Jacob Furth on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

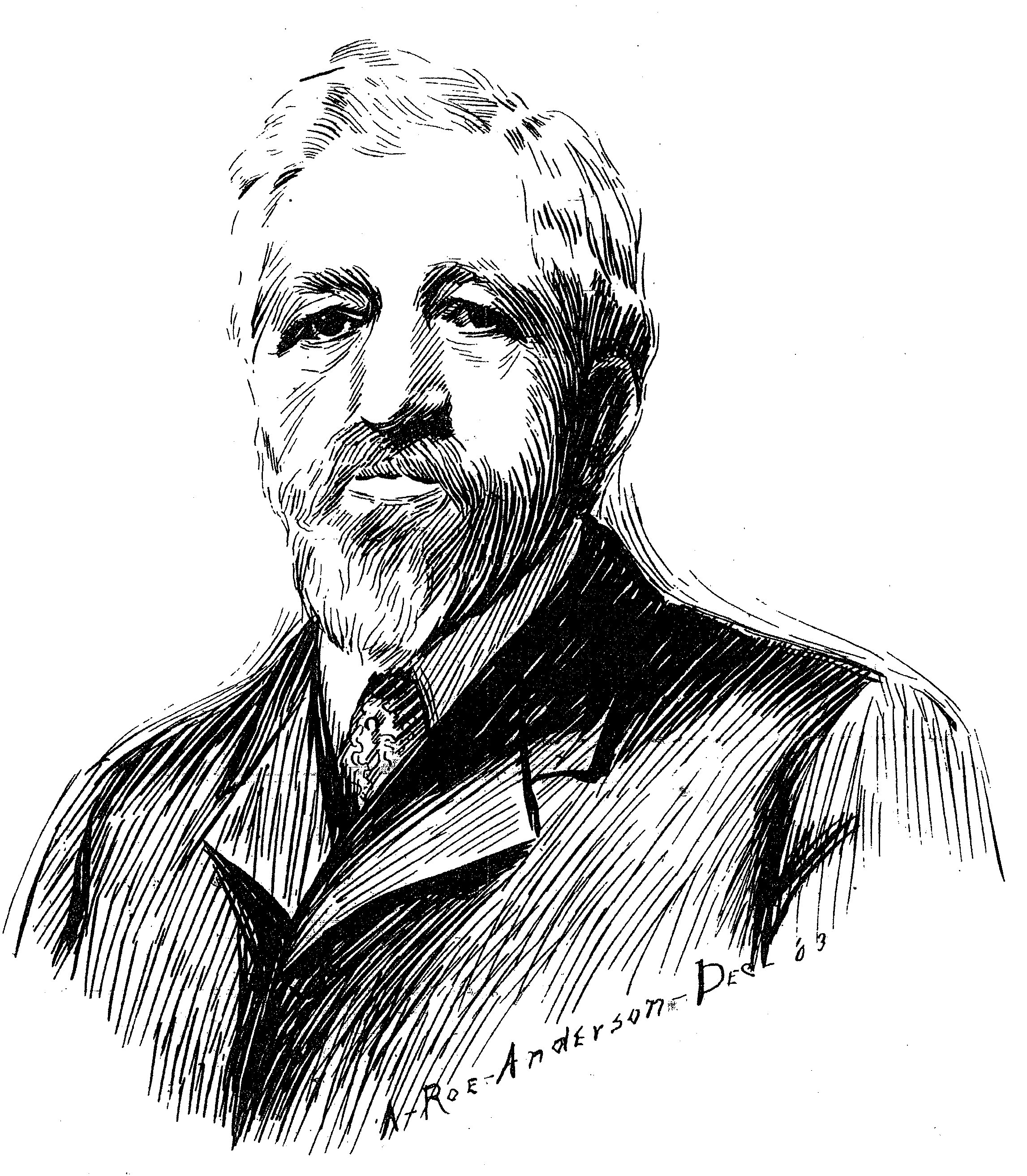

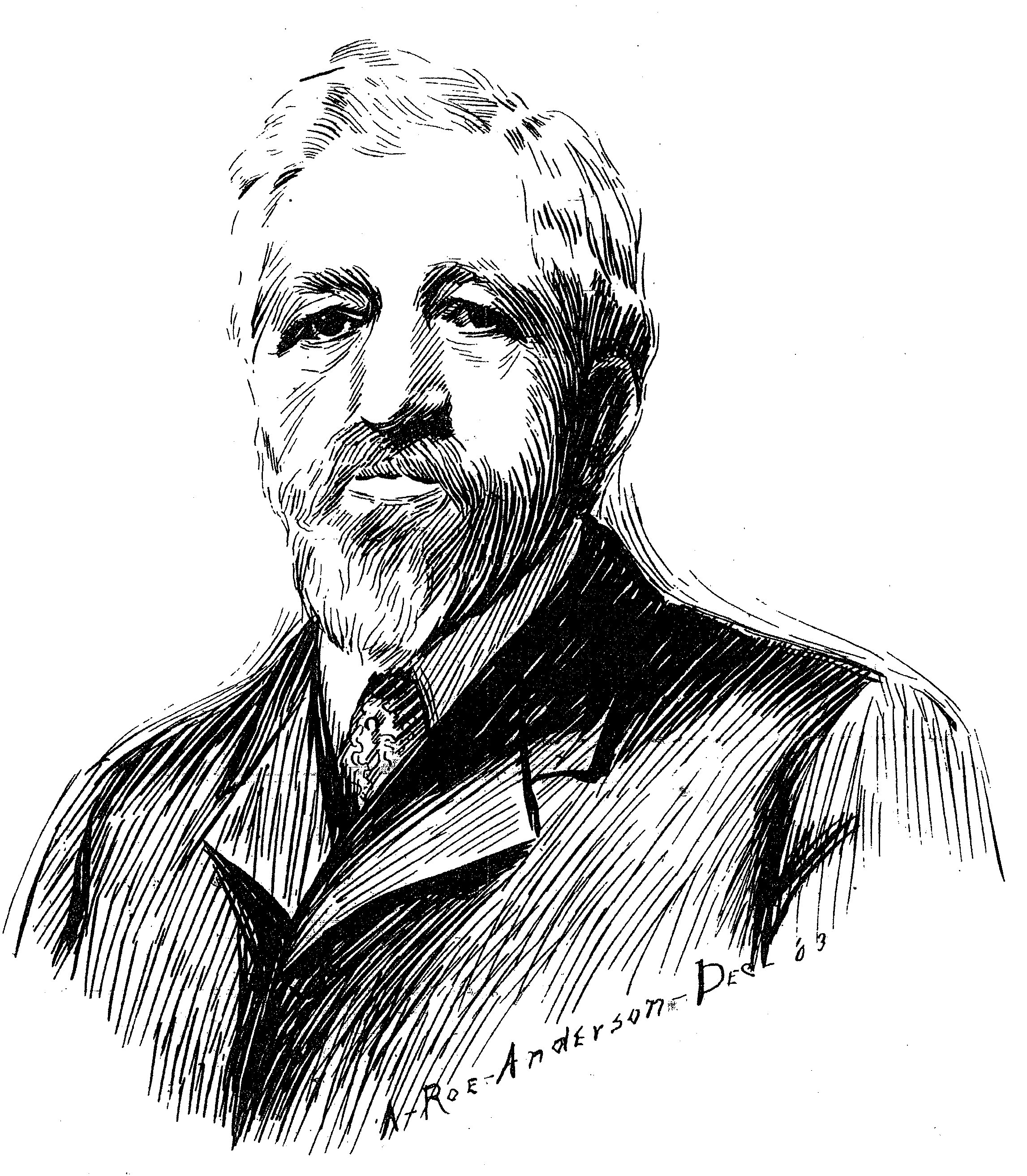

Jacob Furth (November 15, 1840 – June 2, 1914) was an

Jacob Furth (November 15, 1840 – June 2, 1914) was an

Furth, Jacob (1840-1914)

HistoryLink, October 30, 1998. Accessed online 2009-10-06.

In 1882, health problems took Furth to the

In 1882, health problems took Furth to the  Besides the Puget Sound National Bank, he organized the First National Bank of Snohomish in 1896 and remained one of its stockholders and directors the rest of his life. He also founded or co-founded several other Washington State banks, including the Kitsap County Bank in

Besides the Puget Sound National Bank, he organized the First National Bank of Snohomish in 1896 and remained one of its stockholders and directors the rest of his life. He also founded or co-founded several other Washington State banks, including the Kitsap County Bank in  Further, Furth became increasingly involved in the building and management of urban and

Further, Furth became increasingly involved in the building and management of urban and

Harvard Business School Lehman Brothers Collection. Accessed online 2009-10-07. he became president of the Seattle Electric Company (later Puget Power, merged in 1997 into

In eulogizing Furth, Judge Thomas Burke said of him,

Some seventy years later, Bill Speidel was more succinct: "All Jacob Furth did was take a squalid little village named Seattle and turn it into a world class city. He made good on

In eulogizing Furth, Judge Thomas Burke said of him,

Some seventy years later, Bill Speidel was more succinct: "All Jacob Furth did was take a squalid little village named Seattle and turn it into a world class city. He made good on

Guide to the Seattle City Light Department History File 1894-1972

Northwest Digital Archives (NWDA), 2004. Accessed online 2009-10-07. The 1902 election saw strong populist support for public power, leading to the establishment of

Yarrow Point -- Thumbnail History

June 30, 2003. HistoryLink, Accessed online 2009-10-07.

Jacob Furth (November 15, 1840 – June 2, 1914) was an

Jacob Furth (November 15, 1840 – June 2, 1914) was an Austrian Empire

The Austrian Empire (german: link=no, Kaiserthum Oesterreich, modern spelling , ) was a Central-Eastern European multinational great power from 1804 to 1867, created by proclamation out of the realms of the Habsburgs. During its existence, ...

-born American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

entrepreneur and prominent Seattle

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest regio ...

banker. He played a key role in consolidating Seattle's electric power and public transportation infrastructure, and was a member of Ohaveth Sholum Congregation, Seattle's first synagogue

A synagogue, ', 'house of assembly', or ', "house of prayer"; Yiddish: ''shul'', Ladino: or ' (from synagogue); or ', "community". sometimes referred to as shul, and interchangeably used with the word temple, is a Jewish house of worshi ...

.Lee MicklinFurth, Jacob (1840-1914)

HistoryLink, October 30, 1998. Accessed online 2009-10-06.

Bill Speidel

William C Speidel (1912–1988) was a columnist for ''The Seattle Times'' and a self-made historian who wrote the books ''Sons of the Profits'' and ''Doc Maynard, The Man Who Invented Seattle'' about the people who settled and built Seattle, Wa ...

called him "the city's leading citizen for thirty years," adding that Furth "may even have been the most important citizen Seattle ever had.", p. 39.

Clarence Bagley wrote shortly after Furth's death:

Early life

Furth was born in Schwihau,Bohemia

Bohemia ( ; cs, Čechy ; ; hsb, Čěska; szl, Czechy) is the westernmost and largest historical region of the Czech Republic. Bohemia can also refer to a wider area consisting of the historical Lands of the Bohemian Crown ruled by the Bohem ...

(now Švihov, Czech Republic

The Czech Republic, or simply Czechia, is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Historically known as Bohemia, it is bordered by Austria to the south, Germany to the west, Poland to the northeast, and Slovakia to the southeast. The ...

) November 15, 1840, the son of Lazar and Anna (Popper) Furth, Jewish natives of Bohemia. Of their ten sons and two daughters, eight eventually came to America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

. He attended school to the age of thirteen years, then began a career as a confectioner in Budapest

Budapest (, ; ) is the capital and most populous city of Hungary. It is the ninth-largest city in the European Union by population within city limits and the second-largest city on the Danube river; the city has an estimated population ...

. He decided at sixteen (so says Bagley; other sources say 18) to try his fortune in America and made his way to San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

, arriving in 1856.

He had with him letters of introduction to the Schwabacher Brothers,Bill Speidel, ''Through the Eye of the Needle'', p. 40 a prominent Jewish pioneer merchant family firm. After his arrival, he used his last ten dollars to get to Nevada City, California

Nevada City (originally, ''Ustumah'', a Nisenan village; later, Nevada, Deer Creek Dry Diggins, and Caldwell's Upper Store) is the county seat of Nevada County, California, United States, northeast of Sacramento, southwest of Reno and northeas ...

, where the Schwabachers had secured him a position. He clerked mornings and evenings in a clothing store, while attending public schools for about six months to improve his English. When the Schwabachers checked on him after six months, his English was already better than theirs.

He was rapidly promoted, and at the end of three years he was receiving a salary of $US

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

300 per month. He lived frugally, and invested some of his money in a quicksilver mine. By the time the Nevada City store burned in 1862, he had saved enough to open his own clothing and dry-goods store in Shingle Springs, California

Shingle Springs (formerly, Shingle Spring and Shingle) is a census-designated place (CDP) in El Dorado County, California, United States. The population was 4,432 at the 2010 census, up from 2,643 at the 2000 census. It is located about from Sacra ...

. Eight years later, in 1870, he moved Colusa, California

Colusa is a city and county seat of Colusa County, California, located in the Sacramento Valley region of the Central Valley. The population was 5,971 at the 2010 census, up from 5,402 at the 2000 census. Colusi originates from the local Coru N ...

, where he bought into a general mercantile store. The Schwabachers offered him financing, but he told them he had already saved enough to do this on his own. Shortly after his arrival in Colusa, he became Freemason

Freemasonry or Masonry refers to fraternal organisations that trace their origins to the local guilds of stonemasons that, from the end of the 13th century, regulated the qualifications of stonemasons and their interaction with authorities ...

and eventually became master of his lodge. (He would remain a Mason in Seattle.) In 1878, he was able to buy out the older partners in the store, which he owned and operated until 1882.

Banking and financial positions

In 1882, health problems took Furth to the

In 1882, health problems took Furth to the Puget Sound

Puget Sound ( ) is a sound of the Pacific Northwest, an inlet of the Pacific Ocean, and part of the Salish Sea. It is located along the northwestern coast of the U.S. state of Washington. It is a complex estuarine system of interconnected ma ...

region in Washington

Washington commonly refers to:

* Washington (state), United States

* Washington, D.C., the capital of the United States

** A metonym for the federal government of the United States

** Washington metropolitan area, the metropolitan area centered on ...

. There, in cooperation with the Schwabachers he helped organize the Puget Sound National Bank Puget may refer to:

*Puget (surname)

*Puget, Vaucluse, a commune in France

*Puget, Washington, a community in the United States

See also

*Puget Creek

*Puget Island

*Puget Sound

*Puget-Ville

Puget-Ville (; oc, Puget Vila) is a commune in the Va ...

with a capital of fifty thousand dollars, and took charge as its cashier. Former Seattle mayor Bailey Gatzert

Bailey Gatzert (December 29, 1829 – April 19, 1893) was an American politician and the eighth mayor of Seattle, Washington, serving from 1875 to 1876. He was the first Jewish mayor of Seattle, narrowly missing being the first Jewish mayor of ...

, another Schwabacher associate, was the original bank president. The bank officially opened for business in August 1883.Bill Speidel, ''Through the Eye of the Needle'', p. 41. For several months, Furth was the bank's only employee and its only officer in Seattle.

Puget Sound National Bank succeeded and prospered; at all times the earnings of the bank were sufficient to increase the capital stock as needed. In 1893 he became bank president, a role he held until his bank's consolidation with the Seattle National Bank

Seattle ( ) is a seaport city on the West Coast of the United States. It is the seat of King County, Washington. With a 2020 population of 737,015, it is the largest city in both the state of Washington and the Pacific Northwest region of ...

in 1910, after which he became chairman of the board of directors of the latter. Bagley writes, "He became recognized as one of the foremost factors in banking circles in the northwest, thoroughly conversant with every phase of the business and capable of solving many intricate and complex financial problems."

Besides the Puget Sound National Bank, he organized the First National Bank of Snohomish in 1896 and remained one of its stockholders and directors the rest of his life. He also founded or co-founded several other Washington State banks, including the Kitsap County Bank in

Besides the Puget Sound National Bank, he organized the First National Bank of Snohomish in 1896 and remained one of its stockholders and directors the rest of his life. He also founded or co-founded several other Washington State banks, including the Kitsap County Bank in Port Orchard, Washington

Port Orchard is a city in and the county seat of Kitsap County, Washington, United States. It is located due west of West Seattle and is connected to Seattle and Vashon Island via the Washington State Ferries run to Southworth. It is named a ...

(1908), still active today as the Kitsap Bank. In 1884 he organized the California Land & Stock Company, owning a farm in Lincoln County, Washington

Lincoln County is a county located in the U.S. state of Washington. As of the 2020 census, the population was 10,876, making it the fifth-least populous county in the state. The county seat and largest city is Davenport.

Lincoln County was cr ...

, one of the state's largest. Most of the farm was used to raise wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

; it also pastured cattle and horses. This was another company of which Furth would continue as president until his death. He also invested in property, including Seattle real estate and Pacific Northwest

The Pacific Northwest (sometimes Cascadia, or simply abbreviated as PNW) is a geographic region in western North America bounded by its coastal waters of the Pacific Ocean to the west and, loosely, by the Rocky Mountains to the east. Though ...

timber lands.

Further, Furth became increasingly involved in the building and management of urban and

Further, Furth became increasingly involved in the building and management of urban and interurban

The Interurban (or radial railway in Europe and Canada) is a type of electric railway, with streetcar-like electric self-propelled rail cars which run within and between cities or towns. They were very prevalent in North America between 1900 a ...

electric railway

A railway electrification system supplies electric power to railway trains and trams without an on-board prime mover or local fuel supply.

Electric railways use either electric locomotives (hauling passengers or freight in separate cars), ele ...

systems. In 1900, backed by Stone & Webster

Stone & Webster was an American engineering services company based in Stoughton, Massachusetts. It was founded as an electrical testing lab and consulting firm by electrical engineers Charles A. Stone and Edwin S. Webster in 1889. In the early ...

Puget Sound Power & Light CompanyHarvard Business School Lehman Brothers Collection. Accessed online 2009-10-07. he became president of the Seattle Electric Company (later Puget Power, merged in 1997 into

Puget Sound Energy

Puget Sound Energy (PSE) is an energy utility company based in the U.S. state of Washington that provides electrical power and natural gas to the Puget Sound region. The utility serves electricity to more than 1.1 million customers in Island, Ki ...

), which in 1916 operated more than of track. He aided in organizing and became the president of the Puget Sound Electric Railway

The Puget Sound Electric Railway was an interurban railway that ran for 38 milesPerpetual Motion Pictures. '' The Seattle-Tacoma Railway: A Journey into the Past''. Seattle, WA. 1996. between Tacoma and Seattle, Washington in the first quarter of ...

in 1902, controlling the line between Seattle and Tacoma, Washington

Tacoma ( ) is the county seat of Pierce County, Washington, United States. A port city, it is situated along Washington's Puget Sound, southwest of Seattle, northeast of the state capital, Olympia, Washington, Olympia, and northwest of Mount ...

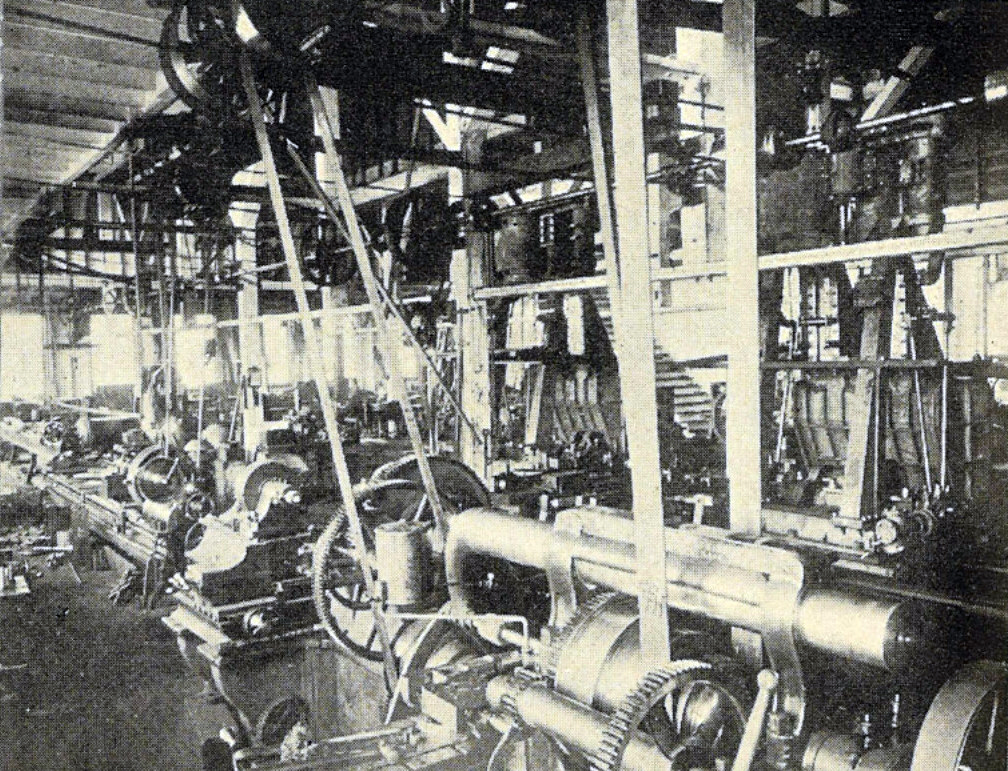

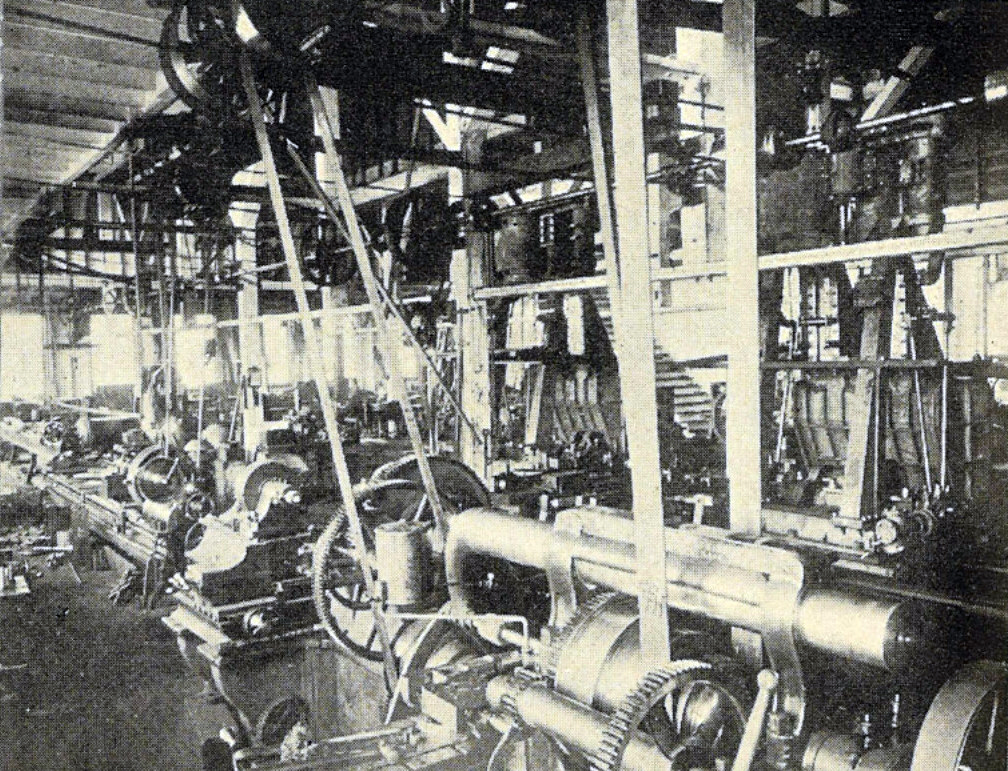

and also owning the street railways in Tacoma and most other Puget Sound cities and towns. He was also president of Seattle's Vulcan Iron Works

Vulcan Iron Works was the name of several iron foundries in both England and the United States during the Industrial Revolution and, in one case, lasting until the mid-20th century. Vulcan, the Roman god of fire and smithery, was a popular na ...

, which he organized in 1887. One of Seattle's first major industrial operations,Bill Speidel, ''Through the Eye of the Needle'', p. 72. it covered an entire Seattle city block at Fifth Avenue and Lane Street in what is now the International District, Seattle's Chinatown

A Chinatown () is an ethnic enclave of Chinese people located outside Greater China, most often in an urban setting. Areas known as "Chinatown" exist throughout the world, including Europe, North America, South America, Asia, Africa and Austra ...

.

Public-minded dealmaker

In eulogizing Furth, Judge Thomas Burke said of him,

Some seventy years later, Bill Speidel was more succinct: "All Jacob Furth did was take a squalid little village named Seattle and turn it into a world class city. He made good on

In eulogizing Furth, Judge Thomas Burke said of him,

Some seventy years later, Bill Speidel was more succinct: "All Jacob Furth did was take a squalid little village named Seattle and turn it into a world class city. He made good on Doc Maynard

David Swinson "Doc" Maynard (March 22, 1808March 13, 1873) was an American pioneer, doctor, and businessman. He was one of Seattle's primary founders. He was an effective civic booster and, compared to other white settlers, a relative advocate ...

's dream."

Shortly after his arrival in Seattle, Furth (along with Gatzert and ''Seattle Post-Intelligencer

The ''Seattle Post-Intelligencer'' (popularly known as the ''Seattle P-I'', the ''Post-Intelligencer'', or simply the ''P-I'') is an online newspaper and former print newspaper based in Seattle, Washington, United States.

The newspaper was foun ...

'' founder John Leary) rescued the Spring Hill Water system from bankruptcy. The privately owned firm supplied the city's water. A new pumping station on Lake Washington

Lake Washington is a large freshwater lake adjacent to the city of Seattle.

It is the largest lake in King County and the second largest natural lake in the state of Washington, after Lake Chelan. It borders the cities of Seattle on the west, ...

in what is now the Mount Baker

Mount Baker (Lummi: '; nok, Kw’eq Smaenit or '), also known as Koma Kulshan or simply Kulshan, is a active glacier-covered andesitic stratovolcano in the Cascade Volcanic Arc and the North Cascades of Washington in the United States. Mount ...

neighborhood made the system viable, doubling its previous capacity. Although the deal was initially viewed largely as a matter of public service, Furth's financial acumen resulted in a profit. After the Great Seattle Fire

The Great Seattle Fire was a fire that destroyed the entire central business district of Seattle, Washington on June 6, 1889. The conflagration lasted for less than a day, burning through the afternoon and into the night, and during the same sum ...

of June 6, 1889, which the Spring Hill system failed to put out, Furth broke with most of the city's business interests to back city engineer R. H. Thomson

Robert Holmes Thomson (born 1947), known as R. H. Thomson, is a Canadian television, film, and stage actor. With a career spanning five decades he remains a regular presence on Canadian movie screens and television. He has received numerous ...

's proposal for a municipally owned gravity-flow system. J.J. McGilvra was the only other member of the Seattle establishment to take this side in the fight.Bill Speidel, ''Through the Eye of the Needle'', p. 42.

Furth assembled $150 million in bank loans after the Great Seattle Fire, and promised that his bank would make no effort to profit from the fire. In the Panic of 1893

The Panic of 1893 was an economic depression in the United States that began in 1893 and ended in 1897. It deeply affected every sector of the economy, and produced political upheaval that led to the political realignment of 1896 and the pres ...

, he dissuaded the directors of his Seattle National Bank from calling in all loans. "What you propose," he said, "may be good banking, but it is not human." A rapid trip to New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

secured enough capital to buy control of the bank and weather the crisis.

Financing of shipping and railroads

Shortly after the Great Seattle Fire, Furth financed seaman Joshua Green in acquiring his first vessel, the ''Fannie Lake'' (or ''Fanny Lake''); Green would eventually consolidate the Puget Sound Mosquito Fleet and center it at Seattle, a major factor in Seattle's rise to regional preeminence, and later became a banker himself. Furth arranged financing for Green's first shipping firm, theLa Conner Trading and Transportation Company

The La Conner Trading and Transportation Company was founded in the early 1900s by Joshua Green and others, to engage in the shipping business on Puget Sound.

Formation

The La Conner Trading and Transportation Company was formed in the early 189 ...

, as well as another successful steamboat line, the Anderson Steamboat Company

Lake Washington Shipyards was a shipyard in the Pacific Northwest, northwest United States, located in Houghton, Washington (today Kirkland, Washington, Kirkland) on the shore of Lake Washington, east of Seattle. Today, the shipyards are the sit ...

.

Furth worked with both the E.H. Harriman

Edward Henry Harriman (February 20, 1848 – September 9, 1909) was an American financier and railroad executive.

Early life

Harriman was born on February 20, 1848, in Hempstead, New York, the son of Orlando Harriman Sr., an Episcopal clergyma ...

and James J. Hill

James Jerome Hill (September 16, 1838 – May 29, 1916) was a Canadian-American railroad director. He was the chief executive officer of a family of lines headed by the Great Northern Railway, which served a substantial area of the Upper Midwes ...

interests to bring their respective railroads to Seattle, finally bringing Seattle the transcontinental rail connection it had sought for decades.

Stone & Webster

Furth's work with Stone & Webster—to consolidate the city's public transportation system and to consolidate and develop electrical power sources to power them—was more controversial. In the 1890s, Seattle had fourteen independentstreetcar

A tram (called a streetcar or trolley in North America) is a rail vehicle that travels on tramway tracks on public urban streets; some include segments on segregated right-of-way. The tramlines or networks operated as public transport are ...

and cable car Cable car most commonly refers to the following cable transportation systems:

* Aerial lift, such as aerial tramways and gondola lifts, in which the vehicle is suspended in the air from a cable

** Aerial tramway

** Chairlift

** Gondola lift

*** Bi ...

lines; all but J.J. McGilvra's line on Madison Street eventually failed financially, most of them in the wake of the Panic of 1893.Bill Speidel, ''Through the Eye of the Needle'', p. 81–83. Most of them survived only by funding operations out of what should have been maintenance capital.Richard C. Berner, ''Seattle 1900-1920: From Boomtown, Urban Turbulence, to Restoration'', Seattle: Charles Press, 1991, , p. 42. Working with Stone & Webster, Furth stitched together a single system, the Seattle Electric Company and—under pressure from the Seattle City Council

The Seattle City Council is the legislative body of the city of Seattle, Washington. The Council consists of nine members serving four-year terms, seven of which are elected by electoral districts and two of which are elected in citywide at-lar ...

, in order to gain the franchise—established a flat fare, initially 5 cents including transfers (previously, a single trip could have cost as much as 40 cents). In 1902, this was expanded with Interurban

The Interurban (or radial railway in Europe and Canada) is a type of electric railway, with streetcar-like electric self-propelled rail cars which run within and between cities or towns. They were very prevalent in North America between 1900 a ...

s to Tacoma and Renton.

However, in contrast to the post-Fire investment that had so clearly been for the common good of the city, Seattle Electric was a for-profit, private undertaking, owned largely by East Coast interests. This put Furth in direct conflict with the advocates of local public ownership. Furthermore, the consolidation of the streetcar lines did not solve the maintenance issues, with "overcrowding, erratic service, accidents, ndopen cars even in winter" remaining common.Richard C. Berner, ''Seattle 1900-1920: From Boomtown, Urban Turbulence, to Restoration'', Seattle: Charles Press, 1991, , p. 43.

The City of Seattle had been involved in municipal power generation since the 1890 creation of the Department of Lighting and Water Works.Shannon Lynch and Scott ClineGuide to the Seattle City Light Department History File 1894-1972

Northwest Digital Archives (NWDA), 2004. Accessed online 2009-10-07. The 1902 election saw strong populist support for public power, leading to the establishment of

Seattle City Light

Seattle City Light is the public utility providing electricity to Seattle, Washington, in the United States, and parts of its metropolitan area, including all of Shoreline and Lake Forest Park and parts of unincorporated King County, Burien, No ...

and the city's involvement in hydroelectricity

Hydroelectricity, or hydroelectric power, is Electricity generation, electricity generated from hydropower (water power). Hydropower supplies one sixth of the world's electricity, almost 4500 TWh in 2020, which is more than all other Renewabl ...

. For the next half-century, Seattle would be variously served by municipal electricity and by Seattle Electric and its successors, until the city bought out its private competitor in 1951.

Lou Graham connection

According to Bill Speidel, brothel-ownerLou Graham

Louis Krebs Graham (born January 7, 1938) is an American professional golfer who won six PGA Tour tournaments including the 1975 U.S. Open. Most of his wins were in the 1970s.

Lou Graham was born in Nashville, Tennessee. He started playing g ...

was effectively Furth's silent partner from her 1888 arrival in Seattle until her death in 1903. He provided the banking, real estate, and political connections she required to establish the city's leading parlor house; when people came to him seeking a loan, and he thought their idea was good but that he'd never get it past his board of directors, he referred them to Graham for an informal, high-interest loan. She may have been instrumental in saving Puget Sound National Bank from a bank run

A bank run or run on the bank occurs when many clients withdraw their money from a bank, because they believe the bank may cease to function in the near future. In other words, it is when, in a fractional-reserve banking system (where banks no ...

during the Panic of 1893, by ostentatiously making a large deposit. When she died, a Puget Sound National Bank employee became administrator of her estate.

The Schricker scandal

Toward the end of his life, Furth's reputation was somewhat tarnished by a scandal related to a bank inLa Conner, Washington

La Conner is a town in Skagit County, Washington, United States with a population of 965 at the 2020 census. It is included in the Mount Vernon– Anacortes, Washington Metropolitan Statistical Area. The town hosts several events as part of ...

, although Furth was posthumously acquitted of all culpability.Bill Speidel, ''Through the Eye of the Needle'', p. 86–87

W.E. Schricker's private bank

Private banks are banks owned by either the individual or a general Partner (business rank), partner(s) with limited partner(s). Private banks are not incorporation (business), incorporated. In any such case, creditors can look to both the "enti ...

in La Conner failed in 1912 with $378,766.91 in debts and less than $200,000 in assets. Schricker blamed Furth and other officers of Furth's bank; Furth was arrested, lampooned in the press, and convicted by a jury on April 18, 1913, and fined $10,000. Schricker accused Furth of recommending that he continue to take deposits even after he knew his bank was in trouble. The prosecutor amplified this with a charge that Furth had done so to keep Schricker's bank going just long enough to pay notes due to Furth's bank, thereby harming other depositors. However, Furth was unaware that Schricker had made $348,554.83 in self-dealing loans to the Fidalgo Lumber Company of Anacortes, Washington

Anacortes ( ) is a city in Skagit County, Washington, United States. The name "Anacortes" is an adaptation of the name of Anne Curtis Bowman, who was the wife of early Fidalgo Island settler Amos Bowman.Rainier Club

The Rainier Club is a private club in Seattle, Washington; it has been referred to as "Seattle's preeminent private club."Priscilla LongGentlemen organize Seattle's Rainier Club on February 23, 1888 HistoryLink.org, January 27, 2001. Accessed onli ...

and the Seattle Chamber of Commerce

The Seattle Metropolitan Chamber of Commerce is a private, membership-based organization that represents economic development and the economic interests of its corporate members in the metro region of Seattle, Washington. Its members include most ...

. He was a two-term president of the Chamber. He served as a Republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

on the Seattle City Council

The Seattle City Council is the legislative body of the city of Seattle, Washington. The Council consists of nine members serving four-year terms, seven of which are elected by electoral districts and two of which are elected in citywide at-lar ...

from 1885 until 1891. In 1901 he was the key organizer of Seattle's anti-union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

Citizens' Alliance.Richard C. Berner, ''Seattle 1900-1920: From Boomtown, Urban Turbulence, to Restoration'', Seattle: Charles Press, 1991, , p. 111.

He also played a key role in fundraising for the Alaska-Yukon-Pacific Exposition.

Marriage and family

In California, in 1865, Furth married Lucy (or Lucia) A. Dunton, a native ofIndiana

Indiana () is a U.S. state in the Midwestern United States. It is the 38th-largest by area and the 17th-most populous of the 50 States. Its capital and largest city is Indianapolis. Indiana was admitted to the United States as the 19th s ...

from what Lee Micklin characterizes as "an early American family"; they eventually had three daughters: Jane E., Anna F., and Sidonia. In 1884, Lucy Furth, along with Babette Gatzert (wife of Bailey Gatzert

Bailey Gatzert (December 29, 1829 – April 19, 1893) was an American politician and the eighth mayor of Seattle, Washington, serving from 1875 to 1876. He was the first Jewish mayor of Seattle, narrowly missing being the first Jewish mayor of ...

, and herself born a member of the Schwabacher family) founded the Ladies Relief Society (now Seattle Children's Home). It was Seattle's first charity.

Although he married a Gentile

Gentile () is a word that usually means "someone who is not a Jew". Other groups that claim Israelite heritage, notably Mormons, sometimes use the term ''gentile'' to describe outsiders. More rarely, the term is generally used as a synonym for ...

, Furth remained a practicing Jew. He belonged to the "quasi-reform" Ohaveth Sholum Congregation, Seattle's first synagogue, and later to the Reform

Reform ( lat, reformo) means the improvement or amendment of what is wrong, corrupt, unsatisfactory, etc. The use of the word in this way emerges in the late 18th century and is believed to originate from Christopher Wyvill#The Yorkshire Associati ...

Temple de Hirsch, one of the congregations that merged into the present-day Temple de Hirsch-Sinai

Temple De Hirsch Sinai is a Reform Jewish congregation with campuses in Seattle and nearby Bellevue, Washington, USA. It was formed as a 1971 merger between the earlier Temple De Hirsch (Seattle, founded 1899) and Temple Sinai (Bellevue, founded ...

.

Furth's daughter Jane married E.L. Terry. Anna married Frederick K. Struve, a Seattle financier and son of Seattle mayor Henry G. Struve. His daughter Sidonia married a U.S. Army colonel named Wetherill; the Wetherills inherited the Furth family summer estate at Yarrow Point on the east shore of Lake Washington. The bulk of this estate, was deeded to the towns of Yarrow Point and Hunts Point as the Wetherill Nature Preserve on July 4, 1988.Suzanne KnaussYarrow Point -- Thumbnail History

June 30, 2003. HistoryLink, Accessed online 2009-10-07.

References

{{DEFAULTSORT:Furth, Jacob 1840 births 1914 deaths People from Švihov (Klatovy District) American bankers Austro-Hungarian emigrants to the United States Seattle City Council members Washington (state) Republicans American people of Czech-Jewish descent 19th-century American politicians People from Colusa, California People from King County, Washington 19th-century American businesspeople