The Israeli–Palestinian conflict is one of the world's most enduring conflicts, beginning in the mid-20th century.

Various attempts have been made to resolve the conflict as part of the

Israeli–Palestinian peace process

The Israeli–Palestinian peace process refers to the intermittent discussions held by various parties and proposals put forward in an attempt to resolve the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Since the 1970s, there has been a parallel ef ...

, alongside other efforts to resolve the broader

Arab–Israeli conflict

The Arab–Israeli conflict is an ongoing intercommunal phenomenon involving political tension, military conflicts, and other disputes between Arab countries and Israel, which escalated during the 20th century, but had mostly faded out by the ...

. Public declarations of claims to a

Jewish homeland

A homeland for the Jewish people is an idea rooted in Jewish history, religion, and culture. The Jewish aspiration to return to Zion, generally associated with divine redemption, has suffused Jewish religious thought since the destruction ...

in

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

, including the

First Zionist Congress

The First Zionist Congress ( he, הקונגרס הציוני הראשון) was the inaugural congress of the Zionist Organization (ZO) held in Basel (Basle), from August 29 to August 31, 1897. 208 delegates and 26 press correspondents attende ...

of 1897 and the

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

of 1917, created early tensions in the region. Following

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

, the

Mandate for Palestine

The Mandate for Palestine was a League of Nations mandate for British administration of the territories of Palestine and Transjordan, both of which had been conceded by the Ottoman Empire following the end of World War I in 1918. The manda ...

included a binding obligation for the "establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people". Tensions grew into

open sectarian conflict between Jews and Arabs. The 1947

United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine

The United Nations Partition Plan for Palestine was a proposal by the United Nations, which recommended a partition of Mandatory Palestine at the end of the British Mandate. On 29 November 1947, the UN General Assembly adopted the Plan as Re ...

was never implemented and provoked the

1947–1949 Palestine War

The 1948 Palestine war was fought in the territory of what had been, at the start of the war, British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. It is known in Israel as the War of Independence ( he, מלחמת העצמאות, ''Milkhemet Ha'Atzma'ut'') and ...

. The current Israeli-Palestinian status quo began following Israeli

military occupation

Military occupation, also known as belligerent occupation or simply occupation, is the effective military control by a ruling power over a territory that is outside of that power's sovereign territory.Eyāl Benveniśtî. The international law ...

of the

Palestinian territories

The Palestinian territories are the two regions of the former British Mandate for Palestine that have been militarily occupied by Israel since the Six-Day War of 1967, namely: the West Bank (including East Jerusalem) and the Gaza Strip. The I ...

in the 1967

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

.

Progress was made towards a

two-state solution

The two-state solution to the Israeli–Palestinian conflict envisions an independent State of Palestine alongside the State of Israel, west of the Jordan River. The boundary between the two states is still subject to dispute and negotiation ...

with the

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords are a pair of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): the Oslo I Accord, signed in Washington, D.C., in 1993; of 1993–1995, but occupation and

blockade of the Gaza Strip

The blockade of the Gaza Strip is the ongoing land, air, and sea blockade of the Gaza Strip imposed by Israel and Egypt temporarily in 2005–2006 and permanently from 2007 onwards, following the Israeli disengagement from Gaza.

The block ...

since 2005, continues. Final status issues include

the status of Jerusalem,

Israeli settlement

Israeli settlements, or Israeli colonies, are civilian communities inhabited by Israeli citizens, overwhelmingly of Jewish ethnicity, built on lands occupied by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community considers Israeli se ...

s, borders, security and water rights as well as

Palestinian freedom of movement

Restrictions on the movement of Palestinians in the Israeli-occupied territories by Israel is an issue in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. According to B'Tselem, following the 1967 war, the occupied territories were proclaimed closed milit ...

,

and the

Palestinian right of return

The Palestinian right of return is the political position or principle that Palestinian refugees, both first-generation refugees (c. 30,000 to 50,000 people still alive )"According to the United Nations Relief and Works Agency – the main body ...

. The violence of the conflict in the region—rich in sites of historic, cultural, and religious interest worldwide—has been the subject of numerous international conferences dealing with historic rights, security issues, and human rights; and has been a factor hampering tourism in, and general access to, areas that are hotly contested.

The majority of peace efforts have been centred around the two-state solution, which involves the establishment of an

independent Palestinian state alongside Israel. However, public support for a two-state solution, which formerly enjoyed support from both

Israeli Jews

Israeli Jews or Jewish Israelis ( he, יהודים ישראלים, translit=Yehudim Yisraelim) are Israeli citizens and nationals who are Jewish through either their Jewish ethnicity and/or their adherence to Judaism. The term also includes ...

and

Palestinians

Palestinians ( ar, الفلسطينيون, ; he, פָלַסְטִינִים, ) or Palestinian people ( ar, الشعب الفلسطيني, label=none, ), also referred to as Palestinian Arabs ( ar, الفلسطينيين العرب, label=non ...

,

[ Dershowitz, Alan. '' The Case for Peace: How the Arab–Israeli Conflict Can Be Resolved''. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Inc., 2005] has dwindled in recent years.

Within Israeli and Palestinian society, the conflict generates a

wide variety of views and opinions. Since its

inception

''Inception'' is a 2010 science fiction action film written and directed by Christopher Nolan, who also produced the film with Emma Thomas, his wife. The film stars Leonardo DiCaprio as a professional thief who steals information by infiltr ...

, the

conflict's casualties have not been restricted to combatants, with a large number of civilian fatalities on both sides. The two-state solution remains the most popular option among Israelis, although its popularity has greatly fluctuated over the previous three decades.

Israeli Jews are divided along ideological lines, and many favor maintaining the status quo.

Most Palestinians reject both two-state and one-state solutions as of 2022; many believe that the two-state solution is no longer practical. Most Palestinians support armed attacks against Israelis within Israel as a means of ending the occupation.

Mutual distrust and significant disagreements are deep over basic issues, as is the reciprocal skepticism about the other side's commitment to upholding obligations in an eventual bilateral agreement. Since 2006, the Palestinian side has been fractured by conflict between

Fatah

Fatah ( ar, فتح '), formerly the Palestinian National Liberation Movement, is a Palestinian nationalist social democratic political party and the largest faction of the confederated multi-party Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and ...

, the traditionally dominant party and its later electoral challenger,

Hamas

Hamas (, ; , ; an acronym of , "Islamic Resistance Movement") is a Palestinian Sunni-Islamic fundamentalist, militant, and nationalist organization. It has a social service wing, Dawah, and a military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Bri ...

, a militant Islamist group that gained control on Gaza.

have been repeated and continuing. Since 2019, the Israeli side has also been experiencing

political upheaval

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

, with four inconclusive legislative elections having been held over a span of two years.

began in July 2013 but were suspended in 2014. Since 2006, Hamas and Israel have fought

four wars,

the most recent in 2021.

The two parties that would engage in any direct negotiation are the

Israeli government

The Cabinet of Israel (officially: he, ממשלת ישראל ''Memshelet Yisrael'') exercises executive authority in the State of Israel. It consists of ministers who are chosen and led by the prime minister. The composition of the governmen ...

and the

Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establ ...

(PLO). The official negotiations are mediated by the

Quartet on the Middle East

The Quartet on the Middle East or Middle East Quartet, sometimes called the Diplomatic Quartet or Madrid Quartet or simply the Quartet, is a foursome of nations and international and supranational entities involved in mediating the Israeli� ...

, which consists of the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

, the

United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

,

Russia

Russia (, , ), or the Russian Federation, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning Eastern Europe and North Asia, Northern Asia. It is the List of countries and dependencies by area, largest country in the ...

, and the

European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

. The

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

, which has proposed

an alternative peace plan, is another important actor.

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

, a founding member of the Arab League, has historically been a key participant in the Arab–Israeli conflict and related negotiations, more so since the

Egypt–Israel peace treaty

The Egypt–Israel peace treaty ( ar, معاهدة السلام المصرية الإسرائيلية, Mu`āhadat as-Salām al-Misrīyah al-'Isrā'īlīyah; he, הסכם השלום בין ישראל למצרים, ''Heskem HaShalom Bein Yisrael ...

. Another equally key participant is

Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, which

annexed the West Bank in 1950 and held it until 1967, relinquishing its territorial claim over it in 1988; the Jordanian royal

Hashemites

The Hashemites ( ar, الهاشميون, al-Hāshimīyūn), also House of Hashim, are the royal family of Jordan, which they have ruled since 1921, and were the royal family of the kingdoms of Hejaz (1916–1925), Syria (1920), and Iraq (1921� ...

are responsible for

custodianship over Islamic holy sites in Jerusalem.

Background

The Israeli–Palestinian conflict has its roots in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, with the birth of major nationalist movements

among the Jews and

among the Arabs, both geared towards attaining sovereignty for their people in the Middle East.

The

Balfour Declaration

The Balfour Declaration was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing its support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine, then an Ottoman regio ...

was a public statement issued by the British government in 1917 during the First World War announcing support for the establishment of a "national home for the Jewish people" in Palestine. The collision between those two movements in southern

Levant

The Levant () is an approximate historical geographical term referring to a large area in the Eastern Mediterranean region of Western Asia. In its narrowest sense, which is in use today in archaeology and other cultural contexts, it is eq ...

upon the emergence of

Palestinian nationalism

Palestinian nationalism is the national movement of the Palestinian people that espouses self-determination and sovereignty over the region of Palestine.de Waart, 1994p. 223 Referencing Article 9 of ''The Palestinian National Charter of 1968' ...

after the

Franco-Syrian War

The Franco-Syrian War took place during 1920 between the Hashemite rulers of the newly established Arab Kingdom of Syria and France. During a series of engagements, which climaxed in the Battle of Maysalun, French forces defeated the forces of th ...

in the 1920s escalated into the

Sectarian conflict in Mandatory Palestine

The intercommunal conflict in Mandatory Palestine was the civil, political and armed struggle between Palestinian Arabs and Jewish Yishuv during the British rule in Mandatory Palestine, beginning from the violent spillover of the Franco-Syrian ...

in 1930s and 1940s, and expanded into the wider

Arab–Israeli conflict

The Arab–Israeli conflict is an ongoing intercommunal phenomenon involving political tension, military conflicts, and other disputes between Arab countries and Israel, which escalated during the 20th century, but had mostly faded out by the ...

later on.

The return of several hard-line Palestinian Arab nationalists, under the emerging leadership of

Haj Amin al-Husseini

Mohammed Amin al-Husseini ( ar, محمد أمين الحسيني 1897

– 4 July 1974) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and Muslim leader in Mandatory Palestine.

Al-Husseini was the scion of the al-Husayni family of Jerusalemite Arab notable ...

, from Damascus to

Mandatory Palestine

Mandatory Palestine ( ar, فلسطين الانتدابية '; he, פָּלֶשְׂתִּינָה (א״י) ', where "E.Y." indicates ''’Eretz Yiśrā’ēl'', the Land of Israel) was a geopolitical entity established between 1920 and 1948 ...

marked the beginning of

Palestinian Arab nationalist struggle towards establishment of a national home for Arabs of

Palestine

__NOTOC__

Palestine may refer to:

* State of Palestine, a state in Western Asia

* Palestine (region), a geographic region in Western Asia

* Palestinian territories, territories occupied by Israel since 1967, namely the West Bank (including East ...

. Amin al-Husseini, the architect of the Palestinian Arab national movement, immediately marked

Jewish national movement and

Jewish immigration to Palestine as the sole enemy to his cause,

He usseiniincited and headed anti-Jewish riots in April 1920. ... He promoted the Muslim character of Jerusalem and ... injected a religious character into the struggle against Zionism

Zionism ( he, צִיּוֹנוּת ''Tsiyyonut'' after ''Zion'') is a Nationalism, nationalist movement that espouses the establishment of, and support for a homeland for the Jewish people centered in the area roughly corresponding to what is ...

. This was the backdrop to his agitation concerning Jewish rights at the Western (Wailing) Wall that led to the bloody riots of August 1929... was the chief organizer of the riots of 1936 and the rebellion from 1937, as well as of the mounting internal terror against Arab opponents.

initiating large-scale riots against the Jews as early as 1920

in Jerusalem and in 1921

in Jaffa. Among the results of the violence was the establishment of the Jewish paramilitary force

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

. In 1929, a series of violent

anti-Jewish riots was initiated by the Arab leadership. The riots resulted in massive Jewish casualties in

Hebron

Hebron ( ar, الخليل or ; he, חֶבְרוֹן ) is a Palestinian. city in the southern West Bank, south of Jerusalem. Nestled in the Judaean Mountains, it lies above sea level. The second-largest city in the West Bank (after East J ...

and

Safed

Safed (known in Hebrew language, Hebrew as Tzfat; Sephardi Hebrew, Sephardic Hebrew & Modern Hebrew: צְפַת ''Tsfat'', Ashkenazi Hebrew pronunciation, Ashkenazi Hebrew: ''Tzfas'', Biblical Hebrew: ''Ṣǝp̄aṯ''; ar, صفد, ''Ṣafad''), i ...

, and the evacuation of Jews from Hebron and Gaza.

In the early 1930s, the Arab national struggle in Palestine had drawn many Arab nationalist militants from across the Middle East, such as

Sheikh Izaddin al-Qassam from Syria, who established the Black Hand militant group and had prepared the grounds for the 1936 Arab revolt. Following the death of al-Qassam at the hands of the British in late 1935, tensions erupted in 1936 into the Arab general strike and general boycott. The strike soon deteriorated into violence and the bloodily repressed

1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine

The 1936–1939 Arab revolt in Palestine, later known as The Great Revolt (''al-Thawra al- Kubra'') or The Great Palestinian Revolt (''Thawrat Filastin al-Kubra''), was a popular nationalist uprising by Palestinian Arabs in Mandatory Palestine a ...

against the British and the Jews.

In the first wave of organized violence, lasting until early 1937, most of the Arab groups were defeated by the British and forced expulsion of much of the Arab leadership was performed. The revolt led to the establishment of the

Peel Commission

The Peel Commission, formally known as the Palestine Royal Commission, was a British Royal Commission of Inquiry, headed by Lord Peel, appointed in 1936 to investigate the causes of unrest in Mandatory Palestine, which was administered by Gre ...

towards partitioning of Palestine, though it was subsequently rejected by the Palestinian Arabs. The two main Jewish leaders,

Chaim Weizmann

Chaim Azriel Weizmann ( he, חיים עזריאל ויצמן ', russian: Хаим Евзорович Вейцман, ''Khaim Evzorovich Veytsman''; 27 November 1874 – 9 November 1952) was a Russian-born biochemist, Zionist leader and Israel ...

and

David Ben-Gurion

David Ben-Gurion ( ; he, דָּוִד בֶּן-גּוּרִיּוֹן ; born David Grün; 16 October 1886 – 1 December 1973) was the primary national founder of the State of Israel and the first prime minister of Israel. Adopting the name ...

, accepted the recommendations but some secondary Jewish leaders did not like it.

The renewed violence, which had sporadically lasted until the beginning of World War II, ended with around 5,000 casualties, mostly from the Arab side. With the eruption of World War II, the situation in Mandatory Palestine calmed down. It allowed a shift towards a more moderate stance among Palestinian Arabs, under the leadership of the Nashashibi clan and even the establishment of the Jewish–Arab

Palestine Regiment

The Palestine Regiment was an infantry regiment of the British Army that was formed in 1942. During the Second World War, the regiment was deployed to Egypt and Cyrenaica, but most of their work consisted of guard duty. Some Palestine Regiment mem ...

under British command, fighting Germans in North Africa. The more radical exiled faction of al-Husseini however tended to cooperation with Nazi Germany, and participated in the establishment of a pro-Nazi propaganda machine throughout the Arab world. Defeat of Arab nationalists in Iraq and subsequent relocation of al-Husseini to Nazi-occupied Europe tied his hands regarding field operations in Palestine, though he regularly demanded that the Italians and the Germans bomb

Tel Aviv

Tel Aviv-Yafo ( he, תֵּל־אָבִיב-יָפוֹ, translit=Tēl-ʾĀvīv-Yāfō ; ar, تَلّ أَبِيب – يَافَا, translit=Tall ʾAbīb-Yāfā, links=no), often referred to as just Tel Aviv, is the most populous city in the G ...

. By the end of World War II, a crisis over the fate of the Holocaust survivors from Europe led to renewed tensions between the

Yishuv

Yishuv ( he, ישוב, literally "settlement"), Ha-Yishuv ( he, הישוב, ''the Yishuv''), or Ha-Yishuv Ha-Ivri ( he, הישוב העברי, ''the Hebrew Yishuv''), is the body of Jewish residents in the Land of Israel (corresponding to the s ...

and the Palestinian Arab leadership. Immigration quotas were established by the British, while on the other hand illegal immigration and Zionist insurgency against the British was increasing.

On 29 November 1947, the

General Assembly of the United Nations

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

adopted

Resolution 181(II) recommending the adoption and implementation of a plan to partition Palestine into an Arab state, a Jewish state and the City of Jerusalem.

[Baum, Noa]

"Historical Time Line for Israel/Palestine."

UMass Amherst. 5 April 2005. 14 March 2013. On the next day, Palestine was already swept by violence. For four months, under continuous Arab provocation and attack, the Yishuv was usually on the defensive while occasionally retaliating. The

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

supported the Arab struggle by forming the volunteer-based

Arab Liberation Army

The Arab Liberation Army (ALA; ar, جيش الإنقاذ العربي ''Jaysh al-Inqadh al-Arabi''), also translated as Arab Salvation Army, was an army of volunteers from Arab countries led by Fawzi al-Qawuqji. It fought on the Arab side in th ...

, supporting the Palestinian Arab

Army of the Holy War

The Army of the Holy War or Holy War Army ( ar, جيش الجهاد المقدس; ''Jaysh al-Jihād al-Muqaddas'') was a Palestinian Arab irregular force in the 1947-48 Palestinian civil war led by Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni and Hasan Salama. The ...

, under the leadership of

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni

Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni ( ar, عبد القادر الحسيني), also spelled Abd al-Qader al-Husseini (1907 – 8 April 1948) was a Palestinian Arab nationalist and fighter who in late 1933 founded the secret militant group known as the Orga ...

and

Hasan Salama

Hasan Salama or Hassan Salameh ( ar, حسن سلامة, ; 1913 – 2 June 1948) was a commander of the Palestinian Holy War Army (''Jaysh al-Jihad al-Muqaddas'', Arabic: ) in the 1948 Palestine War along with Abd al-Qadir al-Husayni.

Biograph ...

. On the Jewish side, the civil war was managed by the major underground militias – the

Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

,

Irgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

and

Lehi

Lehi (; he, לח"י – לוחמי חרות ישראל ''Lohamei Herut Israel – Lehi'', "Fighters for the Freedom of Israel – Lehi"), often known pejoratively as the Stern Gang,"This group was known to its friends as LEHI and to its enemie ...

, strengthened by numerous Jewish veterans of World War II and foreign volunteers. By spring 1948, it was already clear that the Arab forces were nearing a total collapse, while Yishuv forces gained more and more territory, creating a large scale

refugee problem of Palestinian Arabs.

Popular support for the Palestinian Arabs throughout the Arab world led to sporadic violence against Jewish communities of the Middle East and North Africa, creating an opposite

refugee wave.

History

Following the

Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel

The Israeli Declaration of Independence, formally the Declaration of the Establishment of the State of Israel ( he, הכרזה על הקמת מדינת ישראל), was proclaimed on 14 May 1948 ( 5 Iyar 5708) by David Ben-Gurion, the Executive ...

on 14 May 1948, the Arab League decided to intervene on behalf of Palestinian Arabs, marching their forces into former British Palestine, beginning the main phase of the

1948 Arab–Israeli War

The 1948 (or First) Arab–Israeli War was the second and final stage of the 1948 Palestine war. It formally began following the end of the British Mandate for Palestine at midnight on 14 May 1948; the Israeli Declaration of Independence had ...

.

The overall fighting, leading to around 15,000 casualties, resulted in cease-fire and armistice agreements of 1949, with Israel holding much of the former Mandate territory, Jordan occupying and later annexing the

West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

and Egypt taking over the Gaza Strip, where the

All-Palestine Government

, image =

, caption = Flag of the All-Palestine Government

, date = 22 September 1948

, state = All-Palestine Protectorate

, address = Gaza City, All-Palestine Protectorate (Sep.–Dec. 1948) ...

was declared by the Arab League on 22 September 1948.

Through the 1950s, Jordan and Egypt supported the

Palestinian Fedayeen

Palestinian fedayeen (from the Arabic ''fidā'ī'', plural ''fidā'iyūn'', فدائيون) are militants or guerrillas of a nationalist orientation from among the Palestinian people. Most Palestinians consider the fedayeen to be " freedom fig ...

militants' cross-border attacks into Israel, while Israel carried out

reprisal operations

Reprisal operations ( he, פעולות התגמול, ') were raids carried out by the Israel Defense Forces in the 1950s and 1960s in response to frequent fedayeen attacks during which armed Arab militants infiltrated Israel from Syria, Egypt ...

in the host countries. The

1956 Suez Crisis

The Suez Crisis, or the Second Arab–Israeli war, also called the Tripartite Aggression ( ar, العدوان الثلاثي, Al-ʿUdwān aṯ-Ṯulāṯiyy) in the Arab world and the Sinai War in Israel,Also known as the Suez War or 1956 Wa ...

resulted in a short-term Israeli occupation of the Gaza Strip and exile of the

All-Palestine Government

, image =

, caption = Flag of the All-Palestine Government

, date = 22 September 1948

, state = All-Palestine Protectorate

, address = Gaza City, All-Palestine Protectorate (Sep.–Dec. 1948) ...

, which was later restored with Israeli withdrawal. The All-Palestine Government was completely abandoned by Egypt in 1959 and was officially merged into the

United Arab Republic

The United Arab Republic (UAR; ar, الجمهورية العربية المتحدة, al-Jumhūrīyah al-'Arabīyah al-Muttaḥidah) was a sovereign state in the Middle East from 1958 until 1971. It was initially a political union between Eg ...

, to the detriment of the Palestinian national movement.

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

then was put under the authority of the Egyptian military administrator, making it a de facto military occupation. In 1964, however, a new organization, the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO), was established by Yasser Arafat.

It immediately won the support of most Arab League governments and was granted a seat in the

Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

.

The 1967

Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

exerted a significant effect upon Palestinian nationalism, as Israel gained military control of the West Bank from Jordan and the Gaza Strip from Egypt. Consequently, the PLO was unable to establish any control on the ground and established its headquarters in Jordan, home to hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, and supported the Jordanian army during the

War of Attrition

The War of Attrition ( ar, حرب الاستنزاف, Ḥarb al-Istinzāf; he, מלחמת ההתשה, Milhemet haHatashah) involved fighting between Israel and Egypt, Jordan, the Palestine Liberation Organisation (PLO) and their allies from ...

, which included the

Battle of Karameh

The Battle of Karameh ( ar, معركة الكرامة) was a 15-hour military engagement between the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and combined forces of the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO) and the Jordanian Armed Forces (JAF) in the Jor ...

. However, the Palestinian base in Jordan collapsed with the

Jordanian–Palestinian civil war in 1970. The PLO defeat by the Jordanians caused most of the Palestinian militants to relocate to South Lebanon, where they soon took over large areas, creating the so-called "Fatahland".

Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon

The Palestinian insurgency in South Lebanon was a conflict initiated by Palestinian militants based in South Lebanon upon Israel from 1968 and upon Christian Lebanese factions from the mid-1970s, which evolved into the wider Lebanese Civil War ...

peaked in the early 1970s, as Lebanon was used as a base to launch attacks on northern Israel and airplane hijacking campaigns worldwide, which drew Israeli retaliation. During the

Lebanese Civil War

The Lebanese Civil War ( ar, الحرب الأهلية اللبنانية, translit=Al-Ḥarb al-Ahliyyah al-Libnāniyyah) was a multifaceted armed conflict that took place from 1975 to 1990. It resulted in an estimated 120,000 fatalities a ...

, Palestinian militants continued to launch attacks against Israel while also battling opponents within Lebanon. In 1978, the

Coastal Road massacre led to the Israeli full-scale invasion known as

Operation Litani

The 1978 South Lebanon conflict (codenamed Operation Litani by Israel) began after Israel invaded southern Lebanon up to the Litani River in March 1978, in response to the Coastal Road massacre near Tel Aviv by Lebanon-based Palestinian mil ...

. Israeli forces, however, quickly withdrew from Lebanon, and the attacks against Israel resumed. In 1982, following an assassination attempt on one of its diplomats by Palestinians, the Israeli government decided to take sides in the Lebanese Civil War and the

1982 Lebanon War

The 1982 Lebanon War, dubbed Operation Peace for Galilee ( he, מבצע שלום הגליל, or מבצע של"ג ''Mivtsa Shlom HaGalil'' or ''Mivtsa Sheleg'') by the Israeli government, later known in Israel as the Lebanon War or the First L ...

commenced. The initial results for Israel were successful. Most Palestinian militants were defeated within several weeks, Beirut was captured, and the PLO headquarters were evacuated to Tunisia in June by Yasser Arafat's decision.

The first Palestinian uprising began in 1987 as a response to escalating attacks and the endless occupation. By the early 1990s, international efforts to settle the conflict had begun, in light of the success of the Egyptian–Israeli peace treaty of 1982. Eventually, the

Israeli–Palestinian peace process

The Israeli–Palestinian peace process refers to the intermittent discussions held by various parties and proposals put forward in an attempt to resolve the ongoing Israeli–Palestinian conflict. Since the 1970s, there has been a parallel ef ...

led to the

Oslo Accords

The Oslo Accords are a pair of agreements between Israel and the Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO): the Oslo I Accord, signed in Washington, D.C., in 1993; of 1993, allowing the PLO to relocate from Tunisia and take ground in the

West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

and

Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

, establishing the

Palestinian National Authority

The Palestinian National Authority (PA or PNA; ar, السلطة الوطنية الفلسطينية '), commonly known as the Palestinian Authority and officially the State of Palestine, . The peace process also had significant opposition among radical Islamic elements of Palestinian society, such as Hamas and Palestinian Islamic Jihad, who immediately initiated a campaign of attacks targeting Israelis. Following hundreds of casualties and a wave of radical anti-government propaganda, Israeli Prime Minister

Rabin was assassinated by an Israeli fanatic who objected to the peace initiative. This struck a serious blow to the peace process, from which the newly elected government of Israel in 1996 backed off.

Following several years of unsuccessful negotiations, the conflict re-erupted as the

Second Intifada

The Second Intifada ( ar, الانتفاضة الثانية, ; he, האינתיפאדה השנייה, ), also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada ( ar, انتفاضة الأقصى, label=none, '), was a major Palestinian uprising against Israel. ...

in September 2000.

The violence, escalating into an open conflict between the

Palestinian National Security Forces

The Palestinian National Security Forces (NSF; ar, قوات الأمن الوطني الفلسطيني ''Quwwat al-Amn al-Watani al-Filastini'') are the paramilitary security forces of the Palestinian National Authority. The name may either re ...

and the

Israel Defense Forces

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the Israel, State of Israel. It consists of three servic ...

, lasted until 2004/2005 and led to approximately

130 fatalities. In 2005, Israeli Prime Minister Sharon ordered the removal of Israeli settlers and soldiers from Gaza. Israel and its Supreme Court formally declared an end to occupation, saying it "had no effective control over what occurred" in Gaza.

However, the

United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

,

Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human r ...

and many other international bodies and

NGOs

A non-governmental organization (NGO) or non-governmental organisation (see spelling differences) is an organization that generally is formed independent from government. They are typically nonprofit entities, and many of them are active in h ...

continue to consider Israel to be the occupying power of the Gaza Strip as Israel controls Gaza Strip's airspace, territorial waters and controls the movement of people or goods in or out of Gaza by air or sea.

In 2006, Hamas won a plurality of 44% in the

Palestinian parliamentary election. Israel responded it would begin

economic sanctions

Economic sanctions are commercial and financial penalties applied by one or more countries against a targeted self-governing state, group, or individual. Economic sanctions are not necessarily imposed because of economic circumstances—they may ...

unless Hamas agreed to accept prior Israeli-Palestinian agreements, forswear violence, and recognize Israel's right to exist, which Hamas rejected. After internal Palestinian political struggle between Fatah and Hamas erupted into the

Battle of Gaza (2007)

The Battle of Gaza, also referred to as Hamas's takeover of Gaza, was a military conflict between Fatah and Hamas, that took place in the Gaza Strip between June 10 and 15, 2007. It was a prominent event in the Fatah–Hamas conflict, centered ...

, Hamas took full control of the area. In 2007, Israel imposed a naval

blockade on the Gaza Strip, and cooperation with Egypt allowed a ground blockade of the Egyptian border

The tensions between Israel and Hamas escalated until late 2008, when Israel launched operation

Cast Lead

Cast may refer to:

Music

* Cast (band), an English alternative rock band

* Cast (Mexican band), a progressive Mexican rock band

* The Cast, a Scottish musical duo: Mairi Campbell and Dave Francis

* ''Cast'', a 2012 album by Trespassers William

...

upon Gaza, resulting in thousands of civilian casualties and billions of dollars in damage. By February 2009, a ceasefire was signed with international mediation between the parties, though the occupation and small and sporadic eruptions of violence continued.

In 2011, a Palestinian Authority attempt to gain UN membership as a fully sovereign state failed. In Hamas-controlled Gaza, sporadic rocket attacks on Israel and Israeli air raids still take place. In November 2012, the representation of Palestine in UN was upgraded to a non-member observer State, and its mission title was changed from "Palestine (represented by PLO)" to "

State of Palestine

Palestine ( ar, فلسطين, Filasṭīn), Legal status of the State of Palestine, officially the State of Palestine ( ar, دولة فلسطين, Dawlat Filasṭīn, label=none), is a state (polity), state located in Western Asia. Officiall ...

".

Peace process

Oslo Accords (1993)

In 1993, Israeli officials led by

Yitzhak Rabin

Yitzhak Rabin (; he, יִצְחָק רַבִּין, ; 1 March 1922 – 4 November 1995) was an Israeli politician, statesman and general. He was the fifth Prime Minister of Israel, serving two terms in office, 1974–77, and from 1992 until h ...

and Palestinian leaders from the

Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establ ...

led by

Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

strove to find a peaceful solution through what became known as the Oslo peace process. A crucial milestone in this process was Arafat's letter of recognition of Israel's right to exist. In 1993, the Oslo Accords were finalized as a framework for future Israeli–Palestinian relations. The crux of the Oslo agreement was that Israel would gradually cede control of the Palestinian territories over to the Palestinians in exchange for peace. The Oslo process was delicate and progressed in fits and starts, the process took a turning point at the

assassination of Yitzhak Rabin

The assassination of Yitzhak Rabin, the fifth prime minister of Israel, took place on 4 November 1995 (12 Marcheshvan 5756 on the Hebrew calendar) at 21:30, at the end of a rally in support of the Oslo Accords at the Kings of Israel Square in ...

and finally unraveled when Arafat and

Ehud Barak

Ehud Barak ( he-a, אֵהוּד בָּרָק, Ehud_barak.ogg, link=yes, born Ehud Brog; 12 February 1942) is an Israeli general and politician who served as the tenth prime minister from 1999 to 2001. He was leader of the Labor Party until Jan ...

failed to reach agreement at Camp David in July 2000.

Robert Malley

Robert Malley (born 1963) is an American lawyer, political scientist and specialist in conflict resolution, who was the lead negotiator on the 2015 Iran nuclear deal known as the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA). He is currently the U.S. ...

, special assistant to US President

Bill Clinton

William Jefferson Clinton ( né Blythe III; born August 19, 1946) is an American politician who served as the 42nd president of the United States from 1993 to 2001. He previously served as governor of Arkansas from 1979 to 1981 and agai ...

for Arab–Israeli Affairs, has confirmed that while Barak made no formal written offer to Arafat, the US did present concepts for peace which were considered by the Israeli side yet left unanswered by Arafat "the Palestinians' principal failing is that from the beginning of the Camp David summit onward they were unable either to say yes to the American ideas or to present a cogent and specific counterproposal of their own". Consequently, there are different accounts of the proposals considered.

Camp David Summit (2000)

In July 2000, US President Bill Clinton convened a peace summit between Palestinian President Yasser Arafat and Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak. Barak reportedly put forward the following as "bases for negotiation", via the US to the Palestinian President; a non-militarized Palestinian state split into 3–4 parts containing 87–92%

[Three factors made Israel's territorial offer less forthcoming than it initially appeared. First, the 91 percent land offer was based on the Israeli definition of the West Bank, but this differs by approximately 5 percentage points from the Palestinian definition. Palestinians use a total area of 5,854 square kilometers. Israel, however, omits the area known as No Man's Land (50 km2 near Latrun), post-1967 East Jerusalem (71 km2), and the territorial waters of the Dead Sea (195 km2), which reduces the total to 5,538 km2. Thus, an Israeli offer of 91 percent (of 5,538 km2 of the West Bank translates into only 86 percent from the Palestinian perspective. ]

Jeremy Pressman, ''International Security'', vol 28, no. 2, Fall 2003

''"Visions in Collision: What Happened at Camp David and Taba?"''

. O

. See pp. 16–17 of the West Bank including only parts of East Jerusalem, and the entire Gaza Strip,

[ Karsh, Efraim. ''Arafat's War: The Man and His Battle for Israeli Conquest''. New York: Grove Press, 2003. p. 168. "Arafat ''rejected'' the proposal" (emphasis added).] The offer also included that 69 Jewish settlements (which comprise 85% of the West Bank's Jewish settlers) would be ceded to Israel, no right of return to Israel, no sovereignty over the Temple Mount or any core East Jerusalem neighbourhoods, and continued Israel control over the Jordan Valley.

[Jeremy Pressman, ''International Security'', vol 28, no. 2, Fall 2003]

''"Visions in Collision: What Happened at Camp David and Taba?"''

. O

. See pp. 7, 15–19

Arafat rejected this offer.

According to the Palestinian negotiators the offer did not remove many of the elements of the Israeli occupation regarding land, security, settlements, and Jerusalem.

President Clinton reportedly requested that Arafat make a counter-offer, but he proposed none. Former Israeli Foreign Minister Shlomo Ben Ami who kept a diary of the negotiations said in an interview in 2001, when asked whether the Palestinians made a counterproposal: "No. And that is the heart of the matter. Never, in the negotiations between us and the Palestinians, was there a Palestinian counterproposal." In a separate interview in 2006 Ben Ami stated that were he a Palestinian he would have rejected the Camp David offer.

No tenable solution was crafted which would satisfy both Israeli and Palestinian demands, even under intense US pressure. Clinton has long blamed Arafat for the collapse of the summit. In the months following the summit, Clinton appointed former US Senator

George J. Mitchell

George John Mitchell Jr. (born August 20, 1933) is an American politician, diplomat, and lawyer. A leading member of the Democratic Party, he served as a United States senator from Maine from 1980 to 1995, and as Senate Majority Leader from 198 ...

to lead a fact-finding committee aiming to identify strategies for restoring the peace process. The

committee's findings were published in 2001 with the dismantlement of existing Israeli settlements and Palestinian crackdown on militant activity being one strategy.

Developments following Camp David

Following the failed summit Palestinian and Israeli negotiators continued to meet in small groups through August and September 2000 to try to bridge the gaps between their respective positions. The United States prepared its own plan to resolve the outstanding issues. Clinton's presentation of the US proposals was delayed by the advent of the

Second Intifada

The Second Intifada ( ar, الانتفاضة الثانية, ; he, האינתיפאדה השנייה, ), also known as the Al-Aqsa Intifada ( ar, انتفاضة الأقصى, label=none, '), was a major Palestinian uprising against Israel. ...

at the end of September.

[

Clinton's plan eventually presented on 23 December 2000, proposed the establishment of a sovereign Palestinian state in the Gaza strip and 94–96 percent of the West Bank plus the equivalent of 1–3 percent of the West Bank in land swaps from pre-1967 Israel. On Jerusalem, the plan stated that "the general principle is that Arab areas are Palestinian and that Jewish areas are Israeli." The holy sites were to be split on the basis that Palestinians would have sovereignty over the Temple Mount/Noble sanctuary, while the Israelis would have sovereignty over the Western Wall. On refugees the plan suggested a number of proposals including financial compensation, the right of return to the Palestinian state, and Israeli acknowledgment of suffering caused to the Palestinians in 1948. Security proposals referred to a "non-militarized" Palestinian state, and an international force for border security. Both sides accepted Clinton's plan][

]

Taba Summit (2001)

The Israeli negotiation team presented a new map at the Taba Summit

The Taba Summit (also known as ''Taba Talks'', ''Taba Conference'' or short ''Taba'') were talks between Israel and the Palestinian Authority, held from 21 to 27 January 2001 at Taba, in the Sinai. The talks took place during a political transi ...

in Taba, Egypt

Taba ( ar, طابا ', ) is an Egyptian town near the northern tip of the Gulf of Aqaba. Taba is the location of Egypt's busiest border crossing with neighboring Eilat, Israel. Taba was originally developed as a tourist destination by the Israelis ...

in January 2001. The proposition removed the "temporarily Israeli controlled" areas, and the Palestinian side accepted this as a basis for further negotiation. With Israeli elections looming the talks ended without an agreement but the two sides issued a joint statement attesting to the progress they had made: "The sides declare that they have never been closer to reaching an agreement and it is thus our shared belief that the remaining gaps could be bridged with the resumption of negotiations following the Israeli elections." The following month the Likud

Likud ( he, הַלִּיכּוּד, HaLikud, The Consolidation), officially known as Likud – National Liberal Movement, is a major centre-right to right-wing political party in Israel. It was founded in 1973 by Menachem Begin and Ariel Sharon ...

party candidate Ariel Sharon

Ariel Sharon (; ; ; also known by his diminutive Arik, , born Ariel Scheinermann, ; 26 February 1928 – 11 January 2014) was an Israeli general and politician who served as the 11th Prime Minister of Israel from March 2001 until April 2006.

S ...

defeated Ehud Barak in the Israeli elections and was elected as Israeli prime minister on 7 February 2001. Sharon's new government chose not to resume the high-level talks.[

]

Road Map for Peace

One peace proposal, presented by the Quartet

In music, a quartet or quartette (, , , , ) is an ensemble of four singers or instrumental performers; or a musical composition for four voices and instruments.

Classical String quartet

In classical music, one of the most common combinations o ...

of the European Union, Russia, the United Nations and the United States on 17 September 2002, was the Road Map for Peace. This plan did not attempt to resolve difficult questions such as the fate of Jerusalem or Israeli settlements, but left that to be negotiated in later phases of the process. The proposal never made it beyond the first phase, whose goals called for a halt to both Israeli settlement construction and Israeli–Palestinian violence. Neither goal has been achieved as of November 2015.

Arab Peace Initiative

The Arab Peace Initiative ( ar, مبادرة السلام العربية ''Mubādirat as-Salām al-ʿArabīyyah'') was first proposed by Crown Prince Abdullah of Saudi Arabia

Abdullah bin Abdulaziz Al Saud ( ar, عبدالله بن عبدالعزيز آل سعود ''ʿAbd Allāh ibn ʿAbd al ʿAzīz Āl Saʿūd'', Najdi Arabic pronunciation: ; 1 August 1924 – 23 January 2015) was King of Saudi Arabia, King and Pri ...

at the Beirut Summit

The Beirut Summit (also known as the Arab Summit Conference) was a meeting of the Arab League in Beirut, Lebanon in March 2002 to discuss the Israeli–Palestinian conflict. At the time Yassar Arafat, the leader of Palestine, was under house-arre ...

(2002). The peace initiative is a proposed solution to the Arab–Israeli conflict as a whole, and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict in particular.

The initiative was initially published on 28 March 2002, at the Beirut Summit, and agreed upon again in 2007 in the Riyadh Summit.

Unlike the Road Map for Peace, it spelled out "final-solution" borders based explicitly on the UN borders established before the 1967 Six-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

. It offered full normalization of relations with Israel, in exchange for the withdrawal of its forces from all the occupied territories, including the Golan Heights

The Golan Heights ( ar, هَضْبَةُ الْجَوْلَانِ, Haḍbatu l-Jawlān or ; he, רמת הגולן, ), or simply the Golan, is a region in the Levant spanning about . The region defined as the Golan Heights differs between di ...

, to recognize "an independent Palestinian state with East Jerusalem as its capital" in the West Bank and Gaza Strip, as well as a "just solution" for the Palestinian refugees.

A number of Israeli officials have responded to the initiative with both support and criticism. The Israeli government has expressed reservations on 'red line,' issues such as the Palestinian refugee problem, homeland security concerns, and the nature of Jerusalem.

Present status

The peace process has been predicated on a "two-state solution" thus far, but questions have been raised towards both sides' resolve to end the dispute. An article by S. Daniel Abraham, an American entrepreneur and founder of the Center for Middle East Peace in Washington, US, published on the website of the ''Atlantic'' magazine in March 2013, cited the following statistics: "Right now, the total number of Jews and Arabs living... in Israel, the West Bank, and Gaza is just under 12 million people. At the moment, a shade under 50 percent of the population is Jewish."

Since the April 2021 release of the Human Rights Watch

Human Rights Watch (HRW) is an international non-governmental organization, headquartered in New York City, that conducts research and advocacy on human rights. The group pressures governments, policy makers, companies, and individual human r ...

report ''A Threshold Crossed'', accusations have been mounting that the policies of Israel towards Palestinians living in Israel, the West Bank and Gaza now constitute the crime of apartheid

The crime of apartheid is defined by the 2002 Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court as inhumane acts of a character similar to other crimes against humanity "committed in the context of an institutionalized regime of systematic oppres ...

.Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and sup ...

on 1 February 2022.

Israel's settlement policy

Israel has had its settlement growth and policies in the Palestinian territories harshly criticized by the

Israel has had its settlement growth and policies in the Palestinian territories harshly criticized by the European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

citing it as increasingly undermining the viability of the two-state solution and running in contrary to the Israeli-stated commitment to resume negotiations.European Union

The European Union (EU) is a supranational political and economic union of member states that are located primarily in Europe. The union has a total area of and an estimated total population of about 447million. The EU has often been des ...

issued a statement which condemned continued Israeli settler violence and incitement.the Quartet

The Quartet on the Middle East or Middle East Quartet, sometimes called the Diplomatic Quartet or Madrid Quartet or simply the Quartet, is a foursome of nations and international and supranational entities involved in mediating the Israeli ...

"expressed its concern over ongoing settler violence and incitement in the West Bank," calling on Israel "to take effective measures, including bringing the perpetrators of such acts to justice."

Israeli Military Police

In a report published in February 2014 covering incidents over the three-year period of 2011–2013, Amnesty International

Amnesty International (also referred to as Amnesty or AI) is an international non-governmental organization focused on human rights, with its headquarters in the United Kingdom. The organization says it has more than ten million members and sup ...

asserted that Israeli forces employed reckless violence in the West Bank, and in some instances appeared to engage in wilful killings which would be tantamount to war crimes. Besides the numerous fatalities, Amnesty said at least 261 Palestinians, including 67 children, had been gravely injured by Israeli use of live ammunition. In this same period, 45 Palestinians, including 6 children had been killed. Amnesty's review of 25 civilians deaths concluded that in no case was there evidence of the Palestinians posing an imminent threat. At the same time, over 8,000 Palestinians suffered serious injuries from other means, including rubber-coated metal bullets. Only one IDF soldier was convicted, killing a Palestinian attempting to enter Israel illegally. The soldier was demoted and given a 1-year sentence with a five-month suspension. The IDF answered the charges stating that its army held itself "to the highest of professional standards," adding that when there was suspicion of wrongdoing, it investigated and took action "where appropriate".

Incitement

Following the Oslo Accords, which was to set up regulative bodies to rein in frictions, Palestinian incitement against Israel, Jews, and Zionism continued, parallel with Israel's pursuance of settlements in the Palestinian territories, though under Abu Mazen it has reportedly dwindled significantly.[Report on Palestinian Textbooks](_blank)

Georg Eckert Institute (2019-2021)

UN and the Palestinian state

The PLO have campaigned for full member status for the state of Palestine at the UN and for recognition on the 1967 borders. The campaign has received widespread support,Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international peace and security, recommending the admission of new UN members to the General Assembly, and ...

, in late 2012 the UN General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Curr ...

overwhelmingly approved the ''de facto'' recognition of sovereign Palestine by granting non-member state status.

Public support

Polling data has produced mixed results regarding the level of support among Palestinians for the two-state solution. A poll was carried out in 2011 by the Hebrew University; it indicated that support for a two-state solution was growing among both Israelis and Palestinians. The poll found that 58% of Israelis and 50% of Palestinians supported a two-state solution based on the Clinton Parameters

The Clinton Parameters ( he, מתווה קלינטון, ''Mitveh Clinton'') were guidelines for a permanent status agreement to resolve the Israeli–Palestinian conflict, proposed during the final weeks of the Presidential transition from Bill ...

, compared with 47% of Israelis and 39% of Palestinians in 2003, the first year the poll was carried out. The poll also found that an increasing percentage of both populations supported an end to violence—63% of Palestinians and 70% of Israelis expressing their support for an end to violence, an increase of 2% for Israelis and 5% for Palestinians from the previous year.

Issues in dispute

The following outlined positions are the official positions of the two parties; however, it is important to note that neither side holds a single position. Both the Israeli and the Palestinian sides include both moderate and extremist

Extremism is "the quality or state of being extreme" or "the advocacy of extreme measures or views". The term is primarily used in a political or religious sense to refer to an ideology that is considered (by the speaker or by some implied shar ...

bodies as well as dovish

Pacifism is the opposition or resistance to war, militarism (including conscription and mandatory military service) or violence. Pacifists generally reject theories of Just War. The word ''pacifism'' was coined by the French peace campaign ...

and hawkish

In politics, a war hawk, or simply hawk, is someone who favors war or continuing to escalate an existing conflict as opposed to other solutions. War hawks are the opposite of doves. The terms are derived by analogy with the birds of the same name ...

bodies.

One of the primary obstacles to resolving the Israeli–Palestinian conflict is a deep-set and growing distrust between its participants. Unilateral strategies and the rhetoric of hardline political factions, coupled with violence and incitements by civilians against one another, have fostered mutual embitterment and hostility and a loss of faith in the peace process. Support among Palestinians for Hamas

Hamas (, ; , ; an acronym of , "Islamic Resistance Movement") is a Palestinian Sunni-Islamic fundamentalist, militant, and nationalist organization. It has a social service wing, Dawah, and a military wing, the Izz ad-Din al-Qassam Bri ...

is considerable, and as its members consistently call for the destruction of Israel and violence

Violence is the use of physical force so as to injure, abuse, damage, or destroy. Other definitions are also used, such as the World Health Organization's definition of violence as "the intentional use of physical force or Power (social and p ...

remains a threat, security

Security is protection from, or resilience against, potential harm (or other unwanted coercive change) caused by others, by restraining the freedom of others to act. Beneficiaries (technically referents) of security may be of persons and social ...

becomes a prime concern for many Israelis. The expansion of Israeli settlement

Israeli settlements, or Israeli colonies, are civilian communities inhabited by Israeli citizens, overwhelmingly of Jewish ethnicity, built on lands occupied by Israel in the 1967 Six-Day War. The international community considers Israeli se ...

s in the West Bank has led the majority of Palestinians to believe that Israel is not committed to reaching an agreement, but rather to a pursuit of establishing permanent control over this territory in order to provide that security.

Jerusalem

The control of Jerusalem is a particularly delicate issue, with each side asserting claims over the city. The three largest

The control of Jerusalem is a particularly delicate issue, with each side asserting claims over the city. The three largest Abrahamic religions

The Abrahamic religions are a group of religions centered around worship of the God of Abraham. Abraham, a Hebrew patriarch, is extensively mentioned throughout Abrahamic religious scriptures such as the Bible and the Quran.

Jewish tradition ...

—Judaism, Christianity, and Islam—hold Jerusalem as an important setting for their religious and historical narratives. Jerusalem is the holiest city for Judaism, being the former location of the Jewish temples on the Temple Mount

The Temple Mount ( hbo, הַר הַבַּיִת, translit=Har haBayīt, label=Hebrew, lit=Mount of the House f the Holy}), also known as al-Ḥaram al-Sharīf (Arabic: الحرم الشريف, lit. 'The Noble Sanctuary'), al-Aqsa Mosque compoun ...

and the capital of the ancient Israelite kingdom. For Muslims, Jerusalem is the third holiest site, being the location of Isra and Mi'raj event, and the Al-Aqsa mosque

Al-Aqsa Mosque (, ), also known as Jami' Al-Aqsa () or as the Qibli Mosque ( ar, المصلى القبلي, translit=al-Muṣallā al-Qiblī, label=none), and also is a congregational mosque located in the Old City of Jerusalem. It is situate ...

. For Christians, Jerusalem is the site of Jesus' crucifixion and the Church of the Holy Sepulchre

The Church of the Holy Sepulchre, hy, Սուրբ Հարության տաճար, la, Ecclesia Sancti Sepulchri, am, የቅዱስ መቃብር ቤተክርስቲያን, he, כנסיית הקבר, ar, كنيسة القيامة is a church i ...

.

The Israeli government, including the Knesset

The Knesset ( he, הַכְּנֶסֶת ; "gathering" or "assembly") is the unicameral legislature of Israel. As the supreme state body, the Knesset is sovereign and thus has complete control of the entirety of the Israeli government (with ...

and Supreme Court

A supreme court is the highest court within the hierarchy of courts in most legal jurisdictions. Other descriptions for such courts include court of last resort, apex court, and high (or final) court of appeal. Broadly speaking, the decisions of ...

, is located in the "new city" of West Jerusalem and has been since Israel's founding in 1948. After Israel captured the Jordanian-controlled East Jerusalem in the Six-Day War, it assumed complete administrative control of East Jerusalem. In 1980, Israel passed the Jerusalem Law

The Jerusalem Law (, ar, قانون القدس) is a common name of Basic Law: Jerusalem, Capital of Israel passed by the Knesset on 30 July 1980 (17th Av, 5740).

Although the law did not use the term, the Israeli Supreme Court interpreted the ...

declaring "Jerusalem, complete and united, is the capital of Israel."

Many countries do not recognize Jerusalem as Israel's capital, with exceptions being the United States, and Russia. The majority of UN member states and most international organisations do not recognise Israel's claims to East Jerusalem which occurred after the 1967 Six-Day War, nor its 1980 Jerusalem Law proclamation. The International Court of Justice in its 2004 Advisory opinion on the "Legal Consequences of the Construction of a Wall in the Occupied Palestinian Territory" described East Jerusalem as "occupied Palestinian territory."

Holy sites

Israel has concerns regarding the welfare of Jewish holy places under possible Palestinian control. When Jerusalem was under Jordanian control, no Jews were allowed to visit the Western Wall

The Western Wall ( he, הַכּוֹתֶל הַמַּעֲרָבִי, HaKotel HaMa'aravi, the western wall, often shortened to the Kotel or Kosel), known in the West as the Wailing Wall, and in Islam as the Buraq Wall (Arabic: حَائِط � ...

or other Jewish holy places, and the Jewish cemetery on the Mount of Olives

The Mount of Olives or Mount Olivet ( he, הַר הַזֵּיתִים, Har ha-Zeitim; ar, جبل الزيتون, Jabal az-Zaytūn; both lit. 'Mount of Olives'; in Arabic also , , 'the Mountain') is a mountain ridge east of and adjacent to Jeru ...

was desecrated.Joseph's Tomb

Joseph's Tomb ( he, קבר יוסף, ''Qever Yosef''; ar, قبر يوسف, ''Qabr Yūsuf'') is a funerary monument located in Balata village at the eastern entrance to the valley that separates Mounts Gerizim and Ebal, 300 metres northwest of ...

, a shrine considered sacred by both Jews and Muslims. Settlers established a yeshiva, installed a Torah scroll and covered the mihrab

Mihrab ( ar, محراب, ', pl. ') is a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the ''qibla'', the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca towards which Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a ''mihrab'' appears is thus the "qibla w ...

. During the Second Intifada the site was looted and burned. Israeli security agencies routinely monitor and arrest Jewish extremists that plan attacks, though many serious incidents have still occurred. Israel has allowed almost complete autonomy to the Muslim trust (Waqf

A waqf ( ar, وَقْف; ), also known as hubous () or '' mortmain'' property is an inalienable charitable endowment under Islamic law. It typically involves donating a building, plot of land or other assets for Muslim religious or charitabl ...

) over the Temple Mount.Western Wall Tunnel

The Western Wall Tunnel ( he, מנהרת הכותל, translit.: ''Minharat Hakotel'') is a tunnel exposing the Western Wall from where the traditional, open-air prayer site ends and up to the Wall's northern end. Most of the tunnel is in continua ...

was re-opened with the intent of causing the mosque's collapse. The Israel Ministry of Foreign Affairs denied this claim in a 1996 speech to the United Nations and characterized the statement as "escalation of rhetoric."

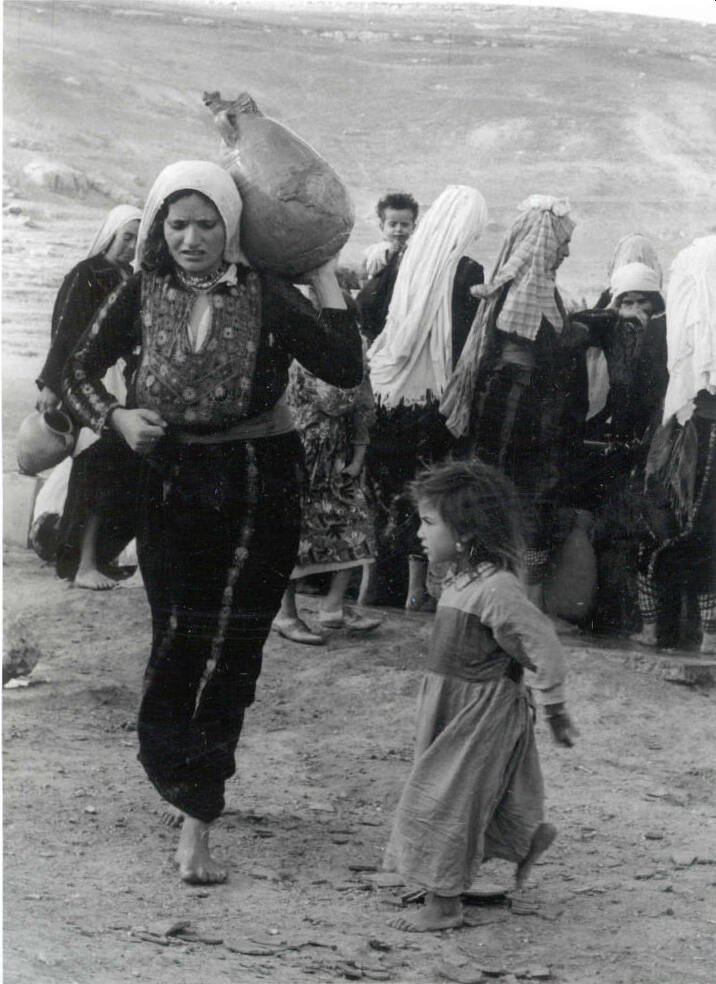

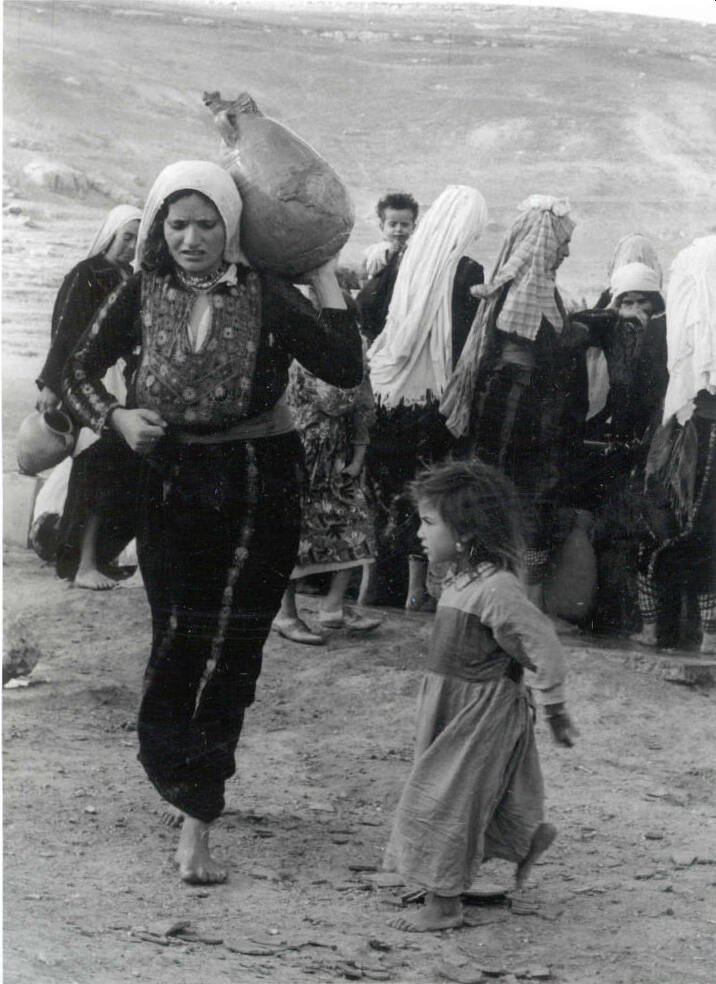

Palestinian refugees

Palestinian refugees are people who lost both their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab–Israeli conflict

Palestinian refugees are people who lost both their homes and means of livelihood as a result of the 1948 Arab–Israeli conflictSix-Day War

The Six-Day War (, ; ar, النكسة, , or ) or June War, also known as the 1967 Arab–Israeli War or Third Arab–Israeli War, was fought between Israel and a coalition of Arab world, Arab states (primarily United Arab Republic, Egypt, S ...

.[ A third of the refugees live in recognized refugee camps in ]Jordan

Jordan ( ar, الأردن; tr. ' ), officially the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan,; tr. ' is a country in Western Asia. It is situated at the crossroads of Asia, Africa, and Europe, within the Levant region, on the East Bank of the Jordan Rive ...

, Lebanon, Syria

Syria ( ar, سُورِيَا or سُورِيَة, translit=Sūriyā), officially the Syrian Arab Republic ( ar, الجمهورية العربية السورية, al-Jumhūrīyah al-ʻArabīyah as-Sūrīyah), is a Western Asian country loc ...

, the West Bank

The West Bank ( ar, الضفة الغربية, translit=aḍ-Ḍiffah al-Ġarbiyyah; he, הגדה המערבית, translit=HaGadah HaMaʽaravit, also referred to by some Israelis as ) is a landlocked territory near the coast of the Mediter ...

and the Gaza Strip

The Gaza Strip (;The New Oxford Dictionary of English (1998) – p.761 "Gaza Strip /'gɑːzə/ a strip of territory under the control of the Palestinian National Authority and Hamas, on the SE Mediterranean coast including the town of Gaza.. ...

. The remainder live in and around the cities and towns of these host countries.Yasser Arafat

Mohammed Abdel Rahman Abdel Raouf al-Qudwa al-Husseini (4 / 24 August 1929 – 11 November 2004), popularly known as Yasser Arafat ( , ; ar, محمد ياسر عبد الرحمن عبد الرؤوف عرفات القدوة الحسيني, Mu ...

,Universal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the Human rights, rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN Drafting of the Universal De ...

and UN General Assembly Resolution 194

United Nations General Assembly Resolution 194 is a resolution adopted near the end of the 1947–1949 Palestine war. The Resolution defines principles for reaching a final settlement and returning Palestine refugees to their homes. Article 11 o ...

as evidence. However, according to reports of private peace negotiations with Israel they have countenanced the return of only 10,000 refugees and their families to Israel as part of a peace settlement. Mahmoud Abbas

Mahmoud Abbas ( ar, مَحْمُود عَبَّاس, Maḥmūd ʿAbbās; born 15 November 1935), also known by the kunya Abu Mazen ( ar, أَبُو مَازِن, links=no, ), is the president of the State of Palestine and the Palestinian Natio ...

, the current Chairman of the Palestine Liberation Organization

The Palestine Liberation Organization (PLO; ar, منظمة التحرير الفلسطينية, ') is a Palestinian nationalism, Palestinian nationalist political and militant organization founded in 1964 with the initial purpose of establ ...

was reported to have said in private discussion that it is "illogical to ask Israel to take 5 million, or indeed 1 million. That would mean the end of Israel." In a further interview Abbas stated that he no longer had an automatic right to return to Safed in the northern Galilee where he was born in 1935. He later clarified that the remark was his personal opinion and not official policy.New Historians

The New Historians ( he, ההיסטוריונים החדשים, ''HaHistoryonim HaChadashim'') are a loosely defined group of Israeli historians who have challenged traditional versions of Israeli history, including Israel's role in the 1948 Pal ...

argue that the Palestinian refugees fled or were chased out or expelled by the actions of the Haganah

Haganah ( he, הַהֲגָנָה, lit. ''The Defence'') was the main Zionist paramilitary organization of the Jewish population ("Yishuv") in Mandatory Palestine between 1920 and its disestablishment in 1948, when it became the core of the ...

, Lehi

Lehi (; he, לח"י – לוחמי חרות ישראל ''Lohamei Herut Israel – Lehi'', "Fighters for the Freedom of Israel – Lehi"), often known pejoratively as the Stern Gang,"This group was known to its friends as LEHI and to its enemie ...

and Irgun

Irgun • Etzel

, image = Irgun.svg , image_size = 200px

, caption = Irgun emblem. The map shows both Mandatory Palestine and the Emirate of Transjordan, which the Irgun claimed in its entirety for a future Jewish state. The acronym "Etzel" i ...

, Zionist paramilitary groups. A number have also characterized this as an ethnic cleansing. The New Historians

The New Historians ( he, ההיסטוריונים החדשים, ''HaHistoryonim HaChadashim'') are a loosely defined group of Israeli historians who have challenged traditional versions of Israeli history, including Israel's role in the 1948 Pal ...

cite indications of Arab leaders' desire for the Palestinian Arab population to stay put.

* The Israeli

* The Israeli Law of Return

The Law of Return ( he, חֹוק הַשְׁבוּת, ''ḥok ha-shvūt'') is an Israeli law, passed on 5 July 1950, which gives Jews, people with one or more Jewish grandparent, and their spouses the right to relocate to Israel and acquire Isra ...

that grants citizenship to people of Jewish descent is viewed by critics as discriminatory against other ethnic groups, especially Palestinians that cannot apply for such citizenship under the law of return, to the territory which they were expelled from or fled during the course of the 1948 war.United Nations Security Council

The United Nations Security Council (UNSC) is one of the Organs of the United Nations, six principal organs of the United Nations (UN) and is charged with ensuring international security, international peace and security, recommending the admi ...

, Israel declared that it is not reasonable to contemplate a return of the refugees as the Arab League and the Arab High Committee have announced their intentions to continue their war of aggression

A war of aggression, sometimes also war of conquest, is a military conflict waged without the justification of self-defense, usually for territorial gain and subjugation.

Wars without international legality (i.e. not out of self-defense nor sanc ...

and resume hostilities, noting that the state of war has not been lifted and that no peace treaty has been signed. However, Israel accepted the next year the return of some of the refugees, notably through the annexation of the Gaza Strip or by absorbing 100.000 of them in exchange of a peace treaty. The Arab countries refused the proposal, demanding a complete return.

* The Israeli government asserts that the Arab refugee problem is largely caused by the refusal of all Arab governments except Jordan to grant citizenship to Palestinian Arabs who reside within those countries' borders. This has produced much of the poverty and economic problems of the refugees, according to MFA documents.UNRWA

The United Nations Relief and Works Agency for Palestine Refugees in the Near East (UNRWA) is a UN agency that supports the relief and human development of Palestinian refugees. UNRWA's mandate encompasses Palestinians displaced by the 1948 P ...

and not the UNHCR

The United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees (UNHCR) is a United Nations agency mandated to aid and protect refugees, forcibly displaced communities, and stateless people, and to assist in their voluntary repatriation, local integrati ...

. Most of the people recognizing themselves as Palestinian refugees would have otherwise been assimilated into their country of current residency, and would not maintain their refugee state if not for the separate entities.

* Concerning the origin of the Palestinian refugees, the Israeli government said that during the 1948 War the Arab Higher Committee

The Arab Higher Committee ( ar, اللجنة العربية العليا) or the Higher National Committee was the central political organ of the Arab Palestinians in Mandatory Palestine. It was established on 25 April 1936, on the initiative o ...

and the Arab states encouraged Palestinians to flee in order to make it easier to rout the Jewish state or that they did so to escape the fights by fear.Israeli army

The Israel Defense Forces (IDF; he, צְבָא הַהֲגָנָה לְיִשְׂרָאֵל , ), alternatively referred to by the Hebrew-language acronym (), is the national military of the State of Israel. It consists of three service branc ...

. Historians still debate the causes of the 1948 Palestinian exodus