, image = Irish ancestry in the USA 2018; Where Irish eyes are Smiling.png

, image_caption =

, popplace =

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

Scranton

Scranton is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Lackawanna County, Pennsylvania, Lackawanna County. With a population of 76,328 as of the 2020 United States census, 2020 U ...

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

Pittsburgh

Pittsburgh ( ) is a city in the Commonwealth (U.S. state), Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, United States, and the county seat of Allegheny County, Pennsylvania, Allegheny County. It is the most populous city in both Allegheny County and Wester ...

Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U.S. ...

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

Baltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

Detroit

Detroit ( , ; , ) is the largest city in the U.S. state of Michigan. It is also the largest U.S. city on the United States–Canada border, and the seat of government of Wayne County. The City of Detroit had a population of 639,111 at th ...

Milwaukee

Milwaukee ( ), officially the City of Milwaukee, is both the most populous and most densely populated city in the U.S. state of Wisconsin and the county seat of Milwaukee County. With a population of 577,222 at the 2020 census, Milwaukee is ...

Louisville

Louisville ( , , ) is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Kentucky and the 28th most-populous city in the United States. Louisville is the historical seat and, since 2003, the nominal seat of Jefferson County, on the Indiana border.

...

New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

Delaware Valley

The Delaware Valley is a metropolitan region on the East Coast of the United States that comprises and surrounds Philadelphia, the sixth most populous city in the nation and 68th largest city in the world as of 2020. The toponym Delaware Val ...

Coal Region

The Coal Region is a region of Northeastern Pennsylvania. It is known for being home to the largest known deposits of anthracite, anthracite coal in the world with an estimated reserve of seven billion short tons.

The region is typically define ...

Los Angeles

Los Angeles ( ; es, Los Ángeles, link=no , ), often referred to by its initials L.A., is the largest city in the state of California and the second most populous city in the United States after New York City, as well as one of the world' ...

Las Vegas

Las Vegas (; Spanish for "The Meadows"), often known simply as Vegas, is the 25th-most populous city in the United States, the most populous city in the state of Nevada, and the county seat of Clark County. The city anchors the Las Vegas ...

Atlanta

Atlanta ( ) is the capital and most populous city of the U.S. state of Georgia. It is the seat of Fulton County, the most populous county in Georgia, but its territory falls in both Fulton and DeKalb counties. With a population of 498,715 ...

Sacramento

)

, image_map = Sacramento County California Incorporated and Unincorporated areas Sacramento Highlighted.svg

, mapsize = 250x200px

, map_caption = Location within Sacramento ...

San Diego

San Diego ( , ; ) is a city on the Pacific Ocean coast of Southern California located immediately adjacent to the Mexico–United States border. With a 2020 population of 1,386,932, it is the List of United States cities by population, eigh ...

Houston

Houston (; ) is the most populous city in Texas, the most populous city in the Southern United States, the fourth-most populous city in the United States, and the sixth-most populous city in North America, with a population of 2,304,580 in ...

Dallas

Dallas () is the List of municipalities in Texas, third largest city in Texas and the largest city in the Dallas–Fort Worth metroplex, the List of metropolitan statistical areas, fourth-largest metropolitan area in the United States at 7.5 ...

San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

Palm Springs, California

Palm Springs (Cahuilla: ''Séc-he'') is a desert resort city in Riverside County, California, United States, within the Colorado Desert's Coachella Valley. The city covers approximately , making it the largest city in Riverside County by land a ...

Fairbanks

Fairbanks is a home rule city and the borough seat of the Fairbanks North Star Borough in the U.S. state of Alaska. Fairbanks is the largest city in the Interior region of Alaska and the second largest in the state. The 2020 Census put the po ...

and most urban areas

, langs =

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

(

American English dialects); a scant speak

Irish

Irish may refer to:

Common meanings

* Someone or something of, from, or related to:

** Ireland, an island situated off the north-western coast of continental Europe

***Éire, Irish language name for the isle

** Northern Ireland, a constituent unit ...

, rels =

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

(51%)

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

(36%)

Other

Other often refers to:

* Other (philosophy), a concept in psychology and philosophy

Other or The Other may also refer to:

Film and television

* ''The Other'' (1913 film), a German silent film directed by Max Mack

* ''The Other'' (1930 film), a ...

(3%)

No religion (10%) (2006)

, related =

Anglo-Irish people

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

Breton Americans

Breton Americans are Americans of Breton descent from Brittany. An estimated 100,000 Bretons emigrated from Brittany to the United States between 1880 and 1980.

History

A large wave of Breton immigrants arrived in the New York City area during ...

Cornish Americans

Cornish Americans ( kw, Amerikanyon gernewek) are Americans who describe themselves as having Cornish ancestry, an ethnic group of Brittonic Celts native to Cornwall and the Scilly Isles, part of England in the United Kingdom. Although Cornish ...

English Americans

English Americans (historically known as Anglo-Americans) are Americans whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in England.

In the 2020 American Community Survey, 25.21 million self-identified as being of English origin.

The term is distin ...

Irish Australians

Irish Australians ( ga, Gael-Astrálaigh) are an ethnic group of Australians, Australian citizens of Irish descent, which include immigrants from and descendants whose ancestry originates from the Ireland, island of Ireland.

Irish Australians ...

Irish Canadians

ga, Gael-Cheanadaigh

, image = Irish_Canadian_population_by_province.svg

, image_caption = Irish Canadians as percent of population by province/territory

, population = 4,627,00013.4% of the Canadian population (2016)

, po ...

Irish Catholics

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the British ...

Manx Americans

Manx Americans are Americans of full or partial Manx ancestral origin or Manx people who reside in the United States of America.

Settlement in Ohio

The city of Cleveland, Ohio is said to have the highest concentration of Americans of Manx des ...

Scotch-Irish Americans

Scotch-Irish (or Scots-Irish) Americans are American descendants of Ulster Protestants who emigrated from Ulster in northern Ireland to America during the 18th and 19th centuries, whose ancestors had originally migrated to Ireland mainly from t ...

Scottish Americans

Scottish Americans or Scots Americans (Scottish Gaelic: ''Ameireaganaich Albannach''; sco, Scots-American) are Americans whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in Scotland. Scottish Americans are closely related to Scotch-Irish Americans, d ...

Scottish Canadians

Scottish Canadians are people of Scottish descent or heritage living in Canada. As the third-largest ethnic group in Canada and amongst the first Europeans to settle in the country, Scottish people have made a large impact on Canadian culture si ...

Ulster Protestants

Ulster Protestants ( ga, Protastúnaigh Ultach) are an ethnoreligious group in the Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about 43.5% of the population. Most Ulster Protestants are descendants of settlers who arrived from Britain in the ...

Ulster Scots people

The Ulster Scots ( Ulster-Scots: ''Ulstèr-Scotch''; ga, Albanaigh Ultach), also called Ulster Scots people (''Ulstèr-Scotch fowk'') or (in North America) Scotch-Irish (''Scotch-Airisch''), are an ethnic group in Ireland, who speak an Ulst ...

Welsh Americans

Welsh Americans ( cy, Americanwyr Cymreig) are an American ethnic group whose ancestry originates wholly or partly in Wales. In the 2008 U.S. Census community survey, an estimated 1.98 million Americans had Welsh ancestry, 0.6% of the total U. ...

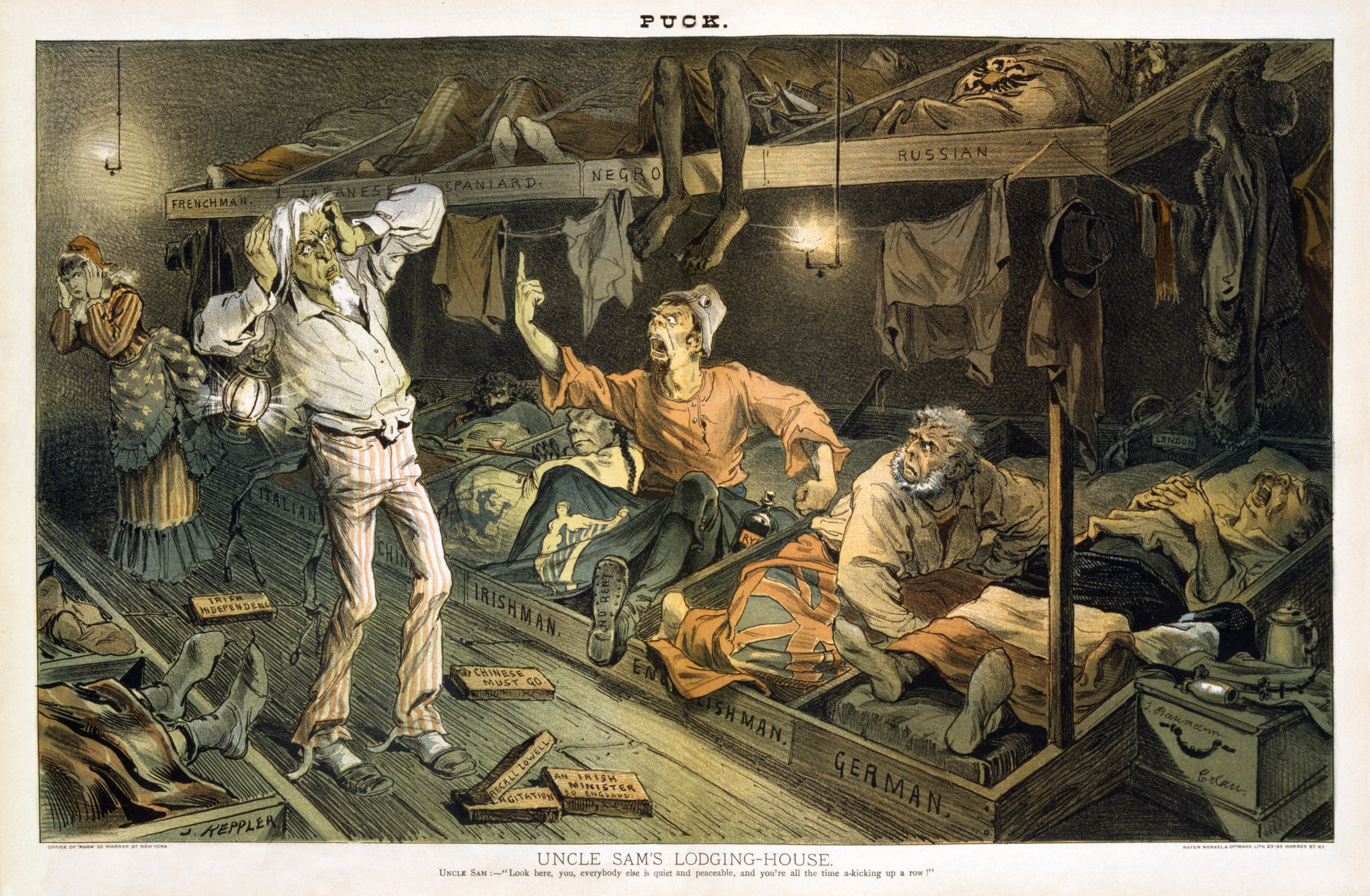

Irish Americans or Hiberno-Americans ( ga, Gael-Mheiriceánaigh) are Americans who have full or partial ancestry from

Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

. About 32 million Americans — 9.7% of the total population — identified as being Irish in the 2020

American Community Survey

The American Community Survey (ACS) is a demographics survey program conducted by the U.S. Census Bureau. It regularly gathers information previously contained only in the long form of the decennial census, such as ancestry, citizenship, educati ...

conducted by the

U.S. Census Bureau

The United States Census Bureau (USCB), officially the Bureau of the Census, is a principal agency of the U.S. Federal Statistical System, responsible for producing data about the American people and economy. The Census Bureau is part of the ...

.

Irish immigration to the United States

17th to mid-19th century

Some of the first Irish people to travel to the New World did so as members of the Spanish garrison in Florida during the 1560s, and small numbers of Irish colonists were involved in efforts to establish colonies in the Amazon region, in Newfoundland, and in Virginia between 1604 and the 1630s. According to historian Donald Akenson, there were "few if any" Irish were forcibly transported to the Americas during this period.

Irish immigration to the Americas was the result of a series of complex causes. The

Tudor conquest and

subsequent colonization during the 16th and 17th centuries had led to widespread social upheaval in Ireland, and drove many Irish people to try and seek a better life elsewhere; this coincided with the rapid establishment of

European colonies in the Americas, offering a source of emigration for prospective migrants. Most Irish immigrants to the Americas came as indentured servants, though others were merchants and landowners who served as key players in a variety of different mercantile and colonizing enterprises.

Significant numbers of Irish laborers began traveling to

English colonies

The English overseas possessions, also known as the English colonial empire, comprised a variety of overseas territories that were colonised, conquered, or otherwise acquired by the former Kingdom of England during the centuries before the Ac ...

such as Virginia, the Leeward Islands, and Barbados in the 1620s.

Half of the Irish immigrants to the

United States in its colonial era (1607–1775) came from the Irish province of

Ulster

Ulster (; ga, Ulaidh or ''Cúige Uladh'' ; sco, label= Ulster Scots, Ulstèr or ''Ulster'') is one of the four traditional Irish provinces. It is made up of nine counties: six of these constitute Northern Ireland (a part of the United King ...

, while the other half came from the other three provinces (

Leinster

Leinster ( ; ga, Laighin or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, situated in the southeast and east of Ireland. The province comprises the ancient Kingdoms of Meath, Leinster and Osraige. Following the 12th-century Norman invasion of Ir ...

,

Munster

Munster ( gle, an Mhumhain or ) is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the south of Ireland. In early Ireland, the Kingdom of Munster was one of the kingdoms of Gaelic Ireland ruled by a "king of over-kings" ( ga, rí ruirech). Following the ...

and

Connacht

Connacht ( ; ga, Connachta or ), is one of the provinces of Ireland, in the west of Ireland. Until the ninth century it consisted of several independent major Gaelic kingdoms (Uí Fiachrach, Uí Briúin, Uí Maine, Conmhaícne, and Delbhn ...

).

In the 17th century, immigration from Ireland to the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

was minimal,

confined mostly to male

indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

who were primarily

Catholic

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

and peaked with 8,000

prisoner-of-war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold prisoners of w ...

penal transports to the

Chesapeake Colonies

The Chesapeake Colonies were the Colony and Dominion of Virginia, later the Commonwealth of Virginia, and Province of Maryland, later Maryland, both colonies located in British America and centered on the Chesapeake Bay. Settlements of the Chesa ...

from the

Cromwellian conquest of Ireland

The Cromwellian conquest of Ireland or Cromwellian war in Ireland (1649–1653) was the re-conquest of Ireland by the forces of the English Parliament, led by Oliver Cromwell, during the Wars of the Three Kingdoms. Cromwell invaded Ireland wi ...

in the 1650s (out of a total of approximately 10,000 Catholic immigrants from Ireland to the United States prior to the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

in 1775).

Indentured servitude in British America

Indentured servitude in British America was the prominent system of labor in the British American colonies until it was eventually supplanted by slavery. During its time, the system was so prominent that more than half of all immigrants to Britis ...

emerged in part due to the high cost of passage across the Atlantic Ocean, and as a consequence, which colonies indentured servants immigrated to depended upon which colonies their patrons chose to immigrate to.

While the

Colony of Virginia

The Colony of Virginia, chartered in 1606 and settled in 1607, was the first enduring English colonial empire, English colony in North America, following failed attempts at settlement on Newfoundland (island), Newfoundland by Sir Humphrey GilbertG ...

passed laws prohibiting the free exercise of

Catholicism during the colonial period,

the

General Assembly

A general assembly or general meeting is a meeting of all the members of an organization or shareholders of a company.

Specific examples of general assembly include:

Churches

* General Assembly (presbyterian church), the highest court of presby ...

of the

Province of Maryland

The Province of Maryland was an English and later British colony in North America that existed from 1632 until 1776, when it joined the other twelve of the Thirteen Colonies in rebellion against Great Britain and became the U.S. state of Maryland ...

enacted laws in 1639 protecting

freedom of religion

Freedom of religion or religious liberty is a principle that supports the freedom of an individual or community, in public or private, to manifest religion or belief in teaching, practice, worship, and observance. It also includes the freedom ...

(following the instructions of a 1632 letter from

Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore

Cecil Calvert, 2nd Baron Baltimore (8 August 1605 – 30 November 1675), also often known as Cecilius Calvert, was an English nobleman, who was the first Proprietor of the Province of Maryland, ninth Proprietary Governor of the Colony of Newf ...

to his brother

Leonard Calvert

The Hon. Leonard Calvert (1606 – June 9, 1647) was the first proprietary governor of the Province of Maryland. He was the second son of The 1st Baron Baltimore (1579–1632), the first proprietor of Maryland. His elder brother Cecil (1605� ...

, the

1st Proprietary-Governor of Maryland), and the Maryland General Assembly later passed the 1649

Maryland Toleration Act

The Maryland Toleration Act, also known as the Act Concerning Religion, the first law in North America requiring religious tolerance for Christians. It was passed on April 21, 1649, by the assembly of the Maryland colony, in St. Mary's City in S ...

explicitly guaranteeing those privileges for Catholics.

Like the entire indentured servant population in the Chesapeake Colonies at the time, 40 to 50 percent died before completing their contracts. This was due in large part to the

Tidewater region's highly malignant disease environment, with most not establishing families and dying childless because the population of the Chesapeake Colonies, like the

Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

in the aggregate, was not sex-balanced until the 18th century because three-quarters of the immigrants to the Chesapeake Colonies were male (and in some periods, 4:1 or 6:1 male-to-female) and fewer than 1 percent were over the age of 35. As a consequence, the population only grew due to sustained immigration rather than

natural increase

In Demography, the rate of natural increase (RNI), also known as natural population change, is defined as the birth rate minus the death rate of a particular population, over a particular time period. It is typically expressed either as a number ...

, and many of those who survived their indentured servitude contracts left the region.

In 1650, all five Catholic churches with regular

services

Service may refer to:

Activities

* Administrative service, a required part of the workload of university faculty

* Civil service, the body of employees of a government

* Community service, volunteer service for the benefit of a community or a p ...

in the

eight British American colonies were located in Maryland. The 17th-century Maryland Catholic community had a high degree of

social capital

Social capital is "the networks of relationships among people who live and work in a particular society, enabling that society to function effectively". It involves the effective functioning of social groups through interpersonal relationships ...

. Catholic-Protestant

interdenominational marriage

Interdenominational marriage, sometimes called an inter-sect marriage or ecumenical marriage, is marriage between spouses professing a different denomination of same religion.

Interdenominational marriages are distinguished from interfaith ma ...

was not common, Catholic-Protestant intermarriages nearly always resulted in conversion to Catholicism by Protestant marital partners, and children who were born as the result of Catholic-Protestant intermarriages were nearly always raised as Catholics.

Additionally, 17th-century Maryland Catholics often stipulated in their

wills Wills may refer to:

* Will (law)

A will or testament is a legal document that expresses a person's (testator) wishes as to how their property ( estate) is to be distributed after their death and as to which person (executor) is to manage the pr ...

that their children be

disinherited if they renounced

Catholicism

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

.

In contrast to 17th-century Maryland, the

Plymouth

Plymouth () is a port city and unitary authority in South West England. It is located on the south coast of Devon, approximately south-west of Exeter and south-west of London. It is bordered by Cornwall to the west and south-west.

Plymouth ...

,

Massachusetts Bay

Massachusetts Bay is a bay on the Gulf of Maine that forms part of the central coastline of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts.

Description

The bay extends from Cape Ann on the north to Plymouth Harbor on the south, a distance of about . Its ...

and

Connecticut Colonies restricted suffrage to members of the

established Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

church, while the

Province of Carolina

Province of Carolina was a province of England (1663–1707) and Great Britain (1707–1712) that existed in North America and the Caribbean from 1663 until partitioned into North and South on January 24, 1712. It is part of present-day Alaba ...

did not restrict suffrage to members of the established

Anglican

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

church. The

Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations

The Colony of Rhode Island and Providence Plantations was one of the original Thirteen Colonies established on the east coast of America, bordering the Atlantic Ocean. It was founded by Roger Williams. It was an English colony from 1636 until ...

had no established church, while the former

New Netherland

New Netherland ( nl, Nieuw Nederland; la, Novum Belgium or ) was a 17th-century colonial province of the Dutch Republic that was located on the East Coast of the United States, east coast of what is now the United States. The claimed territor ...

colonies (

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

,

New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

, and

Delaware

Delaware ( ) is a state in the Mid-Atlantic region of the United States, bordering Maryland to its south and west; Pennsylvania to its north; and New Jersey and the Atlantic Ocean to its east. The state takes its name from the adjacent Del ...

) also had no established church under the

Duke's Laws, and the

Frame of Government

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When these princip ...

in

William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

's 1682 land grant established free exercise of religion for all Christians in the

Province of Pennsylvania

The Province of Pennsylvania, also known as the Pennsylvania Colony, was a British North American colony founded by William Penn after receiving a land grant from Charles II of England in 1681. The name Pennsylvania ("Penn's Woods") refers to W ...

.

Following the

Glorious Revolution

The Glorious Revolution; gd, Rèabhlaid Ghlòrmhor; cy, Chwyldro Gogoneddus , also known as the ''Glorieuze Overtocht'' or ''Glorious Crossing'' in the Netherlands, is the sequence of events leading to the deposition of King James II and ...

(1688–1689), Catholics were

disenfranchised

Disfranchisement, also called disenfranchisement, or voter disqualification is the restriction of suffrage (the right to vote) of a person or group of people, or a practice that has the effect of preventing a person exercising the right to vote. D ...

in Maryland, New York, Rhode Island, Carolina, and Virginia,

although in Maryland, suffrage was restored in 1702.

In 1692, the Maryland General Assembly established the

Church of England

The Church of England (C of E) is the established Christian church in England and the mother church of the international Anglican Communion. It traces its history to the Christian church recorded as existing in the Roman province of Britain ...

as the official state church.

In 1698 and 1699, Maryland, Virginia, and Carolina passed laws specifically limiting immigration of Irish Catholic indentured servants.

In 1700, the estimated population of Maryland was 29,600,

about 2,500 of which were Catholic.

In the 18th century, emigration from Ireland to the Thirteen Colonies shifted from being primarily Catholic to being primarily

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

, and with the exception of the 1790s it would remain so until the mid-to-late 1830s,

with

Presbyterians

Presbyterianism is a part of the Reformed tradition within Protestantism that broke from the Roman Catholic Church in Scotland by John Knox, who was a priest at St. Giles Cathedral (Church of Scotland). Presbyterian churches derive their nam ...

constituting the

absolute majority

A supermajority, supra-majority, qualified majority, or special majority is a requirement for a proposal to gain a specified level of support which is greater than the threshold of more than one-half used for a simple majority. Supermajority ru ...

until 1835.

These Protestant immigrants were principally descended from

Scottish and

English

English usually refers to:

* English language

* English people

English may also refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* ''English'', an adjective for something of, from, or related to England

** English national ide ...

pastoralists and colonial administrators (often from the South/

Lowlands

Upland and lowland are conditional descriptions of a plain based on elevation above sea level. In studies of the ecology of freshwater rivers, habitats are classified as upland or lowland.

Definitions

Upland and lowland are portions of p ...

of Scotland and the bordering

North of England

Northern England, also known as the North of England, the North Country, or simply the North, is the northern area of England. It broadly corresponds to the former borders of Angle Northumbria, the Anglo-Scandinavian Kingdom of Jorvik, and the ...

) who had in the previous century settled the

Plantations of Ireland

Plantations in 16th- and 17th-century Ireland involved the confiscation of Irish-owned land by the English Crown and the colonisation of this land with settlers from Great Britain. The Crown saw the plantations as a means of controlling, angl ...

, the largest of which was the

Plantation of Ulster

The Plantation of Ulster ( gle, Plandáil Uladh; Ulster-Scots: ''Plantin o Ulstèr'') was the organised colonisation (''plantation'') of Ulstera province of Irelandby people from Great Britain during the reign of King James I. Most of the sett ...

,

and these Protestant immigrants primarily migrated as families rather than as individuals.

In Ireland, they are referred to as the "

Ulster Scots" and the "

Anglo-Irish

Anglo-Irish people () denotes an ethnic, social and religious grouping who are mostly the descendants and successors of the English Protestant Ascendancy in Ireland. They mostly belong to the Anglican Church of Ireland, which was the establis ...

" respectively, and because the Protestant population in Ireland was and remains concentrated in Ulster, and because after the

partition of Ireland

The partition of Ireland ( ga, críochdheighilt na hÉireann) was the process by which the Government of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland divided Ireland into two self-governing polities: Northern Ireland and Southern Ireland. I ...

in the 20th century Protestants in Northern Ireland on census reports have largely since self-identified their

national identity

National identity is a person's identity or sense of belonging to one or more states or to one or more nations. It is the sense of "a nation as a cohesive whole, as represented by distinctive traditions, culture, and language". National identity ...

as "British" rather than "Irish" or "Northern Irish," Protestants in Ireland are collectively referred to as the "

Ulster Protestants

Ulster Protestants ( ga, Protastúnaigh Ultach) are an ethnoreligious group in the Irish province of Ulster, where they make up about 43.5% of the population. Most Ulster Protestants are descendants of settlers who arrived from Britain in the ...

."

Additionally, the Ulster Scots and Anglo-Irish intermarried to some degree,

and the Ulster Scots also intermarried with

Huguenot

The Huguenots ( , also , ) were a religious group of French Protestants who held to the Reformed, or Calvinist, tradition of Protestantism. The term, which may be derived from the name of a Swiss political leader, the Genevan burgomaster Be ...

refugees from the

Kingdom of France

The Kingdom of France ( fro, Reaume de France; frm, Royaulme de France; french: link=yes, Royaume de France) is the historiographical name or umbrella term given to various political entities of France in the medieval and early modern period. ...

following the 1685

Edict of Fontainebleau

The Edict of Fontainebleau (22 October 1685) was an edict issued by French King Louis XIV and is also known as the Revocation of the Edict of Nantes. The Edict of Nantes (1598) had granted Huguenots the right to practice their religion without s ...

issued by

Louis XIV

, house = Bourbon

, father = Louis XIII

, mother = Anne of Austria

, birth_date =

, birth_place = Château de Saint-Germain-en-Laye, Saint-Germain-en-Laye, France

, death_date =

, death_place = Palace of Vers ...

,

and some of the Anglo-Irish settlers were actually

Welsh

Welsh may refer to:

Related to Wales

* Welsh, referring or related to Wales

* Welsh language, a Brittonic Celtic language spoken in Wales

* Welsh people

People

* Welsh (surname)

* Sometimes used as a synonym for the ancient Britons (Celtic peop ...

or

Manx.

They seldom intermarried with the

Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the British ...

population in part because intermarriage between Protestants and Catholics was banned by the

Penal Laws (1691–1778) that gave rise the

Protestant Ascendancy

The ''Protestant Ascendancy'', known simply as the ''Ascendancy'', was the political, economic, and social domination of Ireland between the 17th century and the early 20th century by a minority of landowners, Protestant clergy, and members of th ...

, which rendered any children who were born to extralegal Catholic-Protestant intermarriages

illegitimate

Legitimacy, in traditional Western common law, is the status of a child born to parents who are legally married to each other, and of a child conceived before the parents obtain a legal divorce. Conversely, ''illegitimacy'', also known as ''b ...

and legally ineligible to inherit their parents' property under

English law

English law is the common law legal system of England and Wales, comprising mainly criminal law and civil law, each branch having its own courts and procedures.

Principal elements of English law

Although the common law has, historically, be ...

(while Presbyterian marriages were not even recognized by the state).

In turn, the

canon law of the Catholic Church

The canon law of the Catholic Church ("canon law" comes from Latin ') is "how the Church organizes and governs herself". It is the system of laws and ecclesiastical legal principles made and enforced by the hierarchical authorities of the Cathol ...

also

designated Catholic-Protestant intermarriages illegitimate until

Pope Pius VI

Pope Pius VI ( it, Pio VI; born Count Giovanni Angelo Braschi, 25 December 171729 August 1799) was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 15 February 1775 to his death in August 1799.

Pius VI condemned the French Revoluti ...

extended

Pope Benedict XIV

Pope Benedict XIV ( la, Benedictus XIV; it, Benedetto XIV; 31 March 1675 – 3 May 1758), born Prospero Lorenzo Lambertini, was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 17 August 1740 to his death in May 1758.Antipope ...

's

matrimonial dispensation

In the jurisprudence of the canon law of the Catholic Church, a dispensation is the exemption from the immediate obligation of law in certain cases.The Law of Christ Vol. I, pg. 284 Its object is to modify the hardship often arising from the ...

to Ireland in 1785 for the ''

Tametsi

''Tametsi'' (Latin, "although") is the legislation of the Catholic Church which was in force from 1563 until Easter 1908 concerning clandestine marriage. It was named, as is customary in Latin Rite ecclesiastical documents, for the first word of ...

'' decree of the

Council of Trent

The Council of Trent ( la, Concilium Tridentinum), held between 1545 and 1563 in Trento, Trent (or Trento), now in northern Italian Peninsula, Italy, was the 19th ecumenical council of the Catholic Church. Prompted by the Protestant Reformation ...

(1563),

and Irish Catholics almost never converted to Protestant churches during the

Reformation

The Reformation (alternatively named the Protestant Reformation or the European Reformation) was a major movement within Western Christianity in 16th-century Europe that posed a religious and political challenge to the Catholic Church and in ...

.

Catholic-Protestant intermarriage would remain rare in Ireland through the early 20th century.

In 1704, the Maryland General Assembly passed a law which banned the

Jesuits

The Society of Jesus ( la, Societas Iesu; abbreviation: SJ), also known as the Jesuits (; la, Iesuitæ), is a religious order (Catholic), religious order of clerics regular of pontifical right for men in the Catholic Church headquartered in Rom ...

from

proselytizing

Proselytism () is the policy of attempting to convert people's religious or political beliefs. Proselytism is illegal in some countries.

Some draw distinctions between ''evangelism'' or '' Da‘wah'' and proselytism regarding proselytism as invol ...

,

baptizing

Baptism (from grc-x-koine, βάπτισμα, váptisma) is a form of ritual purification—a characteristic of many religions throughout time and geography. In Christianity, it is a Christian sacrament of initiation and adoption, almost inv ...

children other than those with Catholic parents, and

publicly conducting Catholic Mass

The Mass is the central liturgical service of the Eucharist in the Catholic Church, in which bread and wine are consecrated and become the body and blood of Christ. As defined by the Church at the Council of Trent, in the Mass, "the same Christ ...

. Two months after its passage, the General Assembly modified the legislation to allow Mass to be privately conducted for an 18-month period. In 1707, the General Assembly passed a law which permanently allowed Mass to be privately conducted. During this period, the General Assembly also began levying taxes on the passage of Irish Catholic indentured servants. In 1718, the General Assembly required a

religious test A religious test is a legal requirement to swear faith to a specific religion or sect, or to renounce the same.

In the United Kingdom

British Test Act of 1673 and 1678

The Test Act of 1673 in England obligated all persons filling any office, ci ...

for voting that resumed disenfranchisement of Catholics.

However, lax enforcement of

penal laws in Maryland (due to its population being overwhelmingly rural) enabled churches on Jesuit-operated farms and plantations to grow and become stable

parishes

A parish is a territorial entity in many Christian denominations, constituting a division within a diocese. A parish is under the pastoral care and clerical jurisdiction of a priest, often termed a parish priest, who might be assisted by one or m ...

.

In 1750, of the 30 Catholic churches with regular services in the Thirteen Colonies, 15 were located in Maryland, 11 in Pennsylvania, and 4 in the former New Netherland colonies. By 1756, the number of Catholics in Maryland had increased to approximately 7,000,

which increased further to 20,000 by 1765.

In Pennsylvania, there were approximately 3,000 Catholics in 1756 and 6,000 by 1765 (the large majority of the Pennsylvania Catholic population was from

Germany

Germany,, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It is the second most populous country in Europe after Russia, and the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany is situated betwe ...

).

From 1717 to 1775, though scholarly estimates vary, the most common approximation is that 250,000 immigrants from Ireland emigrated to the Thirteen Colonies. By the beginning of the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

in 1775, approximately only 2 to 3 percent of the colonial

labor force

The workforce or labour force is a concept referring to the pool of human beings either in employment or in unemployment. It is generally used to describe those working for a single company or industry, but can also apply to a geographic regio ...

was composed of indentured servants, and of those arriving from Britain from 1773 to 1776, fewer than 5 percent were from Ireland (while 85 percent remained male and 72 percent went to the

Southern Colonies).

Immigration during the war came to a standstill except by 5,000

German

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**Ge ...

mercenaries from

Hesse

Hesse (, , ) or Hessia (, ; german: Hessen ), officially the State of Hessen (german: links=no, Land Hessen), is a States of Germany, state in Germany. Its capital city is Wiesbaden, and the largest urban area is Frankfurt. Two other major histor ...

who remained in the country following the war.

Out of the 115 killed at the

Battle of Bunker Hill

The Battle of Bunker Hill was fought on June 17, 1775, during the Siege of Boston in the first stage of the American Revolutionary War. The battle is named after Bunker Hill in Charlestown, Massachusetts, which was peripherally involved in ...

, 22 were Irish-born. Their names include Callaghan, Casey, Collins, Connelly, Dillon, Donohue, Flynn, McGrath, Nugent, Shannon, and Sullivan

By the end of the war in 1783, there were approximately 24,000 to 25,000 Catholics in the United States (including 3,000

slaves

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

) out of a total population of approximately 3 million (or less than 1 percent).

The majority of the Catholic population in the United States during the colonial period came from

England

England is a country that is part of the United Kingdom. It shares land borders with Wales to its west and Scotland to its north. The Irish Sea lies northwest and the Celtic Sea to the southwest. It is separated from continental Europe b ...

, Germany, and

France

France (), officially the French Republic ( ), is a country primarily located in Western Europe. It also comprises of Overseas France, overseas regions and territories in the Americas and the Atlantic Ocean, Atlantic, Pacific Ocean, Pac ...

, not Ireland,

despite failed academic efforts by Irish

historiographers

Historiography is the study of the methods of historians in developing history as an academic discipline, and by extension is any body of historical work on a particular subject. The historiography of a specific topic covers how historians hav ...

to demonstrate Irish Catholics as being more numerous in the colonial period than previous scholarship had indicated.

By 1790, approximately 400,000 people of Irish birth or ancestry lived in the United States (or greater than 10 percent of the total population of approximately 3.9 million).

The U.S. Bureau of the Census estimates 2% of the United States population in 1776 was of native Irish heritage. The Catholic population grew to approximately 50,000 by 1800 (or less than 1 percent of the total population of approximately 5.3 million) due to increased Catholic emigration from Ireland during the 1790s.

In the 18th-century Thirteen Colonies and the independent United States, while

interethnic marriage

Interethnic marriage is a form of exogamy that involves a marriage between spouses who belong to different ethnic groups or races. Intra-racial interethnic marriage was historically not a taboo in the United States.Yen, Hope (2012-02-16)Interraci ...

among Catholics remained a dominant pattern, Catholic-Protestant intermarriage became more common (notably in the

Shenandoah Valley

The Shenandoah Valley () is a geographic valley and cultural region of western Virginia and the Eastern Panhandle of West Virginia. The valley is bounded to the east by the Blue Ridge Mountains, to the west by the eastern front of the Ridge- ...

where intermarriage among Ulster Protestants and the significant minority of Irish Catholics in particular was not uncommon or stigmatized),

and while fewer Catholic parents required that their children be disinherited in their wills if they renounced Catholicism, it remained more common among Catholic parents to do so if their children renounced their parents faith in proportion to the rest of the U.S. population.

Despite this, many Irish Catholics that immigrated to the United States from 1770 to 1830 converted to

Baptist

Baptists form a major branch of Protestantism distinguished by baptizing professing Christian believers only (believer's baptism), and doing so by complete immersion. Baptist churches also generally subscribe to the doctrines of soul compete ...

and

Methodist

Methodism, also called the Methodist movement, is a group of historically related denominations of Protestant Christianity whose origins, doctrine and practice derive from the life and teachings of John Wesley. George Whitefield and John's b ...

churches during the

Second Great Awakening

The Second Great Awakening was a Protestant religious revival during the early 19th century in the United States. The Second Great Awakening, which spread religion through revivals and emotional preaching, sparked a number of reform movements. R ...

(1790–1840).

In between the end of the American Revolutionary War in 1783 and the

War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It bega ...

, 100,000 immigrants came from Ulster to the United States.

During the

French Revolutionary Wars

The French Revolutionary Wars (french: Guerres de la Révolution française) were a series of sweeping military conflicts lasting from 1792 until 1802 and resulting from the French Revolution. They pitted French First Republic, France against Ki ...

(1792–1802) and

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fren ...

(1803–1815), there was a 22-year

economic expansion

An economic expansion is an increase in the level of economic activity, and of the goods and services available. It is a period of economic growth as measured by a rise in real GDP. The explanation of fluctuations in aggregate economic activity ...

in Ireland due to increased need for agricultural products for British soldiers and an expanding population in England. Following the conclusion of the

War of the Seventh Coalition

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

and

Napoleon

Napoleon Bonaparte ; it, Napoleone Bonaparte, ; co, Napulione Buonaparte. (born Napoleone Buonaparte; 15 August 1769 – 5 May 1821), later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military commander and political leader who ...

's exile to

Saint Helena

Saint Helena () is a British overseas territory located in the South Atlantic Ocean. It is a remote volcanic tropical island west of the coast of south-western Africa, and east of Rio de Janeiro in South America. It is one of three constitu ...

in 1815, there was a

six-year international

economic depression

An economic depression is a period of carried long-term economical downturn that is result of lowered economic activity in one major or more national economies. Economic depression maybe related to one specific country were there is some economic ...

that led to

plummeting grain prices and a cropland rent spike in Ireland.

From 1815 to 1845, 500,000 more Irish Protestant immigrants came from Ireland to the United States,

as part of a migration of approximately 1 million immigrants from Ireland from 1820 to 1845.

In 1820, following the

Louisiana Purchase

The Louisiana Purchase (french: Vente de la Louisiane, translation=Sale of Louisiana) was the acquisition of the territory of Louisiana by the United States from the French First Republic in 1803. In return for fifteen million dollars, or app ...

in 1804 and the

Adams–Onís Treaty

The Adams–Onís Treaty () of 1819, also known as the Transcontinental Treaty, the Florida Purchase Treaty, or the Florida Treaty,Weeks, p.168. was a treaty between the United States and Spain in 1819 that ceded Florida to the U.S. and defined t ...

in 1819, the Catholic population of the United States had grown to 195,000 (or approximately 2 percent of the total population of approximately 9.6 million).

By 1840, along with resumed immigration from Germany by the 1820s,

the Catholic population grew to 663,000 (or approximately 4 percent out of the total population of 17.1 million).

Following the

potato blight

''Phytophthora infestans'' is an oomycete or water mold, a fungus-like microorganism that causes the serious potato and tomato disease known as late blight or potato blight. Early blight, caused by ''Alternaria solani'', is also often called "po ...

in late 1845 that initiated the

Great Famine in Ireland, from 1846 to 1851, more than 1 million more Irish immigrated to the United States, 90 percent of whom were Catholic.

Many of the Famine immigrants to

New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

required

quarantine

A quarantine is a restriction on the movement of people, animals and goods which is intended to prevent the spread of disease or pests. It is often used in connection to disease and illness, preventing the movement of those who may have been ...

on

Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey by the Arthur Kill and the Kill Van Kull an ...

or

Blackwell's Island

Roosevelt Island is an island in New York City's East River, within the borough of Manhattan. It lies between Manhattan Island to the west, and the borough of Queens, on Long Island, to the east. Running from the equivalent of East 46th to 85 ...

and thousands died from

typhoid fever

Typhoid fever, also known as typhoid, is a disease caused by '' Salmonella'' serotype Typhi bacteria. Symptoms vary from mild to severe, and usually begin six to 30 days after exposure. Often there is a gradual onset of a high fever over several ...

or

cholera

Cholera is an infection of the small intestine by some strains of the bacterium ''Vibrio cholerae''. Symptoms may range from none, to mild, to severe. The classic symptom is large amounts of watery diarrhea that lasts a few days. Vomiting and ...

for reasons directly or indirectly related to the Famine.

By 1850, following the

Mexican–American War

The Mexican–American War, also known in the United States as the Mexican War and in Mexico as the (''United States intervention in Mexico''), was an armed conflict between the United States and Mexico from 1846 to 1848. It followed the 1 ...

(1846–1848) that left a residual population of 80,000

Mexicans

Mexicans ( es, mexicanos) are the citizens of the United Mexican States.

The most spoken language by Mexicans is Spanish language, Spanish, but some may also speak languages from 68 different Languages of Mexico, Indigenous linguistic groups ...

in the

Southwestern United States

The Southwestern United States, also known as the American Southwest or simply the Southwest, is a geographic and cultural region of the United States that generally includes Arizona, New Mexico, and adjacent portions of California, Colorado, Ne ...

,

and along with increasing immigration from Germany,

the Catholic population in the United States had grown to 1.6 million (or approximately 7 percent of the total population of approximately 23.2 million).

Despite the small increase in Catholic-Protestant intermarriage following the American Revolutionary War,

Catholic-Protestant intermarriage remained uncommon in the United States in the 19th century.

Historians have characterized the etymology of the term "

Scotch-Irish" as obscure,

and the term itself as misleading and confusing to the extent that even its usage by authors in historic works of literature about the Scotch-Irish (such as ''The Mind of the South'' by

W. J. Cash

Wilbur Joseph Cash (May 2, 1900 – July 1, 1941) was an American journalist known for writing ''The Mind of the South'' (1941), his controversial interpretation of the history of the American South.

Biography Early life

Cash was born and grew u ...

) is often incorrect.

Historians

David Hackett Fischer

David Hackett Fischer (born December 2, 1935) is University Professor of History Emeritus at Brandeis University. Fischer's major works have covered topics ranging from large macroeconomic and cultural trends (''Albion's Seed,'' ''The Great Wave ( ...

and James G. Leyburn note that usage of the term is unique to

North American English

North American English (NAmE, NAE) is the most generalized variety of the English language as spoken in the United States and Canada. Because of their related histories and cultures, plus the similarities between the pronunciations (accents), v ...

and it is rarely used by British historians, or in Scotland or Ireland.

The first recorded usage of the term was by

Elizabeth I of England

Elizabeth I (7 September 153324 March 1603) was List of English monarchs, Queen of England and List of Irish monarchs, Ireland from 17 November 1558 until her death in 1603. Elizabeth was the last of the five House of Tudor monarchs and is ...

in 1573 in reference to

Gaelic-speaking Scottish Highlanders

The Highlands ( sco, the Hielands; gd, a’ Ghàidhealtachd , 'the place of the Gaels') is a historical region of Scotland. Culturally, the Highlands and the Lowlands diverged from the Late Middle Ages into the modern period, when Lowland Sc ...

who crossed the

Irish Sea

The Irish Sea or , gv, Y Keayn Yernagh, sco, Erse Sie, gd, Muir Èireann , Ulster-Scots: ''Airish Sea'', cy, Môr Iwerddon . is an extensive body of water that separates the islands of Ireland and Great Britain. It is linked to the Ce ...

and intermarried with the

Irish Catholic

Irish Catholics are an ethnoreligious group native to Ireland whose members are both Catholic and Irish. They have a large diaspora, which includes over 36 million American citizens and over 14 million British citizens (a quarter of the British ...

natives of Ireland.

While Protestant immigrants from Ireland in the 18th century were more commonly identified as "Anglo-Irish," and while some preferred to self-identify as "Anglo-Irish,"

usage of "Scotch-Irish" in reference to

Ulster Scots who immigrated to the United States in the 18th century likely became common among

Episcopalians

Anglicanism is a Western Christian tradition that has developed from the practices, liturgy, and identity of the Church of England following the English Reformation, in the context of the Protestant Reformation in Europe. It is one of th ...

and

Quakers

Quakers are people who belong to a historically Protestant Christian set of denominations known formally as the Religious Society of Friends. Members of these movements ("theFriends") are generally united by a belief in each human's abil ...

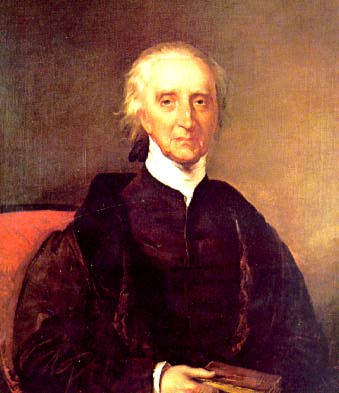

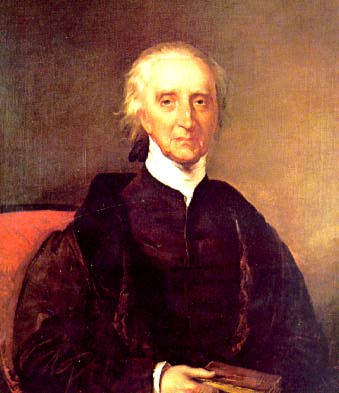

in Pennsylvania, and records show that usage of the term with this meaning was made as early as 1757 by the Anglo-Irish philosopher

Edmund Burke

Edmund Burke (; 12 January NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS">New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style">NS/nowiki>_1729_–_9_July_1797)_was_an_ NS.html"_;"title="New_Style.html"_;"title="/nowiki>New_Style"> ...

.

However, multiple historians have noted that from the time of the

American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

until 1850, the term largely fell out of usage, because most Ulster Protestants self-identified as "Irish" until large waves of immigration by Irish Catholics both during and after the

1840s Great Famine in Ireland led those Ulster Protestants in America who lived in proximity to the new immigrants to change their self-identification from "Irish" to "Scotch-Irish," while those Ulster Protestants who did not live in proximity to Irish Catholics continued to self-identify as "Irish," or as time went on, to start self-identifying as being of "

American ancestry

American ancestry refers to people in the United States who self-identify their ancestral origin or descent as "American," rather than the more common officially recognized racial and ethnic groups that make up the bulk of the American peop ...

."

While those historians note that renewed usage of "Scotch-Irish" after 1850 was motivated by

anti-Catholic prejudices among Ulster Protestants,

considering the historically low rates of intermarriage between Protestants and Catholics in both Ireland and the United States, as well as the relative frequency of

interethnic and

interdenominational marriage

Interdenominational marriage, sometimes called an inter-sect marriage or ecumenical marriage, is marriage between spouses professing a different denomination of same religion.

Interdenominational marriages are distinguished from interfaith ma ...

amongst Protestants in Ulster, and the fact that not all Protestant migrants from Ireland historically were Ulster Scots,

James G. Leyburn argued for retaining its usage for reasons of utility and preciseness,

while historian Wayland F. Dunaway also argued for retention for historical precedent and

linguistic description

In the study of language, description or descriptive linguistics is the work of objectively analyzing and describing how language is actually used (or how it was used in the past) by a speech community. François & Ponsonnet (2013).

All acad ...

.

During the colonial period, Scots-Irish settled in the

southern Appalachia

Appalachia () is a cultural region in the Eastern United States that stretches from the Southern Tier of New York State to northern Alabama and Georgia. While the Appalachian Mountains stretch from Belle Isle in Newfoundland and Labrador, Ca ...

n backcountry and in the

Carolina Piedmont

it, Piemontese

, population_note =

, population_blank1_title =

, population_blank1 =

, demographics_type1 =

, demographics1_footnotes =

, demographics1_title1 =

, demographics1_info1 =

, demographics1_title2 ...

. They became the primary cultural group in these areas, and their descendants were in the vanguard of westward movement through

Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography and climate of the Commonwealth ar ...

into

Tennessee

Tennessee ( , ), officially the State of Tennessee, is a landlocked state in the Southeastern region of the United States. Tennessee is the 36th-largest by area and the 15th-most populous of the 50 states. It is bordered by Kentucky to th ...

and

Kentucky

Kentucky ( , ), officially the Commonwealth of Kentucky, is a state in the Southeastern region of the United States and one of the states of the Upper South. It borders Illinois, Indiana, and Ohio to the north; West Virginia and Virginia to ...

, and thence into

Arkansas

Arkansas ( ) is a landlocked state in the South Central United States. It is bordered by Missouri to the north, Tennessee and Mississippi to the east, Louisiana to the south, and Texas and Oklahoma to the west. Its name is from the Osage ...

,

Missouri

Missouri is a U.S. state, state in the Midwestern United States, Midwestern region of the United States. Ranking List of U.S. states and territories by area, 21st in land area, it is bordered by eight states (tied for the most with Tennessee ...

and

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

. By the 19th century, through intermarriage with settlers of English and German ancestry, the descendants of the Scots-Irish lost their identification with Ireland. "This generation of pioneers...was a generation of Americans, not of Englishmen or Germans or Scots-Irish." The two groups had little initial interaction in America, as the 18th-century Ulster immigrants were predominantly

Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and had become settled largely in upland regions of the American interior, while the huge wave of 19th-century Catholic immigrant families settled primarily in the Northeast and Midwest port cities such as

Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

,

Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

,

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

,

Buffalo, or

Chicago

(''City in a Garden''); I Will

, image_map =

, map_caption = Interactive Map of Chicago

, coordinates =

, coordinates_footnotes =

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name ...

. However, beginning in the early 19th century, many Irish migrated individually to the interior for work on large-scale infrastructure projects such as

canals

Canals or artificial waterways are waterways or river engineering, engineered channel (geography), channels built for drainage management (e.g. flood control and irrigation) or for conveyancing water transport watercraft, vehicles (e.g. ...

and, later in the century,

railroads

Rail transport (also known as train transport) is a means of transport that transfers passengers and goods on wheeled vehicles running on rails, which are incorporated in Track (rail transport), tracks. In contrast to road transport, where the ...

.

The Scots-Irish settled mainly in the colonial "back country" of the

Appalachian Mountain

The Appalachian Mountains, often called the Appalachians, (french: Appalaches), are a system of mountains in eastern to northeastern North America. The Appalachians first formed roughly 480 million years ago during the Ordovician Period. They ...

region, and became the prominent ethnic strain in the culture that developed there. The descendants of Scots-Irish settlers had a great influence on the later culture of the

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

in particular and the culture of the United States in general through such contributions as

American folk music

The term American folk music encompasses numerous music genres, variously known as ''traditional music'', ''traditional folk music'', ''contemporary folk music'', ''vernacular music,'' or ''roots music''. Many traditional songs have been sung ...

,

country and western

A country is a distinct part of the world, such as a state, nation, or other political entity. It may be a sovereign state or make up one part of a larger state. For example, the country of Japan is an independent, sovereign state, while the ...

music, and

stock car racing

Stock car racing is a form of automobile racing run on oval tracks and road courses measuring approximately . It originally used production-model cars, hence the name "stock car", but is now run using cars specifically built for racing. It ori ...

, which became popular throughout the country in the late 20th century.

Irish immigrants of this period participated in significant numbers in the

American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolut ...

, leading one British Army officer to testify at the

House of Commons

The House of Commons is the name for the elected lower house of the bicameral parliaments of the United Kingdom and Canada. In both of these countries, the Commons holds much more legislative power than the nominally upper house of parliament. ...

that "half the rebels (referring to soldiers in the Continental Army) were from Ireland." Irish Americans signed the foundational documents of the United States—the

Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

and the

Constitution

A constitution is the aggregate of fundamental principles or established precedents that constitute the legal basis of a polity, organisation or other type of Legal entity, entity and commonly determine how that entity is to be governed.

When ...

—and, beginning with

Andrew Jackson

Andrew Jackson (March 15, 1767 – June 8, 1845) was an American lawyer, planter, general, and statesman who served as the seventh president of the United States from 1829 to 1837. Before being elected to the presidency, he gained fame as ...

, served as president.

1790 population of Irish origin by state

Irish Catholics in the South

In 1820 Irish-born

John England became the first Catholic bishop in the mainly Protestant city of

Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

. During the 1820s and 1830s, Bishop England defended the Catholic minority against Protestant prejudices. In 1831 and 1835, he established free schools for free

African American

African Americans (also referred to as Black Americans and Afro-Americans) are an ethnic group consisting of Americans with partial or total ancestry from sub-Saharan Africa. The term "African American" generally denotes descendants of ens ...

children. Inflamed by the propaganda of the

American Anti-Slavery Society

The American Anti-Slavery Society (AASS; 1833–1870) was an abolitionist society founded by William Lloyd Garrison and Arthur Tappan. Frederick Douglass, an escaped slave, had become a prominent abolitionist and was a key leader of this society ...

, a mob raided the Charleston post office in 1835 and the next day turned its attention to England's school. England led Charleston's "Irish Volunteers" to defend the school. Soon after this, however, all schools for "free blacks" were closed in Charleston, and England acquiesced.

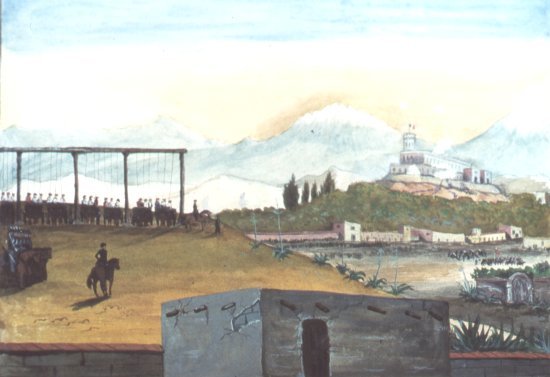

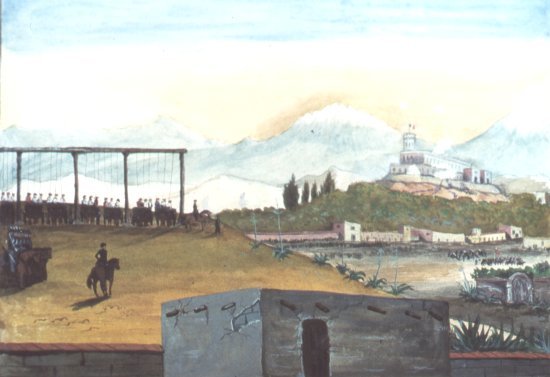

Two pairs of Irish empresarios founded colonies in coastal

Texas

Texas (, ; Spanish language, Spanish: ''Texas'', ''Tejas'') is a state in the South Central United States, South Central region of the United States. At 268,596 square miles (695,662 km2), and with more than 29.1 million residents in 2 ...

in 1828. John McMullen and James McGloin honored the Irish saint when they established the San Patricio Colony south of San Antonio; James Power and James Hewetson contracted to create the Refugio Colony on the Gulf Coast. The two colonies were settled mainly by Irish, but also by Mexicans and other nationalities. At least 87 Irish-surnamed individuals settled in the Peters Colony, which included much of present-day north-central Texas, in the 1840s. The Irish participated in all phases of Texas' war of independence against Mexico. Among those who died defending the Alamo in March 1836 were 12 who were Irish-born, while an additional 14 bore Irish surnames. About 100 Irish-born soldiers participated in the Battle of San Jacinto – about one-seventh of the total force of

Texians

Texians were Anglo-American residents of Mexican Texas and, later, the Republic of Texas.

Today, the term is used to identify early settlers of Texas, especially those who supported the Texas Revolution. Mexican settlers of that era are refer ...

in that conflict.

The Irish Catholics concentrated in a few medium-sized cities, where they were highly visible, especially in

Charleston,

Savannah

A savanna or savannah is a mixed woodland-grassland (i.e. grassy woodland) ecosystem characterised by the trees being sufficiently widely spaced so that the Canopy (forest), canopy does not close. The open canopy allows sufficient light to rea ...

and

.

They often became precinct leaders in the

Democratic Party Organizations, opposed

abolition of slavery

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The British ...

, and generally favored preserving the

Union

Union commonly refers to:

* Trade union, an organization of workers

* Union (set theory), in mathematics, a fundamental operation on sets

Union may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment

Music

* Union (band), an American rock group

** ''Un ...

in 1860, when they voted for

Stephen Douglas

Stephen Arnold Douglas (April 23, 1813 – June 3, 1861) was an American politician and lawyer from Illinois. A senator, he was one of two nominees of the badly split Democratic Party for president in the 1860 presidential election, which was ...

.

After secession in 1861, the Irish Catholic community supported the

Confederate States of America

The Confederate States of America (CSA), commonly referred to as the Confederate States or the Confederacy was an unrecognized breakaway republic in the Southern United States that existed from February 8, 1861, to May 9, 1865. The Confeder ...

and 20,000 Irish Catholics served in the

Confederate States Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

. Gleason says:

Irish nationalist

John Mitchel

John Mitchel ( ga, Seán Mistéal; 3 November 1815 – 20 March 1875) was an Irish nationalist activist, author, and political journalist. In the Great Famine (Ireland), Famine years of the 1840s he was a leading writer for The Nation (Irish n ...

lived in Tennessee and Virginia during his exile from Ireland and was one of the

Southern United States

The Southern United States (sometimes Dixie, also referred to as the Southern States, the American South, the Southland, or simply the South) is a geographic and cultural region of the United States of America. It is between the Atlantic Ocean ...

' most outspoken supporters during the American Civil War through his newspapers the ''Southern Citizen'' and the ''Richmond Enquirer''.

Although most began as unskilled laborers, Irish Catholics in the South achieved average or above average economic status by 1900. David T. Gleeson emphasizes how well they were accepted by society:

Mid-19th century and later

Before the 1800s, Irish immigrants to North America often moved to the countryside. Some worked in the fur trade, trapping and exploring, but most settled in rural farms and villages. They cleared the land of trees, built homes, and planted fields. Many others worked in coastal areas as fishers, on ships, and as dockworkers. In the 1800s, Irish immigrants in the United States tended to stay in the large cities where they landed.

From 1820 to 1860, 1,956,557 Irish arrived, 75% of these after the

Great Irish Famine

The Great Famine ( ga, an Gorta Mór ), also known within Ireland as the Great Hunger or simply the Famine and outside Ireland as the Irish Potato Famine, was a period of starvation and disease in Ireland from 1845 to 1852 that constituted a ...

(or ''The Great Hunger'', ga, An Gorta Mór) of 1845–1852, struck.

According to a 2019 study, "the sons of farmers and illiterate men were more likely to emigrate than their literate and skilled counterparts. Emigration rates were highest in poorer farming communities with stronger migrant networks."

Of the total

Irish immigrants

The Irish diaspora ( ga, Diaspóra na nGael) refers to ethnic Irish people and their descendants who live outside the island of Ireland.

The phenomenon of migration from Ireland is recorded since the Early Middle Ages,Flechner and Meeder, The ...

to the U.S. from 1820 to 1860, many died crossing the ocean due to disease and dismal conditions of what became known as