In His Own Write on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''In His Own Write'' is a 1964

T'was custard time and as I

Snuffed at the haggie pie pie

The noodles ran about my plunk

Which rode my wrytle uncle drunk

...

From around the age of eight, Lennon spent much of his time drawing, inspired by cartoonist Ronald Searle's work in the

I peel the bagpipes for my wife

And cut all negroes' hair

As breathing is my very life

And stop I do not dare.

Visiting Lennon's

In 1963,

In 1963,

''In His Own Write'' received critical acclaim, with favourable reviews in London's ''

''In His Own Write'' received critical acclaim, with favourable reviews in London's ''

Past grisby trees and hulky builds

Past ratters and bradder sheep

...

Down hovey lanes and stoney claves

Down ricketts and stickly myth

In a fatty hebrew gurth

I wandered humply as a sock

To meet bad Bernie Smith In his book '' Can't Buy Me Love'', Jonathan Gould compares the poem "No Flies on Frank" to Lennon's 1967 song "

nonsense

Nonsense is a communication, via speech, writing, or any other symbolic system, that lacks any coherent meaning. Sometimes in ordinary usage, nonsense is synonymous with absurdity or the ridiculous

To be ridiculous is to be something which is ...

book by English musician John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer, songwriter, musician and peace activist who achieved worldwide fame as founder, co-songwriter, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of ...

. His first book, it consists of poems and short stories ranging from eight lines to three pages, as well as illustrations.

After Lennon showed journalist Michael Braun some of his writings and drawings, Braun in turn showed them to Tom Maschler

Thomas Michael Maschler (16 August 193315 October 2020) was a British publisher and writer. He was noted for instituting the Booker Prize for British, Irish and Commonwealth literature in 1969. He was involved in publishing the works of many not ...

of publisher Jonathan Cape

Jonathan Cape is a London publishing firm founded in 1921 by Herbert Jonathan Cape, who was head of the firm until his death in 1960.

Cape and his business partner Wren Howard set up the publishing house in 1921. They established a reputation ...

, who signed Lennon in January 1964. He wrote most of the content expressly for the book, though some stories and poems had been published years earlier in the Liverpool

Liverpool is a city and metropolitan borough in Merseyside, England. With a population of in 2019, it is the 10th largest English district by population and its metropolitan area is the fifth largest in the United Kingdom, with a popul ...

music publication ''Mersey Beat

''Mersey Beat'' was a music publication in Liverpool, England in the early 1960s. It was founded by Bill Harry, who was one of John Lennon's classmates at Liverpool Art College. The paper carried news about all the local Liverpool bands, and s ...

''. Lennon's writing style is informed by his interest in English writer Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequel ...

, while humorists Spike Milligan

Terence Alan "Spike" Milligan (16 April 1918 – 27 February 2002) was an Irish actor, comedian, writer, musician, poet, and playwright. The son of an English mother and Irish father, he was born in British Raj, British Colonial India, where h ...

and "Professor" Stanley Unwin inspired his sense of humour. His illustrations imitate the style of cartoonist James Thurber. Many of the book's pieces consist of private meanings and in-joke

An in-joke, also known as an inside joke or a private joke, is a joke whose humour is understandable only to members of an ingroup; that is, people who are ''in'' a particular social group, occupation, or other community of shared interest. It i ...

s, while also referencing Lennon's interest in physical abnormalities and expressing his anti-authority sentiments.

The book was both a critical and commercial success, selling around 300,000 copies in Britain. Reviewers praised it for its imaginative use of wordplay

Word play or wordplay (also: play-on-words) is a literary technique and a form of wit in which words used become the main subject of the work, primarily for the purpose of intended effect or amusement. Examples of word play include puns, phone ...

and favourably compared it to the later works of James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

, though Lennon was unfamiliar with him. Later commentators have discussed the book's prose in relation to Lennon's songwriting, both in how it differed from his contemporary writing and in how it anticipates his later work, heard in songs like " Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" and " I Am the Walrus". Released amidst Beatlemania

Beatlemania was the fanaticism surrounding the English rock band the Beatles in the 1960s. The group's popularity grew in the United Kingdom throughout 1963, propelled by the singles "Please Please Me", "From Me to You" and "She Loves You". By ...

, its publication reinforced perceptions of Lennon as "the smart one" of the Beatles, and helped to further legitimise the place of pop music

Pop music is a genre of popular music that originated in its modern form during the mid-1950s in the United States and the United Kingdom. The terms ''popular music'' and ''pop music'' are often used interchangeably, although the former describe ...

ians in society.

Since its release, the book has been translated into several languages. In 1965, Lennon released another book of nonsense literature, '' A Spaniard in the Works''. He abandoned plans for a third collection and did not publish any other books in his lifetime. Victor Spinetti

Vittorio Giorgio Andre "Victor" Spinetti (2 September 1929 – 19 June 2012) was a Welsh actor, author, poet, and raconteur. He appeared in dozens of films and stage plays throughout his 50-year career, including the three 1960s Beatles films ' ...

and Adrienne Kennedy adapted his two books into a one-act play, ''The Lennon Play: In His Own Write'', produced by the National Theatre Company

The Royal National Theatre in London, commonly known as the National Theatre (NT), is one of the United Kingdom's three most prominent publicly funded performing arts venues, alongside the Royal Shakespeare Company and the Royal Opera House. In ...

and first performed in June 1968 to mixed reviews.

Background

Earliest influences

John Lennon

John Winston Ono Lennon (born John Winston Lennon; 9 October 19408 December 1980) was an English singer, songwriter, musician and peace activist who achieved worldwide fame as founder, co-songwriter, co-lead vocalist and rhythm guitarist of ...

was artistic as a child, though unfocused on his schooling. He was mostly raised by his aunt Mimi Smith

Mary Elizabeth "Mimi" Smith (''née'' Stanley; 24 April 1906 – 6 December 1991) was a maternal aunt and the parental guardian of the English musician John Lennon. Mimi Stanley was born in Toxteth, Liverpool, England

Liverpool is ...

, an avid reader who helped shape the literary inclinations of both Lennon and his step-siblings. Answering a questionnaire in 1965 about which books made the largest impression on him before the age of eleven, he identified Lewis Carroll

Charles Lutwidge Dodgson (; 27 January 1832 – 14 January 1898), better known by his pen name Lewis Carroll, was an English author, poet and mathematician. His most notable works are ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' (1865) and its sequel ...

's nonsense

Nonsense is a communication, via speech, writing, or any other symbolic system, that lacks any coherent meaning. Sometimes in ordinary usage, nonsense is synonymous with absurdity or the ridiculous

To be ridiculous is to be something which is ...

works '' Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and ''Through the Looking-Glass

''Through the Looking-Glass, and What Alice Found There'' (also known as ''Alice Through the Looking-Glass'' or simply ''Through the Looking-Glass'') is a novel published on 27 December 1871 (though indicated as 1872) by Lewis Carroll and the ...

'', as well as Kenneth Grahame

Kenneth Grahame ( ; 8 March 1859 – 6 July 1932) was a British writer born in Edinburgh, Scotland. He is most famous for ''The Wind in the Willows'' (1908), a classic of children's literature, as well as ''The Reluctant Dragon (short story), T ...

's children's book ''The Wind in the Willows

''The Wind in the Willows'' is a children's novel by the British novelist Kenneth Grahame, first published in 1908. It details the story of Mole, Ratty, and Badger as they try to help Mr. Toad, after he becomes obsessed with motorcars and gets ...

''. He added: "These books made a great impact and their influence will last for the rest of my life". He reread Carroll's books at least once a year, being intrigued by the use of wordplay

Word play or wordplay (also: play-on-words) is a literary technique and a form of wit in which words used become the main subject of the work, primarily for the purpose of intended effect or amusement. Examples of word play include puns, phone ...

in pieces like " Jabberwocky". His childhood friend Pete Shotton remembered Lennon reciting the poem "at least a few hundred times", and that, "from a very early age, John's ultimate ambition was to one day 'write an ''Alice'' himself". Lennon's first ever poem, "The Land of the Lunapots", was a fourteen-line piece written in the style of "Jabberwocky", using Carrollian words like "wyrtle" and "graftiens". Where Carroll's poem opens Twas brillig, and the...", Lennon's begins:St Trinian's School

''St Trinian's'' is a British gag cartoon comic strip series, created and drawn by Ronald Searle from 1946 until 1952. The cartoons all centre on a boarding school for girls, where the teachers are sadists and the girls are juvenile delinquents. ...

cartoon strips. He later enjoyed the illustrations of cartoonist James Thurber and began imitating his style around the age of fifteen. Uninterested in fine art

In European academic traditions, fine art is developed primarily for aesthetics or creative expression, distinguishing it from decorative art or applied art, which also has to serve some practical function, such as pottery or most metalwork ...

and unable to create realistic likenesses, he enjoyed doodling and drawing witty cartoons, usually made with either a black pen or a fountain pen

A fountain pen is a writing instrument which uses a metal nib to apply a water-based ink to paper. It is distinguished from earlier dip pens by using an internal reservoir to hold ink, eliminating the need to repeatedly dip the pen in an inkw ...

with black ink. Filling his school notebooks with vignettes, poetry and cartoons, he drew inspiration from British humorists such as Spike Milligan

Terence Alan "Spike" Milligan (16 April 1918 – 27 February 2002) was an Irish actor, comedian, writer, musician, poet, and playwright. The son of an English mother and Irish father, he was born in British Raj, British Colonial India, where h ...

and "Professor" Stanley Unwin, including Milligan's radio comedy programme ''The Goon Show

''The Goon Show'' is a British radio comedy programme, originally produced and broadcast by the BBC Home Service from 1951 to 1960, with occasional repeats on the BBC Light Programme. The first series, broadcast from 28 May to 20 September 19 ...

''. He admired the programme's unique humour, characterised by attacks on establishment figures, surreal humour and punning wordplay, later writing that it was "the only proof that the WORLD was insane". Lennon collected his work in a school exercise book dubbed the ''Daily Howl'', later described by Lennon's bandmate George Harrison

George Harrison (25 February 1943 – 29 November 2001) was an English musician and singer-songwriter who achieved international fame as the lead guitarist of the Beatles. Sometimes called "the quiet Beatle", Harrison embraced Indian c ...

as "jokes and avant-garde

The avant-garde (; In 'advance guard' or ' vanguard', literally 'fore-guard') is a person or work that is experimental, radical, or unorthodox with respect to art, culture, or society.John Picchione, The New Avant-garde in Italy: Theoretical ...

poetry". Made in the style of a newspaper, its cartoons and ads featured wordplay and gags, such as a column reporting: "Our late editor is dead, he died of death, which killed him".

Despite Lennon's love of literature, he was a chronic misspeller, saying in a 1968 interview that he "never got the idea of spelling", finding it less important than conveying an idea or story. Beatles historian Mark Lewisohn raises the possibility that Lennon had dyslexia

Dyslexia, also known until the 1960s as word blindness, is a disorder characterized by reading below the expected level for one's age. Different people are affected to different degrees. Problems may include difficulties in spelling words, r ...

– a condition that often went undiagnosed in the 1940s and 1950s – but counters that he exhibited no other related symptoms. Lennon's mother, Julia Lennon

Julia Lennon (''née'' Stanley; 12 March 1914 – 15 July 1958) was the mother of English musician John Lennon, who was born during her marriage to Alfred Lennon. After complaints to Liverpool's Social Services by her eldest sister, Mimi Sm ...

, similarly wrote with uncertain spelling and displayed weak grammar in her writing. American professor James Sauceda contends that Unwin's use of fractured English was the foremost influence on Lennon's writing style, and in a 1980 interview with ''Playboy

''Playboy'' is an American men's lifestyle and entertainment magazine, formerly in print and currently online. It was founded in Chicago in 1953, by Hugh Hefner and his associates, and funded in part by a $1,000 loan from Hefner's mother.

K ...

'', Lennon stated that the main influences on his writing "were always Lewis Carroll and ''The Goon Show'', a combination of that".

Art college and Bill Harry

Although most teachers at Quarry Bank High School for Boys were annoyed at Lennon's lack of focus, he impressed his English master, Philip Burnett, who suggested he go to art school at the Liverpool College of Art. In 2006, Burnett's wife, June Harry, recalled of Lennon's cartoons: "I was intrigued by what I saw. They weren't academic drawings but hilarious and quite disturbing cartoons." She continued: "Phil enjoyed John's slant on life. He told me, 'He's a bit of a one-off. He's bright enough, but not much apart from music and doing his cartoons interests him. Having failed his GCE "O" levels, Lennon was admitted into the Liverpool College of Art solely on the basis of his art portfolio. While attending the school he befriended fellow student Bill Harry in 1957. When Harry heard that Lennon wrote poetry he asked to see some, later recalling: "He was embarrassed at first... I got the impression that he felt that writing poetry was a bit effeminate because he had this tough macho image". After further pressing, Lennon relented and showed Harry a poem, who remembered it as "a rustic poem, it was pure British humour and comedy, and I loved it". Harry retrospectively stated that Lennon's writing style, especially his use ofmalapropism

A malapropism (also called a malaprop, acyrologia, or Dogberryism) is the mistaken use of an incorrect word in place of a word with a similar sound, resulting in a nonsensical, sometimes humorous utterance. An example is the statement attributed to ...

s, reminded him of Unwin. Harry described his poetry as displaying an "originality in its sheer lunacy", but found his sense of humour "absurdly cruel with its obsession with cripple

A cripple is a person or animal with a physical disability, particularly one who is unable to walk because of an injury or illness. The word was recorded as early as 950 AD, and derives from the Proto-Germanic ''krupilaz''. The German and Dutch w ...

s, spastics and torture".

After Harry started the Liverpool newspaper ''Mersey Beat

''Mersey Beat'' was a music publication in Liverpool, England in the early 1960s. It was founded by Bill Harry, who was one of John Lennon's classmates at Liverpool Art College. The paper carried news about all the local Liverpool bands, and s ...

'' in 1961, Lennon made occasional contributions. His column "Beatcomber", a reference to the "Beachcomber" column of the ''Daily Express

The ''Daily Express'' is a national daily United Kingdom middle-market newspaper printed in tabloid format. Published in London, it is the flagship of Express Newspapers, owned by publisher Reach plc. It was first published as a broadsheet i ...

'', included poems and short stories. He typed his early pieces with an Imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texa ...

Good Companion Model T typewriter

A typewriter is a mechanical or electromechanical machine for typing characters. Typically, a typewriter has an array of keys, and each one causes a different single character to be produced on paper by striking an inked ribbon selectivel ...

. By August 1962, his original typewriter was either broken or unavailable to him. He borrowed an acquaintance's, spurring him to write more prose and poetry. He enjoyed typewriters, but found that his slow typing left him unmotivated to write for long periods of time and so he focused on shorter pieces. He left keystroke errors uncorrected to add further wordplay. Excited about being in print, he brought 250 pieces to Harry, telling him he could publish whatever he wanted of them. Only two stories were published, "Small Sam" and "On Safairy with Whide Hunter", because Harry's fiancée Virginia accidentally threw out the other 248 during a move between offices. Harry later recalled that after telling him about the accident, Lennon broke down in tears.

Paul McCartney

Lennon's friend and bandmatePaul McCartney

Sir James Paul McCartney (born 18 June 1942) is an English singer, songwriter and musician who gained worldwide fame with the Beatles, for whom he played bass guitar and shared primary songwriting and lead vocal duties with John Lennon. One ...

also enjoyed ''Alice in Wonderland'', ''The Goon Show'' and the works of Thurber, and the two soon bonded through their mutual interests and similar senses of humour. Lennon impressed McCartney, who did not know anyone else that either owned a typewriter or wrote their own poetry. He found hilarious one of Lennon's earliest poems, "The Tale of Hermit Fred", especially its final lines:251 Menlove Avenue

251 Menlove Avenue is the childhood home of the Beatles' John Lennon. Located in the Woolton suburb of Liverpool. It was named Mendips after the Mendip Hills. The Grade II listed building is preserved by the National Trust.

Residence of John ...

home one day in July 1958, McCartney found him writing a poem and enjoyed the wordplay of lines like "a cup of teeth" and "in the early owls of the morecombe". Lennon let him help, with the two co-writing the poem "On Safairy with Whide Hunter", its title's origin likely the adventure serial ''White Hunter

White hunter is a literary term used for professional big game hunting, big game hunters of European or North American backgrounds who plied their trade in Africa, especially during the first half of the 20th century. The activity continues in t ...

''. Lewisohn suggests the renaming of the lead character at each appearance was probably Lennon's contribution, while lines that were likely McCartney's include: "Could be the Flying Docker on a case" and "No! But mable next week it will be my turn to beat the bus now standing at platforbe nine". He also suggests the character Jumble Jim was a reference to McCartney's father Jim McCartney. Lennon typically wrote his pieces by hand at home and would bring them when he and his band, the Beatles

The Beatles were an English Rock music, rock band, formed in Liverpool in 1960, that comprised John Lennon, Paul McCartney, George Harrison and Ringo Starr. They are regarded as the Cultural impact of the Beatles, most influential band of al ...

, were travelling in a car or van to a gig. Reading the pieces aloud, McCartney and Harrison would often make contributions of their own. Upon returning home, Lennon would type up the pieces, adding what he could remember of his friend's contributions.

Publication and content

In 1963,

In 1963, Tom Maschler

Thomas Michael Maschler (16 August 193315 October 2020) was a British publisher and writer. He was noted for instituting the Booker Prize for British, Irish and Commonwealth literature in 1969. He was involved in publishing the works of many not ...

, the literary director of Jonathan Cape

Jonathan Cape is a London publishing firm founded in 1921 by Herbert Jonathan Cape, who was head of the firm until his death in 1960.

Cape and his business partner Wren Howard set up the publishing house in 1921. They established a reputation ...

, commissioned American journalist Michael Braun to write a book about the Beatles. Braun began following the band during their Autumn 1963 UK Tour in preparation for his 1964 book '' Love Me Do: The Beatles' Progress''. Lennon showed Braun some of his writings and drawings, and Braun in turn showed them to Maschler, who recalled: "I thought they were wonderful and asked him who wrote them. When he told me John Lennon, I was immensely excited." At Braun's insistence, Maschler joined him and the band at Wimbledon Palais in London

London is the capital and largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary down to the North Sea, and has been a majo ...

on 14 December 1963. Lennon showed Maschler more of his drawings, mainly doodles made on scrap pieces of paper that had mostly been done in July 1963 while the Beatles played a residency in Margate

Margate is a seaside resort, seaside town on the north coast of Kent in south-east England. The town is estimated to be 1.5 miles long, north-east of Canterbury and includes Cliftonville, Garlinge, Palm Bay, UK, Palm Bay and Westbrook, Kent, ...

. Maschler encouraged him to continue with his pieces and drawings, then selected the title ''In His Own Write'' from a list of around twenty prospects, the pick originally an idea of McCartney. Among the rejected titles were ''In His Own Write and Draw'', ''The Transistor Negro'', ''Left Hand Left Hand'' and ''Stop One and Buy Me''.

Lennon signed a contract with Jonathan Cape for the book on 6 January 1964, receiving an advance of £1,000 (). He contributed 26 drawings and 31 pieces of writing, including 23 prose

Prose is a form of written or spoken language that follows the natural flow of speech, uses a language's ordinary grammatical structures, or follows the conventions of formal academic writing. It differs from most traditional poetry, where the f ...

pieces and eight poems, bringing the book's length to 80 pages. Its pieces range in length from the eight-line poems "Good Dog Nigel" and "The Moldy Moldy Man" to the three-page story "Scene three Act one". Lennon reported that his work on the book's illustrations was the most drawing he had done since leaving art school. Most of the written content was new, but some had been done previously, including the stories "On Safairy with Whide Hunter" (1958), "Henry and Harry" (1959), "Liddypool" (1961 as "Around And About"), "No Flies on Frank" (1962) and "Randolf's Party" (1962), and the poem "I Remember Arnold" (1958), which he wrote following the death of his mother, Julia. Lennon worked spontaneously and generally did not return to pieces after writing them, though he did revise "On Safairy with Whide Hunter" in mid-July 1962, adding a reference to the song " The Lion Sleeps Tonight", a hit in early 1962. Among the book's literary references are "I Wandered", which includes several plays on the title of the poem "I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud

"I Wandered Lonely as a Cloud" (also commonly known as "Daffodils") is a lyric poem by William Wordsworth. It is one of his most popular, and was inspired by a forest encounter on 15 April 1802 between he, his younger sister Dorothy and a "lon ...

" by English poet William Wordsworth

William Wordsworth (7 April 177023 April 1850) was an English Romantic poet who, with Samuel Taylor Coleridge, helped to launch the Romantic Age in English literature with their joint publication ''Lyrical Ballads'' (1798).

Wordsworth's ' ...

; "Treasure Ivan", which is a variation on the plot of '' Treasure Island'' by Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

; and "At the Denis", which paraphrases a scene at a dentist's office from Carlo Barone's English-teaching book, ''A Manual of Conversation English-Italian''.

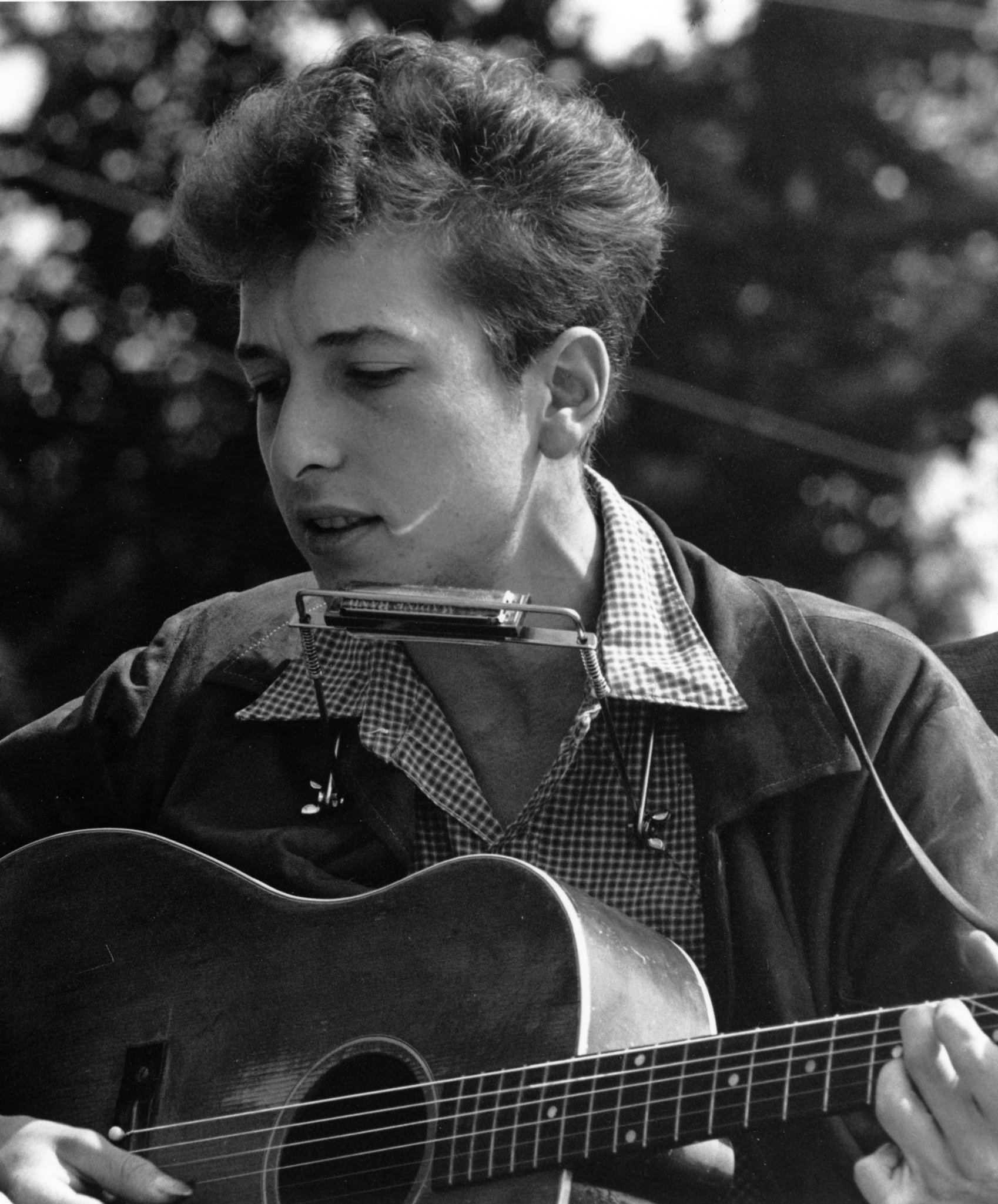

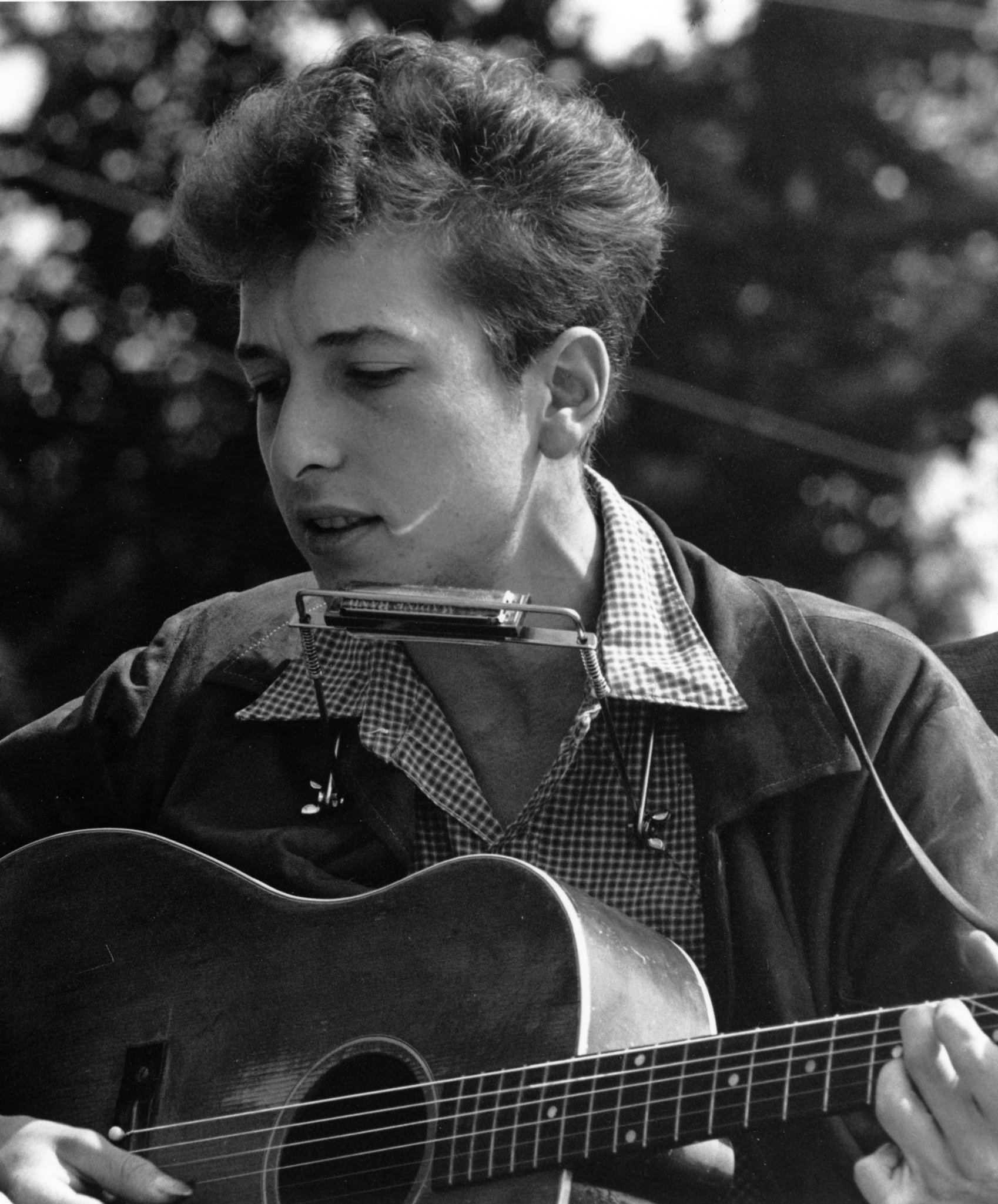

''In His Own Write'' was published in the UK on 23 March 1964, retailing for 9 s 6 d ()., quoted in . Lennon attended a launch party at Jonathan Cape's London offices the day before. Maschler refused a request from his superiors at Jonathan Cape that the cover depict Lennon holding a guitar, instead opting for a simple head shot

A head shot or headshot is a modern (usually digital) portrait in which the focus is on the person. The term is applied usually for professional profile images on social media, images used on online dating profiles, the 'about us page' of a cor ...

. Photographer Robert Freeman designed the first edition of the book, a black-and-white photograph he took of Lennon also adorning the cover. The back cover includes a humorous autobiography of Lennon, "About the Awful", again written in his unorthodox style. The book became an immediate best-seller, selling out on its first day. Only 25,000 copies of the first edition were printed, necessitating several reprints, including two in the last week of March 1964 and five more by January 1965. In its first ten months, the book sold almost 200,000 copies, eventually reaching around 300,000 copies bought in Britain. Simon & Schuster

Simon & Schuster () is an American publishing company and a subsidiary of Paramount Global. It was founded in New York City on January 2, 1924 by Richard L. Simon and M. Lincoln Schuster. As of 2016, Simon & Schuster was the third largest publ ...

published ''In His Own Write'' in the US on 27 April 1964, retailing for US$

The United States dollar (symbol: $; code: USD; also abbreviated US$ or U.S. Dollar, to distinguish it from other dollar-denominated currencies; referred to as the dollar, U.S. dollar, American dollar, or colloquially buck) is the official ...

2.50 (). The American edition was identical to the British, except that publishers added the caption "''The Writing Beatle!''" to the cover. The book was a best-seller in the US, where its publication took place around two months after the Beatles' first visit to the country and amid Beatlemania

Beatlemania was the fanaticism surrounding the English rock band the Beatles in the 1960s. The group's popularity grew in the United Kingdom throughout 1963, propelled by the singles "Please Please Me", "From Me to You" and "She Loves You". By ...

, the hysteria that surrounded the group.

Contributions by the other Beatles

McCartney contributed an introduction to ''In His Own Write'', writing that its content was nonsensical yet funny. In 1964 interviews, Lennon said that two pieces were co-authored with McCartney. Due to a publishing error only "On Safairy with Whide Hunter" was marked as such – being " itten in conjugal with Paul" – the other piece remaining unidentified. Beatles drummerRingo Starr

Sir Richard Starkey (born 7 July 1940), known professionally as Ringo Starr, is an English musician, singer, songwriter and actor who achieved international fame as the drummer for the Beatles. Starr occasionally sang lead vocals with the ...

, prone to incorrect wordings and malapropism

A malapropism (also called a malaprop, acyrologia, or Dogberryism) is the mistaken use of an incorrect word in place of a word with a similar sound, resulting in a nonsensical, sometimes humorous utterance. An example is the statement attributed to ...

s – dubbed "Ringoisms" by his bandmates – may have contributed a line to the book. Finishing up after a long day, perhaps 19 March 1964, he commented "it's been a hard day", and, on noticing it was dark, added s night" ("it's been a hard day's night"). While both Lennon and Starr later identified the phrase as Starr's, Lewisohn raises doubts that the phrase originated with him. He writes that if the 19 March dating is correct, that places it after Lennon had already included it in the story "Sad Michael", with the line "He'd had a hard days night that day". By 19 March, copies of ''In His Own Write'' had already been printed. Lewisohn suggests that Starr may have previously read or heard it in Lennon's story, while journalist Nicholas Schaffner simply writes the phrase originated with Lennon's poem. Beatles biographer Alan Clayson suggests the phrase's inspiration was Eartha Kitt

Eartha Kitt (born Eartha Mae Keith; January 17, 1927 – December 25, 2008) was an American singer and actress known for her highly distinctive singing style and her 1953 recordings of "C'est si bon" and the Christmas novelty song "Santa Ba ...

's 1963 song "I Had a Hard Day Last Night", the B-side

The A-side and B-side are the two sides of phonograph records and cassettes; these terms have often been printed on the labels of two-sided music recordings. The A-side usually features a recording that its artist, producer, or record compan ...

of her single "Lola Lola". After director Dick Lester

Richard Lester Liebman (born January 19, 1932) is an American retired film director based in the United Kingdom.

He is best known for directing the Beatles' films '' A Hard Day's Night'' (1964) and ''Help!'' (1965), and the superhero films ''S ...

suggested ''A Hard Day's Night'' as the title of the Beatles' 1964 film,, quoted in . Lennon used it again in the song of the same name.

Reception

''In His Own Write'' received critical acclaim, with favourable reviews in London's ''

''In His Own Write'' received critical acclaim, with favourable reviews in London's ''The Sunday Times

''The Sunday Times'' is a British newspaper whose circulation makes it the largest in Britain's quality press market category. It was founded in 1821 as ''The New Observer''. It is published by Times Newspapers Ltd, a subsidiary of News UK, whi ...

'' and ''The Observer

''The Observer'' is a British newspaper published on Sundays. It is a sister paper to ''The Guardian'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', whose parent company Guardian Media Group Limited acquired it in 1993. First published in 1791, it is the w ...

''. Among the most popular poems in the collection are "No Flies on Frank", "Good Dog Nigel", "The Wrestling Dog", "I Sat Belonely" and "Deaf Ted, Danoota, (and me)". ''The Times Literary Supplement

''The Times Literary Supplement'' (''TLS'') is a weekly literary review published in London by News UK, a subsidiary of News Corp.

History

The ''TLS'' first appeared in 1902 as a supplement to ''The Times'' but became a separate publication i ...

'' reviewer wrote that the book "is worth the attention of anyone who fears for the impoverishment of the English language and British imagination". In ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'', Harry Gilroy admired the writing style, describing it as "like a Beatle possessed", while George Melly

Alan George Heywood Melly (17 August 1926 – 5 July 2007) was an English jazz and blues singer, critic, writer, and lecturer. From 1965 to 1973 he was a film and television critic for ''The Observer''; he also lectured on art history, with an e ...

for ''The Sunday Times'' wrote: "It is fascinating of course to climb inside a Beatle's head to see what's going on there, but what really counts is that what's going on there really is fascinating." The ''Virginia Quarterly Review

The ''Virginia Quarterly Review'' is a quarterly literary magazine that was established in 1925 by James Southall Wilson, at the request of University of Virginia president E. A. Alderman. This ''"National Journal of Literature and Discussion"'' ...

'' called the book "a true delight" that finally gave "those intellectuals who have become stuck with Beatlemania... a serious literary excuse for their visceral pleasures". Gloria Steinem

Gloria Marie Steinem (; born March 25, 1934) is an American journalist and social-political activist who emerged as a nationally recognized leader of second-wave feminism

Second-wave feminism was a period of feminist activity that began in ...

opined in a December 1964 profile of Lennon for ''Cosmopolitan

Cosmopolitan may refer to:

Food and drink

* Cosmopolitan (cocktail), also known as a "Cosmo"

History

* Rootless cosmopolitan, a Soviet derogatory epithet during Joseph Stalin's anti-Semitic campaign of 1949–1953

Hotels and resorts

* Cosmopoli ...

'' that the book showed him to be the only one of the band who had "signs of a talent outside the hothouse world of musical fadism and teenage worship".

Though Lennon had never read him, comparisons to Irish writer James Joyce

James Augustine Aloysius Joyce (2 February 1882 – 13 January 1941) was an Irish novelist, poet, and literary critic. He contributed to the modernist avant-garde movement and is regarded as one of the most influential and important writers of ...

were common. In his review of the book, author Tom Wolfe

Thomas Kennerly Wolfe Jr. (March 2, 1930 – May 14, 2018)Some sources say 1931; ''The New York Times'' and Reuters both initially reported 1931 in their obituaries before changing to 1930. See and was an American author and journalist widely ...

mentions Spike Milligan as an influence, but writes that the "imitations of Joyce" were what "most intrigued the literati

Literati may refer to:

*Intellectuals or those who love, read, and comment on literature

*The scholar-official or ''literati'' of imperial/medieval China

**Literati painting, also known as the southern school of painting, developed by Chinese liter ...

" in America and England: "the mimicry of prayers, liturgies, manuals and grammars, the mad homonym

In linguistics, homonyms are words which are homographs (words that share the same spelling, regardless of pronunciation), or homophones (equivocal words, that share the same pronunciation, regardless of spelling), or both. Using this definition, ...

s, especially biting ones such as 'Loud' for 'Lord', which both oyce and Lennonuse". In a favourable review for ''The Nation

''The Nation'' is an American liberal biweekly magazine that covers political and cultural news, opinion, and analysis. It was founded on July 6, 1865, as a successor to William Lloyd Garrison's '' The Liberator'', an abolitionist newspaper tha ...

'', Peter Schickele drew comparison to Edward Lear

Edward Lear (12 May 1812 – 29 January 1888) was an English artist, illustrator, musician, author and poet, who is known mostly for his literary nonsense in poetry and prose and especially his limerick (poetry), limericks, a form he popularised. ...

, Carroll, Thurber and Joyce, adding that even those "with a predisposition toward the Beatles" will be "pleasantly shocked" when reading it. ''Time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, to ...

'' cited the same influences before admiring the book's typography

Typography is the art and technique of arranging type to make written language legible, readable and appealing when displayed. The arrangement of type involves selecting typefaces, point sizes, line lengths, line-spacing ( leading), and ...

, written "as if pages had been set by a drunken linotypist". ''Newsweek

''Newsweek'' is an American weekly online news magazine co-owned 50 percent each by Dev Pragad, its president and CEO, and Johnathan Davis (businessman), Johnathan Davis, who has no operational role at ''Newsweek''. Founded as a weekly print m ...

'' called Lennon "an heir to the Anglo-American tradition of nonsense", but found that the constant Carroll and Joyce comparisons were faulty, emphasising instead Lennon's uniqueness and " spontaneity". Bill Harry published a review in the 26 March 1964 issue of ''Mersey Beat'', written as a parody

A parody, also known as a spoof, a satire, a send-up, a take-off, a lampoon, a play on (something), or a caricature, is a creative work designed to imitate, comment on, and/or mock its subject by means of satiric or ironic imitation. Often its subj ...

of Lennon's style. In an accompanying "translation" of his review, he predicted that while it would " most certaintly... be a best seller", it could lend itself to controversy, with newer Beatles fans likely to be "puzzled by its way-out, off beat and sometimes sick humour".

One of the few negative responses to the book came from the Conservative Member of Parliament

A member of parliament (MP) is the representative in parliament of the people who live in their electoral district. In many countries with bicameral parliaments, this term refers only to members of the lower house since upper house members of ...

Charles Curran. On 19 June 1964, during a House of Commons debate on automation

Automation describes a wide range of technologies that reduce human intervention in processes, namely by predetermining decision criteria, subprocess relationships, and related actions, as well as embodying those predeterminations in machines ...

, he quoted the poem "Deaf Ted, Danoota, (and me)", then spoke derisively about the book, arguing that Lennon's verse was a symptom of a poor education system. He suggested that Lennon was "in a pathetic state of near-literacy", adding that " seems to have picked up bits of Tennyson, Browning, and Robert Louis Stevenson

Robert Louis Stevenson (born Robert Lewis Balfour Stevenson; 13 November 1850 – 3 December 1894) was a Scottish novelist, essayist, poet and travel writer. He is best known for works such as ''Treasure Island'', ''Strange Case of Dr Jekyll a ...

while listening with one ear to the football

Football is a family of team sports that involve, to varying degrees, kicking a ball to score a goal. Unqualified, the word ''football'' normally means the form of football that is the most popular where the word is used. Sports commonly c ...

results on the wireless

Wireless communication (or just wireless, when the context allows) is the transfer of information between two or more points without the use of an electrical conductor, optical fiber or other continuous guided medium for the transfer. The most ...

." The most unfavourable review of the book came from critic Christopher Ricks

Sir Christopher Bruce Ricks (born 18 September 1933) is a British literary critic and scholar. He is the William M. and Sara B. Warren Professor of the Humanities at Boston University (US), co-director of the Editorial Institute at Boston Univ ...

, who wrote in ''New Statesman

The ''New Statesman'' is a British political and cultural magazine published in London. Founded as a weekly review of politics and literature on 12 April 1913, it was at first connected with Sidney and Beatrice Webb and other leading members ...

'' that anyone unaware of the Beatles would be unlikely to draw pleasure from the book.

Reactions of Lennon and the Beatles

While the success of ''In His Own Write'' pleased Lennon, he was surprised by both the attention it received and its positive reception. In a 1965 interview, he admitted to purchasing all the books that critics compared to his, including one by Lear, one byGeoffrey Chaucer

Geoffrey Chaucer (; – 25 October 1400) was an English poet, author, and civil servant best known for ''The Canterbury Tales''. He has been called the "father of English literature", or, alternatively, the "father of English poetry". He wa ...

and '' Finnegans Wake'' by Joyce. He further stated that he did not see the similarities, except " erhapsa little bit of ''Finnegans Wake''... but anybody who changes words is going to be compared". In a 1968 interview, he said that reading ''Finnegans Wake'' "was great, and I dug it and felt as though oycewas an old friend", though he found the book difficult to read in its entirety.

Among Lennon's bandmates, Starr did not read the book, but Harrison and McCartney enjoyed it. Harrison stated in February 1964 that the book included "some great ags, and Lennon recalled McCartney was especially fond of the book, being "dead keen" about it. In Beatles manager Brian Epstein's 1964 autobiography '' A Cellarful of Noise'', he commented: "I was deeply gratified that a Beatle could detach himself from Beatleism and create such impact as an author". Beatles producer

Producer or producers may refer to:

Occupations

*Producer (agriculture), a farm operator

*A stakeholder of economic production

*Film producer, supervises the making of films

**Executive producer, contributes to a film's budget and usually does not ...

George Martin

Sir George Henry Martin (3 January 1926 – 8 March 2016) was an English record producer, arranger, composer, conductor, and musician. He was commonly referred to as the "Fifth Beatle" because of his extensive involvement in each of the B ...

– a fan of ''The Goon Show'' – and his wife Judy Lockhart-Smith similarly enjoyed Lennon's writings, with Martin calling them "terribly funny". In an August 1964 interview, Lennon identified "Scene three Act one" as his favourite piece in the book.

Foyle's Literary Luncheon

Following the book's publication,Christina Foyle

Christina Agnes Lilian Foyle (30 January 1911 – 8 June 1999) was an English bookseller and owner of Foyles bookshop.

Early life

Miss Foyle (as she liked to be called) was born in London, the daughter of William Foyle, a leading bookseller, ow ...

, the founder of Foyles

W & G Foyle Ltd. (usually called simply Foyles) is a bookseller with a chain of seven stores in England. It is best known for its flagship store in Charing Cross Road, London. Foyles was once listed in the ''Guinness Book of Records'' as the ...

bookshop, honoured Lennon at one of Foyle's Literary Luncheons. Osbert Lancaster chaired the event on 23 April 1964 at the Dorchester hotel in London. Among around six hundred attendees were several eminent guests, including Helen Shapiro

Helen Kate Shapiro (born 28 September 1946) is a British pop and jazz singer and actress. While still a teenager in the early 1960s, she was one of Britain's most successful female singers. With a voice described by AllMusic as possessing "th ...

, Yehudi Menuhin

Yehudi or Jehudi (Hebrew: יהודי, endonym for Jew) is a common Hebrew name:

* Yehudi Menuhin (1916–1999), violinist and conductor

** Yehudi Menuhin School, a music school in Surrey, England

** Who's Yehoodi?, a catchphrase referring to the v ...

and Wilfrid Brambell. Hungover from a night spent at the Ad Lib Club

The Ad Lib Club was a nightclub on the fourth floor of 7 Leicester Place over the Prince Charles Cinema in London's Soho district. It opened in February 1964 (or December 1963), and closed in its original location after a fire. The owner, Brian Mo ...

, Lennon admitted to a journalist at the event that he was "scared stiff". He was reluctant to perform the expected speech, getting Epstein to advise luncheon organisers Foyle and Ben Perrick the day before the event that he would not be speaking. The two were taken aback, but assumed that Lennon meant he would only provide a short speech.

At the event, after Lancaster introduced him, Lennon stood and only said: "Uh, thank you very much, and God bless you. You've got a lucky face." Foyle was irritated, while Perrick recalls there was "some slight feeling of bewilderment" among attendees. Epstein gave a speech to avoid further disappointing any diners that had hoped to hear from Lennon. In ''A Cellarful of Noise'', Epstein expressed of Lennon's lack of a speech: "He was not prepared to do something which was not only unnatural to him, but also something he might have done badly. He was not going to fail." Perrick reflects that Lennon retained the affection of his audience due to his "charm and charisma", with attendees still happily queuing afterwards for signed copies.

Analysis

Against Lennon's songwriting

Later commentators have discussed the book's prose in relation to Lennon's songwriting, both in how it differed from his contemporary writing and in how it anticipates his later work. Writer Chris Ingham describes the book as "surreal

Surreal may refer to:

*Anything related to or characteristic of Surrealism, a movement in philosophy and art

* "Surreal" (song), a 2000 song by Ayumi Hamasaki

* ''Surreal'' (album), an album by Man Raze

*Surreal humour, a common aspect of humor

...

poetry", displaying "a darkness and bite... that was light years away from ' I Want to Hold Your Hand. Professor of English Ian Marshall describes Lennon's prose as "mad wordplay", noting the Lewis Carroll influence and suggesting it anticipates the lyrics of later songs like " Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds" and " I Am the Walrus". Critic Tim Riley compares the short story "Unhappy Frank" to "I Am the Walrus", though he calls the former "a good deal more oblique and less cunning".

Walter Everett describes the book as including "Joycean A text is deemed Joycean when it is reminiscent of the writings of James Joyce, particularly '' Ulysses'' or ''Finnegans Wake''. Joycean fiction exhibits a high degree of verbal play, usually within the framework of stream of consciousness. Works ...

dialect substitutions, Carrollian portmanteau

A portmanteau word, or portmanteau (, ) is a blend of wordsstream-of-consciousness

In literary criticism, stream of consciousness is a narrative mode or method that attempts "to depict the multitudinous thoughts and feelings which pass through the mind" of a narrator. The term was coined by Daniel Oliver in 1840 in ''First Li ...

double-entendre

A double entendre (plural double entendres) is a figure of speech or a particular way of wording that is devised to have a double meaning, of which one is typically obvious, whereas the other often conveys a message that would be too socially a ...

". Unlike Carroll, Lennon generally did not create new words in his writing, but instead used homonym

In linguistics, homonyms are words which are homographs (words that share the same spelling, regardless of pronunciation), or homophones (equivocal words, that share the same pronunciation, regardless of spelling), or both. Using this definition, ...

s (such as ''grate'' for ''great'') and other phonological and morphological distortions (such as ''peoble'' for ''people''). Both Everett and Beatles researcher Kevin Howlett discuss the influence of ''Alice's Adventures in Wonderland'' and ''Through the Looking-Glass'' on both of Lennon's books and on the lyrics for "Lucy in the Sky with Diamonds". Everett singles out the poems "Deaf Ted, Danoota, (and me)" and "I Wandered" as examples of this influence, quoting an excerpt from "I Wandered" to illustrate this:Good Morning Good Morning

"Good Morning Good Morning" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1967 album '' Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Hearts Club Band''. It was written by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney. Inspiration for the song came to Lenn ...

", seeing both as illustrating the "dispirited domestic milieu" of "protagonists hodrag themselves through the day 'crestfalled and defective. Everett suggests that while the character Bungalow Bill in Lennon's 1968 song " The Continuing Story of Bungalow Bill" is generally understood to be a portmanteau

A portmanteau word, or portmanteau (, ) is a blend of wordsJungle Jim and

Beatles writer Kenneth Womack suggests that, paired with the Beatles' debut film, the book challenged the band's "non-believers", made up of those outside their then largely teenage fanbase, a contention with which philosophy professor Bernard Gendron agrees, writing that the two pieces of media initiated "a major reversal of the public assessment of the Beatles' aesthetic worth." Doggett groups the book with the Beatles' more general move from the "classic working-class pop milieu" towards "an arty middle-class environment". He argues that the band's invitation into the British establishment – such as their interactions with photographer Robert Freeman, director Dick Lester and publisher Tom Maschler, among others – was unique for pop musicians of the time and threatened to erode elements of the British class system. Prince Philip of the British royal family read the book and said he enjoyed it thoroughly, while Canadian Prime Minister

Beatles writer Kenneth Womack suggests that, paired with the Beatles' debut film, the book challenged the band's "non-believers", made up of those outside their then largely teenage fanbase, a contention with which philosophy professor Bernard Gendron agrees, writing that the two pieces of media initiated "a major reversal of the public assessment of the Beatles' aesthetic worth." Doggett groups the book with the Beatles' more general move from the "classic working-class pop milieu" towards "an arty middle-class environment". He argues that the band's invitation into the British establishment – such as their interactions with photographer Robert Freeman, director Dick Lester and publisher Tom Maschler, among others – was unique for pop musicians of the time and threatened to erode elements of the British class system. Prince Philip of the British royal family read the book and said he enjoyed it thoroughly, while Canadian Prime Minister

Buffalo Bill

William Frederick Cody (February 26, 1846January 10, 1917), known as "Buffalo Bill", was an American soldier, Bison hunting, bison hunter, and showman. He was born in Le Claire, Iowa, Le Claire, Iowa Territory (now the U.S. state of Iowa), but ...

, the name also could have its origins in the character Jumble Jim from Lennon and McCartney's short story "On Safairy with Whide Hunter".

On 23 March 1964 – the same day the book was published in the UK – Lennon went to Lime Grove Studios

Lime Grove Studios was a film, and later television, studio complex in Shepherd's Bush, West London, England.

The complex was built by the Gaumont Film Company in 1915. It was situated in Lime Grove, a residential street in Shepherd's Bush, and ...

, West London

West London is the western part of London, England, north of the River Thames, west of the City of London, and extending to the Greater London boundary.

The term is used to differentiate the area from the other parts of London: North London ...

, to film a segment promoting it. The BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC #REDIRECT BBC

Here i going to introduce about the best teacher of my life b BALAJI sir. He is the precious gift that I got befor 2yrs . How has helped and thought all the concept and made my success in the 10th board ex ...

programme ''Tonight

Tonight may refer to:

Television

* ''Tonight'' (1957 TV programme), a 1957–1965 British current events television programme hosted by Cliff Michelmore that was broadcast on BBC

* ''Tonight'' (1975 TV programme), a 1975–1979 British current ...

'' broadcast the segment live, with presenters Cliff Michelmore

Arthur Clifford Michelmore (11 December 1919 – 16 March 2016) was an English television presenter and producer.

He is best known for the BBC television programme ''Tonight'', which he presented from 1957 to 1965. He also hosted the BBC's tel ...

, Derek Hart

Derek Osborne Hart (18 March 1925 – 23 November 1986) was a British actor, journalist and radio presenter best known for his appearances on the BBC's current affairs programme of the 1950s and 1960s, ''Tonight''.

Hart was born in Hertfordshire ...

and Kenneth Allsop

Kenneth Allsop (29 January 1920 – 23 May 1973) was a British broadcaster, author and naturalist.

Early life

Allsop was born on 29 January 1920 in Holbeck, Leeds, West Riding of Yorkshire.

He was married in St Peter's Church, Ealing, i ...

reading excerpts. A four-minute interview between Allsop and Lennon followed, with Allsop challenging him to try using similar wordplay and imagination in his songwriting. Similar questions about the banality of his song lyrics – including from musician Bob Dylan

Bob Dylan (legally Robert Dylan, born Robert Allen Zimmerman, May 24, 1941) is an American singer-songwriter. Often regarded as one of the greatest songwriters of all time, Dylan has been a major figure in popular culture during a career sp ...

– became common following the publication of his book, pushing him to write deeper, more introspective songs in the years that followed. In a December 1970 interview with Jann Wenner

Jann Simon Wenner ( ; born January 7, 1946) is an American magazine magnate who is a co-founder of the popular culture magazine ''Rolling Stone'', and former owner of '' Men's Journal'' magazine. He participated in the Free Speech Movement while ...

of ''Rolling Stone

''Rolling Stone'' is an American monthly magazine that focuses on music, politics, and popular culture. It was founded in San Francisco, San Francisco, California, in 1967 by Jann Wenner, and the music critic Ralph J. Gleason. It was first kno ...

'', Lennon explained that early in his career he made a conscious split between writing pop music

Pop music is a genre of popular music that originated in its modern form during the mid-1950s in the United States and the United Kingdom. The terms ''popular music'' and ''pop music'' are often used interchangeably, although the former describe ...

for public consumption and the expressive writing found in ''In His Own Write'', with the latter representing "the personal stories... expressive of my personal emotions". In his 1980 ''Playboy'' interview, he recalled the Allsop interview as being the impetus for his writing " In My Life". Writer John C. Winn mentions songs like " I'm a Loser", " You've Got to Hide Your Love Away" and " Help!" as exemplifying Lennon's move to deeper writing in the year after the book. Music scholar Terence O'Grady describes the "surprising twists" of Lennon's 1965 song " Norwegian Wood (This Bird Has Flown)" as more similar to ''In His Own Write'' than his earlier songs, and Sauceda mentions several of Lennon's later Beatles songs – including "I Am the Walrus", "What's the New Mary Jane

"What's the New Mary Jane" is a song written by John Lennon (credited to Lennon–McCartney) and performed by the English rock band the Beatles. It was recorded in 1968 during sessions for the double album ''The Beatles'' (also known as "the Wh ...

", " Come Together", "Dig a Pony

"Dig a Pony" is a song by the English rock band the Beatles from their 1970 album ''Let It Be''. It was written by John Lennon and credited to Lennon–McCartney. The band recorded the song on 30 January 1969, during their rooftop concert at th ...

" – as demonstrating his ability for "sound-sense writing", where words are assembled not for their meaning but instead for their rhythm and for "the joy of sound".

James Sauceda and ''Finnegans Wake''

Sauceda produced the only comprehensive study of Lennon's writings in his 1983 book ''Literary Lennon: A Comedy of Letters'', providing apostmodern

Postmodernism is an intellectual stance or mode of discourseNuyen, A.T., 1992. The Role of Rhetorical Devices in Postmodernist Discourse. Philosophy & Rhetoric, pp.183–194. characterized by skepticism toward the " grand narratives" of moderni ...

dissection of both ''In His Own Write'' and Lennon's next book of nonsense literature, '' A Spaniard in the Works''. Everett describes the book as "a thorough but sometimes wrongheaded postmodern ''Finnegans Wake''-inspired parsing". Sauceda, for example, casts doubt on Lennon's claim that he had never read Joyce before writing ''In His Own Write''. He suggests that the lines "he was debb and duff and could not speeg" and "Practice daily but not if you are Mutt and Jeff" from the pieces "Sad Michael" and "All Abord Speeching", respectively, were influenced by a passage from ''Finnegans Wake'' discussing whether someone is deaf or deaf-mute, reading: Author Peter Doggett is even more dismissive of Sauceda than Everett, criticising Sauceda for missing references to British popular culture. In particular, he mentions the analysis of the story "The Famous Five Through Woenow Abbey", wherein Sauceda concludes that the Famous Five of the story refers to Epstein and the Beatles, but does not mention the popular British children's novels ''The Famous Five

''The Famous Five'' is a series of children's Adventure fiction, adventure novels and short stories written by English author Enid Blyton. The first book, ''Five on a Treasure Island'', was published in 1942. The novels feature the adventures ...

'', written by Enid Blyton – referred to as "Enig Blyter" in Lennon's story. Riley calls Sauceda's insights "keen", but suggests more can be understood by analysing the works with reference to Lennon's biography. Gould comments that ''The Goon Show'' was Lennon's closest experience to the style of ''Finnegans Wake'', and describes Milligan's 1959 book ''Silly Verse for Kids

''Silly Verse for Kids'' is a collection of humorous poems, limericks and drawings for children by Spike Milligan, first published by Dennis Dobson in 1959.

''Silly Verse for Kids'' was Milligan's first book. Many of the pieces had been written ...

'' as "the direct antecedent to ''In His Own Write''."

Against Lennon's biography

Before he signed with Jonathan Cape, Lennon wrote prose and poetry to keep for himself and share with his friends, leaving his pieces filled with private meanings andin-joke

An in-joke, also known as an inside joke or a private joke, is a joke whose humour is understandable only to members of an ingroup; that is, people who are ''in'' a particular social group, occupation, or other community of shared interest. It i ...

s. Quoted in a February 1964 piece in ''Mersey Beat'', Harrison said with regard to the book that " e 'with-it' people will get the gags and there are some great ones". Lewisohn states that Lennon based the story "Henry and Harry" on an experience of Harrison, whose father gifted him electrician's tools for Christmas

Christmas is an annual festival commemorating Nativity of Jesus, the birth of Jesus, Jesus Christ, observed primarily on December 25 as a religious and cultural celebration among billions of people Observance of Christmas by country, around t ...

1959, implying he expected his son to become an electrician despite Harrison's disagreement. In the story, Lennon writes that such jobs were "brummer striving", explaining in a 1968 television interview that the term referred to "all those jobs that people have that they don't want. And there's probably about 90 percent brummer strivers watching in at the moment." The 1962 story "Randolf's Party" was never discussed by Lennon, but Lewisohn suggests he most likely wrote it about former Beatles drummer Pete Best. Lewisohn mentions similarities between Best and the lead character, including an absent father figure and Best's first name being Randolf. Best biographer Mallory Curley describes the lines "We never liked you all the years we've known you. You were never raelly one of us you know, soft head" as, "the crux of Pete's Beatles career, in one paragraph."

Riley opines that the short story "Unhappy Frank" can be read as Lennon's "screed against 'mother, aimed at both his aunt Mimi and late-mother Julia for their over-protectiveness and absence, respectively. The poem "Good Dog Nigel" tells the story of a happy dog that is put down. Riley suggests it was inspired by Mimi putting down Lennon's dog, Sally, and that the dog in the poem shares its name with Lennon's childhood friend Nigel Walley

Christopher Nigel Walley (born 30 June 1941) is an English former golfer and tea-chest bass player and manager, best known for his association with band The Quarrymen, the precursor of The Beatles which included John Lennon. His surname has o ...

, a witness to Julia's death. Prone to hitting his girlfriends as a teenager, Lennon also included several domestic violence

Domestic violence (also known as domestic abuse or family violence) is violence or other abuse that occurs in a domestic setting, such as in a marriage or cohabitation. ''Domestic violence'' is often used as a synonym for ''intimate partner ...

allusions in the book, such as "No Flies on Frank", where a man beats his wife to death and then tries to deliver the corpse to his mother-in-law. In his book ''The Lives of John Lennon

''The Lives of John Lennon'' is a 1988 biography of musician John Lennon by American

author Albert Goldman. The book is a product of several years of research and hundreds of interviews with Lennon's friends, acquaintances, servants and musician ...

'', author Albert Goldman interprets the story as relating to Lennon's feelings about his wife Cynthia

Cynthia is a feminine given name of Greek origin: , , "from Mount Cynthus" on Delos island. The name has been in use in the Anglosphere since the 1600s. There are various spellings for this name, and it can be abbreviated to Cindy, Cyndi, Cyndy, ...

and Mimi.

Sauceda and Ingham comment that the book includes several references to "cripples", Lennon having had developed phobias of physical and mental disabilities as a child. Thelma Pickles, Lennon's girlfriend in the autumn of 1958, later recalled he would joke with disabled people he encountered in public, including " ccostingmen in wheelchairs and eering 'How did you lose your legs? Chasing the wife? In an interview with Hunter Davies for '' The Beatles: The Authorised Biography'', Lennon admitted that he "did have a cruel humor", suggesting it was a way of hiding his emotions. He concluded: "I would never hurt a cripple. It was just part of our jokes, our way of life." During the Beatles' tours, people with physical handicaps were often brought to meet the band, with some parents hoping that their child being touched by a Beatle would heal them. In his 1970 interview with ''Rolling Stone'', Lennon remembered, " were just surrounded by cripples and blind people all the time and when we would go through corridors they would be all touching us. It got like that, it was horrifying". Sauceda suggests that these strange recent experiences led to Lennon to incorporating them into his stories. For Doggett, the essential qualities of Lennon's writing are "cruelty, matter-of-fact attitude to death and destruction, and quick descent from bathos into gibberish".

Anti-authority and the Beat movement

''In His Own Write'' includes elements of anti-authority sentiment, disparaging both politics andChristianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, with Lennon recalling that the book was "pretty heavy on the church" with "many knocks at religion" and includes a scene depicting a dispute between a worker and a capitalist

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their operation for profit. Central characteristics of capitalism include capital accumulation, competitive markets, price system, priva ...

. Riley suggests that contemporary reviewers were overtaken by the book's "loopy, scabrous energy", overlooking the "subversion hichlay embedded in its cryptic asides". The story "A letter", for example, references Christine Keeler

Christine Margaret Keeler (22 February 1942 – 4 December 2017) was an English model and showgirl. Her meeting at a dance club with society osteopath Stephen Ward drew her into fashionable circles. At the height of the Cold War, she became s ...

and the Profumo affair, featuring a drawing of her and the closing line, "We hope this fires you as you keeler."

Lennon and his best friend in art college, Stu Sutcliffe, often discussed writers like Henry Miller

Henry Valentine Miller (December 26, 1891 – June 7, 1980) was an American novelist. He broke with existing literary forms and developed a new type of semi-autobiographical novel that blended character study, social criticism, philosophical ref ...

, Jack Kerouac

Jean-Louis Lebris de Kérouac (; March 12, 1922 – October 21, 1969), known as Jack Kerouac, was an American novelist and poet who, alongside William S. Burroughs and Allen Ginsberg, was a pioneer of the Beat Generation.

Of French-Canadian a ...

and other Beat poets

Beat, beats or beating may refer to:

Common uses

* Patrol, or beat, a group of personnel assigned to monitor a specific area

** Beat (police), the territory that a police officer patrols

** Gay beat, an area frequented by gay men

* Battery ( ...

, such as Gregory Corso

Gregory Nunzio Corso (March 26, 1930 – January 17, 2001) was an American poet and a key member of the Beat movement. He was the youngest of the inner circle of Beat Generation writers (with Jack Kerouac, Allen Ginsberg, and William S. Burrough ...

and Lawrence Ferlinghetti. Lennon, Sutcliffe and Harry sometimes interacted with the local British beat scene, and, in June 1960, the Beatles – then known as the Silver Beetles – provided musical backing for the beat poet Royston Ellis

Christopher Royston George Ellis (born 10 February 1941), known as Royston Ellis, is an English novelist, travel writer and erstwhile beat poet.

Biography

Born in Pinner, Ellis was educated at the Harrow County School for Boys in Middlesex unt ...

during a poetry reading at the Jacaranda

The Jacaranda is a Liverpool music venue closely associated with the rise of the Merseybeat phenomenon in the 1960s. Opened by The Beatles' first manager Allan Williams in 1958, it played a key role in launching the band's early careers, in add ...

coffee bar in Liverpool. While Lennon suggested in a 1965 interview that if he had not been a Beatle he "might have been a Beat Poet", author Greg Herriges declares that ''In His Own Write'' irreverent attacks on the mainstream ranked Lennon among the best of his predecessors in the Beat Generation

The Beat Generation was a literary subculture movement started by a group of authors whose work explored and influenced American culture and politics in the post-war era. The bulk of their work was published and popularized by Silent Generatio ...

. Journalist Simon Warner disagrees, positing that Lennon's writing style owed little to the Beat movement, being instead largely derived from the nonsense tradition of the late nineteenth century.

Illustrations

The illustrations of ''In His Own Write'' have received comparatively little attention. Doggett writes that the book's drawings are similar to the "shapeless figures" of Thurber, but with Lennon's unique touch. He interprets much of the art as displaying the same fascination with cripples apparent in the text, joining faces to "unwieldy, joke-animal bodies" alongside figures "distorted almost beyond humanity". Journalist Scott Gutterman describes the characters as "strange, protoplasmic creatures", and "lumpen everyman and everywoman figures" joined by animals, " ambolingaround an empty landscape, engaged in obscure pursuits". Analysing the illustration accompanying the piece "Randolf's Party", Gutterman describes the group as "gossiping, frowning, and bunching together", but while some figures adhere to regular social conventions, some fly away out of the image. Doggett interprets the same drawing as including "Neanderthal

Neanderthals (, also ''Homo neanderthalensis'' and erroneously ''Homo sapiens neanderthalensis''), also written as Neandertals, are an extinct species or subspecies of archaic humans who lived in Eurasia until about 40,000 years ago. While th ...

men", some merely faces attached to ballons, while others "oast

An oast, oast house or hop kiln is a building designed for kilning (drying) hops as part of the brewing process. They can be found in most hop-growing (and former hop-growing) areas and are often good examples of vernacular architecture. Many re ...

Cubist profiles with one eye hovering just outside their faces". Sauceda suggests the figures of the drawing reappear in the Beatles' 1968 animated film

Animation is a method by which image, still figures are manipulated to appear as Motion picture, moving images. In traditional animation, images are drawn or painted by hand on transparent cel, celluloid sheets to be photographed and exhibited ...

, '' Yellow Submarine'', and describes the "balloon heads" as a metaphor for people's "empty-headedness". Doggett and Sauceda each identify self-portrait

A self-portrait is a representation of an artist that is drawn, painted, photographed, or sculpted by that artist. Although self-portraits have been made since the earliest times, it is not until the Early Renaissance in the mid-15th century tha ...

s among Lennon's drawings, including one of a Lennon-like figure flying through the air, which Doggett determines to be one of the book's best illustrations. Doggett interprets it as evoking Lennon's "wish-fulfillment dreams", while Sauceda and Gutterman each see the drawing as representing the freedom Lennon felt in making his art.

Legacy

Cultural commentators of the 1960s often focused on Lennon as the leading artistic and literary figure in the Beatles. In her study of Beatleshistoriography

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians ha ...

, historian Erin Torkelson Weber suggests that the publication of ''In His Own Write'' reinforced these perceptions, with many vieiwng Lennon as "the smart one" of the group, and that the band's first film, ''A Hard Day's Night'', further emphasised that view. Everett arrives at similar conclusions, writing that, however unfairly, Lennon was often described as more artistically adventurous than McCartney in part because of the publication of his two books. Communications professor Michael R. Frontani states that the book served to further distinguish Lennon's image within the Beatles, while ''Independent

Independent or Independents may refer to:

Arts, entertainment, and media Artist groups

* Independents (artist group), a group of modernist painters based in the New Hope, Pennsylvania, area of the United States during the early 1930s

* Independ ...

'' writer Andy Gill

Andrew James Dalrymple Gill (1 January 1956 – 1 February 2020) was a British musician and record producer. He was the lead guitarist for the rock band Gang of Four, which he co-founded in 1976. Gill was known for his angular, jagged style of gu ...

felt that it and ''A Spaniard in the Works'' revealed Lennon to be "the sharpest Beatle, a man of acid wit".

Beatles writer Kenneth Womack suggests that, paired with the Beatles' debut film, the book challenged the band's "non-believers", made up of those outside their then largely teenage fanbase, a contention with which philosophy professor Bernard Gendron agrees, writing that the two pieces of media initiated "a major reversal of the public assessment of the Beatles' aesthetic worth." Doggett groups the book with the Beatles' more general move from the "classic working-class pop milieu" towards "an arty middle-class environment". He argues that the band's invitation into the British establishment – such as their interactions with photographer Robert Freeman, director Dick Lester and publisher Tom Maschler, among others – was unique for pop musicians of the time and threatened to erode elements of the British class system. Prince Philip of the British royal family read the book and said he enjoyed it thoroughly, while Canadian Prime Minister

Beatles writer Kenneth Womack suggests that, paired with the Beatles' debut film, the book challenged the band's "non-believers", made up of those outside their then largely teenage fanbase, a contention with which philosophy professor Bernard Gendron agrees, writing that the two pieces of media initiated "a major reversal of the public assessment of the Beatles' aesthetic worth." Doggett groups the book with the Beatles' more general move from the "classic working-class pop milieu" towards "an arty middle-class environment". He argues that the band's invitation into the British establishment – such as their interactions with photographer Robert Freeman, director Dick Lester and publisher Tom Maschler, among others – was unique for pop musicians of the time and threatened to erode elements of the British class system. Prince Philip of the British royal family read the book and said he enjoyed it thoroughly, while Canadian Prime Minister Pierre Trudeau

Joseph Philippe Pierre Yves Elliott Trudeau ( , ; October 18, 1919 – September 28, 2000), also referred to by his initials PET, was a Canadian lawyer and politician who served as the 15th prime minister of Canada

The prime mini ...

described Lennon in 1969 as "a pretty good poet". The book resulted in numerous businesses and charities requesting that Lennon produce illustrations. In 2014, the broker Sotheby's

Sotheby's () is a British-founded American multinational corporation with headquarters in New York City. It is one of the world's largest brokers of fine and decorative art, jewellery, and collectibles. It has 80 locations in 40 countries, and ...

auctioned over one hundred of Lennon's manuscripts for ''In His Own Write'' and ''A Spaniard in the Works'' from Maschler's collection. The short stories, poems and line drawings sold for US$2.9 million (US$ million adjusted for inflation), more than double their pre-sale estimate.

Lennon issuing a book of poetry before Bob Dylan subverted expectations in Britain, where Lennon was still seen as a simple pop star and Dylan was lauded as a poet. Inspired by ''In His Own Write'', Dylan began his first book of poetry in 1965, later published in 1971 as ''Tarantula

Tarantulas comprise a group of large and often hairy spiders of the family Theraphosidae. , 1,040 species have been identified, with 156 genera. The term "tarantula" is usually used to describe members of the family Theraphosidae, although ...

''. Using similar wordplay, though with fewer puns, Dylan described it contemporaneously as "a John Lennon-type book". Dylan biographer Clinton Heylin suggests that Lennon's piece "A Letter" is the most overt example of ''In His Own Write'' influence on ''Tarantula'', with several similar satirical letters appearing in Dylan's collection. Three volumes of Dylan's personal writings were later booklegged under the title ''In His Own Write: Personal Sketches'', released in 1980, 1990 and 1992. Beyond influencing Dylan, the book also inspired Michael Maslin

Michael Maslin is an American cartoonist for ''The New Yorker'' magazine. He is the author of ''Peter Arno: The Mad Mad World of The New Yorker’s Greatest Cartoonist'' published in April 2016 by Regan Arts. Four collections of his work were p ...

, a cartoonist for ''The New Yorker

''The New Yorker'' is an American weekly magazine featuring journalism, commentary, criticism, essays, fiction, satire, cartoons, and poetry. Founded as a weekly in 1925, the magazine is published 47 times annually, with five of these issues ...

'' magazine. A fellow Thurber enthusiast, he identified it, particularly the piece "The Fat Growth of Eric Hearble", as his introduction to "crazy wacky humor".

Other versions

''The Penguin John Lennon''

In 1965, Lennon published a second book of nonsense literature, ''A Spaniard in the Works'', expanding on the wordplay and parody of ''In His Own Write''. While it was a best-seller, reviewers were generally unenthusiastic, considering it similar to his first book yet without the benefit of being unexpected. He began a third book, planned for release in February 1966, but abandoned it soon after, leaving the two books the only ones published in his lifetime. In what Doggett terms "an admission that his literary career was at an end", Lennon consented to both of his books being joined into a single paperback. On 27 October 1966,Penguin Books