History of aerial warfare on:

[Wikipedia]

[Google]

[Amazon]

The history of aerial warfare began in ancient times, with the use of

The story's world-conquering Prince, of boundless ambition and cruelty, orders "a magnificent ship to be constructed, with which he could sail through the air; it was gorgeously fitted out and of many colours; like the tail of a peacock, it was covered with thousands of eyes, but each eye was the barrel of a gun. The prince sat in the center of the ship, and had only to touch a spring in order to make thousands of bullets fly out in all directions, while the guns were at once loaded again". Later, the Prince develops an improved model, able to also fire "Steel Thunderbolts", and orders many thousands of them built to make up a massive air flotilla manned by his troops. H.G. Wells in ''

Th

Th

Declaration Prohibiting the Discharge of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons

part of the

In

In

p.1 resulting in German ''Leutnant''

By the time of the

By the time of the

Lessons learned were applied to the later

Lessons learned were applied to the later

The collapse of the

The collapse of the

During the

During the

Israel: Hezbollah Drone Attacks Warship

Washingtonpost.com. Retrieved 2008-01-10.

Official U.S. Army Aviation website

''World War I in photos: Aerial Warfare''

Aerial warfare

kites

A kite is a tethered heavier than air flight, heavier-than-air or lighter-than-air craft with wing surfaces that react against the air to create Lift (force), lift and Drag (physics), drag forces. A kite consists of wings, tethers and anchors. ...

in China

China, officially the People's Republic of China (PRC), is a country in East Asia. It is the world's most populous country, with a population exceeding 1.4 billion, slightly ahead of India. China spans the equivalent of five time zones and ...

. In the third century, it progressed to balloon

A balloon is a flexible bag that can be inflated with a gas, such as helium, hydrogen, nitrous oxide, oxygen, and air. For special tasks, balloons can be filled with smoke, liquid water, granular media (e.g. sand, flour or rice), or light so ...

warfare. Airplanes

An airplane or aeroplane (informally plane) is a fixed-wing aircraft that is propelled forward by thrust from a jet engine, propeller, or rocket engine. Airplanes come in a variety of sizes, shapes, and wing configurations. The broad spectr ...

were put to use for war starting in 1911, initially for reconnaissance, and then for aerial combat to shoot down the recon planes. The use of planes for strategic bombing emerged during World War II. Also during World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, Nazi Germany developed many missile

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket i ...

and precision-guided munition systems, including the first cruise missile, the first short-range ballistic missile, the first guided surface-to-air missiles, and the first anti-ship missiles. Ballistic missiles became of key importance during the Cold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

, were armed with nuclear warheads, and were stockpiled by the superpowers – the United States and the Soviet Union – to deter each other from using them.

Fictional predictions

Since early history, various cultures developed myths of flying gods and deities, some of whom such asZeus

Zeus or , , ; grc, Δῐός, ''Diós'', label=Genitive case, genitive Aeolic Greek, Boeotian Aeolic and Doric Greek#Laconian, Laconian grc-dor, Δεύς, Deús ; grc, Δέος, ''Déos'', label=Genitive case, genitive el, Δίας, ''D� ...

could throw thunderbolts from on high at earthbound humans. There were also fictions of humans finding ways to fly, such as the Greek Daedalus

In Greek mythology, Daedalus (, ; Greek: Δαίδαλος; Latin: ''Daedalus''; Etruscan: ''Taitale'') was a skillful architect and craftsman, seen as a symbol of wisdom, knowledge and power. He is the father of Icarus, the uncle of Perdix, an ...

and Icarus

In Greek mythology, Icarus (; grc, Ἴκαρος, Íkaros, ) was the son of the master craftsman Daedalus, the architect of the labyrinth of Crete. After Theseus, king of Athens and enemy of Minos, escaped from the labyrinth, King Minos suspe ...

. A logical combination was to imagine mundane humans flying - and making military use of their ability to fly. Imagination long preceded the technology needed for such warfare to be actually carried out.

In the third book of Jonathan Swift

Jonathan Swift (30 November 1667 – 19 October 1745) was an Anglo-Irish Satire, satirist, author, essayist, political pamphleteer (first for the Whig (British political party), Whigs, then for the Tories (British political party), Tories), poe ...

's ''Gulliver's Travels

''Gulliver's Travels'', or ''Travels into Several Remote Nations of the World. In Four Parts. By Lemuel Gulliver, First a Surgeon, and then a Captain of Several Ships'' is a 1726 prose satire by the Anglo-Irish writer and clergyman Jonathan ...

'' (1726), the King of the flying island of Laputa resorts to bombarding enemies and rebellious subjects with heavy rocks thrown from the air.

What might be the first detailed fictional depiction of what is now called an Air Force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

can be found in ''"The Wicked Prince"'' by Hans Christian Andersen

Hans Christian Andersen ( , ; 2 April 1805 – 4 August 1875) was a Danish author. Although a prolific writer of plays, travelogues, novels, and poems, he is best remembered for his literary fairy tales.

Andersen's fairy tales, consisti ...

(1840The story's world-conquering Prince, of boundless ambition and cruelty, orders "a magnificent ship to be constructed, with which he could sail through the air; it was gorgeously fitted out and of many colours; like the tail of a peacock, it was covered with thousands of eyes, but each eye was the barrel of a gun. The prince sat in the center of the ship, and had only to touch a spring in order to make thousands of bullets fly out in all directions, while the guns were at once loaded again". Later, the Prince develops an improved model, able to also fire "Steel Thunderbolts", and orders many thousands of them built to make up a massive air flotilla manned by his troops. H.G. Wells in ''

The War in the Air

''The War in the Air: And Particularly How Mr. Bert Smallways Fared While It Lasted'' is a military science fiction novel written by H. G. Wells.

The novel was written in four months in 1907, and was serialized and published in 1908 in ''The ...

'' (1907) grasped the full implications of aerial warfare and air power and how it would revolutionize warfare. Many of the book's predictions - such as the devastating strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

of cities or how bombing from the air would make surface dreadnoughts

The dreadnought (alternatively spelled dreadnaught) was the predominant type of battleship in the early 20th century. The first of the kind, the Royal Navy's , had such an impact when launched in 1906 that similar battleships built after her ...

obsolete in naval warfare - only came about in the Second World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

rather than the First The First may refer to:

* ''The First'' (album), the first Japanese studio album by South Korean boy group Shinee

* ''The First'' (musical), a musical with a book by critic Joel Siegel

* The First (TV channel), an American conservative opinion ne ...

which broke out a few years after the book's publication.

Kite warfare

The earliest documented aerial warfare took place inancient China

The earliest known written records of the history of China date from as early as 1250 BC, from the Shang dynasty (c. 1600–1046 BC), during the reign of king Wu Ding. Ancient historical texts such as the '' Book of Documents'' (early chapte ...

, when a manned kite

A man-lifting kite is a kite designed to lift a person from the ground. Historically, man-lifting kites have been used chiefly for reconnaissance. Interest in their development declined with the advent of powered flight at the beginning of the 20 ...

was set off to spy for military intelligence

Military intelligence is a military discipline that uses information collection and analysis approaches to provide guidance and direction to assist commanders in their decisions. This aim is achieved by providing an assessment of data from a ...

and communication.

Balloon warfare

Balloon warfare in ancient China

In or around the second or third century, a prototypehot air balloon

A hot air balloon is a lighter-than-air aircraft consisting of a bag, called an envelope, which contains heated air. Suspended beneath is a gondola or wicker basket (in some long-distance or high-altitude balloons, a capsule), which carries p ...

, the Kongming lantern

A sky lantern (), also known as Kǒngmíng lantern (), or Chinese lantern, is a small hot air balloon made of paper, with an opening at the bottom where a small fire is suspended.

In Asia and elsewhere around the world, sky lanterns have bee ...

, was invented in China, serving as a military communication station.

Balloon warfare in Europe

Some minor warfare use was made of balloons in the infancy of aeronautics. The first instance was by theFrench Aerostatic Corps

The French Aerostatic Corps or Company of Aeronauts (french: compagnie d'aérostiers) was the world's first balloon unit,Jeremy Beadle and Ian Harrison, ''First, Lasts & Onlys: Military'', p. 42 founded in 1794 to use balloons, primarily for reco ...

at the Battle of Fleurus in 1794, who used a tethered balloon, ''L'entreprenant'', to gain a vantage point.Cooksley (1997), p.6

Balloons had disadvantages. They could not fly in bad weather, fog, or high winds. They were at the mercy of the winds and were also very large targets.

Austrian use at Venice in 1849

The first aggressive use of balloons in warfare took place in 1849. Austrian imperial forces besieging Venice attempted to float some 200 paper hot air balloons each carrying a 24–30-pound (11–14 kg) bomb that was to be dropped from the balloon with a time fuse over the besieged city. The balloons were launched mainly from land; however, some were also launched from the side-wheel steamer SMS Vulcano that acted as a balloon carrier. The Austrians used smaller pilot balloons to determine the correct fuse settings. At least one bomb fell in the city; however, due to the wind changing after launch, most of the balloons missed their target, and some drifted back over Austrian lines and the launching ship Vulcano.American Civil War

Union Army Balloon Corps

The American Civil War was the first war to witness significant use of aeronautics in support of battle. Thaddeus Lowe made noteworthy contributions to the Union war effort using a fleet of balloons he createdGross (2002), p.13 In June 1861 professor Thaddeus S. C. Lowe left his work in the private sector and offered his services as an Aeronaut to President Lincoln, who took some interest in the idea of an air war. Lowe's demonstration of flying a balloon over Washington, DC, and transmitting a telegraph message to the ground was enough to have him introduced to the commanders of the topographical engineers; initially it was thought balloons could be used for preparing better maps. Lowe's first action was a free flight observation of theConfederate

Confederacy or confederate may refer to:

States or communities

* Confederate state or confederation, a union of sovereign groups or communities

* Confederate States of America, a confederation of secessionist American states that existed between 1 ...

positions at the First Battle of Bull Run

The First Battle of Bull Run (the name used by Union forces), also known as the Battle of First Manassas

in July 1861.Boyne (2003), p.395

Lowe was called to Fort Corcoran and ascended in order to spot rebel encampments.

Collier (1974), p.11 With flag signals he directed artillery fire on the rebels.

Lowe and other balloonists formed the Union Army Balloon Corps

The Union Army Balloon Corps was a branch of the Union Army during the American Civil War, established by presidential appointee Thaddeus S. C. Lowe. It was organized as a civilian operation, which employed a group of prominent American aeronauts ...

. Lowe insisted on the strict use of tether

A tether is a cord, fixture, or flexible attachment that characteristically anchors something movable to something fixed; it also maybe used to connect two movable objects, such as an item being towed by its tow.

Applications for tethers includ ...

ed (as opposed to free) flight because of concern about being shot down over enemy lines and punished as spies. By attaining altitudes from to as much as 3½ miles, an expansive view of the battle field and beyond could be had.

As the Confederates retreated, the war turned into the Peninsular Campaign. Due to the heavy forests on the peninsula, the balloons were unable to follow on land so a coal barge was converted to operate the balloons. The balloons and their gas generators were loaded aboard and taken down the Potomac, where reconnaissance of the peninsula could continue.

At the Battle of Fair Oaks

The Battle of Seven Pines, also known as the Battle of Fair Oaks or Fair Oaks Station, took place on May 31 and June 1, 1862, in Henrico County, Virginia, nearby Sandston, as part of the Peninsula Campaign of the American Civil War. It was th ...

, Lowe was able to view the enemy army advancing and sent a dispatch to have reserves sent.

The balloon corps was later assigned to the engineers corps.Boyne (2003), p.398 By August 1863, the Union Army Balloon Corps was disbanded.Buckley (1999), p.24

Confederate Army

TheConfederate Army

The Confederate States Army, also called the Confederate Army or the Southern Army, was the military land force of the Confederate States of America (commonly referred to as the Confederacy) during the American Civil War (1861–1865), fighting ...

also made use of balloons, but they were gravely hampered by lack of supplies due to embargoes. They were forced to fashion their balloons from colored silk

Silk is a natural protein fiber, some forms of which can be woven into textiles. The protein fiber of silk is composed mainly of fibroin and is produced by certain insect larvae to form cocoons. The best-known silk is obtained from the coc ...

dress-making material, and their use was limited by the infrequent supply of gas in Richmond, Virginia

(Thus do we reach the stars)

, image_map =

, mapsize = 250 px

, map_caption = Location within Virginia

, pushpin_map = Virginia#USA

, pushpin_label = Richmond

, pushpin_m ...

. By the summer of 1863, all balloon reconnaissance of the American Civil War had ceased.

Before World War I

Th

ThDeclaration Prohibiting the Discharge of Projectiles and Explosives from Balloons

part of the

1907 Hague Convention

The Hague Conventions of 1899 and 1907 are a series of international treaty, treaties and declarations negotiated at two international peace conferences at The Hague in the Netherlands. Along with the Geneva Conventions, the Hague Conventions w ...

ratified by the United States, Great Britain and China, outlawed aircraft ordnance

Aircraft ordnance or ordnance (in the context of military aviation) is weapons (e.g. bombs, missiles, rockets and gun ammunition) used by aircraft. The term is often used when describing the weight of air-to-ground weaponry that can be carried ...

and aerial bombing

An airstrike, air strike or air raid is an offensive operation carried out by aircraft. Air strikes are delivered from aircraft such as blimps, balloons, Fighter aircraft, fighters, bomber, heavy bombers, ground attack aircraft, attack helicopter ...

.

The United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

showed interest in naval aviation from the turn of the 20th century. In August 1910 Jacob Earl Fickel conducted his first experiments with Glenn Curtiss

Glenn Hammond Curtiss (May 21, 1878 – July 23, 1930) was an American aviation and motorcycling pioneer, and a founder of the U.S. aircraft industry. He began his career as a bicycle racer and builder before moving on to motorcycles. As early ...

- shooting a gun from an airplane. In 1910–1911 the Navy conducted experiments which proved the practicality of carrier-based aviation. On November 14, 1910, near Hampton Roads, Virginia

Hampton Roads is the name of both a body of water in the United States that serves as a wide channel for the James, Nansemond and Elizabeth rivers between Old Point Comfort and Sewell's Point where the Chesapeake Bay flows into the Atlantic O ...

, civilian pilot Eugene Ely

Eugene Burton Ely (October 21, 1886 – October 19, 1911) was an American aviation pioneer, credited with the first shipboard aircraft take off and landing.

Background

Ely was born in Williamsburg, Iowa, and raised in Davenport, Iowa. Having c ...

took off from a wooden platform installed on the scout cruiser ''USS Birmingham'' (CL-2). He landed safely on shore a few minutes later. Ely proved several months later that it was also possible to land on a ship. On January 18, 1911, he landed on a platform attached to the American cruiser ''USS Pennsylvania'' (ACR-4) in San Francisco

San Francisco (; Spanish language, Spanish for "Francis of Assisi, Saint Francis"), officially the City and County of San Francisco, is the commercial, financial, and cultural center of Northern California. The city proper is the List of Ca ...

harbor.

The first use of airplanes in an actual war occurred in the 1911 Italo-Turkish War

The Italo-Turkish or Turco-Italian War ( tr, Trablusgarp Savaşı, "Tripolitanian War", it, Guerra di Libia, "War of Libya") was fought between the Kingdom of Italy and the Ottoman Empire from 29 September 1911, to 18 October 1912. As a result o ...

with Italian Army Air Corps Blériot XI

The Blériot XI is a French aircraft of the pioneer era of aviation. The first example was used by Louis Blériot to make the first flight across the English Channel in a heavier-than-air aircraft, on 25 July 1909. This is one of the most fam ...

and Nieuport IV

The Nieuport IV was a French-built sporting, training and reconnaissance monoplane of the early 1910s.

Design and development

Societe Anonyme des Etablissements Nieuport was formed in 1909 by Édouard Nieuport. The Nieuport IV was a developm ...

monoplanes bombing a Turkish camp at Ain Zara

Ain Zara is a town and oasis in western Libya, located in the region of Tripolitania.

History

In ancient times it was an important agricultural center. In the surroundings of Ain Zara, remnants of a fourth-century Christian necropolis are located ...

in Libya

Libya (; ar, ليبيا, Lībiyā), officially the State of Libya ( ar, دولة ليبيا, Dawlat Lībiyā), is a country in the Maghreb region in North Africa. It is bordered by the Mediterranean Sea to the north, Egypt to Egypt–Libya bo ...

. In the First Balkan War

The First Balkan War ( sr, Први балкански рат, ''Prvi balkanski rat''; bg, Балканска война; el, Αʹ Βαλκανικός πόλεμος; tr, Birinci Balkan Savaşı) lasted from October 1912 to May 1913 and invo ...

(1912) the Bulgarian Air Force

The Bulgarian Air Force ( bg, Военновъздушни сили, Voennovazdushni sili) is one of the three branches of the Military of Bulgaria, the other two being the Bulgarian Navy and Bulgarian land forces. Its mission is to guard and p ...

bombed Turkish positions at Adrianople, while the Greek Aviation performed, over the Dardanelles

The Dardanelles (; tr, Çanakkale Boğazı, lit=Strait of Çanakkale, el, Δαρδανέλλια, translit=Dardanéllia), also known as the Strait of Gallipoli from the Gallipoli peninsula or from Classical Antiquity as the Hellespont (; ...

, the first naval/air co-operation mission in history.

The United States Army

The United States Army (USA) is the land service branch of the United States Armed Forces. It is one of the eight U.S. uniformed services, and is designated as the Army of the United States in the U.S. Constitution.Article II, section 2, cla ...

used airplanes for scouting and communications in its 1916-1917 campaign against Pancho Villa

Francisco "Pancho" Villa (,"Villa"

''Collins English Dictionary''. ; ;

. Air ''Collins English Dictionary''. ; ;

reconnaissance

In military operations, reconnaissance or scouting is the exploration of an area by military forces to obtain information about enemy forces, terrain, and other activities.

Examples of reconnaissance include patrolling by troops (skirmisher ...

was carried out in both wars too. The air-dropped bomb was extensively used during the First Balkan War (including in the first night-bombing on 7 November 1912), and subsequently used by the Imperial German Air Service

Imperial is that which relates to an empire, emperor, or imperialism.

Imperial or The Imperial may also refer to:

Places

United States

* Imperial, California

* Imperial, Missouri

* Imperial, Nebraska

* Imperial, Pennsylvania

* Imperial, Texas ...

during World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

.

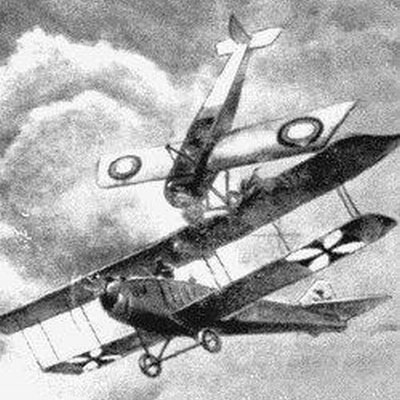

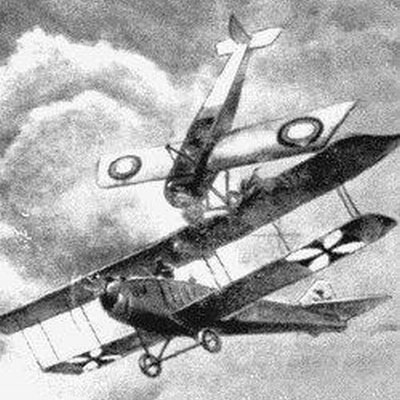

World War I

In

In World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, the United States, and the Ottoman Empire, with fightin ...

both sides initially made use of tethered balloons and airplanes for observation purposes, both for information gathering and directing of artillery

Artillery is a class of heavy military ranged weapons that launch munitions far beyond the range and power of infantry firearms. Early artillery development focused on the ability to breach defensive walls and fortifications during siege ...

fire. At first, enemy pilots simply exchanged hand waves, but a desire to prevent enemy observation led to airplane pilots attacking other airplanes and balloons, initially with small arms carried in the cockpit.Buckley (1999), pp.50,51

The addition of deflector plates to the back of propellers by French pilot Roland Garros and designer Raymond Saulnier in the Morane-Saulnier monoplane was the first example of an aircraft able to fire through its propeller, permitting Garros to score three victories in April 1915. Dutch aircraft designer Anthony Fokker

Anton Herman Gerard "Anthony" Fokker (6 April 1890 – 23 December 1939) was a Dutch aviation pioneer, aviation entrepreneur, aircraft designer, and aircraft manufacturer. He produced fighter aircraft in Germany during the First World War such ...

developed a successful gun synchronizer in 1915,

Buckley (1999), pp.51,52

Warplanep.1 resulting in German ''Leutnant''

Kurt Wintgens

''Leutnant'' Kurt Wintgens (1 August 1894 – 25 September 1916) was a German World War I fighter ace. He was the first military fighter pilot to score a victory over an opposing aircraft, while piloting an aircraft armed with a synchronized mac ...

scoring the first known victory for a synchronized gun-equipped fighter aircraft, on July 1, 1915.

The Allies

An alliance is a relationship among people, groups, or states that have joined together for mutual benefit or to achieve some common purpose, whether or not explicit agreement has been worked out among them. Members of an alliance are called ...

quickly developed their own synchronization gears, leading to the birth of ''aerial combat'', more commonly known as dogfight

A dogfight, or dog fight, is an aerial battle between fighter aircraft conducted at close range. Dogfighting first occurred in Mexico in 1913, shortly after the invention of the airplane. Until at least 1992, it was a component in every majo ...

ing. Tactics for dogfighting evolved by trial and error. The German ace Oswald Boelcke

Oswald Boelcke PlM (; 19 May 1891 – 28 October 1916) was a World War I German professional soldier and pioneering flying ace credited with 40 aerial victories. Boelcke is honored as the father of the German fighter air force, and of air ...

created eight essential rules of dogfighting, the ''Dicta Boelcke

The ''Dicta Boelcke'' is a list of fundamental aerial maneuvers of aerial combat formulated by First World War German flying ace Oswald Boelcke. Equipped with one of the first fighter aircraft, Boelcke became Germany's foremost flying ace durin ...

''.

Both sides also made use of aircraft for bombing

A bomb is an explosive weapon that uses the exothermic reaction of an explosive material to provide an extremely sudden and violent release of energy. Detonations inflict damage principally through ground- and atmosphere-transmitted mechanica ...

, strafing

Strafing is the military practice of attacking ground targets from low-flying aircraft using aircraft-mounted automatic weapons.

Less commonly, the term is used by extension to describe high-speed firing runs by any land or naval craft such ...

, maritime reconnaissance {{Unreferenced, date=March 2008

Maritime patrol is the task of monitoring areas of water. Generally conducted by military and law enforcement agencies, maritime patrol is usually aimed at identifying human activities.

Maritime patrol refers to ac ...

, antisubmarine warfare

Anti-submarine warfare (ASW, or in older form A/S) is a branch of underwater warfare that uses surface warships, aircraft, submarines, or other platforms, to find, track, and deter, damage, or destroy enemy submarines. Such operations are typic ...

, and the dropping of propaganda

Propaganda is communication that is primarily used to influence or persuade an audience to further an agenda, which may not be objective and may be selectively presenting facts to encourage a particular synthesis or perception, or using loaded ...

. The German military made use of Zeppelin

A Zeppelin is a type of rigid airship named after the German inventor Count Ferdinand von Zeppelin () who pioneered rigid airship development at the beginning of the 20th century. Zeppelin's notions were first formulated in 1874Eckener 1938, pp ...

s and, later on, bombers such as the Gotha

Gotha () is the fifth-largest city in Thuringia, Germany, west of Erfurt and east of Eisenach with a population of 44,000. The city is the capital of the district of Gotha and was also a residence of the Ernestine Wettins from 1640 until the ...

, to drop bombs on Southern England

Southern England, or the South of England, also known as the South, is an area of England consisting of its southernmost part, with cultural, economic and political differences from the Midlands and the North. Officially, the area includes G ...

. By the end of the war airplanes had become specialized into bombers, fighters, and observation (reconnaissance) aircraft. By 1916, aerial combat had already progressed to the point where dogfighting tactics based on such doctrines as the ''Dicta Boelcke'' allowed air supremacy

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of com ...

to be achieved. During the course of the war, new designs led to air supremacy shifting back and forth between the Germans and Allies.

Interwar period

Between 1918 and 1939 aircraft technology developed very rapidly. In 1918 most aircraft were biplanes with wooden frames, canvas skins, wire rigging and air-cooled engines. Biplanes continued to be the mainstay of air forces around the world and were used extensively in conflicts such as theSpanish Civil War

The Spanish Civil War ( es, Guerra Civil Española)) or The Revolution ( es, La Revolución, link=no) among Nationalists, the Fourth Carlist War ( es, Cuarta Guerra Carlista, link=no) among Carlists, and The Rebellion ( es, La Rebelión, lin ...

. Most industrial countries also created air force

An air force – in the broadest sense – is the national military branch that primarily conducts aerial warfare. More specifically, it is the branch of a nation's armed services that is responsible for aerial warfare as distinct from an a ...

s separate from the army and navy. However, by 1939 military biplanes were in the process of being replaced with metal framed monoplane

A monoplane is a fixed-wing aircraft configuration with a single mainplane, in contrast to a biplane or other types of multiplanes, which have multiple planes.

A monoplane has inherently the highest efficiency and lowest drag of any wing confi ...

s, often with stressed skins and liquid-cooled engines. Top speeds had tripled; altitudes doubled; ranges and payloads of bombers increased enormously.

Some theorists, especially in Britain

Britain most often refers to:

* The United Kingdom, a sovereign state in Europe comprising the island of Great Britain, the north-eastern part of the island of Ireland and many smaller islands

* Great Britain, the largest island in the United King ...

, considered that aircraft would become the dominant military arm in the future. They imagined that a future war would be won entirely by the destruction of the enemy's military and industrial capability from the air. The Italian general Giulio Douhet

General Giulio Douhet (30 May 1869 – 15 February 1930) was an Italian general and air power theorist. He was a key proponent of strategic bombing in aerial warfare. He was a contemporary of the 1920s air warfare advocates Walther Wever, Billy ...

, author of ''The Command of the Air'', was a seminal theorist of this school, which has been associated with Stanley Baldwin

Stanley Baldwin, 1st Earl Baldwin of Bewdley, (3 August 186714 December 1947) was a British Conservative Party politician who dominated the government of the United Kingdom between the world wars, serving as prime minister on three occasions, ...

's statement that "the bomber will always get through

"The bomber will always get through" was a phrase used by Stanley Baldwin in a 1932 speech "A Fear for the Future" given to the British Parliament. His speech stated that contemporary bomber aircraft had the performance necessary to conduct a s ...

"; that is, regardless of air defences, sufficient raiders will survive to rain destruction on the enemy's cities. This led to what would later be called a strategy of deterrence

Deterrence may refer to:

* Deterrence theory, a theory of war, especially regarding nuclear weapons

* Deterrence (penology), a theory of justice

* Deterrence (psychology)

Deterrence in relation to criminal offending is the idea or theory that t ...

and a "bomber gap", as nations measured air force power by number of bombers.

Others, such as General Billy Mitchell

William Lendrum Mitchell (December 29, 1879 – February 19, 1936) was a United States Army officer who is regarded as the father of the United States Air Force.

Mitchell served in France during World War I and, by the conflict's end, command ...

in the United States, saw the potential of air power to augment the striking power of naval surface fleets.Buckley (1999), p.91 German and British pilots had experimented with aerial bombing of ships and air-dropped torpedoes during World War I with mixed results. The vulnerability of capital ships to aircraft was demonstrated on 21 July 1921 when a squadron of bombers commanded by General Mitchell sank the ex-German battleship SMS ''Ostfriesland'' with aerial bombs; although the ''Ostfriesland'' was stationary and defenseless during the exercise, its destruction demonstrated the potency of air planes against ships.

It was during the Banana Wars

The Banana Wars were a series of conflicts that consisted of military occupation, police action, and intervention by the United States in Central America and the Caribbean between the end of the Spanish–American War in 1898 and the inception ...

, while fighting bandits, freedom fighters and insurgents in places like Haiti

Haiti (; ht, Ayiti ; French: ), officially the Republic of Haiti (); ) and formerly known as Hayti, is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean Sea, east of Cuba and Jamaica, and ...

, the Dominican Republic

The Dominican Republic ( ; es, República Dominicana, ) is a country located on the island of Hispaniola in the Greater Antilles archipelago of the Caribbean region. It occupies the eastern five-eighths of the island, which it shares wit ...

and Nicaragua

Nicaragua (; ), officially the Republic of Nicaragua (), is the largest country in Central America, bordered by Honduras to the north, the Caribbean to the east, Costa Rica to the south, and the Pacific Ocean to the west. Managua is the cou ...

that United States Marine Corps

The United States Marine Corps (USMC), also referred to as the United States Marines, is the maritime land force service branch of the United States Armed Forces responsible for conducting expeditionary and amphibious operations through combi ...

aviators began to experiment with air-ground tactics to support Marines on the ground. In Haiti the Marines began to experiment with dive bombing

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact throughou ...

and in Nicaragua where they began to perfect it. While other nations and services had tried variations of this technique, Marine aviators were the first to include it in their tactical doctrine.

Germany was banned from possessing an air force by the terms of the World War I armistice. The German military continued to train its soldiers as pilots clandestinely until Hitler

Adolf Hitler (; 20 April 188930 April 1945) was an Austrian-born German politician who was dictator of Germany from 1933 until his death in 1945. He rose to power as the leader of the Nazi Party, becoming the chancellor in 1933 and then ...

was ready to openly defy the ban. This was done by forming the ''Deutscher Luftsportverband

The German Air Sports Association (''Deutscher Luftsportverband'', or DLV e. V.) was an organisation set up by the Nazi Party in March 1933 to establish a uniform basis for the training of military pilots. Its chairman was Hermann Göring and its v ...

'', a flying enthusiast's club, and training pilots as civilians, and some German pilots were even sent to the Soviet Union

The Soviet Union,. officially the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics. (USSR),. was a transcontinental country that spanned much of Eurasia from 1922 to 1991. A flagship communist state, it was nominally a federal union of fifteen national ...

for secret training; a trained air force was thus ready as soon as the word was given. This was the beginning of the ''Luftwaffe''.

World War II

Military aviation came into its own during theSecond World War

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. The increased performance, range, and payload of contemporary aircraft meant that air power could move beyond the novelty applications of World War I, becoming a central striking force for all the combatant nations.

Over the course of the war, several distinct roles emerged for the application of air power.

Strategic bombing

Strategic bombing

Strategic bombing is a military strategy used in total war with the goal of defeating the enemy by destroying its morale, its economic ability to produce and transport materiel to the theatres of military operations, or both. It is a systematica ...

of civilian targets from the air was first proposed by the Italian theorist General Giulio Douhet

General Giulio Douhet (30 May 1869 – 15 February 1930) was an Italian general and air power theorist. He was a key proponent of strategic bombing in aerial warfare. He was a contemporary of the 1920s air warfare advocates Walther Wever, Billy ...

. In his book ''The Command of the Air'' (1921), Douhet argued future military leaders could avoid falling into bloody World War I–style trench stalemates by using aviation to strike past the enemy's forces directly at their vulnerable civilian populations. Douhet believed such strikes would cause these populations to force their governments to surrender.

Douhet's ideas were paralleled by other military theorists who emerged from World War I, including Sir Hugh Trenchard

Marshal of the Royal Air Force Hugh Montague Trenchard, 1st Viscount Trenchard, (3 February 1873 – 10 February 1956) was a British officer who was instrumental in establishing the Royal Air Force. He has been described as the "Father of the ...

in Britain. In the interwar period, Britain and the United States became the most enthusiastic supporters of the strategic bombing theory, with each nation building specialized heavy bombers specifically for this task.

;Japanese strategic bombing

Strategic bombing, mostly targeting large Chinese cities, was independently conducted during the Second Sino-Japanese war

The Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945) or War of Resistance (Chinese term) was a military conflict that was primarily waged between the Republic of China and the Empire of Japan. The war made up the Chinese theater of the wider Pacific Th ...

and World War II by the Imperial Japanese Navy Air Service

The was the Naval aviation, air arm of the Imperial Japanese Navy (IJN). The organization was responsible for the operation of naval aircraft and the conduct of aerial warfare in the Pacific War.

The Japanese military acquired their first air ...

and the Imperial Japanese Army Air Service

The Imperial Japanese Army Air Service (IJAAS) or Imperial Japanese Army Air Force (IJAAF; ja, 大日本帝國陸軍航空部隊, Dainippon Teikoku Rikugun Kōkūbutai, lit=Greater Japan Empire Army Air Corps) was the aviation force of the Im ...

. There were also air raids on Philippines

The Philippines (; fil, Pilipinas, links=no), officially the Republic of the Philippines ( fil, Republika ng Pilipinas, links=no),

* bik, Republika kan Filipinas

* ceb, Republika sa Pilipinas

* cbk, República de Filipinas

* hil, Republ ...

and Australia

Australia, officially the Commonwealth of Australia, is a Sovereign state, sovereign country comprising the mainland of the Australia (continent), Australian continent, the island of Tasmania, and numerous List of islands of Australia, sma ...

, as well as the cities in Burma and Malaysia. The Navy and Army air services used tactical bombing against ships and military positions, as at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

.

;Luftwaffe

In the early days of World War II, the Luftwaffe

The ''Luftwaffe'' () was the aerial-warfare branch of the German ''Wehrmacht'' before and during World War II. Germany's military air arms during World War I, the ''Luftstreitkräfte'' of the Imperial Army and the '' Marine-Fliegerabtei ...

launched devastating air attacks against besieged cities. During the Battle of Britain

The Battle of Britain, also known as the Air Battle for England (german: die Luftschlacht um England), was a military campaign of the Second World War, in which the Royal Air Force (RAF) and the Fleet Air Arm (FAA) of the Royal Navy defende ...

, the ''Luftwaffe'', frustrated in its attempts to gain air superiority

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of c ...

, turned to bombing British cities. However, these raids did not have the effect predicted by prewar theorists.

;Soviet Red Air Force

Although the rapid industrialization the Soviet Union experienced in the 1930s had the potential to enable the Soviet Air Forces

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

to be effective against the Luftwaffe, Stalin's purges

The Great Purge or the Great Terror (russian: Большой террор), also known as the Year of '37 (russian: 37-й год, translit=Tridtsat sedmoi god, label=none) and the Yezhovshchina ('period of Yezhov'), was Soviet General Secreta ...

left the organization weakened. However, when Germany invaded in June 1941, the size of the Soviet Air Forces allowed it to absorb horrendous casualties and still maintain capability. Despite the near collapse of Soviet forces in 1941, they survived, as German forces outran their supply lines and the Americans and British provided Lend Lease

Lend-Lease, formally the Lend-Lease Act and introduced as An Act to Promote the Defense of the United States (), was a policy under which the United States supplied the United Kingdom, the Soviet Union and other Allied nations with food, oil, ...

assistance.

Although strategic bombing requires that the enemy's industrial war capacity be neutralized, some Soviet factories were moved far out of reach of the Luftwaffe's bombers.Boyne (2003), pp.220,221 Because the Luftwaffe's resources were needed to support the German army, the Luftwaffe became overstretched, and even victorious battles degraded Germany's air force due to attrition. By 1943, the Soviets were able to produce considerably more airplanes than their German rivals; for example, at Kursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German stru ...

, the Soviets had twice the number of airplanes that the Luftwaffe had. Utilizing overwhelming numerical superiority, Soviet forces were able to drive the Germans out of Soviet territory and take the war to Germany.

;Allied air forces in Europe

The British started a strategic bombing campaign in 1940 that was to last for the rest of the war. Early British bombers were all twin-engined designs, and the 1939 Battle of the Heligoland Bight had shown the vulnerability of bombers to fighter attack. Therefore, RAF Bomber Command

RAF Bomber Command controlled the Royal Air Force's bomber forces from 1936 to 1968. Along with the United States Army Air Forces, it played the central role in the strategic bombing of Germany in World War II. From 1942 onward, the British bo ...

turned to a policy of area bombing at night. Later in the war pathfinder

Pathfinder may refer to:

Businesses

* Pathfinder Energy Services, a division of Smith International

* Pathfinder Press, a publisher of socialist literature

Computing and information science

* Path Finder, a Macintosh file browser

* Pathfinder ( ...

tactics, radio location

Radiolocation, also known as radiolocating or radiopositioning, is the process of finding the location of something through the use of radio waves. It generally refers to passive uses, particularly radar—as well as detecting buried cables, w ...

, ground mapping radar, and very low-level bombing enabled specific targets to be attacked.

When the USAAF arrived in England in 1942, the Americans were convinced they could carry out successful daylight raids. The U.S. Eighth Air Force

The Eighth Air Force (Air Forces Strategic) is a numbered air force (NAF) of the United States Air Force's Air Force Global Strike Command (AFGSC). It is headquartered at Barksdale Air Force Base, Louisiana. The command serves as Air Force ...

was equipped with high-altitude four-engined designs. The new bombers also featured a stronger defensive armament. Flying in daylight in large formations, U.S. doctrine held tactical formations of heavy bombers would be sufficient to gain air superiority

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of c ...

without escort fighters. The intended raids would hit hard on chokepoints in the German war economy

A war economy or wartime economy is the set of contingencies undertaken by a modern state to mobilize its economy for war production. Philippe Le Billon describes a war economy as a "system of producing, mobilizing and allocating resources t ...

such as oil refineries

An oil refinery or petroleum refinery is an industrial process plant where petroleum (crude oil) is transformed and refined into useful products such as gasoline (petrol), diesel fuel, asphalt base, fuel oils, heating oil, kerosene, liquefie ...

or ball bearing

A ball bearing is a type of rolling-element bearing that uses balls to maintain the separation between the bearing races.

The purpose of a ball bearing is to reduce rotational friction and support radial and axial loads. It achieves this ...

factories.Gross (2002), p.113

The USAAF was compelled to change its doctrine since bombers alone, no matter how heavily armed, could not achieve air superiority against single-engined fighters. In a series of missions in 1943 that penetrated beyond the range of fighter cover, there were loss rates up to twenty percent. The Allies lost 160,000 airmen and 33,700 planes during World War II, and almost 68,000 U.S. airmen died.

;Air superiority

During the Battle of Britain, many of the best ''Luftwaffe'' pilots had been forced to bail out over British soil, where they were captured. As the quality of the ''Luftwaffe'' fighter arm decreased, the Americans introduced the long-range escort fighter

The escort fighter was a concept for a fighter aircraft designed to escort bombers to and from their targets. An escort fighter needed range long enough to reach the target, loiter over it for the duration of the raid to defend the bombers, and r ...

s, carrying drop tanks such as the North American P-51 Mustang

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter aircraft, fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and the Korean War, among other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in April 1940 by a team ...

. Newer, inexperienced German pilots—flying potentially superior aircraft, gradually became less and less effective at thinning the late-war bomber stream

The bomber stream was a saturation attack tactic developed by the Royal Air Force (RAF) Bomber Command to overwhelm the nighttime German aerial defences of the Kammhuber Line during World War II.

The Kammhuber Line consisted of three layers of ...

s. Adding fighters to the daylight raids gave the bombers much-needed protection and greatly improved the impact of the strategic bombing effort.

Over time, from 1942 to 1944, the Allies' air forces became stronger while the Luftwaffe weakened. During 1944, Germany's air force lost control of Germany's skies. As a result, nothing in Germany could be protected whether it was army units, factories, civilians in cities, or even the nation's capital. German soldiers and civilians began to be slaughtered in the thousands by aerial bombardment.

;Effectiveness

Strategic bombing by non-atomic means did not however win the war for the Allies, nor did it succeed in breaking the will to resist of the German (and Japanese) people. But in the words of the German armaments minister Albert Speer

Berthold Konrad Hermann Albert Speer (; ; 19 March 1905 – 1 September 1981) was a German architect who served as the Minister of Armaments and War Production in Nazi Germany during most of World War II. A close ally of Adolf Hitler, he ...

, it created "a second front in the air." Speer succeeded in increasing the output of armaments right up to mid-1944 in spite of the bombing. Still, the war against the British and American bombers demanded enormous amounts of resources: antiaircraft guns, day and night fighters, radars, searchlights, manpower, ammunition, and fuel.

On the Allied side, strategic bombing diverted material resources, equipment (such as radar

Radar is a detection system that uses radio waves to determine the distance (''ranging''), angle, and radial velocity of objects relative to the site. It can be used to detect aircraft, ships, spacecraft, guided missiles, motor vehicles, w ...

) aircraft, and manpower away from the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

and Allied armies. As a result, German army groups in Russia, Italy, and France rarely saw friendly aircraft and constantly ran short of tanks, trucks, and anti-tank weapons.

;U.S. Bombing of Japan

In June 1944, Boeing B-29 Superfortress

The Boeing B-29 Superfortress is an American four-engined propeller-driven heavy bomber, designed by Boeing and flown primarily by the United States during World War II and the Korean War. Named in allusion to its predecessor, the B-17 Fl ...

es launched from China, bombed Japanese factories. From November 1944, increasingly intense raids were launched from bases closer to Japan. Tactics evolved from high-altitude to lower altitude attacks, largely removing most defensive guns and switching to incendiary bombs. These attacks devastated many Japanese cities.

In August 1945, B-29 Superfortresses dropped atomic bombs

A nuclear weapon is an explosive device that derives its destructive force from nuclear reactions, either fission (fission bomb) or a combination of fission and fusion reactions ( thermonuclear bomb), producing a nuclear explosion. Both bomb ...

on Hiroshima and Nagasaki

The United States detonated two atomic bombs over the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki on 6 and 9 August 1945, respectively. The two bombings killed between 129,000 and 226,000 people, most of whom were civilians, and remain the onl ...

while the Soviets invaded Manchuria. The Japanese then surrendered unconditionally, officially ending World War II.

Tactical air support

By contrast with the British strategists, the primary purpose of the ''Luftwaffe'' was to support the Army. This accounted for the presence of large numbers of medium bombers anddive bomber

A dive bomber is a bomber aircraft that dives directly at its targets in order to provide greater accuracy for the bomb it drops. Diving towards the target simplifies the bomb's trajectory and allows the pilot to keep visual contact througho ...

s on strength and the scarcity of long-range heavy bombers. This 'flying artillery' greatly assisted in the successes of the German Army in the Battle of France

The Battle of France (french: bataille de France) (10 May – 25 June 1940), also known as the Western Campaign ('), the French Campaign (german: Frankreichfeldzug, ) and the Fall of France, was the Nazi Germany, German invasion of French Third Rep ...

(1940) . Hitler determined air superiority was essential for the invasion of Britain

The term Invasion of England may refer to the following planned or actual invasions of what is now modern England, successful or otherwise.

Pre-English Settlement of parts of Britain

* The 55 and 54 BC Caesar's invasions of Britain.

* The 43 AD ...

. When this was not achieved in the Battle of Britain, the invasion was canceled, making this the first major battle whose outcome was determined primarily in the air.

The war in Russia forced the Luftwaffe to devote the majority of its resources to providing tactical air support for the beleaguered German army. In that role, the Luftwaffe used the Junkers Ju 87

The Junkers Ju 87 or Stuka (from ''Sturzkampfflugzeug'', "dive bomber") was a German dive bomber and ground-attack aircraft. Designed by Hermann Pohlmann, it first flew in 1935. The Ju 87 made its combat debut in 1937 with the Luftwaffe's Con ...

, Henschel Hs 123

The Henschel Hs 123 was a single-seat biplane dive bomber and close-support attack aircraft flown by the German ''Luftwaffe'' during the Spanish Civil War and the early to midpoint of World War II. It proved to be robust, durable and effective e ...

and modified fighters such as Messerschmitt Bf 109

The Messerschmitt Bf 109 is a German World War II fighter aircraft that was, along with the Focke-Wulf Fw 190, the backbone of the Luftwaffe's fighter force. The Bf 109 first saw operational service in 1937 during the Spanish Civil War an ...

s and Focke-Wulf Fw 190

The Focke-Wulf Fw 190, nicknamed ''Würger'' (" Shrike") is a German single-seat, single-engine fighter aircraft designed by Kurt Tank at Focke-Wulf in the late 1930s and widely used during World War II. Along with its well-known counterpart, ...

s.

The Red Air Force was also primarily used in the tactical support role, and towards the end of the war was very effective in the support of the Red Army

The Workers' and Peasants' Red Army (Russian: Рабо́че-крестья́нская Кра́сная армия),) often shortened to the Red Army, was the army and air force of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic and, after ...

in its advance across Eastern Europe

Eastern Europe is a subregion of the Europe, European continent. As a largely ambiguous term, it has a wide range of geopolitical, geographical, ethnic, cultural, and socio-economic connotations. The vast majority of the region is covered by Russ ...

. An aircraft of major importance to the Soviets was the ''Ilyushin Il-2

The Ilyushin Il-2 (Russian: Илью́шин Ил-2) is a ground-attack plane that was produced by the Soviet Union in large numbers during the Second World War. The word ''shturmovík'' (Cyrillic: штурмовик), the generic Russian term ...

Sturmovik'' "flying artillery" which made life very difficult for panzer

This article deals with the tanks (german: panzer) serving in the German Army (''Deutsches Heer'') throughout history, such as the World War I tanks of the Imperial German Army, the interwar and World War II tanks of the Nazi German Wehrmacht, ...

crews, and the Il-2 played an important part in the Soviet victory in one of the biggest tank battles in history at Kursk

Kursk ( rus, Курск, p=ˈkursk) is a city and the administrative center of Kursk Oblast, Russia, located at the confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym rivers. The area around Kursk was the site of a turning point in the Soviet–German stru ...

.

Military transport and use of airborne troops

Military transport was invaluable to all sides in maintaining supply and communications of ground troops, and was used on many notable occasions such as resupply of German troops in and around Stalingrad afterOperation Uranus

Operation Uranus (russian: Опера́ция «Ура́н», Operatsiya "Uran") was the codename of the Soviet Red Army's 19–23 November 1942 strategic operation on the Eastern Front of World War II which led to the encirclement of Axis ...

, and employment of airborne troops

Airborne forces, airborne troops, or airborne infantry are ground combat units carried by aircraft and airdropped into battle zones, typically by parachute drop or air assault. Parachute-qualified infantry and support personnel serving in ai ...

.Boyne (2003), p.221 After the first trials in use of airborne troops by the Red Army displayed in the early 1930s many European nations and Japan also formed airborne troops, and these saw extensive service on in all theatres of the Second World War.

However their effectiveness as shock troops

Shock troops or assault troops are formations created to lead an attack. They are often better trained and equipped than other infantry, and expected to take heavy casualties even in successful operations.

"Shock troop" is a calque, a loose tra ...

employed to surprise enemy static troops proved to be of limited success. Most airborne troops served as light infantry

Light infantry refers to certain types of lightly equipped infantry throughout history. They have a more mobile or fluid function than other types of infantry, such as heavy infantry or line infantry. Historically, light infantry often fought ...

by the end of the war despite attempts at massed use in the Western Theatre by US and Britain during Operation Market Garden

Operation Market Garden was an Allies of World War II, Allied military operation during the World War II, Second World War fought in the Netherlands from 17 to 27 September 1944. Its objective was to create a Salient (military), salient into G ...

.

Naval aviation

Aircraft and theaircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

first became important in naval battles in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

. Carrier-based aircraft

Carrier-based aircraft, sometimes known as carrier-capable aircraft or carrier-borne aircraft, are naval aircraft designed for operations from aircraft carriers. They must be able to launch in a short distance and be sturdy enough to withstand ...

were specialized as dive bombers, torpedo bombers, and fighters.

Surface-based aircraft such as the Consolidated PBY Catalina

The Consolidated PBY Catalina is a flying boat and amphibious aircraft that was produced in the 1930s and 1940s. In Canadian service it was known as the Canso. It was one of the most widely used seaplanes of World War II. Catalinas served w ...

and Short Sunderland

The Short S.25 Sunderland is a British flying boat patrol bomber, developed and constructed by Short Brothers for the Royal Air Force (RAF). The aircraft took its service name from the town (latterly, city) and port of Sunderland in North East ...

helped finding submarines and surface fleets. The aircraft carrier replaced the battleship as the most powerful naval offensive weapons system as battles between fleets were increasingly fought out of gun range by aircraft. The Yamato, the most powerful battleship ever built was first turned back by light escort carrier aircraft, and later sunk due to it lacking its own air cover.

The US launched US Army Air Forces

The United States Army Air Forces (USAAF or AAF) was the major land-based aerial warfare service component of the United States Army and ''de facto'' aerial warfare service branch of the United States during and immediately after World War II ...

land-based bombers from United States Navy

The United States Navy (USN) is the maritime service branch of the United States Armed Forces and one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. It is the largest and most powerful navy in the world, with the estimated tonnage ...

carriers in a raid against Tokyo. Smaller carriers were built in large numbers to escort slow cargo convoys or supplement fast carriers. Aircraft for observation or light raids were also carried by battleships and cruisers, while blimps

A blimp, or non-rigid airship, is an airship (dirigible) without an internal structural framework or a keel. Unlike semi-rigid and rigid airships (e.g. Zeppelins), blimps rely on the pressure of the lifting gas (usually helium, rather than hydr ...

were used to search for attack submarines.

In the Battle of the Atlantic

The Battle of the Atlantic, the longest continuous military campaign in World War II, ran from 1939 to the defeat of Nazi Germany in 1945, covering a major part of the naval history of World War II. At its core was the Allied naval blockade ...

, aircraft carried by low-cost escort carriers were used for antisubmarine patrol, defense, and attack. At the start of the Pacific War

The Pacific War, sometimes called the Asia–Pacific War, was the theater of World War II that was fought in Asia, the Pacific Ocean, the Indian Ocean, and Oceania. It was geographically the largest theater of the war, including the vast ...

in 1941, Japanese carrier-based aircraft sank several US battleships at Pearl Harbor

Pearl Harbor is an American lagoon harbor on the island of Oahu, Hawaii, west of Honolulu. It was often visited by the Naval fleet of the United States, before it was acquired from the Hawaiian Kingdom by the U.S. with the signing of the Re ...

and land-based aircraft sank two large British warships. Engagements between Japanese and American naval fleets were then conducted largely or entirely by aircraft including the battles of Coral Sea

The Coral Sea () is a marginal sea of the South Pacific off the northeast coast of Australia, and classified as an interim Australian bioregion. The Coral Sea extends down the Australian northeast coast. Most of it is protected by the Fre ...

, Midway, Bismarck Sea

The Bismarck Sea (, ) lies in the southwestern Pacific Ocean within the nation of Papua New Guinea. It is located northeast of the island of New Guinea and south of the Bismarck Archipelago. It has coastlines in districts of the Islands Region, ...

and Philippine Sea

The Philippine Sea is a marginal sea of the Western Pacific Ocean east of the Philippine archipelago (hence the name), the largest in the world, occupying an estimated surface area of . The Philippine Sea Plate forms the floor of the sea. Its ...

.Boyne (2003), pp.227–8

Cold War

Military aviation in the post-war years was dominated by the needs of theCold War

The Cold War is a term commonly used to refer to a period of geopolitical tension between the United States and the Soviet Union and their respective allies, the Western Bloc and the Eastern Bloc. The term '' cold war'' is used because the ...

. The post-war years saw the almost total conversion of combat aircraft to jet power, which resulted in enormous increases in speeds and altitudes of aircraft.Gross (2002), p.151 Until the advent of the Intercontinental Ballistic Missile

An intercontinental ballistic missile (ICBM) is a ballistic missile with a range greater than , primarily designed for nuclear weapons delivery (delivering one or more thermonuclear warheads). Conventional, chemical, and biological weapons c ...

major powers relied on high-altitude bombers to deliver their newly developed nuclear deterrent and each country strove to develop the technology of bombers and the high-altitude fighters that could intercept them. The concept of air superiority began to play a heavy role in aircraft designs for both the United States and the Soviet Union.

The Americans developed and made extensive use of the high-altitude observation aircraft for intelligence-gathering. The Lockheed U-2

The Lockheed U-2, nicknamed "''Dragon Lady''", is an American single-jet engine, high altitude reconnaissance aircraft operated by the United States Air Force (USAF) and previously flown by the Central Intelligence Agency (CIA). It provides day ...

, and later the Lockheed SR-71 Blackbird

The Lockheed SR-71 "Blackbird" is a long-range, high-altitude, Mach 3+ strategic reconnaissance aircraft developed and manufactured by the American aerospace company Lockheed Corporation. It was operated by the United States Air Force ...

were developed in great secrecy. The U-2 at its time was expected to be invulnerable to defensive measures due to its extreme altitude capabilities. It therefore came as a shock when the Soviets downed one piloted by Gary Powers

Francis Gary Powers (August 17, 1929 – August 1, 1977) was an American pilot whose Central Intelligence Agency (CIA) Lockheed U-2 spy plane was shot down while flying a reconnaissance mission in Soviet Union airspace, causing the 1960 U-2 in ...

with a surface-to-air missile

A surface-to-air missile (SAM), also known as a ground-to-air missile (GTAM) or surface-to-air guided weapon (SAGW), is a missile designed to be launched from the ground to destroy aircraft or other missiles. It is one type of anti-aircraft syst ...

.

Air combat was also transformed through increased use of air-to-air guided missiles

In military terminology, a missile is a guided airborne ranged weapon capable of self-propelled flight usually by a jet engine or rocket motor. Missiles are thus also called guided missiles or guided rockets (when a previously unguided rocket i ...

with increased sophistication in guidance

Guidance may refer to:

Arts and media

* ''Guidance'' (album), by American instrumental rock band Russian Circles

* ''Guidance'' (film), a Canadian comedy film released in 2014

* ''Guidance'' (web series), a 2015–2017 American web series

* "G ...

and increased range

Range may refer to:

Geography

* Range (geographic), a chain of hills or mountains; a somewhat linear, complex mountainous or hilly area (cordillera, sierra)

** Mountain range, a group of mountains bordered by lowlands

* Range, a term used to i ...

. In the 1970s and 1980s it became clear that speed and altitude was not enough to protect a bomber against air defences. The emphasis shifted therefore to maneuverable attack aircraft that could fly 'under the radar', at altitudes of a few hundred feet.

Korean War

The Korean War was best remembered for jet combat, but was one of the last major wars where propeller-powered fighters such as theNorth American P-51 Mustang

The North American Aviation P-51 Mustang is an American long-range, single-seat fighter aircraft, fighter and fighter-bomber used during World War II and the Korean War, among other conflicts. The Mustang was designed in April 1940 by a team ...

, Vought F4U Corsair

The Vought F4U Corsair is an American fighter aircraft which saw service primarily in World War II and the Korean War. Designed and initially manufactured by Chance Vought, the Corsair was soon in great demand; additional production contracts ...

and aircraft carrier

An aircraft carrier is a warship that serves as a seagoing airbase, equipped with a full-length flight deck and facilities for carrying, arming, deploying, and recovering aircraft. Typically, it is the capital ship of a fleet, as it allows a ...

-based Hawker Sea Fury

The Hawker Sea Fury is a British fighter aircraft designed and manufactured by Hawker Aircraft. It was the last propeller-driven fighter to serve with the Royal Navy, and one of the fastest production single reciprocating engine aircraft e ...

and Supermarine Seafire

The Supermarine Seafire is a naval version of the Supermarine Spitfire adapted for operation from aircraft carriers. It was analogous in concept to the Hawker Sea Hurricane, a navalised version of the Spitfire's stablemate, the Hawker Hurri ...

were used. Turbojet

The turbojet is an airbreathing jet engine which is typically used in aircraft. It consists of a gas turbine with a propelling nozzle. The gas turbine has an air inlet which includes inlet guide vanes, a compressor, a combustion chamber, and ...

fighter aircraft such as Lockheed F-80 Shooting Star

The Lockheed P-80 Shooting Star was the first jet fighter used operationally by the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) during World War II. Designed and built by Lockheed in 1943 and delivered just 143 days from the start of design, prod ...

s, Republic F-84 Thunderjet

The Republic F-84 Thunderjet was an American turbojet fighter-bomber aircraft. Originating as a 1944 United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) proposal for a "day fighter", the F-84 first flew in 1946. Although it entered service in 1947, the Thu ...

s and Grumman F9F Panther

The Grumman F9F Panther is one of the United States Navy's first successful carrier-based jet fighters, as well as Grumman’s first jet fighter. A single-engined, straight-winged day fighter, it was armed with four cannons and could carry a w ...

s came to dominate the skies, overwhelming North Korea's propeller-driven Yakovlev Yak-9

The Yakovlev Yak-9 (russian: Яковлев Як-9) is a single-engine, single-seat multipurpose fighter aircraft used by the Soviet Union and its allies during World War II and the early Cold War. It was a development of the robust and successf ...

s and Lavochkin La-9

The Lavochkin La-9 (NATO reporting name Fritz) was a Soviet fighter aircraft produced shortly after World War II. It was one of the last piston engined fighters to be produced before the widespread adoption of the jet engine.

Development

La-9 r ...

s.

From 1950, North Koreans flew the Soviet-made MiG-15

The Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15 (russian: Микоя́н и Гуре́вич МиГ-15; USAF/DoD designation: Type 14; NATO reporting name: Fagot) is a jet fighter aircraft developed by Mikoyan-Gurevich for the Soviet Union. The MiG-15 was one of ...

jet fighters which introduced the near-sonic speeds of swept wings to air combat. Though an open secret during the war, the most formidable pilots today now admit that they were experienced Soviet Air Force

The Soviet Air Forces ( rus, Военно-воздушные силы, r=Voyenno-vozdushnyye sily, VVS; literally "Military Air Forces") were one of the air forces of the Soviet Union. The other was the Soviet Air Defence Forces. The Air Forces ...

pilots, a ''casus belli

A (; ) is an act or an event that either provokes or is used to justify a war. A ''casus belli'' involves direct offenses or threats against the nation declaring the war, whereas a ' involves offenses or threats against its ally—usually one b ...

'' deliberately overlooked by the UN allied forces who suspected the use of Russians but were reluctant to engage in open war with the Soviet Union and the People's Republic of China.

At first, UN jet fighters, which also included Royal Australian Air Force

"Through Adversity to the Stars"

, colours =

, colours_label =

, march =

, mascot =

, anniversaries = RAAF Anniversary Commemoration ...

Gloster Meteors, had some success, but straight winged jets were soon outclassed in daylight by the superior speed of the MiGs. At night, however, radar-equipped Marine Corps Douglas F3D Skynight night fighters claimed five MiG kills with no losses of their own,Grossnick, Roy A. and William J. Armstrong. ''United States Naval Aviation, 1910–1995''. Annapolis, Maryland: Naval Historical Center, 1997. . and no B-29s under their escort were lost to enemy fighters.

In December 1950, the U.S. Air Force

The United States Air Force (USAF) is the air service branch of the United States Armed Forces, and is one of the eight uniformed services of the United States. Originally created on 1 August 1907, as a part of the United States Army Signal ...

rushed in their own swept-wing fighter, the North American F-86 Sabre

The North American F-86 Sabre, sometimes called the Sabrejet, is a transonic jet fighter aircraft. Produced by North American Aviation, the Sabre is best known as the United States' first swept-wing fighter that could counter the swept-wing So ...

. The MiG could fly higher, 50,000 vs. , offering a distinct advantage at the start of combat. In level flight, their maximum speeds were comparable at about . The MiG could climb better, while the Sabre

could dive better with an all-flying tailplane. For weapons, the MiG carried two 23 mm and one 37 mm cannon, compared to the Sabre's six .50 (12.7 mm) caliber machine guns. The American .50 caliber machine guns, while not packing the same punch, carried many more rounds and were aimed with a more accurate radar-ranging gunsight. The U.S. pilots also had the advantage of G-suit

A g-suit, or anti-''g'' suit, is a flight suit worn by aviators and astronauts who are subject to high levels of acceleration force ( g). It is designed to prevent a black-out and g-LOC (g-induced loss of consciousness) caused by the blood pool ...

s, which were used for the first time in this war.

Even after the Air Force introduced the advanced F-86, its pilots often struggled against the jets piloted by Soviet pilots, dubbed "honchos". The UN gradually gained air superiority

Aerial supremacy (also air superiority) is the degree to which a side in a conflict holds control of air power over opposing forces. There are levels of control of the air in aerial warfare. Control of the air is the aerial equivalent of c ...

over most of Korea that lasted until the end of the war. It was a decisive factor in helping the UN first advance into the north, and then resist the Chinese invasion of South Korea.

After the war, the USAF claimed 792 MiG-15s and 108 additional aircraft shot down by Sabres for the loss of 78 Sabres. Later research reduced the total to 379 victories which is still higher than the 345 losses shown in USSR records.

The Soviets claimed about 1,100 air-to-air victories and 335 combat MiG losses at that time. China's official losses were 231 planes shot down in air-to-air combat (mostly MiG-15s) and 168 other losses. The number of losses of the North Korean Air Force was not revealed. It is estimated that it lost about 200 aircraft in the first stage of the war, and another 70 aircraft after Chinese intervention.

Soviet claims of 650 victories over the Sabres, and China's claims of another 211 F-86s, are considered to be exaggerated by the USAF.

The Korean war was the first time the helicopter

A helicopter is a type of rotorcraft in which lift and thrust are supplied by horizontally spinning rotors. This allows the helicopter to take off and land vertically, to hover, and to fly forward, backward and laterally. These attributes ...

was used extensively in a conflict. While helicopters such as the Sikorsky YR-4 were used in World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great powers—forming two opposin ...

, their use was rare, and Jeep

Jeep is an American automobile marque, now owned by multi-national corporation Stellantis. Jeep has been part of Chrysler since 1987, when Chrysler acquired the Jeep brand, along with remaining assets, from its previous owner American Moto ...

s like the Willys MB

The Willys MB and the Ford GPW, both formally called the U.S. Army Truck, -ton, 4×4, Command Reconnaissance, commonly known as the Willys Jeep, Jeep, or jeep, and sometimes referred to by its List of U.S. military vehicles by supply catalog ...

were the main method of removing an injured soldier. In the Korean war helicopters like the Sikorsky H-19

The Sikorsky H-19 Chickasaw (company model number S-55) was a multi-purpose helicopter used by the United States Army and United States Air Force. It was also license-built by Westland Aircraft as the Westland Whirlwind in the United Kingdom ...

partially took over in the non combat Medevac

Medical evacuation, often shortened to medevac or medivac, is the timely and efficient movement and en route care provided by medical personnel to wounded being evacuated from a battlefield, to injured patients being evacuated from the scene of a ...

area.

Indo-Pakistani Wars

During theIndo-Pakistani War of 1965