History Of Slavery In New York (state) on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The enslavement of African people in the United States continued in New York as part of the

The enslavement of African people in the United States continued in New York as part of the

The enslavement of African people in the United States continued in New York as part of the

The enslavement of African people in the United States continued in New York as part of the Dutch slave trade

The History of Dutch slavery involves slavery in the Netherlands itself, as well as the establishment of slavery outside the Netherlands in which it played a role. The Netherlands banned the slave trade in 1814 after being compelled by Brit ...

. The Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company ( nl, Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, ''WIC'' or ''GWC''; ; en, Chartered West India Company) was a chartered company of Dutch merchants as well as foreign investors. Among its founders was Willem Usselincx ...

imported eleven African slaves to New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

in 1626, with the first slave auction held in New Amsterdam in 1655. With the second-highest proportion of any city in the colonies (after Charleston, South Carolina

Charleston is the largest city in the U.S. state of South Carolina, the county seat of Charleston County, and the principal city in the Charleston–North Charleston metropolitan area. The city lies just south of the geographical midpoint o ...

), more than 42% of New York City households held slaves by 1703, often as domestic servants and laborers. Others worked as artisans or in shipping and various trades in the city. Slaves were also used in farming on Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

and in the Hudson Valley

The Hudson Valley (also known as the Hudson River Valley) comprises the valley of the Hudson River and its adjacent communities in the U.S. state of New York. The region stretches from the Capital District including Albany and Troy south to ...

, as well as the Mohawk Valley region

The Mohawk Valley region of the U.S. state of New York is the area surrounding the Mohawk River, sandwiched between the Adirondack Mountains and Catskill Mountains, northwest of the Capital District. As of the 2010 United States Census, th ...

.

During the American Revolutionary War

The American Revolutionary War (April 19, 1775 – September 3, 1783), also known as the Revolutionary War or American War of Independence, was a major war of the American Revolution. Widely considered as the war that secured the independence of t ...

, the British troops occupied New York City in 1776. The Philipsburg Proclamation

The Philipsburg Proclamation is a historical document issued by British Army General Sir Henry Clinton on 30 June 1779, intended to encourage slaves to run away and enlist in the Royal Forces.

Text

General Clinton issued the following proclamat ...

promised freedom to slaves who left rebel masters, and thousands moved to the city for refuge with the British. By 1780, 10,000 black people lived in New York. Many were slaves who had escaped from their slaveholders in both Northern and Southern colonies. After the war, the British evacuated about 3,000 slaves from New York, taking most of them to resettle as free people in Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

, where they are known as Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the C ...

s.

Of the Northern states, New York was next to last in abolishing slavery. (In New Jersey, mandatory, unpaid "apprenticeships" did not end until the Thirteenth Amendment ended slavery, in 1865.)

After the American Revolution, the New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785 to work for the abolition of slavery and to aid free blacks. The state passed a 1799 law for gradual abolition, a law which freed no living slave. After that date, children born to slave mothers were required to work for the mother's master as indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

until age 28 (men) and 25 (women). The last slaves were freed of this obligation on July 4, 1827 (28 years after 1799). African Americans celebrated with a parade.

Upstate New York

Upstate New York is a geographic region consisting of the area of New York (state), New York State that lies north and northwest of the New York metropolitan area, New York City metropolitan area. Although the precise boundary is debated, Upsta ...

, in contrast with New York City, was an anti-slavery leader. The first meeting of the New York State Anti-Slavery Society

New is an adjective referring to something recently made, discovered, or created.

New or NEW may refer to:

Music

* New, singer of K-pop group The Boyz

Albums and EPs

* ''New'' (album), by Paul McCartney, 2013

* ''New'' (EP), by Regurgitator, ...

opened in Utica, although local hostility caused the meeting to be moved to the home of Gerrit Smith, in Peterboro

Peterboro, located approximately southeast of Syracuse, New York, is a historic hamlet and currently the administrative center for the Town of Smithfield, Madison County, New York, United States. Peterboro has a Post Office, ZIP code 13134.

...

. The Oneida Institute

The Oneida Institute was a short-lived (1827–1843) but highly influential school that was a national leader in the emerging abolitionist movement. It was the most radical school in the country, the first at which black men were just as welcome ...

, near Utica, briefly the center of American abolitionism, accepted both black and white male enrolees on an equal basis. New-York Central College, near Cortland, was an abolitionist institution of higher learning founded by Cyrus Pitt Grosvenor

Cyrus Pitt Grosvenor (October 18, 1792 – February 11, 1879) was an American Baptist minister known for his anti-slavery views. He founded the abolitionist American Baptist Free Mission Society, which did not allow slaveowners to be missionaries, ...

, that accepted all students without prejudice. It was the first college to have black professors teaching white students. However, when a black male faculty member, William G. Allen

William Gustavus Allen (c. 1820 – 1 May 1888) was an African-American academic, intellectual, and lecturer. For a time he co-edited ''The National Watchman,'' an abolitionist newspaper. While studying law in Boston he lectured widely on abolitio ...

, married a white student, they had to flee the country for England, never to return.

Dutch rule

Initial group of slaves

In 1613,Juan (Jan) Rodriguez

Juan Rodriguez (Dutch: , Portuguese: ) was one of the first documented non-indigenous inhabitants to live on Manhattan Island. As such, he is considered the first non-native resident of what would eventually become New York City.

As he was born ...

from Santo Domingo

, total_type = Total

, population_density_km2 = auto

, timezone = AST (UTC −4)

, area_code_type = Area codes

, area_code = 809, 829, 849

, postal_code_type = Postal codes

, postal_code = 10100–10699 ( Distrito Nacional)

, webs ...

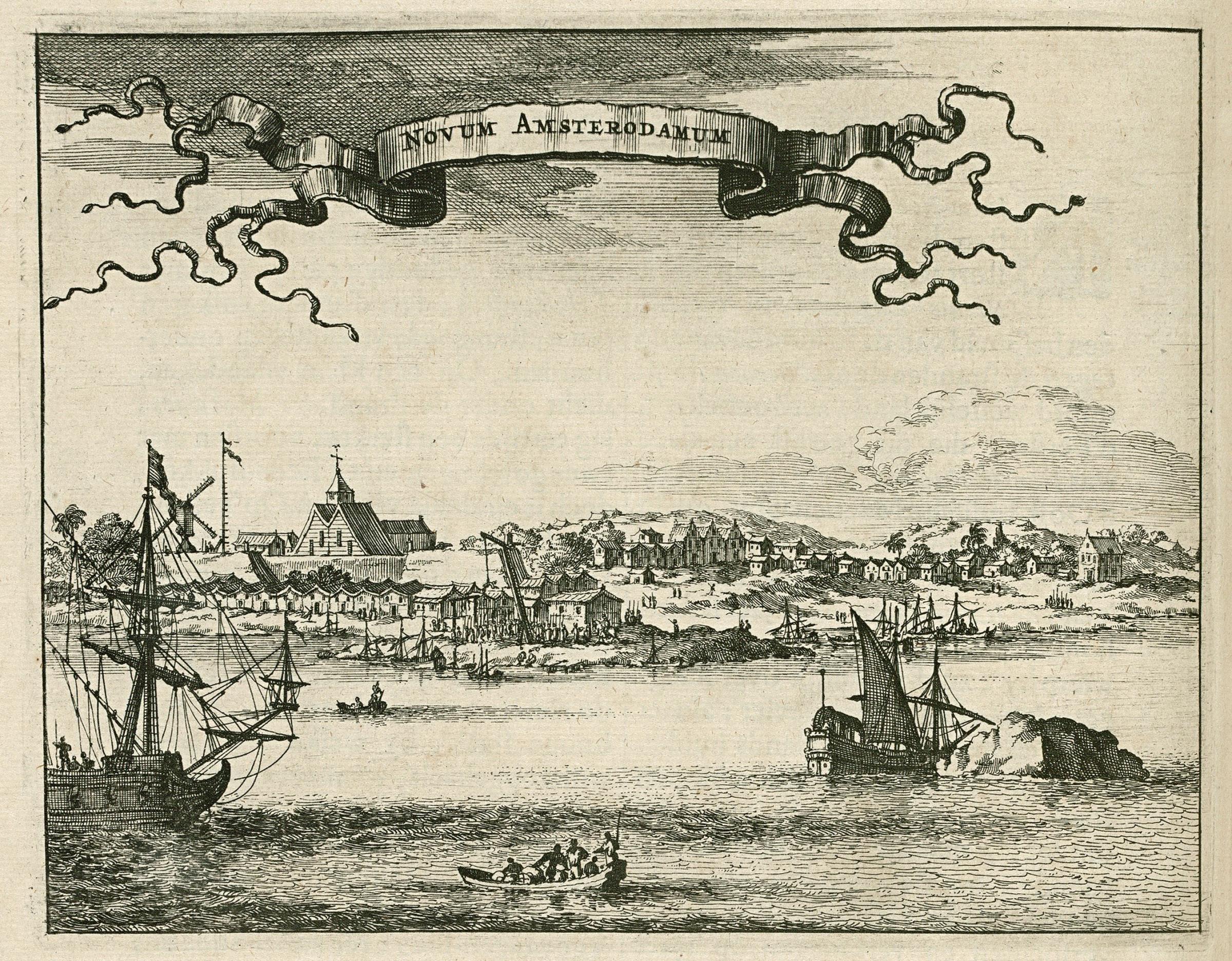

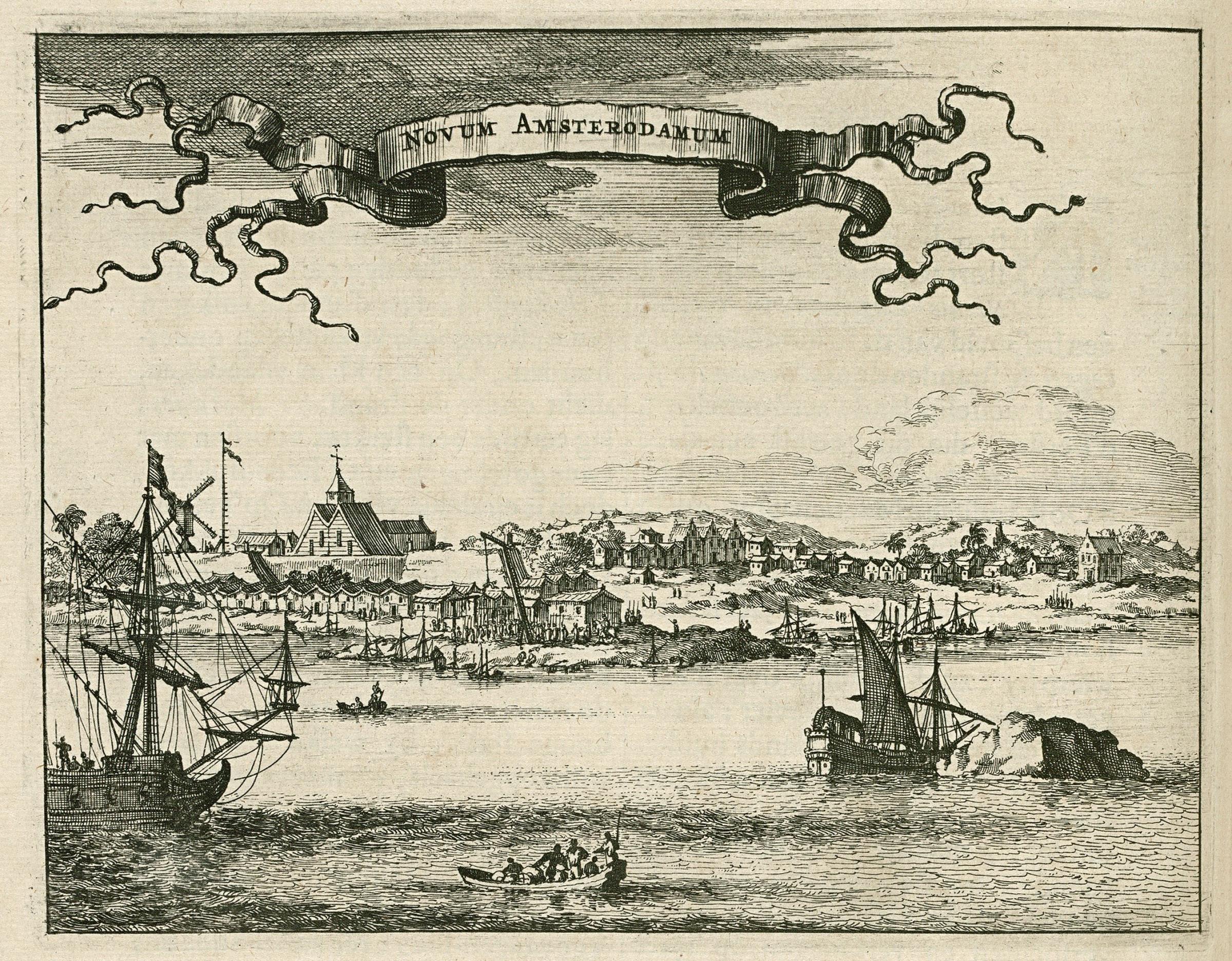

became the first non-indigenous person to settle in what was then known as New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

. Of Portuguese and West African descent, he was a free man.

Systematic slavery

Slavery and enslavement are both the state and the condition of being a slave—someone forbidden to quit one's service for an enslaver, and who is treated by the enslaver as property. Slavery typically involves slaves being made to perf ...

began in 1626, when eleven captive Africans arrived on a Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company ( nl, Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, ''WIC'' or ''GWC''; ; en, Chartered West India Company) was a chartered company of Dutch merchants as well as foreign investors. Among its founders was Willem Usselincx ...

ship in the New Amsterdam

New Amsterdam ( nl, Nieuw Amsterdam, or ) was a 17th-century Dutch settlement established at the southern tip of Manhattan Island that served as the seat of the colonial government in New Netherland. The initial trading ''factory'' gave rise ...

harbor. Historian Ira Berlin called them Atlantic Creole

Atlantic Creole is a cultural identifier of those with origins in the transatlantic settlement of the Americas via Europe and Africa. Their first names—like Paul, Simon, and John—indicated if they had European heritage. Their last names indicated where they came from, like Portuguese, d'Congo, or d'Angola. People from the Congo or Angola were known for their mechanical skills and docile manners. Six slaves had names that indicated a connection with New Amsterdam, such as Manuel Gerritsen, which he likely received after their arrival in New Amsterdam and to differentiate from repeated first names. Men were laborers who worked the fields, built forts and roads, and performed other forms of labor. According to the principle of '' In February 1644, the eleven slaves petitioned

In February 1644, the eleven slaves petitioned

, ''Selected Rensselaerwicjk Papers'', New York State Library, 1991

In 1664, the English took over New Amsterdam and the colony. They continued to import slaves to support the work needed. Enslaved Africans performed a wide variety of skilled and unskilled jobs, mostly in the burgeoning port city and surrounding agricultural areas. In 1703, more than 42% of

In 1664, the English took over New Amsterdam and the colony. They continued to import slaves to support the work needed. Enslaved Africans performed a wide variety of skilled and unskilled jobs, mostly in the burgeoning port city and surrounding agricultural areas. In 1703, more than 42% of  As in other slaveholding societies, the city was swept by periodic fears of slave revolt. Incidents were misinterpreted under such conditions. In what was called the

As in other slaveholding societies, the city was swept by periodic fears of slave revolt. Incidents were misinterpreted under such conditions. In what was called the

African Americans fought on both sides in the

African Americans fought on both sides in the

, New York State Archives, retrieved February 11, 2012 In the 1826 election, only 16 blacks voted in New York City. In 1846, a referendum to repeal this property requirement was roundly defeated. "As late as 1869, a majority of the state's voters cast ballots in favor of retaining property qualifications that kept New York's polls closed to many blacks. African-American men did not obtain equal voting rights in New York until ratification of the

"African Burial Ground National Monument"

, National Park Service; retrieved December 29, 2007

''Slavery in New York''

October 2005 – September 2007, an exhibition by the

"Interview: James Oliver Horton: Exhibit Reveals History of Slavery in New York City"

PBS ''Newshour'', January 25, 2007

Slavery In Mamaroneck Township

Larchmont Website {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Slavery In New York African diaspora history Pre-statehood history of New York (state)

partus sequitur ventrem

''Partus sequitur ventrem'' (L. "That which is born follows the womb"; also ''partus'') was a legal doctrine passed in colonial Virginia in 1662 and other English crown colonies in the Americas which defined the legal status of children born th ...

'' adopted from southern colonies, children born to enslaved women were considered born into slavery, regardless of the ethnicity or status of the father. In February 1644, the eleven slaves petitioned

In February 1644, the eleven slaves petitioned Willem Kieft

Willem Kieft (September 1597 – September 27, 1647) was a Dutch merchant and the Director of New Netherland (of which New Amsterdam was the capital) from 1638 to 1647.

Life and career

Willem Kieft was appointed to the rank of director ...

, the director general for the colony, for their freedom. This was a time when there were skirmishes with Native American people and the Dutch wanted blacks to help protect their settlements and did not want the slaves to join the Native Americans. These eleven slaves were granted partial freedom, where they could buy land and a home and earn a wage from their master, and later full freedom. Their children remained in slavery. By 1664, the original eleven slaves, as well as other slaves who had attained half-freedom, for a total of at least 30 black landowners, lived on Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

near the Fresh Water Pond.

Slave trade

For more than two decades after the first shipment, the Dutch West India Company was dominant in the importation of slaves from the coasts of Africa. A number of slaves were imported directly from the company's stations inAngola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

to New Netherland.

Due to a lack of workers in the colony, it relied upon on African slaves, who were described by the Dutch as "proud and treacherous", a stereotype for African-born slaves. The Dutch West India Company allowed New Netherlanders to trade slaves from Angola

, national_anthem = "Angola Avante"()

, image_map =

, map_caption =

, capital = Luanda

, religion =

, religion_year = 2020

, religion_ref =

, coordinat ...

for "seasoned" African slaves from the Dutch West Indies

The Dutch Caribbean (historically known as the Dutch West Indies) are the territories, colonies, and countries, former and current, of the Dutch Empire and the Kingdom of the Netherlands in the Caribbean Sea. They are in the north and south-wes ...

, particularly Curaçao

Curaçao ( ; ; pap, Kòrsou, ), officially the Country of Curaçao ( nl, Land Curaçao; pap, Pais Kòrsou), is a Lesser Antilles island country in the southern Caribbean Sea and the Dutch Caribbean region, about north of the Venezuela coa ...

, who sold for more than other slaves. They also bought slaves that came from privateers of Spanish slave ships. For instance, ''La Garce'' a French privateer, arrived in New Amsterdam in 1642 with Spanish Negroes that were captured from a Spanish ship. Although they claimed to be free, and not African, the Dutch sold them as slaves due to their skin color.

Slaves in the north were often owned by notable people like Benjamin Franklin

Benjamin Franklin ( April 17, 1790) was an American polymath who was active as a writer, scientist, inventor, statesman, diplomat, printer, publisher, and political philosopher. Encyclopædia Britannica, Wood, 2021 Among the leading int ...

, William Penn

William Penn ( – ) was an English writer and religious thinker belonging to the Religious Society of Friends (Quakers), and founder of the Province of Pennsylvania, a North American colony of England. He was an early advocate of democracy a ...

and John Hancock

John Hancock ( – October 8, 1793) was an American Founding Father, merchant, statesman, and prominent Patriot of the American Revolution. He served as president of the Second Continental Congress and was the first and third Governor o ...

. In New Amsterdam, William Henry Seward

William Henry Seward (May 16, 1801 – October 10, 1872) was an American politician who served as United States Secretary of State from 1861 to 1869, and earlier served as governor of New York and as a United States Senator. A determined oppon ...

grew up in a slave-owning family. Against slavery, he became Abraham Lincoln

Abraham Lincoln ( ; February 12, 1809 – April 15, 1865) was an American lawyer, politician, and statesman who served as the 16th president of the United States from 1861 until his assassination in 1865. Lincoln led the nation throu ...

's Secretary of State during the Civil War.

Unlike slaves from other colonies, slaves in New Amsterdam could sue another person whether white or black. Early instances included suits filed for lost wages and damages when a slave's pig was injured by a white man's dog. Slaves could also be sued.

Partial and full freedom

By 1644, some slaves had earned partial freedom, or half-freedom, in New Amsterdam and were able to earn wages. UnderRoman-Dutch law

Roman-Dutch law ( Dutch: ''Rooms-Hollands recht'', Afrikaans: ''Romeins-Hollandse reg'') is an uncodified, scholarship-driven, and judge-made legal system based on Roman law as applied in the Netherlands in the 17th and 18th centuries. As such, ...

they had other rights in the commercial economy, and intermarriage with working-class whites was frequent. Land grant records show that Land of the Blacks was located just north of New Amsterdam. As the English began to seize New Amsterdam in 1664, the Dutch freed about 40 men and women who had been granted half-slave status, to ensure that the English would not keep them enslaved. The new freemen had their original land grants finalized and all grants were officially marked as owned by the new freemen.Peter R. Christoph, "Freedmen of New Amsterdam", ''Selected Rensselaerwicjk Papers'', New York State Library, 1991

English rule

In 1664, the English took over New Amsterdam and the colony. They continued to import slaves to support the work needed. Enslaved Africans performed a wide variety of skilled and unskilled jobs, mostly in the burgeoning port city and surrounding agricultural areas. In 1703, more than 42% of

In 1664, the English took over New Amsterdam and the colony. They continued to import slaves to support the work needed. Enslaved Africans performed a wide variety of skilled and unskilled jobs, mostly in the burgeoning port city and surrounding agricultural areas. In 1703, more than 42% of New York City

New York, often called New York City or NYC, is the List of United States cities by population, most populous city in the United States. With a 2020 population of 8,804,190 distributed over , New York City is also the L ...

's households held slaves, a percentage higher than in the cities of Boston

Boston (), officially the City of Boston, is the state capital and most populous city of the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, as well as the cultural and financial center of the New England region of the United States. It is the 24th- mo ...

and Philadelphia

Philadelphia, often called Philly, is the largest city in the Commonwealth of Pennsylvania, the sixth-largest city in the U.S., the second-largest city in both the Northeast megalopolis and Mid-Atlantic regions after New York City. Since ...

, and second only to Charleston in the South.

In 1708, the New York Colonial Assembly passed a law entitled "Act for Preventing the Conspiracy of Slaves" which prescribed a death sentence for any slave who murdered or attempted to murder his or her master. This law, one of the first of its kind in Colonial America, was in part a reaction to the murder of William Hallet III and his family in Newtown (Queens

Queens is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Queens County, in the U.S. state of New York. Located on Long Island, it is the largest New York City borough by area. It is bordered by the borough of Brooklyn at the western tip of Long ...

).

In 1711, a formal slave market was established at the end of Wall Street

Wall Street is an eight-block-long street in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan in New York City. It runs between Broadway in the west to South Street and the East River in the east. The term "Wall Street" has become a metonym for ...

on the East River

The East River is a saltwater tidal estuary in New York City. The waterway, which is actually not a river despite its name, connects Upper New York Bay on its south end to Long Island Sound on its north end. It separates the borough of Quee ...

, and it operated until 1762.

An act of the New York General Assembly

The General Assembly of New York, commonly known internationally as the New York General Assembly, and domestically simply as General Assembly, was the supreme legislative body of the Province of New York during its period of proprietal colon ...

, passed in 1730, the last of a series of New York slave codes

The New York slave codes were a series of slave codes

The slave codes were laws relating to slavery and enslaved people, specifically regarding the Atlantic slave trade and chattel slavery in the Americas.

Most slave codes were concerned with ...

, provided that:

Forasmuch as the number of slaves in the cities of New York and Albany, as also within the several counties, towns and manors within this colony, doth daily increase, and that they have oftentimes been guilty of confederating together in running away, and of other ill and dangerous practices, be it therefore unlawful for above three slaves to meet together at any time, nor at any other place, than when it shall happen they meet in some servile employment for their masters' or mistresses' profit, and by their masters' or mistresses' consent, upon penalty of being whipped upon the naked back, at the discretion of any one justice of the peace, not exceeding forty lashes for each offense.Manors and towns could appoint a common whipper at no more than three shillings per person. Blacks were given the lowest status jobs, the ones the Dutch did not want to perform, like meting out corporal punishment and executions.

As in other slaveholding societies, the city was swept by periodic fears of slave revolt. Incidents were misinterpreted under such conditions. In what was called the

As in other slaveholding societies, the city was swept by periodic fears of slave revolt. Incidents were misinterpreted under such conditions. In what was called the New York Conspiracy of 1741

The Conspiracy of 1741, also known as the Slave Insurrection of 1741, was a purported plot by slaves and poor whites in the British colony of New York in 1741 to revolt and level New York City with a series of fires. Historians disagree as ...

, city officials believed a revolt had started. Over weeks, they arrested more than 150 slaves and 20 white men, trying and executing several, in the belief they had planned a revolt. Historian Jill Lepore

Jill Lepore is an American historian and journalist. She is the David Woods Kemper '41 Professor of American History at Harvard University and a staff writer at '' The New Yorker'', where she has contributed since 2005. She writes about America ...

believes whites unjustly accused and executed many blacks in this event.

In 1753, the Assembly provided there should be paid "for every negro, mulatto or other slave, of four years old and upwards, imported directly from Africa, five ounces of Sevil ePillar or Mexico plate ilver or forty shillings in bills of credit made current in this colony."

American Revolution

African Americans fought on both sides in the

African Americans fought on both sides in the American Revolution

The American Revolution was an ideological and political revolution that occurred in British America between 1765 and 1791. The Americans in the Thirteen Colonies formed independent states that defeated the British in the American Revoluti ...

. Many slaves chose to fight for the British, as they were promised freedom by General Guy Carleton in exchange for their service. After the British occupied New York City in 1776, slaves escaped to their lines for freedom. The black population in New York grew to 10,000 by 1780, and the city became a center of free blacks in North America. The fugitives included Deborah Squash and her husband Harvey, slaves of George Washington

George Washington (February 22, 1732, 1799) was an American military officer, statesman, and Founding Father who served as the first president of the United States from 1789 to 1797. Appointed by the Continental Congress as commander of ...

, who escaped from his plantation in Virginia and reached freedom in New York.

In 1781, the state of New York offered slaveholders a financial incentive to assign their slaves to the military, with the promise of freedom at war's end for the slaves. In 1783, black men made up one-quarter of the rebel militia

A militia () is generally an army or some other fighting organization of non-professional soldiers, citizens of a country, or subjects of a state, who may perform military service during a time of need, as opposed to a professional force of r ...

in White Plains, who were to march to Yorktown, Virginia

Yorktown is a census-designated place (CDP) in York County, Virginia. It is the county seat of York County, one of the eight original shires formed in colonial Virginia in 1682. Yorktown's population was 195 as of the 2010 census, while York Co ...

for the last engagements.

By the Treaty of Paris (1783)

The Treaty of Paris, signed in Paris by representatives of King George III of Great Britain and representatives of the United States of America on September 3, 1783, officially ended the American Revolutionary War and overall state of conflict ...

, the United States required that all American property, including slaves, be left in place, but General Guy Carleton followed through on his commitment to the freedmen. When the British evacuated from New York, they transported 3,000 Black Loyalist

Black Loyalists were people of African descent who sided with the Loyalists during the American Revolutionary War. In particular, the term refers to men who escaped enslavement by Patriot masters and served on the Loyalist side because of the C ...

s on ships to Nova Scotia

Nova Scotia ( ; ; ) is one of the thirteen provinces and territories of Canada. It is one of the three Maritime provinces and one of the four Atlantic provinces. Nova Scotia is Latin for "New Scotland".

Most of the population are native Eng ...

(now Maritime Canada

The Maritimes, also called the Maritime provinces, is a region of Eastern Canada consisting of three provinces: New Brunswick, Nova Scotia, and Prince Edward Island. The Maritimes had a population of 1,899,324 in 2021, which makes up 5.1% of Ca ...

), as recorded in the ''Book of Negroes

The ''Book of Negroes'' is a document created by Brigadier General Samuel Birch, under the direction of Sir Guy Carleton, that records names and descriptions of 3,000 Black Loyalists, enslaved Africans who escaped to the British lines during ...

'' at the National Archives of Great Britain and the ''Black Loyalists Directory'' at the National Archives at Washington. With British support, in 1792 a large group of these Black Britons

Black British people are a multi-ethnic group of British citizens of either African or Afro-Caribbean descent.Gadsby, Meredith (2006), ''Sucking Salt: Caribbean Women Writers, Migration, and Survival'', University of Missouri Press, pp. 76–7 ...

left Nova Scotia to create an independent colony in Sierra Leone

Sierra Leone,)]. officially the Republic of Sierra Leone, is a country on the southwest coast of West Africa. It is bordered by Liberia to the southeast and Guinea surrounds the northern half of the nation. Covering a total area of , Sierr ...

.

Gradual abolition

In 1781, the state legislature voted to free those slaves who had fought for three years with the rebels or were regularly discharged during the Revolution. The New York Manumission Society was founded in 1785, and worked to prohibit the international slave trade and to achieve abolition. It established the African Free School in New York City, the first formal educational institution for blacks in North America. It served both free and slave children. The school expanded to seven locations and produced some of its students advanced to higher education and careers. These includedJames McCune Smith

James McCune Smith (April 18, 1813 – November 17, 1865) was an American physician, apothecary, abolitionist, and author who was born in Manhattan. He was the first African American to hold a medical degree from the University of Glasgow in Sco ...

, who gained his medical degree with honors at the University of Glasgow

, image = UofG Coat of Arms.png

, image_size = 150px

, caption = Coat of arms

Flag

, latin_name = Universitas Glasguensis

, motto = la, Via, Veritas, Vita

, ...

after being denied admittance to two New York colleges. He returned to practice in New York and also published numerous articles in medical and other journals.

By 1790, one in three blacks in New York state were free. Especially in areas of concentrated population, such as New York City, they organized as an independent community, with their own churches, benevolent and civic organizations, and businesses that catered to their interests.

Conversion to indentured servitude

Although there was movement towards abolition of slavery, the legislature took steps to characterizeindentured servitude

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an " indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayme ...

for blacks in a way that redefined slavery in the state. Slavery was important economically, both in New York City and in agricultural areas, such as Brooklyn. In 1799, the legislature passed the ''Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery

An Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery, passed by the Fifth Pennsylvania General Assembly on 1 March 1780, prescribed an end for slavery in Pennsylvania. It was the first act abolishing slavery in the course of human history to be adopted by a ...

''. It freed no living slave. It declared children of slaves born after July 4, 1799, to be legally free, but the children had to serve an extended period of indentured servitude: to the age of 28 for males and to 25 for females. Slaves born before that date were redefined as indentured servants

Indentured servitude is a form of labor in which a person is contracted to work without salary for a specific number of years. The contract, called an "indenture", may be entered "voluntarily" for purported eventual compensation or debt repayment, ...

and could not be sold, but they had to continue their unpaid labor.

From 1800 to 1827, white and black abolitionists worked to end slavery and attain full citizenship in New York. During this time, there was a rise in white supremacy

White supremacy or white supremacism is the belief that white people are superior to those of other races and thus should dominate them. The belief favors the maintenance and defense of any power and privilege held by white people. White ...

, which was at odds with the increased anti-slavery efforts of the early 19th century. Peter Williams Jr.

Peter Williams Jr. (1786–1840) was an African-American Episcopal priest, the second ordained in the United States and the first to serve in New York City. He was an abolitionist who also supported free black emigration to Haiti, the black republ ...

, an influential black abolitionist and minister, encouraged other blacks to "by a strict obedience and respect to the laws of the land, form an invulnerable bulwark against the shafts of malice" to better the chances of freedom and a better life.

African Americans' participation as soldiers in defending the state during the War of 1812

The War of 1812 (18 June 1812 – 17 February 1815) was fought by the United States of America and its indigenous allies against the United Kingdom and its allies in British North America, with limited participation by Spain in Florida. It be ...

added to public support for their full rights to freedom. In 1817, the state freed all slaves born before July 4, 1799 (the date of the gradual abolition law), to be effective in 1827. It continued with the indenture of children born to slave mothers until their 20s, as noted above. Because of the gradual abolition laws, there were children still bound in apprenticeships when their parents were free.Harris, Leslie M. ''In the Shadow of Slavery: African Americans in New York City, 1626–1863''. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2003: 93–95. This encouraged African-American anti-slavery activists.

In ''Sketches of America'' (1818), British author Henry Bradshaw Fearon, who visited the young United States on a fact-finding mission to inform Britons considering emigration, described the situation in New York City as he found it in August 1817:

New York is called a "free state:" that it may be so so ''theoretically,'' or when compared with its southern neighbors; but if, in England, we saw in the Times newspaper such advertisements as the following ee image to right we should conclude that freedom from slavery existed only in words.

Full freedom in 1827

On July 5, 1827, the African-American community celebrated finalemancipation

Emancipation generally means to free a person from a previous restraint or legal disability. More broadly, it is also used for efforts to procure economic and social rights, political rights or equality, often for a specifically disenfranch ...

in the state with a parade through New York City. A distinctive Fifth of July

''Fifth of July'' is a 1978 play by Lanford Wilson. Set in rural Missouri in 1977, it revolves around the Talley family and their friends, and focuses on the disillusionment in the wake of the Vietnam War. It premiered on Broadway in 1980 and w ...

celebration was chosen over July 4, because the national holiday was not seen as meant for blacks, as Frederick Douglass

Frederick Douglass (born Frederick Augustus Washington Bailey, February 1817 or 1818 – February 20, 1895) was an American social reformer, abolitionist, orator, writer, and statesman. After escaping from slavery in Maryland, he became ...

stated later in his famous ''What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?

"What to the Slave Is the Fourth of July?" was a speech delivered by Frederick Douglass on July 5, 1852, at Corinthian Hall in Rochester, New York, at a meeting organized by the Rochester Ladies' Anti-Slavery Society. In the address, Douglass ...

'' speech of July 5, 1852.

Right to vote

New York residents were less willing to give blacks equal voting rights. By the constitution of 1777, voting was restricted to free men who could satisfy certain property requirements for value of real estate. This property requirement disfranchised poor men among both blacks and whites. The reformed Constitution of 1821 eliminated the property requirement for white men, but set a prohibitive requirement of $250 (), about the price of a modest house, for black men."African American Voting Rights", New York State Archives, retrieved February 11, 2012 In the 1826 election, only 16 blacks voted in New York City. In 1846, a referendum to repeal this property requirement was roundly defeated. "As late as 1869, a majority of the state's voters cast ballots in favor of retaining property qualifications that kept New York's polls closed to many blacks. African-American men did not obtain equal voting rights in New York until ratification of the

Fifteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

The Fifteenth Amendment (Amendment XV) to the United States Constitution prohibits the federal government and each state from denying or abridging a citizen's right to vote "on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude." It was ...

, in 1870."

''Freedom's Journal''

Beginning March 16, 1827,John Brown Russwurm

John Brown Russwurm (October 1, 1799 – June 9, 1851) was an abolitionist, newspaper publisher, and colonizer of Liberia, where he moved from the United States. He was born in Jamaica to an English father and enslaved mother. As a child he t ...

published ''Freedom's Journal

''Freedom's Journal'' was the first African-American owned and operated newspaper published in the United States. Founded by Rev. John Wilk and other free Black men in New York City, it was published weekly starting with the 16 March 1827 issue. ...

'', written by and directed to African Americans. Samuel Cornish and John Russwurm were editors of the journal; they used it to appeal to African Americans across the nation.Capie, Julia M. "Freedom of Unspoken Speech: Implied Defamation and Its Constitutional Limitations". ''Touro Law Review'' 31, no. 4 (October 2015): 675. The powerful words published spread rapid positive influence to African Americans who could help establish a new community. The emergence of an African-American journal was a very important movement in New York. It showed that blacks could gain education and be part of literate society.

White newspapers published a fictional "Bobalition" print series. This was made in mockery of blacks, using the way an uneducated colored person would pronounce abolition.

Illegal slave trade

Beginning in the early 1850s, New York City became a key center for the Atlantic slave trade, which Congress had banned in 1807. The main slave traders arrived in Manhattan during this period from Brazil and Africa, and became known as the Portuguese Company. Two of the key traffickers were Manoel Basilio da Cunha Reis and Jose Maia Ferreira. They posed as merchants in legal trade but in fact bought up vessels which they sent to the African coast, usually the Congo River region. The vast majority of vessels were ultimately bound for Cuba. In total over 400 illegal slave vessels left the United States during this period, the vast majority from New York, although others departed from New Orleans, Boston, and other minor ports. This trade was enabled by American captains and sailors, corrupt U.S. officials in New York, and by the ruling Democratic Party, which had limited interest in suppressing the trade.New York City and Brooklyn

New York City Mayor Fernando Wood was strongly pro-slavery. He was a leader of the peace Democrats, and in the opposition to the 13th Amendment ending slavery. Just before theCivil War

A civil war or intrastate war is a war between organized groups within the same state (or country).

The aim of one side may be to take control of the country or a region, to achieve independence for a region, or to change government polici ...

he had seriously proposed to the City Council that the city secede from the Union to form the ''Free City of Tri-Insula'' (''insula'' means "island" in Latin

Latin (, or , ) is a classical language belonging to the Italic languages, Italic branch of the Indo-European languages. Latin was originally a dialect spoken in the lower Tiber area (then known as Latium) around present-day Rome, but through ...

), incorporating Manhattan

Manhattan (), known regionally as the City, is the most densely populated and geographically smallest of the five boroughs of New York City. The borough is also coextensive with New York County, one of the original counties of the U.S. state ...

, Staten Island

Staten Island ( ) is a Boroughs of New York City, borough of New York City, coextensive with Richmond County, in the U.S. state of New York (state), New York. Located in the city's southwest portion, the borough is separated from New Jersey b ...

, and Long Island

Long Island is a densely populated island in the southeastern region of the U.S. state of New York, part of the New York metropolitan area. With over 8 million people, Long Island is the most populous island in the United States and the 18 ...

except for pro-Union Brooklyn

Brooklyn () is a borough of New York City, coextensive with Kings County, in the U.S. state of New York. Kings County is the most populous county in the State of New York, and the second-most densely populated county in the United States, be ...

. The City Council approved the plan, but rescinded its approval 3 months later, after the Battle of Fort Sumter

The Battle of Fort Sumter (April 12–13, 1861) was the bombardment of Fort Sumter near Charleston, South Carolina by the South Carolina militia. It ended with the surrender by the United States Army, beginning the American Civil War.

Fol ...

.

In contrast, Brooklyn was "a sanctuary city before its time", with one of the largest and most politically aware Black communities in the United States. Henry Ward Beecher

Henry Ward Beecher (June 24, 1813 – March 8, 1887) was an American Congregationalist clergyman, social reformer, and speaker, known for his support of the abolition of slavery, his emphasis on God's love, and his 1875 adultery trial. His r ...

, brother of Harriet Beecher Stowe

Harriet Elisabeth Beecher Stowe (; June 14, 1811 – July 1, 1896) was an American author and abolitionist. She came from the religious Beecher family and became best known for her novel '' Uncle Tom's Cabin'' (1852), which depicts the har ...

, pastor at the Plymouth Church in Brooklyn Heights

Brooklyn Heights is a residential neighborhood within the New York City borough of Brooklyn. The neighborhood is bounded by Old Fulton Street near the Brooklyn Bridge on the north, Cadman Plaza West on the east, Atlantic Avenue on the south, ...

, was one of the country's most active abolitionists

Abolitionism, or the abolitionist movement, is the movement to end slavery. In Western Europe and the Americas, abolitionism was a historic movement that sought to end the Atlantic slave trade and liberate the enslaved people.

The Britis ...

.

African Burial Ground

In 1991, a construction project required an archaeological and cultural study of 290 Broadway inLower Manhattan

Lower Manhattan (also known as Downtown Manhattan or Downtown New York) is the southernmost part of Manhattan, the central borough for business, culture, and government in New York City, which is the most populated city in the United States with ...

to comply with the National Historic Preservation Act of 1966

The National Historic Preservation Act (NHPA; Public Law 89-665; 54 U.S.C. 300101 ''et seq.'') is legislation intended to preserve historic and archaeological sites in the United States of America. The act created the National Register of Histor ...

before construction could begin. During the excavation and study, human remains were found in a former six-acre burial ground for African Americans that dated from the mid-1630s to 1795. It is believed that there are more than 15,000 skeletal remains of colonial New York's free and enslaved blacks. It is the country's largest and earliest burial ground for African-Americans.

This discovery demonstrated the large-scale importance of slavery and African Americans to New York and national history and economy. The African Burial Ground

African Burial Ground National Monument is a monument at Duane Street and African Burial Ground Way (Elk Street) in the Civic Center section of Lower Manhattan, New York City. Its main building is the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway. ...

has been designated as a National Historic Landmark

A National Historic Landmark (NHL) is a building, district, object, site, or structure that is officially recognized by the United States government for its outstanding historical significance. Only some 2,500 (~3%) of over 90,000 places liste ...

and a National Monument

A national monument is a monument constructed in order to commemorate something of importance to national heritage, such as a country's founding, independence, war, or the life and death of a historical figure.

The term may also refer to a spe ...

for its significance. A memorial and interpretive center for the African Burial Ground have been created to honor those buried and to explore the many contributions of African Americans and their descendants to New York and the nation., National Park Service; retrieved December 29, 2007

See also

*African Americans in New York City

African Americans constitute one of the longer-running ethnic presences in New York City, home to the largest urban African American population, and the world's largest Black population of any city outside Africa, by a significant margin.

Pop ...

* African Burial Ground National Monument

African Burial Ground National Monument is a monument at Duane Street and African Burial Ground Way (Elk Street) in the Civic Center section of Lower Manhattan, New York City. Its main building is the Ted Weiss Federal Building at 290 Broadway ...

* New York Conspiracy of 1741

The Conspiracy of 1741, also known as the Slave Insurrection of 1741, was a purported plot by slaves and poor whites in the British colony of New York in 1741 to revolt and level New York City with a series of fires. Historians disagree as ...

* Human trafficking in New York

* Rose Butler

Rose Butler (November 1799 – 1819) was an enslaved domestic worker in New York City. In July 1819, she was hanged for arson. At the time, the only capital crimes in New York State were first-degree arson and murder. She was the last person execut ...

* Sylvester Manor

Sylvester Manor is a historic manor on Shelter Island in Suffolk County, New York, USA.

History

The land, spanning 8,000 acres on Shelter Island, was acquired by English-born colonist Nathaniel Sylvester in the 17th century. Sylvester and his ...

Notes

References

Further reading

(''most recent first'') * * * *External links

''Slavery in New York''

October 2005 – September 2007, an exhibition by the

New-York Historical Society

The New-York Historical Society is an American history museum and library in New York City, along Central Park West between 76th and 77th Streets, on the Upper West Side of Manhattan. The society was founded in 1804 as New York's first museum ...

"Interview: James Oliver Horton: Exhibit Reveals History of Slavery in New York City"

PBS ''Newshour'', January 25, 2007

Slavery In Mamaroneck Township

Larchmont Website {{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Slavery In New York African diaspora history Pre-statehood history of New York (state)

New York

New York most commonly refers to:

* New York City, the most populous city in the United States, located in the state of New York

* New York (state), a state in the northeastern United States

New York may also refer to:

Film and television

* '' ...

African-American history in New York City

History of racism in New York (state)