International Law on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

International law (also known as public international law and the law of nations) is the set of rules, norms, and standards generally recognized as binding between states. It establishes normative guidelines and a common conceptual framework for states across a broad range of domains, including

The origins of international law can be traced back to antiquity. Among the earliest examples are peace treaties between the

The origins of international law can be traced back to antiquity. Among the earliest examples are peace treaties between the

The developments of the 17th century came to a head at the conclusion of the " Peace of Westphalia" in 1648, which is considered to be the seminal event in international law. The resulting "

The developments of the 17th century came to a head at the conclusion of the " Peace of Westphalia" in 1648, which is considered to be the seminal event in international law. The resulting " The concept of sovereignty was spread throughout the world by European powers, which had established colonies and spheres of influences over virtually every society. Positivism reached its peak in the late 19th century and its influence began to wane following the unprecedented bloodshed of the

The concept of sovereignty was spread throughout the world by European powers, which had established colonies and spheres of influences over virtually every society. Positivism reached its peak in the late 19th century and its influence began to wane following the unprecedented bloodshed of the

ICJ 1

ICJ had no jurisdiction to hear a dispute between the UK government and a private Greek businessman under the terms of a treaty. *''United Kingdom v Iran'' [1952

ICJ 2

the ICJ did not have jurisdiction for a dispute over the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company being nationalized. *''Oil Platforms case (Islamic Republic of Iran v United States of America)'' [2003

ICJ 4

rejected dispute over damage to ships which hit a mine.

ICJ 1

*''Democratic Republic of the Congo v Belgium'' [2002

ICJ 1

ICJ 1

*''United Kingdom v Norway'' [1951

ICJ 3

the Fisheries case, concerning the limits of Norway's jurisdiction over neighboring waters *''Peru v Chile'' (2014) dispute over international waters. *''Bakassi case'' [2002

ICJ 2

between Nigeria and Cameroon *''Burkina Faso-Niger frontier dispute case'' (2013) *United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea *''Corfu Channel Case'' [1949

ICJ 1

UK sues Albania for damage to ships in international waters. First ICJ decision. *''France v United Kingdom'' [1953

ICJ 3

*''Germany v Denmark and the Netherlands'' [1969

ICJ 1

successful claim for a greater share of the North Sea continental shelf by Germany. The ICJ held that the matter ought to be settled, not according to strict legal rules, but through applying equitable principles. *''Case concerning maritime delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v Ukraine)'' [2009

ICJ 3

ICJ 8

Sweden had jurisdiction over its guardianship policy, meaning that its laws overrode a conflicting guardianship order of the Netherlands. *''Liechtenstein v Guatemala'' [1955

ICJ 1

the recognition of Mr Nottebohm's nationality, connected to diplomatic protection. *''Italy v France, United Kingdom and United States'' [1954

ICJ 2

ICJ 2

*''Case Concerning Barcelona Traction, Light, and Power Company, Ltd'' [1970

ICJ 1

ICJ 1

*''International Court of Justice advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons''

United Nations Rule of Law

the United Nations' centralised website on the rule of law

UNOG Library Legal Research Guide

International law overview

Primary Legal Documents Critical to an Understanding of the Development of Public International Law

Public International Law as a Form of Private Ordering

Public International Law – Resources

With cases and commentary. Nathaniel Burney, 2007.

* [https://web.archive.org/web/20070911220658/https://www.asil.org/resource/ergintr1.htm American Society of International Law – Resource Guide (Introduction)]

International Law Details

International Law Observer – Blog dedicated to reports and commentary on International Law

Official United Nations website

Official UN website on International Law

Official website of the International Court of Justice

Opinio Juris – Blog on International Law and International Relations

United Nations Treaty Collection

UN – Audiovisual Library of International Law

* [http://works.bepress.com/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1011&context=bryan_druzin Public International Law as a Form of Private Ordering]

Public International Law, Research Guide

Peace Palace Library

UNOG Library – Legal Research Guide

{{Authority control International law, International trade law Public law, International International relations Cultural globalization

war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

, diplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

, economic relations, and human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

. Scholars distinguish between international legal institutions on the basis of their obligations (the extent to which states are bound to the rules), precision (the extent to which the rules are unambiguous), and delegation (the extent to which third parties have authority to interpret, apply and make rules).

The sources of international law

International law, also known as "law of nations", refers to the body of rules which regulate the conduct of sovereign states in their relations with one another. Sources of international law include treaties, international customs, general ...

include international custom (general state practice accepted as law), treaties

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations, individuals, business entities, and other legal pers ...

, and general principles of law recognized by most national legal systems. Although international law may also be reflected in international comity—the practices adopted by states to maintain good relations and mutual recognition, such as saluting the flag of a foreign ship—such traditions are not legally binding.

International law differs from state-based legal systems in that it is primarily—though not exclusively—applicable to states, rather than to individuals, and operates largely through consent, since there is no universally accepted authority to enforce it upon sovereign states. Consequently, states may choose to not abide by international law, and even to breach a treaty. However, such violations, particularly of customary international law and peremptory norms (''jus cogens

Jus may refer to:

Law

* Jus (law), the Latin word for law or right

* Jus (canon law), a rule within the Roman Catholic Church

People

* Juš Kozak (1892–1964), Slovenian writer

* Juš Milčinski, Slovenian theatre improviser

* Justin Jus ...

''), can be met with disapproval by others and in some cases coercive action (ranging from diplomatic and economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they ma ...

to war).

The relationship and interaction between a national legal system (municipal law

Municipal law is the national, domestic, or internal law of a sovereign state and is defined in opposition to international law. Municipal law includes many levels of law: not only national law but also state, provincial, territorial, regional, ...

) and international law is complex and variable. National law may become international law when treaties permit national jurisdiction to supranational Supranational or supra-national may refer to:

* Supranational union, a type of multinational political union

* Supranational law, a form of international law

* Supranational legislature, a form of international legislature

* Supranational curre ...

tribunals such as the European Court of Human Rights

The European Court of Human Rights (ECHR or ECtHR), also known as the Strasbourg Court, is an international court of the Council of Europe which interprets the European Convention on Human Rights. The court hears applications alleging that a ...

or the International Criminal Court

The International Criminal Court (ICC or ICCt) is an intergovernmental organization and international tribunal seated in The Hague, Netherlands. It is the first and only permanent international court with jurisdiction to prosecute individuals f ...

. Treaties such as the Geneva Conventions

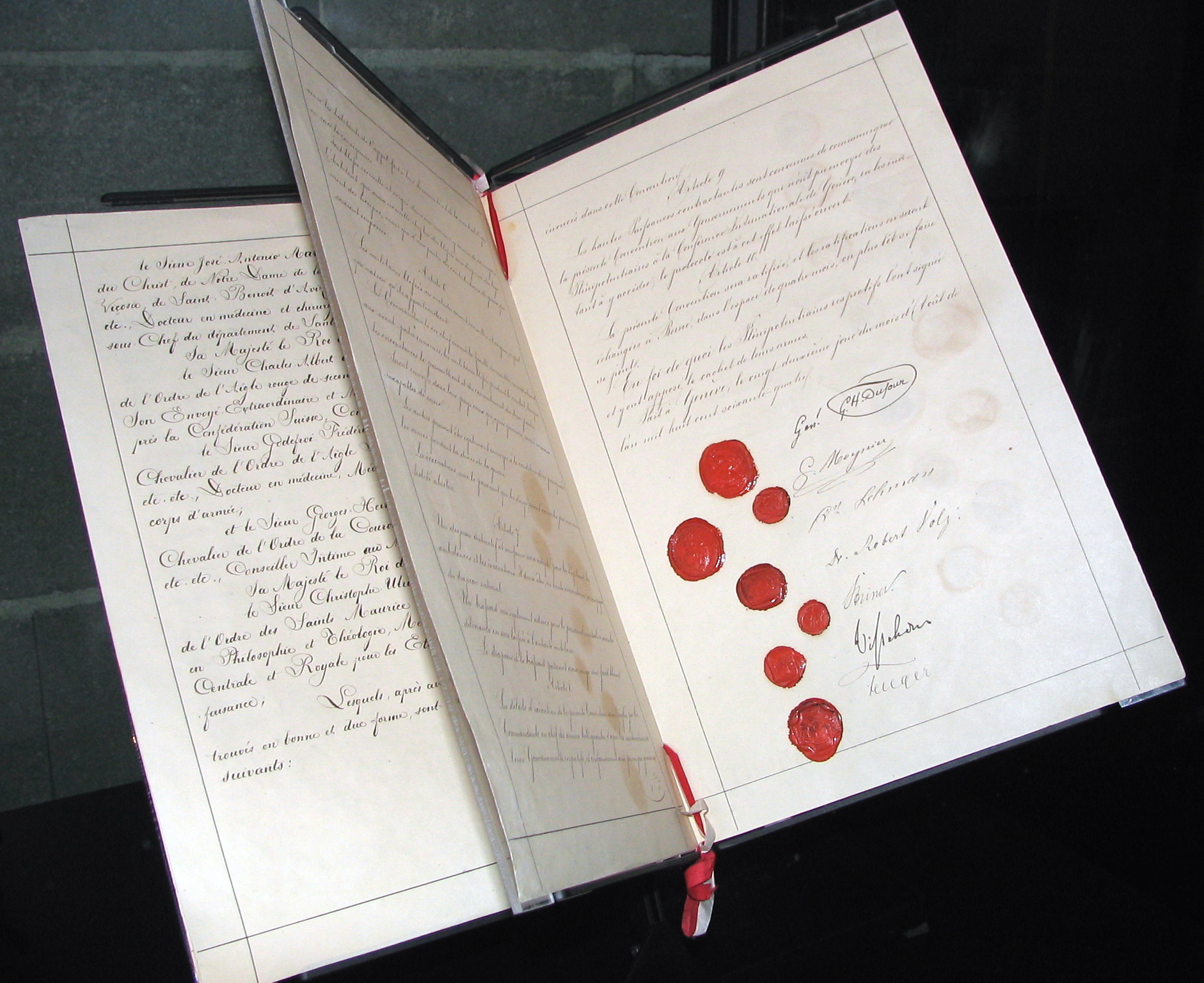

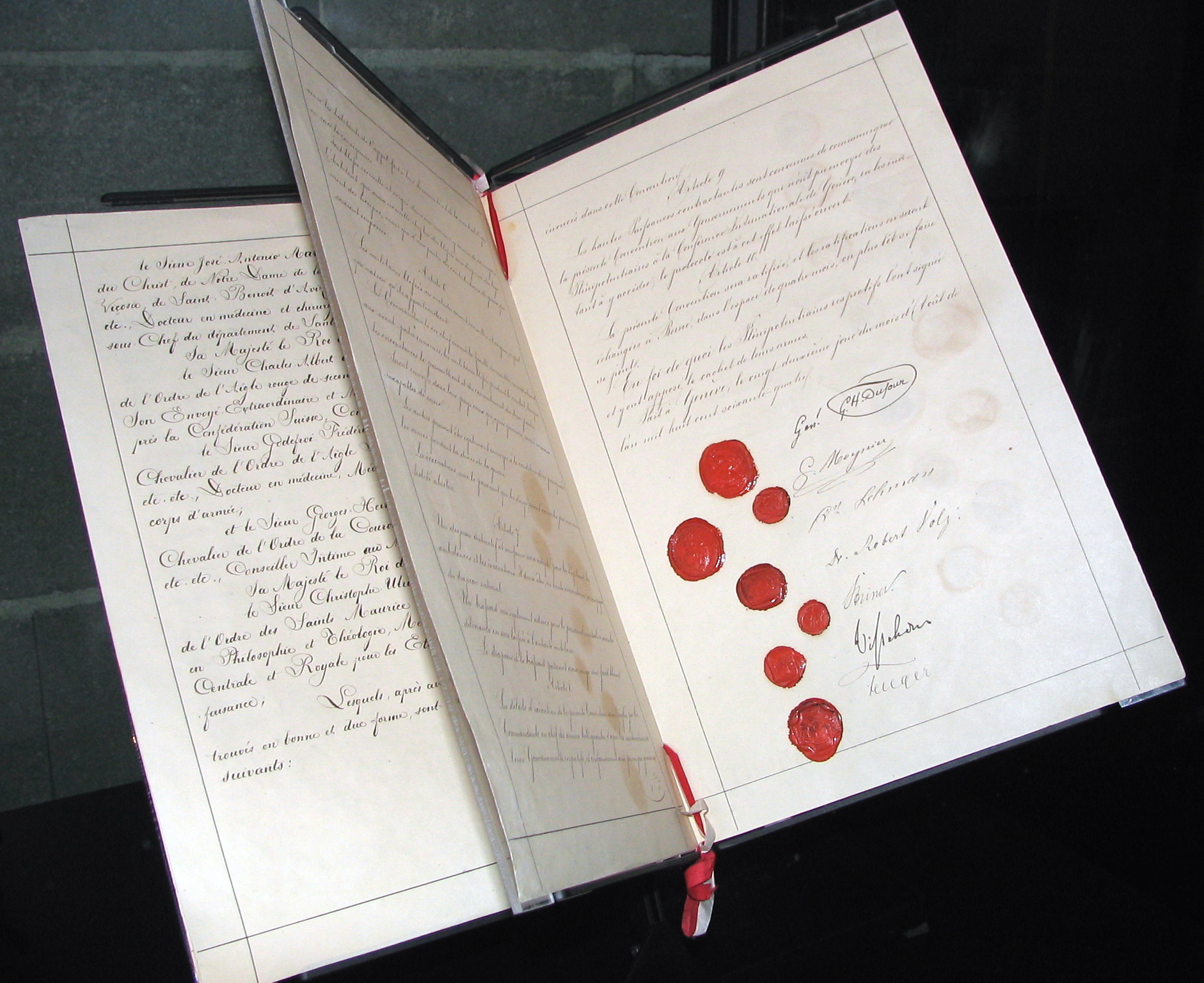

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

may require national law to conform to treaty provisions. National laws or constitutions may also provide for the implementation or integration of international legal obligations into domestic law.

Terminology

The term "international law" is sometimes divided into "public" and "private" international law, particularly by civil law scholars, who seek to follow a Roman tradition. Roman lawyers would have further distinguished '' jus gentium'', the law of nations, and ''jus inter gentes

''Jus inter gentes'', is the body of treaties, U.N. conventions, and other international agreements. Originally a Roman law concept, it later became a major part of public international law. The other major part is '' jus gentium'', the Law of Na ...

'', agreements between nations. On this view, "public" international law is said to cover relations between nation-states and includes fields such as treaty law

The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties (VCLT) is an international agreement regulating treaties between states. Known as the "treaty on treaties", it establishes comprehensive rules, procedures, and guidelines for how treaties are defined ...

, law of sea, international criminal law

International criminal law (ICL) is a body of public international law designed to prohibit certain categories of conduct commonly viewed as serious atrocities and to make perpetrators of such conduct criminally accountable for their perpetrat ...

, the laws of war

The law of war is the component of international law that regulates the conditions for initiating war (''jus ad bellum'') and the conduct of warring parties (''jus in bello''). Laws of war define sovereignty and nationhood, states and territor ...

or international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pro ...

, international human rights law

International human rights law (IHRL) is the body of international law designed to promote human rights on social, regional, and domestic levels. As a form of international law, international human rights law are primarily made up of treaties, a ...

, and refugee law. By contrast "private" international law, which is more commonly termed "conflict of laws

Conflict of laws (also called private international law) is the set of rules or laws a jurisdiction applies to a case, transaction, or other occurrence that has connections to more than one jurisdiction. This body of law deals with three broad t ...

", concerns whether courts within countries claim jurisdiction over cases with a foreign element, and which country's law applies.

When the modern system of (public) international law developed out of the tradition of the late medieval ''ius gentium,'' it was referred to as ''the law of nations,'' a direct translation of the concept ''ius gentium used'' by Hugo Grotius and ''droits des gens'' of Emer de Vattel

Emer (Emmerich) de Vattel ( 25 April 171428 December 1767) was an international lawyer. He was born in Couvet in the Principality of Neuchâtel (now a canton part of Switzerland but part of Prussia at the time) in 1714 and died in 1767. He was l ...

. The modern term ''international law'' was invented by Jeremy Bentham

Jeremy Bentham (; 15 February 1748 Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates">O.S._4_February_1747.html" ;"title="Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.html" ;"title="nowiki/>Old Style and New Style dates">O.S. 4 February 1747">Old_Style_and_New_Style_dates.htm ...

in 1789 and established itself in the 19th century.

A more recent concept is "supranational law Supranational law is a form of international law, based on the limitation of the rights of sovereign nations between one another. It is distinguished from public international law, because in supranational law, nations explicitly submit their right ...

", which concerns regional agreements where the laws of nation states may be held inapplicable when conflicting with a supranational legal system to which the nation has a treaty

A treaty is a formal, legally binding written agreement between actors in international law. It is usually made by and between sovereign states, but can include international organizations

An international organization or international o ...

obligation. Systems of supranational Supranational or supra-national may refer to:

* Supranational union, a type of multinational political union

* Supranational law, a form of international law

* Supranational legislature, a form of international legislature

* Supranational curre ...

law arise when nations explicitly cede their right to make certain judicial decisions to a common tribunal. The decisions of the common tribunal are directly effective in each party nation, and have priority over decisions taken by national courts. The European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

is the most prominent example of an international treaty organization that implements a supranational legal framework, with the European Court of Justice having supremacy over all member-nation courts in matter of European Union law.

The term "transnational law" is sometimes used to a body of rules of private law

Private law is that part of a civil law legal system which is part of the ''jus commune'' that involves relationships between individuals, such as the law of contracts and torts (as it is called in the common law), and the law of obligations ( ...

that transcend the nation state.

History

The origins of international law can be traced back to antiquity. Among the earliest examples are peace treaties between the

The origins of international law can be traced back to antiquity. Among the earliest examples are peace treaties between the Mesopotamia

Mesopotamia ''Mesopotamíā''; ar, بِلَاد ٱلرَّافِدَيْن or ; syc, ܐܪܡ ܢܗܪ̈ܝܢ, or , ) is a historical region of Western Asia situated within the Tigris–Euphrates river system, in the northern part of the ...

n city-states of Lagash

Lagash (cuneiform: LAGAŠKI; Sumerian: ''Lagaš''), was an ancient city state located northwest of the junction of the Euphrates and Tigris rivers and east of Uruk, about east of the modern town of Ash Shatrah, Iraq. Lagash (modern Al-Hiba) w ...

and Umma

Umma ( sux, ; in modern Dhi Qar Province in Iraq, formerly also called Gishban) was an ancient city in Sumer. There is some scholarly debate about the Sumerian and Akkadian names for this site. Traditionally, Umma was identified with Tell J ...

(approximately 2100 BCE), and an agreement between the Egyptian pharaoh

Pharaoh (, ; Egyptian: '' pr ꜥꜣ''; cop, , Pǝrro; Biblical Hebrew: ''Parʿō'') is the vernacular term often used by modern authors for the kings of ancient Egypt who ruled as monarchs from the First Dynasty (c. 3150 BC) until the a ...

Ramses II

Ramesses II ( egy, rꜥ-ms-sw ''Rīʿa-məsī-sū'', , meaning "Ra is the one who bore him"; ), commonly known as Ramesses the Great, was the third pharaoh of the Nineteenth Dynasty of Egypt. Along with Thutmose III he is often regarded as t ...

and the Hittite king The dating and sequence of the Hittite kings is compiled from fragmentary records, supplemented by the recent find in Hattusa of a cache of more than 3500 seal impressions giving names and titles and genealogy of Hittite kings. All dates given here ...

, Hattusilis III Ḫattušili (''Ḫattušiliš'' in the inflected nominative case) was the regnal name of three Hittite kings:

* Ḫattušili I (Labarna II)

*Ḫattušili II

*Ḫattušili III

It was also the name of two Neo-Hittite kings:

* Ḫattušili I (Labarn ...

, concluded in 1258 BCE. Interstate pacts and agreements of various kinds were also negotiated and concluded by polities

A polity is an identifiable political entity – a group of people with a collective identity, who are organized by some form of institutionalized social relations, and have a capacity to mobilize resources. A polity can be any other group of p ...

across the world, from the eastern Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western Europe, Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa ...

to East Asia

East Asia is the eastern region of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The modern states of East Asia include China, Japan, Mongolia, North Korea, South Korea, and Taiwan. China, North Korea, South Korea and ...

.

Ancient Greece

Ancient Greece ( el, Ἑλλάς, Hellás) was a northeastern Mediterranean civilization, existing from the Greek Dark Ages of the 12th–9th centuries BC to the end of classical antiquity ( AD 600), that comprised a loose collection of cult ...

, which developed basic notions of governance and international relations, contributed to the formation of the international legal system; many of the earliest peace treaties on record were concluded among the Greek city-states

''Polis'' (, ; grc-gre, πόλις, ), plural ''poleis'' (, , ), literally means "city" in Greek. In Ancient Greece, it originally referred to an administrative and religious city center, as distinct from the rest of the city. Later, it also ...

or with neighboring states. The Roman Empire

The Roman Empire ( la, Imperium Romanum ; grc-gre, Βασιλεία τῶν Ῥωμαίων, Basileía tôn Rhōmaíōn) was the post-Republican period of ancient Rome. As a polity, it included large territorial holdings around the Mediterr ...

established an early conceptual framework for international law, ''jus gentium'' ("law of nations"), which governed both the status of foreigners living in Rome and relations between foreigners and Roman citizens

Citizenship in ancient Rome (Latin: ''civitas'') was a privileged political and legal status afforded to free individuals with respect to laws, property, and governance. Citizenship in Ancient Rome was complex and based upon many different laws, t ...

. Adopting the Greek concept of natural law

Natural law ( la, ius naturale, ''lex naturalis'') is a system of law based on a close observation of human nature, and based on values intrinsic to human nature that can be deduced and applied independently of positive law (the express enacte ...

, the Romans conceived of ''jus gentium'' as being universal. However, in contrast to modern international law, the Roman law of nations applied to relations with and between foreign individuals rather than among political units such as states.

Beginning with the Spring and Autumn period of the eighth century BCE, China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

was divided into numerous states that were often at war with each other. Subsequently, there emerged rules for diplomacy and treaty-making, including notions regarding the just grounds for war, the rights of neutral parties, and the consolidation and partition of states; these concepts were sometimes applied to relations with "barbarians" along China's western periphery beyond the Central Plains. The subsequent Warring States period

The Warring States period () was an era in ancient Chinese history characterized by warfare, as well as bureaucratic and military reforms and consolidation. It followed the Spring and Autumn period and concluded with the Qin wars of conquest ...

saw the development of two major schools of thought, Confucianism

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

and Legalism, both of which held that the domestic and international legal spheres were closely interlinked, and sought to establish competing normative principles to guide foreign relations. Similarly, the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

was characterized by an ever-changing panoply of states, which over time developed rules of neutrality, treaty law, and international conduct. Embassies both temporary and permanent were established between states to maintain diplomatic relations, and relations were conducted with distant states in Europe and East Asia.

Following the collapse of the western Roman Empire

The fall of the Western Roman Empire (also called the fall of the Roman Empire or the fall of Rome) was the loss of central political control in the Western Roman Empire, a process in which the Empire failed to enforce its rule, and its vas ...

in the fifth century CE, Europe fragmented into numerous often-warring states for much of the next five centuries. Political power was dispersed across a range of entities, including the Church

Church may refer to:

Religion

* Church (building), a building for Christian religious activities

* Church (congregation), a local congregation of a Christian denomination

* Church service, a formalized period of Christian communal worship

* C ...

, mercantile city-states, and kingdoms, most of which had overlapping and ever-changing jurisdictions. As in China and India, these divisions prompted the development of rules aimed at providing stable and predictable relations. Early examples include canon law

Canon law (from grc, κανών, , a 'straight measuring rod, ruler') is a set of ordinances and regulations made by ecclesiastical authority (church leadership) for the government of a Christian organization or church and its members. It is th ...

, which governed ecclesiastical institutions and clergy throughout Europe; the ''lex mercatoria

''Lex mercatoria'' (from the Latin for "merchant law"), often referred to as "the Law Merchant" in English, is the body of commercial law used by merchants throughout Europe during the medieval period. It evolved similar to English common law as ...

'' ("merchant law"), which concerned trade and commerce; and various codes of maritime law, such as the Rolls of Oléron

The Rolls of Oléron (French: ''Jugements de la mer, Rôles d'Oléron'') are the oldest and best-known sea law regulating medieval shipping in North-western Europe. The Rolls of Oleron were the first common sea law written in the Isle of Oléron, ...

—which drew from the ancient Roman ''Lex Rhodia''—and the Laws of Wisby (Visby

Visby () is an urban area in Sweden and the seat of Gotland Municipality in Gotland County on the island of Gotland with 24,330 inhabitants . Visby is also the episcopal see for the Diocese of Visby. The Hanseatic city of Visby is arguably th ...

), enacted among the commercial Hanseatic League

The Hanseatic League (; gml, Hanse, , ; german: label=Modern German, Deutsche Hanse) was a medieval commercial and defensive confederation of merchant guilds and market towns in Central and Northern Europe. Growing from a few North German to ...

of northern Europe and the Baltic region

The terms Baltic Sea Region, Baltic Rim countries (or simply the Baltic Rim), and the Baltic Sea countries/states refer to slightly different combinations of countries in the general area surrounding the Baltic Sea, mainly in Northern Europe. ...

.

Concurrently, in the Islamic world, foreign relations were guided based on the division of the world into three categories: The ''dar al-Islam

In classical Islamic law, the major divisions are ''dar al-Islam'' (lit. territory of Islam/voluntary submission to God), denoting regions where Islamic law prevails, ''dar al-sulh'' (lit. territory of treaty) denoting non-Islamic lands which have ...

'' (territory of Islam), where Islamic law prevailed; ''dar al-sulh'' (territory of treaty), non-Islamic realms that have concluded an armistice with a Muslim government; and ''dar al-harb'' (territory of war), non-Islamic lands whose rulers are called upon to accept Islam''.'' Under the early Caliphate

A caliphate or khilāfah ( ar, خِلَافَة, ) is an institution or public office under the leadership of an Islamic steward with the title of caliph (; ar, خَلِيفَة , ), a person considered a political-religious successor to th ...

of the seventh century C.E., Islamic legal principles concerning military conduct and the treatment of prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

served as precursors to modern international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pro ...

. Islamic law in this period institutionalised humanitarian limitations on military conduct, including attempts to limit the severity of war, guidelines for ceasing hostilities, distinguishing between civilians and combatants, preventing unnecessary destruction, and caring for the sick and wounded. The many requirements on how prisoners of war should be treated included providing shelter, food and clothing, respecting their cultures, and preventing any acts of execution, rape, or revenge. Some of these principles were not codified in Western

Western may refer to:

Places

*Western, Nebraska, a village in the US

*Western, New York, a town in the US

*Western Creek, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western Junction, Tasmania, a locality in Australia

*Western world, countries that id ...

international law until modern times.

During the European Middle Ages

In the history of Europe, the Middle Ages or medieval period lasted approximately from the late 5th to the late 15th centuries, similar to the post-classical period of global history. It began with the fall of the Western Roman Empire a ...

, international law was concerned primarily with the purpose and legitimacy of war, seeking to determine what constituted a "just war". For example, the theory of armistice held the nation that caused unwarranted war could not enjoy the right to obtain or conquer trophies that were legitimate at the time. The Greco-Roman concept of natural law was combined with religious principles by Jewish philosopher Moses Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah s ...

(1135–1204) and Christian theologian Thomas Aquinas

Thomas Aquinas, OP (; it, Tommaso d'Aquino, lit=Thomas of Aquino; 1225 – 7 March 1274) was an Italian Dominican friar and priest who was an influential philosopher, theologian and jurist in the tradition of scholasticism; he is known wi ...

(1225–1274) to create the new discipline of the "law of nations", which unlike its eponymous Roman predecessor applied natural law to relations between states. In Islam, a similar framework was developed wherein the law of nations was derived, in part, from the principles and rules set forth in treaties with non-Muslims.

Emergence of modern international law

The 15th century witnessed a confluence of factors that contributed to an accelerated development of international law into its current framework. The influx ofGreek scholars

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

from the collapsing Byzantine Empire, along with the introduction of the printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

, spurred the development of science, humanism, and notions of individual rights. Increased navigation and exploration by Europeans challenged scholars to devise a conceptual framework for relations with different peoples and cultures. The formation of centralized states such as Spain

, image_flag = Bandera de España.svg

, image_coat = Escudo de España (mazonado).svg

, national_motto = ''Plus ultra'' (Latin)(English: "Further Beyond")

, national_anthem = (English: "Royal March")

, i ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

brought more wealth, ambition, and trade, which in turn required increasingly more sophisticated rules and regulations.

The Italian peninsula, divided among various city-states with complex and often fractious relationships, was subsequently an early incubator of international law theory. Jurist and law professor Bartolus da Saxoferrato (1313–1357), who was well versed in Roman and Byzantine law

Byzantine law was essentially a continuation of Roman law with increased Orthodox Christian and Hellenistic influence. Most sources define ''Byzantine law'' as the Roman legal traditions starting after the reign of Justinian I in the 6th century ...

, contributed to the increasingly relevant area of " conflicts of law", which concerns disputes between private individuals and entities in different sovereign jurisdictions; he is thus considered the founder of private international law

Conflict of laws (also called private international law) is the set of rules or laws a jurisdiction applies to a case, transaction, or other occurrence that has connections to more than one jurisdiction. This body of law deals with three broad t ...

. Another Italian jurist and law professor, Baldus de Ubaldis

Baldus de Ubaldis (Italian: ''Baldo degli Ubaldi''; 1327 – 28 April 1400) was an Italian jurist, and a leading figure in Medieval Roman Law and the school of Postglossators.

Life

A member of the noble family of the Ubaldi (Baldeschi), ...

(1327–1400), provided voluminous commentaries and compilations of Roman, ecclesiastical, and feudal law

Feudalism, also known as the feudal system, was the combination of the legal, economic, military, cultural and political customs that flourished in medieval Europe between the 9th and 15th centuries. Broadly defined, it was a way of structur ...

, thus creating an organized source of law that could be referenced by different nations. The most famous contributor from the region, Alberico Gentili

Alberico Gentili (14 January 155219 June 1608) was an Italian-English jurist, a tutor of Queen Elizabeth I, and a standing advocate to the Spanish Embassy in London, who served as the Regius professor of civil law at the University of Oxfor ...

(1552–1608), is considered a founder of international law, authoring one of the earliest works on the subject, ''De Legationibus Libri Tres'', in 1585. He wrote several more books on various issues in international law, notably ''De jure belli libri tres'' (''Three Books on the Law of War''), which provided comprehensive commentary on the laws of war and treaties,

Spain, whose global empire spurred a golden age of economic and intellectual development in the 16th and 17th centuries, produced major contributors to international law. Francisco de Vitoria

Francisco de Vitoria ( – 12 August 1546; also known as Francisco de Victoria) was a Spanish Roman Catholic philosopher, theologian, and jurist of Renaissance Spain. He is the founder of the tradition in philosophy known as the School of Sala ...

(1486–1546), who was concerned with the treatment of the indigenous peoples by Spain, invoked the law of nations as a basis for their innate dignity and rights, articulating an early version of sovereign equality between peoples. Francisco Suárez (1548–1617) emphasized that international law was founded upon the law of nature.

The Dutch jurist Hugo Grotius (1583–1645) is widely regarded as the most seminal figure in international law, being one of the first scholars to articulate an international order that consists of a "society of states" governed not by force

In physics, a force is an influence that can change the motion of an object. A force can cause an object with mass to change its velocity (e.g. moving from a state of rest), i.e., to accelerate. Force can also be described intuitively as a p ...

or warfare

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regul ...

but by actual laws, mutual agreements, and customs. Grotius secularized international law and organized it into a comprehensive system; his 1625 work, ''De Jure Belli ac Pacis

''De iure belli ac pacis'' (English: ''On the Law of War and Peace'') is a 1625 book in Latin, written by Hugo Grotius and published in Paris, on the legal status of war. It is now regarded as a foundational work in international law. The work t ...

'' (''On the Law of War and Peace''), laid down a system of principles of natural law that bind all nations regardless of local custom or law. He also emphasized the freedom of the high seas, which was not only relevant to the growing number of European states exploring and colonising the world, but remains a cornerstone of international law today. Although the modern study of international law would not begin until the early 19th century, the 16th-century scholars Gentili, Vitoria and Grotius laid the foundations and are widely regarded as the "fathers of international law".

Grotius inspired two nascent schools of international law, the naturalists and the positivists. In the former camp was German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

jurist Samuel von Pufendorf (1632–94), who stressed the supremacy of the law of nature over states. His 1672 work, ''De iure naturae et gentium,'' expanded on the theories of Grotius and grounded natural law to reason

Reason is the capacity of consciously applying logic by drawing conclusions from new or existing information, with the aim of seeking the truth. It is closely associated with such characteristically human activities as philosophy, science, ...

and the secular world, asserting that it regulates only the external acts of states. Pufendorf challenged the Hobbesian notion that the state of nature was one of war and conflict, arguing that the natural state of the world is actually peaceful but weak and uncertain without adherence to the law of nations. The actions of a state consist of nothing more than the sum of the individuals within that state, thereby requiring the state to apply a fundamental law of reason, which is the basis of natural law. He was among the earliest scholars to expand international law beyond European Christian nations, advocating for its application and recognition among all peoples on the basis of shared humanity.

In contrast, positivist writers, such as Richard Zouche (1590–1661) in England and Cornelis van Bynkershoek (1673–1743) in the Netherlands, argued that international law should derive from the actual practice of states rather than Christian or Greco-Roman sources. The study of international law shifted away from its core concern on the law of war and towards the domains such as the law of the sea and commercial treaties. The positivist school made use of the new scientific method and was in that respect consistent with the empiricist and inductive approach to philosophy that was then gaining acceptance in Europe.

Establishment of "Westphalian system"

The developments of the 17th century came to a head at the conclusion of the " Peace of Westphalia" in 1648, which is considered to be the seminal event in international law. The resulting "

The developments of the 17th century came to a head at the conclusion of the " Peace of Westphalia" in 1648, which is considered to be the seminal event in international law. The resulting "Westphalian sovereignty

Westphalian sovereignty, or state sovereignty, is a principle in international law that each state has exclusive sovereignty over its territory. The principle underlies the modern international system of sovereign states and is enshrined in the ...

" established the current international legal order characterized by independent sovereign entities known as "nation state

A nation state is a political unit where the state and nation are congruent. It is a more precise concept than "country", since a country does not need to have a predominant ethnic group.

A nation, in the sense of a common ethnicity, may i ...

s", which have equality of sovereignty regardless of size and power, defined primarily by the inviolability of borders and non-interference in the domestic affairs of sovereign states. From this period onward, the concept of the nation-state evolved rapidly, and with it the development of complex relations that required predictable, widely accepted rules and guidelines. The idea of nationalism

Nationalism is an idea and movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, nationalism tends to promote the interests of a particular nation (as in a in-group and out-group, group of peo ...

, in which people began to see themselves as citizens of a particular group with a distinct national identity, further solidified the concept and formation of nation-states.

Elements of the naturalist and positivist schools became synthesised, most notably by German philosopher Christian Wolff (1679–1754) and Swiss jurist Emerich de Vattel

Emer (Emmerich) de Vattel ( 25 April 171428 December 1767) was an international lawyer. He was born in Couvet in the Principality of Neuchâtel (now a canton part of Switzerland but part of Prussia at the time) in 1714 and died in 1767. He was l ...

(1714–67), both of whom sought a middle-ground approach in international law. During the 18th century, the positivist tradition gained broader acceptance, although the concept of natural rights remained influential in international politics, particularly through the republican revolutions of the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

and France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

. Not until the 20th century would natural rights gain further salience in international law.

Several legal systems developed in Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

, including the codified systems of continental European states known as civil law, and English common law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, be ...

, which is based on decisions by judges and not by written codes. Other areas around the world developed differing legal systems, with the Chinese legal tradition dating back more than four thousand years, although at the end of the 19th century, there was still no written code for civil proceedings in China.

Until the mid-19th century, relations between states were dictated mostly by treaties, agreements between states to behave in a certain way, unenforceable except by force, and nonbinding except as matters of honor and faithfulness. One of the first instruments of modern international law was the Lieber Code

The Lieber Code of April 24, 1863, issued as General Orders No. 100, Adjutant General's Office, 1863, was an instruction signed by U.S. President Abraham Lincoln to the Union forces of the United States during the American Civil War that dictated h ...

of 1863, which governed the conduct of U.S. forces during the U.S. Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by states t ...

, and is considered to be the first written recitation of the rules and articles of war adhered to by all civilized nations. This led to the first prosecution for war crimes, in which a Confederate commandant was tried and hanged for holding prisoners of war in cruel and depraved conditions at Andersonville, Georgia. In the years that followed, other states subscribed to limitations of their conduct, and numerous other treaties and bodies were created to regulate the conduct of states towards one another, including the Permanent Court of Arbitration

The Permanent Court of Arbitration (PCA) is a non-UN intergovernmental organization located in The Hague, Netherlands. Unlike a judicial court in the traditional sense, the PCA provides services of arbitral tribunal to resolve disputes that aris ...

in 1899, and the Hague

The Hague ( ; nl, Den Haag or ) is a city and municipality of the Netherlands, situated on the west coast facing the North Sea. The Hague is the country's administrative centre and its seat of government, and while the official capital of ...

and Geneva Conventions

upright=1.15, Original document in single pages, 1864

The Geneva Conventions are four treaties, and three additional protocols, that establish international legal standards for humanitarian treatment in war. The singular term ''Geneva Conven ...

, the first of which was passed in 1864. The concept of sovereignty was spread throughout the world by European powers, which had established colonies and spheres of influences over virtually every society. Positivism reached its peak in the late 19th century and its influence began to wane following the unprecedented bloodshed of the

The concept of sovereignty was spread throughout the world by European powers, which had established colonies and spheres of influences over virtually every society. Positivism reached its peak in the late 19th century and its influence began to wane following the unprecedented bloodshed of the First World War

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, which spurred the creation of international organisations such as the League of Nations

The League of Nations (french: link=no, Société des Nations ) was the first worldwide intergovernmental organisation whose principal mission was to maintain world peace. It was founded on 10 January 1920 by the Paris Peace Conference that ...

, founded in 1919 to safeguard peace and security. International law began to incorporate more naturalist notions such as self determination

The right of a people to self-determination is a cardinal principle in modern international law (commonly regarded as a '' jus cogens'' rule), binding, as such, on the United Nations as authoritative interpretation of the Charter's norms. It sta ...

and human rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

. The World War II, Second World War accelerated this development, leading to the establishment of the United Nations, whose Charter of the United Nations, Charter enshrined principles such as nonaggression, nonintervention, and collective security. A more robust international legal order followed, which was buttressed by institutions such as the International Court of Justice and the United Nations Security Council, and by multilateral agreements such as the Genocide Convention. The International Law Commission (ILC) was established in 1947 to help develop, codify, and strengthen international law

Having become geographically international through the colonial expansion of the European powers, international law became truly international in the 1960s and 1970s, when rapid Decolonization, decolonisation across the world resulted in the establishment of scores of newly independent states. The varying political and economic interests and needs of these states, along with their diverse cultural backgrounds, infused the hitherto European-dominated principles and practices of international law with new influences. A flurry of institutions, ranging from the World Health Organization, World Health Organisation to the World Trade Organization, World Trade Organisation, furthered the development of a stable, predictable legal order with rules governing virtually every domain. The phenomenon of Globalization, globalisation, which has led to the rapid integration of the world in economic, political, and even cultural terms, presents one of the greatest challenges to devising a truly international legal system.

Sources of international law

Sources of international law have been influenced by a range of political and legal theories. During the 20th century, it was recognized by legal legal positivism, positivists that a sovereign state could limit its authority to act by consenting to an agreement according to the contract principle ''pacta sunt servanda''. This consensual view of international law was reflected in the 1920 Statute of the Permanent Court of International Justice, and remains preserved in Article 7 of the ICJ Statute. Thesources of international law

International law, also known as "law of nations", refers to the body of rules which regulate the conduct of sovereign states in their relations with one another. Sources of international law include treaties, international customs, general ...

applied by the community of nations are listed under Article 38 of the Statute of the International Court of Justice, which is considered authoritative in this regard:

# International treaties and conventions;

# International custom as derived from the "general practice" of states; and

# General legal principles "recognized by civilized nations".

Additionally, judicial decisions and the teachings of prominent international law scholars may be applied as "subsidiary means for the determination of rules of law".

Many scholars agree that the fact that the sources are arranged sequentially suggests an implicit hierarchy of sources. However, the language of Article 38 does not explicitly hold such a hierarchy, and the decisions of the international courts and tribunals do not support such a strict hierarchy. By contrast, Article 21 of the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court clearly defines a hierarchy of applicable law (or sources of international law).

Treaties

International treaty law comprises obligations expressly and voluntarily accepted by states between themselves in treaty, treaties. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties defines a treaty as follows:"treaty" means an international agreement concluded between States in written form and governed by international law, whether embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments and whatever its particular designationThis definition has led case-law to define a treaty as an international agreement that meets the following criteria: # Criterion 1: Requirement of an agreement, meetings of wills (''concours de volonté'') # Criterion 2: Requirement of being concluded between subjects of international law: this criterion excludes agreements signed between States and private corporations, such as Production sharing agreement, Production Sharing Agreements. In the 1952 ''United Kingdom v Iran'' case, the ICJ did not have jurisdiction for a dispute over the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company being nationalized as the dispute emerged from an alleged breach of contract between a private company and a State. # Criterion 3: Requirement to be governed by international law: any agreement governed by any domestic law will not be considered a treaty. # Criterion 4: No requirement of instrument: A treaty can be embodied in a single instrument or in two or more related instruments. This is best exemplified in exchange of letters - (''échange de lettres''). For example, if France sends a letter to the United States to say, increase their contribution in the budget of the North Atlantic Alliance, and the US accepts the commitment, a treaty can be said to have emerged from the exchange. # Criterion 5: No requirement of designation: the designation of the treaty, whether it is a "convention", "pact" or "agreement" has no impact on the qualification of said agreement as being a treaty. # Unwritten Criterion: requirement for the agreement to produce legal effects: this unwritten criterion is meant to exclude agreements which fulfill the above-listed conditions, but are not meant to produce legal effects, such as Memorandum of understanding, Memoranda of Understanding. Where there are disputes about the exact meaning and application of national laws, it is the responsibility of the courts to decide what the law means. In international law, interpretation is within the domain of the states concerned, but may also be conferred on judicial bodies such as the International Court of Justice, by the terms of the treaties or by consent of the parties. Thus, while it is generally the responsibility of states to interpret the law for themselves, the processes of diplomacy and availability of supra-national judicial organs routinely provide assistance to that end. The Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties, which codifies several bedrock principles of treaty interpretation, holds that a treaty "shall be interpreted in good faith in accordance with the ordinary meaning to be given to the terms of the treaty in their context and in the light of its object and purpose." This represents a compromise between three different theories of interpretation: * The textual approach, a restrictive interpretation that looks to the "ordinary meaning" of the text, assigning considerable weight to the actual text. * The subjective approach, which takes into consideration factors such as the ideas behind the treaty, the context of the treaty's creation, and what the drafters intended. * The effective approach, which interprets a treaty "in the light of its object and purpose", i.e. based on what best suits the goal of the treaty. The foregoing are general rules of interpretation, and do no preclude the application of specific rules for particular areas of international law. *''Ambatielos case, Greece v United Kingdom'' [1952

ICJ 1

ICJ had no jurisdiction to hear a dispute between the UK government and a private Greek businessman under the terms of a treaty. *''United Kingdom v Iran'' [1952

ICJ 2

the ICJ did not have jurisdiction for a dispute over the Anglo-Iranian Oil Company being nationalized. *''Oil Platforms case (Islamic Republic of Iran v United States of America)'' [2003

ICJ 4

rejected dispute over damage to ships which hit a mine.

International custom

Customary international law is derived from the consistent practice of States accompanied by ''opinio juris'', i.e. the conviction of states that the consistent practice is required by a legal obligation. Judgments of international tribunals as well as scholarly works have traditionally been looked to as persuasive sources for custom in addition to direct evidence of state behavior. Attempts to codify customary international law picked up momentum after the Second World War with the formation of the International Law Commission (ILC) under the aegis of the United Nations, UN. Codified customary law is made the binding interpretation of the underlying custom by agreement through treaty. For states not party to such treaties, the work of the ILC may still be accepted as custom applying to those states. General principles of law are those commonly recognized by the major legal systems of the world. Certain norms of international law achieve the binding force of peremptory norms (''jus cogens'') as to include all states with no permissible derogations. *''Asylum case, Colombia v Perú'' (1950), recognizing custom as a source of international law, but a practice of giving asylum was not part of it. *''Belgium v Spain'' (1970), finding that only the state where a corporation is incorporated (not where its major shareholders reside) has standing to bring an action for damages for economic loss.Statehood and responsibility

International law establishes the framework and the criteria for identifying Sovereign state, states as the fundamental actors in the international legal system. As the existence of a state presupposes control and jurisdiction over territory, international law deals with the acquisition of territory, state immunity and the legal responsibility of states in their conduct with each other. International law is similarly concerned with the treatment of individuals within state boundaries. There is thus a comprehensive regime dealing with group rights, the treatment of alien (law), aliens, the rights of refugees, Transnational crime, international crimes, nationality problems, andhuman rights

Human rights are Morality, moral principles or Social norm, normsJames Nickel, with assistance from Thomas Pogge, M.B.E. Smith, and Leif Wenar, 13 December 2013, Stanford Encyclopedia of PhilosophyHuman Rights Retrieved 14 August 2014 for ce ...

generally. It further includes the important functions of the maintenance of international peace and security, arms control, the pacific settlement of disputes and the regulation of the use of force in international relations. Even when the law is not able to stop the outbreak of war, it has developed principles to govern the conduct of hostilities and the treatment of prisoners of war, prisoners. International law is also used to govern issues relating to the global environment, the global commons such as international waters and outer space, global communications, and International trade, world trade.

In theory, all states are Sovereignty, sovereign and equal. As a result of the notion of sovereignty, the value and authority of international law is dependent upon the voluntary participation of states in its formulation, observance, and enforcement. Although there may be exceptions, it is thought by many international academics that most states enter into legal commitments with other states out of enlightened self-interest rather than adherence to a body of law that is higher than their own. As D. W. Greig notes, "international law cannot exist in isolation from the political factors operating in the sphere of international relations".

Traditionally, sovereign states and the Holy See#Status in international law, Holy See were the sole subjects of international law. With the proliferation of international organizations over the last century, they have in some cases been recognized as relevant parties as well. Recent interpretations of international human rights law

International human rights law (IHRL) is the body of international law designed to promote human rights on social, regional, and domestic levels. As a form of international law, international human rights law are primarily made up of treaties, a ...

, international humanitarian law

International humanitarian law (IHL), also referred to as the laws of armed conflict, is the law that regulates the conduct of war ('' jus in bello''). It is a branch of international law that seeks to limit the effects of armed conflict by pro ...

, and international trade law (e.g., North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) Chapter 11 actions) have been inclusive of corporations, and even of certain individuals.

The conflict between international law and national sovereignty is subject to vigorous debate and dispute in academia, diplomacy, and politics. Indeed, there is a growing trend toward judging a state's domestic actions in the light of international law and standards. Numerous people now view the nation-state as the primary unit of international affairs and believe that only states may choose to enter into commitments under international law voluntarily and that they have the right to follow their own counsel when it comes to the interpretation of their commitments. Certain scholars and political leaders feel that these modern developments endanger nation-states by taking power away from state governments and ceding it to international bodies such as the U.N. and the World Bank, argue that international law has evolved to a point where it exists separately from the mere consent of states, and discern a legislative and judicial process to international law that parallels such processes within domestic law. This especially occurs when states violate or deviate from the expected standards of conduct adhered to by all civilized nations.

A number of states place emphasis on the principle of territorial sovereignty, thus seeing states as having free rein over their internal affairs. Other states oppose this view. One group of opponents of this point of view, including many Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a Continent#Subcontinents, subcontinent of Eurasia ...

nations, maintain that all civilized nations have certain norms of conduct expected of them, including the prohibition of genocide, slavery and the slave trade, war of aggression, wars of aggression, torture, and piracy, and that violation of these universal norms represents a crime, not only against the individual victims, but against humanity as a whole. States and individuals who subscribe to this view opine that, in the case of the individual responsible for violation of international law, he "is become, like the piracy, pirate and the slave trader before him, ''hostis humani generis'', an enemy of all mankind", and thus subject to prosecution in a fair trial before any fundamentally just tribunal, through the exercise of universal jurisdiction.

Though European democracies tend to support broad, universalistic interpretations of international law, many other democracies have differing views on international law. Several democracies, including India, Israel and the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, take a flexible, eclectic approach, recognizing aspects of international law such as territorial rights as universal, regarding other aspects as arising from treaty or custom, and viewing certain aspects as not being subjects of international law at all. Democracy, Democracies in the developing world, due to their past colonial histories, often insist on non-interference in their internal affairs, particularly regarding human rights standards or their peculiar institutions, but often strongly support international law at the bilateral and multilateral levels, such as in the United Nations, and especially regarding the use of force, disarmament obligations, and the terms of the Charter of the United Nations, UN Charter.

*''Case Concerning United States Diplomatic and Consular Staff in Tehran'' [1980ICJ 1

*''Democratic Republic of the Congo v Belgium'' [2002

ICJ 1

Territory and the sea

The law of the sea is the area of international law concerning the principles and rules by which states and other entities interact in maritime matters. It encompasses areas and issues such as navigational rights, sea mineral rights, and coastal waters jurisdiction. The law of the sea is distinct from admiralty law (also known as maritime law), which concerns relations and conduct at sea by private entities. The United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), concluded in 1982 and coming into force in 1994, is generally accepted as a codification of customary international law of the sea. *Territorial dispute *''Libya v Chad'' [1994ICJ 1

*''United Kingdom v Norway'' [1951

ICJ 3

the Fisheries case, concerning the limits of Norway's jurisdiction over neighboring waters *''Peru v Chile'' (2014) dispute over international waters. *''Bakassi case'' [2002

ICJ 2

between Nigeria and Cameroon *''Burkina Faso-Niger frontier dispute case'' (2013) *United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea *''Corfu Channel Case'' [1949

ICJ 1

UK sues Albania for damage to ships in international waters. First ICJ decision. *''France v United Kingdom'' [1953

ICJ 3

*''Germany v Denmark and the Netherlands'' [1969

ICJ 1

successful claim for a greater share of the North Sea continental shelf by Germany. The ICJ held that the matter ought to be settled, not according to strict legal rules, but through applying equitable principles. *''Case concerning maritime delimitation in the Black Sea (Romania v Ukraine)'' [2009

ICJ 3

International organizations

*United Nations *World Trade Organization *International Labour Organization *NATO *European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

*G7 and G20

*OPEC

*Organisation of Islamic Conference, Organisation of Islamic Cooperation

*Food and Agriculture Organization

*World Health Organization

Social and economic policy

*''Netherlands v Sweden'' [1958ICJ 8

Sweden had jurisdiction over its guardianship policy, meaning that its laws overrode a conflicting guardianship order of the Netherlands. *''Liechtenstein v Guatemala'' [1955

ICJ 1

the recognition of Mr Nottebohm's nationality, connected to diplomatic protection. *''Italy v France, United Kingdom and United States'' [1954

ICJ 2

Human rights

*Universal Declaration of Human Rights *''Croatia–Serbia genocide case'' (2014) ongoing claims over genocide. *''Bosnia and Herzegovina v Serbia and Montenegro'' [2007ICJ 2

*''Case Concerning Barcelona Traction, Light, and Power Company, Ltd'' [1970

ICJ 1

Labor law

*International Labour Organization, International Labor Organization *ILO Conventions *Declaration of Philadelphia of 1944 *Declaration on Fundamental Principles and Rights at Work of 1998 *United Nations Convention on the Protection of the Rights of All Migrant Workers and Members of Their Families * the Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Racial Discrimination 1965 *Convention on the Elimination of All Forms of Discrimination Against Women 1981); * the Convention on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities 2008Development and finance

*Bretton Woods Conference *World Bank *International Monetary FundEnvironmental law

*Kyoto ProtocolTrade

*World Trade Organization *Trans-Pacific Partnership (TPP): The TPP is a proposed free trade agreement among 11 Pacific Rim economies, focusing on tariff reductions. It was the centerpiece of President Barack Obama's strategic pivot to Asia. Before President Donald Trump, Donald J. Trump withdrew the United States in 2017, the TPP was set to become the world's largest free trade deal, covering 40 percent of the global economy. *Regional Comprehensive Economic Partnership (RCEP): The RCEP is a free trade agreement between the Asia-Pacific nations of Australia, Brunei, Cambodia,China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

, Indonesia, Japan, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, New Zealand, the Philippines, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand, and Vietnam. It includes the 10 ASEAN members plus 6 ASEAN foreign partners. The 16 nations signed the agreement on 15 November 2020, via tele-conference. The deal excludes the US, which withdrew from a rival Asia-Pacific trade pact in 2017. RCEP will connect about 30% of the world's people and output and, in the right political context, will generate significant gains. RCEP aims to create an integrated market with 16 countries, making it easier for products and services of each of these countries to be available across this region. The negotiations are focused on the following: Trade in goods and services, investment, intellectual property, dispute settlement, e-commerce, Small and medium-sized enterprises, small and medium enterprises, and economic cooperation.

Conflict and force

War and armed conflict

*''Nicaragua v. United States'' [1986ICJ 1

*''International Court of Justice advisory opinion on the Legality of the Threat or Use of Nuclear Weapons''

Humanitarian law

*First Geneva Convention of 1949, Amelioration of the Condition of the Wounded and Sick in Armed Forces in the Field, (first adopted in 1864) *Second Geneva Convention of 1949, Amelioration of the Condition of Wounded, Sick and Shipwrecked Members of Armed Forces at Sea (first adopted in 1906) *Third Geneva Convention of 1949, Treatment of Prisoners of War, adopted in 1929, following from the Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907. *Fourth Geneva Convention of 1949, Protection of Civilian Persons in Time of War.International criminal law

* International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda * International Criminal Tribunal for the Former YugoslaviaCourts and enforcement

Since international law has no established compulsory judicial system for the settlement of disputes or a coercive penal system, it is not as straightforward as managing breaches within a domestic legal system. However, there are means by which breaches are brought to the attention of the international community and some means for resolution. For example, there are judicial or quasi-judicial tribunals in international law in certain areas such as trade and human rights. The formation of the United Nations, for example, created a means for the world community to enforce international law upon members that violate its charter through the Security Council. Since international law exists in a legal environment without an overarching "sovereign" (i.e., an external power able and willing to compel compliance with international norms), "enforcement" of international law is very different from in the domestic context. In many cases, enforcement takes on Ronald Coase, Coasian characteristics, where the norm is self-enforcing. In other cases, defection from the norm can pose a real risk, particularly if the international environment is changing. When this happens, and if enough states (or enough powerful states) continually ignore a particular aspect of international law, the norm may actually change according to concepts of customary international law. For example, prior to World War I, unrestricted submarine warfare was considered a violation of international law and ostensibly the casus belli for the United States' declaration of war against Germany. By World War II, however, the practice was so widespread that during the Nuremberg trials, the charges against German Admiral Karl Dönitz for ordering unrestricted submarine warfare were dropped, notwithstanding that the activity constituted a clear violation of the Second London Naval Treaty of 1936.Domestic enforcement

Apart from a state's natural inclination to uphold certain norms, the force of international law comes from the pressure that states put upon one another to behave consistently and to honor their obligations. As with any system of law, many violations of international law obligations are overlooked. If addressed, it may be throughdiplomacy

Diplomacy comprises spoken or written communication by representatives of states (such as leaders and diplomats) intended to influence events in the international system.Ronald Peter Barston, ''Modern diplomacy'', Pearson Education, 2006, p. 1 ...

and the consequences upon an offending state's reputation, submission to international judicial determination, arbitration, sanctions or force including war. Though violations may be common in fact, states try to avoid the appearance of having disregarded international obligations. States may also unilaterally adopt sanctions against one another such as the severance of economic or diplomatic ties, or through reciprocal action. In some cases, domestic courts may render judgment against a foreign state (the realm of private international law) for an injury, though this is a complicated area of law where international law intersects with domestic law.

It is implicit in the Westphalian system of nation-states, and explicitly recognized under Article 51 of the Charter of the United Nations, that all states have the inherent right to individual and collective self-defense if an armed attack occurs against them. Article 51 of the UN Charter guarantees the right of states to defend themselves until (and unless) the Security Council takes measures to keep the peace.

International bodies

As a "deliberative, policymaking and representative organ", the United Nations General Assembly "is empowered to make recommendations"; it can neither codify international law nor make binding resolutions. Merely internal resolutions, such as budgetary matters, may be binding on the operation of the General Assembly itself. Violations of the UN Charter by members of the United Nations may be raised by the aggrieved state in the General Assembly for debate. United Nations General Assembly resolution, General Assembly resolutions are generally non-binding towards member states, but through its adoption of the United Nations General Assembly Resolution 377, "Uniting for Peace" resolution (A/RES/377 A), of 3 November 1950, the Assembly declared that it had the power to authorize the use of force, under the terms of the UN Charter, in cases of breaches of the peace or acts of aggression, provided that the Security Council, owing to the negative vote of a permanent member, fails to act to address the situation. The Assembly also declared, by its adoption of United Nations General Assembly Resolution 377, resolution 377 A, that it could call for other collective measures—such as economic and diplomatic sanctions—in situations constituting the milder "threat to the Peace". The Uniting for Peace resolution was initiated by the United States in 1950, shortly after the outbreak of the Korean War, as a means of circumventing possible future Soviet vetoes in the United Nations Security Council, Security Council. The legal role of the resolution is clear, given that the General Assembly can neither issue binding resolutions nor codify law. It was never argued by the "Joint Seven-Powers" that put forward the draft resolution, during the corresponding discussions, that it in any way afforded the Assembly new powers. Instead, they argued that the resolution simply declared what the Assembly's powers already were, according to the UN Charter, in the case of a dead-locked Security Council. The Soviet Union was the only permanent member of the Security Council to vote against the Charter interpretations that were made recommendation by the Assembly's adoption of resolution 377 A. Alleged violations of the Charter can also be raised by states in the Security Council. The Security Council could subsequently pass resolutions under Chapter VI of the UN Charter to recommend the "Pacific Resolution of Disputes." Such resolutions are not binding under international law, though they usually are expressive of the council's convictions. In rare cases, the Security Council can adopt resolutions under Chapter VII of the UN Charter, related to "threats to Peace, Breaches of the Peace and Acts of Aggression," which are legally binding under international law, and can be followed up with economic sanctions, military action, and similar uses of force through the auspices of the United Nations. It has been argued that resolutions passed outside of Chapter VII can also be binding; the legal basis for that is the council's broad powers under Article 24(2), which states that "in discharging these duties (exercise of primary responsibility in international peace and security), it shall act in accordance with the Purposes and Principles of the United Nations". The mandatory nature of such resolutions was upheld by the International Court of Justice (ICJ) in its advisory opinion on Namibia. The binding nature of such resolutions can be deduced from an interpretation of their language and intent. States can also, upon mutual consent, submit disputes for arbitration by the International Court of Justice, located in The Hague, Netherlands. The judgments given by the court in these cases are binding, although it possesses no means to enforce its rulings. The Court may give an advisory opinion on any legal question at the request of whatever body may be authorized by or in accordance with the Charter of the United Nations to make such a request. Some of the advisory cases brought before the court have been controversial with respect to the court's competence and jurisdiction. Often enormously complicated matters, ICJ cases (of which there have been less than 150 since the court was created from the Permanent Court of International Justice in 1945) can stretch on for years and generally involve thousands of pages of pleadings, evidence, and the world's leading specialist international lawyers. As of November 2019, there are 16 cases pending at the ICJ. Decisions made through other means of arbitration may be binding or non-binding depending on the nature of the arbitration agreement, whereas decisions resulting from contentious cases argued before the ICJ are always binding on the involved states. Though states (or increasingly, international organizations) are usually the only ones with standing to address a violation of international law, some treaties, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights have an optional Protocol (treaty), protocol that allows individuals who have had their rights violated by member states to petition the international Human Rights Committee. Investment treaties commonly and routinely provide for enforcement by individuals or investing entities. and commercial agreements of foreigners with sovereign governments may be enforced on the international plane.International courts