History of the battery on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Batteries provided the primary source of

Batteries provided the primary source of

Another problem with Volta's batteries was short battery life (an hour's worth at best), which was caused by two phenomena. The first was that the current produced electrolyzed the electrolyte solution, resulting in a film of

Another problem with Volta's batteries was short battery life (an hour's worth at best), which was caused by two phenomena. The first was that the current produced electrolyzed the electrolyte solution, resulting in a film of

An English professor of chemistry named John Frederic Daniell found a way to solve the hydrogen bubble problem in the Voltaic Pile by using a second electrolyte to consume the hydrogen produced by the first. In 1836, he invented the

An English professor of chemistry named John Frederic Daniell found a way to solve the hydrogen bubble problem in the Voltaic Pile by using a second electrolyte to consume the hydrogen produced by the first. In 1836, he invented the

The porous pot version of the Daniell cell was invented by

The porous pot version of the Daniell cell was invented by

In the 1860s, a Frenchman named Callaud invented a variant of the Daniell cell called the gravity cell. This simpler version dispensed with the porous barrier. This reduces the internal resistance of the system and, thus, the battery yields a stronger current. It quickly became the battery of choice for the American and British telegraph networks, and was widely used until the 1950s.

The gravity cell consists of a glass jar, in which a copper cathode sits on the bottom and a zinc anode is suspended beneath the rim. Copper sulfate crystals are scattered around the cathode and then the jar is filled with distilled water. As the current is drawn, a layer of zinc sulfate solution forms at the top around the anode. This top layer is kept separate from the bottom copper sulfate layer by its lower density and by the polarity of the cell.

The zinc sulfate layer is clear in contrast to the deep blue copper sulfate layer, which allows a technician to measure the battery life with a glance. On the other hand, this setup means the battery can be used only in a stationary appliance, or else the solutions mix or spill. Another disadvantage is that a current has to be continually drawn to keep the two solutions from mixing by diffusion, so it is unsuitable for intermittent use.

In the 1860s, a Frenchman named Callaud invented a variant of the Daniell cell called the gravity cell. This simpler version dispensed with the porous barrier. This reduces the internal resistance of the system and, thus, the battery yields a stronger current. It quickly became the battery of choice for the American and British telegraph networks, and was widely used until the 1950s.

The gravity cell consists of a glass jar, in which a copper cathode sits on the bottom and a zinc anode is suspended beneath the rim. Copper sulfate crystals are scattered around the cathode and then the jar is filled with distilled water. As the current is drawn, a layer of zinc sulfate solution forms at the top around the anode. This top layer is kept separate from the bottom copper sulfate layer by its lower density and by the polarity of the cell.

The zinc sulfate layer is clear in contrast to the deep blue copper sulfate layer, which allows a technician to measure the battery life with a glance. On the other hand, this setup means the battery can be used only in a stationary appliance, or else the solutions mix or spill. Another disadvantage is that a current has to be continually drawn to keep the two solutions from mixing by diffusion, so it is unsuitable for intermittent use.

Up to this point, all existing batteries would be permanently drained when all their chemical reactants were spent. In 1859,

Up to this point, all existing batteries would be permanently drained when all their chemical reactants were spent. In 1859,

In 1866, Georges Leclanché invented a battery that consists of a zinc anode and a

In 1866, Georges Leclanché invented a battery that consists of a zinc anode and a

Waldemar Jungner patented a

Waldemar Jungner patented a

electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as describ ...

before the development of electric generator

In electricity generation, a generator is a device that converts motive power ( mechanical energy) or fuel-based power ( chemical energy) into electric power for use in an external circuit. Sources of mechanical energy include steam turbines, g ...

s and electrical grid

An electrical grid is an interconnected network for electricity delivery from producers to consumers. Electrical grids vary in size and can cover whole countries or continents. It consists of:Kaplan, S. M. (2009). Smart Grid. Electrical Power ...

s around the end of the 19th century. Successive improvements in battery technology facilitated major electrical advances, from early scientific studies to the rise of telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

s and telephone

A telephone is a telecommunications device that permits two or more users to conduct a conversation when they are too far apart to be easily heard directly. A telephone converts sound, typically and most efficiently the human voice, into e ...

s, eventually leading to portable computer

A portable computer is a computer designed to be easily moved from one place to another and included a display and keyboard together, with a single plug, much like later desktop computers called '' all-in-ones'' (AIO), that integrate the ...

s, mobile phone

A mobile phone, cellular phone, cell phone, cellphone, handphone, hand phone or pocket phone, sometimes shortened to simply mobile, cell, or just phone, is a portable telephone that can make and receive calls over a radio frequency link wh ...

s, electric car

An electric car, battery electric car, or all-electric car is an automobile that is propelled by one or more electric motors, using only energy stored in batteries. Compared to internal combustion engine (ICE) vehicles, electric cars are quie ...

s, and many other electrical devices.

Students and engineers developed several commercially important types of battery. "Wet cells" were open containers that held liquid electrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon ...

and metallic electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or air). Electrodes are essential parts of batteries that can consist of a variety of materials ...

s. When the electrodes were completely consumed, the wet cell was renewed by replacing the electrodes and electrolyte. Open containers are unsuitable for mobile or portable use. Wet cells were used commercially in the telegraph and telephone systems. Early electric cars used semi-sealed wet cells.

One important classification for batteries is by their life cycle. "Primary" batteries can produce current as soon as assembled, but once the active elements are consumed, they cannot be electrically recharged. The development of the lead-acid battery and subsequent "secondary" or "chargeable" types allowed energy to be restored to the cell, extending the life of permanently assembled cells. The introduction of nickel and lithium based batteries in the latter half of the 20th century made the development of innumerable portable electronic devices feasible, from powerful flashlight

A flashlight ( US, Canada) or torch ( UK, Australia) is a portable hand-held electric lamp. Formerly, the light source typically was a miniature incandescent light bulb, but these have been displaced by light-emitting diodes (LEDs) since th ...

s to mobile phones. Very large stationary batteries find some applications in grid energy storage

Grid energy storage (also called large-scale energy storage) is a collection of methods used for energy storage on a large scale within an electrical power grid. Electrical energy is stored during times when electricity is plentiful and inexp ...

, helping to stabilize electric power distribution networks.

Invention

From the mid 18th century on, before there were batteries, experimenters usedLeyden jar

A Leyden jar (or Leiden jar, or archaically, sometimes Kleistian jar) is an electrical component that stores a high-voltage electric charge (from an external source) between electrical conductors on the inside and outside of a glass jar. It typ ...

s to store electrical charge. As an early form of capacitor

A capacitor is a device that stores electrical energy in an electric field by virtue of accumulating electric charges on two close surfaces insulated from each other. It is a passive electronic component with two terminals.

The effect of a c ...

, Leyden jars, unlike batteries, stored their charge physically and would release it all at once. Many experimenters took to hooking several Leyden jars together to create a stronger charge and one of them, the colonial America inventor Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

, may have been the first to call his grouping an ''"electrical battery"'', a play on the military term for weapons functioning together.

Based on some findings by Luigi Galvani

Luigi Galvani (, also ; ; la, Aloysius Galvanus; 9 September 1737 – 4 December 1798) was an Italian physician, physicist, biologist and philosopher, who studied animal electricity. In 1780, he discovered that the muscles of dead frogs' legs ...

, Alessandro Volta

Alessandro Giuseppe Antonio Anastasio Volta (, ; 18 February 1745 – 5 March 1827) was an Italian physicist, chemist and lay Catholic who was a pioneer of electricity and power who is credited as the inventor of the electric battery and the ...

, a friend and fellow scientist, believed observed electrical phenomena were caused by two different metals joined together by a moist intermediary. He verified this hypothesis through experiments and published the results in 1791. In 1800, Volta invented the first true battery, storing and releasing a charge through a chemical reaction instead of physically, which came to be known as the voltaic pile

upright=1.2, Schematic diagram of a copper–zinc voltaic pile. The copper and zinc discs were separated by cardboard or felt spacers soaked in salt water (the electrolyte). Volta's original piles contained an additional zinc disk at the bottom, ...

. The voltaic pile consisted of pairs of copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish- ...

and zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic t ...

discs piled on top of each other, separated by a layer of cloth or cardboard soaked in brine

Brine is a high-concentration solution of salt (NaCl) in water (H2O). In diverse contexts, ''brine'' may refer to the salt solutions ranging from about 3.5% (a typical concentration of seawater, on the lower end of that of solutions used fo ...

(i.e., the electrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon ...

). Unlike the Leyden jar

A Leyden jar (or Leiden jar, or archaically, sometimes Kleistian jar) is an electrical component that stores a high-voltage electric charge (from an external source) between electrical conductors on the inside and outside of a glass jar. It typ ...

, the voltaic pile produced continuous electricity and stable current, and lost little charge over time when not in use, though his early models could not produce a voltage strong enough to produce sparks. He experimented with various metals and found that zinc and silver gave the best results.

Volta believed the current was the result of two different materials simply touching each other – an obsolete scientific theory

This list catalogs well-accepted theories in science and pre-scientific natural philosophy and natural history which have since been superseded by scientific theories. Many discarded explanations were once supported by a scientific consensus, ...

known as contact tension

Contact electrification is a phrase that describes a phenomenon whereby surfaces become electrically charged, via a number of possible mechanisms, when two or more objects come within close proximity of one another. When two objects are "touched" ...

– and not the result of chemical reactions. As a consequence, he regarded the corrosion of the zinc plates as an unrelated flaw that could perhaps be fixed by changing the materials somehow. However, no scientist ever succeeded in preventing this corrosion. In fact, it was observed that the corrosion was faster when a higher current was drawn. This suggested that the corrosion was actually integral to the battery's ability to produce a current. This, in part, led to the rejection of Volta's contact tension theory in favor of the electrochemical theory. Volta's illustrations of his Crown of Cups and voltaic pile have extra metal disks, now known to be unnecessary, on both the top and bottom. The figure associated with this section, of the zinc-copper voltaic pile, has the modern design, an indication that "contact tension" is not the source of electromotive force

In electromagnetism and electronics, electromotive force (also electromotance, abbreviated emf, denoted \mathcal or ) is an energy transfer to an electric circuit per unit of electric charge, measured in volts. Devices called electrical '' t ...

for the voltaic pile.

Volta's original pile models had some technical flaws, one of them involving the electrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon ...

leaking and causing short-circuits due to the weight of the discs compressing the brine-soaked cloth. A Scotsman named William Cruickshank solved this problem by laying the elements in a box instead of piling them in a stack. This was known as the trough battery. Volta himself invented a variant that consisted of a chain of cups filled with a salt solution, linked together by metallic arcs dipped into the liquid. This was known as the Crown of Cups. These arcs were made of two different metals (e.g., zinc and copper) soldered together. This model also proved to be more efficient than his original piles, though it did not prove as popular.

hydrogen

Hydrogen is the chemical element with the symbol H and atomic number 1. Hydrogen is the lightest element. At standard conditions hydrogen is a gas of diatomic molecules having the formula . It is colorless, odorless, tasteless, non-toxi ...

bubbles forming on the copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish- ...

, which steadily increased the internal resistance of the battery (this effect, called ''polarization'', is counteracted in modern cells by additional measures). The other was a phenomenon called ''local action'', wherein minute short-circuits would form around impurities in the zinc, causing the zinc to degrade. The latter problem was solved in 1835 by the English inventor William Sturgeon

William Sturgeon (22 May 1783 – 4 December 1850) was an English physicist and inventor who made the first electromagnets, and invented the first practical British electric motor.

Early life

Sturgeon was born on 22 May 1783 in Whittington ...

, who found that amalgamated zinc, whose surface had been treated with some mercury, didn't suffer from local action.

Despite its flaws, Volta's batteries provide a steadier current than Leyden jars, and made possible many new experiments and discoveries, such as the first electrolysis of water

Electrolysis of water, also known as electrochemical water splitting, is the process of using electricity to decompose water into oxygen and hydrogen gas by electrolysis. Hydrogen gas released in this way can be used as hydrogen fuel, or re ...

by the English surgeon Anthony Carlisle and the English chemist William Nicholson.

First practical batteries

Daniell cell

An English professor of chemistry named John Frederic Daniell found a way to solve the hydrogen bubble problem in the Voltaic Pile by using a second electrolyte to consume the hydrogen produced by the first. In 1836, he invented the

An English professor of chemistry named John Frederic Daniell found a way to solve the hydrogen bubble problem in the Voltaic Pile by using a second electrolyte to consume the hydrogen produced by the first. In 1836, he invented the Daniell cell

The Daniell cell is a type of electrochemical cell invented in 1836 by John Frederic Daniell, a British chemist and meteorologist, and consists of a copper pot filled with a copper (II) sulfate solution, in which is immersed an unglazed earthe ...

, which consists of a copper pot filled with a copper sulfate Copper sulfate may refer to:

* Copper(II) sulfate

Copper(II) sulfate, also known as copper sulphate, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It forms hydrates , where ''n'' can range from 1 to 7. The pentahydrate (''n'' = 5), a brig ...

solution, in which is immersed an unglazed earthenware

Earthenware is glazed or unglazed nonvitreous pottery that has normally been fired below . Basic earthenware, often called terracotta, absorbs liquids such as water. However, earthenware can be made impervious to liquids by coating it with a ...

container filled with sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular fo ...

and a zinc electrode. The earthenware

Earthenware is glazed or unglazed nonvitreous pottery that has normally been fired below . Basic earthenware, often called terracotta, absorbs liquids such as water. However, earthenware can be made impervious to liquids by coating it with a ...

barrier is porous, which allows ions to pass through but keeps the solutions from mixing.

The Daniell cell was a great improvement over the existing technology used in the early days of battery development and was the first practical source of electricity. It provides a longer and more reliable current than the Voltaic cell. It is also safer and less corrosive. It has an operating voltage of roughly 1.1 volts. It soon became the industry standard for use, especially with the new telegraph

Telegraphy is the long-distance transmission of messages where the sender uses symbolic codes, known to the recipient, rather than a physical exchange of an object bearing the message. Thus flag semaphore is a method of telegraphy, whereas p ...

networks.

The Daniell cell was also used as the first working standard for definition of the volt

The volt (symbol: V) is the unit of electric potential, electric potential difference ( voltage), and electromotive force in the International System of Units (SI). It is named after the Italian physicist Alessandro Volta (1745–1827).

Def ...

, which is the unit of electromotive force

In electromagnetism and electronics, electromotive force (also electromotance, abbreviated emf, denoted \mathcal or ) is an energy transfer to an electric circuit per unit of electric charge, measured in volts. Devices called electrical '' t ...

.

Bird's cell

A version of the Daniell cell was invented in 1837 by the Guy's hospital physicianGolding Bird

Golding Bird (9 December 1814 – 27 October 1854) was a British medical doctor and a Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians. He became a great authority on kidney diseases and published a comprehensive paper on urolithiasis, urinary d ...

who used a plaster of Paris

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "r ...

barrier to keep the solutions separate. Bird's experiments with this cell were of some importance to the new discipline of electrometallurgy

Electrometallurgy is a method in metallurgy that uses electrical energy to produce metals by electrolysis. It is usually the last stage in metal production and is therefore preceded by pyrometallurgical or hydrometallurgical operations. The elect ...

.

Porous pot cell

The porous pot version of the Daniell cell was invented by

The porous pot version of the Daniell cell was invented by John Dancer

John Benjamin Dancer (8 October 1812 – 24 November 1887) was a British scientific instrument maker and inventor of microphotography. He also pioneered stereography.

Life

By 1835, he controlled his father's instrument making business in Li ...

, a Liverpool instrument maker, in 1838. It consists of a central zinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic t ...

anode

An anode is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the device. A common mnemonic ...

dipped into a porous earthenware pot containing a zinc sulfate

Zinc sulfate is an inorganic compound. It is used as a dietary supplement to treat zinc deficiency and to prevent the condition in those at high risk. Side effects of excess supplementation may include abdominal pain, vomiting, headache, and ...

solution. The porous

Porosity or void fraction is a measure of the void (i.e. "empty") spaces in a material, and is a fraction of the volume of voids over the total volume, between 0 and 1, or as a percentage between 0% and 100%. Strictly speaking, some tests measure ...

pot is, in turn, immersed in a solution of copper sulfate Copper sulfate may refer to:

* Copper(II) sulfate

Copper(II) sulfate, also known as copper sulphate, is an inorganic compound with the chemical formula . It forms hydrates , where ''n'' can range from 1 to 7. The pentahydrate (''n'' = 5), a brig ...

contained in a copper

Copper is a chemical element with the symbol Cu (from la, cuprum) and atomic number 29. It is a soft, malleable, and ductile metal with very high thermal and electrical conductivity. A freshly exposed surface of pure copper has a pinkish- ...

can, which acts as the cell's cathode

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic ''CCD'' for ''Cathode Current Departs''. A conventional current describes the direction in wh ...

. The use of a porous barrier allows ions to pass through but keeps the solutions from mixing.

Gravity cell

In the 1860s, a Frenchman named Callaud invented a variant of the Daniell cell called the gravity cell. This simpler version dispensed with the porous barrier. This reduces the internal resistance of the system and, thus, the battery yields a stronger current. It quickly became the battery of choice for the American and British telegraph networks, and was widely used until the 1950s.

The gravity cell consists of a glass jar, in which a copper cathode sits on the bottom and a zinc anode is suspended beneath the rim. Copper sulfate crystals are scattered around the cathode and then the jar is filled with distilled water. As the current is drawn, a layer of zinc sulfate solution forms at the top around the anode. This top layer is kept separate from the bottom copper sulfate layer by its lower density and by the polarity of the cell.

The zinc sulfate layer is clear in contrast to the deep blue copper sulfate layer, which allows a technician to measure the battery life with a glance. On the other hand, this setup means the battery can be used only in a stationary appliance, or else the solutions mix or spill. Another disadvantage is that a current has to be continually drawn to keep the two solutions from mixing by diffusion, so it is unsuitable for intermittent use.

In the 1860s, a Frenchman named Callaud invented a variant of the Daniell cell called the gravity cell. This simpler version dispensed with the porous barrier. This reduces the internal resistance of the system and, thus, the battery yields a stronger current. It quickly became the battery of choice for the American and British telegraph networks, and was widely used until the 1950s.

The gravity cell consists of a glass jar, in which a copper cathode sits on the bottom and a zinc anode is suspended beneath the rim. Copper sulfate crystals are scattered around the cathode and then the jar is filled with distilled water. As the current is drawn, a layer of zinc sulfate solution forms at the top around the anode. This top layer is kept separate from the bottom copper sulfate layer by its lower density and by the polarity of the cell.

The zinc sulfate layer is clear in contrast to the deep blue copper sulfate layer, which allows a technician to measure the battery life with a glance. On the other hand, this setup means the battery can be used only in a stationary appliance, or else the solutions mix or spill. Another disadvantage is that a current has to be continually drawn to keep the two solutions from mixing by diffusion, so it is unsuitable for intermittent use.

Poggendorff cell

The German scientistJohann Christian Poggendorff

Johann Christian Poggendorff (29 December 1796 – 24 January 1877), was a German physicist born in Hamburg. By far the greater and more important part of his work related to electricity and magnetism. Poggendorff is known for his electrostatic m ...

overcame the problems with separating the electrolyte and the depolariser using a porous earthenware pot in 1842. In the Poggendorff cell, sometimes called Grenet Cell due to the works of Eugene Grenet

Eugene may refer to:

People and fictional characters

* Eugene (given name), including a list of people and fictional characters with the given name

* Eugene (actress) (born 1981), Kim Yoo-jin, South Korean actress and former member of the si ...

around 1859, the electrolyte is dilute sulphuric acid and the depolariser is chromic acid. The two acids are physically mixed together, eliminating the porous pot. The positive electrode (cathode) is two carbon plates, with a zinc plate (negative or anode) positioned between them. Because of the tendency of the acid mixture to react with the zinc, a mechanism is provided to raise the zinc electrode clear of the acids.

The cell provides 1.9 volts. It was popular with experimenters for many years due to its relatively high voltage; greater ability to produce a consistent current and lack of any fumes, but the relative fragility of its thin glass enclosure and the necessity of having to raise the zinc plate when the cell is not in use eventually saw it fall out of favour. The cell was also known as the 'chromic acid cell', but principally as the 'bichromate cell'. This latter name came from the practice of producing the chromic acid by adding sulphuric acid to potassium dichromate, even though the cell itself contains no dichromate.

The Fuller cell was developed from the Poggendorff cell. Although the chemistry is principally the same, the two acids are once again separated by a porous container and the zinc is treated with mercury to form an amalgam.

Grove cell

The Welshman William Robert Grove invented the Grove cell in 1839. It consists of azinc

Zinc is a chemical element with the symbol Zn and atomic number 30. Zinc is a slightly brittle metal at room temperature and has a shiny-greyish appearance when oxidation is removed. It is the first element in group 12 (IIB) of the periodic t ...

anode dipped in sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular fo ...

and a platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

cathode

A cathode is the electrode from which a conventional current leaves a polarized electrical device. This definition can be recalled by using the mnemonic ''CCD'' for ''Cathode Current Departs''. A conventional current describes the direction in wh ...

dipped in nitric acid

Nitric acid is the inorganic compound with the formula . It is a highly corrosive mineral acid. The compound is colorless, but older samples tend to be yellow cast due to decomposition into oxides of nitrogen. Most commercially available nitri ...

, separated by porous earthenware

Earthenware is glazed or unglazed nonvitreous pottery that has normally been fired below . Basic earthenware, often called terracotta, absorbs liquids such as water. However, earthenware can be made impervious to liquids by coating it with a ...

. The Grove cell provides a high current and nearly twice the voltage of the Daniell cell, which made it the favoured cell of the American telegraph networks for a time. However, it gives off poisonous nitric oxide

Nitric oxide (nitrogen oxide or nitrogen monoxide) is a colorless gas with the formula . It is one of the principal oxides of nitrogen. Nitric oxide is a free radical: it has an unpaired electron, which is sometimes denoted by a dot in its ...

fumes when operated. The voltage also drops sharply as the charge diminishes, which became a liability as telegraph networks grew more complex. Platinum

Platinum is a chemical element with the symbol Pt and atomic number 78. It is a dense, malleable, ductile, highly unreactive, precious, silverish-white transition metal. Its name originates from Spanish , a diminutive of "silver".

Pla ...

was and still is very expensive.

Dun cell

Alfred Dun 1885, nitro-muriatic acid () – iron and carbon:In the new element there can be used advantageously as exciting-liquid in the first case such solutions as have in a concentrated condition great depolarizing-power, which effect the whole depolarization chemically without necessitating the mechanical expedient of increased carbon surface. It is preferred to use iron as the positive electrode, and as exciting-liquid nitro muriatic acid (), the mixture consisting of muriatic and nitric acids. The nitro-muriatic acid, as explained above, serves for filling both cells. For the carbon-cells it is used strong or very slightly diluted, but for the other cells very diluted, (about one-twentieth, or at the most one-tenth). The element containing in one cell carbon and concentrated nitro-muriatic acid and in the other cell iron and dilute nitro-muriatic acid remains constant for at least twenty hours when employed for electric incandescent lighting.

Rechargeable batteries and dry cells

Lead-acid

Up to this point, all existing batteries would be permanently drained when all their chemical reactants were spent. In 1859,

Up to this point, all existing batteries would be permanently drained when all their chemical reactants were spent. In 1859, Gaston Planté

Gaston Planté (22 April 1834 – 21 May 1889) was a French physicist who invented the lead–acid battery in 1859. This type battery was developed as the first rechargeable electric battery marketed for commercial use and it is widely used in au ...

invented the lead–acid battery

The lead–acid battery is a type of rechargeable battery first invented in 1859 by French physicist Gaston Planté. It is the first type of rechargeable battery ever created. Compared to modern rechargeable batteries, lead–acid batteries have ...

, the first-ever battery that could be recharged by passing a reverse current through it. A lead-acid cell consists of a lead anode

An anode is an electrode of a polarized electrical device through which conventional current enters the device. This contrasts with a cathode, an electrode of the device through which conventional current leaves the device. A common mnemonic ...

and a lead dioxide

Lead(IV) oxide is the inorganic compound with the formula PbO2. It is an oxide where lead is in an oxidation state of +4. It is a dark-brown solid which is insoluble in water. It exists in two crystalline forms. It has several important applicatio ...

cathode immersed in sulfuric acid

Sulfuric acid ( American spelling and the preferred IUPAC name) or sulphuric acid ( Commonwealth spelling), known in antiquity as oil of vitriol, is a mineral acid composed of the elements sulfur, oxygen and hydrogen, with the molecular fo ...

. Both electrodes react with the acid to produce lead sulfate, but the reaction at the lead anode releases electrons whilst the reaction at the lead dioxide consumes them, thus producing a current. These chemical reactions can be reversed by passing a reverse current through the battery, thereby recharging it.

Planté's first model consisted of two lead sheets separated by rubber strips and rolled into a spiral. His batteries were first used to power the lights in train carriages while stopped at a station. In 1881, Camille Alphonse Faure invented an improved version that consists of a lead grid lattice into which is pressed a lead oxide paste, forming a plate. Multiple plates can be stacked for greater performance. This design is easier to mass-produce.

Compared to other batteries, Planté's is rather heavy and bulky for the amount of energy it can hold. However, it can produce remarkably large currents in surges, because it has very low internal resistance, meaning that a single battery can be used to power multiple circuits.

The lead-acid battery is still used today in automobiles and other applications where weight is not a big factor. The basic principle has not changed since 1859. In the early 1930s, a gel electrolyte (instead of a liquid) produced by adding silica

Silicon dioxide, also known as silica, is an oxide of silicon with the chemical formula , most commonly found in nature as quartz and in various living organisms. In many parts of the world, silica is the major constituent of sand. Silica is ...

to a charged cell was used in the LT battery of portable vacuum-tube radios. In the 1970s, "sealed" versions became common (commonly known as a " gel cell" or " SLA"), allowing the battery to be used in different positions without failure or leakage.

Today cells are classified as "primary" if they produce a current only until their chemical reactant

In chemistry, a reagent ( ) or analytical reagent is a substance or compound added to a system to cause a chemical reaction, or test if one occurs. The terms ''reactant'' and ''reagent'' are often used interchangeably, but reactant specifies a ...

s are exhausted, and "secondary" if the chemical reactions can be reversed by recharging the cell. The lead-acid cell was the first "secondary" cell.

Leclanché cell

In 1866, Georges Leclanché invented a battery that consists of a zinc anode and a

In 1866, Georges Leclanché invented a battery that consists of a zinc anode and a manganese dioxide

Manganese dioxide is the inorganic compound with the formula . This blackish or brown solid occurs naturally as the mineral pyrolusite, which is the main ore of manganese and a component of manganese nodules. The principal use for is for dry-cel ...

cathode wrapped in a porous material, dipped in a jar of ammonium chloride solution. The manganese dioxide cathode has a little carbon mixed into it as well, which improves conductivity and absorption. It provided a voltage of 1.4 volts. This cell achieved very quick success in telegraphy, signaling, and electric bell work.

The dry cell

upLine art drawing of a dry cell: 1. brass cap, 2. plastic seal, 3. expansion space, 4. porous cardboard, 5. zinc can, 6. carbon rod, 7. chemical mixture

A dry cell is a type of electric battery, commonly used for portable electrical devices. Unl ...

form was used to power early telephones—usually from an adjacent wooden box affixed to fit batteries before telephones could draw power from the telephone line itself. The Leclanché cell can not provide a sustained current for very long. In lengthy conversations, the battery would run down, rendering the conversation inaudible. This is because certain chemical reactions in the cell increase the internal resistance and, thus, lower the voltage.

Zinc-carbon cell, the first dry cell

Many experimenters tried to immobilize the electrolyte of an electrochemical cell to make it more convenient to use. TheZamboni pile

The Zamboni pile (also referred to as a ''Duluc Dry Pile'') is an early electric battery, invented by Giuseppe Zamboni in 1812.

A Zamboni pile is an " electrostatic battery" and is constructed from discs of silver foil, zinc foil, and paper. ...

of 1812 is a high-voltage dry battery but capable of delivering only minute currents. Various experiments were made with cellulose

Cellulose is an organic compound with the formula , a polysaccharide consisting of a linear chain of several hundred to many thousands of β(1→4) linked D-glucose units. Cellulose is an important structural component of the primary cell w ...

, sawdust

Sawdust (or wood dust) is a by-product or waste product of woodworking operations such as sawing, sanding, milling, planing, and routing. It is composed of small chippings of wood. These operations can be performed by woodworking machiner ...

, spun glass, asbestos

Asbestos () is a naturally occurring fibrous silicate mineral. There are six types, all of which are composed of long and thin fibrous crystals, each fibre being composed of many microscopic "fibrils" that can be released into the atmosphere ...

fibers, and gelatine

Gelatin or gelatine (from la, gelatus meaning "stiff" or "frozen") is a translucent, colorless, flavorless food ingredient, commonly derived from collagen taken from animal body parts. It is brittle when dry and rubbery when moist. It may also ...

.

In 1886, Carl Gassner

Carl Gassner is a German physician (17 November 1855 in Mainz; † 31 January 1942), scientist and inventor, better known to have contributed to improve the Leclanché cell and to have fostered the development of the first dry cell, also kno ...

obtained a German patent on a variant of the Leclanché cell, which came to be known as the dry cell

upLine art drawing of a dry cell: 1. brass cap, 2. plastic seal, 3. expansion space, 4. porous cardboard, 5. zinc can, 6. carbon rod, 7. chemical mixture

A dry cell is a type of electric battery, commonly used for portable electrical devices. Unl ...

because it does not have a free liquid electrolyte. Instead, the ammonium chloride is mixed with plaster of Paris

Plaster is a building material used for the protective or decorative coating of walls and ceilings and for moulding and casting decorative elements. In English, "plaster" usually means a material used for the interiors of buildings, while "r ...

to create a paste, with a small amount of zinc chloride

Zinc chloride is the name of inorganic chemical compounds with the formula ZnCl2 and its hydrates. Zinc chlorides, of which nine crystalline forms are known, are colorless or white, and are highly soluble in water. This salt is hygroscopic and e ...

added in to extend the shelf life. The manganese dioxide

Manganese dioxide is the inorganic compound with the formula . This blackish or brown solid occurs naturally as the mineral pyrolusite, which is the main ore of manganese and a component of manganese nodules. The principal use for is for dry-cel ...

cathode is dipped in this paste, and both are sealed in a zinc shell, which also acts as the anode. In November 1887, he obtained for the same device.

Unlike previous wet cells, Gassner's dry cell is more solid, does not require maintenance, does not spill, and can be used in any orientation. It provides a potential of 1.5 volts. The first mass-produced model was the Columbia dry cell, first marketed by the National Carbon Company in 1896. The NCC improved Gassner's model by replacing the plaster of Paris with coiled cardboard

Cardboard is a generic term for heavy paper-based products. The construction can range from a thick paper known as paperboard to corrugated fiberboard which is made of multiple plies of material. Natural cardboards can range from grey to light br ...

, an innovation that left more space for the cathode and made the battery easier to assemble. It was the first convenient battery for the masses and made portable electrical devices practical, and led directly to the invention of the flashlight

A flashlight ( US, Canada) or torch ( UK, Australia) is a portable hand-held electric lamp. Formerly, the light source typically was a miniature incandescent light bulb, but these have been displaced by light-emitting diodes (LEDs) since th ...

.

The zinc–carbon battery

A zinc–carbon battery (or carbon zinc battery in U.S. English) is a dry cell primary battery that provides direct electric current from the electrochemical reaction between zinc and manganese dioxide (MnO2) in the presence of an electrolyte. It ...

(as it came to be known) is still manufactured today.

In parallel, in 1887 Wilhelm Hellesen developed his own dry cell design. It has been claimed that Hellesen's design preceded that of Gassner.

In 1887, a dry-battery was developed by Sakizō Yai ( 屋井 先蔵) of Japan, then patented in 1892. In 1893, Sakizō Yai's dry-battery was exhibited in World's Columbian Exposition

The World's Columbian Exposition (also known as the Chicago World's Fair) was a world's fair held in Chicago in 1893 to celebrate the 400th anniversary of Christopher Columbus's arrival in the New World in 1492. The centerpiece of the Fair, ...

and commanded considerable international attention.

NiCd, the first alkaline battery

In 1899, a Swedish scientist namedWaldemar Jungner

Ernst Waldemar Jungner (19 June 1869 – 30 August 1924) was a Swedish inventor and engineer. In 1898 he invented the nickel-iron electric storage battery (NiFe), the nickel-cadmium battery (NiCd), and the rechargeable alkaline silver-cadmium ...

invented the nickel–cadmium battery

The nickel–cadmium battery (Ni–Cd battery or NiCad battery) is a type of rechargeable battery using nickel oxide hydroxide and metallic cadmium as electrodes. The abbreviation ''Ni-Cd'' is derived from the chemical symbols of nickel (Ni) an ...

, a rechargeable battery that has nickel

Nickel is a chemical element with symbol Ni and atomic number 28. It is a silvery-white lustrous metal with a slight golden tinge. Nickel is a hard and ductile transition metal. Pure nickel is chemically reactive but large pieces are slow to ...

and cadmium

Cadmium is a chemical element with the symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12, zinc and mercury. Like zinc, it demonstrates oxidation state +2 in most of ...

electrodes in a potassium hydroxide

Potassium hydroxide is an inorganic compound with the formula K OH, and is commonly called caustic potash.

Along with sodium hydroxide (NaOH), KOH is a prototypical strong base. It has many industrial and niche applications, most of which exploi ...

solution; the first battery to use an alkaline

In chemistry, an alkali (; from ar, القلوي, al-qaly, lit=ashes of the saltwort) is a basic, ionic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a s ...

electrolyte. It was commercialized in Sweden in 1910 and reached the United States in 1946. The first models were robust and had significantly better energy density than lead-acid batteries, but were much more expensive.

20th century: new technologies and ubiquity

Nickel-iron

Waldemar Jungner patented a

Waldemar Jungner patented a nickel–iron battery

The nickel–iron battery (NiFe battery) is a rechargeable battery having nickel(III) oxide-hydroxide positive plates and iron negative plates, with an electrolyte of potassium hydroxide. The active materials are held in nickel-plated steel t ...

in 1899, the same year as his Ni-Cad battery patent, but found it to be inferior to its cadmium counterpart and, as a consequence, never bothered developing it. It produced a lot more hydrogen gas when being charged, meaning it could not be sealed, and the charging process was less efficient (it was, however, cheaper).

Seeing a way to make a profit in the already competitive lead-acid battery market, Thomas Edison

Thomas Alva Edison (February 11, 1847October 18, 1931) was an American inventor and businessman. He developed many devices in fields such as electric power generation, mass communication, sound recording, and motion pictures. These invent ...

worked in the 1890s on developing an alkali

In chemistry, an alkali (; from ar, القلوي, al-qaly, lit=ashes of the saltwort) is a basic, ionic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a s ...

ne based battery that he could get a patent on. Edison thought if he produced lightweight and durable battery electric cars would become the standard, with his firm as its main battery vendor. After many experiments, and probably borrowing from Jungner's design, he patented an alkaline based nickel–iron battery in 1901. However, customers found his first model of the alkaline nickel–iron battery to be prone to leakage leading to short battery life, and it did not outperform the lead-acid cell by much either. Although Edison was able to produce a more reliable and powerful model seven years later, by this time the inexpensive and reliable Model T Ford

The Ford Model T is an automobile that was produced by Ford Motor Company from October 1, 1908, to May 26, 1927. It is generally regarded as the first affordable automobile, which made car travel available to middle-class Americans. The relat ...

had made gasoline engine cars the standard. Nevertheless, Edison's battery achieved great success in other applications such as electric and diesel-electric rail vehicles, providing backup power for railroad crossing signals, or to provide power for the lamps used in mines.

Common alkaline batteries

Until the late 1950s, thezinc–carbon battery

A zinc–carbon battery (or carbon zinc battery in U.S. English) is a dry cell primary battery that provides direct electric current from the electrochemical reaction between zinc and manganese dioxide (MnO2) in the presence of an electrolyte. It ...

continued to be a popular primary cell battery, but its relatively low battery life hampered sales. The Canadian engineer Lewis Urry, working for the Union Carbide

Union Carbide Corporation is an American chemical corporation wholly owned subsidiary (since February 6, 2001) by Dow Chemical Company. Union Carbide produces chemicals and polymers that undergo one or more further conversions by customers befor ...

, first at the National Carbon Co. in Ontario and, by 1955, at the National Carbon Company Parma Research Laboratory in Cleveland

Cleveland ( ), officially the City of Cleveland, is a city in the U.S. state of Ohio and the county seat of Cuyahoga County. Located in the northeastern part of the state, it is situated along the southern shore of Lake Erie, across the U ...

, Ohio

Ohio () is a state in the Midwestern region of the United States. Of the fifty U.S. states, it is the 34th-largest by area, and with a population of nearly 11.8 million, is the seventh-most populous and tenth-most densely populated. The s ...

, was tasked with finding a way to extend the life of zinc-carbon batteries. Building on earlier work by Edison, Urry decided instead that alkaline batteries held more promise. Until then, longer-lasting alkaline

In chemistry, an alkali (; from ar, القلوي, al-qaly, lit=ashes of the saltwort) is a basic, ionic salt of an alkali metal or an alkaline earth metal. An alkali can also be defined as a base that dissolves in water. A solution of a s ...

batteries were unfeasibly expensive. Urry's battery consists of a manganese dioxide

Manganese dioxide is the inorganic compound with the formula . This blackish or brown solid occurs naturally as the mineral pyrolusite, which is the main ore of manganese and a component of manganese nodules. The principal use for is for dry-cel ...

cathode and a powdered zinc anode with an alkaline electrolyte

An electrolyte is a medium containing ions that is electrically conducting through the movement of those ions, but not conducting electrons. This includes most soluble salts, acids, and bases dissolved in a polar solvent, such as water. Upon ...

. Using powdered zinc gives the anode a greater surface area. These batteries were put on the market in 1959.

Nickel-hydrogen and nickel metal-hydride

The nickel–hydrogen battery entered the market as an energy-storage subsystem for commercialcommunication satellite

A communications satellite is an artificial satellite that relays and amplifies radio telecommunication signals via a transponder; it creates a communication channel between a source transmitter and a receiver at different locations on Earth. ...

s.

The first consumer grade nickel–metal hydride batteries (NiMH) for smaller applications appeared on the market in 1989 as a variation of the 1970s nickel–hydrogen battery. NiMH batteries tend to have longer lifespans than NiCd batteries (and their lifespans continue to increase as manufacturers experiment with new alloys) and, since cadmium

Cadmium is a chemical element with the symbol Cd and atomic number 48. This soft, silvery-white metal is chemically similar to the two other stable metals in group 12, zinc and mercury. Like zinc, it demonstrates oxidation state +2 in most of ...

is toxic, NiMH batteries are less damaging to the environment.

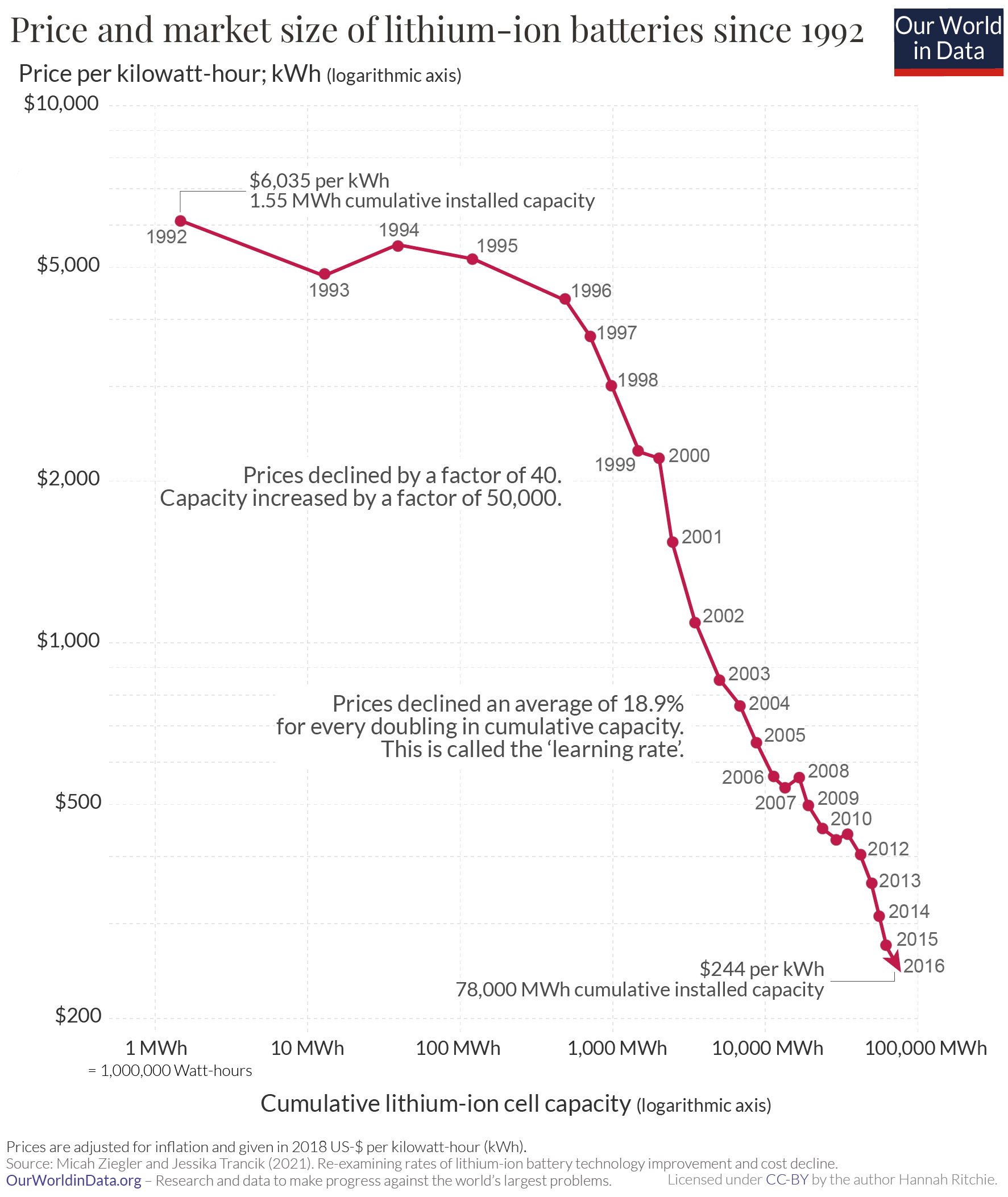

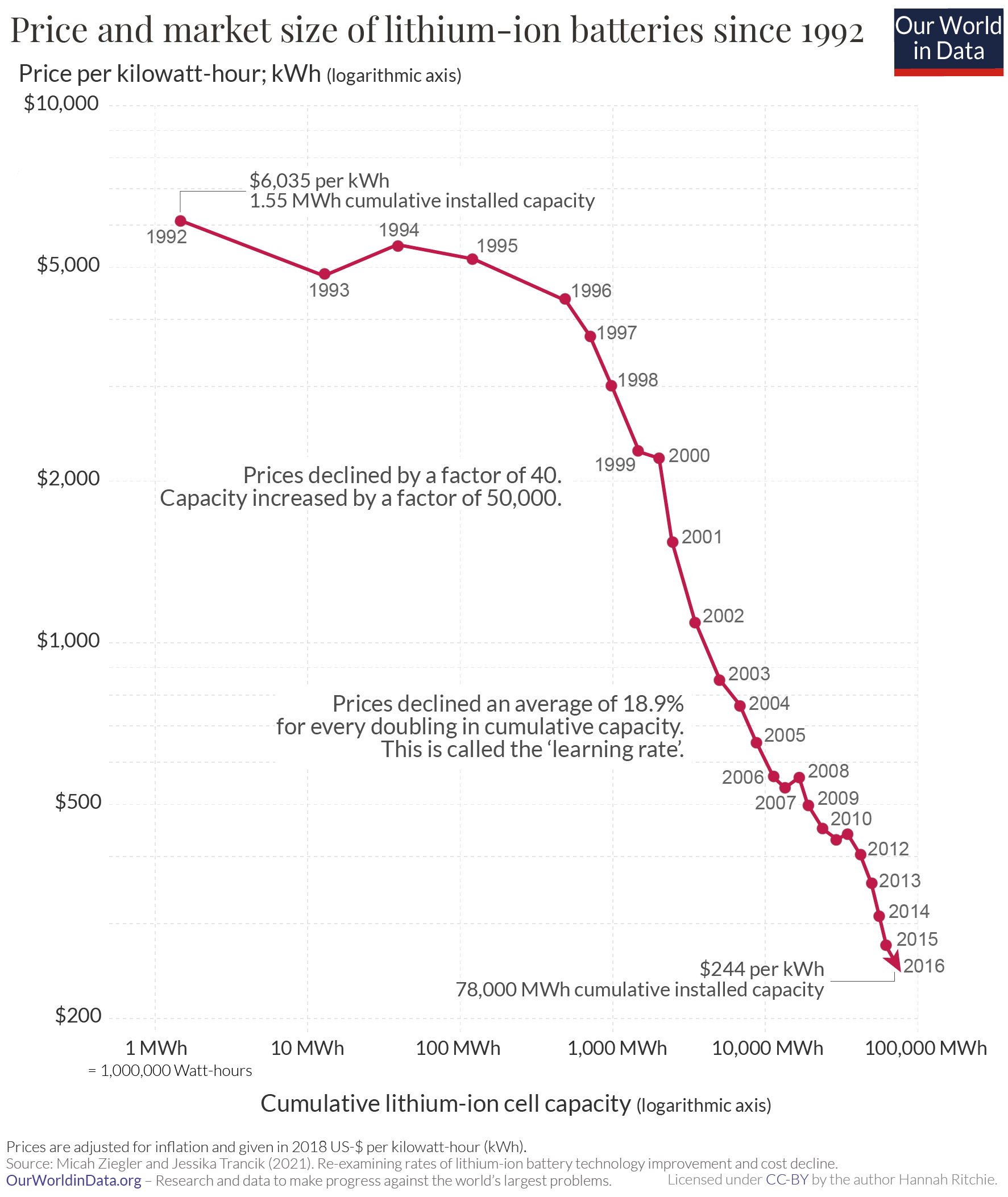

Lithium and lithium-ion batteries

Lithium

Lithium (from el, λίθος, lithos, lit=stone) is a chemical element with the symbol Li and atomic number 3. It is a soft, silvery-white alkali metal. Under standard conditions, it is the least dense metal and the least dense solid e ...

is the metal with lowest density and with the greatest electrochemical potential

In electrochemistry, the electrochemical potential (ECP), ', is a thermodynamic measure of chemical potential that does not omit the energy contribution of electrostatics. Electrochemical potential is expressed in the unit of J/ mol.

Introductio ...

and energy-to-weight ratio. The low atomic weight and small size of its ions also speeds its diffusion, suggesting that it would make an ideal material for batteries. Experimentation with lithium batteries began in 1912 under American physical chemist Gilbert N. Lewis, but commercial lithium batteries did not come to market until the 1970s in the form of the lithium-ion battery

A lithium-ion or Li-ion battery is a type of rechargeable battery which uses the reversible reduction of lithium ions to store energy. It is the predominant battery type used in portable consumer electronics and electric vehicles. It also ...

. Three volt lithium primary cells such as the CR123A type and three volt button cells are still widely used, especially in cameras and very small devices.

Three important developments regarding lithium batteries occurred in the 1980s. In 1980, an American chemist, John B. Goodenough

John Bannister Goodenough ( ; born July 25, 1922) is an American materials scientist, a solid-state physicist, and a Nobel laureate in chemistry. He is a professor of Mechanical, Materials Science, and Electrical Engineering at the University ...

, discovered the LiCoO2 (Lithium cobalt oxide

Lithium cobalt oxide, sometimes called lithium cobaltateA. L. Emelina, M. A. Bykov, M. L. Kovba, B. M. Senyavin, E. V. Golubina (2011), "Thermochemical properties of lithium cobaltate". ''Russian Journal of Physical Chemistry'', volume 85, issue ...

) cathode (positive lead) and a Moroccan research scientist, Rachid Yazami, discovered the graphite

Graphite () is a crystalline form of the element carbon. It consists of stacked layers of graphene. Graphite occurs naturally and is the most stable form of carbon under standard conditions. Synthetic and natural graphite are consumed on lar ...

anode (negative lead) with the solid electrolyte. In 1981, Japanese chemists Tokio Yamabe and Shizukuni Yata discovered a novel nano-carbonacious-PAS (polyacene) and found that it was very effective for the anode in the conventional liquid electrolyte. This led a research team managed by Akira Yoshino of Asahi Chemical, Japan, to build the first lithium-ion battery

A lithium-ion or Li-ion battery is a type of rechargeable battery which uses the reversible reduction of lithium ions to store energy. It is the predominant battery type used in portable consumer electronics and electric vehicles. It also ...

prototype in 1985, a rechargeable and more stable version of the lithium battery; Sony

, commonly stylized as SONY, is a Japanese multinational conglomerate corporation headquartered in Minato, Tokyo, Japan. As a major technology company, it operates as one of the world's largest manufacturers of consumer and professional ...

commercialized the lithium-ion battery in 1991.

In 1997, the lithium polymer battery

A lithium polymer battery, or more correctly lithium-ion polymer battery (abbreviated as LiPo, LIP, Li-poly, lithium-poly and others), is a rechargeable battery of lithium-ion technology using a polymer electrolyte instead of a liquid electro ...

was released by Sony and Asahi Kasei. These batteries hold their electrolyte in a solid polymer composite instead of in a liquid solvent, and the electrodes and separators are laminated to each other. The latter difference allows the battery to be encased in a flexible wrapping instead of in a rigid metal casing, which means such batteries can be specifically shaped to fit a particular device. This advantage has favored lithium polymer batteries in the design of portable electronic devices such as mobile phones and personal digital assistant

A personal digital assistant (PDA), also known as a handheld PC, is a variety mobile device which functions as a personal information manager. PDAs have been mostly displaced by the widespread adoption of highly capable smartphones, in part ...

s, and of radio-controlled aircraft

A radio-controlled aircraft (often called RC aircraft or RC plane) is a small flying machine that is controlled remotely by an operator on the ground using a hand-held radio transmitter. The transmitter continuously communicates with a receiver ( ...

, as such batteries allow for a more flexible and compact design. They generally have a lower energy density

In physics, energy density is the amount of energy stored in a given system or region of space per unit volume. It is sometimes confused with energy per unit mass which is properly called specific energy or .

Often only the ''useful'' or ex ...

than normal lithium-ion batteries.

In 2019, John B. Goodenough

John Bannister Goodenough ( ; born July 25, 1922) is an American materials scientist, a solid-state physicist, and a Nobel laureate in chemistry. He is a professor of Mechanical, Materials Science, and Electrical Engineering at the University ...

, M. Stanley Whittingham, and Akira Yoshino, were awarded the Nobel Prize in Chemistry

)

, image = Nobel Prize.png

, alt = A golden medallion with an embossed image of a bearded man facing left in profile. To the left of the man is the text "ALFR•" then "NOBEL", and on the right, the text (smaller) "NAT•" then "M ...

, for their development of lithium-ion batteries.

See also

*Baghdad Battery

The Baghdad Battery is the name given to a set of three artifacts which were found together: a ceramic pot, a tube of copper, and a rod of iron. It was discovered in present-day Khujut Rabu, Iraq in 1936, close to the metropolis of Ctesiphon, th ...

, an artifact that has similar properties to a modern battery

* Memory effect

* Comparison of battery types

* History of electrochemistry Electrochemistry, a branch of chemistry, went through several changes during its evolution from early principles related to magnets in the early 16th and 17th centuries, to complex theories involving conductivity, electric charge and mathematical m ...

* List of battery sizes

This is a list of the sizes, shapes, and general characteristics of some common primary and secondary battery types in household, automotive and light industrial use.

The complete nomenclature for a battery specifies size, chemistry, termina ...

* List of battery types

This list is a summary of notable electric battery types composed of one or more electrochemical cells. Three lists are provided in the table. The primary (non-rechargeable) and secondary (rechargeable) cell lists are lists of battery chemistry. ...

* '' Search for the Super Battery'', a 2017 PBS film

* Burgess Battery Company

Notes and references

{{reflist, 30em Battery (electricity) Battery Alessandro Volta Battery