The history of printing starts as early as 3000 BCE, when the

proto-Elamite

The Proto-Elamite period, also known as Susa III, is a chronological era in the ancient history of the area of Elam, dating from . In archaeological terms this corresponds to the late Banesh period. Proto-Elamite sites are recognized as the old ...

and

Sumer

Sumer () is the earliest known civilization in the historical region of southern Mesopotamia (south-central Iraq), emerging during the Chalcolithic and early Bronze Ages between the sixth and fifth millennium BC. It is one of the cradles of ...

ian civilizations used cylinder seals to certify documents written in clay tablets . Other early forms include block seals,

hammered coinage, pottery imprints, and cloth printing. Initially a

method of printing patterns on cloth such as silk,

woodblock printing

Woodblock printing or block printing is a technique for printing text, images or patterns used widely throughout East Asia and originating in China in antiquity as a method of printing on textiles and later paper. Each page or image is crea ...

for texts on

paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distribu ...

originated in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

by the 7th century during the

Tang dynasty

The Tang dynasty (, ; zh, t= ), or Tang Empire, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China that ruled from 618 to 907 AD, with an Zhou dynasty (690–705), interregnum between 690 and 705. It was preceded by the Sui dyn ...

, leading to the

spread of book production and woodblock printing in other parts of Asia such as

Korea

Korea ( ko, 한국, or , ) is a peninsular region in East Asia. Since 1945, it has been divided at or near the 38th parallel, with North Korea (Democratic People's Republic of Korea) comprising its northern half and South Korea (Republic ...

and

Japan

Japan ( ja, 日本, or , and formally , ''Nihonkoku'') is an island country in East Asia. It is situated in the northwest Pacific Ocean, and is bordered on the west by the Sea of Japan, while extending from the Sea of Okhotsk in the n ...

. The

Chinese Buddhist

Chinese Buddhism or Han Buddhism ( zh, s=汉传佛教, t=漢傳佛教, p=Hànchuán Fójiào) is a Chinese form of Mahayana Buddhism which has shaped Chinese culture in a wide variety of areas including art, politics, literature, philosophy, ...

''

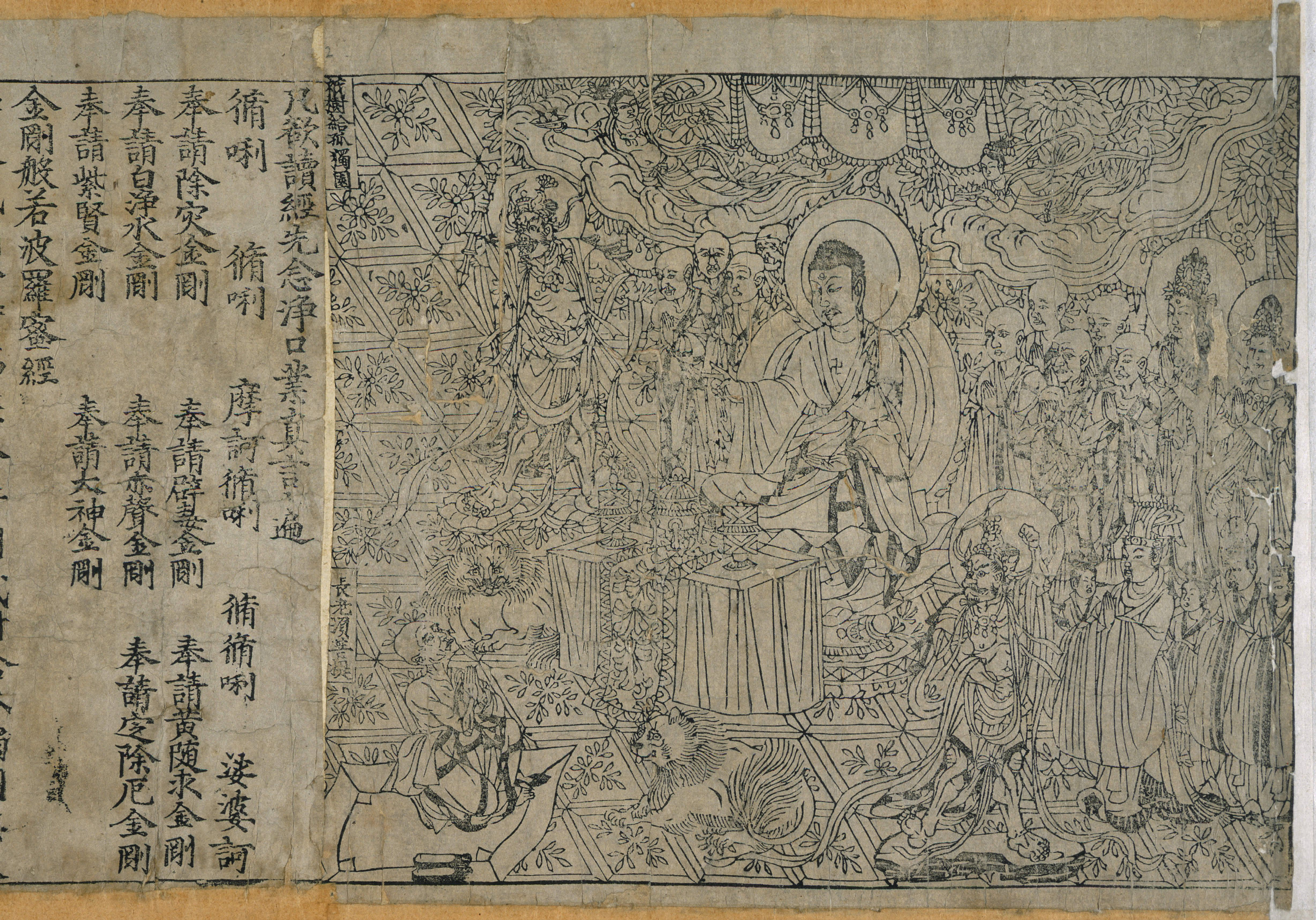

Diamond Sutra'', printed by woodblock on 11 May 868, is the earliest known printed book with a precise publishing date.

Movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation m ...

was invented by

Chinese artisan Bi Sheng

Bi Sheng (; 972–1051 AD) was a Chinese artisan, engineer, and inventor of the world's first movable type technology, with printing being one of the Four Great Inventions. Bi Sheng's system was made of Chinese porcelain and was invented betwe ...

in the 11th century during the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

, but it received limited use compared to woodblock printing. Nevertheless, the technology spread outside China, as the oldest printed book using

metal movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation m ...

was the ''

Jikji'', printed in Korea in 1377 during the

Goryeo

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean kingdom founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392. Goryeo achieved what has been called a "true national unificat ...

era.

Woodblock printing was also used in Europe until the mid-15th century.

Late medieval

The Late Middle Ages or Late Medieval Period was the period of European history lasting from AD 1300 to 1500. The Late Middle Ages followed the High Middle Ages and preceded the onset of the early modern period (and in much of Europe, the Renai ...

German inventor

Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (; – 3 February 1468) was a German inventor and craftsman who introduced letterpress printing to Europe with his movable-type printing press. Though not the first of its kind, earlier designs ...

created the first

printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

based on previously known

mechanical presses and a process for mass-producing

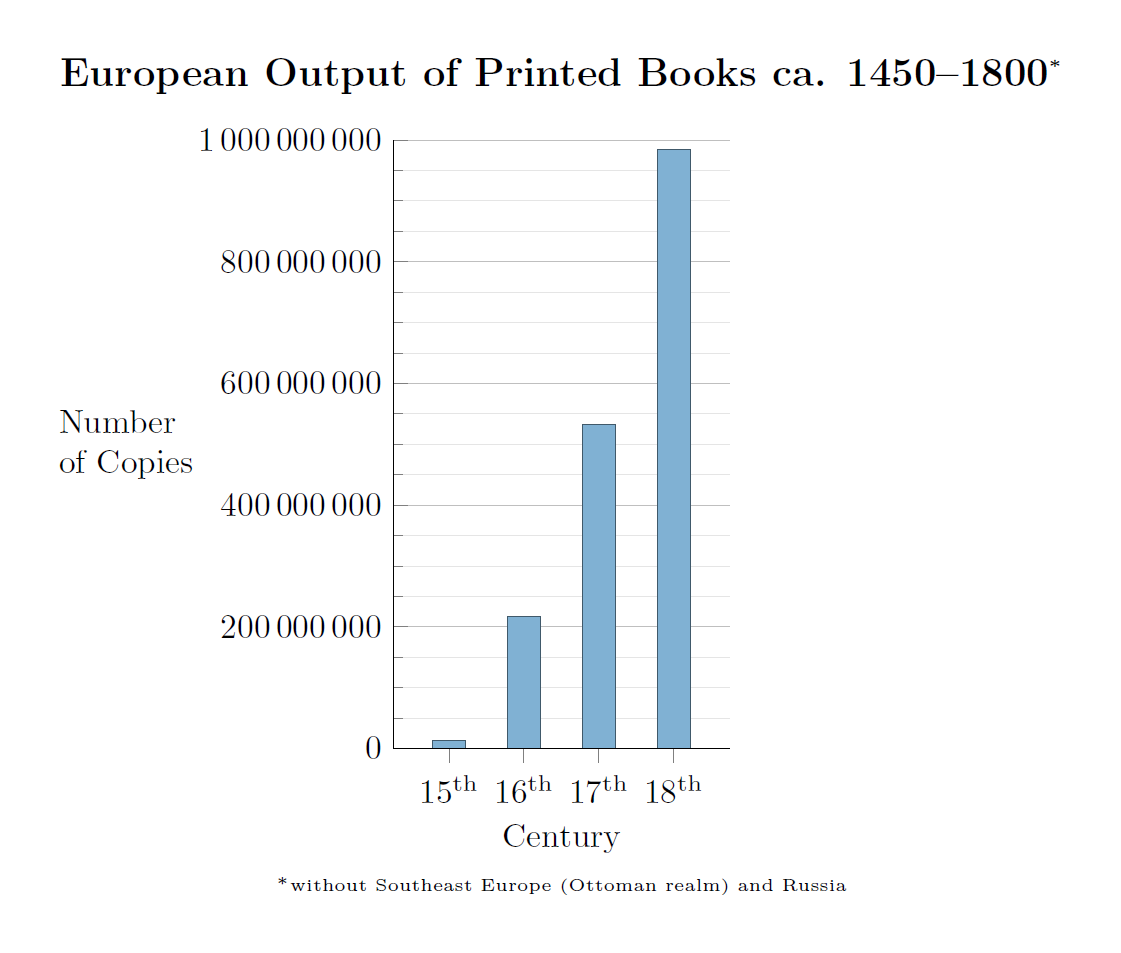

metal type. By the end of the 15th century his invention and widescale circulation of the

Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42) was the earliest major book printed using mass-produced movable metal type in Europe. It marked the start of the " Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of printed ...

became responsible for a burgeoning economical book publishing industry across

Renaissance Europe and eventually among the

colonial publishers and printers that emerged in the British-American colonies. This industry enabled the communication of ideas and sharing of knowledge on an unprecedented scale, leading to the

global spread of the printing press during the

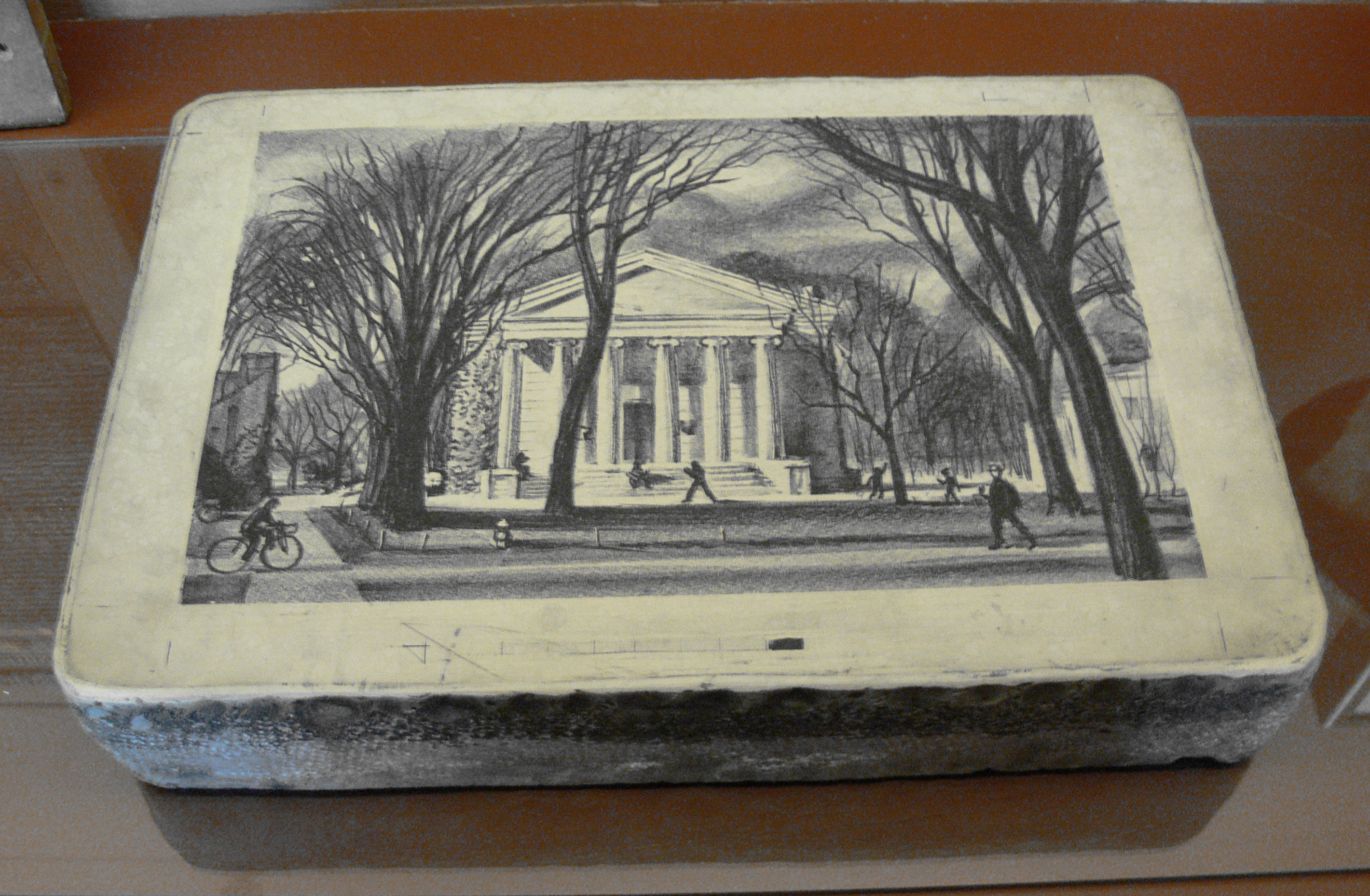

early modern period. Alongside the development of text printing, new and lower-cost methods of image reproduction were developed, including

lithography

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

,

screen printing

Screen printing is a printing technique where a mesh is used to transfer ink (or dye) onto a substrate, except in areas made impermeable to the ink by a blocking stencil. A blade or squeegee is moved across the screen to fill the open me ...

and

photocopying

A photocopier (also called copier or copy machine, and formerly Xerox machine, the generic trademark) is a machine that makes copies of documents and other visual images onto paper or plastic film quickly and cheaply. Most modern photocopier ...

.

Stencil

Hand stencils

Hand stencils, made by blowing pigment over a hand held against a wall, have been found in Asia and Europe dating from over 35,000 years ago, and later prehistoric dates in other continents. After that stencilling has been used as a historic

painting

Painting is the practice of applying paint, pigment, color or other medium to a solid surface (called the "matrix" or "support"). The medium is commonly applied to the base with a brush, but other implements, such as knives, sponges, and a ...

technique on all kinds of materials.

Stencils may have been used to colour cloth for a very long time; the technique probably reached its peak of sophistication in

Katazome and other techniques used on silks for clothes during the

Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was character ...

in Japan. In Europe, from about 1450 AD they were commonly used to colour

old master print

An old master print is a work of art produced by a printing process within the Western tradition. The term remains current in the art trade, and there is no easy alternative in English to distinguish the works of "fine art" produced in printmak ...

s printed in black and white, usually

woodcut

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas tha ...

s. This was especially the case with playing-cards, which continued to be coloured by stencil long after most other subjects for prints were left in black and white. Stencils were used for mass publications, as the type did not have to be hand-written.

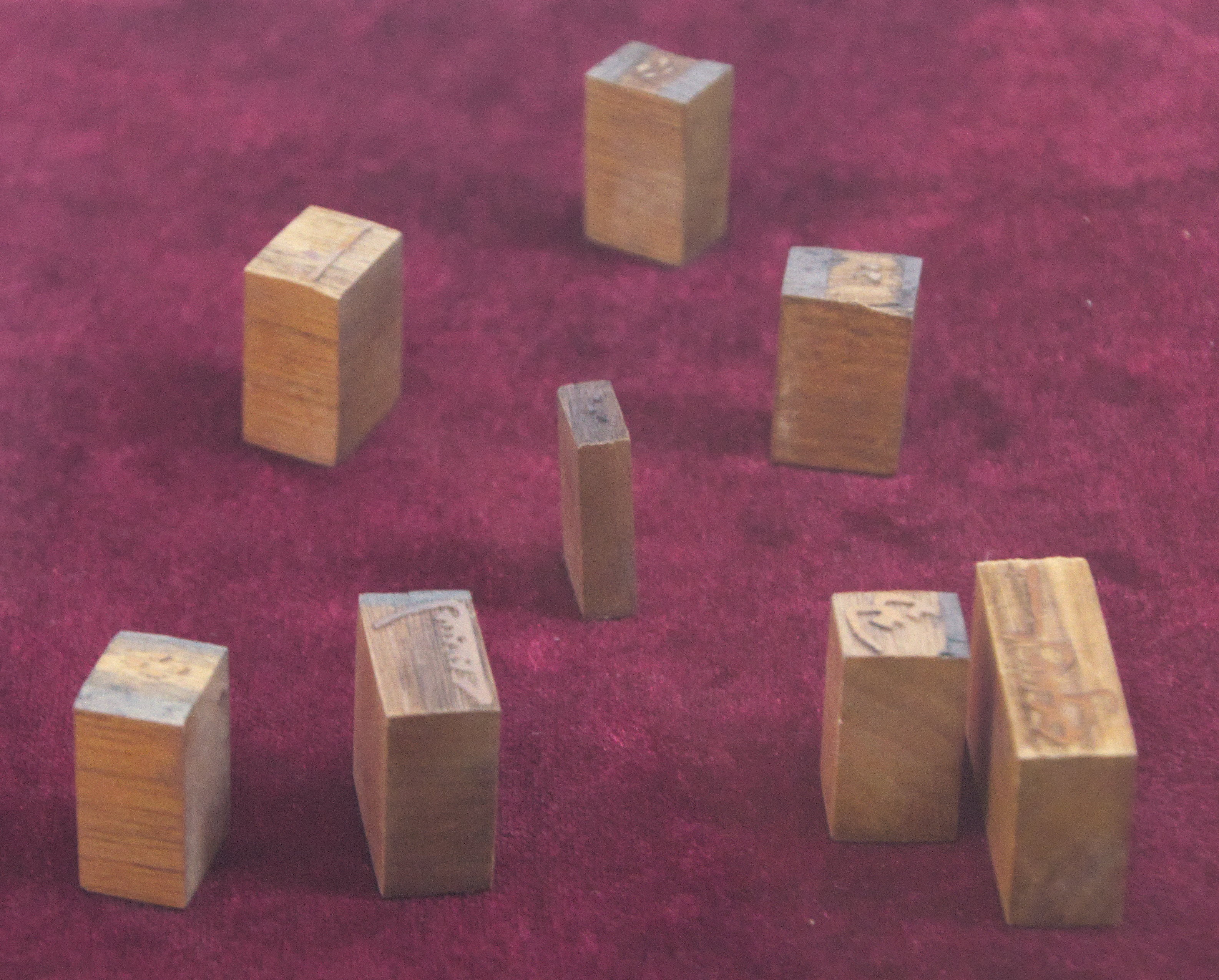

Seals

In China seals were used since at least the

Shang dynasty

The Shang dynasty (), also known as the Yin dynasty (), was a Chinese royal dynasty founded by Tang of Shang (Cheng Tang) that ruled in the Yellow River valley in the second millennium BC, traditionally succeeding the Xia dynasty a ...

. In the

Western Zhou

The Western Zhou ( zh, c=, p=Xīzhōu; c. 1045 BC – 771 BC) was a royal dynasty of China and the first half of the Zhou dynasty. It began when King Wu of Zhou overthrew the Shang dynasty at the Battle of Muye and ended when the Quanrong n ...

, sets of seal stamps were encased in blocks of type and used on clay moulds for casting bronzes. By the end of the 3rd century BC seals were also used for printing on pottery. In the Northern dynasties textual sources contain references to wooden seals with up to 120 characters.

The seals had a religious element to them.

Daoists used seals as healing devices by impressing therapeutic characters onto the flesh of sick people. They were also used to stamp food, creating a talismanic character to ward off disease. The first evidence of these practices appeared under a Buddhist context in the mid 5th century. Centuries later seals were used to create hundreds of Buddha images.

In the West the practice of sealing documents, with an impressed personal, or official insignia, typically from a worn signet ring, became established under the Roman Empire, and continued through the Byzantine, and Holy Roman empires, into the 19th century, when a wet signature became customary.

Stone, clay and bronze blocks

Stone and bronze blocks have been used to print fabric. Archaeological evidence of them have been unearthed at

Mawangdui

Mawangdui () is an archaeological site located in Changsha, China. The site consists of two saddle-shaped hills and contained the tombs of three people from the Changsha Kingdom during the western Han dynasty (206 BC – 9 AD): the Chancellor Li ...

and in the tomb of the King of

Nanyue

Nanyue (), was an ancient kingdom ruled by Chinese monarchs of the Zhao family that covered the modern Chinese subdivisions of Guangdong, Guangxi, Hainan, Hong Kong, Macau, southern Fujian and central to northern Vietnam. Nanyue was establis ...

, while block printed fabrics have been discovered at Mashan Zhuanchang in

Jiangling,

Hubei

Hubei (; ; alternately Hupeh) is a landlocked province of the People's Republic of China, and is part of the Central China region. The name of the province means "north of the lake", referring to its position north of Dongting Lake. The p ...

.

Pliny the Elder

Gaius Plinius Secundus (AD 23/2479), called Pliny the Elder (), was a Roman author, naturalist and natural philosopher, and naval and army commander of the early Roman Empire, and a friend of the emperor Vespasian. He wrote the encyclopedic ' ...

described clay block printing of textiles in 1st century Egypt, with extant Egyptian, Roman, Byzantine, Ukrainian, and Russian examples known, dating from the 4th century CE.

In the 4th century the practice of creating paper rubbings of stone carvings such as calligraphic models and texts took hold in East Asia. Among the earliest evidence of this is a stone inscription cut in mirror image from the early 6th century.

Woodblock printing

Woodblock printing (''diaoban yinshua'' 雕版印刷), known as xylography today, was the first method of printing applied to a paper medium. It became widely used throughout East Asia both as a method for printing on

textile

Textile is an Hyponymy and hypernymy, umbrella term that includes various Fiber, fiber-based materials, including fibers, yarns, Staple (textiles)#Filament fiber, filaments, Thread (yarn), threads, different #Fabric, fabric types, etc. At f ...

s and later, under the influence of

Buddhism

Buddhism ( , ), also known as Buddha Dharma and Dharmavinaya (), is an Indian religion or philosophical tradition based on teachings attributed to the Buddha. It originated in northern India as a -movement in the 5th century BCE, and ...

, on

paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distribu ...

. As a method of printing on cloth, the earliest surviving examples from China date to about 220 AD. ''

Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese art which flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk ta ...

'' is the best known type of

Japanese woodblock art print. Most European uses of the technique on paper are covered by the term

woodcut

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas tha ...

(see below), except for the

block-books produced mainly in the fifteenth century.

Legendary origins

According to the Book of the Southern Qi, in the 480s, a man named Gong Xuanyi (龔玄宜) styled himself Gong the Sage and "said that a supernatural being had given him a 'jade seal jade block writing,' which did not require a brush: one blew on the paper and characters formed." He then used his powers to mystify a local governor. Eventually he was dealt with by the governor's successor, who presumably executed Gong. Timothy Hugh Barrett postulates that Gong's magical jade block was actually a printing device, and Gong was one of the first, if not the first printer. The semi-mythical record of him therefore describes his usage of the printing process to deliberately bewilder onlookers and create an image of mysticism around himself.

In the Sinosphere

The rise of printing was greatly influenced by

Mahayana Buddhism

''Mahāyāna'' (; "Great Vehicle") is a term for a broad group of Buddhist traditions, texts, philosophies, and practices. Mahāyāna Buddhism developed in India (c. 1st century BCE onwards) and is considered one of the three main existing br ...

. According to Mahayana beliefs, religious texts hold intrinsic value for carrying the Buddha's word and act as talismanic objects containing sacred power capable of warding off evil spirits. By copying and preserving these texts, Buddhists could accrue personal merit. As a consequence the idea of printing and its advantages in replicating texts quickly became apparent to Buddhists, who by the 7th century, were using woodblocks to create apotropaic documents. These Buddhist texts were printed specifically as ritual items and were not widely circulated or meant for public consumption. Instead they were buried in consecrated ground. The earliest extant example of this type of printed matter is a fragment of a dhāraṇī (Buddhist spell) miniature scroll written in Sanskrit unearthed in a tomb in

Xi'an

Xi'an ( , ; ; Chinese: ), frequently spelled as Xian and also known by other names, is the capital of Shaanxi Province. A sub-provincial city on the Guanzhong Plain, the city is the third most populous city in Western China, after Chongqi ...

. It is called the ''Great spell of unsullied pure light'' (''Wugou jingguang da tuoluoni jing'' 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經) and was printed using woodblock during the Tang dynasty, c. 650–670 AD. Radiocarbon dating by the

University of Arizona

The University of Arizona (Arizona, U of A, UArizona, or UA) is a Public university, public Land-grant university, land-grant research university in Tucson, Arizona. Founded in 1885 by the 13th Arizona Territorial Legislature, it was the first ...

confirmed that the material was likely produced sometime between 618-770. A similar piece, the ''Saddharma pundarika'' sutra, was also discovered and dated to 690 to 699.

This coincides with the reign of

Wu Zetian

Wu Zetian (17 February 624 – 16 December 705), personal name Wu Zhao, was the ''de facto'' ruler of the Tang dynasty from 665 to 705, ruling first through others and then (from 690) in her own right. From 665 to 690, she was first empres ...

, under which the

Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra

The ''Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra'' (or ''Infinite Life Sutra'', Chinese: ''Fóshuōwúliàngshòujīng'' 佛說無量壽經; Vietnamese: Phật Thuyết Kinh Vô Lượng Thọ; Japanese: Taisho Tripitaka # 360) is one of the two Indian ...

, which advocates the practice of printing apotropaic and merit making texts and images, was translated by Chinese monks. From 658-663,

Xuanzang

Xuanzang (, ; 602–664), born Chen Hui / Chen Yi (), also known as Hiuen Tsang, was a 7th-century Chinese Buddhist monk, scholar, traveler, and translator. He is known for the epoch-making contributions to Chinese Buddhism, the travelogue of ...

printed one million copies of the image of

Puxian Pusa to distribute to Buddhist devotees.

Evidence of woodblock printing appeared in Korea and Japan soon afterward.

The Great Dharani Sutra

The Great Dharani Sutra () is a copy of the Uṣṇīṣa Vijaya Dhāraṇī Sūtra, a scripture of Mahayana Buddhism, which is considered to be one of the oldest printed texts in the world.

Discovery

The Great Dharani Sutra was discovered i ...

( ko, 무구정광대다라니경, translit=Muggujeonggwang Daedharanigyeong

Hanja

Hanja (Hangul: ; Hanja: , ), alternatively known as Hancha, are Chinese characters () used in the writing of Korean. Hanja was used as early as the Gojoseon period, the first ever Korean kingdom.

(, ) refers to Sino-Korean vocabulary, ...

: 無垢淨光大陀羅尼經) was discovered at

Bulguksa, South Korea in 1966 and dated between 704 and 751 in the era of

Later Silla

Unified Silla, or Late Silla (, ), is the name often applied to the Korean kingdom of Silla, one of the Three Kingdoms of Korea, after 668 CE. In the 7th century, a Silla–Tang alliance conquered Baekje and the southern part of Goguryeo in the ...

. The document is printed on a

mulberry

''Morus'', a genus of flowering plants in the family Moraceae, consists of diverse species of deciduous trees commonly known as mulberries, growing wild and under cultivation in many temperate world regions. Generally, the genus has 64 ident ...

paper scroll. A dhāraṇī sutra was printed in Japan around AD 770. One million copies of the sutra, along with other prayers, were ordered to be produced by

Empress Shōtoku

An emperor (from la, imperator, via fro, empereor) is a monarch, and usually the sovereign ruler of an empire or another type of imperial realm. Empress, the female equivalent, may indicate an emperor's wife ( empress consort), mother ( ...

. As each copy was then stored in a tiny wooden pagoda, the copies are together known as the ''

Hyakumantō Darani

The , or the "One Million Pagodas and Dharani Prayers", are a series of Buddhist prayers or spells that were printed on paper and then rolled up and housed in wooden cases that resemble miniature pagodas in both appearance and meaning. Although w ...

'' (百万塔陀羅尼, "1,000,000 towers/pagodas Darani").

The oldest extant evidence of woodblock prints created for the purpose of reading are portions of the

Lotus Sutra

The ''Lotus Sūtra'' ( zh, 妙法蓮華經; sa, सद्धर्मपुण्डरीकसूत्रम्, translit=Saddharma Puṇḍarīka Sūtram, lit=Sūtra on the White Lotus of the True Dharma, italic=) is one of the most influ ...

discovered at

Turpan

Turpan (also known as Turfan or Tulufan, , ug, تۇرپان) is a prefecture-level city located in the east of the autonomous region of Xinjiang, China. It has an area of and a population of 632,000 (2015).

Geonyms

The original name of the cit ...

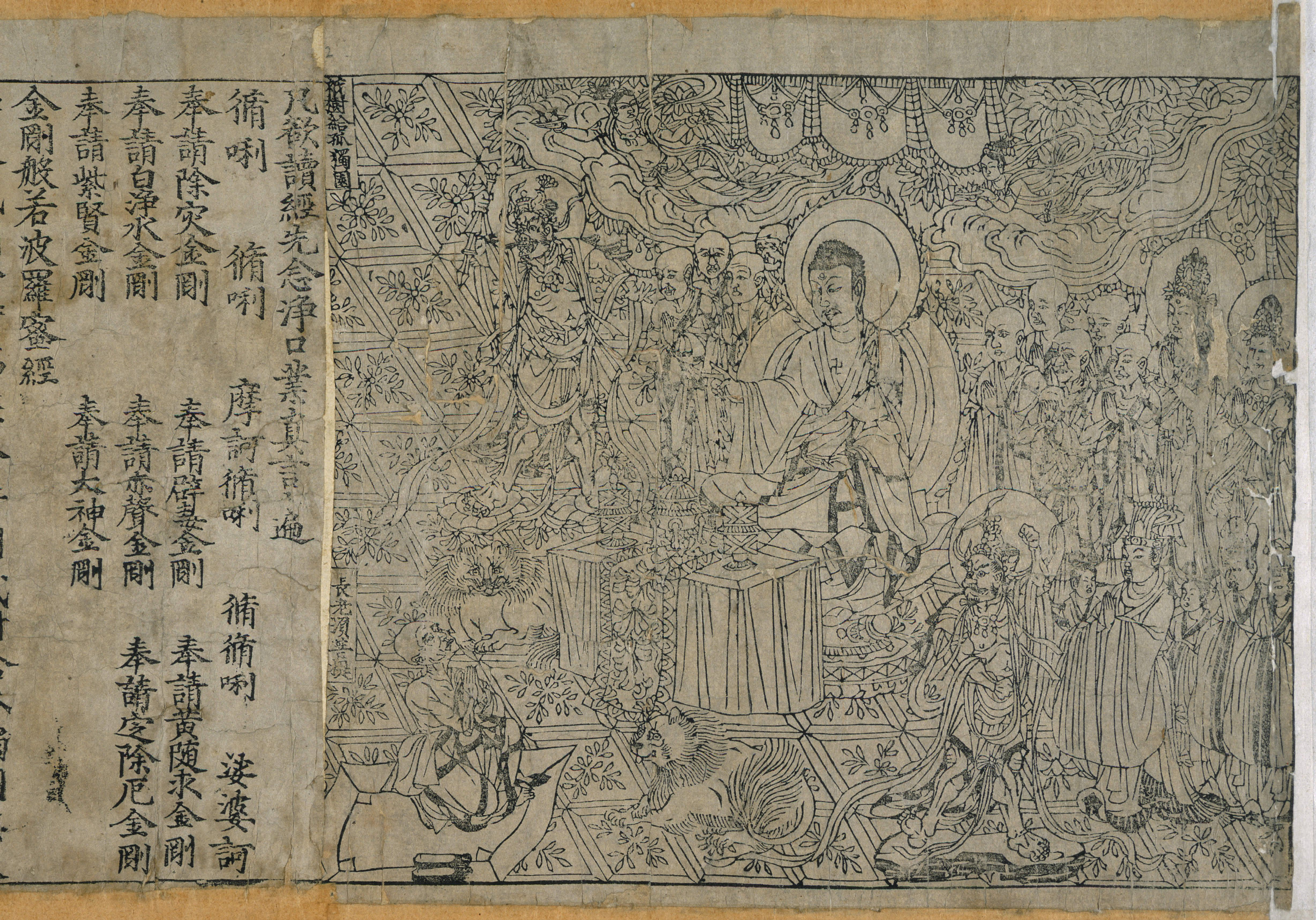

in 1906. They have been dated to the reign of Wu Zetian using character form recognition. The oldest text containing a specific date of printing was discovered in the

Mogao Caves

The Mogao Caves, also known as the Thousand Buddha Grottoes or Caves of the Thousand Buddhas, form a system of 500 temples southeast of the center of Dunhuang, an oasis located at a religious and cultural crossroads on the Silk Road, in Gansu p ...

of

Dunhuang

Dunhuang () is a county-level city in Northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027, though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800. Dunhuang was a major s ...

in 1907 by

Aurel Stein

Sir Marc Aurel Stein,

( hu, Stein Márk Aurél; 26 November 1862 – 26 October 1943) was a Hungarian-born British archaeologist, primarily known for his explorations and archaeological discoveries in Central Asia. He was also a professor at ...

. This copy of the

Diamond Sutra is 14 feet long and contains a

colophon at the inner end, which reads: ''Reverently

aused to bemade for universal free distribution by Wang Jie on behalf of his two parents on the 13th of the 4th moon of the 9th year of Xiantong

.e. 11 May, AD 868 '. It is considered the world's oldest securely-dated woodblock scroll. The Diamond sutra was closely followed by the earliest extant printed almanac, the ''Qianfu sinian lishu'' (乾符四年曆書), dated to 877. From 932 to 955 the

Twelve Classics and an assortment of other texts were printed. During the

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

, the Directorate of education and other agencies used these block prints to disseminate their standardized versions of the ''Classics''. Other disseminated works include the ''Histories'', philosophical works, encyclopedias, collections, and books on medicine and the art of war. In 971 work began on the complete

Tripiṭaka

''Tipiṭaka'' () or ''Tripiṭaka'' () or ''තිපිටක'' (), meaning "Triple Basket", is the traditional term for ancient collections of Buddhist sacred scriptures.

The Pāli Canon maintained by the Theravāda tradition in ...

Buddhist Canon (''Kaibao zangshu'' 開寶藏書) in

Chengdu

Chengdu (, ; simplified Chinese: 成都; pinyin: ''Chéngdū''; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: ), alternatively romanized as Chengtu, is a sub-provincial city which serves as the capital of the Chinese provin ...

. It took 10 years to finish the 130,000 blocks needed to print the text. The finished product, the

Sichuan

Sichuan (; zh, c=, labels=no, ; zh, p=Sìchuān; alternatively romanized as Szechuan or Szechwan; formerly also referred to as "West China" or "Western China" by Protestant missions) is a province in Southwest China occupying most of t ...

edition of the ''Kaibao canon'', also known as the ''Kaibao Tripitaka'', was printed in 983. During the Song dynasty, the three major centers of printing were

Hangzhou

Hangzhou ( or , ; , , Standard Chinese, Standard Mandarin pronunciation: ), also Chinese postal romanization, romanized as Hangchow, is the capital and most populous city of Zhejiang, China. It is located in the northwestern part of the prov ...

,

Jianyang, and

Chengdu

Chengdu (, ; simplified Chinese: 成都; pinyin: ''Chéngdū''; Sichuanese pronunciation: , Standard Chinese pronunciation: ), alternatively romanized as Chengtu, is a sub-provincial city which serves as the capital of the Chinese provin ...

.

In 989

Seongjong of Goryeo sent the monk Yeoga to request from the Song a copy of the complete Buddhist canon. The request was granted in 991 when Seongjong's official Han Eongong visited the Song court. In 1011,

Hyeonjong of Goryeo

Hyeonjong of Goryeo (1 August 992 – 17 June 1031, r. 1009–1031) was the 8th ruler of the Goryeo dynasty of Korea. He was a grandson of King Taejo. He was appointed by the military leader Gang Jo, whom the previous King Mokjong had calle ...

issued the carving of their own set of the Buddhist canon, which would come to be known as the ''

Goryeo Daejanggyeong''. The project was suspended in 1031 after Heyongjong's death, but work resumed again in 1046 after

Munjong's accession to the throne. The completed work, amounting to some 6,000 volumes, was finished in 1087. Unfortunately the original set of woodblocks was destroyed in a conflagration during the

Mongol invasion

The Mongol invasions and conquests took place during the 13th and 14th centuries, creating history's largest contiguous empire: the Mongol Empire (1206-1368), which by 1300 covered large parts of Eurasia. Historians regard the Mongol devastati ...

of 1232. King

Gojong ordered another set to be created and work began in 1237, this time only taking 12 years to complete. In 1248 the complete ''

Goryeo Daejanggyeong'' numbered 81,258 printing blocks, 52,330,152 characters, 1496 titles, and 6568 volumes. Due to the stringent editing process that went into the ''Goryeo Daejanggyeong'' and its surprisingly enduring nature, having survived completely intact over 760 years, it is considered the most accurate of Buddhist canons written in

Classical Chinese

Classical Chinese, also known as Literary Chinese (古文 ''gǔwén'' "ancient text", or 文言 ''wényán'' "text speak", meaning

"literary language/speech"; modern vernacular: 文言文 ''wényánwén'' "text speak text", meaning

"literar ...

as well as a standard edition for East Asian Buddhist scholarship.

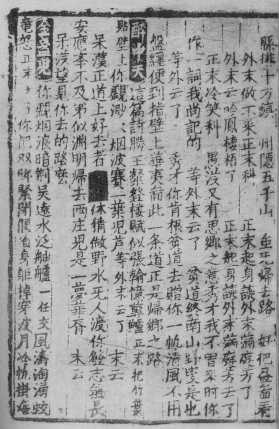

In Japan, from the

Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was character ...

in the 1600s, books and illustrations were mass-produced by woodblock printing and spread among the common people. This is due to economic development and a very high

literacy rate

Literacy in its broadest sense describes "particular ways of thinking about and doing reading and writing" with the purpose of understanding or expressing thoughts or ideas in written form in some specific context of use. In other words, huma ...

for the time. The literacy rate of the Japanese in the Edo period was almost 100% for the

samurai

were the hereditary military nobility and officer caste of medieval and early-modern Japan from the late 12th century until their abolition in 1876. They were the well-paid retainers of the '' daimyo'' (the great feudal landholders). They ...

class and 50% to 60% for the ''

chōnin

was a social class that emerged in Japan during the early years of the Tokugawa period. In the social hierarchy, it was considered subordinate to the samurai warrior class.

Social Class

The ''chōnin'' emerged in ''joka-machi'' or castle ...

'' and ''nōmin'' (farmer) class due to the spread of private schools ''

terakoya''. There were more than 600 rental bookstores in

Edo

Edo ( ja, , , "bay-entrance" or "estuary"), also romanized as Jedo, Yedo or Yeddo, is the former name of Tokyo.

Edo, formerly a ''jōkamachi'' (castle town) centered on Edo Castle located in Musashi Province, became the ''de facto'' capital of ...

, and people lent woodblock-printed illustrated books of various genres. The content of these books varied widely, including travel guides, gardening books, cookbooks, ''

kibyōshi'' (satirical novels), ''

sharebon'' (books on urban culture), ''

kokkeibon'' (comical books), ''

ninjōbon The is a pre-modern Japanese literary genre. Founded and developed in the early nineteenth century, this style of books derived from the early sharebon and kokkeibon genres and is a subgenre of gesaku. ''Ninjōbon'' was one of many genres in th ...

'' (romance novel), ''

yomihon

is a type of Japanese book from the Edo period (1603–1867). Unlike other Japanese books of the periods, such as kusazōshi, they had few illustrations, and the emphasis was on the text. In storylines, Buddhist ethics such as karma are often pre ...

'', ''

kusazōshi'', art books, play scripts for the kabuki and ''

jōruri'' (puppet) theatre, etc. The best-selling books of this period were ''Kōshoku Ichidai Otoko (Life of an Amorous Man)'' by

Ihara Saikaku

was a Japanese poet and creator of the " floating world" genre of Japanese prose (''ukiyo-zōshi'').

Born as Hirayama Tōgo (平山藤五), the son of a wealthy merchant in Osaka, he first studied haikai poetry under Matsunaga Teitoku and lat ...

, ''

Nansō Satomi Hakkenden'' by

Takizawa Bakin, and ''

Tōkaidōchū Hizakurige'' by

Jippensha Ikku

was the pen name of Shigeta Sadakazu (重田 貞一), a Japanese writer active during the late Edo period of Japan. He was among the most prolific writers of the late Edo period — between 1795 and 1801 he wrote a minimum of twenty novels ...

, and these books were reprinted many times.

[The Past, Present and Future of Printing in Japan.](_blank)

Izumi Munemura. (2010). The Surface Finishing Society of Japan.

National Diet Library.

From the 17th century to the 19th century, ''

ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e is a genre of Japanese art which flourished from the 17th through 19th centuries. Its artists produced woodblock prints and paintings of such subjects as female beauties; kabuki actors and sumo wrestlers; scenes from history and folk ta ...

'' depicting secular subjects became very popular among the Japanese common people and were mass-produced. ''ukiyo-e'' is based on

kabuki

is a classical form of Japanese dance- drama. Kabuki theatre is known for its heavily-stylised performances, the often-glamorous costumes worn by performers, and for the elaborate make-up worn by some of its performers.

Kabuki is thought ...

actors,

sumo

is a form of competitive full-contact wrestling where a '' rikishi'' (wrestler) attempts to force his opponent out of a circular ring ('' dohyō'') or into touching the ground with any body part other than the soles of his feet (usually by t ...

wrestlers, beautiful women, landscapes of sightseeing spots, historical tales, and so on, and

Hokusai

, known simply as Hokusai, was a Japanese ukiyo-e artist of the Edo period, active as a painter and printmaker. He is best known for the woodblock print series '' Thirty-Six Views of Mount Fuji'', which includes the iconic print ''The Great W ...

and

Hiroshige

Utagawa Hiroshige (, also ; ja, 歌川 広重 ), born Andō Tokutarō (; 1797 – 12 October 1858), was a Japanese ''ukiyo-e'' artist, considered the last great master of that tradition.

Hiroshige is best known for his horizontal-format l ...

are the most famous artists. In the 18th century,

Suzuki Harunobu

Suzuki Harunobu ( ja, 鈴木 春信; ) was a Japanese designer of woodblock print art in the style. He was an innovator, the first to produce full-color prints () in 1765, rendering obsolete the former modes of two- and three-color prints. Haru ...

established the technique of multicolor woodblock printing called ''

nishiki-e'' and greatly developed Japanese woodblock printing culture such as ''ukiyo-e''. ''Ukiyo-e'' influenced European

Japonism

''Japonisme'' is a French term that refers to the popularity and influence of Japanese art and design among a number of Western European artists in the nineteenth century following the forced reopening of foreign trade with Japan in 1858. Japon ...

and

Impressionism

Impressionism was a 19th-century art movement characterized by relatively small, thin, yet visible brush strokes, open composition, emphasis on accurate depiction of light in its changing qualities (often accentuating the effects of the passa ...

. In the early 20th century, ''

shin-hanga

was an art movement in early 20th-century Japan, during the Taishō and Shōwa periods, that revitalized the traditional ''ukiyo-e'' art rooted in the Edo and Meiji periods (17th–19th century). It maintained the traditional ''ukiyo-e'' c ...

'' that fused the tradition of ''ukiyo-e'' with the techniques of Western paintings became popular, and the works of

Hasui Kawase

was an artist, one of modern Japan's most important and prolific printmakers. He was a prominent designer of the '' shin-hanga'' ("new prints") movement, whose artists depicted traditional subjects with a style influenced by Western art. Like ma ...

and

Hiroshi Yoshida gained international popularity.

Impact of woodblock printing

Prior to the introduction of printing, the size of private collections in China had already seen an increase since the invention of paper. Fan Ping (215–84) had in his collection 7,000 rolls (''juan''), or a few hundred titles. Two centuries later, Zhang Mian owned 10,000 ''juan'',

Shen Yue

Shen Yue (; 441–1 May 513), courtesy name Xiuwen (休文), was a Chinese historian, music theorist, poet, and politician born in Huzhou, Zhejiang. He served emperors under the Liu Song Dynasty, the Southern Qi Dynasty (see Yongming poetry), a ...

(441–513) 20,000 ''juan'', and

Xiao Tong and his cousin Xiao Mai both had collections of 30,000 ''juan''.

Emperor Yuan of Liang

Emperor Yuan of Liang () (16 September 508 – 27 January 555), personal name Xiao Yi (), courtesy name Shicheng (), childhood name Qifu (), was an emperor of the Chinese Liang Dynasty. After his father Emperor Wu and brother Emperor Jianwen w ...

(508–555) was said to have had a collection of 80,000 ''juan''. The combined total of all known private book collectors prior to the Song dynasty number around 200, with the Tang alone accounting for 60 of them.

Following the maturation of woodblock printing, official, commercial, and private publishing businesses emerged while the size and number of collections grew exponentially. The Song dynasty alone accounts for some 700 known private collections, more than triple the number of all the preceding centuries combined. Private libraries of 10–20,000 ''juan'' became commonplace while six individuals owned collections of over 30,000 ''juan''. The earliest extant private Song library catalogue lists 1,937 titles in 24,501 ''juan''. Zhou Mi's collection numbered 42,000 ''juan'', Chen Zhensun's collection lists 3,096 titles in 51,180 ''juan'', and

Ye Mengde (1077–1148) as well as one other individual owned libraries of 6,000 titles in 100,000 ''juan''. The majority of which were secular in nature. Texts contained material such as medicinal instruction or came in the form of a ''

leishu

The ''leishu'' () is a genre of reference books historically compiled in China and other East Asian countries. The term is generally translated as "encyclopedia", although the ''leishu'' are quite different from the modern notion of encycloped ...

'' (類書), a type of encyclopedic reference book used to help

examination candidates.

Imperial establishments such as the Three Institutes: Zhaowen Institute, History Institute, and Jixian Institute also followed suit. At the start of the dynasty the Three Institutes' holdings numbered 13,000 ''juan'', by the year 1023 39,142 ''juan'', by 1068 47,588 ''juan'', and by 1127 73,877 ''juan''. The Three Institutes were one of several imperial libraries, with eight other major palace libraries, not including imperial academies. According to Weng Tongwen, by the 11th century, central government offices were saving tenfold by substituting earlier manuscripts with printed versions. The impact of woodblock printing on Song society is illustrated in the following exchange between

Emperor Zhenzong

Emperor Zhenzong of Song (23 December 968 – 23 March 1022), personal name Zhao Heng, was the third emperor of the Song dynasty of China. He reigned from 997 to his death in 1022. His personal name was originally Zhao Dechang, but was change ...

and Xing Bing in the year 1005:

In 1076, the 39 year old

Su Shi

Su Shi (; 8 January 1037 – 24 August 1101), courtesy name Zizhan (), art name Dongpo (), was a Chinese calligrapher, essayist, gastronomer, pharmacologist, poet, politician, and travel writer during the Song dynasty. A major personality of ...

remarked upon the unforeseen effect an abundance of books had on examination candidates:

Woodblock printing also changed the shape and structure of books. Scrolls were gradually replaced by concertina binding (經摺裝) from the Tang period onward. The advantage was that it was now possible to flip to a reference without unfolding the entire document. The next development known as whirlwind binding (''xuanfeng zhuang'' 旋風裝) was to secure the first and last leaves to a single large sheet, so that the book could be opened like an accordion.

Around the year 1000, butterfly binding was developed. Woodblock prints allowed two mirror images to be easily replicated on a single sheet. Thus two pages were printed on a sheet, which was then folded inwards. The sheets were then pasted together at the fold to make a

codex

The codex (plural codices ) was the historical ancestor of the modern book. Instead of being composed of sheets of paper, it used sheets of vellum, papyrus, or other materials. The term ''codex'' is often used for ancient manuscript books, with ...

with alternate openings of printed and blank pairs of pages. In the 14th century the folding was reversed outwards to give continuous printed pages, each backed by a blank hidden page. Later the sewn bindings were preferred rather than pasted bindings. Only relatively small volumes (''

juan 卷'') were bound up, and several of these would be enclosed in a cover called a ''tao'', with wooden boards at front and back, and loops and pegs to close up the book when not in use. For example, one complete Tripitaka had over 6,400 ''juan'' in 595 ''tao''.

The rise of woodblock printing technology led to a decline in book prices by about one tenth what they had been before the 11th century. Not all areas experienced the same price reductions, which was also dependent on other factors besides the technology, resulting in regional variations in the price of print works by as high as 600 percent during the 12th century. Woodblock printing did not replace manuscripts either, which continued to remain commercially viable through substantially reducing their prices. According to the

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

author

Hu Yinglin

Hu Yinglin (; 1551–1602), also known as Hu Yuanrui, was a Chinese scholar, writer and bibliophile during the late Ming dynasty. A native of Lanxi, he produced over 1,000 works of scholarship. His two most noted works are the ''Shaoshishan fang ...

, "if no printed edition were available on the market, the hand-copied manuscript of a book would cost ten times as much as the printed work," also "once a printed edition appeared, the transcribed copy could no longer be sold and would be discarded." The result is that despite the mutual co-existence of hand-copied manuscripts and printed texts, the cost of the book had declined by about 90 percent by the end of the 16th century. As a result, literacy increased. In 1488, the

Korean Choe Bu observed during his trip to China that "even village children, ferrymen, and sailors" could read, although this applied mainly to the south while northern China remained largely illiterate. Manuscripts also gained new cultural value as imprints became more common, and were even ''preferred'' by elite scholars and collectors. The age of printing gave the act of copying by hand a new dimension of cultural reverence. Those who considered themselves real scholars and true connoisseurs of the book did not consider imprints to be real books. Under the elitist attitudes of the time, "printed books were for those who did not truly care about books."

In India

In Buddhism, great merit is thought to accrue from copying and preserving texts.

Asanga

Asaṅga (, ; Romaji: ''Mujaku'') (fl. 4th century C.E.) was "one of the most important spiritual figures" of Mahayana Buddhism and the "founder of the Yogachara school".Engle, Artemus (translator), Asanga, ''The Bodhisattva Path to Unsurpasse ...

, the 4th-century master listed the copying of scripture as the first of ten essential religious practices. The importance of perpetuating texts is set out with special force in the

longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra

The ''Longer Sukhāvatīvyūha Sūtra'' (or ''Infinite Life Sutra'', Chinese: ''Fóshuōwúliàngshòujīng'' 佛說無量壽經; Vietnamese: Phật Thuyết Kinh Vô Lượng Thọ; Japanese: Taisho Tripitaka # 360) is one of the two Indian ...

, which urges the devout not only to hear, learn, remember and study the text but to obtain a good copy and to preserve it. This "cult of the book" led to techniques for reproducing texts in great numbers, especially the short prayers or charms known as ''dhāraṇīs''. Stamps were carved for printing these prayers on clay tablets from at least the 7th century, the date of the oldest surviving examples.

In the Islamic world

The

Golden Age of Islam

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

witnessed text printing, including passages from the

Quran

The Quran (, ; Standard Arabic: , Quranic Arabic: , , 'the recitation'), also romanized Qur'an or Koran, is the central religious text of Islam, believed by Muslims to be a revelation from God. It is organized in 114 chapters (pl.: , ...

and

hadith

Ḥadīth ( or ; ar, حديث, , , , , , , literally "talk" or "discourse") or Athar ( ar, أثر, , literally "remnant"/"effect") refers to what the majority of Muslims believe to be a record of the words, actions, and the silent approva ...

, embracing the Chinese craft of paper making, developed it and adopted it widely in the

Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

, which led to a major increase in the production of manuscript texts. The printing technique in

Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a List of transcontinental countries, transcontinental country spanning the North Africa, northeast corner of Africa and Western Asia, southwest corner of Asia via a land bridg ...

was adopted reproducing texts on paper strips and supplying them in various copies to meet the demand.

Block printing, known as ''

tarsh

In post-classical Arabic, a ''ṭarsh'' (طرش) is an engraved block used for printing. They were made of wood or tin and were in use from the ninth or tenth century until at least the fourteenth. There are over a hundred known Arabic blockprin ...

'' in

Arabic

Arabic (, ' ; , ' or ) is a Semitic language spoken primarily across the Arab world.Semitic languages: an international handbook / edited by Stefan Weninger; in collaboration with Geoffrey Khan, Michael P. Streck, Janet C. E.Watson; Walter ...

, was also developed during the ninth and tenth centuries, mostly for prayers and

amulet

An amulet, also known as a good luck charm or phylactery, is an object believed to confer protection upon its possessor. The word "amulet" comes from the Latin word amuletum, which Pliny's ''Natural History'' describes as "an object that protect ...

s. Evidences tell that the print blocks made from non-wood materials, possibly

tin, lead, or clay. Europe adopted woodblock printing from the Islamic world, at first for fabric, the method of metal block printing remained unknown in the West. Block printing later went out of use in the Muslim

Timurid Renaissance

The Timurid Renaissance was a historical period in Asian and Islamic history spanning the late 14th, the 15th, and the early 16th centuries. Following the gradual downturn of the Islamic Golden Age, the Timurid Empire, based in Central Asia rul ...

.

In Europe

Printing with a press was practiced in Christian Europe as a method for printing on cloth, where it was common by 1300. Images printed on cloth for religious purposes could be quite large and elaborate, and when

paper

Paper is a thin sheet material produced by mechanically or chemically processing cellulose fibres derived from wood, rags, grasses or other vegetable sources in water, draining the water through fine mesh leaving the fibre evenly distribu ...

became relatively easily available, around 1400, the medium transferred very quickly to small

woodcut

Woodcut is a relief printing technique in printmaking. An artist carves an image into the surface of a block of wood—typically with gouges—leaving the printing parts level with the surface while removing the non-printing parts. Areas tha ...

religious images and

playing cards

A playing card is a piece of specially prepared card stock, heavy paper, thin cardboard, plastic-coated paper, cotton-paper blend, or thin plastic that is marked with distinguishing motifs. Often the front (face) and back of each card has a f ...

printed on paper. These

prints

In molecular biology, the PRINTS database is a collection of so-called "fingerprints": it provides both a detailed annotation resource for protein families, and a diagnostic tool for newly determined sequences. A fingerprint is a group of conserved ...

were produced in very large numbers from about 1425 onwards.

[An Introduction to a History of Woodcut, Arthur M. Hind, p ?, Houghton Mifflin Co. 1935 (in USA), reprinted Dover Publications, 1963 ]

Around the mid-century, ''block-books'', woodcut books with both text and images, usually carved in the same block, emerged as a cheaper alternative to manuscripts and books printed with

movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation m ...

. These were all short heavily illustrated works, the bestsellers of the day, repeated in many different block-book versions: the

Ars moriendi

The ''Ars moriendi'' ("The Art of Dying") are two related Latin texts dating from about 1415 and 1450 which offer advice on the protocols and procedures of a good death, explaining how to "die well" according to Christian precepts of the late M ...

and the

Biblia pauperum were the most common. There is still some controversy among scholars as to whether their introduction preceded or, the majority view, followed the introduction of movable type, with the range of estimated dates being between about 1440–1460.

[Master E.S., Alan Shestack, Philadelphia Museum of Art, 1967]

Movable type (1041)

Movable type is the system of

printing

Printing is a process for mass reproducing text and images using a master form or template. The earliest non-paper products involving printing include cylinder seals and objects such as the Cyrus Cylinder and the Cylinders of Nabonidus. The ...

and

typography

Typography is the art and technique of arranging type to make written language legible, readable and appealing when displayed. The arrangement of type involves selecting typefaces, point sizes, line lengths, line-spacing ( leading), an ...

using individual pieces of type.

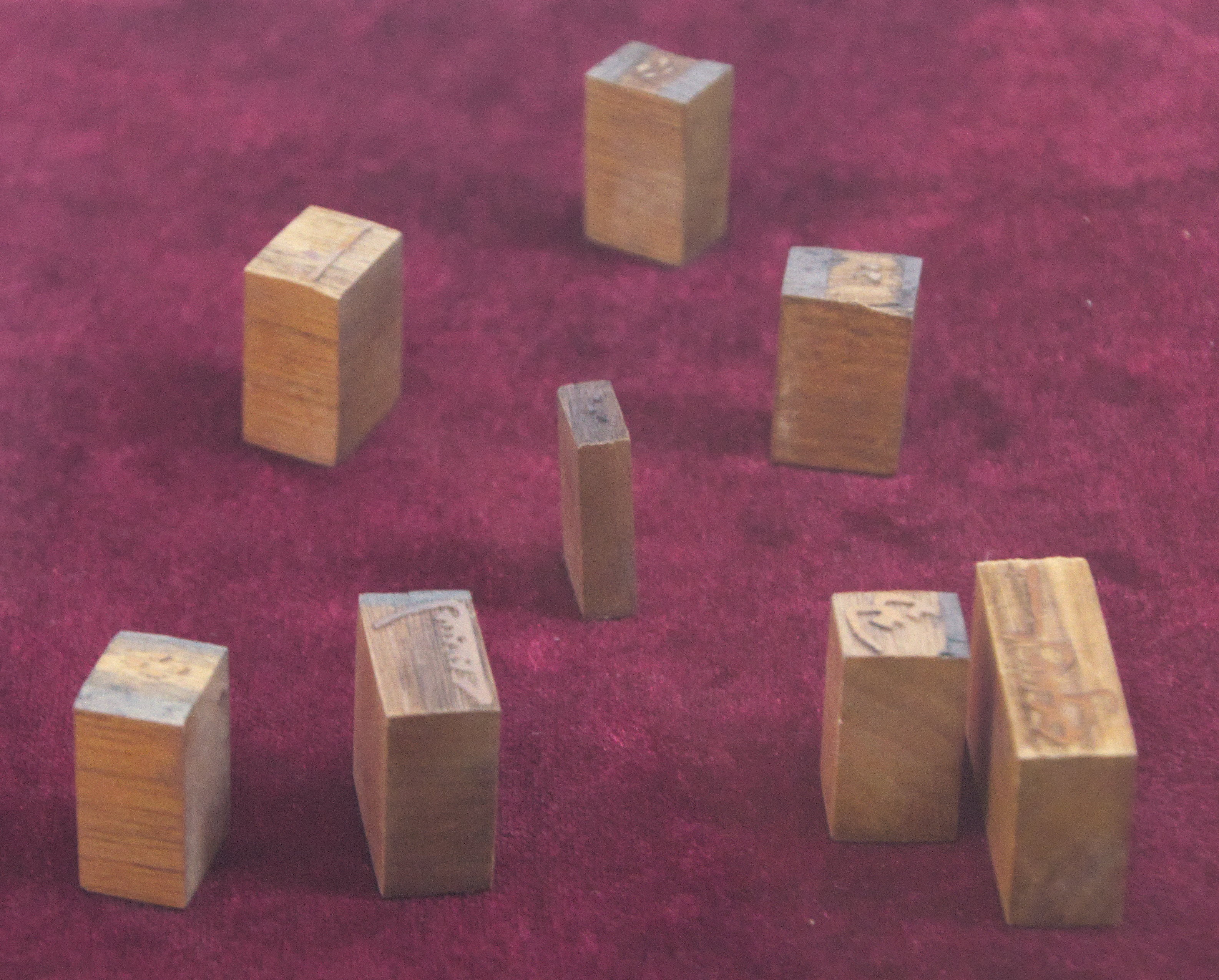

Ceramic movable type

Movable type was invented in the

Northern Song dynasty

Northern may refer to the following:

Geography

* North, a point in direction

* Northern Europe, the northern part or region of Europe

* Northern Highland, a region of Wisconsin, United States

* Northern Province, Sri Lanka

* Northern Range, a ...

around the year 1041 by the commoner

Bi Sheng

Bi Sheng (; 972–1051 AD) was a Chinese artisan, engineer, and inventor of the world's first movable type technology, with printing being one of the Four Great Inventions. Bi Sheng's system was made of Chinese porcelain and was invented betwe ...

. Bi Sheng's movable type was fired in

porcelain

Porcelain () is a ceramic material made by heating substances, generally including materials such as kaolinite, in a kiln to temperatures between . The strength and translucence of porcelain, relative to other types of pottery, arises main ...

. After his death, the ceramic movable-type passed onto his descendants. The next mention of movable type occurred in 1193 when a Southern Song chief counselor, Zhou Bida (周必大), attributed the movable-type method of printing to

Shen Kuo

Shen Kuo (; 1031–1095) or Shen Gua, courtesy name Cunzhong (存中) and pseudonym Mengqi (now usually given as Mengxi) Weng (夢溪翁),Yao (2003), 544. was a Chinese polymathic scientist and statesman of the Song dynasty (960–1279). Shen wa ...

. However Shen Kuo did not invent the movable type but credited it to Bi Sheng in his ''

Dream Pool Essays

''The Dream Pool Essays'' (or ''Dream Torrent Essays'') was an extensive book written by the Chinese polymath and statesman Shen Kuo (1031–1095), published in 1088 during the Song dynasty (960–1279) of China. Shen compiled this encycloped ...

''. The ceramic movable type was also mentioned by

Kublai Khan

Kublai ; Mongolian script: ; (23 September 1215 – 18 February 1294), also known by his temple name as the Emperor Shizu of Yuan and his regnal name Setsen Khan, was the founder of the Yuan dynasty of China and the fifth khagan-emperor of ...

's councilor

Yao Shu Yao Shu (姚璹) (632–705), courtesy name Lingzhang (令璋), formally Count Cheng of Wuxing (吳興成伯), was a Chinese politician of the Tang and Wu Zetian's Zhou Dynasty, serving twice as chancellor during Wu Zetian's reign.

He is not to be ...

, who convinced his pupil

Yang Gu to print language primers using this method.

The ceramic type did not hold the water-based Chinese calligraphic ink well, and had the additional disadvantage of the size of the type sometimes changing during the baking process, resulting in uneven matching of the type, and preventing it from becoming popular.

Wooden movable type

Bi Sheng also developed

wooden movable type, but it was abandoned in favor of ceramic types due to the presence of wood grains and the unevenness of the wooden type after being soaked in ink. However wooden movable type had evidently reached the

Tangut Western Xia

The Western Xia or the Xi Xia (), officially the Great Xia (), also known as the Tangut Empire, and known as ''Mi-nyak''Stein (1972), pp. 70–71. to the Tanguts and Tibetans, was a Tangut-led Buddhist imperial dynasty of China tha ...

to the west by the 12th century. There, the Tanguts printed the

Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union

The ''Auspicious Tantra of All-Reaching Union'' ( Tangut: ''Gyu̱²-rjur¹ Źji²-njɨ² Ngwu²-phjo̱² Mər²-twẹ²'', translated into Chinese as ''Jíxiáng Biànzhì Kǒuhé Běnxù'' 吉祥遍至口和本續) is the title of a set of nin ...

, a 449-page text considered to be the earliest extant example of a text printed using the wooden movable type.

The

Uyghurs

The Uyghurs; ; ; ; zh, s=, t=, p=Wéiwú'ěr, IPA: ( ), alternatively spelled Uighurs, Uygurs or Uigurs, are a Turkic peoples, Turkic ethnic group originating from and culturally affiliated with the general region of Central Asia, Cent ...

too seem to have used wooden movable type although it is unknown where they got the technology. In 1908, more than a thousand pieces of Uyghur type made of wood, engraved in

Sogdian script, were discovered in

Dunhuang

Dunhuang () is a county-level city in Northwestern Gansu Province, Western China. According to the 2010 Chinese census, the city has a population of 186,027, though 2019 estimates put the city's population at about 191,800. Dunhuang was a major s ...

. They are believed to date to the 12th century when the Uyghurs also made use of woodblock printing. To date no manuscripts or fragments of Uyghur movable type have been found.

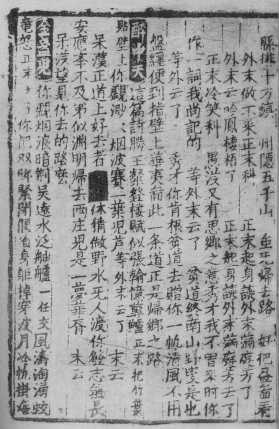

Wang Zhen, who lived in the

Yuan dynasty

The Yuan dynasty (), officially the Great Yuan (; xng, , , literally "Great Yuan State"), was a Mongol-led imperial dynasty of China and a successor state to the Mongol Empire after its division. It was established by Kublai, the fif ...

, also described the wooden movable type in his ''Book of Agriculture'' (''Nongshu'' 農書) of 1313.

Wang Zhen used two rotating circular tables as trays for laying out his type. The first table was separated into 24 trays in which each movable type was categorized based on a number corresponding with a rhyming pattern. The second table contained miscellaneous characters.

Using more than 30,000 wooden movable types, Wang Zhen printed a hundred copies of his county gazetteer, ''Records of Jingde County'' (''Jingde xianzhi'' 旌德縣志), a text containing more than 60,000 characters.

Wooden movable type printing became relatively common during the

Ming dynasty

The Ming dynasty (), officially the Great Ming, was an Dynasties in Chinese history, imperial dynasty of China, ruling from 1368 to 1644 following the collapse of the Mongol Empire, Mongol-led Yuan dynasty. The Ming dynasty was the last ort ...

and became widespread during the

Qing era.

Metal movable type

Metal movable type appeared in the late Song and Yuan dynasties. Bronze movable types were used to print

banknotes

A banknote—also called a bill (North American English), paper money, or simply a note—is a type of negotiable promissory note, made by a bank or other licensed authority, payable to the bearer on demand.

Banknotes were originally issued ...

and official documents by both the Song and

Jin.

In the Jin dynasty, copper-block prints were slotted with two square holes for embedding bronze movable type characters, each selected from 1000 different characters, such that each printed paper money had a different combination of markers. A copper block printed paper banknote dated between 1215 and 1216 in the collection of

Luo Zhenyu

Luo Zhenyu or Lo Chen-yü (August 8, 1866 – May 14, 1940), courtesy name Shuyun (叔蘊), was a Chinese classical scholar, philologist, epigrapher, antiquarian and Qing loyalist.

Biography

A native of Huai'an, Luo began to publish works o ...

's ''Pictorial Paper Money of the Four Dynasties'', 1914, shows two special characters: one called ''Ziliao'', the other called ''Zihao'', for the purpose of preventing counterfeit. Over the ''Ziliao'' there is a small character (輶) printed with movable copper type, while over the ''Zihao'' there is an empty square hole; apparently the associated copper metal type was lost. Another sample of

Song dynasty

The Song dynasty (; ; 960–1279) was an imperial dynasty of China that began in 960 and lasted until 1279. The dynasty was founded by Emperor Taizu of Song following his usurpation of the throne of the Later Zhou. The Song conquered the res ...

money of the same period in the collection of

Shanghai Museum

The Shanghai Museum is a museum of ancient Chinese art, situated on the People's Square in the Huangpu District of Shanghai, China. Rebuilt at its current location in 1996, it is considered one of China's first world-class modern museums and fa ...

has two empty square holes above ''Ziliao'' as well as ''Zihou'', due to the loss of two copper movable types.

In 1234, cast metal movable type was used in

Goryeo

Goryeo (; ) was a Korean kingdom founded in 918, during a time of national division called the Later Three Kingdoms period, that unified and ruled the Korean Peninsula until 1392. Goryeo achieved what has been called a "true national unificat ...

(Korea) to print the 50-volume ''Prescribed Texts for Rites of the Past and Present'', compiled by

Choe Yun-ui

Choe Yun-ui was a Korean politician, publisher, and writer during the Goryeo Dynasty. Choe Yun-ui compiled the ''Sangjeong Gogeum Yemun'' (Hangul : 상정예문, hanja : 詳定禮文) with another 16 scholars. They collected all courtesies from ...

, but no copies survived to the present. Choe Yun-ui built on an earlier Chinese method of creating movable type, he adapted a method for minting bronze coins to cast 3-dimensional characters in metal. Because of the length of the text Choe Yun-ui did not complete the project until 1250. The oldest extant book printed with movable metal type is the

Jikji of 1377. This form of metal movable type was described by the French scholar Henri-Jean Martin as "extremely similar to Gutenberg's".

Tin movable type is mentioned in Wang Zhen's ''Zao Huozi Yinshufa'' (造活字印書法) of 1298, but it was considered unsatisfactory due to incompatibility with the inking process. Only in the late 15th century did bronze movable type begin to be widely used in China.

Impact of movable type in the Sinosphere

Movable type printing was hardly used for the first 300 years after its invention by Bi Sheng. Even in Korea where metal movable type was most widespread, it still never replaced woodblock printing. Indeed, even the promulgation of

Hangeul was done through woodblock prints. The general assumption is that movable type did not replace block printing in places that used Chinese characters due to the expense of producing more than 200,000 individual pieces of type. Even woodblock printing was not as cost productive as simply paying a copyist to write out a book by hand if there was no intention of producing more than a few copies. Although

Sejong the Great

Sejong of Joseon (15 May 1397 – 8 April 1450), personal name Yi Do (Korean: 이도; Hanja: 李祹), widely known as Sejong the Great (Korean: 세종대왕; Hanja: 世宗大王), was the fourth ruler of the Joseon dynasty of Korea. Initial ...

introduced Hangeul, an alphabetic system, in the 15th century, Hangeul only replaced

Hanja

Hanja (Hangul: ; Hanja: , ), alternatively known as Hancha, are Chinese characters () used in the writing of Korean. Hanja was used as early as the Gojoseon period, the first ever Korean kingdom.

(, ) refers to Sino-Korean vocabulary, ...

in the 20th century. And unlike China, the movable type system was kept mainly within the confines of a highly stratified elite Korean society:

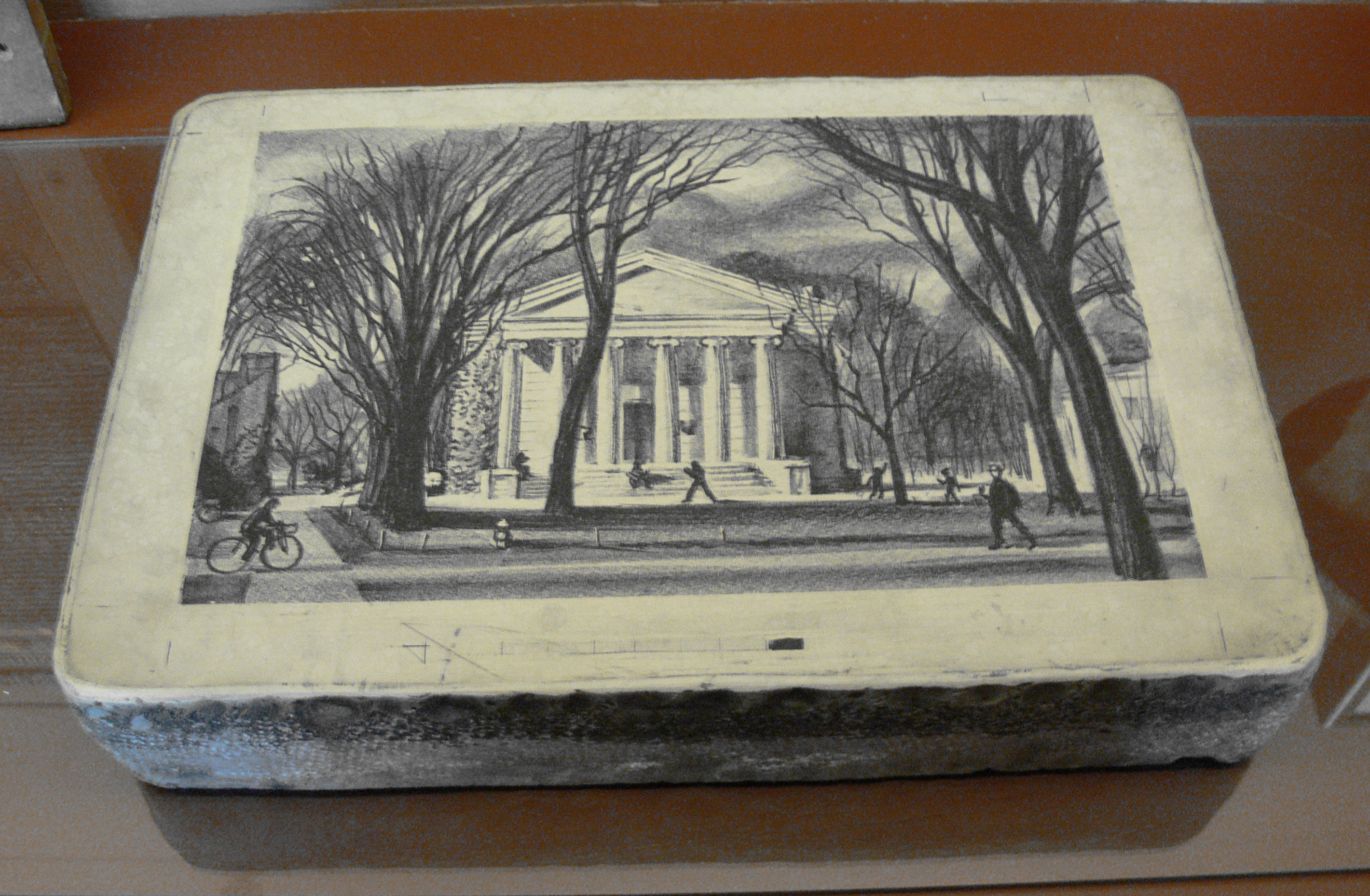

Only during the Ming and Qing dynasties did wooden and metal movable types see any considerable use, but the preferred method remained woodblock. Usage of movable type in China never exceeded 10 percent of all printed materials while 90 percent of printed books used the older woodblock technology. In one case an entire set of wooden type numbering 250,000 pieces was used for firewood. Woodblocks remained the dominant printing method in China until the introduction of

lithography

Lithography () is a planographic method of printing originally based on the immiscibility of oil and water. The printing is from a stone (lithographic limestone) or a metal plate with a smooth surface. It was invented in 1796 by the German a ...

in the late 19th century.

In Japan the first Western style

movable type

Movable type (US English; moveable type in British English) is the system and technology of printing and typography that uses movable components to reproduce the elements of a document (usually individual alphanumeric characters or punctuation m ...

printing-press was brought to Japan by

Tenshō embassy

The Tenshō embassy (Japanese: 天正の使節, named after the Tenshō Era in which the embassy took place) was an embassy sent by the Japanese Christian Lord Ōtomo Sōrin to the Pope and the kings of Europe in 1582. The embassy was led by ...

in 1590, and was first printed in

Kazusa, Nagasaki in 1591. However, western printing-press were discontinued after the ban on Christianity in 1614.

The moveable type printing-press seized from Korea by

Toyotomi Hideyoshi

, otherwise known as and , was a Japanese samurai and ''daimyō'' (feudal lord) of the late Sengoku period regarded as the second "Great Unifier" of Japan.Richard Holmes, The World Atlas of Warfare: Military Innovations that Changed the Cour ...

's forces in 1593 was also in use at the same time as the printing press from Europe. An edition of the

Confucian

Confucianism, also known as Ruism or Ru classicism, is a system of thought and behavior originating in ancient China. Variously described as tradition, a philosophy, a religion, a humanistic or rationalistic religion, a way of governing, or ...

''

Analects

The ''Analects'' (; ; Old Chinese: '' ŋ(r)aʔ''; meaning "Selected Sayings"), also known as the ''Analects of Confucius'', the ''Sayings of Confucius'', or the ''Lun Yu'', is an ancient Chinese book composed of a large collection of sayings a ...

'' was printed in 1598, using a Korean moveable type printing press, at the order of

Emperor Go-Yōzei

was the 107th Emperor of Japan, according to the traditional order of succession. Go-Yōzei's reign spanned the years 1586 through to his abdication in 1611, corresponding to the transition between the Azuchi–Momoyama period and the Edo period ...

.

Tokugawa Ieyasu

was the founder and first ''shōgun'' of the Tokugawa Shogunate of Japan, which ruled Japan from 1603 until the Meiji Restoration in 1868. He was one of the three "Great Unifiers" of Japan, along with his former lord Oda Nobunaga and fello ...

established a printing school at

Enko-ji in Kyoto and started publishing books using domestic wooden movable type printing-press instead of metal from 1599. Ieyasu supervised the production of 100,000 types, which were used to print many political and historical books. In 1605, books using domestic copper movable type printing-press began to be published, but copper type did not become mainstream after Ieyasu died in 1616.

Despite the appeal of moveable type, however, craftsmen soon decided that the

running script style of Japanese writings was better reproduced using woodblocks. By 1640 woodblocks were once again used for nearly all purposes. After the 1640s, movable type printing declined, and books were mass-produced by conventional woodblock printing during most of the

Edo period

The or is the period between 1603 and 1867 in the history of Japan, when Japan was under the rule of the Tokugawa shogunate and the country's 300 regional '' daimyo''. Emerging from the chaos of the Sengoku period, the Edo period was character ...

. It was after the 1870s, during the

Meiji period

The is an era of Japanese history that extended from October 23, 1868 to July 30, 1912.

The Meiji era was the first half of the Empire of Japan, when the Japanese people moved from being an isolated feudal society at risk of colonization ...

, when Japan opened the country to the West and began to modernize, that this technique was used again.

Movable type vs. woodblock printing

Traditionally it has been assumed that the prevalence of woodblock printing in East Asia as a result of Chinese characters led to the stagnation of printing culture and enterprise in that region. S. H. Steinberg describes woodblock printing in his ''Five Hundred Years of Printing'' as having "outlived their usefulness" and their printed material as "cheap tracts for the half-literate,

..which anyway had to be very brief because of the laborious process of cutting the letters." John Man's ''The Gutenberg Revolution'' makes a similar case: "wood-blocks were even more demanding than manuscript pages to make, and they wore out and broke, and then you had to carve another one – a whole page at a time."

Recent commentaries on printing in China using contemporary European observers with first hand knowledge complicate the traditional narrative. T. H. Barrett points out that only Europeans who had never seen Chinese woodblock printing in action tended to dismiss it, perhaps due to the almost instantaneous arrival of both xylography and movable type in Europe. The early Jesuit missionaries of late 16th century China, for instance, had a similar distaste for wood based printing for very different reasons. These Jesuits found that "the cheapness and omnipresence of printing in China made the prevailing wood-based technology extremely disturbing, even dangerous."

Matteo Ricci

Matteo Ricci, SJ (; la, Mattheus Riccius; 6 October 1552 – 11 May 1610), was an Italian Jesuit priest and one of the founding figures of the Jesuit China missions. He created the , a 1602 map of the world written in Chinese characters. ...

made note of "the exceedingly large numbers of books in circulation here and the ridiculously low prices at which they are sold." Two hundred years later the Englishman John Barrow, by way of the

Macartney mission to Qing China, also remarked with some amazement that the printing industry was "as free as in England, and the profession of printing open to everyone." The commercial success and profitability of woodblock printing was attested to by one British observer at the end of the nineteenth century, who noted that even before the arrival of western printing methods, the price of books and printed materials in

China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's List of countries and dependencies by population, most populous country, with a Population of China, population exceeding 1.4 billion, slig ...

had already reached an astoundingly low price compared to what could be found in his home country. Of this, he said:

Other modern scholars such as Endymion Wilkinson hold a more conservative and skeptical view. While Wilkinson does not deny "China's dominance in book production from the fourth to the fifteenth century," he also insists that arguments for the Chinese advantage "should not be extended either forwards or backwards in time."

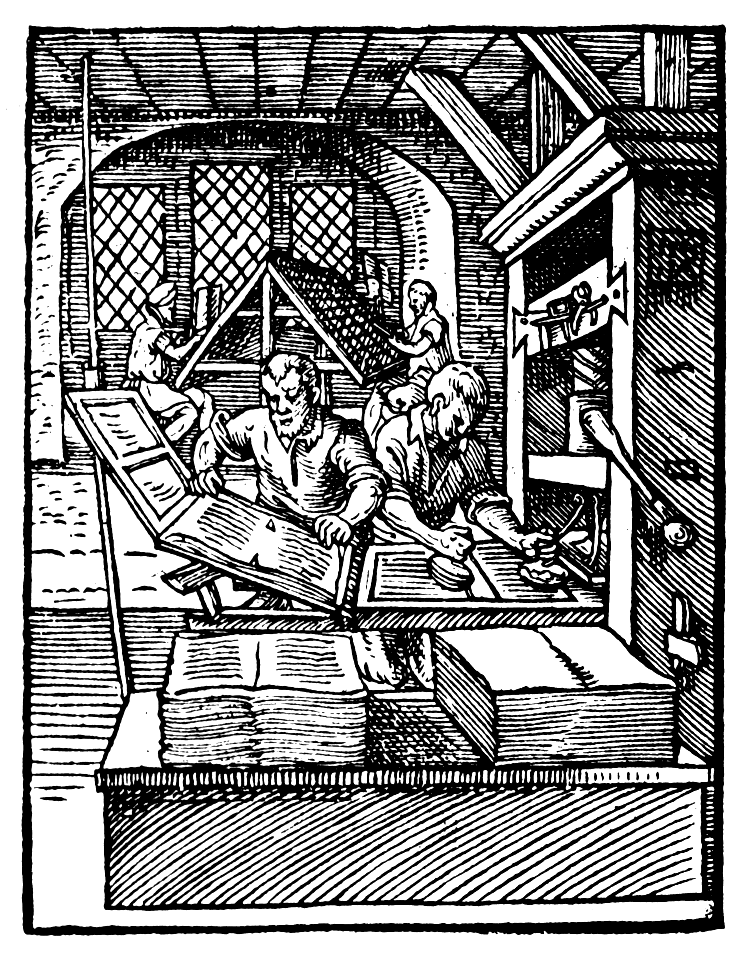

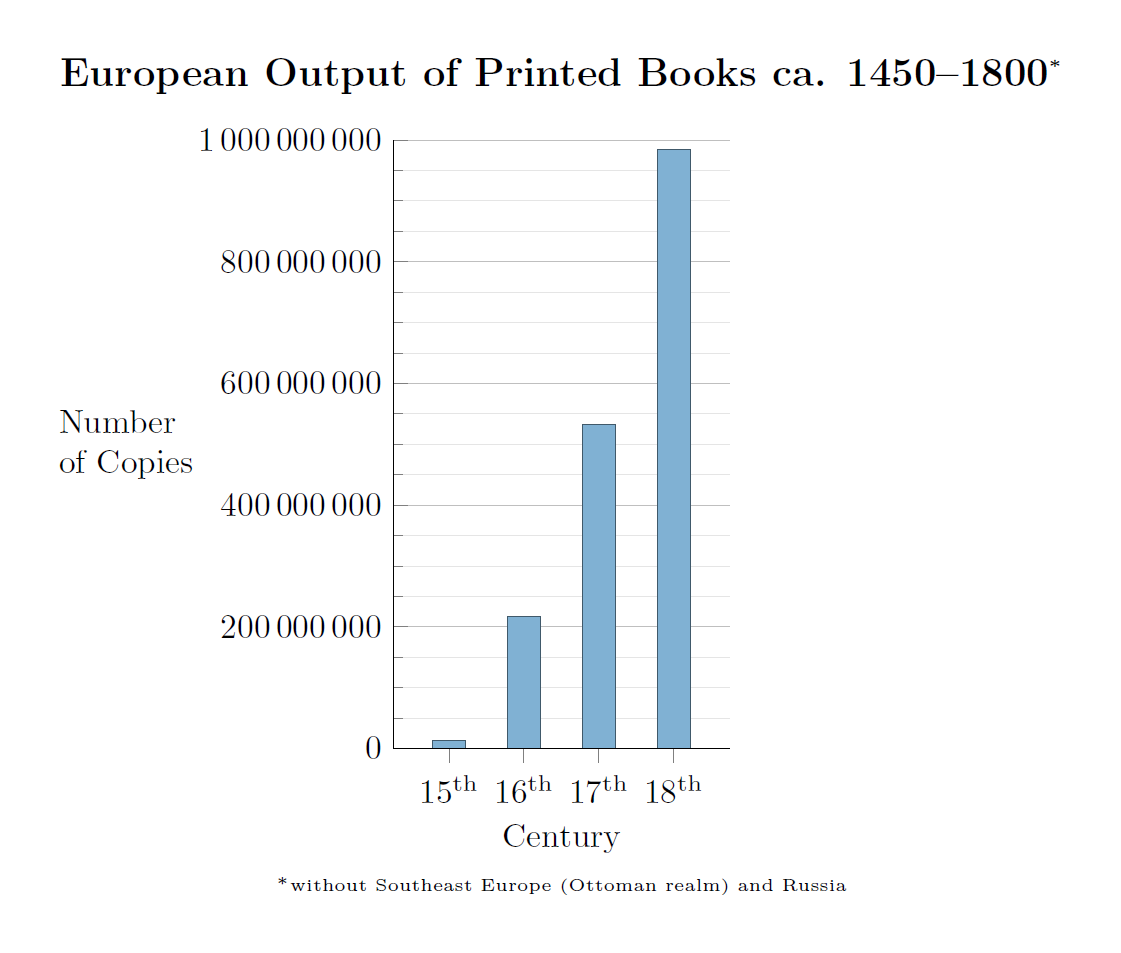

European movable type (1439)

Eastern metal movable type was spread to Europe between the late 14th and early 15th centuries. Historians

Frances Gies and Joseph Gies Frances Gies (June 10, 1915 – December 18, 2013) and Joseph Gies (October 8, 1916 – April 13, 2006) were historians and writers who collaborated on a number of books about the Middle Ages, and also wrote individual works. They were hus ...

claimed that "The Asian priority of invention movable type is now firmly established, and that Chinese-Korean technique, or a report of it traveled westward is almost certain."

[ Gies, Frances and Gies, Joseph (1994) ''Cathedral, Forge, and Waterwheel: Technology and Invention in the Middle Age'', New York : HarperCollins, , P 241] However, Joseph P. McDermott claimed that "No text indicates the presence or knowledge of any kind of Asian movable type or movable type imprint in Europe before 1450. The material evidence is even more conclusive."

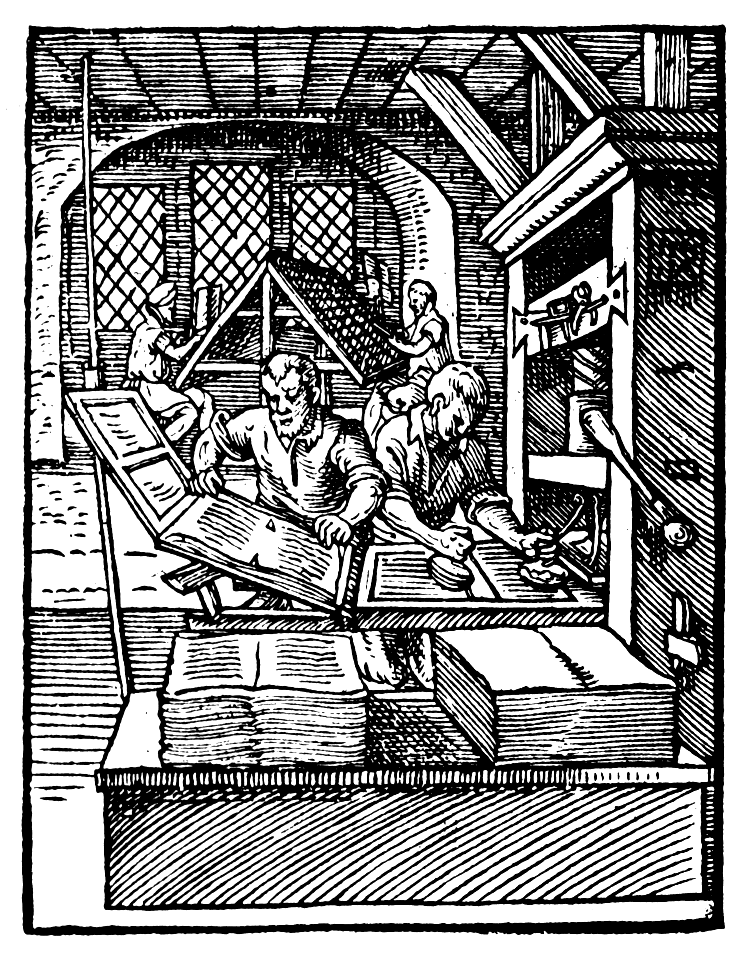

It is traditionally surmised that

Johannes Gutenberg

Johannes Gensfleisch zur Laden zum Gutenberg (; – 3 February 1468) was a German inventor and craftsman who introduced letterpress printing to Europe with his movable-type printing press. Though not the first of its kind, earlier designs ...

, of the German city of

Mainz

Mainz () is the capital and largest city of Rhineland-Palatinate, Germany.

Mainz is on the left bank of the Rhine, opposite to the place that the Main joins the Rhine. Downstream of the confluence, the Rhine flows to the north-west, with Ma ...

, developed European movable type printing technology with the

printing press

A printing press is a mechanical device for applying pressure to an inked surface resting upon a print medium (such as paper or cloth), thereby transferring the ink. It marked a dramatic improvement on earlier printing methods in which the ...

around 1439

and in just over a decade, the European age of printing began. However, the evidence shows a more complex evolutionary process,

spread over multiple locations. Also,

Johann Fust

Johann Fust or Faust (c. 1400 – October 30, 1466) was an early German printer.

Family background

Fust was born to burgher family of Mainz, traceable back to the early thirteenth century. Members of the family held many civil and religi ...

and

Peter Schöffer experimented with Gutenberg in Mainz.

Compared to

woodblock printing

Woodblock printing or block printing is a technique for printing text, images or patterns used widely throughout East Asia and originating in China in antiquity as a method of printing on textiles and later paper. Each page or image is crea ...

, movable type page-setting was quicker and more durable. The metal type pieces were more durable and the lettering was more uniform, leading to typography and

font

In metal typesetting, a font is a particular size, weight and style of a typeface. Each font is a matched set of type, with a piece (a " sort") for each glyph. A typeface consists of a range of such fonts that shared an overall design.

In mo ...

s. The high quality and relatively low price of the

Gutenberg Bible

The Gutenberg Bible (also known as the 42-line Bible, the Mazarin Bible or the B42) was the earliest major book printed using mass-produced movable metal type in Europe. It marked the start of the " Gutenberg Revolution" and the age of printed ...

(1455) established the superiority of movable type, and printing presses rapidly spread across Europe, leading up to the

Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ide ...

, and later all around the world. Today, practically all movable type printing ultimately derives from Gutenberg's movable type printing, which is often regarded as the most important invention of the second millennium.

Gutenberg is also credited with the introduction of an oil-based ink which was more durable than previously used water-based inks. Having worked as a professional

goldsmith

A goldsmith is a metalworker who specializes in working with gold and other precious metals. Nowadays they mainly specialize in jewelry-making but historically, goldsmiths have also made silverware, platters, goblets, decorative and servicea ...

, Gutenberg made skillful use of his knowledge of metals. He was also the first to make his type from an

alloy

An alloy is a mixture of chemical elements of which at least one is a metal. Unlike chemical compounds with metallic bases, an alloy will retain all the properties of a metal in the resulting material, such as electrical conductivity, ductili ...

of lead, tin, and

antimony

Antimony is a chemical element with the symbol Sb (from la, stibium) and atomic number 51. A lustrous gray metalloid, it is found in nature mainly as the sulfide mineral stibnite (Sb2S3). Antimony compounds have been known since ancient ti ...

, known as

type metal

In printing, type metal refers to the metal alloys used in traditional typefounding and hot metal typesetting. Historically, type metal was an alloy of lead, tin and antimony in different proportions depending on the application, be it individ ...

, printer's lead, or printer's metal, which was critical for producing durable type that produced high-quality printed books, and proved to be more suitable for printing than the clay, wooden or bronze types used in East Asia. To create these lead types, Gutenberg used what some considered his most ingenious invention: a special matrix which enabled the moulding of new movable types with an unprecedented precision at short notice. Within a year of printing the Gutenberg Bible, Gutenberg also published the first coloured prints.

The invention of the printing press revolutionized communication and book production, leading to the spread of knowledge. Printing was rapidly spread from Germany by emigrating German printers, but also by foreign apprentices returning home. A printing press was built in

Venice

Venice ( ; it, Venezia ; vec, Venesia or ) is a city in northeastern Italy and the capital of the Veneto Regions of Italy, region. It is built on a group of 118 small islands that are separated by canals and linked by over 400 ...

in 1469, and by 1500 the city had 417 printers. In 1470

Johann Heynlin set up a printing press in

Paris

Paris () is the capital and most populous city of France, with an estimated population of 2,165,423 residents in 2019 in an area of more than 105 km² (41 sq mi), making it the 30th most densely populated city in the world in 2020. Si ...

. In 1473

Kasper Straube published the ''

Almanach cracoviense ad annum 1474'' in

Kraków

Kraków (), or Cracow, is the second-largest and one of the oldest cities in Poland. Situated on the Vistula, Vistula River in Lesser Poland Voivodeship, the city dates back to the seventh century. Kraków was the official capital of Poland un ...

.

Dirk Martens set up a printing press in

Aalst (

Flanders

Flanders (, ; Dutch: ''Vlaanderen'' ) is the Flemish-speaking northern portion of Belgium and one of the communities, regions and language areas of Belgium. However, there are several overlapping definitions, including ones related to cultu ...

) in 1473. He printed a book about the two lovers of

Enea Piccolomini who became

Pope Pius II

Pope Pius II ( la, Pius PP. II, it, Pio II), born Enea Silvio Bartolomeo Piccolomini ( la, Aeneas Silvius Bartholomeus, links=no; 18 October 1405 – 14 August 1464), was head of the Catholic Church and ruler of the Papal States from 19 Augu ...

. In 1476 a printing press was set up in England by

William Caxton

William Caxton ( – ) was an English merchant, diplomat and writer. He is thought to be the first person to introduce a printing press into England, in 1476, and as a printer to be the first English retailer of printed books.

His parentage a ...

. The Italian Juan Pablos set up an imported press in

Mexico City

Mexico City ( es, link=no, Ciudad de México, ; abbr.: CDMX; Nahuatl: ''Altepetl Mexico'') is the capital and largest city of Mexico, and the most populous city in North America. One of the world's alpha cities, it is located in the Valley o ...

in 1539. The first printing press in

Southeast Asia

Southeast Asia, also spelled South East Asia and South-East Asia, and also known as Southeastern Asia, South-eastern Asia or SEA, is the geographical south-eastern region of Asia, consisting of the regions that are situated south of mainland ...

was set up in the

Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

by the

Spanish in 1593. The Rev. Jose Glover intended to bring the first printing press to England's American colonies in 1638, but died on the voyage, so his widow, Elizabeth Harris Glover, established the printing house, which was run by Stephen Day and became The Cambridge Press.

The Gutenberg press was much more efficient than manual copying. It remained largely unchanged in the eras of

John Baskerville

John Baskerville (baptised 28 January 1707 – 8 January 1775) was an English businessman, in areas including japanning and papier-mâché, but he is best remembered as a printer and type designer. He was also responsible for inventing "w ...

and

Giambattista Bodoni

Giambattista Bodoni (, ; 16 February 1740 – 30 November 1813) was an Italian typographer, type-designer, compositor, printer, and publisher in Parma.

He first took the type-designs of Pierre Simon Fournier as his exemplars, but afterwards be ...

, over 300 years later.

[Meggs, Philip B. A History of Graphic Design. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 1998. (pp 130–133) ] By 1800, Lord Stanhope had constructed a press completely from cast iron, reducing the force required by 90% while doubling the size of the printed area.

While Stanhope's "mechanical theory" had improved the efficiency of the press, it was only capable of 250 sheets per hour.