Islamic cosmology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Islamic cosmology is the

In Islamic thought the cosmos includes both the Unseen Universe ( ar, عالم الغيب, ') and the Observable Universe ( ar, عالم الشهود, ''Alam-al-Shahood''). Nevertheless, both belong to the created universe. Islamic dualism does not constitute between spirit and matter, but between Creator (

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in dealing with his conception of physics and the physical world in his ''Matalib al-'Aliya'', criticizes the idea of the Earth's centrality within the universe and "explores the notion of the existence of a

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in dealing with his conception of physics and the physical world in his ''Matalib al-'Aliya'', criticizes the idea of the Earth's centrality within the universe and "explores the notion of the existence of a

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer

During this period, a distinctive Islamic system of astronomy flourished. It was Greek tradition to separate mathematical astronomy (as typified by

During this period, a distinctive Islamic system of astronomy flourished. It was Greek tradition to separate mathematical astronomy (as typified by

In the 11th–12th centuries, astronomers in

In the 11th–12th centuries, astronomers in

Other achievements of the Maragha school include the first empirical observational evidence for the Earth's rotation on its axis by al-Tusi and Qushji, the separation of

Other achievements of the Maragha school include the first empirical observational evidence for the Earth's rotation on its axis by al-Tusi and Qushji, the separation of

The Quran and Cosmology

*Dr Israr Ahme

{{Authority control Islam and science

cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosophe ...

of Islamic societies. It is mainly derived from the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

, Hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approval ...

, Sunnah

In Islam, , also spelled ( ar, سنة), are the traditions and practices of the Islamic prophet Muhammad that constitute a model for Muslims to follow. The sunnah is what all the Muslims of Muhammad's time evidently saw and followed and pass ...

, and current Islamic as well as other pre-Islamic sources. The Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

itself mentions seven heavens.Qur'an 2:29

Metaphysical principles

God

In monotheistic thought, God is usually viewed as the supreme being, creator, and principal object of faith. Swinburne, R.G. "God" in Honderich, Ted. (ed)''The Oxford Companion to Philosophy'', Oxford University Press, 1995. God is typically ...

) and creation. The latter including both the seen and unseen.

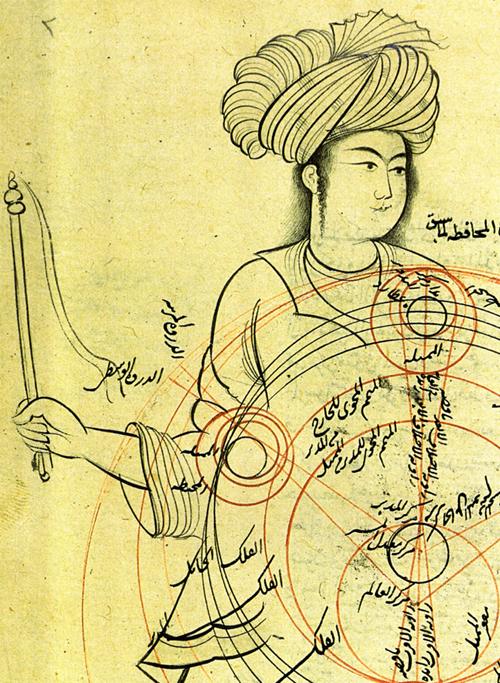

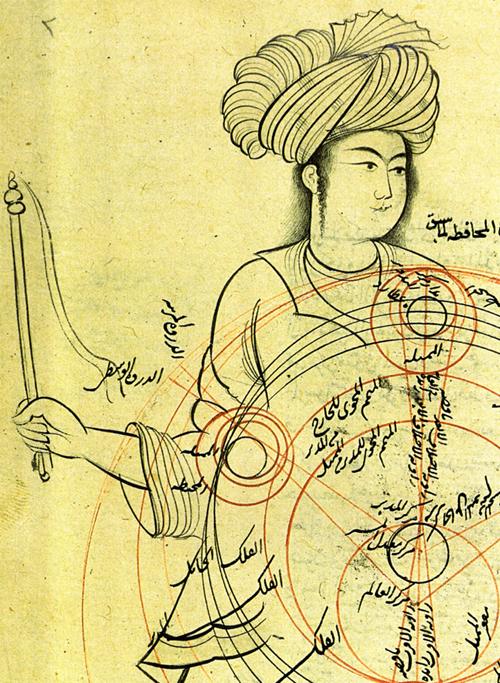

Sufi cosmology

Sufi cosmology ( ar, الكوزمولوجية الصوفية) is a general term forcosmological

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

doctrines associated with the mysticism of Sufism

Sufism ( ar, ''aṣ-ṣūfiyya''), also known as Tasawwuf ( ''at-taṣawwuf''), is a mystic body of religious practice, found mainly within Sunni Islam but also within Shia Islam, which is characterized by a focus on Islamic spirituality, ...

. These may differ from place to place, order to order and time to time, but overall show the influence of several different cosmographies:

*The Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

's testament concerning God and immaterial beings, the soul and the afterlife, the beginning and end of things, the seven heavens etc.

*The Neoplatonic

Neoplatonism is a strand of Platonic philosophy that emerged in the 3rd century AD against the background of Hellenistic philosophy and religion. The term does not encapsulate a set of ideas as much as a chain of thinkers. But there are some i ...

views cherished by Islamic philosophers

Muslim philosophers both profess Islam and engage in a style of philosophy situated within the structure of the Arabic language and Islam, though not necessarily concerned with religious issues. The sayings of the companions of Muhammad containe ...

like Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islam ...

and Ibn Arabi

Ibn ʿArabī ( ar, ابن عربي, ; full name: , ; 1165–1240), nicknamed al-Qushayrī (, ) and Sulṭān al-ʿĀrifīn (, , ' Sultan of the Knowers'), was an Arab Andalusian Muslim scholar, mystic, poet, and philosopher, extremely influen ...

.

*The Hermetic- Ptolemaic spherical geocentric world.

*The Ishraqi

Illuminationism ( Persian حكمت اشراق ''hekmat-e eshrāq'', Arabic: حكمة الإشراق ''ḥikmat al-ishrāq'', both meaning "Wisdom of the Rising Light"), also known as ''Ishrāqiyyun'' or simply ''Ishrāqi'' ( Persian اشراق, Ar ...

visionary universe as expounded by Suhrawardi Maqtul

"Shihāb ad-Dīn" Yahya ibn Habash Suhrawardī ( fa, شهابالدین سهروردی, also known as Sohrevardi) (1154–1191) was a PersianEdward Craig, Routledge Encyclopedia of Philosophy, "al-Suhrawardi, Shihab al-Din Yahya (1154-91)" Rou ...

.

Quranic interpretations

There are several verses in theQur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

(610–632) which some medieval and modern writers have reinterpreted as foreshadowing modern cosmological

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

theories. An early example of this can be seen in the work of the Islamic theologian Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in dealing with his conception of physics and the physical world in his ''Matalib''. He discusses Islamic cosmology, criticizes the idea of the Earth's centrality within the universe, and explores "the notion of the existence of a multiverse

The multiverse is a hypothetical group of multiple universes. Together, these universes comprise everything that exists: the entirety of space, time, matter, energy, information, and the physical laws and constants that describe them. The di ...

in the context of his commentary" on the Qur'anic verse, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds." He raises the question of whether the term "worlds" in this verse refers to "multiple world

In its most general sense, the term "world" refers to the totality of entities, to the whole of reality or to everything that is. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the worl ...

s within this single universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. A ...

or cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

, or to many other universes or a multiverse beyond this known universe." He rejects the Aristotelian view of a single world or universe in favour of the existence of multiple worlds and universes, a view that he believed to be supported by the Qur'an and by the Ash'ari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the 9 ...

theory of atomism

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms ...

.

Cosmology in the medieval Islamic world

Cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosophe ...

was studied extensively in the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. In ...

during what is known as the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

from the 7th to 15th centuries. There are exactly seven verses in the Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , sing.: ...

that specify that there are seven heavens, "He it is who created for you all that is in the earth; then he turned towards the heavens, and he perfected them as seven heavens; and he has perfect knowledge of all things."

One verse says that each heaven or sky has its own order, possibly meaning laws of nature. Another verse says after mentioning the seven heavens "and similar earths".

In 850, al-Farghani

Abū al-ʿAbbās Aḥmad ibn Muḥammad ibn Kathīr al-Farghānī ( ar, أبو العبّاس أحمد بن محمد بن كثير الفرغاني 798/800/805–870), also known as Alfraganus in the West, was an astronomer in the Abbasid court ...

wrote ''Kitab fi Jawani'' ("''A compendium of the science of stars''"). The book primarily gave a summary of Ptolemic cosmography

The term cosmography has two distinct meanings: traditionally it has been the protoscience of mapping the general features of the cosmos, heaven and Earth; more recently, it has been used to describe the ongoing effort to determine the large-sca ...

. However, it also corrected Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

's ''Almagest

The ''Almagest'' is a 2nd-century Greek-language mathematical and astronomical treatise on the apparent motions of the stars and planetary paths, written by Claudius Ptolemy ( ). One of the most influential scientific texts in history, it cano ...

'' based on findings of earlier Iranian

Iranian may refer to:

* Iran, a sovereign state

* Iranian peoples, the speakers of the Iranian languages. The term Iranic peoples is also used for this term to distinguish the pan ethnic term from Iranian, used for the people of Iran

* Iranian lan ...

astronomers. Al-Farghani gave revised values for the obliquity of the ecliptic

The ecliptic or ecliptic plane is the orbital plane of the Earth around the Sun. From the perspective of an observer on Earth, the Sun's movement around the celestial sphere over the course of a year traces out a path along the ecliptic agai ...

, the precession

Precession is a change in the orientation of the rotational axis of a rotating body. In an appropriate reference frame it can be defined as a change in the first Euler angle, whereas the third Euler angle defines the rotation itself. In o ...

al movement of the apogee

An apsis (; ) is the farthest or nearest point in the orbit of a planetary body about its primary body. For example, the apsides of the Earth are called the aphelion and perihelion.

General description

There are two apsides in any el ...

s of the sun and the moon, and the circumference of the earth. The books were widely circulated through the Muslim world, and even translated into Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

.

Cosmography

Islamic historian Michael Cook states that the "basic structure" of the Islamic universe according to scholars interpretation of the verses of the Quran and Islamictraditions

A tradition is a belief or behavior (folk custom) passed down within a group or society with symbolic meaning or special significance with origins in the past. A component of cultural expressions and folklore, common examples include holidays or ...

was of seven heavens above seven earths.

*"Allah is He Who Created seven firmaments and of the earth a similar number. Through the midst of them (all) descends His command: that ye may know that Allah has power over all things, and that Allah comprehends all things In (His) Knowledge."

The seven earths formed parallel layers with human beings inhabiting the top layer and Satan dwelling at the bottom. The seven heavens also formed parallel layers; the lowest level being the sky we see from earth and the highest being paradise (Jannah

In Islam, Jannah ( ar, جَنّة, janna, pl. ''jannāt'',lit. "paradise, garden", is the final abode of the righteous. According to one count, the word appears 147 times in the Quran. Belief in the afterlife is one of the six articles of ...

). Other traditions describes the seven heavens as each having a notable prophet in residence that Muhammad visits during Miʿrāj: Moses ( Musa) on the sixth heaven, Abraham ( Ibrahim) on the seventh heaven, etc.

''ʿAjā'ib al-makhlūqāt wa gharā'ib al-mawjūdāt'' ( ar, عجائب المخلوقات و غرائب الموجودات, meaning ''Marvels of creatures and Strange things existing'') is an important work of cosmography

The term cosmography has two distinct meanings: traditionally it has been the protoscience of mapping the general features of the cosmos, heaven and Earth; more recently, it has been used to describe the ongoing effort to determine the large-sca ...

by Zakariya ibn Muhammad ibn Mahmud Abu Yahya al-Qazwini who was born in Qazwin

Qazvin (; fa, قزوین, , also Romanized as ''Qazvīn'', ''Qazwin'', ''Kazvin'', ''Kasvin'', ''Caspin'', ''Casbin'', ''Casbeen'', or ''Ghazvin'') is the largest city and capital of the Province of Qazvin in Iran. Qazvin was a capital of the ...

year 600 ( AH (1203 AD).

Temporal finitism

In contrast to ancientGreek philosophers

Ancient Greek philosophy arose in the 6th century BC, marking the end of the Greek Dark Ages. Greek philosophy continued throughout the Hellenistic period and the period in which Greece and most Greek-inhabited lands were part of the Roman Empire ...

who believed that the universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. A ...

had an infinite past with no beginning, medieval philosophers and theologians

Theology is the systematic study of the nature of the divine and, more broadly, of religious belief. It is taught as an academic discipline, typically in universities and seminaries. It occupies itself with the unique content of analyzing the s ...

developed the concept of the universe having a finite past with a beginning (see Temporal finitism). The Christian philosopher

Christian philosophy includes all philosophy carried out by Christians, or in relation to the religion of Christianity.

Christian philosophy emerged with the aim of reconciling science and faith, starting from natural rational explanations wi ...

, John Philoponus

John Philoponus (Greek: ; ; c. 490 – c. 570), also known as John the Grammarian or John of Alexandria, was a Byzantine Greek philologist, Aristotelian commentator, Christian theologian and an author of a considerable number of philosophical tr ...

, presented the first such argument against the ancient Greek notion of an infinite past. His arguments were adopted by many most notably; early Muslim philosopher, Al-Kindi

Abū Yūsuf Yaʻqūb ibn ʼIsḥāq aṣ-Ṣabbāḥ al-Kindī (; ar, أبو يوسف يعقوب بن إسحاق الصبّاح الكندي; la, Alkindus; c. 801–873 AD) was an Arab Muslim philosopher, polymath, mathematician, physician ...

(Alkindus); the Jewish philosopher

Jewish philosophy () includes all philosophy carried out by Jews, or in relation to the religion of Judaism. Until modern ''Haskalah'' (Jewish Enlightenment) and Jewish emancipation, Jewish philosophy was preoccupied with attempts to reconcile ...

, Saadia Gaon

Saʻadiah ben Yosef Gaon ( ar, سعيد بن يوسف الفيومي ''Saʻīd bin Yūsuf al-Fayyūmi''; he, סַעֲדְיָה בֶּן יוֹסֵף אַלְפַיּוּמִי גָּאוֹן ''Saʿăḏyāh ben Yōsēf al-Fayyūmī Gāʾōn''; ...

(Saadia ben Joseph); and the Muslim theologian, Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polym ...

(Algazel). They used two logical arguments against an infinite past, the first being the "argument from the impossibility of the existence of an actual infinite", which states:

:"An actual infinite cannot exist."

:"An infinite temporal regress of events is an actual infinite."

:"∴ An infinite temporal regress of events cannot exist."

The second argument, the "argument from the impossibility of completing an actual infinite by successive addition", states:

:"An actual infinite cannot be completed by successive addition."

:"The temporal series of past events has been completed by successive addition."

:"∴ The temporal series of past events cannot be an actual infinite."

Both arguments were adopted by later Christian philosophers and theologians, and the second argument in particular became more famous after it was adopted by Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and aes ...

in his thesis of the first antinomy concerning time

Time is the continued sequence of existence and events that occurs in an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the present, into the future. It is a component quantity of various measurements used to sequence events, t ...

.

Amount of time

The Quran states that the universe was created in seven ayyam (days), in verse 50:38 among others. According to verse 70:3, one day in Quran is equal to 50,000 years on Earth. Therefore, Muslims interpret the description of a "seven days" creation as seven distinct periods or eons. The length of these periods is not precisely defined, nor are the specific developments that took place during each period. According to Michael Cook "early Muslim scholars" believed the amount of finite time creation had been assigned was about "six or seven thousand years" and that perhaps all but 500 years or so had already passed. He quotes a tradition of Muhammad saying "in reference to the prospective duration" of the community of the Muslim companions: `Your appointed time compared with that of those who were before you is as from the afternoon prayer (Asr prayer

The Asr prayer ( ar, صلاة العصر ', "afternoon prayer") is one of the five mandatory salah (Islamic prayer). As an Islamic day starts at sunset, the Asr prayer is technically the fifth prayer of the day. If counted from midnight, it i ...

) to the setting of the sun'". Early Muslim Ibn Ishaq

Muḥammad ibn Isḥāq ibn Yasār ibn Khiyār (; according to some sources, ibn Khabbār, or Kūmān, or Kūtān, ar, محمد بن إسحاق بن يسار بن خيار, or simply ibn Isḥaq, , meaning "the son of Isaac"; died 767) was an 8 ...

estimated the prophet Noah

Noah ''Nukh''; am, ኖህ, ''Noḥ''; ar, نُوح '; grc, Νῶε ''Nôe'' () is the tenth and last of the pre-Flood patriarchs in the traditions of Abrahamic religions. His story appears in the Hebrew Bible (Book of Genesis, chapters 5� ...

lived 1200 years after Adam

Adam; el, Ἀδάμ, Adám; la, Adam is the name given in Genesis 1-5 to the first human. Beyond its use as the name of the first man, ''adam'' is also used in the Bible as a pronoun, individually as "a human" and in a collective sense as " ...

was expelled from paradise, the prophet Abraham

Abraham, ; ar, , , name=, group= (originally Abram) is the common Hebrews, Hebrew patriarch of the Abrahamic religions, including Judaism, Christianity, and Islam. In Judaism, he is the founding father of the Covenant (biblical), special ...

2342 years after Adam, Moses 2907 years, Jesus

Jesus, likely from he, יֵשׁוּעַ, translit=Yēšūaʿ, label=Hebrew/Aramaic ( AD 30 or 33), also referred to as Jesus Christ or Jesus of Nazareth (among other names and titles), was a first-century Jewish preacher and religiou ...

4832 years and Muhammad

Muhammad ( ar, مُحَمَّد; 570 – 8 June 632 CE) was an Arab religious, social, and political leader and the founder of Islam. According to Islamic doctrine, he was a prophet divinely inspired to preach and confirm the monot ...

5432 years.

The Fatimid

The Fatimid Caliphate was an Ismaili Shi'a

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest Islamic schools and branches, branch of Islam. It holds that the Prophets and messengers in Islam, Islamic prophet Muhammad in Islam, Muh ...

thinker al-Mu’ayyad fi’l-Din al-Shirazi (d. 1078) shares his own views about the creation of the world in 6 days. He rebukes the idea of the creation of the world in 6 cycles of either 24 hours, 1000 or 50,000 years, and instead questions both how creation can be measured in units of time when time was yet to be created, as well as how an infinitely powerful creator can be limited by the constraints of time, as it is itself part of his own creation. The Ismaili

Isma'ilism ( ar, الإسماعيلية, al-ʾIsmāʿīlīyah) is a branch or sub-sect of Shia Islam. The Isma'ili () get their name from their acceptance of Imam Isma'il ibn Jafar as the appointed spiritual successor (imām) to Ja'far al-Sa ...

thinker Nasir Khusraw

Abu Mo’in Hamid ad-Din Nasir ibn Khusraw al-Qubadiani or Nāsir Khusraw Qubādiyānī Balkhi ( fa, ناصر خسرو قبادیانی, Nasir Khusraw Qubadiani) also spelled as ''Nasir Khusrow'' and ''Naser Khosrow'' (1004 – after 1070 CE) w ...

(d. after 1070) expands on his colleague’s work. He writes that these days refer to cycles of creation demarcated by the arrival of God’s messengers (''ṣāḥibān-i adwār''), culminating in the arrival of the Lord of the Resurrection (''Qāʾim al-Qiyāma''), when the world will come out of darkness and ignorance and “into the light of her Lord” (Quran 39:69). His era, unlike that of the enunciators of divine revelation (''nāṭiqs'') before him, is not one where God prescribes the people to work. Rather, his is an era of reward for those “who laboured in fulfilment of (the Prophets') command and with knowledge”.

Galaxy observation

The Arab astronomer Alhazen (965–1037) made the first attempt at observing and measuring theMilky Way

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes our Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked ey ...

's parallax

Parallax is a displacement or difference in the apparent position of an object viewed along two different lines of sight and is measured by the angle or semi-angle of inclination between those two lines. Due to foreshortening, nearby object ...

, and he thus "determined that because the Milky Way had no parallax, it was very remote from the earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

and did not belong to the atmosphere." The Persian astronomer Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

(973–1048) proposed the Milky Way galaxy

A galaxy is a system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar gas, dust, dark matter, bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Greek ' (), literally 'milky', a reference to the Milky Way galaxy that contains the Solar Sys ...

to be "a collection of countless fragments of the nature of nebulous stars." The Andalusian astronomer Ibn Bajjah

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

("Avempace", d. 1138) proposed that the Milky Way was made up of many stars which almost touched one another and appeared to be a continuous image due to the effect of refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomen ...

from sublunary material, citing his observation of the conjunction

Conjunction may refer to:

* Conjunction (grammar), a part of speech

* Logical conjunction, a mathematical operator

** Conjunction introduction, a rule of inference of propositional logic

* Conjunction (astronomy), in which two astronomical bodies ...

of Jupiter and Mars on 500 AH (1106/1107 AD) as evidence. Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ibn Ayyūb al-Zurʿī l-Dimashqī l-Ḥanbalī (29 January 1292–15 September 1350 CE / 691 AH–751 AH), commonly known as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya ("The son of the principal of he school ...

(1292–1350) proposed the Milky Way galaxy to be "a myriad of tiny stars packed together in the sphere of the fixed stars".

In the 10th century, the Persian astronomer Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi

ʿAbd al-Rahman al-Sufi ( fa, عبدالرحمن صوفی; December 7, 903 – May 25, 986) was an iranianRobert Harry van Gent. Biography of al-Sūfī'. "The Persian astronomer Abū al-Husayn ‘Abd al-Rahmān ibn ‘Umar al-Sūfī was born i ...

(known in the West as ''Azophi'') made the earliest recorded observation of the Andromeda Galaxy

The Andromeda Galaxy (IPA: ), also known as Messier 31, M31, or NGC 224 and originally the Andromeda Nebula, is a barred spiral galaxy with the diameter of about approximately from Earth and the nearest large galaxy to the Milky Way. The gal ...

, describing it as a "small cloud". Al-Sufi also identified the Large Magellanic Cloud

The Large Magellanic Cloud (LMC), or Nubecula Major, is a satellite galaxy of the Milky Way. At a distance of around 50 kiloparsecs (≈160,000 light-years), the LMC is the second- or third-closest galaxy to the Milky Way, after the ...

, which is visible from Yemen

Yemen (; ar, ٱلْيَمَن, al-Yaman), officially the Republic of Yemen,, ) is a country in Western Asia. It is situated on the southern end of the Arabian Peninsula, and borders Saudi Arabia to the north and Oman to the northeast an ...

, though not from Isfahan; it was not seen by Europeans until Magellan's voyage in the 16th century. These were the first galaxies other than the Milky Way to be observed from Earth. Al-Sufi published his findings in his ''Book of Fixed Stars

The ''Book of Fixed Stars'' ( ar, كتاب صور الكواكب ', literally ''The Book of the Shapes of Stars'') is an astronomical text written by Abd al-Rahman al-Sufi (Azophi) around 964. Following the translation movement in the 9th centu ...

'' in 964.

Possible worlds

Al-Ghazali

Al-Ghazali ( – 19 December 1111; ), full name (), and known in Persian-speaking countries as Imam Muhammad-i Ghazali (Persian: امام محمد غزالی) or in Medieval Europe by the Latinized as Algazelus or Algazel, was a Persian polym ...

, in ''The Incoherence of the Philosophers

''The Incoherence of the Philosophers'' (تهافت الفلاسفة ''Tahāfut al-Falāsifaʰ'' in Arabic) is the title of a landmark 11th-century work by the Persian theologian Abū Ḥāmid Muḥammad ibn Muḥammad al-Ghazali and a student o ...

'', defends the Ash'ari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the 9 ...

doctrine of a created universe that is temporally finite, against the Aristotelian doctrine of an eternal universe. In doing so, he proposed the modal theory of possible world

A possible world is a complete and consistent way the world is or could have been. Possible worlds are widely used as a formal device in logic, philosophy, and linguistics in order to provide a semantics for intensional and modal logic. Their ...

s, arguing that their actual world is the best of all possible worlds

The phrase "the best of all possible worlds" (french: Le meilleur des mondes possibles; german: Die beste aller möglichen Welten) was coined by the German polymath and Enlightenment philosopher Gottfried Leibniz in his 1710 work ''Essais de ...

from among all the alternate timeline

Alternate history (also alternative history, althist, AH) is a genre of speculative fiction of stories in which one or more historical events occur and are resolved differently than in real life. As conjecture based upon historical fact, alter ...

s and world histories that God could have possibly created. His theory parallels that of Duns Scotus

John Duns Scotus ( – 8 November 1308), commonly called Duns Scotus ( ; ; "Duns the Scot"), was a Scottish Catholic priest and Franciscan friar, university professor, philosopher, and theologian. He is one of the four most important ...

in the 14th century. While it is uncertain whether Al-Ghazali had any influence on Scotus, they both may have derived their theory from their readings of Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islam ...

's ''Metaphysics''.

Multiversal cosmology

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in dealing with his conception of physics and the physical world in his ''Matalib al-'Aliya'', criticizes the idea of the Earth's centrality within the universe and "explores the notion of the existence of a

Fakhr al-Din al-Razi (1149–1209), in dealing with his conception of physics and the physical world in his ''Matalib al-'Aliya'', criticizes the idea of the Earth's centrality within the universe and "explores the notion of the existence of a multiverse

The multiverse is a hypothetical group of multiple universes. Together, these universes comprise everything that exists: the entirety of space, time, matter, energy, information, and the physical laws and constants that describe them. The di ...

in the context of his commentary" on the Qur'an

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , si ...

ic verse, "All praise belongs to God, Lord of the Worlds." He raises the question of whether the term "world

In its most general sense, the term "world" refers to the totality of entities, to the whole of reality or to everything that is. The nature of the world has been conceptualized differently in different fields. Some conceptions see the worl ...

s" in this verse refers to "multiple worlds within this single universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. A ...

or cosmos

The cosmos (, ) is another name for the Universe. Using the word ''cosmos'' implies viewing the universe as a complex and orderly system or entity.

The cosmos, and understandings of the reasons for its existence and significance, are studied in ...

, or to many other universes or a multiverse beyond this known universe." In volume 4 of the ''Matalib'', Al-Razi states:

Al-Razi rejected the Aristotelian and Avicennian notions of a single universe revolving around a single world. He describes the main arguments against the existence of multiple worlds or universes, pointing out their weaknesses and refuting them. This rejection arose from his affirmation of atomism

Atomism (from Greek , ''atomon'', i.e. "uncuttable, indivisible") is a natural philosophy proposing that the physical universe is composed of fundamental indivisible components known as atoms.

References to the concept of atomism and its atoms ...

, as advocated by the Ash'ari

Ashʿarī theology or Ashʿarism (; ar, الأشعرية: ) is one of the main Sunnī schools of Islamic theology, founded by the Muslim scholar, Shāfiʿī jurist, reformer, and scholastic theologian Abū al-Ḥasan al-Ashʿarī in the 9 ...

school of Islamic theology

Schools of Islamic theology are various Islamic schools and branches in different schools of thought regarding '' ʿaqīdah'' (creed). The main schools of Islamic Theology include the Qadariyah, Falasifa, Jahmiyya, Murji'ah, Muʿtazila, Bat ...

, which entails the existence of vacant space in which the atoms move, combine and separate. He discussed in greater detail the void, the empty space between stars and constellations in the Universe

The universe is all of space and time and their contents, including planets, stars, galaxies, and all other forms of matter and energy. The Big Bang theory is the prevailing cosmological description of the development of the universe. A ...

, in volume 5 of the ''Matalib''. He argued that there exists an infinite outer space

Outer space, commonly shortened to space, is the expanse that exists beyond Earth and its atmosphere and between celestial bodies. Outer space is not completely empty—it is a near-perfect vacuum containing a low density of particles, pred ...

beyond the known world, and that God has the power to fill the vacuum

A vacuum is a space devoid of matter. The word is derived from the Latin adjective ''vacuus'' for "vacant" or " void". An approximation to such vacuum is a region with a gaseous pressure much less than atmospheric pressure. Physicists often di ...

with an infinite number of universes.

Refutations of astrology

The study of astrology was refuted by several Muslim writers at the time, includingal-Farabi

Abu Nasr Muhammad Al-Farabi ( fa, ابونصر محمد فارابی), ( ar, أبو نصر محمد الفارابي), known in the West as Alpharabius; (c. 872 – between 14 December, 950 and 12 January, 951)PDF version was a renowned early Is ...

, Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

, Avicenna

Ibn Sina ( fa, ابن سینا; 980 – June 1037 CE), commonly known in the West as Avicenna (), was a Persian polymath who is regarded as one of the most significant physicians, astronomers, philosophers, and writers of the Islam ...

, Biruni and Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psych ...

. Their reasons for refuting astrology were often due to both scientific (the methods used by astrologers being conjectural

In mathematics, a conjecture is a conclusion or a proposition that is proffered on a tentative basis without proof. Some conjectures, such as the Riemann hypothesis (still a conjecture) or Fermat's Last Theorem (a conjecture until proven in 19 ...

rather than empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

) and religious (conflicts with orthodox Islamic scholars

In Islam, the ''ulama'' (; ar, علماء ', singular ', "scholar", literally "the learned ones", also spelled ''ulema''; feminine: ''alimah'' ingularand ''aalimath'' lural are the guardians, transmitters, and interpreters of religious ...

) reasons.

Ibn Qayyim Al-Jawziyya

Shams al-Dīn Abū ʿAbd Allāh Muḥammad ibn Abī Bakr ibn Ayyūb al-Zurʿī l-Dimashqī l-Ḥanbalī (29 January 1292–15 September 1350 CE / 691 AH–751 AH), commonly known as Ibn Qayyim al-Jawziyya ("The son of the principal of he school ...

(1292–1350), in his ''Miftah Dar al-SaCadah'', used empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

arguments in astronomy in order to refute the practice of astrology and divination. He recognized that the star

A star is an astronomical object comprising a luminous spheroid of plasma held together by its gravity. The nearest star to Earth is the Sun. Many other stars are visible to the naked eye at night, but their immense distances from Earth make ...

s are much larger than the planet

A planet is a large, rounded astronomical body that is neither a star nor its remnant. The best available theory of planet formation is the nebular hypothesis, which posits that an interstellar cloud collapses out of a nebula to create a ...

s, and thus argued:

Al-Jawziyya also recognized the Milky Way

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes our Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked ey ...

galaxy

A galaxy is a system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar gas, dust, dark matter, bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Greek ' (), literally 'milky', a reference to the Milky Way galaxy that contains the Solar Sys ...

as "a myriad of tiny stars packed together in the sphere of the fixed stars" and thus argued that "it is certainly impossible to have knowledge of their influences."

Early heliocentric models

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer

The Hellenistic Greek astronomer Seleucus of Seleucia

Seleucus of Seleucia ( el, Σέλευκος ''Seleukos''; born c. 190 BC; fl. c. 150 BC) was a Hellenistic astronomer and philosopher. Coming from Seleucia on the Tigris, Mesopotamia, the capital of the Seleucid Empire, or, alternatively, Seleuk ...

, who advocated a heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

model in the 2nd century BC, wrote a work that was later translated into Arabic. A fragment of his work has survived only in Arabic translation, which was later referred to by the Persian philosopher Muhammad ibn Zakariya al-Razi

Abū Bakr al-Rāzī (full name: ar, أبو بکر محمد بن زکریاء الرازي, translit=Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Zakariyyāʾ al-Rāzī, label=none), () rather than ar, زکریاء, label=none (), as for example in , or in . In m ...

(865–925).

In the late ninth century, Ja'far ibn Muhammad Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi

Abu Ma'shar al-Balkhi, Latinized as Albumasar (also ''Albusar'', ''Albuxar''; full name ''Abū Maʿshar Jaʿfar ibn Muḥammad ibn ʿUmar al-Balkhī'' ;

, AH 171–272), was an early Persian Muslim astrologer, thought to be the greatest as ...

(Albumasar) developed a planetary model which some have interpreted as a heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

. This is due to his orbit

In celestial mechanics, an orbit is the curved trajectory of an object such as the trajectory of a planet around a star, or of a natural satellite around a planet, or of an artificial satellite around an object or position in space such a ...

al revolutions of the planets being given as heliocentric revolutions rather than geocentric

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

revolutions, and the only known planetary theory in which this occurs is in the heliocentric theory. His work on planetary theory has not survived, but his astronomical data was later recorded by al-Hashimi Al-Hashimi, also transliterated Al-Hashemi ( ar, الهاشمي), Hashemi, Hashimi or Hashmi ( fa, هاشمی) is an Arabic, Arabian, and Persian surname.Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

and al-Sijzi

Abu Sa'id Ahmed ibn Mohammed ibn Abd al-Jalil al-Sijzi (c. 945 - c. 1020, also known as al-Sinjari and al-Sijazi; fa, ابوسعید سجزی; Al-Sijzi is short for " Al-Sijistani") was an Iranian Muslim astronomer, mathematician, and astrol ...

.

In the early eleventh century, al-Biruni

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of ...

had met several Indian scholars who believed in a rotating earth. In his ''Indica'', he discusses the theories on the Earth's rotation supported by Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the '' Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established doctrine of Brahma", dated 628), a theoretical tr ...

and other Indian astronomers

Indian or Indians may refer to:

Peoples South Asia

* Indian people, people of Indian nationality, or people who have an Indian ancestor

** Non-resident Indian, a citizen of India who has temporarily emigrated to another country

* South Asia ...

, while in his ''Canon Masudicus'', al-Biruni writes that Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the '' Aryabhatiya'' (whi ...

's followers assigned the first movement from east to west to the Earth and a second movement from west to east to the fixed stars. Al-Biruni also wrote that al-Sijzi

Abu Sa'id Ahmed ibn Mohammed ibn Abd al-Jalil al-Sijzi (c. 945 - c. 1020, also known as al-Sinjari and al-Sijazi; fa, ابوسعید سجزی; Al-Sijzi is short for " Al-Sijistani") was an Iranian Muslim astronomer, mathematician, and astrol ...

also believed the Earth was moving and invented an astrolabe

An astrolabe ( grc, ἀστρολάβος ; ar, ٱلأَسْطُرلاب ; persian, ستارهیاب ) is an ancient astronomical instrument that was a handheld model of the universe. Its various functions also make it an elaborate incli ...

called the "Zuraqi" based on this idea:

In his ''Indica'', al-Biruni briefly refers to his work on the refutation of heliocentrism, the ''Key of Astronomy'', which is now lost:

Early ''Hay'a'' program

During this period, a distinctive Islamic system of astronomy flourished. It was Greek tradition to separate mathematical astronomy (as typified by

During this period, a distinctive Islamic system of astronomy flourished. It was Greek tradition to separate mathematical astronomy (as typified by Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

) from philosophical cosmology (as typified by Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

). Muslim scholars developed a program of seeking a physically real configuration (''hay'a'') of the universe, that would be consistent with both mathematical

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

and physical

Physical may refer to:

*Physical examination

In a physical examination, medical examination, or clinical examination, a medical practitioner examines a patient for any possible medical signs or symptoms of a medical condition. It generally cons ...

principles. Within the context of this ''hay'a'' tradition, Muslim astronomers began questioning technical details of the Ptolemaic system

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

of astronomy.

Some Muslim astronomers, however, most notably Abū Rayhān al-Bīrūnī

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

and Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

, discussed whether the Earth moved and considered how this might be consistent with astronomical computations and physical systems. Several other Muslim astronomers, most notably those following the Maragha school of astronomy, developed non-Ptolemaic planetary models within a geocentric context that were later adapted by the Copernican model in a heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

context.

Between 1025 and 1028, Ibn al-Haytham

Ḥasan Ibn al-Haytham, Latinized as Alhazen (; full name ; ), was a medieval mathematician, astronomer, and physicist of the Islamic Golden Age from present-day Iraq.For the description of his main fields, see e.g. ("He is one of the prin ...

(Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through the power ...

ized as Alhazen), began the ''hay'a'' tradition of Islamic astronomy with his ''Al-Shuku ala Batlamyus'' (''Doubts on Ptolemy''). While maintaining the physical reality of the geocentric model, he was the first to criticize Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

's astronomical system, which he criticized on empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

, observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. Th ...

al and experiment

An experiment is a procedure carried out to support or refute a hypothesis, or determine the efficacy or likelihood of something previously untried. Experiments provide insight into cause-and-effect by demonstrating what outcome occurs wh ...

al grounds, and for relating actual physical motions to imaginary mathematical points, lines and circles. Ibn al-Haytham developed a physical structure of the Ptolemaic system in his ''Treatise on the configuration of the World'', or ''Maqâlah fî ''hay'at'' al-‛âlam'', which became an influential work in the ''hay'a'' tradition. In his ''Epitome of Astronomy'', he insisted that the heavenly bodies "were accountable to the laws of physics

Scientific laws or laws of science are statements, based on repeated experiments or observations, that describe or predict a range of natural phenomena. The term ''law'' has diverse usage in many cases (approximate, accurate, broad, or narrow) a ...

."

In 1038, Ibn al-Haytham described the first non-Ptolemaic configuration in ''The Model of the Motions''. His reform was not concerned with cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosophe ...

, as he developed a systematic study of celestial kinematics that was completely geometric

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is ca ...

. This in turn led to innovative developments in infinitesimal geometry

Geometry (; ) is, with arithmetic, one of the oldest branches of mathematics. It is concerned with properties of space such as the distance, shape, size, and relative position of figures. A mathematician who works in the field of geometry is c ...

. His reformed model was the first to reject the equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plan ...

and eccentrics

Eccentricity (also called quirkiness) is an unusual or odd behavior on the part of an individual. This behavior would typically be perceived as unusual or unnecessary, without being demonstrably maladaptive. Eccentricity is contrasted with norm ...

, separate natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

from astronomy, free celestial kinematics from cosmology, and reduce physical entities to geometrical entities. The model also propounded the Earth's rotation about its axis, and the centres of motion were geometrical points without any physical significance, like Johannes Kepler's model centuries later. Ibn al-Haytham also describes an early version of Occam's razor

Occam's razor, Ockham's razor, or Ocham's razor ( la, novacula Occami), also known as the principle of parsimony or the law of parsimony ( la, lex parsimoniae), is the problem-solving principle that "entities should not be multiplied beyond neces ...

, where he employs only minimal hypotheses regarding the properties that characterize astronomical motions, as he attempts to eliminate from his planetary model the cosmological

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosopher ...

hypotheses that cannot be observed from Earth

Earth is the third planet from the Sun and the only astronomical object known to harbor life. While large volumes of water can be found throughout the Solar System, only Earth sustains liquid surface water. About 71% of Earth's surf ...

.

In 1030, Abū al-Rayhān al-Bīrūnī

Abu Rayhan Muhammad ibn Ahmad al-Biruni (973 – after 1050) commonly known as al-Biruni, was a Khwarazmian Iranian in scholar and polymath during the Islamic Golden Age. He has been called variously the "founder of Indology", "Father of Co ...

discussed the Indian planetary theories of Aryabhata

Aryabhata ( ISO: ) or Aryabhata I (476–550 CE) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer of the classical age of Indian mathematics and Indian astronomy. He flourished in the Gupta Era and produced works such as the '' Aryabhatiya'' (whi ...

, Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the '' Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established doctrine of Brahma", dated 628), a theoretical tr ...

and Varahamihira in his ''Ta'rikh al-Hind'' (Latinized as ''Indica''). Biruni stated that Brahmagupta

Brahmagupta ( – ) was an Indian mathematician and astronomer. He is the author of two early works on mathematics and astronomy: the '' Brāhmasphuṭasiddhānta'' (BSS, "correctly established doctrine of Brahma", dated 628), a theoretical tr ...

and others consider that the earth rotates on its axis and Biruni noted that this does not create any mathematical problems. Abu Said al-Sijzi

Abu Sa'id Ahmed ibn Mohammed ibn Abd al-Jalil al-Sijzi (c. 945 - c. 1020, also known as al-Sinjari and al-Sijazi; fa, ابوسعید سجزی; Al-Sijzi is short for " Al-Sijistani") was an Iranian Muslim astronomer, mathematician, and astrol ...

, a contemporary of al-Biruni, suggested the possible heliocentric movement of the Earth around the Sun, which al-Biruni did not reject. Al-Biruni agreed with the Earth's rotation about its own axis, and while he was initially neutral regarding the heliocentric

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

and geocentric models, he considered heliocentrism to be a philosophical problem. He remarked that if the Earth rotates on its axis and moves around the Sun, it would remain consistent with his astronomical parameters:

Andalusian Revolt

In the 11th–12th centuries, astronomers in

In the 11th–12th centuries, astronomers in al-Andalus

Al-Andalus translit. ; an, al-Andalus; ast, al-Ándalus; eu, al-Andalus; ber, ⴰⵏⴷⴰⵍⵓⵙ, label= Berber, translit=Andalus; ca, al-Àndalus; gl, al-Andalus; oc, Al Andalús; pt, al-Ândalus; es, al-Ándalus () was the Mus ...

took up the challenge earlier posed by Ibn al-Haytham, namely to develop an alternate non-Ptolemaic configuration that evaded the errors found in the Ptolemaic model. Like Ibn al-Haytham's critique, the anonymous Andalusian work, ''al-Istidrak ala Batlamyus'' (''Recapitulation regarding Ptolemy''), included a list of objections to Ptolemic astronomy. This marked the beginning of the Andalusian school's revolt

Rebellion, uprising, or insurrection is a refusal of obedience or order. It refers to the open resistance against the orders of an established authority.

A rebellion originates from a sentiment of indignation and disapproval of a situation and ...

against Ptolemaic astronomy, otherwise known as the "Andalusian Revolt".

In the 12th century, Averroes

Ibn Rushd ( ar, ; full name in ; 14 April 112611 December 1198), often Latinized as Averroes ( ), was an

Andalusian polymath and jurist who wrote about many subjects, including philosophy, theology, medicine, astronomy, physics, psych ...

rejected the eccentric deferents introduced by Ptolemy

Claudius Ptolemy (; grc-gre, Πτολεμαῖος, ; la, Claudius Ptolemaeus; AD) was a mathematician, astronomer, astrologer, geographer, and music theorist, who wrote about a dozen scientific treatises, three of which were of import ...

. He rejected the Ptolemaic model and instead argued for a strictly concentric

In geometry, two or more objects are said to be concentric, coaxal, or coaxial when they share the same center or axis. Circles, regular polygons and regular polyhedra, and spheres may be concentric to one another (sharing the same center ...

model of the universe. He wrote the following criticism on the Ptolemaic model of planetary motion:

Averroes' contemporary, Maimonides

Musa ibn Maimon (1138–1204), commonly known as Maimonides (); la, Moses Maimonides and also referred to by the acronym Rambam ( he, רמב״ם), was a Sephardic Jewish philosopher who became one of the most prolific and influential Torah ...

, wrote the following on the planetary model proposed by Ibn Bajjah

Abū Bakr Muḥammad ibn Yaḥyà ibn aṣ-Ṣā’igh at-Tūjībī ibn Bājja ( ar, أبو بكر محمد بن يحيى بن الصائغ التجيبي بن باجة), best known by his Latinised name Avempace (; – 1138), was an A ...

(Avempace):

Ibn Bajjah also proposed the Milky Way

The Milky Way is the galaxy that includes our Solar System, with the name describing the galaxy's appearance from Earth: a hazy band of light seen in the night sky formed from stars that cannot be individually distinguished by the naked ey ...

galaxy

A galaxy is a system of stars, stellar remnants, interstellar gas, dust, dark matter, bound together by gravity. The word is derived from the Greek ' (), literally 'milky', a reference to the Milky Way galaxy that contains the Solar Sys ...

to be made up of many stars but that it appears to be a continuous image due to the effect of refraction

In physics, refraction is the redirection of a wave as it passes from one medium to another. The redirection can be caused by the wave's change in speed or by a change in the medium. Refraction of light is the most commonly observed phenomen ...

in the Earth's atmosphere

The atmosphere of Earth is the layer of gases, known collectively as air, retained by Earth's gravity that surrounds the planet and forms its planetary atmosphere. The atmosphere of Earth protects life on Earth by creating pressure allowing f ...

. Later in the 12th century, his successors Ibn Tufail

Ibn Ṭufail (full Arabic name: ; Latinized form: ''Abubacer Aben Tofail''; Anglicized form: ''Abubekar'' or ''Abu Jaafar Ebn Tophail''; c. 1105 – 1185) was an Arab Andalusian Muslim polymath: a writer, Islamic philosopher, Islamic theo ...

and Nur Ed-Din Al Betrugi

Nur ad-Din al-Bitruji () (also spelled Nur al-Din Ibn Ishaq al-Betrugi and Abu Ishâk ibn al-Bitrogi) (known in the West by the Latinized name of Alpetragius) (died c. 1204) was an Iberian-Arab astronomer and a Qadi in al-Andalus. Al-Biṭrūjī ...

(Alpetragius) were the first to propose planetary models without any equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plan ...

, epicycles or eccentrics. Their configurations, however, were not accepted due to the numerical predictions of the planetary positions in their models being less accurate than that of the Ptolemaic model, mainly because they followed Aristotle

Aristotle (; grc-gre, Ἀριστοτέλης ''Aristotélēs'', ; 384–322 BC) was a Greek philosopher and polymath during the Classical Greece, Classical period in Ancient Greece. Taught by Plato, he was the founder of the Peripatet ...

's notion of perfectly uniform circular motion

In physics, circular motion is a movement of an object along the circumference of a circle or rotation along a circular path. It can be uniform, with constant angular rate of rotation and constant speed, or non-uniform with a changing rate of rot ...

.

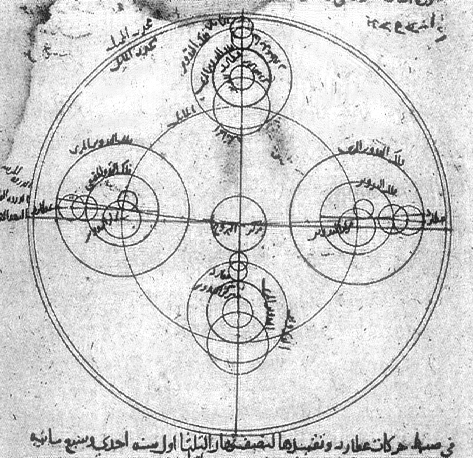

Maragha Revolution

The "Maragha Revolution" refers to theMaragheh

Maragheh ( fa, مراغه, Marāgheh or ''Marāgha''; az, ماراغا ) is a city and capital of Maragheh County, East Azerbaijan Province, Iran. Maragheh is on the bank of the river Sufi Chay. The population consists mostly of Iranian Azerb ...

school's revolution

In political science, a revolution (Latin: ''revolutio'', "a turn around") is a fundamental and relatively sudden change in political power and political organization which occurs when the population revolts against the government, typically due ...

against Ptolemaic astronomy. The "Maragha school" was an astronomical tradition beginning in the Maragheh observatory

The Maragheh observatory ( Persian: رصدخانه مراغه), also spelled Maragha, Maragah, Marageh, and Maraga, was an astronomical observatory established in the mid 13th century under the patronage of the Ilkhanid Hulagu and the directorshi ...

and continuing with astronomers from Damascus and Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top: Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zi ...

. Like their Andalusian predecessors, the Maragha astronomers attempted to solve the equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plan ...

problem and produce alternative configurations to the Ptolemaic model. They were more successful than their Andalusian predecessors in producing non-Ptolemaic configurations which eliminated the equant and eccentrics, were more accurate than the Ptolemaic model in numerically predicting planetary positions, and were in better agreement with empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. Th ...

s. The most important of the Maragha astronomers included Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (d. 1266), Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

(1201–1274), Najm al-Dīn al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī (d. 1277), Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236–1311), Sadr al-Sharia al-Bukhari (c. 1347), Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ansari known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir ( ar, ابن الشاطر; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as ''muwaqqit'' (موقت, religious t ...

(1304–1375), Ali Qushji

Ala al-Dīn Ali ibn Muhammed (1403 – 16 December 1474), known as Ali Qushji ( Ottoman Turkish : علی قوشچی, ''kuşçu'' – falconer in Turkish; Latin: ''Ali Kushgii'') was a Timurid theologian, jurist, astronomer, mathematician ...

(c. 1474), al-Birjandi (d. 1525) and Shams al-Din al-Khafri (d. 1550).

Some have described their achievements in the 13th and 14th centuries as a "Maragha Revolution", "Maragha School Revolution", or "Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution was a series of events that marked the emergence of modern science during the early modern period, when developments in mathematics, physics, astronomy, biology (including human anatomy) and chemistry transformed ...

before the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass id ...

". An important aspect of this revolution included the realization that astronomy should aim to describe the behavior of physical bodies in mathematical

Mathematics is an area of knowledge that includes the topics of numbers, formulas and related structures, shapes and the spaces in which they are contained, and quantities and their changes. These topics are represented in modern mathematics ...

language, and should not remain a mathematical hypothesis

A hypothesis (plural hypotheses) is a proposed explanation for a phenomenon. For a hypothesis to be a scientific hypothesis, the scientific method requires that one can testable, test it. Scientists generally base scientific hypotheses on prev ...

, which would only save the phenomena

A phenomenon ( : phenomena) is an observable event. The term came into its modern philosophical usage through Immanuel Kant, who contrasted it with the noumenon, which ''cannot'' be directly observed. Kant was heavily influenced by Gottfried ...

. The Maragha astronomers also realized that the Aristotelian view of motion

In physics, motion is the phenomenon in which an object changes its position with respect to time. Motion is mathematically described in terms of displacement, distance, velocity, acceleration, speed and frame of reference to an observer and mea ...

in the universe being only circular or linear

Linearity is the property of a mathematical relationship ('' function'') that can be graphically represented as a straight line. Linearity is closely related to '' proportionality''. Examples in physics include rectilinear motion, the linear ...

was not true, as the Tusi-couple showed that linear motion could also be produced by applying circular motions only.

Unlike the ancient Greek and Hellenistic astronomers who were not concerned with the coherence between the mathematical and physical principles of a planetary theory, Islamic astronomers insisted on the need to match the mathematics with the real world surrounding them, which gradually evolved from a reality based on Aristotelian physics

Aristotelian physics is the form of natural science described in the works of the Greek philosopher Aristotle (384–322 BC). In his work ''Physics'', Aristotle intended to establish general principles of change that govern all natural bodies, ...

to one based on an empirical and mathematical physics

Physics is the natural science that studies matter, its fundamental constituents, its motion and behavior through space and time, and the related entities of energy and force. "Physical science is that department of knowledge which rel ...

after the work of Ibn al-Shatir. The Maragha Revolution was thus characterized by a shift away from the philosophical foundations of Aristotelian cosmology and Ptolemaic astronomy

In astronomy, the geocentric model (also known as geocentrism, often exemplified specifically by the Ptolemaic system) is a superseded description of the Universe with Earth at the center. Under most geocentric models, the Sun, Moon, stars, an ...

and towards a greater emphasis on the empirical observation and mathematization of astronomy and of nature

Nature, in the broadest sense, is the physical world or universe. "Nature" can refer to the phenomena of the physical world, and also to life in general. The study of nature is a large, if not the only, part of science. Although humans ar ...

in general, as exemplified in the works of Ibn al-Shatir, Qushji, al-Birjandi and al-Khafri.

Other achievements of the Maragha school include the first empirical observational evidence for the Earth's rotation on its axis by al-Tusi and Qushji, the separation of

Other achievements of the Maragha school include the first empirical observational evidence for the Earth's rotation on its axis by al-Tusi and Qushji, the separation of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

from astronomy by Ibn al-Shatir and Qushji, the rejection of the Ptolemaic model on empirical rather than philosophical

Philosophy (from , ) is the systematized study of general and fundamental questions, such as those about existence, reason, knowledge, values, mind, and language. Such questions are often posed as problems to be studied or resolved. Som ...

grounds by Ibn al-Shatir, and the development of a non-Ptolemaic model by Ibn al-Shatir that was mathematically identical to the heliocentric Copernical model.

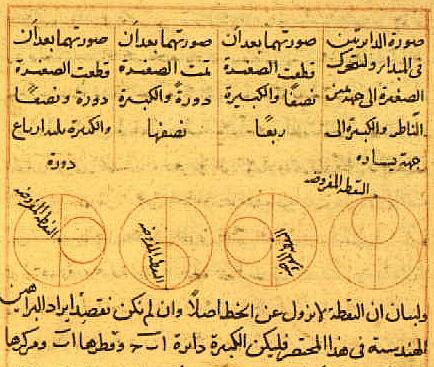

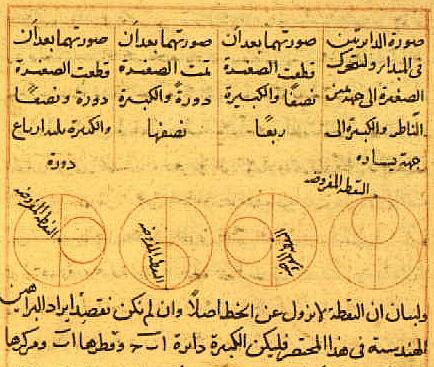

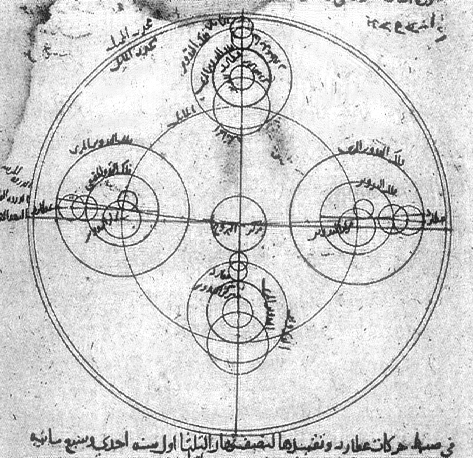

Mo'ayyeduddin Urdi (d. 1266) was the first of the Maragheh astronomers to develop a non-Ptolemaic model, and he proposed a new theorem, the "Urdi lemma". Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

(1201–1274) resolved significant problems in the Ptolemaic system by developing the Tusi-couple as an alternative to the physically problematic equant

Equant (or punctum aequans) is a mathematical concept developed by Claudius Ptolemy in the 2nd century AD to account for the observed motion of the planets. The equant is used to explain the observed speed change in different stages of the plan ...

introduced by Ptolemy. Tusi's student Qutb al-Din al-Shirazi (1236–1311), in his ''The Limit of Accomplishment concerning Knowledge of the Heavens'', discussed the possibility of heliocentrism

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth ...

. Al-Qazwīnī al-Kātibī, who also worked at the Maragheh observatory, in his ''Hikmat al-'Ain'', wrote an argument for a heliocentric model, though he later abandoned the idea.

Ibn al-Shatir

ʿAbu al-Ḥasan Alāʾ al‐Dīn ʿAlī ibn Ibrāhīm al-Ansari known as Ibn al-Shatir or Ibn ash-Shatir ( ar, ابن الشاطر; 1304–1375) was an Arab astronomer, mathematician and engineer. He worked as ''muwaqqit'' (موقت, religious t ...

(1304–1375) of Damascus, in ''A Final Inquiry Concerning the Rectification of Planetary Theory'', incorporated the Urdi lemma, and eliminated the need for an equant by introducing an extra epicycle (the Tusi-couple), departing from the Ptolemaic system in a way that was mathematically identical to what Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...

did in the 16th century. Unlike previous astronomers before him, Ibn al-Shatir was not concerned with adhering to the theoretical principles of natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

or Aristotelian cosmology

Cosmology () is a branch of physics and metaphysics dealing with the nature of the universe. The term ''cosmology'' was first used in English in 1656 in Thomas Blount's ''Glossographia'', and in 1731 taken up in Latin by German philosophe ...

, but rather to produce a model that was more consistent with empirical

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

observations. For example, it was Ibn al-Shatir's concern for observational accuracy which led him to eliminate the epicycle in the Ptolemaic solar model and all the eccentrics, epicycles and equant in the Ptolemaic lunar model. His model was thus in better agreement with empirical observation

Observation is the active acquisition of information from a primary source. In living beings, observation employs the senses. In science, observation can also involve the perception and recording of data via the use of scientific instruments. Th ...

s than any previous model, and was also the first that permitted empirical testing. His work thus marked a turning point in astronomy, which may be considered a "Scientific Revolution before the Renaissance". His rectified model was later adapted into a heliocentric model

Heliocentrism (also known as the Heliocentric model) is the astronomical model in which the Earth and planets revolve around the Sun at the center of the universe. Historically, heliocentrism was opposed to geocentrism, which placed the Earth a ...

by Copernicus, which was mathematically achieved by reversing the direction of the last vector connecting the Earth to the Sun.

An area of active discussion in the Maragheh school, and later the Samarkand

fa, سمرقند

, native_name_lang =

, settlement_type = City

, image_skyline =

, image_caption = Clockwise from the top: Registan square, Shah-i-Zinda necropolis, Bibi-Khanym Mosque, view inside Shah-i-Zi ...

and Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

observatories, was the possibility of the Earth's rotation. Supporters of this theory included Nasīr al-Dīn al-Tūsī

Muhammad ibn Muhammad ibn al-Hasan al-Tūsī ( fa, محمد ابن محمد ابن حسن طوسی 18 February 1201 – 26 June 1274), better known as Nasir al-Din al-Tusi ( fa, نصیر الدین طوسی, links=no; or simply Tusi in the West ...

, Nizam al-Din al-Nisaburi (c. 1311), al-Sayyid al-Sharif al-Jurjani (1339–1413), Ali Qushji (d. 1474), and Abd al-Ali al-Birjandi (d. 1525). Al-Tusi was the first to present empirical observational evidence of the Earth's rotation, using the location of comet

A comet is an icy, small Solar System body that, when passing close to the Sun, warms and begins to release gases, a process that is called outgassing. This produces a visible atmosphere or Coma (cometary), coma, and sometimes also a Comet ta ...

s relevant to the Earth as evidence, which Qushji elaborated on with further empirical observations while rejecting Aristotelian natural philosophy

Natural philosophy or philosophy of nature (from Latin ''philosophia naturalis'') is the philosophical study of physics, that is, nature and the physical universe. It was dominant before the development of modern science.

From the ancient wor ...

altogether. Both of their arguments were similar to the arguments later used by Nicolaus Copernicus

Nicolaus Copernicus (; pl, Mikołaj Kopernik; gml, Niklas Koppernigk, german: Nikolaus Kopernikus; 19 February 1473 – 24 May 1543) was a Renaissance polymath, active as a mathematician, astronomer, and Catholic canon, who formulat ...