Indro Montanelli on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Indro Alessandro Raffaello Schizogene Montanelli (; 22 April 1909 – 22 July 2001) was an Italian journalist, historian and writer. He was one of the fifty

Indro Montanelli was born in

Indro Montanelli was born in

When Mussolini invaded

When Mussolini invaded

The stand Montanelli took against Fascism led him to his first serious conflicts with the Italian authorities. His Fascist Party (PNF:Partito Nazionale Fascista in Italian) membership was revoked thereafter and Montanelli did nothing to regain this important document which at the time conferred a series of important privileges on its holders; the country was after all dominated by Mussolini's Fascist movement. So to avoid the worst, in 1938, the then minister of culture, Giuseppe Bottai, offered Montanelli the job of director of the Institute of Culture in

The stand Montanelli took against Fascism led him to his first serious conflicts with the Italian authorities. His Fascist Party (PNF:Partito Nazionale Fascista in Italian) membership was revoked thereafter and Montanelli did nothing to regain this important document which at the time conferred a series of important privileges on its holders; the country was after all dominated by Mussolini's Fascist movement. So to avoid the worst, in 1938, the then minister of culture, Giuseppe Bottai, offered Montanelli the job of director of the Institute of Culture in

Commander, First Class, of the Order of the Lion of Finland

Commander, First Class, of the Order of the Lion of Finland

While working as a journalist for the fascist magazine ''Civiltà Fascista'', Montanelli had argued that soldiers should under no circumstances fraternise with black people, at least "until they had been given a culture" . In June 2020, a statue of Indro Montanelli in Milan was vandalized by activists, in the context of the

While working as a journalist for the fascist magazine ''Civiltà Fascista'', Montanelli had argued that soldiers should under no circumstances fraternise with black people, at least "until they had been given a culture" . In June 2020, a statue of Indro Montanelli in Milan was vandalized by activists, in the context of the

World Press Freedom Heroes

International Press Institute World Press Freedom Heroes are individuals who have been recognized by the Vienna-based International Press Institute for "significant contributions to the maintenance of press freedom and freedom of expression" and "i ...

according to the International Press Institute

International Press Institute (IPI) is a global organisation dedicated to the promotion and protection of press freedom and the improvement of journalism practices. The institution was founded by 34 editors from 15 countries at Columbia University ...

.

A volunteer for the Second Italo-Ethiopian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

and an admirer of Benito Mussolini's dictatorship, Montanelli had a change of heart in 1943, and joined the liberal resistance group Giustizia e Libertà

Giustizia e Libertà (; en, Justice and Freedom) was an Italian anti-fascist resistance movement, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The mov ...

but was discovered and arrested along with his wife by Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

authorities in 1944. Sentenced to death, he was able to flee to Switzerland the day before his scheduled execution by firing squad thanks to a secret service double-agent.

After the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposi ...

, Montanelli for many decades distinguished himself as a staunch conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

columnist, and in 1977 the terrorist group Brigate Rosse

The Red Brigades ( it, Brigate Rosse , often abbreviated BR) was a far-left Marxist–Leninist armed organization operating as a terrorist and guerrilla group based in Italy responsible for numerous violent incidents, including the abduction ...

tried to assassinate him. He was also a popular novelist and historian, especially remembered for his monumental '' Storia d'Italia'' (''History of Italy'') in 22 volumes. He worked as editor of Silvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; born 29 September 1936) is an Italian media tycoon and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy in four governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a member of the Chamber of Deputies f ...

-owned newspaper ''il Giornale

''il Giornale'' ( en, The Newspaper) is an Italian language daily newspaper published in Milan, Italy.

History and profile

The newspaper was founded in 1974 by the journalist Indro Montanelli, together with the colleagues Enzo Bettiza, Ferenc ...

'' for many years but was opposed to Berlusconi's political ambitions, and quit as editor of ''il Giornale'' in 1994.

In the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests, Montanelli came under scrutiny for his racist attitudes and actions. While working at the fascist magazine ''Civiltà Fascista'', Montanelli wrote many articles expressing racist ideas, declaring the superiority of the white race

White is a racialized classification of people and a skin color specifier, generally used for people of European origin, although the definition can vary depending on context, nationality, and point of view.

Description of populations as ...

, and supporting colonialist

Colonialism is a practice or policy of control by one people or power over other people or areas, often by establishing colonies and generally with the aim of economic dominance. In the process of colonisation, colonisers may impose their relig ...

ideals. While stationed in Italian Ethiopia

Italian Ethiopia ( it, Etiopia italiana), also known as the Italian Empire of Ethiopia, was the territory of the Ethiopian Empire which was occupied by Italy for approximately five years. Italian Ethiopia was not an administrative entity, but the ...

during the Ethiopian War, Montanelli married a 12-year old Eritrean girl (as it was custom for the institution of the ""), who later chose to marry an Eritrean officer of his platoon. Since through modern-day values this is considered rape, protestors defaced a statue erected for him in Milan in the wake of the BLM movement and demanded it be removed.

Biography

Early life

Indro Montanelli was born in

Indro Montanelli was born in Fucecchio

Fucecchio () is a town and ''comune'' of the Metropolitan City of Florence in the Italian region of Tuscany. The main economical resources of the city are the leather industries, shoes industry and other manufacturing activities, although in the ...

, near Florence

Florence ( ; it, Firenze ) is a city in Central Italy and the capital city of the Tuscany Regions of Italy, region. It is the most populated city in Tuscany, with 383,083 inhabitants in 2016, and over 1,520,000 in its metropolitan area.Bilan ...

, on April 22, 1909. His father, Sestilio Montanelli, was a high-school philosophy teacher and his mother, Maddalena Doddoli, the daughter of a rich cotton merchant. The name "Indro" was chosen by his father after the Hindu god Indra.

Montanelli obtained a law degree from the University of Florence in 1930, with a thesis on the electoral reform of Benito Mussolini's fascist regime. Allegedly, in this thesis, he maintained that rather than a reform it amounted to the abolition of elections. According to him, it was during his permanence in Grenoble

lat, Gratianopolis

, commune status = Prefecture and commune

, image = Panorama grenoble.png

, image size =

, caption = From upper left: Panorama of the city, Grenoble’s cable cars, place Saint- ...

, while he was taking language lessons, that he realised that his true vocation was that of a journalist.

Early journalistic career

Montanelli began his journalistic career by writing for the fascist newspaper ''Il Selvaggio'' ("The Savage"), then directed byMino Maccari

Mino Maccari (24 November 1898 – 16 June 1989) was an Italian painter. His work was part of the painting event in the art competition at the 1948 Summer Olympics

The 1948 Summer Olympics (officially the Games of the XIV Olympiad an ...

, and in 1932 for the ''Universale'', a magazine published only once fortnightly and which offered no pay. Montanelli admitted that in those days he saw in fascism the hope of a movement that could potentially create an Italian national conscience that would have resolved the social and economic differences between the north and the south. This enthusiasm for the fascist movement began to wane when in 1935 Mussolini ordered the suppression of the ''Universale'' along with other magazines and newspapers that expressed critical opinions on the nature of Fascism.

But it was in 1934, in Paris that Montanelli began to write for the crime pages of the daily newspaper '' Paris-Soir'', then as foreign correspondent in Norway (where he fished for cod for a bit), and later in Canada (where he ended up working on a farm in Alberta).

From there he began a collaboration with Webb Miller

Webb Colby Miller (born 1943) is a professor in the Department of Biology and the Department of Computer Science and Engineering at The Pennsylvania State University.

Education

Miller attended Whitman College, and received his Ph.D. in mathemati ...

of the United Press

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 20t ...

in New York. While working for the United Press he learned to write for the lay public in an uncomplicated style that would distinguish him within the realm of Italian journalism. One lesson he took to heart from Miller was to "always write as if writing to a milkman from Ohio". This open and approachable style was something he never forgot and he'd often recall that very quote during his long life. Another memorable anecdote from Montanelli's time in the United States occurred while he was teaching a course. One of the students had asked him to explain the meaning of the essay that Montanelli had just read out. Montanelli told him he'd repeat it since he clearly didn't understand... Hitting the table, the red-faced student cut him off and angrily told him, as a matter of fact, that if he hadn't understood Montanelli's essay, then it was Montanelli who was the imbecile! nd needed to change it It was then that he realized that he, who had come from the authoritarian regime of fascist Italy, had just had a confrontation with democracy. During this time Montanelli conducted his first interview with a celebrity: Henry Ford

Henry Ford (July 30, 1863 – April 7, 1947) was an American industrialist, business magnate, founder of the Ford Motor Company, and chief developer of the assembly line technique of mass production. By creating the first automobile that ...

– who surprised him by admitting he did not have a driver's license. During the interview, surrounded by American art depicting pastoral and frontier subjects, Ford began to reverentially talk about the Founding Fathers. Looking at the decor, Montanelli astutely asked him how he felt about having destroyed their world. Puzzled, Ford asked what he meant. Undaunted, Montanelli pressed on that the automobile and Ford's revolutionary assembly line

An assembly line is a manufacturing process (often called a ''progressive assembly'') in which parts (usually interchangeable parts) are added as the semi-finished assembly moves from workstation to workstation where the parts are added in se ...

system had forever transformed the country. Ford looked shocked, and Montanelli realized that, like all geniuses, Ford hadn't had the slightest idea of what he'd really done.

Reporter in Abyssinia

When Mussolini invaded

When Mussolini invaded Abyssinia

The Ethiopian Empire (), also formerly known by the exonym Abyssinia, or just simply known as Ethiopia (; Amharic and Tigrinya: ኢትዮጵያ , , Oromo: Itoophiyaa, Somali: Itoobiya, Afar: ''Itiyoophiyaa''), was an empire that historica ...

in 1935 with the intent of making Italy an empire (Second Italo–Abyssinian War

The Second Italo-Ethiopian War, also referred to as the Second Italo-Abyssinian War, was a war of aggression which was fought between Italy and Ethiopia from October 1935 to February 1937. In Ethiopia it is often referred to simply as the Itali ...

), Montanelli immediately abandoned his collaboration with the United Press

United Press International (UPI) is an American international news agency whose newswires, photo, news film, and audio services provided news material to thousands of newspapers, magazines, radio and television stations for most of the 20t ...

and became a voluntary conscript for this war. Aged 23, Montanelli was put in charge of a 100-strong army of local men. "It was a beautiful two years" he later said. He said he believed then that this was the chance for Italy to bring civilization to the 'savage' world of Africa. While stationed in east Africa, Montanelli bought and married a 12-year-old Bilen child to act as his sex slave, a common practice of Italian soldiers in Abyssinia.

Montanelli began writing about the war to his father who – without Montanelli's knowledge – sent the letters to one of the most famous journalists of those times, Ugo Ojetti, who published them regularly on the most prestigious Italian newspaper, '' Il Corriere della Sera''.

Reporter during the Spanish Civil War

On his return from Abyssinia, Montanelli became foreign correspondent in Spain for the daily newspaper ''Il Messaggero'', where he experienced theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, link ...

on the side of Francisco Franco's troops. In this period he shared a room with Kim Philby

Harold Adrian Russell "Kim" Philby (1 January 191211 May 1988) was a British intelligence officer and a double agent for the Soviet Union. In 1963 he was revealed to be a member of the Cambridge Five, a spy ring which had divulged British secr ...

, who, decades later, would reveal himself to the world as one of the greatest Soviet mole spies that ever existed. One day he disappeared. Years later Montanelli received a mysterious note saying: "Thanks for everything. Including your socks". It was Philby. After the capture of the city of Santander

Santander may refer to:

Places

* Santander, Spain, a port city and capital of the autonomous community of Cantabria, Spain

* Santander Department, a department of Colombia

* Santander State, former state of Colombia

* Santander de Quilichao, a m ...

, Montanelli wrote that '(...) it had been a long military walk with only one enemy: the heat'. This judgement contrasted with the propaganda of the times that painted that 'battle' as a glorious bloodshed on the side of the Italian contingent. In fact the only casualty he noted, but never reported, by Montanelli was a single death in the Alpini regiment caused by a mule kick that threw the unfortunate trooper down into a dry river bed. For this article he was repatriated, tried and expelled from the Fascist party and from the official organization of Italian Journalists (known as the Albo dei Giornalisti in Italian). When, in the trial, he was asked why he had written such an unpatriotic article, he replied: "Show me a single casualty of that battle: because a battle without casualties is not a real battle!" The trial ended with a full absolution.

Journalistic activity during World War II

Eastern and Northern Europe

The stand Montanelli took against Fascism led him to his first serious conflicts with the Italian authorities. His Fascist Party (PNF:Partito Nazionale Fascista in Italian) membership was revoked thereafter and Montanelli did nothing to regain this important document which at the time conferred a series of important privileges on its holders; the country was after all dominated by Mussolini's Fascist movement. So to avoid the worst, in 1938, the then minister of culture, Giuseppe Bottai, offered Montanelli the job of director of the Institute of Culture in

The stand Montanelli took against Fascism led him to his first serious conflicts with the Italian authorities. His Fascist Party (PNF:Partito Nazionale Fascista in Italian) membership was revoked thereafter and Montanelli did nothing to regain this important document which at the time conferred a series of important privileges on its holders; the country was after all dominated by Mussolini's Fascist movement. So to avoid the worst, in 1938, the then minister of culture, Giuseppe Bottai, offered Montanelli the job of director of the Institute of Culture in Tallinn

Tallinn () is the most populous and capital city of Estonia. Situated on a bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, Tallinn has a population of 437,811 (as of 2022) and administratively lies in the Harju '' ...

, Estonia

Estonia, formally the Republic of Estonia, is a country by the Baltic Sea in Northern Europe. It is bordered to the north by the Gulf of Finland across from Finland, to the west by the sea across from Sweden, to the south by Latvia, a ...

, and lecturer in Italian at the University of Tartu

The University of Tartu (UT; et, Tartu Ülikool; la, Universitas Tartuensis) is a university in the city of Tartu in Estonia. It is the national university of Estonia. It is the only classical university in the country, and also its biggest ...

. In this period the then director of ''Il Corriere della Sera'', Aldo Borelli, asked Montanelli to engage in a 'collaboration' as foreign correspondent (he could not be employed as journalist, because this had been forbidden by the fascist regime). Montanelli began to correspond for this newspaper from Estonia and Albania (during the Italian annexation of this country).

On 1 September 1939 Germany invaded Poland. Montanelli was sent to report from the front in a Mercedes accompanied by German state functionaries. In the vicinity to the city of Grudziądz

Grudziądz ( la, Graudentum, Graudentium, german: Graudenz) is a city in northern Poland, with 92,552 inhabitants (2021). Located on the Vistula River, it lies within the Kuyavian-Pomeranian Voivodeship and is the fourth-largest city in its prov ...

the car was stopped by a convoy of German tanks. On one of these stood Hitler himself, but a few feet from Montanelli. When Hitler was told that the only person in casual clothes was Italian, he jumped out of the tank and eyeing Montanelli like a madman, began a ten-minute hysterical speech followed by military salute and exit. Albert Speer, who had also been in the convoy with fellow artist Arno Breker, corroborated the story in 1979. Apart from this episode – which Montanelli was forbidden to report – there had been little to report because the invasion of Poland was completed so rapidly that it was over within weeks. It was allegedly him who reported about the Skirmish of Krojanty and created a myth from it.

Montanelli was not welcome in Italy, and decided to move to Lithuania. The joint German-Russian invasion of Poland instinctively told him that more was brewing on the Soviet Union border. His instinct was correct because shortly after his arrival in Kaunas – the seat of Lithuanian government – the Soviet Union issued its ultimatum to the Baltic Republics. At this point Montanelli continued to travel towards Tallinn

Tallinn () is the most populous and capital city of Estonia. Situated on a bay in north Estonia, on the shore of the Gulf of Finland of the Baltic Sea, Tallinn has a population of 437,811 (as of 2022) and administratively lies in the Harju '' ...

as it was his wish to see the last of a free and democratic Estonia, which was soon invaded by Soviet Union. At this point, Montanelli was not popular in Italy, nor Germany because of his pro-Estonian and pro-Polish articles and had been expelled by the Soviet Union for being a foreigner. So he was forced by the events to cross the Baltic sea and reach Helsinki

Helsinki ( or ; ; sv, Helsingfors, ) is the capital, primate, and most populous city of Finland. Located on the shore of the Gulf of Finland, it is the seat of the region of Uusimaa in southern Finland, and has a population of . The city ...

.

In Finland

Finland ( fi, Suomi ; sv, Finland ), officially the Republic of Finland (; ), is a Nordic country in Northern Europe. It shares land borders with Sweden to the northwest, Norway to the north, and Russia to the east, with the Gulf of B ...

Montanelli began writing articles about the Lapps and the reindeer, although this was not for long as Molotov had made requests on the Finnish government for the annexation of part of the Finnish land to the Soviet Union. The Finnish delegation, headed by Paasikivi

Juho Kusti Paasikivi (; 27 November 1870 – 14 December 1956) was the seventh president of Finland (1946–1956). Representing the Finnish Party until its dissolution in 1918 and then the National Coalition Party, he also served as Prime Minister ...

, had refused to give in to these requests and on their return it was clear that war was in the air. Montanelli was not able to write about the details of the talks between the Soviet and Finnish delegations, as they were shrouded in strict secrecy, although he was able to interview Paasikivi, who was happy to fill him in on everything except for the content of the talks.

Throughout the so-called Winter War

The Winter War,, sv, Vinterkriget, rus, Зи́мняя война́, r=Zimnyaya voyna. The names Soviet–Finnish War 1939–1940 (russian: link=no, Сове́тско-финская война́ 1939–1940) and Soviet–Finland War 1 ...

which ensued, Montanelli wrote hotly pro-Finnish articles both from the front and from bomb-stricken Helsinki writing about the almost mythical enterprises of the battle of Tolvajärvi

The Battle of Tolvajärvi ( tol.va.jær.vi fi, Tolvajärven–Ägläjärven taistelu, russian: Битва при Толваярви) was fought on 12 December 1939 between Finland and the Soviet Union. It was the first large offensive victory ...

, and of men like captain Pajakka who with 200 Lapps successfully confronted 40,000 Russians in the region of Petsamo Petsamo may refer to:

* Petsamo Province, a province of Finland from 1921 to 1922

* Petsamo, Tampere, a district in Tampere, Finland

* Pechengsky District, Russia, formerly known as Petsamo

* Pechenga (urban-type settlement), Murmansk Oblast, Russi ...

. Back in Italy Montanelli's stories had been followed with great enthusiasm by the public, but not so enthusiastic was the response of the fascist leaders who were committed to an alliance with the Soviet Union. When Borelli, director of ''Il Corriere della Sera'', had been ordered to censor Montanelli's articles, he had had the courage to reply that "thanks to his articles the ''Corriere'' increased its sales from 500,000 to 900,000 copies: are you going to reimburse me?". When the Winter War was over, and the non-aggression pact was signed between the Soviet Union and Finland, Montanelli was personally thanked by the elusive Mannerheim

Baron Carl Gustaf Emil Mannerheim (, ; 4 June 1867 – 27 January 1951) was a Finnish military leader and statesman. He served as the military leader of the Whites in the Finnish Civil War of 1918, as Regent of Finland (1918–1919), as comm ...

himself, for writing in favour of the Finnish cause.

Invasion of Norway

Before his return to Italy Montanelli witnessed theinvasion of Norway

Norway, officially the Kingdom of Norway, is a Nordic country in Northern Europe, the mainland territory of which comprises the western and northernmost portion of the Scandinavian Peninsula. The remote Arctic island of Jan Mayen and the ...

, and was arrested by the German army for his hostility towards the German-Italian alliance. He escaped with the help of his friend Vidkun Quisling

Vidkun Abraham Lauritz Jonssøn Quisling (, ; 18 July 1887 – 24 October 1945) was a Norwegian military officer, politician and Nazi collaborator who nominally list of heads of government of Norway, headed the government of Norway during t ...

, and made a run for the north of the country where the English and the French were disembarking their troops at Narvik. He was met by the one-eyed, one-armed Major Carton de Wiart who explained that there were no more than 10,000 Allied troops in Norway – many of them not even trained for battle. Nobody seemed to know where their garrison was. The British wanted to go inland and attack the Germans, but the French wanted to stay put and consolidate their positions. After having seen the clockwork invasion of Poland by the German troops, Montanelli found this disarray a worrying sight. When the Germans began bombing these positions the Allies were forced to embark once again and beat a hasty withdrawal to England.

Balkans and Greece

With Italy's entrance in the war (June 1940), Montanelli was sent to France and the Balkans; then he was assigned the responsibility of following the Italian military campaign from Greece and Albania as correspondent. Here, he recounted to have written little: "I remained at that front various months, writing almost nothing, a small reason was because I fell ill with typhus and a huge one because I refused to push as a glorious military campaign the quaking pummeling that we caught down there." An article published on 12 September 1940 issue of ''Panoram''a was considered "defeatist" by the censors of Minculpop (Ministry of Popular Culture

The Ministry of Popular Culture ( it, Ministero della Cultura Popolare, commonly abbreviated to MinCulPop) was a ministry of the Italian government from 1937 to 1944.

History

It was established by the Fascist government in 1922 as the ''Press ...

), who in turn ordered the closure of the periodical.

Arrested and sentenced to death

After witnessing war and destruction in the Balkans, and the disastrousItalian invasion of Greece

Italian(s) may refer to:

* Anything of, from, or related to the people of Italy over the centuries

** Italians, an ethnic group or simply a citizen of the Italian Republic or Italian Kingdom

** Italian language, a Romance language

*** Regional Ita ...

, Montanelli decided to join the Italian resistance movement against the fascist regime, by joining the liberal Giustizia e Libertà

Giustizia e Libertà (; en, Justice and Freedom) was an Italian anti-fascist resistance movement, active from 1929 to 1945.James D. Wilkinson (1981). ''The Intellectual Resistance Movement in Europe''. Harvard University Press. p. 224. The mov ...

clandestine group. Here he met socialist leader Sandro Pertini

Alessandro "Sandro" Pertini (; 25 September 1896 – 24 February 1990) was an Italian socialist politician who served as the president of Italy from 1978 to 1985.

Early life

Born in Stella ( Province of Savona) as the son of a wealthy landow ...

(who would later become president of Italy from 1978 to 1985).

He was eventually once again captured by the Germans, tried and sentenced to death. In the Milanese prison of San Vittore he met Mike Bongiorno

Michael Nicholas Salvatore Bongiorno (; May 26, 1924 – September 8, 2009) was an Italian-American television host. After a few experiences in the US, he started working on RAI in the 1950s and was considered to be the most popular host in Ital ...

, who would later become one of the most famous Italian television personalities. In prison he also made the acquaintance of General Della Rovere, who was said to have been arrested while on a secret mission on behalf of the Allies. In fact, this man was a thief called Giovanni Bertoni, a spy for the Germans. But Bertoni was so taken in by the military character he was playing that he refused to relay any information to his German captors and was executed like a real enemy official. After the war Montanelli dedicated a book to this incident (''Il generale Della Rovere'', 1959, later turned into an award-winning movie directed by Roberto Rossellini

Roberto Gastone Zeffiro Rossellini (8 May 1906 – 3 June 1977) was an Italian film director, producer, and screenwriter. He was one of the most prominent directors of the Italian neorealist cinema, contributing to the movement with films such ...

and starring Vittorio De Sica

Vittorio De Sica ( , ; 7 July 1901 – 13 November 1974) was an Italian film director and actor, a leading figure in the neorealist movement.

Four of the films he directed won Academy Awards: ''Sciuscià'' and ''Bicycle Thieves'' (honorary) ...

).

Salvation came at the end of 1944 with the help of unknown conspirators who arranged for his transfer to a prison in Verona. The transfer was then transformed into a dash for the Swiss border. The identity of these conspirators remained a mystery until decades later, when it appeared that it had been the result of collusion by several agencies. Among them, Marshall Mannerheim allegedly put pressure on his German allies ("You are executing a gentleman" he said to von Falkenhorst, the commander of the German troops stationed in Finland) resulting in Berlin's opening of an inquiry.

In 1945 while hiding in Switzerland, he published the novel ''Drei Kreuze'' (''Three Crosses''), later appeared in Italian with the title ''Qui non-riposano'' (''Here they do not rest''). Inspired by Thornton Wilder

Thornton Niven Wilder (April 17, 1897 – December 7, 1975) was an American playwright and novelist. He won three Pulitzer Prizes — for the novel '' The Bridge of San Luis Rey'' and for the plays ''Our Town'' and '' The Skin of Our Teeth'' — ...

's ''The Bridge of San Luis Rey'', the story begins on 17 September 1944 when a Val d'Ossola priest buries three unknown corpses and commemorates them with three anonymous crosses.

Career after World War II

Throughout the post-war years, Montanelli retained an idiosyncratic and particularly undiplomatic style, even when this made him very unpopular among his peers and employers. This is well illustrated in his book ''La stecca nel coro'' (which translates as "The false note in the chorus" with the meaning of "Going against the current") which is a list of leading articles he composed between 1974 and 1994. After the war, Montanelli resumed his career at ''Il Corriere della Sera'', famously authoring deeply sympathetic articles fromHungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Pannonian Basin, Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the ...

, during the 1956 Hungarian Revolution

The Hungarian Revolution of 1956 (23 October – 10 November 1956; hu, 1956-os forradalom), also known as the Hungarian Uprising, was a countrywide revolution against the government of the Hungarian People's Republic (1949–1989) and the Hung ...

. His first hand reportages inspired him to write the play, '' I sogni muoiono all'alba'' (Dreams Die at Dawn), later adapted to film. In 1959, Montanelli interviewed for the first time in history a Pope, office at the time held by Pope John XXIII

Pope John XXIII ( la, Ioannes XXIII; it, Giovanni XXIII; born Angelo Giuseppe Roncalli, ; 25 November 18813 June 1963) was head of the Catholic Church and sovereign of the Vatican City State from 28 October 1958 until his death in June 19 ...

; the Pope declared that he picked Montanelli exactly because he was an atheist and not a Catholic sympathizer. From the mid-1960s, after the death of the newspaper's owners, Mario and Vittorio Crespi, and the serious illness of the third brother, Aldo, the ownership of the newspaper passed upon Aldo's daughter, Giulia Maria. Under her tight control (earning her Montanelli's moniker the czarina

Tsarina or tsaritsa (also spelled ''csarina'' or ''csaricsa'', ''tzarina'' or ''tzaritza'', or ''czarina'' or ''czaricza''; bg, царица, tsaritsa; sr, / ; russian: царица, tsaritsa) is the title of a female autocratic ruler (mona ...

), the daily took a sudden turn to the left. This new launch took place in 1972 with the abrupt dismissal of director Giovanni Spadolini. Montanelli expressed a cutting indictment of the procedure in an interview on ''L'espresso

''L'Espresso'' () is an Italian weekly news magazine. It is one of the two most prominent Italian weeklies; the other is '' Panorama''. Since 2022 it has been published by BFC Media.

History and profile

One of Italy's foremost newsmagazines, ' ...

'', declaring: "A director is not sent away like a thieving house-servant" and, turning to the Crespi family, he branded their "authoritarian, bullying junta ways that they have chosen in order to impose their decision".

Founding of ''il Giornale'' and assassination attempt

After breaking with ''Il Corriere della Sera'' he founded and directed a new conservative daily, ''Il Giornale

''il Giornale'' ( en, The Newspaper) is an Italian language daily newspaper published in Milan, Italy.

History and profile

The newspaper was founded in 1974 by the journalist Indro Montanelli, together with the colleagues Enzo Bettiza, Ferenc ...

'', from 1973 to 1994, together with Enzo Bettiza

Vincenzo Bettiza (7 June 1927 – 28 July 2017) was a Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslavian-born Dalmatian Italians, Italian novelist, journalist and politician.

Biography

Bettiza was born in Dalmatia, then part of Kingdom of Yugoslavia, Yugoslavia ...

.

On 2 September 1977, Montanelli was shot four times in the legs by a two-man commando of the Red Brigades

The Red Brigades ( it, Brigate Rosse , often abbreviated BR) was a far-left Marxist–Leninist armed organization operating as a terrorist and guerrilla group based in Italy responsible for numerous violent incidents, including the abduction ...

, outside the Milanese head-office of ''Il Corriere della Sera''. His friend and surgeon was amazed at how "four shots could hit those ong, thinchicken legs of his and still completely miss a major artery or nerve bundle". He credited his indoctrination as a child in the Balilla

''Balilla'' was the nickname of Giovanni Battista Perasso (1735–1781), a Genoese boy who started the revolt of 1746 against the Habsburg forces that occupied the city in the War of the Austrian Succession by throwing a stone at an Austrian ...

fascist youth and its mantra, "to die on your feet", for saving his life. He maintained that had he not held on to the railing during the incident the fourth shot would have surely hit him in the stomach. In his typical ironical and satirical vein he also thanked ''Il Duce

( , ) is an Italian title, derived from the Latin word 'leader', and a cognate of ''duke''. National Fascist Party leader Benito Mussolini was identified by Fascists as ('The Leader') of the movement since the birth of the in 1919. In 192 ...

''. In a petty instance of insult to injury ''Il Corriere della Sera'' dedicated an article to the incident omitting his name from the title ("Milan ..journalist kneecapped").

Quarrel with Berlusconi and final years

WhenSilvio Berlusconi

Silvio Berlusconi ( ; ; born 29 September 1936) is an Italian media tycoon and politician who served as Prime Minister of Italy in four governments from 1994 to 1995, 2001 to 2006 and 2008 to 2011. He was a member of the Chamber of Deputies f ...

, who since 1977 had held the majority of shares in ''Il Giornale'', entered politics with the founding of a new populist political party, Forza Italia, Montanelli came under heavy pressure to switch his editorial line to a position favourable to Berlusconi. Montanelli never hid his bad opinion of Berlusconi: "He lies as he breathes", the journalist declared. In the end, protesting his independence, he founded a new daily, for which he resurrected the name '' La Voce'' ("The Voice"), which had belonged to a renowned newspaper run by Giuseppe Prezzolini Giuseppe Prezzolini (27 January 1882 – 16 July 1982) was an Italian literary critic, journalist, editor and writer. He later became an American citizen.

Biography

Prezzolini was born in Perugia in January 1882, to Tuscan parents from Siena, Luig ...

. ''La Voce'', which had garnered a devoted but limited readership, folded after about a year, and Montanelli returned to ''Il Corriere della Sera''. In 1994, Montanelli was awarded the International Editor of the Year Award {{no footnotes, date=January 2019

''International Editor of the Year Award'' is a prize awarded yearly to journalists and press editors outside the United States by World Press Review ( Worldpress.org) magazine.

The award has been presented by Wor ...

from the ''World Press Review

''World Press '' (Worldpress.org) is an independent, nonpartisan New York based magazine founded in 1974 and initially published by Stanley Foundation and Teri Schure, with an online edition which was launched in 1997.

The headquarters of the ...

''.

From 1995 to 2001 he was the chief letters editor of ''Il Corriere della Sera'', answering a letter a day on a page of the newspaper known as "La Stanza di Montanelli" ("Montanelli's Room"). Montanelli spent his last years vigorously opposing Silvio Berlusconi's politics. He was mentor to a significant group of colleagues, followers and students including Mario Cervi, Marco Travaglio

Marco Travaglio (; born 13 October 1964) is an Italian investigative journalist, writer and opinion leader, editor of the independent journal ''Il Fatto Quotidiano''.

Biography

Travaglio was born in Turin and earned a degree in history from th ...

, Paolo Mieli

Paolo Mieli (born 25 February 1949) is an Italian journalist who has been editor of Italy's leading newspaper, ''Corriere della Sera''.

Born in Milan, Mieli debuted as journalist at 18 for ''L'Espresso'', where he remained for some 20 years. As ...

, Roberto Ridolfi, Andrea Claudio Galluzzo, Beppe Severgnini

Giuseppe "Beppe" Severgnini (; born 26 December 1956) is an Italian journalist, essayist and columnist.

Biography

Born in Crema, Severgnini graduated in law at the University of Pavia. His father was a public notary.

His career in journal ...

and Roberto Gervaso.

He died on 22 July 2001 at the ''La Madonnina'' clinic in Milan. The following day, ''Il Corriere della Sera'' published a letter on its front page: "Indro Montanelli's farewell to his readers."

Awards and decorations

Commander, First Class, of the Order of the Lion of Finland

Commander, First Class, of the Order of the Lion of Finland

Legacy

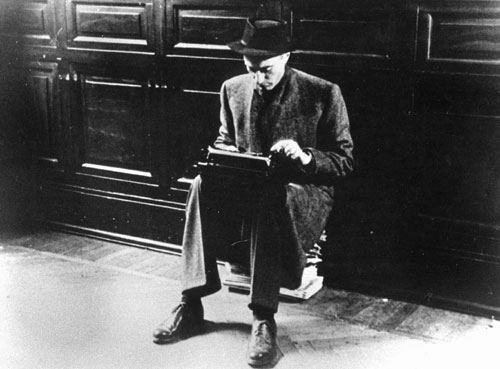

Montanelli had been nicknamed "The prince of journalism" by his own colleagues while he was still alive, gaining large esteem and consent even from liberals and left-oriented journalists; Enzo Biagi, Giorgio Bocca, Aldo Grasso, Gianfrancesco Zincone and many others considered him a master of the profession and his objectivity and attention to history as a model to teach and replicate. He said in his letters "If you lack the holy fire inside, if you're not made for this work, if you lack a natural appendice with a typewriter... it's pointless to do this job". He left for posterity a number of first-person reportages and interviews with important historical figures, including De Gaulle, Mussolini, Pope John XXII and Churchill. While working as a journalist for the fascist magazine ''Civiltà Fascista'', Montanelli had argued that soldiers should under no circumstances fraternise with black people, at least "until they had been given a culture" . In June 2020, a statue of Indro Montanelli in Milan was vandalized by activists, in the context of the

While working as a journalist for the fascist magazine ''Civiltà Fascista'', Montanelli had argued that soldiers should under no circumstances fraternise with black people, at least "until they had been given a culture" . In June 2020, a statue of Indro Montanelli in Milan was vandalized by activists, in the context of the Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter (abbreviated BLM) is a decentralized political and social movement that seeks to highlight racism, discrimination, and racial inequality experienced by black people. Its primary concerns are incidents of police br ...

movement. This was done to highlight the fact that, when aged 24 and working in Italian Ethiopia

Italian Ethiopia ( it, Etiopia italiana), also known as the Italian Empire of Ethiopia, was the territory of the Ethiopian Empire which was occupied by Italy for approximately five years. Italian Ethiopia was not an administrative entity, but the ...

(former Abyssinia), he married a young girl by buying her from her family, as was customary among locals, and in his interviews affectionately referred to her as "a little docile animal". In a 1969 episode of the talk show ''L'ora della verità'' (''The hour of the truth''), Montanelli told host Gianni Bisiach of his child-bride: "I think I chose well. She was a beautiful girl of 12 years," adding, "I'm sorry. But in Africa it's different." During the interview, his account was interrupted by a question from the feminist and journalist Elvira Banotti

Elvira Banotti (17 July 1933 in Asmara – 2 March 2014 in Lavinio) was an Italian journalist and writer of Italian Eritrean descent, feminist activist and founder of the ''Rivolta Femminile'' group in the early 1970s.

Biography

She was born in ...

, who asked him how he could justify his marriage to a child, since marriage in Europe to a 12-year-old girl would be considered abhorrent; Montanelli replied that "in Abyssinia that's how it works", and that "at 12 years they normally marry, they are women already." The relationship has never been described as violent or nonconsensual, and both the family and the girl have always been reported as agreeing to it; the girl herself still showed affection towards Montanelli years after their separation by naming her first-born child Indro. The marriage falls into what was known as the madamato practice, a relationship between Italian men and local women which was commonplace in the then Italian colonies.

The very historian that first researched Italian war crimes in Ethiopia, Angelo Del Boca, retained great esteem for Montanelli and even defended his marriage with the young girl. "It makes no sense o call him a racist and rapist, the historian said, "it was an act of integration, especially since Montanelli kept a good relationship with her for years." "At the time, but maybe even nowadays, it was normal to marry women of that age in Africa; it was initially encouraged as an element of fraternization."

Milan's mayor, Giuseppe Sala, refused to remove the statue, arguing that "lives should be judged in their totality", while recognising his dismay at the lightness of the way Montanelli spoke about his actions in Abyssinia.

References

Bibliography

* Alessandro Scurani, ''Montanelli. Pro e contro'', Milano, Letture, 1971. * Gennaro Cesaro, ''Dossier Montanelli'', Napoli, Fausto Fiorentino, 1974. * Gastone Geron, ''Montanelli. Il coraggio di dare la notizia'', Milano, La Sorgente, 1975. * Marcello Staglieno, ''Il Giornale 1974-1980'', Milano, Società europea di edizioni, 1980. * Tommaso Giglio, ''Un certo Montanelli'', Milano, Sperling & Kupfer, 1981. * Claudio Mauri, ''Montanelli l'eretico'', Milano, SugarCo, 1982. * Marcello Staglieno, ''Indro Montanelli'', Milano, Sidalm-Comune di Milano, 1982. * Tullio Ciarrapico (a cura di), ''Indro Montanelli. Una vita per la cultura. Letteratura: giornalismo'', Roma, Ente Fiuggi, 1985. * Donato Mutarelli, ''Montanelli visto da vicino'', Milano, Ediforum, 1992. * Ettore Baistrocchi, ''Lettere a Montanelli'', Roma, Palazzotti, 1993. * Piero Malvolti, ''Indro Montanelli'', Fucecchio, Edizioni dell'Erba, 1993. *Mario Cervi

Mario Cervi (25 March 1921 – 17 November 2015) was an Italian essayist and journalist.

Born in Crema, Lombardy, Cervi started his career as a journalist in 1945 collaborating with the newspaper ''Corriere della Sera'' as a foreign reporter. In ...

e Gian Galeazzo Biazzi Vergani

Gian is a masculine Italian given name. It is a variant of Gianni and is likewise used as a diminutive of Giovanni, the Italian form of John.

In Italian, any name including Giovanni can be contracted to Gian, particularly in combination with other ...

, ''I vent'anni del "Giornale" di Montanelli. 25 giugno 1974 - 12 gennaio 1994'', Milano, Rizzoli, 1994, .

* Giancarlo Mazzuca, '' Indro Montanelli: la mia "Voce". Storia di un sogno impossibile raccontata da Giancarlo Mazzuca'', Milano, Sperling & Kupfer

Arnoldo Mondadori Editore () is the biggest publishing company in Italy.

History

The company was founded in 1907 in Ostiglia by 18-year-old Arnoldo Mondadori who began his publishing career with the publication of the magazine ''Luce!''. In 1 ...

, 1995, .

* Federico Orlando, ''Il sabato andavamo ad Arcore. La vera storia, documenti e ragioni, del divorzio tra Berlusconi e Montanelli'', Bergamo, Larus, 1995, .

* Marcello Staglieno, ''Il Novecento visto da Montanelli: l'eretico della destra italiana'', suppl. a "Lo Stato", Roma, 20 gennaio 1998.

* Marco Delpino, a cura di e con Paolo Riceputi, ''Indro Montanelli: un cittadino scomodo e un'analisi sulla stampa italiana'', Santa Margherita Ligure, Tigullio-Bacherontius, 1999.

* Federico Orlando, ''Fucilate Montanelli. Dall'assalto al «Giornale» alle elezioni del 13 maggio'', Roma, Editori Riuniti, 2001, .

* Marcello Staglieno, ''Montanelli. Novant'anni controcorrente'', Milano, Mondadori, 2001, .

* Giorgio Soavi Giorgio may refer to:

* Castel Giorgio, ''comune'' in Umbria, Italy

* Giorgio (name), an Italian given name and surname

* Giorgio Moroder, or Giorgio, Italian record producer

** ''Giorgio'' (album), an album by Giorgio Moroder

* "Giorgio" (son ...

, ''Indro. Due complici che si sono divertiti a vivere e a scrivere'', Collezione Il Cammeo n.388, Milano, Longanesi, 2002, .

* Gian Luca Mazzini, ''Montanelli mi ha detto. Avventure, aneddoti, ricordi del più grande giornalista italiano'', Rimini, Il Cerchio, 2002, .

* Giorgio Torelli, ''Il Padreterno e Montanelli'', Milano, Ancora, 2003, .

* Paolo Granzotto, ''Montanelli'', Bologna, il Mulino, 2004, .

* Marco Travaglio

Marco Travaglio (; born 13 October 1964) is an Italian investigative journalist, writer and opinion leader, editor of the independent journal ''Il Fatto Quotidiano''.

Biography

Travaglio was born in Turin and earned a degree in history from th ...

, ''Montanelli e il Cavaliere. Storia di un grande e di un piccolo uomo'', Prefazione di Enzo Biagi

Enzo Biagi (; 9 August 1920 – 6 November 2007) was an Italian journalist, writer and former partisan.

Life and career

Biagi was born in Lizzano in Belvedere, and began his career as a journalist in Bologna. In 1952, he worked on the screenpla ...

, Milano, Garzanti, 2004 ; Nuova edizione ampliata nella Collana Saggi, con un saggio introduttivo inedito dell'Autore, Milano, Garzanti, 2009, .

* Paolo Avanti e Alessandro Frigerio, ''A cercar la bella destra. I ragazzi di Montanelli'', Milano, Mursia, 2005, .

* Sandro Gerbi

Alessandro Gerbi, known as Sandro (born October 3, 1943 in Lima, Peru) is an Italian journalist, author of several biographies and books on Italian contemporary history.

Biography

Sandro Gerbi was born in Peru because his father Antonello (1 ...

e Raffaele Liucci, ''Lo stregone. La prima vita di Indro Montanelli'', Torino, Einaudi, 2006, .

* Renata Broggini, ''Passaggio in Svizzera. L'anno nascosto di Indro Montanelli'', Milano, Feltrinelli, 2007, .

* Federica Depaolis e Walter Scancarello (a cura di), ''Indro Montanelli. Bibliografia 1930-2006'', Pontedera, Bibliografia e Informazione, 2007, .

* Giancarlo Mazzuca, ''Testimoni del Novecento'', Bologna, Poligrafici Editoriale, 2008.

* Sandro Gerbi

Alessandro Gerbi, known as Sandro (born October 3, 1943 in Lima, Peru) is an Italian journalist, author of several biographies and books on Italian contemporary history.

Biography

Sandro Gerbi was born in Peru because his father Antonello (1 ...

e Raffaele Liucci, ''Montanelli l'anarchico borghese. La seconda vita 1958-2001'', Torino, Einaudi, 2009, .

* Giorgio Torelli, ''Non avrete altro Indro. Montanelli raccontato con nostalgia'', Milano, Ancora, 2009, .

* Iacopo Bottazzi, ''Montanelli Reporter. Da Addis Abeba a Zagabria in viaggio con un grande giornalista'', Roma-Reggio Emilia, Aliberti, 2011, .

* Federica De Paolis, ''Tra i libri di Indro: percorsi in cerca di una biblioteca d'autore'', Pontedera, Bibliografia e Informazione, 2013, .

* Sandro Gerbi

Alessandro Gerbi, known as Sandro (born October 3, 1943 in Lima, Peru) is an Italian journalist, author of several biographies and books on Italian contemporary history.

Biography

Sandro Gerbi was born in Peru because his father Antonello (1 ...

e Raffaele Liucci, ''Indro Montanelli. Una biografia (1909-2001)'', (nuova ed. aggiornata dei due volumi apparsi per Einaudi), Collana Saggistica, Milano, Hoepli

Hoepli Editore is an Italian publishing house and bookstore based in Milan founded in 1870 by Swiss bookseller Ulrico Hoepli. Born in 1847 in the village of Tuttwil (now part of Wängi, Canton Thurgau), at the age of 23 Hoepli moved to Milan to ...

, 2014, .

* Giancarlo Mazzuca, ''Indro Montanelli. Uno straniero in patria. Prefazione di Roberto Gervaso'', Collana Saggi, Cairo Publishing, 2015, .

*

* Alberto Mazzuca, ''Penne al vetriolo. I grandi giornalisti raccontano la prima Repubblica'', Bologna, Minerva, 2017, .

External links

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Montanelli, Indro 1909 births 2001 deaths People from Fucecchio 20th-century Italian novelists 20th-century Italian male writers Conservatism in Italy Cycling journalists Italian anti-communists Italian anti-fascists Italian fascists Italian newspaper founders Italian newspaper editors Italian male journalists Bancarella Prize winners Slave owners