History of anthropology on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

History of anthropology in this article refers primarily to the 18th- and 19th-century precursors of modern anthropology. The term anthropology itself, innovated as a

Another candidate for one of the first scholars to carry out comparative ethnographic-type studies in person was the medieval

Another candidate for one of the first scholars to carry out comparative ethnographic-type studies in person was the medieval

Many scholars consider modern anthropology as an outgrowth of the

Many scholars consider modern anthropology as an outgrowth of the

New Latin

New Latin (also called Neo-Latin or Modern Latin) is the revival of Literary Latin used in original, scholarly, and scientific works since about 1500. Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy ...

scientific word during the Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

, has always meant "the study (or science) of man". The topics to be included and the terminology have varied historically. At present they are more elaborate than they were during the development of anthropology. For a presentation of modern social and cultural anthropology as they have developed in Britain, France, and North America since approximately 1900, see the relevant sections under Anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

.

Etymology

The term ''anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

'' ostensibly is a produced compound of Greek

Greek may refer to:

Greece

Anything of, from, or related to Greece, a country in Southern Europe:

*Greeks, an ethnic group.

*Greek language, a branch of the Indo-European language family.

**Proto-Greek language, the assumed last common ancestor ...

''anthrōpos'', "human being" (understood to mean "humankind" or "humanity"), and a supposed -λογία ''-logia

''-logy'' is a suffix in the English language, used with words originally adapted from Ancient Greek ending in ('). The earliest English examples were anglicizations of the French '' -logie'', which was in turn inherited from the Latin '' -logi ...

'', "study". The compound, however, is unknown in ancient Greek or Latin, whether classical or mediaeval. It first appears sporadically in the scholarly Latin ''anthropologia'' of Renaissance France, where it spawns the French word ''anthropologie'', transferred into English as anthropology. It does belong to a class of words produced with the -logy

''-logy'' is a suffix in the English language, used with words originally adapted from Ancient Greek ending in ('). The earliest English examples were anglicizations of the French '' -logie'', which was in turn inherited from the Latin '' -log ...

suffix, such as archeo-logy, bio-logy, etc., "the study (or science) of".

The mixed character of Greek ''anthropos'' and Latin ''-logia'' marks it as New Latin

New Latin (also called Neo-Latin or Modern Latin) is the revival of Literary Latin used in original, scholarly, and scientific works since about 1500. Modern scholarly and technical nomenclature, such as in zoological and botanical taxonomy ...

. There is no independent noun, logia, however, of that meaning in classical Greek. The word λόγος (logos

''Logos'' (, ; grc, wikt:λόγος, λόγος, lógos, lit=word, discourse, or reason) is a term used in Western philosophy, psychology and rhetoric and refers to the appeal to reason that relies on logic or reason, inductive and deductive ...

) has that meaning. James Hunt

James Simon Wallis Hunt (29 August 1947 – 15 June 1993) ''Autocourse Grand Prix Archive'', 14 October 2007. Retrieved 4 November 2007. was a British racing driver who won the Formula One World Championship in . After retiring from racing in ...

attempted to rescue the etymology in his first address to the Anthropological Society of London

The Anthropological Society of London (ASL) was a short-lived organisation of the 1860s whose founders aimed to furnish scientific evidence for white supremacy which they construed in terms of polygenism. It was founded in 1863 by Richard Francis ...

as president and founder, 1863. He did find an ''anthropologos'' from Aristotle in the standard ancient Greek Lexicon, which he says defines the word as "speaking or treating of man". This view is entirely wishful thinking, as Liddell and Scott go on to explain the meaning: "i.e. fond of personal conversation". If Aristotle, the very philosopher of the logos, could produce such a word without serious intent, there probably was at that time no anthropology identifiable under that name.

The lack of any ancient denotation of anthropology, however, is not an etymological problem. Liddell and Scott list 170 Greek compounds ending in ''–logia'', enough to justify its later use as a productive suffix. The ancient Greeks often used suffixes in forming compounds that had no independent variant. The etymological dictionaries are united in attributing ''–logia'' to ''logos'', from ''legein'', "to collect". The thing collected is primarily ideas, especially in speech. The American Heritage Dictionary

American(s) may refer to:

* American, something of, from, or related to the United States of America, commonly known as the "United States" or "America"

** Americans, citizens and nationals of the United States of America

** American ancestry, pe ...

says: "(It is one of) derivatives independently built to logos." Its morphological type is that of an abstract noun: log-os > log-ia (a "qualitative abstract")

The Renaissance

The Renaissance ( , ) , from , with the same meanings. is a period in European history marking the transition from the Middle Ages to modernity and covering the 15th and 16th centuries, characterized by an effort to revive and surpass ideas ...

origin of the name of anthropology does not exclude the possibility that ancient authors presented anthropogical material under another name (see below). Such an identification is speculative, depending on the theorist's view of anthropology; nevertheless, speculations have been formulated by credible anthropologists, especially those that consider themselves functionalists and others in history so classified now.

The science of history

Marvin Harris

Marvin Harris (August 18, 1927 – October 25, 2001) was an American anthropologist. He was born in Brooklyn, New York City. A prolific writer, he was highly influential in the development of cultural materialism and environmental determinism. ...

, a historian of anthropology, begins ''The Rise of Anthropological Theory'' with the statement that anthropology is "the science of history". He is not suggesting that history

History (derived ) is the systematic study and the documentation of the human activity. The time period of event before the History of writing#Inventions of writing, invention of writing systems is considered prehistory. "History" is an umbr ...

be renamed to anthropology, or that there is no distinction between history and prehistory

Prehistory, also known as pre-literary history, is the period of human history between the use of the first stone tools by hominins 3.3 million years ago and the beginning of recorded history with the invention of writing systems. The use of ...

, or that anthropology excludes current social practices, as the general meaning of history, which it has in "history of anthropology", would seem to imply. He is using "history" in a special sense, as the founders of cultural anthropology

Cultural anthropology is a branch of anthropology focused on the study of cultural variation among humans. It is in contrast to social anthropology, which perceives cultural variation as a subset of a posited anthropological constant. The portma ...

used it: "the natural history of society", in the words of Herbert Spencer

Herbert Spencer (27 April 1820 – 8 December 1903) was an English philosopher, psychologist, biologist, anthropologist, and sociologist famous for his hypothesis of social Darwinism. Spencer originated the expression "survival of the fittest" ...

, or the "universal history of mankind", the 18th-century Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

objective. Just as natural history comprises the characteristics of organisms past and present, so cultural or social history comprises the characteristics of society past and present. It includes both documented history and prehistory, but its slant is toward institutional development rather than particular non-repeatable historical events.

According to Harris, the 19th-century anthropologists were theorizing under the presumption that the development of society followed some sort of laws. He decries the loss of that view in the 20th century by the denial that any laws are discernable or that current institutions have any bearing on ancient. He coins the term ideographic for them. The 19th-century views, on the other hand, are nomothetic

Nomothetic literally means "proposition of the law" (Greek derivation) and is used in philosophy, psychology, and law with differing meanings.

Etymology

In general humanities usage, ''nomothetic'' may be used in the sense of "able to lay down t ...

; that is, they provide laws. He intends "to reassert the methodological priority of the search for the laws of history in the science of man". He is looking for "a general theory of history". His perception of the laws: "I believe that the analogue of the Darwinian strategy in the realm of sociocultural phenomena is the principle of techno-environmental and techno-economic determinism", he calls cultural materialism, which he also details in ''Cultural Materialism: The Struggle for a Science of Culture.''

Elsewhere he refers to "my theories of historical determinism", defining the latter: "By a deterministic relationship among cultural phenomena, I mean merely that similar variables under similar conditions tend to give rise to similar consequences." The use of "tends to" implies some degree of freedom to happen or not happen, but in strict determinism

Determinism is a philosophical view, where all events are determined completely by previously existing causes. Deterministic theories throughout the history of philosophy have developed from diverse and sometimes overlapping motives and consi ...

, given certain causes, the result and only that result must occur. Different philosophers, however, use determinism in different senses. The deterministic element that Harris sees is lack of human social engineering: "free will and moral choice have had virtually no significant effect upon the direction taken thus far by evolving systems of social life."

Harris agrees with the 19th-century view that laws are abstraction

Abstraction in its main sense is a conceptual process wherein general rules and concepts are derived from the usage and classification of specific examples, literal ("real" or "concrete") signifiers, first principles, or other methods.

"An abstr ...

s from empirical evidence

Empirical evidence for a proposition is evidence, i.e. what supports or counters this proposition, that is constituted by or accessible to sense experience or experimental procedure. Empirical evidence is of central importance to the sciences and ...

: "...sociocultural entities are constructed from the direct or indirect observation of the behavior and thought of specific individuals ...." Institutions are not a physical reality; only people are. When they act in society, they do so according to the laws of history, of which they are not aware; hence, there is no historical element of free will. Like the 20th-century anthropologists in general, Harris places a high value on the empiricism, or collection of data. This function must be performed by trained observers.

He borrows terms from linguistics: just as a phon-etic system is a description of sounds developed without regard to the meaning and structure of the language, while a phon-emic system describes the meaningful sounds actually used within the language, so anthropological data can be emic and etic

In anthropology, folkloristics, and the social and behavioral sciences, emic () and etic () refer to two kinds of field research done and viewpoints obtained.

The "emic" approach is an insider's perspective, which looks at the beliefs, values ...

. Only trained observers can avoid eticism, or description without regard to the meaning in the culture: "... etics are in part observers' emics incorrectly applied to a foreign system...." He makes a further distinction between synchronic and diachronic. Synchronic ("same time") with reference to anthropological data is contemporaneous and cross-cultural. Diachronic ("through time") data shows the development of lines through time. Cultural materialism, being a "processually holistic and globally comparative scientific research strategy" must depend for accuracy on all four types of data. Cultural materialism differs from the others by the insertion of culture as the effect. Different material factors produce different cultures.

Harris, like many other anthropologists, in looking for anthropological method and data before the use of the term anthropology, had little difficulty finding them among the ancient authors. The ancients tended to see players on the stage of history as ethnic groups characterized by the same or similar languages and customs: the Persians, the Germans, the Scythians, etc. Thus the term history meant to a large degree the "story" of the fortunes of these players through time. The ancient authors never formulated laws. Apart from a rudimentary three-age system

The three-age system is the periodization of human pre-history (with some overlap into the historical periods in a few regions) into three time-periods: the Stone Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age; although the concept may also refer to o ...

, the stages of history, such as are found in Lubbock, Tylor, Morgan, Marx and others, are yet unformulated.

Proto-anthropology

Eriksen and Nielsen use the term proto-anthropology to refer to near-anthropological writings, which contain some of the criteria for being anthropology, but not all. They classify proto-anthropology as being "travel writing or social philosophy", going on to assert "It is only when these aspects ... are fused, that is, when data and theory are brought together, that anthropology appears." This process began to occur in the 18th century of theAge of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

.

Classical Age

Many anthropological writers find anthropological-quality theorizing in the works ofClassical Greece

Classical Greece was a period of around 200 years (the 5th and 4th centuries BC) in Ancient Greece,The "Classical Age" is "the modern designation of the period from about 500 B.C. to the death of Alexander the Great in 323 B.C." ( Thomas R. Marti ...

and Classical Rome

In modern historiography, ancient Rome refers to Roman civilisation from the founding of the city of Rome in the 8th century BC to the collapse of the Western Roman Empire in the 5th century AD. It encompasses the Roman Kingdom (753–509 BC ...

; for example, John Myres

Sir John Linton Myres Kt OBE FBA FRAI (3 July 1869 in Preston – 6 March 1954 in Oxford) was a British archaeologist and academic, who conducted excavations in Cyprus in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Life

He was the son of t ...

in ''Herodotus and Anthropology'' (1908); E. E. Sikes in ''The Anthropology of the Greeks'' (1914); Clyde Kluckhohn

Clyde Kluckhohn (; January 11, 1905 in Le Mars, Iowa – July 28, 1960 near Santa Fe, New Mexico), was an American anthropologist and social theorist, best known for his long-term ethnographic work among the Navajo and his contributions to the de ...

in ''Anthropology and the Classics'' (1961), and many others. An equally long list may be found in French and German as well as other languages.

Herodotus

Herodotus

Herodotus ( ; grc, , }; BC) was an ancient Greek historian and geographer from the Greek city of Halicarnassus, part of the Persian Empire (now Bodrum, Turkey) and a later citizen of Thurii in modern Calabria ( Italy). He is known f ...

was a 5th-century BC Greek historian who set about to chronicle and explain the Greco-Persian Wars

The Greco-Persian Wars (also often called the Persian Wars) were a series of conflicts between the Achaemenid Empire and Greek city-states that started in 499 BC and lasted until 449 BC. The collision between the fractious political world of the ...

that transpired early in that century. He did so in a surviving work conventionally termed ''the History'' or ''the Histories''. His first line begins: "These are the researches of Herodotus of Halicarnassus ...."

The Achaemenid Empire

The Achaemenid Empire or Achaemenian Empire (; peo, 𐎧𐏁𐏂, , ), also called the First Persian Empire, was an ancient Iranian empire founded by Cyrus the Great in 550 BC. Based in Western Asia, it was contemporarily the largest em ...

, deciding to bring Greece into its domain, conducted a massive invasion across the Bosphorus

The Bosporus Strait (; grc, Βόσπορος ; tr, İstanbul Boğazı 'Istanbul strait', colloquially ''Boğaz'') or Bosphorus Strait is a natural strait and an internationally significant waterway located in Istanbul in northwestern Tu ...

using multi-cultural troops raised from many different locations. They were decisively defeated by the Greek city-states. Herodotus was far from interested in only the non-repeatable events. He provides ethnic details and histories of the peoples within the empire and to the north of it, in most cases being the first to do so. His methods were reading accounts, interviewing witnesses, and in some cases taking notes for himself.

These "researches" have been considered anthropological since at least as early as the late 19th century. The title, "Father of History" (''pater historiae''), had been conferred on him probably by Cicero

Marcus Tullius Cicero ( ; ; 3 January 106 BC – 7 December 43 BC) was a Roman statesman, lawyer, scholar, philosopher, and academic skeptic, who tried to uphold optimate principles during the political crises that led to the estab ...

. Pointing out that John Myres

Sir John Linton Myres Kt OBE FBA FRAI (3 July 1869 in Preston – 6 March 1954 in Oxford) was a British archaeologist and academic, who conducted excavations in Cyprus in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Life

He was the son of t ...

in 1908 had believed that Herodotus was an anthropologist on a par with those of his own day, James M. Redfield asserts: "Herodotus, as we know, was both Father of History and Father of Anthropology." Herodotus calls his method of travelling around taking notes "theorizing". Redfield translates it as "tourism" with a scientific intent. He identifies three terms of Herodotus as overlapping on culture: ''diaitia'', material goods such as houses and consumables; '' ethea'', the mores or customs; and ''nomoi'', the authoritative precedents or law

Law is a set of rules that are created and are enforceable by social or governmental institutions to regulate behavior,Robertson, ''Crimes against humanity'', 90. with its precise definition a matter of longstanding debate. It has been vario ...

s.

Tacitus

TheRoman

Roman or Romans most often refers to:

*Rome, the capital city of Italy

*Ancient Rome, Roman civilization from 8th century BC to 5th century AD

*Roman people, the people of ancient Rome

*''Epistle to the Romans'', shortened to ''Romans'', a letter ...

historian, Tacitus

Publius Cornelius Tacitus, known simply as Tacitus ( , ; – ), was a Roman historian and politician. Tacitus is widely regarded as one of the greatest Roman historiography, Roman historians by modern scholars.

The surviving portions of his t ...

, wrote many of our only surviving contemporary accounts of several ancient Celtic

Celtic, Celtics or Keltic may refer to:

Language and ethnicity

*pertaining to Celts, a collection of Indo-European peoples in Europe and Anatolia

**Celts (modern)

*Celtic languages

**Proto-Celtic language

* Celtic music

*Celtic nations

Sports Fo ...

and Germanic peoples

The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages. Since the 19th century, they have traditionally been defined by the use of ancient and ear ...

.

Middle Ages

Another candidate for one of the first scholars to carry out comparative ethnographic-type studies in person was the medieval

Another candidate for one of the first scholars to carry out comparative ethnographic-type studies in person was the medieval Persian

Persian may refer to:

* People and things from Iran, historically called ''Persia'' in the English language

** Persians, the majority ethnic group in Iran, not to be conflated with the Iranic peoples

** Persian language, an Iranian language of the ...

scholar Abu Rayhan al-Biruni of the Islamic Golden Age

The Islamic Golden Age was a period of cultural, economic, and scientific flourishing in the history of Islam, traditionally dated from the 8th century to the 14th century. This period is traditionally understood to have begun during the reign ...

, who wrote about the peoples, customs, and religions of the Indian subcontinent

The Indian subcontinent is a list of the physiographic regions of the world, physiographical region in United Nations geoscheme for Asia#Southern Asia, Southern Asia. It is situated on the Indian Plate, projecting southwards into the Indian O ...

. According to Akbar S. Ahmed, like modern anthropologists, he engaged in extensive participant observation

Participant observation is one type of data collection method by practitioner-scholars typically used in qualitative research and ethnography. This type of methodology is employed in many disciplines, particularly anthropology (incl. cultural an ...

with a given group of people, learnt their language and studied their primary texts, and presented his findings with objectivity and neutrality using cross-cultural comparisons. Others argue, however, that he hardly can be considered an anthropologist in the conventional sense. He wrote detailed comparative studies on the religions and cultures in the Middle East

The Middle East ( ar, الشرق الأوسط, ISO 233: ) is a geopolitical region commonly encompassing Arabian Peninsula, Arabia (including the Arabian Peninsula and Bahrain), Anatolia, Asia Minor (Asian part of Turkey except Hatay Pro ...

, Mediterranean

The Mediterranean Sea is a sea connected to the Atlantic Ocean, surrounded by the Mediterranean Basin and almost completely enclosed by land: on the north by Western and Southern Europe and Anatolia, on the south by North Africa, and on the e ...

, and especially South Asia

South Asia is the southern subregion of Asia, which is defined in both geographical and ethno-cultural terms. The region consists of the countries of Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Bhutan, India, Maldives, Nepal, Pakistan, and Sri Lanka.;;;;;;;; ...

. Biruni's tradition of comparative cross-cultural study continued in the Muslim world

The terms Muslim world and Islamic world commonly refer to the Islamic community, which is also known as the Ummah. This consists of all those who adhere to the religious beliefs and laws of Islam or to societies in which Islam is practiced. I ...

through to Ibn Khaldun

Ibn Khaldun (; ar, أبو زيد عبد الرحمن بن محمد بن خلدون الحضرمي, ; 27 May 1332 – 17 March 1406, 732-808 AH) was an Arab

The Historical Muhammad', Irving M. Zeitlin, (Polity Press, 2007), p. 21; "It is, of ...

's work in the fourteenth century.

Medieval scholars may be considered forerunners of modern anthropology as well, insofar as they conducted or wrote detailed studies of the customs of peoples considered "different" from themselves in terms of geography. John of Plano Carpini reported of his stay among the Mongols

The Mongols ( mn, Монголчууд, , , ; ; russian: Монголы) are an East Asian ethnic group native to Mongolia, Inner Mongolia in China and the Buryatia Republic of the Russian Federation. The Mongols are the principal membe ...

. His report was unusual in its detailed depiction of a non-European culture.

Marco Polo

Marco Polo (, , ; 8 January 1324) was a Venetian merchant, explorer and writer who travelled through Asia along the Silk Road between 1271 and 1295. His travels are recorded in ''The Travels of Marco Polo'' (also known as ''Book of the Marv ...

's systematic observations of nature, anthropology, and geography are another example of studying human variation across space. Polo's travels took him across such a diverse human landscape and his accounts of the peoples he met as he journeyed were so detailed that they earned for Polo the name "the father of modern anthropology".

Renaissance

The first use of the term "anthropology" in English to refer to a natural science of humanity was apparently in Richard Harvey's 1593 ''Philadelphus, a defense of the legend of Brutus in British history'', which, includes the passage: "Genealogy or issue which they had, Artes which they studied, Actes which they did. This part of History is named Anthropology."The Enlightenment roots of the discipline

Many scholars consider modern anthropology as an outgrowth of the

Many scholars consider modern anthropology as an outgrowth of the Age of Enlightenment

The Age of Enlightenment or the Enlightenment; german: Aufklärung, "Enlightenment"; it, L'Illuminismo, "Enlightenment"; pl, Oświecenie, "Enlightenment"; pt, Iluminismo, "Enlightenment"; es, La Ilustración, "Enlightenment" was an intel ...

(1715–89), a period when Europeans attempted to study human behavior systematically, the known varieties of which had been increasing since the fifteenth century as a result of the first European colonization wave. The traditions of jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

, history, philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and writing, written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defin ...

, and sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of Empirical ...

then evolved into something more closely resembling the modern views of these disciplines and informed the development of the social sciences

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of soci ...

, of which anthropology was a part.

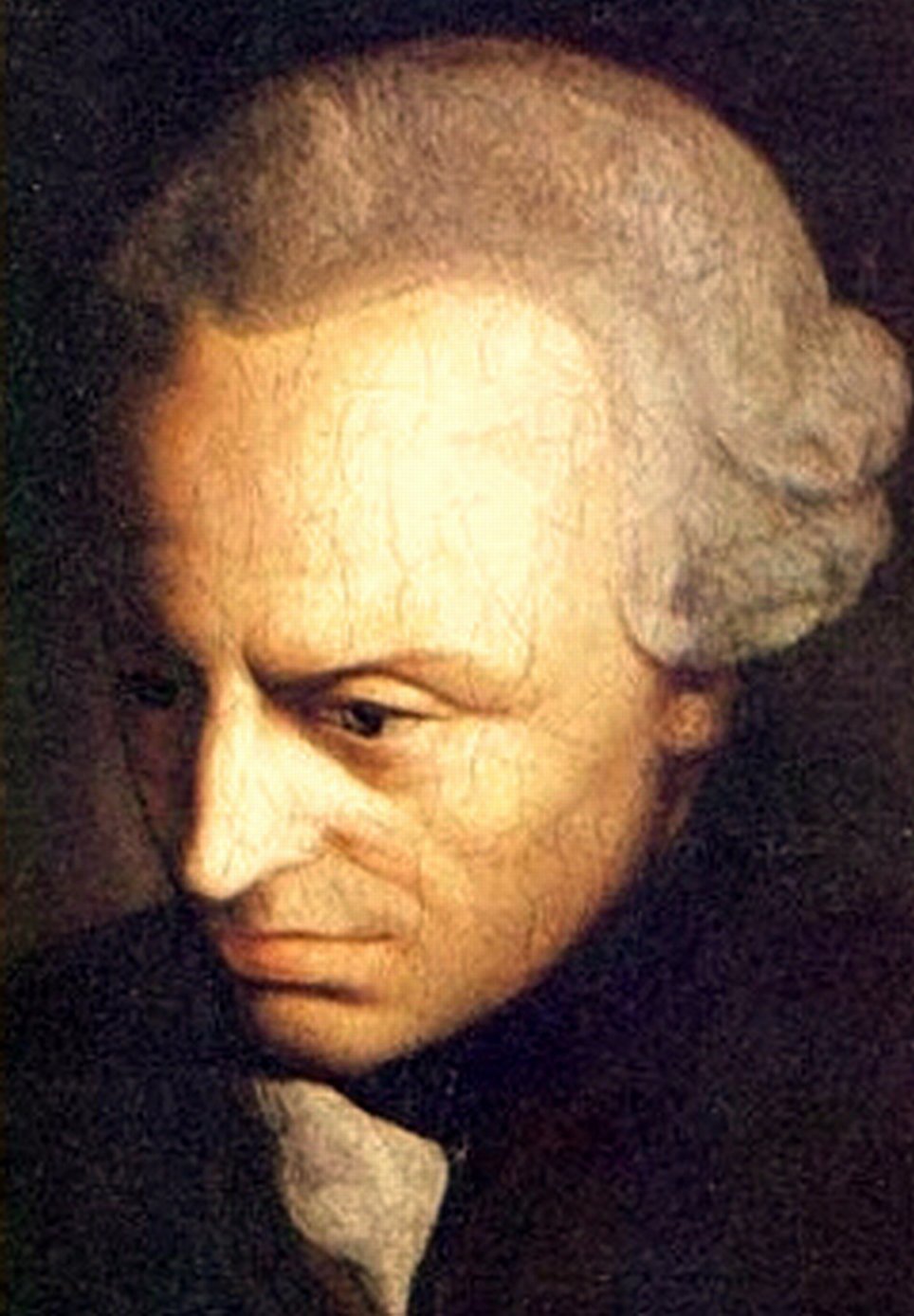

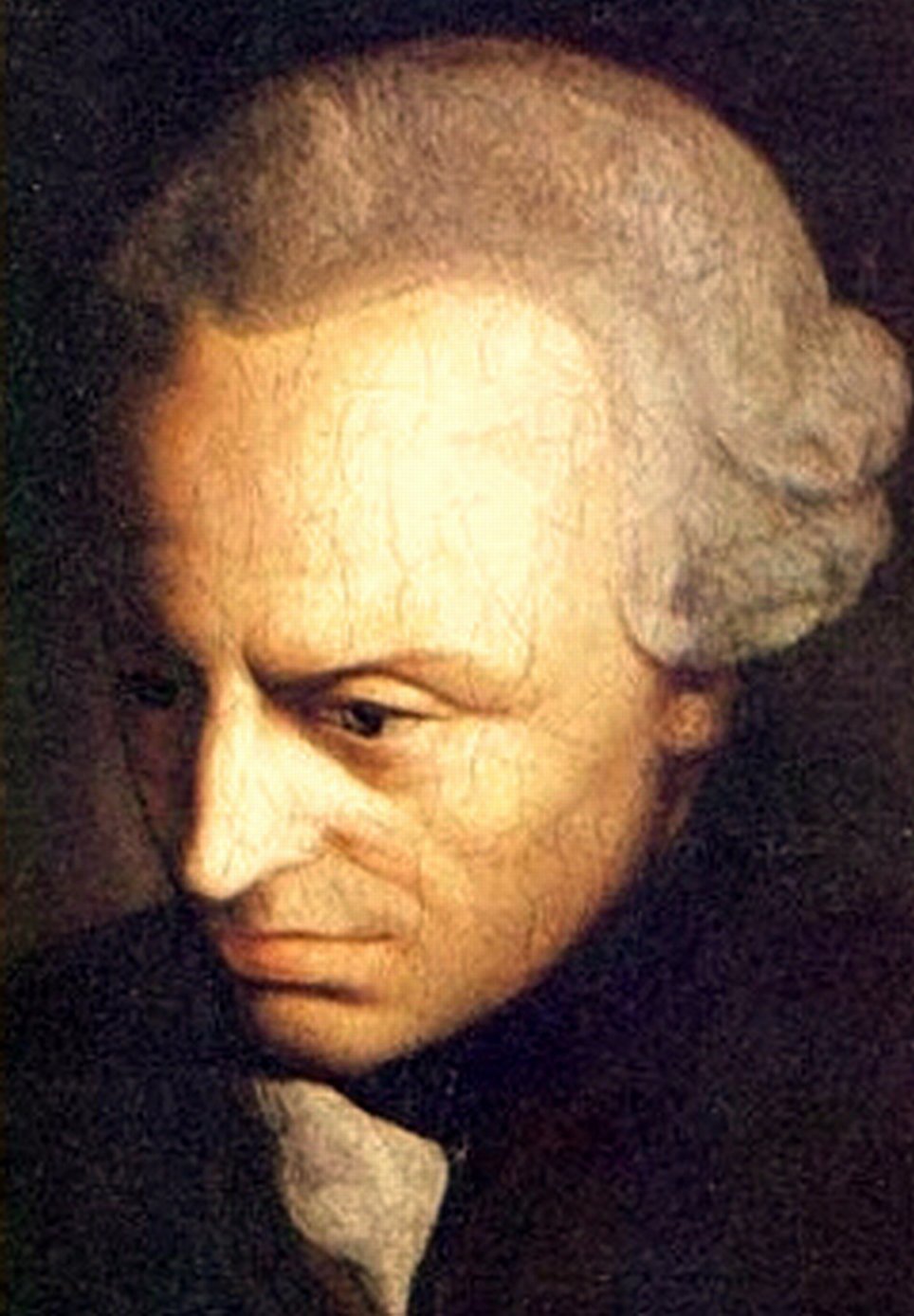

It took Immanuel Kant

Immanuel Kant (, , ; 22 April 1724 – 12 February 1804) was a German philosopher and one of the central Enlightenment thinkers. Born in Königsberg, Kant's comprehensive and systematic works in epistemology, metaphysics, ethics, and ...

(1724-1804) 25 years to write one of the first major treatises on anthropology, ''Anthropology from a Pragmatic Point of View'' (1798), which treats it as a branch of philosophy. Kant is not generally considered to be a modern anthropologist, as he never left his region of Germany, nor did he study any cultures besides his own. He did, however, begin teaching an annual course in anthropology in 1772.

Developments in the systematic study of ancient civilizations through the disciplines of Classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

and Egyptology

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , '' -logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious ...

informed both archaeology and eventually social anthropology, as did the study of East and South Asian languages and cultures. At the same time, the Romantic reaction to the Enlightenment produced thinkers, such as Johann Gottfried Herder

Johann Gottfried von Herder ( , ; 25 August 174418 December 1803) was a German philosopher, theologian, poet, and literary critic. He is associated with the Enlightenment, ''Sturm und Drang'', and Weimar Classicism.

Biography

Born in Mohrun ...

and later Wilhelm Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey (; ; 19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist, and hermeneutic philosopher, who held G. W. F. Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathic philosopher, w ...

, whose work formed the basis for the "culture concept", which is central to the discipline.

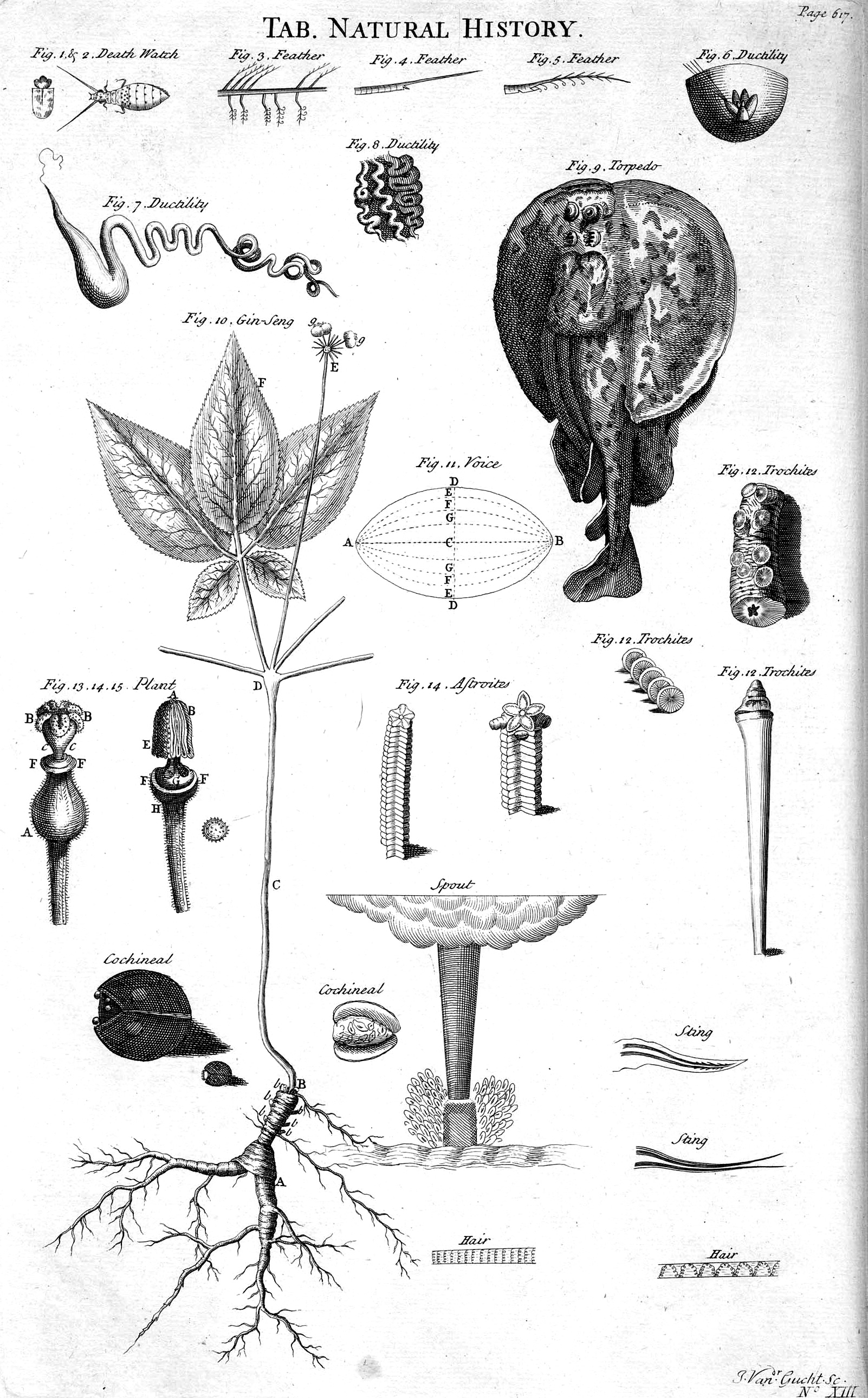

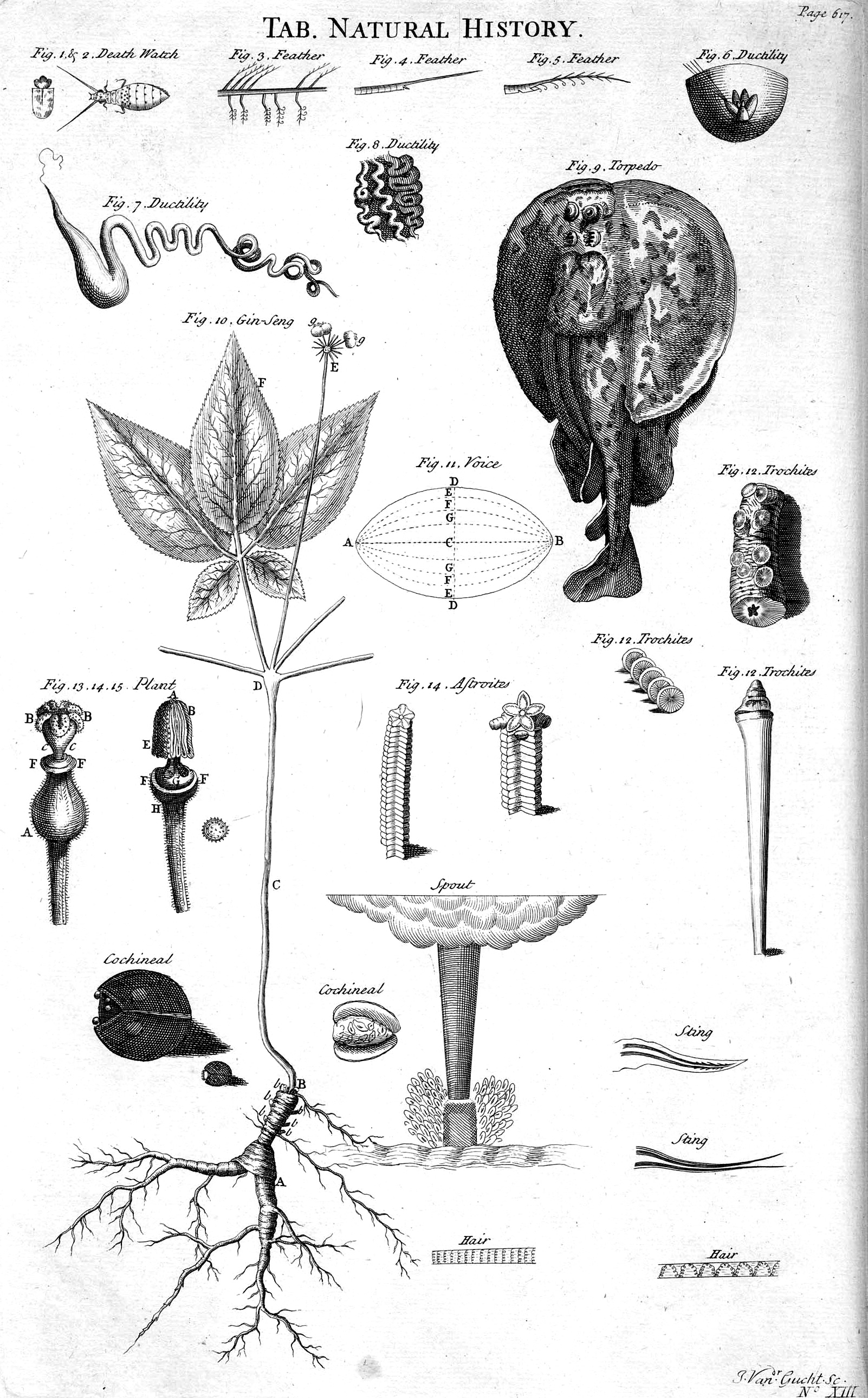

Institutionally, anthropology emerged from the development of natural history (expounded by authors such as Buffon) that occurred during the European colonization of the seventeenth, eighteenth, nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Programs of ethnographic study originated in this era as the study of the "human primitives" overseen by colonial administrations.

There was a tendency in late eighteenth century Enlightenment thought to understand human society as natural phenomena that behaved according to certain principles and that could be observed empirically. In some ways, studying the language, culture, physiology, and artifacts of European colonies was not unlike studying the flora and fauna of those places.

Early anthropology was divided between proponents of unilinealism, who argued that all societies passed through a single evolutionary process, from the most primitive to the most advanced, and various forms of non-lineal theorists, who tended to subscribe to ideas such as diffusionism

In cultural anthropology and cultural geography, cultural diffusion, as conceptualized by Leo Frobenius in his 1897/98 publication ''Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis'', is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, technolo ...

. Most nineteenth-century social theorists, including anthropologists, viewed non-European societies as windows onto the pre-industrial human past.

Overview of the modern discipline

Marxist anthropologistEric Wolf

Eric Robert Wolf (February 1, 1923 – March 6, 1999) was an anthropologist, best known for his studies of peasants, Latin America, and his advocacy of Marxist perspectives within anthropology.

Early life Life in Vienna

Wolf was born in Vi ...

once characterized anthropology as "the most scientific of the humanities, and the most humanistic of the social sciences". Understanding how anthropology

Anthropology is the scientific study of humanity, concerned with human behavior, human biology, cultures, societies, and linguistics, in both the present and past, including past human species. Social anthropology studies patterns of behavi ...

developed contributes to understanding how it fits into other academic disciplines.

Scholarly traditions of jurisprudence

Jurisprudence, or legal theory, is the theoretical study of the propriety of law. Scholars of jurisprudence seek to explain the nature of law in its most general form and they also seek to achieve a deeper understanding of legal reasoning a ...

, history, philology

Philology () is the study of language in oral and writing, written historical sources; it is the intersection of textual criticism, literary criticism, history, and linguistics (with especially strong ties to etymology). Philology is also defin ...

and sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of Empirical ...

developed during this time and informed the development of the social sciences

Social science is one of the branches of science, devoted to the study of societies and the relationships among individuals within those societies. The term was formerly used to refer to the field of sociology, the original "science of soci ...

of which anthropology was a part. At the same time, the Romantic reaction to the Enlightenment produced thinkers such as Herder

A herder is a pastoral worker responsible for the care and management of a herd or flock of domestic animals, usually on open pasture. It is particularly associated with nomadic or transhumant management of stock, or with common land grazing. ...

and later Wilhelm Dilthey

Wilhelm Dilthey (; ; 19 November 1833 – 1 October 1911) was a German historian, psychologist, sociologist, and hermeneutic philosopher, who held G. W. F. Hegel's Chair in Philosophy at the University of Berlin. As a polymathic philosopher, w ...

whose work formed the basis for the culture concept which is central to the discipline.

These intellectual movements in part grappled with one of the greatest paradoxes of modernity

Modernity, a topic in the humanities and social sciences, is both a historical period (the modern era) and the ensemble of particular socio-cultural norm (social), norms, attitudes and practices that arose in the wake of the Renaissancein the " ...

: as the world is becoming smaller and more integrated, people's experience of the world is increasingly atomized and dispersed. As Karl Marx

Karl Heinrich Marx (; 5 May 1818 – 14 March 1883) was a German philosopher, economist, historian, sociologist, political theorist, journalist, critic of political economy, and socialist revolutionary. His best-known titles are the 1848 ...

and Friedrich Engels

Friedrich Engels ( ,"Engels"

'' natural history (expounded by authors such as Buffon). This was the study of human beings—typically people living in European colonies. Thus studying the language, culture, physiology, and artifacts of European colonies was more or less equivalent to studying the flora and fauna of those places. It was for this reason, for instance, that

Anthropology in France has a less clear genealogy than the British and American traditions, in part because many French writers influential in anthropology have been trained or held faculty positions in sociology, philosophy, or other fields rather than in anthropology.

Anthropology in France has a less clear genealogy than the British and American traditions, in part because many French writers influential in anthropology have been trained or held faculty positions in sociology, philosophy, or other fields rather than in anthropology.

Boas used his positions at

Boas used his positions at

download

* * Hamilton, Michelle A. (2010) ''Collections and Objections: Aboriginal Material Culture in Southern Ontario.'' Montreal: MQUP. * * * * Hinsley, Curtis M. and David R. Wilcox, eds. ''Coming of Age in Chicago: The 1893 World's Fair and the Coalescence of American Anthropology'' (University of Nebraska Press, 2016). xliv, 574 pp. * * * Killan, Gerald. (1983) ''David Boyle: From Artisan to Archaeologist.'' Toronto: UTP. * * * Redman, Samuel J. Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2016. * * *

{{DEFAULTSORT:History Of Anthropology

'' natural history (expounded by authors such as Buffon). This was the study of human beings—typically people living in European colonies. Thus studying the language, culture, physiology, and artifacts of European colonies was more or less equivalent to studying the flora and fauna of those places. It was for this reason, for instance, that

Lewis Henry Morgan

Lewis Henry Morgan (November 21, 1818 – December 17, 1881) was a pioneering American anthropologist and social theorist who worked as a railroad lawyer. He is best known for his work on kinship and social structure, his theories of social evol ...

could write monographs on both ''The League of the Iroquois'' and ''The American Beaver and His Works''. This is also why the material culture of 'civilized' nations such as China have historically been displayed in fine arts museums alongside European art while artifacts from Africa or Native North American cultures were displayed in natural history museum

A natural history museum or museum of natural history is a scientific institution with natural history collections that include current and historical records of animals, plants, fungi, ecosystems, geology, paleontology, climatology, and more. ...

s with dinosaur bones and nature dioramas. Curatorial practice has changed dramatically in recent years, and it would be wrong to see anthropology as merely an extension of colonial rule and European chauvinism

Chauvinism is the unreasonable belief in the superiority or dominance of one's own group or people, who are seen as strong and virtuous, while others are considered weak, unworthy, or inferior. It can be described as a form of extreme patriotis ...

, since its relationship to imperialism

Imperialism is the state policy, practice, or advocacy of extending power and dominion, especially by direct territorial acquisition or by gaining political and economic control of other areas, often through employing hard power (economic and ...

was and is complex.

Drawing on the methods of the natural science

Natural science is one of the branches of science concerned with the description, understanding and prediction of natural phenomena, based on empirical evidence from observation and experimentation. Mechanisms such as peer review and repeatab ...

s as well as developing new techniques involving not only structured interviews but unstructured "participant-observation"—and drawing on the new theory of evolution

Evolution is change in the heritable characteristics of biological populations over successive generations. These characteristics are the expressions of genes, which are passed on from parent to offspring during reproduction. Variation t ...

through natural selection

Natural selection is the differential survival and reproduction of individuals due to differences in phenotype. It is a key mechanism of evolution, the change in the heritable traits characteristic of a population over generations. Charle ...

, they proposed the scientific study of a new object: "humankind", conceived of as a whole. Crucial to this study is the concept "culture", which anthropologists defined both as a universal capacity and propensity for social learning, thinking, and acting (which they see as a product of human evolution and something that distinguishes Homo sapiens—and perhaps all species of genus ''Homo

''Homo'' () is the genus that emerged in the (otherwise extinct) genus ''Australopithecus'' that encompasses the extant species ''Homo sapiens'' ( modern humans), plus several extinct species classified as either ancestral to or closely relate ...

''—from other species), and as a particular adaptation to local conditions that takes the form of highly variable beliefs and practices. Thus, "culture" not only transcends the opposition between nature and nurture; it transcends and absorbs the peculiarly European distinction between politics, religion, kinship, and the economy as autonomous domains. Anthropology thus transcends the divisions between the natural sciences, social sciences, and humanities to explore the biological, linguistic, material, and symbolic dimensions of humankind in all forms.

National anthropological traditions

As academic disciplines began to differentiate over the course of the nineteenth century, anthropology grew increasingly distinct from the biological approach of natural history, on the one hand, and from purely historical or literary fields such as Classics, on the other. A common criticism was that many social sciences (such as economists, sociologists, and psychologists) in Western countries focused disproportionately on Western subjects, while anthropology focused disproportionately on the "other".Britain

Museums such as theBritish Museum

The British Museum is a public museum dedicated to human history, art and culture located in the Bloomsbury area of London. Its permanent collection of eight million works is among the largest and most comprehensive in existence. It docum ...

weren't the only site of anthropological studies: with the New Imperialism

In historical contexts, New Imperialism characterizes a period of colonial expansion by European powers, the United States, and Japan during the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

Com

The period featured an unprecedented pursuit of ove ...

period, starting in the 1870s, zoo

A zoo (short for zoological garden; also called an animal park or menagerie) is a facility in which animals are kept within enclosures for public exhibition and often bred for Conservation biology, conservation purposes.

The term ''zoological g ...

s became unattended "laboratories", especially the so-called "ethnological exhibitions" or "Negro villages". Thus, "savages" from the colonies were displayed, often nudes, in cages, in what has been called "human zoos

Human zoos, also known as ethnological expositions, were public displays of people, usually in a so-called "natural" or "primitive" state. They were most prominent during the 19th and 20th centuries. These displays sometimes emphasized the sup ...

". For example, in 1906, Congolese pygmy

In anthropology, pygmy peoples are ethnic groups whose average height is unusually short. The term pygmyism is used to describe the phenotype of endemic short stature (as opposed to disproportionate dwarfism occurring in isolated cases in a pop ...

Ota Benga

Ota Benga ( – March 20, 1916) was a Mbuti ( Congo pygmy) man, known for being featured in an exhibit at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exposition in St. Louis, Missouri, and as a human zoo exhibit in 1906 at the Bronx Zoo. Benga had been pur ...

was put by anthropologist Madison Grant

Madison Grant (November 19, 1865 – May 30, 1937) was an American lawyer, zoologist, anthropologist, and writer known primarily for his work as a eugenicist and conservationist, and as an advocate of scientific racism. Grant is less noted f ...

in a cage in the Bronx Zoo

The Bronx Zoo (also historically the Bronx Zoological Park and the Bronx Zoological Gardens) is a zoo within Bronx Park in the Bronx, New York. It is one of the largest zoos in the United States by area and is the largest metropolitan zoo in ...

, labelled "the missing link" between an orangutan and the "white race"—Grant, a renowned eugenicist

Eugenics ( ; ) is a fringe set of beliefs and practices that aim to improve the genetic quality of a human population. Historically, eugenicists have attempted to alter human gene pools by excluding people and groups judged to be inferior or ...

, was also the author of ''The Passing of the Great Race

''The Passing of the Great Race: Or, The Racial Basis of European History'' is a 1916 racist and pseudoscientific book by American lawyer, self-styled anthropologist, and proponent of eugenics, Madison Grant (1865–1937). Grant expounds a theor ...

'' (1916). Such exhibitions were attempts to illustrate and prove in the same movement the validity of scientific racism

Scientific racism, sometimes termed biological racism, is the pseudoscience, pseudoscientific belief that empirical evidence exists to support or justify racism (racial discrimination), racial inferiority, or racial superiority.. "Few tragedies ...

, which first formulation may be found in Arthur de Gobineau

Joseph Arthur de Gobineau (; 14 July 1816 – 13 October 1882) was a French aristocrat who is best known for helping to legitimise racism by the use of scientific racist theory and "racial demography", and for developing the theory of the Aryan ...

's '' An Essay on the Inequality of Human Races'' (1853–55). In 1931, the Colonial Exhibition

A colonial exhibition was a type of international exhibition that was held to boost trade. During the 1880s and beyond, colonial exhibitions had the additional aim of bolstering popular support for the various colonial empires ...

in Paris still displayed Kanaks

The Kanak ( French spelling until 1984: Canaque) are the indigenous Melanesian inhabitants of New Caledonia, an overseas collectivity of France in the southwest Pacific. According to the 2019 census, the Kanak make up 41.2% of New Caledonia's ...

from New Caledonia

)

, anthem = ""

, image_map = New Caledonia on the globe (small islands magnified) (Polynesia centered).svg

, map_alt = Location of New Caledonia

, map_caption = Location of New Caledonia

, mapsize = 290px

, subdivision_type = Sovereign st ...

in the "indigenous village"; it received 24 million visitors in six months, thus demonstrating the popularity of such "human zoos".

Anthropology grew increasingly distinct from natural history and by the end of the nineteenth century the discipline began to crystallize into its modern form—by 1935, for example, it was possible for T.K. Penniman to write a history of the discipline entitled ''A Hundred Years of Anthropology''. At the time, the field was dominated by 'the comparative method'. It was assumed that all societies passed through a single evolutionary process from the most primitive to most advanced. Non-European societies were thus seen as evolutionary 'living fossils' that could be studied in order to understand the European past. Scholars wrote histories of prehistoric migrations which were sometimes valuable but often also fanciful. It was during this time that Europeans first accurately traced Polynesia

Polynesia () "many" and νῆσος () "island"), to, Polinisia; mi, Porinihia; haw, Polenekia; fj, Polinisia; sm, Polenisia; rar, Porinetia; ty, Pōrīnetia; tvl, Polenisia; tkl, Polenihia (, ) is a subregion of Oceania, made up of ...

n migrations across the Pacific Ocean

The Pacific Ocean is the largest and deepest of Earth's five oceanic divisions. It extends from the Arctic Ocean in the north to the Southern Ocean (or, depending on definition, to Antarctica) in the south, and is bounded by the continen ...

for instance—although some of them believed it originated in Egypt

Egypt ( ar, مصر , ), officially the Arab Republic of Egypt, is a transcontinental country spanning the northeast corner of Africa and southwest corner of Asia via a land bridge formed by the Sinai Peninsula. It is bordered by the Mediter ...

. Finally, the concept of race

Race, RACE or "The Race" may refer to:

* Race (biology), an informal taxonomic classification within a species, generally within a sub-species

* Race (human categorization), classification of humans into groups based on physical traits, and/or s ...

was actively discussed as a way to classify—and rank—human beings based on difference.

E.B. Tylor and James Frazer

Edward Burnett Tylor

Sir Edward Burnett Tylor (2 October 18322 January 1917) was an English anthropologist, and professor of anthropology.

Tylor's ideas typify 19th-century cultural evolutionism. In his works '' Primitive Culture'' (1871) and ''Anthropology'' ...

(2 October 1832 – 2 January 1917) and James George Frazer

Sir James George Frazer (; 1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) was a Scottish social anthropologist and folklorist influential in the early stages of the modern studies of mythology and comparative religion.

Personal life

He was born on 1 Janua ...

(1 January 1854 – 7 May 1941) are generally considered the antecedents to modern social anthropology

Social anthropology is the study of patterns of behaviour in human societies and cultures. It is the dominant constituent of anthropology throughout the United Kingdom and much of Europe, where it is distinguished from cultural anthropology. In t ...

in Britain. Although Tylor undertook a field trip to Mexico

Mexico (Spanish: México), officially the United Mexican States, is a country in the southern portion of North America. It is bordered to the north by the United States; to the south and west by the Pacific Ocean; to the southeast by Guatema ...

, both he and Frazer derived most of the material for their comparative studies through extensive reading, not fieldwork

Field research, field studies, or fieldwork is the collection of raw data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting. The approaches and methods used in field research vary across disciplines. For example, biologists who conduct fie ...

, mainly the Classics (literature and history of Greece and Rome), the work of the early European folklorists, and reports from missionaries, travelers, and contemporaneous ethnologists.

Tylor advocated strongly for unilinealism and a form of "uniformity of mankind". Tylor in particular laid the groundwork for theories of cultural diffusionism

In cultural anthropology and cultural geography, cultural diffusion, as conceptualized by Leo Frobenius in his 1897/98 publication ''Der westafrikanische Kulturkreis'', is the spread of cultural items—such as ideas, styles, religions, technolo ...

, stating that there are three ways that different groups can have similar cultural forms or technologies: "independent invention, inheritance from ancestors in a distant region, transmission from one race to another".

Tylor formulated one of the early and influential anthropological conceptions of culture

Culture () is an umbrella term which encompasses the social behavior, institutions, and norms found in human societies, as well as the knowledge, beliefs, arts, laws, customs, capabilities, and habits of the individuals in these groups.Tyl ...

as "that complex whole, which includes knowledge, belief, art, morals, law, custom, and any other capabilities and habits acquired by umansas embers

''Embers'' is a radio play by Samuel Beckett. It was written in English in 1957. First broadcast on the BBC Third Programme on 24 June 1959, the play won the RAI prize at the Prix Italia awards later that year. Donald McWhinnie directed Jack ...

of society". However, as Stocking notes, Tylor mainly concerned himself with describing and mapping the distribution of particular elements of culture, rather than with the larger function, and he generally seemed to assume a Victorian idea of progress rather than the idea of non-directional, multilineal cultural development proposed by later anthropologists.

Tylor also theorized about the origins of religious beliefs in human beings, proposing a theory of animism

Animism (from Latin: ' meaning 'breath, Soul, spirit, life') is the belief that objects, places, and creatures all possess a distinct Spirituality, spiritual essence. Potentially, animism perceives all things—Animal, animals, Plant, plants, Ro ...

as the earliest stage, and noting that "religion" has many components, of which he believed the most important to be belief in supernatural beings (as opposed to moral systems, cosmology, etc.). Frazer, a Scottish scholar with a broad knowledge of Classics, also concerned himself with religion, myth, and magic. His comparative studies, most influentially in the numerous editions of ''The Golden Bough

''The Golden Bough: A Study in Comparative Religion'' (retitled ''The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion'' in its second edition) is a wide-ranging, comparative study of mythology and religion, written by the Scottish anthropologist Sir ...

'', analyzed similarities in religious belief and symbolism globally. Neither Tylor nor Frazer, however, was particularly interested in fieldwork

Field research, field studies, or fieldwork is the collection of raw data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting. The approaches and methods used in field research vary across disciplines. For example, biologists who conduct fie ...

, nor were they interested in examining how the cultural elements and institutions fit together. The Golden Bough was abridged drastically in subsequent editions after his first.

Bronislaw Malinowski and the British School

Toward the turn of the twentieth century, a number of anthropologists became dissatisfied with this categorization of cultural elements; historical reconstructions also came to seem increasingly speculative to them. Under the influence of several younger scholars, a new approach came to predominate among British anthropologists, concerned with analyzing how societies held together in the present (synchronic

Synchronic may refer to:

* ''Synchronic'' (film), a 2019 American science fiction film starring Jamie Dornan and Anthony Mackie

* Synchronic analysis, the analysis of a language at a specific point of time

*Synchronicity

Synchronicity (german: ...

analysis, rather than diachronic

Synchrony and diachrony are two complementary viewpoints in linguistic analysis. A ''synchronic'' approach (from grc, συν- "together" and "time") considers a language at a moment in time without taking its history into account. Synchronic l ...

or historical analysis), and emphasizing long-term (one to several years) immersion fieldwork. Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

financed a multidisciplinary expedition to the Torres Strait Islands

The Torres Strait Islands are a group of at least 274 small islands in the Torres Strait, a waterway separating far northern continental Australia's Cape York Peninsula and the island of New Guinea. They span an area of , but their total land ...

in 1898, organized by Alfred Cort Haddon

Alfred Cort Haddon, Sc.D., FRS, FRGS FRAI (24 May 1855 – 20 April 1940, Cambridge) was an influential British anthropologist and ethnologist.

Initially a biologist, who achieved his most notable fieldwork, with W.H.R. Rivers, C.G. Seligma ...

and including a physician-anthropologist, William Rivers

William Halse Rivers Rivers FRS FRAI ( – ) was an English anthropologist, neurologist, ethnologist and psychiatrist known for treatment of First World War officers suffering shell shock, so they could be returned to combat. Rivers' most f ...

, as well as a linguist, a botanist, and other specialists. The findings of the expedition set new standards for ethnographic description.

A decade and a half later, Polish anthropology student Bronisław Malinowski

Bronisław Kasper Malinowski (; 7 April 1884 – 16 May 1942) was a Polish-British anthropologist and ethnologist whose writings on ethnography, social theory, and field research have exerted a lasting influence on the discipline of anthropol ...

(1884–1942) was beginning what he expected to be a brief period of fieldwork

Field research, field studies, or fieldwork is the collection of raw data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting. The approaches and methods used in field research vary across disciplines. For example, biologists who conduct fie ...

in the old model, collecting lists of cultural items, when the outbreak of the First World War stranded him in New Guinea

New Guinea (; Hiri Motu

Hiri Motu, also known as Police Motu, Pidgin Motu, or just Hiri, is a language of Papua New Guinea, which is spoken in surrounding areas of Port Moresby (Capital of Papua New Guinea).

It is a simplified version of ...

. As a subject of the Austro-Hungarian Empire

Austria-Hungary, often referred to as the Austro-Hungarian Empire,, the Dual Monarchy, or Austria, was a constitutional monarchy and great power in Central Europe between 1867 and 1918. It was formed with the Austro-Hungarian Compromise of ...

resident on a British colonial possession, he was effectively confined to New Guinea for several years.

He made use of the time by undertaking far more intensive fieldwork than had been done by ''British'' anthropologists, and his classic ethnography, ''Argonauts of the Western Pacific

''Argonauts of the Western Pacific: An Account of Native Enterprise and Adventure in the Archipelagoes of Melanesian New Guinea'' is a 1922 ethnological work by Bronisław Malinowski, which has had enormous impact on the ethnographic genre. The bo ...

'' (1922) advocated an approach to fieldwork

Field research, field studies, or fieldwork is the collection of raw data outside a laboratory, library, or workplace setting. The approaches and methods used in field research vary across disciplines. For example, biologists who conduct fie ...

that became standard in the field: getting "the native's point of view" through participant observation

Participant observation is one type of data collection method by practitioner-scholars typically used in qualitative research and ethnography. This type of methodology is employed in many disciplines, particularly anthropology (incl. cultural an ...

. Theoretically, he advocated a functionalist interpretation, which examined how social institutions functioned to satisfy individual needs.

British social anthropology had an expansive moment in the Interwar period

In the history of the 20th century, the interwar period lasted from 11 November 1918 to 1 September 1939 (20 years, 9 months, 21 days), the end of the World War I, First World War to the beginning of the World War II, Second World War. The in ...

, with key contributions coming from the Polish-British Bronisław Malinowski

Bronisław Kasper Malinowski (; 7 April 1884 – 16 May 1942) was a Polish-British anthropologist and ethnologist whose writings on ethnography, social theory, and field research have exerted a lasting influence on the discipline of anthropol ...

and Meyer Fortes

Meyer Fortes FBA FRAI (25 April 1906 – 27 January 1983) was a South African-born anthropologist, best known for his work among the Tallensi and Ashanti in Ghana.

Originally trained in psychology, Fortes employed the notion of the "person ...

A. R. Radcliffe-Brown also published a seminal work in 1922. He had carried out his initial fieldwork in the Andaman Islands

The Andaman Islands () are an archipelago in the northeastern Indian Ocean about southwest off the coasts of Myanmar's Ayeyarwady Region. Together with the Nicobar Islands to their south, the Andamans serve as a maritime boundary between th ...

in the old style of historical reconstruction. However, after reading the work of French sociologists Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim ( or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science, al ...

and Marcel Mauss

Marcel Mauss (; 10 May 1872 – 10 February 1950) was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and a ...

, Radcliffe-Brown published an account of his research (entitled simply ''The Andaman Islanders'') that paid close attention to the meaning and purpose of rituals and myths. Over time, he developed an approach known as structural functionalism

Structural functionalism, or simply functionalism, is "a framework for building theory that sees society as a complex system whose parts work together to promote solidarity and stability".

This approach looks at society through a macro-level o ...

, which focused on how institutions in societies worked to balance out or create an equilibrium in the social system to keep it functioning harmoniously. (This contrasted with Malinowski's functionalism, and was quite different from the later French structuralism

In sociology, anthropology, archaeology, history, philosophy, and linguistics, structuralism is a general theory of culture and methodology that implies that elements of human culture must be understood by way of their relationship to a broader ...

, which examined the conceptual structures in language and symbolism.)

Malinowski and Radcliffe-Brown's influence stemmed from the fact that they, like Boas, actively trained students and aggressively built up institutions that furthered their programmatic ambitions. This was particularly the case with Radcliffe-Brown, who spread his agenda for "Social Anthropology" by teaching at universities across the British Commonwealth

The Commonwealth of Nations, simply referred to as the Commonwealth, is a political association of 56 member states, the vast majority of which are former territories of the British Empire. The chief institutions of the organisation are the Co ...

. From the late 1930s until the postwar period appeared a string of monographs and edited volumes that cemented the paradigm of British Social Anthropology (BSA). Famous ethnographies include ''The Nuer

''The Nuer: A Description of the Modes of Livelihood and Political Institutions of a Nilotic People'' is an ethnographical study by the British anthropologist E. E. Evans-Pritchard (1902–73) first published in 1940. The work examined the polit ...

,'' by Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard

Sir Edward Evan Evans-Pritchard, Kt FBA FRAI (21 September 1902 – 11 September 1973) was an English anthropologist who was instrumental in the development of social anthropology. He was Professor of Social Anthropology at the Universit ...

, and ''The Dynamics of Clanship Among the Tallensi,'' by Meyer Fortes

Meyer Fortes FBA FRAI (25 April 1906 – 27 January 1983) was a South African-born anthropologist, best known for his work among the Tallensi and Ashanti in Ghana.

Originally trained in psychology, Fortes employed the notion of the "person ...

; well-known edited volumes include ''African Systems of Kinship and Marriage'' and ''African Political Systems.''

Post WW II trends

Max Gluckman

Herman Max Gluckman (; 26 January 1911 – 13 April 1975) was a South African and British social anthropologist. He is best known as the founder of the Manchester School of anthropology.

Biography and major works

Gluckman was born in Johan ...

, together with many of his colleagues at the Rhodes-Livingstone Institute

The Rhodes-Livingstone Institute (RLI) was the first local anthropological research facility in Africa; it was founded in 1937 under the initial directorship of Godfrey Wilson. It is located a few miles outside Lusaka. Designed to allow for easie ...

and students at Manchester University

, mottoeng = Knowledge, Wisdom, Humanity

, established = 2004 – University of Manchester Predecessor institutions: 1956 – UMIST (as university college; university 1994) 1904 – Victoria University of Manchester 1880 – Victoria Univer ...

, collectively known as the Manchester School, took BSA in new directions through their introduction of explicitly Marxist-informed theory, their emphasis on conflicts and conflict resolution, and their attention to the ways in which individuals negotiate and make use of the social structural possibilities.

In Britain, anthropology had a great intellectual impact, it "contributed to the erosion of Christianity

Christianity is an Abrahamic monotheistic religion based on the life and teachings of Jesus of Nazareth. It is the world's largest and most widespread religion with roughly 2.38 billion followers representing one-third of the global pop ...

, the growth of cultural relativism

Cultural relativism is the idea that a person's beliefs and practices should be understood based on that person's own culture. Proponents of cultural relativism also tend to argue that the norms and values of one culture should not be evaluated ...

, an awareness of the survival

Survival, or the act of surviving, is the propensity of something to continue existing, particularly when this is done despite conditions that might kill or destroy it. The concept can be applied to humans and other living things (or, hypotheti ...

of the primitive in modern life, and the replacement of diachronic

Synchrony and diachrony are two complementary viewpoints in linguistic analysis. A ''synchronic'' approach (from grc, συν- "together" and "time") considers a language at a moment in time without taking its history into account. Synchronic l ...

modes of analysis with synchronic

Synchronic may refer to:

* ''Synchronic'' (film), a 2019 American science fiction film starring Jamie Dornan and Anthony Mackie

* Synchronic analysis, the analysis of a language at a specific point of time

*Synchronicity

Synchronicity (german: ...

, all of which are central to modern culture."

Later in the 1960s and 1970s, Edmund Leach

Sir Edmund Ronald Leach FRAI FBA (7 November 1910 – 6 January 1989) was a British social anthropologist and academic. He served as provost of King's College, Cambridge from 1966 to 1979. He was also president of the Royal Anthropologi ...

and his students Mary Douglas

Dame Mary Douglas, (25 March 1921 – 16 May 2007) was a British anthropologist, known for her writings on human culture and symbolism, whose area of speciality was social anthropology. Douglas was considered a follower of Émile Durkhei ...

and Nur Yalman

Nur Yalman is a leading Turkish social anthropologist at Harvard University, where he serves as senior Research Professor of Social Anthropology and Middle Eastern Studies.

Career

Yalman received his high school diploma from Robert College, Istan ...

, among others, introduced French structuralism in the style of Lévi-Strauss; while British anthropology has continued to emphasize social organization and economics over purely symbolic or literary topics, differences among British, French, and American sociocultural anthropologies have diminished with increasing dialogue and borrowing of both theory and methods. Today, social anthropology in Britain engages internationally with many other social theories and has branched in many directions.

In countries of the British Commonwealth, social anthropology has often been institutionally separate from physical anthropology

Biological anthropology, also known as physical anthropology, is a scientific discipline concerned with the biological and behavioral aspects of human beings, their extinct Hominini, hominin ancestors, and related non-human primates, particularly ...

and primatology

Primatology is the scientific study of primates. It is a diverse Academic discipline, discipline at the boundary between mammalogy and anthropology, and researchers can be found in academic departments of anatomy, anthropology, biology, medici ...

, which may be connected with departments of biology or zoology; and from archaeology, which may be connected with departments of Classics

Classics or classical studies is the study of classical antiquity. In the Western world, classics traditionally refers to the study of Classical Greek and Roman literature and their related original languages, Ancient Greek and Latin. Classics ...

, Egyptology

Egyptology (from ''Egypt'' and Greek , '' -logia''; ar, علم المصريات) is the study of ancient Egyptian history, language, literature, religion, architecture and art from the 5th millennium BC until the end of its native religious ...

, and the like. In other countries (and in some, particularly smaller, British and North American universities), anthropologists have also found themselves institutionally linked with scholars of folklore

Folklore is shared by a particular group of people; it encompasses the traditions common to that culture, subculture or group. This includes oral traditions such as tales, legends, proverbs and jokes. They include material culture, ranging ...

, museum studies

Museology or museum studies is the study of museums. It explores the history of museums and their role in society, as well as the activities they engage in, including curating, preservation, public programming, and education.

Terminology

The w ...

, human geography

Human geography or anthropogeography is the branch of geography that studies spatial relationships between human communities, cultures, economies, and their interactions with the environment. It analyzes spatial interdependencies between social i ...

, sociology

Sociology is a social science that focuses on society, human social behavior, patterns of Interpersonal ties, social relationships, social interaction, and aspects of culture associated with everyday life. It uses various methods of Empirical ...

, social relations

A social relation or also described as a social interaction or social experience is the fundamental unit of analysis within the social sciences, and describes any voluntary or involuntary interpersonal relationship between two or more individuals ...

, ethnic studies

Ethnic studies, in the United States, is the interdisciplinary study of difference—chiefly race, ethnicity, and nation, but also sexuality, gender, and other such markings—and power, as expressed by the state, by civil society, and by indivi ...

, cultural studies

Cultural studies is an interdisciplinary field that examines the political dynamics of contemporary culture (including popular culture) and its historical foundations. Cultural studies researchers generally investigate how cultural practices re ...

, and social work

Social work is an academic discipline and practice-based profession concerned with meeting the basic needs of individuals, families, groups, communities, and society as a whole to enhance their individual and collective well-being. Social work ...

.

Anthropology has been used in Britain to provide an alternative explanation for the Financial crisis of 2007–2010

Finance is the study and discipline of money, currency and capital assets. It is related to, but not synonymous with economics, the study of production, distribution, and consumption of money, assets, goods and services (the discipline of fina ...

to the technical explanations rooted in economic and political theory. Dr. Gillian Tett

Gillian Tett (born 10 July 1967) is a British author and journalist at the ''Financial Times'', where she is chair of the editorial board and editor-at-large, US. She has written about the financial instruments that were part of the cause of the ...

, a Cambridge University

, mottoeng = Literal: From here, light and sacred draughts.

Non literal: From this place, we gain enlightenment and precious knowledge.

, established =

, other_name = The Chancellor, Masters and Schola ...

trained anthropologist who went on to become a senior editor at the Financial Times

The ''Financial Times'' (''FT'') is a British daily newspaper printed in broadsheet and published digitally that focuses on business and economic current affairs. Based in London, England, the paper is owned by a Japanese holding company, Nik ...

is one of the leaders in this use of anthropology.

Canada

Canadian anthropology began, as in other parts of the Colonial world, as ethnological data in the records of travellers and missionaries. In Canada,Jesuit

, image = Ihs-logo.svg

, image_size = 175px

, caption = ChristogramOfficial seal of the Jesuits

, abbreviation = SJ

, nickname = Jesuits

, formation =

, founders ...

missionaries

A missionary is a member of a religious group which is sent into an area in order to promote its faith or provide services to people, such as education, literacy, social justice, health care, and economic development.Thomas Hale 'On Being a Mi ...

such as Fathers LeClercq, Le Jeune and Sagard, in the 17th century, provide the oldest ethnographic records of native tribes in what was then the Dominion of Canada. The academic discipline has drawn strongly on both the British Social Anthropology and the American Cultural Anthropology traditions, producing a hybrid "Socio-cultural" anthropology.

George Mercer Dawson

True anthropology began with aGovernment department

Ministry or department (also less commonly used secretariat, office, or directorate) are designations used by first-level executive bodies in the machinery of governments that manage a specific sector of public administration." Энцикло� ...

: the Geological Survey of Canada

The Geological Survey of Canada (GSC; french: Commission géologique du Canada (CGC)) is a Canadian federal government agency responsible for performing geological surveys of the country, developing Canada's natural resources and protecting the en ...

, and George Mercer Dawson

George Mercer Dawson (August 1, 1849 – March 2, 1901) was a Canadian geologist and surveyor.

Biography

He was born in Pictou, Nova Scotia, the eldest son of Sir John William Dawson, Principal of McGill University and a noted geologis ...

(director in 1895). Dawson's support for anthropology created impetus for the profession in Canada. This was expanded upon by Prime Minister Wilfrid Laurier, who established a Division of Anthropology within the Geological Survey in 1910.

Edward Sapir

Anthropologists were recruited from England and the USA, setting the foundation for the unique Canadian style of anthropology. Scholars include the linguist and BoasianEdward Sapir

Edward Sapir (; January 26, 1884 – February 4, 1939) was an American Jewish anthropologist-linguist, who is widely considered to be one of the most important figures in the development of the discipline of linguistics in the United States.

Sa ...

.

France

Anthropology in France has a less clear genealogy than the British and American traditions, in part because many French writers influential in anthropology have been trained or held faculty positions in sociology, philosophy, or other fields rather than in anthropology.

Anthropology in France has a less clear genealogy than the British and American traditions, in part because many French writers influential in anthropology have been trained or held faculty positions in sociology, philosophy, or other fields rather than in anthropology.

Marcel Mauss

Most commentators considerMarcel Mauss

Marcel Mauss (; 10 May 1872 – 10 February 1950) was a French sociologist and anthropologist known as the "father of French ethnology". The nephew of Émile Durkheim, Mauss, in his academic work, crossed the boundaries between sociology and a ...

(1872–1950), nephew of the influential sociologist Émile Durkheim

David Émile Durkheim ( or ; 15 April 1858 – 15 November 1917) was a French sociologist. Durkheim formally established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited as one of the principal architects of modern social science, al ...

, to be the founder of the French anthropological tradition. Mauss belonged to Durkheim's '' Année Sociologique'' group. While Durkheim and others examined the state of modern societies, Mauss and his collaborators (such as Henri Hubert

Henri Hubert (23 June 1872 – 25 May 1927) was a French archaeologist and sociologist of comparative religion who is best known for his work on the Celts and his collaboration with Marcel Mauss and other members of the Année Sociologique.

L ...

and Robert Hertz

Robert Hertz (22 June 1881, Saint-Cloud, Hauts-de-Seine – 13 April 1915, Marchéville, Meuse) was a French sociologist who was killed in active service during World War I.

Hertz was a student at the École Normale Supérieure, from which he ag ...

) drew on ethnography and philology to analyze societies that were not as 'differentiated' as European nation states.

Two works by Mauss in particular proved to have enduring relevance: '' Essay on the Gift,'' a seminal analysis of exchange

Exchange may refer to:

Physics

*Gas exchange is the movement of oxygen and carbon dioxide molecules from a region of higher concentration to a region of lower concentration. Places United States

* Exchange, Indiana, an unincorporated community

* ...

and reciprocity

Reciprocity may refer to:

Law and trade

* Reciprocity (Canadian politics), free trade with the United States of America