Ion Luca Caragiale on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

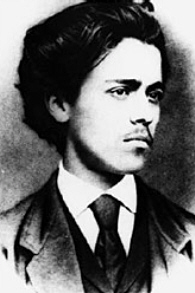

Ion Luca Caragiale (; commonly referred to as I. L. Caragiale; According to his birth certificate, published and discussed by Constantin Popescu-Cadem in ''Manuscriptum'', Vol. VIII, Nr. 2, 1977, pp. 179-184 – 9 June 1912) was a

"Grecii, mai interesaţi de opera lui I.L.Caragiale decit conaţionalii săi"

, in '' Evenimentul'', 8 June 2002 Lucian Nastasă

''Genealogia între ştiinţă, mitologie şi monomanie''

p. 18, at the

"I.L. Caragiale, fiul unui emigrant din Cefallonia (III)"

in '' Evenimentul'', 25 May 2002. and, according to historian Lucian Nastasă, some of her relatives were Hungarian members of the Tabay family. The couple also had a daughter, named Lenci. Ion Luca's uncles, Costache and Iorgu Caragiale, managed theater troupes and were very influential figures in the development of early Romanian theatre — in Wallachia and

"Caragiale: 'ai avesi, tomnilor, cu numele meu?'"

in ''

"Romania and the Balkans. From Geocultural Bovarism to Ethnic Ontology"

in ''Tr@nsit online'', Nr. 21/2002, Nevertheless, as literary critic

Nevertheless, as literary critic

''Introduceri la ediţia critică I.L. Caragiale, opere''

(wikisource) (elsewhere, he referred to the writer as "a lazy southerner, fitted with definitely supranormal intelligence and imagination").

Artiști și idei literare române: Publicul și arta lui Caragiale

' (wikisource) In his main work on the history of Romanian literature,

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească: Spiritul critic în Muntenia – Critica socială extremă: Caragiale''

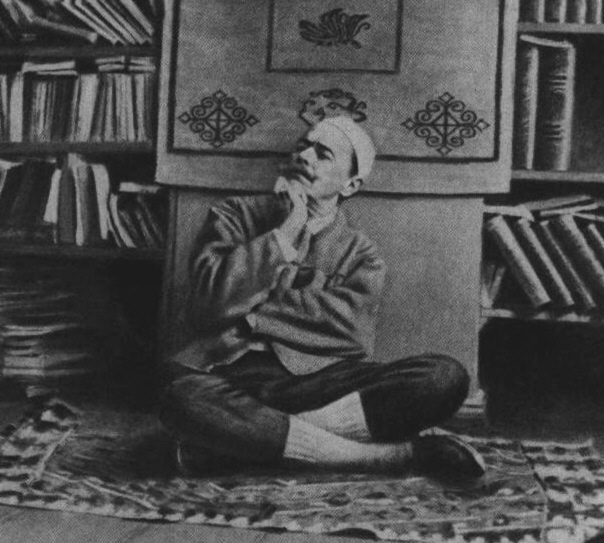

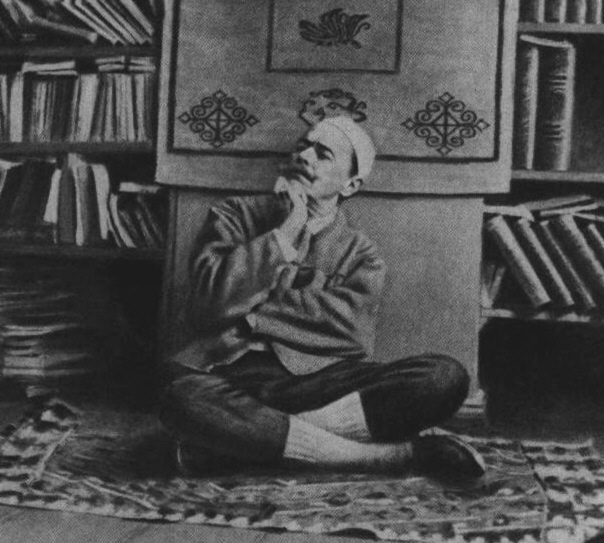

(wikisource) On one occasion, Caragiale mentioned that his paternal grandfather was "a Greek cook". In several contexts, he referred to his roots as being in the island of Hydra. In one of his photographs, he posed in Oriental costume and sitting cross-legged, which was interpreted by Vianu as an additional reference to his Balkan background. Two of his biographers, Zarifopol and

, in ''

Born in the village of Haimanale, Prahova County (the present-day I. L. Caragiale

Born in the village of Haimanale, Prahova County (the present-day I. L. Caragiale

Ion Luca made his literary debut in 1873, at the age of 21, with poems and humorous chronicles printed in G. Dem. Teodorescu's liberal-inspired satirical magazine, ''Ghimpele''. He published relatively few articles under various

Ion Luca made his literary debut in 1873, at the age of 21, with poems and humorous chronicles printed in G. Dem. Teodorescu's liberal-inspired satirical magazine, ''Ghimpele''. He published relatively few articles under various

The young journalist began drifting away from National Liberal politics soon after 1876, when the group came to power with

The young journalist began drifting away from National Liberal politics soon after 1876, when the group came to power with

Just one year after, Caragiale was moved back to Wallachia, becoming inspector general in Argeș and Vâlcea. He was ultimately stripped of this position in 1884, and found himself on the verge of

Just one year after, Caragiale was moved back to Wallachia, becoming inspector general in Argeș and Vâlcea. He was ultimately stripped of this position in 1884, and found himself on the verge of

During the same year, Caragiale's ''D-ale carnavalului'', a lighter satire of suburban morals and amorous misadventures, was received with

During the same year, Caragiale's ''D-ale carnavalului'', a lighter satire of suburban morals and amorous misadventures, was received with

''Asupra esteticii metafizice şi ştiinţifice''

(wikisource) Dobrogeanu-Gherea argued in favor of Caragiale's work, but considered ''D-ale carnavalului'' to be his weakest play.

The appointment caused some controversy at the time: Ion Luca Caragiale, unlike all his predecessors (the incumbent C.I. Stăncescu included), was both a professional in the field and a person of modest origins. As the National Liberals intensified their campaign against him, the dramatist drafted an

The appointment caused some controversy at the time: Ion Luca Caragiale, unlike all his predecessors (the incumbent C.I. Stăncescu included), was both a professional in the field and a person of modest origins. As the National Liberals intensified their campaign against him, the dramatist drafted an

During the controversy, Caragiale published two memoirs of Eminescu—the poet had died in June 1889. One of them was titled ''În Nirvana'' ("Into

During the controversy, Caragiale published two memoirs of Eminescu—the poet had died in June 1889. One of them was titled ''În Nirvana'' ("Into

In 1895, the writer followed the Radical group into its unusual merger with the Conservative Party. This came at a time of unified opposition, when the ''Junimists'' themselves returned to their group of origin. Caragiale came to identify with the policies endorsed by a new group of Conservative leaders, Nicolae Filipescu and Alexandru Lahovari among them. He was upset when Lahovari died not too long after, and authored his obituary.

Caragiale also became a collaborator on Filipescu's journal '' Epoca'' and editor of its literary supplement. A chronicle he contributed at the time discussed the philosophical writings of Dobrogeanu-Gherea: while sympathetic to his conclusions, Caragiale made a clear statement that he was not interested in the socialist doctrine or any other ideology ("Any idea, opinion or system is absolutely irrelevant to me, in the most absolute sense").Vianu, Vol. II, pg. 186 He also published an article criticizing Dimitrie Sturdza; its title, ''O lichea'' (roughly: "A Scoundrel"), was reluctantly accepted by ''Epoca'', and only after Caragiale claimed that it reflected the original meaning of the word ''lichea'' ("stain"), explaining that it referred to Sturdza's unusual persistence in politics.

When answering to one of ''Epocas inquiries, he showed that he had yet again come to reevaluate ''Junimea'', and found it to be an essential institution in Romanian culture. Nevertheless, he was distancing himself from the purest ''Junimist'' tenets, and took a favorable view of Romanticism, Romantic writers whom the society had criticized or ridiculed — among these, he indicated his personal rival

In 1895, the writer followed the Radical group into its unusual merger with the Conservative Party. This came at a time of unified opposition, when the ''Junimists'' themselves returned to their group of origin. Caragiale came to identify with the policies endorsed by a new group of Conservative leaders, Nicolae Filipescu and Alexandru Lahovari among them. He was upset when Lahovari died not too long after, and authored his obituary.

Caragiale also became a collaborator on Filipescu's journal '' Epoca'' and editor of its literary supplement. A chronicle he contributed at the time discussed the philosophical writings of Dobrogeanu-Gherea: while sympathetic to his conclusions, Caragiale made a clear statement that he was not interested in the socialist doctrine or any other ideology ("Any idea, opinion or system is absolutely irrelevant to me, in the most absolute sense").Vianu, Vol. II, pg. 186 He also published an article criticizing Dimitrie Sturdza; its title, ''O lichea'' (roughly: "A Scoundrel"), was reluctantly accepted by ''Epoca'', and only after Caragiale claimed that it reflected the original meaning of the word ''lichea'' ("stain"), explaining that it referred to Sturdza's unusual persistence in politics.

When answering to one of ''Epocas inquiries, he showed that he had yet again come to reevaluate ''Junimea'', and found it to be an essential institution in Romanian culture. Nevertheless, he was distancing himself from the purest ''Junimist'' tenets, and took a favorable view of Romanticism, Romantic writers whom the society had criticized or ridiculed — among these, he indicated his personal rival

''Amintiri literare (Ion Luca Caragiale)''

(wikisource)

Soon after, Caragiale became involved in a major literary scandal. Constantin Al. Ionescu-Caion, a journalist and student whom

Soon after, Caragiale became involved in a major literary scandal. Constantin Al. Ionescu-Caion, a journalist and student whom

"Casele lui I.L. Caragiale de la Berlin"

, in ''

Beginning in 1909, Caragiale resumed his contributions to ''Universul''. The same year, his

Beginning in 1909, Caragiale resumed his contributions to ''Universul''. The same year, his  Caragiale also contributed to the Arad, Romania, Arad-based journal ''Românul'', becoming friends with other Romanian activists—Aurel Popovici, Alexandru Vaida-Voevod and Vasile Goldiș. His articles expressed support for the National Romanian Party, calling for its adversaries at ''Tribuna (Romania), Tribuna'' to abandon their dissident politics. In August 1911, he was present in Blaj, where the cultural association Asociația Transilvană pentru Literatura Română și Cultura Poporului Român, ASTRA was celebrating its 50th year. Caragiale also witnessed one of the first aviation flights, that of the Romanian Transylvanian pioneer Aurel Vlaicu. In January 1912, as he turned 60, Caragiale declined taking part in the formal celebration organized by Emil Gârleanu's Romanian Writers' Society. Caragiale had previously rejected

Caragiale also contributed to the Arad, Romania, Arad-based journal ''Românul'', becoming friends with other Romanian activists—Aurel Popovici, Alexandru Vaida-Voevod and Vasile Goldiș. His articles expressed support for the National Romanian Party, calling for its adversaries at ''Tribuna (Romania), Tribuna'' to abandon their dissident politics. In August 1911, he was present in Blaj, where the cultural association Asociația Transilvană pentru Literatura Română și Cultura Poporului Român, ASTRA was celebrating its 50th year. Caragiale also witnessed one of the first aviation flights, that of the Romanian Transylvanian pioneer Aurel Vlaicu. In January 1912, as he turned 60, Caragiale declined taking part in the formal celebration organized by Emil Gârleanu's Romanian Writers' Society. Caragiale had previously rejected

His interest in first-hand investigation of the human nature was accompanied, at least after he reached maturity, by a distaste for generous and Universalism, universalist theories. Caragiale viewed their impact on Romanian society with a critical eye. Like ''

His interest in first-hand investigation of the human nature was accompanied, at least after he reached maturity, by a distaste for generous and Universalism, universalist theories. Caragiale viewed their impact on Romanian society with a critical eye. Like ''

The writer had an unprecedented familiarity with the social environments, traits, opinions, manners of speech, means of expression and lifestyle choices of his day — from the rural atmosphere of his early childhood, going through his vast experience as a journalist, to the high spheres of politics (National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal as well as Conservative Party (Romania, 1880–1918), Conservative, ''Junimist'' as well as socialist). An incessant traveler, Caragiale carefully investigated everyday life in most areas of the Romanian Old Kingdom and Transylvania. He was an unusually sociable man: in one of his letters from

The writer had an unprecedented familiarity with the social environments, traits, opinions, manners of speech, means of expression and lifestyle choices of his day — from the rural atmosphere of his early childhood, going through his vast experience as a journalist, to the high spheres of politics (National Liberal Party (Romania, 1875), National Liberal as well as Conservative Party (Romania, 1880–1918), Conservative, ''Junimist'' as well as socialist). An incessant traveler, Caragiale carefully investigated everyday life in most areas of the Romanian Old Kingdom and Transylvania. He was an unusually sociable man: in one of his letters from

Confessing at some point that "the world was my school", Caragiale dissimulated his background and critical eye as a means to blend into each environment he encountered, and even adopted the manners and speech patterns he later recorded in his literary work. He thus encouraged familiarity, allowing people to reveal their histories, motivations, and culture. Vianu recounted: "The man was a consummate actor and a ''Deadpan, pince-sans-rire'', an ironist ..to the point where his partners of dialog were never sure if they were spoken to 'seriously' .."Vianu, Vol. II, p. 196 In one of his pieces from 1899, he welcomed the famous actors Eleonora Duse and Jean Mounet-Sully to Bucharest, imitating the exaggerated style of other theater chroniclers—the article ended with Caragiale confessing that he had not actually seen the two perform. In one other instance, as a means to comment on

Confessing at some point that "the world was my school", Caragiale dissimulated his background and critical eye as a means to blend into each environment he encountered, and even adopted the manners and speech patterns he later recorded in his literary work. He thus encouraged familiarity, allowing people to reveal their histories, motivations, and culture. Vianu recounted: "The man was a consummate actor and a ''Deadpan, pince-sans-rire'', an ironist ..to the point where his partners of dialog were never sure if they were spoken to 'seriously' .."Vianu, Vol. II, p. 196 In one of his pieces from 1899, he welcomed the famous actors Eleonora Duse and Jean Mounet-Sully to Bucharest, imitating the exaggerated style of other theater chroniclers—the article ended with Caragiale confessing that he had not actually seen the two perform. In one other instance, as a means to comment on

Aside from the many authors whose works he quoted, translated or parodied, Ion Luca Caragiale built on a vast literary legacy. According to literary historian Ștefan Cazimir: "No writer ever had as large a number of precursors [as Caragiale], just as no other artistic synthesis was ever more organic and more spontaneous."

A man of the theater first and foremost, Caragiale was well-acquainted with the work of his predecessors, from

Aside from the many authors whose works he quoted, translated or parodied, Ion Luca Caragiale built on a vast literary legacy. According to literary historian Ștefan Cazimir: "No writer ever had as large a number of precursors [as Caragiale], just as no other artistic synthesis was ever more organic and more spontaneous."

A man of the theater first and foremost, Caragiale was well-acquainted with the work of his predecessors, from

The writer was elected to the

The writer was elected to the

at theThe Memorial House "Ion Luca Caragiale"

, a

''Museums of Dâmbovița''

. Retrieved 25 September 2007. Memorial plaques have also been set up in

''Concert de deschidere''LiterNet

e-book, 2004. *Vicu Mîndra, in I.L. Caragiale, ''Nuvele şi povestiri'', Editura Tineretului, Bucharest, 1966. : **"Prefaţă", p. 5–33 **"Aprecieri critice", p. 267–271 **"Tablou biobibliografic", p. 272–275 *Z. Ornea, ''Junimea şi junimismul'', Vol. II, Editura Minerva, Bucharest, 1998. *

''Studii eminesciene''

Museum of Romanian Literature, Bucharest, 2001. *

Ion Luca Caragiale

(official Facebook page)

(official site)

(official site)

* {{DEFAULTSORT:Caragiale, Ion Luca Ion Luca Caragiale, 1852 births 1912 deaths Neoclassical writers Realism (art movement) Junimists 19th-century Romanian dramatists and playwrights 20th-century Romanian dramatists and playwrights Male dramatists and playwrights 19th-century short story writers 20th-century short story writers Romanian male short story writers Romanian short story writers Romanian humorists Romanian letter writers Romanian memoirists Romanian fantasy writers Romanian collectors of fairy tales 19th-century Romanian poets 20th-century Romanian poets Romanian male poets Romanian epigrammatists Romanian columnists 20th-century essayists Romanian magazine editors Romanian magazine founders Romanian newspaper editors Romanian essayists Male essayists Romanian translators French–Romanian translators Italian–Romanian translators Translators of Edgar Allan Poe People from Dâmbovița County Romanian people of Greek descent Members of the Romanian Orthodox Church Conservative-Democratic Party politicians 19th-century Romanian male actors Romanian male stage actors Romanian theatre critics Chairpersons of the National Theatre Bucharest Romanian restaurateurs Romanian civil servants Romanian expatriates in Germany Burials at Bellu Cemetery Members of the Romanian Academy elected posthumously

Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central Europe, Central, Eastern Europe, Eastern, and Southeast Europe, Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine to the north, Hungary to the west, S ...

n playwright, short story writer, poet, theater manager, political commentator and journalist. Leaving behind an important cultural legacy, he is considered one of the greatest playwrights in Romanian language

Romanian (obsolete spellings: Rumanian or Roumanian; autonym: ''limba română'' , or ''românește'', ) is the official and main language of Romania and the Moldova, Republic of Moldova. As a minority language it is spoken by stable communi ...

and literature

Literature is any collection of written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially prose fiction, drama, and poetry. In recent centuries, the definition has expanded to include ...

, as well as one of its most important writers and a leading representative of local humour. Alongside Mihai Eminescu

Mihai Eminescu (; born Mihail Eminovici; 15 January 1850 – 15 June 1889) was a Romanian Romantic poet from Moldavia, novelist, and journalist, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet. Eminescu was an active membe ...

, Ioan Slavici

Ioan Slavici (; 18 January 1848 – 17 August 1925) was a Romanians, Romanian writer and journalist from Hungary, later from Romania.

He made his debut in ''Convorbiri literare'' ("Literary Conversations") (1871), with the comedy ''Fata de biră ...

and Ion Creangă, he is seen as one of the main representatives of ''Junimea

''Junimea'' was a Romanian literary society founded in Iași in 1863, through the initiative of several foreign-educated personalities led by Titu Maiorescu, Petre P. Carp, Vasile Pogor, Theodor Rosetti and Iacob Negruzzi. The foremost personali ...

'', an influential literary society with which he nonetheless parted during the second half of his life. His work, spanning four decades, covers the ground between Neoclassicism

Neoclassicism (also spelled Neo-classicism) was a Western cultural movement in the decorative and visual arts, literature, theatre, music, and architecture that drew inspiration from the art and culture of classical antiquity. Neoclassicism was ...

, Realism

Realism, Realistic, or Realists may refer to:

In the arts

*Realism (arts), the general attempt to depict subjects truthfully in different forms of the arts

Arts movements related to realism include:

*Classical Realism

*Literary realism, a move ...

, and Naturalism, building on an original synthesis of foreign and local influences.

Although few in number, Caragiale's plays constitute the most accomplished expression of Romanian theatre, as well as being important venues for criticism of late-19th-century Romanian society. They include the comedies

Comedy is a genre of fiction that consists of discourses or works intended to be humorous or amusing by inducing laughter, especially in theatre, film, stand-up comedy, television, radio, books, or any other entertainment medium. The term origin ...

''O noapte furtunoasă

O, or o, is the fifteenth letter and the fourth vowel letter in the Latin alphabet, used in the modern English alphabet, the alphabets of other western European languages and others worldwide. Its name in English is ''o'' (pronounced ), pl ...

'', ''Conu Leonida față cu reacțiunea

Coni ( tly, Çoni) is a village and municipality in the Lerik Rayon of Azerbaijan

Azerbaijan (, ; az, Azərbaycan ), officially the Republic of Azerbaijan, , also sometimes officially called the Azerbaijan Republic is a transcontinental co ...

'', ''O scrisoare pierdută

''O scrisoare pierdută'' (Romanian for "A Lost Letter") is a play by Ion Luca Caragiale. It premiered in 1884, and arguably represents the high point of his career.Vianu, Vol. II, p.180

It was adapted into a 1953 film ''A Lost Letter''.

Characte ...

'', and the tragedy

Tragedy (from the grc-gre, τραγῳδία, ''tragōidia'', ''tragōidia'') is a genre of drama based on human suffering and, mainly, the terrible or sorrowful events that befall a main character. Traditionally, the intention of tragedy ...

'' Năpasta''. In addition to these, Caragiale authored a large number of essays, articles, short stories, novella

A novella is a narrative prose fiction whose length is shorter than most novels, but longer than most short stories. The English word ''novella'' derives from the Italian ''novella'' meaning a short story related to true (or apparently so) facts ...

s and sketch stories

A sketch story, literary sketch or simply sketch, is a piece of writing that is generally shorter than a short story, and contains very little, if any, plot. The genre was invented after the 16th century in England, as a result of increasing public ...

, as well as occasional works of poetry and autobiographical texts such as '' Din carnetul unui vechi sufleur''. In many cases, his creations were first published in one of several magazines he edited — '' Claponul'', '' Vatra'', and '' Epoca''. In some of his later fiction writings, including ''La hanul lui Mânjoală

LA most frequently refers to Los Angeles, the second largest city in the United States.

La, LA, or L.A. may also refer to:

Arts and entertainment Music

* La (musical note), or A, the sixth note

* "L.A.", a song by Elliott Smith on ''Figur ...

'', '' Kir Ianulea'', '' Abu-Hasan,'' '' Pastramă trufanda'' and ''Calul dracului Calul may refer to the following rivers in Romania:

*Calu, a tributary of the Bicaz

Bicaz ( hu, Békás) is a town in Neamț County, Western Moldavia, Romania situated in the eastern Carpathian Mountains near the confluence of the Bicaz and B ...

'', Caragiale adopted the fantasy

Fantasy is a genre of speculative fiction involving Magic (supernatural), magical elements, typically set in a fictional universe and sometimes inspired by mythology and folklore. Its roots are in oral traditions, which then became fantasy ...

genre or turned to historical fiction

Historical fiction is a literary genre in which the plot takes place in a setting related to the past events, but is fictional. Although the term is commonly used as a synonym for historical fiction literature, it can also be applied to other ty ...

.

Ion Luca Caragiale was interested in the politics of the Romanian Kingdom

The Kingdom of Romania ( ro, Regatul României) was a constitutional monarchy that existed in Romania from 13 March ( O.S.) / 25 March 1881 with the crowning of prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen as King Carol I (thus beginning the Romanian ...

, and oscillated between the liberal current and conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

. Most of his satirical

Satire is a genre of the visual, literary, and performing arts, usually in the form of fiction and less frequently non-fiction, in which vices, follies, abuses, and shortcomings are held up to ridicule, often with the intent of shaming or e ...

works target the liberal republicans and the National Liberals, evidencing both his respect for their rivals at ''Junimea'' and his connections with the literary critic Titu Maiorescu

Titu Liviu Maiorescu (; 15 February 1840 – 18 June 1917) was a Romanian literary critic and politician, founder of the ''Junimea'' Society. As a literary critic, he was instrumental in the development of Romanian culture in the second half of ...

. He came to clash with National Liberal leaders such as Dimitrie Sturdza

Dimitrie Sturdza (, in full Dimitrie Alexandru Sturdza-Miclăușanu; 10 March 183321 October 1914) was a Romanian statesman and author of the late 19th century, and president of the Romanian Academy between 1882 and 1884.

Biography

Born in Iași ...

and Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu

Bogdan Petriceicu Hasdeu ( 26 February 1838 – ) was a Romanian writer and philologist, who pioneered many branches of Romanian philology and history.

Life

He was born Tadeu Hâjdeu in Cristineștii Hotinului (now Kerstentsi in Chernivtsi ...

, and was a lifelong adversary of the Symbolist

Symbolism was a late 19th-century art movement of French and Belgian origin in poetry and other arts seeking to represent absolute truths symbolically through language and metaphorical images, mainly as a reaction against naturalism and realis ...

poet Alexandru Macedonski

Alexandru Macedonski (; also rendered as Al. A. Macedonski, Macedonschi or Macedonsky; 14 March 1854 – 24 November 1920) was a Romanian poet, novelist, dramatist and literary critic, known especially for having promoted French Symbolism in h ...

. As a result of these conflicts, the most influential of Caragiale's critics barred his access to the cultural establishment for several decades. During the 1890s, Caragiale rallied with the radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

movement of George Panu, before associating with the Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

. After having decided to settle in Berlin

Berlin ( , ) is the capital and largest city of Germany by both area and population. Its 3.7 million inhabitants make it the European Union's most populous city, according to population within city limits. One of Germany's sixteen constitue ...

, he came to voice strong criticism for Romanian politicians of all colours in the wake of the 1907 Romanian Peasants' Revolt, and ultimately joined the Conservative-Democratic Party

The Conservative-Democratic Party (, PCD) was a political party in Romania. Over the years, it had the following names: the Democratic Party, the Nationalist Conservative Party, or the Unionist Conservative Party.

The Conservative-Democratic Part ...

of Tache Ionescu.

He was both a friend and rival to writers such as Mihai Eminescu, Titu Maiorescu, and Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea

Barbu Ștefănescu Delavrancea ; pen name of Barbu Ștefan; April 11, 1858 in Bucharest – April 29, 1918 in Iași) was a Romanian writer and poet, considered one of the greatest figures in the National awakening of Romania.

Early life and ...

, while maintaining contacts with, among others, the ''Junimist'' essayist Iacob Negruzzi

Iacob C. Negruzzi (December 31, 1842 – January 6, 1932) was a Moldavian, later Romanian poet and prose writer.

Born in Iași, he was the son of Constantin Negruzzi and his wife Maria (''née'' Gane). Living in Berlin between 1853 and 1863, he at ...

, the socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the e ...

philosopher Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea

Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea (born Solomon Katz; 1855, village of Slavyanka near Yekaterinoslav (modern Dnipro), then in Imperial Russia – 1920, Bucharest) was a Romanian Marxist theorist, politician, sociologist, literary critic, and j ...

, the literary critic Paul Zarifopol

Paul Zarifopol (November 30, 1874 – May 1, 1934) was a Romanian literary and social critic, essayist, and

literary historian. The scion of an aristocratic family, formally trained in both philology and the sociology of literature, he emer ...

, the poets George Coșbuc

George Coșbuc (; 20 September 1866 – 9 May 1918) was a Romanian poet, translator, teacher, and journalist, best remembered for his verses describing, praising and eulogizing rural life, its many travails but also its occasions for joy. In 19 ...

and Mite Kremnitz

Mite Kremnitz (4 January 1852, Greifswald – 18 July 1916 in Berlin), born Marie von Bardeleben (pen names ''George Allan'', ''Ditto and Idem''), was a German writer.

Biography

Kremnitz was the daughter of the famous surgeon Heinrich Adolf ...

, the psychologist Constantin Rădulescu-Motru

Constantin Rădulescu-Motru (; born Constantin Rădulescu, he added the surname ''Motru'' in 1892; February 15, 1868 – March 6, 1957) was a Romanian philosopher, psychologist, sociologist, logician, academic, dramatist, as well as left-nat ...

, and the Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

n poet and activist Octavian Goga

Octavian Goga (; 1 April 1881 – 7 May 1938) was a Romanian politician, poet, playwright, journalist, and translator.

Life and politics

Goga was born in Rășinari, near Sibiu.

Goga was an active member in the Romanian nationalisti ...

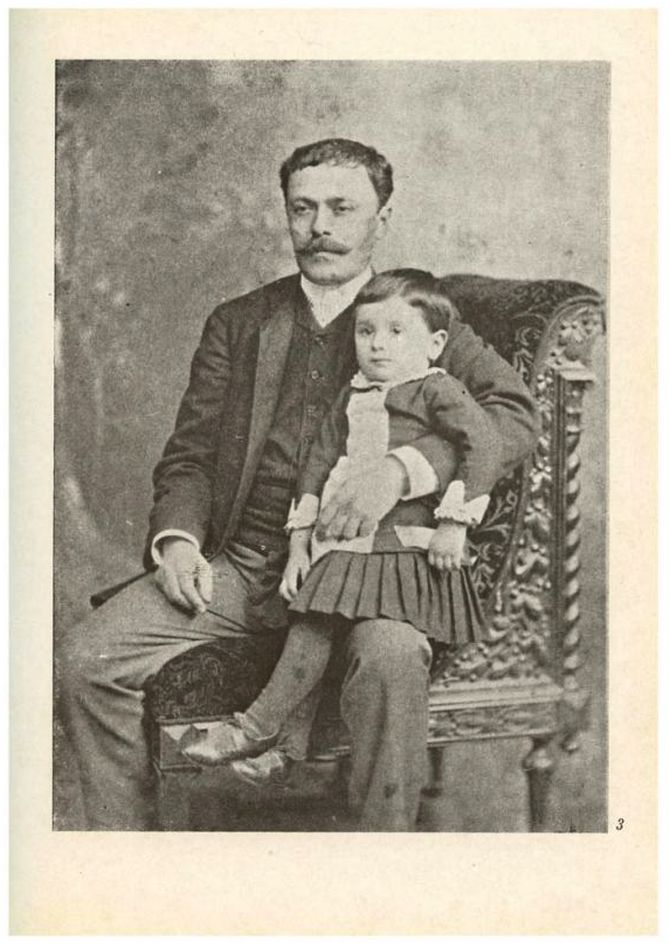

. Ion Luca was the nephew of Costache and Iorgu Caragiale, who were major figures of the 19th century Romanian theatre. His sons Mateiu and Luca

The last universal common ancestor (LUCA) is the most recent population from which all organisms now living on Earth share common descent—the most recent common ancestor of all current life on Earth. This includes all cellular organisms; th ...

were both modernist

Modernism is both a philosophical and arts movement that arose from broad transformations in Western society during the late 19th and early 20th centuries. The movement reflected a desire for the creation of new forms of art, philosophy, an ...

writers.

Biography

Background and name

Ion Luca Caragiale was born into a family ofGreek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

descent, whose members first arrived in Wallachia soon after 1812, during the rule of Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

Ioan Gheorghe Caragea—Ștefan Caragiali, as his grandfather was known locally, worked as a cook for the court in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

. Rosana Heinisch"Grecii, mai interesaţi de opera lui I.L.Caragiale decit conaţionalii săi"

, in '' Evenimentul'', 8 June 2002 Lucian Nastasă

''Genealogia între ştiinţă, mitologie şi monomanie''

p. 18, at the

Romanian Academy

The Romanian Academy ( ro, Academia Română ) is a cultural forum founded in Bucharest, Romania, in 1866. It covers the scientific, artistic and literary domains. The academy has 181 active members who are elected for life.

According to its byl ...

's George Bariţ Institute of History, Cluj-Napoca. Retrieved 3 July 2007.

Ion Luca's father, who reportedly originated from the Ottoman capital of Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

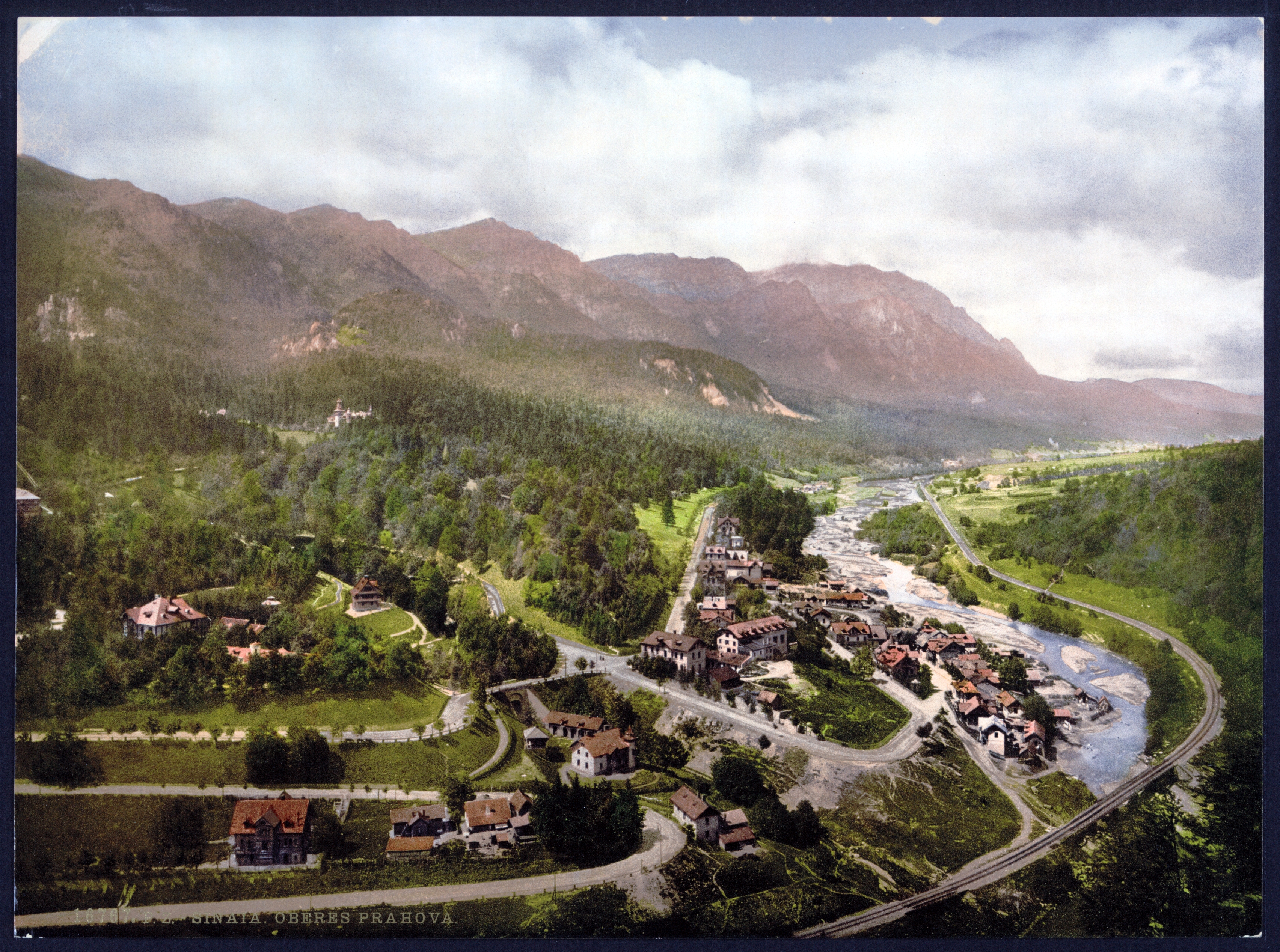

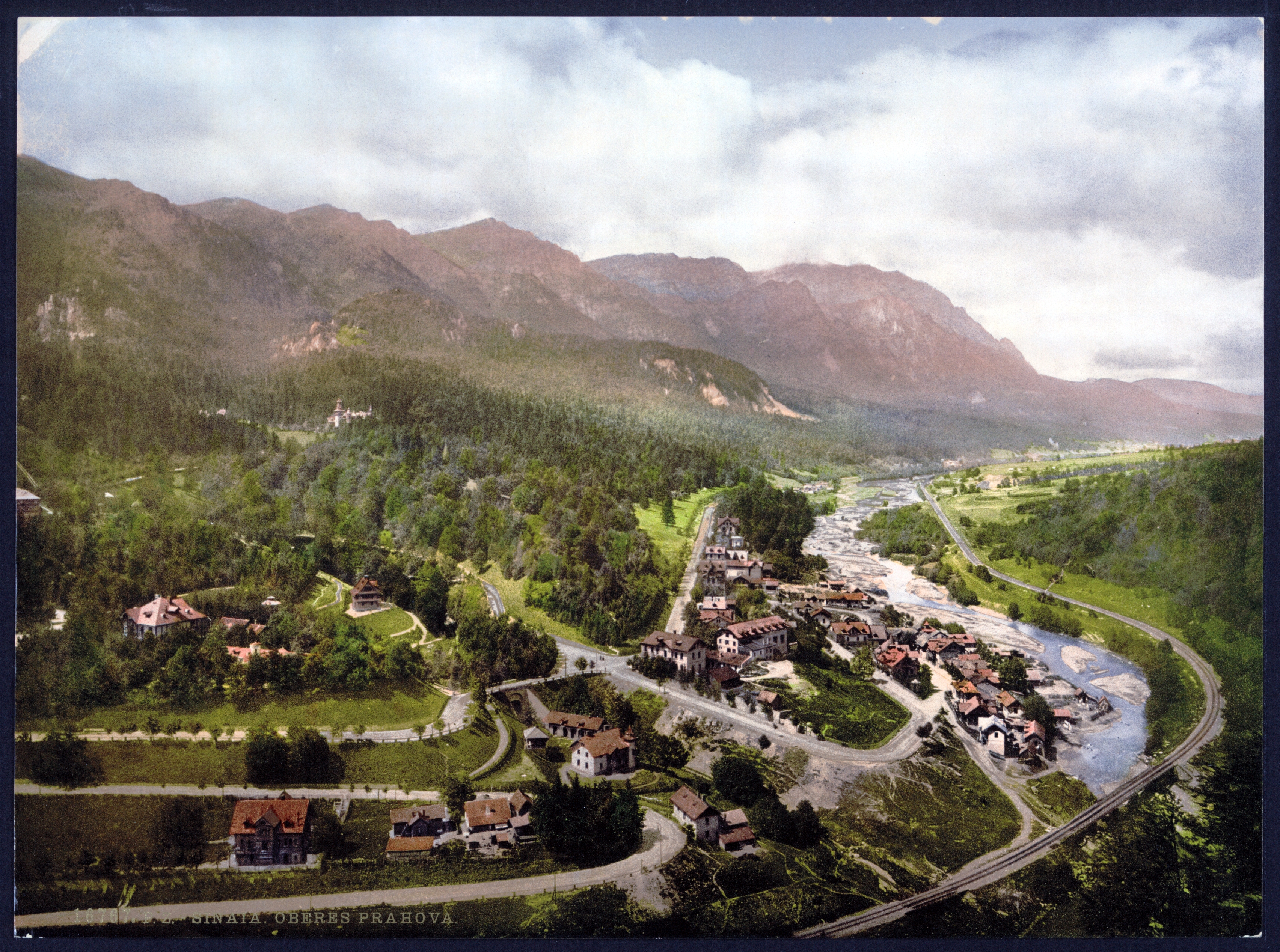

, settled in Prahova County

Prahova County () is a county ( județ) of Romania, in the historical region Muntenia, with the capital city at Ploiești.

Demographics

In 2011, it had a population of 762,886 and the population density was 161/km². It is Romania's third mos ...

as the curator of the Mărgineni Monastery (which, at the time, belonged to the Greek Orthodox

The term Greek Orthodox Church (Greek language, Greek: Ἑλληνορθόδοξη Ἐκκλησία, ''Ellinorthódoxi Ekklisía'', ) has two meanings. The broader meaning designates "the Eastern Orthodox Church, entire body of Orthodox (Chalced ...

Saint Catherine's Monastery

Saint Catherine's Monastery ( ar, دير القدّيسة كاترين; grc-gre, Μονὴ τῆς Ἁγίας Αἰκατερίνης), officially the Sacred Autonomous Royal Monastery of Saint Katherine of the Holy and God-Trodden Mount Sinai, ...

of Mount Sinai

Mount Sinai ( he , הר סיני ''Har Sinai''; Aramaic: ܛܘܪܐ ܕܣܝܢܝ ''Ṭūrāʾ Dsyny''), traditionally known as Jabal Musa ( ar, جَبَل مُوسَىٰ, translation: Mount Moses), is a mountain on the Sinai Peninsula of Egypt. It is ...

). Known to locals as Luca Caragiali, he later built a reputation as a lawyer and judge in Ploiești

Ploiești ( , , ), formerly spelled Ploești, is a city and county seat in Prahova County, Romania. Part of the historical region of Muntenia, it is located north of Bucharest.

The area of Ploiești is around , and it borders the Blejoi commu ...

, and married Ecaterina, the daughter of a merchant from the Transylvania

Transylvania ( ro, Ardeal or ; hu, Erdély; german: Siebenbürgen) is a historical and cultural region in Central Europe, encompassing central Romania. To the east and south its natural border is the Carpathian Mountains, and to the west the Ap ...

n town of Brașov

Brașov (, , ; german: Kronstadt; hu, Brassó; la, Corona; Transylvanian Saxon: ''Kruhnen'') is a city in Transylvania, Romania and the administrative centre of Brașov County.

According to the latest Romanian census (2011), Brașov has a popu ...

.Vianu, Vol. II, pg. 176 Georgeta Ene, , in ''Magazin Istoric

''Magazin Istoric'' ( en, The Historical Magazine) is a Romanian monthly magazine.

Overview

''Magazin Istoric'' was started in 1967. The first issue appeared in April 1967. The headquarters is in Bucharest. The monthly magazine contains articles ...

'', January 2002, pp. 12-17 Her maiden name

When a person (traditionally the wife in many cultures) assumes the family name of their spouse, in some countries that name replaces the person's previous surname, which in the case of the wife is called the maiden name ("birth name" is also used ...

was given as ''Alexovici'' (''Alexevici'') or as ''Karaboa'' (''Caraboa''). She is known to have been Greek herself, Ioan Holban"I.L. Caragiale, fiul unui emigrant din Cefallonia (III)"

in '' Evenimentul'', 25 May 2002. and, according to historian Lucian Nastasă, some of her relatives were Hungarian members of the Tabay family. The couple also had a daughter, named Lenci. Ion Luca's uncles, Costache and Iorgu Caragiale, managed theater troupes and were very influential figures in the development of early Romanian theatre — in Wallachia and

Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

alike.Dan Mănucă, "Caragiale", in Jean-Claude Polet, ''Patrimoine littéraire européen: anthologie en langue française'', De Boeck Université, Paris, 2000, pp. 478-479; Luca Caragiali had himself performed with his brothers during his youth, before opting to settle down. All three had stood criticism for not taking part in the Wallachian Revolution, and defended themselves through a brochure

A brochure is originally an Information, informative paper document (often also used for advertising) that can be folded into a template, pamphlet, or Folded leaflet, leaflet. A brochure can also be a set of related unfolded papers put into a po ...

printed in 1848. The Caragiali brothers had two sisters, Ecaterina and Anastasia. Doina Tudorovic"Caragiale: 'ai avesi, tomnilor, cu numele meu?'"

in ''

Ziarul Financiar

''Ziarul Financiar'' is a daily financial newspaper published in Bucharest, Romania. Aside from business information, it features sections focusing on careers and properties, as well as a special Sunday newspaper. ''Ziarul Financiar'' also publish ...

'', 5 July 2000.

Especially in his old age, the writer emphasized his family's humble background and his status as a self-made man

"Self-made man" is a classic phrase coined on February 2, 1842 by Henry Clay in the United States Senate, to describe individuals whose success lay within the individuals themselves, not with outside conditions. Benjamin Franklin, one of the Foun ...

. On one occasion, he defined the landscape of his youth as "the quagmires of Ploiești".Vianu, Vol. II, pg. 197 Although it prompted his biographer Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea

Constantin Dobrogeanu-Gherea (born Solomon Katz; 1855, village of Slavyanka near Yekaterinoslav (modern Dnipro), then in Imperial Russia – 1920, Bucharest) was a Romanian Marxist theorist, politician, sociologist, literary critic, and j ...

to define him as "a proletarian

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose only possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian. Marxist philoso ...

", Caragiale's account was disputed by several other researchers, who noted that the family had a good social standing.

Ion Luca Caragiale was discreet about his ethnic origin for the larger part of his life. In parallel, his foreign roots came to the attention of his adversaries, who used them as arguments in various polemics.Sorin Antohi

Sorin Antohi (born 20 August 1957) is a Romanian historian, essayist, and journalist.

Biography

Antohi was born in Târgu Ocna, Bacău County. He received his Bachelor of Arts and Master of Arts degrees from the University of Iași and a DEA fro ...

"Romania and the Balkans. From Geocultural Bovarism to Ethnic Ontology"

in ''Tr@nsit online'', Nr. 21/2002,

Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen

The Institute for Human Sciences (german: Institut für die Wissenschaften vom Menschen, IWM) is an independent institute for advanced study in the humanities and social sciences based in Vienna, Austria.

History and core idea

The IWM was found ...

As his relations with Caragiale degenerated into hostility, Mihai Eminescu

Mihai Eminescu (; born Mihail Eminovici; 15 January 1850 – 15 June 1889) was a Romanian Romantic poet from Moldavia, novelist, and journalist, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet. Eminescu was an active membe ...

is known to have referred to his former friend as "that Greek swindler".Cristea-Enache, chapter "Corespondenţa inedită Mihai Eminescu – Veronica Micle. Filigranul geniului" Aware of such treatment, the writer considered all references to his lineage to be insults. On several occasions, he preferred to indicate that he was "of obscure birth".

Nevertheless, as literary critic

Nevertheless, as literary critic Tudor Vianu

Tudor Vianu (; January 8, 1898 – May 21, 1964) was a Romanian literary criticism, literary critic, art critic, poet, philosopher, academic, and translator. He had a major role on the reception and development of Modernism in Literature of Roma ...

noted, Caragiale's outlook on life was explicitly Balkan

The Balkans ( ), also known as the Balkan Peninsula, is a geographical area in southeastern Europe with various geographical and historical definitions. The region takes its name from the Balkan Mountains that stretch throughout the who ...

ic and Orient

The Orient is a term for the East in relation to Europe, traditionally comprising anything belonging to the Eastern world. It is the antonym of ''Occident'', the Western World. In English, it is largely a metonym for, and coterminous with, the c ...

al, which, in Vianu's view, mirrored a type "which must have been found in his lineage".Vianu, Vol. II, pg. 195 A similar opinion was expressed by Paul Zarifopol

Paul Zarifopol (November 30, 1874 – May 1, 1934) was a Romanian literary and social critic, essayist, and

literary historian. The scion of an aristocratic family, formally trained in both philology and the sociology of literature, he emer ...

, who speculated that Caragiale's conservative mindset was possibly owed to the "lazyness of one true Oriental" Paul Zarifopol

Paul Zarifopol (November 30, 1874 – May 1, 1934) was a Romanian literary and social critic, essayist, and

literary historian. The scion of an aristocratic family, formally trained in both philology and the sociology of literature, he emer ...

''Introduceri la ediţia critică I.L. Caragiale, opere''

(wikisource) (elsewhere, he referred to the writer as "a lazy southerner, fitted with definitely supranormal intelligence and imagination").

Paul Zarifopol

Paul Zarifopol (November 30, 1874 – May 1, 1934) was a Romanian literary and social critic, essayist, and

literary historian. The scion of an aristocratic family, formally trained in both philology and the sociology of literature, he emer ...

, Artiști și idei literare române: Publicul și arta lui Caragiale

' (wikisource) In his main work on the history of Romanian literature,

George Călinescu

George Călinescu (; 19 June 1899, Bucharest – 12 March 1965, Otopeni) was a Romanian literary critic, historian, novelist, academician and journalist, and a writer of classicist and humanist tendencies. He is currently considered one of the mos ...

included Caragiale among a group of "Balkan" writers, whose middle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Commo ...

status and often foreign origin, he argued, set them apart irrespective of their period—others in this category were, in chronological order, Anton Pann

Anton Pann (; born Antonie Pantoleon-Petroveanu , and also mentioned as ''Anton Pantoleon'' or ''Petrovici''; 1790s—2 November 1854) was an Ottoman-born Wallachian composer, musicologist, and Romanian-language poet, also noted for his act ...

, Tudor Arghezi

Tudor Arghezi (; 21 May 1880 – 14 July 1967) was a Romanian writer, best known for his unique contribution to poetry and children's literature. Born Ion N. Theodorescu in Bucharest, he explained that his pen name was related to ''Argesis'', th ...

, Ion Minulescu

Ion Minulescu (; 6 January 1881 – 11 April 1944) was a Romanian avant-garde poet, novelist, short story writer, journalist, literary critic, and playwright. Often publishing his works under the pseudonyms I. M. Nirvan and Koh-i-Noor (the latte ...

, Urmuz

Urmuz (, pen name of Demetru Dem. Demetrescu-Buzău, also known as Hurmuz or Ciriviș, born Dimitrie Dim. Ionescu-Buzeu; March 17, 1883 – November 23, 1923) was a Romanian writer, lawyer and civil servant, who became a cult hero in Romania's ava ...

, Mateiu Caragiale

Mateiu Ion Caragiale (; – January 17, 1936), also credited as Matei or Matheiu, or in the antiquated version Mateiŭ,Sorin Antohi"Romania and the Balkans. From Geocultural Bovarism to Ethnic Ontology" in ''Tr@nsit online'', Institut für die ...

, and Ion Barbu

Ion Barbu (, pen name of Dan Barbilian; 18 March 1895 –11 August 1961) was a Romanian mathematician and poet. His name is associated with the Mathematics Subject Classification number 51C05, which is a major posthumous recognition reserved ...

. In contrast, critic Garabet Ibrăileanu

Garabet Ibrăileanu (; May 23, 1871 – March 11, 1936) was a Romanian-Armenians in Romania, Armenian Literary criticism, literary critic and theorist, writer, translator, sociologist, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, University of Iași professor ...

proposed that Caragiale's Wallachian origin was of particular importance, serving to explain his political choices and alleged social bias. Garabet Ibrăileanu

Garabet Ibrăileanu (; May 23, 1871 – March 11, 1936) was a Romanian-Armenians in Romania, Armenian Literary criticism, literary critic and theorist, writer, translator, sociologist, Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, University of Iași professor ...

''Spiritul critic în cultura românească: Spiritul critic în Muntenia – Critica socială extremă: Caragiale''

(wikisource) On one occasion, Caragiale mentioned that his paternal grandfather was "a Greek cook". In several contexts, he referred to his roots as being in the island of Hydra. In one of his photographs, he posed in Oriental costume and sitting cross-legged, which was interpreted by Vianu as an additional reference to his Balkan background. Two of his biographers, Zarifopol and

Șerban Cioculescu

Șerban Cioculescu (; 7 September 1902 – 25 June 1988) was a Romanian literary critic, literary historian and columnist, who held teaching positions in Romanian literature at the University of Iași and the University of Bucharest, as well as m ...

, noted that a section of Caragiale's fairy tale

A fairy tale (alternative names include fairytale, fairy story, magic tale, or wonder tale) is a short story that belongs to the folklore genre. Such stories typically feature magic (paranormal), magic, incantation, enchantments, and mythical ...

'' Kir Ianulea'' was a likely self-reference: in that fragment of text, the Christian Devil, disguised as an Arvanite

Arvanites (; Arvanitika: , or , ; Greek: , ) are a bilingual population group in Greece of Albanian origin. They traditionally speak Arvanitika, an Albanian language variety, along with Greek. Their ancestors were first recorded as settler ...

trader, is shown taking pride in his Romanian language

Romanian (obsolete spellings: Rumanian or Roumanian; autonym: ''limba română'' , or ''românește'', ) is the official and main language of Romania and the Moldova, Republic of Moldova. As a minority language it is spoken by stable communi ...

skills.

Investigations carried out by the Center of Theatric Research in Athens

Athens ( ; el, Αθήνα, Athína ; grc, Ἀθῆναι, Athênai (pl.) ) is both the capital and largest city of Greece. With a population close to four million, it is also the seventh largest city in the European Union. Athens dominates ...

, Greece

Greece,, or , romanized: ', officially the Hellenic Republic, is a country in Southeast Europe. It is situated on the southern tip of the Balkans, and is located at the crossroads of Europe, Asia, and Africa. Greece shares land borders with ...

and made public in 2002 offered an alternative take on the Caragiales' origin. According to this perspective, Ștefan Caragiali was a native of Kefalonia

Kefalonia or Cephalonia ( el, Κεφαλονιά), formerly also known as Kefallinia or Kephallenia (), is the largest of the Ionian Islands in western Greece and the 6th largest island in Greece after Crete, Euboea, Lesbos, Rhodes and Chios. It ...

, and his original surname, ''Karaialis'', was changed on Prince Caragea's request. Various authors also believe that Caragiale's ancestors were Albanian

Albanian may refer to:

*Pertaining to Albania in Southeast Europe; in particular:

**Albanians, an ethnic group native to the Balkans

**Albanian language

**Albanian culture

**Demographics of Albania, includes other ethnic groups within the country ...

or Aromanian.

Originally, Ion Luca was known as ''Ioanne L. Caragiali''."Casele lui Caragiale", in ''

Adevărul

''Adevărul'' (; meaning "The Truth", formerly spelled ''Adevĕrul'') is a Romanian daily newspaper, based in Bucharest. Founded in Iași, in 1871, and reestablished in 1888, in Bucharest, it was the main left-wing press venue to be published dur ...

'', 30 January 2002. His family and friends knew him as ''Iancu'' or, rarely, ''Iancuțu''—both being antiquated hypocoristic

A hypocorism ( or ; from Ancient Greek: (), from (), 'to call by pet names', sometimes also ''hypocoristic'') or pet name is a name used to show affection for a person. It may be a diminutive form of a person's name, such as ''Izzy'' for I ...

s of ''Ion''. The definitive full version of his features the syllable ''ca'' twice in a row, which is generally avoided in Romanian due to its scatological connotations. It has however become one of the few cacophonies accepted by the Romanian Academy

The Romanian Academy ( ro, Academia Română ) is a cultural forum founded in Bucharest, Romania, in 1866. It covers the scientific, artistic and literary domains. The academy has 181 active members who are elected for life.

According to its byl ...

.

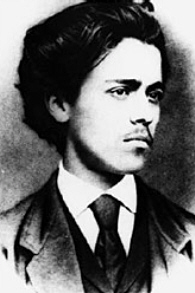

Early years

Born in the village of Haimanale, Prahova County (the present-day I. L. Caragiale

Born in the village of Haimanale, Prahova County (the present-day I. L. Caragiale commune

A commune is an alternative term for an intentional community. Commune or comună or comune or other derivations may also refer to:

Administrative-territorial entities

* Commune (administrative division), a municipality or township

** Communes of ...

, Dâmbovița County

Dâmbovița County (also spelt ''Dîmbovița'', ) is a county ( județ) of Romania, in Muntenia, with the capital city at Târgoviște, the most important economic, political, administrative and cultural center of the county.

It has an area of ...

), Caragiale was educated in Ploiești. During his early years, as he later indicated, he learned reading and writing with a teacher at the Romanian Orthodox Church

The Romanian Orthodox Church (ROC; ro, Biserica Ortodoxă Română, ), or Patriarchate of Romania, is an autocephalous Eastern Orthodox church in full communion with other Eastern Orthodox Christian denomination, Christian churches, and one of ...

of Saint George.Mîndra, p. 272 Soon after, he was taught literary Romanian by the Transylvanian-born Bazilie Dragoșescu (whose influence on his use of the language he was to acknowledge in one of his later works). At the age of seven, he witnessed enthusiastic celebrations of the Danubian Principalities

The Danubian Principalities ( ro, Principatele Dunărene, sr, Дунавске кнежевине, translit=Dunavske kneževine) was a conventional name given to the Principalities of Moldavia and Wallachia, which emerged in the early 14th ce ...

' union, with the election of Moldavia's Alexandru Ioan Cuza

Alexandru Ioan Cuza (, or Alexandru Ioan I, also anglicised as Alexander John Cuza; 20 March 1820 – 15 May 1873) was the first ''domnitor'' (Ruler) of the Romanian Principalities through his double election as prince of Moldavia on 5 Januar ...

as Prince

A prince is a male ruler (ranked below a king, grand prince, and grand duke) or a male member of a monarch's or former monarch's family. ''Prince'' is also a title of nobility (often highest), often hereditary, in some European states. Th ...

of Wallachia;Vianu, Vol. II, pg. 192 Cuza's subsequent reforms were to be an influence on the political choices Caragiale made in his old age. The new ruler visited his primary school later in 1859, being received with enthusiasm by Dragoșescu and all his pupils.

Caragiale completed gymnasium at the Sfinții Petru și Pavel school in the city, and never pursued any form of higher education. He was probably enlisted directly in the second grade, as records do not show him to have attended or graduated the first year. Notably, Caragiale was taught history by Constantin Iennescu, who was later the mayor of Ploiești.Mîndra, pg. 9 The young Caragiale opted to follow in his uncles' footsteps, and was taught declamation and mimic art by Costache at the latter's theater school in Bucharest

Bucharest ( , ; ro, București ) is the capital and largest city of Romania, as well as its cultural, industrial, and financial centre. It is located in the southeast of the country, on the banks of the Dâmbovița River, less than north of ...

, where he was accompanied by his mother and sister. It is also probable that he was a supernumerary actor

Supernumerary actors are usually amateur character actors in opera and ballet performances who train under professional direction to create a believable scene.

Definition

The term's original use, from the Latin ''supernumerarius'', meant someon ...

for the National Theater Bucharest

The National Theatre Bucharest ( ro, Teatrul Naţional "Ion Luca Caragiale" București) is one of the national theatres of Romania, located in the capital city of Bucharest.

Founding

It was founded as the ''Teatrul cel Mare din București'' ("Gra ...

. He was not able to find full employment in this field, and, around the age of 18, worked as a copyist for the Prahova County Tribunal. Throughout his life, Caragiale refused to talk about his training in the theater, and hid it from the people closest to him (including his wife Alexandrina Burelly, who came from an upper middle class environment).Cioculescu, pg. 6

In 1866, Caragiale witnessed Cuza's toppling by a coalition of conservatives

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilization in ...

and liberals — as he later acknowledged in his ''Grand Hotel "Victoria Română"'', he and his friends agreed to support the move by voting "yes" during a subsequent plebiscite

A referendum (plural: referendums or less commonly referenda) is a direct vote by the electorate on a proposal, law, or political issue. This is in contrast to an issue being voted on by a representative. This may result in the adoption of a ...

, and, with tacit approval from the new authorities, even did so several times each. By the age of 18, he was an enthusiastic supporter of the liberal current, and sympathized with its republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

ideals. In 1871, he witnessed the Republic of Ploiești — a short-lived stated created by the liberal groups, in an attempt to oust ''Domnitor

''Domnitor'' (Romanian pl. ''Domnitori'') was the official title of the ruler of Romania between 1862 and 1881. It was usually translated as "prince" in other languages and less often as "grand duke". Derived from the Romanian word "''domn''" ...

'' Carol I

Carol I or Charles I of Romania (20 April 1839 – ), born Prince Karl of Hohenzollern-Sigmaringen, was the monarch of Romania from 1866 to his death in 1914, ruling as Prince (''Domnitor'') from 1866 to 1881, and as King from 1881 to 1914. He w ...

(the future King of Romania

The King of Romania (Romanian: ''Regele României'') or King of the Romanians (Romanian: ''Regele Românilor''), was the title of the monarch of the Kingdom of Romania from 1881 until 1947, when the Romanian Workers' Party proclaimed the Romanian ...

). Later in life, as his opinions veered towards conservatism

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy that seeks to promote and to preserve traditional institutions, practices, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civilizati ...

, Caragiale ridiculed both the attempted ''coup d'état

A coup d'état (; French for 'stroke of state'), also known as a coup or overthrow, is a seizure and removal of a government and its powers. Typically, it is an illegal seizure of power by a political faction, politician, cult, rebel group, m ...

'' and his participation in it.

He returned to Bucharest later that year, after manager Mihail Pascaly hired him as one of the prompts at the National Theater in the capital, a period about which he reminisced in his '' Din carnetul unui vechi sufleur''. The poet Mihai Eminescu

Mihai Eminescu (; born Mihail Eminovici; 15 January 1850 – 15 June 1889) was a Romanian Romantic poet from Moldavia, novelist, and journalist, generally regarded as the most famous and influential Romanian poet. Eminescu was an active membe ...

, with whom Ion Luca was to have cordial relations as well as rivalries, had previously been employed for the same position by the manager Iorgu Caragiale. In addition to his growing familiarity with the repertoire

A repertoire () is a list or set of dramas, operas, musical compositions or roles which a company or person is prepared to perform.

Musicians often have a musical repertoire. The first known use of the word ''repertoire'' was in 1847. It is a l ...

, the young Caragiale educated himself by reading the philosophical works of Enlightenment-era ''philosophe

The ''philosophes'' () were the intellectuals of the 18th-century Enlightenment.Kishlansky, Mark, ''et al.'' ''A Brief History of Western Civilization: The Unfinished Legacy, volume II: Since 1555.'' (5th ed. 2007). Few were primarily philosophe ...

s''. It was also recorded that, at some point between 1870 and 1872, he was employed in the same capacity by the Moldavian National Theater in Iași. During the period, Caragiale also proofread

Proofreading is the reading of a galley proof or an electronic copy of a publication to find and correct reproduction errors of text or art. Proofreading is the final step in the editorial cycle before publication.

Professional

Traditional ...

for various publications and worked as a tutor

TUTOR, also known as PLATO Author Language, is a programming language developed for use on the PLATO system at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign beginning in roughly 1965. TUTOR was initially designed by Paul Tenczar for use in co ...

.

Literary debut

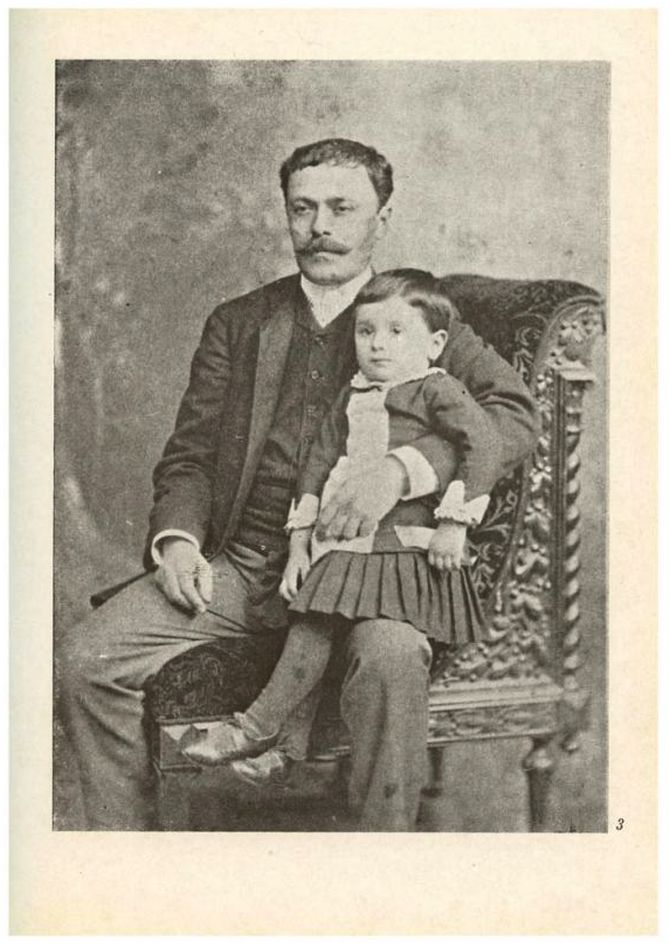

Ion Luca made his literary debut in 1873, at the age of 21, with poems and humorous chronicles printed in G. Dem. Teodorescu's liberal-inspired satirical magazine, ''Ghimpele''. He published relatively few articles under various

Ion Luca made his literary debut in 1873, at the age of 21, with poems and humorous chronicles printed in G. Dem. Teodorescu's liberal-inspired satirical magazine, ''Ghimpele''. He published relatively few articles under various pen name

A pen name, also called a ''nom de plume'' or a literary double, is a pseudonym (or, in some cases, a variant form of a real name) adopted by an author and printed on the title page or by-line of their works in place of their real name.

A pen na ...

s — among them ''Car.'', the contraction of his family name, and the more elaborate ''Palicar''. He mostly performed basic services for the editorial staff and its printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a printing, print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in wh ...

, given that, after Luca Caragiali died in 1870, he was the sole provider for his mother and sister. Following his return to Bucharest, he became even more involved with the radical

Radical may refer to:

Politics and ideology Politics

*Radical politics, the political intent of fundamental societal change

*Radicalism (historical), the Radical Movement that began in late 18th century Britain and spread to continental Europe and ...

and republican wing of the liberal trend—a movement commonly referred to as "the Reds". As he later confessed, he frequently attended its congresses, witnessing the speeches held by Reds leader C. A. Rosetti; he thus became intimately acquainted with a Populist

Populism refers to a range of political stances that emphasize the idea of "the people" and often juxtapose this group against " the elite". It is frequently associated with anti-establishment and anti-political sentiment. The term developed ...

discourse, which he later parodied in his works. Working for ''Ghimpele'', he made the acquaintance of republican writer N. T. Orășanu

Nicolae T. Orășanu (1833?–August 7, 1890) was a Wallachian-born Romanian poet, prose writer and newspaper editor.

Born in Craiova, he attended high school at Saint Sava College in the national capital Bucharest. As a young man, Orășanu e ...

.Mîndra, pg. 273

Several of his articles for ''Ghimpele'' were sarcastic in tone, and targeted various literary figures of the day. In June 1874, Caragiale amused himself at the expense of N. D. Popescu-Popnedea, the author of popular almanac

An almanac (also spelled ''almanack'' and ''almanach'') is an annual publication listing a set of current information about one or multiple subjects. It includes information like weather forecasts, farmers' planting dates, tide tables, and other ...

s, whose taste he questioned.Cioculescu, pg. 52 Soon after, he ridiculed the rising poet Alexandru Macedonski

Alexandru Macedonski (; also rendered as Al. A. Macedonski, Macedonschi or Macedonsky; 14 March 1854 – 24 November 1920) was a Romanian poet, novelist, dramatist and literary critic, known especially for having promoted French Symbolism in h ...

, who had publicized his claim that he was a "Count Geniadevsky", and thus of Polish

Polish may refer to:

* Anything from or related to Poland, a country in Europe

* Polish language

* Poles

Poles,, ; singular masculine: ''Polak'', singular feminine: ''Polka'' or Polish people, are a West Slavic nation and ethnic group, w ...

origin. The article contributed by Caragiale, in which he speculated that Macedonski (referred to with the anagram

An anagram is a word or phrase formed by rearranging the letters of a different word or phrase, typically using all the original letters exactly once. For example, the word ''anagram'' itself can be rearranged into ''nag a ram'', also the word ...

''Aamsky'') was using the name solely because it reminded people of the word "genius",Vianu, Vol. II, pg. 177 was the first act in a long polemic between the two literary figures. Caragiale turned Aamsky into a character on his own, envisaging his death as a result of overwork in editing magazines "for the country's political development".

Caragiale also contributed poetry to ''Ghimpele'': two sonnet

A sonnet is a poetic form that originated in the poetry composed at the Court of the Holy Roman Emperor Frederick II in the Sicilian city of Palermo. The 13th-century poet and notary Giacomo da Lentini is credited with the sonnet's invention, ...

s, and a series of epigram

An epigram is a brief, interesting, memorable, and sometimes surprising or satirical statement. The word is derived from the Greek "inscription" from "to write on, to inscribe", and the literary device has been employed for over two mille ...

s (one of which was another attack on Macedonski). The first of these works, an 1873 sonnet dedicated to the baritone

A baritone is a type of classical male singing voice whose vocal range lies between the bass and the tenor voice-types. The term originates from the Greek (), meaning "heavy sounding". Composers typically write music for this voice in the r ...

Agostino Mazzoli, is believed to have been his first contribution to the ''belles-lettres

is a category of writing, originally meaning beautiful or fine writing. In the modern narrow sense, it is a label for literary works that do not fall into the major categories such as fiction, poetry, or drama. The phrase is sometimes used pejora ...

'' (as opposed to journalism).

In 1896, Macedonski reflected with irony:"As early as 1872, the clients of someOver the following years, Caragiale collaborated on various mouthpieces of the newly created National Liberal Party, and, in May 1877, created the satirical magazine '' Claponul''. Later in 1877, he also translated a series ofbeer garden A beer garden (German: ''Biergarten'') is an outdoor area in which beer and food are served, typically at shared tables shaded by trees. Beer gardens originated in Bavaria, of which Munich is the capital city, in the 19th century, and remain co ...s in the capital have had the occasion to welcome among them of a noisy young man, a bizarre spirit who seemed destined, were he to have devoted himself to letters or the arts, to be entirely original. Indeed, this young man's appearance, his hasty gestures, his sarcastic smile .. his always irritated and mocking voice, as well as his sophistic reasoning easily attracted attention."

French-language

French ( or ) is a Romance language of the Indo-European family. It descended from the Vulgar Latin of the Roman Empire, as did all Romance languages. French evolved from Gallo-Romance, the Latin spoken in Gaul, and more specifically in Nor ...

plays for the National Theater: Alexandre Parodi

Alexandre Parodi (b. 1 June 1901 - d.15 March 1979) liases Quartus and Cératwas a French senior civil servant, a member of the French resistance, General de Gaulle's appointee in charge of the French provisional government during World War I ...

's ''Rome vaincue'' (it was showcased in late 1877-early 1878), Paul Déroulède

Paul Déroulède (2 September 1846 – 30 January 1914) was a French author and politician, one of the founders of the nationalist League of Patriots.

Early life

Déroulède was born in Paris. He was published first as a poet in the magazine '' ...

's ''L'Hetman'', and Eugène Scribe

Augustin Eugène Scribe (; 24 December 179120 February 1861) was a French dramatist and librettist. He is known for writing "well-made plays" ("pièces bien faites"), a mainstay of popular theatre for over 100 years, and as the librettist of ma ...

's ''Une camaraderie''.Vianu, Vol. II, p. 178 Together with the French republican Frédéric Damé

Frédéric and Frédérick are the French versions of the common male given name Frederick. They may refer to:

In artistry:

* Frédéric Back, Canadian award-winning animator

* Frédéric Bartholdi, French sculptor

* Frédéric Bazille, Impress ...

, he also headed a short-lived journal, ''Națiunea Română''.

It was also then that he contributed a serialized overview of Romanian theater, published by the newspaper ''România Liberă

''România liberă'' ("") is a Romanian daily newspaper founded in 1943 and currently based in Bucharest. A newspaper of the same name also existed between 1877 and 1888.

History and profile

The name ''România liberă'' was first used by a dai ...

'', in which Caragiale attacked the inferiority of Romanian dramaturgy

Dramaturgy is the study of dramatic composition and the Representation (arts), representation of the main elements of drama on the stage.

The term first appears in the eponymous work ''Hamburg Dramaturgy'' (1767–69) by Gotthold Ephraim Lessing ...

and the widespread recourse to plagiarism

Plagiarism is the fraudulent representation of another person's language, thoughts, ideas, or expressions as one's own original work.From the 1995 '' Random House Compact Unabridged Dictionary'': use or close imitation of the language and thought ...

. According to literary historian Perpessicius

Perpessicius (; pen name of Dumitru S. Panaitescu, also known as Panait Șt. Dumitru, D. P. Perpessicius and Panaitescu-Perpessicius; October 22, 1891 – March 29, 1971) was a Romanian literary historian and critic, poet, essayist and fiction wri ...

, the series constituted "one of the most solid critical contributions to the history of our theater".

Macedonski later alleged that, in his contributions to the liberal newspapers, the young writer had libel

Defamation is the act of communicating to a third party false statements about a person, place or thing that results in damage to its reputation. It can be spoken (slander) or written (libel). It constitutes a tort or a crime. The legal defini ...

ed several Conservative Party

The Conservative Party is a name used by many political parties around the world. These political parties are generally right-wing though their exact ideologies can range from center-right to far-right.

Political parties called The Conservative P ...

politicians—when researching this period, Șerban Cioculescu

Șerban Cioculescu (; 7 September 1902 – 25 June 1988) was a Romanian literary critic, literary historian and columnist, who held teaching positions in Romanian literature at the University of Iași and the University of Bucharest, as well as m ...

concluded that the accusation was false, and that only one polemical article on a political topic could be traced back to Caragiale.

''Timpul'' and ''Claponul''

The young journalist began drifting away from National Liberal politics soon after 1876, when the group came to power with

The young journalist began drifting away from National Liberal politics soon after 1876, when the group came to power with Ion Brătianu

An ion () is an atom or molecule with a net electrical charge.

The charge of an electron is considered to be negative by convention and this charge is equal and opposite to the charge of a proton, which is considered to be positive by conven ...

as Premier

Premier is a title for the head of government in central governments, state governments and local governments of some countries. A second in command to a premier is designated as a deputy premier.

A premier will normally be a head of governm ...

.Cioculescu, p. 20 According to many versions, Eminescu, who was working on the editorial staff of the main Conservative newspaper, ''Timpul

''Timpul'' (Romanian for "The Time") is a literary magazine published in Romania

Romania ( ; ro, România ) is a country located at the crossroads of Central, Eastern, and Southeastern Europe. It borders Bulgaria to the south, Ukraine t ...

'', asked to be joined by Caragiale and the Transylvanian prose writer Ioan Slavici

Ioan Slavici (; 18 January 1848 – 17 August 1925) was a Romanians, Romanian writer and journalist from Hungary, later from Romania.

He made his debut in ''Convorbiri literare'' ("Literary Conversations") (1871), with the comedy ''Fata de biră ...

, who were both employed by the paper. This order of events remains unclear, and depends on sources saying that Eminescu was employed by the paper in March 1876.Ornea, p. 246 Other testimonies indicate that it was actually Eminescu who arrived last, beginning work in January 1878.

Slavici later recalled that three of them engaged in lengthy discussions at ''Timpuls headquarters on Calea Victoriei CALEA may refer to:

*Communications Assistance for Law Enforcement Act, an act by the US Congress to facilitate wiretapping of U.S. domestic telephone and Internet traffic

*Commission on Accreditation for Law Enforcement Agencies, a private accredit ...

and in Eminescu's house on Sfinților Street, where they planned to co-author a massive work on Romanian grammar. According to literary historian Tudor Vianu

Tudor Vianu (; January 8, 1898 – May 21, 1964) was a Romanian literary criticism, literary critic, art critic, poet, philosopher, academic, and translator. He had a major role on the reception and development of Modernism in Literature of Roma ...

, the relationship between Caragiale and Eminescu partly replicated that between the latter and the Moldavia

Moldavia ( ro, Moldova, or , literally "The Country of Moldavia"; in Romanian Cyrillic: or ; chu, Землѧ Молдавскаѧ; el, Ἡγεμονία τῆς Μολδαβίας) is a historical region and former principality in Centr ...

n Ion Creangă.

Over that period, ''Timpul'' and Eminescu were engaged in a harsh polemic with the Reds, and especially their leader Rosetti.Vianu, Vol. II, p. 147 It was also then that Romania entered the Russo-Turkish War

The Russo-Turkish wars (or Ottoman–Russian wars) were a series of twelve wars fought between the Russian Empire and the Ottoman Empire between the 16th and 20th centuries. It was one of the longest series of military conflicts in European histo ...

as a means to secure her complete independence from the Ottoman Empire

The Ottoman Empire, * ; is an archaic version. The definite article forms and were synonymous * and el, Оθωμανική Αυτοκρατορία, Othōmanikē Avtokratoria, label=none * info page on book at Martin Luther University) ...

. Caragiale reportedly took little interest in editing ''Timpul'' over that period, but it is assumed that several unsigned chronicles, covering foreign events, are his contributions (as are two short story adaptations of works by the American

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

author Edgar Allan Poe

Edgar Allan Poe (; Edgar Poe; January 19, 1809 – October 7, 1849) was an American writer, poet, editor, and literary critic. Poe is best known for his poetry and short stories, particularly his tales of mystery and the macabre. He is wide ...

, both published by ''Timpul'' in spring-summer 1878). The newspaper was actually issued as a collaborative effort, which makes it hard to identify the authors of many other articles. According to Slavici, Caragiale occasionally completed unfinished contributions by Eminescu whenever the latter had to leave unexpectedly.

He concentrated instead on ''Claponul'', which he edited and wrote single-handedly for the duration of the war. Zarifopol believed that, through the series of light satires he contributed for the magazine, Caragiale was trying out his style, and thus "entertaining the suburbanites, in order to study them". A piece he authored of the time featured an imaginary barber and amateur artist, Năstase Știrbu, who drew a direct parallel between art, literature and cutting hair—both the theme and the character were to be reused in his later works. Similarly, a fragment of prose referring to two inseparable friends, Șotrocea and Motrocea, was to serve as the first draft for the Lache and Mache

The Lache ( ; sometimes simply Lache) is a housing estate in the city of Chester, in Cheshire, United Kingdom, with a population of around 10,000. It is located approximately southwest of the ancient city, with good local transport links en ...

series in ''Momente și schițe

''Momente'' (Moments) is a work by the German composer Karlheinz Stockhausen, written between 1962 and 1969, scored for solo soprano, four mixed choirs, and thirteen instrumentalists (four trumpets, four trombones, three percussionists, and two ...

''. Another notable work of the time is ''Pohod la șosea'', a rhyming reportage

Journalism is the production and distribution of reports on the interaction of events, facts, ideas, and people that are the "news of the day" and that informs society to at least some degree. The word, a noun, applies to the occupation (profes ...

documenting the Russian Army

The Russian Ground Forces (russian: Сухопутные войска �В Sukhoputnyye voyska V, also known as the Russian Army (, ), are the Army, land forces of the Russian Armed Forces.

The primary responsibilities of the Russian Gro ...

's arrival to Bucharest, and the street reactions to the event. ''Claponul'' ceased publication in early 1878.

''Junimea'' reception

It was probably through Eminescu that Ion Luca Caragiale came into contact with theIași

Iași ( , , ; also known by other alternative names), also referred to mostly historically as Jassy ( , ), is the second largest city in Romania and the seat of Iași County. Located in the historical region of Moldavia, it has traditionally ...

-based ''Junimea

''Junimea'' was a Romanian literary society founded in Iași in 1863, through the initiative of several foreign-educated personalities led by Titu Maiorescu, Petre P. Carp, Vasile Pogor, Theodor Rosetti and Iacob Negruzzi. The foremost personali ...

'', the influential literary society which was also a center for anti-National Liberal politics. Initially, Caragiale met with ''Junimea'' founder, the critic and politician Titu Maiorescu

Titu Liviu Maiorescu (; 15 February 1840 – 18 June 1917) was a Romanian literary critic and politician, founder of the ''Junimea'' Society. As a literary critic, he was instrumental in the development of Romanian culture in the second half of ...

, during a visit to the house of Dr. Kremnitz, physician to the family of ''Domnitor

''Domnitor'' (Romanian pl. ''Domnitori'') was the official title of the ruler of Romania between 1862 and 1881. It was usually translated as "prince" in other languages and less often as "grand duke". Derived from the Romanian word "''domn''" ...

'' Carol I