Independence Of Lebanon on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Lebanese Independence Day ( ar, عيد الإستقلال اللبناني, translit=Eid Al-Istiqlal, lit=Festival of the Independence; french: Indépendance du Liban) is the national day of

While the Lebanese have been in a constant struggle for independence from foreign powers since the age of the

While the Lebanese have been in a constant struggle for independence from foreign powers since the age of the

After the imprisonment of the Lebanese officials, the Lebanese MPs reunited in the house of the speaker of parliament,

After the imprisonment of the Lebanese officials, the Lebanese MPs reunited in the house of the speaker of parliament,

Lebanon, as a member of the family of Arab states, should cooperate with the other Arab states where possible, and in case of conflict among them, it should not side with one state against another.

# Public offices should be distributed proportionally among the recognized religious groups, but in technical positions preference should be given to competence without regard to confessional considerations. Moreover, the three top government positions should be distributed as follows: the president of the republic should be a

Lebanon, as a member of the family of Arab states, should cooperate with the other Arab states where possible, and in case of conflict among them, it should not side with one state against another.

# Public offices should be distributed proportionally among the recognized religious groups, but in technical positions preference should be given to competence without regard to confessional considerations. Moreover, the three top government positions should be distributed as follows: the president of the republic should be a

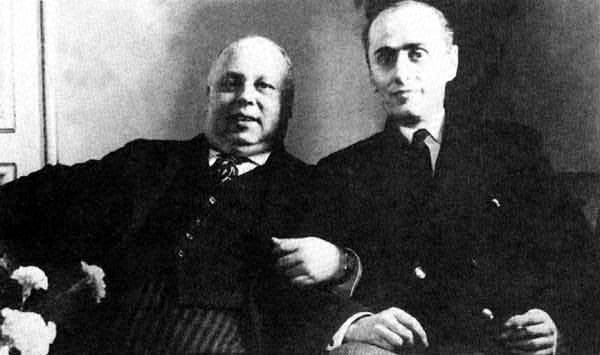

In memory of Emir Majid Arslan

{{Lebanon topics Public holidays in Lebanon

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

, celebrated on 22 November in commemoration of the end of the French Control over Lebanon in 1943, after 23 years of Mandate rule.

Pre-Independence period

While the Lebanese have been in a constant struggle for independence from foreign powers since the age of the

While the Lebanese have been in a constant struggle for independence from foreign powers since the age of the Old Testament

The Old Testament (often abbreviated OT) is the first division of the Christian biblical canon, which is based primarily upon the 24 books of the Hebrew Bible or Tanakh, a collection of ancient religious Hebrew writings by the Israelites. The ...

, the modern struggle for Lebanese independence can be traced back to the emergence of Fakhr-al-Din II

Fakhr al-Din ibn Qurqumaz Ma'n ( ar, فَخْر ٱلدِّين بِن قُرْقُمَاز مَعْن, Fakhr al-Dīn ibn Qurqumaz Maʿn; – March or April 1635), commonly known as Fakhr al-Din II or Fakhreddine II ( ar, فخر الدين ال ...

in the late 16th century, a Druze

The Druze (; ar, دَرْزِيٌّ, ' or ', , ') are an Arabic-speaking esoteric ethnoreligious group from Western Asia who adhere to the Druze faith, an Abrahamic, monotheistic, syncretic, and ethnic religion based on the teachings of ...

chief who became the first local leader in a thousand years to bring the major sects of Mount Lebanon

Mount Lebanon ( ar, جَبَل لُبْنَان, ''jabal lubnān'', ; syr, ܛܘܪ ܠܒ݂ܢܢ, ', , ''ṭūr lewnōn'' french: Mont Liban) is a mountain range in Lebanon. It averages above in elevation, with its peak at .

Geography

The Mount Le ...

into sustained mutual interaction. Fakhr-al-Din also brought western Europe back to Mount Lebanon. The French traveler Laurent d'Arvieux Laurent d'Arvieux (21 June 1635 – 30 October 1702) was a French traveller and diplomat born in Marseille.Le Consulat de France à Alep au XVIIe siecle2009, p.29-38

Arvieux is known for his travels in the Middle East, which began in 1654 as a ...

observed massive French commercial buildings in Sidon

Sidon ( ; he, צִידוֹן, ''Ṣīḏōn'') known locally as Sayda or Saida ( ar, صيدا ''Ṣaydā''), is the third-largest city in Lebanon. It is located in the South Governorate, of which it is the capital, on the Mediterranean coast. ...

, Fakhr-al-Din's political centre, where bustling crowds of Muslims

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abraha ...

, Maronites

The Maronites ( ar, الموارنة; syr, ܡܖ̈ܘܢܝܐ) are a Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and Levant region of the Middle East, whose members traditionally belong to the Maronite Church, with the largest ...

, Orthodox Christians

Orthodoxy (from Greek: ) is adherence to correct or accepted creeds, especially in religion.

Orthodoxy within Christianity refers to acceptance of the doctrines defined by various creeds and ecumenical councils in Antiquity, but different Churc ...

and Jews

Jews ( he, יְהוּדִים, , ) or Jewish people are an ethnoreligious group and nation originating from the Israelites Israelite origins and kingdom: "The first act in the long drama of Jewish history is the age of the Israelites""The ...

intermingled. Under his rule, printing presses were introduced and Jesuit priest

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders = ...

s and Catholic nun

A nun is a woman who vows to dedicate her life to religious service, typically living under vows of poverty, chastity, and obedience in the enclosure of a monastery or convent.''The Oxford English Dictionary'', vol. X, page 599. The term is o ...

s encouraged to open schools throughout the land. Fakhr-al-Din's growing influence, disobedience and ambitions threatened Ottoman interests. Ottoman Turkish troops captured Fakhr-al-Din and had him executed in Istanbul

Istanbul ( , ; tr, İstanbul ), formerly known as Constantinople ( grc-gre, Κωνσταντινούπολις; la, Constantinopolis), is the List of largest cities and towns in Turkey, largest city in Turkey, serving as the country's economic, ...

in 1635.

In response to a massacre of Maronites by Druze during the 1860 civil war, 6000 French troops landed near Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

to ostensibly protect the Maronite communities. The Ottoman Sultan, Abdulmejid I

Abdulmejid I ( ota, عبد المجيد اول, ʿAbdü'l-Mecîd-i evvel, tr, I. Abdülmecid; 25 April 182325 June 1861) was the 31st Sultan of the Ottoman Empire and succeeded his father Mahmud II on 2 July 1839. His reign was notable for the ...

, had no choice but to approve the French landing at Beirut and review the status of Mount Lebanon. In 1861, the Ottomans and five European powers (Britain, France, Russia, Austria, and Prussia

Prussia, , Old Prussian: ''Prūsa'' or ''Prūsija'' was a German state on the southeast coast of the Baltic Sea. It formed the German Empire under Prussian rule when it united the German states in 1871. It was ''de facto'' dissolved by an em ...

) negotiated a new political system for Mount Lebanon in a commission chaired by Mehmed Fuad Pasha

Mehmed Fuad Pasha (1814 – February 12, 1869), sometimes known as Keçecizade Mehmed Fuad Pasha and commonly known as Fuad Pasha, was an Ottoman administrator and statesman, who is known for his prominent role in the Tanzimat reforms of the m ...

, the Ottoman Foreign Minister. The international commission established a tribunal to punish the Druze lords for war crimes and the commission further agreed on an autonomous province of Mount Lebanon, the Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate

The Mount Lebanon Mutasarrifate (1861–1918, ar, مُتَصَرِّفِيَّة جَبَل لُبْنَان, translit=Mutasarrifiyyat Jabal Lubnān; ) was one of the Ottoman Empire's subdivisions following the Tanzimat reform. After 1861, ther ...

. In September 1864, the Ottomans and Europeans signed the '' Règlement Organique'' defining the new entity, including the French recommendation of an elected multi-communal council to advise the governor.

Electoral representation and rough demographic weighting of communal membership was established after the foundation of the autonomous Mount Lebanon province. A two-stage electoral process became refined over several decades, with secret balloting introduced in 1907. Mount Lebanon became the only Ottoman provincial council that was democratically elected, representing members of the major sects. Elections for one-third of the council seats took place every two years. The governor of Mount Lebanon, a non-Maronite Catholic from outside, was of Ottoman ministerial rank with the title Pasha, though a step below a full provincial governor. Presiding judges of district courts were from the same sect as the largest religious group in the district, with deputy judges representing the next two largest groups. Court decisions had to involve the Court President and at least one other judge. This system facilitated Maronite acquiescence, Druze re-integration and sectarian reconciliation in Mount Lebanon.

With the onset of World War I, the Ottoman Sultanate began to disintegrate. The Ottomans feared Arab independence. In response, the Ottomans abolished the autonomous province of Mount Lebanon in 1915, putting the mountain communities under emergency military rule. The repression culminated on 6 May 1916, with the hanging of 14 activists and journalists, including proponents of both Arab and Lebanese independence, Christians and Muslims, clerics and secularists. The location of the hangings in central Beirut became known as Martyrs' Square, today the focal point of public Lebanese political expression. Respect for Ottoman authority in the local community collapsed after this event. The Ottomans confiscated grain from the Levant during the war, resulting in a massive famine. Half the population of Mount Lebanon was wiped out. Both Schilcher and Khalife estimated up to 200,000 deaths in the mountain.

A Phoenician identity

Following Ottoman repression, the Arabs were fed up with Ottoman rule. After the Turks were expelled from the Levant at the end of World War I, the Syrian National Congress in Damascus proclaimed independence and sovereignty over a region that also included Lebanon in 1920. In Beirut, the Christian press expressed its hostility to the decisions of the Syrian National Congress. Lebanese nationalists used the crisis to convene a council of Christian figures in Baabda that proclaimed the independence of Lebanon on 22 March 1920. Despite these declarations, the region was divided among the victorious British and French according to theSykes–Picot Agreement

The Sykes–Picot Agreement () was a 1916 secret treaty between the United Kingdom and France, with assent from the Russian Empire and the Kingdom of Italy, to define their mutually agreed Sphere of influence, spheres of influence and control in a ...

, a secret 1916 pact of the UK and France.

Mount Lebanon Maronites under the Maronite Patriarch Elias al-Huwayyik lobbied the French for an enlarged Lebanon to become a Catholic Christian homeland. Patriarch al-Huwayyik shrewdly conflated a new Lebanon with ancient Phoenicia

Phoenicia () was an ancient thalassocratic civilization originating in the Levant region of the eastern Mediterranean, primarily located in modern Lebanon. The territory of the Phoenician city-states extended and shrank throughout their histor ...

to highlight a unique personality. The Phoenician allusion derived from a European passion for romanticizing antiquity (see Ernest Renan's ''Mission de Phénicie'', 1864). Among the wider public, the resurrection of Phoenicia and the concept of a distinctive Lebanon received stimulus from the literary output of Jibran Khalil Jibran

Gibran Khalil Gibran ( ar, جُبْرَان خَلِيل جُبْرَان, , , or , ; January 6, 1883 – April 10, 1931), usually referred to in English as Kahlil Gibran (pronounced ), was a Lebanese-American writer, poet and visual artist ...

. Jibran drew out feelings of oppression and conflict with established religion and interpersonal tensions. These themes resonated with a multi-sectarian Lebanon. Jibran's combination of Christian ambience with outreach to Muslims reinforced Lebanese nationalist thought. Incorporation of Jibran into school curricula in the 1920s helped make him by far Lebanon's most influential writer.

Greater Lebanon from Ra's Naqura in the south to Nahr al-Kabir north of Tripoli, and from the coast to the Anti-Lebanon mountains was established under the French provisional mandate in April 1920. Patriarch al-Huwayyik, with the Ottoman imposed famine in recent memory, insisted on the acquisition of the Biqa valley, a principal food producing area. The French were supposed to guide the population to self-determination with regular progress reports to the League of Nations. In reality, the French arrested and suppressed proponents of self-determination at various times.

France confirmed the electoral system of the former Ottoman Mount Lebanon province in setting up a Representative Council for Greater Lebanon in 1922. Two stage elections, universal adult male suffrage, and multimember multi-communal constituencies continued the situation that prevailed in Mount Lebanon up to 1914.

The brief term (November 1925-August 1926) of the first civilian High Commissioner, French senator and journalist Henry de Jouvenel

Henry de Jouvenel des Ursins (5 April 1876 – 5 October 1935) was a French journalist and statesman.

, proved decisive in the history of the Lebanese republic. A newly elected Representative Council became the clearinghouse for Lebanese input, and de Jouvenel endorsed it as the de facto constituent assembly. The Representative Council delegated drafting of a constitution to a twelve-member committee. The concept of Greater Lebanon as a Christian/Muslim partnership distinct from its Arab hinterland underpinned the project. The leading lights of the committee were non-Maronite Christians - Michel Chiha

Michel Chiha (1891–1954) was a Lebanese banker, a politician, writer and journalist. Along with Charles Corm, Petro Trad and Omar Daouk, he is considered one of the fathers of the Lebanese Constitution. His ideas and actions have had an importan ...

, Orthodox chairman Shibli Dammus and the Orthodox Petro Grad. They adapted the 1875 French constitution, and De Jouvenal hastened the Representative Council to enact the draft in May 1926. It included a republic, executive power shared between the President and Prime Minister, a two-chamber legislature, equitable multi-communal representation, and Greater Lebanon as the final homeland of its inhabitants.

The Franco-Lebanese Treaty of 1936 promised complete independence and membership within the League of Nations within three years. The conservative French National Assembly refused to ratify the Treaty.

When the Vichy government

Vichy France (french: Régime de Vichy; 10 July 1940 – 9 August 1944), officially the French State ('), was the fascist French state headed by Marshal Philippe Pétain during World War II. Officially independent, but with half of its terr ...

assumed power over French territory in 1940, General Henri Fernand Dentz was appointed as High Commissioner of Lebanon. This new turning point led to the resignation of Lebanese president Emile Edde on 4 April 1941. After 5 days, Dentz appointed Alfred Naccache

Alfred Georges Naccache (or Naqqache) ( ar, ألفرد جورج النقاش; 3 May 1888– 26 September 1978) was a Lebanese Maronite statesman, Prime Minister and head of state during the French Mandate of Lebanon. In 1919 he contributed to '' La ...

for a presidency period that lasted only 3 months and ending with the surrender of the Vichy forces posted in Lebanon and Syria to the Free French

Free France (french: France Libre) was a political entity that claimed to be the legitimate government of France following the dissolution of the Third Republic. Led by French general , Free France was established as a government-in-exile ...

and British

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

troops. On 14 July 1941, an armistice was signed in Acre

The acre is a unit of land area used in the imperial

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imp ...

ending the clashes between the two sides and opening the way for General Charles de Gaulle

Charles André Joseph Marie de Gaulle (; ; (commonly abbreviated as CDG) 22 November 18909 November 1970) was a French army officer and statesman who led Free France against Nazi Germany in World War II and chaired the Provisional Government ...

's visit to Lebanon, thus ending Vichy's control.

Having the opportunity to discuss matters of sovereignty and independence, the Lebanese national leaders asked de Gaulle to end the French Mandate and unconditionally recognize Lebanon's independence. After national and international pressure, General Georges Catroux

Georges Albert Julien Catroux (29 January 1877 – 21 December 1969) was a French Army general and diplomat who served in both World War I and World War II, and served as Grand Chancellor of the Légion d'honneur from 1954 to 1969.

Life

Cat ...

(a delegate general under de Gaulle) proclaimed in the name of his government the Lebanese independence on 26 November 1941. Countries such as the United States

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territorie ...

, the United Kingdom

The United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, commonly known as the United Kingdom (UK) or Britain, is a country in Europe, off the north-western coast of the continental mainland. It comprises England, Scotland, Wales and North ...

, the Arab states

The Arab world ( ar, اَلْعَالَمُ الْعَرَبِيُّ '), formally the Arab homeland ( '), also known as the Arab nation ( '), the Arabsphere, or the Arab states, refers to a vast group of countries, mainly located in Western As ...

, the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

, and certain Asia

Asia (, ) is one of the world's most notable geographical regions, which is either considered a continent in its own right or a subcontinent of Eurasia, which shares the continental landmass of Afro-Eurasia with Africa. Asia covers an area ...

n countries recognized this independence, and some of them even exchanged ambassadors with Beirut

Beirut, french: Beyrouth is the capital and largest city of Lebanon. , Greater Beirut has a population of 2.5 million, which makes it the third-largest city in the Levant region. The city is situated on a peninsula at the midpoint o ...

. However this didn't stop the French from exercising their authority.

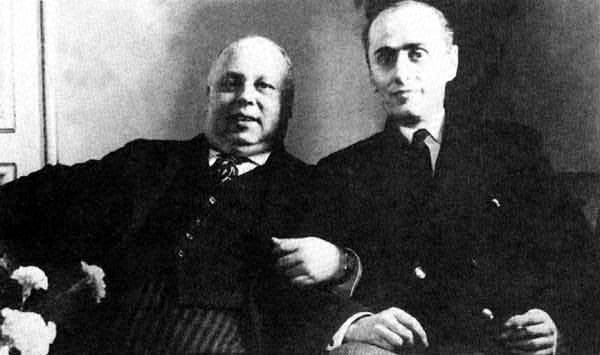

On 8 November 1943, and after electing president Bechara El Khoury

Bechara El Khoury ( ar, بشارة خليل الخوري; 10 August 1890 – 11 January 1964) was a Lebanese politician who served as the 1st president of Lebanon, holding office from 21 September 1943 to 18 September 1952, apart from an 11-day ...

and appointing prime minister Riad al-Solh

Riad Reda Al Solh ( ar, رياض الصلح; 17 August 1894 – 17 July 1951) was the first prime minister of Lebanon after the country's independence.

, the Chamber of Deputies amended the Lebanese Constitution, which abolished the articles referring to the Mandate and modified the specified powers of the High Commissioner, thus unilaterally ending the Mandate. The French responded by arresting the President, the Prime Minister, and other cabinet members, and exiling them to an old citadel located in Rashaya

Rashaya, Rachaya, Rashaiya, Rashayya or Rachaiya ( ar, راشيا), also known as Rashaya al-Wadi or Rachaya el-Wadi (and variations), is a town of the Rashaya District in the west of the Jnoub Government of Lebanon. It is situated at around abov ...

. This incident, which unified the Christian

Christians () are people who follow or adhere to Christianity, a monotheistic Abrahamic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus Christ. The words ''Christ'' and ''Christian'' derive from the Koine Greek title ''Christós'' (Χρι ...

and Muslim

Muslims ( ar, المسلمون, , ) are people who adhere to Islam, a monotheistic religion belonging to the Abrahamic tradition. They consider the Quran, the foundational religious text of Islam, to be the verbatim word of the God of Abrah ...

opinion towards the mandate, led to an international pressure demanding the Lebanese leaders' release and massive street protests.

Government of Bechamoun

After the imprisonment of the Lebanese officials, the Lebanese MPs reunited in the house of the speaker of parliament,

After the imprisonment of the Lebanese officials, the Lebanese MPs reunited in the house of the speaker of parliament, Sabri Hamadé

Sabri Hamadeh, also written as Sabri Hamadé or Hamada ( ar, صبري حماده) (1902–1976) was a Lebanese politician and long-time Speaker of the Lebanese Parliament.

Sabri Hamadeh served as a pioneer in the Lebanese Independence. He worked ...

, and assigned the two uncaught ministers Emir Majid Arslan

Emir Majid Toufic Arslan ( ar, الأمير مجيد توفيق أرسلان) (February 1908 — September 18, 1983) was a Lebanese Druze leader and head of the Arslan feudal Druze ruling family. Arslan was the leader of the Yazbaki (Arslan affi ...

(Minister of National Defence) and Habib Abou Chahla

Habib Abu Shahla ( / ''Ḥabīb Abū Shahlā'', also spelled Abou Chahla) or Abi Shahla ( ar, أبي شهلا / ''Abī Shahlā'', also spelled Abi Chahla; 1902 – 22 March 1957) was a Lebanese politician and public figure, several times membe ...

to carry out the functions of the government. The two ministers then moved to Bechamoun and their government became known as the Government of Bechamoun. The Government was provided shelter and protection in the residences of Hussein and Youssef El Halabi, recognized leaders in Bechamoun. These residences were strategically located, providing optimum protection to the ministers.

The newly formed government refused to hold talks with General Catroux or any other mandate official, stressing that any negotiation should be done with the captured government.

It also formed a military resistance under the name of the "National Guard", whose supreme commander was Naim Moghabghab

Naim Moghabghab (Arabic: نـعـيـم مـغـبـغـب) (January 11, 1911 – July 27, 1959) was a Lebanese political leader and an independence hero among Lebanon's Christian population. He founded, along with president Camille Chamoun (in o ...

, with the help of Adib el Beainy and Munir Takieddine. This military group fought the battle of independence and later became the core of the Lebanese Army

)

, founded = 1 August 1945

, current_form = 1991

, disbanded =

, branches = Lebanese Ground ForcesLebanese Air Force Lebanese Navy

, headquarters = Yarze, Lebanon

, flying_hours =

, websit ...

that was later formed in 1946 under the leadership of Emir Majid and Naim Moghabghab

Naim Moghabghab (Arabic: نـعـيـم مـغـبـغـب) (January 11, 1911 – July 27, 1959) was a Lebanese political leader and an independence hero among Lebanon's Christian population. He founded, along with president Camille Chamoun (in o ...

.

Finally, France yielded to the augmenting pressure of the Lebanese people, as well as the demand of numerous countries and released the prisoners from Rashaya in the morning of Monday 22 November 1943. Since then, this day has been celebrated as the Lebanese Independence Day.

This historic site of Lebanese independence and residence of Hussein El Halabi, where the first Lebanese flag was raised on 11 November 1943, continues to welcome tourists and visitors throughout the year to celebrate national pride.

Post-Independence period

After the independence, the modern Lebanese political system was founded in 1943 by an unwritten agreement between the two most prominent Christian and Muslim leaders, Khouri and al-Solh and which was later called theNational Pact

The National Pact ( ar, الميثاق الوطني, translit-std=DIN, translit=al Mithaq al Watani) is an unwritten agreement that laid the foundation of Lebanon as a multiconfessional state following negotiations between the Shia, Sunni, and Ma ...

(''al Mithaq al Watani الميثاق الوطني '').Harris, William. Lebanon: a history, 600-2011. Oxford University Press, 2012.

The National Pact had four principles:

# Lebanon was to be a completely politically independent state. Lebanon would not enter into Western-led alignments; in return, Lebanon would not compromise its sovereignty with Arab

The Arabs (singular: Arab; singular ar, عَرَبِيٌّ, DIN 31635: , , plural ar, عَرَب, DIN 31635: , Arabic pronunciation: ), also known as the Arab people, are an ethnic group mainly inhabiting the Arab world in Western Asia, ...

states.

# Lebanon would have an Arab face and another for the West, as it could not cut off its spiritual and intellectual ties with the West, which had helped it attain such a notable degree of progress.

#  Lebanon, as a member of the family of Arab states, should cooperate with the other Arab states where possible, and in case of conflict among them, it should not side with one state against another.

# Public offices should be distributed proportionally among the recognized religious groups, but in technical positions preference should be given to competence without regard to confessional considerations. Moreover, the three top government positions should be distributed as follows: the president of the republic should be a

Lebanon, as a member of the family of Arab states, should cooperate with the other Arab states where possible, and in case of conflict among them, it should not side with one state against another.

# Public offices should be distributed proportionally among the recognized religious groups, but in technical positions preference should be given to competence without regard to confessional considerations. Moreover, the three top government positions should be distributed as follows: the president of the republic should be a Maronite

The Maronites ( ar, الموارنة; syr, ܡܖ̈ܘܢܝܐ) are a Christian ethnoreligious group native to the Eastern Mediterranean and Levant region of the Middle East, whose members traditionally belong to the Maronite Church, with the larges ...

and the prime minister, a Sunni

Sunni Islam () is the largest branch of Islam, followed by 85–90% of the world's Muslims. Its name comes from the word '' Sunnah'', referring to the tradition of Muhammad. The differences between Sunni and Shia Muslims arose from a disagr ...

Muslim. The speaker of the Chamber of Deputies was reserved for a Shi'i

Shīʿa Islam or Shīʿīsm is the second-largest branch of Islam. It holds that the Islamic prophet Muhammad designated ʿAlī ibn Abī Ṭālib as his successor (''khalīfa'') and the Imam (spiritual and political leader) after him, most n ...

Muslim in 1947. The ratio of deputies was to be six Christians to five Muslims.

In 1945, Lebanon became a founding member of the Arab League

The Arab League ( ar, الجامعة العربية, ' ), formally the League of Arab States ( ar, جامعة الدول العربية, '), is a regional organization in the Arab world, which is located in Northern Africa, Western Africa, E ...

(22 March) and a founding member of the United Nations

The United Nations (UN) is an intergovernmental organization whose stated purposes are to maintain international peace and international security, security, develop friendly relations among nations, achieve international cooperation, and be ...

( 1945 UN San Francisco Conference). On 31 December 1946, French troops withdrew completely from Lebanon.

See also

*History of Lebanon

The history of Lebanon covers the history of the modern Republic of Lebanon and the earlier emergence of Greater Lebanon under the French Mandate for Syria and the Lebanon, as well as the previous history of the region, covered by the modern stat ...

* San Remo conference

The San Remo conference was an international meeting of the post-World War I Allied Supreme Council as an outgrowth of the Paris Peace Conference, held at Villa Devachan in Sanremo, Italy, from 19 to 26 April 1920. The San Remo Resolution pas ...

* France-Lebanon relations

References

External links

In memory of Emir Majid Arslan

{{Lebanon topics Public holidays in Lebanon

Lebanon

Lebanon ( , ar, لُبْنَان, translit=lubnān, ), officially the Republic of Lebanon () or the Lebanese Republic, is a country in Western Asia. It is located between Syria to the north and east and Israel to the south, while Cyprus li ...

November observances