The history of Guyana begins about 35,000 years ago with the arrival of humans coming from

Eurasia

Eurasia (, ) is the largest continental area on Earth, comprising all of Europe and Asia. Primarily in the Northern and Eastern Hemispheres, it spans from the British Isles and the Iberian Peninsula in the west to the Japanese archipelag ...

. These migrants became the

Carib and

Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Greate ...

tribes, who met Alonso de Ojeda's first expedition from Spain in 1499 at the

Essequibo River

The Essequibo River ( Spanish: ''Río Esequibo'' originally called by Alonso de Ojeda ''Río Dulce'') is the largest river in Guyana, and the largest river between the Orinoco and Amazon. Rising in the Acarai Mountains near the Brazil–Guyana b ...

. In the ensuing colonial era,

Guyana

Guyana ( or ), officially the Cooperative Republic of Guyana, is a country on the northern mainland of South America. Guyana is an indigenous word which means "Land of Many Waters". The capital city is Georgetown. Guyana is bordered by the ...

's government was defined by the successive policies of Spanish, French, Dutch, and British settlers.

During the colonial period, Guyana's economy was focused on plantation agriculture, which initially depended on slave labor. Guyana saw major slave rebellions in

1763 and again in

1823

Events January–March

* January 22 – By secret treaty signed at the Congress of Verona, the Quintuple Alliance gives France a mandate to invade Spain for the purpose of restoring Ferdinand VII (who has been captured by armed revolutio ...

. Great Britain passed the Slavery Abolition Act in British Parliament that abolished slavery in most British colonies, freeing more than 800,000 enslaved Africans in the Caribbean and South Africa as well as a small number in Canada. It received Royal Assent on August 28, 1833, and took effect on August 1, 1834. Thus, in the immediate period following this historical law, slavery was ended in British Guiana. To address the labor shortage, plantations began to contract indentured workers mainly from India. Eventually, these Indians joined forces with the Afro-Guyanese descendants of slaves to demand equal rights in government and society, demands underscored by the 1905

Ruimveldt Riots. Eventually, after the second world war, the British Empire pursued policy decolonization of its overseas territories and independence was granted to British Guiana on May 26, 1966.

Following independence,

Forbes Burnham

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham (20 February 1923 – 6 August 1985) was a Guyanese politician and the leader of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana from 1964 until his death in 1985. He served as Prime Minister of Guyana, Prime Minister from 1964 ...

rose to power, quickly becoming an authoritarian leader pledging to bring socialism to Guyana. His power began to weaken with the international attention brought to Guyana in the wake of the

Jonestown

The Peoples Temple Agricultural Project, better known by its informal name "Jonestown", was a remote settlement in Guyana established by the Peoples Temple, a U.S.–based cult under the leadership of Jim Jones. Jonestown became internationall ...

massacres in 1978. After his unexpected death in 1985, power was peacefully transferred to

Desmond Hoyte

Hugh Desmond Hoyte (9 March 1929 – 22 December 2002) was a Guyanese politician who served as Prime Minister of Guyana from 1984 to 1985 and President of Guyana from 1985 until 1992.

Personal Life and Education

Hoyte was born on 9 March 1 ...

, who implemented some democratic reforms before being voted out in 1992

Pre-colonial Guyana and first contacts

The first people to reach Guyana made their way from Siberia, perhaps as far back as 20,000 years ago. These first inhabitants were

nomads

A nomad is a member of a community without fixed habitation who regularly moves to and from the same areas. Such groups include hunter-gatherers, pastoral nomads (owning livestock), tinkers and trader nomads. In the twentieth century, the po ...

who slowly migrated south into Central and South America. At the time of

Christopher Columbus

Christopher Columbus

* lij, Cristoffa C(or)ombo

* es, link=no, Cristóbal Colón

* pt, Cristóvão Colombo

* ca, Cristòfor (or )

* la, Christophorus Columbus. (; born between 25 August and 31 October 1451, died 20 May 1506) was a ...

's voyages, Guyana's inhabitants were divided into two groups, the

Arawak

The Arawak are a group of indigenous peoples of northern South America and of the Caribbean. Specifically, the term "Arawak" has been applied at various times to the Lokono of South America and the Taíno, who historically lived in the Greate ...

along the coast and the

Carib in the interior. One of the legacies of the indigenous peoples was the word Guiana, often used to describe the region encompassing modern Guyana as well as

Suriname

Suriname (; srn, Sranankondre or ), officially the Republic of Suriname ( nl, Republiek Suriname , srn, Ripolik fu Sranan), is a country on the northeastern Atlantic coast of South America. It is bordered by the Atlantic Ocean to the nor ...

(former Dutch Guiana) and

French Guiana

French Guiana ( or ; french: link=no, Guyane ; gcr, label= French Guianese Creole, Lagwiyann ) is an overseas department/region and single territorial collectivity of France on the northern Atlantic coast of South America in the Guianas ...

. The word, which means "land of waters", is appropriate considering the area's multitude of rivers and streams.

Historians speculate that the Arawaks and Caribs originated in the South American

hinterland

Hinterland is a German word meaning "the land behind" (a city, a port, or similar). Its use in English was first documented by the geographer George Chisholm in his ''Handbook of Commercial Geography'' (1888). Originally the term was associate ...

and migrated northward, first to the present-day Guianas and then to the

Caribbean islands

Almost all of the Caribbean islands are in the Caribbean Sea, with only a few in inland lakes. The largest island is Cuba. Other sizable islands include Hispaniola, Jamaica, Puerto Rico and Trinidad and Tobago. Some of the smaller islands a ...

. The Arawak, mainly cultivators, hunters, and fishermen, migrated to the Caribbean islands before the Carib and settled throughout the region. The tranquility of Arawak society was disrupted by the arrival of the bellicose Carib from the South American interior. The warlike behavior of the Carib and their violent migration north made an impact. By the end of the 15th century, the Carib had displaced the Arawak throughout the islands of the

Lesser Antilles

The Lesser Antilles ( es, link=no, Antillas Menores; french: link=no, Petites Antilles; pap, Antias Menor; nl, Kleine Antillen) are a group of islands in the Caribbean Sea. Most of them are part of a long, partially volcanic island arc be ...

. The Carib settlement of the Lesser Antilles also affected Guyana's future development. The Spanish explorers and settlers who came after Columbus found that the Arawak proved easier to conquer than the Carib, who fought hard to maintain their independence. This fierce resistance, along with a lack of gold in the Lesser Antilles, contributed to the Spanish emphasis on conquest and settlement of the

Greater Antilles

The Greater Antilles ( es, Grandes Antillas or Antillas Mayores; french: Grandes Antilles; ht, Gwo Zantiy; jam, Grieta hAntiliiz) is a grouping of the larger islands in the Caribbean Sea, including Cuba, Hispaniola, Puerto Rico, Jamaica, a ...

and the mainland. Only a weak Spanish effort was made at consolidating Spain's authority in the Lesser Antilles (with the arguable exception of

Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

) and the Guianas.

Colonial-Guyana

Early colonisation

The

Dutch

Dutch commonly refers to:

* Something of, from, or related to the Netherlands

* Dutch people ()

* Dutch language ()

Dutch may also refer to:

Places

* Dutch, West Virginia, a community in the United States

* Pennsylvania Dutch Country

People E ...

were the first Europeans to settle modern-day Guyana. The Netherlands had

obtained independence from Spain in the late 16th century and by the early 17th century had emerged as a major commercial power, trading with the fledgling English and French colonies in the Lesser Antilles. In 1616 the Dutch established the first European settlement in the area of Guyana, a trading post-twenty-five kilometers upstream from the mouth of the

Essequibo River

The Essequibo River ( Spanish: ''Río Esequibo'' originally called by Alonso de Ojeda ''Río Dulce'') is the largest river in Guyana, and the largest river between the Orinoco and Amazon. Rising in the Acarai Mountains near the Brazil–Guyana b ...

. Other settlements followed, usually a few kilometers inland on the larger rivers. The initial purpose of the Dutch settlements was trade with the indigenous people. The Dutch aim soon changed to the acquisition of territory as other European powers gained colonies elsewhere in the Caribbean. Although Guyana was claimed by the Spanish, who sent periodic patrols through the region, the Dutch gained control over the region early in the 17th century. Dutch sovereignty was officially recognized with the signing of the

Treaty of Munster in 1648.

In 1621 the government of the Netherlands gave the newly formed

Dutch West India Company

The Dutch West India Company ( nl, Geoctrooieerde Westindische Compagnie, ''WIC'' or ''GWC''; ; en, Chartered West India Company) was a chartered company of Dutch merchants as well as foreign investors. Among its founders was Willem Usselincx ...

complete control over the trading post on the Essequibo. This Dutch commercial concern administered the colony, known as

Essequibo Essequibo is the largest traditional region of Guyana but not an administrative region of Guyana today. It may also refer to:

* Essequibo River, the largest river in Guyana

* Essequibo (colony), a former Dutch colony in what is now Guyana;

* Esseq ...

, for more than 170 years. The company established a second colony, on the

Berbice River

The Berbice River, located in eastern Guyana, is one of the country's major rivers. It rises in the highlands of the Rupununi region and flows northward for through dense forests to the coastal plain. The river's tidal limit is between from the ...

southeast of

Essequibo Essequibo is the largest traditional region of Guyana but not an administrative region of Guyana today. It may also refer to:

* Essequibo River, the largest river in Guyana

* Essequibo (colony), a former Dutch colony in what is now Guyana;

* Esseq ...

, in 1627. Although under the general jurisdiction of this private group, the settlement, named

Berbice

Berbice is a region along the Berbice River in Guyana, which was between 1627 and 1792 a colony of the Dutch West India Company and between 1792 to 1815 a colony of the Dutch state. After having been ceded to the United Kingdom of Great Britain a ...

, was governed separately.

Demerara

Demerara ( nl, Demerary, ) is a historical region in the Guianas, on the north coast of South America, now part of the country of Guyana. It was a colony of the Dutch West India Company between 1745 and 1792 and a colony of the Dutch state f ...

, situated between Essequibo and Berbice, was settled in 1741 and emerged in 1773 as a separate colony under the direct control of the Dutch West India Company.

Although the Dutch colonizers initially were motivated by the prospect of trade in the Caribbean, their possessions became significant producers of crops. The growing importance of agriculture was indicated by the export of 15,000 kilograms of

tobacco

Tobacco is the common name of several plants in the genus '' Nicotiana'' of the family Solanaceae, and the general term for any product prepared from the cured leaves of these plants. More than 70 species of tobacco are known, but the ...

from Essequibo in 1623. But as the agricultural productivity of the Dutch colonies increased, a labor shortage emerged. The indigenous populations were poorly adapted for work on

plantations

A plantation is an agricultural estate, generally centered on a plantation house, meant for farming that specializes in cash crops, usually mainly planted with a single crop, with perhaps ancillary areas for vegetables for eating and so on. Th ...

, and many people died from

diseases introduced by the Europeans. The Dutch West India Company turned to the importation of

enslaved Africans, who rapidly became a key element in the colonial economy. By the 1660s, the enslaved population numbered about 2,500; the number of indigenous people was estimated at 50,000, most of whom had retreated into the vast hinterland. Although enslaved Africans were considered an essential element of the colonial economy, their working conditions were brutal. The mortality rate was high, and the dismal conditions led to more than half a dozen rebellions led by the enslaved Africans.

The most famous uprising of the enslaved Africans, the

Berbice Slave Uprising

The Berbice slave uprising was a slave revolt in Guyana that began on 23 February 1763Cleve McD. Scott"Berbice Slave Revolt (1763)" in Junius P. Rodriguez, ''Encyclopedia of Slave Resistance and Rebellion'', Vol. 1, Westport, Ct: Greenwood Press, 2 ...

, began in February 1763. On two plantations on the

Canje River in Berbice, the enslaved Africans rebelled, taking control of the region. As plantation after plantation fell to the enslaved Africans, the European population fled; eventually only half of the whites who had lived in the colony remained. Led by

Coffy

''Coffy'' is a 1973 American blaxploitation film written and directed by Jack Hill. The story is about a black female vigilante played by Pam Grier who seeks violent revenge against a heroin dealer responsible for her sister's addiction.Gary A. ...

(now the national hero of Guyana), the escaped enslaved Africans came to number about 3,000 and threatened European control over the Guianas. The rebels were defeated with the assistance of troops from neighboring European colonies like from the British, French,

Sint Eustatius

Sint Eustatius (, ), also known locally as Statia (), is an island in the Caribbean. It is a special municipality (officially "public body") of the Netherlands.

The island lies in the northern Leeward Islands portion of the West Indies, sout ...

and overseas from the

Dutch Republic

The United Provinces of the Netherlands, also known as the (Seven) United Provinces, officially as the Republic of the Seven United Netherlands ( Dutch: ''Republiek der Zeven Verenigde Nederlanden''), and commonly referred to in historiograph ...

. The 1763 Monument on Square of the Revolution in Georgetown, Guyana commemorates the uprising.

Transition to British Rule

Eager to attract more settlers, in 1746 the Dutch authorities opened the area near the

Demerara River to British immigrants. British plantation owners in the Lesser Antilles had been plagued by poor soil and erosion, and many were lured to the Dutch colonies by richer soils and the promise of land ownership. The influx of British citizens was so great that by 1760 the English constituted a majority of the European population of Demerara. By 1786 the internal affairs of this Dutch colony were effectively under British control,

though two-thirds of the plantation owners were still Dutch.

As economic growth accelerated in Demerara and Essequibo, strains began to appear in the relations between the planters and the Dutch West India Company. Administrative reforms during the early 1770s had greatly increased the cost of government. The company periodically sought to raise taxes to cover these expenditures and thereby provoked the resistance of the planters. In 1781 a

war

War is an intense armed conflict between states, governments, societies, or paramilitary groups such as mercenaries, insurgents, and militias. It is generally characterized by extreme violence, destruction, and mortality, using regular o ...

broke out between the Netherlands and Britain, which resulted in the British occupation of Berbice, Essequibo, and Demerara. Some months later, France, allied with the Netherlands, seized control of the colonies. The French governed for two years, during which they constructed a new town, Longchamps, at the mouth of the Demerara River. When the Dutch regained power in 1784, they moved their colonial capital to Longchamps, which they renamed Stabroek. The capital was in 1812 renamed

Georgetown by the British.

The return of Dutch rule reignited conflict between the planters of Essequibo and Demerara and the Dutch West India Company. Disturbed by plans for an increase in the slave tax and a reduction in their representation on the colony's judicial and policy councils, the colonists petitioned the Dutch government to consider their grievances. In response, a special committee was appointed, which proceeded to draw up a report called the

Concept Plan of Redress. This document called for far-reaching constitutional reforms and later became the basis of the British governmental structure. The plan proposed a decision-making body to be known as the

Court of Policy

The Court of Policy was a legislative body in Dutch and British Guiana until 1928. For most of its existence it formed the Combined Court together with the six Financial Representatives.

History

The Court of Policy was established in 1732 by the ...

. The judiciary was to consist of two courts of justice, one serving Demerara and the other Essequibo. The membership of the Court of Policy and of the courts of justice would consist of company officials and planters who owned more than twenty-five slaves. The Dutch commission that was assigned the responsibility of implementing this new system of government returned to the Netherlands with extremely unfavorable reports concerning the Dutch West India Company's administration. The company's charter, therefore, was allowed to expire in 1792 and the Concept Plan of Redress was put into effect in Demerara and Essequibo. Renamed the

United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo, the area then came under the direct control of the Dutch government. Berbice maintained its status as a separate colony.

The catalyst for formal British takeover was the

French Revolution

The French Revolution ( ) was a period of radical political and societal change in France that began with the Estates General of 1789 and ended with the formation of the French Consulate in November 1799. Many of its ideas are conside ...

and the subsequent

Napoleonic Wars

The Napoleonic Wars (1803–1815) were a series of major global conflicts pitting the French Empire and its allies, led by Napoleon I, against a fluctuating array of European states formed into various coalitions. It produced a period of Fre ...

. In 1795 the French occupied the Netherlands. The British declared war on France and in 1796 launched an expeditionary force from

Barbados

Barbados is an island country in the Lesser Antilles of the West Indies, in the Caribbean region of the Americas, and the most easterly of the Caribbean Islands. It occupies an area of and has a population of about 287,000 (2019 estima ...

to occupy the Dutch colonies. The British takeover was bloodless, and the local Dutch administration of the colony was left relatively uninterrupted under the constitution provided by the Concept Plan of Redress.

Both Berbice and the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo were under British control from 1796 to 1802. By means of the

Treaty of Amiens

The Treaty of Amiens (french: la paix d'Amiens, ) temporarily ended hostilities between France and the United Kingdom at the end of the War of the Second Coalition. It marked the end of the French Revolutionary Wars; after a short peace it s ...

, both were returned to Dutch control. Peace was short-lived, however. The war between Britain and France resumed in less than a year, and in 1803 the United Colony and Berbice were seized once more by British troops. At the

London Convention of 1814, both colonies were formally ceded to Britain. In 1831, Berbice and the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo were unified as

British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first European to encounter Guiana was ...

. The colony would remain under British control until independence in 1966.

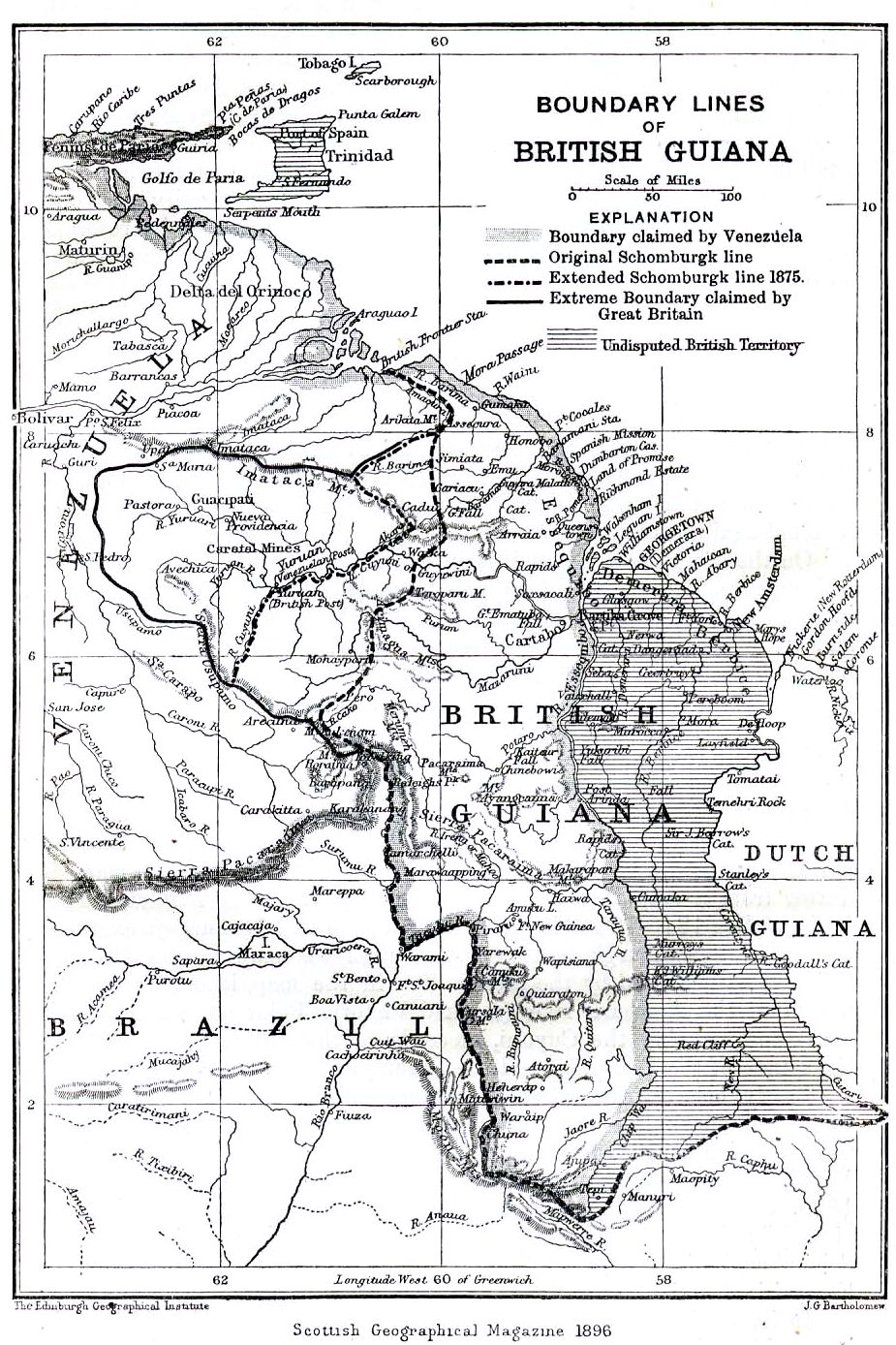

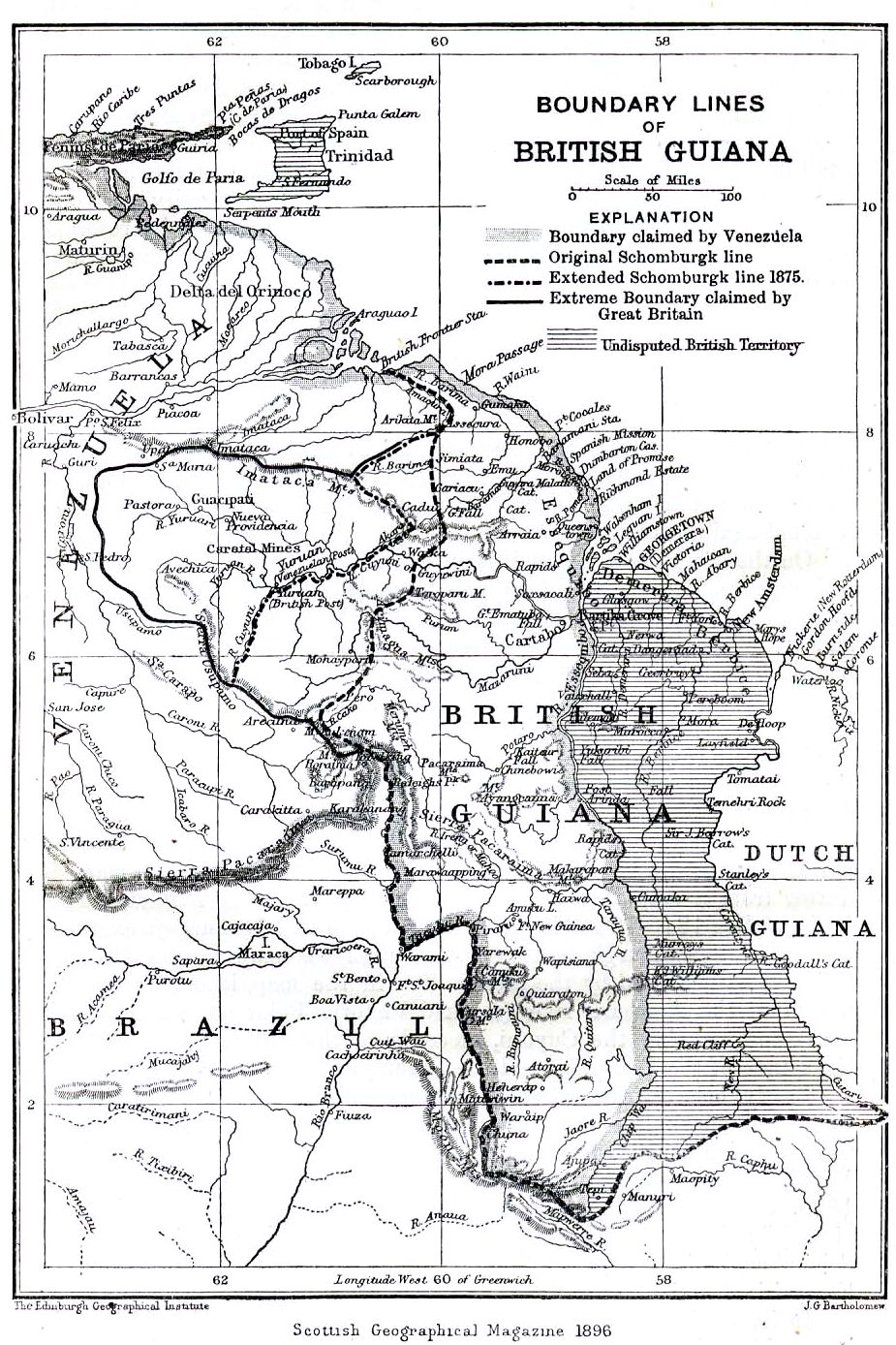

Origins of the border dispute with Venezuela

When Britain gained formal control over what is now Guyana in 1814, it also became involved in one of Latin America's most persistent border disputes. At the London Convention of 1814, the Dutch surrendered the United Colony of Demerara and Essequibo and Berbice to the British, a colony which had the Essequibo river as its west border with the Spanish colony of Venezuela. Although Spain still claimed the region, the Spanish did not contest the treaty because they were preoccupied with their own colonies' struggles for independence. In 1835 the British government asked German explorer

Robert Hermann Schomburgk

Sir Robert Hermann Schomburgk (5 June 1804 – 11 March 1865) was a German-born explorer for Great Britain who carried out geographical, ethnological and botanical studies in South America and the West Indies, and also fulfilled diplomatic missi ...

to map British Guiana and mark its boundaries. As ordered by the British authorities, Schomburgk began British Guiana's western boundary with

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

at the mouth of the

Orinoco River

The Orinoco () is one of the longest rivers in South America at . Its drainage basin, sometimes known as the Orinoquia, covers , with 76.3 percent of it in Venezuela and the remainder in Colombia. It is the fourth largest river in the wor ...

, although all the Venezuelan maps showed the Essequibo river as the east border of the country. A map of the British colony was published in 1840. Venezuela protested, claiming the entire area west of the Essequibo River. Negotiations between Britain and Venezuela over the boundary began, but the two nations could reach no compromise. In 1850 both agreed not to occupy the disputed zone.

The discovery of gold in the contested area in the late 1850s reignited the dispute. British settlers moved into the region and the

British Guiana Mining Company

British may refer to:

Peoples, culture, and language

* British people, nationals or natives of the United Kingdom, British Overseas Territories, and Crown Dependencies.

** Britishness, the British identity and common culture

* British English, ...

was formed to mine the deposits. Over the years, Venezuela made repeated protests and proposed arbitration, but the British government was uninterested. Venezuela finally broke diplomatic relations with Britain in 1887 and appealed to the United States for help. The British at first rebuffed the United States government's suggestion of arbitration, but when President

Grover Cleveland

Stephen Grover Cleveland (March 18, 1837June 24, 1908) was an American lawyer and politician who served as the 22nd and 24th president of the United States from 1885 to 1889 and from 1893 to 1897. Cleveland is the only president in American ...

threatened to intervene according to the

Monroe Doctrine

The Monroe Doctrine was a United States foreign policy position that opposed European colonialism in the Western Hemisphere. It held that any intervention in the political affairs of the Americas by foreign powers was a potentially hostile act ...

, Britain agreed to let an international tribunal arbitrate the boundary in 1897.

For two years, the tribunal consisting of two Britons, two Americans, and a Russian studied the case in Paris (France). Their three-to-two decision, handed down in 1899, awarded 94 percent of the disputed territory to British Guiana. Venezuela received only the mouths of the Orinoco River and a short stretch of the Atlantic coastline just to the east. Although Venezuela was unhappy with the decision, a commission surveyed a new border in accordance with the award, and both sides accepted the boundary in 1905. The issue was considered settled for the next half-century.

The early British Colony and the labor problem

Political, economic, and social life in the 19th century was dominated by a European planter class. Although the smallest group in terms of numbers, members of the

plantocracy had links to British commercial interests in London and often enjoyed close ties to the governor, who was appointed by the monarch. The plantocracy also controlled exports and the working conditions of the majority of the population. The next social stratum consisted of a small number of

freed slaves, many of mixed African and European heritage, in addition to some

Portuguese merchants. At the lowest level of society was the majority, the African slaves who lived and worked in the countryside, where the plantations were located. Unconnected to colonial life, small groups of Amerindians lived in the hinterland.

Colonial life was changed radically by the demise of slavery. Although the international slave trade was

abolished in the

British Empire

The British Empire was composed of the dominions, colonies, protectorates, mandates, and other territories ruled or administered by the United Kingdom and its predecessor states. It began with the overseas possessions and trading posts e ...

in 1807, slavery itself continued. In what is known as the

Demerara rebellion of 1823

The Demerara rebellion of 1823 was an uprising involving more than 10,000 enslaved people that took place in the colony of Demerara-Essequibo (Guyana). The rebellion, which began on August 18, 1823, and lasted for two days, was led by slaves w ...

10–13,000 slaves in

Demerara-Essequibo

The Colony of Demerara-Essequibo was created on 28 April 1812, when the British combined the colonies of Demerara and Essequibo into the colony of Demerara-Essequibo. They were officially ceded to Britain on 13 August 1814. On 20 November 1815 the ...

rose up against their oppressors. Although the rebellion was easily crushed, the momentum for abolition remained, and by 1838 total emancipation had been effected. The end of slavery had several ramifications. Most significantly, many former slaves rapidly departed the plantations. Some ex-slaves moved to towns and villages, feeling that field labor was degrading and inconsistent with freedom, but others pooled their resources to purchase the abandoned estates of their former masters and created village communities. Establishing small settlements provided the new

Afro-Guyanese communities an opportunity to grow and sell food, an extension of a practice under which slaves had been allowed to keep the money that came from the sale of any surplus produce. The emergence of an independent-minded Afro-Guyanese peasant class, however, threatened the planters' political power, inasmuch as the planters no longer held a near-monopoly on the colony's economic activity.

Emancipation also resulted in the introduction of new ethnic and cultural groups into British Guiana. The departure of the Afro-Guyanese from the sugar plantations soon led to labor shortages. After unsuccessful attempts throughout the 19th century to attract Portuguese workers from

Madeira

)

, anthem = ( en, "Anthem of the Autonomous Region of Madeira")

, song_type = Regional anthem

, image_map=EU-Portugal_with_Madeira_circled.svg

, map_alt=Location of Madeira

, map_caption=Location of Madeira

, subdivision_type=Sovereign st ...

, the estate owners were again left with an inadequate supply of labor.

Portuguese Guyanese

A Portuguese Guyanese is a Guyanese whose ancestors came from Portugal or a Portuguese who has Guyanese citizenship.

Demographics

People of Portuguese descent were mainly introduced to Guyana as indentured laborers to make up for the exodus of ...

had not taken to plantation work and soon moved into other parts of the economy, especially retail business, where they became competitors with the new Afro-Guyanese middle class. Some 14,000 Chinese came to the colony between 1853 and 1912. Like their Portuguese predecessors, the

Chinese Guyanese

The first numbers of Chinese arrived in British Guiana in 1853, forming an important minority of the indentured workforce. After their indenture, many who stayed on in Guyana came to be known as successful retailers, with considerable integration w ...

forsook the plantations for the retail trades and soon became assimilated into Guianese society.

Concerned about the plantations' shrinking labor pool and the potential decline of the

sugar

Sugar is the generic name for sweet-tasting, soluble carbohydrates, many of which are used in food. Simple sugars, also called monosaccharides, include glucose, fructose, and galactose. Compound sugars, also called disaccharides or do ...

sector, British authorities, like their counterparts in Dutch Guiana, began to contract for the services of poorly paid

indentured workers from India. The East Indians, as this group was known locally, signed on for a certain number of years, after which, in theory, they would return to India with their savings from working in the sugar fields. The introduction of indentured East Indian workers alleviated the labor shortage and added another group to Guyana's ethnic mix. A majority of the

Indo-Guyanese

Indo-Guyanese or Indian-Guyanese, are people of Indian origin who are Guyanese nationals tracing their ancestry to India and the wider subcontinent. They are the descendants of indentured servants and settlers who migrated from India beginnin ...

workers had their origins in eastern Uttar Pradesh, with a smaller amount coming from Tamil and Telugu speaking areas in southern India. A small minority of these workers came from other areas such as Bengal, Punjab, and Gujarat.

Political and social awakenings

Nineteenth-century British Guiana

The constitution of the British colony favored the white and South Asian planters. Planter political power was based in the Court of Policy and the two courts of justice, established in the late 18th century under Dutch rule. The Court of Policy had both legislative and administrative functions and was composed of the governor, three colonial officials, and four colonists, with the governor presiding. The courts of justice resolved judicial matters, such as licensing and civil service appointments, which were brought before them by petition.

The Court of Policy and the courts of justice, controlled by the plantation owners, constituted the center of power in British Guiana. The colonists who sat on the Court of Policy and the courts of justice were appointed by the governor from a list of nominees submitted by two electoral colleges. In turn, the seven members of each

College of Electors were elected for life by those planters possessing twenty-five or more slaves. Though their power was restricted to nominating colonists to fill vacancies on the three major governmental councils, these electoral colleges provided a setting for political agitation by the planters.

Raising and disbursing revenue was the responsibility of the

Combined Court, which included members of the Court of Policy and six additional financial representatives appointed by the College of Electors. In 1855 the Combined Court also assumed responsibility for setting the salaries of all government officials. This duty made the Combined Court a center of intrigues resulting in periodic clashes between the governor and the planters.

Other Guyanese began to demand a more representative political system in the 19th century. By the late 1880s, pressure from the new Afro-Guyanese middle class was building for constitutional reform. In particular, there were calls to convert the Court of Policy into an assembly with ten elected members, to ease voter qualifications, and to abolish the College of Electors. Reforms were resisted by the planters, led by

Henry K. Davson, owner of a large plantation. In London the planters had allies in the

West India Committee

The West India Committee is a British-based organisation promoting ties and trade with the British Caribbean. It operates as a charity and NGO (non-governmental organisation). It evolved out of a lobbying group formed in 1780 to represent the inter ...

and also in the

West India Association of Glasgow, both presided over by proprietors with major interests in British Guiana.

Constitutional revisions in 1891 incorporated some of the changes demanded by the reformers. The planters lost political influence with the abolition of the College of Electors and the relaxation of voter qualification. At the same time, the Court of Policy was enlarged to sixteen members; eight of these were to be elected members whose power would be balanced by that of eight appointed members. The Combined Court also continued, consisting, as previously, of the Court of Policy and six financial representatives who were now elected. To ensure that there would be no shift of power to elected officials, the governor remained the head of the Court of Policy; the executive duties of the Court of Policy were transferred to a new

Executive Council, which the governor and planters dominated. The 1891 revisions were a great disappointment to the colony's reformers. As a result of the

1892 elections, the membership of the new Combined Court was almost identical to that of the previous one.

The next three decades saw additional, although minor, political changes. In 1897 the

secret ballot

The secret ballot, also known as the Australian ballot, is a voting method in which a voter's identity in an election or a referendum is anonymous. This forestalls attempts to influence the voter by intimidation, blackmailing, and potential vo ...

was introduced. A reform in 1909 expanded the limited British Guiana electorate, and for the first time, Afro-Guyanese constituted a majority of the eligible voters.

Political changes were accompanied by social change and jockeying by various ethnic groups for increased power. The British and Dutch planters refused to accept the Portuguese as equals and sought to maintain their status as aliens with no rights in the colony, especially voting rights. The political tensions led the Portuguese to establish the

Reform Association. After the

anti-Portuguese riots of 1898, the Portuguese recognized the need to work with other disenfranchised elements of Guyanese society, in particular the Afro-Guyanese. By around the start of the 20th century, organizations including the Reform Association and the

Reform Club

The Reform Club is a private members' club on the south side of Pall Mall in central London, England. As with all of London's original gentlemen's clubs, it comprised an all-male membership for decades, but it was one of the first all-male cl ...

began to demand greater participation in the colony's affairs. These organizations were largely the instruments of a small but articulate emerging middle class. Although the new middle class sympathized with the working class, the middle-class political groups were hardly representative of a national political or social movement. Indeed, working-class grievances were usually expressed in the form of riots.

Political and social changes in the early twentieth century

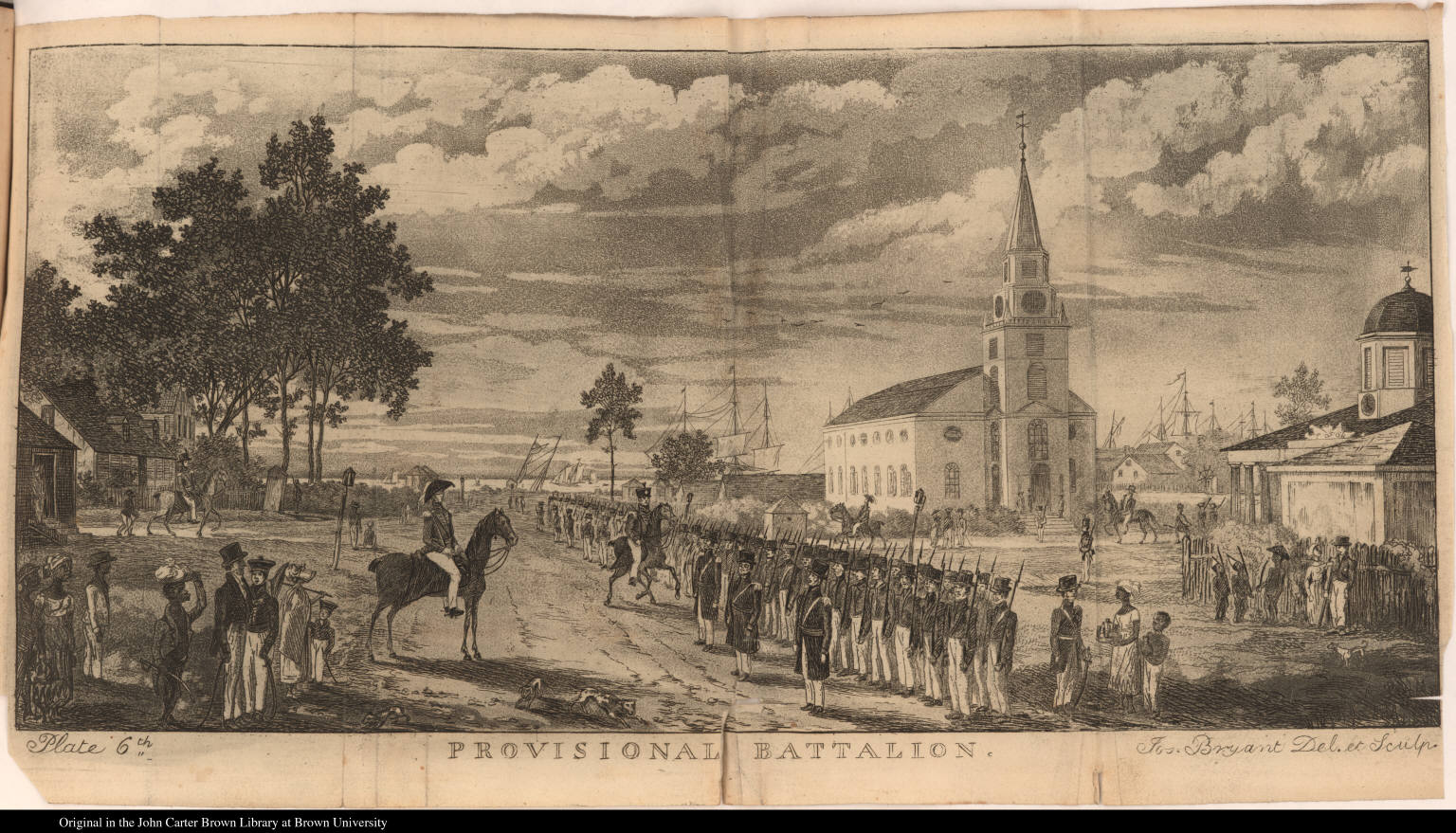

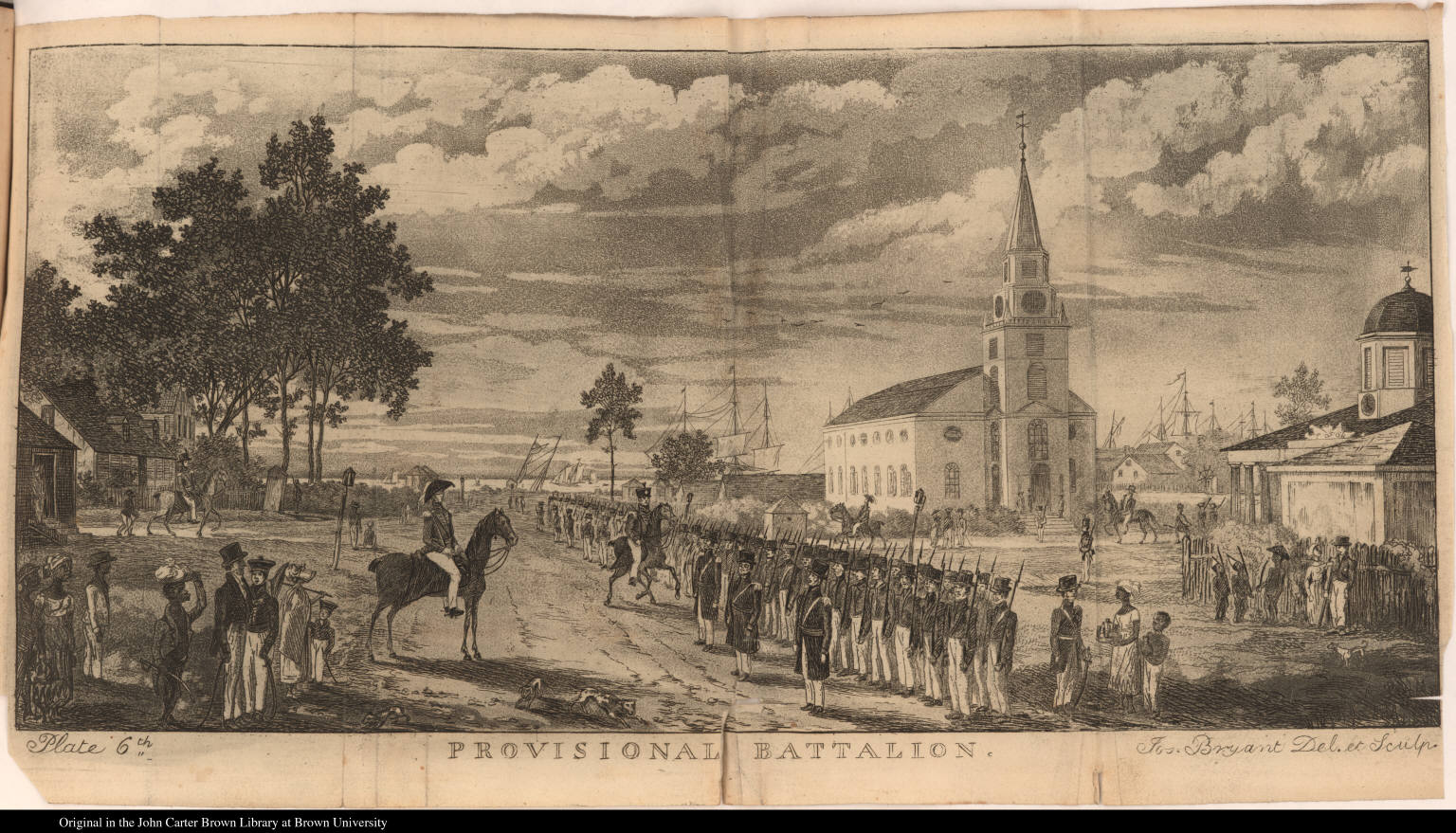

1905

Ruimveldt Riots rocked British Guiana. The severity of these outbursts reflected the workers' widespread dissatisfaction with their standard of living. The uprising began in late November 1905 when the Georgetown

stevedores

A stevedore (), also called a longshoreman, a docker or a dockworker, is a waterfront manual laborer who is involved in loading and unloading ships, trucks, trains or airplanes.

After the shipping container revolution of the 1960s, the number ...

went on strike, demanding higher wages. The strike grew confrontational, and other workers struck in sympathy, creating the country's first urban-rural worker alliance. On November 30, crowds of people took to the streets of Georgetown, and by December 1, 1905, now referred to as Black Friday, the situation had spun out of control. At the

Plantation Ruimveldt, close to Georgetown, a large crowd of porters refused to disperse when ordered to do so by a police patrol and a detachment of artillery. The colonial authorities opened fire, and four workers were seriously injured.

Word of the shootings spread rapidly throughout Georgetown and hostile crowds began roaming the city, taking over a number of buildings. By the end of the day, seven people were dead and seventeen badly injured. In a panic, the British administration called for help. Britain sent troops, who finally quelled the uprising. Although the stevedores' strike failed, the riots had planted the seeds of what would become an organized trade union movement.

Even though

World War I

World War I (28 July 1914 11 November 1918), often abbreviated as WWI, was List of wars and anthropogenic disasters by death toll, one of the deadliest global conflicts in history. Belligerents included much of Europe, the Russian Empire, ...

was fought far beyond the borders of British Guiana, the war altered Guyanese society. The Afro-Guyanese who joined the British military became the nucleus of an elite Afro-Guyanese community upon their return. World War I also led to the end of East Indian indentured service. British concerns over political stability in India and criticism by Indian nationalists that the program was a form of human bondage caused the British government to outlaw indentured labor in 1917.

In the closing years of World War I, the colony's first trade union was formed. The

British Guiana Labour Union The Guyana Labour Union is a trade union centre in Guyana, previously known as the British Guiana Labour Union.

History

The BGLU was founded in 1919, emerging as a labour union amongst black dockworkers. Led by Hubert Critchlow. It soon expanded i ...

(BGLU) was established in 1917 under the leadership of

H.N. Critchlow and led by

Alfred A. Thorne. Formed in the face of widespread business opposition, the BGLU at first mostly represented Afro-Guyanese

dockworkers

A stevedore (), also called a longshoreman, a docker or a dockworker, is a waterfront manual laborer who is involved in loading and unloading ships, trucks, trains or airplanes.

After the shipping container revolution of the 1960s, the number ...

. Its membership stood around 13,000 by 1920, and it was granted legal status in 1921 under the

Trades Union Ordinance. Although recognition of other unions would not come until 1939, the BGLU was an indication that the working class was becoming politically aware and more concerned with its rights.

The second trade union, the British Guiana Workers' League, was established in 1931 by

Alfred A. Thorne, who served as the League's leader for 22 years. The League sought to improve the working conditions for people of all ethnic backgrounds in the colony. Most workers were of West African, East Indian, Chinese and Portuguese descent, and had been brought to the country under a system of forced or indentured labor.

After World War I, new economic interest groups began to clash with the Combined Court. The country's economy had come to depend less on sugar and more on rice and

bauxite

Bauxite is a sedimentary rock with a relatively high aluminium content. It is the world's main source of aluminium and gallium. Bauxite consists mostly of the aluminium minerals gibbsite (Al(OH)3), boehmite (γ-AlO(OH)) and diaspore (α-AlO ...

, and producers of these new commodities resented the sugar planters' continued domination of the Combined Court. Meanwhile, the planters were feeling the effects of lower sugar prices and wanted the Combined Court to provide the necessary funds for new drainage and irrigation programs.

To stop the bickering and resultant legislative paralysis, in 1928 the

Colonial Office

The Colonial Office was a government department of the Kingdom of Great Britain and later of the United Kingdom, first created to deal with the colonial affairs of British North America but required also to oversee the increasing number of c ...

announced a new constitution that would make British Guiana a

crown colony

A Crown colony or royal colony was a colony administered by The Crown within the British Empire. There was usually a Governor, appointed by the British monarch on the advice of the UK Government, with or without the assistance of a local Council ...

under the tight control of a governor appointed by the Colonial Office. The Combined Court and the Court of Policy were replaced by a

Legislative Council with a majority of appointed members. To middle-class and working-class political activists, this new constitution represented a step backward and a victory for the planters. Influence over the governor, rather than the promotion of a particular public policy, became the most important issue in any political campaign.

The

Great Depression

The Great Depression (19291939) was an economic shock that impacted most countries across the world. It was a period of economic depression that became evident after a major fall in stock prices in the United States. The economic contagio ...

of the 1930s brought economic hardship to all segments of Guyanese society. All of the colony's major exports—sugar, rice and bauxite—were affected by low prices, and unemployment soared. As in the past, the working class found itself lacking a political voice during a time of worsening economic conditions. By the mid-1930s, British Guiana and the whole British Caribbean were marked by labor unrest and violent demonstrations. In the aftermath of riots throughout the

British West Indies

The British West Indies (BWI) were colonized British territories in the West Indies: Anguilla, the Cayman Islands, Turks and Caicos Islands, Montserrat, the British Virgin Islands, Antigua and Barbuda, The Bahamas, Barbados, Dominica, Grena ...

, a royal commission under

Lord Moyne

Walter Edward Guinness, 1st Baron Moyne, DSO & Bar, PC (29 March 1880 – 6 November 1944), was an Anglo-Irish politician and businessman. He served as the British minister of state in the Middle East until November 1944, when he was assass ...

was established to determine the reasons for the riots and to make recommendations.

In British Guiana, the

Moyne Commission The Report of West India Royal Commission, also known as The Moyne Report, was published fully in 1945 and exposed the poor living conditions in Britain's Caribbean colonies. Following the British West Indian labour unrest of 1934–1939, the Imperi ...

questioned a wide range of people, including trade unionists, Afro-Guyanese professionals, and representatives of the Indo-Guyanese community. The commission pointed out the deep division between the country's two largest ethnic groups, the Afro-Guyanese and the Indo-Guyanese. The largest group, the Indo-Guyanese, consisted primarily of rural rice producers or merchants; they had retained the country's traditional culture and did not participate in national politics. The Afro-Guyanese were largely urban workers or bauxite miners; they had adopted European culture and dominated national politics. To increase the representation of the majority of the population in British Guiana, the Moyne Commission called for increased democratization of government as well as economic and social reforms.

The Moyne Commission report in 1939 was a turning point for British Guiana. It urged extending the franchise to women and persons not owning land and encouraged the emerging trade union movement. However, none of the Moyne Commission's recommendations were immediately implemented because of the outbreak of

World War II

World War II or the Second World War, often abbreviated as WWII or WW2, was a world war that lasted from 1939 to 1945. It involved the World War II by country, vast majority of the world's countries—including all of the great power ...

.

With the fighting far away, the period of World War II in British Guiana was marked by continuing political reform and improvements to the national infrastructure. The governor, Sir

Gordon Lethem, created the country's first Ten-Year Development Plan (led by Sir Oscar Spencer, the Economic Adviser to the Governor and

Alfred P. Thorne, Assistant to the Economic Adviser), reduced property qualifications for office holding and voting, and made elective members a majority on the Legislative Council in 1943. Under the aegis of the

Lend-Lease Act of 1941, a modern air base (now

Timehri Airport) was constructed by United States troops. By the end of World War II, British Guiana's political system had been widened to encompass more elements of society and the economy's foundations had been strengthened by increased demand for bauxite.

Pre-independence government

Development of political parties

At the end of World War II, political awareness and demands for independence grew in all segments of society. The immediate postwar period witnessed the founding of Guyana's major political parties. The

People's Progressive Party (PPP) was founded on January 1, 1950. Internal conflicts developed in the PPP, and in 1957 the

People's National Congress (PNC) was created as a split-off. These years also saw the beginning of a long and acrimonious struggle between the country's two dominant political personalities—

Cheddi Jagan

Cheddi Berret Jagan (22 March 1918 – 6 March 1997) was a Guyanese politician and dentist who was first elected Chief Minister in 1953 and later Premier of British Guiana from 1961 to 1964. He later served as President of Guyana from 199 ...

and

Linden Forbes Burnham

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham (20 February 1923 – 6 August 1985) was a Guyanese politician and the leader of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana from 1964 until his death in 1985. He served as Prime Minister from 1964 to 1980 and then as its ...

.

Cheddi Jagan

Cheddi Jagan

Cheddi Berret Jagan (22 March 1918 – 6 March 1997) was a Guyanese politician and dentist who was first elected Chief Minister in 1953 and later Premier of British Guiana from 1961 to 1964. He later served as President of Guyana from 199 ...

had been born in Guyana in 1918. His parents were immigrants from India. His father was a driver, a position considered to be on the lowest rung of the middle stratum of Guyanese society. Jagan's childhood gave him a lasting insight into rural poverty. Despite their poor background, the senior Jagan sent his son to

Queen's College in Georgetown. After his education there, Jagan went to the United States to study dentistry, graduating from

Northwestern University

Northwestern University is a private research university in Evanston, Illinois. Founded in 1851, Northwestern is the oldest chartered university in Illinois and is ranked among the most prestigious academic institutions in the world.

Charte ...

in

Evanston, Illinois

Evanston ( ) is a city, suburb of Chicago. Located in Cook County, Illinois, United States, it is situated on the North Shore along Lake Michigan. Evanston is north of Downtown Chicago, bordered by Chicago to the south, Skokie to the west, ...

in 1942.

Jagan returned to British Guiana in October 1943 and was soon joined by his American wife, the former

Janet Rosenberg, who was to play a significant role in her new country's political development. Although Jagan established his own dentistry clinic, he was soon enmeshed in politics. After a number of unsuccessful forays into Guyana's political life, Jagan became treasurer of the

Manpower Citizens' Association (MPCA) in 1945. The MPCA represented the colony's sugar workers, many of whom were Indo-Guyanese. Jagan's tenure was brief, as he clashed repeatedly with the more moderate union leadership over policy issues. Despite his departure from the MPCA a year after joining, the position allowed Jagan to meet other union leaders in British Guiana and throughout the

English-speaking Caribbean.

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham

Born in 1923,

Forbes Burnham

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham (20 February 1923 – 6 August 1985) was a Guyanese politician and the leader of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana from 1964 until his death in 1985. He served as Prime Minister of Guyana, Prime Minister from 1964 ...

was the sole son in a family that had three children. His father was headmaster of

Kitty Methodist Primary School, which was located just outside Georgetown. As part of the colony's educated class, young Burnham was exposed to political viewpoints at an early age. He did exceedingly well in school and went to London to obtain a law degree. Although not exposed to childhood poverty as was Jagan, Burnham was acutely aware of racial discrimination.

The social strata of the urban Afro-Guyanese community of the 1930s and 1940s included a mulatto or "coloured" elite, a black professional middle class, and, at the bottom, the black working class. Unemployment in the 1930s was high. When war broke out in 1939, many Afro-Guyanese joined the military, hoping to gain new job skills and escape poverty. When they returned home from the war, however, jobs were still scarce and discrimination was still a part of life.

Founding of the PAC and PPP

The springboard for Jagan's political career was the Political Affairs Committee (PAC), formed in 1946 as a discussion group. The new organization published the ''

PAC Bulletin'' to promote its

Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

ideology and ideas of liberation and decolonization. The PAC's outspoken criticism of the colony's poor living standards attracted followers as well as detractors.

In the November 1947 general elections, the PAC put forward several members as independent candidates. The PAC's major competitor was the newly formed

British Guiana Labour Party

The British Guiana Labour Party (BGCP) was a political party in British Guiana.

History

The BGCP was formed in June 1946, with its leadership included Jung Bahadur Singh, J.A. Nicholson, Hubert Nathaniel Critchlow and Ashton Chase

Ashton may ...

, which, under

J.B. Singh, won six of fourteen seats contested. Jagan won a seat and briefly joined the Labour Party. But he had difficulties with his new party's center-right ideology and soon left its ranks. The Labour Party's support of the policies of the British governor and its inability to create a grass-roots base gradually stripped it of liberal supporters throughout the country. The Labour Party's lack of a clear-cut reform agenda left a vacuum, which Jagan rapidly moved to fill. Turmoil on the colony's sugar plantations gave him an opportunity to achieve national standing. After the June 16, 1948 police shootings of five Indo-Guyanese workers at

Enmore, close to Georgetown, the PAC and the

Guiana Industrial Workers' Union (GIWU) organized a large and peaceful demonstration, which clearly enhanced Jagan's standing with the Indo-Guyanese population.

After the PAC, Jagan's next major step was the founding of the

People's Progressive Party (PPP) in January 1950. Using the PAC as a foundation, Jagan created from it a new party that drew support from both the Afro-Guyanese and Indo-Guyanese communities. To increase support among the Afro-Guyanese, Forbes Burnham was brought into the party.

The PPP's initial leadership was multi-ethnic and left of center, but hardly revolutionary. Jagan became the leader of the PPP's parliamentary group, and Burnham assumed the responsibilities of party chairman. Other key party members included Janet Jagan,

Brindley Benn

Brindley Horatio Benn, CCH (24 January 1923 – 11 December 2009) was a teacher, choirmaster, politician, and one of the key leaders of the Guyanese independence movement. He was put under restriction when the constitution was suspended in 1953. ...

and

Ashton Chase

Ashton may refer to:

Names

*Ashton (given name)

*Ashton (surname)

Places Australia

* Ashton, Elizabeth Bay, a heritage-listed house in Sydney, New South Wales

*Ashton, South Australia

Canada

*Ashton, Ontario

New Zealand

*Ashton, New Zealand

S ...

, both PAC veterans. The new party's first victory came in the 1950 municipal elections, in which Janet Jagan won a seat. Cheddi Jagan and Burnham failed to win seats, but Burnham's campaign made a favorable impression on many Afro-Guyanese citizens.

From its first victory in the 1950 municipal election, the PPP gathered momentum. However, the party's often strident

anticapitalist and

socialist

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes the ...

message made the British government uneasy. Colonial officials showed their displeasure with the PPP in 1952 when, on a regional tour, the Jagans were designated prohibited immigrants in

Trinidad

Trinidad is the larger and more populous of the two major islands of Trinidad and Tobago. The island lies off the northeastern coast of Venezuela and sits on the continental shelf of South America. It is often referred to as the southernmos ...

and

Grenada

Grenada ( ; Grenadian Creole French: ) is an island country in the West Indies in the Caribbean Sea at the southern end of the Grenadines island chain. Grenada consists of the island of Grenada itself, two smaller islands, Carriacou and Pet ...

.

A British commission in 1950 recommended universal adult suffrage and the adoption of a

ministerial system for British Guiana. The commission also recommended that power be concentrated in the

executive branch

The Executive, also referred as the Executive branch or Executive power, is the term commonly used to describe that part of government which enforces the law, and has overall responsibility for the governance of a state.

In political systems ...

, that is, the office of the governor. These reforms presented British Guiana's parties with an opportunity to participate in national elections and form a government, but maintained power in the hands of the British-appointed chief executive. This arrangement rankled the PPP, which saw it as an attempt to curtail the party's political power.

The first PPP government

Once the new constitution was adopted, elections were set for

1953

Events

January

* January 6 – The Asian Socialist Conference opens in Rangoon, Burma.

* January 12 – Estonian émigrés found a government-in-exile in Oslo.

* January 14

** Marshal Josip Broz Tito is chosen President of Yugosl ...

. The PPP's coalition of lower-class Afro-Guyanese and rural Indo-Guyanese workers, together with elements of both ethnic groups' middle sectors, made for a formidable constituency. Conservatives branded the PPP as

communist

Communism (from Latin la, communis, lit=common, universal, label=none) is a far-left sociopolitical, philosophical, and economic ideology and current within the socialist movement whose goal is the establishment of a communist society, ...

, but the party campaigned on a center-left platform and appealed to a growing nationalism. The other major party participating in the election, the

National Democratic Party (NDP), was a spin-off of the

League of Coloured Peoples

The League of Coloured Peoples (LCP) was a British civil-rights organization that was founded in 1931 in London by Jamaican-born physician and campaigner Harold Moody with the goal of racial equality around the world, a primary focus being on bl ...

and was largely an Afro-Guyanese middle-class organization, sprinkled with middle-class Portuguese and Indo-Guyanese. The NDP, together with the poorly organized

United Farmers and Workers Party and the

United National Party

The United National Party, often abbreviated as UNP ( si, එක්සත් ජාතික පක්ෂය, translit=Eksath Jāthika Pakshaya, ta, ஐக்கிய தேசியக் கட்சி, translit=Aikkiya Tēciyak Kaṭci), ...

, was soundly defeated by the PPP. Final results gave the PPP eighteen of twenty-four seats compared with the NDP's two seats and four seats for independents.

The PPP's first administration was brief. The legislature opened on May 30, 1953. Already suspicious of Jagan and the PPP's radicalism, conservative forces in the business community were further distressed by the new administration's program of expanding the role of the state in the economy and society. The PPP also sought to implement its reform program at a rapid pace, which brought the party into confrontation with the governor and with high-ranking civil servants who preferred more gradual change. The issue of civil service appointments also threatened the PPP, in this case from within. Following the 1953 victory, these appointments became an issue between the predominantly Indo-Guyanese supporters of Jagan and the largely Afro-Guyanese backers of Burnham. Burnham threatened to split the party if he were not made sole leader of the PPP. A compromise was reached by which members of what had become Burnham's faction received ministerial appointments.

The PPP's introduction of the

Labour Relations Act

Labour or labor may refer to:

* Childbirth, the delivery of a baby

* Labour (human activity), or work

** Manual labour, physical work

** Wage labour, a socioeconomic relationship between a worker and an employer

** Organized labour and the labour ...

provoked a confrontation with the British. This law ostensibly was aimed at reducing intraunion rivalries, but would have favored the GIWU, which was closely aligned with the ruling party. The opposition charged that the PPP was seeking to gain control over the colony's economic and social life and was moving to stifle the opposition. The day the act was introduced to the legislature, the GIWU went on strike in support of the proposed law. The British government interpreted this intermingling of party politics and labor unionism as a direct challenge to the constitution and the authority of the governor. The day after the act was passed, on October 9, 1953, London suspended the colony's constitution and, under pretext of quelling disturbances, sent in troops.

The interim government

Following the suspension of the constitution, British Guiana was governed by an interim administration consisting of a small group of conservative politicians, businessmen, and civil servants that lasted until 1957. Order in the colonial government masked a growing rift in the country's main political party as the personal conflict between the PPP's Jagan and Burnham widened into a bitter dispute. In 1955 Jagan and Burnham formed rival wings of the PPP. Support for each leader was largely, but not totally, along ethnic lines.

J. P. Lachmansingh, a leading Indo-Guyanese and head of the GIWU, supported Burnham, whereas Jagan retained the loyalty of a number of leading Afro-Guyanese radicals, such as

Sydney King. Burnham's wing of the PPP moved to the right, leaving Jagan's wing on the left, where he was regarded with considerable apprehension by Western governments and the colony's conservative business groups.

The second PPP government

The

1957 elections held under a

new constitution demonstrated the extent of the growing ethnic division within the Guyanese electorate. The revised constitution provided limited

self-government

__NOTOC__

Self-governance, self-government, or self-rule is the ability of a person or group to exercise all necessary functions of regulation without intervention from an external authority. It may refer to personal conduct or to any form of ...

, primarily through the Legislative Council. Of the council's twenty-four delegates, fifteen were elected, six were nominated, and the remaining three were to be

ex officio

An ''ex officio'' member is a member of a body (notably a board, committee, council) who is part of it by virtue of holding another office. The term '' ex officio'' is Latin, meaning literally 'from the office', and the sense intended is 'by right ...

members from the interim administration. The two wings of the PPP launched vigorous campaigns, each attempting to prove that it was the legitimate heir to the original party. Despite denials of such motivation, both factions made a strong appeal to their respective ethnic constituencies.

The 1957 elections were convincingly won by

Jagan's

PPP faction. Although his group had a secure parliamentary majority, its support was drawn more and more from the

Indo-Guyanese

Indo-Guyanese or Indian-Guyanese, are people of Indian origin who are Guyanese nationals tracing their ancestry to India and the wider subcontinent. They are the descendants of indentured servants and settlers who migrated from India beginnin ...

community. The faction's main planks were increasingly identified as Indo-Guyanese: more rice land, improved union representation in the sugar industry, and improved business opportunities and more government posts for Indo-Guyanese.

Jagan's veto of

British Guiana

British Guiana was a British colony, part of the mainland British West Indies, which resides on the northern coast of South America. Since 1966 it has been known as the independent nation of Guyana.

The first European to encounter Guiana was ...

's participation in the

West Indies Federation

The West Indies Federation, also known as the West Indies, the Federation of the West Indies or the West Indian Federation, was a short-lived political union that existed from 3 January 1958 to 31 May 1962. Various islands in the Caribbean that ...

resulted in the complete loss of

Afro-Guyanese support. In the late 1950s, the British Caribbean colonies had been actively negotiating establishment of a West Indies Federation. The PPP had pledged to work for the eventual political union of British Guiana with the Caribbean territories. The Indo-Guyanese, who constituted a majority in Guyana, were apprehensive of becoming part of a federation in which they would be outnumbered by people of African descent. Jagan's veto of the federation caused his party to lose all significant Afro-Guyanese support.

Burnham learned an important lesson from the 1957 elections. He could not win if supported only by the lower-class, urban Afro-Guyanese. He needed

middle-class

The middle class refers to a class of people in the middle of a social hierarchy, often defined by occupation, income, education, or social status. The term has historically been associated with modernity, capitalism and political debate. Com ...

allies, especially those Afro-Guyanese who backed the moderate

United Democratic Party. From 1957 onward, Burnham worked to create a balance between maintaining the backing of the more radical Afro-Guyanese lower classes and gaining the support of the more capitalist middle class. Clearly, Burnham's stated preference for

socialism

Socialism is a left-wing economic philosophy and movement encompassing a range of economic systems characterized by the dominance of social ownership of the means of production as opposed to private ownership. As a term, it describes th ...

would not bind those two groups together against Jagan, an avowed

Marxist

Marxism is a left-wing to far-left method of socioeconomic analysis that uses a materialist interpretation of historical development, better known as historical materialism, to understand class relations and social conflict and a dialecti ...

. The answer was something more basic:

race. Burnham's appeals to race proved highly successful in bridging the schism that divided the Afro-Guyanese along class lines. This strategy convinced the powerful Afro-Guyanese middle class to accept a leader who was more of a radical than they would have preferred to support. At the same time, it neutralized the objections of the black working class to entering an alliance with those representing the more moderate interests of the middle classes. Burnham's move toward the right was accomplished with the merger of his PPP faction and the United Democratic Party into a new organization, the

People's National Congress (PNC).

Following the 1957 elections, Jagan rapidly consolidated his hold on the Indo-Guyanese community. Though candid in expressing his admiration for

Joseph Stalin

Joseph Vissarionovich Stalin (born Ioseb Besarionis dze Jughashvili; – 5 March 1953) was a Georgian revolutionary and Soviet Union, Soviet political leader who led the Soviet Union from 1924 until his death in 1953. He held power as Ge ...

,

Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong pronounced ; also Romanization of Chinese, romanised traditionally as Mao Tse-tung. (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese communist revolutionary who was the List of national founde ...

, and, later,

Fidel Castro Ruz, Jagan in power asserted that the PPP's Marxist-

Leninist

Leninism is a political ideology developed by Russian Marxist revolutionary Vladimir Lenin that proposes the establishment of the dictatorship of the proletariat led by a revolutionary vanguard party as the political prelude to the establishm ...

principles must be adapted to Guyana's own particular circumstances. Jagan advocated

nationalization

Nationalization (nationalisation in British English) is the process of transforming privately-owned assets into public assets by bringing them under the public ownership of a national government or state. Nationalization usually refers to p ...

of foreign holdings, especially in the sugar industry. British fears of a communist takeover, however, caused the British governor to hold Jagan's more radical policy initiatives in check.

PPP re-election and debacle

The 1961 elections were a bitter contest between the PPP, the PNC, and the United Force (UF), a conservative party representing big business, the

Roman Catholic Church

The Catholic Church, also known as the Roman Catholic Church, is the largest Christian church, with 1.3 billion baptized Catholics worldwide . It is among the world's oldest and largest international institutions, and has played a ...

, and Amerindian, Chinese, and Portuguese voters. These elections were held under yet another new constitution that marked a return to the degree of self-government that existed briefly in 1953. It introduced a

bicameral

Bicameralism is a type of legislature, one divided into two separate assemblies, chambers, or houses, known as a bicameral legislature. Bicameralism is distinguished from unicameralism, in which all members deliberate and vote as a single gr ...

system boasting a wholly elected thirty-five-member Legislative Assembly and a thirteen-member Senate to be appointed by the governor. The post of prime minister was created and was to be filled by the majority party in the Legislative Assembly. With the strong support of the Indo-Guyanese population, the PPP again won by a substantial margin, gaining twenty seats in the Legislative Assembly, compared to eleven seats for the PNC and four for the UF. Jagan was named prime minister.

Jagan's administration became increasingly friendly with communist and leftist regimes; for instance, Jagan refused to observe the United States embargo on communist

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

. After discussions between Jagan and Cuban revolutionary

Ernesto "Che" Guevara

Ernesto Che Guevara (; 14 June 1928The date of birth recorded on /upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/7/78/Ernesto_Guevara_Acta_de_Nacimiento.jpg his birth certificatewas 14 June 1928, although one tertiary source, (Julia Constenla, quoted ...

in 1960 and 1961, Cuba offered British Guiana loans and equipment. In addition, the Jagan administration signed trade agreements with

Hungary

Hungary ( hu, Magyarország ) is a landlocked country in Central Europe. Spanning of the Carpathian Basin, it is bordered by Slovakia to the north, Ukraine to the northeast, Romania to the east and southeast, Serbia to the south, Cr ...

and the

German Democratic Republic

German(s) may refer to:

* Germany (of or related to)

** Germania (historical use)

* Germans, citizens of Germany, people of German ancestry, or native speakers of the German language

** For citizens of Germany, see also German nationality law

**G ...

(East Germany).

From 1961 to 1964, Jagan was confronted with a destabilization campaign conducted by the PNC and UF. In addition to domestic opponents of Jagan, an important role was played by the

American Institute for Free Labor Development

The American Institute for Free Labor Development (AIFLD) was established in late 1961 by the AFL–CIO in the western hemisphere. It received funding from the US government, mostly through USAID (United States Agency for International Development) ...

(AIFLD), which was alleged to be a front for the

CIA

The Central Intelligence Agency (CIA ), known informally as the Agency and historically as the Company, is a civilian foreign intelligence service of the federal government of the United States, officially tasked with gathering, processing, ...

. Various reports say that AIFLD, with a budget of US$800,000, maintained anti-Jagan labor leaders on its payroll, as well as an AIFLD-trained staff of 11 activists who were assigned to organize riots and destabilize the Jagan government. Riots and demonstrations against the PPP administration were frequent, and during disturbances in 1962 and 1963 mobs destroyed part of Georgetown,

doing $40 million in damage.

To counter the MPCA with its link to Burnham, the PPP formed the

Guiana Agricultural Workers Union

The Guyana Agricultural and General Workers' Union (GAWU) is the largest trade union in Guyana. It was founded in 1946 as the Guiana Industrial Workers' Union. After failing in the 1950s it was reformed as the Guyana Sugar Workers' Union in 1961 b ...

. This new union's political mandate was to organize the Indo-Guyanese sugarcane field-workers. The MPCA immediately responded with a one-day strike to emphasize its continued control over the sugar workers.

The PPP government responded to the strike in March 1964 by publishing a new

Labour Relations Bill almost identical to the 1953 legislation that had resulted in British intervention. Regarded as a power play for control over a key labor sector, introduction of the proposed law prompted protests and rallies throughout the capital. Riots broke out on April 5; they were followed on April 18 by a general strike. By May 9, the governor was compelled to declare a state of emergency. Nevertheless, the strike and violence continued until July 7, when the Labour Relations Bill was allowed to lapse without being enacted. To bring an end to the disorder, the government agreed to consult with union representatives before introducing similar bills. These disturbances exacerbated tension and animosity between the two major ethnic communities and made a reconciliation between Jagan and Burnham an impossibility.

Jagan's term had not yet ended when another round of labor unrest rocked the colony. The pro-PPP GIWU, which had become an umbrella group of all labor organizations, called on sugar workers to strike in January 1964. To dramatize their case, Jagan led a march by sugar workers from the interior to Georgetown. This demonstration ignited outbursts of violence that soon escalated beyond the control of the authorities. On May 22, the governor finally declared another state of emergency. The situation continued to worsen, and in June the governor assumed full powers, rushed in British troops to restore order, and proclaimed a moratorium on all political activity. By the end of the turmoil, 160 people were dead and more than 1,000 homes had been destroyed.

In an effort to quell the turmoil, the country's political parties asked the British government to modify the constitution to provide for more proportional representation. The colonial secretary proposed a fifty-three member unicameral legislature. Despite opposition from the ruling PPP, all reforms were implemented and new elections set for October 1964.

As Jagan feared, the PPP lost the general elections of 1964. The politics of ''

apan jhaat'',

Hindi

Hindi (Devanāgarī: or , ), or more precisely Modern Standard Hindi (Devanagari: ), is an Indo-Aryan language spoken chiefly in the Hindi Belt region encompassing parts of northern, central, eastern, and western India. Hindi has been ...

for "vote for your own kind", were becoming entrenched in Guyana. The PPP won 46 percent of the vote and twenty-four seats, which made it the largest single party but short of an overall majority. However, the PNC, which won 40 percent of the vote and twenty-two seats, and the UF, which won 11 percent of the vote and seven seats, formed a coalition. The socialist PNC and unabashedly capitalist UF had joined forces to keep the PPP out of office for another term. Jagan called the election fraudulent and refused to resign as prime minister. The constitution was amended to allow the governor to remove Jagan from office. Burnham became prime minister on December 14, 1964.

Independence and the Burnham era

Burnham in power

In the first year under

Forbes Burnham

Linden Forbes Sampson Burnham (20 February 1923 – 6 August 1985) was a Guyanese politician and the leader of the Co-operative Republic of Guyana from 1964 until his death in 1985. He served as Prime Minister of Guyana, Prime Minister from 1964 ...

, conditions in the colony began to stabilize. The new coalition administration broke diplomatic ties with

Cuba

Cuba ( , ), officially the Republic of Cuba ( es, República de Cuba, links=no ), is an island country comprising the island of Cuba, as well as Isla de la Juventud and several minor archipelagos. Cuba is located where the northern Caribb ...

and implemented policies that favored local investors and foreign industry. The colony applied the renewed flow of Western

aid to further development of its infrastructure. A constitutional conference was held in

London

London is the capital and List of urban areas in the United Kingdom, largest city of England and the United Kingdom, with a population of just under 9 million. It stands on the River Thames in south-east England at the head of a estuary dow ...

; the conference set May 26, 1966 as the date for the colony's independence. By the time independence was achieved, the country was enjoying economic growth and relative domestic peace.

The newly independent Guyana at first sought to improve relations with its neighbors. For instance, in December 1965 the country had become a charter member of the

Caribbean Free Trade Association (Carifta). Relations with

Venezuela

Venezuela (; ), officially the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela ( es, link=no, República Bolivariana de Venezuela), is a country on the northern coast of South America, consisting of a continental landmass and many islands and islets in th ...

were not so placid, however. In 1962 Venezuela had announced that it was rejecting the 1899 boundary and would renew its claim to all of Guyana west of the

Essequibo River

The Essequibo River ( Spanish: ''Río Esequibo'' originally called by Alonso de Ojeda ''Río Dulce'') is the largest river in Guyana, and the largest river between the Orinoco and Amazon. Rising in the Acarai Mountains near the Brazil–Guyana b ...

. In 1966, Venezuela seized the Guyanese half of

Ankoko Island, in the

Cuyuni River, and two years later claimed a strip of sea along Guyana's western coast.

Another challenge to the newly independent government came at the beginning of January 1969, with the

Rupununi Uprising