executive Order 6102

Executive Order 6102 is an executive order signed on April 5, 1933, by US President Franklin D. Roosevelt "forbidding the hoarding of gold coin, gold bullion, and gold certificates within the continental United States." The executive order was ...

, issued by President Franklin Roosevelt.

Personality and conflicts

McReynolds was labeled " Scrooge" by journalist Drew Pearson.This is the title of the chapter dedicated to McReynolds in . Chief JusticeWilliam Howard Taft

William Howard Taft (September 15, 1857March 8, 1930) was the 27th president of the United States (1909–1913) and the tenth chief justice of the United States (1921–1930), the only person to have held both offices. Taft was elected pr ...

thought him selfish, prejudiced, and "one who delights in making others uncomfortable ... has a continual grouch, and is always offended because the court is doing something that he regards as undignified." Taft also wrote that McReynolds was the most irresponsible member of the Court, and that " the absence of McReynolds everything went smoothly."

Early on, his temperament affected his performance in the court. For example, he determined that John Clarke, another Wilson appointee, was "too liberal" and refused to speak with him. Clarke decided to resign early from the court, and said that McReynolds's open antipathy was a factor. McReynolds refused to sign the customary joint memorial letter for Clarke, which was always given to departing members. In a letter, Taft commented that " is is a fair sample of McReynolds's personal character and the difficulty of getting along with him."

Taft wrote that although he considered McReynolds an "able man", he found him to be "selfish to the last degree ... fuller of prejudice than any man I have ever known ... one who delights in making others uncomfortable. He has no sense of duty ... really seems to have less of a loyal spirit to the Court than anybody." In 1929 McReynolds asked Taft to announce opinions assigned to him (McReynolds), explaining that "an imperious voice has called me out of town. I don't think my sudden illness will prove fatal, but strange things some time ichappen around Thanksgiving." Duck hunting season had opened and McReynolds was off to Maryland for some shooting. In 1925, he left so suddenly on a similar errand that he had no opportunity to notify the Chief Justice of his departure. Taft was infuriated as two important decisions he wanted to deliver were delayed because McReynolds had not handed in a dissent before leaving.

McReynolds went on tirades about "un-Americans" and "political subversives." Known as a blatant

Taft wrote that although he considered McReynolds an "able man", he found him to be "selfish to the last degree ... fuller of prejudice than any man I have ever known ... one who delights in making others uncomfortable. He has no sense of duty ... really seems to have less of a loyal spirit to the Court than anybody." In 1929 McReynolds asked Taft to announce opinions assigned to him (McReynolds), explaining that "an imperious voice has called me out of town. I don't think my sudden illness will prove fatal, but strange things some time ichappen around Thanksgiving." Duck hunting season had opened and McReynolds was off to Maryland for some shooting. In 1925, he left so suddenly on a similar errand that he had no opportunity to notify the Chief Justice of his departure. Taft was infuriated as two important decisions he wanted to deliver were delayed because McReynolds had not handed in a dissent before leaving.

McReynolds went on tirades about "un-Americans" and "political subversives." Known as a blatant bigot

Discrimination is the act of making unjustified distinctions between people based on the groups, classes, or other categories to which they belong or are perceived to belong. People may be discriminated on the basis of race, gender, age, rel ...

, he would not accept "Jews, drinkers, blacks, women, smokers, married or engaged individuals" as law clerks. ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' "called him 'Puritanical', 'intolerably rude', 'savagely sarcastic', 'incredibly reactionary', and 'anti-Semitic'". McReynolds refused to speak to Louis Brandeis

Louis Dembitz Brandeis (; November 13, 1856 – October 5, 1941) was an American lawyer and associate justice on the Supreme Court of the United States from 1916 to 1939.

Starting in 1890, he helped develop the "right to privacy" concept ...

, the first Jewish member of the Court, for the first three years of Brandeis's tenure. When Brandeis retired in 1939, McReynolds did not sign the customary dedicatory letter sent to justices on their retirement. He habitually left the conference room whenever Brandeis spoke.

When Benjamin Cardozo

Benjamin ( he, ''Bīnyāmīn''; "Son of (the) right") blue letter bible: https://www.blueletterbible.org/lexicon/h3225/kjv/wlc/0-1/ H3225 - yāmîn - Strong's Hebrew Lexicon (kjv) was the last of the two sons of Jacob and Rachel (Jacob's th ...

's appointment was being pressed on President Herbert C. Hoover, McReynolds joined Justices Pierce Butler Pierce or Piers Butler may refer to:

*Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467 – 26 August 1539), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

*Piers Butler, 3rd Viscount Galmoye (1652–1740), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

* P ...

and Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1911 to 1937. He was a staunch conservative and was regarded as a part of the Four ...

in urging the White House not to "afflict the Court with another Jew". When news of Cardozo's appointment was announced, McReynolds is claimed to have said "Huh, it seems that the only way you can get on the Supreme Court these days is to be either the son of a criminal or a Jew, or both." During Cardozo's swearing-in ceremony, McReynolds pointedly read a newspaper. He often held a brief or record in front of his face when Cardozo delivered an opinion from the bench. Likewise, he refused to sign opinions authored by Brandeis.

According to John Frush Knox

John Frush Knox (1907–1997) served as secretary and law clerk to United States Supreme Court Justice James Clark McReynolds from 1936 to 1937. After working at various law firms, he took over his family's mail-order business and then worked ...

, McReynolds's law clerk for the 1936–37 term (following the seven-year clerkship of Maurice Mahoney), and one author of a memoir of McReynolds's service, McReynolds never spoke to Cardozo at all, and several sources report that he did not attend Cardozo's memorial ceremonies held at the Supreme Court. (On the other hand, the report that he did not attend Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judicia ...

's swearing-in—with regard to which he is reported to have exclaimed, "My God, another Jew on the Court!"—was refuted by Supreme Court historian Franz Jantzen, as cited by T.C. Peppers in the '' Richmond Public Interest Law Review''.)

In 1922, Taft proposed that members of the Court accompany him to Philadelphia on a ceremonial occasion, but McReynolds refused, writing: "As you know, I am not always to be found when there is a Hebrew abroad. Therefore, my 'inability' to attend must not surprise you." However, the oft-repeated story that McReynolds refused to sit for the 1924 Court photograph because of his hostility to Brandeis is untrue. McReynolds objected to taking a new photograph when there had been no change in the membership of the court since the 1923 photograph. Alpheus T. Mason __NOTOC__

Alpheus Thomas Mason (September 18, 1899October 31, 1989) was an American legal scholar and biographer. He wrote several biographies of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States, including Louis Brandeis, Harlan F. Stone, ...

misinterpreted this as hostility to Brandeis, but McReynolds sat for numerous photographs for which Brandeis (and later Felix Frankfurter) were present.

Once, when colleague Harlan Fiske Stone

Harlan is a given name and a surname which may refer to:

Surname

*Bob Harlan (born 1936 Robert E. Harlan), American football executive

*Bruce Harlan (1926–1959), American Olympic diver

*Byron B. Harlan (1886–1949), American politician

*Byron G ...

remarked to him of an attorney's brief: "That was the dullest argument I ever heard in my life," McReynolds replied: "The only duller thing I can think of is to hear you read one of your opinions."

McReynolds's rudeness was not confined to colleagues on the Court, or Jews. When Charles Hamilton Houston

Charles Hamilton Houston (September 3, 1895 – April 22, 1950) was a prominent African-American lawyer, Dean of Howard University Law School, and NAACP first special counsel, or Litigation Director. A graduate of Amherst College and Harvard Law ...

, one of the foremost African American lawyers of his day, appeared before the Court to argue in favor of desegregating the University of Missouri Law School

The University of Missouri School of Law (Mizzou Law or MU Law) is the law school of the University of Missouri. It is located on the university's main campus in Columbia, forty minutes from the Missouri State Capitol in Jefferson City. The sc ...

in ''Gaines v. Canada

''Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada'', 305 U.S. 337 (1938), was a Supreme Court of the United States, United States Supreme Court decision holding that U.S. state, states which provided a List of state universities in the United States, school to ...

'', McReynolds turned his chair backward so he could not see Hamilton. McReynolds's long-suffering African-American domestic servants—subject to his racism—gave him the nickname "Pussywillow."

Once, when called before the chairman of the Golf Committee at the Chevy Chase

Cornelius Crane "Chevy" Chase (; born October 8, 1943) is an American comedian, actor and writer. He became a key cast member in the first season of ''Saturday Night Live'', where his recurring ''Weekend Update'' segment became a staple of the ...

club to answer complaints filed against him, McReynolds said:

Justices Pierce Butler Pierce or Piers Butler may refer to:

*Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467 – 26 August 1539), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

*Piers Butler, 3rd Viscount Galmoye (1652–1740), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

* P ...

and Willis Van Devanter

Willis Van Devanter (April 17, 1859 – February 8, 1941) was an American lawyer who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1911 to 1937. He was a staunch conservative and was regarded as a part of the Four ...

transferred from the Chevy Chase club to Burning Tree because McReynolds "got disagreeable even beyond their endurance".

When a woman lawyer appeared in the courtroom, McReynolds reportedly muttered: "I see the female is here again." He often left the bench when a woman lawyer rose to present a case. He found the wearing of wristwatches by men effeminate, and the use of red fingernail polish by women vulgar.

McReynolds forbade smoking in his presence, and is said to have been responsible for the "No Smoking" signs in the Supreme Court Building, inaugurated during his tenure. He announced to any justice who attempted to smoke in conference that "tobacco smoke is personally objectionable to me". Any who tried "were stopped at the threshold".

But McReynolds was reportedly "extremely charitable" to the pages who worked at the Court, and had a great love of children. For example, he gave very generous assistance and adopted 33 children who were victims of the German bombing of London in 1940, and left a sizable fortune to charity. After Oliver Wendell Holmes's wife died, McReynolds wept at her funeral. Holmes wrote in 1926: "Poor McReynolds is, I think, a man of feeling and of more secret kindliness than he would get credit for."

McReynolds often entertained at his apartment, and occasionally passed cigarettes to his guests. He often invited people for brunch on Sunday mornings. According to William O. Douglas

William Orville Douglas (October 16, 1898January 19, 1980) was an American jurist who served as an associate justice of the Supreme Court of the United States, who was known for his strong progressive and civil libertarian views, and is often ci ...

, "On these informal occasions in his own home he was the essence of hospitality and a very delightful companion." Once, when riding to his office on a street car, a drunk got on board and fell out in the aisle. McReynolds picked him up, helped him back to his seat, and sat beside him until they reached the top of Capitol Hill, leaving him only after giving explicit instructions to the conductor. When he was required to preside in court, due to absence of more senior justices, "he was the soul of courtesy, graciously greeting and raptly listening to the arguments by lawyers of both sexes." The public McReynolds was noted for his hospitality. He entertained frequently at the Willard Hotel with guest lists of 150 people, including his fellow justices, and at an annual eggnog party that was one of the social highlights of the Christmas season. Alice Roosevelt

Alice Lee Roosevelt Longworth (February 12, 1884 – February 20, 1980) was an American writer and socialite. She was the eldest child of U.S. president Theodore Roosevelt and his only child with his first wife, Alice Hathaway Lee Roosevelt. Lo ...

, one of many friends, requested the services of his cook, Mrs. Parker, for her wedding breakfast on the occasion of her marriage to Nicholas Longworth.

Retirement

After a substantialhearing loss

Hearing loss is a partial or total inability to Hearing, hear. Hearing loss may be present at birth or acquired at any time afterwards. Hearing loss may occur in one or both ears. In children, hearing problems can affect the ability to Language ...

in 1925, McReynolds strongly intended to resign from the Court, and was dissuaded only by requests by many friends, who called him "one of the few who have courageously stood for the rights of property and of the citizen." McReynolds retired on January 31, 1941, and assumed senior status

Senior status is a form of semi-retirement for United States federal judges. To qualify, a judge in the Federal judiciary of the United States, federal court system must be at least 65 years old, and the sum of the judge's age and years of servi ...

. He lived at the Rochambeau apartment complex in Washington, D.C.

)

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from top left: the Washington Monument and Lincoln Memorial on the National Mall, United States Capitol, Logan Circle, Jefferson Memorial, White House, Adams Morgan, ...

from 1915 until President Roosevelt requisitioned the building in 1935 for his New Deal requirements. McReynolds found a new apartment at 2400 Sixteenth Street.

Death and legacy

McReynolds never married. He died on August 24, 1946, and was buried in the Elkton Cemetery inElkton, Kentucky

Elkton is a home rule-class city in and the county seat of Todd County, Kentucky, United States. The population was 2,062 at the 2010 census.

History

The city was founded by Major John Gray and established by the state assembly in 1820. It is ...

. Elkton residents fondly remembered him, pointing out both his home and office "with great pride and respect".

Knox wrote "in 1946 he cReynoldsdied a very lonely death in a hospital – without a single friend or relative at his bedside. He was buried in Kentucky, but no member of the Court attended his funeral though one employee of the Court traveled to Kentucky for the services." In contrast, as the clerk noted, when McReynolds's aged African-American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an Race and ethnicity in the United States, ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American ...

messenger, Harry Parker, died in 1953, his funeral was attended by five or six justices, including the chief justice. McReynolds's brother, Robert, visited him in the hospital shortly before his death.

In his will, McReynolds wrote, "let there be no service in Washington". The U.S. Marshal for the Supreme Court traveled to Elkton for the funeral. The ''Christian Science Monitor

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι� ...

'' hailed McReynolds in tribute as: '"the last and lone champion on the Supreme Bench battling the steady encroachment of Federal powers on State and individual rights ... standing these later years at the Battle of Thermopylae, Pass of Thermopylae."

McReynolds bequeathed his entire estate to charity. Among these bequests were additional funds to Children's Hospital in Washington, which he had supported for years, adding a new elevator, $10,000 and the residue of his estate. His books and opinions were left to the Library of Congress, and $10,000 and his judicial robe to Vanderbilt University, where he had served for 30 years on the Board of Trustees.

Papers

McReynolds's papers are held at many libraries around the country, mainly at the University of Virginia Law School; Harvard University Law School,Felix Frankfurter

Felix Frankfurter (November 15, 1882 – February 22, 1965) was an Austrian-American jurist who served as an Associate Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States from 1939 until 1962, during which period he was a noted advocate of judicia ...

papers; John Knox papers (1920–80), available at the University of Virginia and Northwestern University; University of Kentucky at Lexington, Kentucky, William Jennings Price (1851–1952) papers; University of Michigan Bentley Historical Library, Frank Murphy papers; Minnesota Historical Society, Pierce Butler Pierce or Piers Butler may refer to:

*Piers Butler, 8th Earl of Ormond (c. 1467 – 26 August 1539), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

*Piers Butler, 3rd Viscount Galmoye (1652–1740), Anglo-Irish nobleman in the Peerage of Ireland

* P ...

papers; Tennessee State Library and Archives, Robert Boyte Crawford Howell papers; University of Virginia, Homer Stille Cummings papers.

See also

* List of justices of the Supreme Court of the United States * List of law clerks of the Supreme Court of the United States (Seat 3) * List of United States Supreme Court justices by time in office * List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Hughes Court, United States Supreme Court cases during the Hughes Court * List of United States Supreme Court cases by the Taft Court, United States Supreme Court cases during the Taft Court * List of United States Supreme Court cases by the White Court, United States Supreme Court cases during the White CourtFurther reading

Scholarly books

* * Note, the designation of McReynolds as "Chief" Justice in the title is an error. * *Law journal articles

* *James Clark McReynolds (Associate Justice, 1914-1941) might be the single most personally unpopular Supreme Court Justice in history... But was he so anti-Semitic that there is no group photograph for 1924 because he refused to sit next to Justice Louis D. Brandeis, as the seating arrangement dictated? Although this story is frequently cited as evidence of just how obnoxious he could be, it is not true.* See also thi

alternative link to the full paper

[Under section entitled, "Justice James Clark McReynolds: The "Ebenezer Scrooge" of the Court", citation numbers remaining, citations omitted] "McReynolds was unquestionably the most unpleasant individual to sit on the Supreme Court bench. The list of adjectives that could be used to describe McReynolds includes racist, anti-Semite, misogynist, imperious, lazy, miserly and curmudgeon. Those who regularly interacted with McReynolds—his fellow justices, his long-time messenger, his domestic staff, his law clerks, and even members of his country club—were targets of his snobbery and vitriol. Chief Justice William Howard Taft himself once described McReynolds as a 'continual grouch' and 'selfish to the last degree... fuller of prejudice than any man I have ever known... one who delights in making others uncomfortable. He has no sense of duty... [and] really seems to have less of a loyal spirit to the Court than anybody.'[35] / Some criticism of McReynolds, however, seems remarkably petty. Biographers and journalists sniped at McReynolds for being a mediocre golfer whose slow play held up foursomes behind him.[36] He hated tobacco and would ask smokers to extinguish their cigarettes and cigars, was a dangerous driver, and may have had an affair with a married woman.[37] Even his physical appearance was fair game: 'McReynolds is a bachelor, tall, slender and has a face with such a Satanic look that in it there is a certain charm.'[38] / Like many controversial figures, however, the stories about McReynolds' nasty personality have taken on a life of their own and the line between fact and fiction has been blurred. In a recent article, Supreme Court historian Franz Jantzen debunks two popular rumors related to McReynolds' antisemitism: (1) that McReynolds refused to have his official portrait taken because he did not want to sit next to Louis Brandeis (the first Jewish justice), and (2) that McReynolds refused to attend the swearing-in ceremony of Felix Frankfurter (the third Jewish justice).[39] While conceding that McReynolds had racist and religious prejudices, Jantzen ends with an important warning: 'We can only truly take the measure of the man by using those things that he actually said and did...not by using myth and innuendo.'[40] / Nor can you take the full measure of the man without discussing all of his attributes – positive and negative. In a 1939 Time article, the magazine raised a familiar set of charges against the Justice: he was a man "intolerably rude, antiSemitic [sic], savagely sarcastic, incredibly reactionary, Puritanical, prejudiced."[41] The same article, however, observed that the McReynolds 'legend' (an important choice of words) 'had little to say about his tenderness to his narrow circle of friends, his unfailing generosity, his clear legal perception, his unerring eye and ear for the false, the unessential.'"

Dictionaries and Encyclopedias

* * * "McReynolds, James Clark," Dictionary of American Biography. * "McReynolds, James Clark," American National Biography. *Other works

Bibliography on James Clark McReynolds at 6th Circuit

United States Court of Appeals.

Notes

References

Bibliography

* * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * * *External links

Biography, James Clark McReynolds at Federal Judicial Center

* Supreme Court Historical Society

James C. McReynolds.

, - {{DEFAULTSORT:McReynolds, James Clark 1862 births 1946 deaths 20th-century American judges 20th-century American politicians American Disciples of Christ American legal scholars American members of the Churches of Christ American people of Scotch-Irish descent Kentucky Democrats People from Elkton, Kentucky Tennessee Democrats Tennessee lawyers United States Assistant Attorneys General United States Attorneys General United States federal judges appointed by Woodrow Wilson Justices of the Supreme Court of the United States Vanderbilt University Law School faculty University of Virginia School of Law alumni Woodrow Wilson administration cabinet members Cravath, Swaine & Moore people Old Right (United States) Antisemitism in the United States