History of the United States (1776–1789) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

Between 1776 and 1789

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, still meeting in Philadelphia, voted unanimously to declare independence as the "

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, still meeting in Philadelphia, voted unanimously to declare independence as the "

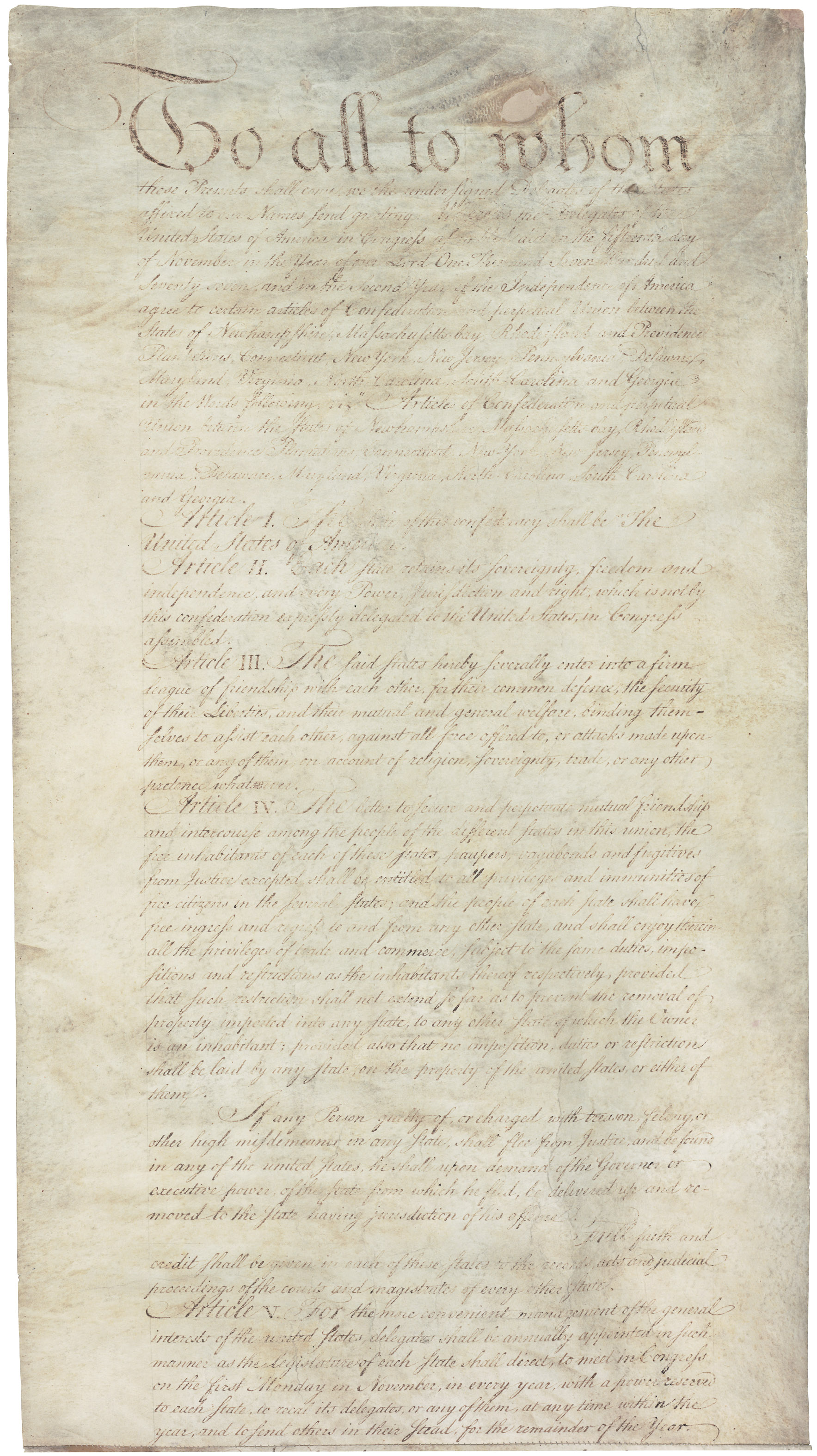

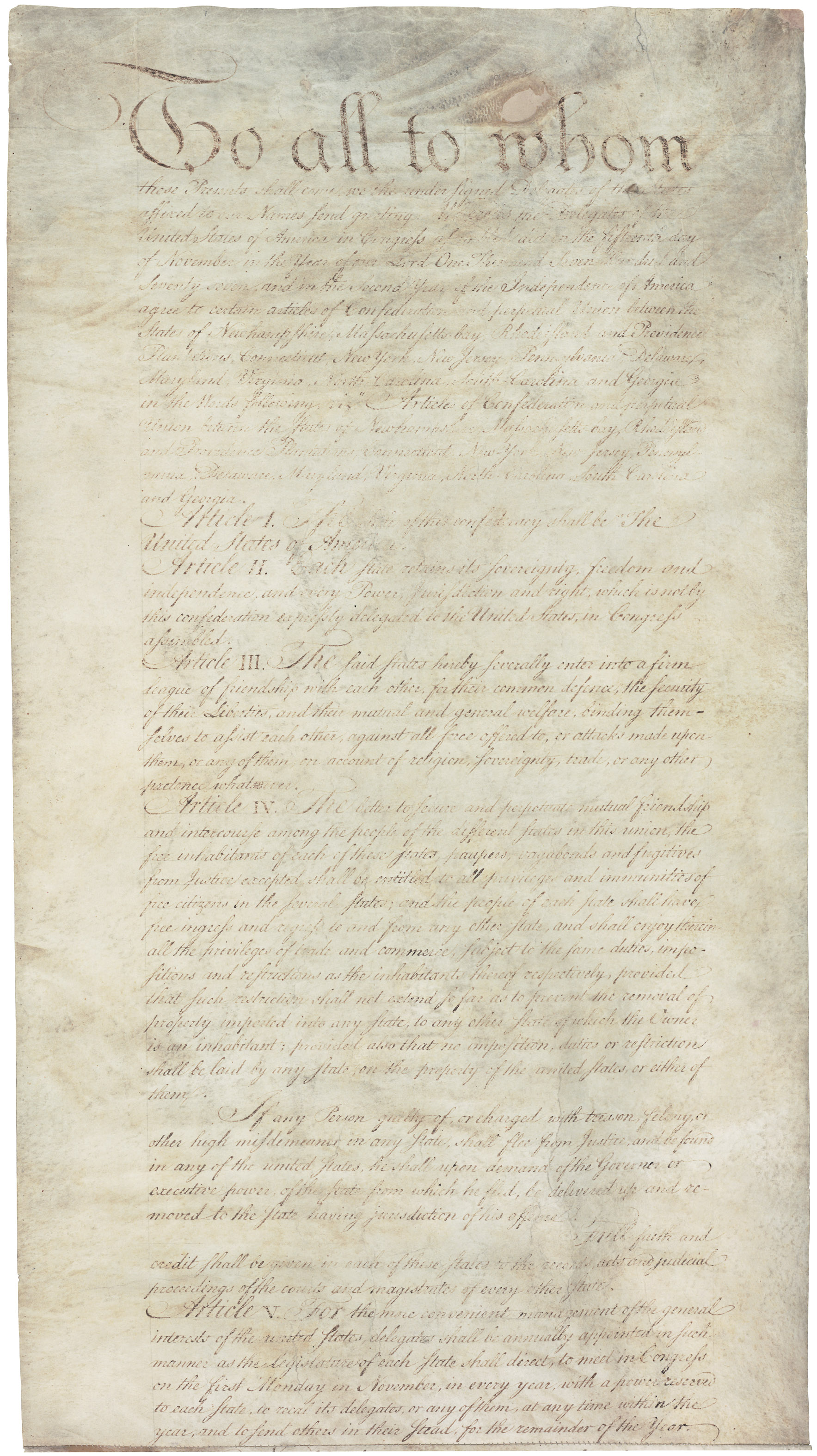

The Articles of Confederation were proposed by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, and they were ratified on March 1, 1781. It replaced the administrative boards and appellate courts that Congress had created during the early stages of the Revolutionary War. While the Articles of Confederation granted certain powers to the

The Articles of Confederation were proposed by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, and they were ratified on March 1, 1781. It replaced the administrative boards and appellate courts that Congress had created during the early stages of the Revolutionary War. While the Articles of Confederation granted certain powers to the

Economic conflict grew between the states as the Confederation period went on, and Congress had no power to prevent it. By 1786, many of the most prominent Americans in government were expressing concerns that the government under the Articles of Confederation was not sufficient. It lacked both the economic and military security that had previously been provided by Great Britain. The Annapolis Convention was held in 1786 to address trade issues, but it saw meager attendance with most states failing to send a delegate. The delegates from New Jersey had been authorized wide latitude by the state, and this was used to submit a proposal for a convention to reform the government entirely. In February 1787, Congress voted to hold the convention the following May, indicating a broad loss in confidence of the governmental system under the Articles of Confederation.

While there was not a clear objective before the convention, some delegates wished to establish a new central government that would have more power than Congress did under the Articles of Confederation.

Economic conflict grew between the states as the Confederation period went on, and Congress had no power to prevent it. By 1786, many of the most prominent Americans in government were expressing concerns that the government under the Articles of Confederation was not sufficient. It lacked both the economic and military security that had previously been provided by Great Britain. The Annapolis Convention was held in 1786 to address trade issues, but it saw meager attendance with most states failing to send a delegate. The delegates from New Jersey had been authorized wide latitude by the state, and this was used to submit a proposal for a convention to reform the government entirely. In February 1787, Congress voted to hold the convention the following May, indicating a broad loss in confidence of the governmental system under the Articles of Confederation.

While there was not a clear objective before the convention, some delegates wished to establish a new central government that would have more power than Congress did under the Articles of Confederation.

Those who advocated the Constitution took the name

Those who advocated the Constitution took the name

Settlement of

Settlement of

The American Revolution had large scale effects on the economies of the Thirteen Colonies. The Continental Congress did not have the power to levy taxes, so it depended on the newly formed state governments to raise funds, and they were forced to raise taxes to cover war expenditures. It also caused a

The American Revolution had large scale effects on the economies of the Thirteen Colonies. The Continental Congress did not have the power to levy taxes, so it depended on the newly formed state governments to raise funds, and they were forced to raise taxes to cover war expenditures. It also caused a

A distinct American culture separate from Britain had already developed by the 1750s. A plainness in fashion and speech was common, originating from

A distinct American culture separate from Britain had already developed by the 1750s. A plainness in fashion and speech was common, originating from

Historians categorize the time of the American Revolution as part of a broader

Historians categorize the time of the American Revolution as part of a broader

thirteen British colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of British colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Founded in the 17th and 18th centuri ...

emerged as a newly independent nation, the United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

. Fighting in the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

started between colonial militias and the British Army in 1775. The Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

issued the Declaration of Independence

A declaration of independence or declaration of statehood or proclamation of independence is an assertion by a polity in a defined territory that it is independent and constitutes a state. Such places are usually declared from part or all of the ...

on July 4, 1776. The Articles of Confederation were ratified in 1781 to form the Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

. Under the leadership of General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, the Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

and Navy

A navy, naval force, or maritime force is the branch of a nation's armed forces principally designated for naval warfare, naval and amphibious warfare; namely, lake-borne, riverine, littoral zone, littoral, or ocean-borne combat operations and ...

defeated the British military, securing the independence of the thirteen colonies. The Confederation period continued until 1789, when the states replaced the Articles of Confederation with the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

, which remains the fundamental governing law of the United States.

The 1780s marked an economic downturn for the United States due debts incurred during the Revolutionary War, Congress' inability to levy taxes, and significant inflation

In economics, inflation is an increase in the general price level of goods and services in an economy. When the general price level rises, each unit of currency buys fewer goods and services; consequently, inflation corresponds to a reductio ...

of the Continental dollar

Early American currency went through several stages of development during the colonial and post-Revolutionary history of the United States. John Hull was authorized by the Massachusetts legislature to make the earliest coinage of the colony (the ...

. Political essays such as ''Common Sense

''Common Sense'' is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political argu ...

'' and ''The Federalist Papers

''The Federalist Papers'' is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The co ...

'' had a major effect on American culture and public opinion. The Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

was created as the first federal territory in 1787, and a border dispute in this region prompted raids that escalated into the Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1786–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern ...

. The Revolution and the Confederation period are placed within the American Enlightenment

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual ferment in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution, and the creation of the United States of America. The American Enlightenment was ...

, a period in which Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

ideas grew popular and prompted scientific advancement.

Background

During the 17th and 18th centuries, British colonies in America were given considerable autonomy under the system ofsalutary neglect

In American history, salutary neglect was the 18th-century policy of the British Crown of avoiding the strict enforcement of parliamentary laws, especially trade laws, as long as British colonies remained loyal to the government and contributed t ...

. This autonomy was challenged in the 1760s by several acts of the Grenville ministry

The Grenville ministry was a British Government headed by George Grenville which served between 16 April 1763 and 13 July 1765. It was formed after the previous Prime Minister, the Earl of Bute, had resigned following fierce criticism of his sign ...

, including the Stamp Act 1765

The Stamp Act 1765, also known as the Duties in American Colonies Act 1765 (5 Geo. III c. 12), was an Act of the Parliament of Great Britain which imposed a direct tax on the British colonies in America and required that many printed materials i ...

and the Quartering Acts

The Quartering Acts were two or more Acts of Parliament of Great Britain, British Parliament requiring local governments of Britain's North American colonies to provide the British soldiers with housing and food. Each of the Quartering Acts was ...

. These acts provoked an ideological conflict between Great Britain

Great Britain is an island in the North Atlantic Ocean off the northwest coast of continental Europe. With an area of , it is the largest of the British Isles, the largest European island and the ninth-largest island in the world. It is ...

and the Thirteen Colonies

The Thirteen Colonies, also known as the Thirteen British Colonies, the Thirteen American Colonies, or later as the United Colonies, were a group of Kingdom of Great Britain, British Colony, colonies on the Atlantic coast of North America. Fo ...

regarding the nature of the Crown's authority over colonists. Protests by the colonists began as a demand for equal rights under the British constitution

The constitution of the United Kingdom or British constitution comprises the written and unwritten arrangements that establish the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland as a political body. Unlike in most countries, no attempt ...

, but as the dispute progressed, they took a decidedly republican

Republican can refer to:

Political ideology

* An advocate of a republic, a type of government that is not a monarchy or dictatorship, and is usually associated with the rule of law.

** Republicanism, the ideology in support of republics or agains ...

political viewpoint.

From the Stamp Act of 1765 onward, disputes with London escalated. Committees of correspondence

The committees of correspondence were, prior to the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, a collection of American political organizations that sought to coordinate opposition to British Parliament and, later, support for American independe ...

were formed between 1770 and 1773 to organize colonists that opposed British authority. Riots occurred in opposition to British taxation on tea, culminating in the Boston Tea Party

The Boston Tea Party was an American political and mercantile protest by the Sons of Liberty in Boston, Massachusetts, on December 16, 1773. The target was the Tea Act of May 10, 1773, which allowed the British East India Company to sell tea ...

on December 16, 1773 that saw dozens of men dumping massive amounts of British tea into the Boston Harbor

Boston Harbor is a natural harbor and estuary of Massachusetts Bay, and is located adjacent to the city of Boston, Massachusetts. It is home to the Port of Boston, a major shipping facility in the northeastern United States.

History

Since ...

. Great Britain responded with the even more controversial Intolerable Acts

The Intolerable Acts were a series of punitive laws passed by the British Parliament in 1774 after the Boston Tea Party. The laws aimed to punish Massachusetts colonists for their defiance in the Tea Party protest of the Tea Act, a tax measure ...

that enforced penalties on the colonies, and on Massachusetts

Massachusetts (Massachusett language, Massachusett: ''Muhsachuweesut assachusett writing systems, məhswatʃəwiːsət'' English: , ), officially the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, is the most populous U.S. state, state in the New England ...

in particular. This prompted the colonists to convene the First Continental Congress

The First Continental Congress was a meeting of delegates from 12 of the 13 British colonies that became the United States. It met from September 5 to October 26, 1774, at Carpenters' Hall in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, after the British Navy ...

on September 5, 1774 as a unified body to oppose British authority. The American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

began on April 19, 1775 with the Battles of Lexington and Concord

The Battles of Lexington and Concord were the first military engagements of the American Revolutionary War. The battles were fought on April 19, 1775, in Middlesex County, Province of Massachusetts Bay, within the towns of Lexington, Concord ...

.

The Second Continental Congress

The Second Continental Congress was a late-18th-century meeting of delegates from the Thirteen Colonies that united in support of the American Revolutionary War. The Congress was creating a new country it first named "United Colonies" and in 1 ...

met in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Sinc ...

, in the aftermath of armed clashes in April. With all thirteen colonies represented, it immediately began to organize itself as a central government with control over the diplomacy and instructed the colonies to write constitutions for themselves as states. On June 1775, George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of th ...

, a charismatic Virginia political leader with combat experience, was unanimously appointed commander of a newly organized Continental Army

The Continental Army was the army of the United Colonies (the Thirteen Colonies) in the Revolutionary-era United States. It was formed by the Second Continental Congress after the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, and was establis ...

. The Boston campaign

The Boston campaign was the opening campaign of the American Revolutionary War, taking place primarily in the Province of Massachusetts Bay. The campaign began with the Battles of Lexington and Concord on April 19, 1775, in which the local coloni ...

continued with the Continental Army besieging British-occupied Boston until the British retreated to Halifax, Nova Scotia

Halifax is the capital and largest municipality of the Canadian province of Nova Scotia, and the largest municipality in Atlantic Canada. As of the 2021 Census, the municipal population was 439,819, with 348,634 people in its urban area. The ...

in March 1776. The Invasion of Quebec was also carried out by the Continental Army in 1775.

American Revolution

Declaration of Independence

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, still meeting in Philadelphia, voted unanimously to declare independence as the "

On July 2, 1776, the Second Continental Congress, still meeting in Philadelphia, voted unanimously to declare independence as the "United States of America

The United States of America (U.S.A. or USA), commonly known as the United States (U.S. or US) or America, is a country primarily located in North America. It consists of 50 states, a federal district, five major unincorporated territo ...

". Two days later, on July 4, Congress signed the Declaration of Independence. The Second Continental Congress was not initially formed to declare independence. Support for independence had grown gradually in 1775 and 1776 as Great Britain refused the colonists' demands and hostilities became more pronounced. The political pamphlet ''Common Sense

''Common Sense'' is a 47-page pamphlet written by Thomas Paine in 1775–1776 advocating independence from Great Britain to people in the Thirteen Colonies. Writing in clear and persuasive prose, Paine collected various moral and political argu ...

'' further popularized support for independence. In May 1776, the Continental Congress recommended that the colonies establish their own governments independently of Great Britain.

The drafting of the Declaration was the responsibility of a Committee of Five

''

The Committee of Five of the Second Continental Congress was a group of five members who drafted and presented to the full Congress in Pennsylvania State House what would become the United States Declaration of Independence of July 4, 1776. Th ...

, which included John Adams

John Adams (October 30, 1735 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, attorney, diplomat, writer, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the second president of the United States from 1797 to 1801. Befor ...

, Thomas Jefferson

Thomas Jefferson (April 13, 1743 – July 4, 1826) was an American statesman, diplomat, lawyer, architect, philosopher, and Founding Fathers of the United States, Founding Father who served as the third president of the United States from 18 ...

, Roger Sherman

Roger Sherman (April 19, 1721 – July 23, 1793) was an American statesman, lawyer, and a Founding Father of the United States. He is the only person to sign four of the great state papers of the United States related to the founding: the Cont ...

, Robert Livingston, and Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading inte ...

; it was drafted by Jefferson and revised by the others and the Congress as a whole. It contended that "all men are created equal

The quotation "all men are created equal" is part of the sentence in the U.S. Declaration of Independence

The United States Declaration of Independence, formally The unanimous Declaration of the thirteen States of America, is the pronounc ...

" with "certain unalienable rights, that among these are life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness

"Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness" is a well-known phrase from the United States Declaration of Independence. Scanned image of the Jefferson's "original Rough draught" of the Declaration of Independence, written in June 1776, includin ...

", and that "to secure these rights governments are instituted among men, deriving their just powers from the consent of the governed

In political philosophy, the phrase consent of the governed refers to the idea that a government's legitimacy and moral right to use state power is justified and lawful only when consented to by the people or society over which that political powe ...

", as well as listing the main colonial grievances against the crown. Jefferson expressed that he did not wish to create new arguments, but rather to present those of previous philosophers, such as those of John Locke

John Locke (; 29 August 1632 – 28 October 1704) was an English philosopher and physician, widely regarded as one of the most influential of Age of Enlightenment, Enlightenment thinkers and commonly known as the "father of liberalism ...

.

The signers of the Declaration of Independence were highly educated and wealthy, and they came from the older colonial settlements. They were largely Protestant

Protestantism is a Christian denomination, branch of Christianity that follows the theological tenets of the Reformation, Protestant Reformation, a movement that began seeking to reform the Catholic Church from within in the 16th century agai ...

and of British descent

British people or Britons, also known colloquially as Brits, are the citizens of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland, the British Overseas Territories, and the Crown dependencies.: British nationality law governs mo ...

. In the following century, the signing of the Declaration of Independence would be commemorated as Independence Day

An independence day is an annual event commemorating the anniversary of a nation's independence or statehood, usually after ceasing to be a group or part of another nation or state, or more rarely after the end of a military occupation. Man ...

.

Revolutionary War

Northern Theater (1776–1777)

The task of organizing the Continental Army fell to General Washington, and Congress oversaw military action through war boards. Washington assigned Prussian BaronFriedrich Wilhelm von Steuben

Friedrich Wilhelm August Heinrich Ferdinand von Steuben (born Friedrich Wilhelm Ludolf Gerhard Augustin Louis von Steuben; September 17, 1730 – November 28, 1794), also referred to as Baron von Steuben (), was a Prussian military officer who p ...

to train the army, and the baron's military experience produced a strong military for the United States. To supply the army, Washington pressured Congress for additional supplies, though there was never as much as was necessary.

The New York and New Jersey campaign

The New York and New Jersey campaign in 1776 and the winter months of 1777 was a series of American Revolutionary War battles for control of the Port of New York and New Jersey, Port of New York and the state of New Jersey, fought between Kingdom ...

began in July 1776 as British reinforcements landed in New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

. The British counteroffensive won the Battle of Long Island

The Battle of Long Island, also known as the Battle of Brooklyn and the Battle of Brooklyn Heights, was an action of the American Revolutionary War fought on August 27, 1776, at the western edge of Long Island in present-day Brooklyn, New Yo ...

, and subsequent battles resulted in alternating American and British victories. The Continental Army was routed to New Jersey, and the British army failed to take control of New England. The campaign shifted to Washington's favor after he led a crossing of the Delaware River that led to a victory in the Battle of Trenton

The Battle of Trenton was a small but pivotal American Revolutionary War battle on the morning of December 26, 1776, in Trenton, New Jersey. After General George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American m ...

, followed by another victory in the Battle of Princeton

The Battle of Princeton was a battle of the American Revolutionary War, fought near Princeton, New Jersey on January 3, 1777, and ending in a small victory for the Colonials. General Lord Cornwallis had left 1,400 British troops under the comman ...

, boosting American morale.

In early 1777, a grand British strategic plan, the Saratoga campaign

The Saratoga campaign in 1777 was an attempt by the British high command for North America to gain military control of the strategically important Hudson River valley during the American Revolutionary War. It ended in the surrender of the British ...

, was drafted in London. The plan called for two British armies to converge on Albany, New York

Albany ( ) is the capital of the U.S. state of New York, also the seat and largest city of Albany County. Albany is on the west bank of the Hudson River, about south of its confluence with the Mohawk River, and about north of New York City ...

from the north and south, dividing the colonies in two and separating New England

New England is a region comprising six states in the Northeastern United States: Connecticut, Maine, Massachusetts, New Hampshire, Rhode Island, and Vermont. It is bordered by the state of New York to the west and by the Canadian provinces ...

from the rest. General John Burgoyne

General John Burgoyne (24 February 1722 – 4 August 1792) was a British general, dramatist and politician who sat in the House of Commons from 1761 to 1792. He first saw action during the Seven Years' War when he participated in several batt ...

led British soldiers from Montreal in June 1777, engaging in skirmishes with American forces. American General Horatio Gates

Horatio Lloyd Gates (July 26, 1727April 10, 1806) was a British-born American army officer who served as a general in the Continental Army during the early years of the Revolutionary War. He took credit for the American victory in the Battles ...

was appointed as Northern Army commander. The forces of Burgoyne and Gates fought in the Saratoga campaign, with the British forces surrendering after the Second Battle of Saratoga. The forces of British commander William Howe were supposed to provide reinforcements from the south, but he instead engaged in the Philadelphia campaign

The Philadelphia campaign (1777–1778) was a British effort in the American Revolutionary War to gain control of Philadelphia, which was then the seat of the Second Continental Congress. British General William Howe, after failing to draw ...

, taking the capital city of Philadelphia.

The American victory at Saratoga led the French into a military alliance with the United States through the Treaty of Alliance in 1778. France was soon joined by Spain and the Netherlands, both major naval powers with an interest in undermining British strength. Britain now faced a major European war, and the involvement of the French navy neutralized their previous dominance of the war on the sea. Britain was without allies and faced the prospect of invasion across the English Channel

The English Channel, "The Sleeve"; nrf, la Maunche, "The Sleeve" (Cotentinais) or ( Jèrriais), (Guernésiais), "The Channel"; br, Mor Breizh, "Sea of Brittany"; cy, Môr Udd, "Lord's Sea"; kw, Mor Bretannek, "British Sea"; nl, Het Kana ...

.

Southern Theater (1778–1781)

Except for an attempt to take Charleston in 1776, Great Britain did not attack the southern states of Georgia or South Carolina in the early years of the war. Most fighting in the South had been carried out by theCherokee

The Cherokee (; chr, ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ, translit=Aniyvwiyaʔi or Anigiduwagi, or chr, ᏣᎳᎩ, links=no, translit=Tsalagi) are one of the indigenous peoples of the Southeastern Woodlands of the United States. Prior to the 18th century, t ...

. Following the failure at Saratoga, however, Great Britain moved its focus to the South, and the Capture of Savannah

The Capture of Savannah, or sometimes the First Battle of Savannah (because of the siege of 1779), or the Battle of Brewton Hill,Heitman, pp. 670 and 681 was an American Revolutionary War battle fought on December 29, 1778 pitting local Americ ...

occurred in 1778. The United States had not been prepared for a campaign in the South, and American General Benjamin Lincoln

Benjamin Lincoln (January 24, 1733 ( O.S. January 13, 1733) – May 9, 1810) was an American army officer. He served as a major general in the Continental Army during the American Revolutionary War. Lincoln was involved in three major surrender ...

was appointed to the South to raise a militia. The Siege of Charleston

The siege of Charleston was a major engagement and major British victory in the American Revolutionary War, fought in the environs of Charles Town (today Charleston), the capital of South Carolina, between March 29 and May 12, 1780. The Britis ...

took place in 1780, and the British captured this city as well. North Carolina, South Carolina, and Georgia had higher Loyalist populations than other states, further contributing to British victories in the southern theater. After the Siege of Charleston, British General Lord Cornwallis

Charles Cornwallis, 1st Marquess Cornwallis, (31 December 1738 – 5 October 1805), styled Viscount Brome between 1753 and 1762 and known as the Earl Cornwallis between 1762 and 1792, was a British Army general and official. In the United S ...

took charge of the British forces in the Southern United States. Victory in the Battle of Camden

The Battle of Camden (August 16, 1780), also known as the Battle of Camden Court House, was a major victory for the British in the Southern theater of the American Revolutionary War. On August 16, 1780, British forces under Lieutenant General ...

in 1780 reiterated British control over the South.

Cornwallis advanced his forces into North Carolina, depending on Loyalists to join his forces as he went, but few joined him. General Nathanael Greene

Nathanael Greene (June 19, 1786, sometimes misspelled Nathaniel) was a major general of the Continental Army in the American Revolutionary War. He emerged from the war with a reputation as General George Washington's most talented and dependabl ...

routed the British forces, preventing them from taking North Carolina. Against his instructions to defend the occupied South, Cornwallis moved his forced north to Virginia. Greene's forces moved south and reclaimed Georgia and South Carolina. Cornwallis positioned his forces in Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a census-designated place (CDP) in York County, Virginia. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while York Cou ...

in hope of defeating the forces of the French General Lafayette

Lafayette or La Fayette may refer to:

People

* Lafayette (name), a list of people with the surname Lafayette or La Fayette or the given name Lafayette

* House of La Fayette, a French noble family

** Gilbert du Motier, Marquis de Lafayette (1757� ...

. The French navy prevented the British navy from providing assistance in the Battle of the Chesapeake

The Battle of the Chesapeake, also known as the Battle of the Virginia Capes or simply the Battle of the Capes, was a crucial naval battle in the American Revolutionary War that took place near the mouth of the Chesapeake Bay on 5 September 17 ...

, and Washington and Lafayette's forces laid siege to Yorktown. Cornwallis surrendered on October 19, 1781, effectively ending the American Revolutionary War. King George III and Prime Minister Lord North

Frederick North, 2nd Earl of Guilford (13 April 17325 August 1792), better known by his courtesy title Lord North, which he used from 1752 to 1790, was 12th Prime Minister of Great Britain from 1770 to 1782. He led Great Britain through most o ...

wished to mount another campaign, but Parliament

In modern politics, and history, a parliament is a legislative body of government. Generally, a modern parliament has three functions: Representation (politics), representing the Election#Suffrage, electorate, making laws, and overseeing ...

overruled them, forbidding any further conflict.

Treaty of Paris

King George III formally acknowledged American independence and ordered the end of hostilities on December 5, 1782. Peace negotiations took place inParis

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. S ...

, with John Adams, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay

John Jay (December 12, 1745 – May 17, 1829) was an American statesman, patriot, diplomat, abolitionist, signatory of the Treaty of Paris, and a Founding Father of the United States. He served as the second governor of New York and the first ...

representing the United States. Negotiations concluded with the Treaty of Paris Treaty of Paris may refer to one of many treaties signed in Paris, France:

Treaties

1200s and 1300s

* Treaty of Paris (1229), which ended the Albigensian Crusade

* Treaty of Paris (1259), between Henry III of England and Louis IX of France

* Trea ...

, which legally recognized the United States as an independent country. Great Britain agreed to give up its territorial claims in the states and to their west, though the boundary with British Canada remained unsettled. Some elements of the treaty were controversial among Americans, including those that recognized the monetary debts owed to Loyalists and those that critics felt challenged the status of each state government as a sovereign entity.

On November 25, 1783, Washington led a procession through New York City on horseback as the final British soldiers boarded their boats to leave the harbor. Victory celebrations were held in the city, and the day would be remembered as Evacuation Day. On December 23, 1783, Washington resigned his commission as commander-in-chief of the Continental Army. The Treaty of Paris was ratified by Congress on January 14, 1784.

Confederation period

Articles of Confederation and Perpetual Union

The Articles of Confederation were proposed by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, and they were ratified on March 1, 1781. It replaced the administrative boards and appellate courts that Congress had created during the early stages of the Revolutionary War. While the Articles of Confederation granted certain powers to the

The Articles of Confederation were proposed by the Continental Congress on November 15, 1777, and they were ratified on March 1, 1781. It replaced the administrative boards and appellate courts that Congress had created during the early stages of the Revolutionary War. While the Articles of Confederation granted certain powers to the Congress of the Confederation

The Congress of the Confederation, or the Confederation Congress, formally referred to as the United States in Congress Assembled, was the governing body of the United States of America during the Confederation period, March 1, 1781 – Mar ...

, they also imposed restrictions that made governance difficult. These restrictions were by design, as many Americans feared that a strong central government would be too similar to the British monarchy. The powers of the central government were limited primarily to war, diplomacy, and resolving interstate disputes. It lacked powers to pass economic legislation, causing economic decline as it proved unable to pay its debts. Acts of Congress required high majorities to be passed, and amendments to the Articles required unanimous approval by the states.

Most governing was carried out by state governments during the Confederation Period. Though Pennsylvania was the only state to use official political parties, informal partisanship

A partisan is a committed member of a political party or army. In multi-party systems, the term is used for persons who strongly support their party's policies and are reluctant to compromise with political opponents. A political partisan is no ...

developed across the new nation in the 1780s. Divisions emerged over how powerful the central government should be, how debts should be managed, and how Western settlement should be carried out. The political and economic troubles caused civil conflict within the states. Mutinies occurred in Pennsylvania

Pennsylvania (; ( Pennsylvania Dutch: )), officially the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, is a state spanning the Mid-Atlantic, Northeastern, Appalachian, and Great Lakes regions of the United States. It borders Delaware to its southeast, ...

and New Jersey

New Jersey is a state in the Mid-Atlantic and Northeastern regions of the United States. It is bordered on the north and east by the state of New York; on the east, southeast, and south by the Atlantic Ocean; on the west by the Delaware ...

in January 1781, soldiers marched on the capital in June 1783, and a coup against General Washington was considered among military officers in Newburgh. The unrest culminated in Shays' Rebellion

Shays Rebellion was an armed uprising in Western Massachusetts and Worcester in response to a debt crisis among the citizenry and in opposition to the state government's increased efforts to collect taxes both on individuals and their trades. The ...

in the winter of 1786–1787, in which protests against the handling of debts in Massachusetts led to an armed uprising. The states declined to fund a military force, and Massachusetts was forced to fund its own state force.

Foreign affairs

Congress oversaw foreign policy, but the states had the final say in their own foreign relations, with each state ratifying treaties individually. Relations with Great Britain were still troubled after the war. Many states did not comply with the terms of the Treaty of Paris regarding the treatment of British nationals, and the British Army maintained a presence in the western territories. Britain also hurt American trade through restrictions on American products to promote Canadian growth. TheShelburne ministry

This is a list of the principal holders of government office during the premiership of the Earl of Shelburne between July 1782 and April 1783.

Upon the fall of the North ministry in March 1782, Whig Lord Rockingham became Prime Minister for a sec ...

had been lenient in the negotiation of the Treaty of Paris, but this proved controversial, prompting a change in government that resulted in much colder relations with the United States.

As economic conditions worsened, Congress failed to repay its debts to the countries that provided military support during the war: France, Spain, and the Netherlands. Relations with Spain were further strained by the Spanish government's closure of the Mississippi River

The Mississippi River is the second-longest river and chief river of the second-largest drainage system in North America, second only to the Hudson Bay drainage system. From its traditional source of Lake Itasca in northern Minnesota, it f ...

, which hindered American transport and trade. Despite a strong alliance during the revolution, France paid little attention to the United States during the Confederacy period. The United States also made trade agreements with the Netherlands, Sweden, and Prussia in the 1780s, but these made up a relatively small portion of American trade compared to Great Britain. In the Mediterranean Sea

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the ea ...

, American ships faced the North African Barbary pirates

The Barbary pirates, or Barbary corsairs or Ottoman corsairs, were Muslim pirates and privateers who operated from North Africa, based primarily in the ports of Salé, Rabat, Algiers, Tunis and Tripoli, Libya, Tripoli. This area was known i ...

. As Congress had few resources to address the issue, little was done during the Confederation period to take action against the pirates. A peace negotiation was made with Morocco, but Algiers, Tripoli, and Tunis continued to allow the capture of American ships.

Constitutional Convention

Economic conflict grew between the states as the Confederation period went on, and Congress had no power to prevent it. By 1786, many of the most prominent Americans in government were expressing concerns that the government under the Articles of Confederation was not sufficient. It lacked both the economic and military security that had previously been provided by Great Britain. The Annapolis Convention was held in 1786 to address trade issues, but it saw meager attendance with most states failing to send a delegate. The delegates from New Jersey had been authorized wide latitude by the state, and this was used to submit a proposal for a convention to reform the government entirely. In February 1787, Congress voted to hold the convention the following May, indicating a broad loss in confidence of the governmental system under the Articles of Confederation.

While there was not a clear objective before the convention, some delegates wished to establish a new central government that would have more power than Congress did under the Articles of Confederation.

Economic conflict grew between the states as the Confederation period went on, and Congress had no power to prevent it. By 1786, many of the most prominent Americans in government were expressing concerns that the government under the Articles of Confederation was not sufficient. It lacked both the economic and military security that had previously been provided by Great Britain. The Annapolis Convention was held in 1786 to address trade issues, but it saw meager attendance with most states failing to send a delegate. The delegates from New Jersey had been authorized wide latitude by the state, and this was used to submit a proposal for a convention to reform the government entirely. In February 1787, Congress voted to hold the convention the following May, indicating a broad loss in confidence of the governmental system under the Articles of Confederation.

While there was not a clear objective before the convention, some delegates wished to establish a new central government that would have more power than Congress did under the Articles of Confederation. James Madison

James Madison Jr. (March 16, 1751June 28, 1836) was an American statesman, diplomat, and Founding Father. He served as the fourth president of the United States from 1809 to 1817. Madison is hailed as the "Father of the Constitution" for hi ...

became the leader of these delegates, developing the Virginia Plan

The ''Virginia Plan'' (also known as the Randolph Plan, after its sponsor, or the Large-State Plan) was a proposal to the United States Constitutional Convention for the creation of a supreme national government with three branches and a bicam ...

that would form the basis of the Constitution of the United States

The Constitution of the United States is the supreme law of the United States of America. It superseded the Articles of Confederation, the nation's first constitution, in 1789. Originally comprising seven articles, it delineates the natio ...

. The convention began on May 25, 1787, after a sufficient number of delegates had arrived in Philadelphia. The main issue at contention was the extent of power that would be transferred from the states to the federal government; many state delegations, particularly that of Delaware, resisted centralization for fear that it would be dominated by the larger states. Madison's Virginia Plan competed with the New Jersey Plan

The New Jersey Plan (also known as the Small State Plan or the Paterson Plan) was a proposal for the structure of the United States Government presented during the Constitutional Convention of 1787. Principally authored by William Paterson of Ne ...

of William Paterson, which opposed proportional representation in favor of equal representation. The dispute was resolved with the Connecticut Compromise

The Connecticut Compromise (also known as the Great Compromise of 1787 or Sherman Compromise) was an agreement reached during the Constitutional Convention of 1787 that in part defined the legislative structure and representation each state woul ...

, which created a bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single grou ...

legislature. The issue of slavery was also a concern, particularly in regard to whether slaves should be counted as citizens.

The final draft of the Constitution was delivered by Gouverneur Morris

Gouverneur Morris ( ; January 31, 1752 – November 6, 1816) was an American statesman, a Founding Father of the United States, and a signatory to the Articles of Confederation and the United States Constitution. He wrote the Preamble to the U ...

on September 12, 1787. Written to correct the weaknesses of the Articles of Confederation, the Constitution established the procedures and powers relating to Congress, the presidency, the courts, and how these offices related to the states. It also allowed for future amendments, acknowledged the debts incurred under the Articles of Confederation, and set the requirements for ratification. The delegates signed the Constitution on September 17 and sent it to Congress, where it was approved and sent to the states for ratification.

Campaign for ratification

Those who advocated the Constitution took the name

Those who advocated the Constitution took the name Federalists

The term ''federalist'' describes several political beliefs around the world. It may also refer to the concept of parties, whose members or supporters called themselves ''Federalists''.

History Europe federation

In Europe, proponents of de ...

and quickly gained supporters throughout the nation. The most influential Federalists were Alexander Hamilton

Alexander Hamilton (January 11, 1755 or 1757July 12, 1804) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first United States secretary of the treasury from 1789 to 1795.

Born out of wedlock in Charlest ...

and James Madison, the anonymous authors of ''The Federalist Papers

''The Federalist Papers'' is a collection of 85 articles and essays written by Alexander Hamilton, James Madison, and John Jay under the collective pseudonym "Publius" to promote the ratification of the Constitution of the United States. The co ...

'', a series of 85 essays published in New York newspapers, written under the pen name "Publius" to sway the closely divided New York legislature. The papers have become seminal documents for the United States and have often been cited by jurists. Those who opposed the new Constitution became known as the Anti-Federalists

Anti-Federalism was a late-18th century political movement that opposed the creation of a stronger U.S. federal government and which later opposed the ratification of the 1787 Constitution. The previous constitution, called the Articles of Con ...

. They were generally local rather than cosmopolitan in perspective, oriented to plantations and farms rather than commerce or finance, and wanted strong state governments and a weak national government.

Each state held a convention to vote on ratification of the Constitution. Supporters of ratification ensured that states more likely to accept the Constitution were the first to hold conventions, fearing that early rejections may dissuade other states from ratifying. Smaller states were supportive of the Constitution, as a centralized government offered a check on the power of larger states. Delaware and New Jersey ratified in 1787, and Georgia ratified on January 2, 1788, all by unanimous votes. Pennsylvania, Connecticut, Maryland, and South Carolina all ratified by large majorities over the winter and spring of 1788. It was more controversial in other states, with Massachusetts only ratifying by a narrow vote of 187–168. New Hampshire provided the final ratification that was necessary for the Constitution to go into effect on June 21, 1788. Ratification was more controversial in the larger states of New York, Virginia, and Massachusetts. Promises of a Bill of Rights from Madison secured ratification in Virginia, while in New York, the Clintons, who controlled New York politics, found themselves outmaneuvered as Hamilton secured ratification by a 30–27 vote. North Carolina and Rhode Island were the last of the 13 colonies to ratify, doing so after the new government had begun operation.

The United States Electoral College

The United States Electoral College is the group of presidential electors required by the Constitution to form every four years for the sole purpose of appointing the president and vice president. Each state and the District of Columbia appo ...

met on February 4, 1789 to unanimously vote for George Washington in the first presidential election. The 1st United States Congress

The 1st United States Congress, comprising the United States Senate and the United States House of Representatives, met from March 4, 1789, to March 4, 1791, during the first two years of George Washington's presidency, first at Federal Hall in ...

read the results on April 6, and Washington was inaugurated

In government and politics, inauguration is the process of swearing a person into office and thus making that person the incumbent. Such an inauguration commonly occurs through a formal ceremony or special event, which may also include an inaugu ...

at Federal Hall

Federal Hall is a historic building at 26 Wall Street in the Financial District of Manhattan in New York City. The current Greek Revival–style building, completed in 1842 as the Custom House, is operated by the National Park Service as a nati ...

on April 30.

Westward expansion

Settlement of

Settlement of Trans-Appalachia

The area in United States west of the Appalachian Mountains and extending vaguely to the Mississippi River, spanning the lower Great Lakes to the upper south, is a region known as trans-Appalachia, particularly when referring to frontier times. It ...

grew during the Revolutionary War, increasing from a few thousand to 25,000 settlers. Westward expansion stirred enthusiasm even in those who did not move west, and many leading Americans, including Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and John Jay, purchased lands in the west. Land speculators

In finance, speculation is the purchase of an asset (a commodity, goods, or real estate) with the hope that it will become more valuable shortly. (It can also refer to short sales in which the speculator hopes for a decline in value.)

Many s ...

founded groups like the Ohio Company

The Ohio Company, formally known as the Ohio Company of Virginia, was a land speculation company organized for the settlement by Virginians of the Ohio Country (approximately the present U.S. state of Ohio) and to trade with the Native Americ ...

, which acquired title to vast tracts of land in the west and often came into conflict with settlers.

From 1780 to 1784, Congress held negotiations with Virginia to cede its western territory. An agreement took effect on March 1, 1784, creating the first national territory that was not part of any state. Congress created a territorial government and set requirements for statehood with the Land Ordinance of 1784

The Ordinance of 1784 (enacted April 23, 1784) called for the land in the recently created United States which was located west of the Appalachian Mountains, north of the Ohio River and east of the Mississippi River to be divided into separate s ...

and the Land Ordinance of 1785 The Land Ordinance of 1785 was adopted by the United States Congress of the Confederation on May 20, 1785. It set up a standardized system whereby settlers could purchase title to farmland in the undeveloped west. Congress at the time did not have ...

. In 1787, Congress passed the Northwest Ordinance

The Northwest Ordinance (formally An Ordinance for the Government of the Territory of the United States, North-West of the River Ohio and also known as the Ordinance of 1787), enacted July 13, 1787, was an organic act of the Congress of the Co ...

, which granted Congress greater control of the region by establishing the Northwest Territory

The Northwest Territory, also known as the Old Northwest and formally known as the Territory Northwest of the River Ohio, was formed from unorganized western territory of the United States after the American Revolutionary War. Established in 1 ...

. Under the new arrangement, many of the former elected officials of the territory were instead appointed by Congress. In order to attract Northern settlers, Congress outlawed slavery in the Northwest Territory, though it also passed a fugitive slave law to appease the Southern states. The Old Southwest

Old or OLD may refer to:

Places

* Old, Baranya, Hungary

* Old, Northamptonshire, England

*Old Street station, a railway and tube station in London (station code OLD)

*OLD, IATA code for Old Town Municipal Airport and Seaplane Base, Old Town, M ...

remained under the control of the southern states, and each state claimed to extend west to the Mississippi River. In 1784, settlers in western North Carolina sought statehood as the State of Franklin

The State of Franklin (also the Free Republic of Franklin or the State of Frankland)Landrum, refers to the proposed state as "the proposed republic of Franklin; while Wheeler has it as ''Frankland''." In ''That's Not in My American History Boo ...

, but their efforts were denied by Congress, which did not want to set a precedent regarding the secession of states.

During the Revolutionary War, Great Britain had aligned with many of the Native American tribes in its claimed territories to the west of the colonies. This was an escalation of the skirmishes that made up the American Indian Wars

The American Indian Wars, also known as the American Frontier Wars, and the Indian Wars, were fought by European governments and colonists in North America, and later by the United States and Canadian governments and American and Canadian settle ...

that had been prompted by land encroachment by colonists and raids by Native American tribes, such as the Shawnee

The Shawnee are an Algonquian-speaking indigenous people of the Northeastern Woodlands. In the 17th century they lived in Pennsylvania, and in the 18th century they were in Pennsylvania, Ohio, Indiana and Illinois, with some bands in Kentucky a ...

tribes. Pioneers responded to Native American attacks against colonial civilians by in turn attacking Native American civilians. The British continued to supply arms to Native Americans after the signing of the Treaty of Paris. Between 1783 and 1787, hundreds of settlers died in low-level conflicts with Native Americans, and these conflicts discouraged further settlement. By the end of the decade, the frontier was engulfed in the Northwest Indian War

The Northwest Indian War (1786–1795), also known by other names, was an armed conflict for control of the Northwest Territory fought between the United States and a united group of Native American nations known today as the Northwestern ...

against the Northwestern Confederacy

The Northwestern Confederacy, or Northwestern Indian Confederacy, was a loose confederacy of Native Americans in the Great Lakes region of the United States created after the American Revolutionary War. Formally, the confederacy referred to it ...

. These Native Americans sought the creation of an independent Indian barrier state

The Indian barrier state or buffer state was a British proposal to establish a Native American state in the portion of the Great Lakes region of North America. It was never created. The idea was to create it west of the Appalachian Mountains, b ...

with the support and under protection of the British, posing a major foreign policy challenge to the United States. As Congress provided little military support against the Native Americans, most of the fighting was done by the settlers. This war would continue until the signing of the Treaty of Greenville

The Treaty of Greenville, formally titled Treaty with the Wyandots, etc., was a 1795 treaty between the United States and indigenous nations of the Northwest Territory (now Midwestern United States), including the Wyandot and Delaware peoples, ...

in 1795 that defined the boundary between the United States and the Native American tribes.

Economy

The American Revolution had large scale effects on the economies of the Thirteen Colonies. The Continental Congress did not have the power to levy taxes, so it depended on the newly formed state governments to raise funds, and they were forced to raise taxes to cover war expenditures. It also caused a

The American Revolution had large scale effects on the economies of the Thirteen Colonies. The Continental Congress did not have the power to levy taxes, so it depended on the newly formed state governments to raise funds, and they were forced to raise taxes to cover war expenditures. It also caused a labor shortage

In economics, a shortage or excess demand is a situation in which the demand for a product or service exceeds its supply in a market. It is the opposite of an excess supply ( surplus).

Definitions

In a perfect market (one that matches a sim ...

as workers enlisted in the Patriot and Loyalist militaries, ending a decades-long trend of industrial expansion in the Mid-Atlantic. The workforce consisted of both free laborers and slave labor

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

, while indentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

had largely fallen out of practice by the time of the American Revolution. Economic growth was further slowed by a reduction in immigration because of the war. The Bank of North America

The Bank of North America was the first chartered bank in the United States, and served as the country's first ''de facto'' central bank. Chartered by the Congress of the Confederation on May 26, 1781, and opened in Philadelphia on January 7, 17 ...

was established as the country's first bank in 1781.

The Continental Congress created its own Continental currency

Early American currency went through several stages of development during the colonial and post-Revolutionary history of the United States. John Hull was authorized by the Massachusetts legislature to make the earliest coinage of the colony (the ...

banknotes to increase funding, but this currency quickly depreciated in value and did not survive to the end of the war. The lack of a centralized currency and economic policy was a major factor in the decision to hold the Constitutional Convention. The war and the inflation caused shortages for both the military and for civilians. It was common during these shortages for civilians to form crowds and ransack stores that did not offer what they considered to be fair prices. Early supporters of revolution also supported corporatism

Corporatism is a collectivist political ideology which advocates the organization of society by corporate groups, such as agricultural, labour, military, business, scientific, or guild associations, on the basis of their common interests. The ...

and price controls

Price controls are restrictions set in place and enforced by governments, on the prices that can be charged for goods and services in a market. The intent behind implementing such controls can stem from the desire to maintain affordability of good ...

, but most political and economic thinkers rejected these concepts, and support grew for a democratic free market

In economics, a free market is an economic system in which the prices of goods and services are determined by supply and demand expressed by sellers and buyers. Such markets, as modeled, operate without the intervention of government or any o ...

system with taxation.

The economy of the early United States was heavily agricultural, but it also involved other forms of resource extraction, such as lumber

Lumber is wood that has been processed into dimensional lumber, including beams and planks or boards, a stage in the process of wood production. Lumber is mainly used for construction framing, as well as finishing (floors, wall panels, wi ...

, fishing

Fishing is the activity of trying to catch fish. Fish are often caught as wildlife from the natural environment, but may also be caught from stocked bodies of water such as ponds, canals, park wetlands and reservoirs. Fishing techniques inclu ...

, and fur

Fur is a thick growth of hair that covers the skin of mammals. It consists of a combination of oily guard hair on top and thick underfur beneath. The guard hair keeps moisture from reaching the skin; the underfur acts as an insulating blanket t ...

. Manufacturing was limited, though shipbuilding

Shipbuilding is the construction of ships and other floating vessels. It normally takes place in a specialized facility known as a shipyard. Shipbuilders, also called shipwrights, follow a specialized occupation that traces its roots to befor ...

was a major industry. The revolution required American merchants to rebuild connections with global markets, as trade had previously been facilitated under the flag of Great Britain. The high tariffs that were common at the time limited profitability, but high demand for American goods allowed the United States to make up for the economic turmoil of the revolution. When the war ended, the Treaty of Paris allowed British creditors to call in debts from the American market, triggering a depression. The government was also in debt to France, the Netherlands, and Spain. Many states raised taxes after the war to cover the expenses that it brought, prompting unrest, including that of Shays' Rebellion.

Due to the close relation of American and British commerce, many traders renegotiated with British merchants after the war, and they facilitated American trade as they did under colonial rule. Economic policies of individual states made domestic trade more difficult, as state governments often discriminated against merchants from other states. A national deficit occurred in 1786, and it continued to increase through the Confederation period. By 1787, Congress was unable to protect manufacturing and shipping. State legislatures were unable or unwilling to resist attacks upon private contracts and public credit. Land speculators expected no rise in values when the government could not defend its borders nor protect its frontier population.

Culture and media

A distinct American culture separate from Britain had already developed by the 1750s. A plainness in fashion and speech was common, originating from

A distinct American culture separate from Britain had already developed by the 1750s. A plainness in fashion and speech was common, originating from Puritan

The Puritans were English Protestants in the 16th and 17th centuries who sought to purify the Church of England of Catholic Church, Roman Catholic practices, maintaining that the Church of England had not been fully reformed and should become m ...

standards of the colonial era and reasserted by the revolution. The United States in the 18th century saw a proliferation of newspapers and magazine, many of which were in print only briefly. Political essays such as ''The American Crisis

''The American Crisis'', or simply ''The Crisis'', is a pamphlet series by eighteenth-century Enlightenment philosopher and author Thomas Paine, originally published from 1776 to 1783 during the American Revolution. Thirteen numbered pamphlets w ...

'', ''Common Sense'', and ''The Federalist Papers'' were influential in shaping the early United States. Full-length books also addressed political concepts regarding the revolution, including ''Letters from an American Farmer

''Letters from an American Farmer'' is a series of letters written by French American writer J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur, first published in 1782. The considerably longer title under which it was originally published is ''Letters from an ...

'' by J. Hector St. John de Crèvecœur and ''Notes on the State of Virginia

''Notes on the State of Virginia'' (1785) is a book written by the American statesman, philosopher, and planter Thomas Jefferson. He completed the first version in 1781 and updated and enlarged the book in 1782 and 1783. It originated in Jeffers ...

'' by Thomas Jefferson. Social and political ideas were often expressed through poetry. Poets such as John Trumbull

John Trumbull (June 6, 1756November 10, 1843) was an American artist of the early independence period, notable for his historical paintings of the American Revolutionary War, of which he was a veteran. He has been called the "Painter of the Rev ...

, Philip Freneau

Philip Morin Freneau (January 2, 1752 – December 18, 1832) was an American poet, nationalist, polemicist, sea captain and early American newspaper editor, sometimes called the "Poet of the American Revolution". Through his newspaper, th ...

and Hugh Henry Brackenridge

Hugh Henry Brackenridge (1748June 25, 1816) was an American writer, lawyer, judge, and justice of the Supreme Court of Pennsylvania.

A frontier citizen in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, United States, he founded both the Pittsburgh Academy, now the ...

wrote of nationalist ideas about an independent United States. ''The Conquest of Canaan'' by Timothy Dwight is credited as the first epic poem

An epic poem, or simply an epic, is a lengthy narrative poem typically about the extraordinary deeds of extraordinary characters who, in dealings with gods or other superhuman forces, gave shape to the mortal universe for their descendants.

...

of the United States. ''The Anarchiad

''The Anarchiad'' (1786–87) is an American mock-epic poem that reflected Federalist concerns during the formation of the United States. ''The Anarchiad, or American Antiquities: A Poem on the Restoration of Chaos and Substantial Night'' was ...

'' was a prominent satire of the early United States. The first American novel, ''The Power of Sympathy

''The Power of Sympathy: or, The Triumph of Nature'' (1789) is an 18th-century American sentimental novel written in epistolary form by William Hill Brown and is widely considered to be the first American novel. ''The Power of Sympathy'' was Bro ...

'', was published by William Hill Brown

William Hill Brown (November 1765 – September 2, 1793) was an American novelist, the author of what is usually considered the first American novel, ''The Power of Sympathy'' (1789), and "Harriot, or the Domestic Reconciliation", as well as th ...

in 1789.

Drama and theater were controversial in the early United States. Plays had been condemned by Puritans in the colonial era, and the Continental Congress issued a formal condemnation of plays in 1774. Plays that were performed during the revolutionary era were typically European. The most prominent American dramatist during the revolutionary era was Mercy Otis Warren

Mercy Otis Warren (September 14, eptember 25, New Style1728 – October 19, 1814) was an American activist poet, playwright, and pamphleteer during the American Revolution. During the years before the Revolution, she had published poems and pla ...

, whose plays included ''The Adulateur

''The'' () is a grammatical Article (grammar), article in English language, English, denoting persons or things already mentioned, under discussion, implied or otherwise presumed familiar to listeners, readers, or speakers. It is the definite ...

'', ''The Group'', and ''The Blockheads''. Hugh Henry Brackenridge wrote two historical plays that portrayed the Revolutionary War. John Leacock wrote ''The Fall of British Tyranny'', the first play to feature George Washington as a character. Innovations in drama declined after the Revolutionary War, in part due to the political and economic turmoil of the 1780s. William Dunlap

William Dunlap (February 19, 1766 – September 28, 1839) was a pioneer of American theater. He was a producer, playwright, and actor, as well as a historian. He managed two of New York City's earliest and most prominent theaters, the John Str ...

began his prolific career as a playwright with ''The Father'' in 1789.

Visual art was influenced by the literature of European aestheticians, including Charles Alphonse du Fresnoy, Roger de Piles

Roger de Piles (7 October 1635 – 5 April 1709) was a French painter, engraver, art critic and diplomat.

Life

Born in Clamecy, Roger de Piles studied philosophy and theology, and devoted himself to painting.

In 1662 he became tutor to Miche ...

, Jonathan Richardson

Jonathan Richardson (12 January 1667 – 28 May 1745), sometimes called "the Elder" to distinguish him from his son (Jonathan Richardson the Younger), was an English artist, collector of drawings and writer on art, working almost entirely as a ...

, and Johann Joachim Winckelmann

Johann Joachim Winckelmann (; ; 9 December 17178 June 1768) was a German art historian and archaeologist. He was a pioneering Hellenist who first articulated the differences between Greek, Greco-Roman and Roman art. "The prophet and founding he ...

. Many American artists traveled abroad to learn art, particularly to London to learn under Benjamin West

Benjamin West, (October 10, 1738 – March 11, 1820) was a British-American artist who painted famous historical scenes such as '' The Death of Nelson'', ''The Death of General Wolfe'', the '' Treaty of Paris'', and '' Benjamin Franklin Drawin ...

. John Trumbull

John Trumbull (June 6, 1756November 10, 1843) was an American artist of the early independence period, notable for his historical paintings of the American Revolutionary War, of which he was a veteran. He has been called the "Painter of the Rev ...

and Charles Willson Peale

Charles Willson Peale (April 15, 1741 – February 22, 1827) was an American Painting, painter, soldier, scientist, inventor, politician and naturalist. He is best remembered for his portrait paintings of leading figures of the American Revolu ...

were prominent painters in the first years of the United States; as supporters of republicanism, they are both known for their respective portraits of George Washington.

Science and education

Historians categorize the time of the American Revolution as part of a broader

Historians categorize the time of the American Revolution as part of a broader American Enlightenment

The American Enlightenment was a period of intellectual ferment in the thirteen American colonies in the 18th to 19th century, which led to the American Revolution, and the creation of the United States of America. The American Enlightenment was ...

, in which the ideas of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

began to influence American science and philosophy. This included a shift away from religious groundings in philosophy. Benjamin Franklin and Thomas Jefferson were prolific philosophic writers in this regard. '' Reason: the Only Oracle of Man'' by Ethan Allen

Ethan Allen ( – February 12, 1789) was an American farmer, businessman, land speculator, philosopher, writer, lay theologian, American Revolutionary War patriot, and politician. He is best known as one of the founders of Vermont and for ...

was an early challenge to the religious rejection of rationalism

In philosophy, rationalism is the epistemological view that "regards reason as the chief source and test of knowledge" or "any view appealing to reason as a source of knowledge or justification".Lacey, A.R. (1996), ''A Dictionary of Philosophy' ...

in the United States in 1784. Massachusetts formed a medical society in 1781, following the precedent set by New Jersey in 1766.

The scientific community of the early United States was centered in Philadelphia, including the American Philosophical Society

The American Philosophical Society (APS), founded in 1743 in Philadelphia, is a scholarly organization that promotes knowledge in the sciences and humanities through research, professional meetings, publications, library resources, and communit ...

. Astronomy

Astronomy () is a natural science that studies astronomical object, celestial objects and phenomena. It uses mathematics, physics, and chemistry in order to explain their origin and chronology of the Universe, evolution. Objects of interest ...

and taxonomy

Taxonomy is the practice and science of categorization or classification.

A taxonomy (or taxonomical classification) is a scheme of classification, especially a hierarchical classification, in which things are organized into groups or types. ...

were two of the most prominent scientific fields at the time, and physicians of the revolutionary era often had a scientific background beyond medicine. Benjamin Franklin developed the study of electricity

Electricity is the set of physical phenomena associated with the presence and motion of matter that has a property of electric charge. Electricity is related to magnetism, both being part of the phenomenon of electromagnetism, as described ...

in the United States and discovered many of its properties. Many prominent scientists were immigrants from other countries, particularly Great Britain, which had a much larger scientific community.

The colonial colleges

The colonial colleges are nine institutions of higher education chartered in the Thirteen Colonies before the United States of America became a sovereign nation after the American Revolution. These nine have long been considered together, notably ...

already existed by the time of the American Revolution. These colleges were all male, and they were based on the ideas of education associated with the Enlightenment. State universities

A state university system in the United States is a group of public universities supported by an individual state, territory or federal district. These systems constitute the majority of public-funded universities in the country.

State univers ...

began to form after the end of the Revolutionary War, starting with the University of Georgia

, mottoeng = "To teach, to serve, and to inquire into the nature of things.""To serve" was later added to the motto without changing the seal; the Latin motto directly translates as "To teach and to inquire into the nature of things."

, establ ...

in 1785. African Americans and Native Americans were only rarely admitted to universities, though African American men in northern states sometimes formed literary societies.

Demographics

The population of the Thirteen Colonies was 2.5 million in 1776. The first national census was taken in 1790, shortly after the end of the Confederation period. It found that the United States had a population of 3,929,214 residents with an average of 4.5 people per square mile. There were five cities with a population over 10,000 residents. The largest city was New York City with 33,131 residents, followed by Philadelphia, Boston, Charleston, andBaltimore

Baltimore ( , locally: or ) is the List of municipalities in Maryland, most populous city in the U.S. state of Maryland, fourth most populous city in the Mid-Atlantic (United States), Mid-Atlantic, and List of United States cities by popula ...

.

Religion