Indentured Workers on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Indentured servitude is a form of

Indentured servitude is a form of

in JSTOR

* Ballagh, James Curtis. ''White Servitude In The Colony Of Virginia: A Study Of The System Of Indentured Labor In The American Colonies'' (1895

excerpt and text search

* Brown, Kathleen. ''Goodwives, Nasty Wenches & Anxious Patriachs: gender, race and power in Colonial Virginia'', U. of North Carolina Press, 1996. * Hofstadter, Richard. ''America at 1750: A Social Portrait'' (Knopf, 1971) pp 33–6

* Jernegan, Marcus Wilson ''Laboring and Dependent Classes in Colonial America, 1607–1783'' (1931) * Morgan, Edmund S. ''American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia.'' (Norton, 1975). * Nagl, Dominik. ''No Part of the Mother Country, but Distinct Dominions – Law, State Formation and Governance in England, Massachusetts und South Carolina, 1630–1769'' (LIT, 2013): 515–535, 577f., 635–68

* Salinger, Sharon V. ''To serve well and faithfully: Labor and Indentured Servants in Pennsylvania'', 1682–1800.'' (2000) * Tomlins, Christopher. ''Freedom Bound: Law, Labor, and Civic Identity in English Colonization, 1580–1865'' (2010); influential recent interpretatio

online review

* Torabully, Khal, and Marina Carter, ''Coolitude: An Anthology of the Indian Labour Diaspora'' Anthem Press, London, 2002, * Torabully, Khal, Voices from the Aapravasi Ghat – Indentured imaginaries, poetry collection on the coolie route and the fakir's aesthetics, Aapravasi Ghat Trust Fund, AGTF, Mauritius, November 2, 2013. * Wareing, John. ''Indentured Migration and the Servant Trade from London to America, 1618–1718''. Oxford Oxford University Press, February 2017 * Whitehead, John Frederick, Johann Carl Buttner, Susan E. Klepp, and Farley Grubb. ''Souls for Sale: Two German Redemptioners Come to Revolutionary America'', Max Kade German-American Research Institute Series, . *Zipf, Karin L. ''Labor of Innocents: Forced Apprenticeship in North Carolina, 1715–1919'' (2005).

* Voices from the Aapravasi Ghat, Khal TOrabully, https://web.archive.org/web/20150617164151/http://www.potomitan.info/torabully/voices.php {{Authority control Debt bondage Apprenticeship Colonization history of the United States Colonial United States (British)

Indentured servitude is a form of

Indentured servitude is a form of labor

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

in which a person is contracted to work without salary

A salary is a form of periodic payment from an employer to an employee, which may be specified in an employment contract. It is contrasted with piece wages, where each job, hour or other unit is paid separately, rather than on a periodic basis.

F ...

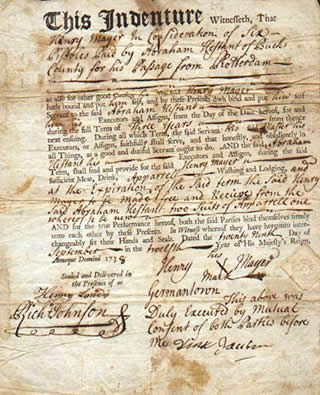

for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt

Debt is an obligation that requires one party, the debtor, to pay money or other agreed-upon value to another party, the creditor. Debt is a deferred payment, or series of payments, which differentiates it from an immediate purchase. The d ...

repayment, or it may be imposed as a judicial punishment. Historically, it has been used to pay for apprenticeship

Apprenticeship is a system for training a new generation of practitioners of a trade or profession with on-the-job training and often some accompanying study (classroom work and reading). Apprenticeships can also enable practitioners to gain a ...

s, typically when an apprentice agreed to work for free for a master tradesman

A tradesman, tradeswoman, or tradesperson is a skilled worker that specializes in a particular trade (occupation or field of work). Tradesmen usually have work experience, on-the-job training, and often formal vocational education in contrast ...

to learn a trade

Trade involves the transfer of goods and services from one person or entity to another, often in exchange for money. Economists refer to a system or network that allows trade as a market.

An early form of trade, barter, saw the direct exch ...

(similar to a modern internship

An internship is a period of work experience offered by an organization for a limited period of time. Once confined to medical graduates, internship is used practice for a wide range of placements in businesses, non-profit organizations and gover ...

but for a fixed length of time, usually seven years or less). Later it was also used as a way for a person to pay the cost of transportation to colonies in the Americas.

Like any loan

In finance, a loan is the lending of money by one or more individuals, organizations, or other entities to other individuals, organizations, etc. The recipient (i.e., the borrower) incurs a debt and is usually liable to pay interest on that ...

, an indenture could be sold; most employers had to depend on middlemen to recruit and transport the workers so indentures (indentured workers) were commonly bought and sold when they arrived at their destinations. Like prices of slaves, their price went up or down depending on supply and demand. When the indenture (loan) was paid off, the worker was free. Sometimes they might be given a plot of land.

Indentured workers could usually marry, move about locally as long as the work got done, read whatever they wanted, and take classes.

The Americas

North America

Until the late 18th century, indentured servitude was common inBritish America

British America comprised the colonial territories of the English Empire, which became the British Empire after the 1707 union of the Kingdom of England with the Kingdom of Scotland to form the Kingdom of Great Britain, in the Americas from 1 ...

. It was often a way for Europeans to migrate to the American colonies: they signed an indenture in return for a costly passage. However, the system was also used to exploit Asians (mostly from India and China) who wanted to migrate to the New World. These Asian people were used mainly to construct roads and railway systems. After their indenture expired, the immigrants were free to work for themselves or another employer. At least one economist has suggested that indentured servitude occurred largely as "an institutional response to a capital market imperfection".

In some cases, the indenture was made with a ship's master, who sold the indenture to an employer in the colonies. Most indentured servants worked as farm laborers or domestic servants, although some were apprenticed to craftsmen.

The terms of an indenture were not always enforced by American courts, although runaways were usually sought out and returned to their employer.

Between one-half and two-thirds of European immigrants to the American Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centur ...

between the 1630s and American Revolution came under indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

s. However, while almost half the European immigrants to the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th cent ...

were indentured servants, at any one time they were outnumbered by workers who had never been indentured, or whose indenture had expired, and thus free wage labor was the more prevalent for Europeans in the colonies. Indentured people were numerically important mostly in the region from Virginia

Virginia, officially the Commonwealth of Virginia, is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Southeastern regions of the United States, between the East Coast of the United States, Atlantic Coast and the Appalachian Mountains. The geography an ...

north to New Jersey

New Jersey is a U.S. state, state in the Mid-Atlantic States, Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern United States, Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York (state), New York; on the ea ...

. Other colonies saw far fewer of them. The total number of European immigrants to all 13 colonies before 1775 was about 500,000; of these 55,000 were involuntary prisoners. Of the 450,000 or so European arrivals who came voluntarily, Tomlins estimates that 48% were indentured. About 75% of these were under the age of 25. The age of adulthood for men was 24 years (not 21); those over 24 generally came on contracts lasting about 3 years. Regarding the children who came, Gary Nash reports that "many of the servants were actually nephews, nieces, cousins and children of friends of emigrating Englishmen, who paid their passage in return for their labor once in America."

Several instances of kidnapping

In criminal law, kidnapping is the unlawful confinement of a person against their will, often including transportation/ asportation. The asportation and abduction element is typically but not necessarily conducted by means of force or fear: the ...

for transportation to the Americas are recorded, such as that of Peter Williamson Peter Williamson may refer to:

* Peter Williamson (memoirist) (1730–1799), aka "Indian Peter", Scottish memoirist who was part-showman, part-entrepreneur and inventor

* Peter Williamson (footballer) (born 1953), Australian rules footballer

* Pet ...

(1730–1799). As historian Richard Hofstadter

Richard Hofstadter (August 6, 1916October 24, 1970) was an American historian and public intellectual of the mid-20th century.

Hofstadter was the DeWitt Clinton Professor of American History at Columbia University. Rejecting his earlier histor ...

pointed out, "Although efforts were made to regulate or check their activities, and they diminished in importance in the eighteenth century, it remains true that a certain small part of the European colonial population of America was brought by force, and a much larger portion came in response to deceit and misrepresentation on the part of the spirits ecruiting agents" One "spirit" named William Thiene was known to have spirited away 840 people from Britain to the colonies in a single year. Historian Lerone Bennett Jr.

Lerone Bennett Jr. (October 17, 1928 – February 14, 2018) was an African-American scholar, author and social historian who analyzed race relations in the United States. His works included ''Before the Mayflower'' (1962) and '' Forced into Glo ...

notes that "Masters given to flogging often did not care whether their victims were black or white."

Also, during the 18th and early 19th centuries, children from the UK were often kidnapped and sold into indentured labor in the American and Caribbean colonies (often without any indentures).

Indentured servitude was also used by governments in Britain as a punishment for captured prisoners of war

A prisoner of war (POW) is a person who is held Captivity, captive by a belligerent power during or immediately after an armed conflict. The earliest recorded usage of the phrase "prisoner of war" dates back to 1610.

Belligerents hold priso ...

in rebellions and civil wars. Oliver Cromwell

Oliver Cromwell (25 April 15993 September 1658) was an English politician and military officer who is widely regarded as one of the most important statesmen in English history. He came to prominence during the 1639 to 1651 Wars of the Three K ...

sent into indentured service thousands of prisoners captured in the 1648 Battle of Preston and the 1651 Battle of Worcester

The Battle of Worcester took place on 3 September 1651 in and around the city of Worcester, England and was the last major battle of the 1639 to 1653 Wars of the Three Kingdoms. A Parliamentarian army of around 28,000 under Oliver Cromwell def ...

. King James II

James VII and II (14 October 1633 16 September 1701) was King of England and King of Ireland as James II, and King of Scotland as James VII from the death of his elder brother, Charles II of England, Charles II, on 6 February 1685. He was depo ...

acted similarly after the Monmouth Rebellion

The Monmouth Rebellion, also known as the Pitchfork Rebellion, the Revolt of the West or the West Country rebellion, was an attempt to depose James II, who in February 1685 succeeded his brother Charles II as king of England, Scotland and Ire ...

in 1685, and use of such measures continued into the 18th century.

Indentured servants could not marry without the permission of their master, were sometimes subject to physical punishment and did not receive legal favor from the courts. Female indentured servants in particular might be raped and/or sexually abused by their masters. If children were produced the labour would be extended by 2 years. Cases of successful prosecution for these crimes were very uncommon, as indentured servants were unlikely to have access to a magistrate, and social pressure to avoid such brutality could vary by geography and cultural norm. The situation was particularly difficult for indentured women, because in both low social class and gender, they were believed to be particularly prone to vice, making legal redress unusual.

The American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revolu ...

severely limited immigration to the United States, but economic historians dispute its long-term impact. Sharon Salinger argues that the economic crisis that followed the war made long-term labor contracts unattractive. His analysis of Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

's population shows how the percentage of bound citizens fell from 17% to 6.4% over the course of the war. William Miller posits a more moderate theory, stating that "the Revolution...wrought disturbances upon white servitude. But these were temporary rather than lasting". David Galenson supports this theory by proposing that the numbers of British indentured servants never recovered, and that Europeans from other nationalities replaced them.

Indentured servitude began its decline after Bacon’s Rebellion. Bacon's Rebellion was a servant uprising against the government of Colonial Virginia. This was due to multiple factors, such as the treatment of servants, support of native tribes in the surrounding area, a refusal to expand the amount of land an indentured servant could work by the colonial government, and inequality between the upper and lower class in colonial society. Indentured servitude was the primary source of labor for early American colonists up until the rebellion. Little changed in the immediate aftermath of Bacon's Rebellion; however, the rebellion did cause a general distrust of servant labor and fear of future rebellion. The fear of indentured servitude would eventually cement itself into the hearts of Americans, leading towards the reliance on enslaved Africans. This helped to ingrain the idea of racial segregation and unite white Americans under race rather than economic or social class. Doing so would prevent the potential for future rebellion and change the way that agriculture was approached in the future.

The American and British governments passed several laws that helped foster the decline of indentures. The UK Parliament's Passenger Vessels Act 1803 regulated travel conditions aboard ships to make transportation more expensive, so as to hinder landlords' tenants seeking a better life. An American law passed in 1833 abolished the imprisonment of debtors, which made prosecuting runaway servants more difficult, increasing the risk of indenture contract purchases. The 13th Amendment, passed in the wake of the American Civil War

The American Civil War (April 12, 1861 – May 26, 1865; also known by other names) was a civil war in the United States. It was fought between the Union ("the North") and the Confederacy ("the South"), the latter formed by state ...

, made indentured servitude illegal in the United States.

Contracts

Through its introduction, the details regarding indentured labor varied across import and export regions and most overseas contracts were made before the voyage with the understanding that prospective migrants were competent enough to make overseas contracts on their own account and that they preferred to have a contract before the voyage. Most labor contracts made were in increments of five years, with the opportunity to extend another five years. Many contracts also provided free passage home after the dictated labor was completed. However, there were generally no policies regulating employers once the labor hours were completed, which led to frequent ill-treatment.Caribbean

In 1643, the European population of Barbados was 37,200 (86% of the population). During theWars of the Three Kingdoms

The Wars of the Three Kingdoms were a series of related conflicts fought between 1639 and 1653 in the kingdoms of Kingdom of England, England, Kingdom of Scotland, Scotland and Kingdom of Ireland, Ireland, then separate entities united in a pers ...

, at least 10,000 Scottish and Irish prisoners of war were transported as indentured laborers to the colonies.

A half million Europeans went as indentured servants to the Caribbean (primarily the English-speaking islands of the Caribbean) before 1840.

In 1838, with the abolition of slavery at its onset, the British were in the process of transporting a million Indians out of India and into the Caribbean to take the place of the recently freed Africans (freed in 1833) in indentureship. Women, looking for what they believed would be a better life in the colonies, were specifically sought after and recruited at a much higher rate than men due to the high population of men already in the colonies. However, women had to prove their status as single and eligible to emigrate, as married women could not leave without their husbands. Many women seeking escape from abusive relationships were willing to take that chance. The Indian Immigration Act of 1883 prevented women from exiting India as widowed or single in order to escape. Arrival in the colonies brought unexpected conditions of poverty, homelessness, and little to no food as the high numbers of emigrants overwhelmed the small villages and flooded the labor market. Many were forced into signing labor contracts that exposed them to the hard field labor on the plantation. Additionally, on arrival to the plantation, single women were 'assigned' a man as they were not allowed to live alone. The subtle difference between slavery and indenture-ship is best seen here as women were still subjected to the control of the plantation owners as well as their newly assigned 'partner'.

Colonial Indian indenture system

TheIndian indenture system

The Indian indenture system was a system of indentured servitude, by which more than one million Indians were transported to labour in European colonies, as a substitute for slave labor, following the abolition of the trade in the early 19th ce ...

was a system of indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

, a form of debt bondage

Debt bondage, also known as debt slavery, bonded labour, or peonage, is the pledge of a person's services as security for the repayment for a debt or other obligation. Where the terms of the repayment are not clearly or reasonably stated, the pe ...

, by which two million India

India, officially the Republic of India ( Hindi: ), is a country in South Asia. It is the seventh-largest country by area, the second-most populous country, and the most populous democracy in the world. Bounded by the Indian Ocean on the ...

ns called coolie

A coolie (also spelled koelie, kuli, khuli, khulie, cooli, cooly, or quli) is a term for a low-wage labourer, typically of South Asian or East Asian descent.

The word ''coolie'' was first popularized in the 16th century by European traders acros ...

s were transport

Transport (in British English), or transportation (in American English), is the intentional movement of humans, animals, and goods from one location to another. Modes of transport include air, land ( rail and road), water, cable, pipel ...

ed to various colonies of Europe

Europe is a large peninsula conventionally considered a continent in its own right because of its great physical size and the weight of its history and traditions. Europe is also considered a subcontinent of Eurasia and it is located enti ...

an powers to provide labour for the (mainly sugar) plantations. It started from the end of slavery in 1833 and continued until 1920. This resulted in the development of a large Indian diaspora

Overseas Indians ( IAST: ), officially Non-Resident Indians (NRIs) and Overseas Citizens of India (OCIs) are Indians who live outside of the Republic of India. According to the Government of India, ''Non-Resident Indians'' are citizens of Indi ...

, which spread from the Indian Ocean (i.e. Réunion

Réunion (; french: La Réunion, ; previously ''Île Bourbon''; rcf, label= Reunionese Creole, La Rényon) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas department and region of France. It is located approximately east of the island ...

and Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

) to Pacific Ocean (i.e. Fiji), as well as the growth of Indo-Caribbean

Indo-Caribbeans or Indian-Caribbeans are Indian people in the Caribbean who are descendants of the Jahaji Indian indentured laborers brought by the British, Dutch, and French during the colonial era from the mid-19th century to the early 20th ...

and Indo-African population.

The British wanted local black Africans to work in Natal as workers. But the locals refused, and as a result, the British introduced the Indian indenture system, resulting in a permanent Indian South African

Indian South Africans are South Africans who descend from indentured labourers and free migrants who arrived from British India during the late 1800s and early 1900s. The majority live in and around the city of Durban, making it one of the l ...

presence. On 18 January 1826, the Government of the French

French (french: français(e), link=no) may refer to:

* Something of, from, or related to France

** French language, which originated in France, and its various dialects and accents

** French people, a nation and ethnic group identified with Franc ...

Indian Ocean

The Indian Ocean is the third-largest of the world's five oceanic divisions, covering or ~19.8% of the water on Earth's surface. It is bounded by Asia to the north, Africa to the west and Australia to the east. To the south it is bounded by ...

island of Réunion

Réunion (; french: La Réunion, ; previously ''Île Bourbon''; rcf, label= Reunionese Creole, La Rényon) is an island in the Indian Ocean that is an overseas department and region of France. It is located approximately east of the island ...

laid down terms for the introduction of Indian labourers to the colony. Each man was required to appear before a magistrate

The term magistrate is used in a variety of systems of governments and laws to refer to a civilian officer who administers the law. In ancient Rome, a ''magistratus'' was one of the highest ranking government officers, and possessed both judici ...

and declare that he was going voluntarily. The contract was for five years with pay of ₹8 (12¢ US) per month and rations provided labourers had been transported from Pondicherry

Pondicherry (), now known as Puducherry ( French: Pondichéry ʊdʊˈtʃɛɹi(listen), on-dicherry, is the capital and the most populous city of the Union Territory of Puducherry in India. The city is in the Puducherry district on the sout ...

and Karaikal

Karaikal ( /kʌdɛkʌl/, french: Karikal /kaʁikal/) is a town of the Indian Union Territory of Puducherry. Karaikal was sold to the French by the Rajah of Thanjavur and became a French Colony in 1739. The French held control, with oc ...

. The first attempt at importing Indian labour into Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

, in 1829, ended in failure, but by 1834, with abolition of slavery throughout most of the British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading post ...

, transportation of Indian labour to the island gained pace. By 1838, 25,000 Indian labourers had been transported to Mauritius.

After the end of slavery, the West Indian

A West Indian is a native or inhabitant of the West Indies (the Antilles and the Lucayan Archipelago). For more than 100 years the words ''West Indian'' specifically described natives of the West Indies, but by 1661 Europeans had begun to use it ...

sugar colonies tried the use of emancipated slave

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

s, families from Ireland

Ireland ( ; ga, Éire ; Ulster Scots dialect, Ulster-Scots: ) is an island in the Atlantic Ocean, North Atlantic Ocean, in Northwestern Europe, north-western Europe. It is separated from Great Britain to its east by the North Channel (Grea ...

, Germany

Germany, officially the Federal Republic of Germany (FRG),, is a country in Central Europe. It is the most populous member state of the European Union. Germany lies between the Baltic and North Sea to the north and the Alps to the sou ...

and Malta

Malta ( , , ), officially the Republic of Malta ( mt, Repubblika ta' Malta ), is an island country in the Mediterranean Sea. It consists of an archipelago, between Italy and Libya, and is often considered a part of Southern Europe. It lies ...

and Portuguese from Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

. All these efforts failed to satisfy the labour needs of the colonies due to high mortality of the new arrivals and their reluctance to continue working at the end of their indenture. On 16 November 1844, the British Indian Government legalised emigration to Jamaica

Jamaica (; ) is an island country situated in the Caribbean Sea. Spanning in area, it is the third-largest island of the Greater Antilles and the Caribbean (after Cuba and Hispaniola). Jamaica lies about south of Cuba, and west of Hispan ...

, Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and Demerara

Demerara ( nl, Demerary, ) is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state f ...

( Guyana). The first ship, , sailed from Calcutta

Kolkata (, or , ; also known as Calcutta , the official name until 2001) is the capital of the Indian state of West Bengal, on the eastern bank of the Hooghly River west of the border with Bangladesh. It is the primary business, comm ...

for British Guiana on 13 January 1838, and arrived in Berbice on 5 May 1838. Transportation to the Caribbean stopped in 1848 due to problems in the sugar industry and resumed in Demerara and Trinidad in 1851 and Jamaica in 1860.

This system of labour was coined by contemporaries at the time as a "new system of slavery", a term later used by historian Hugh Tinker in his largely influential book of the same name.

The Indian indenture system was finally banned in 1917. According to ''The Economist

''The Economist'' is a British weekly newspaper printed in demitab format and published digitally. It focuses on current affairs, international business, politics, technology, and culture. Based in London, the newspaper is owned by The Econ ...

'', "When the Indian Legislative Council

The Council of India was the name given at different times to two separate bodies associated with British rule in India.

The original Council of India was established by the Charter Act of 1833 as a council of four formal advisors to the Governor ...

finally ended indenture...it did so because of pressure from Indian nationalists

Indian nationalism is an instance of territorial nationalism, which is inclusive of all of the people of India, despite their diverse ethnic, linguistic and religious backgrounds. Indian nationalism can trace roots to pre-colonial India, ...

and declining profitability, rather than from humanitarian concerns."

Oceania

Convicts transported to the Australian colonies before the 1840s often found themselves hired out in a form of indentured labor. Indentured servants also emigrated toNew South Wales

)

, nickname =

, image_map = New South Wales in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of New South Wales in AustraliaCoordinates:

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, es ...

.

The Van Diemen's Land Company used skilled indentured labor for periods of seven years or less. A similar scheme for the Swan River area of Western Australia existed between 1829 and 1832.

During the 1860s planters in Australia, Fiji, New Caledonia, and the Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

Island

An island or isle is a piece of subcontinental land completely surrounded by water. Very small islands such as emergent land features on atolls can be called islets, skerries, cays or keys. An island in a river or a lake island may be ...

s, in need of laborers, encouraged a trade in long-term indentured labor called "blackbirding". At the height of the labor trade, more than one-half the adult male population of several of the islands worked abroad.

Over a period of 40 years, from the mid-19th century to the early 20th century, labor for the sugar-cane fields of Queensland

)

, nickname = Sunshine State

, image_map = Queensland in Australia.svg

, map_caption = Location of Queensland in Australia

, subdivision_type = Country

, subdivision_name = Australia

, established_title = Before federation

, established_ ...

, Australia included an element of coercive recruitment and indentured servitude of the 62,000 South Sea Islanders

South Sea Islanders are the Australian descendants of Pacific Islanders from more than 80 islandsincluding the Oceanian archipelagoes of the Solomon Islands, New Caledonia, Vanuatu, Fiji, the Gilbert Islands and New Irelandwho were kidnappe ...

. The workers came mainly from Melanesia

Melanesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania in the southwestern Pacific Ocean. It extends from Indonesia's New Guinea in the west to Fiji in the east, and includes the Arafura Sea.

The region includes the four independent countries of Fiji, ...

– mainly from the Solomon Islands

Solomon Islands is an island country consisting of six major islands and over 900 smaller islands in Oceania, to the east of Papua New Guinea and north-west of Vanuatu. It has a land area of , and a population of approx. 700,000. Its ca ...

and Vanuatu

Vanuatu ( or ; ), officially the Republic of Vanuatu (french: link=no, République de Vanuatu; bi, Ripablik blong Vanuatu), is an island country located in the South Pacific Ocean. The archipelago, which is of volcanic origin, is east of no ...

– with a small number from Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

n and Micronesia

Micronesia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, consisting of about 2,000 small islands in the western Pacific Ocean. It has a close shared cultural history with three other island regions: the Philippines to the west, Polynesia to the east, and ...

n areas such as Samoa

Samoa, officially the Independent State of Samoa; sm, Sāmoa, and until 1997 known as Western Samoa, is a Polynesian island country consisting of two main islands (Savai'i and Upolu); two smaller, inhabited islands (Manono Island, Manono an ...

, the Gilbert Islands

The Gilbert Islands ( gil, Tungaru;Reilly Ridgell. ''Pacific Nations and Territories: The Islands of Micronesia, Melanesia, and Polynesia.'' 3rd. Ed. Honolulu: Bess Press, 1995. p. 95. formerly Kingsmill or King's-Mill IslandsVery often, this n ...

(subsequently known as Kiribati

Kiribati (), officially the Republic of Kiribati ( gil, ibaberikiKiribati),Kiribati

''The Wor ...

) and the ''The Wor ...

Ellice Islands

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northea ...

(subsequently known as Tuvalu

Tuvalu ( or ; formerly known as the Ellice Islands) is an island country and microstate in the Polynesian subregion of Oceania in the Pacific Ocean. Its islands are situated about midway between Hawaii and Australia. They lie east-northea ...

). They became collectively known as "Kanakas

Kanakas were workers (a mix of voluntary and involuntary) from various Pacific Islands employed in British colonies, such as British Columbia (Canada), Fiji, Solomon Islands, Vanuatu, Papua New Guinea and Queensland (Australia) in the 1 ...

".

It remains unknown how many Islanders the trade controversially kidnapped. Whether the system legally recruited Islanders, persuaded, deceived, coerced or forced them to leave their homes and travel by ship to Queensland remains difficult to determine. Official documents and accounts from the period often conflict with the oral tradition

Oral tradition, or oral lore, is a form of human communication wherein knowledge, art, ideas and cultural material is received, preserved, and transmitted orally from one generation to another. Vansina, Jan: ''Oral Tradition as History'' (1985 ...

passed down to the descendants of workers. Stories of blatantly violent kidnapping tend to relate to the first 10–15 years of the trade.

Australia deported many of these Islanders back to their places of origin in the period 1906–1908 under the provisions of the Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901

The Pacific Island Labourers Act 1901 was an Act of the Parliament of Australia which was designed to facilitate the mass deportation of nearly all the Pacific Islanders (called " Kanakas") working in Australia, especially in the Queensland s ...

.

The Australian administrated territories of Papua and New Guinea (joined after the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

to form Papua New Guinea

Papua New Guinea (abbreviated PNG; , ; tpi, Papua Niugini; ho, Papua Niu Gini), officially the Independent State of Papua New Guinea ( tpi, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niugini; ho, Independen Stet bilong Papua Niu Gini), is a country i ...

) were the last jurisdictions in the world to use indentured servitude.

Africa

A significant number of construction projects inBritish East Africa

East Africa Protectorate (also known as British East Africa) was an area in the African Great Lakes occupying roughly the same terrain as present-day Kenya from the Indian Ocean inland to the border with Uganda in the west. Controlled by Britai ...

and South Africa

South Africa, officially the Republic of South Africa (RSA), is the southernmost country in Africa. It is bounded to the south by of coastline that stretch along the South Atlantic and Indian Oceans; to the north by the neighbouring count ...

, required vast quantities of labor, exceeding the availability or willingness of local tribesmen. Indentured Indians from India were imported, for such projects as the Uganda Railway

The Uganda Railway was a metre-gauge railway system and former British state-owned railway company. The line linked the interiors of Uganda and Kenya with the Indian Ocean port of Mombasa in Kenya. After a series of mergers and splits, the li ...

, as farm labor, and as miners. They and their descendants formed a significant portion of the population and economy of Kenya and Uganda, although not without engendering resentment from others. Idi Amin

Idi Amin Dada Oumee (, ; 16 August 2003) was a Ugandan military officer and politician who served as the third president of Uganda from 1971 to 1979. He ruled as a military dictator and is considered one of the most brutal despots in modern w ...

's expulsion of the "Asians" from Uganda in 1972 was an expulsion of Indo-Africans.

The majority of the population of Mauritius

Mauritius ( ; french: Maurice, link=no ; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Moris ), officially the Republic of Mauritius, is an island nation in the Indian Ocean about off the southeast coast of the African continent, east of Madagascar. It incl ...

are descendants of Indian indentured labourers brought in between 1834 and 1921. Initially brought to work the sugar estates following the abolition of slavery in the British Empire an estimated half a million indentured laborers were present on the island during this period. Aapravasi Ghat

The Immigration Depot ( hi, आप्रवासी घाट, ISO 15919, ISO: ''Āpravāsī Ghāta'') is a building complex located in Port Louis on the Indian Ocean island of Mauritius, the first British Empire, British colony to receive inden ...

, in the bay at Port Louis

Port Louis (french: Port-Louis; mfe, label=Mauritian Creole, Polwi or , ) is the capital city of Mauritius. It is mainly located in the Port Louis District, with a small western part in the Black River District. Port Louis is the country's e ...

and now a UNESCO

The United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization is a specialized agency of the United Nations (UN) aimed at promoting world peace and security through international cooperation in education, arts, sciences and culture. I ...

site, was the first British colony to serve as a major reception centre for indentured Indians from India who came to work on plantation

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

s following the abolition of slavery.

Legal status

TheUniversal Declaration of Human Rights

The Universal Declaration of Human Rights (UDHR) is an international document adopted by the United Nations General Assembly that enshrines the rights and freedoms of all human beings. Drafted by a UN committee chaired by Eleanor Roosevelt, ...

(adopted by the United Nations General Assembly

The United Nations General Assembly (UNGA or GA; french: link=no, Assemblée générale, AG) is one of the six principal organs of the United Nations (UN), serving as the main deliberative, policymaking, and representative organ of the UN. Cur ...

in 1948) declares in Article 4 "No one shall be held in slavery or servitude; slavery and the slave trade shall be prohibited in all their forms". More specifically, it is dealt with by article 1(a) of the United Nations 1956 Supplementary Convention on the Abolition of Slavery.

However, only national legislation can establish the unlawfulness of indentured labor in a specific jurisdiction. In the United States, the Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act

The Victims of Trafficking and Violence Protection Act of 2000 (TVPA) is a federal statute passed into law in 2000 by the U.S. Congress and signed by President Clinton. The law was later reauthorized by presidents Bush, Obama, and Trump. In addit ...

(VTVPA) of 2000 extended servitude to cover peonage

Peon ( English , from the Spanish ''peón'' ) usually refers to a person subject to peonage: any form of wage labor, financial exploitation, coercive economic practice, or policy in which the victim or a laborer (peon) has little control over em ...

as well as Involuntary Servitude.

See also

* Bracero program *Coolie

A coolie (also spelled koelie, kuli, khuli, khulie, cooli, cooly, or quli) is a term for a low-wage labourer, typically of South Asian or East Asian descent.

The word ''coolie'' was first popularized in the 16th century by European traders acros ...

* Debt Bondage

Debt bondage, also known as debt slavery, bonded labour, or peonage, is the pledge of a person's services as security for the repayment for a debt or other obligation. Where the terms of the repayment are not clearly or reasonably stated, the pe ...

* English Poor Laws

The English Poor Laws were a system of poor relief in England and Wales that developed out of the codification of late-medieval and Tudor-era laws in 1587–1598. The system continued until the modern welfare state emerged after the Second W ...

* Human trafficking

Human trafficking is the trade of humans for the purpose of forced labour, sexual slavery, or commercial sexual exploitation for the trafficker or others. This may encompass providing a spouse in the context of forced marriage, or the extr ...

* Home Children

* Indenture

An indenture is a legal contract that reflects or covers a debt or purchase obligation. It specifically refers to two types of practices: in historical usage, an indentured servant status, and in modern usage, it is an instrument used for commercia ...

(document)

* Indentured servitude in Pennsylvania

* Involuntary servitude

Involuntary servitude or involuntary slavery is a legal and constitutional term for a person laboring against that person's will to benefit another, under some form of coercion, to which it may constitute slavery. While laboring to benefit another ...

* List of indentured servants

* Padrone system

* Penal transportation

Penal transportation or transportation was the relocation of convicted criminals, or other persons regarded as undesirable, to a distant place, often a colony, for a specified term; later, specifically established penal colonies became their d ...

* Redemptioner

* Scottish poorhouse

The Scottish poorhouse, occasionally referred to as a workhouse, provided accommodation for the destitute and poor in Scotland. The term ''poorhouse'' was almost invariably used to describe the institutions in that country, as unlike the regime ...

* Slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

* Irish indentured servants

* United States labor law

United States labor law sets the rights and duties for employees, labor unions, and employers in the United States. Labor law's basic aim is to remedy the "inequality of bargaining power" between employees and employers, especially employers "orga ...

Notes

References

* * * * * * * * * *Further reading

* Abramitzky, Ran; Braggion, Fabio. "Migration and Human Capital: Self-Selection of Indentured Servants to the Americas," ''Journal of Economic History,'' (2006) 66#4 pp 882–905in JSTOR

* Ballagh, James Curtis. ''White Servitude In The Colony Of Virginia: A Study Of The System Of Indentured Labor In The American Colonies'' (1895

excerpt and text search

* Brown, Kathleen. ''Goodwives, Nasty Wenches & Anxious Patriachs: gender, race and power in Colonial Virginia'', U. of North Carolina Press, 1996. * Hofstadter, Richard. ''America at 1750: A Social Portrait'' (Knopf, 1971) pp 33–6

* Jernegan, Marcus Wilson ''Laboring and Dependent Classes in Colonial America, 1607–1783'' (1931) * Morgan, Edmund S. ''American Slavery, American Freedom: The Ordeal of Colonial Virginia.'' (Norton, 1975). * Nagl, Dominik. ''No Part of the Mother Country, but Distinct Dominions – Law, State Formation and Governance in England, Massachusetts und South Carolina, 1630–1769'' (LIT, 2013): 515–535, 577f., 635–68

* Salinger, Sharon V. ''To serve well and faithfully: Labor and Indentured Servants in Pennsylvania'', 1682–1800.'' (2000) * Tomlins, Christopher. ''Freedom Bound: Law, Labor, and Civic Identity in English Colonization, 1580–1865'' (2010); influential recent interpretatio

online review

* Torabully, Khal, and Marina Carter, ''Coolitude: An Anthology of the Indian Labour Diaspora'' Anthem Press, London, 2002, * Torabully, Khal, Voices from the Aapravasi Ghat – Indentured imaginaries, poetry collection on the coolie route and the fakir's aesthetics, Aapravasi Ghat Trust Fund, AGTF, Mauritius, November 2, 2013. * Wareing, John. ''Indentured Migration and the Servant Trade from London to America, 1618–1718''. Oxford Oxford University Press, February 2017 * Whitehead, John Frederick, Johann Carl Buttner, Susan E. Klepp, and Farley Grubb. ''Souls for Sale: Two German Redemptioners Come to Revolutionary America'', Max Kade German-American Research Institute Series, . *Zipf, Karin L. ''Labor of Innocents: Forced Apprenticeship in North Carolina, 1715–1919'' (2005).

Historiography

* Donoghue, John. "Indentured Servitude in the 17th Century English Atlantic: A Brief Survey of the Literature," ''History Compass'' (Oct. 2013) 11#10 pp 893–902,External links

* https://uk.news.yahoo.com/unfree-irish-caribbean-were-indentured-servants-not-slaves-072226285.html#8TTqXzc * https://medium.com/@Limerick1914/we-had-it-worse-eebe705c41a#.or9hof7pm* Voices from the Aapravasi Ghat, Khal TOrabully, https://web.archive.org/web/20150617164151/http://www.potomitan.info/torabully/voices.php {{Authority control Debt bondage Apprenticeship Colonization history of the United States Colonial United States (British)