intellectual on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

An intellectual is a person who engages in

An intellectual is a person who engages in

The 19th-century U.S.

The 19th-century U.S.

The French philosopher

The French philosopher

Inter-Disciplinary Press

. * Bates, David, ed., (2007). ''Marxism, Intellectuals and Politics.'' London: Palgrave. * Benchimol, Alex. (2016) ''Intellectual Politics and Cultural Conflict in the Romantic Period: Scottish Whigs, English Radicals and the Making of the British Public Sphere'' (London: Routledge). * Benda, Julien (2003). ''The Treason of the Intellectuals.'' New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. * Camp, Roderic (1985). ''Intellectuals and the State in Twentieth-Century Mexico.'' Austin: University of Texas Press. * Coleman, Peter (2010) ''The Last Intellectuals.'' Sydney: Quadrant Books. * Di Leo, Jeffrey R., and Peter Hitchcock, eds. (2016) ''The New Public Intellectual: Politics, Theory, and the Public Sphere''. (Springer). * Finkielkraut, Alain (1995). ''The Defeat of the Mind.'' Columbia University Press. * Gella, Aleksander, Ed., (1976). ''The Intelligentsia and the Intellectuals.'' California: Sage Publication. * Gouldner, Alvin W. (1979)

''The Future of the Intellectuals and the Rise of the New Class.''

New York: The Seabury Press. * Gross, John (1969). ''The Rise and Fall of the Man of Letters''. New York: Macmillan. * Huszar, George B. de, ed., (1960). ''The Intellectuals: A Controversial Portrait''. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press. Anthology with many contributors. * Johnson, Paul (1990). ''Intellectuals''. New York: Harper Perennial . Highly ideological criticisms of Rousseau, Shelley,

online review

* Konrad, George ''et al''. (1979). ''The Intellectuals On The Road To Class Power.'' Sussex: Harvester Press. * Lasch, Christopher (1997). ''The New Radicalism in America, 1889–1963: The Intellectual as a Social Type.'' New York: W.W. Norton & Co. * Lemert, Charles (1991). ''Intellectuals and Politics.'' Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications. * McCaughan, Michael (2000). ''True Crime: Rodolfo Walsh and the Role of the Intellectual in Latin American Politics.'' Latin America Bureau . * Michael, John (2000). ''Anxious Intellects: Academic Professionals, Public Intellectuals, and Enlightenment Values.'' Duke University Press. * Misztal, Barbara A. (2007). ''Intellectuals and the Public Good.'' Cambridge University Press. * Moebius, Stephan. Intellektuellensoziologie: Skizze einer Methodologie. In: Sozial.Geschichte Online. H. 2 (2010), S. 37–63, hier S. 42 (PDF; 173 kB). * Molnar, Thomas (1961)

''The Decline of the Intellectual.''

Cleveland: The World Publishing Company. * Piereson, James (2006)

''The New Criterion'', Vol. XXV, p. 52. * Posner, Richard A. (2002). ''Public Intellectuals: A Study of Decline.'' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press . * Rieff, Philip, Ed., (1969)

''On Intellectuals''

New York: Doubleday & Co. * Sawyer, S., and Iain Stewart, eds. (2016) ''In Search of the Liberal Moment: Democracy, Anti-totalitarianism, and Intellectual Politics in France since 1950'' (Springer). * Showalter, Elaine (2001). ''Inventing Herself: Claiming A Feminist Intellectual Heritage.'' London: Picador. * Viereck, Peter (1953). ''Shame and Glory of the Intellectuals.'' Boston: Beacon Press.

"Do Public Intellectuals Matter?,"

''Prospect Magazine,'' No. 206. * Hamburger, Joseph (1966). ''Intellectuals in Politics.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. * Hayek, F.A. (1949). "The Intellectuals and Socialism," ''The University of Chicago Law Review,'' Vol. XVI, No. 3, pp. 417–433. * Huizinga, Johan (1936). ''In the Shadows of Tomorrow.'' New York: W.W. Norton & Company. * Kidder, David S., Oppenheim, Noah D., (2006). '' The Intellectual Devotional.'' Emmaus, Pennsylvania: Rodale Books . * Laruelle, François (2014). ''Intellectuals and Power.'' Cambridge: Polity Press. * Lilla, Mark (2003). ''The Reckless Mind – Intellectuals in Politics.'' New York: New York Review Books. * Lukacs, John A. (1958). "Intellectuals, Catholics, and the Intellectual Life," ''Modern Age,'' Vol. II, No. 1, pp. 40–53. * MacDonald, Heather (2001). ''The Burden of Bad Ideas.'' New York: Ivan R. Dee. * Milosz, Czeslaw (1990). '' The Captive Mind.'' New York: Vintage Books. * Molnar, Thomas (1958). "Intellectuals, Experts, and the Classless Society," ''Modern Age,'' Vol. II, No. 1, pp. 33–39. * Moses, A. Dirk (2009) ''German Intellectuals and the Nazi Past.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Rothbard, Murray N. (1989). "World War I as Fulfillment: Power and the Intellectuals," ''The Journal of Libertarian Studies,'' Vol. IX, No. 1, pp. 81–125. * Sapiro, Gisèle. (2014). ''The French Writers' War 1940–1953'' (1999; English edition 2014); highly influential study of intellectuals in the French Resistanc

online review

* Shapiro, J. Salwyn (1920)

"The Revolutionary Intellectual,"

''The Atlantic Monthly,'' Vol. CXXV, pp. 320–330. * Shenfield, Arthur A. (1970). "The Ugly Intellectual," ''The Modern Age'', Vol. XVI, No. 1, pp. 9–14. * Shlapentokh, Vladimir (1990) ''Soviet Intellectuals and Political Power.'' Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. * Shore, Marci (2009). ''Caviar and Ashes.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. * Small, Helen (2002). ''The Public Intellectual.'' Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. * Strunsky, Simeon (1921)

"Intellectuals and Highbrows,"Part II

''Vanity Fair'', Vol. XV, pp. 52, 92. * Whittington-Egan, Richard (2003-08-01). ''"The Vanishing Man of Letters: Part One"''. Contemporary Review. * Whittington-Egan, Richard (2003-10-01). ''"The Vanishing Man of Letters: Part Two"''. Contemporary Review. * Wolin, Richard (2010). ''The Wind from the East: French Intellectuals, the Culture Revolution and the Legacy of the 1960s.'' Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

The Responsibility of Intellectuals

by

"The Optimist's Book Club"

''The New Haven Advocate''—discussion of public intellectuals in the 21st century. {{authority control 1810s neologisms Academia Intellectual history Lord Byron Occupations Positions of authority Social classes Sociology of culture Stereotypes Thought

An intellectual is a person who engages in

An intellectual is a person who engages in critical thinking

Critical thinking is the process of analyzing available facts, evidence, observations, and arguments to make sound conclusions or informed choices. It involves recognizing underlying assumptions, providing justifications for ideas and actions, ...

, research

Research is creative and systematic work undertaken to increase the stock of knowledge. It involves the collection, organization, and analysis of evidence to increase understanding of a topic, characterized by a particular attentiveness to ...

, and reflection about the nature of reality

Reality is the sum or aggregate of everything in existence; everything that is not imagination, imaginary. Different Culture, cultures and Academic discipline, academic disciplines conceptualize it in various ways.

Philosophical questions abo ...

, especially the nature of society and proposed solutions for its normative

Normativity is the phenomenon in human societies of designating some actions or outcomes as good, desirable, or permissible, and others as bad, undesirable, or impermissible. A Norm (philosophy), norm in this sense means a standard for evaluatin ...

problems. Coming from the world of culture

Culture ( ) is a concept that encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and Social norm, norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, Social norm, customs, capabilities, Attitude (psychology), attitudes ...

, either as a creator or as a mediator, the intellectual participates in politics, either to defend a concrete proposition or to denounce an injustice, usually by either rejecting, producing or extending an ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

, and by defending a system of values

In ethics and social sciences, value denotes the degree of importance of some thing or action, with the aim of determining which actions are best to do or what way is best to live ( normative ethics), or to describe the significance of different a ...

.

Etymological background

"Man of letters"

The term "man of letters" derives from the French term '' belletrist'' or ''homme de lettres'' but is not synonymous with "an academic". A "man of letters" was a literate man, able to read and write, and thus highly valued in the upper strata of society in a time whenliteracy

Literacy is the ability to read and write, while illiteracy refers to an inability to read and write. Some researchers suggest that the study of "literacy" as a concept can be divided into two periods: the period before 1950, when literacy was ...

was rare. In the 17th and 18th centuries, the term ''Belletrist(s)'' came to be applied to the ''literati'': the French participants in—sometimes referred to as "citizens" of—the Republic of Letters

The Republic of Letters (''Res Publica Litterarum'' or ''Res Publica Literaria'') was the long-distance intellectual community in the late 17th and 18th centuries in Europe and the Americas. It fostered communication among the intellectuals of th ...

, which evolved into the salon

Salon may refer to:

Common meanings

* Beauty salon

A beauty salon or beauty parlor is an establishment that provides Cosmetics, cosmetic treatments for people. Other variations of this type of business include hair salons, spas, day spas, ...

, a social institution, usually run by a hostess, meant for the edification, education, and cultural refinement of the participants.

In the late 19th century, when literacy was relatively common in European countries such as the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Northwestern Europe, off the coast of European mainland, the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotlan ...

, the "Man of Letters" (''littérateur'') denotation broadened to mean "specialized", a man who earned his living writing intellectually (not creatively) about literature: the essay

An essay ( ) is, generally, a piece of writing that gives the author's own argument, but the definition is vague, overlapping with those of a Letter (message), letter, a term paper, paper, an article (publishing), article, a pamphlet, and a s ...

ist, the journalist

A journalist is a person who gathers information in the form of text, audio or pictures, processes it into a newsworthy form and disseminates it to the public. This is called journalism.

Roles

Journalists can work in broadcast, print, advertis ...

, the critic

A critic is a person who communicates an assessment and an opinion of various forms of creative works such as Art criticism, art, Literary criticism, literature, Music journalism, music, Film criticism, cinema, Theater criticism, theater, Fas ...

, et al. Examples include Samuel Johnson

Samuel Johnson ( – 13 December 1784), often called Dr Johnson, was an English writer who made lasting contributions as a poet, playwright, essayist, moralist, literary critic, sermonist, biographer, editor, and lexicographer. The ''Oxford ...

, Walter Scott

Sir Walter Scott, 1st Baronet (15 August 1771 – 21 September 1832), was a Scottish novelist, poet and historian. Many of his works remain classics of European literature, European and Scottish literature, notably the novels ''Ivanhoe'' (18 ...

and Thomas Carlyle

Thomas Carlyle (4 December 17955 February 1881) was a Scottish essayist, historian, and philosopher. Known as the "Sage writing, sage of Chelsea, London, Chelsea", his writings strongly influenced the intellectual and artistic culture of the V ...

. In the 20th century, such an approach was gradually superseded by the academic method, and the term "Man of Letters" became disused, replaced by the generic term "intellectual", describing the intellectual person. The archaic term is the basis of the names of several academic institutions which call themselves Colleges of Letters and Science.

"Intellectual"

The earliest record of the English noun "intellectual" is found in the 19th century, where in 1813,Byron

George Gordon Byron, 6th Baron Byron (22 January 1788 – 19 April 1824) was an English poet. He is one of the major figures of the Romantic movement, and is regarded as being among the greatest poets of the United Kingdom. Among his best-kno ...

reports that 'I wish I may be well enough to listen to these intellectuals'. Over the course of the 19th century, other variants of the already established adjective 'intellectual' as a noun appeared in English and in French, where in the 1890s the noun () formed from the adjective appeared with higher frequency in the literature.

Collini writes about this time that " ong this cluster of linguistic experiments there occurred ... the occasional usage of 'intellectuals' as a plural noun to refer, usually with a figurative or ironic intent, to a collection of people who might be identified in terms of their intellectual inclinations or pretensions."

In early 19th-century Britain, Samuel Taylor Coleridge

Samuel Taylor Coleridge ( ; 21 October 177225 July 1834) was an English poet, literary critic, philosopher, and theologian who was a founder of the Romantic Movement in England and a member of the Lake Poets with his friend William Wordsworth ...

coined the term ''clerisy'', the intellectual class responsible for upholding and maintaining the national culture, the secular equivalent of the Anglican clergy. Likewise, in Tsar

Tsar (; also spelled ''czar'', ''tzar'', or ''csar''; ; ; sr-Cyrl-Latn, цар, car) is a title historically used by Slavic monarchs. The term is derived from the Latin word '' caesar'', which was intended to mean ''emperor'' in the Euro ...

ist Russia, there arose the ''intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

'' (1860s–1870s), who were the status class of white-collar workers.

For Germany, the theologian Alister McGrath

Alister Edgar McGrath (; born 1953) is an Irish theologian, Anglican priest, intellectual historian, scientist, Christian apologist, and public intellectual. He currently holds the Andreas Idreos Professorship in Science and Religion in the F ...

said that "the emergence of a socially alienated, theologically literate, antiestablishment lay intelligentsia is one of the more significant phenomena of the social history of Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany, is a country in Central Europe. It lies between the Baltic Sea and the North Sea to the north and the Alps to the south. Its sixteen States of Germany, constituent states have a total popu ...

in the 1830s". An intellectual class in Europe was socially important, especially to self-styled intellectuals, whose participation in society's arts, politics, journalism, and education—of either nationalist

Nationalism is an idea or movement that holds that the nation should be congruent with the State (polity), state. As a movement, it presupposes the existence and tends to promote the interests of a particular nation,Anthony D. Smith, Smith, A ...

, internationalist, or ethnic sentiment—constitute "vocation of the intellectual". Moreover, some intellectuals were anti-academic, despite universities (the academy) being synonymous with intellectualism

Intellectualism is the mental perspective that emphasizes the use, development, and exercise of the intellect, and is identified with the life of the mind of the intellectual. (Definition) In the field of philosophy, the term ''intellectualism'' in ...

.

In France, the Dreyfus affair (1894–1906), an identity crisis of antisemitic nationalism for the French Third Republic

The French Third Republic (, sometimes written as ) was the system of government adopted in France from 4 September 1870, when the Second French Empire collapsed during the Franco-Prussian War, until 10 July 1940, after the Fall of France durin ...

(1870–1940), marked the full emergence of the "intellectual in public life", especially Émile Zola, Octave Mirbeau and Anatole France

(; born ; 16 April 1844 – 12 October 1924) was a French poet, journalist, and novelist with several best-sellers. Ironic and skeptical, he was considered in his day the ideal French man of letters.antisemitism

Antisemitism or Jew-hatred is hostility to, prejudice towards, or discrimination against Jews. A person who harbours it is called an antisemite. Whether antisemitism is considered a form of racism depends on the school of thought. Antisemi ...

to the public; thenceforward, "intellectual" became common, yet initially derogatory, usage; its French noun usage is attributed to Georges Clemenceau in 1898. Nevertheless, by 1930 the term "intellectual" passed from its earlier pejorative associations and restricted usages to a widely accepted term and it was because of the Dreyfus Affair that the term also acquired generally accepted use in English.

In the 20th century, the term intellectual acquired positive connotations of social prestige, derived from possessing intellect

Intellect is a faculty of the human mind that enables reasoning, abstraction, conceptualization, and judgment. It enables the discernment of truth and falsehood, as well as higher-order thinking beyond immediate perception. Intellect is dis ...

and intelligence

Intelligence has been defined in many ways: the capacity for abstraction, logic, understanding, self-awareness, learning, emotional knowledge, reasoning, planning, creativity, critical thinking, and problem-solving. It can be described as t ...

, especially when the intellectual's activities exerted positive consequences in the public sphere

The public sphere () is an area in social relation, social life where individuals can come together to freely discuss and identify societal problems, and through that discussion, Social influence, influence political action. A "Public" is "of or c ...

and so increased the intellectual understanding of the public, by means of moral

A moral (from Latin ''morālis'') is a message that is conveyed or a lesson to be learned from a story or event. The moral may be left to the hearer, reader, or viewer to determine for themselves, or may be explicitly encapsulated in a maxim. ...

responsibility, altruism

Altruism is the concern for the well-being of others, independently of personal benefit or reciprocity.

The word ''altruism'' was popularised (and possibly coined) by the French philosopher Auguste Comte in French, as , for an antonym of egoi ...

, and solidarity

Solidarity or solidarism is an awareness of shared interests, objectives, standards, and sympathies creating a psychological sense of unity of groups or classes. True solidarity means moving beyond individual identities and single issue politics ...

, without resorting to the manipulations of demagoguery

A demagogue (; ; ), or rabble-rouser, is a political leader in a democracy who gains popularity by arousing the common people against elites, especially through oratory that whips up the passions of crowds, Appeal to emotion, appealing to emo ...

, paternalism and incivility

Incivility is a general term for social behaviour lacking in civility or good manners, on a scale from rudeness or lack of respect for elders, to vandalism and hooliganism, through public drunkenness and threatening behaviour. The word "in ...

(condescension). The sociologist Frank Furedi

Frank Furedi (; born 3 May 1947) is a Hungarian Canadians, Hungarian-Canadian academic and emeritus professor of sociology at the University of Kent. He is well known for his work on culture of fear, sociology of fear, education, therapy culture ...

said that "Intellectuals are not defined according to the jobs they do, but ythe manner in which they act, the way they see themselves, and the ocial and politicalvalues that they uphold.

According to Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell ( ; born June 30, 1930) is an American economist, economic historian, and social and political commentator. He is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. With widely published commentary and books—and as a guest on T ...

, as a descriptive term of person, personality, and profession, the word ''intellectual'' identifies three traits:

# Educated; erudition for developing theories;

# Productive; creates cultural capital

In the field of sociology, cultural capital comprises the social assets of a person (education, intellect, style of speech, style of dress, social capital, etc.) that promote social mobility in a stratified society. Cultural capital functions as ...

in the fields of philosophy, literary criticism

A genre of arts criticism, literary criticism or literary studies is the study, evaluation, and interpretation of literature. Modern literary criticism is often influenced by literary theory, which is the philosophical analysis of literature's ...

, and sociology

Sociology is the scientific study of human society that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. The term sociol ...

, law, medicine, and science, etc.; and

# Artist

An artist is a person engaged in an activity related to creating art, practicing the arts, or demonstrating the work of art. The most common usage (in both everyday speech and academic discourse) refers to a practitioner in the visual arts o ...

ic; creates art in literature

Literature is any collection of Writing, written work, but it is also used more narrowly for writings specifically considered to be an art form, especially novels, Play (theatre), plays, and poetry, poems. It includes both print and Electroni ...

, music

Music is the arrangement of sound to create some combination of Musical form, form, harmony, melody, rhythm, or otherwise Musical expression, expressive content. Music is generally agreed to be a cultural universal that is present in all hum ...

, painting

Painting is a Visual arts, visual art, which is characterized by the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called "matrix" or "Support (art), support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with ...

, sculpture

Sculpture is the branch of the visual arts that operates in three dimensions. Sculpture is the three-dimensional art work which is physically presented in the dimensions of height, width and depth. It is one of the plastic arts. Durable sc ...

, etc.

Historical uses

InLatin

Latin ( or ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally spoken by the Latins (Italic tribe), Latins in Latium (now known as Lazio), the lower Tiber area aroun ...

, at least starting from the Carolingian Empire

The Carolingian Empire (800–887) was a Franks, Frankish-dominated empire in Western and Central Europe during the Early Middle Ages. It was ruled by the Carolingian dynasty, which had ruled as List of Frankish kings, kings of the Franks since ...

, intellectuals could be called ''litterati'', a term which is sometimes applied today.

The word intellectual is found in Indian scripture Mahabharata

The ''Mahābhārata'' ( ; , , ) is one of the two major Sanskrit Indian epic poetry, epics of ancient India revered as Smriti texts in Hinduism, the other being the ''Ramayana, Rāmāyaṇa''. It narrates the events and aftermath of the Kuru ...

in the Bachelorette meeting (Swayamvara Sava) of Draupadi

Draupadi (), also referred to as Krishnā, Panchali and Yajnaseni, is the central heroine of the Indian epic poetry, ancient Indian epic ''Mahabharata''. In the epic, she is the princess of Panchala Kingdom, who later becomes the empress of K ...

. Immediately after Arjuna and Raja-Maharaja (kings-emperors) came to the meeting, ''Nipuna Buddhijibina (perfect intellectuals)'' appeared at the meeting.

In Imperial China

The history of China spans several millennia across a wide geographical area. Each region now considered part of the Chinese world has experienced periods of unity, fracture, prosperity, and strife. Chinese civilization first emerged in the Y ...

in the period from 206 BC until AD 1912, the intellectuals were the ''Scholar-official

The scholar-officials, also known as literati, scholar-gentlemen or scholar-bureaucrats (), were government officials and prestigious scholars in Chinese society, forming a distinct social class.

Scholar-officials were politicians and governmen ...

s'' ("Scholar-gentlemen"), who were civil servants appointed by the Emperor of China to perform the tasks of daily governance. Such civil servants earned academic degrees by means of imperial examination

The imperial examination was a civil service examination system in History of China#Imperial China, Imperial China administered for the purpose of selecting candidates for the Civil service#China, state bureaucracy. The concept of choosing bureau ...

, and were often also skilled calligraphers or Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China, and is variously described as a tradition, philosophy, religion, theory of government, or way of life. Founded by Confucius ...

philosophers. Historian Wing-Tsit Chan concludes that:

In Joseon Korea (1392–1910), the intellectuals were the ''literati'', who knew how to read and write, and had been designated, as the chungin (the "middle people"), in accordance with the Confucian system. Socially, they constituted the petite bourgeoisie

''Petite bourgeoisie'' (, ; also anglicised as petty bourgeoisie) is a term that refers to a social class composed of small business owners, shopkeepers, small-scale merchants, semi- autonomous peasants, and artisans. They are named as s ...

, composed of scholar-bureaucrats (scholars, professionals, and technicians) who administered the dynastic rule of the Joseon dynasty.

Public intellectual

The term ''public intellectual'' describes the intellectual participating in the public-affairsdiscourse

Discourse is a generalization of the notion of a conversation to any form of communication. Discourse is a major topic in social theory, with work spanning fields such as sociology, anthropology, continental philosophy, and discourse analysis. F ...

of society, in addition to an academic career. Regardless of their academic

An academy (Attic Greek: Ἀκαδήμεια; Koine Greek Ἀκαδημία) is an institution of tertiary education. The name traces back to Plato's school of philosophy, founded approximately 386 BC at Akademia, a sanctuary of Athena, the go ...

fields or profession

A profession is a field of Work (human activity), work that has been successfully professionalized. It can be defined as a disciplined group of individuals, professionals, who adhere to ethical standards and who hold themselves out as, and are ...

al expertise, public intellectuals address and respond to the normative

Normativity is the phenomenon in human societies of designating some actions or outcomes as good, desirable, or permissible, and others as bad, undesirable, or impermissible. A Norm (philosophy), norm in this sense means a standard for evaluatin ...

problems of society, and, as such, are expected to be impartial critics who can "rise above the partial preoccupation of one's own profession—and engage with the global issues of truth

Truth or verity is the Property (philosophy), property of being in accord with fact or reality.Merriam-Webster's Online Dictionarytruth, 2005 In everyday language, it is typically ascribed to things that aim to represent reality or otherwise cor ...

, judgment, and taste

The gustatory system or sense of taste is the sensory system that is partially responsible for the perception of taste. Taste is the perception stimulated when a substance in the mouth biochemistry, reacts chemically with taste receptor cells l ...

of the time". In ''Representations of the Intellectual'' (1994), Edward Saïd said that the "true intellectual is, therefore, always an outsider, living in self-imposed exile, and on the margins of society". Public intellectuals usually arise from the educated élite of a society, although the North American usage of the term ''intellectual'' includes the university academics. The difference between ''intellectual'' and ''academic'' is participation in the realm of public affairs.

Jürgen Habermas

Jürgen Habermas ( , ; ; born 18 June 1929) is a German philosopher and social theorist in the tradition of critical theory and pragmatism. His work addresses communicative rationality and the public sphere.

Associated with the Frankfurt S ...

' ''The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere'' (1963) made significant contribution to the notion of public intellectual by historically and conceptually delineating the idea of private and public. Controversial, in the same year, was Ralf Dahrendorf's definition: "As the court-jester

A jester, also known as joker, court jester, or fool, was a member of the household of a nobleman or a monarch kept to entertain guests at the royal court. Jesters were also travelling performers who entertained common folk at fairs and town ma ...

s of modern society, all intellectuals have the duty to doubt everything that is obvious, to make relative all authority, to ask all those questions that no one else dares to ask".

An intellectual usually is associated with an ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

or with a philosophy

Philosophy ('love of wisdom' in Ancient Greek) is a systematic study of general and fundamental questions concerning topics like existence, reason, knowledge, Value (ethics and social sciences), value, mind, and language. It is a rational an ...

. The Czech intellectual Václav Havel

Václav Havel (; 5 October 193618 December 2011) was a Czech statesman, author, poet, playwright, and dissident. Havel served as the last List of presidents of Czechoslovakia, president of Czechoslovakia from 1989 until 1992, prior to the dissol ...

said that politics and intellectuals can be linked, but that moral responsibility for the intellectual's ideas, even when advocated by a politician, remains with the intellectual. Therefore, it is best to avoid utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

n intellectuals who offer 'universal insights' to resolve the problems of political economy

Political or comparative economy is a branch of political science and economics studying economic systems (e.g. Marketplace, markets and national economies) and their governance by political systems (e.g. law, institutions, and government). Wi ...

with public policies that might harm and that have harmed civil society; that intellectuals be mindful of the social and cultural ties created with their words, insights and ideas; and should be heard as social critics of politics

Politics () is the set of activities that are associated with decision-making, making decisions in social group, groups, or other forms of power (social and political), power relations among individuals, such as the distribution of Social sta ...

and power.

Public engagement

The determining factor for a "thinker" (historian, philosopher, scientist, writer, artist) to be considered a public intellectual is the degree to which the individual is implicated and engaged with the vital reality of the contemporary world, i.e. participation in the public affairs of society. Consequently, being designated as a public intellectual is determined by the degree of influence of the designator'smotivation

Motivation is an mental state, internal state that propels individuals to engage in goal-directed behavior. It is often understood as a force that explains why people or animals initiate, continue, or terminate a certain behavior at a particul ...

s, opinions, and options of action (social, political, ideological), and by affinity with the given thinker.

After the failure of the large-scale May 68 movement in France, intellectuals within the country were often maligned for having specific areas of expertise while discussing general subjects like democracy. Intellectuals increasingly claimed to be within marginalized groups rather than their spokespeople, and centered their activism on the social problems relevant to their areas of expertise (such as gender relations in the case of psychologists). A similar shift occurred in China after the Tiananmen Square Massacre from the "universal intellectual" (who plans better futures from within academia) to ''minjian'' ("grassroots") intellectuals, the latter group represented by such figures as Wang Xiaobo, social scientist Yu Jianrong, and '' Yanhuang Chunqiu'' editor Ding Dong ().

Public policy

In the matters ofpublic policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a Group decision-making, decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to Problem solving, solve or address relevant and problematic social issues, guided by a conceptio ...

, the public intellectual connects scholarly research to the practical matters of solving societal problems. The British sociologist Michael Burawoy, an exponent of public sociology, said that professional sociology has failed by giving insufficient attention to resolving social problems, and that a dialogue between the academic and the layman would bridge the gap. An example is how Chile

Chile, officially the Republic of Chile, is a country in western South America. It is the southernmost country in the world and the closest to Antarctica, stretching along a narrow strip of land between the Andes, Andes Mountains and the Paci ...

an intellectuals worked to reestablish democracy

Democracy (from , ''dēmos'' 'people' and ''kratos'' 'rule') is a form of government in which political power is vested in the people or the population of a state. Under a minimalist definition of democracy, rulers are elected through competitiv ...

within the right-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

, neoliberal

Neoliberalism is a political and economic ideology that advocates for free-market capitalism, which became dominant in policy-making from the late 20th century onward. The term has multiple, competing definitions, and is most often used pej ...

governments of the military dictatorship of 1973–1990, the Pinochet régime allowed professional opportunities for some liberal and left-wing social scientists to work as politicians and as consultants in effort to realize the theoretical economics of the Chicago Boys, but their access to power was contingent upon political pragmatism

Pragmatism is a philosophical tradition that views language and thought as tools for prediction, problem solving, and action, rather than describing, representing, or mirroring reality. Pragmatists contend that most philosophical topics� ...

, abandoning the political neutrality of the academic intellectual.

In '' The Sociological Imagination'' (1959), C. Wright Mills

Charles Wright Mills (August 28, 1916 – March 20, 1962) was an American Sociology, sociologist, and a professor of sociology at Columbia University from 1946 until his death in 1962. Mills published widely in both popular and intellectual jour ...

said that academics had become ill-equipped for participating in public discourse, and that journalists usually are "more politically alert and knowledgeable than sociologists, economists, and especially ... political scientists". That, because the universities of the U.S. are bureaucratic, private businesses, they "do not teach critical reasoning to the student", who then does not know "how to gauge what is going on in the general struggle for power in modern society". Likewise, Richard Rorty criticized the quality of participation of intellectuals in public discourse as an example of the "civic irresponsibility of intellect

Intellect is a faculty of the human mind that enables reasoning, abstraction, conceptualization, and judgment. It enables the discernment of truth and falsehood, as well as higher-order thinking beyond immediate perception. Intellect is dis ...

, especially academic intellect".

The American legal scholar Richard Posner

Richard Allen Posner (; born January 11, 1939) is an American legal scholar and retired United States circuit judge who served on the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Seventh Circuit from 1981 to 2017. A senior lecturer at the University of Chicag ...

said that the participation of academic public intellectuals in the public life of society is characterized by logically untidy and politically biased statements of the kind that would be unacceptable to academia. He concluded that there are few ideologically and politically independent public intellectuals, and disapproved public intellectuals who limit themselves to practical matters of public policy, and not with values

In ethics and social sciences, value denotes the degree of importance of some thing or action, with the aim of determining which actions are best to do or what way is best to live ( normative ethics), or to describe the significance of different a ...

or public philosophy, or public ethics

Ethics is the philosophy, philosophical study of Morality, moral phenomena. Also called moral philosophy, it investigates Normativity, normative questions about what people ought to do or which behavior is morally right. Its main branches inclu ...

, or public theology, nor with matters of moral and spiritual outrage.

Intellectual status class

Socially, intellectuals constitute theintelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

, a status class organised either by ideology

An ideology is a set of beliefs or values attributed to a person or group of persons, especially those held for reasons that are not purely about belief in certain knowledge, in which "practical elements are as prominent as theoretical ones". Form ...

(e.g., conservatism

Conservatism is a Philosophy of culture, cultural, Social philosophy, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, Convention (norm), customs, and Value (ethics and social science ...

, fascism

Fascism ( ) is a far-right, authoritarian, and ultranationalist political ideology and movement. It is characterized by a dictatorial leader, centralized autocracy, militarism, forcible suppression of opposition, belief in a natural social hie ...

, socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

, liberalism

Liberalism is a Political philosophy, political and moral philosophy based on the Individual rights, rights of the individual, liberty, consent of the governed, political equality, the right to private property, and equality before the law. ...

, reactionary

In politics, a reactionary is a person who favors a return to a previous state of society which they believe possessed positive characteristics absent from contemporary.''The New Fontana Dictionary of Modern Thought'' Third Edition, (1999) p. 729. ...

, revolutionary

A revolutionary is a person who either participates in, or advocates for, a revolution. The term ''revolutionary'' can also be used as an adjective to describe something producing a major and sudden impact on society.

Definition

The term—bot ...

, democratic, communism

Communism () is a political sociology, sociopolitical, political philosophy, philosophical, and economic ideology, economic ideology within the history of socialism, socialist movement, whose goal is the creation of a communist society, a ...

), or by nationality (American intellectuals, French intellectuals, Ibero–American intellectuals, ''et al.''). The term ''intelligentsiya'' originated from Tsarist Russia (–1870s), where it denotes the social stratum of those possessing intellectual formation (schooling, education), and who were Russian society's counterpart to the German '' Bildungsbürgertum'' and to the French ''bourgeoisie éclairée'', the enlightened middle classes of those realms.Williams, Raymond. ''Keywords: A Vocabulary of Culture and Society'' (1983)

In Marxist philosophy

Marxist philosophy or Marxist theory are works in philosophy that are strongly influenced by Karl Marx's Historical materialism, materialist approach to theory, or works written by Marxists. Marxist philosophy may be broadly divided into Wester ...

, the social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

function of the intellectuals (the intelligentsia

The intelligentsia is a status class composed of the university-educated people of a society who engage in the complex mental labours by which they critique, shape, and lead in the politics, policies, and culture of their society; as such, the i ...

) is to be the source of progressive ideas for the transformation of society: providing advice and counsel to the political leaders, interpreting the country's politics to the mass of the population (urban workers and peasants). In the pamphlet '' What Is to Be Done?'' (1902), Vladimir Lenin

Vladimir Ilyich Ulyanov ( 187021 January 1924), better known as Vladimir Lenin, was a Russian revolutionary, politician and political theorist. He was the first head of government of Soviet Russia from 1917 until Death and state funeral of ...

(1870–1924) said that vanguard-party revolution required the participation of the intellectuals to explain the complexities of socialist

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

ideology to the uneducated proletariat

The proletariat (; ) is the social class of wage-earners, those members of a society whose possession of significant economic value is their labour power (their capacity to work). A member of such a class is a proletarian or a . Marxist ph ...

and the urban industrial workers in order to integrate them to the revolution because "the history of all countries shows that the working class, exclusively by its own efforts, is able to develop only trade-union consciousness" and will settle for the limited, socio-economic gains so achieved. In Russia as in Continental Europe

Continental Europe or mainland Europe is the contiguous mainland of Europe, excluding its surrounding islands. It can also be referred to ambiguously as the European continent, – which can conversely mean the whole of Europe – and, by som ...

, socialist theory was the product of the "educated representatives of the propertied classes", of "revolutionary socialist intellectuals", such as were Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ;"Engels"

''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.György Lukács György Lukács (born Bernát György Löwinger; ; ; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and Aesthetics, aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an inter ...

(1885–1971) identified the intelligentsia as the privileged social class who provide revolutionary leadership. By means of intelligible and accessible interpretation, the intellectuals explain to the workers and peasants the "Who?", the "How?" and the "Why?" of the social, economic and political ''''Random House Webster's Unabridged Dictionary''.György Lukács György Lukács (born Bernát György Löwinger; ; ; 13 April 1885 – 4 June 1971) was a Hungarian Marxist philosopher, literary historian, literary critic, and Aesthetics, aesthetician. He was one of the founders of Western Marxism, an inter ...

status quo

is a Latin phrase meaning the existing state of affairs, particularly with regard to social, economic, legal, environmental, political, religious, scientific or military issues. In the sociological sense, the ''status quo'' refers to the curren ...

''—the ideological totality of society—and its practical, revolutionary application to the transformation of their society.

The Italian communist theoretician Antonio Gramsci

Antonio Francesco Gramsci ( , ; ; 22 January 1891 – 27 April 1937) was an Italian Marxist philosophy, Marxist philosopher, Linguistics, linguist, journalist, writer, and politician. He wrote on philosophy, Political philosophy, political the ...

(1891–1937) developed Karl Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

's conception of the intelligentsia to include political leadership in the public sphere. That because "all knowledge is existentially-based", the intellectuals, who create and preserve knowledge, are "spokesmen for different social groups, and articulate particular social interests". That intellectuals occur in each social class and throughout the right-wing

Right-wing politics is the range of political ideologies that view certain social orders and hierarchies as inevitable, natural, normal, or desirable, typically supporting this position based on natural law, economics, authority, property ...

, the centre and the left-wing

Left-wing politics describes the range of Ideology#Political ideologies, political ideologies that support and seek to achieve social equality and egalitarianism, often in opposition to social hierarchy either as a whole or of certain social ...

of the political spectrum

A political spectrum is a system to characterize and classify different Politics, political positions in relation to one another. These positions sit upon one or more Geometry, geometric Coordinate axis, axes that represent independent political ...

and that as a social class the "intellectuals view themselves as autonomous from the ruling class

In sociology, the ruling class of a society is the social class who set and decide the political and economic agenda of society.

In Marxist philosophy, the ruling class are the class who own the means of production in a given society and apply ...

" of their society.

Addressing their role as a social class, Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

said that intellectuals are the moral conscience of their age; that their moral and ethical responsibilities are to observe the socio-political moment, and to freely speak to their society, in accordance with their consciences.

The British historian Norman Stone said that the intellectual social class

A social class or social stratum is a grouping of people into a set of Dominance hierarchy, hierarchical social categories, the most common being the working class and the Bourgeoisie, capitalist class. Membership of a social class can for exam ...

misunderstand the reality of society and so are doomed to the errors of logical fallacy

In logic and philosophy, a formal fallacy is a pattern of reasoning rendered invalid by a flaw in its logical structure. Propositional logic, for example, is concerned with the meanings of sentences and the relationships between them. It focuses ...

, ideological stupidity, and poor planning hampered by ideology. In her memoirs, the Conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

politician Margaret Thatcher

Margaret Hilda Thatcher, Baroness Thatcher (; 13 October 19258 April 2013), was a British stateswoman who served as Prime Minister of the United Kingdom from 1979 to 1990 and Leader of the Conservative Party (UK), Leader of th ...

wrote that the anti-monarchical French Revolution (1789–1799) was "a utopia

A utopia ( ) typically describes an imagined community or society that possesses highly desirable or near-perfect qualities for its members. It was coined by Sir Thomas More for his 1516 book ''Utopia (book), Utopia'', which describes a fictiona ...

n attempt to overthrow a traditional order ..in the name of abstract ideas, formulated by vain intellectuals".

Latin America

The American academic Peter H. Smith describes the intellectuals of Latin America as people from an identifiable social class, who have been conditioned by that common experience and thus are inclined to share a set of common assumptions (values and ethics); that ninety-four per cent of intellectuals come either from themiddle class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. C ...

or from the upper class

Upper class in modern societies is the social class composed of people who hold the highest social status. Usually, these are the wealthiest members of class society, and wield the greatest political power. According to this view, the upper cla ...

and that only six per cent come from the working class

The working class is a subset of employees who are compensated with wage or salary-based contracts, whose exact membership varies from definition to definition. Members of the working class rely primarily upon earnings from wage labour. Most c ...

.

Philosopher Steven Fuller said that because cultural capital

In the field of sociology, cultural capital comprises the social assets of a person (education, intellect, style of speech, style of dress, social capital, etc.) that promote social mobility in a stratified society. Cultural capital functions as ...

confers power and social status as a status group they must be autonomous in order to be credible as intellectuals:

United States

The 19th-century U.S.

The 19th-century U.S. Congregational

Congregationalism (also Congregational Churches or Congregationalist Churches) is a Reformed Christianity, Reformed Christian (Calvinist) tradition of Protestant Christianity in which churches practice Congregationalist polity, congregational ...

theologian Edwards Amasa Park said: "We do wrong to our own minds, when we carry out scientific difficulties down to the arena of popular dissension". In his view, it was necessary for the sake of social, economic and political stability "to separate the serious, technical role of professionals from their responsibility orsupplying usable philosophies for the general public". This expresses a dichotomy, derived from Plato, between public knowledge and private knowledge, "civic culture" and "professional culture", the intellectual sphere of life and the life of ordinary people in society.

In the United States, members of the intellectual status class have been demographic

Demography () is the statistics, statistical study of human populations: their size, composition (e.g., ethnic group, age), and how they change through the interplay of fertility (births), mortality (deaths), and migration.

Demographic analy ...

ally characterized as people who hold liberal-to- leftist political perspectives about guns-or-butter fiscal policy

In economics and political science, fiscal policy is the use of government revenue collection ( taxes or tax cuts) and expenditure to influence a country's economy. The use of government revenue expenditures to influence macroeconomic variab ...

.

In "The Intellectuals and Socialism" (1949), Friedrich Hayek

Friedrich August von Hayek (8 May 1899 – 23 March 1992) was an Austrian-born British academic and philosopher. He is known for his contributions to political economy, political philosophy and intellectual history. Hayek shared the 1974 Nobe ...

wrote that "journalists, teachers, ministers, lecturers, publicists, radio commentators, writers of fiction, cartoonists, and artists" form an intellectual social class whose function is to communicate the complex and specialized knowledge of the scientist

A scientist is a person who Scientific method, researches to advance knowledge in an Branches of science, area of the natural sciences.

In classical antiquity, there was no real ancient analog of a modern scientist. Instead, philosophers engag ...

to the general public. He argued that intellectuals were attracted to socialism

Socialism is an economic ideology, economic and political philosophy encompassing diverse Economic system, economic and social systems characterised by social ownership of the means of production, as opposed to private ownership. It describes ...

or social democracy

Social democracy is a Social philosophy, social, Economic ideology, economic, and political philosophy within socialism that supports Democracy, political and economic democracy and a gradualist, reformist, and democratic approach toward achi ...

because the socialists offered "broad visions; the spacious comprehension of the social order, as a whole, which a planned system promises" and that such broad-vision philosophies "succeeded in inspiring the imagination of the intellectuals" to change and improve their societies. According to Hayek, intellectuals disproportionately support socialism for idealistic and utopian reasons that cannot be realized in practice.

Criticism

The French philosopher

The French philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre

Jean-Paul Charles Aymard Sartre (, ; ; 21 June 1905 – 15 April 1980) was a French philosopher, playwright, novelist, screenwriter, political activist, biographer, and literary criticism, literary critic, considered a leading figure in 20th ...

noted that "the Intellectual is someone who meddles in what does not concern them" ().

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

expressed the view that "intellectuals are specialists in defamation

Defamation is a communication that injures a third party's reputation and causes a legally redressable injury. The precise legal definition of defamation varies from country to country. It is not necessarily restricted to making assertions ...

, they are basically political commissars, they are the ideological administrators, the most threatened by dissidence." In his 1967 article " The Responsibility of Intellectuals", Chomsky analyzes the intellectual culture in the U.S., and argues that it is largely subservient to power. He is particularly critical of social scientist

Social science (often rendered in the plural as the social sciences) is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among members within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the ...

s and technocrats, who provide a pseudo-scientific justification for the crimes of the state.

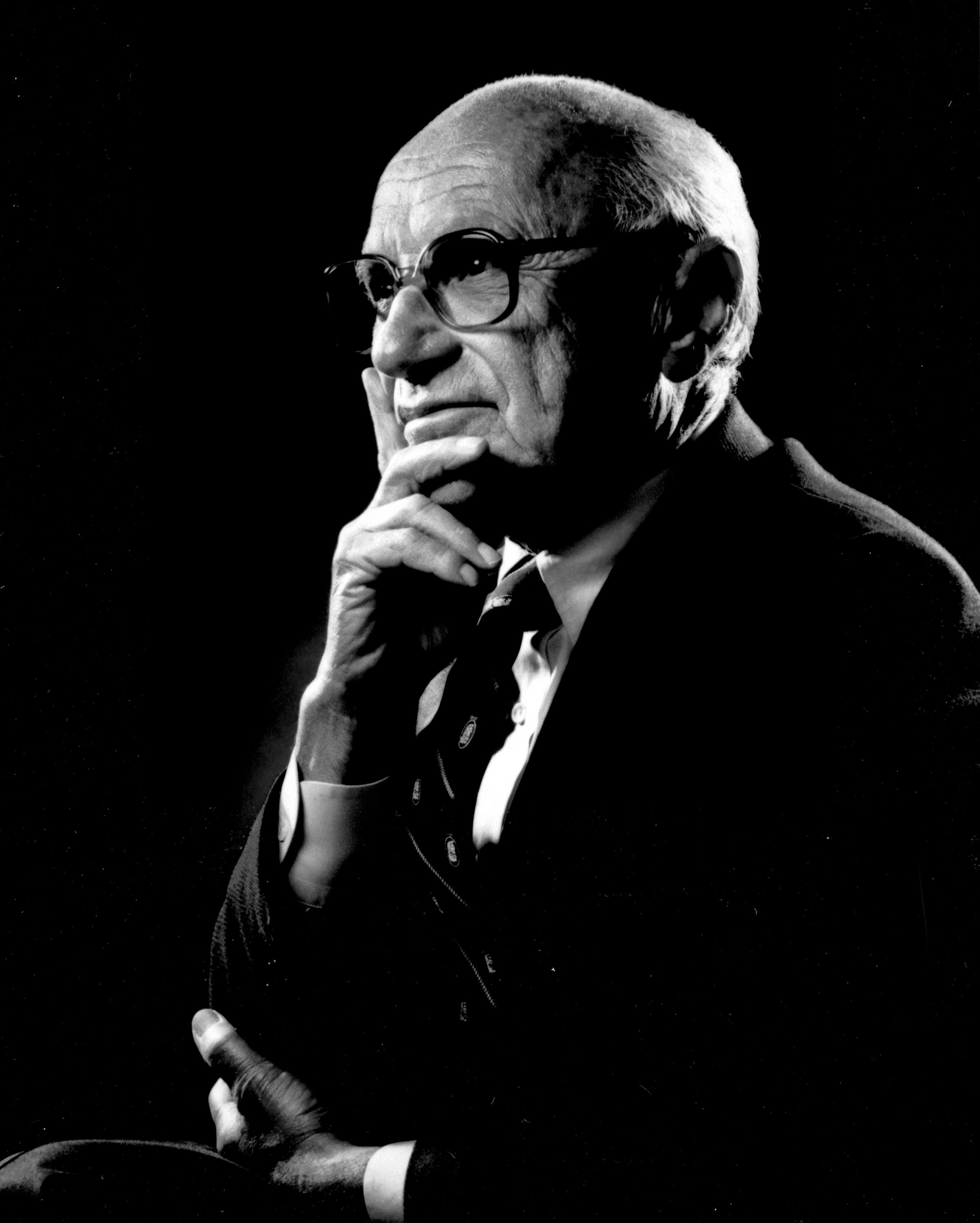

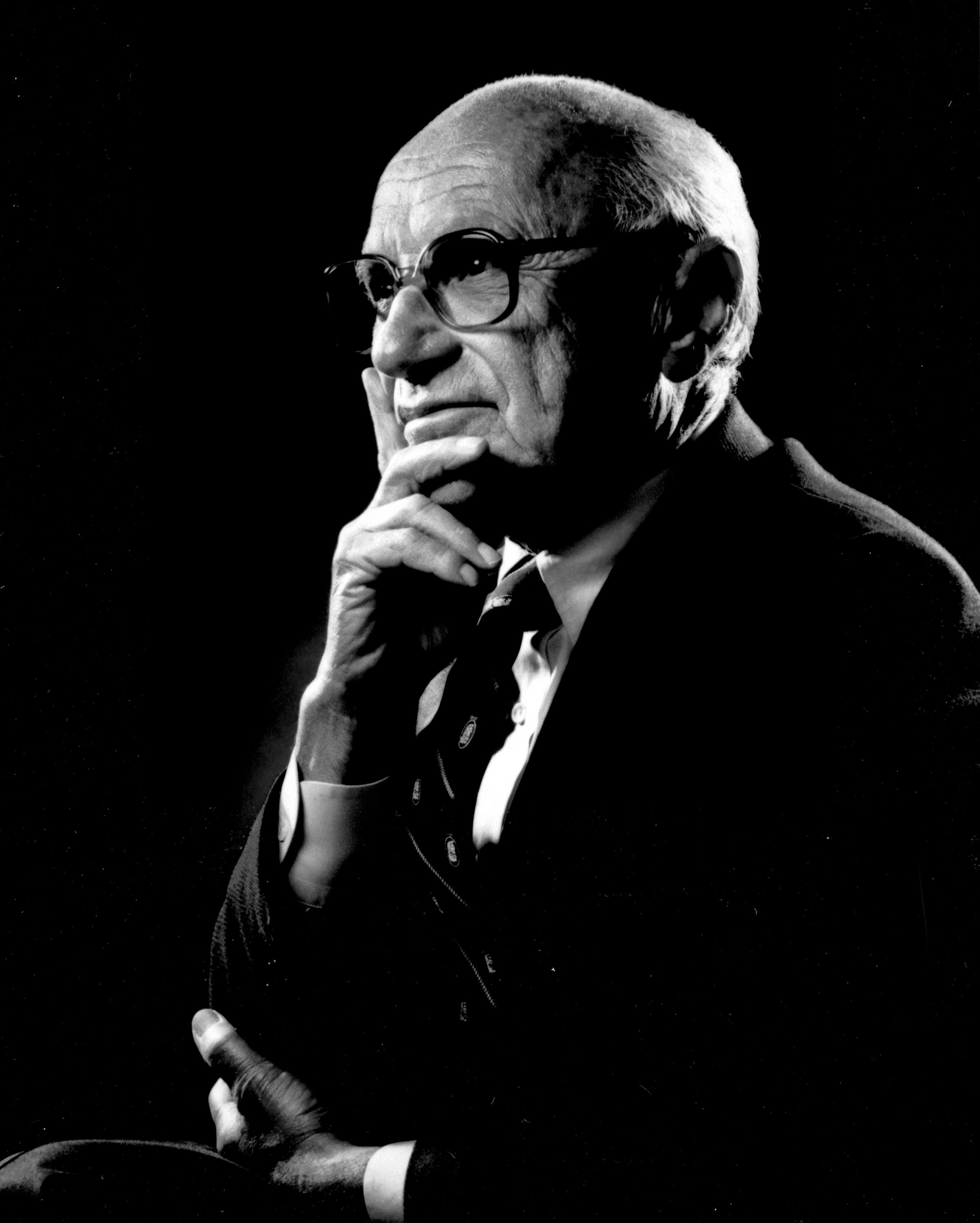

In "An Interview with Milton Friedman" (1974), the American economist Milton Friedman

Milton Friedman (; July 31, 1912 – November 16, 2006) was an American economist and statistician who received the 1976 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his research on consumption analysis, monetary history and theory and ...

said that businessmen and intellectuals are enemies of capitalism

Capitalism is an economic system based on the private ownership of the means of production and their use for the purpose of obtaining profit. This socioeconomic system has developed historically through several stages and is defined by ...

: most intellectuals believed in socialism while businessmen expected economic privileges. In his essay "Why Do Intellectuals Oppose Capitalism?" (1998), the American libertarian philosopher Robert Nozick

Robert Nozick (; November 16, 1938 – January 23, 2002) was an American philosopher. He held the Joseph Pellegrino Harvard University Professor, University Professorship at Harvard University,Cato Institute

The Cato Institute is an American libertarian think tank headquartered in Washington, D.C. It was founded in 1977 by Ed Crane, Murray Rothbard, and Charles Koch, chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Koch Industries.Koch ...

argued that intellectuals become embittered leftists because their superior intellectual work, much rewarded at school and at university, are undervalued and underpaid in the capitalist market economy

A market economy is an economic system in which the decisions regarding investment, production, and distribution to the consumers are guided by the price signals created by the forces of supply and demand. The major characteristic of a mark ...

. Thus, intellectuals turn against capitalism despite enjoying more socioeconomic status than the average person.

The conservative

Conservatism is a cultural, social, and political philosophy and ideology that seeks to promote and preserve traditional institutions, customs, and values. The central tenets of conservatism may vary in relation to the culture and civiliza ...

economist Thomas Sowell

Thomas Sowell ( ; born June 30, 1930) is an American economist, economic historian, and social and political commentator. He is a senior fellow at the Hoover Institution. With widely published commentary and books—and as a guest on T ...

wrote in his book '' Intellectuals and Society'' (2010) that intellectuals, who are producers of knowledge, not material goods, tend to speak outside their own areas of expertise, and yet expect social and professional benefits from the halo effect derived from possessing professional expertise. In relation to other professions, public intellectuals are socially detached from the negative and unintended consequences

In the social sciences, unintended consequences (sometimes unanticipated consequences or unforeseen consequences, more colloquially called knock-on effects) are outcomes of a purposeful action that are not intended or foreseen. The term was po ...

of public policy

Public policy is an institutionalized proposal or a Group decision-making, decided set of elements like laws, regulations, guidelines, and actions to Problem solving, solve or address relevant and problematic social issues, guided by a conceptio ...

derived from their ideas. Sowell gives the example of Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

(1872–1970), who advised the British government against national rearmament in the years before the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War (1 September 1939 – 2 September 1945) was a World war, global conflict between two coalitions: the Allies of World War II, Allies and the Axis powers. World War II by country, Nearly all of the wo ...

.

References

Bibliography

* Aron, Raymond (1962) ''The Opium of the Intellectuals.'' New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. * Basov, Nikita ''et al''. (2010). ''The Intellectual: A Phenomenon in Multidimensional Perspectives''Inter-Disciplinary Press

. * Bates, David, ed., (2007). ''Marxism, Intellectuals and Politics.'' London: Palgrave. * Benchimol, Alex. (2016) ''Intellectual Politics and Cultural Conflict in the Romantic Period: Scottish Whigs, English Radicals and the Making of the British Public Sphere'' (London: Routledge). * Benda, Julien (2003). ''The Treason of the Intellectuals.'' New Brunswick, N.J.: Transaction Publishers. * Camp, Roderic (1985). ''Intellectuals and the State in Twentieth-Century Mexico.'' Austin: University of Texas Press. * Coleman, Peter (2010) ''The Last Intellectuals.'' Sydney: Quadrant Books. * Di Leo, Jeffrey R., and Peter Hitchcock, eds. (2016) ''The New Public Intellectual: Politics, Theory, and the Public Sphere''. (Springer). * Finkielkraut, Alain (1995). ''The Defeat of the Mind.'' Columbia University Press. * Gella, Aleksander, Ed., (1976). ''The Intelligentsia and the Intellectuals.'' California: Sage Publication. * Gouldner, Alvin W. (1979)

''The Future of the Intellectuals and the Rise of the New Class.''

New York: The Seabury Press. * Gross, John (1969). ''The Rise and Fall of the Man of Letters''. New York: Macmillan. * Huszar, George B. de, ed., (1960). ''The Intellectuals: A Controversial Portrait''. Glencoe, Illinois: The Free Press. Anthology with many contributors. * Johnson, Paul (1990). ''Intellectuals''. New York: Harper Perennial . Highly ideological criticisms of Rousseau, Shelley,

Marx

Karl Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, political theorist, economist, journalist, and revolutionary socialist. He is best-known for the 1848 pamphlet '' The Communist Manifesto'' (written with Friedrich Engels) ...

, Ibsen

Henrik Johan Ibsen (; ; 20 March 1828 – 23 May 1906) was a Norwegian playwright, poet and actor. Ibsen is considered the world's pre-eminent dramatist of the 19th century and is often referred to as "the father of modern drama." He pioneered ...

, Tolstoy, Hemingway, Bertrand Russell

Bertrand Arthur William Russell, 3rd Earl Russell, (18 May 1872 – 2 February 1970) was a British philosopher, logician, mathematician, and public intellectual. He had influence on mathematics, logic, set theory, and various areas of analytic ...

, Brecht, Sartre, Edmund Wilson, Victor Gollancz

Sir Victor Gollancz (; 9 April 1893 – 8 February 1967) was a British publisher and humanitarian. Gollancz was known as a supporter of left-wing politics. His loyalties shifted between liberalism and communism; he defined himself as a Christian ...

, Lillian Hellman

Lillian Florence Hellman (June 20, 1905 – June 30, 1984) was an American playwright, Prose, prose writer, Memoir, memoirist, and screenwriter known for her success on Broadway as well as her communist views and political activism. She was black ...

, Cyril Connolly

Cyril Vernon Connolly CBE (10 September 1903 – 26 November 1974) was an English literary critic and writer. He was the editor of the influential literary magazine ''Horizon (British magazine), Horizon'' (1940–49) and wrote ''Enemies of Pro ...

, Norman Mailer

Nachem Malech Mailer (January 31, 1923 – November 10, 2007), known by his pen name Norman Kingsley Mailer, was an American writer, journalist and filmmaker. In a career spanning more than six decades, Mailer had 11 best-selling books, at least ...

, James Baldwin, Kenneth Tynan, Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

, and others.

* Kennedy, Michael D. (2015). ''Globalizing knowledge: Intellectuals, universities and publics in transformation'' (Stanford University Press). 424ponline review

* Konrad, George ''et al''. (1979). ''The Intellectuals On The Road To Class Power.'' Sussex: Harvester Press. * Lasch, Christopher (1997). ''The New Radicalism in America, 1889–1963: The Intellectual as a Social Type.'' New York: W.W. Norton & Co. * Lemert, Charles (1991). ''Intellectuals and Politics.'' Newbury Park, Calif.: Sage Publications. * McCaughan, Michael (2000). ''True Crime: Rodolfo Walsh and the Role of the Intellectual in Latin American Politics.'' Latin America Bureau . * Michael, John (2000). ''Anxious Intellects: Academic Professionals, Public Intellectuals, and Enlightenment Values.'' Duke University Press. * Misztal, Barbara A. (2007). ''Intellectuals and the Public Good.'' Cambridge University Press. * Moebius, Stephan. Intellektuellensoziologie: Skizze einer Methodologie. In: Sozial.Geschichte Online. H. 2 (2010), S. 37–63, hier S. 42 (PDF; 173 kB). * Molnar, Thomas (1961)

''The Decline of the Intellectual.''

Cleveland: The World Publishing Company. * Piereson, James (2006)

''The New Criterion'', Vol. XXV, p. 52. * Posner, Richard A. (2002). ''Public Intellectuals: A Study of Decline.'' Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press . * Rieff, Philip, Ed., (1969)

''On Intellectuals''

New York: Doubleday & Co. * Sawyer, S., and Iain Stewart, eds. (2016) ''In Search of the Liberal Moment: Democracy, Anti-totalitarianism, and Intellectual Politics in France since 1950'' (Springer). * Showalter, Elaine (2001). ''Inventing Herself: Claiming A Feminist Intellectual Heritage.'' London: Picador. * Viereck, Peter (1953). ''Shame and Glory of the Intellectuals.'' Boston: Beacon Press.

Further reading

* Aczél, Tamás & Méray, Tibor. (1959) ''The Revolt of the Mind.'' New York: Frederick A. Praeger. * Barzun, Jacques (1959). ''The House of Intellect''. New York: Harper. * Berman, Paul (2010). ''The Flight of the Intellectuals.'' New York: Melville House. * Carey, John (2005). ''The Intellectuals And The Masses: Pride and Prejudice Among the Literary Intelligentsia, 1880–1939.'' Chicago Review Press. * Chomsky, Noam (1968). "The Responsibility of Intellectuals." In: ''The Dissenting Academy'', ed. Theolord Roszak. New York: Pantheon Books, pp. 254–298. * Grayling, A.C. (2013)"Do Public Intellectuals Matter?,"

''Prospect Magazine,'' No. 206. * Hamburger, Joseph (1966). ''Intellectuals in Politics.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. * Hayek, F.A. (1949). "The Intellectuals and Socialism," ''The University of Chicago Law Review,'' Vol. XVI, No. 3, pp. 417–433. * Huizinga, Johan (1936). ''In the Shadows of Tomorrow.'' New York: W.W. Norton & Company. * Kidder, David S., Oppenheim, Noah D., (2006). '' The Intellectual Devotional.'' Emmaus, Pennsylvania: Rodale Books . * Laruelle, François (2014). ''Intellectuals and Power.'' Cambridge: Polity Press. * Lilla, Mark (2003). ''The Reckless Mind – Intellectuals in Politics.'' New York: New York Review Books. * Lukacs, John A. (1958). "Intellectuals, Catholics, and the Intellectual Life," ''Modern Age,'' Vol. II, No. 1, pp. 40–53. * MacDonald, Heather (2001). ''The Burden of Bad Ideas.'' New York: Ivan R. Dee. * Milosz, Czeslaw (1990). '' The Captive Mind.'' New York: Vintage Books. * Molnar, Thomas (1958). "Intellectuals, Experts, and the Classless Society," ''Modern Age,'' Vol. II, No. 1, pp. 33–39. * Moses, A. Dirk (2009) ''German Intellectuals and the Nazi Past.'' Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. * Rothbard, Murray N. (1989). "World War I as Fulfillment: Power and the Intellectuals," ''The Journal of Libertarian Studies,'' Vol. IX, No. 1, pp. 81–125. * Sapiro, Gisèle. (2014). ''The French Writers' War 1940–1953'' (1999; English edition 2014); highly influential study of intellectuals in the French Resistanc

online review

* Shapiro, J. Salwyn (1920)

"The Revolutionary Intellectual,"

''The Atlantic Monthly,'' Vol. CXXV, pp. 320–330. * Shenfield, Arthur A. (1970). "The Ugly Intellectual," ''The Modern Age'', Vol. XVI, No. 1, pp. 9–14. * Shlapentokh, Vladimir (1990) ''Soviet Intellectuals and Political Power.'' Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press. * Shore, Marci (2009). ''Caviar and Ashes.'' New Haven: Yale University Press. * Small, Helen (2002). ''The Public Intellectual.'' Oxford: Blackwell Publishing. * Strunsky, Simeon (1921)

"Intellectuals and Highbrows,"

''Vanity Fair'', Vol. XV, pp. 52, 92. * Whittington-Egan, Richard (2003-08-01). ''"The Vanishing Man of Letters: Part One"''. Contemporary Review. * Whittington-Egan, Richard (2003-10-01). ''"The Vanishing Man of Letters: Part Two"''. Contemporary Review. * Wolin, Richard (2010). ''The Wind from the East: French Intellectuals, the Culture Revolution and the Legacy of the 1960s.'' Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press.

External links

The Responsibility of Intellectuals

by

Noam Chomsky

Avram Noam Chomsky (born December 7, 1928) is an American professor and public intellectual known for his work in linguistics, political activism, and social criticism. Sometimes called "the father of modern linguistics", Chomsky is also a ...

, 23 February 1967.

* classified by profession, discipline, scholastic citations, media affiliation, number of web hits and sex.

*

"The Optimist's Book Club"

''The New Haven Advocate''—discussion of public intellectuals in the 21st century. {{authority control 1810s neologisms Academia Intellectual history Lord Byron Occupations Positions of authority Social classes Sociology of culture Stereotypes Thought