Islam in Somalia on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Practitioners of Islam first entered

/ref> Practicing Islam reinforces distinctions that further set Somalis apart from their immediate neighbors. Sunnism is the strand practiced by 90% of the population. Although Pew Research Center has not conducted a survey in Somalia, its Somali-majority northwestern neighbour Djibouti reported a creed breakdown of Muslims which was reported as 77% adhering to Sunnism, 8% as

Islam was introduced to the northern Somali coast early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the

Islam was introduced to the northern Somali coast early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the

The 1961 constitution guaranteed freedom of religion but also declared the newly independent republic an

The 1961 constitution guaranteed freedom of religion but also declared the newly independent republic an  When the Three-Year Plan, 1971–1973, was launched in January 1971, SRC leaders felt compelled to win the support of religious leaders so as to transform the existing social structure. On September 4, 1971, Siad Barre exhorted more than 100 religious teachers to participate in building a new socialist society. He criticized their method of teaching in

When the Three-Year Plan, 1971–1973, was launched in January 1971, SRC leaders felt compelled to win the support of religious leaders so as to transform the existing social structure. On September 4, 1971, Siad Barre exhorted more than 100 religious teachers to participate in building a new socialist society. He criticized their method of teaching in  Religious orders always have played a significant role in Somali Islam. The rise of these orders ( Tarika, "way" or "path") was connected with the development of

Religious orders always have played a significant role in Somali Islam. The rise of these orders ( Tarika, "way" or "path") was connected with the development of  Dervishes wandered from place to place teaching. They are best known for their ceremonies, called dhikr, in which states of visionary ecstasy are induced by group- chanting of religious texts and by rhythmic gestures, dancing, and deep breathing. The object is to free oneself from the body and to be lifted into the presence of God. Dervishes have been important as founders of agricultural religious communities called ''jamaat'' (singular jamaa). A few of these were home to celibate men only, but usually the jamaat were inhabited by families. Most Somalis were nominal members of Sufi orders.

Dervishes wandered from place to place teaching. They are best known for their ceremonies, called dhikr, in which states of visionary ecstasy are induced by group- chanting of religious texts and by rhythmic gestures, dancing, and deep breathing. The object is to free oneself from the body and to be lifted into the presence of God. Dervishes have been important as founders of agricultural religious communities called ''jamaat'' (singular jamaa). A few of these were home to celibate men only, but usually the jamaat were inhabited by families. Most Somalis were nominal members of Sufi orders.

Local leaders of brotherhoods customarily asked lineage heads in the areas where they wished to settle for permission to build their mosques and communities. A piece of land was usually freely given; often it was an area between two clans or one in which nomads had access to a river. The presence of a jama'ah not only provided a buffer zone between two hostile groups, but also caused the giver to acquire a blessing since the land was considered given to God. Tenure was a matter of charity only, however, and sometimes became precarious in case of disagreements. No statistics were available in 1990 on the number of such settlements, but in the 1950s there were more than ninety in the south, with a total of about 35,000 members. Most were in the

Local leaders of brotherhoods customarily asked lineage heads in the areas where they wished to settle for permission to build their mosques and communities. A piece of land was usually freely given; often it was an area between two clans or one in which nomads had access to a river. The presence of a jama'ah not only provided a buffer zone between two hostile groups, but also caused the giver to acquire a blessing since the land was considered given to God. Tenure was a matter of charity only, however, and sometimes became precarious in case of disagreements. No statistics were available in 1990 on the number of such settlements, but in the 1950s there were more than ninety in the south, with a total of about 35,000 members. Most were in the  Because of the saint's spiritual presence at his tomb, Sufi pilgrims journey there to pray for them and send blessings to them. Members of the saint's order also visit the tomb, particularly on the anniversaries of his birth and death. Leaders of Sufi orders and their branches and of specific congregations are said to have ''baraka'', a state of blessedness implying an inner spiritual power that is inherent in the religious office, and may cling to the tomb of a revered leader, who, upon death, is considered a pious Muslim. However, some religious leaders are venerated by Sufis because of their religious reputations, whether or not they were associated with an order or one of its communities. Sainthood also has been ascribed to other Sufis because of their status as founders of clans or large lineages. Northern pastoral nomads are likely to honor lineage founders as saints; sedentary Somalis revere saints for their piety and baraka.

The traditional learning of a wadaad includes a form of folk astronomy based on stellar movements and related to seasonal changes. Its primary objective is to signal the times for migration, but it may also be used to set the dates of rituals that are specifically Somali. This folk knowledge is also used in ritual methods of healing and averting misfortune, as well as for divination.

Because of the saint's spiritual presence at his tomb, Sufi pilgrims journey there to pray for them and send blessings to them. Members of the saint's order also visit the tomb, particularly on the anniversaries of his birth and death. Leaders of Sufi orders and their branches and of specific congregations are said to have ''baraka'', a state of blessedness implying an inner spiritual power that is inherent in the religious office, and may cling to the tomb of a revered leader, who, upon death, is considered a pious Muslim. However, some religious leaders are venerated by Sufis because of their religious reputations, whether or not they were associated with an order or one of its communities. Sainthood also has been ascribed to other Sufis because of their status as founders of clans or large lineages. Northern pastoral nomads are likely to honor lineage founders as saints; sedentary Somalis revere saints for their piety and baraka.

The traditional learning of a wadaad includes a form of folk astronomy based on stellar movements and related to seasonal changes. Its primary objective is to signal the times for migration, but it may also be used to set the dates of rituals that are specifically Somali. This folk knowledge is also used in ritual methods of healing and averting misfortune, as well as for divination.

Wadaddo help avert misfortune by making protective amulets and charms that transmit some of their baraka to others, or by adding the Qur'an's baraka to the amulet through a written passage. The baraka of a saint may be obtained in the form of an object that has touched or been placed near his tomb.

Although wadaddo may use their power to curse as a sanction, misfortune generally is not attributed to curses or witchcraft. Somalis have accepted the orthodox Muslim view that a man's conduct will be judged in an afterlife. However, a person who commits an antisocial act, such as

Wadaddo help avert misfortune by making protective amulets and charms that transmit some of their baraka to others, or by adding the Qur'an's baraka to the amulet through a written passage. The baraka of a saint may be obtained in the form of an object that has touched or been placed near his tomb.

Although wadaddo may use their power to curse as a sanction, misfortune generally is not attributed to curses or witchcraft. Somalis have accepted the orthodox Muslim view that a man's conduct will be judged in an afterlife. However, a person who commits an antisocial act, such as

''Djibouti Journal''; Somalia's 'Hebrews' See a Better Day"

'' The New York Times''. August 15th, 2000.

/ref>

Somali Qadiriya (Somali language)

{{Somalia topics

Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...

in the northwestern city of Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bibl ...

during Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

's lifetime whereupon they built the Masjid al-Qiblatayn

The Masjid al-Qiblatayn ( ar, مسجد القبلتين, lit=Mosque of the Two Qiblas), also spelt Masjid al-Qiblatain, is a mosque in Medina believed by Muslims to be the place where the final Islamic prophet, Muhammad, received the command to ...

; as such, Islam has been a part of Somali society

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the Horn of Africa who share a common ancestry, culture and history. The Lowland East Cushitic Somali language is the shared mo ...

for 14 centuries.A Country Study: Somalia from The Library of Congress/ref> Practicing Islam reinforces distinctions that further set Somalis apart from their immediate neighbors. Sunnism is the strand practiced by 90% of the population. Although Pew Research Center has not conducted a survey in Somalia, its Somali-majority northwestern neighbour Djibouti reported a creed breakdown of Muslims which was reported as 77% adhering to Sunnism, 8% as

non-denominational Muslim

Non-denominational Muslims () are Muslims who do not belong to, do not self-identify with, or cannot be readily classified under one of the identifiable Islamic schools and branches.

Non-denominational Muslims are found primarily in Central Asi ...

, 2% as Shia

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, mo ...

, thirteen percent refusing to answer, and a further report inclusive of Somali Region

The Somali Region ( so, Deegaanka Soomaalida, am, ሱማሌ ክልል, Sumalē Kilil, ar, المنطقة الصومالية), also known as Soomaali Galbeed (''Western Somalia'') and officially the Somali Regional State, is a regional stat ...

stipulating 2% adherence to a minority sect (e.g. Ibadism

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years after the Islamic prophet Muhammad's death in 632 AD as a moderate sc ...

, Quranism

Quranism ( ar, القرآنية, translit=al-Qurʾāniyya'';'' also known as Quran-only Islam) Brown, ''Rethinking tradition in modern Islamic thought'', 1996: p.38-42 is a movement within Islam. It holds the belief that traditional religious cl ...

etc.).

The role of religious functionaries began to shrink in the 1950s and 1960s as some of their legal and educational powers and responsibilities were transferred to secular authorities. The position of religious leaders changed substantially after the 1969 revolution and the introduction of scientific socialism

Scientific socialism is a term coined in 1840 by Pierre-Joseph Proudhon in his book '' What is Property?'' to mean a society ruled by a scientific government, i.e., one whose sovereignty rests upon reason, rather than sheer will: Thus, in a given ...

. Siad Barre insisted that his version of socialism was compatible with Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

ic principles, and he condemned atheism. Religious leaders, however, were warned not to meddle in politics.

History

Birth of Islam and Middle Ages

Islam was introduced to the northern Somali coast early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the

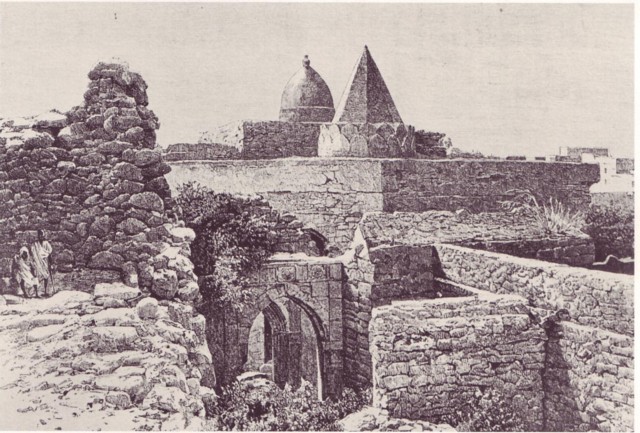

Islam was introduced to the northern Somali coast early on from the Arabian peninsula, shortly after the hijra

Hijra, Hijrah, Hegira, Hejira, Hijrat or Hijri may refer to:

Islam

* Hijrah (often written as ''Hejira'' in older texts), the migration of Muhammad from Mecca to Medina in 622 CE

* Migration to Abyssinia or First Hegira, of Muhammad's followers ...

. Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bibl ...

's two-mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla w ...

Masjid al-Qiblatayn

The Masjid al-Qiblatayn ( ar, مسجد القبلتين, lit=Mosque of the Two Qiblas), also spelt Masjid al-Qiblatain, is a mosque in Medina believed by Muslims to be the place where the final Islamic prophet, Muhammad, received the command to ...

dates to the 7th century, and is the oldest mosque

A mosque (; from ar, مَسْجِد, masjid, ; literally "place of ritual prostration"), also called masjid, is a place of prayer for Muslims. Mosques are usually covered buildings, but can be any place where prayers ( sujud) are performed, ...

in the city. Somalis

The Somalis ( so, Soomaalida 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒆𐒖, ar, صوماليون) are an ethnic group native to the Horn of Africa who share a common ancestry, culture and history. The Lowland East Cushitic Somali language is the shared ...

were among the earliest non-Arabs to convert to Islam. Not only the earliest non-Arabs, but the religion of Islam in Somali predates almost every single Muslim nation of today. In the late 9th century, Al-Yaqubi

ʾAbū l-ʿAbbās ʾAḥmad bin ʾAbī Yaʿqūb bin Ǧaʿfar bin Wahb bin Waḍīḥ al-Yaʿqūbī (died 897/8), commonly referred to simply by his nisba al-Yaʿqūbī, was an Arab Muslim geographer and perhaps the first historian of world cult ...

wrote that Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

s were living along the northern Somali seaboard. He also mentioned that the Adal kingdom had its capital in the city, suggesting that the Adal Sultanate with Zeila as its headquarters dates back to at least the 9th or 10th century. According to I.M. Lewis, the polity was governed by local Somali dynasties

A dynasty is a sequence of rulers from the same family,''Oxford English Dictionary'', "dynasty, ''n''." Oxford University Press (Oxford), 1897. usually in the context of a monarchical system, but sometimes also appearing in republics. A d ...

, who also ruled over the similarly-established Sultanate of Mogadishu

The Sultanate of Mogadishu ( so, Saldanadda Muqdisho, ar, سلطنة مقديشو) (fl.9th- 13th centuries), also known as the Kingdom of Magadazo, was a medieval Somali sultanate centered in southern Somalia. It rose as one of the pre-eminent po ...

in the littoral Benadir region to the south. Adal's history from this founding period forth would be characterized by a succession of battles with neighboring Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

.

In 1332, the Zeila-based King of Adal was slain in a military campaign aimed at halting the Abyssinian Emperor

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereignty, sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife (empress consort), ...

Amda Seyon I

Amda Seyon I ( gez, ዐምደ ፡ ጽዮን , am, አምደ ፅዮን , "Pillar of Zion"), throne name Gebre Mesqel (ገብረ መስቀል ) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1314 to 1344 and a member of the Solomonic dynasty.

He is best known ...

's march toward the city to avenge the slaughtered Christians including a famous monk sent to wage peace and destroyed Churches by the Adalites. When the last Sultan of Ifat, Sa'ad ad-Din II

Sa'ad ad-Din II ( ar, سعد الدين زنكي), reigned – c. 1403 or c. 1414, was a Sultan of the Ifat Sultanate. He was the brother of Haqq ad-Din II, and the father of Mansur ad-Din, Sabr ad-Din II and Badlay ibn Sa'ad ad-Din. The hist ...

, was also killed by Emperor Dawit I

Dawit I ( gez, ዳዊት) was Emperor of Ethiopia from 1382 to 6 October 1413, and a member of the Solomonic dynasty. He was the younger son of Newaya Krestos.

Reign

Taddesse Tamrat discusses a tradition that early in his reign, Dawit campaign ...

in Zeila in 1410, his children escaped to Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the Saudi Arabia–Yemen border, north and ...

, before later returning in 1415. In the early 15th century, Adal's capital was moved further inland to the town of Dakkar

Dakkar or Doggor, also known as Aw-Barkhadle () was a historical town located near Hargeisa in modern-day Somaliland. It was part of the Muslim empires in the Horn of Africa during the middle ages and served as the capital of the Adal Sultanate ...

, where Sabr ad-Din II

Sabr ad-Din III ( ar, الصبر الدين الثاني) (died 1422 or 1423) was a Sultan of Adal and the oldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II. Sabr ad-Din returned to the Horn of Africa from Yemen to reclaim his father's realm. He defeated the Ethiop ...

, the eldest son of Sa'ad ad-Din II, established a new base after his return from Yemen.

Adal's headquarters were again relocated the following century, this time to Harar

Harar ( amh, ሐረር; Harari: ሀረር; om, Adare Biyyo; so, Herer; ar, هرر) known historically by the indigenous as Gey (Harari: ጌይ ''Gēy'', ) is a walled city in eastern Ethiopia. It is also known in Arabic as the City of Saint ...

. From this new capital, Adal organized an effective army led by Imam

Imam (; ar, إمام '; plural: ') is an Islamic leadership position. For Sunni Muslims, Imam is most commonly used as the title of a worship leader of a mosque. In this context, imams may lead Islamic worship services, lead prayers, ser ...

Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi

Ahmad ibn Ibrahim al-Ghazi ( so, Axmed Ibraahim al-Qaasi or Axmed Gurey, Harari: አሕመድ ኢብራሂም አል-ጋዚ, ar, أحمد بن إبراهيم الغازي ; 1506 – 21 February 1543) was an imam and general of the Adal Sultana ...

(Ahmad "Gurey" or "Gran") that invaded the Abyssinian empire. This 16th century campaign is historically known as the Conquest of Abyssinia (''Futuh al-Habash''). During the war, Imam Ahmad pioneered the use of cannon

A cannon is a large- caliber gun classified as a type of artillery, which usually launches a projectile using explosive chemical propellant. Gunpowder ("black powder") was the primary propellant before the invention of smokeless powder ...

s and firearms

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes c ...

supplied by the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

, which he imported through Zeila and thousands of mercenaries from the Muslim world and nomadic Somalia to wage a 'holy war' against Ethiopian King of Kings. The few Portuguese

Portuguese may refer to:

* anything of, from, or related to the country and nation of Portugal

** Portuguese cuisine, traditional foods

** Portuguese language, a Romance language

*** Portuguese dialects, variants of the Portuguese language

** Portu ...

under Cristóvão da Gama

Cristóvão da Gama ( 1516 – 29 August 1542), anglicised as Christopher da Gama, was a Portuguese military commander who led a Portuguese army of 400 musketeers on a crusade in Ethiopia (1541–1543) against the Adal Muslim army of Imam Ahmad ...

that later that came to assist their Ethoipian coreligionist would tip the scale in their favour.I.M. Lewis, ''A pastoral democracy: a study of pastoralism and politics among the Northern Somali of the Horn of Africa'', (LIT Verlag Münster: 1999), p.17 Some scholars argue that this conflict proved, through their use on both sides, the value of firearm

A firearm is any type of gun designed to be readily carried and used by an individual. The term is legally defined further in different countries (see Legal definitions).

The first firearms originated in 10th-century China, when bamboo tubes ...

s like the matchlock

A matchlock or firelock is a historical type of firearm wherein the gunpowder is ignited by a burning piece of rope that is touched to the gunpowder by a mechanism that the musketeer activates by pulling a lever or trigger with his finger. Before ...

musket

A musket is a muzzle-loaded long gun that appeared as a smoothbore weapon in the early 16th century, at first as a heavier variant of the arquebus, capable of penetrating plate armour. By the mid-16th century, this type of musket gradually d ...

, cannons and the arquebus

An arquebus ( ) is a form of long gun that appeared in Europe and the Ottoman Empire during the 15th century. An infantryman armed with an arquebus is called an arquebusier.

Although the term ''arquebus'', derived from the Dutch word ''Haakbus ...

over traditional weapons.

During the Age of the Ajuran, the sultanates and republics of Merca

Merca ( so, Marka, Maay Maay, Maay: ''Marky'', ar, مركة) is a historic port city in the southern Lower Shebelle province of Somalia. It is located approximately to the southwest of the nation's capital Mogadishu. Merca is the traditional home ...

, Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port ...

, Barawa

Barawa ( so, Baraawe, Maay Maay, Maay: ''Barawy'', ar, ﺑﺮﺍﻭة ''Barāwa''), also known as Barawe and Brava, is the capital city, capital of the South West State of Somalia, South West State of Somalia.Pelizzari, Elisa. "Guerre civile et ...

, Hobyo

Hobyo (; so, Hobyo), is an ancient port city in Galmudug state in the north-central Mudug region of Somalia.

Hobyo was founded as a coastal outpost by the Ajuran Empire during the 13th century.Lee V. Cassanelli, ''The shaping of Somali society: ...

flourished and had a lucrative foreign commerce, with ships sailing to and coming from Arabia

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate. ...

, India

India, officially the Republic of India (Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the so ...

, Venetia, Persia

Iran, officially the Islamic Republic of Iran, and also called Persia, is a country located in Western Asia. It is bordered by Iraq and Turkey to the west, by Azerbaijan and Armenia to the northwest, by the Caspian Sea and Turkmeni ...

, Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, Portugal

Portugal, officially the Portuguese Republic ( pt, República Portuguesa, links=yes ), is a country whose mainland is located on the Iberian Peninsula of Southwestern Europe, and whose territory also includes the Atlantic archipelagos of ...

and as far away as China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. Vasco da Gama

Vasco da Gama, 1st Count of Vidigueira (; ; c. 1460s – 24 December 1524), was a Portuguese explorer and the first European to reach India by sea.

His initial voyage to India by way of Cape of Good Hope (1497–1499) was the first to link E ...

, who passed by Mogadishu in the 15th century, noted that it was a large city with houses several storeys high and large palaces in its center, in addition to many mosques with cylindrical minaret

A minaret (; ar, منارة, translit=manāra, or ar, مِئْذَنة, translit=miʾḏana, links=no; tr, minare; fa, گلدسته, translit=goldaste) is a type of tower typically built into or adjacent to mosques. Minarets are generall ...

s.

The city of Mogadishu came to be known as the ''City of Islam'', and controlled the East African gold trade for several centuries. In the 16th century, Duarte Barbosa

Duarte Barbosa (c. 14801 May 1521) was a Portuguese writer and officer from Portuguese India (between 1500 and 1516). He was a Christian pastor and scrivener in a ''feitoria'' in Kochi, and an interpreter of the local language, Malayalam. Barbosa ...

noted that many ships from the Kingdom of Cambaya in modern-day India sailed to Mogadishu with cloth

Textile is an umbrella term that includes various fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, filaments, threads, different fabric types, etc. At first, the word "textiles" only referred to woven fabrics. However, weaving is not the ...

and spice

A spice is a seed, fruit, root, bark, or other plant substance primarily used for flavoring or coloring food. Spices are distinguished from herbs, which are the leaves, flowers, or stems of plants used for flavoring or as a garnish. Spices a ...

s, for which they in return received gold

Gold is a chemical element with the symbol Au (from la, aurum) and atomic number 79. This makes it one of the higher atomic number elements that occur naturally. It is a bright, slightly orange-yellow, dense, soft, malleable, and ductile met ...

, wax

Waxes are a diverse class of organic compounds that are lipophilic, malleable solids near ambient temperatures. They include higher alkanes and lipids, typically with melting points above about 40 °C (104 °F), melting to giv ...

and ivory

Ivory is a hard, white material from the tusks (traditionally from elephants) and teeth of animals, that consists mainly of dentine, one of the physical structures of teeth and tusks. The chemical structure of the teeth and tusks of mammals is ...

. Barbosa also highlighted the abundance of meat

Meat is animal flesh that is eaten as food. Humans have hunted, farmed, and scavenged animals for meat since prehistoric times. The establishment of settlements in the Neolithic Revolution allowed the domestication of animals such as chic ...

, wheat

Wheat is a grass widely cultivated for its seed, a cereal grain that is a worldwide staple food. The many species of wheat together make up the genus ''Triticum'' ; the most widely grown is common wheat (''T. aestivum''). The archaeologi ...

, barley

Barley (''Hordeum vulgare''), a member of the grass family, is a major cereal grain grown in temperate climates globally. It was one of the first cultivated grains, particularly in Eurasia as early as 10,000 years ago. Globally 70% of barley pr ...

, horse

The horse (''Equus ferus caballus'') is a domesticated, one-toed, hoofed mammal. It belongs to the taxonomic family Equidae and is one of two extant subspecies of ''Equus ferus''. The horse has evolved over the past 45 to 55 million y ...

s, and fruit

In botany, a fruit is the seed-bearing structure in flowering plants that is formed from the ovary after flowering.

Fruits are the means by which flowering plants (also known as angiosperms) disseminate their seeds. Edible fruits in particu ...

on the coastal markets, which generated enormous wealth for the merchants. Mogadishu was also the center of a thriving textile industry known as ''toob benadir'', specialized for the markets in Egypt, among other places.

Modern era

Because Muslims believe that their faith was revealed in its complete form toMuhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the mo ...

, Bidʻah

In Islam, bid'ah ( ar, بدعة; en, innovation) refers to innovation in religious matters. Linguistically, the term means "innovation, novelty, heretical doctrine, heresy".

In classical Arabic literature ('' adab''), it has been used as a fo ...

, is seen as a major sin. One response was to stress a return to orthodox Muslim traditions and to oppose Westernization

Westernization (or Westernisation), also Europeanisation or occidentalization (from the ''Occident''), is a process whereby societies come under or adopt Western culture in areas such as industry, technology, science, education, politics, economi ...

totally. The Sufi brotherhoods were at the forefront of this movement, personified in Somalia by Mohammed Abdullah Hassan

Sayid Mohamed Abdullahi Hassan ( so, Sayid Maxamed Cabdulle Xasan; 1856–1920) was a Somali religious and military leader of the Dervish movement, which led a two-decade long confrontation with various colonial empires including the British, ...

in the early 20th century. Generally, the leaders of Islamic orders opposed the spread of Western education.

Another response was to reform Islam by reinterpreting it. From this perspective, early Islam was seen as a protest against abuse, corruption, and inequality; reformers therefore attempted to prove that Muslim scriptures contained all elements needed to deal with modernization. To this school of thought belongs Islamic socialism

Islamic socialism is a political philosophy that incorporates Islamic principles into socialism. As a term, it was coined by various Muslim leaders to describe a more spiritual form of socialism. Islamic socialists believe that the teachin ...

, identified particularly with Egyptian nationalist Gamal Abdul Nasser

Gamal Abdel Nasser Hussein, . (15 January 1918 – 28 September 1970) was an Egyptian politician who served as the second president of Egypt from 1954 until his death in 1970. Nasser led the Egyptian revolution of 1952 and introduced far-re ...

. His ideas appealed to a number of Somalis, especially those who had studied in Cairo

Cairo ( ; ar, القاهرة, al-Qāhirah, ) is the capital of Egypt and its largest city, home to 10 million people. It is also part of the largest urban agglomeration in Africa, the Arab world and the Middle East: The Greater Cairo metro ...

in the 1950s and 1960s.

The 1961 constitution guaranteed freedom of religion but also declared the newly independent republic an

The 1961 constitution guaranteed freedom of religion but also declared the newly independent republic an Islamic state

An Islamic state is a State (polity), state that has a form of government based on sharia, Islamic law (sharia). As a term, it has been used to describe various historical Polity, polities and theories of governance in the Islamic world. As a t ...

. The first two post-independence governments paid lip service to the principles of Islamic socialism but made relatively few changes. The coup of October 21, 1969, installed a radical regime committed to profound change. Shortly afterward, Stella d'Ottobre, the official newspaper of the Supreme Revolutionary Council ( SRC), published an editorial about relations between Islam and socialism and the differences between scientific and Islamic socialism. Islamic socialism was said to have become a servant of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for Profit (economics), profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, pric ...

and neocolonialism

Neocolonialism is the continuation or reimposition of imperialist rule by a state (usually, a former colonial power) over another nominally independent state (usually, a former colony). Neocolonialism takes the form of economic imperialism, gl ...

and a tool manipulated by a privileged, rich, and powerful class. In contrast, scientific socialism was based on the altruistic values that inspired genuine Islam. Religious leaders should therefore leave secular affairs to the new leaders who were striving for goals that conformed with Islamic principles. Soon after, the government arrested several protesting religious leaders and accused them of counterrevolutionary propaganda and of conniving with reactionary elements in the Arabian Peninsula

The Arabian Peninsula, (; ar, شِبْهُ الْجَزِيرَةِ الْعَرَبِيَّة, , "Arabian Peninsula" or , , "Island of the Arabs") or Arabia, is a peninsula of Western Asia, situated northeast of Africa on the Arabian Plate ...

. The authorities also dismissed several members of religious tribunals for corruption and incompetence.

When the Three-Year Plan, 1971–1973, was launched in January 1971, SRC leaders felt compelled to win the support of religious leaders so as to transform the existing social structure. On September 4, 1971, Siad Barre exhorted more than 100 religious teachers to participate in building a new socialist society. He criticized their method of teaching in

When the Three-Year Plan, 1971–1973, was launched in January 1971, SRC leaders felt compelled to win the support of religious leaders so as to transform the existing social structure. On September 4, 1971, Siad Barre exhorted more than 100 religious teachers to participate in building a new socialist society. He criticized their method of teaching in Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , s ...

ic schools and charged some with using religion for personal profit.

The campaign for scientific socialism intensified in 1972. On the occasion of Eid al-Adha

Eid al-Adha () is the second and the larger of the two main holidays celebrated in Islam (the other being Eid al-Fitr). It honours the willingness of Ibrahim (Abraham) to sacrifice his son Ismail (Ishmael) as an act of obedience to Allah's co ...

, the major Muslim festival associated with the pilgrimage, the president defined scientific socialism as half practical work and half ideological belief. He declared that work and belief were compatible with Islam because the Qur'an condemned exploitation and money lending and urged compassion, unity, and cooperation among Muslims. But he stressed the distinction between religion as an ideological instrument for the manipulation of power and as a moral force. He condemned the antireligious attitude of Marxist

Marxism is a Left-wing politics, left-wing to Far-left politics, far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a Materialism, materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand S ...

s. Religion, Siad Barre said, was an integral part of the Somali worldview, but it belonged in the private sphere, whereas scientific socialism dealt with material concerns such as poverty. Religious leaders should exercise their moral influence but refrain from interfering in political or economic matters.

Religious orders always have played a significant role in Somali Islam. The rise of these orders ( Tarika, "way" or "path") was connected with the development of

Religious orders always have played a significant role in Somali Islam. The rise of these orders ( Tarika, "way" or "path") was connected with the development of Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

, a mystical sect within Islam that began during the 9th and 10th centuries and reached its height during the 12th and 13th. In Somalia, Sufi orders appeared in towns during the 15th century and rapidly became a revitalizing force. Followers of Sufism seek a closer personal relationship to God through special spiritual disciplines. Escape from self is facilitated by poverty, seclusion, and other forms of self-denial. Members of Sufi orders are commonly called dervish

Dervish, Darvesh, or Darwīsh (from fa, درویش, ''Darvīsh'') in Islam can refer broadly to members of a Sufi fraternity

A fraternity (from Latin language, Latin ''wiktionary:frater, frater'': "brother (Christian), brother"; whence, ...

es, from the Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

''daraawish'' (singular darwish, "one who gave up worldly concerns to dedicate himself to the service of God

In monotheism, monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator deity, creator, and principal object of Faith#Religious views, faith.Richard Swinburne, Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Ted Honderich, Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Ox ...

and community"). Leaders of branches or congregations of these orders are given the Arabic title ''shaykh'', a term usually reserved for those learned in Islam and rarely applied to ordinary ''wadaads'' (holy men).

Dervishes wandered from place to place teaching. They are best known for their ceremonies, called dhikr, in which states of visionary ecstasy are induced by group- chanting of religious texts and by rhythmic gestures, dancing, and deep breathing. The object is to free oneself from the body and to be lifted into the presence of God. Dervishes have been important as founders of agricultural religious communities called ''jamaat'' (singular jamaa). A few of these were home to celibate men only, but usually the jamaat were inhabited by families. Most Somalis were nominal members of Sufi orders.

Dervishes wandered from place to place teaching. They are best known for their ceremonies, called dhikr, in which states of visionary ecstasy are induced by group- chanting of religious texts and by rhythmic gestures, dancing, and deep breathing. The object is to free oneself from the body and to be lifted into the presence of God. Dervishes have been important as founders of agricultural religious communities called ''jamaat'' (singular jamaa). A few of these were home to celibate men only, but usually the jamaat were inhabited by families. Most Somalis were nominal members of Sufi orders.

Local leaders of brotherhoods customarily asked lineage heads in the areas where they wished to settle for permission to build their mosques and communities. A piece of land was usually freely given; often it was an area between two clans or one in which nomads had access to a river. The presence of a jama'ah not only provided a buffer zone between two hostile groups, but also caused the giver to acquire a blessing since the land was considered given to God. Tenure was a matter of charity only, however, and sometimes became precarious in case of disagreements. No statistics were available in 1990 on the number of such settlements, but in the 1950s there were more than ninety in the south, with a total of about 35,000 members. Most were in the

Local leaders of brotherhoods customarily asked lineage heads in the areas where they wished to settle for permission to build their mosques and communities. A piece of land was usually freely given; often it was an area between two clans or one in which nomads had access to a river. The presence of a jama'ah not only provided a buffer zone between two hostile groups, but also caused the giver to acquire a blessing since the land was considered given to God. Tenure was a matter of charity only, however, and sometimes became precarious in case of disagreements. No statistics were available in 1990 on the number of such settlements, but in the 1950s there were more than ninety in the south, with a total of about 35,000 members. Most were in the Bakool

Bakool ( so, Bakool, Maay: ''Bokool'', ar, بكول) is a region ('' gobol'') in southwestern Somalia.

Overview

It is bordered by the Somali regions of Hiiraan, Bay and Gedo.

Bakool, like Gedo and Bay, as well as most parts of the Jubbada Dhe ...

, Gedo

Gedo ( so, Gedo, Maay: ''Gethy'', ar, جيذو, it, Ghedo or ''Ghedu'') is an administrative region ('' gobol'') in Jubaland, southern Somalia. Its regional capital is Garbahaarreey. It was created in 1974 and is bordered by the Ogaden in E ...

, and Bay regions or along the middle and lower Shabele River. There were few jamaat in other regions because the climate and soil did not encourage agricultural settlements.

Membership in a brotherhood is theoretically a voluntary matter unrelated to kinship. However, lineages are often affiliated with a specific brotherhood and a man usually joins his father's order. Initiation is followed by a ceremony during which the order's dhikr is celebrated. Novices swear to accept the branch head as their spiritual guide.

Each order has its own hierarchy that is supposedly a substitute for the kin group from which the members have separated themselves. Veneration is given to previous heads of the order, known as the Chain of Blessing, rather than to ancestors. This practice is especially followed in the south, where place of residence tends to have more significance than lineage.

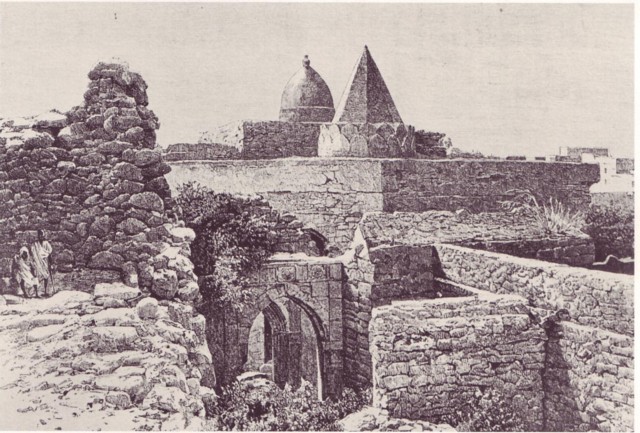

Because of the saint's spiritual presence at his tomb, Sufi pilgrims journey there to pray for them and send blessings to them. Members of the saint's order also visit the tomb, particularly on the anniversaries of his birth and death. Leaders of Sufi orders and their branches and of specific congregations are said to have ''baraka'', a state of blessedness implying an inner spiritual power that is inherent in the religious office, and may cling to the tomb of a revered leader, who, upon death, is considered a pious Muslim. However, some religious leaders are venerated by Sufis because of their religious reputations, whether or not they were associated with an order or one of its communities. Sainthood also has been ascribed to other Sufis because of their status as founders of clans or large lineages. Northern pastoral nomads are likely to honor lineage founders as saints; sedentary Somalis revere saints for their piety and baraka.

The traditional learning of a wadaad includes a form of folk astronomy based on stellar movements and related to seasonal changes. Its primary objective is to signal the times for migration, but it may also be used to set the dates of rituals that are specifically Somali. This folk knowledge is also used in ritual methods of healing and averting misfortune, as well as for divination.

Because of the saint's spiritual presence at his tomb, Sufi pilgrims journey there to pray for them and send blessings to them. Members of the saint's order also visit the tomb, particularly on the anniversaries of his birth and death. Leaders of Sufi orders and their branches and of specific congregations are said to have ''baraka'', a state of blessedness implying an inner spiritual power that is inherent in the religious office, and may cling to the tomb of a revered leader, who, upon death, is considered a pious Muslim. However, some religious leaders are venerated by Sufis because of their religious reputations, whether or not they were associated with an order or one of its communities. Sainthood also has been ascribed to other Sufis because of their status as founders of clans or large lineages. Northern pastoral nomads are likely to honor lineage founders as saints; sedentary Somalis revere saints for their piety and baraka.

The traditional learning of a wadaad includes a form of folk astronomy based on stellar movements and related to seasonal changes. Its primary objective is to signal the times for migration, but it may also be used to set the dates of rituals that are specifically Somali. This folk knowledge is also used in ritual methods of healing and averting misfortune, as well as for divination.

Wadaddo help avert misfortune by making protective amulets and charms that transmit some of their baraka to others, or by adding the Qur'an's baraka to the amulet through a written passage. The baraka of a saint may be obtained in the form of an object that has touched or been placed near his tomb.

Although wadaddo may use their power to curse as a sanction, misfortune generally is not attributed to curses or witchcraft. Somalis have accepted the orthodox Muslim view that a man's conduct will be judged in an afterlife. However, a person who commits an antisocial act, such as

Wadaddo help avert misfortune by making protective amulets and charms that transmit some of their baraka to others, or by adding the Qur'an's baraka to the amulet through a written passage. The baraka of a saint may be obtained in the form of an object that has touched or been placed near his tomb.

Although wadaddo may use their power to curse as a sanction, misfortune generally is not attributed to curses or witchcraft. Somalis have accepted the orthodox Muslim view that a man's conduct will be judged in an afterlife. However, a person who commits an antisocial act, such as patricide

Patricide is (i) the act of killing one's own father, or (ii) a person who kills their own father or stepfather. The word ''patricide'' derives from the Greek word ''pater'' (father) and the Latin suffix ''-cida'' (cutter or killer). Patricide ...

, is thought possessed of supernatural evil powers.

Like other Muslims, Somalis believe in jinn

Jinn ( ar, , ') – also Romanization of Arabic, romanized as djinn or Anglicization, anglicized as genies (with the broader meaning of spirit or demon, depending on sources)

– are Invisibility, invisible creatures in early Arabian mytho ...

. Certain kinds of illness, including tuberculosis

Tuberculosis (TB) is an infectious disease usually caused by '' Mycobacterium tuberculosis'' (MTB) bacteria. Tuberculosis generally affects the lungs, but it can also affect other parts of the body. Most infections show no symptoms, in ...

and pneumonia

Pneumonia is an inflammatory condition of the lung primarily affecting the small air sacs known as alveoli. Symptoms typically include some combination of productive or dry cough, chest pain, fever, and difficulty breathing. The severity ...

, or symptoms such as sneezing, coughing, vomiting, and loss of consciousness, are believed by some Somalis to result from spirit possession, namely, the Ifrit of the spirit world. The condition is treated by a shaykh, who reads portions of the Qur'an over the patient repeatedly.

Yibir

The Yibir, also referred to as the Yibbir, the Yebir, the Yahhar or the Yibro, derived from an Aramaic ‘iḇray' word which means Jews, are a caste of Somali people. They have traditionally been endogamous. Their hereditary occupations have been ...

clan members are popularly held to be descendants of Jewish

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

Hebrew

Hebrew (; ; ) is a Northwest Semitic language of the Afroasiatic language family. Historically, it is one of the spoken languages of the Israelites and their longest-surviving descendants, the Jews and Samaritans. It was largely preserved ...

forebears. The etymology of the word "Yibir" is also believed by some to have come from the word for "Hebrew". However, spokespersons for the Yibir have generally not tried to make their presence known to Jewish/Israeli authorities. Despite their putative Jewish origins, the overwhelming majority of the Yibir, like the Somali population in general, adhere to Islam and know practically nothing of Judaism.Fisher, Ian''Djibouti Journal''; Somalia's 'Hebrews' See a Better Day"

'' The New York Times''. August 15th, 2000.

/ref>

Denominations

Liberal Islam

In early January 1975, evoking the message of equality, justice, and social progress contained in the Qur'an, Siad Barre announced a new family law that gave women the right to inheritance on an equal basis with men. Some Somalis believe the law was proof that the SRC wanted to undermine the basic structure of Islamic society. In Mogadishu twenty-three religious leaders protested inside their mosques. They were arrested and charged with acting at the instigation of a foreign power and with violating state security; ten were executed. Sheikh Ahmed Sheikh Mohamed Walaaleeye and Sheikh Hassan Absiye Derie were among them. Most religious leaders, however, kept silent. The government continued to organize training courses for shaykhs in scientific socialism.Sunni

For generations, ''Islam in Somalia'' leaned towards theAsh'ari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the ...

yah theology, Shafi’i

The Shafii ( ar, شَافِعِي, translit=Shāfiʿī, also spelled Shafei) school, also known as Madhhab al-Shāfiʿī, is one of the four major traditional schools of religious law (madhhab) in the Sunnī branch of Islam. It was founded by ...

jurisprudence, and Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, r ...

, until recent decades when Salafism has made inroads. Influence of Islamic religious leaders has varied by region, being greater in the north than among some groups in the settled regions of the south. Among nomads, the exigencies of pastoral life gave greater weight to the warrior's role, and religious leaders were expected to remain aloof from political matters.

Sufism

Three Sufi orders were prominent in Somalia. In order of their introduction into the country, they were theQadiriyah

The Qadiriyya (), also transliterated Qādirīyah, ''Qadri'', ''Qadriya'', ''Kadri'', ''Elkadri'', ''Elkadry'', ''Aladray'', ''Alkadrie'', ''Adray'', ''Kadray'', ''Kadiri'', ''Qadiri'', ''Quadri'' or ''Qadri'' are members of the Sunni Qadiri ta ...

, the Idrisiyah, and the Salihiyya

Salihiyya ( so, Saalixiya; Urwayniya, ar, الصالحية) is a ''tariqa'' (order) of Sufi Islam prevalent in Somalia and the adjacent Somali region of Ethiopia. It was founded in the Sudan by Sayyid Muhammad Salih (1854-1919). The order is c ...

. The Rifaiyah, an offshoot of the Qadiriyah, was represented mainly among Arabs resident in Mogadishu

Mogadishu (, also ; so, Muqdisho or ; ar, مقديشو ; it, Mogadiscio ), locally known as Xamar or Hamar, is the capital and List of cities in Somalia by population, most populous city of Somalia. The city has served as an important port ...

.

Qadiriya

The Qadiriyah, the oldest Sufi order, was founded inBaghdad

Baghdad (; ar, بَغْدَاد , ) is the capital of Iraq and the second-largest city in the Arab world after Cairo. It is located on the Tigris near the ruins of the ancient city of Babylon and the Sassanid Persian capital of Ctesiphon ...

by Abdul Qadir al-Jilani in 1166 and introduced to the Somali Adal

Adal may refer to:

*A short form for Germanic names in ''aþala-'' (Old High German ''adal-''), "nobility, pedigree"; see Othalan

**Adál Maldonado (1948-2020), Puerto Rican artist

**Adal Ramones (born 1969), Mexican television show host

**Adal He ...

in the 15th century. During the 18th century, it was spread among the Oromo and the Afar of Ethiopia, often under the leadership of Somali shaykhs. Its earliest known advocate in northern Somalia was Shaykh Abd ar Rahman az Zeilawi, who died in 1883. At that time, Qadiriyah adherents were merchants in the ports and elsewhere. In a separate development, the Qadiriyah order also spread into the southern Somali port cities of Baraawe and Mogadishu at an uncertain date. In 1819, Shaykh Ibrahim Hassan Jebro acquired land on the Jubba River

The Jubba River or Juba River ( so, Wabiga Jubba) is a river in southern Somalia which flows through the autonomous region of Jubaland. It begins at the border with Ethiopia, where the Dawa and Ganale Dorya rivers meet, and flows directly south ...

and established a religious center in the form of a farming community, the first Somali jama'ah (congregation).

Outstanding figures of the Qadiriyah in Somalia included Shaykh Awes Mahammad Baraawi (d. 1909), who spread the teaching of the Sufi order in the southern interior. He wrote much devotional poetry in Arabic and attempted to translate traditional hymns from Arabic into Somali, working out his own phonetic system. Another was Shaykh Abdirrahman Abdullah of Mogadishu, who stressed deep mysticism. Because of his reputation for sanctity, his tomb at Mogadishu became a pilgrimage center for the Shebelle valley The Shebelle Valley ( so, Dooxada Shabeelle), also spelled Shabeelle Valley, is a valley in the Horn of Africa.

It follows the line of the Shebelle River north from the Somali Sea through Somalia and into Ethiopia.

Along with the Jubba Valley an ...

and his writings continued to be circulated by his followers as late as the early 1990s.

Idrisiya

The Idrisiyah order was founded by Ahmad ibn Idris (1760–1837) ofMecca

Mecca (; officially Makkah al-Mukarramah, commonly shortened to Makkah ()) is a city and administrative center of the Mecca Province of Saudi Arabia, and the Holiest sites in Islam, holiest city in Islam. It is inland from Jeddah on the Red ...

. It was brought to Somalia by Shaykh Ali Maye Durogba of Merca

Merca ( so, Marka, Maay Maay, Maay: ''Marky'', ar, مركة) is a historic port city in the southern Lower Shebelle province of Somalia. It is located approximately to the southwest of the nation's capital Mogadishu. Merca is the traditional home ...

in Somalia, a distinguished poet who joined the order during a pilgrimage to Mecca. His "visions" and "miracles" attributed to him gained him a reputation for sanctity, and his tomb became a popular destination for pilgrims. The Idrisiyah, the smallest of the three Sufi orders, has few ritual requirements beyond some simple prayers and hymns. During its ceremonies, however, participants often go into trances. A conflict over the leadership of the Idrisiyah among its Arab founders led to the establishment of the Salihiyah in 1887 by Muhammad ibn Salih. One of the Salihiyah's proselytizers was former slave Shaykh Mahammad Guled ar Rashidi, who became a regional leader. He settled among the Shidle people ( Bantus occupying the middle reaches of the Shebelle River

The Shebelle River ( so, Webi Shabeelle, ar, نهر شبيلي, am, እደላ) begins in the Ethiopian Highlands, highlands of Ethiopia, and then flows southeast into Somalia towards Mogadishu. Near Mogadishu, it turns sharply southwest, where ...

), where he obtained land and established a jama'ah. Later he founded another jama'ah among the Ajuran (a section of the Hawiye clanfamily ) and then returned to establish still another community among the Shidle before his death in 1918.

Salihiyya

A Somali form of the Salihiya tariqa was established in what is now northern Somalia in 1890 by Ismail Urwayni. Urwayni's proselytism in northern Somalia had a profound effect on the peninsula as it would later prompt the creation of the Darwiish State. The primary friction between the more established Qadiriya and the newly established Somali Salihism in the form of Urwayniya was their reaction to incursions by European colonialists with the former appearing too lax by adherents of the latter. Five years later, another neo-Salihiya figure expedited Urwaynism or Urwayniya through proselytizing, via the Darawiish wherein Diiriye Guure was sultan and wherein the Salihiyya preacher Sayyid Mohammed Abdullah Hassan, would become emir of the Dervish movement in a lengthy resistance to the Abyssinian, Italian andBritish

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

colonialists until 1920.

Generally, the Salihiyah and the Idrisiyah leaders were more interested in the establishment of a jama'ah along the Shabeelle and Jubba river

The Jubba River or Juba River ( so, Wabiga Jubba) is a river in southern Somalia which flows through the autonomous region of Jubaland. It begins at the border with Ethiopia, where the Dawa and Ganale Dorya rivers meet, and flows directly south ...

s and the fertile land between them than in teaching because few were learned in Islam. Their early efforts to establish farming communities resulted in cooperative cultivation and harvesting and some effective agricultural methods. In Somalia's riverine region, for example, only jama'ah members thought of stripping the brush from areas around their fields to reduce the breeding places of tsetse flies.

Salafism and Zahirism

Following the outbreak of thecivil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

in the early 1990s, Islamism appeared to be largely confined to the radical Al-Itihaad al-Islamiya

Al-Itihaad al-Islamiya (AIAI; ar-at, الاتحاد الإسلامي, lit=The Islamic Union) was an Islamist militant group in Somalia. It is considered a terrorist organisation by the United States, the United Kingdom and New Zealand.

Histor ...

group. In 1992, Colonel Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed

Abdullahi Yusuf Ahmed ( so, Cabdulaahi Yuusuf Axmed, ar, عبدالله يوسف أحمد; 15 December 1934 – 23 March 2012) was a Somali politician and former colonel in the Somali National Army. He was one of the founders of the Somali ...

marshalled forces to successfully expel an Islamist extremist group linked to the outfit, which had laid siege to Bosaso

Bosaso ( so, Boosaaso, ar, بوصاصو), historically known as Bender Cassim is a city in the northeastern Bari province ('' gobol'') of Somalia. It is the seat of the Bosaso District. Located on the southern coast of the Gulf of Aden, the mun ...

, a prominent port city and the commercial capital of the northeastern part of the country. The turn of the 21st century saw an increasing prevalence of puritanical Sunnism, including in the form of Muwahhidism The People of Monotheism may translate several Arabic terms:

* ( ar, أهل التوحيد), a name the Druze use for themselves. Literally, "The People of the Unity" or "The Unitarians", from '' '', unity (of God).

* ( ar, الموحدون) is ...

and Salafism

The Salafi movement or Salafism () is a Islah, reform branch movement within Sunni Islam that originated during the nineteenth century. The name refers to advocacy of a return to the traditions of the "pious predecessors" (), the first three g ...

.

Although there is no official demographic figures on Zahirism

The Ẓāhirī ( ar, ظاهري, otherwise transliterated as ''Dhāhirī'') ''madhhab'' or al-Ẓāhirīyyah ( ar, الظاهرية) is a Sunnī school of Islamic jurisprudence founded by Dāwūd al-Ẓāhirī in the 9th century CE. It is chara ...

in Somalia, many Somalis follow methods of practicing Islam that aligns with Zahiri beliefs, such as a suspicion towards human authority regarding Islamic legal matters.

Shia

Ibn Battuta in his travels to Zeila, in northwest Somalia, in the 14th century, described it as a town of Shiites. The Saudi invasion of Yemen in 2015 resulted in large amounts ofZaydi

Zaydism (''h'') is a unique branch of Shia Islam that emerged in the eighth century following Zayd ibn Ali‘s unsuccessful rebellion against the Umayyad Caliphate. In contrast to other Shia Muslims of Twelver Shi'ism and Isma'ilism, Zaydis, ...

Shia Yemeni refugees seeking refuge in northern Somalia.

There has never been a comprehensive survey on religious affiliation in Somalia, and as such, figures on adherence are largely based upon speculation. The historian David Westerlund refers to both Shia and Wahhabi

Wahhabism ( ar, ٱلْوَهَّابِيَةُ, translit=al-Wahhābiyyah) is a Sunni Islamic revivalist and fundamentalist movement associated with the reformist doctrines of the 18th-century Arabian Islamic scholar, theologian, preacher, an ...

(Hanbali

The Hanbali school ( ar, ٱلْمَذْهَب ٱلْحَنۢبَلِي, al-maḏhab al-ḥanbalī) is one of the four major traditional Sunni schools (''madhahib'') of Islamic jurisprudence. It is named after the Arab scholar Ahmad ibn Hanbal ...

''madhab'') sects in Somalia as relatively recent developments.

The city of Zeila

Zeila ( so, Saylac, ar, زيلع, Zayla), also known as Zaila or Zayla, is a historical port town in the western Awdal region of Somaliland.

In the Middle Ages, the Jewish traveller Benjamin of Tudela identified Zeila (or Hawilah) with the Bibl ...

began to gradually lose its Shiite character during the period between 1623 and 1639, when the Ottoman administrators came to increasingly regard the Shiism practised by the local Somali Shiites as heretic due to the ongoing Safavid-Ottoman War against Safi of Persia

Sam Mirza ( fa, سام میرزا) (161112 May 1642), better known by his dynastic name of Shah Safi ( fa, شاه صفی), was the sixth Safavid shah (king) of Iran, ruling from 1629 to 1642.

Early life

Safi was given the name Sam Mirza when ...

.

Non-denominational Muslim

Although there has never been a comprehensive census in Somalia that lists various Islamic denominations as an option, there have been some Somalis in the diaspora who have used the self-description of "just a Muslim" upon probes into their religious affiliation.Ibadi

Ibadism is predominant in Oman and is characterized by the acceptance of fewer hadiths, and the acceptance ofJami Sahih

''Jami Sahih'' is, along with '' Tartib al-Musnad'', the most important hadith collection for Ibadi

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

...

and Tartib al-Musnad

Tartib al-Musnad is the principal hadith collection of the Ibadi

The Ibadi movement or Ibadism ( ar, الإباضية, al-Ibāḍiyyah) is a school of Islam. The followers of Ibadism are known as the Ibadis.

Ibadism emerged around 60 years a ...

as canonical hadith collections. Although Ibadism has not officially been reported being practiced in Somalia, certain Eastern Harti clans who migrated from Somalia in the medieval period whom are known as Dishiishes or Muhdis live in modest numbers in Oman, wherein Ibadism is the state religion.Almakrami, Mohsen Hebah. "Number, gender and tense in Aljudhi dialect of Mehri language in Saudi Arabia." Theory and Practice in Language Studies 5.11 (2015): 2230–2241

See also

*Islam by country

Adherents of Islam constitute the world's second largest religious group. According to an estimation in 2022, Islam has 1.97 billion adherents, making up about 25% of the world population. A projection by the PEW suggests that Muslims number ...

* Islamic Court Union

The Islamic Courts Union ( so, Midowga Maxkamadaha Islaamiga) was a legal and political organization formed to address the lawlessness that had been gripping Somalia since the fall of the Siad Barre regime in 1991 during the Somali Civil War.

Th ...

* Religion in Somalia

The predominant religion in Somalia is Islam.

State religion

Islam

Most residents of Somalia are Muslims, of which some sources state that Sunnism is the strand practised by 99% of the population, whereof in particular the Shafi'i school of ...

References

*External links

Somali Qadiriya (Somali language)

{{Somalia topics

Somalia

Somalia, , Osmanya script: 𐒈𐒝𐒑𐒛𐒐𐒘𐒕𐒖; ar, الصومال, aṣ-Ṣūmāl officially the Federal Republic of SomaliaThe ''Federal Republic of Somalia'' is the country's name per Article 1 of thProvisional Constituti ...