Jain meditation on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Jain meditation (''dhyāna'') has been the central practice of spirituality in

Jain meditation (''dhyāna'') has been the central practice of spirituality in

Shukla Dhyana.

' According to Sagarmal Jain, it aims to reach and remain in a state of "pure-self awareness or knowership."Jain, Sagarmal, The Historical development of the Jaina yoga system and the impacts of other Yoga systems on Jaina Yoga, in "Christopher Key Chapple (editor), Yoga in Jainism" chapter 1. Meditation is also seen as realizing the self, taking the soul to complete freedom, beyond any craving, aversion and/or attachment. The practitioner strives to be just a knower-seer (''Gyata-Drashta''). Jain meditation can be broadly categorized to the auspicious (''Dharmya Dhyana'' and ''Shukla Dhyana'') and inauspicious (''Artta'' and ''Raudra Dhyana''). The 20th century saw the development and spread of new modernist forms of Jain ''Dhyana,'' mainly by

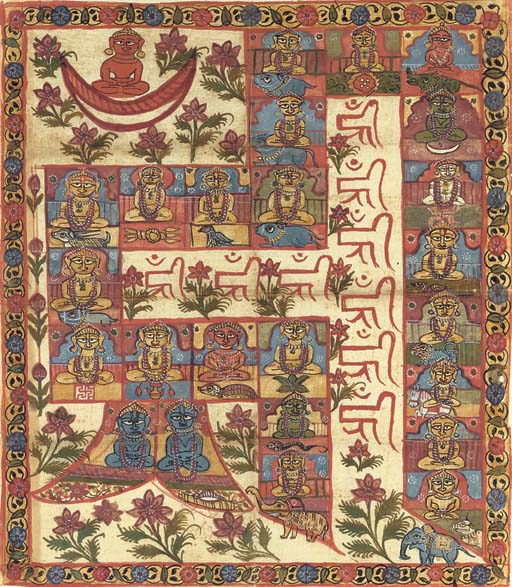

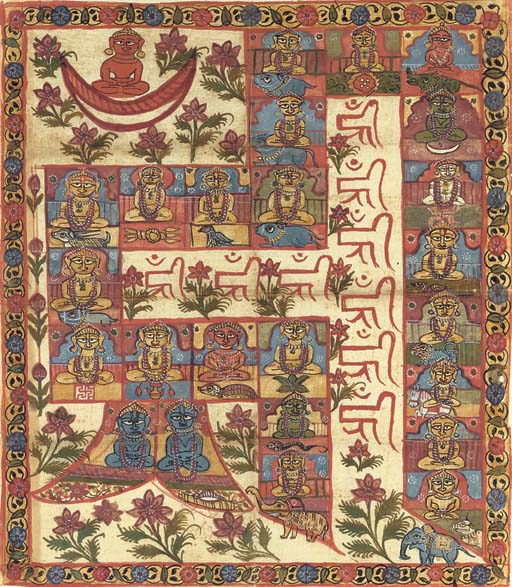

Jains believe all twenty-four Tirthankaras (such as

Jains believe all twenty-four Tirthankaras (such as

Arta-Dhyana

'' "a mental condition of suffering, agony and anguish." Usually caused by thinking about an object of desire or a painful ailment. #

Raudra-Dhyana

'' associated with cruelty, aggressive and possessive urges. #

Dharma-Dhyana

'' "virtuous" or "customary", refers to knowledge of the soul, the non-soul and the universe. Over time this became associated with discriminating knowledge (''bheda-vijñāna'') of the

Sukla-Dhyana

' (pure or white), divided into (1) Multiple contemplation, (''pṛthaktva-vitarka-savicāra''); (2) Unitary contemplation, (''aikatva-vitarka-nirvicāra''); (3) Subtle infallible physical activity (''sūkṣma-kriyā-pratipāti''); and (4) Irreversible stillness of the soul (''vyuparata-kriyā-anivarti''). The first two are said to require knowledge of the lost Jain scriptures known as

This period sees tantric influences on Jain meditation, which can be gleaned in the Jñānārṇava of Śubhacandra (11thc. CE), and the

This period sees tantric influences on Jain meditation, which can be gleaned in the Jñānārṇava of Śubhacandra (11thc. CE), and the

The growth and popularity of mainstream

The growth and popularity of mainstream

Despite the innovations, the

Despite the innovations, the

The name ''Sāmāyika'', the term for Jain meditation, is derived from the term ''samaya'' "time" in

The name ''Sāmāyika'', the term for Jain meditation, is derived from the term ''samaya'' "time" in

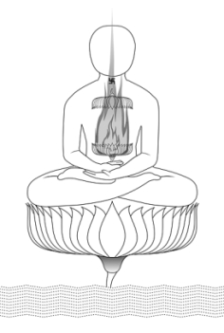

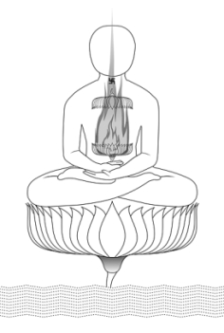

In ''pindāstha-dhyāna'' one imagines oneself sitting all alone in the middle of a vast

In ''pindāstha-dhyāna'' one imagines oneself sitting all alone in the middle of a vast

Jain meditation (''dhyāna'') has been the central practice of spirituality in

Jain meditation (''dhyāna'') has been the central practice of spirituality in Jainism

Jainism ( ), also known as Jain Dharma, is an Indian religion. Jainism traces its spiritual ideas and history through the succession of twenty-four tirthankaras (supreme preachers of ''Dharma''), with the first in the current time cycle being ...

along with the Three Jewels

In Buddhism, refuge or taking refuge refers to a religious practice, which often includes a prayer or recitation performed at the beginning of the day or of a practice session. Since the period of Early Buddhism until present time, all Theravad ...

. Jainism holds that emancipation can only be achieved through meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

or Shukla Dhyana.

' According to Sagarmal Jain, it aims to reach and remain in a state of "pure-self awareness or knowership."Jain, Sagarmal, The Historical development of the Jaina yoga system and the impacts of other Yoga systems on Jaina Yoga, in "Christopher Key Chapple (editor), Yoga in Jainism" chapter 1. Meditation is also seen as realizing the self, taking the soul to complete freedom, beyond any craving, aversion and/or attachment. The practitioner strives to be just a knower-seer (''Gyata-Drashta''). Jain meditation can be broadly categorized to the auspicious (''Dharmya Dhyana'' and ''Shukla Dhyana'') and inauspicious (''Artta'' and ''Raudra Dhyana''). The 20th century saw the development and spread of new modernist forms of Jain ''Dhyana,'' mainly by

monk

A monk (, from el, μοναχός, ''monachos'', "single, solitary" via Latin ) is a person who practices religious asceticism by monastic living, either alone or with any number of other monks. A monk may be a person who decides to dedica ...

s and laypersons of Śvētāmbara

The Śvētāmbara (; ''śvētapaṭa''; also spelled ''Shwethambara'', ''Svetambar'', ''Shvetambara'' or ''Swetambar'') is one of the two main branches of Jainism, the other being the ''Digambara''. Śvētāmbara means "white-clad", and refers ...

Jainism.

Jain meditation is also referred to as Sāmāyika

''Sāmāyika'' is the vow of periodic concentration observed by the Jains. It is one of the essential duties prescribed for both the '' Śrāvaka'' (householders) and ascetics. The preposition ''sam'' means one state of being. To become one is ...

which is done for 48 minutes in peace and silence. A form of this which includes a strong component of scripture study ( Svādhyāya) is mainly promoted by the Digambara

''Digambara'' (; "sky-clad") is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being '' Śvētāmbara'' (white-clad). The Sanskrit word ''Digambara'' means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing n ...

tradition of Jainism. The word ''Sāmāyika'' means "being in the moment of continuous real-time". This act of being conscious of the continual renewal of the universe in general and one's own renewal of the individual living being (''Jiva'') in particular is the critical first step in the journey towards identification with one's true nature, called the ''Atman Atman or Ātman may refer to:

Film

* ''Ātman'' (1975 film), a Japanese experimental short film directed by Toshio Matsumoto

* ''Atman'' (1997 film), a documentary film directed by Pirjo Honkasalo

People

* Pavel Atman (born 1987), Russian hand ...

''. It is also a method by which one can develop an attitude of harmony and respect towards other humans, animals and Nature.

Jains believe meditation has been a core spiritual practice since the teaching of the Tirthankara

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English language, English: literally a 'Ford (crossing), ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the ''Dharma (Jainism), dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the ...

, Rishabha

Rishabhanatha, also ( sa, ऋषभदेव), Rishabhadeva, or Ikshvaku is the first (Supreme preacher) of Jainism and establisher of Ikshvaku dynasty. He was the first of twenty-four teachers in the present half-cycle of time in Jain c ...

. All the twenty-four Tirthankaras practiced deep meditation and attained enlightenment. They are all shown in meditative postures in images and idols. Mahavira

Mahavira (Sanskrit: महावीर) also known as Vardhaman, was the 24th ''tirthankara'' (supreme preacher) of Jainism. He was the spiritual successor of the 23rd ''tirthankara'' Parshvanatha. Mahavira was born in the early part of the 6t ...

practiced deep meditation for twelve years and attained enlightenment

Enlightenment or enlighten may refer to:

Age of Enlightenment

* Age of Enlightenment, period in Western intellectual history from the late 17th to late 18th century, centered in France but also encompassing (alphabetically by country or culture): ...

. The Acaranga Sutra dating to 500 BCE, addresses the meditation system of Jainism in detail.Ahimsa – ''The Science Of Peace'' by Surendra Bothra 1987 Acharya

In Indian religions and society, an ''acharya'' (Sanskrit: आचार्य, IAST: ; Pali: ''ācariya'') is a preceptor and expert instructor in matters such as religion, or any other subject. An acharya is a highly learned person with a ti ...

Bhadrabahu of the 4th century BCE practiced deep ''Mahaprana'' meditation for twelve years. Kundakunda

Kundakunda was a Digambara Jain monk and philosopher, who likely lived in the 2nd CE century CE or later.

His date of birth is māgha māsa, śukla pakṣa, pañcamī tithi, on the day of Vasant Panchami.

He authored many Jain texts such as: ...

of 1st century BCE, opened new dimensions of meditation in Jain tradition through his books such as '' Samayasāra'' and ''Pravachansar''. The 8th century Jain philosopher Haribhadra

Aacharya Haribhadra Suri was a Svetambara mendicant Jain leader, philosopher , doxographer, and author. There are multiple contradictory dates assigned to his birth. According to tradition, he lived c. 459–529 CE. However, in 1919, a Jain ...

also contributed to the development of Jain yoga through his Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya, which compares and analyzes various systems of yoga, including Hindu, Buddhist and Jain systems.

There are various common postures for Jain meditation, including Padmasana, Ardh-Padmasana, Vajrasana Vajrasana (Sanskrit for "diamond seat" or "diamond throne") may refer to:

* The Vajrasana, Bodh Gaya, India where Gautama Buddha achieved enlightenment

* Vajrasana (yoga), an asana in yoga

{{Disambig ...

, Sukhasana

Lotus position or Padmasana ( sa, पद्मासन, translit=padmāsana) is a cross-legged sitting meditation pose from ancient India, in which each foot is placed on the opposite thigh. It is an ancient asana in yoga, predating hatha ...

, standing, and lying down. The 24 Tirthankaras are always seen in one of these two postures in the Kayotsarga

Kayotsarga ( , pka, काउस्सग्ग ) is a yogic posture which is an important part of the Jain meditation. It literally means "dismissing the body". A tirthankara is represented either seated in yoga posture or standing in the kay ...

(standing) or Padmasana/''Paryankasana'' (Lotus).

Ancient history

Sagarmal Jain divides the history of Jaina yoga and meditation into five stages, 1. pre-canonical (before sixth century BCE), 2. canonical age (fifth century BCE to fifth century CE), 3. post-canonical (sixth century CE to twelfth century CE), age oftantra

Tantra (; sa, तन्त्र, lit=loom, weave, warp) are the esoteric traditions of Hinduism and Buddhism that developed on the Indian subcontinent from the middle of the 1st millennium CE onwards. The term ''tantra'', in the Indian ...

and rituals (thirteenth to nineteenth century CE), modern age (20th century on). The main change in the canonical era was that Jain meditation became influenced by Hindu Yogic traditions. Meditation in early Jain literature is a form of austerity and ascetic practice in Jainism, while in the late medieval era the practice adopted ideas from other Indian traditions. According to Paul Dundas, this lack of meditative practices in early Jain texts may be because substantial portions of ancient Jain texts were lost.

Pre-canonical

Jains believe all twenty-four Tirthankaras (such as

Jains believe all twenty-four Tirthankaras (such as Rishabhanatha

Rishabhanatha, also ( sa, ऋषभदेव), Rishabhadeva, or Ikshvaku is the first (Supreme preacher) of Jainism and establisher of Ikshvaku dynasty. He was the first of twenty-four teachers in the present half-cycle of time in Jain c ...

) practiced deep meditation, some for years, some for months and attained enlightenment. All the statues and pictures of Tirthankaras primarily show them in meditative postures. Jain tradition believes that meditation derives from Rishabhanatha

Rishabhanatha, also ( sa, ऋषभदेव), Rishabhadeva, or Ikshvaku is the first (Supreme preacher) of Jainism and establisher of Ikshvaku dynasty. He was the first of twenty-four teachers in the present half-cycle of time in Jain c ...

, the first tirthankara

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English language, English: literally a 'Ford (crossing), ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the ''Dharma (Jainism), dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the ...

. Some scholars have pointed to evidence from Mohenjodaro

Mohenjo-daro (; sd, موئن جو دڙو'', ''meaning 'Mound of the Dead Men';Harappa

Harappa (; Urdu/ pnb, ) is an archaeological site in Punjab, Pakistan, about west of Sahiwal. The Bronze Age Harappan civilisation, now more often called the Indus Valley Civilisation, is named after the site, which takes its name from a mode ...

(such as the pashupati seal) as proof that a pre vedic sramanic meditation tradition is very old in ancient India. However, Sagarmal Jain states that it is very difficult to extract the pre-canonical method of Jain meditation from the earliest sources.

The earliest mention of yogic practices appear in early Jain canonical texts like the Acaranga, Sutrakritanga and Rsibhasita. The Acaranga for example, mentions Trāṭaka (fixed gaze) meditation, Preksha meditation (self-awareness) and Kayotsarga

Kayotsarga ( , pka, काउस्सग्ग ) is a yogic posture which is an important part of the Jain meditation. It literally means "dismissing the body". A tirthankara is represented either seated in yoga posture or standing in the kay ...

(''‘kāyaṃ vosajjamaṇgāre’'', giving up the body). The Acaranga also mentions the tapas

A tapa () is an appetizer or snack in Spanish cuisine. Tapas can be combined to make a full meal, and can be cold (such as mixed olives and cheese) or hot (such as ''chopitos'', which are battered, fried baby squid, or patatas bravas). In some ...

practice of standing in the heat of the sun (ātāpanā).

The Acaranga sutra, one of the oldest Jain texts, describes the solitary ascetic

Asceticism (; from the el, ἄσκησις, áskesis, exercise', 'training) is a lifestyle characterized by abstinence from sensual pleasures, often for the purpose of pursuing spiritual goals. Ascetics may withdraw from the world for their p ...

meditation of Mahavira

Mahavira (Sanskrit: महावीर) also known as Vardhaman, was the 24th ''tirthankara'' (supreme preacher) of Jainism. He was the spiritual successor of the 23rd ''tirthankara'' Parshvanatha. Mahavira was born in the early part of the 6t ...

before attaining Kevala Jnana as follows:Giving up the company of all householders whomsoever, he meditated. Asked, he gave no answer; he went, and did not transgress the right path. (AS 312) In these places was the wise Sramana for thirteen long years; he meditated day and night, exerting himself, undisturbed, strenuously. (AS 333) And Mahavira meditated (persevering) in some posture, without the smallest motion; he meditated in mental concentration on (the things) above, below, beside, free from desires. He meditated free from sin and desire, not attached to sounds or colours; though still an erring mortal (khadmastha), he wandered about, and never acted carelessly.(AS 374-375)After more than twelve years of austerities and meditation, the AS states that Mahavira entered the state of Kevala Jnana while doing shukla dhayana, the highest form of meditation:

The Venerable Ascetic Mahavira passed twelve years in this way of life; during the thirteenth year in the second month of summer, in the fourth fortnight, the light (fortnight) of Vaisakha, on its tenth day called Suvrata, in the Muhurta called Vigaya, while the moon was in conjunction with the asterism Uttaraphalguni, when the shadow had turned towards the east, and the first wake was over, outside of the town Grimbhikagrama, on the northern bank of the river Rigupalika, in the field of the householder Samaga, in a north-eastern direction from an old temple, not far from a Sal tree, in aAccording to Samani Pratibha Pragya, early Jain texts like the ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' and the ''Āvaśyaka-sūtra'' are also important sources for early Jain meditation. The ''squatting position Squatting is a versatile posture where the weight of the body is on the feet but the knees and hips are bent. In contrast, sitting involves taking the weight of the body, at least in part, on the buttocks against the ground or a horizontal object ...with joined heels exposing himself to the heat of the sun, with the knees high and the head low, in deep meditation, in the midst of abstract meditation, he reached Nirvana, the complete and full, the unobstructed, unimpeded, infinite and supreme best knowledge and intuition, called Kevala.

Uttarādhyayana

Uttaradhyayana or Uttaradhyayana Sutra is one of the most important sacred books of the Svetambara Jains. It consists of 36 chapters, each of which deals with aspects of Jain doctrine and discipline. It is believed by some to contain the actu ...

-sūtra'' "offers a systematic presentation of four types of meditative practices such as: meditation (dhyāna)

''Dhyana'' () in Hinduism means contemplation and meditation. ''Dhyana'' is taken up in Yoga practices, and is a means to ''samadhi'' and self-knowledge.

The various concepts of ''dhyana'' and its practice originated in the Sramanic movemen ...

, abandonment of the body (kāyotsarga), contemplation (anuprekṣā), and reflection (bhāvanā)." Pragya argues that "we can conclude that Mahāvīra’s method of meditation consisted of perception and concentration in isolated places, concentration that sought to be unaffected by physical surroundings as well as emotions." Pragya also notes that fasting was an important practice done alongside meditation. The intense meditation described in these texts "is an activity that leads to a state of motionlessness, which is a state of inactivity of body, speech and mind, essential for eliminating karma." The ''Uttarādhyayana-sūtra'' also describes the practice of contemplation ( anuprekṣā).

Another meditation described in the Āvaśyaka-sūtra is meditation on the tīrthaṅkaras

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English: literally a 'ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the ''dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the founder of a '' tirtha'', which is a fordable passag ...

.

Canonical

In this era, the Jain canon was recorded andJain philosophy

Jain philosophy refers to the ancient Indian philosophical system found in Jainism. One of the main features of Jain philosophy is its dualistic metaphysics, which holds that there are two distinct categories of existence, the living, conscio ...

systematized. It is clear that Jain meditation and samadhi

''Samadhi'' (Pali and sa, समाधि), in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ashtanga Yoga ...

continued to evolve and to be practiced after the death of Mahavira

Mahavira (Sanskrit: महावीर) also known as Vardhaman, was the 24th ''tirthankara'' (supreme preacher) of Jainism. He was the spiritual successor of the 23rd ''tirthankara'' Parshvanatha. Mahavira was born in the early part of the 6t ...

by figures such as Acharya Bhadrabahu and Chandragupta Maurya

Chandragupta Maurya (350-295 BCE) was a ruler in Ancient India who expanded a geographically-extensive kingdom based in Magadha and founded the Maurya dynasty. He reigned from 320 BCE to 298 BCE. The Maurya kingdom expanded to become an emp ...

, the founder of Maurya Empire who became a Jain monk in old age and a student of Bhadrabahu. It describes Mahavira as practicing intense austerities, fasts (most commonly three days long, as extreme as six months of fasting) and meditations. In one instance he practiced standing meditation for sixteen days and nights. He did this by facing each of the four directions for a period of time, and then turning to face the intermediate directions as well as above and below.

This period also sees the elucidation of the practice of contemplation ( anuprekṣā) by Kundakunda's ''Vārassa-aṇuvekkhā'' or “Twelve Contemplations” (c. 1st century BCE to 1st century CE). These twelve forms of reflection (''bhāvanā

''Bhāvanā'' ( Pali;Rhys Davids & Stede (1921-25), p. 503, entry for "Bhāvanā," retrieved 9 December 2008 from "U. Chicago" a Sanskrit: भावना, also ''bhāvanā''Monier-Williams (1899), p. 755, see "Bhāvana" and "Bhāvanā", retri ...

'') aid in the stopping of the influx of karma

Karma (; sa, कर्म}, ; pi, kamma, italic=yes) in Sanskrit means an action, work, or deed, and its effect or consequences. In Indian religions, the term more specifically refers to a principle of cause and effect, often descriptively ...

s that extend transmigration. These twelve reflections are:

#''anitya bhāvanā'' – the transitoriness of the world;

#''aśaraņa bhāvanā'' – the helplessness of the soul.

#''saṃsāra'' – the pain and suffering implied in transmigration;

#''aikatva bhāvanā'' – the inability of another to share one’s suffering and sorrow;

#''anyatva bhāvanā'' – the distinctiveness between the body and the soul;

#''aśuci bhāvanā'' – the filthiness of the body;

#āsrava bhāvanā – influx of karmic matter;

#saṃvara bhāvanā – stoppage of karmic matter;

#nirjarā bhāvanā – gradual shedding of karmic matter;

#''loka bhāvanā'' – the form and divisions of the universe and the nature of the conditions prevailing in the different regions – heavens, hells, and the like;

#bodhidurlabha bhāvanā – the extreme difficulty in obtaining human birth and, subsequently, in attaining true faith; and

#dharma bhāvanā – the truth promulgated by Lord Jina.

In his ''Niyamasara'', Acarya Kundakunda

Kundakunda was a Digambara Jain monk and philosopher, who likely lived in the 2nd CE century CE or later.

His date of birth is māgha māsa, śukla pakṣa, pañcamī tithi, on the day of Vasant Panchami.

He authored many Jain texts such as: ...

, also describes ''yoga bhakti''—devotion to the path to liberation—as the highest form of devotion.

The Sthananga Sutra (c. 2nd century BCE) gives a summary of four main types of meditation (dhyana) or concentrated thought. The first two are mental or psychological states in which a person may become fully immersed and are causes of bondage. The other two are pure states of meditation and conduct, which are causes of emancipation. They are:

# Arta-Dhyana

'' "a mental condition of suffering, agony and anguish." Usually caused by thinking about an object of desire or a painful ailment. #

Raudra-Dhyana

'' associated with cruelty, aggressive and possessive urges. #

Dharma-Dhyana

'' "virtuous" or "customary", refers to knowledge of the soul, the non-soul and the universe. Over time this became associated with discriminating knowledge (''bheda-vijñāna'') of the

tattvas

According to various Indian schools of philosophy, ''tattvas'' () are the elements or aspects of reality that constitute human experience. In some traditions, they are conceived as an aspect of deity. Although the number of ''tattvas'' varies ...

(truths or fundamental principles).

# Sukla-Dhyana

' (pure or white), divided into (1) Multiple contemplation, (''pṛthaktva-vitarka-savicāra''); (2) Unitary contemplation, (''aikatva-vitarka-nirvicāra''); (3) Subtle infallible physical activity (''sūkṣma-kriyā-pratipāti''); and (4) Irreversible stillness of the soul (''vyuparata-kriyā-anivarti''). The first two are said to require knowledge of the lost Jain scriptures known as

purvas

The Fourteen Purva translated as ancient or prior knowledge, are a large body of Jain scriptures that was preached by all Tirthankaras (omniscient teachers) of Jainism encompassing the entire gamut of knowledge available in this universe. The pers ...

and thus it is considered by some Jains that pure meditation was no longer possible. The other two forms are said in the Tattvartha sutra to be only accessible to Kevalins (enlightened ones).

This broad definition of the term dhyana means that it signifies any state of deep concentration, with good or bad results. Later texts like Umaswati

Umaswati, also spelled as Umasvati and known as Umaswami, was an Indian scholar, possibly between 2nd-century and 5th-century CE, known for his foundational writings on Jainism. He authored the Jain text ''Tattvartha Sutra'' (literally '"All Tha ...

's ''Tattvārthasūtra'' and Jinabhadra's ''Dhyana-Sataka'' (sixth century) also discusses these four dhyanas. This system seems to be uniquely Jain.

During this era, a key text was the ''Tattvarthasutra'' by Acharya Umāsvāti which codified Jain doctrine. According to the ''Tattvarthasutra

''Tattvārthasūtra'', meaning "On the Nature nowiki/>''artha''">artha.html" ;"title="nowiki/>''artha">nowiki/>''artha''of Reality 'tattva'' (also known as ''Tattvarth-adhigama-sutra'' or ''Moksha-shastra'') is an ancient Jain text writte ...

,'' yoga is the sum of all the activities of mind, speech and body. Umāsvāti (fl. sometime between the 2nd and 5th-century CE) calls yoga the cause of "asrava" or karmic influxTattvarthasutra .2/ref> as well as one of the essentials—'' samyak caritra''—in the path to liberation. Umāsvāti prescribed a threefold path of yoga: right conduct/austerity, right knowledge, right faith. Umāsvāti also defined a series of fourteen stages of spiritual development ( guṇasthāna), into which he embedded the four fold description of dhyana. These stages culminate in the pure activities of body, speech, and mind (''sayogi-kevala''), and the "cessation of all activity" ('' ayogi-kevala''). Umāsvāti also defined meditation in a new way (as ''‘ekāgra-cintā’''): “Concentration of thought on a single object by a person with good bone-joints is meditation which lasts an intra-hour (''ā-muhūrta'')”Other important figures are Jinabhadra, and Pujyapada Devanandi (wrote the commentary ''

Sarvārthasiddhi

''Sarvārthasiddhi'' is a famous Jain text authored by '' Ācārya Pujyapada''. It is the oldest extan commentary on ''Ācārya Umaswami's Tattvārthasūtra'' (another famous Jain text). Traditionally though, the oldest commentary on the Tatt ...

''). Sagarmal Jain notes that during the canonical age of Jaina meditation, one finds strong analogues with the 8 limbs of Patanjali Yoga, including the yamas

The Yamas ( sa, यम, translit=Yama), and their complement, the Niyamas, represent a series of "right living" or ethical rules within Yoga philosophy. It means "reining in" or "control". These are restraints for proper conduct as given in the ...

and niyama

The Niyamas ( sa, नियम, translit=Niyama) are positive duties or observances. In Indian traditions, particularly Yoga, niyamas and their complement, Yamas, are recommended activities and habits for healthy living, spiritual enlightenment ...

s, through often under different names. Sagarmal also notes that during this period the Yoga systems of Jainism, Buddhism and Patanjali Yoga had many similarities.

In spite of this literature, Dundas claims that Jainism never “fully developed a culture of true meditative contemplation,” he further states that later Jaina writers discussed meditation more out of “theoretical interest.”

Post-canonical

This period saw new texts specifically on Jain meditation and further Hindu influences on Jain yoga. Ācārya Haribhadra in the 8th century wrote the meditation compendium called ''Yogadṛṣṭisamuccya'' which discusses systems of Jain yoga, Patanjali Yoga and Buddhist yoga and develops his own unique system that are somewhat similar to these. Ācārya Haribhadra assimilated many elements from Patañjali’s Yoga-sūtra into his new Jain yoga (which also has eight parts) and composed four texts on this topic, ''Yoga-bindu'', ''Yogadṛṣṭisamuccaya, Yoga-śataka'' and ''Yoga-viṅśikā''.Johannes Bronkhorst

Johannes Bronkhorst (born 17 July 1946, Schiedam) is a Dutch Orientalist and Indologist, specializing in Buddhist studies and early Buddhism. He is emeritus professor at the University of Lausanne.

Life

After studying Mathematics, Physics ...

considers Haribhadra's contributions a "far more drastic departure from the scriptures." He worked with a different definition of yoga than previous Jains, defining yoga as "that which connects to liberation" and his works allowed Jainism to compete with other religious systems of yoga.

The first five stages of Haribhadra's yoga system are preparatory and include posture and so on. The sixth stage is kāntā leasing

A lease is a contractual arrangement calling for the user (referred to as the ''lessee'') to pay the owner (referred to as the ''lessor'') for the use of an asset. Property, buildings and vehicles are common assets that are leased. Industrial ...

and is similar to Patañjali's " Dhāraṇā." It is defined as "a higher concentration for the sake of compassion toward others. Pleasure is never found in externals and a beneficial reflection arises. In this state, due to the efficacy of dharma, one’s conduct becomes purified. One is beloved among beings and single-mindedly devoted to dharma. (YSD, 163) With mind always fixed on scriptural dharma." The seventh stage is radiance (prabhā), a state of calmness, purification and happiness as well as "the discipline of conquering amorous passion, the emergence of strong discrimination, and the power of constant serenity." The final stage of meditation in this system is 'the highest' (parā), a "state of Samadhi

''Samadhi'' (Pali and sa, समाधि), in Buddhism, Hinduism, Jainism, Sikhism and yogic schools, is a state of meditative consciousness. In Buddhism, it is the last of the eight elements of the Noble Eightfold Path. In the Ashtanga Yoga ...

in which one becomes free from all attachments and attains liberation." Haribhadra sees this as being in "the category of “ayoga” (motionlessness), a state which we can compare with the state just prior to liberation."

Acarya Haribhadra

Aacharya Haribhadra Suri was a Svetambara mendicant Jain leader, philosopher , doxographer, and author. There are multiple contradictory dates assigned to his birth. According to tradition, he lived c. 459–529 CE. However, in 1919, a Jain ...

(as well as the later thinker Hemacandra

Hemachandra was a 12th century () Indian Jain saint, scholar, poet, mathematician, philosopher, yogi, grammarian, law theorist, historian, lexicographer, rhetorician, logician, and prosodist. Noted as a prodigy by his contemporaries, he ...

) also mentions the five major vows of ascetics and 12 minor vows of laity under yoga. This has led certain Indologist

Indology, also known as South Asian studies, is the academic study of the history and cultures, languages, and literature of the Indian subcontinent, and as such is a subset of Asian studies.

The term ''Indology'' (in German, ''Indologie'') is of ...

s like Prof. Robert J. Zydenbos

Robert J. Zydenbos (born 1957) is a Dutch-Canadian scholar who has doctorate degrees in Indian philosophy and Dravidian studies. He also has a doctorate of literature from the University of Utrecht in the Netherlands. Zydenbos also studied Indi ...

to call Jainism, essentially, a system of yogic thinking that grew into a full-fledged religion. The five yamas or the constraints of the ''Yoga Sutras of Patanjali

The ''Yoga Sutras of Patañjali'' is a collection of Sanskrit sutras (aphorisms) on the theory and practice of yoga – 195 sutras (according to Vyasa, Vyāsa and Krishnamacharya) and 196 sutras (according to others, including BKS Iyengar). ...

'' bear a resemblance to the five major vows of Jainism, indicating a history of strong cross-fertilization between these traditions.

Later works also provide their own definitions of meditation. The ''Sarvārthasiddhi'' of Akalanka

Akalanka (also known as ''Akalank Deva'' and ''Bhatta Akalanka'') was a Jain logician whose Sanskrit-language works are seen as landmarks in Indian logic. He lived from 720 to 780 A.D. and belonged to the Digambara sect of Jainism. His work ''As ...

(9 th c. CE) states "only the knowledge that shines like an unflickering flame is meditation." According to Samani Pratibha Pragya, the Tattvānuśāsana of Ramasena (10th c. CE) states that this knowledge is "many-pointed concentration (''vyagra'') and meditation is one-pointed concentration (''ekāgra'')."

Tantric

This period sees tantric influences on Jain meditation, which can be gleaned in the Jñānārṇava of Śubhacandra (11thc. CE), and the

This period sees tantric influences on Jain meditation, which can be gleaned in the Jñānārṇava of Śubhacandra (11thc. CE), and the Yogaśāstra

''Yogaśāstra'' (''lit.'' "Yoga treatise") is a 12th-century Sanskrit text by Hemachandra on Svetambara Jainism. It is a treatise on the "rules of conduct for laymen and ascetics", wherein "yoga" means "ratna-traya" (three jewels), i.e. right ...

of Hemacandra

Hemachandra was a 12th century () Indian Jain saint, scholar, poet, mathematician, philosopher, yogi, grammarian, law theorist, historian, lexicographer, rhetorician, logician, and prosodist. Noted as a prodigy by his contemporaries, he ...

(12th c. CE). Śubhacandra offered a new model of four meditations:

# Meditation on the corporeal body (piṇḍstha), which also includes five concentrations (dhāraṇā): on the earth element (pārthivī), the fire element (āgneyī), the air element (śvasanā/ mārutī), the water element (vāruṇī) and the fifth related to the non-material self (tattvrūpavatī).

# Meditation on mantric syllables (padastha);

# Meditation on the forms of the arhat (rūpastha);

# Meditation on the pure formless self (rūpātīta).

Śubhacandra also discusses breath control and withdrawal of the mind. Modern scholars such as Mahāprajña have noted that this system of yoga already existed in Śaiva tantra and that Śubhacandara developed his system based on the ''Navacakreśvara-tantra'' and that this system is also present in Abhinavagupta’s Tantrāloka''.''

The Yogaśāstra

''Yogaśāstra'' (''lit.'' "Yoga treatise") is a 12th-century Sanskrit text by Hemachandra on Svetambara Jainism. It is a treatise on the "rules of conduct for laymen and ascetics", wherein "yoga" means "ratna-traya" (three jewels), i.e. right ...

of Hemacandra

Hemachandra was a 12th century () Indian Jain saint, scholar, poet, mathematician, philosopher, yogi, grammarian, law theorist, historian, lexicographer, rhetorician, logician, and prosodist. Noted as a prodigy by his contemporaries, he ...

(12th c. CE) closely follows the model of Śubhacandra. This trend of adopting ideas from the Brāhmaṇical and tantric Śaiva traditions continues with the work of the later Śvetāmbara upādhyāya Yaśovijaya (1624–1688), who wrote many works on yoga.

During the 17th century, Ācārya Vinayavijaya composed the ''Śānta-sudhārasabhāvanā'' in Sanskrit which teaches sixteen anuprekṣā, or contemplations.

Modern history

The growth and popularity of mainstream

The growth and popularity of mainstream Yoga

Yoga (; sa, योग, lit=yoke' or 'union ) is a group of physical, mental, and spiritual practices or disciplines which originated in ancient India and aim to control (yoke) and still the mind, recognizing a detached witness-conscio ...

and Hindu meditation practices influenced a revival in various Jain communities, especially in the Śvētāmbara Terapanth order. These systems sought to "promote health and well-being and pacifism, via meditative practices as “secular” nonreligious tools." 20th century Jain meditation systems were promoted as universal systems accessible to all, drawing on modern elements, using new vocabulary designed to appeal to the lay community, whether Jains or non-Jains. It is important to note that these developments happened mainly among Śvētāmbara

The Śvētāmbara (; ''śvētapaṭa''; also spelled ''Shwethambara'', ''Svetambar'', ''Shvetambara'' or ''Swetambar'') is one of the two main branches of Jainism, the other being the ''Digambara''. Śvētāmbara means "white-clad", and refers ...

sects, while Digambara

''Digambara'' (; "sky-clad") is one of the two major schools of Jainism, the other being '' Śvētāmbara'' (white-clad). The Sanskrit word ''Digambara'' means "sky-clad", referring to their traditional monastic practice of neither possessing n ...

groups generally did not develop new modernist meditation systems. Digambara sects instead promote the practice of self-study ( Svādhyāya) as a form of meditation, influenced by the work of Kundakunda

Kundakunda was a Digambara Jain monk and philosopher, who likely lived in the 2nd CE century CE or later.

His date of birth is māgha māsa, śukla pakṣa, pañcamī tithi, on the day of Vasant Panchami.

He authored many Jain texts such as: ...

. This practice of self study (reciting scriptures and thinking about the meaning) is included in the practice of equanimity (sāmāyika

''Sāmāyika'' is the vow of periodic concentration observed by the Jains. It is one of the essential duties prescribed for both the '' Śrāvaka'' (householders) and ascetics. The preposition ''sam'' means one state of being. To become one is ...

) which is the spiritual practice emphasized by 20th century Digambara sects.

The Digambara Jain scholar Kundakunda, in his ''Pravacanasara'' states that a Jain mendicant should meditate on "I, the pure self". Anyone who considers his body or possessions as "I am this, this is mine" is on the wrong road, while one who meditates, thinking the antithesis and "I am not others, they are not mine, I am one knowledge" is on the right road to meditating on the "soul, the pure self".

Terāpanth ''prekṣā-dhyāna''

The modern era saw the rise of a newŚvētāmbara

The Śvētāmbara (; ''śvētapaṭa''; also spelled ''Shwethambara'', ''Svetambar'', ''Shvetambara'' or ''Swetambar'') is one of the two main branches of Jainism, the other being the ''Digambara''. Śvētāmbara means "white-clad", and refers ...

sect, the Śvētāmbara Terapanth, founded by Ācārya Bhikṣu, who was said to be able to practice breath retention (hold his breath) for two hours. He also practiced ātāpanā by sitting under the scorching sun for hours while chanting and visualizing yantra

Yantra () (literally "machine, contraption") is a geometrical diagram, mainly from the Tantric traditions of the Indian religions. Yantras are used for the worship of deities in temples or at home; as an aid in meditation; used for the benefits ...

s. Further Terapanth scholars like Jayācārya wrote on various meditation practices, including a devotional visualization of the tīrthaṅkaras

In Jainism, a ''Tirthankara'' (Sanskrit: '; English: literally a 'ford-maker') is a saviour and spiritual teacher of the ''dharma'' (righteous path). The word ''tirthankara'' signifies the founder of a '' tirtha'', which is a fordable passag ...

in various colors and “awareness of breathing” (sāsā-surat), this influenced the later “perception of breathing” (śvāsa–prekṣā) and the meditation on auras (leśyā-dhyāna) of Ācārya Mahāprajña.

Tulasī (1913–1997) and Ācārya Mahāprajña (1920– 2010) developed a system termed ''prekṣā-dhyāna'' which is a combination of ancient wisdom and modern science. it is based on Jain Canons. It included "meditative techniques of perception,Kayotsarg, Anupreksha,mantra, posture (āsana), breath control (prāṇāyāma), hand and body gestures (mudrā), various bodily locks (bandha), meditation (dhyāna) and reflection (bhāvanā)." The scholar of religion Andrea Jain states that she was convinced that Mahāprajña and others across the world were attempting "to attract people to preksha dhyana by making it intersect with the global yoga market".

The key texts of this meditation system are ''Prekṣā-Dhyāna: Ādhāra aura Svarūpa'' (Prekṣā Meditation: Basis and Form, 1980), ''Prekṣā-Dhyāna: Prayoga aura Paddhatti'' (Prekṣā Meditation: Theory and Practice, 2010) and ''Prekṣā-Dhyāna: Darśana aura Prayoga'' (Prekṣā Meditation: Philosophy and Practice, 2011). meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

system is said to be firmly grounded in the classic Jain metaphysical mind body dualism in which the self (jiva

''Jiva'' ( sa, जीव, IAST: ) is a living being or any entity imbued with a life force in Hinduism and Jainism. The word itself originates from the Sanskrit verb-root ''jīv'', which translates as 'to breathe' or 'to live'. The ''jiva'', as ...

, characterized by consciousness, ''cetana'' which consists of knowledge, ''jñāna'' and intuition, ''darśana'') is covered over by subtle and gross bodies.

''Prekṣā'' means "to perceive carefully and profoundly". In ''prekṣā'', perception always means an impartial experience bereft of the duality of like and dislike, pleasure and pain, attachment or aversion. Meditative progress proceeds through the different gross and subtle bodies, differentiating between them and the pure consciousness of jiva. Mahāprajña interprets the goal of this to mean to “perceive and realise the most subtle aspects of consciousness by your conscious mind (''mana'').” Important disciplines in the system are - Synchrony of mental and physical actions or simply present mindedness or complete awareness of one's actions, disciplining the reacting attitude, friendliness, diet, silence, spiritual vigilance.

The mature ''prekṣā'' system is taught using an eight limb hierarchical schema, where each one is necessary for practicing the next:

# Relaxation ( ''kāyotsarga''), abandonment of the body, also “relaxation (''śithilīkaraṇa'') with self-awareness,” allows vital force (prāṇa) to flow.

# Internal Journey (''antaryātrā''), this is based on the practice of directing the flow of vital energy ( ''prāṇa-śakti'') in an upward direction, interpreted as being connected with the nervous system.

# Perception of Breathing (''śvāsaprekon''), of two types: (1) perception of long or deep breathing (''dīrgha-śvāsa-prekṣā'') and (2) perception of breathing through alternate nostrils (''samavṛtti-śvāsa-prekṣā'').

# Perception of Body (''śarīraprekṣā''), one becomes aware of the gross physical body (''audārika-śarīra''), the fiery body (''taijasa-śarīra'') and karmic body (''karmaṇa-śarīra''), this practice allows one to perceive the self through the body.

# Perception of Psychic Centres (''caitanyakendra-prekṣā''), defined as locations in the subtle body that contain ‘dense consciousness’ (saghana-cetanā), which Mahāprajña maps into the endocrine system.

# Perception of Psychic Colors (''leśyā-dhyāna''), these are subtle consciousness radiations of the soul, which can be malevolent or benevolent and can be transformed.

# Auto-Suggestion (''bhāvanā''), Mahāprajña defines bhāvanā as “repeated verbal reflection”, infusing the psyche (''citta'') with ideas through strong resolve and generating "counter-vibrations" which eliminate evil impulses.

# Contemplation ('' anuprekṣā''), contemplations are combined with the previous steps of dhyana in different ways. The contemplations can often be secular in nature.

A few important contemplation themes are - Impermanence, Solitariness, and Vulnerability. Regular practice is believed to strengthen the immune system and build up stamina to resist against aging, pollution, viruses, diseases. Meditation practice is an important part of the daily lives of the religion's monks.

Mahāprajña also taught subsidiary limbs to ''prekṣā-dhyāna'' which would help support the meditations in a holistic manner, these are Prekṣā-yoga ( posture and breathing control) and Prekṣā-cikitsā (therapy). Mantras such as ''Arham'' are also used in this system.

Other traditions

Citrabhānu (b. 1922) was a Jain monk who moved to the West in 1971, and founded the first Jain meditation center in the world, the Jaina Meditation International Centre in New York City. He eventually married and became a lay teacher of a new system called "Jain meditation" (JM), on which he wrote various books. The core of his system consists of three steps (tripadī): 1. who am I? (kohum), 2. I am not that (nahum) (not non-self), 3. I am that (sohum) (I am the self). He also makes use of classic Jain meditations such as the twelve reflections (thought taught in a more optimistic, modern way), Jaina mantras, meditation on the seven chakras, as well as Hatha Yoga techniques. Ācārya Suśīlakumāra (1926–1994) of theSthānakavāsī

''Sthānakavāsī'' is a sect of Śvētāmbara Jainism. It believes that idol worship is not essential in the path of soul purification and attainment of Nirvana/Moksha. Sthānakavāsī accept thirty-two of the Jain Agamas, the Svetambara ...

tradition founded “Arhum Yoga” (Yoga on Omniscient) and established a Jain community called the “Arhat Saṅgha” in New Jersey in 1974. His meditation system is strongly tantric and employs mantras (mainly the namaskār), nyasa, visualization and chakras.

The Sthānakavāsī Ācārya Nānālāla (1920–1999), developed a Jaina meditation called Samīkṣaṇa-dhyāna (looking at thoroughly, close investigation) in 1981. The main goal of samīkṣaṇa-dhyāna is the experience of higher consciousness within the self and liberation in this life. Samīkṣaṇa-dhyāna is classified into two categories: introspection of the passions (kaṣāya samīkṣaṇa) and samatā-samīkṣaṇa, which includes introspection of the senses (indriya samīkṣaṇa), introspection of the vow (vrata samīkṣaṇa) introspection of the karma (karma samīkṣaṇa), introspection of the Self (ātma samīkṣaṇa) and others.

Bhadraṅkaravijaya (1903–1975) of the Tapāgaccha sect founded “Sālambana Dhyāna” (Support Meditation). According to Samani Pratibha Pragya, most of these practices "seem to be a deritualisation of pūjā in a meditative form, i.e. he recommended the mental performance of pūjā." These practices (totally 34 different meditations) focus on meditating on arihantas and can make use of mantras, hymns (stotra), statues (mūrti) and diagrams (yantra).

Ācārya Śivamuni (b. 1942) of the Śramaṇa Saṅgha is known for his contribution of “Ātma Dhyāna” (Self-Meditation). The focus in this system is directly meditating on the nature of the self, making use of the mantra ''so’ham'' and using the Acaranga sutra as the main doctrinal source.

Muni Candraprabhasāgara (b. 1962) introduced “Sambodhi Dhyāna” (Enlightenment-Meditation) in 1997. It mainly makes use of the mantra Om, breathing meditation, the chakras and other yogic practices.

''Sāmāyika''

The name ''Sāmāyika'', the term for Jain meditation, is derived from the term ''samaya'' "time" in

The name ''Sāmāyika'', the term for Jain meditation, is derived from the term ''samaya'' "time" in Prakrit

The Prakrits (; sa, prākṛta; psu, 𑀧𑀸𑀉𑀤, ; pka, ) are a group of vernacular Middle Indo-Aryan languages that were used in the Indian subcontinent from around the 3rd century BCE to the 8th century CE. The term Prakrit is usu ...

. Jains also use ''samayika'' to denote the practice of meditation. The aim of ''Sāmāyika'' is to transcend our daily experiences as the "constantly changing" human beings, called Jiva

''Jiva'' ( sa, जीव, IAST: ) is a living being or any entity imbued with a life force in Hinduism and Jainism. The word itself originates from the Sanskrit verb-root ''jīv'', which translates as 'to breathe' or 'to live'. The ''jiva'', as ...

, and allow identification with the "changeless" reality in practitioner, called the atman Atman or Ātman may refer to:

Film

* ''Ātman'' (1975 film), a Japanese experimental short film directed by Toshio Matsumoto

* ''Atman'' (1997 film), a documentary film directed by Pirjo Honkasalo

People

* Pavel Atman (born 1987), Russian hand ...

. One of the main goals of ''Sāmāyika'' is to inculcate equanimity, to see all the events equanimously. It encourages to be consistently spiritually vigilant. ''Sāmāyika'' is practiced in all the Jain sects and communities. Samayika is an important practice during Paryushana

Das Lakshana'' or ''Paryushana is the most important annual holy event for Jains and is usually celebrated in August or September in Hindi calendar (indian calendar) Bhadrapad Month's Shukla Paksha. Jains increase their level of spiritual int ...

, a special eight- or ten-day period.

For householders

In Jainism, six essential duties are prescribed for a '' śrāvaka'' (householder), out of which one duty is ''Samayika''. These help the laity in achieving the principle of ''ahimsa

Ahimsa (, IAST: ''ahiṃsā'', ) is the ancient Indian principle of nonviolence which applies to all living beings. It is a key virtue in most Indian religions: Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism.Bajpai, Shiva (2011). The History of India � ...

'' which is necessary for his/her spiritual upliftment. The ''sāmayika vrata'' (vow to meditate) is intended to be observed three times a day if possible; other-wise at least once daily. Its objective is to enable the ''śrāvaka'' to abstain from all kinds of sins during the period of time fixed for its observance. The usual duration of the ''sāmayika'' vow is an ''antara mūharta'' (a period of time not exceeding 48 minutes). During this period, which the layman spends in study and meditation, he vows to refrain from the commission of the five kinds of sin — injury, falsehood, theft, unchastity and love of material possessions in any of the three ways. These three ways are:-

*by an act of mind, speech or body (''krita''),

*inciting others to commit such an act (''kārita''),

*approving the commission of such an act by others (''anumodanā'').

In performing ''sāmayika'' the ''śrāvaka'' has to stand facing north or east and bow to the ''Pañca-Parameṣṭhi

The (Sanskrit: पञ्च परमेष्ठी for "five supreme beings") in Jainism are a fivefold hierarchy of religious authorities worthy of veneration.

Overview

The five supreme beings are:

#'' Arihant'': The awakened souls wh ...

''. He then sit down and recites the Namokara mantra

The Ṇamōkāra mantra or Navkar Mantra is the most significant mantra in Jainism, and one of the oldest mantras in continuous practice. This is the first prayer recited by the Jains while meditating. The mantra is also variously referred to ...

a certain number of times, and finally devotes himself to holy meditation. This consists in:

*''pratikramana'', recounting the sins committed and repenting for them,

*''pratyākhyanā'', resolving to avoid particular sins in future,

*''sāmayika karma'', renunciation of personal attachments, and the cultivation of a feeling of regarding every body and thing alike,

*''stuti'', praising the four and twenty Tīrthankaras,

*''vandanā'', devotion to a particular ''Tirthankara'', and

*'' kāyotsarga'', withdrawal of attention from the body (physical personality) and becoming absorbed in the contemplation of the spiritual Self.

''Sāmayika'' can be performed anywhere- a temple, private residence, forest and the like. But the place shouldn't be open to disturbance. According to the Jain text, Ratnakaranda śrāvakācāra, while performing ''sāmayika'', one should meditate on:

For ascetics

The ascetic has to perform the ''sāmāyika'' three times a day. Champat Rai Jain in his book, ''The Key of Knowledge'' wrote:Techniques

According to the some commonly practiced ''yoga'' systems, high concentration is reached by meditating in an easy (preferably lotus) posture in seclusion and staring without blinking at the rising sun, a point on the wall, or the tip of the nose, and as long as one can keep the mind away from the outer world, this strengthens concentration. ''Garuda'' is the name Jainism gives to the yoga of self-discipline and discipline of mind, body and speech, so that even earth, water, fire and air can come under one’s control. ''Śiva'' is in Jainism control over the passions and the acquisition of such self-discipline that under all circumstances equanimity is maintained. '' Prānayāma'' – breathing exercises – are performed to strengthen the flows of life energy. Through this, the elements of the constitution – earth, water, fire and air – are also strengthened. At the same time the five ''chakras'' are controlled. ''Prānayāma'' also helps to stabilize one’s thinking and leads to unhampered direct experience of the events around us. Next one practices '' pratyāhāra''. Pratyāhāra means that one directs the senses away from the enjoyment of sensual and mental objects. The senses are part of the nervous system, and their task is to send data to the brain through which the mind as well as the soul is provided with information. The mind tends to enjoy this at the cost of the soul as well as the body. ''Pratyāhāra'' is obtained by focusing the mind on one point for the purpose of receiving impulses: on theeye

Eyes are organs of the visual system. They provide living organisms with vision, the ability to receive and process visual detail, as well as enabling several photo response functions that are independent of vision. Eyes detect light and conv ...

s, ears, tip of the nose

A nose is a protuberance in vertebrates that houses the nostrils, or nares, which receive and expel air for respiration alongside the mouth. Behind the nose are the olfactory mucosa and the sinuses. Behind the nasal cavity, air next pass ...

, the brow, the navel

The navel (clinically known as the umbilicus, commonly known as the belly button or tummy button) is a protruding, flat, or hollowed area on the abdomen at the attachment site of the umbilical cord. All placental mammals have a navel, altho ...

, the head

A head is the part of an organism which usually includes the ears, brain, forehead, cheeks, chin, eyes, nose, and mouth, each of which aid in various sensory functions such as sight, hearing, smell, and taste. Some very simple animals may no ...

, the heart

The heart is a muscular organ found in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon diox ...

or the palate

The palate () is the roof of the mouth in humans and other mammals. It separates the oral cavity from the nasal cavity.

A similar structure is found in crocodilians, but in most other tetrapods, the oral and nasal cavities are not truly s ...

.

Contemplation is an important wing in Jain meditation. The practitioner meditates or reflects deeply on subtle facts or philosophical aspects. The first type is ''Agnya vichāya'', in which one meditates deeply on the seven elementary facts - life and non-life, the inflow, bondage, stoppage and removal of ''karmas'', and the final accomplishment of liberation. The second is ''Apaya vichāya'', in which incorrect insights and behavior in which “sleeping souls” indulge, are reflected upon. The third is ''Vipaka vichāya dharma dhyāna'', in which one reflects on the eight causes or basic types of ''karma''. The fourth is ''Sansathan vichāya dharma dhyāna'', when one thinks about the vastness of the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. A ...

and the loneliness of the soul, which has had to face the results of its own causes all alone. A few important contemplation themes in Preksha meditation are - Impermanence, Solitariness, Vulnerability.

In ''pindāstha-dhyāna'' one imagines oneself sitting all alone in the middle of a vast

In ''pindāstha-dhyāna'' one imagines oneself sitting all alone in the middle of a vast ocean

The ocean (also the sea or the world ocean) is the body of salt water that covers approximately 70.8% of the surface of Earth and contains 97% of Earth's water. An ocean can also refer to any of the large bodies of water into which the wo ...

of milk

Milk is a white liquid food produced by the mammary glands of mammals. It is the primary source of nutrition for young mammals (including breastfed human infants) before they are able to digest solid food. Immune factors and immune-modulati ...

on a lotus

Lotus may refer to:

Plants

*Lotus (plant), various botanical taxa commonly known as lotus, particularly:

** ''Lotus'' (genus), a genus of terrestrial plants in the family Fabaceae

**Lotus flower, a symbolically important aquatic Asian plant also ...

flower, meditating on the soul. There are no living beings around whatsoever. The lotus is identical to ''Jambūdvīpa'', with Mount ''Meru'' as its stalk. Next the meditator imagines a 16-petalled lotus at the level of his navel

The navel (clinically known as the umbilicus, commonly known as the belly button or tummy button) is a protruding, flat, or hollowed area on the abdomen at the attachment site of the umbilical cord. All placental mammals have a navel, altho ...

, and on each petal are printed the (Sanskrit) letters “arham“ and also an inverted lotus of 8 petals at the location of his heart

The heart is a muscular organ found in most animals. This organ pumps blood through the blood vessels of the circulatory system. The pumped blood carries oxygen and nutrients to the body, while carrying metabolic waste such as carbon diox ...

. Suddenly the lotus on which one is seated flares up at the navel and flames gradually rise up to the inverted lotus, burning its petals with a rising gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile ...

en flame

A flame (from Latin '' flamma'') is the visible, gaseous part of a fire. It is caused by a highly exothermic chemical reaction taking place in a thin zone. When flames are hot enough to have ionized gaseous components of sufficient density the ...

which not only burns his or her body, but also the inverted lotus at the heart. The flames rise further up to the throat

In vertebrate anatomy, the throat is the front part of the neck, internally positioned in front of the vertebrae. It contains the pharynx and larynx. An important section of it is the epiglottis, separating the esophagus from the trachea (windpi ...

whirling in the shape of a swastika and then reach the head, burning it entirely, while taking the form of a three-sided pyramid of golden flames above the head, piercing the skull

The skull is a bone protective cavity for the brain. The skull is composed of four types of bone i.e., cranial bones, facial bones, ear ossicles and hyoid bone. However two parts are more prominent: the cranium and the mandible. In humans, t ...

sharp end straight up. The whole physical body is charred, and everything turns into glowing ashes. Thus the ''pinda'' or body is burnt off and the pure soul survives. Then suddenly a strong wind blows off all the ashes; and one imagines that a heavy rain shower washes all the ashes away, and the pure soul remains seated on the lotus. That pure Soul has infinite virtues, it is Myself. Why should I get polluted at all? One tries to remain in his purest nature. This is called ''pindāstha dhyāna'', in which one ponders the reality of feeling and experiencing.

In ''padāstha dhyāna'' one focuses on some mantras

A mantra (Pali: ''manta'') or mantram (मन्त्रम्) is a sacred utterance, a numinous sound, a syllable, word or phonemes, or group of words in Sanskrit, Pali and other languages believed by practitioners to have religious, m ...

, words or themes. Couple of important mantra

A mantra ( Pali: ''manta'') or mantram (मन्त्रम्) is a sacred utterance, a numinous sound, a syllable, word or phonemes, or group of words in Sanskrit, Pali and other languages believed by practitioners to have religious, ...

examples are, OM - it signifies remembrance of the five classes of spiritual beings (the embodied and non-embodied Jinas, the ascetics, the monks and the nuns), pronouncing the word “Arham” makes one feel “I myself am the omniscient soul” and one tries to improve one’s character accordingly. One may also pronounce the holy name of an ''arhat'' and concentrate on the universal richness of the soul.

In ''rūpāstha dhyāna'' one reflects on the embodiments of arihants, the svayambhuva (the self-realized), the omniscients and other enlightened people and their attributes, such as three umbrellas and whiskers – as seen in many icons – unconcerned about one’s own body, but almighty and benevolent to all living beings, destroyer of attachment, enmity, etc. Thus the meditator as a human being concentrates his or her attention on the virtues of the omniscients to acquire the same virtues for himself.

''Rūpātita dhyāna'' is a meditation in which one focuses on bodiless objects such as the liberated souls or siddha

''Siddha'' (Sanskrit: '; "perfected one") is a term that is used widely in Indian religions and culture. It means "one who is accomplished." It refers to perfected masters who have achieved a high degree of physical as well as spiritual ...

s, which stand individually and collectively for the infinite qualities that such souls have earned. That omniscient, potent, omnipresent, liberated and untainted soul is called a ''nirañjāna'', and this stage can be achieved by right vision, right knowledge and right conduct only. Right vision, right knowledge and right conduct begin the fourth stage of the 14-fold path.

The ultimate aim of such yoga and meditation is to pave the way for the spiritual elevation and salvation of the soul. Some yogi

A yogi is a practitioner of Yoga, including a sannyasin or practitioner of meditation in Indian religions.A. K. Banerjea (2014), ''Philosophy of Gorakhnath with Goraksha-Vacana-Sangraha'', Motilal Banarsidass, , pp. xxiii, 297-299, 331 ...

s develop their own methods for meditation.

See also

*Buddhist meditation

Buddhist meditation is the practice of meditation in Buddhism. The closest words for meditation in the classical languages of Buddhism are ''bhāvanā'' ("mental development") and '' jhāna/dhyāna'' (mental training resulting in a calm and l ...

* Hindu meditation

* Jewish meditation

* Christian meditation

Christian meditation is a form of prayer in which a structured attempt is made to become aware of and reflect upon the revelations of God. The word meditation comes from the Latin word ''meditārī'', which has a range of meanings including to re ...

* Muraqaba

''Murāqabah'' ( ar, مراقبة, : "to observe") is an Islamic methodology, whose aim is a transcendental union with God. Through , a person watches over their heart and soul, to gain insight into one's relation with their creator and their s ...

* Daoist meditation

References

Notes

Citations

Sources

* * * * * * * * * * *External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Jain MeditationMeditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...

Meditation

Meditation is a practice in which an individual uses a technique – such as mindfulness, or focusing the mind on a particular object, thought, or activity – to train attention and awareness, and achieve a mentally clear and emotionally calm ...