It Can't Happen Here on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

''It Can't Happen Here'' is a 1935 dystopian

According to Boulard (1998), "the most chilling and uncanny treatment of Huey by a writer came with Sinclair Lewis's ''It Can't Happen Here''." Lewis portrayed a genuine U.S. dictator on the Hitler model. Starting in 1936, the

According to Boulard (1998), "the most chilling and uncanny treatment of Huey by a writer came with Sinclair Lewis's ''It Can't Happen Here''." Lewis portrayed a genuine U.S. dictator on the Hitler model. Starting in 1936, the

It really can happen here: The novel that foreshadowed Donald Trump’s authoritarian appeal

. ''Salon'', September 29, 2015. In ''

political novel

Political fiction employs narrative to comment on political events, systems and theories. Works of political fiction, such as political novels, often "directly criticize an existing society or present an alternative, even fantast ...

by American author Sinclair Lewis

Harry Sinclair Lewis (February 7, 1885 – January 10, 1951) was an American writer and playwright. In 1930, he became the first writer from the United States (and the first from the Americas) to receive the Nobel Prize in Literature, which was ...

. It describes the rise of a United States dictator similar to how Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

gained power. The novel was adapted into a play by Lewis and John C. Moffitt in 1936.

Premise

The novel was published during the heyday offascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

in Europe, which was reported on by Dorothy Thompson

Dorothy Celene Thompson (July 9, 1893 – January 30, 1961) was an American journalist and radio broadcaster. She was the first American journalist to be expelled from Nazi Germany in 1934 and was one of the few women news commentators on radio ...

, Lewis's wife. The novel describes the rise of Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip, a demagogue

A demagogue (from Greek , a popular leader, a leader of a mob, from , people, populace, the commons + leading, leader) or rabble-rouser is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, e ...

who is elected President of the United States

The president of the United States (POTUS) is the head of state and head of government of the United States of America. The president directs the executive branch of the federal government and is the commander-in-chief of the United Stat ...

, after fomenting fear and promising drastic economic and social reforms while promoting a return to patriotism and traditional values. After his election, Windrip takes complete control of the government via self-coup

A self-coup, also called autocoup (from the es, autogolpe), is a form of coup d'état in which a nation's head, having come to power through legal means, tries to stay in power through illegal means. The leader may dissolve or render powerless ...

and imposes totalitarian

Totalitarianism is a form of government and a political system that prohibits all opposition parties, outlaws individual and group opposition to the state and its claims, and exercises an extremely high if not complete degree of control and regul ...

rule with the help of a ruthless paramilitary force, in the manner of European fascists such as Adolf Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Nazi Germany, Germany from 1933 until Death of Adolf Hitler, his death in 1945. Adolf Hitler's rise to power, He rose to power as the le ...

and Benito Mussolini

Benito Amilcare Andrea Mussolini (; 29 July 188328 April 1945) was an Italian politician and journalist who founded and led the National Fascist Party. He was Prime Minister of Italy from the March on Rome in 1922 until his deposition in 194 ...

. The novel's plot centers on journalist Doremus Jessup's opposition to the new regime and his subsequent struggle against it as part of a liberal rebellion.

Plot

In 1936, Senator Berzelius "Buzz" Windrip, a charismatic and power-hungry politician from an unnamed U.S. state, enters the presidential election campaign on apopulist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

platform, promising to restore the country to prosperity and greatness, and promising each citizen $5,000 per year. Portraying himself as a champion of "the forgotten man

The forgotten man is a political concept in the United States centered around those whose interests have been neglected. The first main invocation of this concept came from William Graham Sumner in an 1883 lecture in Brooklyn entitled ''The Forgott ...

" and traditional American values, Windrip defeats President Franklin D. Roosevelt

Franklin Delano Roosevelt (; ; January 30, 1882April 12, 1945), often referred to by his initials FDR, was an American politician and attorney who served as the 32nd president of the United States from 1933 until his death in 1945. As the ...

for the Democratic nomination, and then easily beats his Republican opponent, Senator Walt Trowbridge, in the November election.

Although having previously foreshadowed some authoritarian

Authoritarianism is a political system characterized by the rejection of political plurality, the use of strong central power to preserve the political ''status quo'', and reductions in the rule of law, separation of powers, and democratic votin ...

measures to reorganize the United States government, Windrip rapidly outlaws dissent, incarcerates political enemies in concentration camps

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

, and trains and arms a paramilitary

A paramilitary is an organization whose structure, tactics, training, subculture, and (often) function are similar to those of a professional military, but is not part of a country's official or legitimate armed forces. Paramilitary units carr ...

force called the Minute Men (named after the Revolutionary War militias of the same name), who terrorize citizens and enforce the policies of Windrip and his corporatist

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. The ...

regime. One of Windrip's first acts as president is to eliminate the influence of the United States Congress

The United States Congress is the legislature of the federal government of the United States. It is bicameral, composed of a lower body, the House of Representatives, and an upper body, the Senate. It meets in the U.S. Capitol in Washing ...

, which draws the ire of many citizens as well as the legislators themselves. The Minute Men respond to protests against Windrip's decisions harshly, attacking demonstrators with bayonets. In addition to these actions, Windrip's administration, known as the Corpo government, curtails women's and minority rights, and eliminates individual states by subdividing the country into administrative sectors. The government of these sectors is managed by Corpo authorities, usually prominent businessmen or Minute Men officers. Those accused of crimes against the government appear before kangaroo court

A kangaroo court is a court that ignores recognized standards of law or justice, carries little or no official standing in the territory within which it resides, and is typically convened ad hoc. A kangaroo court may ignore due process and come ...

s presided over by military judges. Despite these dictatorial and "quasi-draconian" measures, a majority of Americans approve of them, seeing them as painful but necessary steps to restore U.S. power.

Open opponents of Windrip, led by Senator Trowbridge, form an organization called the New Underground (named after the Underground Railroad

The Underground Railroad was a network of clandestine routes and safe houses established in the United States during the early- to mid-19th century. It was used by enslaved African Americans primarily to escape into free states and Canada. T ...

), helping dissidents escape to Canada and distributing anti-Windrip propaganda. One recruit to the New Underground is Doremus Jessup, the novel's protagonist, a traditional liberal

Liberal or liberalism may refer to:

Politics

* a supporter of liberalism

** Liberalism by country

* an adherent of a Liberal Party

* Liberalism (international relations)

* Sexually liberal feminism

* Social liberalism

Arts, entertainment and m ...

and an opponent of both corporatist and communist theories, the latter of which Windrip's administration suppresses. Jessup's participation in the organization results in the publication of a periodical called ''The Vermont Vigilance'', in which he writes editorials decrying Windrip's abuses of power. (Even before Windrip's election, Jessup brings up the possibility of fascism

Fascism is a far-right, authoritarian, ultra-nationalist political ideology and movement,: "extreme militaristic nationalism, contempt for electoral democracy and political and cultural liberalism, a belief in natural social hierarchy an ...

coming to America, but Francis Tasbrough, the wealthy owner of a quarry in Jessup's hometown of Fort Beulah, Vermont, dismisses it with the remark that it simply "can't happen here", hence the novel's title.)

Shad Ledue, the local district commissioner and Jessup's former hired man, resents his old employer. Ledue eventually discovers Jessup's actions and has him sent to a concentration camp. Ledue subsequently terrorizes Jessup's family and particularly his daughter Sissy, whom he unsuccessfully attempts to seduce. Sissy discovers evidence of corrupt dealings on the part of Ledue, which she exposes to Francis Tasbrough, a one-time friend of Jessup and Ledue's superior in the administrative hierarchy. Tasbrough has Ledue imprisoned in the same camp as Jessup, where inmates Ledue had sent there organize Ledue's murder. After a relatively brief incarceration, Jessup escapes when his friends bribe one of the camp guards. He flees to Canada, where he rejoins the New Underground. He later serves the organization as a spy, passing along information and urging locals to resist Windrip.

In time, Windrip's hold on power weakens as the economic prosperity he promised does not materialize, and increased numbers of disillusioned Americans, including Vice President Perley Beecroft, flee to both Canada and Mexico. Windrip also angers his Secretary of State, Lee Sarason, who had served earlier as his chief political operative and adviser. Sarason and Windrip's other lieutenants, including General Dewey Haik, seize power and exile the president to France. Sarason succeeds Windrip, but his extravagant and relatively weak rule creates a power vacuum in which Haik and others vie for power. In a bloody putsch, Haik leads a party of military supporters into the White House

The White House is the official residence and workplace of the president of the United States. It is located at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue NW in Washington, D.C., and has been the residence of every U.S. president since John Adams in 1800. ...

, kills Sarason and his associates, and proclaims himself president. The two coups cause a slow erosion of Corpo power, and Haik's government desperately tries to arouse patriotism by launching an unjustified invasion of Mexico. After slandering Mexico in state-run newspapers, Haik orders a mass conscription of young American men for the invasion of that country, infuriating many who had until then been staunch Corpo loyalists. Riots and rebellions break out across the country, with many realizing the Corpos have misled them.

General Emmanuel Coon, among Haik's senior officers, defects to the opposition with a large portion of his army, giving strength to the resistance movement. Although Haik remains in control of much of the country, civil war

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government policies ...

soon breaks out as the resistance tries to consolidate its grasp on the Midwest

The Midwestern United States, also referred to as the Midwest or the American Midwest, is one of four Census Bureau Region, census regions of the United States Census Bureau (also known as "Region 2"). It occupies the northern central part of ...

. The novel ends after the beginning of the conflict, with Jessup working as an agent for the New Underground in Corpo-occupied portions of southern Minnesota

Minnesota () is a state in the upper midwestern region of the United States. It is the 12th largest U.S. state in area and the 22nd most populous, with over 5.75 million residents. Minnesota is home to western prairies, now given over to ...

.

Reception

Reviewers at the time, and historians and literary critics ever since, have emphasized the resemblance to Louisiana politicianHuey Long

Huey Pierce Long Jr. (August 30, 1893September 10, 1935), nicknamed "the Kingfish", was an American politician who served as the 40th governor of Louisiana from 1928 to 1932 and as a United States senator from 1932 until his assassination ...

, who used strong-arm political tactics and who was building a nationwide "Share Our Wealth

Share Our Wealth was a movement that began in February 1934, during the Great Depression, by Huey Long, a governor and later United States Senator from Louisiana. Long first proposed the plan in a national radio address, which is now referred t ...

" organization in preparing to run for president in the 1936 election. Long was assassinated in 1935 just prior to the novel's publication.

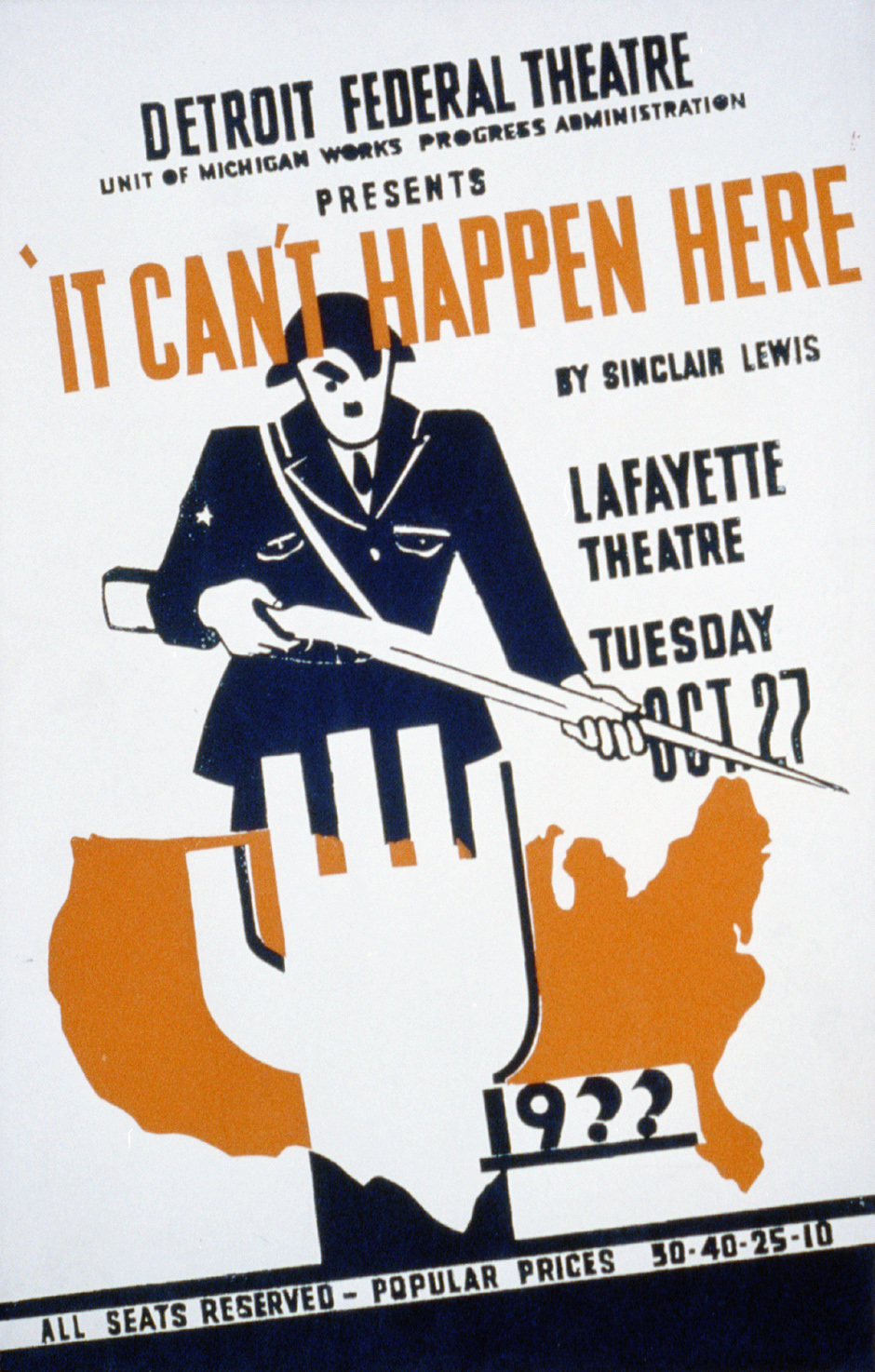

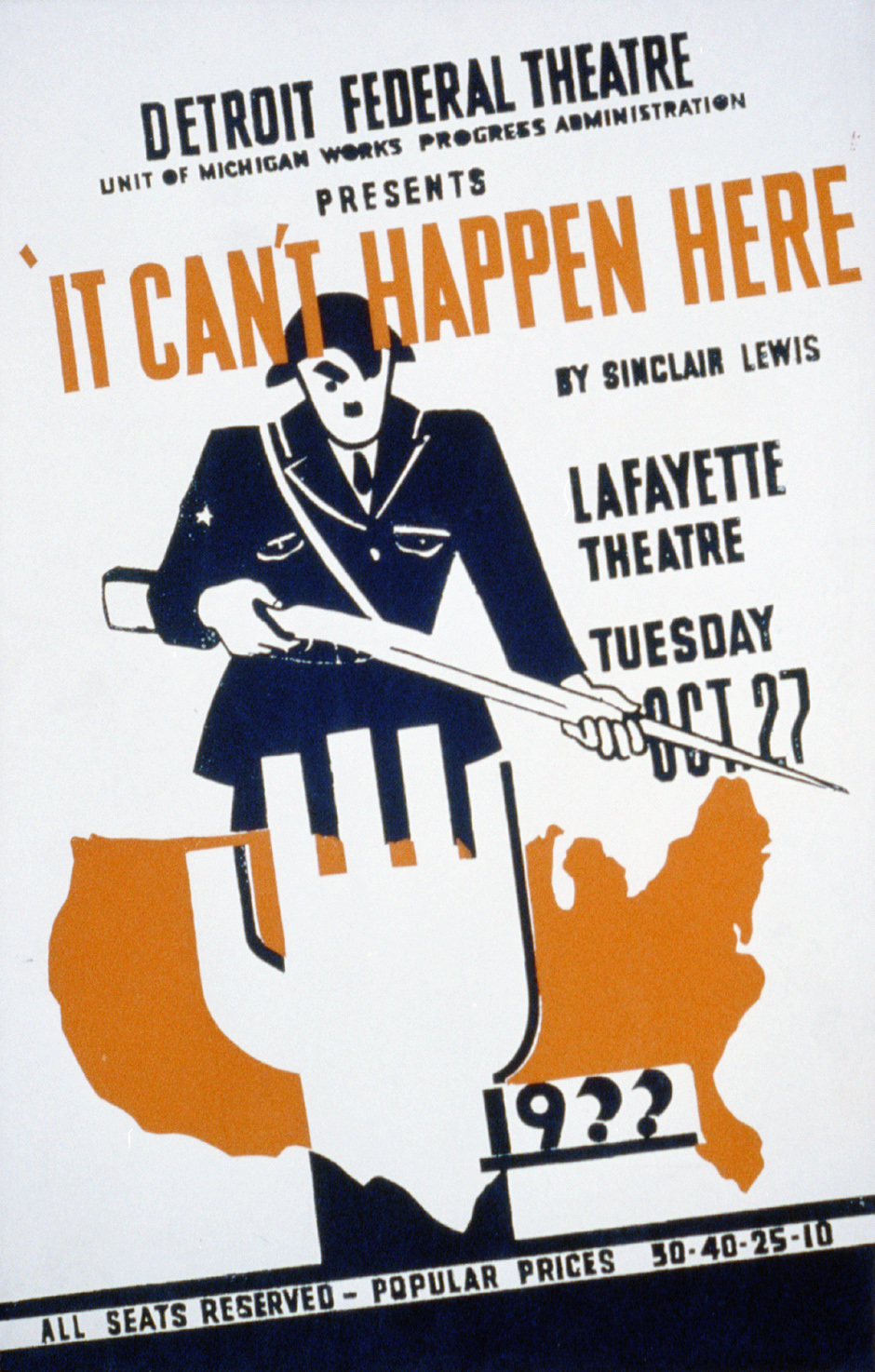

According to Boulard (1998), "the most chilling and uncanny treatment of Huey by a writer came with Sinclair Lewis's ''It Can't Happen Here''." Lewis portrayed a genuine U.S. dictator on the Hitler model. Starting in 1936, the

According to Boulard (1998), "the most chilling and uncanny treatment of Huey by a writer came with Sinclair Lewis's ''It Can't Happen Here''." Lewis portrayed a genuine U.S. dictator on the Hitler model. Starting in 1936, the Works Progress Administration

The Works Progress Administration (WPA; renamed in 1939 as the Work Projects Administration) was an American New Deal agency that employed millions of jobseekers (mostly men who were not formally educated) to carry out public works projects, i ...

, a New Deal

The New Deal was a series of programs, public work projects, financial reforms, and regulations enacted by President Franklin D. Roosevelt in the United States between 1933 and 1939. Major federal programs agencies included the Civilian Cons ...

agency, performed the stage adaptation across the country; Lewis had the goal of hurting Long's chances in the 1936 election.

Keith Perry argues that the key weakness of the novel is not that he decks out U.S. politicians with sinister European touches, but that he finally conceives of fascism and totalitarianism in terms of traditional U.S. political models rather than seeing them as introducing a new kind of society and a new kind of regime. Windrip is less a Nazi

Nazism ( ; german: Nazismus), the common name in English for National Socialism (german: Nationalsozialismus, ), is the far-right totalitarian political ideology and practices associated with Adolf Hitler and the Nazi Party (NSDAP) in ...

than a con-man-plus-Rotarian

Rotary International is one of the largest service organizations in the world. Its stated mission is to "provide service to others, promote integrity, and advance world understanding, goodwill, and peace through hefellowship of business, prof ...

, a manipulator who knows how to appeal to people's desperation, but neither he nor his followers are in the grip of the kind of world-transforming ideology like Hitler's Nazism.

Adaptations

Stage

In 1936, Lewis and John C. Moffitt wrote a stage version, also titled ''It Can't Happen Here'', which is still produced. The stage version premiered on October 27, 1936, in 21 U.S. theaters in 17 states simultaneously, in productions sponsored by theFederal Theater Project

The Federal Theatre Project (FTP; 1935–1939) was a theatre program established during the Great Depression as part of the New Deal to fund live artistic performances and entertainment programs in the United States. It was one of five Federal Pro ...

.

The Z Collective, a San Francisco theater company, adapted the novel for the stage, producing it both in 1989 and 1992. In 2004, Z Space

Z Space is a regional theater and performing arts company located in the Mission District of San Francisco, California. Z Space is one of the leading laboratories for developing new voices, new works, and new opportunities in the American theater. ...

adapted the Collective's script into a radio drama that was broadcast on the Pacifica radio network on the anniversary of the Federal Theater Project's original premiere.

A new stage adaptation by Tony Taccone

Tony Taccone (born July 4, 1951) is an American theater director, and the former Artistic Director of Berkeley Repertory Theatre in Berkeley, California.

Early life

Tony Taccone was born on July 4, 1951 in Queens, New York, to an Italian-America ...

and Bennett S. Cohen premiered at the Berkeley Repertory Theatre

Berkeley Repertory Theatre is a regional theater company located in Berkeley, California. It runs seven productions each season from its two stages in Downtown Berkeley.

History

The company was founded in 1968, as the East Bay's first resident p ...

in September 2016.

Unfinished film

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer

Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Studios Inc., also known as Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer Pictures and abbreviated as MGM, is an American film, television production, distribution and media company owned by amazon (company), Amazon through MGM Holdings, founded o ...

(MGM) purchased the rights in late 1935 for a reported $200,000 from seeing the galley proof

In printing and publishing, proofs are the preliminary versions of publications meant for review by authors, editors, and proofreaders, often with extra-wide margins. Galley proofs may be uncut and unbound, or in some cases electronically tran ...

s, with Lucien Hubbard

Lucien Hubbard (December 22, 1888 – December 31, 1971) was a film producer and screenwriter.

Biography

Hubbard is best known for producing the 1927 film ''Wings (1927 film), Wings'', for which he received the first Academy Award for Best Pic ...

(''Wings

A wing is a type of fin that produces lift while moving through air or some other fluid. Accordingly, wings have streamlined cross-sections that are subject to aerodynamic forces and act as airfoils. A wing's aerodynamic efficiency is expresse ...

'') as the producer. By early 1936, screenwriter Sidney Howard

Sidney Coe Howard (June 26, 1891 – August 23, 1939) was an American playwright, dramatist and screenwriter. He received the Pulitzer Prize for Drama in 1925 and a posthumous Academy Award in 1940 for the screenplay for ''Gone with the Wind''. ...

completed an adaptation

In biology, adaptation has three related meanings. Firstly, it is the dynamic evolutionary process of natural selection that fits organisms to their environment, enhancing their evolutionary fitness. Secondly, it is a state reached by the po ...

, his third of Lewis's novels. J. Walter Ruben

Jacob Walter Ruben (August 14, 1899 – September 4, 1942) was an American screenwriter, film director and producer. He wrote for more than 30 films between 1926 and 1942. He also directed 19 films between 1931 and 1940. His great-grandson i ...

was named to direct the film with the cast headed by Lionel Barrymore

Lionel Barrymore (born Lionel Herbert Blythe; April 28, 1878 – November 15, 1954) was an American actor of stage, screen and radio as well as a film director. He won an Academy Award for Best Actor for his performance in ''A Free Soul'' (1931) ...

, Walter Connolly

Walter Connolly (April 8, 1887 – May 28, 1940) was an American character actor who appeared in almost 50 films between 1914 and 1939. His best known film is ''It Happened One Night'' (1934).

Early years

Connolly attended St. Xavier Coll ...

, Virginia Bruce

Virginia Bruce (born Helen Virginia Briggs; September 29, 1910 – February 24, 1982) was an American actress and singer.

Early life

Bruce was born in Minneapolis, Minnesota. As an infant she moved with her parents, Earil and Margaret Briggs, ...

, and Basil Rathbone

Philip St. John Basil Rathbone MC (13 June 1892 – 21 July 1967) was a South African-born English actor. He rose to prominence in the United Kingdom as a Shakespearean stage actor and went on to appear in more than 70 films, primarily costume ...

. Studio head Louis B. Mayer

Louis Burt Mayer (; born Lazar Meir; July 12, 1882 or 1884 or 1885 – October 29, 1957) was a Canadian-American film producer and co-founder of Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studios (MGM) in 1924. Under Mayer's management, MGM became the film industr ...

indefinitely postponed production, citing costs, to the publicly announced pleasure of the Nazi regime

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

in Germany. Lewis and Howard countered that financial reason with information pointing to Berlin's and Rome's influence on movies. Will H. Hays

William Harrison Hays Sr. (; November 5, 1879 – March 7, 1954) was an American Republican politician.

As chairman of the Republican National Committee from 1918–1921, Hays managed the successful 1920 presidential campaign of Warren G. Ha ...

, responsible for the enforcement of the Motion Picture Production Code

The Motion Picture Production Code was a set of industry guidelines for the self-censorship of content that was applied to most motion pictures released by major studios in the United States from 1934 to 1968. It is also popularly known as the ...

, had notified Mayer of potential problems in the German market. Joseph Breen

Joseph Ignatius Breen (October 14, 1888 – December 5, 1965) was an American film censor with the Motion Picture Producers and Distributors of America who applied the Hays Code to film production.Staff report (December 8, 1965). Joseph I. ...

, head of the Production Code Administration

The Motion Picture Association (MPA) is an American trade association representing the Major film studios#Present, five major film studios of the United States, as well as the video streaming service Netflix. Founded in 1922 as the Motion Pic ...

department under Hays, thought the script was too "anti-fascist" and "so filled with dangerous material".

In December 1938, Charlie Chaplin

Sir Charles Spencer Chaplin Jr. (16 April 188925 December 1977) was an English comic actor, filmmaker, and composer who rose to fame in the era of silent film. He became a worldwide icon through his screen persona, the Tramp, and is consider ...

announced his next movie would satirize Hitler (''The Great Dictator

''The Great Dictator'' is a 1940 American anti-war political satire black comedy film written, directed, produced, scored by, and starring British comedian Charlie Chaplin, following the tradition of many of his other films. Having been the onl ...

''). MGM's Hubbard "dusted off the script" in January, but the "idea of a dictator ruling America" had now been discussed in public for years. Hubbard rewrote a new climax, "showing a dictatorship in Washington and showing it being kicked out by disgruntled Americans as soon as they realized what had happened." The film was placed back on the production schedule for the third time with shooting starting in June and Lewis Stone

Lewis Shepard Stone (November 15, 1879 – September 12, 1953) was an American film actor. He spent 29 years as a contract player at Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer and was best known for his portrayal of Judge James Hardy in the studio's popular '' Andy ...

playing Doremus Jessup. By July 1939, MGM "admitted it would not make the movie after all" to some criticism.

Television

The 1968television movie

A television film, alternatively known as a television movie, made-for-TV film/movie or TV film/movie, is a feature-length film that is produced and originally distributed by or to a television network, in contrast to theatrical films made for ...

''Shadow on the Land

''Shadow on the Land'', also known as ''United States: It Can't Happen Here'', is a 1968 television film which aired on ABC. It was adapted from the 1935 Sinclair Lewis novel ''It Can't Happen Here'' by Nedrick Young, and directed by Richard C. S ...

'', which also went by the title ''United States: It Can't Happen Here'', was produced by Screen Gems

Screen Gems is an American brand name used by Sony Pictures' Sony Pictures Entertainment Motion Picture Group, a subsidiary of Japanese multinational conglomerate, Sony Group Corporation. It has served several different purposes for its parent ...

as a backdoor pilot

A television pilot (also known as a pilot or a pilot episode and sometimes marketed as a tele-movie), in United States television, is a standalone episode of a television series that is used to sell a show to a television network or other distri ...

for a series

Series may refer to:

People with the name

* Caroline Series (born 1951), English mathematician, daughter of George Series

* George Series (1920–1995), English physicist

Arts, entertainment, and media

Music

* Series, the ordered sets used in ...

. The TV movie, a thriller which takes place following the fascist takeover, is often cited as an adaptation of Lewis's novel but does not credit the novel.

Inspired by the book, director–producer Kenneth Johnson in 1982 scripted a miniseries entitled ''Storm Warnings''. NBC executives, to whom Johnson presented the script, rejected the original, which they considered too cerebral for the average American viewer. In order to make the script more marketable, ''Storm Warnings'' was revised into a far less subtle alien invasion

The alien invasion or space invasion is a common feature in science fiction stories and film, in which extraterrestrial lifeforms invade the Earth either to exterminate and supplant human life, enslave it under an intense state, harvest people ...

story in which the invaders initially pose as humanity's friends. The new script formed the basis for the popular miniseries ''V'', which premiered May 3, 1983.

Legacy

Since its publication, ''It Can't Happen Here'' has been seen as acautionary tale

A cautionary tale is a tale told in folklore to warn its listener of a danger. There are three essential parts to a cautionary tale, though they can be introduced in a large variety of ways. First, a taboo or prohibition is stated: some act, lo ...

, starting with the 1936 presidential election and potential candidate Huey Long.

In retrospect, Franklin D. Roosevelt's internment of Japanese Americans

Internment is the imprisonment of people, commonly in large groups, without charges or intent to file charges. The term is especially used for the confinement "of enemy citizens in wartime or of terrorism suspects". Thus, while it can simply ...

during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

has been used as an example of "It can happen here".

Frank Zappa

Frank Vincent Zappa (December 21, 1940 – December 4, 1993) was an American musician, composer, and bandleader. His work is characterized by wikt:nonconformity, nonconformity, Free improvisation, free-form improvisation, sound experimen ...

and The Mothers of Invention

The Mothers of Invention (also known as The Mothers) was an American rock band from California. Formed in 1964, their work is marked by the use of sonic experimentation, innovative album art, and elaborate live shows.

Originally an R&B band ...

released their first album ''Freak Out!

''Freak Out!'' is the debut studio album by American rock band the Mothers of Invention, released on June 27, 1966, by Verve Records. Often cited as one of rock music's first concept albums, it is a satirical expression of frontman Frank Zappa ...

'' in 1966 with the song "It Can't Happen Here".

In May 1973, in the middle of the Watergate scandal

The Watergate scandal was a major political scandal in the United States involving the administration of President Richard Nixon from 1972 to 1974 that led to Nixon's resignation. The scandal stemmed from the Nixon administration's continual ...

, Knight Newspapers published an ad in their own and other publications, headlined "It Can't Happen Here" and emphasizing the importance of free press: "There is a struggle going on in this country. It is not just a fight by reporters and editors to protect their sources. It is a fight to protect the public's right to know. ..It can't happen here as long as the press remains an open conduit through which public information flows." Herbert Mitgang Herbert Mitgang (January 20, 1920 – November 21, 2013) was an American author, editor, journalist, playwright, and producer of television news documentaries.

Life

Born in Manhattan, he graduated with a law degree from what is now St. John's Uni ...

in his op-ed

An op-ed, short for "opposite the editorial page", is a written prose piece, typically published by a North-American newspaper or magazine, which expresses the opinion of an author usually not affiliated with the publication's editorial board. O ...

piece said "The headline of this ad is the title of a novel that keeps insinuating itself these days, not because of its literary qualities but because of its prescience." And that Lewis's point was "that home‐grown hypocrisy leads to a nice brand of home‐grown authoritarianism."

Joe Conason

Joe Conason (born January 25, 1954) is an American journalist, author and liberal political commentator. He is the founder and editor-in-chief of ''The National Memo'', a daily political newsletter and website that features breaking news and comme ...

's non-fiction book '' It Can Happen Here: Authoritarian Peril in the Age of Bush'' (2007) frequently quotes Lewis's book in relation to the presidency of George W. Bush

George W. Bush's tenure as the 43rd president of the United States began with his first inauguration on January 20, 2001, and ended on January 20, 2009. Bush, a Republican from Texas, took office following a narrow victory over Democratic i ...

.

Presidency of Donald Trump

Several writers have compared thedemagogue

A demagogue (from Greek , a popular leader, a leader of a mob, from , people, populace, the commons + leading, leader) or rabble-rouser is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, e ...

Buzz Windrip to Donald Trump

Donald John Trump (born June 14, 1946) is an American politician, media personality, and businessman who served as the 45th president of the United States from 2017 to 2021.

Trump graduated from the Wharton School of the University of Pe ...

. Michael Paulson Michael Paulson is an American journalist. From 2000 to 2010 he covered religion for The Boston Globe. Since 2010, he has worked at the New York Times, where he initially continued his religion coverage. His work there reflected his early politics ...

wrote in ''The New York Times

''The New York Times'' (''the Times'', ''NYT'', or the Gray Lady) is a daily newspaper based in New York City with a worldwide readership reported in 2020 to comprise a declining 840,000 paid print subscribers, and a growing 6 million paid ...

'' that the Berkeley Repertory Theatre's 2016 rendition of the play aimed to provoke discussion about Trump's presidential candidacy. Writing for ''The Guardian

''The Guardian'' is a British daily newspaper. It was founded in 1821 as ''The Manchester Guardian'', and changed its name in 1959. Along with its sister papers ''The Observer'' and ''The Guardian Weekly'', ''The Guardian'' is part of the Gu ...

'', Jules Stewart discussed the similarities between Trump's America with the country as depicted in the book. In ''Salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon, a venue for cosmetic treatments

* French term for a drawing room, an architectural space in a home

* Salon (gathering), a meeting for learning or enjoyment

Arts and entertainment

* Salon (P ...

'', Malcolm Harris stated: "Like Trump, Windrip uses a lack of tact as a way to distinguish himself" and "The social forces that Windrip and Trump invoke aren’t funny, they’re murderous."Malcolm Harris.It really can happen here: The novel that foreshadowed Donald Trump’s authoritarian appeal

. ''Salon'', September 29, 2015. In ''

The Washington Post

''The Washington Post'' (also known as the ''Post'' and, informally, ''WaPo'') is an American daily newspaper published in Washington, D.C. It is the most widely circulated newspaper within the Washington metropolitan area and has a large nati ...

'', Carlos Lozada compared Trump to Windrip, opining that "it is impossible to miss the similarities between Trump and totalitarian figures in American literature." Jacob Weisberg wrote in ''Slate

Slate is a fine-grained, foliated, homogeneous metamorphic rock derived from an original shale-type sedimentary rock composed of clay or volcanic ash through low-grade regional metamorphism. It is the finest grained foliated metamorphic rock. ...

'' that one "can’t read Lewis' novel today without flashes of Trumpian recognition." Following the results of the 2016 United States presidential election

The 2016 United States presidential election was the 58th quadrennial presidential election, held on Tuesday, November 8, 2016. The Republican ticket of businessman Donald Trump and Indiana governor Mike Pence defeated the Democratic ticket ...

, sales of ''It Can't Happen Here'' surged significantly, and it appeared on Amazon.com

Amazon.com, Inc. ( ) is an American multinational technology company focusing on e-commerce, cloud computing, online advertising, digital streaming, and artificial intelligence. It has been referred to as "one of the most influential economi ...

's list of bestselling books. Penguin Modern Classics

Penguin Classics is an imprint of Penguin Books under which classic works of literature are published in English, Spanish, Portuguese, and Korean among other languages. Literary critics see books in this series as important members of the Wester ...

released a new edition of the novel on January 20, 2017, the same day as the inauguration of Donald Trump

The inauguration of Donald Trump as the 45th president of the United States marked the commencement of Donald Trump's term as president and Mike Pence as vice president. An estimated 300,000 to 600,000 people attended the public ceremony hel ...

.

In 2018, HarperCollins

HarperCollins Publishers LLC is one of the Big Five English-language publishing companies, alongside Penguin Random House, Simon & Schuster, Hachette, and Macmillan. The company is headquartered in New York City and is a subsidiary of News Cor ...

published ''Can It Happen Here?: Authoritarianism in America'', a collection of essays about the prospect of authoritarianism in the United States, edited by Cass Sunstein

Cass Robert Sunstein (born September 21, 1954) is an American legal scholar known for his studies of constitutional law, administrative law, environmental law, law and behavioral economics. He is also ''The New York Times'' best-selling author of ...

.

In 2019, Robert Evans

Robert Evans (born Robert J. Shapera; June 29, 1930October 26, 2019) was an American film producer, studio executive, and actor, best known for his work on '' Rosemary's Baby'' (1968), ''Love Story'' (1970), ''The Godfather'' (1972), and ''Chi ...

produced the podcast series ''It Could Happen Here'', which speculated on the causes and consequences of a hypothetical second American Civil War.

In 2021, New York University Press

New York University Press (or NYU Press) is a university press that is part of New York University.

History

NYU Press was founded in 1916 by the then chancellor of NYU, Elmer Ellsworth Brown.

Directors

* Arthur Huntington Nason, 1916–1932 ...

published a book '' It Can Happen Here: White Power and the Rising Threat of Genocide in the US'' by genocide scholar Alexander Laban Hinton

Alexander Laban Hinton is an anthropologist whose work focuses on genocide, mass violence, extremism, transitional justice, and human rights. He has written extensively on the Cambodian genocide and, in 2016, was an expert witness at the Khmer ...

. Hinton argued that "there is a real risk of violent atrocities happening in the United States".

See also

;Books * Dystopian novel set in a near-future fundamentalist New England * Dystopian science-fiction novel sometimes said to predict the rise of Donald Trump's presidency. * Nonfiction book * Dick, Philip K. (1962). ''The Man in the High Castle

''The Man in the High Castle'' (1962), by Philip K. Dick, is an alternative history novel wherein the Axis Powers won World War II. The story occurs in 1962, fifteen years after the end of the war in 1947, and depicts the political intrigues b ...

''. A post World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

alternative history, where Nazi Germany

Nazi Germany (lit. "National Socialist State"), ' (lit. "Nazi State") for short; also ' (lit. "National Socialist Germany") (officially known as the German Reich from 1933 until 1943, and the Greater German Reich from 1943 to 1945) was ...

and Imperial Japan

The also known as the Japanese Empire or Imperial Japan, was a historical nation-state and great power that existed from the Meiji Restoration in 1868 until the enactment of the post-World War II 1947 constitution and subsequent forma ...

are in control of America and the world.

* Book about a fascist Britain

* American dystopian novel

* British graphic novel about a terrorist overthrowing a post-apocalyptic fascist Britain

* Alternate history

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, altern ...

novel in which Charles Lindbergh

Charles Augustus Lindbergh (February 4, 1902 – August 26, 1974) was an American aviator, military officer, author, inventor, and activist. On May 20–21, 1927, Lindbergh made the first nonstop flight from New York City to Paris, a distance o ...

defeats Roosevelt in 1940 and begins antisemitic

Antisemitism (also spelled anti-semitism or anti-Semitism) is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who holds such positions is called an antisemite. Antisemitism is considered to be a form of racism.

Antis ...

and pro-German policies

* Collection of essays

;Events

* If Day

If Day (french: "Si un jour", "If one day") was a simulated Nazi German invasion and occupation of the Canadian city of Winnipeg, Manitoba, and surrounding areas on 19 February 1942, during the Second World War. It was organized as a war bond pr ...

(19 February 1942), a simulated Nazi German invasion and occupation of Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada

;Films & Television

* ''It Happened Here

''It Happened Here'' (also known as ''It Happened Here: The Story of Hitler's England'') is a 1964 British black-and-white film written, produced and directed by Kevin Brownlow and Andrew Mollo, who began work on the film as teenagers. The film ...

'' (1964; also known as ''It Happened Here: The Story of Hitler's England''), a black-and white film about a fictitious fascist government in Britain during World War II

* ''The Plot Against America

''The Plot Against America'' is a novel by Philip Roth published in 2004. It is an alternative history in which Franklin D. Roosevelt is defeated in the presidential election of 1940 by Charles Lindbergh. The novel follows the fortunes of the R ...

'', a 2020 alternate history drama television miniseries by David Simon

David Judah Simon (born February 9, 1960) is an American author, journalist, screenwriter, and producer best known for his work on ''The Wire'' (2002–08).

He worked for ''The Baltimore Sun'' City Desk for twelve years (1982–95), wrote '' Hom ...

and Ed Burns

Edward P. Burns (born January 29, 1946) is an American screenwriter, novelist, and producer. He has worked closely with writing partner David Simon. For HBO, they have collaborated on ''The Corner,'' ''The Wire,'' ''Generation Kill'', ''The Pl ...

, based on the novel of the same name

References

Bibliography * * * * *Further reading

* * * * Doctoral Dissertation. * "Sinclair Lewis's 1935 novel 'It Can't Happen Here' envisioned an America in thrall to a homespun fascist dictator. Newly reissued, it's as unsettling a read as ever."External links

* * {{Authority control 1935 American novels 1935 science fiction novels American novels adapted into films American novels adapted into plays American political novels American satirical novels Doubleday, Doran books Dystopian novels Huey Long Novels about totalitarianism Novels by Sinclair Lewis Novels set in Vermont Novels set in Washington, D.C. Fiction set in 1936 Novels set in the 1930s Second American Civil War speculative fiction